Abstract

Purpose: Non-dipping nocturnal blood pressure (BP) pattern has been reported prevalent among HIV-infected patients and is associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes. The aims of this observational study were to identify predictors of nocturnal BP decline, and to explore whether diurnal BP profile is associated with alterations in cardiac structure and function.

Materials and methods: A total of 108 treated HIV-infected patients with suppressed viremia underwent ambulatory BP measurement, 51 of these patients also underwent echocardiography.

Results: Non-dipping nocturnal BP pattern was present in 51% of the patients. Decreased nocturnal decline in systolic BP (SBP) correlated with lower CD4 count (rsp = 0.21, p = 0.032) and lower CD4/CD8 ratio (rsp = 0.26, p = 0.008). In multivariate linear regression analyses, lower BMI (p = 0.015) and CD4/CD8 ratio <0.4 (p = 0.010) remained independent predictors of nocturnal decline in SBP. Nocturnal decline in SBP correlated with impaired diastolic function, e’ (r = 0.28, p = 0.049) as did nadir CD4 count (rsp = 0.38, p = 0.006). In multivariate linear regression analyses, nadir CD4 count <100 cells/μL (p = 0.037) and age (p < 0.001) remained independent predictors of e’.

Conclusions: Compromised immune status may contribute to attenuated diurnal BP profile as well as impaired diastolic function in well-treated HIV infection.

Introduction

In the era of antiretroviral treatment (ART), AIDS-related mortality and morbidity has decreased, and HIV infection has become a chronic disease. However, HIV-infected patients experience increased risk of non-AIDS related disease such as malignancies, liver, cardiovascular, and bone disease; conditions that are often associated with ageing [Citation1–3]. This increased risk relates to immune dysfunction before initiation of ART as well as incomplete immune restoration with ART, life-style factors, and adverse effects of ART [Citation1,Citation4,Citation5]. Depletion of CD4 T-cells and chronic activation of CD8 T-cells are hallmarks of HIV infection. With successful ART, CD4 cell count levels generally recover whereas CD4/CD8 ratio most often remains inversed [Citation6,Citation7]. Incomplete immune recovery after successful ART, with persistent lowered CD4 cell count and inversed CD4/CD8 ratio, have been related to increased risk of non-AIDS disease including cardiovascular disease [Citation4,Citation6,Citation8–10]. Nadir CD4 cell count, i.e. the lowest CD4 cell count in the individual history, is a determinator of incomplete immune restoration [Citation6,Citation11,Citation12] and is also a predictor of non-AIDS disease [Citation1,Citation13]. Low nadir CD4 cell count has also been related to prevalent hypertension in HIV-infected cohorts [Citation14,Citation15].

We have earlier reported non-dipping nocturnal blood pressure (BP) pattern to be prevalent among hypertensive HIV-infected patients [Citation16], and this finding has been confirmed by others [Citation17]. In the general population, non-dipping BP during night-time is associated with increased all-cause mortality and risk of cardiovascular events in both normotensive [Citation18,Citation19] and hypertensive individuals [Citation20,Citation21]. Furthermore, non-dipping is associated with organ damage including left ventricular (LV) structural alterations and impairments in diastolic function [Citation22]. HIV infection has, even in the era of ART, been associated with cardiac abnormalities [Citation23–25]. Apart from traditional contributors such as hypertension and cardiovascular disease, markers of inflammation as well as immunosuppression have been found related to cardiac dysfunction and LV hypertrophy [Citation23,Citation24,Citation26]. There is no data regarding diurnal BP rhythm and cardiac organ damage in HIV-infected patients.

In this study, we aimed to identify predictors of attenuated nocturnal decline in BP in ART-treated virologically suppressed HIV-infected patients. Furthermore, we sought to explore whether nocturnal BP decline was associated with alterations in echocardiographic measures of LV structure and function.

Materials and methods

Study population

Patients were recruited from an observational longitudinal study on blood pressure in an unselected cohort of 434 HIV-infected individuals [Citation27]. All HIV-infected patients attending the outpatient clinic at the Department of Infectious Diseases at Oslo University Hospital were invited to participate in the study. Inclusion required written consent, and the South-Eastern Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics approved the study. A total of 147 patients without antihypertensive treatment underwent ambulatory blood pressure (ABP) measurement. Patients who were ART naïve (n = 13), not on current ART (n = 9), or not virologically suppressed on ART (i.e. viral load <50 copies/mL, n = 17) were excluded, leaving 108 participants eligible for analyses. A randomly selected subgroup of 51 out of the 108 participants underwent echocardiographic examination.

