Abstract

Background

It is well documented that invasive medical treatment, such as Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant (HSCT), can be stressful and potentially traumatic for children, leading to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) or Post Traumatic Stress Symptoms (PTSS) after treatment. Despite this evidence, little is known about the patterns of stress and trauma that develop throughout the HSCT admission.

Purpose

To examine patterns of toxic stress and trauma that develop throughout the pediatric HSCT admission and understand how music therapists, as members of the interdisciplinary psychosocial care team, may proactively intervene to mitigate the impact of traumatic experiences.

Method

A two-phase retrospective longitudinal multi-case design was used with a combination of time series and template analyses.

Sample

The sample included 14 pediatric patients (aged 0–17) undergoing HSCT at a large pediatric hospital in the Midwestern United States.

Findings

The results were identifiable patterns of toxic stress and trauma and a model of care for music therapy that is responsive to the identified patterns.

Introduction

Background

The lengthy and invasive treatments for pediatric cancer and blood diseases can be traumatic. In a longitudinal study of pediatric Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant (HSCT) survivors, over 80% of children exhibited moderate PTSS at three months post-HSCT.Citation1 Despite the psychological risk, HSCT is still considered the best practice for treating many potentially fatal pediatric cancers and immunological, metabolic, and genetic diseases and disorders.Citation2 While there may be slight variations of the protocol based on various factors, the overarching HSCT protocol is standard across transplant centers.Citation3 This protocol typically involves three stages of treatment. In the first phase, patients receive a preparatory regimen of high-dose chemotherapy to weaken/suppress their existing immune system. This process typically takes seven to ten days. Once the patient’s absolute neutrophil count is zero (among other clinical landmarks), the infusion of donor stem cells (allogeneic transplant), or laboratory-modified own cells (autogenic transplant) occurs. This infusion initiates the rebuilding of the immune system with new stem cells. The process of growing the new immune system takes approximately three weeks. In the posttransplant phase, lasting from a few weeks to months, the patient recovers from the transplant, and their new immune system grows stronger.Citation3 The immediate physical side effects of the HSCT treatment include infection, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, mucositis, loss of appetite, acute pain, anxiety, and mood and sleep disturbances. Significant complications include graft-versus-host disease, secondary tumors, generalized anxiety, chronic pain, graft failure, and disease recurrence or relapse. The HSCT process is also associated with decreased quality of life.Citation4,Citation5 While the complications and side effects of the HSCT process are well known, the patterns of trauma or stress related to treatment have not been reported with the same specificity.

Two theoretical models can potentially explain the consequences of trauma and toxic stress in hospitalized children: The Integrative Trajectory Model of Pediatric Medical Traumatic Stress (ITM-PMTS)Citation6 and the Ecobiodevelopmental Framework.Citation7 The ITM-PMTS delineates pediatric medical trauma and its psychological impact from other forms of trauma and provides a framework for understanding the responses of children and parents. Pediatric Medical Traumatic Stress (PMTS) is the “psychological and physiological responses of children and their families to pain, injury, serious illness, medical procedures, and invasive or frightening treatment experiences.”Citation8 The ITM-PMTS conceptualizes child/family psychological adjustment to PMTS in three phases: peritrauma (when the event is occurring and immediately following), acute medical care (following the event and as the patient/family experience the ongoing demands of hospitalization), and ongoing care or discharge from care (describes long-term persistent PMTS responses).Citation6 The ITM-PMTS considers the uniquely cyclical and ongoing experience of PMTS, as medical care occurs over time with the potential for many potentially traumatic events during treatment.

The Ecobiodevelopmental Framework (EBD) focuses on the neurological effects of toxic stress on children. Toxic stress is the experience of prolonged, intense, or frequent adversity without adequate adult support.Citation9 Toxic stress is differentiated from tolerable and positive stress by the frequency and intensity of the stress and the availability of buffering systems. Toxic stress can disrupt neurological development and cause lifelong medical and mental health issues.Citation9,Citation10 The EBD framework features four “counterbalancing” factors to build resilience and support children to persevere through adversity, including (1) supportive relationships, (2) a sense of self-efficacy and perceived control, (3) adaptive skills and self-regulatory capacities and (4) mobilization of sources of faith, hope, and cultural traditions.Citation11 Taken together, the ITM-PMTS and the EBD provide a solid theoretical basis for both the timing of psychosocial intervention and the formulation of future interventions and intervention foci.

