ABSTRACT

This study examined the impact of psychosocial environment and academic emotions on higher education students’ intentions to leave their studies. The data were derived from a survey among students at study programmes for teacher education, early childhood education, and social science education at one higher education institution in Norway (n = 206). The survey comprised items from the Academic Emotions scale (AEC), the Learning Climate Questionnaire (LCQ) and pre-validated scales for Loneliness and Intentions to Leave. In addition, the survey tested out a series of items based on the Emotional Support domain in the Teaching Through Interactions framework (TTI). The study adds to existing research by operationalizing emotional support in higher education learning environments. The findings showed that test emotions and learning-related emotions, perceived loneliness and instructional engagement were significant to explain variance in students’ intentions to discontinue their studies. ANOVA identified significant between-group differences. Older students (>30 years) reported more positive academic emotions and better relations to their teacher than what younger students did, and female students perceived higher levels of instructional engagement than what male students did. Still, the quality of teacher–student relations had no significant impact on students’ intentions to leave.

Introduction

There is a lack of systematic knowledge about indicators of study success in European higher education, and the reasons for completion, delay or withdrawal include multiple factors such as ‘institutional structures, teaching and learning approaches, curriculum design and student background characteristics and the interrelations between all of these’ (European Commission, Citation2015, p. 11). According to Tinto (Citation1993), dropout includes institutional departure, in which students transfer to other studies or institutions, and system departure, in which students leave higher education altogether. The present study measures intended and not actual dropout and assesses students’ thoughts about quitting their present study course. Among the multiple reasons for student dropout in higher education, previous research has revealed a strong relationship between positive psychosocial environments, students’ academic satisfaction, and study completion (Grøtan et al., Citation2019; Lipson & Eisenberg, Citation2018; Truta et al., Citation2018). A report from the Norwegian government also concludes that sense of belonging and quality of psychosocial learning environments are key factors for study progress, and intended and/or actual dropout in higher education (Foss, Citation2014). The psychosocial environment comprises two main dimensions: (1) factors related to individual school failure and perceived academic stress, and (2) factors related to teacher–student and student–student relationships and the social climate of the educational setting (Gustafsson et al., Citation2010). Although teacher–student relationships have been identified as a significant predictor for academic achievement and student engagement in K-12 schools (Hamre & Pianta, Citation2005; Montalvo et al., Citation2007; Quin, Citation2017; Ruzek et al., Citation2016), the impact of such relationships is less frequently and systematically explored in higher education, and often lack a clear theoretical and conceptual framework (Hagenauer & Volet, Citation2014).

A proposed conceptual framework for psychosocial environments in higher education

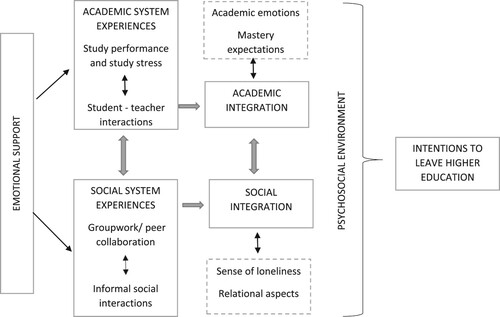

Departing from the key dimensions of psychosocial environments, (1) factors related to academic stress and mastery, and (2) factors related to relational and social aspects of the educational setting (Gustafsson et al., Citation2010), our study integrates three main theoretical perspectives. These are: (1) the Teaching Through Interactions (TTI) framework (Hamre et al., Citation2013), (2) theories on academic emotions (Pekrun et al., Citation2010), and (3) Tinto’s conceptual model of dropout (Tinto, Citation1993). The conceptual framework is illustrated in .

Emotional support is an integrative component in the framework, and relevant for student engagement, social inclusion, efficacy beliefs, and learning-related emotions. Seeking emotional support is therefore an important coping strategy for students (Devonport & Lane, Citation2006). Student coping is defined as the ‘capacity to deal with negative emotions, setbacks, and obstacles’ (Sullivan, Citation2009, p. 114), and is related to the concept of self-efficacy. This refers to students’ beliefs in their ability to attain specific performance outcomes, and for which previous mastery experiences, support and encouragement from others, and interpretations of one’s own emotional reactions are vital (Bandura, Citation1997).

