?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Based on a recently published historical crime database that shows an unequivocal reduction of homicides in Mexico from the 1950s up until 2005, this paper aims to examine the effect of development policies on homicide reduction in 20th century Mexico. This research presents a panel regression of homicide rates in all 32 Mexican states from 1950 to 2005. Our research shows that the increase in schooling years in Mexico is correlated with the decline in homicide rates. This decline happened despite inverse pressure from social disorganisation caused by unequal economic growth and youth bulges during the period examined. Consequently, the paper shows that sustained development policies can be a pacifying mechanism in a country that has experienced accelerated urban growth and other structural problems associated with crime since the beginning of the century.

Introduction

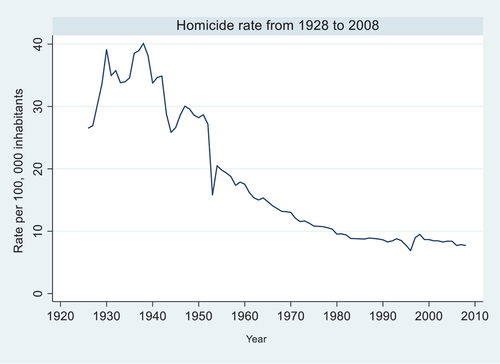

Mexico experienced a sustained and unambiguous decline in homicide rates from 1928 to 2006. Even though this is one of the most significant developments in Mexican history, it might come as a surprise for some researchers. Contemporary observers of Mexican politics are familiar with the extraordinary levels of violence that the country has suffered from since 2006 (see and Aburto et al. Citation2016; Espinosa and Rubin Citation2015; Merino Citation2011; Osorio Citation2015; Calderón et al. Citation2015; Phillips Citation2015). However, in this paper, we sustain that the reduction of homicides experienced by Mexico over most of the 20th century is a process that deserves much more attention because it resonates with a field of studies about violence decline in Asia and Europe and can open new understanding for Latin America.

While the dynamics of violence from 2006 to date have received wide scholarly attention, researchers have neglected to study the remarkable decline in homicides in Mexico between 1928 and 2006. In other words, while the efforts to understand the current dynamics of violence have been massive, the efforts to comprehend the country’s pacification process experienced after the violent years of the Mexican Revolution (ca. 1910–1920) into the beginning of the 21st century have been relatively scarce.

This paper aims to explain why homicide rates declined steadily during the second half of the 20th century in Mexico. We have the intention to show the positive effects of development policies on the scale and pace of decreasing homicide rates in Mexico between 1950 and 2005. A significant cause was the increase in schooling over this period, which positively affected the decline in homicide rates. To show evidence for this, we use a recently published historical database on crime in Mexico (Piccato, Hidalgo, and Lajous Citation2017) and present a panel regression of homicide rates in all 32 Mexican states from 1950 to 2005.

We divide the paper as follows: drawing on Norbert Elias’ work, the first section reviews the literature on processes of violence reduction from a longue durée perspective and the main explanations that the literature on violence has identified. Complementary to Elias’ thesis, we argue that central authority push a decline in homicide rates and increase infrastructural power, such as essential public services like education. The second section presents the database on historical crime trends in Mexico prepared by Piccato, Hidalgo, and Lajous (Citation2017) and explains how this paper uses the database. The third section presents the results, discusses the implications of our findings, and addresses the need for a new research programme to study historical crime trends in Mexico.

Literature review

Homicide reduction in Mexico: A longue durée perspective

By analysing the decline in homicides in Mexico over more than 50 years, we aim to contribute to the scholarship interested in ‘extending the long-term study of the incidence and patterns of violence’ to Latin America (Johnson, Salvatore, and Spierenburg Citation2013, 1). Europe has been at the centre of the effort to understand the rise and fall of long-term violence processes. This research has arisen due to the relatively good maintenance of many local archives in Western Europe. Historians have been able to find sufficient data to estimate aggregated homicides from the Middle Ages onwards. Regrettably, the primary sources for exploring these issues in Latin America are relatively scarce. However, some research worth mentioning on violence in Latin America during the colonial era has been published (Johnson, Salvatore, y Spierenburg Citation2012; Gabbert Citation2012; Pennock Citation2012).

In the last decade, some additional advances have been made in this direction, including a Special Issue of the Bulletin of Latin America Research dedicated solely to exploring the patterns of violence reduction in Latin America (Johnson, Salvatore, and Spierenburg Citation2013). Regrettably, many published works still suffer from adequate empirical data and have avoided statistical methods. Our paper presents an effort to narrow the gap between the theoretical discussion on the long-term study of violence patterns and statistical analysis for their comprehension.

The dispute on causal mechanisms prevails. A prevalent matter of concern in the available literature is the methodology for counting homicides in premodern records. However, most crime and violence historians agree that lethal violence outside of an armed conflict has declined over the last centuries in most world regions (Gurr Citation1981; Eisner Citation2003). Furthermore, in the 20th century, violence (usually measured through homicide rates) has declined in Europe, Asia, and likely other regions (see Eisner Citation2001; Dai Citation2013; Johnson Citation2008; Johnson and Monkkonen Citation1996). While there is little doubt about the general trend, it is also widely agreed that the process has been neither homogeneous nor unidirectional. Furthermore, not all regions have followed the same path. In some contexts, rapid social and political changes have produced countertrends.

Norbert Elias’ (Citation1982) work is the natural starting point for explaining the long-term decline in homicides in Western Europe. In his famed book The Civilising Process, Elias argues that the centralisation of power in the 16th and 17th Centuries in Western Europe led to various processes: less intra-state violence, increasing social cooperation, chains of mutual dependence and decreasing impulsivity. At the centre of his explanation are the increasing levels of self-control in European societies, the building of the central states and the gradual monopolisation of violence.

In line with Elias’ work, Manuel Eisner (Citation2003) has argued that the strengthening of state control, the diffusion of institutional and cultural controls such as religion and schooling, and the decline of honour, among other variables, have played significant roles in the process. Eisner has posed that, for example, in Sweden, the decline in homicides in the first half of the 18th century appears to be related to the ‘triumph of monarchic absolutism and intensified centralised bureaucratic state control structures.’ Similarly, the decline in homicides in Italy from the 1870s onwards ‘corresponds with the triumph of the nation-state and the withering away of local powers’ (Eisner Citation2003, 630). There are similar explanations regarding the long-term process of violence decline in Finland (Ylikangas et al. Citation2001), the Netherlands (Spierenburg Citation1996), different cities in the United Kingdom (for example, Cockburn Citation1991) and other European societies (Gurr Citation1981).

To what extent is it possible to extrapolate the findings and theories of Gurr, Eisner and others for Latin America and the rest of the Global South? Some historians had pointed out that the Latin American period that best correlates with the European monopolisation of violence by absolutist monarchs would be during the 19th century when most Latin American countries became independent. However, as Salvatore has argued, ‘the decolonisation of Hispanic America produced not unity and centralisation but political fragmentation’ (Salvatore Citation2013, 257). Indeed, viceroyalties’ division into different states ‘fragmented the polities even further into autonomies’ (Salvatore Citation2013, 257). With a few exceptions (for example, Chile), national unification processes remained highly contested, with more setbacks than advances over the century (Centeno and Ferraro Citation2013; Salvatore, Citation2013a).

In the second part of the 19th century, some centralisation of power and banditry diminished in most of the region. We argue that 20th century Latin America best correlates with the European monopolisation of violence by absolutist monarchs in Western Europe over the 16th and 17th Centuries.Footnote1 In Mexico’s particular case, the post-revolutionary State is the first successful venture to integrate distinct actors and social processes under a single (though somewhat flawed and dependent on a network of intermediaries) national project (Pansters Citation2012). As shown in , Mexico had a steadier decline in violence than the rest of the region, probably due to the Mexican Revolution’s legacies; a process that resembles the decline of violence after the civil wars in Central America (see Archer and Gartner Citation1976; Stamatel and Romans Citation2018); (see ).

Indeed, the Porfirian dictatorship in the late 19th century and early 20th century (1876–1911) did ensure some political stability and managed to control (or at least regulate) banditry and put an end (or rather a pause) to regional rebellions. What is more, in contrast to the ‘endemic political conflict of fifty years after Independence’ (Knight Citation1986, 1:15), the Porfirian regime did provide unprecedented stability, even if this was based on continuous repression. However, the sudden outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in 1911 showed the system’s vulnerability and the fragile power that the regime had over the country (Knight Citation1990). More importantly, the Revolution had a demographic cost of 2.1 million, including emigration and lost births. According to McCaa (Citation2003), some 1.1 to 1.4 million people died due to war-related causes. In the words of McCaa, ‘For the Americas, both North and South, the Mexican Revolution was the most significant demographic catastrophe of the twentieth century. The Mexican Revolution’s human cost was exceeded only by the devastation of Christian conquest, colonisation, and accompanying epidemics, nearly four centuries earlier.’ (McCaa Citation2003, 397). Indeed, ‘the Revolution alone made Mexico a very violent country by the standards of twentieth-century Latin America’ (Knight Citation2019b, 28).