The HSCT experience is inextricably bound to time, with every aspect of the treatment process planned and labeled by day. Within this tightly controlled treatment regimen, the unique lived experience of each patient and family is a complex interaction between persons and context.Citation12 While pediatric psychosocial professionals are well positioned to develop and practice targeted interventions in context and over time, current practice has not considered that a trajectory model of interventions could mitigate the cumulative damage of stress and trauma of the experience.

Purpose/objectives

Music therapy is becoming standard care for children receiving HSCT treatment in the United States.Citation13 Evidence for the effect of music therapy interventions on symptom management and psychosocial needs of children and families during HSCT is available.Citation14,Citation15 However, a foundational understanding of the patterns of trauma and stress for pediatric HSCT families is critical to developing proactive and longitudinal music therapy interventions to mitigate the adverse psychological effects of HSCT. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to (1) identify the patterns of trauma and stress in the pediatric Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant (HSCT) process for patients at one pediatric hospital and (2) develop a model of care for music therapy in response to these patterns.

Method

Design

This study utilized a retrospective longitudinal holistic multi-case design.Citation16 This design allowed the context and temporal structure around the HSCT experience and the complex, lived experience of HSCT phenomena in the clinical and real-world context to remain intact. Electronic Medical Record (EMR) data were used to optimize readily available data and minimize the burden for patients and families.

Setting

This study was conducted on a pediatric HSCT Unit within a large free-standing pediatric hospital in the Mid-Western United States.

Participants

Five cohorts of patients were selected for analysis (n = 14). The first cohort of three cases served as the common case to represent the “typical” experience.Citation16 The inclusion criteria were that the patient:

Was admitted to receive an HSCT from January 2011–December 2019.

Was under the age of 18 at the time of admission.

Experienced at least one HSCT-related complication (e.g., mucositis, engraftment syndrome, GVHD, respiratory issues, infections, and mental status changes).Citation17

Was referred to music therapy upon admission for HSCT or at the start of HSCT treatment (if transferred from another unit or hospital) and received music therapy throughout the HSCT admission.

Had at least one consistent caregiver.

Hospitalization for HSCT lasted a minimum of five weeks.

Patients were not excluded if transferred to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU; as this was common for HSCT patients). Patients were included regardless of diagnosis, gender, primary language, country of origin, cognitive impairments, preparatory regimen, or previous medical experience.

The case selection for the subsequent four cohorts used a theoretical replication model to purposefully include specific theoretical conditions or differing results for an expected reason.Citation16 To increase rigor, theoretical replications allowed for rival explanations from an increased diversity of cases. Therefore, the additional cohorts were: late/delayed music therapy referral/engagement, different music therapists, preschool-aged children, and children under 18 months of age (see for detailed inclusion criteria). A total of 11 cases across the four cohorts were selected to achieve theoretical replication.Citation18

Table 1. Detailed inclusion criteria for theoretical replication cohorts.

Data collection

All time-stamped and dated raw data were retrieved from the hospital’s Electronic Medical Record (EMR) system by a biomedical data analyst with IRB approval (study #2019-0528). This data was then given to the first author as an Excel spreadsheet. Raw data included narrative chart notes written by members of the healthcare team. A waiver of informed consent was granted, as all data was collected from the EMR and deidentified for analysis.

Data analysis

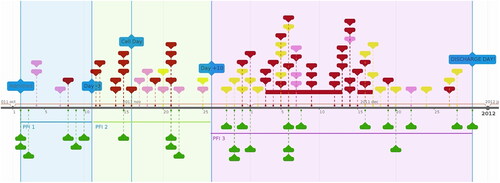

Three overlapping analytic methods, time-series analysis, deductive thematic analysis, and template analysis, were used to identify patterns of stress and trauma and build a model of care based on these patterns. Time-series analysis was used as the first step in the template analysis process to organize the case data chronologically and identify trends and patterns in the data over time using the internet-based timeline software TimeGraphics (https://time.graphics).Citation16,Citation19 Five time series were generated for each case (N = 14). The first time series ordered and coded medical events, and the second and third time series ordered and thematically coded psychosocial support sessions and music therapy sessions. The fourth and fifth time series included deductive thematic analysis to code narrative data using the EBD and ITM-PMTS as the theoretical lenses. See .