Emotional support in Teaching Through Interactions

The theoretical framework of Teaching Through Interactions (TTI) identifies dimensions of teacher support in the psychosocial environment (Hafen et al., Citation2015; Hamre et al., Citation2013; Pianta et al., Citation2012) and encompasses three broad domains of teacher–student interaction: emotional support, classroom organization, and instructional support. Our study focuses primarily on the emotional support domain, including three subdimensions: (1) positive climate, reflected in the connection between teachers and students and the overall communication tone, (2) teacher sensitivity, indicated by teachers’ responsiveness to and awareness of students’ various emotional and academic needs, and (3) regard for student perspectives, characterized by teachers’ ability to facilitate student-driven teaching, highlight the usefulness and relevance of the study content and to focus on students’ interests and points of view (Hamre et al., Citation2013, p. 465). These dimensions correspond to dimensions in the College and University Classroom Environment Inventory (CUCEI), applied to assess students’ perceptions of the psychosocial dimensions of classroom environment in small higher education classes or seminars (Fraser & Treagust, Citation1986).

Academic emotions in higher education

The role of academic emotions in higher education is an under-researched area (Rowe et al., Citation2015; Sharp et al., Citation2016), and represent a wide range of emotions such as enjoyment, interest, hope, pride, anger, anxiety, frustration, and boredom, and include affective, cognitive, physiological, motivational, and expressive components. Our study focuses specifically on test emotions and learning-related emotions, in which test emotions include emotions such as anxiety, satisfaction and relief related to exams or other assessment situations, whereas learning-related emotions comprise students’ enjoyment of acquiring new knowledge and their interest in the course material (Pekrun et al., Citation2010; Schutz & Pekrun, Citation2007). Many studies have investigated the link between academic emotions, student engagement and potential study success. For example, Kahu et al. (Citation2015) explored the antecedents of academic emotions in higher education and how these emotions were related to student engagement and withdrawal. In Norway, Nedregård and Abrahamsen (Citation2018) found that students’ engagement through an initial interest in the subject was a strong and significant predictor for dropout from profession study programmes. However, few studies have investigated age- or gender-related differences in academic emotions and linked it to dropout intentions in higher education, and by doing so, the present study adds to the current research base. A Norwegian study among higher education students, found that the risk for non-completion increases with age and that there are more non-continuing students among males (Hovdhaugen, Citation2019). Also, a study of engagement and resilience factors among first year university students, found significant gender differences in that female students’ performance was more influenced by their ability not to be frustrated when facing adversities (Ayala & Manzano, Citation2018). Yet another study reported that male students seem less satisfied about their study course, feel less connected to the study institution and report poorer quality of interaction with teachers and fellow students (Severiens & ten Dam, Citation2010).

Tinto’s conceptual model of dropout

Tinto’s (Citation1993) conceptual model of dropout from college is longitudinal and shows how pre-entry attributes, such as pervious education and skills, affect students’ goals and commitments, which in turn, have impact on students’ formal and informal institutional experiences. Examples of such may be emotional and academic support from fellow students and teachers, situated in classroom or groupwork settings. These settings relate to the students’ experiences of academic and social integration, and the sum of all these add up to a potential dropout decision. The model is widely applied in research on student attrition but pays little attention to the explicit role of emotional support in teacher–student relationships and how social inclusion may be facilitated through classroom interaction. Still the model recognizes the mutual relationship between social and academic integration.

The role of social inclusion

Social inclusion is a key predictor for study completion (Hovdhaugen, Citation2019) and teachers and fellow students play an important supportive role when students struggle with social or academic integration or experience doubts about continuing their studies (Wilcox et al., Citation2005). Lane et al. (Citation2019) identify connectedness as a substantial component in a supportive network for higher education students, in which the sense of being accepted and supported by peers and teaching staff is important to enhance academic capabilities. Also, Ajjawi et al. (Citation2020), identify perceived lack of support from the teaching staff as heavy features in students’ explanations of academic failure. Similar conclusions are drawn in a systematic review on the impact of teacher–student relationships in higher education, in which feelings of belonging and emotional support are vital for enhancing academic mastery and preventing dropout (Hagenauer & Volet, Citation2014). Becoming a student often represents major changes in living arrangements and academic situation, new social roles, and a potential loss of social networks. These factors are all significantly related to stress symptoms among higher education students (O’Neil & Mingie, Citation1988; Robotham & Julian, Citation2006; Schulenberg et al., Citation2004). In Norwegian higher education, loneliness is identified as a major problem, in which almost one out of five students feels socially isolated, not included by fellow students, and friendless at school (Knapstad et al., Citation2018). However, whereas social isolation often includes the loss or reduction of social networks, loneliness refers mainly to low levels of emotional support (Wang et al., Citation2017). Perceived emotional support from teachers and fellow students is therefore important in promoting student coping and in reducing stress and loneliness among students.

