Abstract

A death certificate is an important public health surveillance tool that affects the quality of morbidity and mortality statistics. This systematic review examines death certification in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, uncovers the methodological qualities of published studies, the common errors committed by certifiers, and physicians’ knowledge in filling out death certificates. We searched three databases, finding 19 studies, the majority of which reported errors in the underlying cause of death. Fewer than 25% of physicians reported training on filling out death certificates. Complexity of the cases and lack of training were reported as common difficulties facing physicians leading to errors.

A death certificate (DC) is an official permanent legal record of the fact of death that provides essential personal information about the deceased person, information about the medical cause, and location and time of death (Sondik et al., Citation2003). Correct determination and registration of mortality data are important for tracking disease trends and the health of a population, developing public health programs, and allocating health care resources locally and internationally. Death certification is an important public health surveillance tool.

Physicians’ primary responsibility in death registration is to complete the medical part of the DC (Sondik et al., Citation2003). In so doing, they perform the final act of care to the deceased person by providing a closure with a well written, accurate, and complete DC that will allow the family to settle the person’s affairs (Sondik et al., Citation2003). Depending on the country of death, DC may be needed to get a burial permit (Sondik et al., Citation2003).

For the purpose of standardization among all nations, the World Health Organization (WHO) has developed standards for the collection and classification of mortality data so that people can make international comparisons. The cause of death section of WHO’s DC form consists of two parts (Kotabagi et al., Citation2004). Part I is for reporting the sequence of events leading directly to death, proceeding backwards from the final disease or condition resulting in death, with one condition per line. It consists of three subparts: lines a, b and c, some newer versions of the DC formats contain an additional line d; however, countries may continue to use certificates with only three lines (World Health Organization, Citation2004). Subpart a is the immediate cause of death (ICOD) (i.e. the final disease, injury, or complication directly causing death). Subparts b, c and d (in the newer versions of DCs) are the antecedent causes of death (i.e. the morbid conditions giving rise to the immediate cause of death) listed sequentially with the underlying cause of death (UCOD) (i.e. the disease or injury that initiated the chain of events that led directly and inevitably to death), which is a subtype of antecedent causes written on the lowest used line (c or d). In this review we referred to the antecedent causes of death other than the UCOD as ACOD.

The mechanism of death (for example, cardiac or respiratory arrest) should not be reported as the ICOD as it is a statement not specifically related to the disease process, and it merely attests to the fact of death (Sondik et al., Citation2003). For example, a man with a known history of asthma and protein c deficiency is admitted to hospital with shortness of breath. He is diagnosed with deep vein thrombosis (DVT) a few days prior to admission. He developed respiratory arrest few hours after admission and died. The ICOD in this case is pulmonary embolism, the ACOD is DVT, the UCOD is protein c deficiency, and the respiratory arrest is the mechanism of death and should not be considered as the ICOD. Part II of DC is for reporting all other significant diseases, conditions, or injuries that contributed to the death but which did not result in the UCOD (Sondik et al., Citation2003). Generally, cause of death statistics depends on the reported UCOD.

Although accurate cause of death reporting is critical to obtain good quality mortality statistics (Mathers et al., Citation2005), most physicians do not receive training in completing death certification forms. Lack of training consequently leads to inaccuracies in the information entered and affects the quality and value of derived mortality statistics. Errors could occur at various stages of the cause of death reporting process such as incomplete certification, inaccurate determination of cause of death, unexplained abbreviations, or illegible handwriting (Pritt et al., Citation2005). Errors in DC documentation are common and are reported from different countries globally (Katsakiori et al., Citation2007; Maharjan et al., Citation2015; Pritt et al., Citation2005). Errors could be attributed to staff inexperience, lack of training, fatigue, time constraints, unfamiliarity with the deceased person and perceived lack of importance of the DC (Izegbu & Onabanjo, Citation2006; Lakkireddy et al., Citation2004; Pritt et al., Citation2005).

Civil registration systems have the potential to serve as the main source of national vital statistics. Assessment of these systems in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean region (EMR) showed that only 19% of deaths are medically certified, and the quality of cause of death data along with training of coders were the main concerns affecting the functionality of such systems in this region (World Health Organization (WHO), Citationn.d.). We restricted our review to WHO EMR, which includes 21 member states and Palestine (WHO | Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, Citationn.d.)