Table 2. Defined elements for each time series.

Within each case, the five times series were combined into an integrated timeline producing a graphic, time-ordered representation of the HSCT treatment, psychosocial support sessions, and patterns of traumatic or stressful events (). The integrated timelines for each common case (N = 3) were aggregated to construct the initial template (step four of template analysis). Next, the initial template was interrogated by adding data from four theoretical replication cohorts (N = 11). The case data from the theoretical replication cohorts were first analyzed within case (as with the common case cohort) and then across cohort cases before it was applied to the initial template. This interrogation process sought to reveal weaknesses and confirm aspects of the template. Clarifications and changes were made when the analysis revealed a misalignment between the new case data and the template. The iterative process of template interrogation continued until the researchers gained no further insights from new cases. The researchers then applied the entire data set to the final template to ensure that iterative changes to the model still accommodated the complete data set (More information about template analysis can be found at https://research.hud.ac.uk/research-subjects/human-health/template-analysis/technique/).Citation20

Trustworthiness

The first author was music therapist 1 (see ). Qualitative research often includes the researcher’s perspectives, which are embedded here. Trustworthiness was achieved through data source triangulation (EMR notes were written by many different professionals) and theory triangulation to limit bias in the findings. The first author was responsible for extracting, deidentifying, preliminary analysis, and providing a narrative of these results to the second author for consideration. The two authors engaged in repeated discussions until congruence of interpretation was reached. Because of the exploratory nature of the analysis, no tests of inter-rater reliability were used.Citation16

Table 3. Case demographics.

Findings

Fourteen cases in five cohorts were analyzed (see ). Here we report the time-bound patterns of toxic stress and trauma throughout the pediatric HSCT admission, the themes and patterns related to music therapist intervention, and finally, we integrate the theoretical frameworks to explicate a model for music therapy practice. Results are reported by pseudonym and case number to preserve the humanity of the patients and allow for easy tracking for readers.

Time bound patterns

Across all cases, time and timing emerged within the HSCT experience (here called “time-bound” patterns). Across cases, the medical experience and potential for toxic stress and trauma were delineated into three Phases for Focused Intervention (PFI) (visualized in ).

The first phase of the transplant admission (PFI1) is relatively unremarkable and generally short (consistent for most patients except Aliya (P1), Ashley (P10), and Patrick (P14). It begins at admission and lasts until the preparatory regimen increases symptom burden (around day −4). The next phase (PFI2) begins around day −3 and continues through the first ten days after the transplant (day +10). This phase is marked by a myriad of negative symptoms (fatigue, nausea, vomiting, pain, fevers, mucositis) and high symptom burden (consistent with most patients except Ashley (P10) and Patrick (P14)). The last phase (PFI3), occurring around day +11, has both significant positive gains as well as unpredictability in medical status, decompensation, and sudden onset of new complications from transplant (consistent for most patients except Carter (P5) and Ashley (P10) (no data for Ashley (P10)).

Therapist related themes

Early assessment and introduction of services are important

Patients who received a preadmission or early admission psychosocial assessment had more psychosocial support visits per day (on average) than those with later involvement. Aliya (P1), who had no psychosocial assessment or support services initiated until a week after her admission, had an average of 0.5 visits per day (36 visits over 70-day admission). Carrie (P4) had a preadmission psychosocial assessment and an average of 0.92 visits per day (99 visits over 107-day admission).

For referral-based services like music therapy, the effect of late engagement was more pronounced. The lack of referral or engagement in PFI1 had a detrimental impact on the acceptability of the service once symptom burden increased. For all patients in Cohort 2 (patients Carrie (P4), Carter (P5), Olivia (P6), and Jackie (P9), music therapy services were not introduced or initiated before the onset of intense symptom burden. These patients declined all music therapy attempts during PFI2.