Aims and research questions

Against this background, our study aims to explore the impact of psychosocial environment and academic emotions on students’ dropout intentions. The study also sets out to determine whether there are significant between-group differences in students’ perceptions of their psychosocial learning environment and their motivation to complete their studies. Based on this, the article identifies two main research questions:

What is the impact of perceived psychosocial environment and academic emotions on higher education students’ intentions to drop out?

Are there any between-group differences based on age and gender, in students’ perceived psychosocial environment, academic emotions, and their intentions to drop out?

Methods and measures

Sample characteristics and research design

The presented study is defined as a quantitative cross-sectional design with survey research (Cohen et al., Citation2018). The target population of the study comprises students in Norwegian higher education. However, the survey sample is drawn from a selection of courses within programmes of professional study for school teachers, early childhood education teachers, and social workers at one higher education institution in Norway. This is a purposive availability sample; the higher education institution was selected in a deliberate, non-randomized manner (Shadish et al., Citation2002) based on the researcher’s affiliation and access to the field. Moreover, the design involved strategic sampling where classes were selected to provide a broad representation of the institution’s programmes of professional studies. The study, which was conducted over several weeks in May 2019, used a digital survey accessed through a QR code scanned on the students’ mobile devices. A researcher supervised and was physically present in all classes during the data collection process.

In total, 33 men and 173 women completed the survey (n = 206), giving a response rate of 91%. An overview of the survey sample is given in .

Table 1. Overview of survey sample (n = 206).

With a total of nine predictors included in the regression analysis, the sample size is satisfying. However, a small sample size reduces the statistical power (Field, Citation2013).

Survey instrument and analysis

The survey data were analysed through correlation analysis, T-tests, and multiple regression analysis. The survey comprised a self-constructed 70-item instrument. Thirty items were drawn from four pre-validated scales, all selected to cover the main research questions of the study. These were: (1) the Intention to Leave scale (2) the Loneliness scale, both drawn from Frostad et al. (Citation2015), (3) the Learning-Related Emotions subscale and (4) the Test-Related Emotions subscale, both drawn from the Academic Emotion Scale of Pekrun et al. (Citation2011). To suit the context of higher education, the term ‘school’ was replaced with ‘study’ for some items. In addition, one new item was added to the Intention to Leave scale. This item is marked with **. The scales are presented in .

Table 2. Scale overview.

The other 40 items in the survey were mainly based on the emotional support domain in the Teaching Through Interactions framework (TTI) (Hamre et al., Citation2013), covering dimensions such as teacher sensitivity, positive learning climate and regard for student perspectives. Since the TTI framework traditionally has been used as a fundament for systematic observation, it was interesting to test the reliability of the scales with survey items inspired by the framework. Psychosocial environment is a very broad concept which is difficult to operationalize. According to Shadish et al. (Citation2002), inadequate explication, either by too broad or too narrow definitions of constructs, represents a major threat to construct validity in quantitative research. Thus, to identify the multidimensionality of constructs, factor analysis may be useful.

In addition to items inspired by TTI, five items were adopted from the Learning Climate Questionnaire (LCQ) (Williams & Deci, Citation1996). These items are marked with an asterisk (*). To identify the underlying factor structure, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed with Kaiser normalization and Varimax rotation. When scale development is based on theoretical assumptions, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) may be the best analytical approach (DeVellis, Citation2012). However, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) is more suitable to identify the potential multidimensionality of pre-defined constructs.