Revolutionary violence remained high well into the 1920s, with different intensities across regions. Although some state centralisation had begun, the federal government faced significant military rebellions and a bloody anti-Catholic counterinsurgency campaign in central-western Mexico for three years (1926–1929). The casualties and material destruction between the ‘two sharply contrasting ideologies and national projects’ of this last confrontation were massive (Knight Citation2019a, 36). It was not until the late 1920s, and early 1930ʹs that institution-building took place. The primary sources of political violence (dissident revolutionaries and radical Catholics) were later neutralised (Knight Citation2019a, 37).

The Revolution’s final triumph in the late 1920s neither stopped local violence dynamics nor fully pacified the country. Furthermore, the federal government encouraged many of the agrarian conflicts that took place during the 1930s and 1940s, as well as some practices of patrimonial violence (most notably through the creation of vigilante or paramilitary groups, the protection of local strongmen and the hiring of pistoleros, see Gillingham and Smith Citation2014). However, while the new State was not democratic, it ‘distributed land, built schools, courted organised labour, recruited plebeian politicos, and developed an agglutinative ideology of nationalism and indigenismo’. (Knight Citation2013a, 25).

Unlike the Porfirian regime, the post-revolutionary State incorporated mass organisations and peasant unions. That social base guaranteed the survival of a regime that combined the exercise of practices of force and consent, repression, patronage, and corruption (Falcón Citation1984, 108). The result was a very stable system that guaranteed civilian governments with limited-term times, the absence of military revolts, low-inflation economic growth (at least until 1976), and infrastructure expansion. It was precisely in this period where the violence began to decline.

Theories of the increase and decline in homicide and violence

This section will describe the main theories of the decline in homicide and violence, particularly development policies. The objective is to propound the main theories that could explain the decline in homicides in Mexico. It is essential to point out that most of these theories were developed for the United States and Europe. Therefore, applying them to a Latin American case will test their capability to explain homicide decline processes beyond the experience of the Global North.

The subsections are as follows: centralisation and infrastructural power, economic opportunities and modernisation, control theories, urbanisation and social disorganisation, democratisation and agrarian reforms, and the effects on schooling expansion. As the reader will notice, the variables explaining levels of violence differ between theories; consequently, the authors discuss the causal mechanisms that facilitate their decline or increase. The discussion is summarised in .

Table 1. Expected theoretical effects on violence reduction.

Centralisation and infrastructural power

This theory postulates that centralisation must weaken violence in line with Elias’ work. In 16th century Europe and 20th century Mexico, the consolidation of state power and central administrative authorities were used to deploy violent and focalised repression. This echoes the findings on the rise of the State in Europe by Tilly (Citation1992). The concept that best helps us understand this is probably infrastructural power, developed by Michael Mann some decades ago (Mann Citation1984). Infrastructural power is the ‘capacity of the state to penetrate civil society and implement its actions across its territories’ and is different from ‘despotic power’ understood as ‘the range of actions that the state elite is empowered to make without consultation with civil society groups’ (Mann Citation2008, 355).

Even if the Mexican State’s infrastructural power was relatively low for most of the 20th century, the centralisation of politics around the presidency and the control of local and regional political patronage resulted in an asymmetrical but constant process of the long-term decline in homicides. That does not mean, of course, that state power was not used for triggering violence. Admittedly, the history of Latin America over the last two centuries presents plenty of examples of how state institutions foster ethnic conflicts, prosecute political adversaries, and perpetuate structural inequalities. The Mexican pro-revolutionary State was a primary driver of violence and human rights violations for most of the period analysed. Local and federal governments used legal and illegal violence to eliminate political opponents and groups resisting authoritarian rule (Pensado and Ochoa Citation2018; Herrera Calderón and Cedillo Citation2012; Gillingham and Smith Citation2014). Indeed, repression and coercion were a fundamental part of governance in Mexican politics. However, the main idea is that consolidation of state power in the 20th century correlates with the decline in violence.

Economic opportunities and modernisation

The relative deprivation theories argue that violence arises when the gap between expectations and actual situations widens, particularly in underemployed or unemployed youth bulges (Gurr Citation2015; Messner, Thome, and Rosenfeld Citation2008; Goldstone Citation2002; Urdal Citation2006; Bourguignon Citation2001).

Rational choice, opportunity, and deprivation theories in criminology agree that individuals’ profit greed is part of the decision that drives people to commit violent crimes. There is also the idea that economic growth creates expectations and pressure on the political system, leading to instability and violence if institutions do not take control (Goldstone et al. Citation2010). The simple mechanisms and variables differ between theories, but overall, they see economic development as an opportunity to profit (Becker Citation1968; Gottfredson and Hirschi Citation2017; Fajnzylber, Lederman, and Loayza Citation2002).

As Bergman (Citation2018) argues, the prolonged growth process in Latin America also created opportunities for crime to thrive, particularly violent crime. Bergman draws his assumptions from opportunity theory criminology that sees growth as a marker of new opportunities for crime. At the same time, the State cannot provide enough protection to citizens and individuals. Since the debt crisis of the 1990s, Latin America has seen sustainable growth rates. Mexico’s economic growth rate from the early 1950s to the late 1970s averaged over 6% annually, with an inflation rate lower than 3% (Márquez and Silva Castañeda Citation2015). Therefore, high growth rates can lead to rises in crime in general and rises in violence. Nonetheless, crime and instability also happen when there is a lack of State authority to impose the Rule of Law. From the 1950s to the 1970s, Mexico also saw the consolidation of the Mexican State after the long Mexican Revolution.

Control theories

Control theories posit that formal and informal institutions (e.g., schools, churches, families, factories) control individual behaviours by shaping expectations or executing social sanctions. When controls are established, crime tends to decrease, and vice versa (Hirschi Citation1969; Messer, Rosenfeld Citation1997). Following Elias’ argument that the internalisation of self-restraint by social connections was a driver of pacification, Eisner refers to the concept of social disciplining, an element that provides ‘the cultural and social resources needed for a more orderly conduct of life’ (Eisner Citation2001, 631). Furthermore, Eisner argues that another source of social disciplining is the formation of conscience in moral terms through reading and writing skills (Eisner Citation2014, 126).

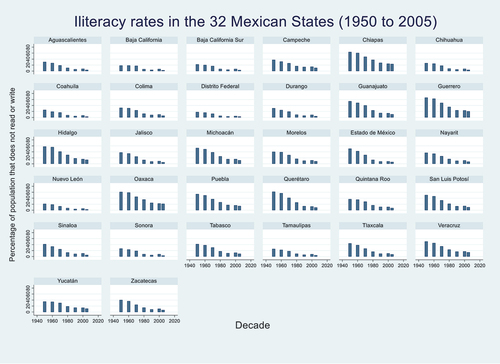

Some Mexican institutions remained stable even despite notable political events. For example, the strict application of the Jacobine Constitution of 1917, which established strong regulations of the Catholic Church, did not affect religious attendance. On the contrary, religious catholic guerrillas called Cristeros resisted violently and could change the repressive government position towards religious freedom (Meyer Citation2008). However, Mexico manifested other changes that did change social institutions: low rates of illiteracy, reduction of birth rates (from 8 to 2 children per woman), and the whole transformation of the Mexican economy towards a more industrial base rather than the traditional agrarian economy that brought forth the revolutionary forces in the first place.

Urbanisation and social disorganisation

The main argument of urbanisation and social disorganisation points out that urban development produces zones with high population density, creating neighbourhoods and regions where policing, social policy, and other factors contribute to the increase of crime (Sampson and Groves Citation1989; Krahn, Hartnagel, and Gartrell Citation1984; Citation1986; Morenoff, Sampson, and Raudenbush Citation2001; Agnew Citation1992). This happens in regions that are rapidly growing due to economic development. As in other theories of social determinants of crime, this depends on how governments cope with the increasing pressure from urban development, how development is planned (or not), and the typical internal migration processes within countries.

