ABSTRACT

Academic developers enter the field of academic development (AD) from various disciplines and at different stages of their careers. They bring with them their academic experiences, home disciplinary culture and presumptions about what AD is. These circumstances inform the initial professional identity for those working in what has been described as a fragmented community. Identity impacts on an individual’s prioritisation or commitment to a particular role, which in turn impacts on work outcomes. These relationships are presently poorly understood, and so we sought to find out what factors were most influential on how AD was practiced. Nineteen developers in New Zealand and Japan were interviewed about their experiences and we found that in both countries, the often-overlooked workplace factors of role, employment, and structure were important determinants that shaped identity regardless of variations on entry to the profession. Roles we observed could be more-or-less academic or service; employment types could be permanent or temporary; and workplace structure related to the AD unit as centrally positioned in the university or embedded in one of the disciplines of higher education. These factors have received very little attention in AD identity work but are clearly important determinants of how AD is constructed and practiced. We suggest that structural fragmentation has been a stable factor over decades and unlikely to change for the foreseeable future. As such, the field is currently far away from professionalisation (with common entry requirements, practices, and standards) or shared epistemologies including where its knowledge comes from.

Introduction

With the inherent nature of ambiguity in the academic development (AD) field, it is no wonder that since the mid-1990s, identity has become one of the major research topics in this area (Laksov & Huijser, Citation2020). In identity theory, individuals engage in a process of identification involving self-categorisation in relation to others (Brewer & Gardner, Citation1996), and Bauman (Citation1996, p. 19) suggested that ‘one thinks of identity whenever one is not sure where one belongs’. This field of research is important because the prominence of a particular identity impacts on an individual’s prioritisation or commitment to a particular role (Broscheid, Citation2019), which inevitably influences the quality of one’s AD work outcomes (Cruess et al., Citation2014). Much of the literature on AD identity has focused on other factors, such as migration into the field or a sense of liminality (Mori et al., Citation2022). However, we argue that these factors alone are insufficient to capture the complexity inherent to how AD work is done across the world. In this paper, we identify and examine the work settings of academic developers and theorise them as factors that influence identity formation and growth.

The feelings of uncertainty among practitioners that prompted this sustained interest in identity have also been discussed in relation to academic identity more broadly. According to Henkel (Citation2005), identity formation is best understood as a construct that takes shape and evolves in the context of an individual’s relationships with others within a community, and academic identity is no different. In the past, academics formed and sustained their professional identity in relation to two main communities, one rooted in their discipline and the other in their higher education institution. The neoliberalisation and corporatisation of the university have challenged the stability of these communities, as these processes gave institutions greater power over academics’ working lives, and disciplinary boundaries were challenged and reshaped. As a result, the academic department had lost some of its prominences due to organisational restructuring and greater control over academics’ work, prompting a sense of distance and even alienation (Henkel, Citation2005, Citation2016). In contrast, and despite disciplinary boundaries being challenged, the significant role of the discipline as a source of identity was largely maintained. This was attributed to the importance of ‘academic autonomy’, referring to the ability of academics to determine the nature of their own work, mostly in relation to research but also to teaching, as a pivotal factor affecting identity (Henkel, Citation2005; Henkel & Vabø, Citation2006).

While insightful, research on academic identity provides a limited theoretical and empirical basis for theorising the formation and growth of those working in AD. This is mostly because AD is yet to be established as a discipline. At present it is lacking the necessary knowledge foundations and mostly relies on ‘craft knowledge’ (Boughey, Citation2022; Shay, Citation2012). In our research project, therefore, we seek to deepen our knowledge of the factors affecting the professional identity of academic developers.

