Abstract

Women with pelvic floor complaints experience restrictions and distress in their daily, social, and sexual functioning, and their intimate relationships. We interviewed forty-eight women to unravel differences between women receiving and not receiving pelvic physical therapy and between pregnant, parous, and nulliparous women in preparation for theory development. We analyzed data in a mixed-method design using NVivo and Leximancer. Sexual dysfunction, relationship dynamics, the nature and severity of restrictions and distress, and coping strategies appear to vary between women receiving and not receiving therapy. Specific combinations of restrictions and distress are present in pregnant, parous, and nulliparous women, and might influence women’s decision to seek help.

After performing an initial literature review on restrictions and distress that women with pelvic floor complaints (PFC) experience, we decided to qualitatively explore and quantitatively analyze data from interviews with pregnant, parous, and nulliparous women with PFC who did and did not receive pelvic physical therapy (PPT). The initial literature review provided a fragmented overview of this topic. Moreover, the results of previous research were mostly based on quantitative research methods. In this study, we aimed to clarify the most important restrictions and distress that different groups of women with PFC experience in their daily, social, and sexual functioning and their intimate relationships, based on their personal experiences. In addition, we aimed to explore differences in restrictions and distress that might provide suggestions for why some women seek help and others do not. Furthermore, we intended to use the outcomes of this study as input for conceptualization and theory development in follow-up research that may help to better inventory restrictions and distress in women with PFC.

Background

PFC, such as pelvic organ prolapse, urinary, and fecal incontinence, and pain complaints in the lower abdomen, pelvis, and its surrounding region are common in young adult women (Bazi et al., Citation2016; Elneil, Citation2009; Stuge et al., Citation2012; Wang et al., Citation2012; Yount, Citation2013). The prevalence of various complaints varies greatly (between 5-50%), and varies also with pregnancy and childbirth. PPT services are available worldwide as presented on the website of the International Organization of Physical Therapists in Pelvic and Women’s Health. Despite the availability of these services, few women with PFC seek help (Buurman & Lagro-Janssen, Citation2013; Yount, Citation2013).

Women with PFC often experience restrictions and distress in their daily, social, and sexual functioning and intimate relationships. Typically, women’s daily performance (Stomp-van den Berg et al., Citation2012) and social activities can be limited when their ability to sit, walk, run and jump is hampered (Bazi et al., Citation2016; de Mattos Lourenco et al., Citation2018). Subsequently, women tend to alter their lifestyles and adapt their activities (Lopes et al., Citation2018; Yount, Citation2013). Sexual functioning is challenged because women tend to be less sexually active and avoid sexual interaction (Andreucci et al., Citation2015; Elneil, Citation2009; Leclerc et al., Citation2015; Lopes et al., Citation2018; Yount, Citation2013), which negatively affects their intimate relationships (Bergeron et al., Citation2014; Bond et al., Citation2012; Leclerc et al., Citation2015; Rosen & Bergeron, Citation2019; Rowland & Kolba, Citation2018; Sadownik et al., Citation2017; Shallcross et al., Citation2018).

Women with PFC experience various types of distress which tend to vary with or depend on pregnancy and childbirth (Buurman & Lagro-Janssen, Citation2013; Skinner et al., Citation2018). Parous women report feeling worried, embarrassed, stressed, frustrated, and insecure because of their complaints (Cichowski et al., Citation2014; Jawed-Wessel et al., Citation2017; Lopes et al., Citation2018; Yount, Citation2013). They often regret the lack of information given about possible postpartum complaints (Wuytack et al., Citation2015). Pregnant women’s intimate relationships change when they feel distressed about becoming more dependent on others for support (Rosand et al., Citation2011).

Specific complaints tend to induce different types of distress. Pain induces feelings of anger, anxiety, and depression (Bergeron et al., Citation2014; Mackenzie et al., Citation2018; Melotti et al., Citation2018; Piontek et al., Citation2019; Vrijens et al., Citation2017; Witting et al., Citation2008). Pelvic organ prolapse, genito-pelvic pain, and incontinence induce body image issues (Bergeron et al., Citation2014; Bond et al., Citation2012; Handelzalts et al., Citation2017; Leclerc et al., Citation2015; Lowder et al., Citation2011; Rosen & Bergeron, Citation2019), which make women feel sexually unattractive (Witting et al., Citation2008; Yount, Citation2013), and more self-conscious. The latter negatively affects their intimate relationships (Van Lankveld et al., Citation2008; Citation2010; Van Lankveld & Bergh, Citation2008).