The Kaiser-Meyer Olkin value (KMO) was .89 and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity reached statistical significance (p < .001). The PCA identified eight factors with an eigenvalue >1. Factor loadings <.300 and factors with equal double loading were excluded. These were: ‘I experience a positive teaching atmosphere with laughter and humour’ and ‘I am being listened to if I need extra time to finish assignments’. Three factors had only two items and were not included in the final solution. These two factors comprised the following items: (a) ‘I experience that I am being listened to when speaking in class’, ‘I get negative comments from fellow students’ (Eigenvalue = 1.42), and (b) ‘I want to be given more responsibility for my own learning process’, ‘I have influence on how the teaching is arranged’ (Eigenvalue 1.26). The final factor comprised only one item: ‘I wish there was more time for individual conversations with the teacher’ (Eigenvalue 1.18). In sum, the PCA resulted in a five-component solution, explaining 52.6% of the total variance. The final solution is presented in .

Table 3. Principal component analysis with factor loadings (varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization) (n = 206).

The five factors were computed as scale variables and named (1) Teacher–Student Relation, (2) Sense of Student Community (3) Instructional Quality, (4) Groupwork Satisfaction and (5) Confidence in Student Role. All items were measured on a 4-point Likert Scale: 1 = totally disagree, 2 = somewhat disagree, 3 = somewhat agree, and 4 = totally agree. When calculating scale reliability, coding of the negatively loaded items was reversed. All scales reached a satisfying level of reliability, with a score of α >.700 (DeVellis, Citation2012). However, validity is not a property of scale designs, but an argumentative question based on the match between empirical data and existing theory (Shadish et al., Citation2002). In our case, the emotional support domain of TTI matches many of the essential components of psychosocial environments in higher education settings as defined by Tinto (Citation1993) and Fraser and Treagust (Citation1986).

Ethics

The survey was conducted in line with the Norwegian Guidelines for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences, Humanities, Law and Theology (2016), and approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD). Efforts were made to ensure protection of privacy and informed consent for all participants. All students were given written and oral information to ensure their informed consent, and their right to deny or withdraw from participation at any time during the survey was highlighted. However, due the use of QR-code to ensure anonymous access to the survey, it was not possible for students to withdraw their consent after completing the questionnaire. To minimize the risk of indirect identification of respondents due to combination of information such as age and gender, the study course was not included as a background variable.

Results

The relationship between the scale variables was initially explored through bivariate correlations, the findings of which are presented in .

Table 4. Correlations (Pearson’s r) between the survey scales.

The bivariate correlations measured through Pearson’s r identified a strong and positive correlation between Teacher–Student Relation and Instructional Quality (r = .634). Furthermore, there was a strong and significant negative correlation between Sense of Student Community and Loneliness (r = –.538), indicating that students who report high scores on loneliness also report low scores in sense of student community. Finally, test emotions and learning-related emotions seemed highly and positively correlated (r = .582). The negative loaded items in these scales were reversed before computing the scale variables; thus, high scores are interpreted as positive emotions.

Psychosocial factors contributing to explain variance in students’ dropout intentions

To explain variance in students’ dropout intentions, a multiple regression analysis was performed, with the scale ‘Intention to leave’ as the dependent variable. The results are presented in .

Table 5. Multiple regression analysis with intention to leave as dependent (constant).

Due to the rather small sample size, the adjusted R-square value of .304 is reported, indicating that the factors included in the model explain 30.4% of the variance in students’ intention to leave. Loneliness, test emotions, learning-related emotions, and instructional quality each made a unique and significant contribution in explaining the variance in intention to leave. Among these, learning-related emotions made the strongest contribution, indicating that the students’ sense of enjoyment of learning and acquiring new knowledge, their optimism about being students, and their interest (or lack of interest) in the course material, are most relevant for their intention to leave. Based on the partial correlation coefficient, this variable explains 5.4% of the total variance. However, the students’ test emotions, their sense of loneliness in the study situation, and their perceived instructional quality also contributed significantly in explaining their intention to drop out.