To the best of our knowledge, no systematic reviews assessing the quality of death certification in the WHO EMR have been conducted except for one limited systematic review in Saudi Arabia that assessed common errors in completing the cause of death in DCs in the Middle East. That review included only five studies from four countries, and excluded studies assessing the knowledge and practice of medical practitioners on death certification (Madadin et al., Citation2019). In this present systematic review, we addressed these limitations. Our objectives were to review the quality of death certification in WHO EMR by uncovering the methodological qualities of published studies in this region, identifying common errors committed by certifiers, and physician’s knowledge of coding rules and filling out DCs.

Method

We systematically reviewed research on death certifications in the WHO EMR. The inclusion criteria were cross-sectional studies assessing death certification with no language restrictions or time frame. We conducted the search from 1 October 2019 to 30 October 2020.

We searched for: population that includes DCs and physicians; outcomes including accuracy, errors, and completion of DC, and physician’s knowledge of and practice in death certification; and, settings that include countries in the WHO EMR. We searched three electronic databases: PubMed, Science Direct and Google Scholar, using both MeSH terms and key words (for the exact search strategy see supplemental material). We then reviewed the full text of these 19 articles. During the process of data screening, we resolved discrepancies by consensus. These 19 articles are marked by an asterisk in the reference list.

We assessed the quality of the included studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist for studies reporting prevalence data (Munn et al., Citation2015), similar to Yasin et al. (Citation2020). Answers to this nine items appraisal checklist are categorized into “yes,” “no,” “unclear,” and “not applicable N/A” The total score for each article was obtained by giving one point for yes, zero point for no or unclear, and then dividing it by the maximum possible score the article in question can get after subtracting “not applicable points.” Then, we multiplied the resulting proportion by 10 to get a standardized score out of 10. Finally, we assigned the studies to one of three methodological quality categories depending on the final score as follows: weak (≤5.9), moderate (6–7.9), and strong (≥8) (Yasin et al., Citation2020) ().

Table 1. Quality assessment results using elements of Johnna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist for studies.

Results

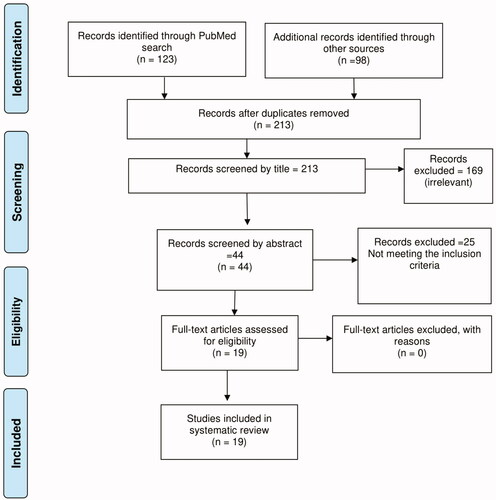

We initially retrieved 221 studies. After removing eight duplicates, 213 articles remained. Screening their titles, we further eliminated 169 articles that were not relevant, leaving 44 articles. Next, four independent reviewers screened the abstracts of these 44 articles using the Rayyan QCRI® website (http://rayyan.qcri.org). We further excluded 25 articles that did not meet inclusion criteria, leaving 19 articles for the purpose of this systematic review. is a flow diagram showing the search outcomes.

Figure 1. Flow chart showing screening of publications for inclusion in the systematic review using the PRISMA flow diagram.

On the JBI tool, 10 studies demonstrated a strong quality with a score of ≥8 and the highest score being 8.9 for studies in Iran (Mahdavi et al., Citation2015), Qatar (Al-Kubaisi et al., Citation2013), and Palestine (Qaddumi et al., Citation2018), seven studies demonstrated moderate quality with scores between 6 and 7.9 (), and two studies demonstrated weak quality with scores of ≤5.9 and the lowest score being 3.8 for an older study in Kuwait (Moussa et al., Citation1990).

We grouped errors reported in DCs into two broad categories: reporting the causes of death, and editing. summarizes errors reported by individual studies.

TABLE 2. Common errors in death certificates.

Errors in reporting the causes of death

Errors in reporting the causes of death may include: incorrect reporting (incorrect cause, missing cause, or mismatch between DCs and medical file) of the immediate, antecedent, or underlying cause of death, incorrect sequencing of the chain of events leading to death, reporting the mechanism of death as a cause of death, reporting competing causes of death that occur when physicians list two or more causally unrelated diseases in Part 1 of the DC, or errors in the translation of the cause of death from the medical file of the deceased person to the DC or between different versions of DCs.

