ABSTRACT

This article seeks to identify traces of language contact between speakers of Australian languages and speakers of Austronesian languages other than Macassans. I put forward evidence for lexical borrowing into northern Australian languages from Austronesian languages in South and East Sulawesi, Maluku and Timor-Rote, as well as from Austronesian languages of the Sama-Bajau and Oceanic subgroups. Although the evidence is fragmentary, the presence of these borrowings could be taken to indicate a more varied history of contact with Australia than the Macassan-dominated linguistic data suggest.

1. Introduction

Almost thirty years ago in this journal, Evans (Citation1992) meticulously laid out the extent of MacassanFootnote1 loans across Arnhem Land in northern Australia. At the same time, he drew attention to the existence of a large number of likely loanwords for which the source had not been identified. Evans (Citation1997, p. 260) followed up, writing “[c]learly we need to continue searching for possible donor languages for the many suspected loanwords into north Australian languages whose sources remain unidentified”. This article answers that call by offering speculations on possible directions for future research on pre-colonial contact between indigenous groups in northern Australia and speakers of Austronesian languages to the west and east of the Australian continent.

A growing body of archaeology indicates that there was contact between Indigenous Australians and peoples beyond predating the rise of the Macassan sea cucumber industry in the eighteenth century. This article represents an attempt to connect linguistic material from Austronesia with this archaeological evidence of earlier contact. I make connections between lexical items identified as likely borrowings in the Australianist literature and lexemes in Austronesian languages. In order to narrow down the search domains for this study, I limited myself to looking at lexical items in semantic domains identified to be the focus of Macassan borrowing in previous studies, particularly Evans (Citation1992) and Walker and Zorc (Citation1981). The items I discuss are known trade items (metal products, plants, sea resources) and terms used in sailing and fishing.

My perspective is that of a linguist working in eastern Indonesia, in particular in Timor and Aru. Many of the lexical connections I name are somewhat speculative, while others represent claims of greater solidity; all will require further research to identify their precise source languages. At least some of the contact events I posit may lie further back in time than the Macassan contact as part of the sea cucumber trade and/or may not have been as intense. This means that the evidence for the contact is limited and, therefore, open to dispute. Where possible, however, I present historical materials about trade and maritime practices to support the contact scenarios I posit.

This article is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the term ‘Macassan’ and the problems it presents. Section 3 suggests lexical connections between northern Australian and Austronesian languages. Section 4 concludes with a short discussion of the challenges confronting linguists wanting to reconstruct non-Macassan contact histories.

2. Unravelling the ‘Macassans’

The size and significance of the Macassan sea cucumber trade in northern Australia has been demonstrated by anthropologists, archaeologists and historians. A substantial amount of linguistic evidence has reinforced the picture of Macassan influence (Cense, Citation1952; Evans, Citation1992, Citation1997; Walker & Zorc, Citation1981; Zorc, Citation1986).

However, Macknight (Citation2018, p. 25) has recently lamented what he calls “the wild use of the unfortunate term ‘Macassan’” in the context of contact with Indigenous Australian groups. It is certainly true that most of the sea cucumber fishermen sailing to Australia’s North would have operated out of the port of Makasar. Numerous borrowings in Indigenous Australian languages originating in Makasarese provide ample testament to the presence of people belonging to the Makasarese ethnic group. Yet, the crew on Macassan ships were typically of diverse ethnicities and, accordingly, spoke several different languages.Footnote2 This is known, for example, from the eye-witness account of Earl:

… about the month of April, when the prahus congregate at Port Essington, the population of the settlement became of a very motley character, for then Australians of perhaps a dozen different tribes might be seen mixed up with natives of Celebes and Sumbawa, Badjus of the coast of Borneo, Timorians, and Javanese, with an occasional sprinkling of New Guinea negroes. (Earl, Citation1846, p. 240)

The Bugis, a people and language closely related to Makasarese and spoken just to its north, are often named and were very likely present amongst the Macassan crews. However, their language has left no as yet discernible mark in northern Australia. Evans (Citation1997, p. 237) writes that he finds no loanwords which are unambiguously Buginese; Makasarese forms in almost all cases provide better matches for the identified borrowings and in the remaining cases as good a fit as Buginese. In his fascinating work East Monsoon, Collins (Citation1936, p. 10) writes: “I had been in Makasar for just a week, and had spent much time talking to masters of ships in the prahu harbour. Nearly all were Bugis, and with few exceptions spoke Malay, the lingua franca of the islands”. The dominance of Malay thus provides an explanation as to why no Buginese influence, and very little from other Indonesian languages, is found in northern Australian languages despite their heavy engagement in Macassan enterprises.

Given the considerable and specifically Macassan influence in northern Australia, it is perhaps not surprising that the term ‘Macassan’ has become firmly entrenched in the scholarly literature of diverse disciplines. According to the latest information given in Macknight (Citation2008), the earliest excursions to northern Australia by Macassans may have occurred in the 1750s, but the sea cucumber industry only came into full swing in the 1780s. Increasingly, however, a longer chronology for contact is being proposed. Most notably, Clarke (Citation1994, p. 470) argues that on Groote Eylandt there is:

archaeological evidence in support of contact with Indonesian fishermen at an earlier date than that indicated by the documentary evidence analysed by Macknight (Citation1976). [She] would place this earlier contact to have occurred between 1000 and 900 years ago. This initial contact was not necessarily of the order of magnitude of the later sea cucumber industry, organised from the city of Makasar and may have been both sporadic and small scale.

The question, then, remains who were these earlier groups and what languages did they speak. As Evans (Citation1992) points out, it seems very unlikely that the Macassans were the first or only speakers of Austronesian languages to visit northern Australia. In order to assist in developing a more variegated picture of northern Australian contact than that of a Macassan-dominated sea cucumber industry found in the current literature, I offer some suggestions as to where linguists might reasonably look for signs of non-Macassan contact in what follows.

3. Contact beyond Macassans

Austronesian languages are spread widely across Island Southeast and Oceania. Their speakers occupy a wide array of ecological environments and have accordingly diverse subsistence patterns. While many Austronesian-speaking groups lack a sea-faring culture and are oriented towards the land, particularly in the interior of the larger islands, others have long traditions of sea-faring that, even if they have been largely disrupted in modern times, were well documented in the nineteenth century and earlier.

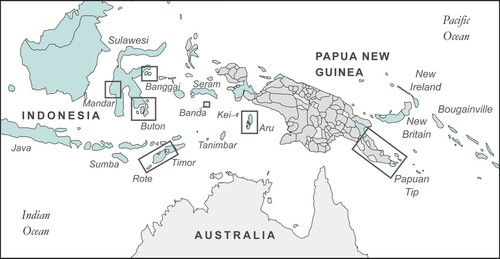

In this article, I will discuss numerous Austronesian languages spoken by peoples both to the east and west of the Australian continent. sets out the locations of the main groups I will mention, marked by boxes. My focus will be on several maritime groups in eastern Indonesia. However, I also mention potential borrowings from Oceanic languages, the nearest of which are the Papuan Tip languages spoken on the eastern ‘tail’ of New Guinea. I restrict myself to languages of Australia’s Arnhem Land, but I note that borrowings from Oceanic languages are very likely to be found in the languages of the Torres Strait and Cape York.