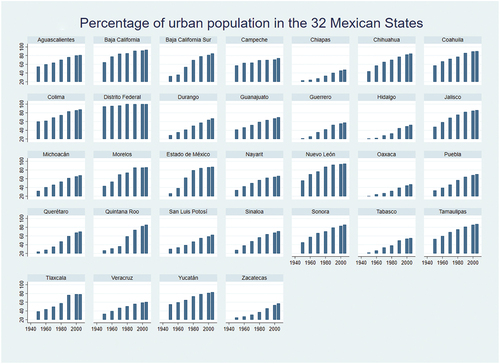

As noted in censuses, Mexico transformed into an urban country in less than 50 years: from 30% of the urban population by the 1940s to more than 70% by the beginning of the new century. This process meant a challenge for the Mexican government to provide housing, services, and employment to millions of Mexican citizens now living in urban areas. Urbanisation was caused by massive internal migration toward the growing urban centres, particularly the metropolitan zones of Mexico City, Guadalajara, and Monterrey. This led to enormous slums with incomplete infrastructure, little access to services, and crowding (Garza Citation2000). Therefore, increases in violent crime were expected in those neighbourhoods.

Agrarian reforms and democratisation

There are some up-and-coming theories on the role of political processes in producing violence and crime. The first one highlights the positive effects of agrarian reforms in reducing violence. The theory posits that land reform mitigates the factors that lead to rural rebellions. In short, agrarian reform works as a counterinsurgency policy (Albertus and Kaplan Citation2013). Since Mexico experienced an agrarian reform in the late 1930s, the theory must be acknowledged and examined (Albertus et al. Citation2016).

The second theory draws on the relationship between violence and democracy. It posits that the democratisation process renders violence unnecessary ‘since all groups and individuals should be able to express their views and interests through a process of rational deliberation’ (Schwarzmantel Citation2010). However, some researchers have pointed out the democratisation paradox in Mexico: the democratisation process that started in the late 1980s coincided with the (re)emergence of multiple forms of violence. Trejo and Ley (Citation2018) found that early democratisation in state governments led to increased violence because middle bureaucratic cadres that used to negotiate with criminal organisations were replaced, subsequently breaking local agreements to withhold violence.

Schooling and violence

The theories and literature reviewed acknowledge implicitly or explicitly the relationship between schooling and violence. For example, youth bulges, modernisation theories, and control theories coincide with the idea that low schooling rates are relevant variables for explaining increased violence. Both theories emphasise the effects of schooling on changing young people’s lives by incorporating them into institutions that control behaviour or create expectations of achievement in life through qualified employment.

Does increasing schooling, therefore, lead to less violence? A recent review of the existing literature on education and political violence found that education (formal schooling) does indeed have an overall pacifying effect on conflict (Østby, Urdal, and Dupuy Citation2019; Neumayer Citation2016). However, the relationship is complex and multidimensional. For instance, Fajnzylber, Lederman, and Loayza (Citation2002) found that educational attainment does not only affect homicides but also robberies. Researchers found that education rates had an essential effect in predicting violence regionally in contemporary Mexico (Juárez, Urdal, and Vadlamannati Citation2020; Gleditsch, Rivera, and Zárate-Tenorio Citation2021).

Therefore, violence reduction is not only about control or expectations. It is also about social policy and the role of the State. As the next section shows, schooling seems to be a relevant driver of violence reduction by the State. The State implemented public policy and contributed to decreasing violent events in Mexico. Of course, schooling was not the only distinctive trait of the intensification of infrastructural power; however, the growing provision of health care and access to water and electricity was one of its more essential features.

Furthermore, as the dynamic that played a crucial role in disciplining and regulating daily life, we consider schooling a relevant part of the consolidation of state power and a cause of modernisation and economic development. Indeed, for most of the 20th century, Mexican institutions were not strong enough to enforce compliance and to efficiently detect societal evasion (cfr: Kurtz Citation2013, 55); however, schooling seems to have been vital in the process of social disciplining. Also, during the 20th century, Catholic allegiance in Mexico has remained highly stable and unemployment relatively low. Thus, the argument is that the main driver of control implemented by the State was through schooling. The increase in schooling signalled that more individuals received state-sanctioned curricular content that effectively changed normative ideas about the value of crime, conflict, and rebellion. Along the lines with Lipset’s views on education, we argue that schooling in post-revolutionary Mexico promoted a culture of peace and obedience to authority (Lipset Citation2001). In , we can see the expected effects of the variables discussed.

Data and methods

Development trends in twentieth-century Mexico

Mexico saw a steady development process during the 20th century. Indeed, economic growth rates have changed over time: from the spectacular 6% annual growth from the fifties to the seventies, to the recurring economic crises from the eighties to the mid-nineties, and finally to the stabilising low growth rate of 3% annually since 1997 (Esquivel Citation2010). This was paired with rapid urbanisation. shows how most Mexican states became highly urban by the end of the twentieth century.

This process can be observed from the National Statistics Institute of Mexico (INEGI in Spanish), which gathers information from modern censuses. For example, more than 40% of the population were illiterate in 1950. In 2005, that figure dropped to 8%. This can be seen in . In 1960, more than 72% had no access to any source of potable water. By 2005, only 13% of the population lived under those circumstances. Due to the stable economic growth and birth rates, Mexico’s youth bulge slowly declined: in 1950, 70% of the population was under 29 years of age, while in 2005, the population aged under 29 only constituted 57%.

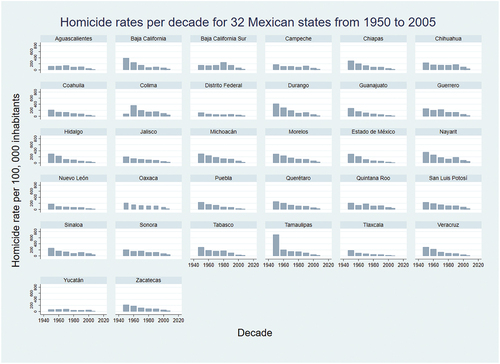

We can see the same trend regarding violence shown in : the gradual decline in homicide rates in Mexico from 1928 to 2005. Escalante Gonzalbo (Citation2009) noted the lack of analysis and statistical data on Mexican violence after reviewing studies of homicides related to drug crimes before the onset of the Mexican Criminal War in 2006. Indeed, Espinal-Enríquez and Larralde (Citation2015) commented that homicide rates grew in some Mexican regions before 2006. However, overall, the national homicide rate remained low.

The most comprehensive academic research published before 2007 was written by Hernández Bringas (Citation1989). In his book, Hernández Bringas studies homicide rates in Mexico from a demographical perspective during the 20th century. Hernández Bringas noticed that age groups’ overall trends fall steadily but remain relatively high in the young population. Also, some states presented slower declines of homicide, even if all states generally showed a downward trend. Consequently, he argues that the overall decline is due to the country’s rapid industrialisation and urbanisation.

Márquez and Silva Castañeda Citation2015: 145–146) summarise these trends: between 1945 and 1982, the GDP tripled, while between 1950 and 1980, the urban population grew from 6.9 to 44.2 million, and the general population expanded from approximately 25 to 66 million. Echarri Cánovas (Citation2005) studied the causes of mortality, including homicides, after the 1980s, when economic crises became more frequent, slowing down Mexico’s economic growth (Márquez Citation2015). Even with an economic crisis, the decrease in mortality rates continued toward the end of the 20th century. Echarri notices that its effect on the decline in homicide is marginal compared to the overall effect of social spending, migration, and overall improvement of the population’s social conditions such as access to health services, education, and housing (Echarri Cánovas Citation2005: 280–281).

The literature produced in epidemiology and public health has found common patterns in homicide victimisation that coincide with homicide trends worldwide: primary victims were young males in deprived regions (Roth et al. Citation2018). Adolescents and young male adults were more likely to die from guns or other injuries methods. Furthermore, many of the researchers found that the central location of victimhood of male youth was in the street, while for women it was in the household (see Arroyo Juárez Citation2001; González Pérez et al. Citation2009; Hernández Bringas and Narro-Robles Citation2010; Híjar-Medina, López-López, and Blanco-Muñoz Citation1997; López et al. Citation1996; Zepeda and Pérez Citation2013; Tuñón Pablos and Bobadilla Bernal Citation2005). This marked decline in violence underscores many violent processes in Mexico and regional variants. As argued before, the convergence of homicide through Mexican states was not uniform. Previous studies cited have not accounted for other forms of social violence drivers.