Identity is also an essential concept in the theory of Communities of Practice (CoP) (Wenger, Citation1998) which links a sense of belongingness to the scholarly advancement of a discipline (Daniel, Citation2018), and which has been very influential in AD work. In established disciplines, like medicine, what members prioritise in their work would naturally be similar because members go through the same apprenticeship process, as they move from the periphery to the centre and full membership in the community (Wenger, Citation1998). However, if the CoP is itself relatively weak, then such movement is likely to be a challenge, and this may be the case for the relatively new field of AD. For one thing, it has been claimed that most developers experience ‘a never-ending apprenticeship with no master’ (Fyffe, Citation2018, p. 358) whereas in the medical example, working towards common goals and professional status has been a part of the curriculum for a long time (Sternszus, Citation2016). Cruess et al. (Citation2014, p. 1447) defined the professional identity of a physician as ‘a representation of the self, achieved in stages over time during which the characteristics, values, and norms of the medical profession are internalized, resulting in an individual thinking, acting, and feeling like a physician’. However, the fragmented nature of AD makes the community of developers’ identification process challenging. Since AD has been difficult to professionalise and contains various characteristics, values, and norms, developers have been left as a ‘family of strangers’ (Harland & Staniforth, Citation2008). Being together as well as being strangers creates a challenge since AD is not only complex, dynamic, and fluid (Carew et al., Citation2008; Little et al., Citation2019), but in many cases, developers are left to figure out new ways of being and doing without a guide. This liminal position may increase a sense of marginalisation from the rest of the institution (Fyffe, Citation2018; Manathunga, Citation2007; Popovic & Fisher, Citation2016), which in turn will naturally make it challenging for developers to form a shared AD identity.

There is also a history across the world of AD operations and staff arrangements changing without developers themselves being consulted (Fitzpatrick, Citation2019; Moses, Citation2012; Sword, Citation2022; Weimer, Citation2007). Under such uncertain and tension-filled conditions, it is expected that a stable professional identity would be challenging to cultivate. We take a cue from this phenomenon, and in this paper examine factors that may underlie and contribute to this observed uncertainty. We argue that despite the fragmented nature of AD, it is recognisable in all its complexity, and that it is currently ‘stable’ in this uncertain context. With that, the field is characterised by a diversity of work settings. Diversity also includes different contract types, backgrounds, experience, and qualifications of developers, different institutional positioning of AD departments, academic versus service tensions, the precarious nature of AD work, the undervaluing of AD, constant comparison to established disciplines, a drive for professional recognition, marketing of each unit through difference rather than commonality, and more. All these have become constant determinants of the field, and so shared across higher education institutions. There are benefits and costs in accepting such diversity. For example, Manathunga (Citation2007) suggests that it may create different spaces for exploring ideas about teaching and learning while Rowland (Citation2007) warns that role ambiguity embraces a type of relativism that will allow developers to construct endless identities and even avoid dealing with fundamental questions about the purpose of their work and higher education.

A review of the identity topic showed that much is known about developers’ perceptions of liminality, agency, and community (Mori et al., Citation2022), and in the present study, we seek to extend this work by focusing on the structures of the workplace in which AD units/departments are formed and in which careers are made. Developers tend to lack influence over how they are structured and operate (Harland & Staniforth, Citation2008), and the field today remains fragmented. When developers begin work, they must first figure out their roles and the requirements of the job, including whether it is relatively more service or academic oriented. Of course, they will already know their employment status but may not fully understand the complex structure of a new type of work environment, and this complexity is the focus of the paper.

Study methodology

Our primary source of data collection was semi-structured interviews conducted with 19 current and past developers at two research-intensive universities, one in New Zealand and one in Japan (). In New Zealand, the developers were all academics and permanent staff. There were two distinctive groups. One embedded in the medical school: University of Otago’s medical school Education Development and Staff Support Unit (EDSSU) and the other served the whole institution: Higher Education Development Centre (HEDC). In addition, AD was provided by a range of people outside of these groups and we interviewed one member of an Administrative Unit (anonymised for concealing the participant’s identity) who worked in the development space. In Japan, where the term faculty development (FD) is used, there were three distinct groups. First, the University of Tokyo’s central FD unit: Future Faculty Program (FFP); second, a project-based FD initiative, Global Faculty Development (GFD); and third, developers within individual departments and institutes affiliated to the University. All developers entered the FD role either voluntarily as a part of institutional service or in managerial positions, except those working in the FFP. In addition, both universities had more than one campus, and development activities were thus spread between them. These participants were thought to be a reasonable representation of the diversity of appointments typically found in universities across the world.