Age- and gender-based differences in perceived psychosocial environment, academic emotions, and dropout intentions

To explore potential group differences between the students based on gender and age, a series of T-tests was performed, with all nine scales presented in and as dependent variables and gender and age as independent variables. Significant differences between male students (M = 24.67, SD = 3.79) and female students (M = 22.78, SD = 4.50; t(184) = 2.15, p = .03) were identified on the scores for the Test emotions scale, indicating that male students perceive fewer negative emotions related to test situations than do female students. On this scale, there were also age differences, where the younger students (M = 22.63, SD = 4.22) reported significantly lower scores than did the older students (M = 24.65, SD = 4.98; t(182) = −2.54, p= .012). This indicates that older students experience more positive test emotions, are more pleased with their test performance, and are comfortable in the test situation. The T-tests also identified that students over the age of 30 reported significantly higher scores on the Learning-related emotions scale (M = 24.97, SD = 4.39) than did younger students (M = 23.08, SD = 3.79; t(185) = –.2.70, p = .008). High scores indicate more positive feelings towards the learning process itself and challenges related to the study situation. However, the effect sizes were small (eta squared > .03), and there is a risk of a Type 1 error.

On the Instructional Quality scale, male students reported significantly lower scores (M = 12.81, SD = 2.52) than did female students (M = 13.98, SD = 2.95; t(188) = −2.068, p = .040). This indicates that female students more often feel that the teacher adjusts the teaching tempo, has a flexible way of organizing the teaching, makes the study practically relevant, and highlights the usefulness of the material being studied. Finally, the T-tests identified significant between-group differences on the Teacher–Student Relation scale, showing that students under the age of 30 reported much lower scores (M = 38.50, SD = 9.03) than did older students (M = 42.74, SD = 7.87, t(178)= −2.67, p = .008). Based on the items comprising this scale, it seems that older students more often feel that the teacher is interested in getting to know them, understands their needs for support, and is able to motivate them and communicate positive mastery expectations. There were no significant between-group differences related to age or gender for the other scales.

Summary of findings

Learning-related emotions made the strongest contribution to explain the variance in higher education students’ intention to leave the study. Loneliness, test emotions, and instructional quality also made a smaller, though still significant contribution. Significant age differences were identified in learning-related emotions, indicating that older students experience more joy in acquiring new knowledge, are prouder and more optimistic about being students, and feel fewer negative emotions in the learning situation. The older students also experienced more positive relations to their teacher, feeling more supported and understood than did the younger students. In addition, female students more often reported high scores for instructional quality, in terms of the teachers adjusting their tempo and conveying the relevance and usefulness of the material being studied.

Discussion

This article’s main research questions address the impact of students’ psychosocial environment and their academic emotions on their intentions to leave or discontinue their studies and explore whether there are differences in student perceptions based on age and gender. The conceptual framework presented in informs the discussion by identifying emotional support as relevant for academic and social integration, which in turn, help explain students’ intentions to leave their studies.

The role of academic emotions in dropout

The findings show that test emotions – which include feelings such as pride, fear, joy, panic, and relief related to prior test situations, as well as the students’ mastery expectations for future exams – made a significant and unique contribution in explaining students’ intentions to leave the study. Here, male students and older students reported more positive results. In Norway, over 40% of higher education students suffer from test anxiety (Knapstad et al., Citation2018). According to Bandura (Citation1997) previous and vicarious mastery experiences, psychological states and social persuasion are the main sources to academic self-efficacy. In this perspective, social and academic support from teachers and fellow students are vital, conveying positive mastery expectations and providing help to deal with negative test emotions. According to Wilcox et al. (Citation2005), perceiving the teacher as approachable and supportive strengthened students’ academic confidence. It was also important that the teacher was thoughtful and understanding regarding how stressful personal situations may affect the students’ academic work. This dimension was accounted for by the item, ‘The teacher understands how my study life is affected by my private life’ on the Teacher–Student Relation scale.

Furthermore, older students reported significantly more positive outcomes concerning learning-related emotions, indicating that, to a greater degree, these students seem to enjoy the learning process and are motivated by the acquisition of new knowledge. Combined with their positive scores on test emotions, it seems that older students are more comfortable and motivated in their study situation and, as a result, cope better academically. Learning-related emotions, while identified as significant in explaining the variance in intentions to leave the studies, were not significantly correlated with instructional quality. This suggests that students’ emotions in the learning situation emerge almost independently of the teachers’ ability to adjust the teaching tempo, to demonstrate the relevance and usefulness of the material, and to allow the students freedom and autonomy in planning their learning process. Hence, individual values and attribution patterns, and self-efficacy beliefs may be more relevant in explaining learning-related emotions (Schutz & Pekrun, Citation2007).