The work of Piccato (Citation2017, Citation2016) and Speckman Guerra (Citation2018) expounds upon the historiography of social forms of crime in Mexico, especially Mexico City, linked to many social processes such as other forms of crime in the new urban landscapes, honour killings, and how this was portrayed in the media at the time. Also, the historiography of political and drug violence has accumulated over the years. For example, the deployment of military forces in Sinaloa for drug control proposes (Enciso Citation2015; Astorga Citation2005), the campaign against communist guerrillas in southern Mexico (Montemayor Citation1991), and political repression deployed by caciques and governors against political dissidence (Gillingham Citation2012; Pansters Citation2012; Trejo and Ley Citation2018: Knight and Pansters Citation2005; Hernández Bringas and Narro-Robles Citation2010).

While this study does not address these forms of violence because it needs more careful, historiographic, and tailored approaches for regional trends, we can affirm that they do not seem to affect the overall decline in the homicide rate in Mexico. Moreover, many forms of political violence do not translate into homicides, and authorities or non-state armed groups such as guerrillas can purposefully hide evidence of their actions (Krause Citation2017). Further data on disappearances could change this view, but this information is not yet available.

In summary, it is no coincidence that the decline in violence in Mexico happened at the exact moment when the country experienced swift and profound socioeconomic and political changes. As shown in , these processes can lead to contradictory theoretical results about the process of violence decline. We argue that the social development processes were strong enough to overcome the forces of rapid modernisation on violence and even led to a solid and steady decline. In the next section, we argue how we will demonstrate exactly that.

The new database on historical crime rates

As examined before, homicides in Mexico before 2007 are understudied, and data remains scarce. The database ‘Estadísticas del crimen en México: Series Históricas 1926–2008’ collected by Piccato, Hidalgo, and Lajous (Citation2017) sheds light on the scarcity of crime statistics in Mexico. This database has judicial information and other administrative sources on different crimes. Lajous and Piccato (Citation2018) warn that this data under-reports crime rates. As is widely discussed in crime statistics (Coleman and Moynihan Citation1996), not all crime happening in this period was registered by police or judicial authorities. However, the existence of this data allows for a useful approximation and is relevant for analysing trends.

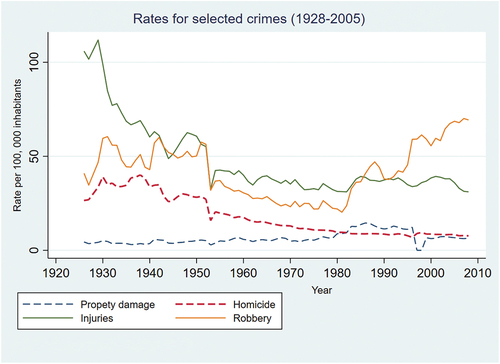

For example, shows the rates per 100,000 inhabitants for several crimes from 1928 to 2005. Crime declined steadily from 1928 towards the 1980s. Robbery and injury rates have increased since then, but property damage and homicide rates have continued to decline. Ergo, crime rates converged during the 20th century until the 1980s. Due to their magnitudes, other crime rates overshadow the Mexican pacification process. Therefore, presents the change in homicide rates in all 32 Mexican states. The homicide rates declined steadily from 1928 to 2008. Understanding the main drivers of this decline is the objective of this paper.

Scope and limitations of the database

Important caveats must be made about the database. First, as discussed before, the database reports crime statistics in local judicial records. While it covers most of the missing data on some relevant crime trends, it underreports actual crime because it is inevitable that not all crimes were reported or registered by the police (Piccato Citation2016, Citation2017). Because of this, consistent data on the state level appears only after the late 1940s. Also, this explains why it cannot be compared with INEGI homicide data from 1990. Additionally, this paper does not address the trends beginning in the late 2000s, when homicide rates rose during the outbreak of the Mexican war on drugs. This also leaves us with no data on the primary characteristics of the victims, such as gender or age.

Second, the historical data available for statistical analysis can be only found on Mexican censuses, which are only regular and comparable from the 1950 census onwards. Because of this lack of data, information from the late 1920s to the late 1940s cannot be analysed. Although data in the Piccato, Hidalgo, and Lajous (Citation2017) database is yearly, censuses only come in decades, so means can only be analysed per decade. Other essential data used on studies of violence reduction are not available in those censuses: alcohol consumption, income inequality, life expectancy, or governmental presence. Hopefully, recent efforts to improve data collection on these topics will foster further investigation into the questions answered and posed within this report.

Unfortunately, detailed historical subnational data on military presence, social movements, disappearances, and state repression was unavailable. New historiographic efforts could aim to have more complete data on socio-political phenomena. Mainly, disappearances could hide a complete figure of homicides. However, there is only data from 2007, beyond the scope of our study. Nevertheless, these limitations should not deter analysis of the data presented: the database is balanced and sufficient for statistical inference. Moreover, an examination of the Mexican homicide decline in Mexico for the period 1950 to 2005 has not been done before. Fortunately, we have this new database.

Variables of interest

As discussed before, the literature on increasing or decreasing violent crime refers to several variables. The variables selected are those comparable within censuses or for which there is enough State disaggregated data since 1950. We briefly discuss the broad implication for diverse fields of literature and discuss these variables’ overall trends during the 20th century in Mexico. presents the mean and standard deviation of each of these variables per decade. In this case, the standard deviation also reveals the convergence processes within Mexican states. It bears mentioning that the analysis only considers data until 2005, before the increase of homicides due to the military’s deployment against drug trafficking organisations.

Table 2. Summary statistics for variables of interest for each decade.

Gross Domestic Product Per Capita (GDP) is the most used proxy for economic growth. As a caveat, apart from the discussion on the effect of economic growth and GDP as a proxy for economic growth, we want to emphasise the rapid acceleration of growth in Mexico. This process follows the regular tendency of development in Mexico. There are clear north/south divergences in which northern states grow faster than southern ones (Esquivel Citation1999). This divide happens for many of the other socioeconomic variables. So, if we see correlations (), we can notice that GDP is correlated to many other variables to some degree. In that sense, the slow convergence between them leads to this process.

Table 3. Effect of development and crime-related variables on homicide rates (1950–2005).

Table 4. Correlation matrix.

Nevertheless, as we will explain, other development processes do not precisely follow this trend. In this case, we use the GDP data for the Mexican states calculated by Carrion-I-Silvestre and German-Soto (Citation2007). Theoretically, GDP effects on growth can be either positive or negative, as summarised before; as such, the results of this study can give us an insight into the effects of growth on violence in Mexico. It is essential to consider that the economic crises of the 1980s had lasting, even permanent, impacts on well-being like education, mortality, and poverty (Fajnzylber, Lederman, and Loayza Citation2002). This is relevant because GDP variance shows how the economic crisis took place in Mexican states.

In the case of the urban population, the main consensus is that large concentrations of the population can aggravate violent crime either by social disorganisation, cultural changes, or increased opportunities to commit violent crime because of the overload of crime state prosecute. Also, as discussed before, the mean years of schooling appear as a variable. As seen in , the mean of schooling years incremented from less than a year in 1950 to more than seven years in 2005. The literacy rate increased throughout the century. The government achieved universal primary schooling in the entire country, though unequal coverage between regions (Martínez Rizo Citation2002; Ornelas Citation1998; Mier y Terán & Romero, Citation2003).

For youth bulge, the mean youth population in Mexico (from 15 to 29 years old) grew from the 1950s to the 1980s and then sharply declined through 2005. Meanwhile, employment varies over different decades. As can be noticed in , the share of the employed population changes over the decades, probably because of the economic crises after the 1970s (Campos Citation2010) and the North American Free Trade Agreement, which also affected income distribution (Cortés Citation2013; Esquivel Citation2011). Ideally, the effects of income inequality would also be observable; however, state-based data was not available before 1950 because household surveys are a more recent development.

Housing and overcrowding are proxies of social disorganisation derived from urbanisation. Overcrowding has become a valuable proxy for other related phenomena in ecological criminology: poor living conditions, family dysfunctionality, and other effects of unstable housing in fast-growing societies (Barkan Citation2000; Sampson Citation2017). Moreover, the married population shows two trends: on one side, family attachments serve as a form of civilisational appeasement by reducing risk-taking behaviour. On the other side, it shows the recurrence of intimate partner violence between men and women (Rosenfeld Citation1997).

