ABSTRACT

In this article I offer some existential-phenomenological reflections on the interrelationships among the forms of love, loss, finitude, and the human ways of being.

Each friend represents a world in us, a world possibly not born until they arrive, and it is only by this meeting that a new world is born.

– Anais Nin

Authentic being-toward-death

Heidegger (Citation1927) contends that by authentically (ownedly) comporting itself toward death, Dasein (the human being) recognizes “in this distinctive possibility of its own self [that] it has been wrenched away from the ‘they’ [das Man, conventional everyday interpretedness]” (p. 307). Furthermore, he argues that this “ownmost possibility is non-relational [in that] death lays claim to [Dasein] as an individual Dasein” (p. 308), nullifying its everyday relations with others. This is because in everyday relating governed by das Man – fulfilling conventionally defined role requirements, for example, – any Dasein can substitute for any other. One’s death, in contrast, is unsharable: “No one can take the Other’s dying away from him … . By its very essence, death is in each case mine” (p. 284).

Other existential philosophers object to Heidegger’s claim about the non-relational character of death. Vogel (Citation1994), for example, suggests that just as finitude is fundamental to our existential constitution, so too is it constitutive of our existence that we meet each other as “brothers and sisters in the same dark night” (p. 97), deeply connected with one another in virtue of our common finitude. Critchley (Citation2002) points the way toward a second, and to my mind essential, dimension of the relationality of finitude:

“I would want to oppose [Heidegger’s claim about the non-relationality of death] with the thought of the fundamentally relational character of finitude, namely that death is first and foremost experienced as a relation to the death or dying of the other and others, in Being-with the dying in a caring way, and in grieving after they are dead … . With all the terrible lucidity of grief, one watches the person one loves – parent, partner or child – die and become a lifeless material thing. That is, there is a thing – a corpse – at the heart of the experience of finitude. This is why I mourn … . [D]eath and finitude are fundamentally relational, … constituted in a relation to a lifeless material thing whom I love and this thing casts a long mournful shadow across the self.” (pp. 169–170)

In my own work (Stolorow, Citation2011), I claim that authentic Being-toward-death entails owning up not only to one’s own finitude, but also to the finitude of all those we love. Hence, I contend, authentic Being-toward-death always includes Being-toward-loss as a central constituent. Just as, existentially, we are “always dying already” (Heidegger, Citation1927, p. 298), so too are we always already grieving. Death and loss are existentially equiprimordial. Existential anxiety anticipates both death and loss.

Support for my claim about the equiprimordiality of death and loss can be found in some works by Derrida. In Politics of Friendship (Derrida, Citation1997), for example, he contends that the “law of friendship” dictates that every friendship is structured from its beginning, a priori, by the possibility that one of the two friends will die first and that the surviving friend will be left to mourn. In Memoirs for Paul de Man (Citation1989), he similarly claims that there is “no friendship without this knowledge of finitude” (p. 28). Finitude and the possibility of mourning are constitutive of every friendship. Derrida (Citation2001) makes this existential claim evocatively and movingly in The Work of Mourning.

“To have a friend, to look at him, to follow him with your eyes, to admire him in friendship, is to know in a more intense way, already injured, always insistent, and more and more unforgettable, that one of the two of you will inevitably see the other die. One of us, each says to himself, the day will come when one of the two of us will see himself no longer seeing the other … . That is the … infinitely small tear, which the mourning of friends passes through and endures even before death … .” (Derrida, Citation2001, p. 107)

It might be objected that Being-toward-loss cannot be a form of Being-toward-death because, whereas the uttermost possibility of death is “the possibility of the impossibility of any existence at all” (Heidegger, Citation1927, p. 307), loss does not nullify the entirety of one’s possibilities for Being. Yet, I would counter, in loss as possibility, all possibilities for Being in relation to the lost loved one are extinguished. Thus, Being-toward-loss is also a Being-toward-the-death of a part of one’s Being-in-the-world – toward a form of existential death. Traumatic loss shatters one’s emotional world, and, insofar as one dwells in the region of such loss, one feels eradicated. Derrida (Citation2001), once again, captures this claim poignantly and poetically:

“[T]he world [is] suspended by some unique tear … reflecting disappearance itself: the world, the whole world, the world itself, for death takes from us not only some particular life within the world, some moment that belongs to us, but, each time, without limit, someone through whom the world, and first of all our own world, will have opened up … .” (Derrida, Citation2001, p. 107)

The loss of a beloved is the loss of a world.

