Abstract

In this paper we present the major theoretical and methodological pillars of evolutionary political economy. We proceed in four steps. Aesthetics: In chapter 1 the immediate appeal of evolutionary political economy as a specific scientific activity is described. Content: Chapter 2 explores the object of investigation of evolutionary political economy. Power: The third chapter develops the interplay between politics and economics. Methods: Chapter 4 focuses on the evolution of methods necessary for evolutionary political economy.

1. Introduction

A spectre is haunting Europe, the spectre of Capitalism. To paraphrase Marx famous evaluation of Europe’s political situation in the middle of the nineteenth century quite accurately describes the current turmoil of European politics. Extreme unemployment rates, an extremely fragile financial architecture, a renaissance of fascism and nationalism in several forms and many countries, all that seems to be further spurred by the spectre of capitalism. But while actual capitalism is omnipresent, its scientific justification, the ideology of the ruling class, so-called mainstream economics, is describing general equilibrium worlds that are completely decoupled from what happens here. Capitalist decision-makers in European governments are left alone and are desperately trying to extract some knowledge from these empty formalisms. The danger is that the spectre of capitalism is transforming into the spectre of fascism again.

In this rather dramatic environment, this paper proposes the research program of evolutionary political economy (EPE) as a means to understand the current situation, eventually even to serve as a guide for political intervention. To do so we are starting with a chapter on the aesthetic appeal of EPE following the (Hegelian) idea that you have to seduce young intellectuals to be attracted by the sea of knowledge to go into the water and learn swimming. Once they are in, they are learning to swim by their own thoughts. The following chapters then describe the interplay between content of EPE, the power relations it describes, and the formalisms it will apply. Though this text often remains to be further specified and elaborated, we nevertheless hope to convince our readers to join the theoretical work along the lines we propose. The best entry point into a theoretical discourse often is a pre-theoretical consideration, thus we start with the aesthetics of evolutionary political economy.

2. Aesthetics

EPE is an aesthetically appealing field of scientific activity. In the language of today’s youth: EPE is epic. There are several reasons for this property of EPE, the most important ones can easily be described.

First of all, it is immediately visible that EPE is just the latest part of the grand approach of evolutionary theory, of a theory that aims to explain the emergence and further development of life forms, of living systems.Footnote 1 This high aspiration, more precisely to be an important piece in the mosaic of such a groundbreaking scientific project, is extremely stimulating. Even if the individual researcher feels small when compared to the enormous task ahead,Footnote 2 there nevertheless is an atmosphere of contributing to something substantial. This feeling exists independently of a rational evaluation of the capacity of the researcher, even without knowing too much about what already has been achieved; it is just a pre-rational feeling—and that is exactly what the classic notion of aesthetics is defining.

It is interesting to note that vision of this kind not only must precede historically the emergence of analytic effort in any field but also may re-enter the history of every established science each time somebody teaches us to see things in a light of which the source is not to be found in the facts, methods, and results of the pre-existing state of the science.

Contrary to a common misunderstanding, beauty does not lie in the eye of the beholder,Footnote 4 even the extension that it lies in the mind of the beholder is still misleading. The experience of beauty rather occurs in the process of interaction with something outside the individual mind. It is a property of a special type of dialogue,Footnote 5 more precisely an interaction that goes beyond the communication level of a dialogue, leading from metaphysical action to physical action. It is the mirror that certain types of beautiful interaction enable, that they indeed create, which is attractive. EPE is a theoretical object of investigation that puts the individual researcher in front of the mirror, showing the evolution of the whole human species.

Her or his own evolution, Hegel called it ‘Werden’ (becoming), is reflected as the morphogenetic or developmental part of the larger social process.Footnote 6 This typically has been stated as becoming conscious that the observer is part of the observation. It involves a special role of the social scientist, namely to take the concept of time as well as history serious, to be able to shape the future of social evolution. This new type of power is at the aesthetic core of EPE. The natural sciences that emerged in the seventeenth century only indirectly contributed to this task by discovering laws of nature that could be cleverly exploited by the respective ruling classes to enhance their power—and thus stimulate further social revolutions as the limits of old class settings became visible faster. EPE, emerging in the nineteenth century, sets out to shape social evolution directly. The arrow of time that occurs in the theoretical physics of the 2nd law of thermodynamics points towards universal entropic degradation. This arrow of time is inverted by EPE on social grounds, pointing to more and more sophisticated and specialized social organization, to consciously shaped order (including the ‘disorder’ produced by disruptive innovation). Instead of discovering laws (like the natural sciences), EPE puts time at the centre of its conceptual apparatus and (1) uses history to study the evolution of social laws shaping the respective era, (2) introduces welfare of the human species as a goal function for inventing new social laws and (3) proposes ways to implement these welfare enhancing social laws. The researcher in EPE leaves the ivory tower (or sterile laboratory) of the natural scientist and steps out into the exciting arena of political struggle for a better life for all.Footnote 7 This step is primarily an aesthetic one and secondly an analytical one.

