ABSTRACT

Objectives

The purpose of this quality improvement project was to evaluate the implementation of a person-centered communication tool in nursing homes (NH). The Preferences for Activity and Leisure (PAL) Cards were developed to communicate residents’ preferences for activities across care team members.

Methods

Providers were recruited to assess resident important preferences and create PAL Cards for 15–20 residents and collected data aligned with the RE-AIM framework.

Results

Reach and Adoption: A total of 43 providers registered and 26 (60%) providers completed the project. Effectiveness and Implementation: Participants attempted 424 PAL Cards and completed 406. For the 26 providers, the average acceptability of the intervention measure was 4.7 (SD 0.4), intervention appropriateness measure was 4.5 (SD 0.5), and feasibility of intervention measure was 4.6 (SD 0.5) (all out of 5). Maintenance: Providers were able to complete 82% of PAL Card placement over the course of 5 months.

Conclusions

The majority of providers were successful in implementing PAL Cards for residents and reported the intervention as highly acceptable, appropriate, and feasible providing necessary data to inform future effectiveness trials.

Clinical Implications

The intervention can assist nursing home providers in meeting PCC regulations and contribute to building relationships between residents, family, and staff.

Introduction

Nursing homes (NH) are shifting toward a person-centered philosophy of care (PCC). PCC seeks to understand each individual’s preferences, goals and values, and to honor them throughout the care delivery process (Brummel‐Smith et al., Citation2016; Koren, Citation2010). The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the largest payer of long-term services and supports (LTSS), has supported PCC via federally mandated regulations. For example, all CMS funded NHs are required to assess a subset of individual-level preferences annually through the Minimum Data Set (MDS 3.0) Preference Assessment Tool (Saliba & Buchanan, Citation2008). The goal for assessing important preferences is that they can guide day-to-day care leading to better outcomes for residents. Interventions that tailor care to individual needs and preferences lead to improved positive affect (Van Haitsma et al., Citation2015), greater engagement, alertness, and attention (Kolanowski, Litaker, Buettner, Moeller, & Costa, Citation2011), decreases in hallucinations, agitation, anxiety, aggression, sleep disorders, and aberrant motor behavior (de Oliveira et al., Citation2019).

The concept of recreational preference congruence has been put forward as one way to operationalize and measure person-centered care. Recreational preference-congruence is the match between important resident preferences for how they spend their leisure time and attendance/engagement with activities offered, which is hypothesized to lead to greater well-being (VanHaitsma et al., Citation2020). Methods of tracking recreational preference congruence have been developed and tested (Van Haitsma et al., Citation2016) and prior research has found that having more important preferences is associated with greater preference-congruent care. However, individual clinical characteristics, such as visual limitations, language comprehension, and incontinence were found to negatively impact preference-congruent care (Heid, Van Haitsma, Kleban, Rovine, & Abbott, Citation2017).

Despite the finding that communicating and integrating resident preferences is an important aspect of person-centered care, communication of individual preferences across employees in different departments and shifts has proved difficult to implement in the dynamic, complex care environment of the nursing home (Elliot & Barsness, Citation2016).Person-centered tools that communicate individuals’ psychosocial needs have been tested in both acute and long-term care settings, with demonstrated positive outcomes on communication and care. In hospitals, interventions including patient whiteboards (Tan, Evans, Braddock, & Shieh, Citation2013) and the Tell-Us Card (Jangland, Carlsson, Lundgren, & Gunningberg, Citation2012) improved the quality of care and increased patients’ involvement and knowledge of their care. Evidence-based communication tools in nursing homes include using Talking Mats (Murphy, Gray, Van Achterberg, Wyke, & Cox, Citation2010) and memory books (Dijkstra, Bourgeois, Burgio, & Allen, Citation2002) that are used to improve communication for individuals with dementia. Collecting and sharing residents’ life stories is another common strategy to communicate biographical information (Ginsburg et al., Citation2018). Evidence-based interventions such as these continue to play an important role in enhancing the person-centeredness of healthcare organizations.

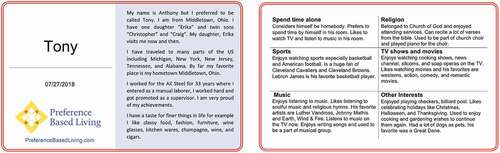

Intervention co-development

NH providers explained that after assessing an individual’s preferences, they struggled to communicate the information across care team members. Providers asked for a quick way to reference individual resident preferences that could travel with them throughout the organization, such as on the back of their wheelchair, or attached to a walker. We collaborated with four nursing home providers to co-design a communication tool called Preference for Activity and Leisure (PAL) Cards based upon evidence-based communication models used in similar settings (Dijkstra et al., Citation2002; Tan et al., Citation2013). PAL Cards are 5 × 7 inch, portable cards that display a resident’s name, biography, and important activity preferences, such as hobbies (see ). We utilized the Readiness Assessment for Pragmatic Trials (RAPT) framework to help guide the development of the intervention protocol to ensure that the intervention was designed pragmatically (Baier, Jutkowitz, Mitchell, McCreedy, & Mor, Citation2019).

