Abstract

Background/objectives/introduction

Depression during pregnancy or postpartum carries the same risks as general depression as well as additional risks specific to pregnancy, infant health and maternal well-being. The purpose of this study is to document the prevalence of depression symptoms and diagnosis during pregnancy and in the first 3 months postpartum among a cohort of women receiving prenatal care in a large health system. Secondarily, we examine variability in screening results and diagnosis by race, ethnicity, language, economic status and other maternal characteristics during pregnancy and postpartum.

Patients/materials and methods

A retrospective study with two cohorts of patients screened for depression during pregnancy and postpartum. Out of 7807 patients with at least three prenatal care visits and a delivery in 2016, 6725 were screened for depression (87%) at least once during pregnancy or postpartum. Another 259 were excluded because of missing race data. The final sample consisted of 6523 prenatal care patients who were screened for depression; 4914 were screened for depression in pregnancy, 4619 were screened postpartum (0–3 months). There were 3010 screened during both periods who are present in both the pregnancy and postpartum cohorts. Depression screening results are from the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and diagnosis of depression was measured using ICD codes. For patients screened more than once during either time period, the highest score is used for analysis.

Results

Approximately, 11% of women had a positive depression screen as indicated by an elevated PHQ-9 score (>10) during pregnancy (11.3%) or postpartum (10.7%). Prevalence of depression diagnosis was similar in the two periods: 12.6% during pregnancy and 13.0% postpartum. A diagnosis of depression during pregnancy was most prevalent among women who were age 24 and younger (19.7%), single (20.5%), publicly insured (17.8%), multiracial (24.1%) or Native American (23.8%), and among women with a history of depression in the past year (58.9%). Among women with a positive depression screen, Black women were less than half as likely as White women to receive a diagnosis in adjusted models (AOR 0.40, CI: 0.23–0.71, p = .002). This difference was not present postpartum.

Conclusions

Depression symptoms and diagnoses differ by maternal characteristics during pregnancy with some groups at substantially higher risk. Efforts to examine disparities in screening and diagnosis are needed to identify reasons for variability in prenatal depression diagnosis between Black and White women.

Women who were young, single, have public insurance, and women who identify as multiracial or non-Hispanic (NH) Native American were most likely to have a positive depression screen or a diagnosis for depression.

After adjustment for confounders, NH Black women with a positive depression screen were about half as likely to have a diagnosis of depression during pregnancy as NH White women.

Awareness of the differing prevalence of depression risk screening results, diagnoses and potential for variation in diagnosis may identify opportunities to improve equity in the delivery of essential mental health care to all patients.

Key messages

Introduction

Depression, a leading cause of disability in the United States [Citation1], is associated with increased risk for anxiety, substance use, suicide and diabetes [Citation2]. Depression during pregnancy or postpartum carries the same risks as general depression [Citation3] as well as additional risks specific to pregnancy, infant health and maternal well-being [Citation4]. Prenatal depression (PND) may increase risks of spontaneous abortion, preterm delivery, preeclampsia, low birthweight and intrauterine growth restriction [Citation3,Citation5–9]. Postpartum depression (PPD) may negatively impact maternal–infant bonding, breastfeeding and infant development [Citation3,Citation8,Citation10–15]. Perinatal depression can also adversely affect family relationships [Citation16] and has detrimental impacts on economic and public health [Citation17]. In addition to the negative impacts of PND and PPD, perinatal mood disorders such as depression are commonly comorbid with perinatal anxiety disorders and are often recognized together as perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (PMADs) [Citation4,Citation18].

In the US, PND prevalence estimates range from 10 to 30% [Citation19] and 9.6 to 24% for PPD [Citation20,Citation21]. Studies with information on race and economic status generally report higher prevalence of depression among women who are Black and Hispanic relative to non-Hispanic (NH) White women [Citation19,Citation22–24]. One study reported prevalence of major depression disorder during pregnancy for 12.3% of NH Black patients, 9.2% of Hispanic patients, compared to 3.1% of NH White patients [Citation23]. A few studies identified higher rates of depression in women of lower economic status [Citation19,Citation25]. Nearly, all studies defined depression based on screening results rather than prospective structured diagnosing, or diagnostic results from chart reviews [Citation19–21,Citation25]. The use of screening results likely results in overestimates of prevalence [Citation26].