Closely related to the just mentioned dimension of aesthetics is another pole of attraction: EPE is neither focusing on too singular processes nor on too general issues. It focus es on the ‘particular’ (Hegel’s ‘das Besondere’) that lies in between. The general and eternally valid law of structural sciences like mathematics that makes its discoverer eternal is a non-token as is the singular highly specialized work of a researcher developing a drug for a pharmaceutical firm—making this singular contribution invisible. The researcher and the contribution are less separated, neither the most improbable case of an eternal discovery nor a standard case of invisibility are the rule. Investigators in EPE can “zoom-in” or “zoom-out” with respect to their object of investigation. They also might be panning their camera freely, more to the past or more towards social designs for the future. In doing so, the community of EPE researchers nevertheless remarks the reappearance of generality: it reappears as the pattern of evolution-revolution-evolution-revolution- … Zooming-in on the time axis, on a particular era or an event when a particular sequence of this pattern is occurring, reveals the particular mechanics of continuity and break. Why is such research aesthetically attractive? Consider everyday life: Waves of routine steadily undermine a rock of dissatisfaction with routine achievements at which they break. At some point in time the rock falls and within a short time a new constellation emerges, new types of waves roll again against a new rock. See the answer to the question? It’s only Rock & Roll! Or, taking an alternative route to the experience of beauty, note Adorno’s famous remark that ‘the break is the signum of modernity’. EPE is modern aestheticsFootnote 8 since its generality reappears as the fractal structure of investigations into breaks between styles of social evolution. EPE as a form of modern art certainly is a refreshing perspective to start with.

And here comes the aesthetic appeal: Social scientists of the younger generation grew up with new information and communication technologies; they all know how to program, they all saw the tremendous global change in lifestyle brought about by mobile telephones and the internet. For them the new toolbox of agent-based modelling and computational social simulation—and the revival of game theory enabled by this toolbox—is not a terra incognita. This is their everyday formalization approach. EPE can thrive on the smart, accessible and easily understandable simulations, its unique formalization device enables. And this technology-driven renaissance of EPE first only needs the high propensity of computer geeks to program! At this point the euphoria for the new dimension of aesthetic appeal badly needs a caveat. A formal language alone is always insufficient to guarantee adequate scientific modelling. (Preliminary) success always hinges on the combination of empirical observation and (eventually formal) scientific language. In the case of EPE this implies an analysis of the history of the respective political economy phenomenon as well as the force of abstraction necessary to propose new welfare-increasing solutions. In both respects computers increasingly help, but (so far) cannot replace genuine scientific work of the social scientist.

3. Content

All social science starts with a look back on the history of living systems, using an increasingly scientific language to describe it. This chapter concentrates on what is to be described, i.e. on history, while chapter 4 focuses on the evolution of the formal languages used. But social science is more than just a chronological description of what had happened in the past. To be a science means to elaborate the essence of what is historically observed. Simple perception has to be enriched by interpretation, i.e. by grafting patterns, a system of causal relationships, onto the chaos of impressions. By filtering received perceptions and proposing patterns as being essential, scientific work becomes useful for the society of which it is part of. The scientific proposal gains importance since it promises to guide actions to take advantage of patterns repeated in the future. The logic of ideas applied to filter observations therefore frames the current use of scientific results, in this sense all science carries an ideological component. If the scientific community is part of a society and its object of investigation is its political economy, which itself is constituted by different classes, then it is evident that also the use derived from science will point to different directions: The scientific community will fall apart, and pretty much so along the lines of class divisions.Footnote 9

What makes our approach to EPE special is its long-run orientation that allows to include emergence and disappearance of classes, i.e. their finite dynamics,Footnote 10 as an integral and endogenous part of the theory itself. The particular interpretation of these finite dynamics as evolutionary dynamics hints at Darwin’s approach in biology: The evolution of species, i.e. emergence, adaption, and disappearance of species, follows the changes of the environment these species live in, an environment that itself is continuously changing—and not the least so because of the activities of the species which it houses. Evolutionary theory of living systems understood in this manner consists of both, biology and EPE. As an immediate consequence the borderline between the two disciplines has to be discussed—from an evolutionary perspective, of course, namely as an endogenously emergent break.

But before this type of break is discussed, it is useful to take a look at the break from non-living systems to living systems. This is interesting because current mainstream economic theory comes in a mathematical disguise that has been borrowed almost completely from nineteenth century mechanics (Smith & Foley, Citation2002), a theory of non-living matter.Footnote 11 The two central laws of this ‘old physics’ go back to Newton and are known as the two laws of thermodynamics.

Roughly spoken, the first law of thermodynamics states that in a closed system the sum total of energy is constant. As a remedy the first law of thermodynamics was amended by a second law of thermodynamics, which makes explicit use of the irreversibility of time in postulating a long-run increase of entropy. The newly introduced concept of ‘entropy’ again (like ‘energy’) describes a measurable property of the systemFootnote 12 ; but now the law does not refer to constancy and closure, it instead postulates a stochastic law of an (with time) irreversibly increasing entropy. Again this law links new concepts allowing for an interpretation in different causal directions. Underpinning the concept of entropy is the hypothesis that there is a dynamic microstructure that has to be modelled more in detail to allow for the understanding of the transition from one level of entropy to the next. A causal interpretation starting with this dynamic microstructure would propose a well-defined entropy is causing the decrease in entropy in the long-run. On the contrary—and in parallel—the way in which structure is to be described can be seen as a consequence of entropic degradation observed in the first place.Footnote 13

At this point an important idea of the eminent physicist Erwin Schrödinger has to be mentioned. In his book ‘What is Life?’ (Schrödinger, Citation1944) he argues as follows: If the second law of thermodynamics is valid and if living systems are a subset of all systems (if living systems have a purely physical dimension), then it is straightforward to characterize living systems as those systems that decrease entropy! Since this is only possible as a counter-movement to the still valid 2nd law of thermodynamics, it can only occur during the finite time span that the adjective ‘stochastic’ of this law permits. The phenomena of birth and death, i.e. begin and end of this time-span, are intrinsically linked to living systems. In-between birth and death, so-called negentropy can occur, processes can build-up structures and can organize the elements of the living system, which thus temporarily resists the long-run tendency of all matter. The details of how this is possible, of how the sequence of different steps of this resistance against increasing entropy emerge, this is precisely what evolutionary theory is trying to investigate.