In conclusion, these findings suggested that the types and severity of restrictions and distress, and the way women cope may differ between women who do and do not seek help, and with pregnancy and childbirth. In this study, we aim to obtain an overview of the restrictions and distress in different groups of women with PFC. Furthermore, we aim to gather input for conceptualization and theory development on this topic.

Material and methods

Study design

In this mixed-method research, we used a qualitative, exploratory, cross-sectional design, combining classical qualitative data collection and quantitative analyses techniques to obtain more powerful, valid, and reliable outcomes. A semi-structured interview with extensive and appropriate topic-related and mainly open questions served as the primary data collection method for which we needed approximately 30 to 60 participants to produce reliable outcomes (Weller et al., Citation2018). The interview is available as a supplemental file (Supplementary material Appendix 1, Semi-structured Interview).

Procedure

The Ethics Review Board of the Open University of The Netherlands approved the study protocol in May 2019. The main researcher piloted the interview and we added a critical incident question about the most memorable situation that women ended up in because of their PFC. Subsequently, we recruited, included, and interviewed women, as shown in .

Table 1. Research participant recruitment, in- and exclusion criteria, demographics, and interview circumstances.

Data collection

All participants received information about the study via email before they were interviewed by the first author at a convenient time and place depending on geographical distance, mobility, preference, and the Covid-19 pandemic. To avoid bias, a colleague pelvic physical therapist from a different practice interviewed the participants from the principal researcher’s practice (see ). Before the interview, participants read and signed an informed consent form, agreeing to the audio recording of the interview, and the use of their narrative for analysis. The duration of the interviews was 45 to 80 minutes, with an average of 60 minutes. Participants were interviewed between June 2019 and May 2020.

The principal researcher transcribed the interviews verbatim, following the classical principles of qualitative research (Malterud, Citation2001; Twining et al., Citation2017) into anonymous transcripts. Subsequently, all participants received the transcript of their interview and were asked to complete a 5-item online questionnaire, in which they rated the transcript’s authenticity and completeness on a 10-point scale. Higher scores indicated higher accuracy. In addition, they rated the clarity of information before participation, their level of experienced ease during the interview, and their satisfaction with participation. Higher scores indicated more positive experiences.

Data analytic plan

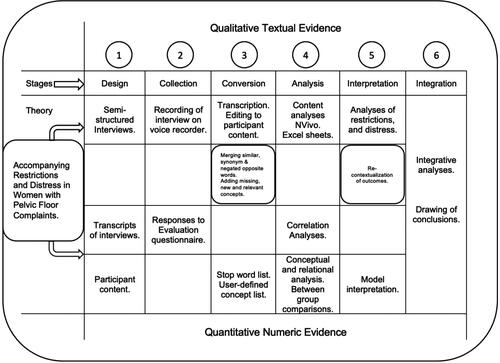

We used NVivo (NVivo, Citation2018) for coding the data and to help organize ideas. In addition, we used the text mining program Leximancer (Leximancer, Citation2019) to accomplish a quantitative approach and to provide clear visual pictures of major themes and their reciprocal relationships in and between groups (Sotiriadou et al., Citation2014). We edited the transcripts into participant content only before coding the data, as is shown in .

Table 2. Editing of full transcripts into participant content.

During the analysis of the edited transcripts, we prepared a concept list with relevant restrictions and types of distress for analyses in Leximancer. In addition, daily, social, and sexual functioning and intimate relationships were conceptualized. Then we uploaded the edited transcripts into the program and tested and adapted the list. The final list contained 57 concepts. We translated it into English for inclusion in this article (see ). To keep the concept names as short as possible, we called daily, social, and sexual functioning problems “dysfunction,” and problems in intimate relationships “issues.”