The sources for Austronesian languages I cite are given throughout the text. The following sources are used for Arnhem Land languages, unless otherwise indicated: Anindilyakwa, Leeding (Citation1989); Burarra, Glasgow (Citation1994); Dhuwal, Heath (Citation1980a); Djinang, Waters (Citation1983); Gupapuyngu, Lowe (Citation1975, Citation2014); Nunggubuyu, Heath (Citation1982); Yanyuwa, Bradley (Citation1992); Warndarang, Heath (Citation1980b); and Mara, Heath (Citation1981). For the other languages (unless otherwise marked), the lexemes are cited from the Chirila database (Bowern, Citation2018). I also cite data from Evans (Citation1992, Citation1997) and Walker and Zorc (Citation1981), where indicated. The reader is referred to the sources for those works where they are referenced.

In what follows, I make new proposals for Austronesian loans from South Sulawesi languages (§3.1), from languages in eastern Sulawesi (§3.2), from Sama-Bajau languages (§3.3), from languages in Maluku (§3.4), from languages in the Rote-Timor group (§3.5) and from Oceanic languages (§3.6).

3.1 Loans from South Sulawesi languages

Linguists of Indigenous Australian languages have identified a body of several hundred loanwords from Makasarese. Whilst the list is already impressive, there are certainly more Makasarese loans to be identified. For example, we might add to the list Nunggubuyu baɖili ‘rifle’, a borrowing of Makasarese baʔdiliʔ ‘rifle’ (ultimately from Malay bədil – see Mills, Citation1975, p. 902), or Djinang biraŋ, ‘knife’ from Makasarese beraŋ ‘chopping knife, cleaver’ (Cense, Citation1979, p. 102).Footnote3 There are also two further identifications of borrowings of morphologically complex forms from Makasarese: Gupapuyngu bakura ‘robber’ > Makasarese pa-gorraʔ nmlz-rob ‘robber’ (Cense, Citation1979, p. 238), and Gupapuyngu gucikaŋ ‘pocket’, Burarra kucikaŋ ‘pillow case’ > kocci-kaŋ insert.hand.into-nmlz ‘pocket’ (regular formation < kocciʔ plus -aŋ; Cense, Citation1979, p. 338).

In addition, there is room for refining some of the etymologies for borrowings that have already been identified. For example, Makasarese has two similar wind/directional terms which have been loaned into northern Australian languages, but only one of the Makasarese terms is identified in the literature (resulting in some consternation – see Evans, Citation1992, fn. 40). The Makasarese terms can be differentiated in terms of both the shape and semantics when loaned into northern Australian languages. The first, Makasarese timoroʔ, is borrowed into a large number of northern Australian languages (as in (1)) in reference to an easterly wind, matching the meaning in Makasarese.

| (1) | Yannhangu d̪imuru ‘east wind’, Dhangu d̪imuru(ʔ) ‘east [wind]’, Dhuwal d̪imuru(ʔ) ‘east [wind]’, Djapu d̪imuru(ʔ) ‘east [wind]’, Gumatj d̪imuru(ʔ) ‘east [wind]’, Gupapuyngu d̪imuru(ʔ) ‘east [wind]’, Rirratjingu d̪imuru ‘east’, Mawng cimuru ‘SE trade winds’, Iwaidja cimuru ‘south-easterly trade wind’, Djinang ɟimuru ‘east wind’ < Makasarese timoroʔ ‘east wind, east monsoon’ (Bowern, Citation2018; Evans, Citation1992, p. 84) | ||||

The second is Makasarese timboroʔ which is represented by loans in three languages (2). It is loaned as meaning north(east) wind, but in its original meaning in Makasarese is used for anti-clockwise movement along the coast around South Sulawesi (Jukes, Citation2006, p. 195). The shift in meaning is explainable as a wind from the north(east) would facilitate sailing in an anti-clockwise direction along or near the coast of the Gulf of Carpentaria, where all the languages with the loan are located.

| (2) | Anindilyakwa timpura ‘north wind’, Nunggubuyu d̪imbuɹu ‘northeast wind’, Yanyuwa timpuru ‘easterly wind’ < Makasarese timboroʔ ‘direction/location anti-clockwise around the coast’ (Cense, Citation1979, p. 810; Jukes, Citation2006, p. 195) | ||||

Another set of loanwords in need of etymological correction is given in (3). Evans (Citation1992, p. 84) argues that the source of these items was Malay para-para ‘attic, rack, shelf’ (as opposed to Makasarese para-para ‘grill raised by copper-melting people as a place to put their pots, trellis’). Despite semantic and phonological problems, Evans argues that “[t]his is more likely to be a Malay loan both on semantic grounds and since Malay, but not Makasarese, has dialects containing a uvular r that could be the source of the retroflex in some receiving languages”. In fact, I would argue that the source here is Makasarese ballaʔ-ballaʔ (Makasarese Holle list in Stokhof & Almanar, Citation1984), denoting a raised bench or platform in shade used for resting or sleeping, a piece of material culture widely attested across the Indonesian archipelago. The Malay for this item is bale-bale, which would be expected to be borrowed into northern Australian languages as *pali. A Makasarese etymology, thus, provides both a better semantic as well as phonological match to the Australian forms.Footnote4

| (3) | Iwaidja palapala ‘flat raised surface, table, bed, chair’, Amurdak, Garig palapala ‘bed’, Mawng palapala ‘flat surface, e.g. table’, Mayali palap:ala ‘table, sleeping platform, esp. platform used in tree burials; bed; flat’, Burarra pelapila ‘platform, table, bed frame’, pelampila ‘space, room, large area; spacious, roomy’, Mara palapala ‘tree fork, platform formed by forked sticks’; Yanyuwa na-walabala ‘forked stick/pole’ (Evans, Citation1992, p. 84) | ||||

Another proposition for future loan research and identification in northern Australia is the possibility of contributions from other South Sulawesi groups. We already noted above that, while it is very likely Bugis people were part of the crews on Macassan ships, there have been no specifically Buginese loans identified. However, there is another very significant maritime group belonging to the South Sulawesi subgroup – the Mandar, a people located to the north of Makasar (van Vuuren, Citation1917a, Citation1917b). I tentatively suggest that the borrowing in (4) might be taken to support positing Mandar–Australian contact. Mandar provides a near-perfect phonological match for the form in Anindilyakwa. By contrast, the medial /m/ in the related Makasarese item would be expected to be retained as /m/ when borrowed; the Buginese and Malay forms also display problems that exclude them as being plausible sources for borrowing.

| (4) | Anindilyakwa pacanaŋa ‘lantern’ < Mandarese paʤanaŋan ‘lamp’, cf. Makasarese paʤamaŋaŋ, Bugis pademaɲeŋ ‘lamp’ (Holle lists in Stokhof & Almanar, Citation1984), Malay panʤut ‘torch (made of resin wrapped in leaves)’ (Stevens & Schmidgall-Tellings, Citation2010, p. 707)Footnote5 | ||||

It must be noted that because trade to China – the only market for sea cucumber – was known to be centred in the city of Makasar in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a large role for Mandar sailors in Australia is highly unlikely. But in light of this one form, Mandarese is perhaps worthy of consideration for loans identified as of unknown origin in subsequent work.