Today, the physicist Erwin Schrödinger therefore often is considered to be one of the first ancestors of modern microbiology. In more profane words: Biology of fauna and flora is part of evolutionary theory as well as any social science. All parts of this science of living systems try to understand the modular and nested steps of the build-up process of the order or hierarchy of systems (Simon, Citation1962)—first descriptive only, later with the goal of using this knowledge for intervention in the future course of events. Charles Darwin’s pivotal insight was to direct the focus of research towards the fact that evolutionary processes are characterized by coming in rather abrupt steps—in time as well as in space. His concept of the species is used to name a certain step of an evolutionary development that takes place in a well-defined spatial environment during a well-defined time period. Where these steps come from, how a certain step makes the next one possible and probable, this is already announced as a major topic of research in the title of his book ‘The Origin of Species’ (Darwin, Citation1859).Footnote 14

In the 2nd law of thermodynamics the three central new concepts were the dynamic microstructure, which has a measurable property called entropy, and the property of the rule to be a stochastic rule. Since it postulates a long-run continuous process, its negation should start with a short-run stability consideration. How can a relatively stable stage that a living system has reached in its development of order be described.Footnote 15 ? On the one hand there must be stabilizing forces at work that drive the system back to its dominant structural setting if small disturbances from the environment disturb it. On the other hand the reasons for the metamorphosis to the next step must also be slowly developing during the still stable current step. Somehow their still inessential accumulation and slowly accelerating visibility must also be an endogenous element of the current stage. Each stage thus contains stabilizing as well as destructive forces—and they are linked to each other. The inversion of the 2nd law therefore leads to the introduction of a new central concept: contradiction.

As Lucio Colletti already elaborated 40 years ago it is necessary to distinguish between real opposition and dialectical contradiction (Colletti, Citation1975). In the material world forces can point in (at least partially) opposing directions. Each of these forces does not cease to exist if all of the other forces stop. The further development of the system depends on the specific interdependencies between these partially opposing forces, these real oppositions. On the other hand the dialectical contradiction is an element in the sphere of language. It only can influence the material world via its influence on the actions of the material carriers of language. A dialectic that remains with its self-negation dynamics in the sphere of language can at best produce only new words.Footnote 16 To become an evolutionary force, language therefore had to be developed into an action-guiding tool shared by its physical carriers. Since only the homo sapiens has evolved a language that goes far beyond the simple impulse-reaction mechanism used in all other species, it is possible and advisable to restrict the inversion process to a subset of evolutionary theory, namely to EPE.Footnote 17

4. Power

Since then societies are confronted with real oppositions and reproduce their social conflicts on behalf of dialectical contradictions. Thereby real oppositions—such as the short-run development of a single human being and the long-run tendency of entropic degradation—carry enough potential for societal struggles, such as ‘the general struggle for entropy’ (Georgescu-Roegen, Citation1971, pp. 306–315) has highlighted. Georgescu-Roegen conceives the entropy law and its implications for economic production as a critical element for social as well as biological reproduction of social conflict between the capitalist and the working class. The capitalist production process is characterized through the principle of accumulation (Marx, Citation1867) which establishes a given continuity in capital. This continuity reproduces the involved power relations every round by “separating labor force from labor conditions” (Marx, Citation1867, p. 306) and makes the terms of labour exploitation appear as ‘naturally given’. Thereby the relations of production strongly influence the distributional results: “[e]very societal production process is at the same time a process of reproduction”. (Marx, Citation1867, p. 591) This relation characterizes the social reproduction of class and thereby power relations. Georgescu-Roegen (Citation1971) adds an evolutionary element to the Marxian concept of social reproduction:

In a society where personal wealth and social rank are highly correlated—as is the case under the regime of private ownership—the gene of low fertility tends to spread among the rich, and that of high fertility among the poor. On the whole, the family with very few children climbs up the social ladder, and that with more than the average number of offspring descends it. (Georgescu-Roegen, Citation1971, p. 318)

Our modest suggestion is to focus firstly on the current power relations that have grown out of the Fordist accumulation regime, since we know these mechanics better than the ones emerging in the accumulation regime of bio-capitalism. The point of departure for such an analysis is given by “conflict rather than harmony” as Gruchy elaborated once (Gruchy, Citation1973, p. 623). As already argued in the previous sections, the aesthetics of an EPE approach is given by its focus on the particular that lies in between, respectively, the particular object of interest in the matter of conflict-driven change between the poles of politics and economics is clearly the structure of power.