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends screening all women at least once prenatally or postpartum [Citation27], the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends to screening all pregnant and postpartum women [Citation28], and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends incorporating screening the mother during well-child checks [Citation29]. According to the National Academy for State Health Policy, 25 states recommend screening for maternal depression during well-child visits and six states require it as of 2020 [Citation30]. Most US prevalence studies were conducted prior to these recommendations. Given widespread electronic health record (EHR) use and increased screening, large health system data can contribute to our understanding of prevalence of depression.

Our study aims to identify the prevalence of positive depression screens and depression diagnosis in cohorts of pregnant and postpartum women receiving care in a large health system. Specific aims are to: (1) document the prevalence of positive depression screens and diagnosis of depression during pregnancy and postpartum; (2) examine variability in screening and diagnostic results by maternal characteristics and, (3) assess whether disparities in depression diagnosis persist after adjustment for confounders.

Materials and methods

This study took place at a large, non-profit healthcare system in Minnesota. This health system offers obstetric care at 10 hospitals with over 15,000 annual deliveries. Labour and delivery care is provided at these hospitals by providers employed at the health system as well as providers from external practice groups. Approximately, 50–60% of patients delivering at these hospitals also received prenatal care through the health system. Prenatal care at this health system is provided at 35 clinics by obstetrician-gynaecologists (Ob-Gyns), family physicians and certified nurse midwives. Care for high-risk pregnancies is provided by a team of maternal foetal medicine specialists. A clinical service line is responsible for standardization of care delivery, clinical quality and outcome metrics for inpatient and outpatient obstetric care and perinatology across the system.

Mental health services at this health system span the continuum of care, including outpatient psychiatry and psychotherapy, inpatient psychiatric units, partial hospital programs, and hospital and emergency department consultation–liaison services. The Mother Baby Mental Health Program was started to focus on the long-term initiatives of increasing treatment options for pregnant and postpartum women, providing education and clinical decision support to obstetric providers, and implementing standardized care processes for common psychiatric conditions like depression in outpatient OB-Gyn clinics. The Mother Baby Mental Health Program is staffed by a multidisciplinary team of psychiatrists, social workers/therapists and nurses, and offers direct patient care, an electronic consultation service for perinatal providers, and education and training to obstetric providers and nurses in order to improve the care of women with perinatal psychiatric illness.

Study data come from the EHR. Women included in the final data set: (1) delivered in 2016; (2) received at least three prenatal care visits in our system; (3) had consent on file for use of their data for research; and (4) were screened for depression either during pregnancy or the first 3 months postpartum (or both). As not all women were screened during both periods, two cohorts were created for analysis (i.e. those screened during pregnancy and those screened postpartum). Women screened during both periods were included in both cohorts. Women missing data on race were excluded. This study was approved by the Allina Health IRB under the expedited review category, which authorized a waiver of consent and HIPAA authorization, IRB number 00002425.

Outcome measures were positive depression screening results and depression diagnosis during pregnancy or postpartum. Screening data come from the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 [Citation31,Citation32] or PHQ-2 [Citation33] which are embedded in the EHR. The PHQ-2 asks about the frequency of depressed mood (feeling down, depressed or hopeless) and anhedonia (little interest or pleasure in doing things) which are symptoms required to meet the diagnostic criteria for depression. Screening is initiated by the PHQ-2, and the PHQ-9 is automatically triggered in the EHR and completed if the responses to either symptom assessed by the PHQ-2 are determined to be present.