Preference for activity and leisure (PAL) card intervention protocol

Step 1: selecting preference interview items

The intervention protocol starts with helping providers select items that would allow them to better assess an individual resident’s important preferences. Providers were given the choice to either use the 8 activity items from the Preference Assessment Tool (PAT) in the Minimum Data Set (MDS) 3.0 (Saliba & Buchanan, Citation2008) or select additional items from the Preferences for Everyday Living Inventory (PELI) PELI-NH (Van Haitsma et al., Citation2013). The PELI-NH includes 72-questions that cover five psychosocial preference domains including (1) Self-Dominion (e.g., having privacy, choosing what to eat), (2) Enlisting others in care (e.g., having a caregiver be of the same gender), (3) Leisure and Diversionary (e.g., watching television), (4) Social Contact (e.g., meeting new people), and (5) Growth Activities (e.g., exercise). Respondents are asked to respond to a question stem that starts with “How important is it to you to … [insert preference]” with a 4-point Likert scale of 1 (very important) to 4 (not important at all) and have additional prompts that allow providers to delve more deeply into the specific aspects of resident preferences. The PELI-NH is a tool that has been subject to extensive reliability and validity development for pragmatic use in the nursing home setting (Heid et al., Citation2016; Van Haitsma et al., Citation2014, Citation2013) and informed the development of the PAT.

Because the PELI-NH items have been developed to be ideographic, “stand alone” individual items (PELI-NH does not have traditional nomothetic scaled scores), providers had the option of selecting which and how many items they wished to use in their assessment process. At a minimum, providers were encouraged to use the 8 activity items from the PAT since those items are routinely captured in required assessment processes in all nursing homes that receive CMS reimbursement for clinical services, making these items the ideal pragmatic starting point for any provider. The 34 recreation and leisure items from the PELI-NH were the maximum number of items providers selected from (and included the 8 PAT items; See ). The 34 items of the PELI-NH encompass three of the five preference domains represented in the PELI (i.e., Leisure and diversionary activities, growth activities, and social contact).

Table 1. Domains and items from the Preferences for Everyday Living Inventory (PELI-NH) that comprise the 34-items utilized for Preference for Activity and Leisure (PAL) cards

Step 2: selecting residents

All residents in the provider communities were eligible to receive a PAL Card unless they decline to have one created for them. Providers were encouraged to select 15–20 residents in their community for the pilot effort. Providers could include residents without cognitive or communication impairments in their pilot testing of the intervention as these individuals are able to easily communicate their own preference information. Alternatively, providers could choose to begin with residents who have cognitive or communication impairments as these individuals would benefit the most from a tool that enhances communication between residents and staff. If the individual selected to receive a PAL Card was unable to communicate their preferences, providers were instructed to interview family members or staff via the selected PELI-NH questions to complete a PAL Card.

Step 3: interviewing the resident

After identifying potential residents to receive a PAL Card, providers asked if they would like a PAL Card created for them. Providers were encouraged to share a sample PAL Card with the resident and explain the purpose. If the resident agreed, the provider could begin the preference interview and they were encouraged to pay attention to the resident’s emotional response to the questions. If the resident was excited to talk about a preference and shares details or begins to reminisce on the topic, staff were instructed to take note of this item (either by circling, highlighting, etc.) as these are the details they will want to include on the resident’s PAL Card. Individuals who were more private people usually declined and we coached staff to respect their privacy and not create a PAL Card for those individuals.

Step 4: creating the PAL Card

Providers downloaded the PAL Card template, available at no cost, from our website https://www.preferencebasedliving.com/. The template is a Word document with fixed fields allowing direct entry of information gathered during the preference interview. The front of each PAL Card includes space for a short biography. The back of the card is personalized to highlight six recreation and leisure preference items that were reported as “important” during their interview, brought a smile to the resident’s face, and they were excited to share details about. The sections on the back will vary depending on the unique interests of each resident (See ).

Step 5: consultation with resident and/or family member

We recommended that the PAL Card be reviewed with the resident to ensure it accurately reflects his/her interests before it is laminated. If the resident notes any discrepancies, the card is updated with the correct information. For residents living with dementia, a family member or proxy could be asked to review the information on the card. In cases where family/proxies report inaccuracies of resident reports, providers are encouraged to update the card with the details shared by the family/proxy.