As a first aspect of power we aim to highlight institutional, organizational and economic power that rises through monopolistic and oligopolistic competition. In his presidential address to the American Economic Review in 1973, Galbraith (Galbraith, Citation1973, p. 2) famously argued that “in making economics a non-political subject” economics “… destroys its relation with the real world”. Elsewhere Galbraith (Citation1967) has developed a concept of economic power that goes beyond the traditional understanding of market power in perfect competition, rather it involves “… power to impose corporate decisions on consumers, the community, and the state”. as (Gruchy, Citation1973, p. 643) explains. This aspect of power appears only within an industrialized capitalism where large-scale corporations have absorbed

… a large share of the nation’s educational and research activities… Having control of much of the nation’s resource of scientific and technological expertise, the large industrial enterprises are in a strong position to influence the course of national economic development. (Gruchy, Citation1973, p. 634)

There is an inner area or sector of large-scale oligopolistic industrial enterprises and an outer sector of small-scale mainly competitive enterprises. The outer area functions very much as does a market economy in the manner indicated in all standard economics textbooks … In the inner heartland of the economy relations between the giant corporations and the state are close, and profit maximization is secondary to the expansion of sales and the enhancement of the corporation’s power and prestige.

Capitalism transforms itself through the accumulation of ever new forms of capital and a corresponding mode of regulation (Lipietz, Citation1992, p. 2). A specific regime of accumulation stabilizes only with regard to established institutional stability, created by the particular mode of regulation. The specific mode of regulation established by neoliberalism could stabilize the accumulation of financial capital (Boyer, Citation2000) peaking in 2008 (Tabb, Citation2010). Within this regime we find a new powerful species of corporations that has originated through the vast integration of international capital markets, i.e. the “financially enhanced transnational company” (Toporowski, Citation2010, p. 920). This novel type of company orientates its power not on production output and revenues, but on its financial appraisal, its shareholder value. The transnational company (TNC) stands in conflict with the traditional national industrial company that was always dependent on the interest rate on corporate loans as well as the domestic tax on profits whereas the TNC follows the interest rate on asset prices and is completely independent from tax regimes. The latter capitalizes via the financial markets and is free to choose its tax home.

As a second aspect of power we aim to highlight endogenous power. Following Mouffe (Citation2000/2009) we are always confronted with direct oppositions in political processes and can speak of an ‘agonistic nature’ of politics. Thereby democracy entails a variety of contradictions that are not to overcome (Scholz-Wäckerle, Citation2016) on large-scale. However, democracy enables social emancipation in its very active and practical meaning, consider the women’s suffrage movement or the ecological movements that have managed to transform from cultural change to institutionalization (Castells, Citation2009, p. 300). These examples highlight what Laclau and Mouffe (Citation1985/2014, p. 136) consider with the power of resistance in a very Foucauldian understanding: “… wherever there is power there is resistance … if we recognize that there is a large variety in the form this resistance takes”. Power is here understood as bio-power that appears as endogenous population control (Foucault, Citation1974/2004). Michel Foucault has dedicated much of his work on the transformation from the sovereignty to the disciplinary and control society. This aspect is truly relevant for an EPE approach, since the different organizational structures and their power regimes influence the mode of governmentality in society, determining the potential for progress or inertia. Most prominently the transition from the disciplinary to the control society was very exemplary shown by Deleuze (Citation1993, pp. 254–262) who elaborated on the following contradictions: “closure and opening”, “analogous and numeric language”, “factory and enterprise”, “individual and dividual” as well as “energy and information”. Gilles Deleuze has argued that the old sovereign societies dealt with simple “mechanical machines”, the youngest disciplinary societies dealt with “energetic machines” and the newest control societies operate with machines of a third type, i.e. “information machines” (Deleuze, Citation1993, pp. 254–262). This notion guides us directly from power to the formal language structures governing its discourses, i.e. the methods.

5. Methods

In the second half of the twentieth century new interesting methods—building upon the information machine—were developed to meet the demands of progressive modes of regulation (e.g. Leon Hurwicz’ “mechanism design”, (Hurwicz, Citation1973) as well as the consideration of agents’ internal model building (e.g. John von Neumann’s “game theory” and the “theory of automata” (Neumann, Citation1928, Citation1966); compare also Hanappi(Citation2013b) and Leonard (Citation2010) for a detailed history of game theory. However mostly unrecognized by mainstream economic theory a revolution of methodical as well as methodological possibilities took place. New language structures move beyond the scope of equilibrium concepts imprisoned in Newtonian mechanics and are largely connected to computational simulation. It is thereby not a coincidence that formal language moved from prose (classical political economy) to mathematics (neoclassical economics) and eventually to algorithmic science (EPE). We have illustrated the different categories in Table .

Table 1. Language structures (Hanappi, Citation2007).

Beinhocker (Citation2007, p. 293) addresses the notion of economic evolution as algorithmic and synthetic where “…instructions bind Physical Technologies and Social Technologies together into modules under a strategy”. Satisficing rules (Simon, Citation1987) enforce agents to collaborate and create but also contradict nested modules in large networks. Modelling such agent properties and the corresponding initialization of their systemic environment is necessary to develop a complex adaptive system. It is suggested to follow a computational approach that moreover allows the generation of nestedness in complex hierarchical terms (Simon, Citation1962). In particular we want to emphasize prospects of the bottom-up or agent-based approach in computational economics (see Velupillai et al., Citation2011 for an overview of different approaches in computable economics). The agent-based methodology opened a new spectrum of analytical endeavour that emphasizes the generative aspects of modelling actors instead of factors in computational social science (Epstein, Citation2006). Miller and Page (Citation2007) explain that the scope of bottom-up simulation can be a game changer for analysing transformation processes in society since it addresses the important role of time and space among other issues (Table ).

