Abstract

Background

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic has been felt by all groups in society and people with intellectual disability are especially vulnerable due to underlying conditions/health problems, multi-morbidity, limitations in understanding, frailty and social circumstances. This places people with intellectual disability, their families and carers at increased risk of stress and in need of support.

Objective

To update and chart the evidence of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with intellectual disability, their families and carers reported within the research in 2021.

Methods

A scoping review of research published in 2021 across 7 databases.

Results

84 studies met the inclusion criteria, and the findings highlight people with intellectual disability are at a greater risk to COVID-19 health outcomes due to underlying health concerns and access issues. The effects of COVID-19 can be seen from a personal, social and health perspective for people with intellectual disability, their carers and families. However, COVID-19 did have some unanticipated benefits such as: less demand on time, greater opportunity to engage with people of value and building resilience.

Conclusions

COVID-19 presents many challenges but for people with intellectual disability compounding existing obstacles encountered in access issues, service provision and supports available. There is a need to identify and describe the experiences of people with intellectual disability, their families and carers in the medium-long term during COVID-19. Greater supports and evidence of effective interventions to promote health, deliver services and support individual with intellectual disability is needed as there is little evidence of clinical care for people with intellectual disability during COVID-19.

Key Messages

During pandemics the perspectives of people with intellectual disability, their carers and service providers are central to addressing systemic health care inequalities and poor-quality person-centred care.

Greater collaboration is needed to learn from pandemics in terms of health and social care policy improvements.

There remains a need for large scale studies that are representative of the broad spectrum of the intellectual disability population and examine Long-COVID in this group of people.

Introduction

Since the virus underlying the COVID-19 disease, SARS-CoV-2 was first diagnosed in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, the world continues to experience a life-threatening viral pandemic whose future remains dangerously unpredictable [Citation1]. As of 16th November 2022, there have been over 633 million confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 6,596,542 deaths reported to WHO and over 12.9 billion vaccine doses administered [Citation2]. Over the past two and a half years national governments and public health bodies have advised the public to adopt responsive care [Citation3]. Legal and health strategies have included guidelines on hand and respiratory hygiene, wearing face masks, social distancing, avoidance of gatherings and vaccination programmes [Citation4]. National and regional screening, lockdown and remaining at home strategies have also been implemented to manage the disease’s transmission [Citation5], with various success. In addition, the scientific community has moved to inform, support and monitor the international attempts to deal with the COVID-19 crisis [Citation6].

There is a continued need for further research on Covid-19 and people with intellectual disability. The limited studies that exist are small scale and not representative of the broad spectrum of the intellectual disability population. Furthermore, many studies were mainly undertaken in the early stages of the pandemic therefore the medium-long term effects of COVID-19 remains poorly understood. However, the existing literature informs us that the COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced and expanded the healthcare inequalities historically experienced by people with intellectual disability and is significantly contributing to an increase in their existing poor health outcomes. COVID-19 has exacerbated and heightened the experience of such existing vulnerabilities for people with intellectual disability. Vulnerabilities include increased physical, mental and social health issues; increased mortality rate; higher risk of developing serious illness due to limitations in understanding of COVID-19 risk reduction strategies and restricted capacity to social distance within congregate care settings as they depend on others for support with their everyday needs [Citation7].

Understanding the effects of COVID-19 on people with intellectual disability, their families and carers are central to ensuring person centred support to manage their needs during this prolonged pandemic and into the future. This is reinforced by the need for an ongoing process of evaluation and review of evolving evidence, for the continual reaction to the current ongoing pandemic and to inform policy decisions concerning possible future pandemics. This paper aims to update and build on the initial seminal review conducted by Doody and Keenan [Citation7] to update and chart the evidence of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with intellectual disability, their families and carers. By reviewing the literature on the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the paper identifies what professions and organizations serving people with intellectual disability can learn from the first two years of COVID-19 to enhance preparedness, detection and response in the future. Within this paper, intellectual disability is characterized by impaired intellectual functioning and learned behaviour, which affects various everyday social and practical competencies [Citation8].

Methods

A scoping review methodological approach was selected as it permits the presentation of a broad synthesis and mapping of the available literature focused on the question under investigation, not limited by study quality or design [Citation9]. Consequently, enabling the identification of the current body of knowledge and gaps in the literature [Citation10]. Utilizing a scoping review facilitates a systematic and transparent synthesis of the evidence and a rigorous map of the findings to present the extent and gravity of the literature, identify gaps and make recommendations [Citation11]. Arksey and O’Malley framework [Citation9] was adopted integrating updates by Levac et al. [Citation12] and Bradbury-Jones et al. [Citation11]. Arksey and O’Malley framework [Citation9] utilizing a five-step process: (i) identifying the research question, (ii) identifying relevant studies, (iii) study choice, (iv) plotting the data, and (v) arranging, summarizing and communicating the outcomes and is an interactive process where each step was returned to and advanced during the process. Results are conveyed as a narrative in conjunction with tables and diagram illustrations [Citation10].

Identification of the research question

To meet the aim of this review and ensure this update can be mapped to the original 2020 review the authors readdressed the original questions: (a) What effects are reported by people with intellectual disability and their carers? (b) What responses have been directed towards people with intellectual disability and their carers? and (c) What recommendations have been made regarding people with intellectual disability and their carers?

Identification of relevant studies

Given that this paper is an update to an existing review the original search process was adopted and replicated from the original 2020 search which utilized broad terms for intellectual disability and COVID-19 (). This rigorous research approach is deemed fit for purpose. Searches were conducted utilizing and selecting the Title OR Abstract and Keyword options. Each search string was searched individually and subsequent combined. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were created in advance () and utilized to uncover relevant papers across the seven electronic databases (CINAHL, Academic Search Complete, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Scopus, Cochrane). Within the screening process for inclusion within this review, research papers were assessed firstly, against having a specifically identified study sample as having intellectual disability and secondly, against the broad definition identified earlier in the introduction of this paper.

Table 1. Search terms.