Table 3. Overview of the concepts in Leximancer.

Subsequently, we prepared sub-group projects in Leximancer and ran identical analyses in each project to be able to compare outcomes. Outcomes were depicted in concept maps that we adapted for clarity purposes to present a maximum of ten themes per project. An overview of the applied mixed-method methodology is shown in . SPSS-26 was used for correlation analyses.

Results

We recorded, transcribed, and analyzed 48 interviews. An overview of participants’ attributes is included in . The prevalence and types of pelvic floor complaints, as well as menstrual influence on complaints, are depicted in .

Table 4. Reported pelvic floor complaints.

During the interview transcription, a sense of data saturation grew and when no new items appeared in the coding process, recruitment was terminated. The evaluation questionnaire on transcript accuracy was completed by 39 out of 48 participants. The reliability of the authenticity and completeness items of the evaluation questionnaire was excellent, with Spearman’s rho = .88 (Eisinga et al., Citation2012).

The outcomes of the text mining analysis

We integrated the concept maps that provide a visual representation of the most important domains, restrictions, and distress of the total group and subgroups of participants into Table 5 that we added as a supplemental file for interested readers to clarify and support the content in the table. In different groups, distinct patterns of themes and new themes emerged. In general, sexual and daily functioning were the domains that were the most challenged. Restrictions were not always important topics of discussion, and distress appeared more severe in women who received PPT, and in parous women. In some groups of women, the expressed types of distress might explain why these women did not seek help. During the interviews we asked the participants why they sought help, and if not, why not, because in principle, PPT services were available for all participants in this study (Supplementary material Appendix 2, Table S1).

Discussion

We aimed to create an overview of women with PFCs’ restrictions and distress in their daily, social, and sexual functioning, and intimate relationships and to gather input for future theory development. In addition, we compared the restrictions and distress of women who did and did not receive PPT to better understand why some women seek help from a pelvic physical therapist, and others do not. Finally, we compared restrictions and distress in the six subgroups of participants gaining more in-depth insight into specific subgroup differences.

General outcomes and correspondence with previous research

In line with previous research findings, daily functioning was challenged in nearly all subgroups (Bazi et al., Citation2016; Stomp-van den Berg et al., Citation2012; Wuytack et al., Citation2015). In addition, similar to previous findings (Andreucci et al., Citation2015; Elneil, Citation2009; Leclerc et al., Citation2015; Lopes et al., Citation2018; Yount, Citation2013) participants’ sexual functioning was often negatively affected, showing a decline in sexual pleasure and restraints to engage in sexual intercourse. Some participants preferred masturbation over partnered sex for having full control over their sexual pleasure, and to avoid pain. However, masturbation was not common practice among all participants. Some were worried to deprive their partners, whilst others reported an increased desire for partnered sex with masturbation. Uncomfortable partnered sex and the inability to live up to their partners’ sexual wishes often cause relationship issues among participants as well as other women (Elneil, Citation2009; Leclerc et al., Citation2015; Lopes et al., Citation2018; Sadownik et al., Citation2017; Shallcross et al., Citation2018; Yount, Citation2013). In contrast to the social restrictions described in previous studies (Lopes et al., Citation2018; Yount, Citation2013), the most troublesome aspect of our participants’ social functioning was their engagement in sports (de Mattos Lourenco et al., Citation2018; Nygaard & Shaw, Citation2016). Another contrasting finding was that anger, anxiety, and depression (Bergeron et al., Citation2014; Mackenzie et al., Citation2018; Melotti et al., Citation2018; Piontek et al., Citation2019; Vrijens et al., Citation2017; Witting et al., Citation2008) were not common among all participants, although they were reported in some subgroups. Disappointment, however, was frequently mentioned and was not reported in previous studies. Other researchers mainly describe partner disappointment with women’s sexual dysfunction, and disappointment with PFC-related diagnostic and treatment outcomes (Rosand et al., Citation2011).