Of the 19, nine studies reported errors in ICOD. Two studies in Sudan (El-Nour et al., Citation2007; Kheir et al., Citation2016) reported incorrect ICOD in about 40% of examined DCs and missing ICOD in about 13–15% of them. Two studies in Pakistan reported incorrect ICOD in 62 and 84% of examined DCs (Arif et al., Citation2014; Haque et al., Citation2013). One study in Palestine reported incorrect ICOD in 94.1% of DCs (Qaddumi et al., Citation2017). One study in Libya and one in Saudi Arabia, respectively, reported that the ICOD did not match the one inferred from the medical file in 30.3 and 52.8% of the cases (Abdulmalek, Citation2013; Binsaeed et al., Citation2008). Hypothetical scenarios in Palestine and Qatar, respectively, reported that 51.3 and 29.3% of physicians incorrectly reported ICOD when asked to fill a DC form for a case scenario (Al-Kubaisi et al., Citation2013; Qaddumi et al., Citation2018). About half of the studies had information about ICOD, which was frequently wrong, and sometimes missing.

Of the 19, only two studies, both in Sudan, reported errors in ACOD in 21.5 and 33% of the examined DCs. ACOD was missing in 59% and 54% of DCs (El-Nour et al., Citation2007; Kheir et al., Citation2016). Data on ACOD is skimpy, but indicates that ACOD was sometimes wrong and frequently missing, although this information is only reported in two studies in one country.

Of the 19, 12 studies reported errors in UCOD. Two in Sudan (El-Nour et al., Citation2007; Kheir et al., Citation2016) reported incorrect UCOD in 12% of examined DCs, and UCOD missing in more than 75% of examined DCs. Two in Pakistan reported incorrect UCOD in 87% of examined DCs (Arif et al., Citation2014; Haque et al., Citation2013). One in Lebanon reported missing UCOD in 58.5% of examined DCs (Sibai et al., Citation2002). One in Palestine reported incorrect UCOD in 44.6% of examined DCs (Qaddumi et al., Citation2017). In Kuwait, a study (Moussa et al., Citation1990) showed poor agreement between medical files of deceased person and DCs. In Libya (Abdulmalek, Citation2013) and Saudi Arabia (Binsaeed et al., Citation2008), such disagreements in the UCOD between the medical files of the deceased person and DCs ranged from 28% to around 80%, respectively. In Iran, the UCOD was incorrect or did not match those in clinical records in 37.6% of examined DCs (Alipour et al., Citation2020). In the same hypothetical scenarios in Palestine and Qatar, respectively, 28.7 and 42% of physicians reported incorrect UCOD (Al-Kubaisi et al., Citation2013; Qaddumi et al., Citation2018). Across multiple studies in multiple countries, the UCOD was incorrect, missing or mismatched the one written in the medical file of the deceased person.

Sequence errors occur when there is incorrect sequencing of the chain of events leading to death. Of the 19, seven studies reported incorrect sequence error. Two studies in Iran and one in Tunisia, reported sequence errors in more than 30% of the examined DCs (Alipour et al., Citation2020; Ben Khelil et al., Citation2017; Haghighi et al., Citation2014). Two studies in Pakistan reported sequence error in 87% and 58% of examined DCs (Arif et al., Citation2014; Haque et al., Citation2013). In Palestine, incorrect sequence error was the second most common major error reported in the examined certificates detected in 41.3% of DCs (Qaddumi et al., Citation2017). In the hypothetical scenario study that reported on sequence error, 14.6% of physicians committed a sequence error (Qaddumi et al., Citation2018). Only about a third of studies reported on sequence errors, and they varied a good deal.