Table 1. Academic developers interviewed for this study.

To explore the relationship between types of employment and identity, we presented participants with an adapted version of O’Sullivan and Irby’s (Citation2014) Models of Faculty Developer’s Identity as a visual prompt to help them reflect on the place of AD in their work, and how that might have evolved over time since becoming a developer. The models depict a general relational positioning of AD with respect to being a researcher and a teacher (the two main roles academics have), and were aligned with one of four identity types:

Compartmentalised (when at times one is a researcher and teacher and at other times an academic developer).

Hierarchical (where being either a researcher, a teacher, or a developer is prioritised over the others).

Parallel (when the researcher, teacher, and developer components exist simultaneously, but without overlap).

Merged (when all three components are integrated and coincide simultaneously).

The interviews that followed lasted about one hour and were transcribed verbatim with no identifying information about the participants. In Japan, two out of the ten interviews were conducted in Japanese and later translated into English. The transcripts were analysed by all three researchers thematically in relation to our research aim of examining how the structures of the workplace influence AD work and identity. Where helpful, we interpreted these themes using O’Sullivan and Irby’s (Citation2014) model.

Findings and discussion

The variety of ways AD (or FD in Japan) was organised and practiced in each university makes broad comparisons between countries and roles challenging (). However, this diversity is a key characteristic of AD globally, and therefore it became one of the focal points of the study. In this context, we highlight a key data theme that we have collectively called ‘workplace factors’ and argue that the importance of these factors has largely been overlooked while they are crucial for professional identity formation and growth. We further argue that the fluid identity observed on entry will be influenced by these workplace factors, and that these determine values in action and values supported and denied. In other words, those new to the profession may have a number of ideas about AD, but these will be shaped mainly by the institution, the contract they are employed on, whether or not the institution and its workforce regard them as working in a service position, or if they are also seen as academics providing a service (with differences to other service providers, such as having the right to do research and academic freedom) and where the unit or department is located within the institution. This influence is seemingly at odds with research indicating the declining role of institutions as a source of academic identity (Henkel, Citation2005; Henkel & Vabø, Citation2006), but is primarily because developers may not have an academic position, and those who do may have some roles and responsibilities other academic colleagues do not. In accordance with this literature on academic identity, identity partly forms in relation to others, and we suggest that the closer the department is to the central administration, the more likely developers will feel like or be seen as service providers. Positioning AD in a discipline (e.g., medicine in New Zealand) rather than serving the whole institution also had ramifications, and the study showed that what developers were allowed to do and how they were perceived by those they work with were very important determinants of identity. In other words, academic autonomy matters not only to academic identity (Henkel, Citation2005) but also for AD identity. Three workplace factors influencing this were identified.

Role: between academic and service

Often, developers are oriented towards either service or academic work according to decisions made by university management (Harland & Staniforth, Citation2003). All nine participants in New Zealand entered AD with permanent contracts as developers, and so had fully transferred from their home disciplines. However, one participant had a double-appointment that allowed her to continue teaching papers in her home discipline, and all academics in New Zealand were free to negotiate teaching outside of AD. Most were not fully aware of how AD might function before entering the field, but over time, they all described merged identities where researcher, teacher, and academic developer could exist together. However, it was the relationship between these roles that caused some tensions. Despite having the rare status of an academic department, staff of the HEDC still had challenges in working with the inherent service nature of development work. George expressed this complexity as:

There’s always this sort of uneasy tension between being a service and an academic unit and I think […] HEDC’s a hybrid. […] We have some academic roles, but I sort of envisaged the teaching as the service, sort of (George, NZ).

If we examine the potential for subject expertise to provide the basis of an institutional service, law lecturers do not offer legal advice, clinical lecturers do not consult staff as patients, and finance lecturers do not provide financial advice to the institution. Thus, the line separating teaching from service may be very clear, so when those working as developers in the field of higher education provide their own knowledge to support those they work with, it is a comparatively unusual case. However, notions of research, teaching, and service that are traditionally understood as the three key components of academic work (Gunn et al., Citation2015; Muthama & McKenna, Citation2024) may be too simplistic for describing much of contemporary academic work, and new types of academics are finding a place in the academy (Macfarlane, Citation2011; McCowan, Citation2017).