Varieties of loss experience

In my discussion so far I have intermingled and not sharply differentiated the four forms of love identified by the ancient Greeks: Philia (friendship), Eros (romantic, sexual love), Storge (parental affection), and Agape (love of humanity, of our fellow human beings). In my view, these forms of love are most often complexly intermingled. In the richest and deepest romantic relationships, for example, we may experience a lover fluidly and flexibly as an object of our erotic desire and as our best friend, as our parent and as our child, as our brother or sister and as our soul mate, and, in existential kinship, as a fellow human being. The richer and more multidimensional a love relationship, the more traumatically world-shattering will be its loss.

More generally, the nature of a loss experience will depend complexly on the forms or dimensions of love that had constituted the lost relationship. For example, relationships differ according to the extent to which self or other – two experiential foci within the unitary structure Being-in-the world – occupies the emotional foreground. The experience of the loss of someone who primarily had been loved narcissistically, serving as support for the survivor’s sense of selfhood, will differ from the loss of someone whose alterity had been recognized and deeply treasured. In the former case one’s sense of selfhood will be weakened, whereas in the latter one’s world will be emptied out and impoverished.

There is no loss more horrific than the death of a beloved young child. What is not generally recognized, however, is that loss is experienced by a loving parent throughout the course of his or her child’s development. At each newly emerging stage, the parent experiences both joy in the child’s developmental achievement and grief over the loss of what is being left behind. My poem, “Emily Running” (Stolorow, Citation2003), captures this phenomenon:

My favorite time of day

is walking Emily to school in the morning.

We kiss as we leave our driveway

so other kids won’t see us.

If I’m lucky, we have a second kiss,

furtively, at the school-yard’s edge.

My insides beam as she turns from me

and runs to the building where her class is held,

blonde hair flowing,

backpack flapping,

my splendid, precious third-grader.

Slowly, almost imperceptibly,

a cloud begins to darken

my wide internal smile –

not grief, exactly, but a poignant sadness –

as her running points me back

to other partings

and toward other turnings

further down the road.

Emily died of a tragic accident on her twentieth birthday. Loss – especially traumatic or tragic loss – creates a dark region in our world that will always be there. A wave of profound sadness descends upon us whenever we step into that region of loss. There we are left adrift in a world hollowed out, emptied of light. It is a bleak region that can never be completely eradicated or cordoned off. The injunction to “let it go and move on” is thus an absurdity. There will always be “portkeys” back into the darkness – the dark realm in which we need to be emotionally held so that the loss can be better borne and integrated. Edna St. Vincent Millay captures my own experience of such loss grippingly:

“Where you used to be, there is a hole in the world, which I find myself constantly walking around in the daytime, and falling in at night. I miss you like hell.”

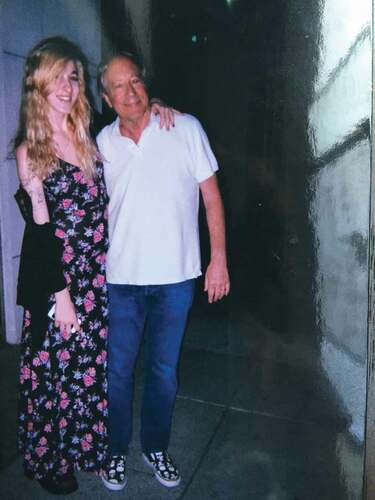

There is a lovely photograph of Emily and me on our way to dinner at Emily’s favorite restaurant (see ). Every morning since she died I look at this photo and have a tearful conversation with her. “I love you Daddy,” Emily says, placing her arm lovingly around my shoulder, and I reply, “I love you so much Emmy; I miss you so much.” For a few brief moments I feel that my precious daughter is here with me again.

In his classic essay, “Mourning and Melancholia,” Freud (Citation1917) claimed famously, and wrongly, that memories of a deceased loved one help a bereaved person gradually let go of the lost connection. On the contrary, such memories serve to solidify that connection and keep it alive. This is especially true when the memories are concretized in material objects such as photographs and works of art. An agonizing dialectic of presence and absence.

