ABSTRACT

This article analyses the media reporting on conflicts and cooperation in the Brahmaputra River basin. We used 2437 newspaper articles published between 2010 and 2020 from the four riparians (China, India, Bhutan and Bangladesh) to explain the science–media interlinkages and what print media reports on conflicts and cooperation. We have found that most articles focus on conflicts, especially relating to hydropower development, data and information asymmetry, and disaster governance. There is limited media reporting on the avenues of cooperation such as informal water diplomacy, collaborative research opportunities, and the community and the culture that brings the riparians together.

Introduction

Two issues that hamper constructive engagement between the riparians in the Brahmaputra basin are annual floods and water infrastructure development. The floods have been an annual phenomenon owing to the region’s geography, and with changing climate the floods have become more devastating (Wijngaard et al., Citation2017). Water infrastructure in the basin has taken priority among the upper riparian countries (India and China) to establish user rights on the river. Contestation is fuelled by the historical border issues and unilateral decision-making on the water infrastructure by China and India to claim their authority in the basin (Vij et al., Citation2020).

The media has been reporting on the above issues in the Brahmaputra River basin, and therefore it is significant in shaping the narratives of conflicts and cooperation, eventually influencing the public agenda. Further, as a primary forum for the production and transformation of public debates, the media influence understanding of risks and responsibilities (Carvalho, Citation2010). For instance, the media’s portrayal of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam project, highlighting the aspects of national image and mutual benefits, strongly influenced the perception of the Ethiopian people in seeing the Nile River as contributing to prosperity and development (Belay, Citation2014). Similarly, the Rhine basin pollution case received a lot of media attention, accelerating the negotiations during the ministerial conferences between the Dutch and the French, but also convinced Dutch citizens that the issue was taken seriously (Dieperink, Citation2011). The public relies heavily on the media as it demands accountability, forcing negotiators to justify themselves to their constituencies about controversial environmental challenges (Linnerooth, Citation1990).

Despite the role of media in shaping narratives in transboundary waters, their role in both formal and informal water diplomacy initiatives has been limited (Scheufele, Citation1999; Wei et al., Citation2021). With the fear of being misrepresented, academics, development organizations and state actors tend to avoid involving the media directly during multilateral and multi-stakeholder dialogues. For instance, in the Brahmaputra basin, the media has been able to infuse the narrative of conflict among the upstream hegemons (India and China), even when there was a lack of clarity if either party was responsible. The recent turbidity in the water of Siang (a tributary of the Brahmaputra) made it into the national media and held China responsible in India, while there was no clear scientific evidence as to what caused the event (Singh, Citation2017); however, it was later attributed to an earthquake in Tibet (Krishnan, Citation2017). Relations between riparian countries become more complicated when myths and false notions are used to explain the pertinent issues of flooding and hydropower construction. With inadequate basin-wide research and weak science–media interlinkages, this can potentially lead to concentration on sensational reporting that can lead to conflict-like situations (Barua et al., Citation2019; Jiang et al., Citation2017). For instance, during the floods in the Brahmaputra basin, the Indian media attains the role of communicating and amplifying the narrative of China’s dam-building, insinuating blame, catalysing national security and framing negative public discourse on China (EurAsian Times Desk, Citation2020). Such media trials escalate the mistrust between the riparian states. Although it is unclear whether or not it can constrain government decisions to escalate to war during a transboundary dispute, the media plays a significant role in policymaking (Crow & Lawlor, Citation2016).

However, for transboundary river basins, a shift of gear from formal to informal multitrack diplomacy is gaining track, as it allows plurality in opinions (Barua, Citation2018) and the media has a very important role in such processes. The advances in diversifying within water diplomacy contribute to critical hydropolitics, allowing for the redistribution of power between actors for transboundary spaces to be reconfigured and reinterpreted (Mirumachi, Citation2020). Informal water dialogues where non-state actors in the presence of formal actors discuss the issues related to transboundary rivers. Such diplomacy processes are complementary to the formal processes (state to state) and tend to be most impactful in creating safe spaces (Klimes et al., Citation2019).

Currently, a systematic understanding of the role of the media in shaping the narrative around the Brahmaputra River basin is missing. Understanding the role of the media in framing transboundary can shed light on the broader role of the media in influencing water policymaking in South Asian countries and the extent to which governments use media to convey compelling and deterrent messages to other riparians. Therefore, this article answers the questions: What are the different issues in the Brahmaputra basin reported by the newspapers between 2010 and 2020? Why does the media frame these issues within the conflict–cooperation continuum? To answer these questions, we conducted an extensive review of newspaper articles from four riparian countries. Articles were collected from regional and national newspapers to understand the issues and their underlying framings. The analysis presents the underlying frames of conflicts and cooperation from the themes of flooding and disaster, river infrastructure, and data-sharing. Further, the article reflects upon the institutions discussed in the media reports and their conflicts across the riparian nations.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. The second section (methodology) discusses the protocol followed for data collection (media reports), data analysis and limitations in our methodological approach. The third section (findings) presents the key findings emerging from the descriptive statistical analysis and framing of themes. The fourth section (discussion) reflects on the key findings of the science–media interlinkages and is followed by concluding remarks.

Methodology

Methodological approach

The study uses an interpretive research design, as it builds on the argument that meaning-making needs to be the key element of any scientific research. Interpretivism emphasizes that any investigation in the social world cannot be pursued with a detached objective truth (Leitch et al., Citation2010). Therefore, this study highlights ‘contextuality’ instead of ‘generalizability’ backed by the positivist school of thought. We emphasize meaning-making as it helps human beings to make sense of their surroundings constituting the reality (Schwartz-Shea & Yanow, Citation2013). As such, the role of the media in shaping the narrative around the Brahmaputra River basin is assessed from the perspective of each of the four riparian countries to assert that our knowledge of reality is indeed an interpretation by policy actors (Burell & Morgan, Citation1979).

A thorough media-framing analysis of archived newspaper articles is carried out. Only privately owned newspapers (print media reports) were selected since they offer a more straightforward means of methodically collecting and analysing data regarding the geographical and temporal reach of the study (Doulton & Brown, Citation2009). Moreover, mainstream newspaper media tend to present and legitimize the official discourses on environmental issues and international relations, including transboundary waters. Entman (Citation1993, p. 52) introduced the most cited definition of media framing:

Framing essentially involves selection and salience. To frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described.

Thus, frames help identify both problems and solutions (Nisbet, Citation2009).

Data collection

A systematic literature review methodology inspires our data collection and analysis of the study, emphasizing both descriptive statistics and content analysis. A systematic, transparent and reproducible media-framing analysis will help explain the current media reporting patterns and identify critical gaps in science–media interlinkages. Systematic reviews are appreciated for dealing with large datasets in a consolidated and comprehensive manner (van der Heijden, Citation2021). A protocol was prepared to implement the systematic data collection of newspaper articles (see the supplemental data online). We used the criteria such as the percentage of readership, circulation, reputation as well as the quality of journalism to select the 10 newspapers: India (n = 4), Bangladesh (n = 3), China (n = 2) and Bhutan (n = 1).

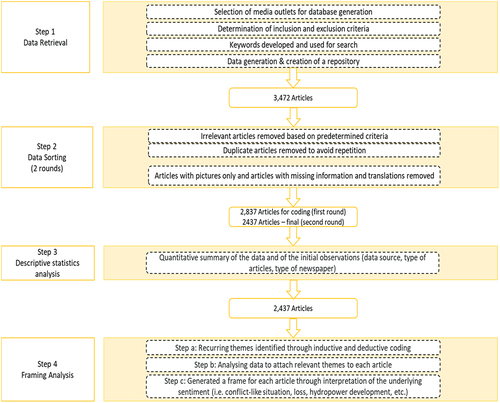

We endeavoured to sample at least two newspapers per country to have a robust dataset representing different political and cultural positions (Carvalho, Citation2007); however, in the case of Bhutan, only one publication is considered because this small nation for a very long time had only one national daily. The 10 newspapers () were further triangulated with consultation with environmental journalists and key media personnel (such as the Third Pole). The availability of archived data was also an essential point of consideration. The English dailies from every nation have contributed to a significant number of articles, whilst the local language newspaper from India has contributed to the maximum number of articles, highlighting that the river is critical to India within the region. High coverage from the Indian local newspapers (Assamese) is due to the importance of the river to local communities. The protocol guides the research for data collection by using the following steps ().