The PHQ-9 assesses physical and mood symptoms of depression with nine items aligned with the diagnostic criteria for depression: little interest or pleasure in things, sleep problems, tired or little energy, appetite issues, restlessness, speaking or moving slowly, feeling down or hopeless, feeling bad about oneself, trouble concentrating and suicidal ideation. Responses (and scores) about symptoms in the previous 2 weeks are: not at all (0), several days (1), more than half the days (2) and every day or nearly every day (3) [Citation32]. In a study within a population of low-income prenatal patients, the PHQ-9, using a score cut off of 10 yielded 85% sensitivity and 84% specificity for major depression [Citation34]. In a large meta-analysis that compared PHQ-9 versus both semi-structured and structured interviews the cut-off score of 10 or higher maximized sensitivity and specificity with sensitivity 0.88 and specificity 0.85 relative to semi-structured interview and sensitivity of 0.70 and specificity of 0.84 relative to fully structured interviews [Citation35]. The PHQ-9 has also been identified as comparable to the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and is recommended for screening in pregnant and postpartum patients [Citation36–38].

A positive PHQ-9 screen was indicated by a scores of ≥10, aligning with recommendations for clinical assessment [Citation31]. Score totals were used to indicate risk and not individual items. However, clinicians may have guided their recommendations or next step based on responses to specific items for some women and not just the total score. As women may have been screened more than once during each period, we examined both the first and highest screening result during each time period and presented the latter in analyses.

The presence of a depression diagnosis was defined based on the presence of ICD codes for either visit diagnosis coding or entered in a patient’s problem list. ICD-10 codes included in the definition of a depression diagnosis were those for major depressive disorder (F32*, F33*) and for disorders with depressive features or mood disorders with depressive like features, dysthymic disorder and bipolar disorder with a current depressed episode (F43*, F30*, F31*, F34.1, F99*) and some codes related specifically to pregnancy (O99.34X, O90.6, F53*) (*including all subcodes). Encounter dates for ICD codes or problem list entries were used to categorize diagnosis as occurring during either pregnancy or within 3 months postpartum. ICD codes were pulled from any visit occurring during the study period and were not limited to prenatal or postpartum care visits. Thus, diagnoses may have been documented during a visit with a primary care provider, obstetrician, midwife or mental health provider.

Demographic measures included age, race, ethnicity, preferred language, marital status and economic status (measured by insurance type categorized as private or Medicaid/Medicare). Race and ethnicity are self-reported by patients in the clinic or hospital patient registration process. Patients are asked ‘how would you like us to list your race?’. Race categories included Asian, Black/African American, Native American/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, or White. Patients may list multiple races. Ethnicity is specifically measured as Hispanic/Latino/Latina. Patients are asked, ‘do you consider yourself Hispanic or Latina?’. Race and ethnicity were combined into a single categorical variable with a Hispanic/Latina category for those reporting a race of White and an ethnicity of Hispanic), each race category is NH, and patients who listed multiple races or a race other than White and a Hispanic ethnicity were coded as multiracial. In our data set, 91% of people who selected Hispanic/Latina ethnicity were classified as White for their race, while the remaining 9% were spread across each of the other race groups.

Pregnancy measures included parity, singleton or multiple gestation, provider type seen most for prenatal care (OB-Gyn, Certified Nurse Midwives, family physicians), number of prenatal care visits (3–9, 10–19 or 20+ to approximate low, average and high utilization), pregnancy risk status (high or low), outcome (live birth, miscarriage, foetal death), gestational age at delivery (preterm for <37 or full-term for 37+ weeks) and birthweight (<2500 g, 2500+ g). Patients were classified as established or new based on whether they had any encounters at our health care system in the year preceding pregnancy. A history of depression was identified based on ICD codes from the problem list or visit diagnoses in the year prior to the first prenatal care visit. Women were categorized as having a high-risk pregnancy if they experienced any of the following conditions during pregnancy: age <18, alcohol dependence/abuse not in remission, cocaine abuse, opioid abuse, HIV, diabetes (type 1, type 2, gestational), maternal bleeding or clotting disorders, multiple gestation, preeclampsia, poor foetal growth, morbidly adherent placenta or oligohydramnios.

Frequencies and Chi-square statistics were used to examine variations in prevalence of elevated PHQ-9 scores and diagnosis by maternal characteristics during pregnancy and postpartum. Logistic regression models were used to examine the association of race with a depression diagnosis after adjustment for potential confounders. Models were adjusted for covariates that could affect the likelihood of a clinical depression diagnosis during the study period: PHQ-9 score, prior diagnosis of depression, new or established patient, trimester of first screening, language. Covariates that were not statistically significant in the adjusted models were removed. Models were run for different subsets of women: all women screened during pregnancy, women with elevated PHQ-9 scores during pregnancy, and women with elevated PHQ-9 scores postpartum. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) [Citation39].