Table 2. Inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Study selection

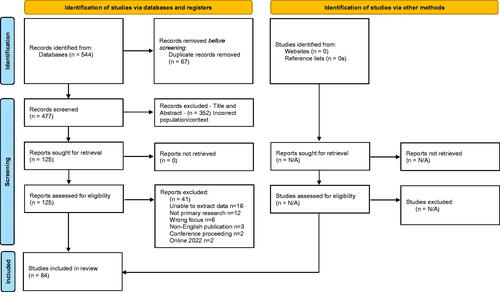

The search of the seven electronic databases yielded 544 papers which were transferred to Endnote and duplicates removed (n = 67) resulting in 477 papers remaining. Following this screening was conducted independently within Rayyan (Qatar Computing Research Institute) a web-tool for researchers working on reviews or synthesis projects to support the process of screening and selecting studies. Screening by the authors was guided by the inclusion criteria (). Initial screening of title and abstracts resulted in 352 papers being excluded and the remaining 125 papers were proceeded to full text review where they were assessed against the inclusion criteria. The authors then met to discuss remaining papers and form agreement, resulting in 42 papers being excluded and 84 meeting the criteria and therefore included in this review. A critical appraisal and risk of bias are not deemed essential and considered a choice in a scoping review [Citation13] and in this review were not conducted as they were not deemed necessary to meet the aim and objectives of this review. The selection and reporting process followed Tricco et al. [Citation14] Preferred Reporting Items for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-Sc-R) and PRISMA flow diagram [Citation15] (). Eight papers were included as they were returned as 2021 publications, being available online between June and December 2021. However, journal assignment to hard copy has occurred post January 2022, thus when finalising this paper, a 2022 reference was utilized, but the papers were included as they were in the public arena and met the inclusion criteria when the review and screening process were conducted.

Plotting the data

This scoping review aims to map the existing literature in terms of volume, nature, characteristics, and sources of evidence [Citation16]. This involved plotting and charting the data and extracting synopses from each paper and details were included in a data extraction table ().

Table 3. Data extraction.

Arranging, summarizing, and communicating the outcomes

The final step involves summarizing and communicating the findings. The findings of this review are presented under the three key questions identified in the first step of the review process. This scoping review generated 84 papers () of these 57 were quantitative, 21 qualitative and 6 mixed methods. The papers spanned many countries with 30 from the United Kingdom, 12 from the United States of America, 8 from the Netherlands, 6 from Canada, 5 from Spain, 4 from Poland, 2 each from Saudi Arabia/France/South Korea/China and 1 each from Australia/Austria/Germany/Ireland/Italy/North America, Asia, Europe/Pakistan/South Africa/Turkey/United States of America and Canada/United States of America and Chile.

Table 4. Study characteristics.

Results

What effects are reported by people with intellectual disability and their carers?

COVID-19 effected people with intellectual disability greatly [Citation21], challenges include much higher rates of mortality [Citation27,Citation30,Citation40,Citation53,Citation96], more severe course of the disease [Citation89] and more severe health outcomes [Citation58,Citation91,Citation96]. The most frequent underlying physical health conditions diagnosis were asthma, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), dementia, cerebral palsy, epilepsy and mental illness and/or addiction [Citation58]. Risk factors for COVID-19 diagnosis and mortality include intellectual disability, multiple comorbidities age, pre-existing conditions, large congregated residential settings and 24 hr skilled nursing staff [Citation27,Citation52–54,Citation91,Citation94,Citation96]. Risks were similar by ethnicity [Citation30]. However, higher rates of medical complications and mortality were associated with people with Down Syndrome [Citation58], especially from age 40 [48]; higher rates of hospital admissions and deaths were also associated with those who have severe to profound intellectual disability and cerebral palsy [Citation40,Citation96]. People with intellectual disability had a higher prevalence of avoidable hospitalizations and multiple comorbidities [Citation91]. The most common reported sign of COVID-19 was fever and frequent respiratory symptoms were dyspnea, hypoxemia and bronchial congestion [Citation86].

Negative effects included changes to routines; activities and social contacts; stress levels and reduced mental well-being; employment, including job losses; restrictions on social contacts and on activities [Citation18,Citation35,Citation36,Citation69,Citation77,Citation85,Citation99]. People with intellectual disability experienced the loss of, reduction in, or significant changes to routines and services received resulting in difficulties accessing services, medical treatment and medication [Citation36,Citation37,Citation85]. People with intellectual disability reported experiencing mental health issues including anxiety and depression; skin picking, obsessive compulsive behaviour, psychotic experiences and suicidal thoughts increased [Citation39,Citation68,Citation95].

However, people with intellectual disability also experienced benefits including enhanced resilience [Citation51]; digital inclusion [Citation36,Citation42,Citation63]; more time spent with people they value; improved health/well-being/fitness; and a slower pace of life [Citation36]. The new relaxed environment resulted in a reduction in challenging behaviours and improvements in sleep, obsessive and compulsive routines, seizures, mood and speech [Citation84]. Social distance and the removal of social pressure created unique opportunities for people with intellectual disability and their families to deepen meaningful relationships and spend quality time with and provide support to their friends, family and caregivers [Citation45,Citation68,Citation71,Citation77]. During lockdown, many people with intellectual disability reported feeling happy, safe and calm and valued support from services [Citation77] and people with Prader Willis Syndrome experienced weight loss [Citation66].

From a carer’s perspective parents focused on protecting their family, by attempting to stay healthy, avoid contacting COVID-19 and adapting to the significant challenges of a dynamic situation as best they could [Citation32,Citation33,Citation49,Citation94]. Parents reported experiencing increased mental health issues including anxiety, stress, distress, loneliness, depression and feeling less emotionally secure [Citation17,Citation48,Citation50,Citation72,Citation75,Citation84]. Parents struggled with social issues such as, financial challenges, food security, the loss of daily routines and healthy behaviours, lack of relevant guidance on COVID-19 regulations and service delivery [Citation17,Citation45,Citation48,Citation50,Citation71,Citation72,Citation76,Citation93,Citation97]. In addition, family demands changed with increased child caring burdens, reduced family and friends support, balancing family and working life, social isolation and increases in behavioural problems [Citation17,Citation45,Citation48,Citation50,Citation71,Citation72,Citation76,Citation93,Citation97], all of which effected family members mental health [Citation84]. Concerns were also expressed by families with regards to lockdowns, reduced or no service provision and poor government funding [Citation67,Citation72] and the negative effect these were having on their child’s health and well-being, their own employment or what would happen if they were unable to care for their child [Citation45,Citation50,Citation67,Citation72]. Parents worried that their adult children may not fully grasp the seriousness of COVID-19, were more vulnerable to the COVID-19 virus, could not identify self-infection and could have fatal outcomes of getting infected with COVID-19 [Citation50]. To manage the varied challenges some parents created house plans [Citation67], while others struggled to maintain appropriate supports for their child and increased their substance misuse and gambling to cope [Citation76]. Siblings expressed anxiety about the health and well‐being of their brother/sister and provided key support within families [Citation83].