3.2 Loans from East Sulawesi languages

Whilst Makasarese has rightly been the focus of Australianists in the search for the sources of borrowings in northern Australia, there were other indigenous states in eastern Sulawesi which had significant maritime expertise and widespread trading networks in the eastern half of the Indonesian archipelago, particularly in the period before the rise of Makasar.

The groups of Southeast Sulawesi are particularly worthy of note. Most significant was the Buton (also called the Wolio) state, covering the island territories near the southeastern parts of Sulawesi, including the islands of Buton, Muna, Kabaena and Tukang Besi, and the two regions of Rumbia and Poleang on Sulawesi. The peoples of this group were important maritime traders from at least the sixteenth century (Velthoen, Citation2002). Even after coming under the control of Makasar in the seventeenth century, they maintained a strong maritime presence in eastern Indonesia. For example, Ligtvoet (Citation1878, p. 9) writes:

The main livelihood of the Butonese is trade and sailing … . To the west, Butonese vessels travel as far as Singapore. But it is particularly in the eastern part of the Indonesian archipelago that they are found in great numbers, often serving as shippers of cargo.

There are about 30 languages of Southeast Sulawesi belonging to two main groups, Muna-Buton and Bungku-Tolaki (Mead, Citationin press). Searching dictionaries and wordlists for these languages against lists of borrowing in northern Australian reveals some promising leads. For example, Evans (Citation1992, p. 84) tentatively suggests a link between the Burarra form in (5) and Bajau rakaʔ ‘fasten, tether with a short rope’. However, a better semantic match is provided by Proto-Southeast Sulawesi *rakoq ‘catch’ (from Proto-Malayo Polynesian *dakep ‘embrace’; Mead, Citation1998, p. 466), which has reflexes throughout the group. With a source from among these languages, the final /-wa/ of Burarra form can be provided for with the third singular object pronoun which is often used in citation forms of transitive verbs (cf. Mead, Citation1998, p. 77).

| (5) | Burarra ɹakawa ‘catch fish with hook and line’ (Evans, Citation1992, p. 84) Southeast Sulawesi: Wolio rako ikane ‘catch fish’, Muna rako ‘catch, capture’, Kulisusu mo-rako ‘catch’ (e.g. fish); Mori Bawah rako-o ‘catch-3sg’, Padoe rako-ʔo ‘catch-3sg’ (Holle lists in Stokhof & Almanar, Citation1985; Mead, Citation1998, p. 466) | ||||

While a single match may be regarded as chance, a brief search of semantic domains of lexemes for which borrowing was likely to have occurred yielded further forms, such as the lexeme for ‘knife’ in (6). Walker and Zorc (Citation1981, p. 122) explain this as Makasarese borrowings involving a ‘prefix denoting use’ maʔ- + ladiŋ ‘knife’.Footnote6 This etymology offers up problems because the prefix maʔ- (actually an amalgamation of prefixes – see Jukes, Citation2006, p. 263) is used on nouns to derive verbs; the nominal meaning of the borrowed form in the Indigenous Australian languages is therefore unexplained. An alternative explanation is that this form is a borrowing from a Southeast Sulawesi language, such as Muna malati ‘knife’. Forms likely related to this can still be found at the very fringes of eastern Indonesia, in Aru and Sumba (examples given in (6)). This pattern is consistent with malati being an older word for a sharp metal implement that has been replaced in most northern Australian languages by words from subsequent waves of contact, particularly from South Sulawesi.

| (6) | Gumatj malati ‘knife’ (Bowern, Citation2018) Southeast Sulawesi: Muna malati ‘kitchen knife’ (van den Berg & Sidu Marafad, Citation2016) Aru: Kola malat, Dobel malatu ‘kind of iron tool’ (Nivens, Citationn.d.) Sumba: Kambera malati ‘sort of knife of European manufacture’ (Onvlee, Citation1984, p. 257), Lolina malati ‘knife’ (Lobu, Citation2010, p. 37) | ||||

The idea that metal implements may in some cases have older, non-Makasarese sources is supported by the historical record. In the sixteenth century, eastern Sulawesi states, particularly the Banggai, were significant in the distribution of iron and iron products eastwards.Footnote7 Velthoen (Citation2002, p. 102) even suggests that the Banggai were travelling to Australia:

By the seventeenth century, Banggai was growing spices for external trade, but also continued to participate in local and regional trade in Maluku, as it was a convenient stepping stone on the journey to the eastern islands including Alor and even northern Australia.

Future research could look to Eastern Sulawesi languages, such as Banggai, and Southeastern Sulawesi languages, such as Muna and Wolio, as potential sources for metal implements and maritime vocabulary in northern Australia that cannot be traced to Makasarese and Malay.

3.3 Loans from Sama-Bajau languages

The Sama-Bajau, or simply ‘Bajau’, are an ethnolinguistic group known for their seaborne lifestyle. Speaking a handful of closely related languages, the Sama-Bajau are widely present in the Sulu islands and around the coast of Mindanao in the Philippines, as well as in parts of northern and eastern Borneo, Sulawesi and throughout much of eastern Indonesia. Fox (Citation1977, Citation2005) argues that the Bajau were present in northern Australia at the time of the Macassan sea cucumber trade. This is confirmed by the eye-witness account of Earl (Citation1846, p. 65), who notes seeing them near Port Essington and admiringly describes them as “that singular people the Badju, a tribe without fixed home, living constantly on board their prahus, numbers of which congregate among the small islands near the southern coast of Celebes”.

Yet, little to no linguistic evidence of Bajau interaction with or impact on Australian Indigenous groups has been identified to-date. Despite a search for possible Bajau loans, Walker and Zorc (Citation1981, p. 117) offered only one loan candidate from Bajau but admitted its weakness. Evans (Citation1992, p. 84) put forward two very tentative possibilities for borrowings from Bajau (one of which, Burarra ɹakawa, was discussed in the preceding section), while Evans (Citation1997, p. 237) states that there are no unambiguous candidates for loans from Bajau.

On examination of the available material, one loan from Bajau appeared plausible. The ‘harpoon’ set in (7) was noted by Walker and Zorc (Citation1981, p. 129) as a possible Austronesian loanword. It finds a very good phonological and semantic match in the eastern Indonesian variety of Sama-Bajau documented by Verheijen (Citation1986).

| (7) | Gupapuyngu baːkala(ʔ), Dhangu baːkala(ʔ), Dhuwal baːkala(ʔ), Gumatj baːkala(ʔ) ‘harpoon head – with hook on one side (for hunting whales, dugong, turtle)’, Djinang bakala ‘harpoon hook’ (Bowern, Citation2018) | ||||

Lesser Sunda Islands Bajau bakal ‘kind of harpoon used to spear turtles’ (Verheijen, Citation1986, p. 64) | |||||

3.4 Loans from Maluku languages

Trade networks also flourished among numerous indigenous groups of Maluku located to the east of Sulawesi. Most notable prior to the European arrival were the Bandanese who had already established a mercantile society around the production and trade of nutmeg and mace. The apparatus to support the Banda industry involved extensive inter-island trade with other parts of Maluku, particularly Seram, Kei and Aru, all of which were crucial in supplying food to the Bandanese population (Villiers, Citation1981). Given Maluku’s extensive maritime culture and the proximity to Australia, it is surprising that no evidence of contact between the two has come to light.