To control other phenomena related to violent crime, we also use the rates of robbery, injuries, smuggling, and property damage reported by Piccato, Hidalgo, and Lajous (Citation2017). These crimes are relevant because they have the same trends as homicide rates, but they diverge in the 1980s, as shown in . reveal how crime rates, in general, have convergence patterns. This could mean that violent crimes, such as injuries and homicides, are also committed when robbery, property damage, and smuggling occur, probably because homicides come from protecting criminal organisations dedicated to robbery and other crimes (Gambetta Citation1996). It also shows that federal drug crime rates rise at the end of the century. This indicates the relevance of drug trafficking in the crime landscape and Mexico’s growing prosecution efforts due to the pressure from the United States government (Enciso Citation2010). Recalling Lajous and Piccato (Citation2018) warnings, crime rates reflect how the State prosecutes crime. They can also measure judicial capacity from the state governments but are not necessarily deterred. Crime statistics usually conflict if crime reporting shows the administrative capacity to record or actual prosecution. However, as shown in , these correlations with homicide rates are low. Indeed, these variables can be a proxy of violence and more comprehensive criminal activity that must be included.

Finally, two more variables are relevant as controls: land reform and democratic alternation. Albertus and Kaplan (Citation2013) argue that land reform can be a robust policy to mitigate political violence and can be a helpful tool for authoritarian governments, such as Mexico, to enhance control (Albertus et al. Citation2016). We replicate the land distribution data from Albertus et al. (Citation2016) that comes from the national agrarian registry (RAN in Spanish), which shows the hectares of land distributed by the Mexican government from the early 1920s until 1992 when the government of Carlos Salinas reformed the constitutions to allow the privatisation of land. Land distribution was one of the main goals of the agrarian forces in the Mexican Revolution. Regarding democratic alternation, we created a simple index for states not governed by the Revolutionary Institutional Party (PRI in Spanish). The Mexican state government began to have party alternatives since the National Action Party (PAN in Spanish) came into power in Baja California in 1989 (Cornelius and Hindley Citation1999).

Model specification

After building our panel, we analysed the homicide rates as the dependent variable with the first order autocorrelated Prais-Winsten model using feasible generalised least squares (GLS). Estimators are more efficient when corrected for autocorrelation (Park and Mitchell Citation1980). This correction avoids serial correlation in our data, aggregated by decade, and weight the State’s covariances. This model can be represented as follows:

In this model, is the time series of interest at time t, β is the vector of coefficients, XT is the matrix of explanatory variables, and

represents the error term. Also, because the data is serial, we ran two models using generalised least squares with one autocorrelation disturbance term. To test and control the unobserved component of the database, we calculated both fixed and random effects (Wooldridge Citation2010).

Results and discussion

In , we can see the results of our analysis. The first model evaluates all variables. The subsequent models exclude the land reform variable to include more observations in the analysis. The second model also excludes crime-related variables to test the model’s performance without these controls. Overall, years of schooling and property damage are the most robust variables in all models performed. Furthermore, inhabitants by home are significant in other models. The other variables showed no significant effect on any model.

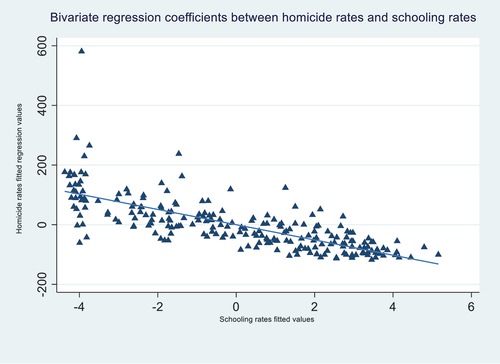

Years of schooling were significant in all models. We graphed a bivariate regression coefficients between homicide rates and schooling rates (). The coefficients on the bivariate model are similar to those on the panel regressions. Overall, the results presented in this paper confirm that Mexico saw a decrease in homicides from 1950 to 2005. The increase in schooling in Mexico had a robust positive effect on the decline in homicide rates. Unfortunately, this process stopped abruptly with the military’s deployment in a new repressive phase of the global drug prohibition regime.

On the other hand, inhabitants by home (models 2 and 5) reveal a contrary effect: the social disorganisation that came after urbanisation led to increased homicide rates. However, this effect was not enough to reverse the overall trend of decline. This means that the increase in urban violence slowed some of the probable gains by the increased schooling rates. This result shows that the benefits of twentieth-century Mexican development were mainly a combination of improved schooling and improved housing.

Robbery and property damage rates show another part of the story: property crime became more common than violence as a type of delinquency, but both phenomena occurred concurrently in Mexico (models 1, 2, 4 & 5). shows that property crime declined with homicide rates parallelly. However, this trend reversed in the early 1980s when Mexico had several financial debt and currency crises.

Youth share and employment had little to no significant effect on the models for except of models 1 and 5. These results contradict institutional anomie and routine theory assumptions, namely that economic growth and changing cycles can augment violent crime. Consequently, the results show that beyond growth – and therefore beyond controlling youth through employment and keeping them in institutional settings – education had another critical effect transmitting values and expectations for a different, more peaceful society. To a certain extent, the authoritarian expectation of obedience to the post-revolutionary State has been discussed in literature about political culture in Mexico (Segovia Citation1975; Craig and Cornelius Citation1980; Somuano Citation2007). Also, the slight effect of the increasing married population shows the effects of family and customs in reducing violence.

The results of this research suggest that education policy had a centralising effect to control the youth bulge during the period analysed. Usually, when studied, fast growth is shown as a marker of conflict. However, this literature recognises that violence and conflict arise when the State does not return enough services from the spoils of growth to the population (Goldstone Citation2002; Goldstone et al. Citation2010). Furthermore, after the 1980s, there was more property crime than homicide, a reaction to a decline a growth after the economic crises. However, this interpretation must be carefully examined in the future with systematic political violence data that currently is not available. Indeed, conflict deaths are usually undercounted (Krause Citation2017). Nonetheless, it seems that episodes of political violence in Mexico during the twentieth century were contained rather than widespread, as discussed before.

Robustness testing

To confirm these results, we run several robustness checks. First, to confirm that the data is stationary, we performed the Harris and Tzavalis (Citation1999) unit-root test for the homicide rate. This test allows for evaluation in time-series and panel data. The value was −7.2007 and the p-value 0.0, confirming that the homicide rate is stationary.

Second, it was necessary to rule out problems with multicollinearity. As shown in , there is a high correlation between GDP, urban population, youth share and schooling. In order to address this issue, we calculated the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) to review any disturbances due to multicollinearity. As shown in , when all variables are considered, the VIF for schooling rates is above seven and the urban population above 4.75. When calculating the VIF a second time, without the urban population variable, the score for schooling reduces to under 4.75, which is under the range of moderately correlated (Daoud Citation2017). When calculating the VIF a third time, we also excluded GDP. In this instance, schooling reduced to 2.93, widely accepted as indicative of no multicollinearity (Allison Citation2009). The models in exclude urban population to avoid disturbances, and the final three models exclude GDP. Therefore, these models are robust.

Table 5. Variance inflation factor of the variables of interest.

Implications and conclusions

To date, scholarly research on the decline in homicide and violence, in general, has overlooked the Latin American pacification process. After the Mexican Revolution, Mexico presents a remarkable example of this process in the region. The contribution of this study is that it shows remarkable differences from European studies of homicide decline: the development process, not only the state-building centralisation of authority, played an essential role in pacification. To this end, this paper advances the work previously done by Eisner and Mann

Twentieth-century pacification through the expansion of education in Mexico is one face of a two-sided coin: on the one hand, this process meant a broad, universalised development policy that could enhance socioeconomic opportunities and, therefore, control the youth population during a rapid urban expansion. Additionally, it promoted obedience to authority, which is recognised explicitly in the civilisational theories of pacification. It was transmitted through Mexican schools all over the territory to varying degrees. Further studies on how education pacifies countries after periods of violence are needed, and this paper contributes to that direction.

However, the findings of this research must be carefully assessed. First, because of the absence of essential data, the findings of this research are limited. So far, there is no public data on political violence, particularly on the repression of human rights protests and prosecution of Marxist guerrillas whose presence surged in Mexico during the twentieth century. The inability to analyse these variables leaves room for bias in the results of this investigation. However, the methods utilised point toward a valid causal relationship despite these co-occurring phenomena. Similarly, data on income inequality or alcohol consumption – also considered relevant in the literature on homicides – is not available and thus could not be analysed.

Second, in this article, we comprehensively summarised the discussion on the role of education in violence reduction (Østby, Urdal, and Dupuy Citation2019). However, due to the level of database aggregation, it is not possible to infer which causal mechanism is behind this correlation. Further studies with historiographic approaches could shed light on this matter. For example, did authoritarian or moral values have a role in homicide decline? Did the expansion of schooling control the youth bulge that Mexico experienced? How much was schooling expansion paired with economic trends such as employment?