A bridging relationship may be helpful

The high symptom burden during PFI 2 may make accepting new experiences and new people challenging for patients and their families. Regardless of how helpful music therapy interventions could have been, all patients in Cohort 2 declined the service. For Carrier (P4) and Olivia (P6), a trusted healthcare professional incorporated the music therapist into their sessions. This appeared to create a bridge of vicarious acceptability for the patient and potentially lessen the patient and family’s burden of effort to actively engage. For Carrie (P4), the Integrative Care RN included the music therapist to provide live therapeutic music to support massage/mindfulness sessions, leading to the acceptance of music therapy services (independently requested MT visits and participated in sessions) and a decrease in declining sessions when offered (declined one out of 8 sessions, previously declined ¾ of sessions). For Olivia (P6), the physical therapist included the music therapist in the session to support Olivia’s motivation to move by playing novel instruments. This inclusion by the physical therapist led to the acceptance of music therapy services, as evidenced by consistent participation, requesting additional music therapy sessions, and no longer declining sessions.

Preparation for PFI2 & 3 seems to increase the acceptability of MT services

Data for Cohort 4 (different music therapist) showed that patients whose music therapist did not prepare them for how music therapy could be helpful during periods of high symptom burden declined music therapy services during PFI2. Despite music therapy during PFI1, Lily (P7) declined all music therapy session attempts between day −4 and day +33. Music therapy sessions only resumed when Lily began “feeling better,” per the parent report. This experience was also consistent with Jackie’s (P9). For patients Aliya (P1), Bess (P2), Jimmy (P3), Carrie (P4), Henry (P12), and Patrick (P14), the music therapist explained to them or their parents how music therapy might be helpful during PFI2 and PFI3, and all accepted services throughout PFI2 and PFI3 regardless of symptom burden.

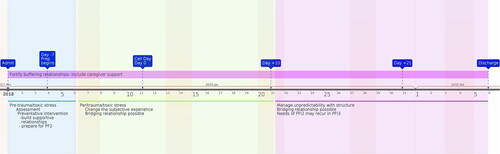

Integrated results

The result of the template analysis is a model which integrates the five timelines (see ) for all 14 patients. This integration demonstrates the interaction between the medical trajectories and psychosocial services and the theoretical rationale for implementing future psychosocial intervention, specifically music therapy. Results are reported by PFI. See for a graphic representation of the integrated model, now referred to as the Music Therapy for Pediatric Medical Trauma Model (MTPedMT).

Figure 2. Music therapy for pediatric medical trauma model.

Blue: PFI1; Lime Green: PFI2; Purple: PFI3.

PFI 1 is characterized by the following themes

Low potential for potentially traumatic events

Of the 14 patients, only two (Aliya (P1) and Ashley (P10), experienced potentially traumatic events between admission and day −4. For both patients, the potentially traumatic events were related to complications from central line placements as part of the preparatory regimen for their HSCT. HSCT is generally a planned procedure, so none of the patients were unexpectedly admitted. Only Aliya (P1) was admitted for her HSCT earlier than expected.

Preventative intervention

With the knowledge that traumatic events are likely to occur throughout the HSCT process, this first phase may be conceptualized through the EBD lens as pre-trauma (the time leading up to periods with high potential for trauma/toxic stress). Preventative interventions during PFI1 served to build supportive relationships (P1, P2, P3, P7, P12, P14), self-efficacy (P3, P9), promote adaptive capacities (P3, P14), and mobilize sources of hope and faith (P9) (factors of resilience in the EBD framework).

PFI 2 is characterized by the following themes

Changing the subjective experience

The ITM-PMTS model emphasizes changing subjective experience as the primary focus of psychosocial care in the peri-trauma period. The analysis confirmed managing pain and anxiety as the most common goal in PFI2. Interventions that changed the subjective experience varied based on the child’s age and development. Children under 5 (Henry (P12), Maggie (P13), Patrick (P14)) were more likely to experience comfort through security, attachment, and active engagement. School-aged patients (Aliya (P1), Carter (P5), Olivia (P6), and Lily (P7)) utilized alternative focus, active engagement (e.g. instrument play, songwriting), and music-assisted relaxation. Given their cognitive development, adolescents (Jimmy (P3) and Carrie (P4)) experienced comfort from guided imagery, breath work, or music-assisted relaxation and used sleeping as a coping strategy.

PFI 3 is characterized by the following themes

Manage unpredictability through structure

The defining characteristic of PFI3 is the unpredictability of the medical trajectory, vacillating between progress in healing and recovery and additional complications, new symptoms, and continued medical challenges. Analysis showed that music therapy interventions in this period were more structured and predictable. These included therapeutic music lessons (Aliya (P1), Jimmy (P3), Jackie (P9), structured songwriting interventions (Olivia (P6), Lily (P7), Ashley, (P10), music games (Carter (P5), Olivia (P6), Lily (P7), Madison (P11), and singing/playing familiar songs (Aliya (P1), Carrie (P4), Olivia (P6), Jackie (P9), Henry (P12), Maggie (P13).