The pandemic also created opportunities for families where parents reported experiencing adjustments and hopes [Citation50]. Parents valued the extra time available to bond with their family by sharing meals and playing board games [Citation67,Citation93]. Some parents built up their mental resilience overtime by implementing effective coping strategies such as exercise routines or hobbies [Citation83]. The change in routines and relaxed environment also resulted in less stressful mornings for family members, sleep ins and more rest [Citation93,Citation97]. Resulting in increased sibling well-being and improved behaviour, which reduced stress [Citation84].

At a service level COVID-19 continued to have a profoundly negative effect on service delivery as many closed, reduced provision or transferred partly or wholly to on-line. Neglect by services was also reported [Citation28] with staff experiencing poorer mental health, including stress, anxiety, depression and distress [Citation55,Citation59], with some requiring medication and therapy [Citation59]. Those over 45 were more likely to describe considerable clinical distress compared to younger workers [Citation59]. Mental health issues were due to fears of being infected by clients [Citation57], occupational stress because of the shortage of PPE, difficulties implementing infection control measures; redeployment, lack of access to testing, learning new roles and the use of new technologies without adequate training or support, inadequate tools or equipment to work remotely, demands at home, and changes due to COVID-19 [Citation55,Citation56,Citation92]. All of which effects the quality of support provided to people with intellectual disability in various ways but equally, other staff adopted well to the ever-evolving situation [Citation55,Citation59,Citation78].

What responses have been directed towards people with intellectual disability and their carers?

Some research identified that staff had the proper PPE to do their jobs safely; and were given the tools, training, and information to reduce risk of infection [Citation57]. Research focused on comparison of case-fatality rates [Citation54], COVID-19 vaccine willingness [Citation29,Citation43,Citation47,Citation60], intention to receive vaccine [Citation29,Citation47] and the fact some did not receive a service [Citation85]. In addition, the research highlighted that consultations, medications and multidisciplinary team input increased per week [Citation80] and an overall increase in psychotropic prescribing during lockdown [Citation70].

The responses evident within the literature are clearly weighted towards adapting service delivery and that professional carers employed varied methods to sustain contact with people with intellectual disabilities during the COVID-19 [Citation33,Citation90]. The use of technologies and novel strategies [Citation19] were clear and adapted to virtual service delivery [Citation25]. Virtual/telehealth methods were positively implemented across a wide range of technology platforms [Citation26,Citation62], enabling the use of online assessment methods [Citation20,Citation65,Citation73], therapy/support sessions [Citation73,Citation74,Citation79,Citation81], virtual service delivery/visits [Citation61,Citation77,Citation87] and support/consultations [Citation70,Citation73,Citation98].

However, there was a clear note of caution in using virtual/telehealth as some clients required carer assistance to access the technology [Citation78] or were unable to engage [Citation82] or did not understand the technology [Citation24] and that providing clients with a photo of the support person needs to be considered to enable an alliance to develop with clients [Citation82]. In addition, in person visits were facilitated where needed [Citation61,Citation77]. Thus, while there is clear use of technology it is not a substitute for face-to-face services/support [Citation64].

Staff adapted to extremely challenging circumstances [Citation28] and service delivery/ways of working [Citation25,Citation78,Citation92]. While technology assisted social networking, service provision [Citation75] and enabled more time to be spent with important people [Citation36] it uses in receiving information about COVID-19 [73] and maintaining social relationships for the quality of life of people with intellectual disability are also recognised [Citation64]. However, it was noted that nurses described being excluded from COVID-19 planning, and there was a deficiency of public health guidelines specific to persons with intellectual/development disability [Citation5].

What recommendations have been made regarding people with intellectual disability and their carers?

Pandemic planning must ensure people with intellectual disability receive comprehensive services and social supports to enhance their social contact, health and well-being [Citation35,Citation36]. Such responses must ensure access to these essential services [Citation37] and be done in a way that prioritizes the quality of life of the person [Citation38]. There is a need for greater supports from services [Citation17], specialized care [Citation95], support for families [Citation94,Citation95,Citation97] and the involvement of parents in their children’s care [Citation21]. In addition, siblings should be involved in efforts to distribute resources, gain feedback and support mental well-being [Citation83]. Care leavers [Citation68] and migrant families [Citation41] were two groups identified as requiring tailored support and consideration for independent living programme training. As with proper communicative support, individuals can cope effectively with considerable restrictions imposed by a pandemic/lockdown [Citation79,Citation88].

From a practice perspective clinicians should be aware of COVID-19 symptoms in people with intellectual disability [Citation86], health services need to support prompt access to COVID-19 testing [Citation96] and policy/guidance needs to prioritize people with intellectual disability for vaccine [Citation29,Citation91,Citation96]. However, targeted action may be needed to address lower vaccination uptake and vaccination strategies need to address beliefs that the vaccine is unnecessary [Citation61]. Concerns were raised in the research as to the possibility of systemic and professional bias and discrimination affecting treatment decisions for people with intellectual disability [Citation23]. Thus, barriers to care need to be overcome to ensure equity of services [Citation23] and to address care professionals’ attitudes towards, and needs recognition of, people with intellectual disability [Citation31]. In addition, the research highlights that the Clinical Frailty Scale is not suitable to evaluate frailty in individuals with intellectual disability, with potential dramatic consequences for triage and decision-making during the COVID-19 [Citation34]. Furthermore, due to the prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in people with intellectual disability there is a need for screening and psychological support [Citation39] and an urgent requirement for community-based services to address psychosocial challenges [Citation50].

The use of telehealth procedures may be appropriate for a wide range of services and assessments which may ease the burden of travel and eliminate the need for onsite assessment [Citation26]. Telerehabilitation could be a valid means for the rehabilitation of specific cognitive skills [Citation62] and virtual platforms are feasible to deliver therapeutic programmes [Citation87]. However, telehealth is not an option for all as some need face-to-face and other require high level of support to engage [Citation97]. Thus, for some adults with intellectual disability support to improve or gain digital confidence and access is required [Citation36] and support staffs own digital skills are often insufficient [Citation73]. Where client require their carer to help them understand what is being discussed or directed there are confidentiality and engagement issues to be addressed [Citation82].