Results

During the study period, there were 7807 women with at least three prenatal care visits and permission to use records for research. We excluded 1025 women who were not screened for depression during pregnancy or 0–3 months postpartum and 259 because of missing race data. Women in the final study sample (n = 6523) were predominantly White-NH (74.8%), English speakers (94.2%), married (70.2%) and privately insured (69.4%). Forty percent of women were nulliparous (), and 32.1% had no encounters with our health system in the year prior to initiating prenatal care. Age of patients ranged from 15 to 50, with a median of 30 (IQR 26:33). The patients excluded from the sample due to lack of screening (n = 1025) were compared to those in the final sample (Appendix 1). Patients excluded because of a lack of depression screening were on average 1 year younger than those in the final sample, included a higher proportion of Black patients than the final sample (18.5% vs. 10.8%) and included a higher proportion of Native American patients (1.4% vs. 0.4%). They were also more likely to have public insurance (42.7%) than the final sample (30.6%). Additionally, patients who were excluded because of lack of screening had fewer prenatal care appointments and were less likely to return for a postpartum appointment. There was no difference between the groups with regard to high-risk pregnancy status. Similar findings on this study sample were described in a prior study on screening prevalence [Citation40].

The sample is divided into those screened prenatally (4914) and those screened postpartum (4619). There were 3010 women screened during both periods, and thus contribute data to both groups. Relative to the postpartum cohort, women in the prenatal cohort were more likely to be Black-NH (11.4% vs. 8.6%), have public insurance (31.7% vs. 27.2%), and receive prenatal care from a family physician (14.2% vs. 9.6%) ().

Depression screening and diagnosis

Among women screened for PND, 79.4% were screened once, and 20.7% were screened two or more times. Among women screened for PPD, 88.1% were screened once and 11.9% were screened two or more times. We compared patients who were screened once to those screened more than once within each study cohort. The main difference was that patients who were screened 2+ times in either time period were more likely to have screened positive (PHQ-9 score of 10+) on their initial screen during the time period (24.3% vs. 5–7% of those only screened once) (Appendix 2). Patients who were screened more than once were also more likely to be publicly insured. Asian patients were less likely to be screened more than once, while there were no other differences for other race/ethnicity groups. Additionally, nulliparous patients were more likely to be screened multiple times in the postpartum period.

Prevalence of a positive depression screen during pregnancy (11.3%) or postpartum (10.7%) were similar (). Among the subsample of unique patients screened for depression at during each period (n = 3010), 80.7% (2430) had scores <10 during both periods, 7.2% (216) screened positive only during pregnancy, 7.2% (218) screened positive only during postpartum, while 4.9% (146) screened positive during both periods.

Prevalence of depression diagnosis was also similar in the two period cohorts: 12.6% during pregnancy and 13.0% postpartum. Among the unique patients in our sample (n = 6523), 83.8% did not have a diagnosis of depression during either period, 5.9% (387) had a diagnosis of depression in the prenatal period, 5.8% (381) had a diagnosis of depression during the postpartum period only, and 4.4% (290) had a diagnosis during both periods.

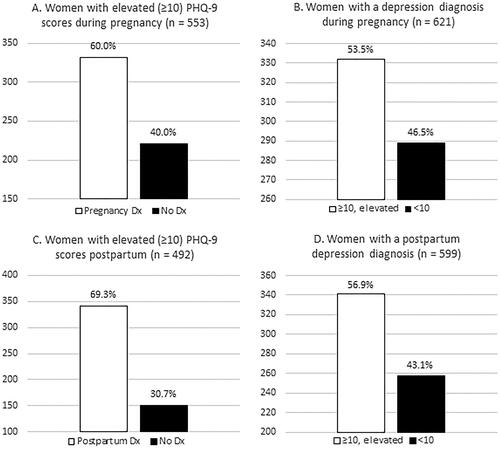

Of women with a depression diagnosis during pregnancy (n = 621), 53% had a positive depression screen during pregnancy, while the remaining 47% had a negative screen (). Of those with a positive depression screen during pregnancy (n = 553), 60% had a diagnosis of depression during pregnancy (data not shown). Among women with a diagnosis during the postpartum period (n = 599), 57% had a positive depression screen postpartum. Among those with a positive screen postpartum (n = 492), 69% were diagnosed, which is slightly higher than the prenatal figure.