High potential for accumulation of stress to toxic levels

After PFI2, with high symptom burden and a high potential for potentially traumatic events, PFI3 had a high potential for stress levels to become toxic, especially where analysis indicated no “relief” between negative events or potentially traumatic events. This was the experience for patients Aliya (P1), Bess (P2), Carrie (P4), Olivia (P6), James (P8), and Henry (P12).

Needs of PFI 2 may recur in PFI3

Once a patient transitioned to PFI3, there was the potential to have another period of high and sustained symptom burden, which required the therapist to shift focus from managing unpredictability to once again focusing on changing the subjective experience (PFI 2). This was true for Carrie (patient 4) and Henry (patient 12), who had long and highly unpredictable PFI3s.

Across all phases, fortify buffering relationships

Especially for patients under 5, the case data indicated that the parent/child relationship is central throughout the HSCT process. For all Cohort 4 and 5 (patients under five years old), the parent was the primary means of buffering against traumatic experiences (consistent with the EBD framework). While this was most pronounced in younger patients, it was still present in older patients. For example, James (7 years old) would not let his mother leave when he was experiencing high levels of pain. What is also consistent in the data (patients Bess (P2), Carrie (P4), Lily (P7), James (P8), Madison (P11), Henry (P12), Patrick (P14), is that parents also need psychosocial support.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to identify patterns of trauma and stress during the pediatric HSCT process and develop a model of music therapy intervention in response to the identified patterns. While it is well established that invasive medical treatment like HSCT has the potential to cause future PTSD and PTSS, little research has been conducted to establish patterns of stress and trauma on which psychosocial care providers may intervene during the HSCT admission. The predictable patterns of potentially traumatic events and toxic stress identified in this study demonstrates the potential to proactively intervene to mitigate the impact of the event(s). Further, intentional intervention may alter the patient’s interpretation of an event or series of events as traumatic and interrupt potential periods of toxic stress.

Music therapists and psychosocial support disciplines provide an essential balancing component of treatment. In an ideal circumstance, psychosocial support would balance the potential trauma and stress of the predictable treatment pathway. But even in a less-than-ideal reality, the MTPedMT () offers a model of care in which service providers can prospectively plan the implementation of care that is responsive to the evolving needs and realities of HSCT patients.

The construct of counterbalancing trauma and toxic stress is apparent in the integrated timelines of the patients whose cases are presented in this study, particularly for Jimmy (P3, see supplemental file). Jimmy had periods of potential toxic stress and potentially traumatic events, all appearing visually balanced with extensive psychosocial support. In the medical model of treatment, psychosocial services are often labeled as “ancillary,” relegated to a subordinate role supporting medical treatment as the primary pathway. Jimmy’s case suggests that when psychosocial support is well balanced with potentially traumatic medical treatments, the outcome is a lower subjectively traumatic HSCT experience for our patients. Further research is needed to examine the outcome of coordinated, balanced treatment.

Implications

The MTPedMT offers a new way for pediatric music therapists and psychosocial care providers to conceptualize their work as actively disrupting patterns of toxic stress and mitigating the evident trauma in the HSCT setting. This encompasses and elevates pediatric music therapy practice focused on outcomes such as patient anxiety,Citation21,Citation22 pain,Citation15,Citation23 coping,Citation24,Citation25 mood,Citation15 physiologic measures (e.g. heart rate),Citation26 and parent-reported distress.Citation27 These outcomes can be considered part of trauma and toxic stress mitigation. In their most recent studies, Uggla et al. make a case for this emerging trajectory for research and practice focused on music-based intervention to decrease the activation of the stress response systems for pediatric HSCT patients.Citation15,Citation26 The MTPedMT represents the continuation of this trajectory as the next step in the understanding and practice of music therapy for pediatric patients.