From a research perspective there is a need for research to identify the ways in which people with intellectual disabilities encounter COVID-19 and experience the disease [Citation44] and longitudinal research to understand the medium-long term effects of COVID-19 on people with intellectual disability, their parental caregivers and their siblings [Citation22]. Furthermore, from a policy perspective intellectual disability nurses must be engaged in public health planning and policy development to safeguard that basic care needs of people with intellectual disability are met [Citation5].

Discussion

The aim of this scoping review was to update and chart the evidence of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with intellectual disability, their families and carers reported within the research in 2021. This paper, through identifying the evidence, highlights what we can learn to limit the effect of COVID-19 for people with intellectual disability and deliver suitable care for this population in the current and future pandemics. In this review, a range of experiences are reported related to persons with intellectual disability, their family and carers. This review highlights that people with intellectual disability may be under reflected in national policy, strategy, and the responses to COVID-19 [Citation18] and may be viewed as ‘forgotten within society and the systems around them’ [Citation28, p. 591]. While some countries have intellectual disability reflected in its policy and adopt the 2006 UN Convention of Rights [Citation100] there is a long history of marginalization of people with intellectual disability and their carers, which may have strengthened unabated during the current pandemic. This may be driven by poor attitude towards or limited awareness of intellectual disability. The general population’s attitude towards people with intellectual disability is only slightly positive with adults (35–60 yrs.) articulating the most negative views [Citation31]. What is evident is that the more that individuals know about intellectual disability, the more contact they have with intellectual disability and the type of intellectual disability effects the public’s attitude [Citation101]. From a healthcare professionals’ perspective their attitude to intellectual disability is affected by a fear of the unknown; the complexity of patient needs and the lack of education regarding the health needs of people with intellectual disability [Citation102]. However, it is noted that younger healthcare professionals are more likely to feel that those with intellectual disability should be empowered to take control of their lives whereas older healthcare professionals are more likely to believe that individuals with intellectual disability are vulnerable [Citation103] and that others should speak on their behalf. This suggests a generational difference in attitudes, and the need for educational interventions to improve attitudes among older healthcare professionals to address pre-existing bias/attitudes regarding care provision [Citation103]. However, one must recognize recent advances to support and engage health and social care workforce to better support people with an intellectual disability and autistic such as the Oliver McGowan mandatory training on learning Disability and autism in the UK. While such advances are welcome it is worthy to note this has been in response to highlighted poor care [Citation104].

People with intellectual disability have experienced profound disparities in healthcare, which may have added to excess mortality in this group [Citation23]. The most alarming health disparity recognized for people with intellectual disability is the increased risk of early mortality [Citation105,Citation106]. People with intellectual disability experiences of COVID-19 are excessively higher mortality than that of the general population [Citation93], resulting in a profound effect on their health, quality of life and well-being. As a result, they are particularly vulnerable to the physical, social and mental consequences of the pandemic. Within this review mortality, severity and outcome of COVID-19 were factors for people with intellectual disability and those with underlying conditions. People with Down Syndrome, severity of intellectual disability and being over 40 years of age were more susceptible to Covid-19 and had poorer outcomes [Citation40,Citation41,Citation58]. Therefore, there is a clear need to address the social, health and well-being supports necessary to enable the person with intellectual disability maintain good health. As supports play a vital protective role in facilitating psychosocial outcomes for individuals with intellectual disability there is a need for healthcare practitioners, services and policymakers to provide accessible resources and to develop better support systems to address these gaps [Citation35]. This is essential as this review highlights there was a deficiency of public health guidelines specific to persons with intellectual/development disability and nurses resulting in this group being excluded from much COVID-19 planning [Citation5]. However, thoughtful consideration is warranted regarding the individual supports and resources needed to alleviate the challenges off the COVID-19 crises such as voluntary groups, neighbourhood supports, safe visiting, remote communications [Citation107,Citation108].

This vulnerability the lack of policy, poor attitudes and marginalization can create greater health disparity for people with intellectual disability. Given that this review did not identify the availability of specific public health prevention and protection measures for people with intellectual disability it may be difficult to identify the lessons learned regarding the spread of future viruses and prevention of future global pandemics. While the importance of having accessible information that explains public health prevention and protection measures is accepted [Citation109,Citation110], there are studies indicating people with intellectual disability understood the rules about COVID-19, wearing face masks, shielding, handwashing and social distancing, [Citation18] there is little research evidence examining the accessibility and effectiveness of information and support provided to further help explain the restrictions caused by COVID-19. Accessible information and support are important for people with intellectual disability in relation to COVID-19 vaccine awareness and uptake. While this review highlights a willingness or intention for people with intellectual disability to receive a vaccine [Citation43,Citation47,Citation61]. The question as to whether people with intellectual disability should be prioritized for vaccination [Citation91,Citation96] and the need for targeted activity to address vaccination strategies to address families, professionals and people with intellectual disability beliefs and understanding [Citation61] remains scant. In addition, in terms of vaccination consideration needs to be given to the likelihood of a person with intellectual disability dislike to needles or refusal, which is not to be unexpected within this cohort due to a fear of needles [Citation111,Citation112]. Furthermore, concerns around informed consent and the fact that consent procedures are often found to be inadequate [Citation113] within this cohort makes practice challenging. This literature review found no research addressing this gap in order to develop and share evidence for practice and families.

Generally, within this review it is clear there is a need to recognize and respond to the symptoms of COVID-19 [Citation91], early access to screening [Citation114,Citation115] and a clear need for psychological support through independent living skill programmes and screening for anxiety and depression [Citation39,Citation55,Citation59]. Psychological support needs to consolidate and enhance existing adaptive skills and reduce the negative effects of COVID-19 on the persons emotional well-being and quality of life. Supports appropriate may be around daily routine activities; personal hygiene (safety measures, use of personal protective equipment), clothing and eating (cleanliness of clothing and linen, cutlery, plates and glasses, distancing during meals). Educational interventions to enable understanding of COVID-19, infection and avoidance of infection and procedures adopted (protection equipment, adaptation to the setting, social distancing). Individualized support using modelling, behavioural techniques, peer support/learning and behavioural self-regulation skills. All support information and instruction should be provided utilizing visual aids and verbal instruction that is continually repeated in a clear and accessible language, appropriate to the functioning levels of person. Thus, addressing the attention, memory and learning functions, communication skills, emotional skills, social skills and independence skills of the person.