Of the 19, 14 studies reported the error of listing the mechanism of death as a cause. The percentage of the examined DCs with this error ranged from as low as 20% in one study in Tunisia (Ben Khelil et al., Citation2017) to around 70% in Saudi Arabia where cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA) was listed as a cause in the majority of DCs in three studies (Aljerian, Citation2019; Ansary et al., Citation2012; Binsaeed et al., Citation2008). In Bahrain, a study that examined DCs with ill-defined causes of death (coded according to ICD-10 as R0-R99) showed that most of the UCOD in the certificates were recorded as “brought dead” and “cardiopulmonary failure” (Abulfatih & Hamadeh, Citation2010). In Kuwait and Pakistan, three studies reported this error in over 60% of examined DCs (Arif et al., Citation2014; Haque et al., Citation2013; Moussa et al., Citation1990). In Palestine, and Sudan (El-Nour et al., Citation2007; Qaddumi et al., Citation2017), another two studies reported this error in over 40% of DCs. In Iran, two studies reported this error in 28 and 48% of DCs (Alipour et al., Citation2020; Haghighi et al., Citation2014). In the hypothetical case scenario studies in Palestine and Qatar respectively, 17.3 and 80% of physicians committed this error (Al-Kubaisi et al., Citation2013; Qaddumi et al., Citation2018). Almost three quarters of studies reported the error of listing the mechanism of death as a cause.

Of the 19, seven studies from four countries listed the reporting of competing causes of death as an error. Most (6) of them reported this error in fewer than 15% of the examined certificates (Ben Khelil et al., Citation2017; El-Nour et al., Citation2007; Haghighi et al., Citation2014; Kheir et al., Citation2016; Qaddumi et al., Citation2017, Citation2018). One study in Iran, reported this error in 27.4% of DCs (Alipour et al., Citation2020). Competing causes of death was an error that occurred less often than other errors.

Of the 19, only three studies addressed errors in the translation of the cause of death between English and Arabic. In Saudi Arabia, one study assessed the translation of the UCOD and the ICOD between the English and Arabic versions of DCs. The translation was incorrect in 54.8% for ICOD and in 35.7% of the cases for UCOD (Binsaeed et al., Citation2008). In Sudan and Libya, two studies reported this error in 9.4 and 1% of the cases, respectively (Abdulmalek, Citation2013; Kheir et al., Citation2016). Research rarely examined translation problems, and the ones that did were quite varied in what they found.

Editing errors

Editing errors include use of unexplained abbreviations (without mentioning what the abbreviation stands for), illegible handwriting and missing information such as absence of time interval for each diagnosis, absence of certifier signature, or physician title. Of the 19, five studies reported the use of unexplained abbreviations. In Tunisia, Palestine and Iran, respectively, studies reported this error in about 63, 39, and 31% of examined DCs (Alipour et al., Citation2020; Ben Khelil et al., Citation2017; Qaddumi et al., Citation2017). In Palestine and Qatar, respectively (Al-Kubaisi et al., Citation2013; Qaddumi et al., Citation2018), 84.7 and 28.4% of the physicians used abbreviations when they were asked to fill a DC for a case scenario. Studies showed that the use of unexplained abbreviations was observed in more than 25% of the examined DCs.

Of the 19, seven studies from five countries reported the use of illegible handwriting. In Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, and Palestine, three studies reported this error in fewer than 11% of examined DCs (Aljerian, Citation2019; Ben Khelil et al., Citation2017; Qaddumi et al., Citation2017). In Iran, two studies reported this error in 2.5 and 40.3% of DCs (Alipour et al., Citation2020; Haghighi et al., Citation2014). In the hypothetical scenarios studies in Palestine and Qatar, respectively, 6.7 and 53.6% of physicians used illegible handwriting (Al-Kubaisi et al., Citation2013; Qaddumi et al., Citation2018). Less than half of studies reported this error, and the rate of this error quite varied across studies even within the same country.

Of the 19, 10 studies reported missing information. Four studies reported absence of time interval for each diagnosis. In Tunisia, Palestine and Iran, three studies reported no time interval in more than 90% of examined certificates (Alipour et al., Citation2020; Ben Khelil et al., Citation2017; Qaddumi et al., Citation2017). In Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Sudan and Tunisia, respectively, four studies reported lack of certifier signature in 51, 42, 18, and 0.9% of DCs (Ben Khelil et al., Citation2017; Binsaeed et al., Citation2008; El-Nour et al., Citation2007; Sibai et al., Citation2002). Two studies reported lack of physician title. In Libya (Abdulmalek, Citation2013), 75% of examined DCs lacked physician title, while in Tunisia 42.8% of DCs did (Ben Khelil et al., Citation2017). In Sudan, almost all DCs (99.1%) contained some missing information (Kheir et al., Citation2016). In the hypothetical scenario study in Palestine, 38% of physicians committed this error (Qaddumi et al., Citation2018). More than half of studies reported some missing information.