Why some women received PPT and others did not

Sexual dysfunction was common in participants who received PPT, whereas intimate relationship issues were prioritized in those who did not receive PPT. Moreover, relational distress is not a criterion for PPT. The only restriction important enough to qualify for therapy was serious walking problems. Furthermore, participants who received PPT reported more overwhelming distress in comparison to women who did not receive PPT. In line with findings of previous researchers, distress such as anger (Mackenzie et al., Citation2018), and body image issues (Bergeron et al., Citation2014; Bond et al., Citation2012; Handelzalts et al., Citation2017; Leclerc et al., Citation2015; Lowder et al., Citation2011; Rosen & Bergeron, Citation2019) were common in participants who received PPT. The finding that participants who did not receive PPT felt proud about their coping strategies without receiving help suggests that this might be a decisive factor in women’s choice not to seek help. The findings in this study suggest that a strong wish to resolve sexual dysfunction, a higher level of psychological burden, and differences in coping style might constitute determinants of the decision to consult a pelvic physical therapist.

The associations between pregnancy and childbirth and PFC-related restrictions and distress

In pregnant women, relationship quality is known to affect distress levels (Rosand et al., Citation2011; Witting et al., Citation2008). In this study, the distress that pregnant participants experienced appeared consistent with the changes in their bodies and their relationships. Parous and nulliparous participants emphasized the importance of a satisfactory sex life for different reasons. Similar to parous women in previous studies, our participants reported that pelvic floor damage from childbirth often challenged their sexual functioning and intimate relationships (Andreucci et al., Citation2015; Bazi et al., Citation2016; Brand & Waterink, Citation2018; Lopes et al., Citation2018; Yount, Citation2013). Some participants disclosed to even (temporarily) having hated their child for causing (undeliberately) their complaints; a conspicuous and understudied finding (O’Reilly et al., Citation2009). In line with previous findings (Witting et al., Citation2008), nulliparous women’s sexual functioning tends to define their relationship quality, and sexual dysfunction might jeopardize their intentions to become pregnant. In comparison, parous participants’ distress seems more overwhelming than pregnant and nulliparous participants’ distress (Skinner et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, many parous and nulliparous participants reported experiencing an increase in pain, incontinence, or aggravated sense of pelvic organ prolapse before or during menstruation. This phenomenon appears to be common, but research on this topic has thus far been limited (Righarts et al., Citation2018).

The associations between pregnancy and childbirth, and receiving PPT or not

Compared with other subgroups, pregnant participants who waddled and felt dependent more often received PPT. Their distress suggests more problems coping in comparison to pregnant participants who did not receive PPT. Childbirth jeopardized participants’ sexual and social functioning similar to previous findings (Cichowski et al., Citation2014; Yount, Citation2013). Its physical impact and severe and overwhelming distress, such as depressive feelings and anger constituted motivation for PPT in both groups of women (Bergeron et al., Citation2014; Mackenzie et al., Citation2018; Vrijens et al., Citation2017). The disappointment of parous participants who did not receive PPT makes it questionable whether it is a motivator to seek help. The distress expressed by nulliparous participants who did receive PPT suggests a lack of control and insufficient coping, whereas the distress types and the fact that women not receiving PPT felt proud about their way of coping may well explain why they refrain from seeking help. Our results show at a deeper level that the pregnant, parous, and nulliparous participants, who did and did not receive PPT, experience different restrictions and distress in different domains of their lives.

Limitations

The first limitation concerns the Leximancer program. It proved challenging to include negated restrictions and distress, e.g. “not frustrated” and their inclusion contaminated the results. They were excluded when exclusion did not change the outcomes of the analyses. Furthermore, the human input that Leximancer requires could introduce bias by content familiarity and qualitative judgment influencing accurate output interpretation. Finally, repeated analyses resulted in slight concept map changes, which is inherent to the functionality of the Leximancer concept layout generator.

The second limitation is that, notwithstanding the participants’ willingness and openness, they may not have fully disclosed all topics, and some questions remained (partly) unanswered. Despite this limitation and the relatively small group of participants, the collected data was rich. More objective between-group comparisons were possible based on quantitative text-mining analyses. Results may be seen as indicative of between-group differences that need further exploration.