Step 6: placement of PAL card

The resident is asked where they would like the card to be placed. We recommend that it be placed on an assistive mobility device (e.g., wheelchair or walker) so that the card can travel with the individual throughout the community. Alternatively, the PAL Card can also be adhered to a resident’s door. Some providers may choose to place the cards in one central location, such as a break room bulletin board. If individuals were not comfortable sharing the information publicly, the PAL Card could be placed in a more private area, such as inside a closet door. Regarding HIPAA Privacy, we coached providers on the data elements that are included as part of protected health information, such as birthdates, and advised champions not to include those data elements on the card. We have been repeatedly advised by HIPAA Privacy Officers that preferences for activities are not considered protected health information.

In our training sessions, we offered suggestions for ways providers could use the PAL Cards. For example, we encourage staff and volunteers to read a resident’s card prior to interacting with them to assist in using their preferred name and to identify topics of conversations. PAL Cards can be used for a one-on-one reminiscing activity, or shared on a bulletin board for staff and residents to view. Physical therapy can use the cards to identify goals to help motivate residents. Staff have also used the cards to identify ways of comforting residents when they are experiencing distress. In addition, we suggested that the champion introduce the PAL Cards during staff meetings, huddles, or town hall meetings to explain the purpose of the cards and expectations that staff should read the cards to support meaningful engagement with residents.

Ohio nursing homes are required to complete one quality improvement project (QIP) approved by the Ohio Department of Aging (ODA) every other year (Ohio Administrative Code, Citationn.d.). To facilitate alignment of the intervention with stakeholder priorities to comply with this requirement, the PAL card intervention protocol was designed to be utilized in the context of a QIP to enhance communication of important resident leisure preferences in their daily life. Quality improvement (QI) is one type of implementation science, which is required by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). CMS requires NHs to participate in quality assurance and performance improvement activities (QAPI). However, NH providers struggle to engage and sustain QAPI because of resource constraints, staff turnover, and heavy workloads (Ginsburg et al., Citation2018). To successfully and sustainably engage nursing home providers in adopting evidence-based practices, implementation science principles are needed (Eccles & Mittman, Citation2006). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the implementation of an evidence-based communication intervention call Preferences for Activity and Leisure (PAL) Cards. Specifically, we sought to identify if nursing home providers identified the intervention as feasible, acceptable, and appropriate as a precursor to a full effectiveness trial.

Methods

We sought to evaluate the implementation of the PAL Card project with NH providers participating in a quality improvement project. We utilized the RE-AIM framework (Glasgow, Vogt, & Boles, Citation1999) to evaluate the QIP (see measures below for more details). The Miami University IRB Approved this study (protocol #02686r The Acceptability, Appropriateness, and Feasibility of implementing PAL Cards in the Nursing Home setting). Verbal consent to participate was received by the provider participants. Since this study was conducted virtually (no in person communication), the IRB decided that written consent was not necessary for this study.

Recruitment strategies

The PAL Card QIP was advertised for two months on the ODA website (Ohio Department of Aging, Citationn.d.) and included in a monthly newsletter disseminated to all nursing home administrators in Ohio. In addition, we discussed the project during a presentation at an activities professional conference to approximately 80 individuals. Providers were asked to complete a short on-line questionnaire to sign up for the project and indicate contact information for the person at the organization who would lead the QIP efforts (provider champion).

Implementation strategy

The project manager conducted an initial one-hour virtual training for provider champions via Webex. Per best practice recommendations from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), we encouraged providers to start small and pilot the PAL Card intervention with approximately 15–20 residents. Starting with a pilot allows for the collection of information needed to either decide whether or not they have the necessary resources to implement the intervention with all residents in their community (Institute for Healthcare Improvement, Citationn.d.). The initial training also included guidance on all the steps in the intervention protocol described above. Participants received a tour of PreferenceBasedLiving.com, where all materials needed for the project (preference interviews, editable PAL Card Word Document template, and PAL Card Implementation tip sheet with step-by-step instructions) were made available at no cost.

The project manager created a checklist that delineated each step of the process, data collection forms that identified what data to record, and instructions for joining WebEx meetings. Following the initial training session, we utilized a monthly group-coaching model to replicate a virtual learning circle collaborative (Action Pact, Citationn.d.; Keane, Citation2020). The goal of the monthly coaching calls was to give provider champions the opportunity to problem solve common solutions together.

Criterion used to define successful completion of the program were developed in coordination with ODA. In order for providers to receive a certificate of completion, providers were required to: participate in online training (1 hour), conduct preference interviews (choice of the 8 activity items from MDS 3.0 Section F or selection of up to 34 items from PELI-NH) (Saliba & Buchanan, Citation2008; Van Haitsma et al., Citation2013), participate in three monthly virtual coaching calls, orient staff to PAL Cards, create and place PAL Cards for 15–20 residents, collect data, submit pictures of placed PAL Cards, and complete a final individual telephone interview. The ODA also required providers to document in residents’ care plans their consent to having a PAL Card made and displayed publicly.