Variation by demographic measures

Women who were age 24 and younger were most likely to have a positive depression screen (21% pregnancy, 18.7% postpartum) and had the highest prevalence of depression diagnosis (19.7% pregnancy, 21.9% postpartum) relative to older women (). Multiracial women (∼70% listed Black and White) were most likely to have a positive depression screen during pregnancy or postpartum (31% and 25.5%) and had the highest prevalence of depression diagnosis during both periods (24.1% and 21.6%) compared to other racial/ethnic groups. During pregnancy, Native American-NH women had the second highest prevalence of a depression diagnosis (23.8%). Among Black-NH women, 15% had a positive depression screen during pregnancy and 13.8% had a positive depression screen postpartum. Black-NH women were less likely to be diagnosed with depression during pregnancy (10.5%) than White-NH women (14.1%). However, Black-NH (13.1%) and White-NH (13.7%) women had similar rates of PPD diagnosis.

Prevalence of positive depression screens or a depression diagnosis during pregnancy and postpartum were substantially higher among women with a preferred language of English, single women, and women with low economic status. Women with a high-risk pregnancy were more likely to have a diagnosis in both pregnancy and postpartum compared to women with low-risk pregnancies. Established patients were also more likely to have a positive depression screen or a diagnosis compared to new patients both prenatally and postpartum. Women with a history of depression were more likely to have a positive depression screen or diagnosis during either period.

Examination of disparities

To explore potential disparities in PND diagnosis, we conducted logistic regression models with adjustment for several covariates that may be associated with likelihood of diagnosis (e.g. history of depression, PHQ-9 score value, new vs. established patient, trimester of first PHQ-9, provider type) as well as other factors that might be predictive of depression prevalence (age, economic status, marital status, parity). For these models, we narrowed the prenatal sample to women who identified as Black-NH or White-NH due to insufficient sample sizes within other racial groups (n = 4177). In the final model, Black-NH women were half as likely as White-NH women to have a diagnosis during pregnancy after adjustment for remaining confounders (OR of 0.52, 95% CI (0.35, 0.79)) (). We also examined this association for the subset of the prenatal cohort with a positive depression screen (n = 478). In this subset, the adjusted OR was 0.40, p = .02 indicating Black-NH women with a positive depression screen during pregnancy were less than half as likely to have a diagnosis of depression during pregnancy (). The limited change in the OR after adjustment indicates little confounding present by the clinical variables available. Given that Black women were less likely to have a history with the health system, we created an outcome measure of diagnosis of depression at any point during pregnancy or postpartum to conduct a post hoc examination of whether there was a delay in diagnosis of depression for Black-NH women. These models were run among all prenatally screened Black-NH and White-NH women who had a positive depression screen during pregnancy (n = 478). These models did not differ substantially from the prior models examining prenatal diagnosis, with an OR of 0.39, p = .001.

Models run for Black-NH and White-NH women who had a positive depression screen during postpartum (n = 324), did not identify a disparity in diagnosis in either the unadjusted or adjusted models ().