Thirdly, we did not question women about any previous miscarriages, disregarding their possible impact on women’s distress during pregnancy and around childbirth. In some interviews, women revealed this information spontaneously. Furthermore, some women spontaneously disclosed negative sexual experiences, including sexual harassment. If we had questioned all participants on this topic, the prevalence of these negative sexual experiences might have been higher.

Future research

Several interesting follow-up questions emerged that could be explored in future studies. To begin with, it may be crucially important to further investigate differences in challenged domains, the severity of restrictions and distress, and coping styles in all six subgroups of participants to gain more insight into context-related reasons to seek help from a pelvic physical therapist or not. Outcomes might improve the information for women, help pelvic physical therapists to provide more adequate care and support, and enhance collaboration with other health care professionals. In addition, women’s disappointment, and its role in wanting PPT or not needs further exploration. Secondly, the burden of sexual dysfunction could be further investigated. More insight into women’s preference for, or abstinence from masturbation might help to improve professional care for women with pelvic floor complaints, who suffer from sexual dysfunction. In future studies, questions about miscarriages and negative sexual experiences should be added in interviews, to gain more insight into their possible confounding influence on women’s distress and pelvic floor complaints. Furthermore, exploration of relationship dynamics, and partner support, might also improve information, care, and support, for women with pelvic floor complaints. Finally, the conspicuous remarks from young mothers about feeling hatred toward their unborn or newborn children for being (not deliberately) responsible for their pelvic floor complaints is an interesting finding, that can inspire new research.

Conclusion

With this research, we initiated theory development on restrictions and distress in women with PFC in general, in women who did and did not receive PPT, and in pregnant, parous, and nulliparous women. We conclude that sexual dysfunction and overwhelming distress appear to be common in women with PFC who receive PPT. Disappointment is a prevalent feeling in women with PFC. Pregnancy-related complaints create distress in intimate relationships, whereas childbirth-related complaints are accompanied by severe and overwhelming distress, and many challenges in parous women’s sex life. The domains that were challenged and the nature of the experienced restrictions and distress in each group of women with PFC suggest the presence of different coping styles and different reasons to seek or not seek help from a pelvic physical therapist.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Review Board of the Open University of the Netherlands (Date: May 29th, 2019/No. U2019/03973/HVM).

Appendix_2__Table_5.pdf

Download PDF (4.2 MB)Appendix_1__Semi-Structured_Interview.pdf

Download PDF (102.2 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Betty van Vulpen for her contribution to the data collection, and all participants for sharing their experiences.

References

- Andreucci, C. B., Bussadori, J. C., Pacagnella, R. C., Chou, D., Filippi, V., Say, L., & Cecatti, J. G. (2015). Sexual life and dysfunction after maternal morbidity: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15(1), 307. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0742-6

- Bazi, T., Takahashi, S., Ismail, S., Bø, K., Ruiz-Zapata, A. M., Duckett, J., & Kammerer-Doak, D. (2016). Prevention of pelvic floor disorders: international urogynecological association research and development committee opinion. International Urogynecology Journal, 27(12), 1785–1795. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-2993-9

- Bergeron, S., Likes, W. M., & Steben, M. (2014). Psychosexual aspects of vulvovaginal pain. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 28(7), 991–999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.07.007

- Bond, K. S., Weerakoon, P., & Shuttleworth, R. (2012). A literature review on vulvodynia and distress. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 27(1), 46–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2012.664272

- Brand, A. M., & Waterink, W. (2018). The extent of incurred pelvic floor damage during a vaginal birth and pelvic floor complaints. International Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 6(3), 470–475. https://doi.org/10.4172/2329-9096.1000470

- Buurman, M. B. R., & Lagro-Janssen, A. L. M. (2013). Women’s perception of postpartum pelvic floor dysfunction and their help-seeking behaviour: a qualitative interview study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 27(2), 406–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01044.x

- Cichowski, S. B., Dunivan, G. C., Rogers, R. G., & Komesu, Y. M. (2014). Patients’ experience compared with physicians’ recommendations for treating fecal incontinence: a qualitative approach. International Urogynecology Journal, 25(7), 935–940. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-013-2322-5

