Abstract

This study sets out to address a gap in research into teachers’ attitudes and opinions toward death education. To meet this objective, two complementary instruments were designed and validated: the Death Education Attitudes Scale-Teachers (DEAS-T), which showed suitable psychometric values, and the Death Education Questionnaire-Teachers (DEQ-T). The sample comprised 683 teachers from a range of schools. The results show moderately positive attitudes toward death education. Variables such as gender, age, type of teacher, and religious beliefs all influenced results. The findings argue in favor of the inclusion of death in education and teacher training.

The curricula established by our education systems set out objectives, contents, and assessment criteria for schools at all levels. However, there are topics that are a part of life and can affect schools which are not represented in the official curricula. One of these topics is death, which, although closely linked to history, art, biology, philosophy, health education, war, genocide, the life cycle, and the loss of biodiversity, is not encompassed in curriculum planning or granted any kind of educational value (Herrán et al., Citation2000, Citation2019; James, Citation2015; Rodríguez et al., Citation2020; Stylianou & Zembylas, Citation2018). Thus, the importance of the awareness of death is ignored in education, although international organisms such as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) recommend that schools should educate children for life (UNESCO, Citation2014, Citation2015). Yet how can we do this in a complete and meaningful way if death is not included in our teaching?

Death has a presence in schools and, therefore, in the whole education community. Nature and humanity demand that schools act as educators in various situations: when a student is affected by the death of a loved one; when topics touching on death are taught; when exceptional situations stemming from illness and death are experienced, such as, for example, natural disasters, terrorism, violence, and pandemics, such as that caused recently by the COVID-19 virus; or simply when a pupil asks a teacher a question about death. These situations are potentially educational because, through them, teachers can help their students to grow up in an environment where death is discussed normally, thus helping them live better, with more awareness and a greater sensitivity toward the entire phenomenon of life. However, at times, the social taboo on death is reflected in the school environment (Herrán et al., Citation2019), due to teachers’ own fears and attitudes toward dealing with the subject (Galende, Citation2015; Herrán et al., Citation2000), their lack of training in death education (Herrán et al., Citation2000; Holland, Citation2008) and the belief that children and adolescents cannot achieve an understanding of death (Schoen et al., Citation2004), amongst other reasons. Although death is inherent to the process of living, curriculums do not plan for the incorporation of death in disciplinary or transversal education, including skills (Herrán et al., Citation2019; Rodríguez et al., Citation2020); it is only dealt with reactively when it is unavoidable, in tragic circumstances or disasters (i.e., Stough et al., Citation2018).

In the light of this issue, it appears important to gather teachers’ views on death education, on the potential inclusion of death in the curriculum and in education in general, and on the need for pre- and in-service training in death education at the different levels of the system, from early childhood to secondary schools. The present study addresses this gap in the existing research on death education: the investigation of attitudes and opinions toward death education among teachers at all levels of educational, using validated instruments and a broad sample.

Death education

In the fields of health and social work, research into death education goes back to the 1920s (Rodríguez et al., Citation2019). At this time, the scientific and professional communities began to realize the need for specific training in death, designed for health professionals. The transference of death education to the educational sphere goes back to the 1980s, with the appearance of studies and proposals on normalizing death in schools (Rodríguez et al., Citation2019). Initially, death education was linked to preparation for loss and attention to students in situations of bereavement (i.e., Aspinall, Citation1996; Berg, Citation1978). Later, other approaches to death education emerged in various fields, such as the philosophy of education (Mèlich, Citation1989), pedagogy and didactics, curriculum studies, awareness-based education (Herrán et al., Citation2000), and education for life (Corr et al., Citation2019; Petitfils, Citation2016).

The latest developments in the field see death education as the area studied by the pedagogy of death. This is an area relating to teaching, learning, and research within a form of education for life that takes the awareness of death into account (Herrán et al., Citation2000; Herrán & Cortina, Citation2006). It includes two approaches: first, the curricular, which seeks to normalize death through what is taught and learnt; and second, the palliative, oriented toward counseling action by tutors in situations of bereavement.