Evident within this review was that COVID-19 had a clear impact on disability services and saw the introduction of virtual services [Citation116] and this means of support may be preferred over time [Citation117]. As within this review the relationship, accessibility, assistance/support and confidentiality issues were evident which will affect use in the future. Therefore, proceeding with caution is advised as despite the necessity to adopt this form of support while under COVID-19 restrictions, it remains essential to collaborate with the individual as to the approach best suited to supporting them. As the relationship itself is a crucial essential element of in-person support that may assist more effective communication and better enable the development of meaningful therapeutic relationships [Citation61]. The concerns regarding the use and availability of virtual services are justified as concerns regarding confidentiality [Citation118], infrastructure within disability services (availability of reliable broadband and IT/mobile resources) [Citation116], IT literacy of staff, families and persons with intellectual disability [Citation116] and ensuring access, skill, knowledge and resource are meaningful for all [Citation119]. These are real issues within practice and the lives of all concerned [Citation116,Citation118].

The initial scoping review of the 2020 literature [Citation7] in this area identified a flood of opinion pieces and discussions, with only 16 (6%) of 268 papers initially identified in the databases being peer reviewed research papers. While this may have been understandable at the beginning of a pandemic, it is concerning that over two years later the trend continues to grow unabated as shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (). Redirecting greater energies to research and less to professional debates and polemic activities may better serve people with intellectual disability and their carers in this and future pandemics. In this updated review, similar to that of the 2020 review of studies [Citation7], a large quantity of the published studies in 2021were undertaken in the early stages of the pandemic therefore the medium-long term effects of COVID-19 are still poorly understood. The authors also note a trend in the number of studies published since 2020, for example on university and organization websites, which have not gone through the academic rigours of peer reviewed publication within the past two years. Furthermore, a number of studies were excluded because they reported links to the pandemic even though their data was gathered pre the existence of COVID-19.

Limitations

While this review used precise, transparent methods based on study and reporting guidelines [Citation9,Citation14], no quality appraisal was conducted as the focus of this review were to update and map the evidence. Thus, this paper only offers a descriptive account of available information. Furthermore, there was no patient and public involvement and there is an opportunity for engagement, potentially following published guidance on stakeholder involvement in systematic reviews [Citation120]. In addition, most papers in this review describe (1) data that was collected early in the early stages of the pandemic and additional data is essential to identify the medium-long term effects of COVID-19, (2) small sample were often utilized which were not fully representative of the intellectual disability population (socioeconomic, level of disability etc), (3) self-reporting measures were utilized and mainly administered online which limits responses to individuals with internet access and connectivity, and also those with a level of literacy, (4) numerous data collection tools were utilized and may not validated or psychometric proprieties and inferential analysis not conducted, (5) no pre-COVID-19 measures exist for comparisons analysis to be conducted and (6) most research was carried out on people in developed countries resulting in predominantly western care perspectives being promoted and continuing albeit unintentionally the historical trend of excluding the experiences of the vast majority of people with intellectual disability and their cares from the prevailing international narrative.

Conclusion

Overall, this review reiterates the serious health risk of COVID-19 (health outcomes, hospitalization, mortality), social implications (loss of routines, activities, social contact) and mental health implications (stress, anxiety, obsessive compulsive behaviours) for people with intellectual disability. Positive aspects were identified for families and persons with intellectual disability (enhanced resilience, digital inclusion, valued time with loved ones, well-being, exercise, relaxed). However, families had continually to balance the worries and strains of the pandemic (anxiety, stress, loneliness, financial, carer burden). From a staff and service perspective COVID-19 brought a sudden pivoting of service provision and while the benefits identified were experienced by some this was a time of stress and worry (anxiety, occupational stress, difficulties in implementing infection control measures, shortage of PPE). Of note within this review is the fact that barriers to the use of telehealth are evident (access to technology, access to internet, understanding of technology, support/facilitation). This raise the issue of support needed and confidentiality that needs to be addressed for this vulnerable population. In addition, access and support for vaccination is warranted in relation to accessible information and support strategies to address fear of needles. However, this review highlights the absence of nurses within the decision making, policy framing and implementation of health measures to support people with intellectual disability. Thus, there is little research about supportive strategies for people with intellectual disability in relation to care strategies, health interventions, health promotion, health education, accessible information and vaccination uptake. This review accentuates the need to capture the rich perspectives and experiences of the people with intellectual disability over the medium-long term to understand the specific needs and successful support strategies to ensure a rights-based person-centred approach is prioritized. Healthcare practitioners also need to broaden their awareness and practice to adopt a more collaborative approach to working that includes people with intellectual disability, their family and cares. Moreover, there is a need for public health advice, guidelines and careful application of quality infection control measures for people with intellectual disability.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval was necessary for the conduct of this review.

Author contributions

Author PK led the paper and authors PK and OD made equal and substantial contribution to the conception, design, analysis and interpretation of the data; the drafting of the paper, revising it critically for intellectual content; and the final approval of the version to be published. PK and OD give permission for the final approval of the version to be submitted and no other authors were involved with this paper.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22.2 KB)Data availability statement

No data are available other than that reported in this review and available in original published papers used in this review.

Disclaimer

The contents of this manuscript, including figures and tables, are those of the authors. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the viewpoints of the Universities they work for.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Rommel A. Covid-19–an unexpected journey. Argumentum. 2022;18:1–39.

- World Health Organisation. 2022. Who coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Geneva: world Health Organization. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019?adgroupsurvey={adgroupsurvey}&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIjc-Pk9Da-QIVwu7tCh01EQfiEAAYASAAEgJ5VPD_BwE.

- Burke S, Parker S, Fleming P, et al. Building health system resilience through policy development in response to COVID-19 in Ireland: from shock to reform. Lancet Regional Health-Europe. 2021;9:100223.

- Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2020;395(10242):1973–1987.

- Desroches ML, Ailey S, Fisher K, et al. Impact of COVID-19: nursing challenges to meeting the care needs of people with developmental disabilities. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(1):101015.

- Maher B, Van Noorden R. How the COVID pandemic is changing global science collaborations. Nature. 2021;594(7863):316–319.

- Doody O, Keenan PM. The reported effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with intellectual disability and their carers: a scoping review. Ann Med. 2021;53(1):786–804.

- Schalock RL, Luckasson R, Tasse MJ. 2021. Intellectual disability: definition, classification, and systems of supports. 12th ed. Silver Spring (MD): American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

- Munn Z, Peters MD, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143.

- Bradbury-Jones C, Aveyard H, Herber OR, et al. Scoping reviews: the PAGER framework for improving the quality of reporting. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2022;25(4):457–470.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Sci. 2010;5(1):69.