- de Mattos Lourenco, T. R., Matsuoka, P. K., Baracat, E. C., & Haddad, J. M. (2018). Urinary incontinence in female athletes: a systematic review. International Urogynecology Journal, 29(12), 1757–1763. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3629-z

- Eisinga, R., Grotenhuis, M. t., & Pelzer, B. (2012). The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown? International Journal of Public Health, 58(4), 637–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-012-0416-3

- Elneil, S. (2009). Complex pelvic floor failure and associated problems. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Gastroenterology, 23(4), 555–573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2009.04.011

- Handelzalts, J. E., Yaakobi, T., Levy, S., Peled, Y., Wiznitzer, A., & Krissi, H. (2017). The impact of genital self-image on sexual function in women with pelvic floor disorders. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 211, 164–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.02.028

- Jawed-Wessel, S., Herbenick, D., & Schick, V. (2017). The relationship between body image, female genital self-image, and sexual function among first-time mothers. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 43(7), 618–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2016.1212443

- Leclerc, B., Bergeron, S., Brassard, A., Bélanger, C., Steben, M., & Lambert, B. (2015). Attachment, sexual assertiveness, and sexual outcomes in women with provoked vestibulodynia and their partners: A mediation model. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(6), 1561–1572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0295-1

- Leximancer. (2019). Leximancer quantitative data analysis software. Leximancer Pty Ltd.

- Lopes, M. H. B. d M., Costa, J. N. d., Bicalho, M. B., Casale, T. E., Camisão, A. R., & Fernandes, M. L. V. (2018). Profile and quality of life of women in pelvic floor rehabilitation. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 71(5), 2496–2505. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2017-0602

- Lowder, J. L. M. D. M., Ghetti, C. M. D., Nikolajski, C. M. P. H., Oliphant, S. S. M. D., & Zyczynski, H. M. M. D. (2011). Body image perceptions in women with pelvic organ prolapse: a qualitative study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 204(5), 441.e441–441.e445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.12.024

- Mackenzie, J., Murray, E., & Lusher, J. (2018). Women’s experiences of pregnancy related pelvic girdle pain: A systematic review . Midwifery, 56, 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2017.10.011

- Malterud, K. (2001). Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet (London, England), 358(9280), 483–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6

- Melotti, I. G. R., Juliato, C. R. T., Tanaka, M., & Riccetto, C. L. Z. (2018). Severe depression and anxiety in women with overactive bladder. Neurourology and Urodynamics, 37(1), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.23277

- NVivo. (2018). NVivo qualitative data analysis software. QSR International Pty Ltd.

- Nygaard, I. E., & Shaw, J. M. (2016). Physical activity and the pelvic floor. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 214(2), 164–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.067

- O’Reilly, R., Peters, K., Beale, B., & Jackson, D. (2009). Women’s experiences of recovery from childbirth: focus on pelvis problems that extend beyond the puerperium. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18(14), 2013–2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02755.x

- Piontek, K., Ketels, G., Albrecht, R., Schnurr, U., Dybowski, C., Brünahl, C. A., Riegel, B., & Löwe, B. (2019). Somatic and psychosocial determinants of symptom severity and quality of life in male and female patients with chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 120, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.02.010

- Righarts, A., Osborne, L., Connor, J., & Gillett, W. (2018). The prevalence and potential determinants of dysmenorrhoea and other pelvic pain in women: A prospective study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 125(12), 1532–1539. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15247

- Rosand, G. M. B., Slinning, K., Eberhard-Gran, M., Roysamb, E., & Tambs, K. (2011). Partner relationship satisfaction and maternal emotional distress in early pregnancy. Bmc Public Health, 11(1), 161–161. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-161

- Rosen, N. O., & Bergeron, S. (2019). Genito-pelvic pain through a dyadic lens: Moving toward an interpersonal emotion regulation model of women’s sexual dysfunction. Journal of Sex Research, 56(4-5), 440–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1513987

- Rowland, D. L., & Kolba, T. N. (2018). The burden of sexual problems: Perceived effects on men’s and women’s sexual partners. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(2), 226–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1332153