Research into death education has advanced notably in recent years, with studies on the following topics: (a) the purposes of education (Mèlich, Citation1989); (b) different approaches to and aspects of how death may be taught, relating it to emotional education, the life cycle (Aspinall, Citation1996), education for life (Corr et al., Citation2019; Petitfils, Citation2016), socio-critical competence (Mantegazza, Citation2004), the curriculum, teaching methods, education for awareness (Herrán & Cortina, Citation2006; Herrán et al., Citation2000), and topics such as genocide and the Holocaust (Bos, Citation2014; Burtonwood, Citation2002; Lindquist, Citation2007; Zembylas, Citation2011); (c) teaching resources for death education (Herrán & Cortina, Citation2006; Herrán et al., Citation2000) such as the cinema (Cortina & Herrán, Citation2011), children’s literature (Colomo, Citation2016) and service learning (Rodríguez et al., Citation2015); (d) “partial” or “little deaths” (Dennis, Citation2009; Herrán et al., Citation2000); (e) counseling for bereavement in schools through tutorial action (Dyregrov et al., Citation2013; Herrán & Cortina, Citation2006; Herrán et al., Citation2000; Holland, Citation2008; Willis, Citation2002); and (f) the presence of death in the curriculum at the different levels of education (Herrán et al., Citation2000, Citation2019; James, Citation2015; Rodríguez et al., Citation2020; Stylianou & Zembylas, Citation2018).

Community’s perceptions of death and its potential inclusion in education have been investigated via the attitudes of students, families, and teachers. Research undertaken among students has centered on educational needs in the area of death as perceived by sixth-form students (Birkholz et al., Citation2004); pupils’ construct of death in early childhood (Vlok & de Witt, 2012), primary and secondary schools (Yang & Chen, Citation2006); and death education in university education (Harrawood et al., Citation2011). Some studies have also been carried out on perceptions of death education among families (Herrán et al., Citation2000; Jones et al., Citation1995; McGovern & Barry, Citation2000). The first (Jones et al., Citation1995), a study undertaken with a sample of 375 mothers and fathers, found that 77% of parents believed that death education in schools would not interfere with their parental responsibilities. In a study by Herrán et al. (Citation2000), 93% of 87 parents of schoolchildren aged 3–6years thought that the school should be prepared with some sort of educational response to cases where children were affected by the death of a loved one. In McGovern and Barry (Citation2000) study, 72% of 119 parents of primary-school pupils stated that death should be included in teaching.

Teacher’s attitudes toward and training in death education

Studies have enquired into teachers’ attitudes toward and training in death education. In two studies cited above on perceptions among families, teachers’ opinions were also investigated. In Herrán et al. (Citation2000), on death education in early childhood education (ages 3–6years), surveying 123 teachers with a questionnaire with open and closed questions that aimed to discover their attitudes and their educational interventions in cases of deaths affecting their pupils. 75% had had such an experience in the previous 5 years. Almost all gave fundamental importance to communication with the families and the child, adopting an approach that avoided overprotection, and affective warmth. Only 10% had developed a pedagogical approach that they had shared with other teaching staff, stating that they had “grown personally and advanced professionally” and that they “had changed.” In McGovern and Barry (Citation2000), a study of death education in primary education, 142 teachers were surveyed. The authors found that 83% had had to deal with a death affecting their students in the previous 5 years and 70% stated that death should be included in the primary school curriculum. Variables such as gender and having recently suffered the loss of a loved one affected the results: namely, more female teachers than male stated that they felt comfortable when broaching the subject of death with their pupils, and teachers who had suffered a recent loss were more favorable toward death education. Besides, 90% of the sample in this study agreed on the need for teachers to receive more training in death education.

Dyregrov et al. (Citation2013) used mixed methods to investigate teachers’ perceptions of interventions in situations of bereavement. Specifically, 138 early childhood and primary school teachers were surveyed and 22 participated in focus groups. 90% recognized that the tutor held an essential role in educational counseling for bereaved pupils. The same percentage, however, did not feel trained to take on such situations. Some sociodemographic variables affected the results: for example, teachers who had experienced the loss of a loved one felt more prepared to support their students in similar situations, and gender was also an influential factor, since more male teachers than female believed that bereaved pupils did not require support from the school.

A study by Engarhos et al. (Citation2013) introduced the variable of students’ ages. In a questionnaire answered by 59 teachers, all respondents thought that the topic of death should be dealt with in schools regardless of students’ ages. Most (71%) stated that they had discussed the topic with a pupil who requested it, while 37% had talked about it in groups. The majority thought that teaching about death could be encompassed in various parts of the curriculum such as those related to health or the sciences. Some analysts have adopted research techniques and models other than opinion surveys, interviews, and discussion groups probing in-school experiences. Potts (Citation2013), based on the explanation of a simulated case of bereavement in a 6-year-old pupil, found that the 22 primary school teachers taking part had no training for dealing with this type of situation. Also, Hinton and Kirk (Citation2015) conducted a meta-analysis which revealed teachers’ lack of training for addressing the topic of death in schools, in addition to insufficient school-family coordination when students lost a loved one. The lack of teacher training in death education is found to be a constant in studies conducted to date.