- Pollock D, Davies EL, Peters MD, et al. Undertaking a scoping review: a practical guide for nursing and midwifery students, clinicians, researchers, and academics. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(4):2102–2113.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):1–1.

- Daudt HM, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):48.

- Abuzaid SMO, Taibah University, Special Education, Saudi Arabia. Consequences of coronavirus as a predictor of emotional security among mothers of children with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabl Diagn Treat. 2021;9(4):390–396.

- Amor AM, Navas P, Verdugo MÁ, et al. Perceptions of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities about COVID‐19 in Spain: a cross‐sectional study. J Intell Disabil Res. 2021;65(5):381–396.

- Araten-Bergman T, Shpigelman CN. Staying connected during COVID-19: family engagement with adults with developmental disabilities in supported accommodation. Res Dev Disabil. 2021;108:103812.

- Ashworth M, Palikara O, Burchell E, et al. Online and face-to-face performance on two cognitive tasks in children with Williams syndrome. Front Psychol. 2021;11:594465.

- Athbah SY. Covid-19 impact on children with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability: study in Saudi Arabia. JESR. 2021;11(6):78–90.

- Bailey T, Hastings RP, Totsika V. COVID‐19 impact on psychological outcomes of parents, siblings and children with intellectual disability: longitudinal before and during lockdown design. J Intell Disabil Res. 2021;65(5):397–404.

- Baksh RA, Pape SE, Smith J, et al. Understanding inequalities in COVID-19 outcomes following hospital admission for people with intellectual disability compared to the general population: a matched cohort study in the UK. BMJ Open. 2021;11(10):e052482.

- Bente BE, Van ‘t Klooster JWJR, Schreijer MA, et al. The Dutch COVID-19 contact tracing app (the CoronaMelder): usability study. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(3):e27882.

- Bond C, Stacey G, Gordon E, et al. COVID-19: experiences and contributions of learning disability nurses during the first wave of the pandemic. Learn Disabil Pr. 2021;24(4):17–25.

- Bullard L, Harvey D, Abbeduto L. Exploring the feasibility of collecting multimodal multiperson assessment data via distance in families affected by fragile X syndrome. J Telemed Telecare. 2021;Online paper identifier - 1357633X211003810.

- Carey IM, Cook DG, Harris T, et al. Risk factors for excess all-cause mortality during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in England: a retrospective cohort study of primary care data. PLOS One. 2021;16(12):e0260381.

- Chemerynska N, Marczak M, Kucharska J. What are the experiences of clinical psychologists working with people with intellectual disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Res Intellect Disabil. 2022;35(2):587–595.

- MacKenna B, Curtis HJ, Walker AJ, et al.; All OpenSAFELY study authors. Trends and clinical characteristics of 57.9 million COVID-19 vaccine recipients: a federated analysis of patients’ primary care records in situ using OpenSAFELY. Br J Gen Pract. 2022;72(714):e51–e62.

- Das-Munshi J, Chang CK, Bakolis I, et al. All-cause and cause-specific mortality in people with mental disorders and intellectual disabilities, before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;11:100228.

- Domagała-Zyśk E. Attitudes of different age groups toward people with intellectual disability during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:591707.

- Embregts P, Heerkens L, Frielink N, et al. Experiences of mothers caring for a child with an intellectual disability during the COVID-19 pandemic in The Netherlands. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2021;65(8):760–771.

- Embregts PJCM, Tournier T, Frielink N. The experiences of psychologists working with people with intellectual disabilities during the COVID-19 crisis. Res Intellect Disabil. 2022;35(1):295–298.

- Festen DAM, Schoufour JD, Hilgenkamp TIM, et al. Determining frailty in people with intellectual disabilities in the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Policy Practic Intellect Disabil. 2021;18(3):203–206.

- Fisher MH, Sung C, Kammes RR, et al. Social support as a mediator of stress and life satisfaction for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2022;35(1):243–251.

- Flynn S, Caton S, Gillooly A, et al. The experiences of adults with learning disabilities in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: qualitative results from wave 1 of the coronavirus and people with learning disabilities study. TLDR. 2021;26(4):224–229.

- Flynn S, Hatton C. Health and social care access for adults with learning disabilities across the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. TLDR. 2021;26(3):174–179.

- Friedman C. The COVID-19 pandemic and quality of life outcomes of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(4):101117.

- Gacek M, Krzywoszanski L. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in students with developmental disabilities during COVID-19 lockdown in Poland. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:576867.

- Gale TM, Boland B. COVID-19 deaths in a secondary mental health service. Comph Psychiat. 2021;111:152277.

- Geuijen PM, Vromans L, Embregts PJCM. A qualitative investigation of support workers’ experiences of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Dutch migrant families who have children with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2021;46(4):300–305.

- Gil-Llario MD, Díaz-Rodríguez I, Morell-Mengual V, et al. Sexual health in Spanish people with intellectual disability: the impact of the lockdown due to COVID-19. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2021;19(3):1217–1227.

- Hatton C, Bailey T, Bradshaw J, et al. The willingness of UK adults with intellectual disabilities to take COVID-19 vaccines. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2021;65(11):949–961.

- Heslop P, Byrne V, Calkin R, et al. Deaths of people with intellectual disabilities: analysis of deaths in England from COVID-19 and other causes. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2021;34(6):1630–1640.

- Honingh AK, Koelewijn A, Veneberg B, et al. Implications of COVID-19 regulations for people with visual and intellectual disabilities: lessons to learn from visiting restrictions. Policy Practice Intel Disabi. 2022;19(1):64–71.

- Hüls A, Costa ACS, Dierssen M, et al. Medical vulnerability of individuals with down syndrome to severe COVID-19-data from the trisomy 21 research society and the UK ISARIC4C survey. EClinicalMed. 2021;33:100769.

- Iadarola S, Siegel JF, Gao Q, et al. COVID-19 vaccine perceptions in New York state’s intellectual and developmental disabilities community. Disabil Health J. 2022;15(1):101178.

- Kaya A, Sahin CH. I did not even receive even a phone call from any institution: experiences and recommendations related to disability during COVID-19. Int J Dev Disabil. 2021;Online paper identifier - 20473869.2021.1978268

- Kim MA, Yi J, Sung J, et al. Changes in life experiences of adults with intellectual disabilities in the COVID-19 pandemics in South Korea. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(4):101120.