Reid (Citation2018) proposes that it is amongst coastal marine resources other than sea cucumber for which we should look for a longer history of contact between Maluku and Australia. The area of eastern Maluku bordering on the Arafura Sea was well known for its pearls and pearl shell as well as its tortoise shell from at least the early seventeenth century, but the historical demand for those items is much older, significantly predating that for sea cucumber. Reid’s (Citation2018) suggestion is that indigenous Moluccan groups engaged in the collection of these items to sell on to traders connected to global markets may have visited northern Australia as part of their collecting. I have noted a likely loan set in northern Australia that could be taken to support such a scenario.

Items of similar form denoting hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) are present in different northern Australian language families, as set out in (8).Footnote8 Strikingly similar form-meaning pairings are found throughout the Austronesian languages of the Aru Islands and *kaloba ‘hawksbill turtle’ regularly reconstructs to their common ancestor, Proto-Aru. Elsewhere in Maluku this form is not found, with most places having terms reflecting *keRaŋ ‘hawksbill turtle’, a reconstruction to Proto-Central Eastern Malayo-Polynesian, a higher level of the Austronesian family.

| (8) | Nunggubuyu gaɾuba ‘hawksbill turtle’, Anindilyakwa karipa ‘turtle shell of hawksbill turtle’, Yanyuwa karubu ‘hawksbill turtle’, Warndarang gaɾubu, Mara karupu ‘hawksbill turtle’, Gupapuyngu garupu ‘turtle shell’ Aru: Kola kaloba, Batuley kalab, Karey kalabo ∼ kalaba, West Tarangan kaloba, Dobel ʔaloba < Proto-Aru *kaloba ‘hawksbill turtle, Eretmochelys imbricata’ (Nivens Citationn.d.). | ||||

Positing borrowing from Aru languages into northern Australian ones is complicated by the fact that there is a widespread term in Sulawesi languages that is again similar in form to both the northern Australian and the Aru language forms, as seen below. These items appear to be reconstructable to the highest level of relatedness in the Sulawesi languages, but are not known to be reflected in Makasarese.Footnote9 Aru languages provide a better semantic match to the northern Australian forms, because in both sets of languages they denote the same specific turtle species, whereas the terms in the Sulawesi languages appear to have generic reference. Both the Aru and Sulawesi sources present difficulties for the fact that their medial l is borrowed as r; Evans (Citation1992, pp. 60–62) suggests that items with this unexpected change may belong to an earlier loan stratum.

Sulawesi: Pamona, Wotu, Wolio kolopua < Proto-Kaili-Wolio *kolopua, Tukang Besi kolopua, Cia-Cia kokolupua, Muna kokolopua, Proto-Bungku-Tolaki *kolopua < Proto-Celebic *kolopuan ‘turtle’; South Sulawesi: Mandar kalapuaŋ, Toraja kalapuan, Bugis kalapúŋ (Zobel, Citationn.d.)

To explain the three-way similarity in the forms under discussion, I posit that the northern Australian lexical items were borrowed from one or more Aru languages, but that the Aru languages themselves had borrowed their term from Sulawesi traders who particularly sought the hawksbill turtle from them. The historical record provides us with clear evidence that traders from Sulawesi did not gather these marine products in Aru themselves, but this was staged through trading villages on the western side of Aru. For example, in a VOC letter dated 1645, a clear picture of the established trade connections in Aru is set out:

The most important potential source of profit for the Honourable [Dutch East India] Company lies in amber and tortoise shell, and in the pearls which are definitely to be found there (although it is not known in what quantity). These valuable items come from large oysters pulled out of the sea by the inhabitants of the eastern coasts of Aru, from a depth of 1–2 fathoms, around the villages of Karey, Akerey, Workay, and Mariri. […] [E]ach year the produce of these four villages […] is brought to the villages of Wokam, Ujir and Wamar on the northwestern coast, the inhabitants of which then sell them to the Javanese, Makasarese, and others (Heeres, Citation1896, pp. 268–269)

Another possible set of loans in northern Australia that originates in Maluku languages are presented in (9). Evans (Citation1992, p. 83) presents these lexemes in Indigenous Australian languages as borrowings of Malay gəlaŋ which he gives as ‘cylindrical fastenings, incl. metallic’. To my knowledge, gəlaŋ refers chiefly to decorative items worn on the body that clasp the arms or legs; it is most frequently translated into English as ‘bracelet’.Footnote10 This does not provide a good semantic match to the fishing-related terms in the Australian languages. The Aru languages, by contrast, are a good semantic match, showing a similar range of meanings to do with hook and line fishing. However, there are phonological problems as the i in the Aru forms might be expected to be maintained as i in the Australian languages.

| (9) | Amurdak kalaŋ ‘fishing line’, Burarra kalaŋ ‘hook, fish-hook’, Mawng kalaŋ ‘fishing’ Evans (Citation1992, p. 83) Aru: Kola kalin ‘fishing line’, Ujir kalidi ‘fishing hook’, Batuley kaliŋ ‘fishing line’, West Tarangan kaliŋ ʤisin ‘fishing hook’ (Nivens, Citationn.d.) | ||||

The peoples of Eastern Seram were active maritime traders across the whole of Maluku, extending to New Guinea, Aru and Timor in the early modern period (Ellen, Citation2003). What is more, it is known that people from Eastern Seram ventured past Aru and into the Torres strait where they traded iron and tobacco with the peoples of southern New Guinea and Cape York (Swadling, Citation1996, pp. 155–165). It would therefore not be surprising if people from Eastern Seram also visited the Arnhem Land region. The lack of lexical documentation of the Eastern Seram languages means that, at present, it is impossible to investigate this possibility further.

3.5 Loans from Timor-Rote languages

We saw in §2 that Earl’s historical account notes that Timorese were present in the crews of Macassan ships. Kupang, at the far western end of Timor, was, by the middle of the nineteenth century, a centre for the sale of sea cucumber for ships returning from Australia.Footnote11 Prior to the discovery of the sea cucumber fields on the Australian coast, groups from Sulawesi had been visiting the area around Kupang for the collection of sea cucumber to sell for some time. The people of Rote Island, just off the western tip of Timor near Kupang, and the Helong and Amarasi located around Kupang, were well known as fishermen in their own right and many still today exercise their traditional rights to access Australian territorial waters for fishing (see Stacey, Citation2007, pp. 57–81 for a brief history).