Finally, we observe from the existing literature that studies on attitudes toward, perceptions of, and training in death education among teachers share two common features: small samples and an absence of research with instruments validated by relevant psychometric tests. These characteristics hinder generalization and transference. Furthermore, research has mainly centered on approaches to bereavement in schools and, to a lesser extent, on a normalizing approach to death education through the curriculum. Our study had the following objectives: (1) to ascertain attitudes toward death education among teachers at all levels of schooling: early childhood (ages 0–6years), primary (6–12years), compulsory secondary (12–16years), sixth form (16–18years), other secondary education institutions (vocational training, adult education), and special needs education, using a valid and reliable scale; (2) to identify the influence on these attitudes of the variables of gender, age, type of teacher, teaching experience, religious beliefs, having experienced loss of loved ones, type of school, school setting, and religion; (3) to ascertain teachers’ opinions on how the topic of death is treated in schools and society.

Method

The study had a cross-sectional design in which participants’ data was collected within the same time period but in varied contexts and locations; thus, it was designed to enable analysis of diverse backgrounds (Summers & Abd-El-Khalick, Citation2018). Data were collected in 12 different regions of Spain (from a total of 17 regions) in schools that were both state and private, religious and non-religious, and from urban and rural settings. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the coordinating institution.

Sample

The sample was constructed by convenience. The instruments, accompanying a letter of invitation, were sent as bulk mail to schools of all educational levels in the 12 Spanish regions taking part. These were recruited through researchers’ contacts and lists of schools published. The schools wishing to take part forwarded the instruments to their teachers. The time elapsed from the massive distribution to the response from the final sample was three months. The complete research, including instrument design and data analysis, was performed over nine months. The final sample comprised 683 teachers.

Instruments

The study was performed using two self-administered digital instruments: the Death Education Attitudes Scale-Teachers (DEAS-T) and the Death Education Questionnaire-Teachers (DEQ-T). The first measures teachers’ attitudes toward death education, while the second analyses their opinions on how the topic of death is treated in schools and society. Both instruments were preceded by an informed consent form and a series of items registering participants’ sociodemographic variables.

Death Education Attitudes Scale-Teachers (DEAS-T)

An ad hoc scale was designed and validated, since in the literature none was found. In its final version the scale had 3 factors and a total of 9 items on a 5-point Likert scale (1–strongly agree; 2–agree; 3–neither agree nor disagree; 4–disagree; 5–strongly disagree). In the first validation phase, a battery of 62 items was developed based on the theoretical grounding of death education. After the contents had been validated by 13 experts and a piloted with 9 teachers, the second version was reduced to 52 items. A consistency analysis was performed on this version using a test-retest method (n = 67), with teachers responding voluntarily on two occasions with a time lapse of one week. In line with the intra-item correlation of the two tests and some participants’ perception of the excessive length of the scale, the instrument was reduced to 23 items, eliminating those that were redundant or had low consistency. This third version was administered to the final sample (n = 683) and the scale reduced to 9 items after exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses.

Death Education Questionnaire-Teachers (DEQ-T)

A battery of 22 items was developed based on the existing theory. After its validation by 13 experts and a pilot study with 9 teachers, the second version was reduced to 13 items, with different nominal response options, and the clarity of the questions was improved.

Results

Descriptive study of the DEAS-T Scale

shows the descriptive data for the scale in its final version. All scores were above 3 points, except that of item 5. The mean of the scale total was 3.90, indicated agreement. Thus, the teachers showed a moderately positive attitude toward death education.

Table 1. Descriptive data of the DEAS-T (N = 683).

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of the DEAS-T Scale

First, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed on the 23-item version of the scale, after finding suitable values for the sample through both a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test (KMO = .852) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p < .001). The component analysis yielded 3 factors of 3 items each which together explained almost 84% of variance. The reduction of the 23-item scale to the final 9-item version eliminated items with low saturation in the EFA. The first factor, titled “Training needs in death education” (items 1, 2, and 3), explained 56.06% of variance alone. The second factor, referring to the “Inclusion of death in education” (items 4, 5, and 6), explained 11.17% of variance, while the third factor, titled “Educational awareness of death” (items 7, 8, and 9), explained 16.5% of variance. The communality of the 9 items was above .75. The mean for the first factor was 4.32, the second 3.40, and the third 3.94.

The method of extraction and oblique rotation (Oblimin with Kaiser normalization) of the principal axes was used, with a positive correlation between the factors for performing the component analysis (). Between factors 1 and 2 the correlation was .52; between 1 and 3 was .51, and between 2 and 3 was .36. The rotation revealed suitable factor loadings.

Table 2. Exploratory factor analysis of the DEAS-T (N = 683).