Measures

This study utilized Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Measurement (RE-AIM) to evaluate the PAL Card intervention (Glasgow et al., Citation1999). The measurement of each RE-AIM element was as follows: Reach was assessed by the number of providers who responded out of the total number of providers invited. Potential participants in this QIP study included all 980 NHs in the state of Ohio. Reach was calculated by the number of NHs out of 980 that indicated an interest in participating in the QIP program. In addition, characteristics of organizations that registered for the project were pulled from Nursing Home Compare (https://www.medicare.gov/care-compare/?providerType=NursingHome&redirect=true), which are data provided by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services as a service to the public. Effectiveness was assessed by asking nursing home provider champions if they viewed the PAL Cards as acceptable, feasible and appropriate. We utilized three pragmatic measures, 1) Acceptability of Intervention Measure (AIM), 2) Intervention Appropriate Measure (IAM), and 3) Feasibility of Intervention Measure (FIM) (Weiner et al., Citation2017). Acceptability is the perception among stakeholders that the intervention is agreeable, palatable, and satisfactory. Appropriateness is the perceived fit, relevance, or compatibility of the innovation for a given setting, provider, or consumer. Feasibility is the extent to which the intervention can be successfully carried out within the given setting. Each measure consists of 4 items and were asked during the final telephone interview at the conclusion of the project. We inserted the words “PAL Cards” where the scale suggests listing the Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) (e.g., I welcome Pal Cards, The PAL Cards seem fitting, The PAL Cards seem easy to use). Response options include: completely disagree (score =1), disagree (score = 2), neither agree nor disagree (score = 3), agree (score = 4), and completely agree (score = 5). Higher average scores indicate greater acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility. The reported Chronbach’s alpha coefficients for each measure are high with AIM alpha .84, IAM alpha of .92, and FIM of .92 (Weiner et al., Citation2017).

Adoption was measured by the number of provider champions who completed all project requirements. Implementation was measured by the fidelity to the requirements of the project as well as costs of the intervention, based upon staff time needed to implement the intervention. Implementation costs were estimated by multiplying the average time invested in conducting the preference interview and creating the PAL Card by average wages of staff involved (e.g., social worker, activities, nursing). We estimated a per resident cost of the intervention to the organization by multiplying the average preference interview time by the average salaries of occupations (including fringe rates) pulled from salary.com to calculate the cost of conducting the preference interview, creating the PAL Card, and added in the cost of printing one page in color and lamination. Finally, Maintenance was assessed by whether the PAL Card remained in place (e.g., card still in original location vs. card missing) five months after initiation of the project.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated using IBM SPSS v27.

Results

Reach & adoption

We had a total of 43 nursing home provider champions sign up for the project. Interestingly, 41providers were from Ohio, and two of the organizations were located in other states (Pennsylvania, Virginia). Forty providers attended the virtual training and 35 began implementation (See ). For our Adoption measure, 26 (74%) providers completed all requirements of the project. Providers attempted an average of 16.4 (SD =6.0) PAL Cards and completed 15.9 (SD = 6). In total, 424 PAL Cards were attempted and 406 PAL Cards were completed and placed.

The characteristics of providers who completed the project included 54% (n = 14) not for profit or government owned, and 46% (n = 12) that were for profit. Their average bed size was 87; while their average star rating was 3.7 (SD 1.1) with a range from 1–5 (See ). The characteristics of providers who did not complete the project included 12% (n = 2) not-for-profit and 88% (n = 15) for profit. Their average bed size was 74 while their average star rating was 3.5 (SD 0.7) with a range from 1–5 (see ). The provider champions who completed the project were female and employed as Activity Directors (84%; n = 22), Administrators (12%; n = 3), and Directors of Nursing (4%; n = 1). The champions who did not complete the project were employed as Activity Directors (59%; n = 10), Administrators (12%; n = 4); Directors of Nursing (12%; n = 2), and Social Services (5%; n = 1).

Table 2. Characteristics of organizations who completed and did not complete the PAL card project

The project manager held 10 training sessions with a total of 40 participants (an average of 4 participants per training and a range of 1–6). Some provider champions had additional staff participate in the training session. In addition, the project manager held a total of 37 monthly coaching calls in the subsequent three months after the initial training (an average of 12 per month) with provider champions. Monthly calls had fewer participants with an average of 2 participants lasting 18 minutes (range 3–35 minutes).

Effectiveness

Provider champions reported that the PAL Card intervention was highly acceptable, feasible, and appropriate (see ). The Chronbach’s alpha of the measures in this study were 0.79 for the AIM, 0.85 for the FIM, and 0.92 for the IAM.