Table 1. Data collection from newspapers in riparian countries.

With the help of predetermined keywords and search strings, we retrieved archival data spanning the four riparian countries between 2010 and 2020. In the past, most local newspapers in the region only had print versions, and with the pandemic it was challenging to collect data from the agencies and libraries. The period is selected to ensure that sufficient online data are available for the newspapers. Within each newspaper we used search terms such as Yarlung Zangbo/Brahmaputra/Jamuna (even if the river is not the core component of the article), ‘the name of the country (China, India, Bhutan, and Bangladesh)’, ‘infrastructures’ (‘hydroelectric’, ‘dam(s)’, ‘bridge’, ‘railways’), ‘disasters’ (‘flood’, ‘erosion’, ‘sedimentation’), ‘national interest’ (‘data sharing’, ‘bilateral ties’, ‘meetings’, ‘border protection’) to identify articles. All articles are initially screened based on the titles, followed by the full-text reading of the articles. A total of 2437 articles are then retrieved, and ready for analysis (for more details, see the research protocol).

Data analysis

The study uses both deductive and inductive coding to seek an explanation within the frame of reference of the participants and not just an objective third-party observation (Ponelis, Citation2015). To ensure cross-country comparability, descriptive statistics based on deductive coding is conducted. Aspects such as the total number of articles, types of articles that appeared per year in each newspaper, the topics of relevance discussed in each country, and the type of the media outlet were analysed using deductive coding. Further, deductive coding helped understand the types of sources (local, provincial and national) to determine how the issue weighs at different political levels, as depicted by the extent of its coverage. Aspects such as gender of the reporter, gender of the respondent and their institutional affiliation, and the type of the article have also been developed in the extraction table (see the supplemental data online) for a thorough understanding of who has a dominant representation, which voices are heard and whose issues are put forward.

For identifying themes, we used both deductive and inductive coding. Considering the extensive dataset, we started by deductively identifying themes that have been used in previous media studies focused on infrastructure, disaster, livelihood, data-sharing and biodiversity loss (Jiang et al., Citation2017; Wei et al., Citation2021). As the research progressed, new themes such as ‘scientific research’ and ‘sovereignty’ emerged inductively, selected after carefully reading through several news articles. For example, an article published in The Hindu reported a scientific study conducted by a group of Dutch researchers, stating that the melting glaciers in the Himalayas owing to climate change are likely to have an impact on the Brahmaputra basin, challenging water availability and food security (The Hindu, Citation2010). This article, including others, reinforced the importance of ‘scientific research’ as an important thematic area.

Another article published in Dainik Assam stated that in the interest of claiming rights over the Brahmaputra basin internationally, the Indian government decided to form a high-level panel (Dainik Assam, Citation2010b). This is inevitably an example of the exercise of state sovereignty which permits the use of natural resources within the state. Similarly, other articles discussed the tendency of the riparian countries to claim the river through building dams, diversion of river waters and territorial sovereignty. Hence, to reflect the shared focus of these articles, ‘sovereignty’ is considered an important thematic area. For each newspaper article we followed an iterative process of analysis. Each article frame was filled by an individual author of this paper (Arundhati Deka and Natasha Hazarika) and then randomly checked by the remaining authors. Three out of five authors read the articles for inter-coding reliability.

Limitations

A country-wise bias was noted within this research during data collection. In China, local language newspapers are probably more popular among the masses, but it was challenging to include them due to language and translation constraints. The English dailies from China mainly cater to a global audience; hence, the articles might be biased to avoid scrutiny from the Chinese government. For Bangladesh, newspapers were selected based on the online availability of archival data. Due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, it was not possible to travel across cities to gather data from public libraries. For instance, until recently, Bhutan had only one national (English) newspaper, but all the data were not available online. Due to frequent lockdowns and the inability to travel, data for Bhutan were collected for only five years (2015 onwards).

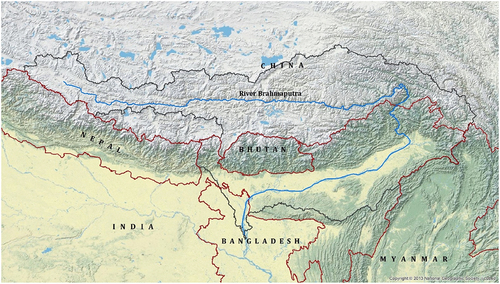

Biophysical and political context

The Brahmaputra River basin (), with a total length of 2880 km and a drainage area of approximately 573,394 km2, originates in the Himalayan Mountain range in Tibet. It flows through China where it is known as Yarlung Tsangpo (1700 km), India where it is called the Brahmaputra and Siang (918 km), and Bangladesh as the Jamuna (337 km). Three main tributaries originate in Bhutan, thus making the country one of the major contributors to the river (Frenken, Citation2012). The river basin is not alien to disasters such as floods and erosion, occurring annually, especially during the monsoon season. Moreover, the riverine communities living in the basin are dependent on the Brahmaputra for their livelihood (agriculture, fishing), and have a centuries-long relationship with the river (spiritually and culturally).

The riparian countries are in the nascent stages of development and still overcoming poverty and other issues; three out of the four nations sharing the basin, China, India and Bangladesh, have already been declared as the first, second and eighth most-populous countries globally. Consequently, they are all confronted with water scarcity and steeply rising demands for food and energy (Grafton et al., Citation2014). Due to political changes post-decolonization there is friction between the countries, marred by territorial conflicts (Salman & Uprety, Citation2021; Swain, Citation1998). Moreover, the riparian countries have had to deal with both intra- and inter-state conflicts over the sharing of the Brahmaputra in both down- and upstream areas (Uprety & Salman, Citation2011).

The four riparian countries have varied national interests and priorities in the Brahmaputra River basin. For instance, China aims to tap the hydropower potential of the river and has put into operation its first mega-hydroelectric power station on the mainstream of the Yarlung–Tsangpo River in 2015, followed by approval for smaller dams in the river (Krishnan, Citation2021). India is also invested in harnessing the river for hydroelectric power generation with the operationalization of various hydroelectric projects across the river, intending not to lose its water rights. Bhutan, on the other hand, has a longstanding symbiotic relationship with India through cooperation in the construction of hydropower projects, which has benefited the country economically by generating revenues. Although media reports have noted that flash floods have been a concern for Assam, stone-mining upstream and heavy siltation have caused degradation of agricultural land (Bisht, Citation2019; Frontier Weekly, Citation2018). The case of flash floods suggests that water-induced disasters can be a pertinent issue across the Indo-Bhutan border. ‘The discourses that these tensions have generated at the local scale and the ramifications they hold for the bilateral hydel cooperation is reflective of the glaring gap that exists between the capitals and the borderlands of South Asia’ (Bisht, Citation2019, p. 1128). As for Bangladesh, being the most downstream country, its primary domestic priority is to support agriculture and allied sectors. Bangladesh also wants to control the physical aspects of the river as it often hinders the well-being of its people either through flood or drought, thus resulting in severe socio-economic losses, as is the case with the lower reaches of Assam (Vij et al., Citation2020).

Apart from varying interests of the riparian countries, the Brahmaputra River basin is plagued with historical and contemporary geopolitical disputes, for example, the India–China war in 1962, which happened due to territorial conflict, followed by various border scuffles (2013, 2017 and 2020) in the eastern and western sectors. As a politically sensitive river basin, it has led to the ‘securitization’ of water and inaccessibility of even basic information about the river, such as the discharge and sediment grain size data, water withdrawal, and usage (Barua, Citation2018; Surie & Prasai, Citation2015). Such securitization has created an atmosphere of mistrust, hostility and suspicion between the riparian countries, hindering cooperative water-sharing initiatives at the basin level. Due to the asymmetry of power, there is difficulty in accessing reliable water source data due to the absence of a transparent water-sharing mechanism (Barua et al., Citation2018).