Discussion and conclusions

The aim of this study was to identify prevalence of positive depression screening and diagnosis during pregnancy and postpartum as well as to examine variability by maternal characteristics such as race and ethnicity. The prevalence of depression diagnosis found in our study (13%) is within the range of some other US studies. A systematic review of racial disparities in PND estimated a prevalence range of 10–30% in the United States [Citation19]. Reasons for this wide range of prevalence could include variability in measure for defining depression (i.e. screening tool, diagnostic interview, ICD codes), timing of measurement, variability of risk level and characteristics in the population. Prior studies have based prevalence estimates on screening tools which may account for some of the variance [Citation19]. In fact, a meta-analysis with data from 9242 participants found estimating prevalence using a cut point of ≥10 on the PHQ-9 yielded a nearly twofold overestimate relative to depression estimates from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID) [Citation26]. Given this finding, it is somewhat surprising that our study found the proportions with positive depression screens (elevated PHQ-9 scores) and with diagnosed depression to be very similar (although not reflecting the exact same women). Our measure of diagnosis in the context of medical record coding may reflect a different measure of depression relative to what would be yielded from the SCID; for example, with diagnoses for women receiving treatment but not having a current episode.

This study identified disparities with younger women, single women, women with public insurance, and women who identify as multiracial or Native American-NH being more likely than White women to have a positive depression screen or a diagnosis for depression. Some of these findings are echoed in national data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, which found higher depression among younger women, Black women and Native American women [Citation20]. Our study also found Black-NH women were half as likely to be diagnosed with depression during pregnancy (but not postpartum) after having a high PHQ-9 screen as compared to White women. Potential under-diagnosis for Black women was identified in two other studies [Citation41,Citation42]. It is important to note that we cannot definitively conclude that Black women were underdiagnosed because we lack clinical assessment data determining if they met diagnostic criteria beyond the PHQ-9. Additionally, as this disparity was not present at postpartum, there may be explanations other than racial bias in the diagnosis process.

Implications of these findings for health systems and providers include improved efforts for depression screening during both pregnancy and postpartum. In addition to the women excluded from the study because they were not screened in either period, many women in our sample were screened only during pregnancy or postpartum. Current guidelines recommend screening all pregnant and postpartum patients [Citation28,Citation43–45]. Awareness of the differing prevalence of depression risk screening results, diagnoses and potential for variation in diagnosis may identify opportunities to improve equity in the delivery of essential mental health care to all patients. Opportunities to improve equity in care delivery may include a range of options. These include education to clinic staff on disparities in risk for, diagnosis, and treatment of mental health conditions, training that addresses implicit bias, modifications to clinical resources to sufficiently address mental health concerns identified such that staff feel more support for the next steps after screening, and clinical policies around screening, visit times and workflows. In a prior study examining screening among the same study sample, clinic site was found to be the strongest predictor of screening pointing to the impact of clinic level policies and workflows [Citation40]. Additionally, supporting efforts to improve interconceptional care may increase access to primary and mental health care prior to pregnancy to identify depression prior to pregnancy. Recent analyses indicate a potential increase in depression among postpartum patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, providing further evidence of need to systematically identify and address PMADs [Citation46]. Lastly, researchers have recommended lowering the cut-point for depression screening for Black, low-income women to improve sensitivity [Citation47]. However, this study was done on a small sample size (n = 95) and did not include the PHQ-9, thus further research is needed before implementing modifications to clinical guidelines.

Strengths, limitations and future directions

The findings of this study should be interpreted in the context of several strengths and limitations. One strength is the large population and sample size representative of women receiving care at a large health system. A related major limitation to our ability to assess prevalence is that this study excludes women who were not screened for depression in either of these periods. As demonstrated in Appendix 1, there are differences between patients excluded due to a lack of screening versus those who were screened with higher representation of Black patients, low-income patients and patients with fewer visits in the unscreened group. A previous examination from the same health system and study sample found few differences between women screened and not screened in the prenatal period; however, significant differences with regard to which women return for postpartum care and which women get screened for PPD [Citation40]. This study also found clinic was the biggest predictor of screening. Given that women in groups at high risk for depression were less likely to return for postpartum care or get screened, the postpartum prevalence reported here is likely an underestimate. Additionally, while our study sample describes screening and diagnosis results for all racial groups, we were unable to conduct multivariate analyses for several racial groups due to limited sample size.