Table 3. The acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness of the PAL card intervention measure as rated by n = 26 nursing home providers

Implementation

Staff from multiple departments contributed to the implementation of 424 PAL cards. Activity professionals completed 72.7% of PAL cards, volunteers completed 17.3%, nursing 5.7%, and 4% were completed by another individual (e.g., family, therapy personnel, social worker). Family were engaged in providing some or all information for 11% of PAL Cards (n = 45). Providers were given the choice of which version to use and 40% (n = 168) of PAL Cards were created via the 8 activity items from the PAT while 56.4% (n = 237) were created via 34-items from the PELI-NH. One provider chose to create a version that was 10 items. Providers selecting the 8 activity items from the PAT reported taking an average of 26.8 minutes to complete the preference interview (SD 20.5 minutes; Median 20 minutes, Mode 30 minutes, Range 5 to 120) and 22.6 minutes to create PAL Cards (SD 19.6 minutes; Median 16 minutes, Mode 10 Minutes, Range 2–120). Providers selecting the 34 activity and leisure items from the PELI-NH reported taking an average of 43 minutes (SD 22.1; Median 40, Mode 30 Minutes, Range 7 to 120 minutes) to complete the preference interview. For those creating PAL Cards using the 34 items preference interview it took on average 22 minutes to create PAL Cards (SD 9.5; Median 20, Mode 30, Range 3–50 minutes).

All of the PAL Cards completed (n = 406) were reviewed for accuracy by the resident and/or family and were reported to be accurate in 92.5% (n = 381) of cases. For cards that were reported to be inaccurate, individuals wanted to add more details or the family member (e.g., wife, daughter) reviewed the card and found mistakes for individuals who had cognitive impairment. PAL cards were placed on resident’s wheelchairs (n = 220; 53.5%), walkers (n = 62; 15.1%), door (n = 93; 22.6%), and other location (n = 36; 8.8%; e.g., in the resident’s room such as the closet door, dresser, over the bed, on the wall, IV pole, geri-chair, bulletin board).

Based on the average time to conduct the preference interview and create the PAL Card, we estimate that implementation costs to the organizations are between 13.04 USD – 27.35 USD per resident. This does not account for time needed for training and depends on whether staff or volunteers are completing the preference interviews and creating the PAL Cards (see ). In addition, these costs would be in the first three to four months of implementation. It is possible that costs could go down as the learning curve flattens.

Table 4. Estimated cost of PAL card initial implementation per resident

Maintenance

A total of 424 PAL cards were attempted and (82%) were completed in five months. Reasons why PAL Cards were not completed included resident refusals (n = 7), deaths prior to completion (n = 2), discharges prior to completion (n = 1), and residents being unable to complete the preference interview (n = 8). The majority of PAL Cards (68%) had been placed by month 3 (See ). Providers reported that less than 2% of the PAL Cards were missing, moved to another location, or needed to be replaced.

Table 5. PAL card placement by month (n = 424)

Discussion

Overall, the majority of providers were successful in completing the PAL Card quality improvement project. Providers implemented PAL Cards with virtual coaching support and reported them to be feasible, acceptable, and appropriate in the NH environment. Offering the intervention as a state-approved quality improvement project facilitated provider recruitment. By advertising the project through multiple avenues, including conferences and newsletters, providers of varying locations, sizes, for-profit status, and star ratings were reached. Providers dropped out for numerous reasons, but the most common cause was leadership and/or staff turnover. Leadership turnover has been identified as a barrier in other nursing home quality improvement studies (Rantz et al., Citation2012; Woo, Milworm, & Dowding, Citation2017). Dedicated high-level leaders and project champions are essential to keeping a project on track, so turnover in these key positions made it challenging to move the project forward (Ginsburg et al., Citation2018).

Providers who completed the project perceived the intervention to be effective via three pragmatic outcome indicators associated with adoption of evidence-based practices (Proctor et al., Citation2011). First, the intervention was reported as acceptable or appealing. Providers welcomed the PAL Cards and reported that they met their approval. Second, the intervention was perceived as appropriate or compatible in the nursing home setting for use with residents and families to communicate important preferences. Providers reported that the PAL cards were suitable and seemed like a good match. Third, PAL Cards were deemed feasible. Providers reported that the evidence-based intervention was implementable, possible, doable, and easy to use. In addition, residents reported that the information on the PAL Cards was highly accurate. This validates prior research that shows that older adults can communicate their preferences, and preferences remain stable over time (Abbott, Heid, Kleban, Rovine, & Van Haitsma, Citation2018).

The built-in flexibility of the intervention was an aspect that led to success. Providers had choice and could adapt the intervention to their context in a number of ways. Providers could choose from a shorter, 8-item preference interview or a longer 34-item version. Some providers started with 8-items, but added additional items when they felt limited in the information obtained. There was also flexibility in terms of who implemented the intervention. Staff from a variety of positions including social work, activities, nursing, and volunteers took on roles in the project. Some providers used teams of staff, while others took on the project solo (either by choice, or by necessity).