Relational aspects and sense of support

As for the student–teacher relationship, older students reported higher scores on the Teacher–Student Relation scale, a scale that encompasses dimensions such as the degree to which students feel seen, understood, supported, and motivated by the teacher. Still, in our study, the quality of students’ relations with their teachers made no significant contribution in explaining students’ intentions to leave the study. Nonetheless, the Teacher–Student Relation scale was strongly and positively correlated with the Instructional Quality scale (r = .634), indicating that a positive relationship with one’s teacher is connected to high scores on the students’ perceptions of the teachers’ ability to convey the relevance and usefulness of the study course material, support student autonomy and organize the teaching in a flexible manner. Here it is hard to assess what comes first, the positive relationship or the perceived instructional quality. Although several studies from the K-12 context support a link between the quality of the teacher–student relationship and students’ emotional, cognitive, and academic engagement and outcomes (Montalvo et al., Citation2007; Quin, Citation2017), similar research on teacher–student relationships in higher education is sparser (Hagenauer & Volet, Citation2014). However, several studies found that students’ academic satisfaction measured, i.e., through perceived quality of teaching and supportive relationships with teachers and peers, have a significant impact on students’ academic mastery and intentions to drop out from higher education (Ajjawi et al., Citation2020; Lane et al., Citation2019; Truta et al., Citation2018; Wilcox et al., Citation2005).

Loneliness and the impact of integration and social inclusion

Finally, the results in our study show that loneliness makes a unique, significant contribution in predicting students’ intention to quit. This is well supported by international studies on the relationship between loneliness and dropout risks in higher education (Grøtan et al., Citation2019; Lipson & Eisenberg, Citation2018). While our study revealed no age- or gender-based differences in perceived loneliness, there was a strong, significant negative correlation between the Loneliness scale and the Sense of Student Community scale, indicating that being treated with respect, invited into the class community, and being the subject of fellow students’ interest significantly affect the perceived loneliness of higher education students. According to Wang et al. (Citation2017), loneliness is strongly related to a lack of emotional support. In our study, emotional support was conceptualized through the Teaching Through Interactions framework (Hafen et al., Citation2015; Hamre et al., Citation2013), emphasizing the impact of being treated respectfully, shown interest, encouraged to ask questions, met with positive expectations, and feeling seen, included, and understood. Becoming a student often signifies the loss of established social networks and new academic demands, reinforcing one’s sense of loneliness if emotional support is perceived as low. Clearly, loneliness is a widespread problem among students both in Norway (Knapstad et al., Citation2018) and abroad (Oakley, Citation2020). Given that loneliness itself predicts student attrition, efforts to improve social inclusion and emotional support in the psychosocial environment are important in preventing dropout in higher education.

Limitations

This study has four main limitations. First, the sample, the size of which is small, is drawn from only one higher education institution. This may reduce the generalizability and representativeness of the study. Still, the sample includes students from several education programmes, and thus represents a broad selection of students’ academic interests. Second, the unequal sample size of male and female students may elevate the risk of Type 1 errors. However, Levene’s test for equality of variances indicated equal variances between the groups. Moreover, the gender balance in the sample is representative for the study courses included. Third, the mental health status of the students is not included as a measured variable, though this likely mediates the relationship between loneliness, academic emotions, and intention to leave higher education studies. Finally, the TTI-framework was originally developed for indicators in systematic observation and the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS), and not to inform survey item construction. However, the high reliability of the scales, derived from factor analysis, indicates that the framework may also be relevant for survey research.

Conclusion

Existing research on dropout in higher education identifies positive psychosocial environments as a significant predictor for study completion. The present study utilized the Teaching Through Interactions framework (TTI) to identify key components in emotional support as part of the psychosocial environment and combined these with measures of loneliness and academic emotions. The study identified significant age- and gender-based differences in student perceptions, but further research is required to explore students’ various needs for support. The low male representativeness in the study reflects the problem of recruiting male students to professional programmes for school teachers, early childhood education teachers, and social workers. Hence, male dropout from these programmes is important to prevent.