Third, criminology studies from ecological and sociological perspectives have long dwelled on the effects of specific policies and socioeconomic trends on crime considering the presence of studies with particular data points throughout the discipline, aggregation at the level of the State obscures inner regional and local variance in homicide trends. However, here we observe the effect of a universalised policy. The country’s almost complete disappearance of illiteracy indicates that the Mexican government successfully opened schools and enrolled students nationwide. Thus, current data shows that a universalised education policy may reduce violence. This finding also supports control theories, such as social disciplining, argued by Eisner. Nonetheless, there are limits on how quantitative data can show mechanisms. Education and local politics historians may find more on the morals, values, and dynamics of youth in Mexico.

Fourth, the lack of gender, age, place, and method of the homicide shadow how the variables of interest had different effects on various groups. Although homicide victims are typically under 40 years old, we cannot assume that was the case during the twentieth century without this data. Nor can homicides of women, which are correlated with sexual violence, be explained with this dataset. The data also limits our ability to determine the nature of those homicides, whether they were street-gang homicides or the result of domestic violence. New data with these correlations would be helpful for cross-analysis in the future.

Nevertheless, the findings of this research contribute to the growing literature on homicide decline and education. Further studies within the Mexican case and abroad can shed more light on how this correlation occurs and in which contexts. Still, this finding could help design policy for homicide reduction. Unfortunately, the events following the deployment of the Mexican Army against drug cartels in 2006 show that this longue durée pacification processes can easily be reversed. Nonetheless, this investigation is a window into how development and social policy help to reduce violence.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful for the kind comments for the previous drafts by Diego Castañeda, Luis Ángel Monroy Gómez Franco, Eduardo Ortíz Juárez, Eugenio Weigend Vargas, Raphael Lima, Eduardo Posada Carbó, Sarah Winifred Hirsch, the internal PhD seminar of the School of Security Studies in King’s College London, and the two anonymous reviewers. We used data provided by Gerardo Esquivel and Michael Albertus.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. This statement is not far from the accounts that locate the birth of modern Argentina as a centralized nation with the military campaign of the ‘Conquest of the Desert’ in the late 1870ʹs and the defeat of the militias of the Buenos Aires providence by the national military (Conde and Gallo Citation1967).

References

- Aburto, J. M., H. Beltrán-Sánchez, V. M. García-Guerrero, and V. Canudas-Romo. 2016. “Homicides in Mexico Reversed Life Expectancy Gains for Men and Slowed Them for Women, 2000–10.” Health Affairs 35 (1): 88–95. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0068.

- Agnew, R. 1992. “Foundation for a General Strain Theory of Crime and Delinquency.” Criminology 30 (1): 47–88. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1992.tb01093.x.

- Albertus, M., A. Diaz-Cayeros, B. Magaloni, and B. R. Weingast. 2016. “Authoritarian Survival and Poverty Traps: Land Reform in Mexico.” World Development 77: 154–170. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.08.013.

- Albertus, M., and O. Kaplan. 2013. “Land Reform as a Counterinsurgency Policy: Evidence from Colombia.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 57 (2): 198–231. doi:10.1177/0022002712446130.

- Allison, P. D. 2009. Fixed Effects Regression Models. Thousand Oaks, California, USA: SAGE publications.

- Archer, D., and R. Gartner. 1976. “Violent Acts and Violent Times: A Comparative Approach to Postwar Homicide Rates.” American Sociological Review 41 (6): 937–963. doi:10.2307/2094796.

- Arroyo Juárez, M. 2001. “Características y situación del homicidio en la Zona Metropolitana de la Ciudad de México 1993-1997.” Papeles de Población 7 (30): 233–245.

- Astorga, L. 2005. El siglo de las drogas: El narcotráfico, del Porfiriato al nuevo milenio. Mexico City, Mexico: Plaza y Janes.

- Barkan, S. E. 2000. “Household Crowding and Aggregate Crime Rates.” Journal of Crime and Justice 23 (1): 47–64. doi:10.1080/0735648X.2000.9721109.

- Becker, G. S. 1968. “Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach.” Journal of Political Economy 76 (2): 169–217. doi:10.1086/259394.

- Bergman, M. 2018. More Money, More Crime: Prosperity and Rising Crime in Latin America. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

- Bourguignon, F. 2001. “Crime as A Social Cost of Poverty and Inequality: A Review Focusing on Developing Countries.” Facets of Globalisation 171–192.

- Calderón, F. H., and A. Cedillo, Eds. 2012. Challenging Authoritarianism in Mexico: Revolutionary Struggles and the Dirty War, 1964-1982. New York, USA: Routledge.

- Calderón, G., G. Robles, A. Díaz-Cayeros, and B. Magaloni. 2015. “The Beheading of Criminal Organisations and the Dynamics of Violence in Mexico.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 59 (8): 1455–1485. doi:10.1177/0022002715587053.

- Campos, R. 2010. “Los efectos de los choques macroeconómicos en el empleo: El caso de México.” Estudios Económicos de El Colegio de México 177–246. doi:10.24201/ee.v25i1.114.

- Carrion-I-Silvestre, L. J., and V. German-Soto. 2007. “Stochastic Convergence Amongst Mexican States.” Regional Studies 41 (4). doi:10.1080/00343400601120221.

- Centeno, M. A., and A. E. Ferraro (2013). Republics of the possible: State building in Latin America and Spain. State and nation making in Latin America and Spain: Republics of the possible, 3–24.

- Cockburn, J. S. 1991. “Patterns of Violence in English Society: Homicide in Kent 1560-1985.” Past & Present 130 (1): 70–106. doi:10.1093/past/130.1.70.

- Coleman, C., and J. Moynihan. 1996. Understanding Crime Data: Haunted by the Dark Figure. Ballmoor, Buckinghan, England, United Kingdom: Open University Press.

- Conde, R. C., and E. Gallo. 1967. La formación de la Argentina moderna. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Paidós. 1.

- Cornelius, W. A., and J. Hindley. 1999. Subnational Politics and Democratisation in Mexico. San Diego La Jolla: Center for US-Mexican Studies, University of California.

- Cortés, F. 2013. “Medio siglo de desigualdad en el ingreso en México.” Economía UNAM 10 (29): 12–34. doi:10.1016/S1665-952X(13)72193-5.

- Craig, A. L., and W. A. Cornelius. 1980. “Political Culture in Mexico: Continuities and Revisionist Interpretations.” In The Civic Culture Revisited, edited by G. Almond and S. Verba, 325–393. Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

- Dai, M. 2013. “Homicide in Asia.” In Handbook of Asian Criminology, edited by J. Liu, B. Hebenton, and S. Jou, 11–23. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-5218-8_2.

- Daoud, J. I. 2017. “Multicollinearity and Regression Analysis.” Journal of Physics: Conference Series December 949(1), 012009). IOP Publishing.

- Echarri Cánovas, C. J. 2005. “Mortalidad y crisis en México.” In Población, crisis y perspectivas demográficas en México, edited by C. Menkes and H. H. Hernández-Bringas, 257–315. Mexico City, Mexico: UNAM

- Eisner, M. 2001. “Modernisation, Self‐control and Lethal Violence. The Long‐term Dynamics of European Homicide Rates in Theoretical Perspective.” British Journal of Criminology 41 (4): 618–638. doi:10.1093/bjc/41.4.618.

- Eisner, M. 2003. “Long-Term Historical Trends in Violent Crime.” Crime and Justice 30: 83–142. doi:10.1086/652229.

- Eisner, M. 2014. “From Swords to Words: Does Macro-level Change in Self-control Predict Long-term Variation in Levels of Homicide?” Crime and Justice 43 (1): 65–134. doi:10.1086/677662.

- Elias, N. 1982. The Civilising Process: State Formation and Civilisation. Vol. II. United Kingdom: Pantheon Books, 1982

- Enciso, F. 2010. “Los fracasos del chantaje régimen de prohibición de drogas y narcotráfico.” In Seguridad nacional y seguridad interior, edited by A. Alvarado and M. Serrano, 61–104. Vol. 15. Mexico City, Mexico: El Colegio de Méxi.

- Enciso, F. 2015. Nuestra historia narcótica: Pasajes para (re) legalizar las drogas en México. Mexico, Mexico City: Debate.

- Escalante Gonzalbo, F. 2009. “Homicidios 1990-2007.” Nexos. September. https://www.nexos.com.mx/?p=13270

- Espinal-Enríquez, J., and H. Larralde. 2015. “Analysis of Mexico’s Narco-war Network (2007–2011).” PLoS One 10 (5): e0126503. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0126503.