While the guidelines for screening and diagnosis indicate women with an elevated PHQ-9 score should have a clinical assessment for depression, the data presented here reflect clinical practice and the clinic- and provider-level variability that may occur within the process of determining a diagnosis in the context of clinical care. Given this clinical setting, our findings may not be comparable to research studies that include both a screening and a systematically structured diagnostic interview. The lack of a systematic diagnostic interview for all patients such as the SCID is a limitation to identification of prevalence of depression based on a standardized measure. Our measure of prevalence is reflective of diagnoses made by providers in the course of clinical care. This is also noted in where some patients with a diagnosis did not screen positive and may be a reflection of patients under care for depression but not experiencing symptoms severe enough to screen positive.

This study was also limited to data available in the EHRs with low proportions of missing data. Thus, some characteristics that have been identified as associated with depression prevalence could not be examined (i.e. education) given the lack of availability of these fields in the EHR. It should also be noted that the postpartum period reflected in our data is 0–3 months only and does not capture new onset occurring after that period.

Author contributions

ACS and EL conceived and designed the study, obtained funding, and led the work on the manuscript development. MV conducted all data analysis and contributed to the final edits in the manuscript. AN contributed to the analytical planning and advising on statistical analysis, interpretation and contributed to manuscript content. AKS contributed to literature review and drafting sections of the manuscript, including interpretation of data. All authors contributed to drafting the manuscript, critically revising the manuscript for intellectual content, and approving the published version.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Jessica Taghon for her assistance with literature review during the development of this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, ACS.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Murray CJ, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, et al. The State of US Health, 1990–2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310(6):1–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.13805.

- McQuaid JR, Lin EH, Barber JP, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of depression across three age cohorts. Washington (DC): American Psychological Association; 2019.

- Lusskin SI, Pundiak TM, Habib SM. Perinatal depression: hiding in plain sight. Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52(8):479–488. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200802.

- Meltzer-Brody S, Rubinow D. An overview of perinatal mood and anxiety disorders: epidemiology and etiology. Women’s mood disorders: a clinician’s guide to perinatal psychiatry. E. Cox. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 5–16.

- Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A, et al. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(4):698–709. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000116689.75396.5f.

- Bonari L, Bennett H, Einarson A, et al. Risks of untreated depression during pregnancy. Can Fam Physician. 2004;50:37–39.

- Davalos DB, Yadon CA, Tregellas HC. Untreated prenatal maternal depression and the potential risks to offspring: a review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(1):1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00737-011-0251-1.

- Grigoriadis S, VonderPorten EH, Mamisashvili L, et al. The impact of maternal depression during pregnancy on perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(4):e321–e341. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12r07968.

- Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, et al. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(10):1012–1024. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.111.

- Goodman JH. Perinatal depression and infant mental health. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2019;33(3):217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2019.01.010.

- Kingston D, Tough S, Whitfield H. Prenatal and postpartum maternal psychological distress and infant development: a systematic review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2012;43(5):683–714. doi: 10.1007/s10578-012-0291-4.

- Liu Y, Kaaya S, Chai J, et al. Maternal depressive symptoms and early childhood cognitive development: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2017;47(4):680–689. doi: 10.1017/S003329171600283X.

- Rogers A, Obst S, Teague SJ, et al. Association between maternal perinatal depression and anxiety and child and adolescent development: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(11):1082–1092. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2910.

- Slomian J, Honvo G, Emonts P, et al. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: a systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Womens Health. 2019;15:1745506519844044.

- Szegda K, Markenson G, Bertone-Johnson ER, et al. Depression during pregnancy: a risk factor for adverse neonatal outcomes? A critical review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27(9):960–967. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.845157.

- Woody CA, Ferrari AJ, Siskind DJ, et al. A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.003.

- Luca DL, Margiotta C, Staatz C, et al. Financial toll of untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders among 2017 births in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(6):888–896. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305619.

- Accortt EE, Wong MS. It is time for routine screening for perinatal mood and anxiety disorders in obstetrics and gynecology settings. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2017;72(9):553–568. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0000000000000477.

- Mukherjee S, Trepka MJ, Pierre-Victor D, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in antenatal depression in the United States: a systematic review. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(9):1780–1797. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-1989-x.

- Bauman BL, Ko JY, Cox S, et al. Vital signs: postpartum depressive symptoms and provider discussions about perinatal depression – United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(19):575–581. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6919a2.