Among the ten participants in Japan, seven voluntarily entered FD or were appointed to managerial positions that included FD work. The other three migrated to FD as permanent developers from other disciplines. As in the New Zealand case, most participants in Japan did not know much about FD prior to entry. In contrast to New Zealand developers, many participants in Japan perceived their role as service, with some explicitly mentioning FD as ‘administrative service’:

[My FD unit] couldn’t give credited courses. […] and then, [another department within the university] invited me to become a faculty member […]. So, I was teaching courses there as well, in my field, so I did see myself as a teacher. The faculty developer, I think I didn’t see myself so much in that role because I didn’t see the […] interest among the faculty to know more about [FD work]. [My colleagues] said the only thing that’s really important here is the admin. So, I separated myself from that because I didn’t want that. I just wanted to be more of the teacher, researcher (Naomi, Japan).

If these experiences are contrasted with the HEDC, it appears challenging in Japan to build an identity through knowledge and a disciplinary community. HEDC is a full academic department with a large community of postgraduate students, postgraduate degree options and large research programme. With this comes a strong community of practice built on research, knowledge, and a shared language and community (Shay, Citation2012). However, it is different, for example, to the University’s law faculty in that it uses its knowledge to provide a service to its institution, and this way of working was interpreted as a route to forming a merged identity. Yet, although this identity was predicated mainly on traditional academic values of research and teaching, the AD component was still seen as service.

In Japan, having no clear academic pathway or community renders the FD as purely service. Naomi, for example, would not have been able to teach if not for the invitation she received from another department. Her colleagues wanted her to focus on administration whereas she sought the same status as other academics. Many who enter the field with academic experience and aspirations will find the shift to service problematic if the balance is not right. Indeed, Naomi lamented that The University of Tokyo ‘was a traditional university, but it [the FD unit] wasn’t a traditional department, and therefore, they had thrown off the balance […]. I was getting grants. I was an experienced teacher as well […]. It was confusing’ (Naomi, Japan). FD work in the Japan case currently involves establishing a new institute/organisation and research environment, implementing senior-management roles that involve personal and professional development, promoting medium of instruction in languages other than Japanese such as English Medium Instruction (EMI), and improving teaching and learning which is common throughout the world. Even when these come to fruition, they are likely to be perceived as service activities.

If a developer’s job description is close to that of ‘regular’ academics in established fields (Harland & Staniforth, Citation2003), the AD role should be academic, but this is highly unlikely because of the nature of development work and how teaching in general is perceived. If all teaching across an institution was seen as a service, the distinctions between AD and regular academic work would start to break down. However, regular academics are unlikely to regard their teaching as providing a service to students and will not see their work as providing a service to their institution. They may be involved in service activities (e.g., committee work) but teaching and research remain independent of this. As such, we suggest that there will always be a divide between AD and regular academic work. Although developers may attain genuine academic standing with appropriate contracts, in the eyes of their colleagues they will also be service providers. In addition, the subject of higher education is something that all those who work in a university have some knowledge of, even if only through experience. It is therefore devalued because it is not seen as a specialised theoretical field. Such a position is unlikely to be overcome through the promotion of a community of practice model (Wenger, Citation1998) because this community would require every single member of a university to be part of it and would also require AD to be at the centre.

Employment: between permanent and temporary

The type of employment had a major impact on how developers constructed their identity. Our participants had a range of different contract types, and these were broadly classified in various forms of temporary or permanent employment. As employment comes closer to permanent, it is more likely that developers form and grow a new professional identity (Fruisting, Citation2017).

All nine participants in New Zealand had permanent employment as developers with careers spanning from five to over thirty years. When asked to reflect on how their identity had changed since entering the field, eight of the nine indicated a shift. At first AD was compartmentalised or seen as hierarchically lower than the research and teaching aspects of their older regular academic role, and then later these formed a merged identity, where the AD component was well integrated with all the other academic components. The other participant believed AD had already been highly integrated in their professional identity at the start.