Table 2. Modelling potential of the bottom-up approach (Miller & Page, Citation2007, p. 79).

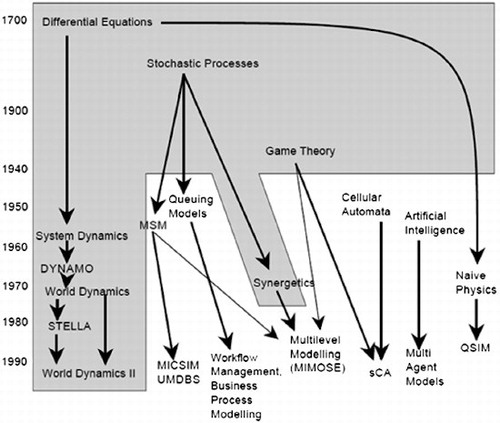

Simulation (Gilbert & Troitzsch, Citation2005, p. 5) allows particularly the investigation of emergence, “path-dependence, nonergodicity and cumulativity in processes of change” Elsner, Heinrich, and Schwardt (Citation2015, pp. 10–11). Nevertheless not every simulation technique is appropriate in this regard. Figure illustrates the development of simulation techniques and arranges them in two broad categories, where the grey-shaded area contains equation-based models and the white area contains either object, event or agent-based models. Among these techniques we find cellular automata and agent-based models that are suitable to simulate the aforementioned dynamics. Agent-based models fall under the category of multi-agent models with communication between multiple agents as well as a sufficient degree of complexity concerning the individual heterogeneous agent. A typical example for such a multi-agent model is given by the “Sugarscape” model developed by Epstein and Axtell (Citation1996, pp. 21–53). The model consists of resources as well as social rules and heterogeneous individual metabolisms. In its most basic form “Sugarscape” already implies meso behaviour, since the distribution of wealth develops endogenously by influencing the “cultural” behaviour of individual agents thereafter. This case becomes even more evident with particular extensions allowing the emergence of trade and credit networks (Epstein & Axtell Citation1996, pp. 94–137).

Figure 1. Development of different simulation techniques in the social sciences, Gilbert and Troitzsch (Citation2005, p. 7).

These methods wait for concrete simulation experiments as well as the creation of real-utopian visions in EPE, because they allow a proper treatment of core EPE concepts such as knowledge, power and social class through the generative approach.Footnote 18 In the literature we find several examples of agent-based computational economics in the principal spirit of EPE. We highlight Elsner and Heinrich (Citation2011) or Wäckerle, Rengs, and Radax (Citation2014) in relation to institutional economics (compare Gräbner, Citation2015 for an overview), Janssen and Ostrom (Citation2006) or Safarzynska (Citation2013) in relation to ecological economics, Gilbert et al. (Citation2001) in relation to innovation economics and Fagiolo et al. (Citation2007) in relation to social policy. Dosi, Fagiolo and Roventini (Citation2010) present an agent-based macroeconomic model with a distinctive capital goods market and model the development of Schumpeterian innovative behaviour. Ciarli et al. (Citation2010) deliver an agent-based macroeconomic model that features both consumption and production on the micro level as well as income distribution and investigate structural change and growth thereby. Cincotti, Raberto, and Teglio (Citation2010) provide a similar framework with regard to scope and scale but highlight more the Minskian financial aspects of credit-driven investment and systemic risk. Rengs and Wäckerle (Citation2014) have particularly addressed the notion of Veblenian institutional consumption dynamics and its effects on firm organization in a political economy with social classes. Delli Gatti, Desiderio, Gaffeo, Cirillo, and Gallegati (Citation2011) provide otherwise a very detailed instruction into macroeconomics from the bottom-up.

The crisis created a scientific space of methodological opportunity motivated by frustration with hegemonic neoclassical economic theory (the economic theory of the ruling class) and it is this vacuum of adequate explanation that can get conquered by EPE with novel methods and a concretely defined object of investigation.

6. Conclusion

The proposal how to understand content and method of EPE given above—to call it a definition runs counter the evolutionary character of this scientific discipline—seems to be operational enough to guide future research. Of course, it is rather aspiring since in perspective EPE is promising to lead to a unified synthesis of all contemporary social sciences, it aims at being the future mainstream social science. In its critique of today’s more or less sophisticated set of mathematical exercises that proclaims to be mainstream economics our approach is not alone. In the last 40 years several (some call them ‘heterodox’) approaches have been emerging and it is necessary to position EPE vis-à-vis these attempts.Footnote 19 Moreover, to approach its content implies an adjustment of the existing formal apparatus of economics— or even the introduction of newly emerging tools- to be able to describe its phenomena. EPE is forced to participate in the revolution of formal tools of social sciences that currently takes place. That happens with the sciences of non-living systems since 200 years, it now starts to happen with the sciences of living systems. Out of the enormous amount of new formalisms that have mostly emerged from advances in information science and information technology, EPE has to select, collect and combine those techniques that seem to be most appropriate for its content. The feedback from the content will then allow for a progressive dialectic between content and formalization. This is already taking place and the global division of theoretical labour enabled by the internet is starting to create what Antonio Gramsci would have called a global organic intellectual (Gramsci, Citation1930). The research program sketched above therefore is part of a global process of emancipation in which emerging knowledge contributes to design the future. It is very urgent to push forward this research program since evolution works with suddenly necessary pushes, with metamorphosis and revolutions.