Acknowledgements

The author wants to thank the project partners Professor Ingrid Lund, Associate Professor Kjersti Balle Tharaldsen, Professor Lars Edvin Bru and Associate Professor Jan Arvid Haugan for valuable comments to the survey construction. Also, many thanks to the University College Network for Western Norway for financing grants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ajjawi, R., Dracup, M., Zacharias, N., Bennett, S., & Boud, D. (2020). Persisting students’ explanations of and emotional responses to academic failure. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(2), 185–199. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1664999

- Ayala, J. C., & Manzano, G. (2018). Academic performance of first-year university students: The influence of resilience and engagement. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(7), 1321–1335. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1502258

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

- Cohen, L., Morrison, K., & Manion, L. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge.

- DeVellis, R. F. (2012). Scale development: Theory and applications. Sage.

- Devonport, T. J., & Lane, A. M. (2006). Relationships between self-efficacy, coping and student retention. Social Behavior and Personality. An International Journal, 34(2), 127–138. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2006.34.2.127

- European Commission. (2015). Dropout and completion in higher education in Europe. https://supporthere.org/sites/default/files/dropout-completion-he_en.pdf

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (4th ed.). Sage.

- Foss, P. K. (2014). Riksrevisjonens undersøkelse av studiegjennomføringen i høyere utdanning [Office of the Auditor General of Norway’s study of study progression and completion in higher education] Dokument 3:8. www.riksrevisjonen.no

- Fraser, B. J., & Treagust, D. E. (1986). Validity and use of an instrument for assessing classroom psychosocial environment in higher education. Higher Education, 16(1–2), 37–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138091

- Frostad, P., Pijl, S. J., & Mjaavatn, P. E. (2015). Losing all interest in school: Social participation as a predictor of the intention to leave upper secondary school early. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 59(1), 110–122. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2014.904420

- Grøtan, K., Sund, E. R., & Bjerkeset, O. (2019). Mental health, academic self-efficacy and study progress among college students – the SHoT study, Norway. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(45). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00045

- Gustafsson, J.-E., Allodi, M. W., Åkerman, B. A., Eriksson, C., Eriksson, L., Fischbein, S., Granlund, M., Gustafsson, P., Ljungdahl, S., Ogden, T., & Persson, R. S. (2010). School, learning and mental health. A systematic review. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. https://www.kva.se/globalassets/vetenskap_samhallet/halsa/utskottet/kunskapsoversikt2_halsa_eng_2010.pdf

- Hafen, C. A., Hamre, B. K., Allen, J. P., Bell, C. A., Gitomer, D. H., Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B., & Cappella, E. (2015). Teaching through interactions in secondary school classrooms: Revisiting the factor structure and practical application of the classroom assessment scoring system–secondary. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 35(5–6), 651–680. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431614537117

- Hagenauer, G., & Volet, S. E. (2014). Teacher-student relationship at university: An important yet under-researched field. Oxford Review of Education, 40(3), 370. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2014.921613

- Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2005). Can instructional and emotional support in the first-grade classroom make a difference for children at risk of school failure? Child Development, 76(5), 949–967. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00889.x

- Hamre, B., Pianta, R. C., Downer, J. T., DeCoster, J., Mashburn, A. J., Jones, S., Brown, J. L., Cappella, E., Atkins, M., Rivers, S. E., Brackett, M. A., & Hamigami, A. (2013). Teaching through interactions: Testing a developmental framework of teacher effectiveness in over 4000 classrooms. The Elementary School Journal, 113(4), 461–487. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/669616. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10. 1086/669616

- Hovdhaugen, E. (2019). Causes of dropout in higher education: A research summary of studies based on Norwegian data. NIFU Labour Note 2019:3. http://hdl.handle.net/11250/2593810

- Kahu, E., Stephens, C., Leach, L., & Zepke, N. (2015). Linking academic emotions and student engagement: Mature-aged distance students’ transition to university. Journal of Further & Higher Education, 39(4), 481–497. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2014.895305

- Knapstad, M., Heradstveit, O., & Sivertsen, B. (2018). Studentenes Helse- og Trivselsundersøkelse 2018 (SHoT) [Students’ health and wellbeing study 2018]. https://www.studenthelse.no