Love and finitude

There is a certain thinness in Heidegger’s (Citation1927) conception of “Being-with” (Mitsein), his term for the existential structure that underpins the capacity for relationality. Authentic Being-with is largely restricted in Heidegger’s philosophy to a form of “solicitude” that welcomes and encourages the other’s individualized selfhood, by liberating the other for his or her own authentic possibilities. At first glance, such an account of authentic relationality would not seem to include the treasuring of a particular other, as would be disclosed in the mood of love. Indeed, I cannot recall ever having encountered the word love in the text of Being and Time, although references to other ontically experienced, disclosive emotional states – such as fear, anxiety, homesickness, boredom, and melancholy – are scattered throughout this book and others written during the same period. Authentic selfhood for Heidegger seems, in this context, to be found in the non-relationality of death, not in the love of another. Within such a limited view of relationality, traumatic loss could only be a loss of the other’s selfhood-liberating function, not a loss of a deeply treasured other.

I now wish to show how authentic solicitude entails something like friendship or love, even though Heidegger himself did not explicate such entailment. I begin with his distinction between the two modes of solicitude – inauthentic and authentic. With regard to solicitude in the inauthentic mode:

“It can, as it were, take away ‘care’ [our existentially constitutive engagement with ourselves and our world] from the Other and put itself in his position in concern; it can leap in for him. This kind of solicitude takes over for the Other that with which he is to concern himself … . In such [inauthentic] solicitude the Other can become one who is dominated and dependent … .” (Heidegger, Citation1927, p. 158)

“In contrast to this, there is also the possibility of a kind of [authentic] solicitude which does not so much leap in for the Other as leap ahead of him in his existentiell potentiality-for-Being, not in order to take away his ‘care’ but rather to give it back to him authentically as such for the first time. This kind of solicitude pertains essentially to authentic care – that is, to the [authentic] existence of the Other, not to a “what” with which he is concerned; it helps the Other … to become free for [his authentic care] … . [Authentic solicitude] frees the Other in his freedom for himself … . [It] leaps forth and liberates.” (pp. 158–159)

Authentic solicitude, in Heidegger’s account, frees the other for his or her authentic care – that is, to exist authentically, for the sake of his or her ownmost possibilities of Being. But recall that, for Heidegger, being free for one’s ownmost possibilities also always means being free for one’s uttermost possibility – the possibility of death (to which I would add the possibility of loss). Heidegger does not explain how authentic solicitude accomplishes this emancipation.

In Heidegger’s account of authentic existing, authentic Being-toward-death is disclosed in the mood of anxiety (Angst). How can we free the other for a readiness to experience this disclosive anxiety? A painful emotional state – even a traumatized state – can become more bearable and more integrated if it finds a context of emotional understanding, a “relational home,” in which it can dwell and be held. Thus, if we are to leap ahead of the other, freeing him or her for an authentic Being-toward-death and a readiness for the anxiety that discloses it, we must Be-with – that is, understandingly attune to – the other’s existential anxiety and other painful emotional states disclosive of his or her finitude, thereby providing these feelings with a relational home in which they can be held, so that he or she can seize upon his or her ownmost possibilities in the face of them. Authentic solicitude can indeed be shown to entail one of the constitutive dimensions of deep human bonding, in which we value the alterity of the other as it is manifested in his or her own distinctive affectivity.

Recently, I have been moving toward a more active, relationally engaged form of therapeutic comportment that I call emotional dwelling (Stolorow, Citation2014). In dwelling, one does not merely seek to understand the other’s emotional pain from the other’s perspective. One does that, but much more. In dwelling, one leans into the other’s emotional pain and participates in it, perhaps with aid of one’s own analogous experiences of pain. I have found that this active, engaged, participatory comportment – a form of authentic solicitude – is especially important in the therapeutic approach to emotional trauma (Stolorow, Citation2007, Citation2011). The language that one uses to address another’s experience of emotional trauma meets the trauma head-on, articulating the unbearable and the unendurable, saying the unsayable, unmitigated by any efforts to soothe, comfort, encourage, or reassure – such efforts invariably being experienced by the other as a shunning or turning away from his or her traumatized state.

If we are to be an understanding relational home for a traumatized person, we must tolerate, even draw upon, our own existential vulnerabilities so that we can dwell unflinchingly with his or her unbearable and recurring emotional pain. When we dwell with others’ unendurable pain, their shattered emotional worlds are enabled to shine with a kind of sacredness that calls forth an understanding and caring engagement within which traumatized states can be gradually transformed into bearable painful feelings. Emotional pain and existential vulnerability that find a hospitable relational home can be seamlessly and constitutively integrated into whom one experiences oneself as being.