The flexibility in approach led to a wide range of times to complete the preference interviews and PAL Cards. Some providers viewed the preference interviews as more of a relationship-building activity, and, for example, interviewed residents over lunch, which increased the time. Other providers took a more focused approached and tried to complete the cards as quickly as possible to fit in with their other job responsibilities. Comfort levels with technology influenced the time needed to create the PAL Cards, as some providers who lacked the technical skills, such as how to download a file, needed more time to learn the process. The flexibility providers had regarding placement of the PAL Card also assisted with meeting their needs. Our initial recommendation was to have the resident decide where their card was placed. During the project, some providers reported it was easier to have a uniform location for all PAL Cards in their community, such as on a bulletin board or by residents’ doors. This allowed staff to consistently know where to find the cards. Finally, family members played an important role in the project, especially in providing information about residents’ preferences. While we have always acknowledged the potential to involve family in the process, especially as proxies for residents who are unable to communicate, we knew it would add complexity to the project. Therefore, we did not foresee providers involving families to the extent they did in this project, nor did we systematically ask about the assistance from family in the PAL Card process. This is an important consideration for future studies.

The implementation strategy of a virtual coach (one of the research team members) played a vital role in collaborative problem solving with providers. For example, technology was often a barrier and some providers needed one-to-one support with downloading the PAL Card template, printing and laminating the cards, and using video conference software. The coach also helped providers problem solve components of their implementation strategy. Two of the most common conversations were deciding which preference interview version to use and which residents the provider would trial the project with. Discussions with the coach helped providers adapt the intervention to their local contexts while facilitating information sharing with other providers. Finally, the research team created resources to remediate barriers, when possible. One example was that some providers struggled to collect residents’ biographical information needed for the front of the PAL Card. The team created a tip sheet addressing this topic to share with providers (available at https://www.preferencebasedliving.com/). The role of an external advisor as a problem solver has been validated in other nursing home QIPs (Ginsburg et al., Citation2018).

We estimated the cost of initial implementation in order to understand the intervention’s scalability and impact on resources (e.g., staff time). While the materials cost for the PAL Cards (paper, printing, laminating) is low, it is also based on providers already having the tools needed to create the cards, such as a printer, laminator, and lamination supplies. The staff time needed to conduct the preference interview and make the card accounts for the bulk of the intervention’s cost. We viewed this as an important investment due to the ability to build relationships between residents and staff through the process. However, we also recognized that some providers were able to use volunteers to implement the intervention. Therefore, we encouraged providers to delegate aspects of the PAL Card process when possible to contain costs and sustain the intervention.

PAL Cards remained in place throughout the duration of the project. Despite champions’ concerns that cards would be accidentally removed or lost, only a small percentage of cards went missing or needed to be replaced. One consideration to maintaining PAL Cards is that because they often are placed on a wheelchair or walker, they are at risk of being lost when these ambulatory devices are cleaned. In addition, one provider discussed how residents occasionally ended up using wheelchairs/walkers that were not their own, which caused confusion when staff would associate the PAL Cards with the wrong individual. While the majority of PAL Cards remained in place, it is unknown to what extent providers continued on with the project. Prior research on evidence-based programs has found that long-term implementation suffers once intervention supports (such as an external research team) are removed (Berta et al., Citation2019). Staff turnover is another potential barrier to maintenance if the responsibilities for interviewing and PAL Card creation are not incorporated into staff job descriptions and standard operating procedures.

Limitations and future directions

The findings of this study are limited by several factors. First, providers self-selected into the QIP project. It is possible that the characteristics of this convenience sample are different compared to providers who either chose another QIP offered by the State, or did not need a QIP during the timeframe ours was offered. In addition, we were only able to collect data from providers who completed the project. Despite multiple follow up e-mail and telephone calls, we were unable to reach some of the participants to follow-up. Therefore, we have very limited information from Nursing Home Compare on those providers who did not complete. Learning more about those who did not complete the project would help us better understand the barriers to implementation. For example, were administrators in organizations who did not complete the project less supportive than administrators of organizations who did complete the project? Additionally, all the data in this study was self-reported by the provider champion. The findings, such as time to complete preference interviews and PAL Cards, may not accurately represent the actual time as providers may have ‘rounded up’ or estimated the length of time either the interview or PAL Card creation took. In addition, the scope of the project prohibited the collection of outcome data from staff members or nursing home residents on the impact of PAL Cards. The goal of the study was to understand if the PAL Card intervention was feasible, acceptable, and appropriate as a precursor to a full effectiveness trial. Future effectiveness trials are needed that measure the impact of using PAL Cards on residents and family members (e.g., higher attendance and engagement in preferred activities, greater satisfaction with care, fewer responsive behaviors), staff (e.g., staff know resident preferences and have strategies to intervene when individuals communicate distress), and organizational outcomes (e.g., fewer complaints and citations around person-centered practices).