The emergence of China as a hegemon in the basin in recent years has also disgruntled India at the perceived threat to their traditional role (Yasuda et al., Citation2018). Further, China’s security agenda has been limited to the consideration of national water availability, leading to military security concerns (Xie & Warner, Citation2022). The country is in need of water resources to meet the rising national demand and has been taking unilateral actions, through the construction of infrastructures such as dams or water diversion projects (Chowdhury, Citation2010; Sood & Mathukumalli, Citation2011; Xie et al., Citation2018). For the past decade, India and China have stirred discussions on potential conflict due to water resource competition (Samaranayake et al., Citation2016).

Conflicts also often arise between India and Bangladesh regarding the strategies being adopted for controlling floods and harnessing the potential of the Brahmaputra. Longstanding subnational civil society activism in India over the social and environmental impacts of large-scale hydropower projects, and bilateral disputes between India and Bangladesh over the terms of water-sharing are other issues of conflict (Barua & Vij, Citation2018; Yasuda et al., Citation2018). ‘Issues of disaster and governance have been part of different debates within the epistemic boundaries’ (Varma & Mishra, Citation2017, p. 207). Floods have been common in the region and the immediate strategy for flood control led to an infrastructure-based political economy associated with embankment construction (Boyce, Citation1990; Varma & Mishra, Citation2017) and breaches every flood season. The economic reforms of the 1990s in India deliberated and proposed turning the region into a powerhouse for meeting the energy demands of the country through the construction of hydropower projects (Baruah, Citation2012; Varma & Mishra, Citation2017).

Considering that the benefits of the river are seen through a very localized and sectoral lens, there is a contested approach towards the river which most times puts the riparian countries at odds with one another. The river also becomes a casualty during territorial and other geopolitical disputes as the upstream nations can use their position of influence to disrupt the flow downstream. The absence of a basin-level institution and lack of collaborative research efforts only furthers the cause of developing a holistic understanding of the basin and developing trust that could lead to benefit-sharing of water resources, minimizing exploitation.

The Brahmaputra has been comparatively under-examined, especially with respect to hydropolitics, considering the complex geopolitics and potential threats to regional stability. Water politics relate to the ability of political institutions to manage shared water resources in a politically conducive environment, that is, devoid of tensions or conflict between political entities (Rai et al., Citation2017). ‘The transboundary hydropolitics in the region are seemingly static as the majority of conflict–cooperation trends over the last century have remained majorly unchanged’ (Williams, Citation2018, p. 2). Except for limited data exchange between countries, there have been several discussions among the policy actors (people-to-people diplomacy among academics and civil society organizations (CSOs)) for multilateral cooperation, but never quite materialized into action at the track 1 level (i.e., government to government). There is a lack of willingness among political leaders, especially from the upstream countries. Even the National Water Policy, 2012 of India only emphasizes encouraging bilateral relations, as opposed to multilateral, with its neighbouring countries (MoWR, Citation2012). Apart from the unwillingness of the policymakers and minimal engagements of academics and CSOs, the media as a stakeholder has mostly focused on reporting contested river development initiatives such as hydropower and river diversion, which can potentially lead to reduced flow downstream, causing passive, if not active, dispute. The stakeholders should rather leverage the media for changing the narrative in shared waters for improved decision-making processes. For example, the media raised awareness of the transboundary nature of the environmental issues in the Sundarbans, leading to a memorandum of understanding between Bangladesh and India (IUCN, Citation2018).

Findings

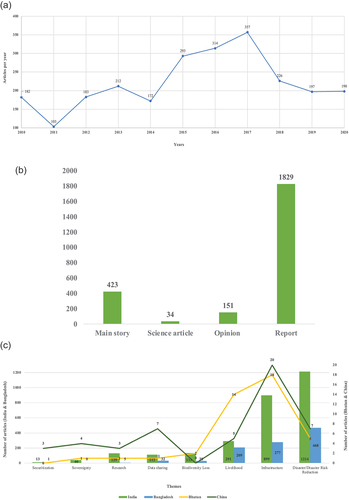

The frequency of articles published between 2010 and 2020 suggests that the Brahmaputra River was in the news, especially between 2015 and 2017 (). It was mainly due to the change in the Indian regime from the National Democratic Alliance (coalition of right-wing political parties) government replacing the United Progressive Alliance (coalition of predominantly centre-left political parties) government. The rise of India’s nationalistic and populistic government might have resulted in initial dialogues with the other riparian countries. However, the decline in the frequency between 2018 and 2020 indicates an unwillingness to negotiate past failed negotiations. Alternatively, in the following years, it has also been noticed that the issues concerning the river did not find media attention as border disputes between India and China seem to have taken over national headlines. There was a Doklam standoff between India and China when the hydrological data-sharing between the nations was compromised. However, 2017 witnessed a major annual flooding event in India (Assam) and Bangladesh, and there was an increase in media reporting.

Figure 3. (a). Frequency of articles; (b) types of articles captured; and (c) thematic distribution of newspaper articles.

The types of newspaper articles ranged from main story (n = 422), opinion pieces (n = 158), science articles (n = 34) and reports (n = 1823). The number of science articles was meagre, implicit in the lack of evidence-based reporting for the basin (). The main stories also seem to be comparatively lower than the reports, even though the river is extremely significant for the Tibet Autonomous Region in China, north-east India and Bangladesh.

Apart from the type of articles, the source of information and data were also heavily inclined towards the government and allied category, followed by academia. This indicates that there is limited space for other groups (such as CSOs) to share their concerns and how the narrative might be majorly dominated by government and allied departments, along with supporting technocrats. The sources reported in the newspaper articles were male dominated (n = 1068), indicative of the bias present in the representation of voices. Even among the reporters, when the source is available, the male (n = 392) reporters outweigh the female (n = 43) reporters across the riparian countries.

Lastly, the analysis suggests that disaster/disaster risk reduction was the key theme reported, followed by infrastructure and livelihood (), making a case that coordinated efforts are necessary to mitigate disasters in the river basin. The nuances relating to ) will be discussed in the following subsection, elaborating on the newspaper stories relating to each theme captured. For instance, the subsection on floods and disasters expands on the local-level corruption and dissatisfaction of the communities with government efforts at disaster risk reduction.

Flood disasters, related impacts and responses

Our analysis shows that the Bangladesh media covers how millions are affected every year, several losing their lives, erosion of thousands of hectares of agricultural land, breakage of schools and healthcare facilities, thereby challenging the overall socio-economic well-being of the region (Bangladesh Pratidin, Citation2015; Prothom Alo, Citation2020). India’s national newspaper reports suggest that the region is being devoured by flood and erosion every year, as in the autumn of August 1970 (The Hindu, Citation2020a) or in the summer of June 2020 (The Hindu, Citation2020b). Similarly, various reports also suggest a looming threat to the geographical and cultural relevance of the affected areas. For instance, Majuli, a district in Assam, the ‘largest river island in the world’, has been eroded from 800 to less than 400 km2 (Dainik Assam, Citation2010a; Karmakar, Citation2018) and several historic places of cultural importance are damaged by annual floods and erosion (Dainik Assam, Citation2014a).

Our analysis suggests that media reporting of state and federal government efforts focuses on response and recovery instead of disaster risk reduction and mitigation. Newspapers tend to report rescue operations carried out by the state and federal disaster relief teams (Dainik Assam, Citation2017a, Citation2018); stories from the makeshift relief camps, and issues related to food, drinking water and medicines (Dainik Assam, Citation2015a, Citation2015b). The reports often discuss the insufficient relief measures (Bangladesh Pratidin, Citation2017; The Arunachal Times, Citation2017) with thousands of people becoming homeless and taking shelter on the embankments, as well as lack of re-employment opportunities and generating livelihood options for the flood-affected people (Dainik Assam, Citation2013a; Saikia, Citation2015). The local newspapers have frequently criticized these measures as inadequate. However, reports on disaster risk reduction and mitigation efforts from state and non-state actors do not find sufficient coverage in the media.