- Espinosa, V., and D. B. Rubin. 2015. “Did the Military Interventions in the Mexican Drug War Increase Violence?” The American Statistician 69 (1): 17–27. doi:10.1080/00031305.2014.965796.

- Esquivel, G. 1999. “Convergencia regional en México, 1940-1995.” El Trimestre Económico 66 (264(4): 725–761.

- Esquivel, G. 2010. “De la inestabilidad macroeconómica al estancamiento estabilizador: El papel del diseño y la conducción de la política económica.” Los grandes problemas de México 9: 35–77.

- Esquivel, G. 2011. “The Dynamics of Income Inequality in Mexico since NAFTA.” Economía 12 (1): 155–188. doi:10.1353/eco.2011.0009.

- Fajnzylber, P., D. Lederman, and N. Loayza. 2002. “Inequality and Violent Crime.” The Journal of Law & Economics 45 (1): 1–39. doi:10.1086/338347.

- Falcón, R. 1984. Revolución y caciquismo: San Luis Potosí, 1910-1938. Mexico, Mexico City: Centro de Estudios Históricos, Colegio de Méxi.

- Gabbert, W. 2012. “The Longue Durée of Colonial Violence in Latin America.” Historical Social Research 3: 254–275.

- Gambetta, D. 1996. The Sicilian Mafia: The Business of Private Protection. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Harvard University Press.

- Garza, G. 2000. “Tendencias de las desigualdades urbanas y regionales en México, 1970-1996.” Estudios demográficos y urbanos 15 (3): 489–532. doi:10.24201/edu.v15i3.1085.

- Gillingham, P. 2012. “Mexican Elections, 1910–1994: Voters, Violence, and Veto Power.” The Oxford Handbook of Mexican Politics, edited by, R. A. Camp. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195377385.013.0003.

- Gillingham, P., and B. T. Smith, edited by. 2014. “Dictablanda: Politics.” In Work, and Culture in Mexico, 1938–1968. Durham, North Carolina, USA: Duke University Press.

- Gleditsch, K. S., M. Rivera, and B. Zárate-Tenorio. 2021. “Can Education Reduce Violent Crime? Evidence from Mexico before and after the Drug War Onset.” The Journal of Development Studies 1–18. doi:10.1080/00220388.2021.1971649.

- Goldstone, J. A. 2002. “Population and Security: How Demographic Change Can Lead to Violent Conflict.” Journal of International Affairs 56 (1): 3–21.

- Goldstone, J. A., R. H. Bates, D. L. Epstein, T. Robert Gurr, M. B. Lustik, M. G. Marshall, J. Ulfelder, and M. Woodward. 2010. “A Global Model for Forecasting Political Instability.” American Journal of Political Science 54 (1): 190–208. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00426.x.

- González Pérez, G. J., M. G. Vega López, A. Vega López, A. Muñoz De La Torre, and C. E. Cabrera Pivaral. 2009. “Homicidios de adolescentes en México, 1979-2005: Evolución y variaciones sociogeográficas.” Papeles de Población 15 (62): 109–141.

- Gottfredson, M. R., and T. Hirschi. 2017. “Self-control and Opportunity.” In Control Theories of Crime and Delinquency, 5–20. New York, United States: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781351323727.

- Gurr, T. R. 1981. “Historical Trends in Violent Crime: A Critical Review of the Evidence.” Crime and Justice 3: 295–353. doi:10.1086/449082.

- Gurr, T. R. 2015. Why Men Rebel. New York, USA: Routledge.

- Harris, R. D., and E. Tzavalis. 1999. “Inference for Unit Roots in Dynamic Panels Where the Time Dimension Is Fixed.” Journal of Econometrics 91 (2): 201–226. doi:10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00076-1.

- Hernández Bringas, H. 1989. Las muertes violentas en México. Centro Regional de Investigaciones Interdisciplinarias,Cuernavaca, Mexico: UNAM

- Hernández Bringas, H., and J. Narro-Robles. 2010. “El homicidio en México, 2000-2008.” Papeles de Población 16 (63): 243–271.

- Híjar-Medina, M., M. V. López-López, and J. Blanco-Muñoz. 1997. “La violencia y sus repercusiones en la salud: Reflexiones teóricas y magnitud del problema en México.” Salud Pública de México 39 (6): 565–572. doi:10.1590/S0036-36341997000600010.

- Hirschi, T. 1969. “A Control Theory of Delinquency.” Criminology Theory: Selected Classic Readings 1969: 289–305.

- Johnson, D. T. 2008. “The Homicide Drop in Postwar Japan.” Homicide Studies 12 (1): 146–160. doi:10.1177/1088767907310854.

- Johnson, E. A., and E. H. Monkkonen, Eds. 1996. The Civilisation of Crime: Violence in Town and Country since the Middle Ages. Chicago, USA: University of Illinois Press.

- Johnson, E. A., R. D. Salvatore, and P. Spierenburg. 2012. “Murder and Mass Murder in Premodern Latin America: From Pre-colonial Aztec Sacrifices to the End of Colonial Rule, an Introductory Comparison with European Societies.” Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung 3: 233–253.

- Johnson, E. A., R. D. Salvatore, and P. Spierenburg. 2013. “Introduction: Murder and Violence in Modern Latin America.” Bulletin of Latin American Research 32 (s1): 1–11. doi:10.1111/blar.12116.

- Juárez, N. C., H. Urdal, and K. C. Vadlamannati. 2020. “The Significance of Age Structure, Education, and Youth Unemployment for Explaining Subnational Variation in Violent Youth Crime in Mexico.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 39: 0738894220946324. doi:10.1177/0738894220946324.

- Knight, A. 1986. “La revolución mexicana: ¿burguesa, nacionalista o simplemente una gran rebelión?” Cuadernos Políticos 48: 5–44.

- Knight, A. 1990. The Mexican Revolution: Counter-revolution and Reconstruction. Lincoln, Nebraska: U of Nebraska Press.

- Knight, A. 2013a. “La cultura popular y el Estado revolucionario en México, 1910-1940.” Repensar la Revolución Mexicana 1: 273–349.

- Knight, A. 2013b. “War, Violence and Homicide in Modern Mexico.” Bulletin of Latin American Research 32 (s1): 12–48. doi:10.1111/blar.12106.

- Knight, A., and W. G. Pansters. 2005. Caciquismo in Twentieth-century Mexico. London, United Kingdom: Institute for the Study of the Americas.

- Krahn, H., T. F. Hartnagel, and J. W. Gartrell. 1984. Explaining the Link between Income Inequality and Homicide Rates: A Cross-national Study. Alberta, Canada: Population Research Laboratory, Department of Sociology, University of Alberta.

- Krahn, H., T. F. Hartnagel, and J. W. Gartrell. 1986. “Income Inequality and Homicide Rates: Cross-National Data and Criminological Theories.” Criminology 24 (2): 269–294. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1986.tb01496.x.

- Krause, K. 2017. “Bodies Count: The Politics and Practices of War and Violent Death Data.” Human Remains and Violence: An Interdisciplinary Journal 3 (1): 90–115. doi:10.7227/HRV.3.1.7.

- Kurtz, M. J. 2013. Latin American State Building in Comparative Perspective: Social Foundations of Institutional Order. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Lajous, A., and P. Piccato. 2018. “Tendencias históricas del crimen en México.” Nexos April. https://www.nexos.com.mx/?p=36958

- Lipset, S. M. 2001. “Cleavages, Parties and Democracy. Party Systems and Voter Alignments Revisited.” 3–9.

- López, M. V., M. C. Híjar Medina, R. A. Rascón Pacheco, and J. Blanco Muñoz. 1996. “Mortality by Homicide, the Fatal Consequences of Violence: The Case of Mexico, 1979-1992.” Revista de Saúde Pública 30 (1): 46–52. doi:10.1590/S0034-89101996000100006.

- Mann, M. 1984. “The Autonomous Power of the State: Its Origins, Mechanisms and Results.” European Journal of Sociology 25 (2): 185–213. doi:10.1017/S0003975600004239.

- Mann, M. 2008. “Infrastructural Power Revisited.” Studies in Comparative International Development 43 (3–4): 355. doi:10.1007/s12116-008-9027-7.

- Márquez, G. 2015. “De crisis y estancamiento: La economía mexicana, 1982-2012.” In Claves de la historia económica de México: El desempeño de largo plazo (siglos XVI-XXI), edited by G. Márquez, 179–215, Mexico City, Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Economica.