Notes

1 In the nineteenth century, Charles Darwin was adding evolutionary theory as a proper scientific activity to the already existing successful natural sciences. Though it first was focusing on biology, it nevertheless implied a new image of the human species.

2 Note that Erwin Schrödinger, one of the greatest scientists of his time, only dared to give his lecture ‘What is Life’ when he was already a well-established star in the scientific arena.

3 In an interesting parallel, Frank Wilczek recently highlighted the role that beauty plays in quantum theory, see (Wilczek, Citation2015).

4 This would dissolve beauty into the arbitrariness of the observing mass of human individuals.

5 German Idealist Thought, e.g. Kant, had reduced the experience of beauty to a special type of idle observation of an object possessing the property to be beautiful. To gain a sharper criterion for beautiful objects a fierce debate on the need to exclude all useful objects, all tools, from the domain of beautiful objects was emerging. But the question ‘What was to be considered as a tool?’ referred back to the observer—the observer ‘without interest in the object’ was invented. Aesthetics typically was conceptualized for the members of a ruling class to encompass their leisure time activities (compare Veblen, Citation1899/2009). This is in sharp contrast to the concept of aesthetics used here.

6 Compare Callebaut (Citation2005) for the unifying principle of modularity in development, morphology and evolution. Where Jablan , p. 259)(Citation2005, p. 259) shows in his “modularity of art” that “In a general sense, modularity is a manifestation of the universal principle of economy in nature: the possibility of diversity and variability of structures resulting from some (finite and very restricted) set of basic elements by their recombination”. The module appears as an aesthetic concept in this regard, at the boundary between art and science (Buscalioni, de la Iglesia, Delgado-Buscalioni, & Dejaon, Citation2005).

7 Max Weber started a desperate attempt to ignore this essential difference by postulating a distinction between ‘objective statements’ and ‘normative statements’ that a social scientist has at his/her disposal. The ‘objective’ ones were meant to have the same status as natural laws, whereas the ‘normative’ ones were choices of the researcher based on individual attitudes or moral feelings. Despite the evident lack of scientific significance—see the arguments above—till today a considerable part of researchers in the natural sciences falls prey to Weber’s view.

8 All ‘isms’ that start with a ‘post-’ (post-modernism, post-Keynesianism, post-autism …) just express that they are helpless to name what they can offer. They thus have to use the name of what they pretend to have overcome, and timidly add the pre-fix ‘post’ since their property to be later is their only raison d’être. Usually they are just minor updates or downgrades of the original. EPE is firmly rooted in modernity.

9 The existence of different schools of economic theory is not just an indicator of a premature state of this science, it also reflects the fact that each social scientist is part of a specific social class. E.g. Keynes’ theory implicitly accuses the class of rentiers while trying to save fragile finance capitalism from collapse with the help of the state faction of the ruling class. Keynes was personally involved in stock exchange activities.

10 The concept ‘finite dynamics‘ shall indicate that these dynamics include entry and exit of variables, i.e. the property of variables to be essential for the dynamics is finite. To determine the set of variables sometimes has been considered as ‘qualitative research’, while the development of the quantities that a set of variables is assuming has been labelled ‘quantitative research’. Evolutionary theory embraces the pulsation of the alternation of both.

11 Today econophysics is so attractive for economists because it at least provides formalisms of up-to-date theoretical physics to be applied in economics. Every newly emerging field, like EPE, should be eager to incorporate appropriate innovative language elements.

12 Entropy can be understood as a measure of how similar a certain set of properties (e.g. speed and average free path length) of elements (e.g. molecules) within a system (e.g. a gas in a vessel) is. What happens in the short-run remains in the dark of murky and complicated non-linear dynamic systems theory, but in the long-run the stochastic law of increasing entropy drives the set of properties to the same average values. The situation towards which the system converges clearly reminds on the assumption of the ‘representative firm’ in standard microeconomics.

13 Already half a century ago Henri Theil had used this long-run averaging tendency to construct measures for economic inequality in distribution (Theil, Citation1967). In this context the stochastic long-run tendency towards increasing entropy postulated in physics can be understood as a tendency towards equalization of incomes in political economy. Might this be a stochastic, long-run measure of progress?

14 Darwin’s view was a stark provocation of Christian ideology: He postulated that the progressive order of systems of species are self-generated by these systems, a clear contradiction to the Christian dogma that the human species alone is on a long-run trail of catharsis to become ideal, i.e. the mirror image of God—and that this investigation is the central topic of science. Since Darwin knew how dangerous his work was for the Christian dogma, he delayed the publication of his book for more than 10 years. But even more important is that—like Marx with whom he had a friendly correspondence—Darwin recognized that it is typical for changes from one step to the next that this metamorphosis occurs in a relatively short time span. In Marx famous formulation: Revolutions are the fast trains of history (‘Revolutionen sind die Schnellzüge der Geschichte’).

15 Compare in this context the concept of ‘punctuated equilibria’ used by Per Bak (Bak & Sneppen, Citation1993) It was developed somewhat earlier by Stephen J. Gould (Eldridge & Gould, Citation1972).

16 A word becomes a concept if it proves its impact on the world outside language.

17 This statement derives the position of EPE as a part of evolutionary theory using an evolutionary argument. It is named ‘political economy’ since it treats processes of direct exertion of power (politics) as intrinsically interwoven with economic processes embedded in such a political setting. Note that this view is shared with the classical British authors of the nineteenth century. Keynes macroeconomics is only a pale shadow of this much broader approach.