There is one lexeme that indicates that these peoples may not have been content to just crew on Macassan ships, but may have undertaken their own voyages to Australia for the collection and sale of sea cucumbers. Alongside the many borrowings of Makasarese taripaŋ ‘sea cucumber’ in northern Australia, there is a second term found in the languages given in (10). While Djinang, Gupapuyngu and Yan-nhangu are closely related, Burarra belongs to a distinct language family. The presence of related lexemes for sea cucumber in these languages suggests borrowing has played a role here. These resemble the lexemes for ‘sea cucumber’ in the Austronesian languages spoken in the western half of Timor and nearby Rote (see Edwards, Citation2021 for an overview of these languages and their relationships). While this is only a single lexical similarity, the resemblance and the phonological match (f > p, unstressed a [ɐ] > u) is striking.

| (10) | Djinang buɳapi, Yan-nhangu buɳapi, Gupapuyngu buɳapi, Burarra buɳapi ‘sea cucumber’ Timor-Rote: Helong hnahe ‘sea cucumber’ (Jonker, Citation1908, p. 373); Tetun banahi (Morris, Citation1984, p. 10) ‘round edible shellfish’; Amarasi blafi ∼ brafi, Termanu nafi ‘sea cucumber’ (Jonker, Citation1908, p. 373) < Proto-Rote-Meto *ɓanafi ‘sea cucumber’ (Edwards, Citation2021) | ||||

No other Austronesian languages in eastern Indonesia provide such close matches to the Australian sea cucumber terms in (10). Whilst the second part of the sea cucumber lexeme is almost certainly related across eastern Indonesian languages (potentially reflecting a form like Proto-Central Malayo-Polynesian *amb[u]i ‘sea cucumber’), outside of Timor-Rote the languages lack the initial syllable with the bilabial oral stop, cf. Aru: Kola (mat)apui, Batuley (mat)fui, Karey (mat)ahui; Kei-Tanimbar: Yamdena (lel)embi, Fordata ebi, Kei ieb; Southwest Maluku: Luang (ni)awi, Leti (vni)aβi ‘sea cucumber’. The only other languages I am aware of with the initial bilabial plus nasal combination in the area are the Papuan languages of Pantar Island to the north of Timor (e.g. Nedebang buna, Teiwa banai, Western Pantar banai, Blagar bene ‘sea cucumber’), but these are most likely themselves borrowings from West Timorese languages. Another Papuan language spoken at the western edge of New Guinea (mentioned already in §3.4), Kalamang, has unapi ‘species of sea cucumber’ (Visser, Citation2020). This is almost certainly related to the forms in (10) and suggests that the Eastern Seram languages may again have been involved in the transfer of this term.

A possible second item supports seeing the Timor-Rote languages as a source for borrowing in northern Australia. Whilst there are numerous borrowings of Makasarese tambako ‘tobacco’ in northern Australia (Evans, Citation1992, p. 81), Yanyuwa has the archaic form given in (11), offering a good form-meaning match to that in various western Timor-Rote languages.

| (11) | Yanyuwa mada ∼ muda (archaic speech) ‘tobacco for smoking, tobacco for chewing (avoidance speech)’ Timor-Rote: Amarasi maro ‘tobacco’, Termanu modo ‘tobacco, medicine, green (of leaves)’ (Jonker, Citation1908, p. 359), Uab Meto malo ‘medicine’ < Proto-Rote-Meto *maɗo ‘medicinal plant’ (Edwards, Citation2021) | ||||

Given these potential borrowings, I tentatively suggest that future work could also target western Timor-Rote languages in looking for sources for suspected loans in northern Australia.Footnote12

3.6 Loans from Oceanic languages

Thus far we have only considered Austronesian languages to the west as possible sources for borrowings in northern Australia. However, the sea-faring skills of the Austronesians took them throughout the Pacific. The Austronesian languages to the east of Australia belong to the Oceanic subgroup and it is to these that we now turn our attention.

In my examination of suspected loan materials from northern Australian languages, the forms for the wind terms in (12) stood out as probable borrowings from Oceanic. Leeding (Citation1989, p. 276) identifies the Anindilyakwa form as a loan whose source is unknown, apparently on account of the alveolar phoneme which was not part of the traditional phonological system. These Anindilyakwa and Nunggubuyu lexemes are good semantic matches to the reconstructed Proto-Oceanic lexeme *raki, some reflexes of which are provided below. Cognates of Proto-Oceanic *raki are also evidenced to the west of Australia in Southwest Maluku languages, leading Blust and Trussel (Citationongoing) to reconstruct Proto-Central Eastern Malayo-Polynesian *raki ‘wind from the northeast’. The different semantics of the term in these Maluku languages indicate they cannot be the source of these borrowings in Australia. The initial ma- on the Australian forms can be explained as an enclitic directional ‘hither’ term derived from Proto-Oceanic *maRi ‘come’ (see Ross, Citation2003a, pp. 280–283 on such directional uses). The comparison is weakened by the unexplained vowel metathesis in the Australian language forms.

| (12) | Anindilyakwa ma-maɹika ‘veg-southeast trade winds’, Nunggubuyu maɹiga ‘cold south to southeast wind (dominant wind in early dry season around April to June)’ Oceanic: Lou ra ‘northeast, northeast wind’, Titan nray ‘wind from the mainland, mountain breeze, blows at night’, Kove hai ‘southeast trade, year’, Bariai rai ‘year’, Gitua rak ‘southeast trade’, Lukep rai ‘year’, Mangap rak-rak ‘fresh morning (during windy season)’, Tami lai ‘southeast trade’, Maleu na-lai ‘southeast trade’, Ali rai ‘southeast trade’, Tumleo riei ‘southeast trade’< Proto-Oceanic *raki ‘southeast trades’ (probably also ‘dry season when the southeast trades blow’) (Ross, Citation2003b, pp. 131–133) Southwest Maluku: Wetan rai ‘north’, Luang raʔi ‘north’, Leti rai ‘north’, Kisar raʔi ‘north’, Central Marsela enen raje ‘north wind, […] called the father of the winds on Marsela because it blows so hard and can cause great damage’ (Toos van Dijk, pers. comm.) | ||||

If this term is indeed a borrowing from an Oceanic language, it indicates that speakers of Austronesian languages were moving westward through the Torres Strait into the Gulf of Carpentaria with the southeast trade winds, which blow consistently from May to September. It is known that in the nineteenth century long-distance trade was conducted across the Torres Strait by the Motu people, an Austronesian-speaking group located on the southeastern coast of New Guinea (Skelly & David, Citation2017). Surprisingly, however, neither the Motu language nor any other Oceanic language of the Papuan Tip subgroup, the closest set of Oceanic languages, has a reflex of Proto-Oceanic *raki. This suggests that the Austronesian language from which the term was borrowed into Anindilyakwa and Nunggubuyu was not spoken by a group involved in the well-known Torres Strait trade cycles, but one further afield.