In contrast, seven of the ten participants in Japan were temporary developers, having been appointed to positions requiring some FD work (e.g., senior management roles, mentoring junior staff), or had voluntarily entered a FD unit as a contribution to institutional service. Three were permanent developers. Akiko addressed the temporary nature of employment in the Japanese context:

I think it’s very difficult to convince universities in Japan to hire professional developers […], they have no place. […] I think many universities would be willing to hire an outside consultant. Or they will be willing to make some of the faculty members into academic developers by encouraging them to take seminars and maybe […] go abroad and take like a two week-long seminar and get a […] certificate or something like that. […]. To hire […] an academic developer full time, that would be a very difficult thing to do (Akiko, Japan).

Structure: between central and embedded

AD was embedded in a regular academic department (or faculty, school, etc.) or in a central unit that served the whole institution. The more central the configuration was, the more interdisciplinary the work became. In New Zealand we found a central unit, a discipline-based unit and AD work being done outside of these structures. Those working on permanent contracts in either central or discipline-based units had a strong embedded conception of identity. However, those who worked in the discipline-based unit (EDSSU in medicine) seemed to have a stronger sense of belonging than those in the central unit, and this was thought to be because they felt they belonged to the discipline itself and that medicine had a long history of educational development. In addition, the EDSSU works only for staff and to support curriculum and teaching. These academics were embedded as a team and not as seconded individuals. In contrast, the HEDC is a central department that works with undergraduate and postgraduate students, academic and administrative staff, and senior management. Its work includes holistic academic support (e.g., helping develop teaching, research, careers, academic skills and so on) (Sutherland, Citation2018), and it provides this development work for all disciplines. This situation requires developers with specialist research knowledge (e.g., in research methods, education technology, careers, and quality assurance) and so each may have varying interpretations and experiences of their AD work.

In Japan, the permanent developers in the centralised FD unit expressed stronger ideas about identity than nearly all temporary developers, but at this stage did not have the wide-ranging roles of their NZ equivalent. The main work was to provide a course mainly for university teachers and postgraduate students. Makiko and Masao from the central unit said their work was clearly about improving the quality of teaching. They both shared the same educational philosophy which resulted in a strong foundation on which to build their identity: ‘We [Masao and I] share the same educational philosophy. […] we can feel that we share the same philosophy by seeing what we prioritise in education’ (Makiko, Japan). In contrast, the embedded developers still had full academic jobs in their home discipline, and development work was done in addition to this. Their main work included leadership among fellow academics in raising awareness for improving teaching and learning (Sachiko), directing a newly founded institute and strengthening its foundation for research (Ayako), supervising junior academics on their personal and professional development (Mariko), promoting medium of instruction in languages other than Japanese (Anne and Maria), or different combinations of the above. All had a strong home discipline identity. Overall, and in all cases, whether central or embedded, permanent or temporary, all those doing development work showed a strong sense of responsibility towards this, even if they did not share belongingness.

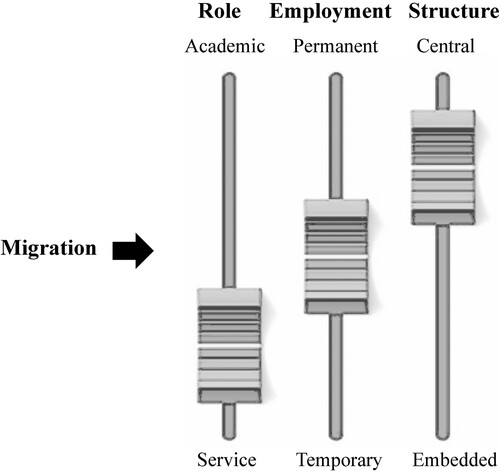

In , we present a model to illustrate the three workplace factors. The figure starts with initial migration into AD and then role, employment, and structure as the major determinants of how AD is enacted in this context. The ‘sliders’ represent a continuum between two finite ends. To illustrate, our study on how developers perceive their roles suggested that the slider will never reach the academic end of the scale. Participants described subtle differences in how they perceived the workplace, but these three factors were key for all. Overall, the most important determinant of professional identity was employment in an AD role, which varies between permanent and temporary.