While music therapy was the discipline of focus in this study, the model has clear implications for structuring a coordinated interdisciplinary approach to holistic psychosocial care. This model aims to target patients’ and their families’ specific needs and values while harnessing the unique contribution of professionals’ services during various PFIs. It is well documented that teamwork within clinical care teams and coordinated interdisciplinary care have improved outcomes.Citation28

Each PFI has an opportunity for interdisciplinary collaboration and relational coordination. Gittell et al. define relational coordination as encompassing four communication dimensions (frequent, timely, accurate, and problem-solving communication) and three relationship dimensions (shared goals, shared knowledge, and mutual respect)”.Citation28 In PFI 1, the preadmission assessment, often completed by psychologists and social workers, offers foundational information for all disciplines.Citation29 Consistent pre-assessment has the potential to ensure swift and appropriate referrals and to provide critical opportunities in the brief PFI 1. In PFI 2, a coordinated interdisciplinary focus on changing the subjective experience of burden symptoms such as pain and anxiety management could be optimized by acknowledging how intense fatigue and symptom burden minimize patients’ and caregivers’ capacity to engage in psychosocial services. Being intentional in interdisciplinary bridging relationships could reduce the burden of effort or decrease the energy required for patients and families to tolerate a new experience during the highest symptom burden. In PFI 3, all disciplines could employ strategies to provide structure to manage unpredictability. Interdisciplinary team structure through coordinated care and scheduling could encourage wider-scale stability for patients.

Limitations

This study is a theoretically based multi-case study and therefore has notable limitations. While generated through rigorous interrogation of cases, the MTPedMT is based on 14 cases and therefore has apparent limitations for generalization. The EMR data provides the medical professionals’ perspectives on the patient’s experience but does not provide the perspectives of the patient and family. Trauma is a subjective experience, and without the first-hand perspective of the patients and families, the case study remains a partial representation. Future research should include the patient/parent perspective collected through quantitative and qualitative methods.

EMR data presents its own bias and limitations. First, only objective observations are reported in EMR notes. This means more subjective observations pertaining to evolving therapeutic relationships are not documented. Second, there can be gaps in EMR data due to human error. A clinician could forget to chart an interaction or unintentionally leave out information. EMR data is reliable by design, but it does have limitations. Future research should use rigorous prospective methods of data collection to minimize errors of omission and bias. Additionally, further studies utilizing mixed methods and qualitative research may provide more insight into subjective experiences of patients, families, and staff that were not able to be captured in this study.

Conclusion

Case study data for the HSCT admission of 14 pediatric cases revealed three primary phases of focused intervention (PFI) aligned with patterns of toxic stress and trauma, as conceptualized through Shonkoff et al.’s Ecobiodevelopmental Framework and Price et al.’s Integrative Trajectory Model of Pediatric Medical Traumatic Stress (ITM-PMTS).Citation6,Citation7 Associated with these PFIs were the clear roles, functions, and contributions of music therapy interventions. Together, they form the Music Therapy for Pediatric Medical Trauma (MTPedMT) model.

The MTPedMT provides a model to structure music therapy interventions throughout a patient’s HSCT treatment with the intention of mitigating the impending trauma and toxic stress. While music therapy is the discipline of focus for the present study, the insights of the MTPedMT may be applied across the interdisciplinary care team. Comprehensive interdisciplinary psychosocial support is necessary to counterbalance the arduous, stressful, and potentially traumatic experience of receiving an HSCT for children and their families. As survival rates continue to rise, all HSCT care providers must consider the importance of buffering and trauma-mitigating interventions so these children may go on to lead healthy, resilient lives.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (3.6 MB)Acknowledgments

This research was completed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the first author’s PhD at Temple University. The authors acknowledge Dr. Sheri Robb, PhD, MT-BC, and Dr. Ahna Pai, PhD, for their support and mentorship.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly, so due to the sensitive nature of the research supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Stuber ML, Nader K, Yasuda P, et al. Stress responses after pediatric bone marrow transplantation: preliminary results of a prospective longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30(6):952–957. doi:10.1097/00004583-199111000-00013

- D’Souza A, Lee S, Zhu X, et al. Current use and trends in hematopoietic cell transplantation in the United States. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23(9):1417–1421. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.05.035

- Yesilipek MA. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children. Turk Arch Ped. 2014;49(2):91–98. doi:10.5152/tpa.2014.2010

- Bevans MF, Mitchell SA, Marden S. The symptom experience in the first 100 days following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(11):1243–1254. doi:10.1007/s00520-008-0420-6