There is also a more recent layer of borrowing from Oceanic languages that appears to date from the late nineteenth century at the earliest. In the first place, the forms for items of clothing in two languages of northern Australia given in (13) show striking similarity to forms found amongst Oceanic languages reflecting an apparent Proto-Oceanic reconstruction *sulu ‘loincloth’. Osmond and Ross (Citation1998, p. 99), however, cast doubt on the validity of this item as a Proto-Oceanic reconstruction. They relegate it to Proto-Central Polynesian or Proto-Polynesian stating that the term and garment were brought to New Guinea by Fijian and Polynesian missionaries in the nineteenth century.

| (13) | Yanyuwa culu ‘loincloth’,Footnote13 Dhuwal cuːlu ‘cloth’ Oceanic: Kilivila sulu ‘loincloth’, Misima sulu ‘wrap around skirt used by men’, Fiji i-sulu ‘cloth, clothing’, Tongan hulu ‘tuck in end of loincloth’ | ||||

A second borrowing set also points to borrowing from Oceanic languages, likely early in the twentieth century. The forms for the ‘knife’ lexemes in a cluster of languages in northern Australia given in (14) look to be the western-most exemplar of a widespread borrowing set originating in German Säge ‘saw’. This borrowing goes back to German speakers based at the Lutheran Neuendettelsau Mission in the Huon Gulf. Beginning in the early 1900s, the church promoted languages, Jabêm and Kâte, for use among Austronesian and Papuan communities, respectively (Paris, Citation2012). From here, borrowings of Säge ‘saw’ spread through Austronesian and Papuan languages around New Guinea including in the Torres Strait. Examples are listed in (14).

| (14) | Yan-nhangu jiki ‘knife’, Djinang jiki ‘knife; any sharp steel tool, e.g. knife, axe, machete, etc.’, Gumatj jiki(ʔ), Gupapuyngu jiki(ʔ), Dhangu jiki(ʔ), Djapu jiki(ʔ), Dhuwal jiki(ʔ) ‘knife (small or generic), blade (anything sharp made of iron or steel)’ (Bowern, Citation2018) Oceanic: Jabêm sege ‘saw’, Motu sege-a ‘sharpen (knife, axe)’, Sudest siki ‘peel’, Misima-Panaeati hiki ‘graze the skin, peel yams’, Mengen sigi ‘edge, tip, shoulder’ Papuan: Kâte sege ‘saw’, Guhu-Samane sigi ‘sharp edge of things’, Somba-Siawari sege ‘saw’, Suena sege ‘carpenter's saw’, Dadibi sigi hwa ‘axe’, Mountain Koiali siga ‘knife’, Rotokas sigo ‘knife’, Murik segen ‘saw (tool)’ | ||||

As such, I suggest that an examination of Oceanic languages could be profitably undertaken in comparison to the lexicons of northern Australian languages, particularly in and near the west of the Gulf of Carpentaria.

4. Concluding discussion

In this article I have drawn attention to lexemes with limited distributions in northern Australian languages that show resemblances to lexemes with similar meanings in Austronesian languages both to the east and west of Australia. The value of these in suggesting, let alone demonstrating, contact between speakers of Australian and Austronesian languages may be reasonably questioned by the reader. It may be possible to discount these as the sort of chance resemblances that can be found between any two languages. This certainly seems to be the case with the rather tenuous connections made in O’Grady and Tryon (Citation1990). To mitigate this issue, I have restricted myself in this article to looking at lexical items denoting known trade products and vocabularies connected with sailing and fishing. Moreover, I have tried to situate my speculations of linguistic contact within known histories of Austronesian maritime practices and trade.

Still, there remains a significant methodological problem facing the linguist wanting to reconstruct contact which is further back in time or where the interaction was only fleeting. In such situations we would only expect there to be a small number of loanwords to provide any evidence of prehistorical contact. Where subsequent or contemporaneous contact with a more prestigious, dominant contact group has taken place, we might expect that lexical items from other groups would be replaced or greatly reduced in number. In the case of Makasarese, Earl (Citation1846, p. 244) leaves his reader in no doubt about the thoroughgoing influence of the language on the linguistic ecology of northern Australia:

A very considerable portion of the coast natives have, from frequent intercourse with the Macassar trepang fishers, acquired considerable proficiency in their language … . They, however, contrive to make themselves well understood, not only by the Macassars, but by the people of tribes with whose peculiar dialect they may not be familiar. On our first arrival, the natives, from having been long accustomed to address strangers in this language, used it when conversing with us, and the consequence was, that some vocabularies were collected which consisted almost entirely of this patois, under the supposition that it was the language of the aborigines.

At the same time, the lexical material adduced in this article could be seen as reason for optimism for future studies using linguistics to reconstruct Australian contact with Austronesian groups. Several of the proposed loanwords discussed here have not appeared on previous lists of suspected borrowings; this could be taken to suggest that more non-Macassan loanwords are awaiting identification. Future work on this topic will be greatly aided by continuing improvements to our understanding of loanword transmission between languages in Arnhem Land. Notable amongst recent work in this area is Aung Si’s (Citation2019) study setting out clear pathways of loanword movement for lexemes denoting a range of biota. Most interesting for our purposes are cases of lexemes referring to plants or animals that are found widely in Indonesia that can be shown to have been transmitted from the coast to the interior of Arnhem Land. For example, the cabbage palm Corypha utan has a very restricted geographical distribution in Arnhem Land and lexemes for C. utan are demonstrated by Aung Si (Citation2019, p. 11) to have moved inland from the Arafura Swamp region. By contrast, C. utan is found across eastern Indonesia, where it is used extensively in material culture production. These features make lexemes for Corypha utan, and others like them, prime candidates for future investigation as loanwords from the languages of sea-faring Austronesians.

Uncovering linguistic evidence of non-Macassan traffic between Asia-Pacific and Australia will require advanced knowledge of Austronesian lexical diversity. In this article, I have highlighted the lexicons of Austronesian languages of Eastern Sulawesi (particularly those of Southeast Sulawesi), of Eastern Seram, of Western Timor-Rote and even of the Oceanic subgroup as meriting closer inspection in the future. However, it is important to bear in mind that with trade routes and trading alliances shifting over time, these languages may also have experienced lexical replacement in the domain of key trade items. For this reason, it may be that the original sources of many loanwords in Australian languages cannot be identified. This paper has, nonetheless, highlighted that by looking widely at the lexicons of languages in eastern Indonesia, we can identify lexical forms at the fringes that bear striking resemblances to forms with similar meanings in the languages of Arnhem Land. Understanding the distributions of the relevant lexemes in eastern Indonesian languages allows us to posit likely sources from which, and trade routes along which, loanwords were dispersed before ultimately making their way into the languages of northern Australia.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Rachel Hendery, Campbell Macknight, David Mead, Edgar Suter and Erik Zobel for discussion of data and ideas for this article. The comments of two anonymous reviewers also contributed to improving the clarity of this article. All errors are my own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Data availability statement

This paper is based on publicly available information and therefore no data availability statement is provided.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Antoinette Schapper

Antoinette Schapper is currently a Senior Lecturer in Linguistics at the Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam.

Notes

1 Throughout this article, I use ‘Makasar’ to refer to the city and indigenous state of the Macassans and ‘Makasarese’ to refer to their language. Following the established practice in the Australianist literature, I use ‘Macassan’ to designate people and things originating from Makasar.