Conclusion

Developers with a stronger academic component in their role were better able to build a stronger knowledge base, thus, had more opportunities to construct a firmer identity on which to grow as developers. While AD may not yet have the knowledge base of a discipline (Boughey, Citation2022; Shay, Citation2012), it is sufficiently an academic field to serve as a source of identity, similar to established disciplines (Henkel, Citation2005). Those with permanent AD positions tended to express a different identity than those with temporary positions. Developers in a temporary position in the Japan example showed a professional identity that was static rather than dynamic, and the destination for temporary migrants was such that it did not require them to depart from their home disciplines. Even if these developers lost their positions as developers, they still had work in their home disciplines, which implies a stable environment from which to conduct FD work but little incentive to embrace this new field.

For permanent migrants, the destination entailed full membership of AD, but this did not give security of employment as this type of work is relatively unstable in many parts of the world. According to Sword (Citation2022), declining resources make developers vulnerable to reorganisation, and we would add that it is one of the parts of a university that is easy to change when change is called for. Most regular academic departments have similar responsibilities, contract expectations, and structures. In contrast, AD is enacted in many ways within each university, and with a variety of contract types, and even without contracts when positions are available for volunteer developers like in the Japan case. There is no one model, and so this provides management with an opportunity to experiment with jobs and structure.

Focusing on structure, it was unclear if this alone showed clear differences in professional identity. In the New Zealand case, developers in the embedded unit in medicine seemed to have formed and grown their developer identity in a unified manner as an academic ‘family’ compared to those in the central AD unit, where developers had a strong independent professional identity, conducting research in the area of their respective expertise. However, these differences are complicated by time spent in the role and how service itself was understood. In the Japan case, those in the central FD unit expressed a stronger developer identity compared to those in the temporary positions and embedded. Accordingly, while role and employment factors elicited certain features of developer identity formation and growth, it was unclear whether the embedded-central structures reflect significantly different developer identities. However, findings also revealed that the combination of time and experience alone does not account for a developer’s conception of identity, and many other factors will be at play, including ‘social, emotional, and cognitive dimensions’ (Cavazos Montemayorr et al., Citation2020, p. 3).

Overall, our examination of workplace factors suggests that forming and growing an AD identity is easier where the role factor is more academic than service oriented (Harland & Staniforth, Citation2008), and the employment factor is more permanent than temporary (Fruisting, Citation2017). These conditions allow for a stronger knowledge base and work continuity (Shay, Citation2012; Vorster & Quinn, Citation2015), which in turn gives greater stability. As such, workplace factors will certainly have a considerable impact on other aspects that are known to affect AD identity such as liminality, agency, and community (Mori et al., Citation2022). For example, temporary contracts are likely to be the main cause of liminality.

There are two main ramifications stemming from these conclusions. First, if those in academic leadership positions value AD and want to create an environment where it can thrive, they should pay more attention to the workplace factors identified here. The employment factor, oscillating between permanent and temporary, seems to be of particular importance. Second, workplace factors reflect different AD concepts, values, and financial or resource commitments. Therefore, all three workplace factors are rooted in political and financial decisions. Improving the prospects of AD in an institution will require the alignment of these with the vision that the institution has for the provision of AD, and developers will need to be part of this conversation. The study showed that it was possible to enter AD with a set of beliefs and values, but these may not be realised when the institution (that largely determines the work required) decides otherwise.