Several newspaper articles (n = 305) reverberate mistrust and distrust of government agencies, stating mismanagement and misuse of funds meant for flood prevention and relief. The corruption and abuse of funds are predominantly narrated using three arguments: negligence, speculation of wrong-doing and outright accusation. Negligence emphasizes the passivity of the government agencies, short-sighted and curative approaches, and their lackadaisical attitude towards the woes of flood and erosion (Dainik Assam, Citation2012a, Citation2015c). Whilst speculation of wrong-doing emphasizes third-party assessments, dissatisfaction of civilians, and lack of accountability and transparency of the government agencies (Dainik Assam, Citation2011, Citation2013b), outright accusation involves naming and shaming the responsible government agencies, allegations of corruption, and collusion between state and non-state actors (Chaudhary, Citation2012; Dainik Assam, Citation2012b).

Infrastructure

Our analysis shows that hydropower development is covered extensively in the newspapers, apart from flood-related infrastructures. The media reports from China, India and Bangladesh discuss China’s plan for hydropower development in the Tibet Autonomous Region. While there is consistent reporting on the matter, India’s stance on hydropower development keeps changing but consistently remains opposed to China’s development plans (The Arunachal Times, Citation2010a). In comparison, China has always maintained that its hydropower projects would not impact water flow downstream (The Arunachal Times, Citation2016b). However, it has also ensued mistrust and speculation across boundaries as India seems to be constantly wary of China’s river diversion plans.

China’s reports on hydropower infrastructure reflect the national interest and lack mention of riparian nations’ claims for a shared river (South China Morning Post, Citation2020). With China’s plan for river diversion, India feels threatened. It believes that it should have storage reservoirs to gain water rights in case there is any future dispute on water-sharing and has also developed infrastructures such as monitoring stations at the border to observe the flow of water (Barooah, Citation2011). The Inter-Ministerial Expert Group on the Brahmaputra has claimed China has been planning to develop a series of cascading Run-of-the-River projects in the river’s middle reaches. The same may be replicated in the Great Bend Area as a viable alternative to a single mega-project, which instigated India to call for further monitoring (Kumar, Citation2013).

On the contrary, the media reports hydropower development in Bhutan and India as a sign of cooperation, significant revenue and energy security. The Bhutanese government, however, has also been successful in being conscious about the preservation of the river systems (Palden, Citation2015). Yangka (Citation2015, para. 8) mentions ‘[a]ccess to cheap hydroelectricity had been considered the driver to industrial growth and providing clean energy to the households and commercial entity alike. Direct and indirect benefits from spillover effects far outweigh the apparent negative effects of hydropower projects’.

Another recurrent issue that the media report is the negative impacts of infrastructure development, including the decreased flow of water, displacement of people and loss of biodiversity in the downstream areas (Tayeng, Citation2010). The topic of hydropower development has also initiated debate between the opposition political parties and the ruling government in India, leading to a politicization of the issue and ensuing conflict between state and centre, between citizens and the state and central governments (The Arunachal Times, Citation2010c; The Assam Tribune, Citation2012a). The centre is often accused of not taking up the issue of hydropower development seriously with China by the state authorities and citizens (The Assam Tribune, Citation2016b). The Indian civil society has also been critical of the state, being the voice for the riverine communities and establishing their rights over the water, questioning the authoritative nature of the federal government and lack of accountability in making the communities part of the decision-making process (Dainik Assam, Citation2016e; The Assam Tribune, Citation2014b). Media reports suggest that there have been conflicts between civilians and state (federal) actors with claims of propaganda that the state with private actors is to implement water infrastructure with inadequate information provided in the detailed project report (Dainik Assam, Citation2015d). While there have been instances of violence against protesting civilians for unlawfully overriding the rights of the indigenous communities (Ajum, Citation2010), the governments have been questioned multiple times on account of flawed environmental impact assessments and project clearance practices.

The Indian media reports also include discussion about flood infrastructures, such as embankments, to reduce the impacts of annual floods but have also been used as border security between India and Bangladesh to check and restrict infiltration from Bangladesh to India (Dainik Assam, Citation2016b). Reports indicate that embankments and dykes are a standard adaptation measure across India and Bangladesh, but there are accounts of breaching every flood season. To prevent erosion, the state representatives often resort to ad-hoc measures such as placing sandbags, porcupines, etc., to prevent erosion. Citing the inefficiencies of ad-hoc measures to prevent erosion (Dainik Assam, Citation2016c), people often demand long-term adaptation measures facilitated by new engineering breakthroughs (Dainik Assam, Citation2016d).

Besides infrastructures concentrating on hydropower development and floods, transportation infrastructures have also been reported.

Stating that huge potential is waiting to be tapped on maritime, trade, and commerce fronts, the Union Minister of State for Shipping is seeking cooperation and collaboration among the BIMSTEC countries. An agreement for the Brahmaputra River protocol route with Bangladesh has already been signed (The Hindu, Citation2019a).

Certain accounts emphasize the importance of inter-country and inter-state cooperation for improving road connectivity and waterways across different corridors (The Arunachal Times, Citation2016a). Reports also suggest the development of policies for improved institutional infrastructure for basin development and to address the issues of flood and erosion (The Assam Tribune, Citation2014a).

Sovereignty and securitization

The media reporting suggests that national sovereignty and securitization issues are a significant source of tension among the riparians in the Brahmaputra basin. The issues are repeatedly raised in claims over the water as a sovereign resource and border security. For instance, the media reports demonstrate that India is sceptical of China’s actions, and its decisions can severely threaten the water rights of the downstream riparians (Dainik Assam, Citation2016a; The Assam Tribune, Citation2016d). China, however, has continuously argued that its hydropower dams are run-of-the-river and will not have adverse impacts on the downstream region, ‘Our hydropower development in Tibet falls under the country’s broad sector planning and meets strict standards. They will not have much impact on the environment, or any impact on downstream water supplies’ (South China Morning Post, Citation2016, para. 4). Nevertheless, India’s troubled relationship with China is evident by the tensions at the Line of Actual Control, China’s refusal to Nuclear Suppliers Group membership of India (Bhattacharjee, Citation2017a), China’s refusal to have a water treaty with India (The Arunachal Times, Citation2018), and both the countries being unable to establish a concrete cooperative mechanism beyond data-sharing (The Hindu, Citation2013a).

Moreover, India struggles with a looming fear (Subramanian, Citation2013; The Hindu, Citation2013b), frequently fuelled by state and non-state actors. For instance, a parliamentary standing committee on water resources mounted pressure on the central government to increase surveillance after it confirmed that it is not keeping a satellite vigil on the flow of water from China (The Assam Tribune, Citation2013). There was also uneasiness at the state/provincial level as it was assumed that China was planning to divert the waters of the Brahmaputra (The Assam Tribune, Citation2015), following which India (federal level) had to have several consultations with China (Patowary, Citation2018), which to date are still open for speculation.

India pushes for hydropower development in the Brahmaputra basin to claim its territorial sovereignty over the river. It cleared the construction of the 800 MW Tawang-II Hydroelectric Project in Arunachal Pradesh in response to China’s hydropower development plans (Barooah, Citation2013). Media reports suggest that the environmental impact or well-being of the people is secondary when it comes to establishing user rights. For instance, in January 2011, the Union Ministry of Power argued that the timely grant of environment and forest clearances for the proposed hydel projects was crucial to ensure India’s right over the Brahmaputra (The Assam Tribune, Citation2011). Recently, when China announced the construction of a super dam in Tibet, India responded by planning to build a 10 gigawatt hydropower project on the Brahmaputra (Purohit, Citation2020), which, however, as claimed by Indian officials, is inadequately assessed and may trigger flash floods or create water scarcity downstream as per a Chinese media report (South China Morning Post, Citation2020). While China is also planning hydropower development upstream, they have only provided assurance, as opposed to evidence, that projects will undergo scientific planning considering the impact on the downstream areas. In terms of border security, the Bogibeel bridge, the country’s longest rail-cum-bridge across the Brahmaputra, is developed not only to provide better connectivity to upper Assam and Arunachal Pradesh but also to strengthen national security as it cuts down by 10 hours access to the border with China in case troops and supplies must be moved in a state of emergency (Chowdhary, Citation2018).