18 In this context Hanappi proposed to understand capitalism as a particular algorithm, the capitalist algorithm, a reframing of the historical discourse into a language that is easily amenable to agent-based simulation (compare [Hanappi, Citation2013a]).

19 To highlight differences to the mainstream approach see (Hanappi, Citation2014), this also is implicitly done in the previous parts of this paper; compare also (Fine, Citation2013).

References

- Bak, P. , & Sneppen, K. (1993). Punctuated equilibrium and criticality in a simple model of evolution. Physical Review Letters , 71 , 4083–4086.10.1103/PhysRevLett.71.4083

- Beinhocker, E. D. (2007). The oirigin of wealth. Evolution, complexity and the radical remaking of economics . London: Random House Business Books.

- Boyer, R. (2000). Is a finance-led growth regime a viable alternative to Fordism? A preliminary analysis Economy and Society , 29 , 111–145.

- Buscalioni, A. D. , de la Iglesia, A. , Delgado-Buscalioni, R. , & Dejaon, A. (2005). Modularity at the boundary between art and science. In W. Callebaut & D. Rasskin-Gutman (Eds.), Modularity: Understanding the development and evolution of natural complex systems (pp. 283–304). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Callebaut, W. (2005). The ubiquity of modularity. In W. Callebaut & D. Rasskin-Gutman (Eds.), Modularity: Understanding the development and evolution of natural complex systems (pp. 1–28). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Castells, M. (2009). Communication power . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ciarli, T. , Lorentz, A. , Savona, M. , & Valente, M. (2010). The effect of consumption and production structure on grwoth and ditribution. A micro to macro model. Metroeconomica , 61, 180–218.

- Cincotti, S. , Raberto, M. , & Teglio, A. (2010). Credit money and macroeconomic instability in the agent-based model and simulator Eurace. Economics: The Open-Access, Open-Assessment E-Journal , 4 , 2010–2026.

- Colletti, L. , (1975). Marxism and the dialectic. New Left Review I/93 .

- Darwin, C. (1859). On the origin of species . London: John Murray.

- Deleuze, G. (1993). Unterhandlungen [Negotiations]: 1972–1990. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

- Delli Gatti, D. , Desiderio, S. , Gaffeo, E. , Cirillo, P. , & Gallegati, M. (2011). Macroeconomics from the bottom-up . Berlin: Springer.10.1007/978-88-470-1971-3

- Dosi, G. , Fagiolo, G. , & Roventini, A. (2010). Schumpeter meeting Keynes: A policy-friendly model of endogenous growth and business cycles. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control , 34, 1748–1967.

- Dosi, G. , Fagiolo, G. , Napoletano, M. , & Roventini, A. (2013). Income distribution, credit and fiscal policies in an agent-based Keynesian model. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control , 37 , 1598–1625.10.1016/j.jedc.2012.11.008

- Eldridge, N. , & Gould, S. (1972). Punctuated equilibria: an alternative to phyletic gradualism. In T. J. M. Schopf (Ed.), Models in paleobiology (pp. 82–115). San Francisco, CA: Freeman, Cooper & Co.

- Elsner, W. , & Heinrich, T. (2011). Coordination on “meso”-levels: On the co-evolution of institutions, networks and platform size. In S. Mann (Ed.), Sectors matter! Exploring mesoeconomics (pp. 115–163). Berlin: Springer.10.1007/978-3-642-18126-9

- Elsner, W. , Heinrich, T. , & Schwardt, H. (2015). The microeconomics of complex economies: Evolutionary, institutional, neoclassical, and complexity perspectives . Oxford: Academic Press an imprint of Elsevier.

- Epstein, J. (Ed.). (2006). Generative social science. Studies in Agent-Based Computational Modeling . Princeton/Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Epstein, J. & Axtell, R. (1996). Growing artificial societies. Social science from the bottom up. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Fagiolo, G. , Valente, M. , & Vriend, N. J. (2007). Segregation in networks. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization , 64, 316–336.

- Fine, B. (2013) Economics—Unfit for purpose: The director’s cut (SOAS Department of Economics Working Paper Series, No. 176). London: The School of Oriental and African Studies.

- Foucault, M. (1974/2004). Geschichte der Gouvernmentalität [Foucault M. The Courage of Truth : Lectures at the Collège de France 1983-1984, Foucault M. The Birth of Biopolitics Lectures At The College de France 1978-1979] (Vols. 2). Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

- Galbraith, J. K. (1967). The new industrial state . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Galbraith, J. K. (1973). Power and the useful economist. American Economic Review , 63 (1), 1–11.

- Georgescu-Roegen, N. (1971). The entropy law and the economic process . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.10.4159/harvard.9780674281653

- Gilbert, N. & Troitzsch, K. G. (2005). Simulation for the social scientist . New York: Open University Press.

- Gilbert, N. , Pyka, A. & Ahrweiler, P. (2001). Innovation networks – A simulation approach. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation , 4 (3).

- Gräbner, C. (2015). Agent-based computational models—A formal heuristic for institutionalist pattern modelling? Journal of Institutional Economics , 12 , 241–261. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137415000193 10.1017/S1744137415000193.

- Gramsci, A. (1930/1999) Prison notebooks. In Further selections from the Prison notebooks . London: Electric Book Company.