The embedded model, if enacted in all disciplines, would be incredibly expensive for any institution and not viable at all in small departments. The centralisation of AD seems to make more sense in this respect. In our study, the central unit in New Zealand had research and teaching as a priority. The subjects that academics were interested in were within the field of higher education, which included the field of AD (see Clegg, Citation2012), and what they taught through academic courses, postgraduate study, and other forms of AD was research led. However, those being taught (clients, customers?) came from the whole university community, and so this rendered teaching as more of a service. Again, this promotes a liminal space. At the same time, both institutions in our study are founded on research-led teaching for students, and it was unclear if the same principle was seen as essential for teaching by developers. If institutions, their staff and students, and developers themselves see AD teaching as a service that does not require the developer to be a researcher, then they need to live with double standards. Such an unprincipled position devalues AD knowledge and work.

Developers have always lacked influence over their structure and operations (Harland & Staniforth, Citation2003), and this situation seems to remain. That the field is still fragmented with no unified direction is propagated as each university designs its own structures while individual developers protect their personal patch and market their strengths in the hope of maintaining their jobs. These impacts on identity must be stronger than any other determinants, and they directly influence liminality, what is accepted as a community, and a sense of personal and collective agency. At the same time, AD is still present in various forms in most universities across higher education, and individuals that practice it do share some values, if not identities. Perhaps the field will always be characterised by complex differences and never unified in the way traditional academic work or professional work (with common entry requirements, practices, and standards) has been. This paper forms a part of an attempt to theorise the complex phenomenon of AD professional identity. While the findings presented here are based on two specific institutions, they are transferable to other contexts as academic developers worldwide must all work within certain contractual settings. With that, there is certainly scope for further research on this issue. The question then remains if such a fragmented and complex situation of AD does impact on the quality of institutional provision, and if a particular configuration of workplace factors is more advantageous than another. The data we have presented suggests this will be the case.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our participants for volunteering to take part in this study and for sharing their valuable insights. We are also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bauman, Z. (1996). From pilgrim to tourist – or a short history of identity. In S. Hall, & P. Du Gay (Eds.), Questions of cultural identity (pp. 18–36). Sage.

- Boughey, C. (2022). Not there yet: Knowledge building in educational development ten years on. Teaching in Higher Education, 27(8), 992–1004. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2022.2121158

- Brewer, M. B., & Gardner, W. (1996). Who is this ‘we’? Levels of collective identity and self representations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(1), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.1.83

- Broscheid, A. (2019). Educational development between faculty and administration. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 159(159), 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20347

- Carew, A. L., Lefoe, G., Bell, M., & Armour, L. (2008). Elastic practice in academic developers. International Journal for Academic Development, 13(1), 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440701860250

- Cavazos Montemayorr, R. N., Elizondo-Leal, J. A., Ramírez Flores, Y. A., Cors Cepeda, X., & Lopez, M. (2020). Understanding the dimensions of a strong-professional identity: A study of faculty developers in medical education. Medical Education Online, 25(1), 1808369. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2020.1808369

- Clegg, S. (2012). Conceptualising higher education research and/or academic development as ‘fields’: A critical analysis. Higher Education Research & Development, 31(5), 667–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.690369

- Cruess, R. L., Cruess, S. R., Boudreau, J. D., Snell, L., & Steinert, Y. (2014). Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Academic Medicine, 89, 1446–1451. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427

- Daniel, B. K. (2018). Contestable professional academic identity of those who teach research methodology. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 41(5), 548–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2017.1369510

- Fitzpatrick, K. (2019). Generous thinking: A radical approach to saving the university. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Fruisting, B. (2017). Professional identity among limited-term contract university EFL teachers in Japan. In P. Clements, A. Krause, & H. Brown (Eds.), Transformation in language education (pp. 45–54). JALT.

- Fyffe, J. M. (2018). Getting comfortable with being uncomfortable: A narrative account of becoming an academic developer. International Journal for Academic Development, 23 (4), 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2018.1496439

- Gunn, A. C., Berg, D., Hill, M. F., & Haigh, M. (2015). Constructing the academic category of teacher educator in universities’ recruitment processes in Aotearoa, New Zealand. Journal of Education for Teaching, 41(3), 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2015.1041288

- Harland, T., & Staniforth, D. (2003). Academic development as academic work. International Journal for Academic Development, 8(1-2), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144042000277919

- Harland, T., & Staniforth, D. (2008). A family of strangers: The fragmented nature of academic development. Teaching in Higher Education, 13(6), 669–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510802452392

- Henkel, M. (2005). Academic identity and autonomy in a changing policy environment. Higher Education, 49(1), 155–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-2919-1

- Henkel, M. (2016). Multiversities and academic identities: Change, continuities, and complexities. In L. Leišytė, & U. Wilkesmann (Eds.), Organizing academic work in higher education: Teaching, learning and identities (pp. 205–222). Routledge.