In the case of Bangladesh and India relationships, media reports suggest that although Bangladesh is concerned about water rights, it endeavours to maintain a good relationship with India. The Prime Minister of Bangladesh, Sheikh Hasina, wrote for The Hindu (India), appealing to resolve issues between the two nations peacefully. There should be no contention over the shared waters (Hasina, Citation2017). India, too, has taken a participatory approach to constructing hydropower projects on rivers it shares with Bangladesh, which has helped keep the sovereignty debate at bay (Dikshit, Citation2013). However, Indian media reports that the federal government is concerned about the open river borders with Bangladesh, which often leads to illegal immigration and territorial conflict, leading to stringent border protection (Dainik Assam, Citation2016b).

Media’s reporting on data and scientific research

From our analysis, lack of basin-level scientific research and lack of information-sharing seems to be the two emerging concerns. There is an overall lack of scientific research in the basin and research-related articles reported in the media, as only limited articles (n = 34) on research among 2437 articles published. Academicians, CSOs and government representatives acknowledge that the Brahmaputra valley, despite being one of the most hazard-prone regions of the country, has remained understudied (Sharma, Citation2013), including the technical subjects that usually find space in river research (hydrology, disaster, flood management, hydropower development, etc.). Even the ‘essential’ scientific research conducted for environmental and social impact assessment during the clearance of developmental initiatives has been claimed to be inaccurate in the media reports, leading to a lack of trust in the federal government in India (The Arunachal Times, Citation2010b). Our findings suggest that only a handful of studies were conducted to understand climate change impacts in the basin. While there have been only a limited number of studies conducted in the Brahmaputra basin to predict the impacts of climate change (Apurv et al., Citation2015), it is also possible that the media is not reporting enough climate research due to the disconnect between academia and media.

The limited newspaper articles report on collaborative research being encouraged among the riparian nations, which could be an avenue of cooperation. For example, through inland waterways between India and Bangladesh, and understanding the changing river quality of the shared resource (People’s Daily, Citation2016a; The Arunachal Times, Citation2016a). Scientific research initiatives on issues of common interest have also been taken only on an ad-hoc basis, as per the reports. For instance, newspapers have extensively reported on Siang’s water turning muddy, claiming that China’s water diversion has led to this issue. At the same time the most probable cause was understood to be a high-intensity earthquake that happened in Tibet. Both India and China made efforts to inquire about the reason for leading to a passive conflict (The Arunachal Times, Citation2017a).

Apart from conflicts, various newspaper reports also indicate instances of cooperation. For instance, the India Meteorological Department has been claimed to have collaborated with meteorological agencies in China and Pakistan, among others, to provide climate forecast services to countries in the Hindu Kush region and its rivers (Koshy, Citation2019). Under the existing bilateral hydrological data-sharing agreement, China agreed to provide flood data to India on the Brahmaputra for a longer duration, from May to October (The Assam Tribune, Citation2013a). There is also a channel of communication and cooperation between China and Bangladesh, sharing knowledge to propose development initiatives in Bangladesh (People’s Daily, Citation2016a). While instances of cooperation are evident, there is still reluctance among the nations to share data related to the river due to national security. For example, territorial disputes have led to the withholding of data; during the Doklam standoff, China did not share flood season data with India, although the conflictual claims have been denied by China (Bhattacherjee, Citation2017b).

As mentioned in the fourth section, infrastructural measures that have been adapted for disaster risk eduction have often failed. However, reports suggest that scientific research on adaptation to flooding events still relies on engineering-based methods such as hydrological and mathematical modelling, supported by state representatives and academics in India and Bangladesh (Patowary, Citation2014). In comparison, civil society generates an effort to assess the communities’ vulnerability to disasters and develop a cultural understanding of the river through narratives generated along the river course (The Assam Tribune, Citation2016a; The Hindu, Citation2014a). Media also reports the data generated and shared for the loss incurred every year during floods (Prothom Alo, Citation2017a), lives, livelihood, infrastructure, and land in India and Bangladesh. They also provide an account for area-wise relief and rehabilitation provision and, in certain instances, also account for the failure of the authorities to provide an adequate post-disaster response (The Daily Star, Citation2014a).

Reports suggest that the initiation of in-depth scientific research is also crucial to pique the interest of the central government of India which has not considered these disasters to be of national interest yet (Dainik Assam, Citation2014b). For example, Bangladesh has recently started predicting the estimated loss from the anticipated seasonal floods (Prothom Alo, Citation2013a). The case of better governance is primarily endorsed by CSOs and to a lesser extent by academicians and state representatives, particularly in India. They demand modifications in the current disaster policy (Dainik Assam, Citation2017b), restructuring of the existing institutional mechanism (The Hindu, Citation2012), and the onus of accountability to be on the local administration (Duarah, Citation2014). There have been certain developments in India for constituting research-based institutions, perhaps to enhance scientific research in climate change and disaster risk eduction, such as the Northeast Water Resources Authority (NEWRA), through centre-state governments coordination (The Assam Tribune, Citation2010a). During the flood season, in the lower Brahmaputra basin, cooperation also takes the form of data-sharing across countries. It is conducted in terms of early warning (Prothom Alo, Citation2018a) and flood warning (Prothom Alo, Citation2016a) to support the downstream vulnerable communities to prepare for the floods (The Hindu, Citation2017a).

Discussion

In this section we reflect on the key findings of this research and what role can media play in shaping the future of the Brahmaputra basin.

First, our study shows that most newspaper articles focus on conflicts in the Brahmaputra basin. In South Asia, the conflicts have been brewing since the colonial era, and as a remnant, the geopolitical conflict between countries persists via territorial and historical disputes (Ganguly et al., Citation2019). These disputes have a spillover effect on transboundary waters, making water a pawn in multidimensional conflicts in the region (Warner & Vij, Citation2022). Although the countries have a shared history, with myriads cultural, social and spiritual connections, these common grounds do not find much space in the media reporting. Specific media reports have been promoting a false narrative of ‘water wars’ and creating a geopolitical environment of scaremongering (Warner & Vij, Citation2022). Although Wolf (Citation1999) has shown no evidence of water wars, the media continues to report on the narrative of extreme militarized water conflicts.

Conflict and cooperation are part of a water interaction continuum (Barua & Vij, Citation2018; Mirumachi, Citation2015); however, the media continues a lopsided reporting of conflicts in the Brahmaputra basin. This is against the global trends, where between 2000 and 2008, only 33% of the recorded transboundary events worldwide have been identified as conflictive, while the remaining events were classified either as cooperative (63%) or neutral (4%) (De Stefano et al., Citation2010). Most of the conflictive events between 2000 and 2008 have been recorded in South Asian basins, followed by Eastern Europe, North America, Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) region (De Stefano et al., Citation2010). In Southeast Asia, the Lancang–Mekong is witnessing a current trend of cooperative sentiments, with the events that are positively reported on by the media being those that aid in connecting leaders and project developers between riparian countries, including bilateral and multilateral cooperation (Wei et al., Citation2021). However, in the Nile basin, biased reporting has often resulted in conflict-oriented narratives, where the media has assumed more a biased role in the negotiation process (Woldemaryam, Citation2020).

Moreover, our study shows that the reporting on stakeholder cooperation at track 3, 2, and 1.5 levels is very sparse and limited (Barua, Citation2018). Diplomatic efforts by the governments (state to state) are termed track 1 diplomacy (Nishat & Faisal, Citation2000). Tracks 2 and 3 diplomacy refer ‘to a broad range of unofficial contacts and interaction aimed at resolving conflicts, both internationally and within states’ (Montville, Citation1991). Track 1.5 is senior bureaucrats of the concerned governments interacting to deliberate on an issue of concern. Even reporting on annual floods is often supplemented with a conflict between citizens and the state or between the riparian states (The Arunachal Times, Citation2010c; The Assam Tribune, Citation2012a). Discussing conflicts can be an ‘easy sales pitch’; on the pitfall, it acts as a catalyst for dormant disputes to become active. We can argue that certain media houses are organized to pursue profits in a capitalist world, and conflict-oriented discourse often tends to find a larger audience (Cottle, Citation2006). Media reporting is not just about numbers and the craving for ‘sensational’ news but holding the power to scrutinize what is ‘newsworthy’ through encoding the ‘culturally dominant assumptions of society’, often delegitimizing dissent. For example, conflict-oriented narratives on hydropower development between the upstream nations find an audience, wherein reasoning and evidence might not be as legitimate as the assumptions underlying historical mistrust, which has been sustained over decades. What might be favourably consumable is the prevailing distrust, which media might keep reproducing.