- Lane, M., Moore, A., Hooper, L., Menzies, V., Cooper, B., Shaw, N., & Rueckert, C. (2019). Dimensions of student success: A framework for defining and evaluating support for learning in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(5), 954–968. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1615418

- Lipson, S. K., & Eisenberg, D. (2018). Mental health and academic attitudes and expectations in university populations: Results from the healthy minds study. Journal of Mental Health, 27(3), 205–213. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1417567

- Montalvo, G. P., Mansfield, E. A., & Miller, R. B. (2007). Liking or disliking the teacher: Student motivation, engagement and achievement. Evaluation & Research in Education, 20(3), 144–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2167/eri406.0

- Nedregård, O., & Abrahamsen, B. (2018). Frafall fra profesjonsutdanningene ved OsloMet [Dropout from the profession studies at Oslo Metropolitan University] Rapport nr. 8. https://skriftserien.hioa.no/index.php/skriftserien/article/view/121/114

- Oakley, L. (2020). Exploring student loneliness in higher education. A discursive psychology approach (1st ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-35675-0

- O’Neil, M. K., & Mingie, P. (1988). Life stress and depression in university students: Clinical illustrations of recent research. Journal of American College Health, 36(4), 235–240. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.1988.9939019

- Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., Barchfeld, P., & Perry, R. P. (2011). Measuring emotions in students’ learning and performance: The achievement emotions questionnaire (AEQ). Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(1), 36–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.10.002

- Pekrun, R., Stephens, E. J., & Smart, J. C. (2010). Achievement emotions in higher education. In J. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research: Volume 25 (pp. 257–306). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-8598-6

- Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B., & Allen, J. P. (2012). Teacher-student relationships and engagement: Conceptualizing, measuring, and improving the capacity of classroom interactions. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 365–386). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_17

- Quin, D. (2017). Longitudinal and contextual associations between teacher–student relationships and student engagement: A systematic review. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), 345–387. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316669434

- Robotham, D., & Julian, C. (2006). Stress and the higher education student: A critical review of the literature. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 30(2), 107–117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03098770600617513

- Rowe, A. D., Fitness, J., & Wood, L. N. (2015). University student and lecturer perceptions of positive emotions in learning. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 28(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.847506

- Ruzek, E., Hafen, A., Allen, C. A., Gregory, J. P., Mikami, A., Pianta, A. Y., & C, R. (2016). How teacher emotional support motivates students: The mediating roles of perceived peer relatedness, autonomy support, and competence. Learning and Instruction, 42, 95–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.01.004

- Schulenberg, J. E., Sameroff, A. J., & Cicchetti, D. (2004). The transition to adulthood as a critical juncture in the course of psychopathology and mental health. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 799–806. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579404040015

- Schutz, P. A., & Pekrun, R. (2007). Emotion in education. Elsevier Science & Technology. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

- Severiens, S., & ten Dam, G. (2012). Leaving college: A gender comparison in male and female-dominated programs. Research in Higher Education, 53(4), 453–470. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-011-9237-0

- Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin.

- Sharp, J. G., Hemmings, B., & Kay, R. (2016). Towards a model for the assessment of student boredom and boredom proneness in the UK higher education context. Journal of Further & Higher Education, 40(5), 649–681. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2014.1000282

- Sullivan, J. R. (2009). Preliminary psychometric data for the academic coping strategies scale. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 35(2), 114–127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1534508408327609

- Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition (2nd ed.). The University of Chicago Press.

- Truta, C., Parv, L., & Topala, I. (2018). Academic engagement and intention to drop out: Levers for sustainability in higher education. Sustainability, 10(12), 4637. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124637

- Wang, J., Lloyd-Evans, B., Giacco, D., Forsyth, R., Nebo, C., Mann, F., & Johnson, S. (2017). Social isolation in mental health: A conceptual and methodological review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(12), 1451–1461. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1446-1

- Wilcox, P., Winn, S., & Fyvie-Gauld, M. (2005). ‘It was nothing to do with the university, it was just the people’: The role of social support in the first-year experience of higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 30(6), 707–722. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070500340036

- Williams, G. C., & Deci, E. L. (1996). Internalization of biopsychosocial values by medical students: a test of self determination theory. Journal of personality and social psychology, 70(4), 767–779. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.70.4.767