- Kim MA, Yi J, Jung SM, et al. A qualitative study on parents’ concerns about adult children with intellectual disabilities amid the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2021;34(4):1145–1155.

- Lake JK, Jachyra P, Volpe T, et al. The wellbeing and mental health care experiences of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities during COVID-19. J Ment Health Res Intellect Disabil. 2021;14(3):285–300.

- Landes SD, Turk MA, Damiani MR, et al. Risk factors associated with covid-19 outcomes among people with intellectual and developmental disabilities receiving residential services. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2112862.

- Landes SD, Turk MA, Wong AWWA. COVID-19 outcomes among people with intellectual and developmental disability in California: the importance of type of residence and skilled nursing care needs. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(2):101051.

- Landes SD, Turk MA, Ervin DA. COVID-19 case-fatality disparities among people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: evidence from 12 US jurisdictions. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(4):101116.

- Langdon PE, Marczak M, Clifford C, et al. Occupational stress, coping and wellbeing among registered psychologists working with people with intellectual disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2022;47(3):195–205.

- Lee RLT, West S, Tang ACY, et al. A qualitative exploration of the experiences of school nurses during COVID-19 pandemic as the frontline primary health care professionals. Nurs Outlook. 2021;69(3):399–408.

- LoPorto J, Spina K. Risk perception and coping strategies among direct support professionals in the age of COVID-19. J Soc Behav Health Sci. 2021;15(1):201–216.

- Lunsky Y, Durbin A, Balogh R, et al. Covid-19 positivity rates, hospitalizations and mortality of adults with and without intellectual and developmental disabilities in Ontario, Canada. Disabil Health J. 2022;15(1):101174.

- Lunsky Y, Bobbette N, Chacra MA, et al. Predictors of worker mental health in intellectual disability services during COVID‐19. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2021;34(6):1655–1660.

- Lunsky Y, Kithulegoda N, Thai K, et al. Beliefs regarding COVID-19 vaccines among Canadian workers in the intellectual disability sector prior to vaccine implementation. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2021;65(7):617–625.

- Lunsky Y, Bobbette N, Selick A, et al. The doctor will see you now: direct support professionals’ perspectives on supporting adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities accessing health care during COVID-19. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(3):101066.

- Maggio MG, Cuzzola F, Calatozzo M, et al. Improving cognitive functions in adolescents with learning difficulties: a feasibility study on the potential use of telerehabilitation during covid-19 pandemic in Italy. J Adol. 2021;89(1):194–202.

- McCausland D, Luus R, McCallion P, et al. The impact of COVID‐19 on the social inclusion of older adults with an intellectual disability during the first wave of the pandemic in Ireland. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2021;65(10):879–889.

- McKenzie K, Murray GC, Martin R. It’s been adapted rather than impacted: a qualitative evaluation of the impact of covid-19 restrictions on the positive behavioural support of people with an intellectual disability and/or autism. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2021;34(4):1089–1097.

- McNally Keehn R, Enneking B, James C, et al. Telehealth evaluation of pediatric neurodevelopmental disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinician and caregiver perspectives. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2022;43(5):262–272.

- Mosbah H, Coupaye M, Jacques F, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on the mental and physical health of adults with Prader-Willi syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16(1):202.

- Munir MM, Rubaca U, Munir MH, et al. An analysis of families’ experiences with young children with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDDs) during COVID-19 lockdown in Pakistan. Int Multidiscip J Soc Sci. 2021;10(1):81–103.

- Mupaku WM, van Breda AD, Kelly B. Transitioning to adulthood from residential childcare during COVID‐19: experiences of young people with intellectual disabilities and/or autism spectrum disorder in South Africa. Br J Learn Disabil. 2021;49(3):341–351.

- Murray GC, McKenzie K, Martin R, et al. The impact of COVID-19 restrictions in the United Kingdom on the positive behavioural support of people with an intellectual disability. Br J Learn Disabil. 2021;49(2):138–144.

- Naqvi D, Perera B, Mitchell S, et al. COVID-19 pandemic impact on psychotropic prescribing for adults with intellectual disability: an observational study in English specialist community services. BJPsych Open. 2021;8(1):e7.

- Navas P, Verdugo MÁ, Martínez S, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the burden of care of families of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Res Intellect Disabil. 2022;35(2):577–586.

- Navas P, Amor AM, Crespo M, et al. Supports for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic from their own perspective. Res Dev Disabil. 2021;108:103813.

- Oudshoorn CEM, Frielink N, Riper H, et al. Experiences of therapists conducting psychological assessments and video conferencing therapy sessions with people with mild intellectual disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Dev Disabil. 2021;Online paper identifier - 20473869.2021.1967078.

- Parchomiuk M. Care and rehabilitation institutions for people with intellectual disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic: polish experiences. Int Soc Work. 2021;Online paper identifier - 00208728211060471.

- Patel V, Perez‐Olivas G, Kroese BS, et al. The experiences of carers of adults with intellectual disabilities during the first COVID‐19 lockdown period. Policy Practice Intel Disabi. 2021;18(4):254–262.

- Paulauskaite L, Farris O, Spencer HM, et al. My son can’t socially distance or wear a mask: how families of preschool children with severe developmental delays and challenging behavior experienced the COVID-19 pandemic. J Ment Health Res Intellect Disabil. 2021;14(2):225–236.

- Peacock-Brennan S, Stewart K, Angier RJ, et al. The experience of COVID-19 “lockdown” for people with a learning disability: results from surveys in Jersey and Guernsey. TLDR. 2021;26(3):121–129.

- Power N, Dolby R, Thorne D. Reflecting or frozen: the impact of covid-19 on art therapists working with people with a learning disability. Int J Art Ther. 2021;26(3):84–95.

- Purrington J, Nye A, Beail N. Exploring maintaining gains following therapy during the coronavirus pandemic with adults with an intellectual disability. AMHID. 2021;15(6):253–268.

- Rauf B, Sheikh H, Majid H, et al. COVID-19-related prescribing challenge in intellectual disability. BJPsych Open. 2021;7(2):E66.

- Rawlings GH, Wright KP, Rolling K, et al. Telephone-delivered compassion-focused therapy for adults with intellectual disabilities: a case series. AMHID. 2021;15(2/3):89–103.

- Rawlings GH, Gaskell C, Rolling K, et al. Exploring how to deliver videoconference-mediated psychological therapy to adults with an intellectual disability during the coronavirus pandemic. AMHID. 2021;15(1):20–32.