The cost of implementing the PAL Cards should be interpreted with caution. Staff wages used to calculate the costs were taken from online sources, which may not accurately reflect the wages of providers in Ohio. Additionally, there may be a wider range of costs than what was presented depending on the specific staff position. For example, within the category of nursing, there are a variety of positions including LPNs, RNs, and DONs, which have a wide range of salaries. We did not ask for staff to specify beyond “nursing” as a department. We estimated the value of volunteers because while volunteers may not encumber salary costs, there are costs associated with their training and supervision. We recommend that providers using volunteers be trained in how to conduct the preference interviews (training videos available at www.preferencebasedliving.com at no cost). In the future, qualitative research on PAL Card implementation is needed to understand the varying approaches providers use, including an exploration into whether certain staff or volunteers can be more successful in completing PAL Cards than other staff positions. The results of this study show a large variation in the preference interview chosen (e.g., 8-item PAT vs. 34-item PELI), how long the interview took, and PAL Card creation time, which makes it difficult to generalize to what other providers will experience. For example, we found that all of the nurses utilized the 8-item PAT while the majority of activities and volunteers used the 34-items from the PELI-NH. Future studies exploring the approach by staff position are needed. Finally, based on lessons learned from this study, we now recommend that providers have leadership support and start with a team (2–3 people) to ensure success. In addition, the use of PAL Cards needs to be reinforced and training needs to be ongoing, for example, as part of new employee orientation

Conclusion

Quality improvement programs in healthcare are mostly studied in hospital settings, with very few studies in nursing homes (Woo et al., Citation2017). This study helped fill this gap by evaluating the implementation of a quality improvement program among 26 nursing home providers. An external, virtual, QI support team and opportunities for learning helped providers problem solve and overcome barriers. Providers perceived PAL Cards to be highly acceptable, feasible, and appropriate. Compared to other care settings, nursing homes are often resource-constrained and have high staff turnover (Ginsburg et al., Citation2018), so a key feature of the PAL Cards are that they are relatively inexpensive, flexible to staff time limitations, and adds to the capacity of organizations to deliver valued person-centered care. In addition, these findings can be applied to other quality improvement interventions in residential settings, such as Assisted Living.

Clinical implications

Preference for Activity and Leisure (PAL) Cards assist with communicating residents’ preferences for important recreation and leisure interests.

Nursing home providers found the PAL Cards to be acceptable, feasible, and appropriate for use with residents.

PAL Cards assist temporary or floating staff in quickly learning about the residents they are providing care for and can help staff to initiate conversations with residents.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the nursing home providers who participated in the project as well as Morgan Liddic, a graduate student who assisted with data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbott, K. M., Heid, A. R., Kleban, M., Rovine, M. J., & Van Haitsma, K. (2018). The change in nursing home residents’ preferences over time. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 19(12), 1092–1098. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2018.08.004

- Action Pact. (n.d.). The learning circle. Retrieved from http://actionpact.com/assets/cache/learning-circle.pdf

- Baier, R. R., Jutkowitz, E., Mitchell, S. L., McCreedy, E., & Mor, V. (2019). Readiness assessment for pragmatic trials (RAPT): A model to assess the readiness of an intervention for testing in a pragmatic trial. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), 156. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0794-9

- Berta, W. B., Wagg, A., Cranley, L., Doupe, M. B., Ginsburg, L., Hoben, M., … Keefe, J. M. (2019). Sustainment, sustainability, and spread study (SSaSSy): Protocol for a study of factors that contribute to the sustainment, sustainability, and spread of practice changes introduced through an evidence-based quality-improvement intervention in Canadian nursing homes. Implementation Science : IS, 14(1), 109.

- Brummel‐Smith, K., Butler, D., Frieder, M., Gibbs, N., Henry, M., Koons, E., … Saliba, D. American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Person‐Centered Care. (2016). Person‐centered care: A definition and essential elements. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 64(1), 15–18.

- de Oliveira, A. M., Radanovic, M., Homem de Mello, P. C., Buchain, P. C., Dias, V. A., Harder, J., … Forlenza, O. V. (2019). AN INTERVENTION TO REDUCE NEUROPSYCHIATRIC SYMPTOMS and caregiver burden in dementia: Preliminary results from a randomized trial of the tailored activity program–outpatient version. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 34(9), 1301–1307. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4958

- Dijkstra, K., Bourgeois, M., Burgio, L. O., & Allen, R. (2002). Effects of a communication intervention on the discourse of nursing home residents with dementia and their nursing assistants. Journal of Medical Speech-language Pathology, 10(2), 143–158.

- Eccles, M. P., & Mittman, B. S. (2006). Welcome to implementation science. Implementation Science, 1(1), 1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-1-1

- Elliot, A. E., & Barsness, S. (2016). What’s in your bundle? Building a communication map of relational coordination practices to engage staff in individualizing care. Seniors Housing & Care Journal, 24(1), 1–19.