To test the three-factor model yielded by the EFA a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed. An asymptotically distribution-free method was used because the multivariate distribution did not fit normality. The main criteria of goodness of fit were studied, considering the large size of the sample (Henson, Citation2006). All criteria showed values that were suitable in terms of those generally recommended (Hair et al., Citation2010): CMIN/DF = 2.06 (≤5.0); GFI = .97 (≥0.9); CFI = .97 (≥ 09); error RMSEA = .04 (≤.05). Thus, these values fit with the three-factor scale model yielded by the EFA. So that potential future studies may assess and possibly adjust and include the items discarded here, presents items not accepted for the final version of the scale validated with this Spanish population. The mean for the discarded items was 4.10, higher than that in the validated scale (M = 3.90), which thus supports the conclusion that teachers’ attitudes toward death education are positive.

Table 3. Items discarded by the exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses.

Scale reliability of the DEAS-T

The internal consistency of the scale was tested using Cronbach’s alpha, yielding a result of .89 for the scale total, .91 for factor 1, .88 for factor 2, and .89 for factor 3. The results obtained were therefore considered to be excellent (Taber, Citation2018).

Relationships of the sociodemographic variables with the DEAS-T scale results

The large sample (n = 683) justified the use of robust parametric tests such as Student’s t and ANOVA. To test the hypotheses in which statistically significant differences were found, the relevant analyses for calculating statistical power were performed, in all cases yielding values over .9.

Regarding gender, Levene’s test showed equality of variances for the scale total (p = .41, > .05) and factors 2 and 3 (p = .82 and p = .80, respectively). In factor 1 equality of variances was not found (p = .04), and for this reason the data belonging to this factor were used without equality of variances. Significant differences according to gender were found in the scale total (T = −3.10, p < .001) in factor 1 (“Death education training needs,” T = −2.45, p = .01), and in factor 2 (“Inclusion of death in education,” T = −3.90, p < .001). Significant differences were not found in factor 3 (“Educational awareness of death,” T = −1.09, p = .27). The differences were in favor of women, who had higher scores than men: in the scale total the values for women were M = 35.70 and for men M = 33.73. The effect size was low (d = .26), in terms of Cohen’s criteria (1988). In the factors the women also had higher scores than men.

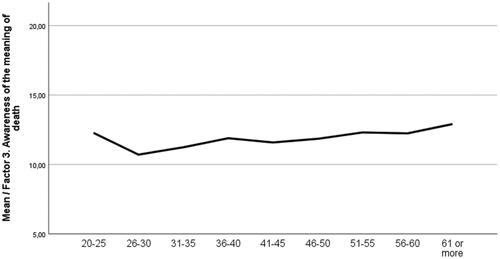

Turning to the teachers’ ages, the ANOVA test found significant differences only in factor 3, “Educational awareness of death” (F = 2.18; p = .03). Homogeneity of variances was assumed (p = .24) and Tukey’s test was applied, yielding significant differences among teachers from 26 to 30 and from 51 to 55, with higher results in the latter group. As shows, in general, scores were positively associated with participant age, except for the youngest group, which also had high scores. Logically, similar results also appeared for the variable of teachers’ years of experience, with significant differences among groups in factor 3 (F = 2.28; p =.03).

The type of teacher also influenced results significantly: specifically, in the scale total (F = 2.25; p = .048), factor 2 (F = 3.88; p < .001), and factor 3 (F = 6.54; p < .001). Both in the scale total and in these two factors homogeneity of variances was found. The Tukey test showed that in the scale total there were significant differences between early childhood education teachers (ages 0–3) and counselors (p = .04), with higher means among the counselors (M = 39.17) than the teachers (M = 34.44), and a moderate effect size (d = .57) (Cohen, Citation1988). There were also significant differences between secondary-school teachers and counselors (p = .03), also with higher means among the counselors than the teachers (M = 34.76). The effect size was also moderate (d = .55) (Cohen, Citation1988). Jointly with the counselors, the group with the highest means was that of vocational training teachers (M = 36.74).

Regarding religious beliefs—with teachers divided into “atheists,” “agnostics” and “Catholics”—significant differences were found only between groups in factor 2 (“Inclusion of death in education,” F = 4.16; p = .02, ≤ .05), with equality of variances (p = .99, > .05). The Tukey test found significant differences between Catholics and atheists (p = .02), with higher means among atheists (M = 10.16) than Catholics (M = 9.85), who were the group that was most reluctant of the three to include death in education. The effect size was small (d = .27) (Cohen, Citation1988).

Significant differences were not found in relation to the experience of loss, perhaps due to the difference in percentages between the two groups (94.1% stated that they had suffered the loss of a loved one), although means were higher among those who had suffered such a loss (M = 35.28) than those who had not (M = 33.05).