Awareness of coding rules and filling out death certificates

Of the 19, three studies reported the awareness of coding rules and filling out DCs. In Iran (Mahdavi et al., Citation2015), one study that tested the awareness of the research participants (who were involved in issuing DCs) through a questionnaire, reported that the average awareness about all coding rules was low. In Bahrain, 72% of physicians were unaware of the guidelines of DC completion and 97% did not know the coding system used for coding the causes of death (Ali & Hamadeh, Citation2013). In Qatar, 35% of physicians reported their unawareness of completing DCs forms (Al-Kubaisi et al., Citation2013). The awareness of coding rules and filling out DCs is generally low.

Of the 19, five studies addressed the training of physicians on issuing of DCs and common difficulties they faced when completing DC forms. In the five studies the training rate did not exceed 25% as reported by physicians. The most common difficulties reported were lack of training, complexity of the cases and lack of understanding of the terms used in the form (Ali & Hamadeh, Citation2013; Al-Kubaisi et al., Citation2013; Arif et al., Citation2014; Mahdavi et al., Citation2015; Qaddumi et al., Citation2018). Only one study reported problems in DC design and lack of time as difficulties (Qaddumi et al., Citation2018). Only few studies reported on common difficulties facing physicians in filling out DCs with lack of training being the most common.

Discussion

Mortality is a vital statistic used to assess the health status of a country. Therefore, the accuracy and completeness of DCs are vital to the overall mortality statistics. More than half of these EMR studies demonstrated strong methodological quality. The lowest score, for one study in Kuwait (Moussa et al., Citation1990) as compared to more recent studies, might reflect that our understanding of research, and ability to analyze data have evolved since 1990.

The most common of the errors were in reporting the UCOD, similar to a study in Nepal (Maharjan et al., Citation2015). Two studies from Sudan reported incorrect UCOD in about 12% of examined DCs (El-Nour et al., Citation2007; Kheir et al., Citation2016), similar to the result of a study in Vermont, USA, that examined DCs from the Vermont Electronic Death Registration System (EDRS) and found that about 18% of them included wrong UCOD (McGivern et al., Citation2017). The Vermont study only reported 5% of incorrect sequence errors in contrast to our studies in which this error exceeded 30% (Alipour et al., Citation2020; Ben Khelil et al., Citation2017; Haghighi et al., Citation2014; Haque et al., Citation2013; Qaddumi et al., Citation2017). One explanation could be that Vermont has a death investigation system that takes an active role in reviewing all DCs and providing feedback to certifiers. Also, Vermont’s EDRS requires first-time users to complete a brief tutorial about death certification and provides feedback to certifiers when information is missing or a cause of death is nonspecific (McGivern et al., Citation2017).

The ICOD was missing in about 13–15% of DCs as reported by two studies in Sudan, although in Nepal no DCs had missing ICOD (Maharjan et al., Citation2015). Most of the studies done on death certification worldwide are focusing on reporting errors in UCOD and ICOD and not on ACOD (El-Nour et al., Citation2007; Kheir et al., Citation2016), similar to our review in which only two studies in Sudan reported such errors.

In most of the studies, fewer than 15% of the examined DCs reported competing causes of death. This is consistent with the results in studies from Spain and USA in which this error did not exceed 10% (McGivern et al., Citation2017; Villar & Pérez-Méndez, Citation2007). However, in a study in Bangladesh, it exceeded 40%. One possible reason could be that the current format in Bangladesh does not comply with the WHO guidelines (Hazard et al., Citation2017).

Missing information about the time interval between the onset of condition and death for each diagnosis was reported in more than 90% of examined certificates in Tunisia and Palestine (Alipour et al., Citation2020; Ben Khelil et al., Citation2017; Qaddumi et al., Citation2017). This is similar to studies in Bangladesh and Canada in which 95 and 71% of DCs did not indicate the time interval respectively (Hazard et al., Citation2017; Myers & Farquhar, Citation1998). Timeline errors are very common.

Physicians usually use abbreviations and illegible handwriting in daily practice, but DCs are legal documents and are not always intended for audiences with a medical background. Committing such errors can be confusing to coders, public health researchers, and families. So, physicians should refrain from using abbreviations and illegible handwriting when filling out DCs. In our review these errors were common. An exception is a study by Aljerian (Citation2019) at the King Khalid University Hospital (KKUH), which found no abbreviations or illegible handwriting in the examined DCs (Aljerian, Citation2019). One explanation could be that the hospital administration of KKUH rejects any DC that contains abbreviations (Aljerian, Citation2019).