- Plummer K, McCarthy M, McKenzie I, Newall F, Manias E. Experiences of pain in hospitalized children during hematopoietic stem cell transplantation therapy. Qual Health Res. 2021;31(12):2247–2259. doi:10.1177/10497323211034161

- Price J, Kassam-Adams N, Alderfer MA, et al. Systematic review: a reevaluation and update of the integrative (trajectory) model of pediatric medical traumatic stress. J Pediatr Psychol. 2016;41(1)::86–97. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsv074

- Shonkoff JP, Garner AS. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e232–e246. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2663

- Network NCTS. Medical Trauma November 3, 2018. Available from: www.nctsn.org/what-is-child-trauma/medical-trauma.

- Bates RA, Militello L, Barker E, et al. Early childhood stress responses to psychosocial stressors: the state of the science. Dev Psychobiol. 2022;64(7):e22320.

- Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(8):e356–e366. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4

- Child N. Excessive Stress Disrupts the Architecture of the Developing Brain: Working Paper 3. Updated Edition. 2014.

- Greenhalgh T, Papoutsi C. Studying complexity in health services research: desperately seeking an overdue paradigm shift. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):95. doi:10.1186/s12916-018-1089-4

- Knott D, Biard M, Nelson KE, et al. A survey of music therapists working in pediatric medical settings in the United States. J Music Ther. 2020;57(1):34–65. doi:10.1093/jmt/thz019

- Robb SL, Hanson-Abromeit D. A review of supportive care interventions to manage distress in young children with cancer and parents. Cancer Nurs. 2014;37(4):E1–26. doi:10.1097/NCC.0000000000000095

- Uggla L, Bonde L-O, Hammar U, et al. Music therapy supported the health-related quality of life for children undergoing haematopoietic stem cell transplants. Acta Paediatr. 2018;107(11):1986–1994. doi:10.1111/apa.14515

- Yin RK. Study Research and Applications: Designs and Methods, 6th ed. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2018.

- Carreras E. Early complications after HSCT. In The EBMT Handbook. France: European School of Haematology; 2012.

- Atilola O, Stevanovic D, Moreira P, et al. External locus-of-control partially mediates the association between cumulative trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress symptoms among adolescents from diverse background. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2021;34(6):626–644. doi:10.1080/10615806.2021.1891224

- Mustfinn E. TimeGraphics[computer software]. Retrieved from: https://time.graphics/

- King NJ. Template Analysis for Business and Management Students. London: SAGE; 2017.

- Saghaei SMA. The effectiveness of music therapy on anxiety sensitivity and self-efficacy in adolescents with leukemia in Tehran, Iran. International Journal of Body, Mind, and Culture. 2019;6(2):163.

- Giordano F, Zanchi B, De Leonardis F, et al. The influence of music therapy on preoperative anxiety in pediatric oncology patients undergoing invasive procedures. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2020;68:101649. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2020.101649

- Nguyen TN, et al. Music therapy to reduce pain and anxiety in children with cancer undergoing lumbar puncture: a randomized clinical trial. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2010;27(3):146–155.

- Barry P, O’Callaghan C, Wheeler G, et al. Music therapy CD creation for initial pediatric radiation therapy: a mixed methods analysis. J Music Ther. 2010;47(3):233–263. doi:10.1093/jmt/47.3.233

- Robb SL, Burns DS, Stegenga KA, et al. Randomized clinical trial of therapeutic music video intervention for resilience outcomes in adolescents/young adults undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer. 2014;120(6):909–917. doi:10.1002/cncr.28355

- Uggla L, Bonde LO, Svahn BM, et al. Music therapy can lower the heart rates of severely sick children. Acta Paediatr. 2016;105(10):1225–1230. doi:10.1111/apa.13452

- Ortiz GS, O’Connor T, Carey J, et al. Impact of a child life and music therapy procedural support intervention on parental perception of their child’s distress during intravenous placement. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019;35(7):498–505. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000001065

- Gittell JH, Godfrey M, Thistlethwaite J. Interprofessional collaborative practice and relational coordination: improving healthcare through relationships. J Interprof Care. 2013;27(3):210–213. doi:10.3109/13561820.2012.730564

- Pai ALH, Swain AM, Chen FF, et al. Screening for family psychosocial risk in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with the psychosocial assessment tool. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25(7):1374–1381. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.03.012