- Gruchy, A. G. (1973). Law, politics, and institutional economics. Journal of Economic Issues , 7 , 623–643.10.1080/00213624.1973.11503138

- Hanappi, H. (2007) On the nature of knowledge ( MPRA Paper No. 27615), Munich Personal RePEc Archive, Munich.

- Hanappi, H. (2013a). Money, credit, capital, and the state, on the evolution of money and institutions. In G. Buenstorf , U. Cantner , H. Hanusch , M. Hutter , H.-W. Lorenz , F. Rahmeier , (Eds.), The two sides of innovation: Economic Complexity and Evolution (pp. 255–281). Springer, Heidelberg and New York.10.1007/978-3-319-01496-8

- Hanappi, H. (2013b). The Neumann-Morgenstern project. In H. Hanappi (Ed.), Game theory relaunched . Intech publishers. Retrieved from http://www.intechopen.com/books/game-theory-relaunched

- Hanappi, H. (2014). Bridges to Babylon. Critical economic policy: From Keynesian macroeconomics to evolutionary macroeconomic simulation models. In L. Mamica & P. Tridico (Eds.), Economic policy and the financial crisis (pp. 13–39). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hurwicz, L. (1973). The design of mechanisms for resource allocation. AER , 63 (2), 1–30.

- Jablan, S. V. (2005). Modularity in art. In W. Callebaut & D. Rasskin-Gutman (Eds.), Modularity: Understanding the development and evolution of natural complex systems (pp. 259–282). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Janssen, M. , & Ostrom, E. (2006). Governing social-ecological systems. In K. L. Judd & L. Tesfatsion (Eds.), Handbook of Computational Economics II: Agent-Based Computational Economics (pp. 1465–1509). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Laclau, E. , & Mouffe, C. (1985/2014). Hegemony and socialist strategy: Towards a radical democratic politics (2nd ed.). London: Verso.

- Leonard, R. (2010). Von Neumann, Morgenstern, and the creation of game theory . Cambridge (US): Cambridge University Press, New York.10.1017/CBO9780511778278

- Lipietz, A. (1992). Towards a new economic order: Postfordism, ecology and democracy . London, Cambridge (UK): Polity Press.

- Marx, K. (1867/2001). Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Ökonomie. Band 1: Der Produktionsprozeß des Kapitals [Capital: A critique of political economy. Vol 1] . 20. Auflage, Marx-Engels-Werke Band 23. Berlin: Dietz Verlag.

- Miller, J. H. , & Page, S. E. (2007). Complex adaptive systems: An Introduction to computational models of social life . Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Mouffe, C. (2000/2009). The democratic paradox . London : Verso.

- Neumann, J. (1928). Zur Theorie der Gesellschaftsspiele [On the Theory of Parlor Games]. Mathematische Annalen , 100 , 295–320.

- Neumann, J. (1966). Theory of self-reproducing automata edited and completed by Arthur W. Burks Urbana and London: University of Illinois Press.

- Rengs, B. , & Wäckerle, M. (2014). A computational agent-based simulation of an artificial monetary union for dynamic comparative institutional analysis. Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computational Intelligence for Financial Engineering & Economics (CIFEr, London) (pp. 427–434). doi:https://doi.org/10.1109/CIFEr.2014.6924105

- Safarzynska, K. (2013). The coevolution of culture and environment. Journal of Theoretical Biology , 322 , 46–57.

- Scholz-Wäckerle, M. (2016). Democracy evolving: A diversity of institutional contradictions transforming political economy. Journal of Economic Issues , 50 , 1003–1026.

- Schrödinger, E. (1944). What is life? The physical aspect of the living cell . MacMillan. Retrieved from whatislife.stanford.edu/LoCo_files/What-is-Life.pdf

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1934/2012). The theory of economic development . New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1954/1994). History of Economic Analysis . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Simon, H. A. (1962). The architecture of complexity. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society , 106 , 467–482.

- Simon, H. A. (1987). Satisficing. In J. Eatwell , M. Millgate , & P. Newman (Eds.), The new Palgrave dictionary of economics (Vol. 4, pp. 243–245). New York, NY : Stockton Press.

- Smith, E. , & Foley, D. (2002). Classical thermodynamics and economic general equilibrium theory ( Working Paper of the Santa Fe Institute), SFI, Santa Fe (NM, USA).

- Tabb, W. K. (2010). Financialization in the contemporary social structure of accumulation. In T. McDonough , M. Reich , & D. Kotz (Eds.), Contemporary capitalism and its crises. Social structure of accumulation theory for the 21st century (Vol. 4, pp. 243–245). Cambridge University Press.

- Theil, H. (1967). Economics and information theory . Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishers.

- Toporowski, J. (2010). The transnational company after globalisation. Futures , 42 , 920–925.10.1016/j.futures.2010.08.025

- Veblen, T. (1899/2009). The theory of the leisure class . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Velupillai, K. V. , Zambelli, St. , & Kinsella, St. (Eds.) (2011). The Elgar Companion to Computable Economics. Edward Elgar Publications: Cheltenham, Gloucestershire.

- Wäckerle, M. , Rengs, B. , & Radax, W. (2014). An agent-based model of institutional life-cycles. Games , 5 , 160–187.10.3390/g5030160

- Wilczek, F. (2015). A beautiful question: Finding nature’s deep design . New York: Penguin Press.