The type of school (state or private) significantly influenced the results of the scale total (T = −2.84; p < .001), factor 1 (in this case without equality of variances, T = −3.99; p < .001) and factor 2 (T = −3.19; p < .001) in all cases, with higher means in private schools. Thus, in the scale total, state schoolteachers scored M = 34.74 and those in private schools M = 36.99. The effect size was small (d = .30) (Cohen, Citation1988). The urban or rural setting of the school, however, did not affect results (in the scale total T = 1.34; p = .18).

Lastly, the religious or non-religious character of the school significantly influenced results in factors 1 (without equality of variances, T = −2.71; p = .01) and 2 (with equality of variances, T = −2.63; p = .01), with higher results among teachers in religious schools.

Results of the DEQ-T

presents the results obtained in the DEQ-T.

Table 4. Results of the DEQ-T (N = 683).

Discussion

In terms of our first research objective, this study affords a useful, validated instrument administered to a large sample to analyze teachers’ attitudes toward death education; an analysis which includes, amongst other factors, the identification of training needs. This is an innovative contribution to the field since the instruments used up to now have been opinion questionnaires with no presentation of their psychometric characteristics (Dyregrov et al., Citation2013; McGovern & Barry, Citation2000). The scale presented here can be used for populations in different countries, by adopting either the items validated for the Spanish population or other items discarded in the validation process (). The results of the EFA and CFA reflect suitable values and excellent reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .89.

The DEAS-T is presented as a three-factor scale with a total of 9 items. The first factor is titled “Death education training needs,” the second “Inclusion of death in education” and the third “Educational awareness of death.” The whole scale appropriately reflects, on a theoretical level, the construct of attitudes toward death education, taking into account the main dimensions studied. One of these, linked to the first factor, is teachers’ training in death education, investigated in studies such as those by Dyregrov et al. (Citation2013), Herrán and Cortina (Citation2006), Herrán et al. (Citation2000), Hinton and Kirk (Citation2015) and Potts (Citation2013). The second factor, related to the inclusion of death education in the curriculum, also corresponds to a topic researched in recent years in countries such as Spain (Herrán et al., Citation2000, Citation2019; Herrán & Cortina, Citation2006; Rodríguez et al., Citation2020), Great Britain (James, Citation2015) and Cyprus (Stylianou & Zembylas, Citation2018). The third factor, related to the first two, corresponds to a fundamental topic in death education: the concept that teachers themselves have of the educational awareness of death and its meaning for life. In other words, the personal growth of the teacher as a core aspect of her/his attitudes toward death education. Thus, the structure of the scale, reflecting the different dimensions of death education, is fitted to the existing theory and literature.

Our findings reveal a moderately positive attitude toward death education among teachers, with values above 3 points in all cases, except item 5, and a scale mean of 3.90 out of 5. These results coincide with previous studies, which also found that teachers were favorable toward death being included in education (Dyregrov et al., Citation2013; Engarhos et al., Citation2013; Herrán et al., Citation2000; McGovern & Barry, Citation2000). Analyzing the results by factors, those for the first factor (“Death education training needs”) are the most notable. Participants were very much in favor of death education training for teachers, with a mean of 4.35. Nevertheless, as can be observed in the results of the complementary opinion questionnaire (DEQ-T, item 10), the overwhelming majority had not received any type of training in the area of death education (item 10), despite the obvious fact that death continually affects schools and their students (item 1). These findings, as a whole, firmly support the clear need for the implementation of programs for both pre- and in-service teacher training in death education. Moreover, there is a noteworthy discrepancy between these favorable attitudes toward death education among teachers and the lack of planning in educational systems and schools with regard to the inclusion of death in education, manifest both in other studies (Herrán et al., Citation2019; Rodríguez et al., Citation2020) and in the DEQ-T outcomes.

Turning to the influence of the sociodemographic variables on the results (objective 2), first, we will review those studied in the previous research. In terms of gender, our results tally with the existing studies (Dyregrov et al., Citation2013; McGovern & Barry, Citation2000), which found that women teachers had more open and favorable attitudes toward death education than their male colleagues. Another variable included in prior studies is the influence on attitudes of having experienced the loss of a loved one. In our study, while we did not find significant differences between those who had suffered such a loss and those who had not, possibly due to the difference in size between the two groups, an analysis of the means indicates that those had suffered loss had higher scores in the scale. This tendency concurs with the findings of the studies by Dyregrov et al. (Citation2013), and McGovern and Barry (Citation2000).