- Henkel, M., & Vabø, A. (2006). Academic identities. In M. Kogan, M. Henkel, M. Bauer, & I. Bleiklie (Eds.), Transforming higher education: A comparative study (2nd ed., pp. 127–159). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-4657-5_7

- Kensington-Miller, B., Renc-Roe, J., & Morón-García, S. (2015). The chameleon on a tartan rug: Adaptations of three academic developers’ professional identities. International Journal for Academic Development, 20(3), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2015.1047373

- Kinash, S., & Wood, K. (2013). Academic developer identity: How we know who we are. International Journal for Academic Development, 18(2), 178–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2011.631741

- Laksov, K. B., & Huijser, H. (2020). 25 years of accomplishments and challenges in academic development—Where to next? International Journal for Academic Development, 25(4), 293–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2020.1838125

- Little, D., Green, D. A., & Felten, P. (2019). Identity, intersectionality, and educational development. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2019(158), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20335

- Macfarlane, B. (2011). The morphing of academic practice: Unbundling and the rise of the para-academic. Higher Education Quarterly, 65(1), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2010.00467.x

- Manathunga, C. (2007). ‘Unhomely’ academic developer identities: More post-colonial explorations. International Journal for Academic Development, 12(1), 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440701217287

- McCowan, T. (2017). Higher education, unbundling, and the end of the university as we know it. Oxford Review of Education, 43(6), 733–748. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2017.1343712

- Mori, Y., Harland, T., & Wald, N. (2022). Academic developers’ professional identity: A thematic review of the literature. International Journal for Academic Development, 27(4), 358–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2021.2015690

- Moses, I. (2012). Views from a former vice-chancellor. International Journal for Academic Development, 17(3), 275–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144x.2012.701094

- Muthama, E., & McKenna, S. (2024). The whole is greater than the sum of its parts: A case study of the nexuses between teaching, research and service. Higher Education Research & Development, 43(1), 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2023.2215182

- O’Sullivan, P. S., & Irby, D. M. (2014). Identity formation of occasional faculty developers in medical education: A qualitative study. Academic Medicine, 89(11), 1467–1473. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000374

- Popovic, C., & Fisher, E. (2016). Reflections on a professional development course for educational developers. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 53(5), 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2015.1121160

- Rowland, S. (2007). Academic development: A site of creative doubt and contestation. International Journal for Academic Development, 12(1), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440701217238

- Shay, S. (2012). Educational development as a field: Are we there yet? Higher Education Research & Development, 31(3), 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2011.631520

- Sternszus, R. (2016). Developing a professional identity: A learner’s perspective. Theoretical insights into the nature and nurture of professional identities. In R. L. Cruess, S. R. Cruess, & Y. Steinert (Eds.), Teaching medical professionalism: Supporting the development of a professional identity (2nd ed., pp. 26–36). Cambridge University Press.

- Sutherland, K. A. (2018). Holistic academic development: Is it time to think more broadly about the academic development project? International Journal for Academic Development, 21(4), 261–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2018.1524571

- Sword, H. (2022). Diving deeper: The redemptive power of metaphor. In J. Hansen, & I. Nilsson (Eds.), Critical storytelling: Experiences of power abuse in academia (pp. 125–129). Brill.

- Vorster, J. A., & Quinn, L. (2015). Towards shaping the field: Theorising the knowledge in a formal course for academic developers. Higher Education Research & Development, 34(5), 1031–1044. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1070126

- Weimer, M. (2007). Intriguing connections but not with the past. International Journal for Academic Development, 12(1), 5–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440701217204

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.