- Wilcox M, McGee BA, Ionescu DF, et al. Perinatal depressive symptoms often start in the prenatal rather than postpartum period: results from a longitudinal study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2021;24(1):119–131. doi: 10.1007/s00737-020-01017-z.

- Cannon C, Nasrallah HA. A focus on postpartum depression among African American women: a literature review. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2019;31(2):138–143.

- Melville JL, Gavin A, Guo Y, et al. Depressive disorders during pregnancy: prevalence and risk factors in a large urban sample. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(5):1064–1070. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f60b0a.

- Orr ST, Blazer DG, James SA. Racial disparities in elevated prenatal depressive symptoms among black and white women in Eastern North Carolina. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(6):463–468. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.08.004.

- Goyal D, Gay C, Lee KA. How much does low socioeconomic status increase the risk of prenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms in first-time mothers? Womens Health Issues. 2010;20(2):96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2009.11.003.

- Levis B, Benedetti A, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores do not accurately estimate depression prevalence: individual participant data meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;122:115–128.e111. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.02.002.

- ACOG. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Opinion No. 630. Screening for perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1268–1271.

- Siu AL, Force USPST, Bibbins-Domingo K, et al. Screening for depression in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;315(4):380–387. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18392.

- Earls MF. Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal and postpartum depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):1032–1039. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2348.

- National Academy for State Health Policy. NASHP finds more states are screening for maternal depression during well-child visits; [cited 2023 May 26]. Available from: https://nashp.org/nashp-finds-more-states-are-screening-for-maternal-depression-during-well-child-visits/

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C.

- Sidebottom AC, Harrison PA, Godecker A, et al. Validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) for prenatal depression screening. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(5):367–374. doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0295-x.

- Levis B, Benedetti A, Thombs BD, et al. Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;365:l1476. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1476.

- ACOG. Screening and diagnosis of mental health conditions during pregnancy and postpartum. Clinical Practice Guideline, Number 4. Washington (DC): American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2023.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Depression screening fact sheet and resources; 2016 [cited 2023 May 26]. Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr/tools/healthier-pregnancy/fact-sheets/depression.html#practices

- Yawn BP, Pace W, Wollan PC, et al. Concordance of Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to assess increased risk of depression among postpartum women. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(5):483–491. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.05.080155.

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station (TX): StataCorp LLC; 2017.

- Sidebottom A, Vacquier M, LaRusso E, et al. Perinatal depression screening practices in a large health system: identifying current state and assessing opportunities to provide more equitable care. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2021;24(1):133–144. doi: 10.1007/s00737-020-01035-x.

- Chan AL, Guo N, Popat R, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in hospital-based care associated with postpartum depression. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8(1):220–229. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00774-y.

- Kozhimannil KB, Trinacty CM, Busch AB, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in postpartum depression care among low-income women. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(6):619–625. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.6.pss6206_0619.

- ACOG. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 757: screening for perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(5):e208–e212.

- ACOG. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 766: approaches to limit intervention during labor and birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(2):e164–e173.

- Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care. Patient safety bundles - maternal mental health: depression and anxiety; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 23]. Available from: https://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/patient-safety-bundles/maternal-mental-health-depression-and-anxiety/.

- Chen Q, Li W, Xiong J, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with postpartum depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: a literature review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(4):2219.

- Tandon SD, Cluxton-Keller F, Leis J, et al. A comparison of three screening tools to identify perinatal depression among low-income African American women. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(1–2):155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.07.014.

Appendix 1.

Comparison of those excluded due to lack of prenatal or postpartum depression screening compared to those included in the final sample

Appendix 2.

Comparison of patients screened for depression once to those screened 2 or more times during each time period

Figure 1. Diagnosis among patients with a positive screen and screening results among patients with a diagnosis.

Table 1. Characteristics of study sample (N = 6523).

Table 2. Prevalence of elevated PHQ-9 scores and depression diagnoses among prenatal and postpartum patients (n = 6523).

Table 3. Logistic regression models predicting depression diagnosis among Black women compared to White women in pregnancy and postpartum.