Other variables, not previously studied, were included here. One of these was the age of the teacher. The results showed that age affected outcomes in factor 3, “Educational awareness of death.” In general, older teachers had more positive attitudes toward the educational potential of death and its importance for life. This personal facet of their attitudes is essential for the development of an education that takes death into account, since teachers’ practice will be conditioned, to a great extent, by their concept of death (Herrán & Cortina, Citation2006). A concept of death associated, as in this case, with enhanced understanding, enabling us to live our lives with greater awareness, helps us to view our deaths without focusing on anxiety or fear. This capacity also seems to be linked to age. Thus various studies (i.e., Chopik, Citation2017; Russac et al., Citation2007) have found that the older the teacher, the lower the level of anxiety around death, results which agree with those in factor 3 of our scale. Another variable included in this study was the influence of the type of teacher. The results show that counselors are those who had the most favorable attitudes toward death education. Perhaps these findings are related to the fact that cases in which guidance is needed in situations of bereavement in schools are usually passed to the educational counselors, and not to the tutors—although the latter represent the basic figures for guidance and the link between the school and the family—and that therefore the former are more familiar with educational situations having to do with death.

This study also analyzed the influence of religious beliefs and the religious orientation of the school our participants were teaching in. With regard to the first, we found that teachers seeing themselves as atheists had the most positive attitudes toward the inclusion of death in education (factor 2), with statistically significant differences compared to those seeing themselves as Catholics. Also, those who stated that they were agnostics had higher scores than the Catholics, while there were no significant differences. At the same time, teachers working in religious schools had more favorable attitudes in factors 1 and 2 than those from non-religious schools (these results are coherent with the fact that teachers working in private schools had higher scores than those in state schools, which are all non-religious). It should be noted that Spanish religious schools do not require their teachers to share their faith. In fact, the results of the DEQ-T (item 3) showed that only 2.8% of the sample thought that they should educate children in accordance with the religious beliefs of the school, while the majority thought that they should adopt a lay, pedagogical approach, thus reinforcing some science-based models of death education oriented toward pluralism and inclusiveness (Corr et al., Citation2019, Herrán & Cortina, Citation2006). In the area of the teachers’ own religious beliefs, significant differences between atheists and Catholics were found for factor 2, “Inclusion of death in education.” The former had more favorable attitudes than the Catholics toward including death in children’s education. The agnostics also had higher scores than the Catholics, while there was no significant difference. One reason for this (although it is not investigated in this study and would prove fruitful as a future line of research) may be the assumption that Catholic teachers see death as a topic exclusively related to religion or family moral upbringing.

Other results from the DEQ-T, enquiring into teachers’ opinions on how death is treated in our schools and society (objective 3), are of interest for this discussion. The majority saw death as a taboo topic in our society (item 13), a taboo which is then transferred to schools, where the topic is not normally included in the educational project (item 11), and where there are normally no procedures in place for action in cases of deaths affecting students (item 12). The exclusion of the topic of death from national and regional curricula (Herrán et al., Citation2019; Rodríguez et al., Citation2020) is consistent with this result, indicating that death is not present in school education projects in general (Herrán et al., Citation2000).

Furthermore, the lack of any type of planning of school organization or coordination among educational actors in situations of bereavement was very clearly revealed, a situation reflected in other studies (Hinton & Kirk, Citation2015) that has been addressed by systematic proposals for change (Cortina & Herrán, Citation2011). In fact, only 3.1% of the sample stated that, in the case of a loss affecting the school, they had recourse to a previously planned procedure. This figure contrasts with the situation in other countries, such as Denmark, the other Scandinavian countries, and Australia, where all schools have detailed procedures for supporting bereaved students (Lytje, Citation2018).

It was striking that in general the teachers felt equipped to deal with educational situations around death (items 4, 6, and 7, but not 5, where results were more balanced), while on the other hand the majority also stated that they had not received any type of training in death education. We do not know, therefore, if this assumption of competence coincides with their real competencies when they actually have to educate students on the topic, or whether they simply assumed that they did not need specific teaching competencies for this purpose. The results from item 5, which asked teachers a specific question on counseling in situations of bereavement, indicated that this hypothesis may be plausible and that while, as Potts (Citation2013) argues, teachers may not be equipped to deal with the topic of death educationally with their students, the educators themselves saw their experience and emotional confidence as sufficient for counseling and guidance.