We found five studies addressing training of physicians on issuing of DCs. Training of physicians in the selected studies was either reported by physicians through questionnaires (Ali & Hamadeh, Citation2013; Al-Kubaisi et al., Citation2013; Mahdavi et al., Citation2015; Qaddumi et al., Citation2018), or was speculated by authors after detailed scrutiny of the medical section of DCs (Arif et al., Citation2014). Training did not exceed 25% in the selected studies, which might reflect a lack of the perceived importance of death certification accuracy by decision makers. However, more than 75% of physicians in studies in Iran and Bahrain expressed their need for further training (Ali & Hamadeh, Citation2013; Mahdavi et al., Citation2015). These findings are similar to a study conducted in the USA in 2004 in which only 24% of physicians received formal training and 81% requested further training (Lakkireddy et al., Citation2004).

In this systematic review we found that the lack of training was one of the most common difficulties facing physicians in filling DCs similar to a study in Nigeria (Izegbu & Onabanjo, Citation2006). This might indicate that a lack of training is an international issue. Almost all of our studies recommended designing and implementing suitable educational interventions and training of physicians on issuing DC as means to decrease the rate of errors. This is consistent with studies conducted in Canada, India, Nigeria and the USA (Azim et al., Citation2014; Izegbu & Onabanjo, Citation2006; Lakkireddy et al., Citation2004, Citation2007; Myers & Farquhar, Citation1998; Pritt et al., Citation2005; Wexelman et al., Citation2013). Similarly, in Spain authors found that the proportion of DCs with errors decreased significantly from 71% to 9% after an educational intervention. (Villar & Pérez-Méndez, Citation2007).

This systematic review raises several implications for physicians’ practice in filling out DCs. For one, we suggest more interventional studies to find ways to minimize death certification errors. Most of our included studies examined old DCs some of which were written many years ago. This might not reflect the actual current practice in death certification. Therefore, we recommend more studies to evaluate current practices in death certification. Secondly, we recommend the establishment of an authoritative body to review all DCs. Thirdly, we recommend that educational institutions emphasize the importance of DCs and their accurate completion. Finally, all practicing physicians who are charged with completing DCs should receive appropriate training.

This systematic review had several strengths. First, we utilized a predefined procedure for the systematic search and selection of the articles. Second, we used the Rayyan QCRI website for screening titles and abstracts of the retrieved studies. Third, four independent reviewers assessed the quality of the retrieved articles. However, our review also had a few limitations. First, we only searched few databases, and it was difficult to combine the results of individual studies as researchers used different classification systems of errors. The lack of a standard method for reporting the findings of individual studies resulted in substantial variation in the approaches used and difficulties in comparing results. As well, we limited our search to WHO EMR. One final limitation is that we only included cross-sectional studies. This may be justified by the fact that the majority of studies in this field in WHO EMR were cross-sectional.

In conclusion, we found substantial shortcomings in the death certification practices in the WHO EMR. Most of these can be attributed to the lack of training about completing DC forms. There is a pressing need to raise awareness of the importance of DC forms and for appropriate interventions to tackle physicians’ inaccuracies and to improve DC completion skills.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.8 KB)Additional information

Funding

References

- References starting with asterisk are for the studies included in the systematic review.

- *Abdulmalek, L. (2013). The accuracy of hospital death certificate in Benghazi, Libya. 2nd Libyan Scientific Conference of Medical Students and Young Doctors.

- *Abulfatih, N. M., & Hamadeh, R. R. (2010). A study of ill-defined causes of death in Bahrain: Determinants and health policy issues. Saudi Medical Journal, 31(5), 545–549.

- *Al-Kubaisi, N. J., Said, H., & Horeesh, N. A. (2013). Death certification practice in Qatar. Public Health, 127(9), 854–859. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2012.12.016.

- *Ali, N. M. A., & Hamadeh, R. R. (2013). Physicians’ knowledge and practices in death certificate completion in the Kingdom of Bahrain. Journal of the Bahrain Medical Society, 24(1), 17–23.

- *Alipour, J., Karimi, A., Hayavi Haghighi, M. H., Hosseini Teshnizi, S., & Mehdipour, Y. (2020). Death certificate errors in three teaching hospitals of Zahedan, southeast of Iran. Death Studies, 0(0), 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1801893.