The discourse of water scarcity on transboundary water governance in the case of Jordan enlisted four reasons that have been constructed by the government and reproduced by mainstream mass media, becoming the dominant discourse in the country. It held accountable the nature, climate change and aridity, and external factors such as resource-sharing with neighbouring countries, population growth, immigration and refugees, as causes of water scarcity. In doing so, the discourse emphasized that the issue is about the limited water resources in the country and that there is a need to increase the supply to address the growing demand. However, the underlying cause is the mismanagement of the existing water resources and appeal should be towards solutions on the demand side. Contrarily, the Jordanian government is mainly pushing for supply-side management, which would also allow not challenging the current water uses (Hussein, Citation2019). The solutions encouraged by the government, consequently, have been infrastructure development based, construction of the Disi Canal project and the Wahda Dam, Jordan, wants to claim and increase their sharing rights on transboundary water resources (Hussein, Citation2016, Citation2019).

The media’s production and dissemination of ‘dominant frames’ are oriented to the pursuit of dominant economic interests and political power (Cottle, Citation2006; Herman & Chomsky, Citation1988). ‘Many water-related interactions occur without being reported by media; they simply may not be deemed newsworthy or be deliberately kept far from the media focus for strategic reasons’ (De Stefano et al., Citation2010, p. 873). But analysis of how water events are reported help understand the cooperation and conflicts around transboundary water resource (De Stefano et al., Citation2010). Authoritative and populistic regimes have also leveraged media to frame discourses that help in gaining electoral advantages and profits. Similarly, it is observed that with changing political regimes, the relationship with the riparian states also takes a different course (Mukhtarov & Gerlak, Citation2013). It is also reflected in our analysis that India until 2014 was taking a more diplomatic approach with China while later it took a comparatively hostile turn (Doklam standoff), leading also to decreasing reports on the basin in recent years (2018–20), and the reports, if not about floods, have been dominated by conflict-oriented narratives. This change in approach can be attributed to a change in the political regime in India (2014), with striving hard to achieve the status of a hegemon by consolidating its dominant position in South Asia and often being too confrontational with China (Bajpai, Citation2017). The discourse framed by the media is that of an ‘assertive government’, a section of the masses consuming this narrative would assume the regime of being decisive and for another section, it might just be an ideological alignment, authoritarian politics over dialogue, and diplomacy.

Second, the reporting in the Brahmaputra basin witnesses gender and knowledge disparity in terms of both scientific research and media reporting. For instance, the media has mainly focused on natural science, emphasizing geomorphology, hydrology and climate aspects of the river. Such a focus is probably due to scientific research being limited to natural sciences, with limited attention to understanding human–water relations. Similarly, reporters from the basin are predominantly male, so are the respondents, indicating that male reporters are only reaching out to male scientists who have dominated the water sector (physical aspects) historically and continue to do so, even now. A 2019 report on gender inequality in India pointed out that women by-line just about 27% of the front-page articles in India’s top six English dailies, and across English and Hindi newspapers, three out of every four news articles are authored by male journalists (Agarwal, Citation2019). This has also resulted in how the problems and solutions in the river basins are perceived. An engineering lens, ‘taming of the river’, is often considered for flood control and tapping the potential of the river hydropower production, as observed in the fourth section. This framing of development still seems to persist as a colonial hangover, often considered the only solution in the absence of alternative research.

Third, several media reports in our study show that extensive infrastructure and technocratic solutions have failed in flood control, although favoured as an adaptation mechanism by the government and the citizens alike as these interventions have been the norm for decades (The Assam Tribune, Citation2016c; The Daily Star, Citation2015a). So, while infrastructure development is perceived as an indicator of modernity, it might not be an effective solution to reduce the impacts of disasters. On the other hand, hydropower infrastructure development has witnessed vehement opposition from local communities in India (Dainik Assam, Citation2016e), as they have regularly been left out of the infrastructure planning processes. The lack of a transparent process in development leaves citizens feeling violated regarding their water rights, often leading to conflict between the citizens and the state. The protesting citizens have repeatedly been declared anti-national, especially in recent times, for not complying with the development propaganda of the populistic government in India (The Arunachal Times, Citation2020a). The development of infrastructures often seems to be an underlying reason for conflicts. Menga (Citation2017) argues that the internet and media have indeed been instrumental in the framing of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam as a crucial resource and in reaching out to and convincing the Ethiopian diaspora. It reinstates the fact that media is not only for discussing liberating opinions and sharing facts but can also serve as a tool for state-building (Gagliardone, Citation2016). Competition for resource access between India and China pushes governments to take unilateral decisions for claiming sovereignty. To encourage inclusive water governance and avoid unilateral decision-making, an improved understanding of human–water interactions is a prerequisite, emphasizing diplomacy and dialogue between the communities and the decision-makers, with media playing a role in avoiding myths and post-truth.

Conclusions

This article shows how the media reported the conflicts and cooperation in the Brahmaputra River basin between 2010 and 2020. We have found that most articles are focused on the conflicts, especially on the themes of hydropower development, disasters and geopolitical disputes in the basin. With such extensive coverage of issues in the Brahmaputra basin, we suggest that there are limited media reporting on the avenues of cooperation, including the informal water diplomacy initiatives, opportunities for joint research and cultural aspects that bring the riparians together.

We conclude that the media can play a significant role on two fronts. First, it can push for multilateral negotiations (tracks 2 and 3) between the riparian nations, as expressed through initiatives such as the Abu Dhabi Dialogue, the Brahmaputra Dialogue and Ecosystems for Life. The inclusion of media in such informal diplomacy initiatives will enable state and non-state policy actors to build trust over media to include them as essential actors. It can also help rebrand the media’s image to promote cooperation in water diplomacy. For instance, the media meetings were conducted separately from other state actors’ meetings in the Brahmaputra Dialogue initiative. However, as the trust was built between the journalists and other actors, the journalists were invited during the multi-stakeholder track 2-level meetings. Understanding domestic voices can facilitate in terms of designing outreach of media to a network of local communities and policy actors. For this, media needs to act as an umbrella network centred on a transboundary issue coordinating among media networks across borders. The formation of a media collective to resolve the political deadlock in the Indus River basin acknowledges that ideas and norms can have the power to influence discussions with regard to transboundary water governance (Suhardiman et al., Citation2017).

Second, the media can uphold the demand for de-securitizing data by emphasizing the need in their reports, supplementing it with evidence from academia and policy scholars. Newspaper coverage can positively influence societal awareness and knowledge, motivating society towards collective action. Moreover, to achieve political vantage for de-securitization of data, media is an essential platform for opinion formulation and legitimization. The role of media in advocating for water diplomacy and communication, for disseminating information, is vital, as it had for bringing the issues of climate change to a global agenda (Schmidt et al., Citation2013).