2 Various authors in a recent volume, Macassan History and Heritage: Journeys, Encounters and Influences (Clark & May Citation2018), claim involvement for both Butonese (Southeast Sulawesi) and Madurese (Java) peoples, citing Fox and Sen (Citation2002). In my reading of the text, Fox and Sen (Citation2002) do not claim this, but merely point out that these peoples represent widespread fishing ethnicities in modern eastern Indonesia.

3 Both Evans (Citation1992, p. 84) and Walker and Zorc (Citation1981, p. 127) note borrowings of Malay paraŋ ‘machete’, but not the Makasarese form given here. Walker and Zorc (Citation1981, p. 114) also mention Yolŋu Marta biŋal, which appears to also be an instance of borrowing Makasarese beraŋ, but with unexpected metathesis of nasal and liquid and irregular r > l.

4 An anonymous reviewer points out that the correct etymology is given in a later publication (Evans, Citation2009, p. 170).

5 Traditionally, these ‘lamps’ in Indonesia consisted of long thin sticks of split bamboo wrapped with a pounded mixture of kapok and an oil-containing plant. For the latter, the nuts of Calophyllum inophyllum or Aleurites molucana were originally used but were later widely replaced with those of the introduced plants, Jatropha curcas and Ricinus communis. In many languages across Indonesia, we find forms similar to those given in (4), typically spread by borrowing, used in reference to the lamps and one or more of the plants used in their production (Verheijen, Citation1984, pp. 74–75).

6 There are numerous straightforward borrowings of Makasarese ladiŋ – see Evans (Citation1992, p. 75).

7 Tomé Pires visited Ternate in the first decade of the sixteenth century and recorded: “A great deal of iron comes from outside, from the islands of Banggai, iron axes, choppers, swords, knives” (Cortesao, Citation1944, pp. 215–216). In the sixteenth century Duarte Barbosa visited the Moluccas and wrote of Banggai: “Not very far off from these islands [North Maluku], to the west-south-west, at thirty leagues away, there is another inhabited … island called Bangaya. Much iron is found there which is taken to divers countries” (Dames Citation1918–Citation1921, p. 205).

8 Another set of apparently borrowed turtle words can be perceived in the northern Australian data: Dhuwal gariwa ‘flatback turtle, Chelonia depressa’, Ritharngu gaɾiwa ‘flatback turtle’, Burarra gariwa ‘green turtle’. Although similar in form to the hawksbill terms, they all lack a bilabial stop and have instead a /w/ and /i/. This set seems to represent a distinct, though likely related, borrowing set.

9 Malay is not a Sulawesi language and therefore would not be expected to have a reflex of this item.

10 Stevens and Schmidgall-Tellings (Citation2010, p. 305) give the following definitions of gəlang: “1: bracelet, circular band, bangle; 2: ring, washer, girdle, race”.

11 Accounts from the first half of the nineteenth century, like that of Phillip Parker King, suggest that Kupang was not a trading point in itself in the beginning, but just a way point for ships from Sulawesi to harbour at on their voyage to Australia.

12 Evans (Citation1992, p. 87) suggests that water buffalo were brought to northern Australia from Timor. The forms he gives do not correspond to any forms that I am aware of in Timor. In a personal communication, he suggests that a Malay form like anak kerbau ‘young of water buffalo’ may provide a better match.

13 Evans (Citation1992, p. 86) notes that Bradley, in an unpublished manuscript, gives the Yanyuwa form as a borrowing of Makasarese sulu ‘wrap-around piece of material’. This etymology is not given in the published version (Bradley, Citation1992). As Evans notes, there is no known Makasarese word with this form. Indeed, this form is not known to be found outside Oceanic languages.

References

- Blust, R., & Trussel, S. (ongoing). Austronesian Comparative Dictionary. https://www.trussel2.com/ACD/.

- Bowern, C. (2018). Chirila Database, version 2.0, February 2018. Yale University. http://chirila.yale.edu/.

- Bradley, J. (1992). Yanyuwa wuka: Language from Yanyuwa country, a Yanyuwa dictionary and cultural resource. University Library.

- Cense, A. A. (1952). Makassaars–Boeginese prauwvaart op Noord-Australië. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, 108(3), 248–265. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/22134379-90002431

- Cense, A. A. (1979). Makasaars – Nederlands woordenboek. Nijhoff.

- Clarke, A. F. (1994). Winds of change: an archaeology of contact in the Groote Eylandt archipelago, Northern Australia [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. The Australian National University.

- Clark, M., & May S. K. (2018). Macassan history and heritage: Journeys, encounters and influences. ANU Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22459/MHH.06.2013

- Collins, G. E. P. (1936). East monsoon. Cape.

- Collins, J. T. (2003). Language death in Maluku: The impact of the VOC. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië, 159(2), 247–289. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/22134379-90003745

- Cortesao, A. (1944). The Suma oriental of Tome Pires and The book of Francisco Rodrigues (2 volumes). Hakluyt Society.

- Dames, M. L. (1918–1921). The book of Duarte Barbosa: An account of the countries bordering on the Indian Ocean and their inhabitants. (2 volumes). Hakluyt Society.

- Earl, G. W. (1846). On the Aboriginal tribes of the northern coast of Australia. Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, 16, 239–251. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1798232

- Edwards, O. (2021). Rote Meto comparative dictionary. ANU Press.

- Ellen, R. F. (2003). On the edge of the Banda zone: Past and present in the social organization of a Moluccan trading network. University of Hawai'i Press.

- Evans, N. (1992). Macassan loanwords in Top End languages. Australian Journal of Linguistics, 12(1), 45–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07268609208599471

- Evans, N. (1997). Macassan loans and linguistic stratification in western Arnhem Land. In P. McConvell, & N. Evans (Eds.), Archaeology and linguistics: Aboriginal Australia in global perspective (pp. 237–260). Oxford University Press.

- Evans, N. (2009). Doubled up all over again: Borrowing, sound change and reduplication in Iwaidja. Morphology, 19(2), 159–176. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-009-9139-4

- Fox, J. J. (1977). Notes on the southern voyages and settlements of the Sama-Bajau. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, 133(4), 459–465. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/22134379-90002606

- Fox, J. J. (2005). In a single generation: A lament for the forests and seas of Indonesia. In P. Boomgaard, D. Henley, & M. Osseweijer (Eds.), Muddied waters: Historical and contemporary perspectives on management of forests and fisheries in Island Southeast Asia (pp. 43–60). KITLV Press.

- Fox, J. J., & Sen, S. (2002). A study of socio-economic issues facing traditional Indonesian fishers who access the MoU box. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities.

- Glasgow, K. (1994). Burarra-Gun-nartpa dictionary with English finder list. Summer Institute of Linguistics.

- Heath, J. G. (1980a). Dhuwal (Arnhem Land) Texts on kinship and other subjects: With grammatical sketch and dictionary. (Oceania Linguistic Monograph, 23.) University of Sydney.

- Heath, J. G. (1980b). Basic Materials in Warndarang: Grammar, texts and dictionary. Pacific Linguistics.

- Heath, J. G. (1981). Basic Materials in Mara: Grammar, texts and dictionary. Pacific Linguistics.

- Heath, J. G. (1982). Nunggubuyu dictionary. AIAS.