- *Aljerian, K. (2019). Death certificate errors in one Saudi Arabian hospital. Death Studies, 43(5), 311–315. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2018.1461712.

- *Ansary, L. A., Esmaeil, S. A., & Adi, Y. A. (2012). Causes of death certification of adults: An exploratory cross-sectional study at a university hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Annals of Saudi Medicine, 32(6), 615–622. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5144/0256-4947.2012.615.

- *Arif, M., Hamad Rasool, S., & Ahmed, M. (2014). Assessment of accuracy of death certification in teaching hospital in a developing country. Journal of Fatima Jinnah Medical University, 8(2), 49–55.

- Azim, A., Singh, P., Bhatia, P., Baronia, A. K., Gurjar, M., Poddar, B., & Singh, R. K. (2014). Impact of an educational intervention on errors in death certification: An observational study from the intensive care unit of a tertiary care teaching hospital. Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology, 30(1), 78–81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-9185.125708.

- *Ben Khelil, M., Kamel, M., Lahmar, S., Mrabet, A., Falfoul, N. B., & Hamdoun, M. (2017). Death certificate accuracy in a Tunisian emergency department. Tunisie Medicale, 95(6), 422–428.

- *Binsaeed, A. A., Al-Saadi, M. M., Aljerian, K. A., Al-Saleh, S. A., Al-Hussein, M. A., Al-Majid, K. S., Al-Sani, Z. S., Al-Rabeeah, K. A., Arab, K. A., Al-Sheikh, K. A., & Ahamed, S. S. (2008). Assessment of the accuracy of death certification at two referral hospitals. Journal of Family & Community Medicine, 15(1), 43–50.

- *El-Nour, M., Abdel, Y., Ibrahim, H., & Ali, M. (2007). Evaluation of death certificates in the pediatric hospitals in Khartoum State during 2004. Sudanese Journal of Public Health, 2, 29–37.

- *Haghighi, M. H. H., Dehghani, M., Teshizi, S. H., & Mahmoodi, H. (2014). Impact of documentation errors on accuracy of cause of death coding in an educational hospital in Southern Iran. Health Information Management Journal, 43(2), 34–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12826/18333575.2013.0015.

- *Haque, A., Shamim, K., Siddiqui, N., Irfan, M., & Khan, J. (2013). Death certificate completion skills of hospital physicians in a developing country. BMC Health Services Research, 13, 205. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-205.

- Hazard, R. H., Chowdhury, H. R., Adair, T., Ansar, A., Quaiyum Rahman, A. M., Alam, S., Alam, N., Rampatige, R., Streatfield, P. K., Riley, I. D., & Lopez, A. D. (2017). The quality of medical death certification of cause of death in hospitals in rural Bangladesh: Impact of introducing the International Form of Medical Certificate of Cause of Death. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 688. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2628-y.

- Izegbu, M. C., & Onabanjo, O. (2006). Medical certification of death and indications for medico-legal autopsies: The need for inclusion in continue medical education in Nigeria. Scientific Research and Essays, 1(3), 061–064.

- Katsakiori, P. F., Panagiotopoulou, E. C., Sakellaropoulos, G. C., Papazafiropoulou, A., & Kardara, M. (2007). Errors in death certificates in a rural area of Greece. Rural and Remote Health, 7(4), 822.

- *Kheir, A., Abdelghani, A., Abdalrahman, I., & Dafaalla, M. (2016). Adequacy of death certification in a tertiary teaching hospital in Sudan. The Online Journal of Clinical Audits, 8(3).

- Kotabagi, R. B., Chaturvedi, R. K., & Banerjee, A. (2004). Medical certification of cause of death. Medical Journal, Armed Forces India, 60(3), 261–272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-1237(04)80060-1.

- Lakkireddy, D. R., Basarakodu, K. R., Vacek, J. L., Kondur, A. K., Ramachandruni, S. K., Esterbrooks, D. J., Markert, R. J., & Gowda, M. S. (2007). Improving death certificate completion: A trial of two training interventions. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(4), 544–548. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-006-0071-6.

- Lakkireddy, D. R., Gowda, M. S., Murray, C. W., Basarakodu, K. R., & Vacek, J. L. (2004). Death certificate completion: How well are physicians trained and are cardiovascular causes overstated? American Journal of Medicine, 117(7), 492–498. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.04.018.