We call upon print media (newspapers), scientists and policymakers to actively engage in informal water diplomacy processes to improve science–media interlinkages and communication with the public. While formal (track 1) diplomacy still does not see much participation from tracks 2 and 3, the traditional forms of media have the power to shape public discourses and influence the deliberations at high-level national and transnational meetings. Collaborative and objective reporting from the print media (newspapers) can push the riparian states towards water cooperation, rather than inflating existing points of conflict or awakening the dormant conflicts of the past.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.1 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank Vijayeta Rajkumari, Mousumi Baruah, Darshana Jadhav, Yash Vinay Somkuwar and Maliha Anjum for their assistance in data collection and cleaning. We also thank the editor of IJWRD and two anonymous reviewers for providing constructive suggestions to improve earlier versions of the manuscript. The authors contributed to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Sumit Vij and Arundhati Deka; data collection: Arundhati Deka and Natasha Hazarika; analysis and interpretation of the results: Arundhati Deka, Natasha Hazarika and Sumit Vij; draft manuscript preparation: Arundhati Deka, Natasha Hazarika, Sumit Vij, Anamika Barua and Emanuele Fantini. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2022.2163478

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agarwal, C. (2019). It’s 2019 but women barely figure in top positions, panels and pages in the media. Newslaundry. Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.newslaundry.com/2019/08/02/media-rumble-un-women-report-gender-inequality-indian-media

- Ajum, T. (2010). Organizations questions lathi charge and firing at protestors. The Arunachal Times. Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://www.arunachaltimes.in/archives/may%2028.html

- Apurv, T., Mehrotra, R., Sharma, A., Goyal, M. K., & Dutta, S. (2015). Impact of climate change on floods in the Brahmaputra basin using CMIP5 decadal predictions. Journal of Hydrology, 527, 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2015.04.056

- The Arunachal Times. (2010a). APCC opposes Tsangpo Dam, Cabinet clears Dam Safety Bill. Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://www.arunachaltimes.in/archives/may%2014.html

- The Arunachal Times. (2010b). AdiSU oppose proposed hearing on Lower Siang project. Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://www.arunachaltimes.in/archives/may%2018.html

- The Arunachal Times. (2010c). BJP will stop big dams in NE at all costs. Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://www.arunachaltimes.in/archives/nov%2018%20.html

- The Arunachal Times. (2016a). BCIM corridor: The road map for Northeast. Retrieved January 16, 2021, from https://www.arunachaltimes.in/archives/dec16%2002.html

- The Arunachal Times. (2016b). Don’t harm downstream states: Centre to China. Retrieved January 15, 2021, from https://www.arunachaltimes.in/archives/mar16%2011.html

- The Arunachal Times. (2017). Food crisis looming large in Anjaw: Floods threat Eastern Arunachal. Retrieved January 16, 2021, from https://www.arunachaltimes.in/archives/aug17%2014.html

- The Arunachal Times. (2017a). Earthquakes most probable cause of Siang turning muddy: Study. Retrieved January 16, 2021, from https://arunachaltimes.in/index.php/2017/12/27/earthquakes-most-probable-cause-of-siang-turning-muddy-study/

- The Arunachal Times. (2018). AAPSU supports the proposed dharna to demand a water treaty with China. Retrieved January 16, 2021, from https://arunachaltimes.in/index.php/2018/10/24/aapsu-supports-proposed-dharna-to-demand-water-treaty-with-china/

- The Arunachal Times. (2020a). Seminar on hydropower development. Retrieved January 17, 2021, from https://arunachaltimes.in/index.php/2020/02/12/seminar-on-hydropower-development/

- The Assam Tribune. (2010a). State moves Centre to take up issue. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- The Assam Tribune. (2011). Hydel projects to thwart Chinese designs. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- The Assam Tribune. (2012a). River diversion fears misplaced: Centre. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- The Assam Tribune. (2013). Panel asks Govt to step up vigil. Retrieved September 23, 2020.

- The Assam Tribune. (2013a). Agreement inked on trans-border rivers. Retrieved September 23, 2020.

- The Assam Tribune. (2014a). Panel formed to fight flood, erosion. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- The Assam Tribune. (2014b). Green tribunal seeks replies by parties. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- The Assam Tribune. (2015). Concern over diversion of Brahmaputra by China. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- The Assam Tribune. (2016a). Seminar on Brahmaputra tomorrow. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- The Assam Tribune. (2016b). BJP MP opposes dam on Brahmaputra. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- The Assam Tribune. (2016c). Bhuragaon, Lahorighat areas hit by river bank erosion. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- The Assam Tribune. (2016d). China has blocked Brahmaputra channel: Govt. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- Bajpai, K. (2017). Narendra Modi’s Pakistan and China policy: Assertive bilateral diplomacy, active coalition diplomacy. International Affairs, 93(1), 69–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiw003

- Bangladesh Pratidin. (2015). Millions of people are inundated in Kurigram and Lalmanirhat. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- Bangladesh Pratidin. (2017). Extreme food shortage has occurred in flood-hit areas. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- Barooah, K. (2011). Brahmaputra water flow being monitored. Retrieved September 21, 2020, from The Assam Tribune.

- Barooah, K. (2013). Tawang II hydel project cleared. Retrieved September 22, 2020, from The Assam Tribune

- Barua, A. (2018). Water diplomacy as an approach to regional cooperation in South Asia: A case from the Brahmaputra basin. Journal of Hydrology, 567, 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2018.09.056

- Barua, A., Deka, A., Gulati, V., Vij, S., Liao, X., & Qaddumi, H. M. (2019). Re-interpreting cooperation in transboundary waters: Bringing experiences from the Brahmaputra basin. Water, 11(12), 2589. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11122589

- Baruah, S. (2012). Whose river is it anyway? Political economy of hydropower in the Eastern Himalayas. Economic and Political Weekly, 47(29), 41–52. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41720014

- Barua, A., & Vij, S. (2018). Treaties can be a non-starter: A multi-track and multilateral dialogue approach for Brahmaputra Basin. Water Policy, 20(5), 1027–1041. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2018.140

- Barua, A., Vij, S., & Zulfiqur Rahman, M. (2018). Powering or sharing water in the Brahmaputra River basin. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 34(5), 829–843. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2017.1403892

- Belay, Y. D. (2014). Mass media in Nile politics: The reporter coverage of the grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. Journal of Power, 2(2), 181–203.

- Bhattacharjee, K. (2017a). No data from China on Brahmaputra this year. The Hindu. Retrieved November 3, 2020, from https://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-national/no-data-from-china-on-brahmaputra-this-year/article19520875.ece

- Bhattacherjee, K. (2017b). India–China border talks today. The Hindu. Retrieved November 3, 2020, from https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/20th-round-of-india-china-border-talks-today/article22178787.ece

- Bisht, M. (2019). From the edges of borders: Reflections on water diplomacy in South Asia. Water Policy, 21(6), 1123–1138. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2019.124

- Boyce, J. K. (1990). Birth of a megaproject: Political economy of flood control in Bangladesh. Environmental Management, 14(4), 419–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02394131

- Burell, G., & Morgan, G. (1979). Sociological paradigms and organizational analysis. Elements of the Sociology of Corporate Life.

- Carvalho, A. (2007). Ideological cultures and media discourses on scientific knowledge: Re-reading news on climate change. Public Understanding of Science, 16(2), 223–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662506066775

- Carvalho, A. (2010). Media (ted) discourses and climate change: A focus on political subjectivity and (dis) engagement. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 1(2), 172–179. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.13

- Chaudhary, J. K. (2012). People feel cheated after the Brahmaputra Board started work in April. Retrieved March 21, 2021, from Dainik Assam.

- Chowdhary, R. D. (2018). Bogibeel Bridge is vital for the nation’s security. Retrieved September 28, 2020, from The Assam Tribune.

- Chowdhury, N. T. (2010). Water management in Bangladesh: An analytical review. Water Policy, 12(1), 32–51. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2009.112

- Cottle, S. (2006). Mediatized conflict: Developments in media and conflict studies. Open University Press.