- Redquest BK, Tint A, Ries H, et al. Exploring the experiences of siblings of adults with intellectual/developmental disabilities during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2021;65(1):1–10.

- Rogers K, McAliskey S, McKinney P, et al. Managing an outbreak of COVID-19 in a learning disability setting. Learn Disabil Pract. 2021;25(3):ldp.2021.e2116.

- Rosencrans M, Arango P, Sabat C, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health, wellbeing, and access to services of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Res Dev Disabil. 2021;114:103985–103985.

- Rousseau MC, Hully M, Milh M, et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 infection in polyhandicapped persons in France. Arch Pediatrie. 2021;28(5):374–380.

- Ryzhikov K. Virtual therapeutic horticulture: a social wellness program for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Acta Hortic. 2021;1330:55–62.

- Salzner J, Dall M, Weber C, et al. Deaf residents with intellectual disabilities during the first covid-19 associated lockdown. J Deaf Stud Deaf Edu. 2021;26(4):556–559.

- Sanchez-Larsen A, Conde-Blanco E, Viloria-Alebesque A, et al. COVID-19 prevalence and mortality in people with epilepsy: a nation-wide multicenter study. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;125:108379–108379.

- Scheffers F, Moonen X, van Vugt E. Assessing the quality of support and discovering sources of resilience during COVID-19 measures in people with intellectual disabilities by professional carers. Res Dev Disabil. 2021;111:103889.

- Schott W, Tao S, Shea L. COVID-19 risk: adult medicaid beneficiaries with autism, intellectual disability, and mental health conditions. Autism. 2022;26(4):975–987.

- Sheehan R, Dalton-Locke C, Ali A, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental healthcare and services: results of a UK survey of front-line staff working with people with intellectual disability and/or autism. BJPsych Bull. 2021;44(4):201–207.

- Suarez-Balcazar Y, Mirza M, Errisuriz VL, et al. Impact of covid-19 on the mental health and well-being of Latinx caregivers of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. IJERPH. 2021;18(15):7971.

- Vereijken FR, Giesbers SAH, Jahoda A, et al. Homeward bound: exploring the motives of mothers who brought their offspring with intellectual disabilities home from residential settings during the COVID-19 pandemic. Res Intellect Disabil. 2022;35(1):150–159.

- Wieting J, Eberlein C, Bleich S, et al. Behavioural change in Prader–Willi syndrome during COVID-19 pandemic. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2021;65(7):609–616.

- Williamson EJ, McDonald HI, Bhaskaran K, et al. Risks of covid-19 hospital admission and death for people with learning disability: population based cohort study using the OpenSAFELY platform. BMJ. 2021;374:n1592.

- Wolstencroft J, Hull L, Warner L, IMAGINE-ID consortium, et al. We have been in lockdown since he was born’: a mixed methods exploration of the experiences of families caring for children with intellectual disability during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e049386.

- Wos K, Kamecka-Antczak C, Szafrański M. Remote support for adults with intellectual disability during COVID-19: from a caregiver’s perspective. Policy Practice Intel Disabi. 2021;18(4):279–285.

- Yuan YQ, Ding JN, Bi N, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behaviour among children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities during the COVID-19 lockdown in China. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2021;66(12):913–923.

- United Nation. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD); 2006. Available from: www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html.

- Wang Z, Xu X, Han Q, et al. Factors associated with public attitudes towards persons with disabilities: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–5.

- Smith JJ, Co L. Attitudes and experiences of general practitioners who provided health care for people with intellectual disabilities: a South Australian perspective. Res Pract Intellect Dev Disabil. 2021;8(1):25–36.

- Breau G, Baumbusch J, Thorne S, et al. Primary care providers’ attitudes towards individuals with intellectual disability: associations with experience and demographics. J Intellect Disabil. 2021;25(1):65–81.

- National Health Service. The Oliver McGowan mandatory training on learning disability and autism. National Health Service Health Education England; 2022. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/learning-disability/current-projects/oliver-mcgowan-mandatory-training-learning-disability-autism

- Hirvikoski T, Boman M, Tideman M, et al. Association of intellectual disability with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in Sweden. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2113014.

- Doyle A, O’Sullivan M, Craig S, et al. People with intellectual disability in Ireland are still dying young. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2021;34(4):1057–1065.

- Jeste S, Hyde C, Distefano C, et al. Changes in access to educational and healthcare services for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities during COVID‐19 restrictions. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2020;64(11):825–833.

- Zaagsma M, Volkers KM, Swart EA, et al. The use of online support by people with intellectual disabilities living independently during COVID‐19. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2020;64(10):750–756.

- Alexander R, Ravi A, Barclay H, et al. Guidance for the treatment and management of COVID‐19 among people with intellectual disabilities. J Policy Practic Intellect Disabil. 2020;17(3):256–269.

- United Nations. 2020. Policy brief: education during COVID-19 and beyond. New York: United Nations.

- Taddio A, Ipp M, Thivakaran S, et al. Survey of the prevalence of immunization non-compliance due to needle fears in children and adults. Vaccine. 2012;30(32):4807–4812.

- McLenon J, Rogers MA. The fear of needles: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(1):30–42.

- Goldsmith L, Woodward V, Jackson L, et al. Informed consent for blood tests in people with a learning disability. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(9):1966–1976.

- Gleason J, Ross W, Fossi A, et al. The devastating impact of covid-19 on individuals with intellectual disabilities in the United States. NEJM Catalyst. 20215;2(2):1–12.

- Baghdadli A, Picot MC, Miot S, et al. A call to action to implement effective COVID-19 prevention and screening of individuals with severe intellectual developmental and autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51(7):2566–2568.

- Bradley VJ. How COVID-19 may change the world of services to people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2020;58(5):355–360.

- Kavanagh A, Dickinson H, Carey G, et al. Improving health care for disabled people in COVID-19 and beyond: lessons from Australia and England. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(2):101050.

- Hughes N, Anderson G. The experience of the COVID-19 pandemic in a UK learning disability service: lost in a sea of ever changing variables–a perspective. Int J Dev Disabil. 2022;68(3):374–377.

- Onwumere J, Creswell C, Livingston G, et al. H. COVID-19 and UK family carers: policy implications. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(10):929–936.

- Pollock A, Campbell P, Struthers C, et al. Development of the ACTIVE framework to describe stakeholder involvement in systematic reviews. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2019;24(4):245–255.