- Madadin, M., Alhumam, A. S., Bushulaybi, N. A., Alotaibi, A. R., Aldakhil, H. A., Alghamdi, A. Y., Al-Abdulwahab, N. K., Assiri, S. Y., Alumair, N. A., Almulhim, F. A., & Menezes, R. G. (2019). Common errors in writing the cause of death certificate in the Middle East. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 68, 101864. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2019.101864.

- Maharjan, L., Shah, A., Shrestha, K. B., & Shrestha, G. (2015). Errors in cause-of-death statement on death certificates in intensive care unit of Kathmandu, Nepal. BMC Health Services Research, 15(1), 507. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1168-6

- *Mahdavi, A., Sedghi, S., Sadoghi, F., & Fard Azar, F. E. b. (2015). Assessing the awareness of agents involved in issuance of death certificates about death registration rules in Iran. Global Journal of Health Science, 7(5), 371–379. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v7n5p371

- Mathers, C. D., Fat, D. M., Inoue, M., Rao, C., & Lopez, A. D. (2005). Counting the dead and what they died from: An assessment of the global status of cause of death data. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 83(3), 171–177. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0042-96862005000300009.

- McGivern, L., Shulman, L., Carney, J. K., Shapiro, S., & Bundock, E. (2017). Death certification errors and the effect on mortality statistics. Public Health Reports, 132(6), 669–675. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354917736514.

- *Moussa, M. A. A., Shafie, M. Z., Khogali, M. M., El-Sayed, A. M., Sugathan, T. N., Cherian, G., Abdel-Khalik, A. Z. H., Garada, M. T., & Verma, D. (1990). Reliability of death certificate diagnoses. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 43(12), 1285–1295. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(90)90094-6.

- Munn, Z., Moola, S., Lisy, K., Riitano, D., & Tufanaru, C. (2015). Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 147–153. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054.

- Myers, K. A., & Farquhar, D. R. E. (1998). Improving the accuracy of death certification. Journal de L'Association Medicale Canadienne [CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal], 158(10), 1317–1323. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.270.12.1426c.

- Pritt, B. S., Hardin, N. J., Richmond, J. A., & Shapiro, S. L. (2005). Death certification errors at an academic institution. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, 129(11), 1476–1479. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1043/1543-2165(2005)129[1476:DCEAAA]2.0.CO;2.

- *Qaddumi, J. A. S., Nazzal, Z., Yacoub, A., & Mansour, M. (2018). Physicians' knowledge and practice on death certification in the North West Bank, Palestine: Across sectional study. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2814-y.

- *Qaddumi, J. A. S., Nazzal, Z., Yacoup, A. R. S., & Mansour, M. (2017). Quality of death notification forms in North West Bank/Palestine: A descriptive study. BMC Research Notes, 10(1), 154. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2469-0.

- *Sibai, A., Nuwayhid, I., Beydoun, M., & Chaaya, M. (2002). Inadequacies of death certification in Beirut: Who is responsible? Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 80(7), 555–561. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/S0042-96862002000700007

- Sondik, E. J., Anderson, J. R., Madans, J. H., Cox, L. H., Makuc, D. M., Williams, P. D., Hunter, E. L., Zinn, D. L., Rothwell, C. J., & Weed, J. A. (2003). Physicians’ handbook on medical certification of death. National Center for Health Statistics. CDC.

- Villar, J., & Pérez-Méndez, L. (2007). Evaluating an educational intervention to improve the accuracy of death certification among trainees from various specialties. BMC Health Services Research, 7(1), 183. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-7-183.

- Wexelman, B. A., Eden, E., & Rose, K. M. (2013). Survey of New York City resident physicians on cause-of-death reporting, 2010. Previous Chronic Disease, 10, E76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd10.120288.

- WHO | Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. (n.d). Retrieved December 23, 2020, from https://www.who.int/about/regions/emro/en/

- World Health Organization. (2004). ICD-10: international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: Tenth revision (Vol. 2, 2nd ed.). World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (WHO.) (n.d). WHO EMRO | CRVS assessments | Assesment | Civil registration and vital statistics. Retrieved December 23, 2020, from http://www.emro.who.int/civil-registration-statistics/assesment/crvs-assessments.html.

- Yasin, Y. M., Kerr, M. S., Wong, C. A., & Bélanger, C. H. (2020). Factors affecting nurses' job satisfaction in rural and urban acute care settings: A PRISMA systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(4), 963–979. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14293.