- Ginsburg, L., Easterbrook, A., Berta, W., Norton, P., Doupe, M., Knopp-Sihota, J., … Wagg, A. (2018). Implementing frontline worker–led quality improvement in nursing homes: Getting to “how”. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient safety, 44(9), 526–535. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjq.2018.04.009

- Glasgow, R. E., Vogt, T. M., & Boles, S. M. (1999). Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. American Journal of Public Health, 89(9), PMID: 10474547; PMCID: PMC1508772, 1322–1327. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322

- Heid, A. R., Eshraghi, K., Duntzee, C. I., Abbott, K., Curyto, K., & Van Haitsma, K. (2016). “It depends”: Reasons why nursing home residents change their minds about care preferences. The Gerontologist, 56(2), 243–255. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu040

- Heid, A. R., Van Haitsma, K., Kleban, M., Rovine, M. J., & Abbott, K. M. (2017, Nov). Examining clinical predictors of change in recreational preference congruence among nursing home residents over time. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 36(11), 1351–1369. Epub 2015 Nov 30. PMID: 26620057. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464815617288

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. (n.d.). How to improve. Retrieved from http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/default.aspx

- Jangland, E., Carlsson, M., Lundgren, E., & Gunningberg, L. (2012). The impact of an intervention to improve patient participation in a surgical care unit: A quasi-experimental study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49(5), 528–538. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.10.024

- Keane, B. (2020). The learning circle in culture change: Why use it? Retrieved from https://www.pioneernetwork.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/The-Learning-Circle-in-Culture-Change.pdf

- Kolanowski, A., Litaker, M., Buettner, L., Moeller, J., & Costa, J. P. T. (2011). A randomized clinical trial of theory‐based activities for the behavioral symptoms of dementia in nursing home residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59(6), 1032–1041. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03449.x

- Koren, M. J. (2010). Person-centered care for nursing home residents: The culture-change movement. Health Affairs, 29(2), 312–317. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0966

- Murphy, J., Gray, C. M., Van Achterberg, T., Wyke, S., & Cox, S. (2010). The effectiveness of the talking mats framework in helping people with dementia to express their views on well-being. Dementia, 9(4), 454–472. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301210381776

- Ohio Administrative Code. (n.d.). Long-term care quality initiative. Retrieved from http://codes.ohio.gov/oac/173-60

- Ohio Department of Aging. (n.d.). Nursing home quality improvement. Retrieved from https://aging.ohio.gov/wps/portal/gov/aging/agencies-and-service-providers/nursing-home-quality-improvement/

- Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., … Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

- Rantz, M. J., Zwygart-Stauffacher, M., Flesner, M., Hicks, L., Mehr, D., Russell, T., & Minner, D. (2012). Challenges of using quality improvement methods in nursing homes that “need improvement”. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 13(8), 732–738. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2012.07.008

- Saliba, D., & Buchanan, J. (2008). Development and validation of a revised nursing home assessment tool: MDS 3.0. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corp.

- Tan, M., Evans, K. H., Braddock, C. H., & Shieh, L. (2013). Patient whiteboards to improve patient-centred care in the hospital. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 89(1056), 604–609. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131296

- The Value of Volunteer Time/State and Historical Data Dataset. Retrieved from https://independentsector.org/resource/vovt_details/

- Van Haitsma, K., Abbott, K. M., Heid, A. R., Carpenter, B., Curyto, K., Kleban, M., … Spector, A. (2014). The consistency of self-reported preferences for everyday living: Implications for person-centered care delivery. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 40(10), 34–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20140820-01

- Van Haitsma, K., Abbott, K. M., Heid, A. R., Spector, A., Eshraghi, K., Duntzee, C., … Van Valkenburgh-Schultz, M. (2016). Honoring nursing home resident preferences for recreational activities to advance person-centered care. Annals of Long-Term Care, 24(2), 25–33.

- Van Haitsma, K., Curyto, K., Spector, A., Towsley, G., Kleban, M., Carpenter, B., … Koren, M. J. (2013). The preferences for everyday living inventory: Scale development and description of psychosocial preferences responses in community-dwelling elders. The Gerontologist, 53(4), 582–595. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gns102

- Van Haitsma, K. S., Curyto, K., Abbott, K. M., Towsley, G. L., Spector, A., & Kleban, M. (2015). A randomized controlled trial for an individualized positive psychosocial intervention for the affective and behavioral symptoms of dementia in nursing home residents. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 70(1), 35–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbt102

- VanHaitsma, K., Abbott, K. M., Arbogast, A., Bangerter, L., Heid, A., Behrens, L., & Madrigal, C. (2020). A preference-based model of care: An integrative theoretical model of the role of preferences in person-centered care. The Gerontologist, 60(3), 376–384. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz075

- Weiner, B. J., Lewis, C. C., Stanick, C., Powell, B. J., Dorsey, C. N., Clary, A. S., … Halko, H. (2017). Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implementation Science, 12(1), 1–2. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0635-3

- Woo, K., Milworm, G., & Dowding, D. (2017). Characteristics of quality improvement champions in nursing homes: A systematic review with implications for evidence‐based practice. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 14(6), 440–446. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12262