- Crow, D. A., & Lawlor, A. (2016). Media in the policy process: Using framing and narratives to understand policy influences. Review of Policy Research, 33(5), 472–491. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12187

- The Daily Star. (2014a). Flood hits 6 more districts. Retrieved February 28, 2021, from https://www.thedailystar.net/flood-hits-six-more-districts-39431

- The Daily Star. (2015a). Dyke collapse inundates 30 Gaibandha villages. Retrieved March 2, 2021 from https://www.thedailystar.net/country/dyke-collapse-inundates-30-gaibandha-villages-139942

- Dainik Assam. (2010a). 2,72,183 bigha land in Majuli eroded in 39 years. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- Dainik Assam. (2010b). Panel creation by centre to claim Indian share of Brahmaputra internationally. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- Dainik Assam. (2011). Loose measures to prevent erosion in the last 10 years. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- Dainik Assam. (2012a). More flood prone areas in Assam as compared to other states and still it is not a National issue. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- Dainik Assam. (2012b). Corruption charges against water resources department of 12 hundred crores. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- Dainik Assam. (2013a). Erosion issues in Jajimukh. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- Dainik Assam. (2013b). Demand to discontinue the Brahmaputra Board in Majuli. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- Dainik Assam. (2014a). Brahmaputra and Subansiri threatening Majuli. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- Dainik Assam. (2014b). Without analysis of the Brahmaputra flood cannot be made a national issue. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- Dainik Assam. (2015a). AASU distributes food and medicines among flood affected. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- Dainik Assam. (2015b). Chief secretary went to understand the flood situation. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- Dainik Assam. (2015c). Erosion in Dikhou. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- Dainik Assam. (2015d). Preservation and revival of Kalang-Bharalu. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- Dainik Assam. (2016a). China–India to have discussion. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

- Dainik Assam. (2016b). Inspection of river’s border in Dhubri. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

- Dainik Assam. (2016c). Unfulfilled promises of Modi–Sonowal. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

- Dainik Assam. (2016d). New ways to fight flood-erosion speculated by Union Water Resource Minister. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- Dainik Assam. (2016e). Protest against big dam. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- Dainik Assam. (2017a). Violent flood in Dhemaji and Lakhimpur. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- Dainik Assam. (2017b). Govt. heedless towards erosion and flood. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- Dainik Assam. (2018). Siang river entering into Brahmaputra. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- De Stefano, L., Edwards, P., De Silva, L., & Wolf, A. T. (2010). Tracking cooperation and conflict in international basins: Historic and recent trends. Water Policy, 12(6), 871–884. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2010.137

- Dieperink, C. (2011). International water negotiations under asymmetry, Lessons from the Rhine chlorides dispute settlement (1931–2004). International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 11(2), 139–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-010-9129-3

- Dikshit, S. (2013). New Delhi invites Dhaka’s stake in dams on common rivers. The Hindu. Retrieved November 1, 2020, from https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/new-delhi-invites-dhakas-stake-in-dams-on-common-rivers/article4358241.ece

- Doulton, H., & Brown, K. (2009). Ten years to prevent catastrophe?: Discourses of climate change and international development in the UK press. Global Environmental Change, 19(2), 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.10.004

- Duarah, R. (2014). Sonowal for new approach. Retrieved September 25, 2020 from The Assam Tribune.

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Towards clarification of a fractured paradigm. McQuail’s Reader in Mass Communication Theory, 390, 397. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

- EurAsian Times Desk. (2020). China may trigger ‘flash-floods’ in India’s Arunachal if Delhi attempts to choke Pakistan’s water supply. Retrieved December 7, 2021, from https://eurasiantimes.com/china-may-trigger-flash-floods-in-indias-arunachal-if-delhi-attempts-to-choke-pakistans-water-supply/

- Frenken, K. (2012). Irrigation in Southern and Eastern Asia in figures: AQUASTAT Survey-2011. Water Reports, 37. https://www.fao.org/3/i2809e/i2809e.pdf

- Frontier Weekly. (2018). Silt from Bhutanese Rivers. Retrieved July 14, 2022, from https://www.frontierweekly.com/articles/vol-51/51-9/51-9-News%20Wrap.html

- Gagliardone, I. (2016). The politics of technology in Africa: Communication, development, and nation-building in Ethiopia. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Ganguly, S., Smetana, M., Abdullah, S., & Karmazin, A. (2019). India, Pakistan, and the Kashmir dispute: Unpacking the dynamics of a South Asian frozen conflict. Asia Europe Journal, 17(1), 129–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-018-0526-5

- Grafton, R. Q., Wyrwoll, P., White, C., & Allendes, D. (2014). Global water issues and insights. ANU Press.

- Hasina, S. (2017). Friendship is a flowing river: Sheikh Hasina writes for The Hindu. The Hindu. Retrieved December 12, 2021, from https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/friendship-is-a-flowing-river/article62113387.ece

- Herman, E. S., & Chomsky, N. (1988). The political economy of the mass media. Pantheon Books.

- The Hindu. (2010). Melting Himalayan glaciers to have varying impact on river basins. Retrieved December 10, 2021, from https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/energy-and-environment//article60631978.ece#:~:text=The%20melting%20of%20glaciers%20in,food%20security%20in%20some%20areas

- The Hindu. (2012). Centre considers restructuring Brahmaputra Board. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- The Hindu. (2013a). Moving forward to stand still. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- The Hindu. (2013b). Civil nuclear energy cooperation on cards. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- The Hindu. (2014a). Experts to study effect of climate change in delta. Retrieved 2 November, 2020.

- The Hindu. (2017a). India’s loss, Bangladesh’s gain. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- The Hindu. (2019a). Call for greater cooperation between BIMSTEC nations. Retrieved November 5, 2020, from https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/andhra-pradesh/call-for-greater-cooperation-between-bimstec-nations/article29912897.ece

- The Hindu. (2020a). Fifty years ago August 7, 1970 Archives: Taming the Brahmaputra. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- The Hindu. (2020b). Assam floods: Number of displaced people almost doubles to 9.26 lakh in less than 24 hours. Retrieved November 7, 2020, from https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/assam-floods-number-of-displaced-people-almost-doubles-to-926-lakh-in-less-than-24-hours/article31939817.ece

- Hussein, H. (2016). An analysis of the discourse of water scarcity and hydropolitical dynamics in the case of Jordan [Doctoral dissertation]. University of East Anglia.

- Hussein, H. (2019). Yarmouk, Jordan, and Disi basins: Examining the impact of the discourse of water scarcity in Jordan on transboundary water governance. Mediterranean Politics, 24(3), 269–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2017.1418941

- IUCN. (2018). Media and CSOs: Collaboration for the future of Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna River basins. Retrieved July 18, 2021, from https://www.iucn.org/news/nepal/201808/media-and-csos-collaboration-future-ganges-brahmaputra-meghna-river-basins

- Jiang, H., Qiang, M., Lin, P., Wen, Q., Xia, B., & An, N. (2017). Framing the Brahmaputra River hydropower development: Different concerns in riparian and international media reporting. Water Policy, 19(3), 496–512. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2017.056

- Karmakar, R. (2018). On a shrinking ‘island’ called Majuli. The Hindu. Retrieved November 6, 2020, from https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/on-a-shrinking-island-called-majuli/article24866047.ece

- Klimes, M., Michel, D., Yaari, E., & Restiani, P. (2019). Water diplomacy: The intersect of science, policy and practice. Journal of Hydrology, 575, 1362–1370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.02.049

- Koshy, J. (2019). India to work with China, Pakistan to gauge impact of climate change. The Hindu. Retrieved November 6, 2020, from https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/energy-and-environment/india-to-work-with-china-pakistan-to-gauge-impact-of-climate-change/article29620759.ece

- Krishnan, A. (2017). Earthquake likely caused Brahmaputra’s turbidity, says China. India Today. Retrieved February 2, 2021, from https://www.indiatoday.in/world/story/china-earthquake-brahmaputra-turbid-1117046-2017-12-27

- Krishnan, A. (2021). China gives green light for first downstream dams on Brahmaputra. The Hindu. Retrieved March 22, 2021, from https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/china-gives-green-light-for-first-downstream-dams-on-brahmaputra/article34014912.ece

- Kumar, V. (2013). Expert group calls for monitoring China’s run-of-the-river projects. The Hindu. Retrieved November 3, 2020, from https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/Expert-group-calls-for-monitoring-China%E2%80%99s-run-of-the-river-projects/article12190671.ece

- Leitch, C. M., Hill, F. M., & Harrison, R. T. (2010). The philosophy and practice of interpretivist research in entrepreneurship: Quality, validation, and trust. Organizational Research Methods, 13(1), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428109339839

- Linnerooth, J. (1990). The Danube River Basin: Negotiating settlements to transboundary environmental issues. Natural Resources Journal, 30, 629–660. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24883595