This study entails a series of limitations that at the same time represent further challenges and future lines of research. First, our findings stem from the Spanish context. They may be generalizable to closely related societies and cultures, but results will probably also differ in other countries and contexts. Moreover, although the total sample was large, we were not able to take minority groups (below 1.5% of the total sample) from some sociodemographic variables into account in our analysis. We are referring, for example, among teacher types, to teachers in special needs education, and among religious beliefs, to those with different faiths from those analyzed. Further studies may be able to investigate these groups in more depth. It is important that further studies should be conducted to analyze the relevance of cultural and/or religious diversity in planning and implementing death education, and to examine the implications of specific contexts in which death may have a stronger presence, such as special education centers. It will also be necessary, in a society and an education aiming for inclusiveness, to generate and research didactic methods that are inclusive of death for teaching students who are vulnerable or require priority attention. Another limitation was that, due to the quest for suitable psychometric values for the DEAS-T, some items that may be important on a theoretical level were omitted. However, these items have been included in the present paper so that they may be incorporated in the scale if necessary in future studies of other contexts.

The research presented here, despite the limitations mentioned above, represents a considerable advance in the field of teaching and teacher training in the radical educational topic of death, which is transcultural, transnational and of interest for education at all historical times. Our findings show that, although it is a topic that is almost totally absent from their training, educators have a positive attitude toward its inclusion in education, both in the curriculum and preparation for bereavement and also in situations requiring educational guidance in cases of loss. Death education responds to a twofold objective reality: (1) the awareness of death and finiteness is a privileged educational field, and (2) death affects schools and therefore demands a response through tutorial action, with the necessary backup from counseling departments. It addresses, therefore, a relatively normal and current need in schools, although this is not sufficiently reflected in curricula. But it also is relevant to an essential challenge, that of an education which truly prepares students for life. We cannot educate for life if we do not take death into account. Thus, we need both pre- and in-service teacher training programs (embracing school heads, counselors, tutors, and all other teaching staff) in death education. In light of this study’s findings, such training would be welcome among teachers at all levels. Moreover, it is essential for teachers and educational counselors trained in death education to work together to design teaching strategies to address death or jointly plan the bereavement support program. Our findings also suggest that education authorities should design curricula that do not only take education for life into account, but also death. First, an education that omits the awareness of death is not complete. Second, death inevitably touches schools themselves. Hence, it makes complete pedagogical sense to include the awareness of death in curricula and teacher training programs that aspire toward a more complex and conscious education for human beings of all nations and cultures.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aspinall, S. Y. (1996). Educating children to cope with death: A preventive model. Psychology in the Schools, 33(4), 341–349. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6807(199610)33:4%3C341::AID-PITS9%3E3.0.CO;2-P

- Berg, C. D. (1978). Helping children accept death and dying through group counseling. The Personnel and Guidance Journal, 57(3), 169–172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2164-4918.1978.tb05135.x

- Birkholz, G., Clements, P., Cox, R., & Gaume, A. (2004). Students’ self-identified learning needs: A case study of baccalaureate students designing their own death and dying course curriculum. The Journal of Nursing Education, 43(1), 36–39. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20040101-01

- Bos, P. R. (2014). Empathy, sympathy, simulation? Resisting a Holocaust pedagogy of identification. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 36(5), 403–421. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2014.958380

- Burtonwood, N. (2002). Holocaust Memorial Day in schools – Context, process and content: A review of research into Holocaust education. Educational Research, 44(1), 69–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00131880110107360

- Chopik, W. J. (2017). Death across the lifespan: Age differences in death-related thoughts and anxiety. Death Studies, 41(2), 69–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2016.1206997

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Academic Press.

- Colomo, E. (2016). Pedagogía de la muerte y proceso de duelo. Cuentos como recurso Didáctico. Revista Iberoamericana Sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 14(2), 63–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15366/reice2016.14.2.004

- Corr, C., Corr, D., & Doka, K. (2019). Death and dying, life and living. Brooks/Cole Publishing Company.

- Cortina, M., & Herrán, A. d l. (2011). Pedagogía de la muerte a través del cine. Humanitas.

- Dennis, D. (2009). Living, dying, grieving. Jones and Barlett Publishers.

- Dyregrov, A., Dyregrov, K., & Idsoe, T. (2013). Teachers´ perceptions of their role facing children in grief. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 18(2), 125–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2012.754165

- Engarhos, P., Talwar, V., Scheifer, M., & Renaud, S. (2013). Teachers´ attitudes and experiences regarding death education in the classroom. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 59(1), 126–128.

- Galende, N. (2015). Death and its didactics in pre-school and primary school. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 185(13), 91–97. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.03.403

- Hair, J., Black, C., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Harrawood, L., Doughty, E., & Wilde, B. (2011). Death education and attitudes of counselors-in-training toward death: An exploratory study. Counseling and Values, 56(1-2), 83–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-007X.2011.tb01033.x

- Henson, R. K. (2006). Effect-size measures and meta-analytic thinking in counseling psychology research. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(5), 601–629. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000005283558

- Herrán, A. d l., & Cortina, M. (2006). La muerte y su didáctica. Humanitas.