- Márquez, G., and S. Silva Castañeda. 2015. “Auge y decadencia de un proyecto industralizador, 1945-1982.” In Claves de la historia económica de México: El desempeño de largo plazo (siglos XVI-XXI), edited by G. Márquez, 143–178, Mexico, Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Economica.

- Martínez Rizo, F. 2002. “Nueva visita al país de la desigualdad. La distribución de la escolaridad en México, 1970-2000.” Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa 7 (16): 415–443.

- McCaa, R. 2003. “Missing Millions: The Demographic Costs of the Mexican Revolution.” Mexican Studies 19 (2): 367–400. doi:10.1525/msem.2003.19.2.367.

- Merino, J. 2011. “Los operativos conjuntos y la tasa de homicidios: Una medición.” Nexos, June.

- Messner, S. F., and R. Rosenfeld. 1997. “Political Restraint of the Market and Levels of Criminal Homicide: A Cross-national Application of Institutional-anomie Theory.” Social Forces 75 (4): 1393–1416.

- Messner, S. F., H. Thome, and R. Rosenfeld. 2008. “Institutions, Anomie, and Violent Crime: Clarifying and Elaborating Institutional-anomie Theory.” International Journal of Conflict and Violence (IJCV) 2 (2): 163–181.

- Meyer, J. A. 2008. The Cristero Rebellion: The Mexican People between Church and State 1926–1929. Vol. 24. Cambridge, United Kingdom.: Cambridge University Press.

- Mier y Terán, Marta and Cecilia Rabell Romero 2003. ”Inequalities in Mexican Children's Schooling.” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 34(3).

- Montemayor, C. 1991. Guerra en el Paraíso. Mexico City, Mexico: Diana.

- Morenoff, J. D., R. J. Sampson, and S. W. Raudenbush. 2001. “Neighborhood Inequality, Collective Efficacy, and the Spatial Dynamics of Urban Violence.” Criminology 39 (3): 517–558. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2001.tb00932.x.

- Neumayer, E. 2016. “Good Policy Can Lower Violent Crime: Evidence from a Cross-National Panel of Homicide Rates, 1980–97.” Journal of Peace Research. doi:10.1177/00223433030406001.

- Ornelas, C. 1998. “La cobertura de la educación básica”, en Pablo Latapí Sarre (coord).” Un siglo de educación en México, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica 111–140.

- Osorio, J. 2015. “The Contagion of Drug Violence: Spatiotemporal Dynamics of the Mexican War on Drugs.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 59 (8): 1403–1432. doi:10.1177/0022002715587048.

- Østby, G., H. Urdal, and K. Dupuy. 2019. “Does Education Lead to Pacification? A Systematic Review of Statistical Studies on Education and Political Violence.” Review of Educational Research 89 (1): 46–92. doi:10.3102/0034654318800236.

- Pansters, W. G. 2012. “Zones of State-making: Violence, Coercion, and Hegemony in Twentieth-century Mexico.” Violence, Coercion, and State-Making in Twentieth Century Mexico: The Other Half of the Centaur 3–42.

- Park, R. E., and B. M. Mitchell. 1980. “Estimating the Autocorrelated Error Model with Trended Data.” Journal of Econometrics 13 (2): 185–201. doi:10.1016/0304-4076(80)90014-7.

- Pennock, C. D. 2012. “Insights from the ‘Ancient Word’: The Use of Colonial Sources in the Study of Aztec Society.” In Engaging Colonial Knowledge, edited by R. Roque and K. A. Wagner, 115–134. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pensado, J. M., and E. C. Ochoa, Eds. 2018. México beyond 1968: Revolutionaries, Radicals, and Repression during the Global Sixties and Subversive Seventies. Arizona, USA: University of Arizona Press.

- Phillips, B. J. 2015. “How Does Leadership Decapitation Affect Violence? the Case of Drug Trafficking Organisations in Mexico.” The Journal of Politics 77 (2): 324–336. doi:10.1086/680209.

- Piccato, P. 2016. “Crime, Truth, and Justice in Modern Mexico: Notes for a National History.” The Americas 73 (4): 491–512. doi:10.1017/tam.2016.77.

- Piccato, P. 2017. A History of Infamy: Crime, Truth, and Justice in Mexico. Berkeley, California, USA:Univ of California Press.

- Piccato, P., S. Hidalgo, and A. Lajous (2017). Estadísticas del crimen en México: Series Históricas 1926—2008. https://ppiccato.shinyapps.io/judiciales/

- Rosenfeld, R. 1997. “Changing Relationships between Men and Women: A Note on the Decline in Intimate Partner Homicide.” Homicide Studies 1 (1): 72–83. doi:10.1177/1088767997001001006.

- Roth, G. A., D. Abate, K. H. Abate, S. M. Abay, C. Abbafati, N. Abbasi, and H. Abbastabar. 2018. “Global, Regional, and National Age-sex-specific Mortality for 282 Causes of Death in 195 Countries and Territories, 1980–2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017.” The Lancet 392 (10159): 1736–1788. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7.

- Salvatore, R. D. 2013. “Conclusion: Violence and the ‘Civilising Process’ in Modern Latin America.” Bulletin of Latin American Research 32 (s1): 235–269. doi:10.1111/blar.12115.

- Salvatore, R. D. 2013a. “Imperial Revisionism: US Historians of Latin America and the Spanish Colonial Empire (Ca. 1915–1945).” Journal of Transnational American Studies 5 (1). doi:10.5070/T851011618.

- Sampson, R. J. 2017. “Family Management and Child Development: Insights from Social Disorganisation Theory.” In Facts, Frameworks, and Forecasts, edited by J. McCord, 63–94. New York: Routledge.

- Sampson, R. J., and W. B. Groves. 1989. “Community Structure and Crime: Testing Social-disorganisation Theory.” American Journal of Sociology 94 (4): 774–802. doi:10.1086/229068.

- Schwarzmantel, J. 2010. “Democracy and Violence: A Theoretical Overview.” Democratisation 17 (2): 217–234. doi:10.1080/13510341003588641.

- Segovia, R. 1975. La politización del niño mexicano. Mexico City, Mexico: El Colegio de Méxi.

- Somuano, M. F. 2007. “Evolución de valores y actitudes democráticos en México (1990-2005).” Foro Internacional 47: 926–944.

- Speckman Guerra, E., Ed. 2018. Horrorosísimos crímenes y ejemplares castigos. Una historia sociocultural del crimen, la justicia y el castigo (México, siglos XIX y XX). San Luis Potosí, Mexico: Mexico City, Mexico: El Colegio de San Luis.

- Spierenburg, P. 1996. “Long-term Trends in Homicide: Theoretical Reflections and Dutch Evidence, Fifteenth to Twentieth Centuries.” In The Civilisation of Crime: Violence in Town and Country since the Middle Ages, edited by Eric A. Johnson and Eric H. Monkkonen, 63–105. Champaign, United States: University of Illinois Press

- Spierenburg, P. 2012. “Long-term Historical Trends of Homicide in Europe.” In Handbook of European Homicide Research, edited by Liem, Marieke CA and William Alex Pridemore, 25–38. New York, NY: Springer.

- Stamatel, J. P., and S. H. Romans. 2018. “The Effects of Wars on Postwar Homicide Rates: A Replication and Extension of Archer and Gartner’s Classic Study.” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 34 (3): 287–311. doi:10.1177/1043986218769989.

- Tilly, C. 1992. Coercion, capital, and European states, AD 990-1992. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Oxford.

- Trejo, G., and S. Ley. 2018. “Why Did Drug Cartels Go to War in Mexico? Subnational Party Alternation, the Breakdown of Criminal Protection, and the Onset of Large-Scale Violence.” Comparative Political Studies 51 (7): 900–937. doi:10.1177/0010414017720703.

- Tuñón Pablos, E., and D. J. B. Bobadilla Bernal. 2005. “Mortalidad en varones jóvenes de México.” Estudios Sociales. Revista de Alimentación Contemporánea y Desarrollo Regional 13 (26): 68–84.

- Urdal, H. 2006. “A Clash of Generations? Youth Bulges and Political Violence.” International Studies Quarterly 50 (3): 607–629. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2006.00416.x.

- Wooldridge, J. M. 2010. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge, Massachusets, USA: MIT press.

- Ylikangas, H., P. Karonen, M. Lehti, and E. H. Monkkonen. 2001. Five Centuries of Violence in Finland and the Baltic Area. Athens, Ohio, USA: Ohio State University Press.

- Zepeda, E. Y., and M. Y. Pérez. 2013. “Homicidio y marginación en los municipios urbanos de los estados más violentos de México, 2000-2005.” Estudios Demográficos y Urbanos 28: 32.