Heidegger does not offer a comportment for authentic solicitude. After all, he was not a psychoanalytic therapist. Later in his career he did give a group of psychiatrists (Heidegger, Citation1987) some “supervision” on removing Cartesian presuppositions from their clinical work.

In his later work, Heidegger is said to have moved away from phenomenology and toward a metaphysical realism. It is probably more accurate to say that he moved toward a complex amalgam of the two. This characterization certainly holds for his lecture “Building dwelling thinking” (Heidegger, Citation1951), which gives important glimpses into the ontological significance of the earth. Indeed, Heidegger claims in this essay that the fundamental character of the human kind of being (existence) is dwelling. Such dwelling requires a space, a location, a home; and that home is the earth. In this vision, the earth provides grounding for the human kind of being. For humans, to be is to dwell on earth, and to dwell requires that they safeguard and preserve the earth that grounds them. Heidegger uses several interrelated phrases to characterize the comportment of dwelling on earth: To dwell there is to cherish, to protect, to preserve, to care for, to nourish, to nurture, to nurse, to keep safe, to spare, to save. “Mortals dwell in that they save the earth” (Heidegger, Citation1951, p. 148). What is most noteworthy to me is that all of these manifestations of dwelling entail recognizing and providing a relational home for earth’s vulnerability, rather than evasively turning away. They entail renunciation of evasive metaphysical illusions of earth’s everlasting invincibility.

I suggest that it is a similar form of dwelling – an emotional dwelling with one another – that lies at the heart of authentic solicitude. It is in dwelling with another’s painful emotional experience, thereby providing a home and a grounding for the other’s existential vulnerabilities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Robert D. Stolorow

Robert D. Stolorow, Ph.D., is a Founding Faculty Member at the Institute of Contemporary Psychoanalysis, Los Angeles, and at the Institute for the Psychoanalytic Study of Subjectivity, New York. Absorbed for more than five decades in the project of rethinking psychoanalysis as a form of phenomenological inquiry, he is the author of World, Affectivity, Trauma: Heidegger and Post-Cartesian Psychoanalysis (Routledge, 2011) and Trauma and Human Existence: Autobiographical, Psychoanalytic, and Philosophical Reflections (Routledge, 2007), and coauthor of nine other books, including most recently, The Power of Phenomenology (Routledge, 2018). He received his Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology from Harvard in 1970 and his Ph.D. in Philosophy from the University of California at Riverside in 2007.

References

- Critchley, S. (2002). Enigma variations: An interpretation of Heidegger’s Sein und Zeit. Ratio, 15(2), 154–175. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9329.00182

- Derrida, J. (1989). Memoirs for Paul de Man (rev ed. Translated by C. Lindsay, J. Culler, E. Cadava, & P. Kamuf). Columbia University Press.

- Derrida, J. (1997). Politics of friendship ( Translated by G. Collins). Verso.

- Derrida, J. (2001). The work of mourning (Eds. Brault, P.-A. & Naas, M.). University of Chicago Press.

- Freud, S. (1917). Mourning and melancholia. Standard Edition, Vol. 14, pp. 237–258. Hogarth Press.

- Heidegger, M. (1927). Being and time ( Translated by J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson). Harper & Row, 1962.

- Heidegger, M. (1951). Building dwelling thinking. In A. Hofstadter (Ed.), Poetry, language, thought ( Translated by A. Hofstadter; pp. 141–159). Perennial, 2001.

- Heidegger, M. (1987). Zollikon seminars (Ed. Boss, M.). Northwestern University Press, 2001.

- Stolorow, R. D. (2003). Emily running. Constructivism in the Human Sciences, 8(2), 227.

- Stolorow, R. D. (2007). Trauma and human existence: Autobiographical, psychoanalytic, and philosophical reflections. Routledge.

- Stolorow, R. D. (2011). World, affectivity, trauma: Heidegger and post-cartesian psychoanalysis. Routledge.

- Stolorow, R. D. (2014). Undergoing the situation: Emotional dwelling is more than empathic understanding. International Journal of Psychoanalytic Self Psychology, 9(1), 80–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15551024.2014.857750

- Vogel, L. (1994). The fragile “we”: Ethical implications of Heidegger’s being and time. Northwestern University Press.