- Herrán, A. d l., Rodríguez, P., & Miguel, V. d. (2019). Is death in the Spanish curriculum? Revista de Educación, 385, 201–226. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2019-385-422

- Herrán, A. d l., González, I., Navarro, M. J., Bravo, S., & Freire, M. V. (2000). ¿Todos los caracoles se mueren siempre? Cómo tratar la muerte en educación infantil. Ediciones de la Torre.

- Hinton, D., & Kirk, S. (2015). Teachers´ perspectives of supporting pupils with long-term health conditions in mainstream schools: A narrative review of the literature. Health & Social Care in the Community, 23 (2), 107–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12104

- Holland, J. (2008). How schools can support children who experience loss and death. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 36(4), 411–424. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880802364569

- James, S. (2015). The nature of informed bereavement support and death education in selected English primary schools [PhD dissertation]. University of Hull.

- Jones, C., Hodges, M., & Slate, J. (1995). Parental support for death education programs in the schools. School Counselor, 42, 370–376.

- Lindquist, D. H. (2007). Avoiding inappropriate pedagogy in middle school teaching of the Holocaust. Middle School Journal, 39(1), 24–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00940771.2007.11461610

- Lytje, M. (2018). The Danish bereavement response in 2015—Historic development and evaluation of success. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 62(1), 140–149. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2016.1212258

- Mantegazza, R. (2004). Pedagogia della morte. Città Aperta.

- McGovern, M., & Barry, B. (2000). Death education: Knowledge, attitudes, and perspectives of Irish parents and teachers. Death Studies, 24(4), 325–333. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/074811800200487

- Mèlich, J. C. (1989). Situaciones-límite y educación. Estudio sobre el problema de las finalidades educativas. PPU.

- Petitfils, B. (2016). Encountering mortality: A decade later, the pedagogical necessity of Six Feet Unter. Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy, 13(3), 249–260. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15505170.2016.1220876

- Potts, S. (2013). Least said, soonest mended? Responses of primary school teachers to the perceived support needs of bereaved children. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 11(2), 95–107. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X12466201

- Rodríguez, P., Herrán, A. d l., & Cortina, M. (2015). Pedagogía de la muerte mediante aprendizaje servicio. Educación XX1, 18(1), 189–212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5944/educxx1.18.1.12317

- Rodríguez, P., Herrán, A. d l., & Cortina, M. (2019). Antecedentes internacionales de la pedagogía de la muerte. Foro de Educación, 17(26), 259–276. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14516/fde.628

- Rodríguez, P., Herrán, A. d l., & Miguel, V. d. (2020). The inclusion of death in the curriculum of the Spanish Regions. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2020.1732192

- Russac, R. J., Gatliff, C., Reece, M., & Spottswood, D. (2007). Death anxiety across the adult years: An examination of age and gender effects. Death Studies, 31(6), 549–561. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180701356936

- Schoen, A., Burgoyne, M., & Schoen, S. (2004). Are the developmental needs of children in America adequately addressed in the grieving process? Journal of Instructional Psychology, 31(2), 143–150.

- Stough, L. M., Kang, D., & Lee, S. (2018). Seven school-related disasters: Lessons for policymakers and school personnel. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 26, 100. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.26.3698

- Stylianou, P., & Zembylas, M. (2018). Dealing with the concepts of “grief” and “grieving” in the classroom: Children's perceptions, emotions, and behavior. Omega, 77(3), 240–266. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222815626717

- Summers, R., & Abd-El-Khalick, F. (2018). Development and validation of an instrument to assess student attitudes toward science across grades 5 through 10. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 55(2), 172–205. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21416

- Taber, K. (2018). The use of Cronbach´s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education, 48(6), 1273–1296. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. (2014). UNESCO education strategy 2014–2021. UNESCO.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. (2015). Incheon Declaration: Education 2030: Towards inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning for all. UNESCO.

- Vlok, M., & de Witt, M. W. (2012). Naive theory of biology: The pre-school child´s explanation of death. Early Child Development and Care, 182(12), 1645–1659. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2011.636811

- Willis, C. (2002). The grieving process in children: Strategies for understanding, educating, and reconciling children’s perceptions of death. Early Childhood Education Journal, 29(4), 221–226. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015125422643

- Yang, S., & Chen, S. (2006). Content analysis of free-response narratives to personal meanings of death among Chinese children and adolescents. Death Studies, 30(3), 217–241. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180500493385

- Zembylas, M. (2011). Personal narratives of loss and the exhumation of missing persons in the aftermath of war: In Search of public and school pedagogies of mourning. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 24(7), 767–784. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2010.529839