- Heeres, J. E. (1896). Documenten betreffende de ontdekkingstochten van Adriaan Dortsman. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, 46(1), 608–719. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/22134379-90000095

- Jonker, J. C. G. (1908). Rottineesch–Hollandsch woordenboek. Brill.

- Jukes, A. (2006). Makassarese (basa Mangkasara’): A description of an Austronesian language of South Sulawesi [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Melbourne.

- Leeding, V. (1989). Anindilyakwa phonology and morphology [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Sydney.

- Ligtvoet, A. (1878). Beschrijving en geschiedenis van Boeton. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Landen Volkenkunde, 4(2), 1–112.

- Lobu, O. (2010). Kamus Bahasa Lolina. Dinas Kebudayaan dan Pariwisata Kabupaten Sumba Barat.

- Lowe, B. (1975). Gupapuyngu conversational course. Adult Education Centre.

- Lowe, B. (2014). Gupapuyŋu interactive dictionary. ARDS Aboriginal Corporation. URL: https://ards.com.au/static/pages/Gupapuyngu/lexicon/main.htm.

- Macknight, C. (1976). Voyage to Marege': Macassan trepangers in northern Australia. Melbourne University Press.

- Macknight, C. (2008). Harvesting the memory: Open beaches in Makassar and Arnhem Land. In P. Veth, P. Sutton, & M. Neale (Eds.), Strangers on the shore: Early coastal contacts in Australia (pp. 133–147). National Museum of Australia.

- Macknight, C. (2018). Studying trepangers. In M. Clark, & S. K. May (Eds.), Macassan history and heritage: Journeys, encounters and influences (pp. 19–39). ANU Press.

- Mead, D. E. (1998). Proto-Bungku-Tolaki: Reconstruction of its phonology and aspects of its morphosyntax [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

- Mead, D. E. (in press). Historical linguistics of Sulawesi. In K. A. Adelaar, & A. Schapper (Eds.), The Oxford guide to the Malayo-Polynesian languages of Southeast Asia. Oxford University Press.

- Mills, R. F. (1975). Proto-South Sulawesi and Proto-Austronesian phonology [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

- Morris, C. (1984). Tetun–English dictionary. Pacific linguistics.

- Nivens, R. (no date). Dictionary of Proto-Aru. Unpublished Toolbox files.

- Noorduyn, J. (ed.). (1983). Nederlandse historische bronnen 3. Amsterdam. https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_ned017198301_01/.

- O’Grady, G. N., & Tryon, D. T. (1990). Early Austronesian loans in Pama-Nyungan. In G. N. O’Grady, & D. T. Tryon (Eds.), Studies in comparative Pama-Nyungan (pp. 105–116). Pacific Linguistics.

- Onvlee, L. (1984). Kamberaas (Oost-Soembaas)-Nederlands woordenboek: Met Nederlands-Kamberaas register. Foris.

- Osmond, M., & Ross, M. (1998). Household artifacts. In M. Ross, A. Pawley, & M. Osmond (Eds.), The lexicon of Proto-Oceanic. The culture and environment of ancestral Oceanic society: 1 material culture (pp. 67–114). Pacific Linguistics.

- Paris, H. (2012). Sociolinguistic effects of church languages in Morobe province, Papua New Guinea. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 214, 39–66. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2012-0020

- Reid, A. (2018). Crossing the great divide: Australia and eastern Indonesia. In M. Clark, & S. K. May (Eds.), Macassan history and heritage: Journeys, encounters and influences (pp. 41–53). ANU Press.

- Ross, M. (2003a). Talking about space: Terms of location and direction. In M. Ross, A. Pawley, & M. Osmond (Eds.), The lexicon of Proto-Oceanic. The culture and environment of ancestral Oceanic society: 2 The physical environment (pp. 229–294). Pacific Linguistics.

- Ross, M. (2003b). Meteorological phenomena. In M. Ross, A. Pawley, & M. Osmond (Eds.), The lexicon of Proto-Oceanic. The culture and environment of ancestral Oceanic society: 2 The physical environment (pp. 119–154). Pacific Linguistics.

- Si, A. (2019). Flora–fauna loanwords in Arnhem Land and beyond – An ethnobiological approach. Australian Journal of Linguistics, 39(2), 202–256. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07268602.2019.1566888

- Skelly, R. J., & David, B. (2017). Hiri: Archaeology of long-distance maritime trade along the South coast of Papua New Guinea. University of Hawai'i Press.

- Stacey, N. (2007). Boats to burn. Bajo fishing activity in the Australian fishing zone. ANU Press.

- Stevens, A. M., & Schmidgall-Tellings, A. E. (2010). Comprehensive Indonesian–English dictionary. Ohio University Press.

- Stokhof, W. A. L., & Almanar, A. E. (1984). Holle lists: Vocabularies in languages of Indonesia Vol.7/3: Central Sulawesi, South-west Sulawesi. Pacific Linguistics.

- Stokhof, W. A. L., & Almanar, A. E. (1985). Holle lists: Vocabularies in languages of Indonesia Vol.7/4: South-east Sulawesi and neighbouring islands, Westan North-east Sulawesi. Pacific Linguistics.

- Swadling, P. (1996). Plumes from paradise: Trade cycles in outer Southeast Asia and their impact on New Guinea and nearby islands until 1920. Papua New Guinea National Museum.

- Usher, T., & Schapper, A. (2018). The lexicons of the Papuan languages of Onin and their influences. NUSA: Linguistic Studies of Languages in and around Indonesia, 64, 39–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.15026/92290

- van den Berg, R., & Sidu Marafad, L. O. (2016). Muna–Indonesian–English dictionary. Summer Institute of Linguistics. https://www.webonary.org/muna/.

- van Vuuren, L. (1917a). De prauwvaart van Celebes. [Part 1]. Koloniale Studien, 1(1), 107–116.

- van Vuuren, L. (1917b). De prauwvaart van Celebes. [Part 2]. Koloniale Studien, 1(2), 229–339.

- Velthoen, E. (2002). Contested coastlines: Diasporas, trade and colonial expansion in eastern Sulawesi 1680–1905 [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Murdoch University.

- Verheijen, J. A. J. (1984). Plant names in Austronesian linguistics. Badan Penyelenggara Seri NUSA, Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya.

- Verheijen, J. A. J. (1986). The Sama-Bajau language in the Lesser Sunda Islands. Pacific Linguistics.

- Villiers, J. (1981). Trade and society in the Banda Islands in the sixteenth century. Modern Asian Studies, 15(4), 723–750. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X0000874X

- Visser, E. (2020). Kalamang dictionary. Dictionaria, 13, 1–2737. doi: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5526419.

- Walker, A., & Zorc, D. (1981). Austronesian loanwords in Yolngu-Matha of northeast Arnhem Land. Aboriginal History, 5, 109–134.

- Waters, B. E. (1983). An interim Djinang dictionary. Summer Institute of Linguistics.

- Zobel, E. (no date). Evidence for a Kaili-Wolio branch of the Celebic languages. Unpublished manuscript.

- Zorc, D. (1986). Yolngu–Matha dictionary. School of Australian Linguistics.