- Sadownik, L. A., Smith, K. B., Hui, A., & Brotto, L. A. (2017). The impact of a woman’s dyspareunia and its treatment on her intimate partner: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 43(6), 529–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2016.1208697

- Shallcross, R., Dickson, J. M., Nunns, D., Mackenzie, C., & Kiemle, G. (2018). Women’s subjective experiences of living with vulvodynia: A systematic review and meta-ethnography. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(3), 577–595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-1026-1

- Skinner, E. M., Barnett, B., & Dietz, H. P. (2018). Psychological consequences of pelvic floor trauma following vaginal birth: a qualitative study from two Australian tertiary maternity units. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 21(3), 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-017-0802-1

- Sotiriadou, P., Brouwers, J., & Le, T.-A. (2014). Choosing a qualitative data analysis tool: A comparison of NVivo and Leximancer. Annals of Leisure Research, 17(2), 218–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2014.902292

- Stomp-van den Berg, S. G. M., Hendriksen, I. J. M., Bruinvels, D. J., Twisk, J. W. R., van Mechelen, W., & van Poppel, M. N. M. (2012). Predictors for postpartum pelvic girdle pain in working women: The Mom@Work cohort study. Pain (Amsterdam), 153(12), 2370–2379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2012.08.003

- Stuge, B., Saetre, K., & Braekken, I. H. (2012). The association between pelvic floor muscle function and pelvic girdle pain-a matched case control 3D ultrasound study. Manual Therapy, 17(2), 150–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2011.12.004

- Twining, P., Heller, R. S., Nussbaum, M., & Tsai, C.-C. (2017). Some guidance on conducting and reporting qualitative studies. Computers & Education, 106, A1–A9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.12.002

- Van Lankveld, J. J. D. M., & Bergh, S. (2008). The interaction of state and trait aspects of self-focused attention affects genital, but not subjective, sexual arousal in sexually functional women. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(4), 514–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.01.017

- Van Lankveld, J. J. D. M., Geijen, W. E. H., & Sykora, H. (2008). The sexual self-consciousness scale: Psychometric properties. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37(6), 925–933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9253-5

- Van Lankveld, J. J. D. M., Granot, M., Weijmar Schultz, W. C. M., Binik, Y. M., Wesselmann, U., Pukall, C. F., Bohm-Starke, N., & Achtrari, C. (2010). Women’s sexual pain disorders. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(1 Pt 2), 615–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01631.x

- Vrijens, D., Berghmans, B., Nieman, F., van Os, J., van Koeveringe, G., & Leue, C. (2017). Prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms and their association with pelvic floor dysfunctions-A cross sectional cohort study at a Pelvic Care Centre . Neurourol Urodyn, 36(7), 1816–1823. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.23186

- Wang, Y.-C., Hart, D. L., & Mioduski, J. E. (2012). Characteristics of patients seeking outpatient rehabilitation for pelvic-floor dysfunction. Physical Therapy, 92(9), 1160–1174. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20110264

- Weller, S. C., Vickers, B., Bernard, H. R., Blackburn, A. M., Borgatti, S., Gravlee, C. C., & Johnson, J. C. (2018). Open-ended interview questions and saturation. PloS One, 13(6), e0198606. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198606

- Witting, K., Santtila, P., Alanko, K., Harlaar, N., Jern, P., Johansson, A., Von Der Pahlen, B., Varjonen, M., Ålgars, M., & Sandnabba, N. K. (2008). Female sexual function and its associations with number of children, pregnancy, and relationship satisfaction. J Sex Marital Ther, 34(2), 89–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926230701636163

- Wuytack, F., Curtis, E., Begley, C., Sahlgrenska, a., Göteborgs, u., Gothenburg, U., & Sahlgrenska, A. (2015). Experiences of first-time mothers with persistent pelvic girdle pain after childbirth: Descriptive qualitative study. Physical Therapy, 95(10), 1354–1364. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20150088

- Yount, S. M. (2013). The impact of pelvic floor disorders and pelvic surgery on women’s sexual satisfaction and function. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 58(5), 538–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.12030