Clinical data

Blood pressure was measured at three separate clinical encounters during two time periods in the observational longitudinal study using a semiautomatic oscillometric device (Omron M4, Matsusaka Co. Ltd, Matsusaka, Japan). Hypertension status was classified according to mean BP during each time period [Citation28], and hypertension was defined as mean office systolic BP (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg. Ambulatory BP was measured using an oscillometric device (Spacelab model 90207, Spacelab Medical, Redmond, WA, USA) at 20-min intervals during daytime (07:00–22:00 h) and 60-min intervals during the night (22:00–07:00). Cuff size was selected according to arm circumference on the non-dominant arm. Nocturnal decline in BP was defined as the percentage decrease in average nocturnal SBP at night relative to daytime values. Patients were classified as dippers or non-dippers based on nocturnal decline in SBP above or less than 10%, respectively. Hypertension according to 24 hour (h) ambulatory BP was defined as 24h SBP ≥130 mmHg and/or 24h DBP ≥80 mmHg.

Clinical and laboratory data were obtained from the hospital’s HIV database as previously detailed [Citation27]. Data were obtained at the date nearest to the date of ABP measurement. Overweight and obesity were defined as BMI ≥25 kg/m2 and ≥30 kg/m2, respectively. Duration of HIV infection was estimated as the time period from HIV diagnosis to the time of ABP measurement. Duration of ART was calculated as the cumulative exposure to a triple class regimen. Nadir CD4 cell count was recorded as the lowest CD4 cell count ever before inclusion in the longitudinal study regardless of ART status, and nadir CD4 was reached as ART naive (80%), during ART interruption (10%), or on ART (10%). Current CD4 and CD8 cell count was defined as cell count at the time of ABP measurement, and CD4/CD8 ratio was calculated based on current cell counts. Nadir CD4 cell count, current CD4 cell count, and CD4/CD8 ratio were dichotomized with cut-offs at 100 cells/μL, median value (470 cells/μL), and ratio 0.4, respectively. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was estimated according to the CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) formula, eGFR [Citation29].

Echocardiography

Two-dimensional, M-mode, and Doppler echocardiography were performed during the same week as ABP measurement. The echocardiographic data were analysed blinded to clinical information. With colour coded tissue Doppler, sample volumes were taken from the mitral annulus, lateral and septal position in the four-chamber view and two corresponding positions in the two-chamber view. Early diastolic transmitral flow (E) and early diastolic tissue velocity (e’) were recorded, and E/e’ ratio was calculated. Both E and E/e’ are commonly used parameters reflecting LV diastolic function [Citation30]. Left ventricular length was assessed as the distance from the endocardial border of the apex to the midportion of the mitral annulus plane. As a measure of systolic function, long-axis strain was calculated as mitral annulus displacement as a percentage of LV end-diastolic length, as previously detailed [Citation31]. Left ventricular relative wall thickness (RWT) was calculated as (2 × posterior wall thickness)/LV internal diameter in diastole, and increased RWT was defined as RWT >0.42. Left ventricular mass was estimated by LV cavity dimension and wall thickness recorded at end-diastole in M-mode according to recommendation from American Society for Echocardiography [Citation32] and indexed to body surface area. Concentric remodelling was defined as presence of increased RWT together with normal LV mass index (i.e. <115 g/m2 for men and <95 g/m2 for women) [Citation32]. Long-axis strain <15.7% was considered low [Citation31].

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or, if skewed, as median with interquartile range (IQR). Between-group comparisons were performed using chi-square testing for categorical variables, and the t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables as appropriate. Bivariate correlation coefficients are given as Pearson’s r or Spearman’s correlation coefficient rsp as appropriate. In multivariate linear regression analysis, variables were selected based on clinical evaluation or associations with outcome in univariate analyses (p < 0.2). Nadir CD4 cell count, current CD4 cell count, and CD4/CD8 ratio were dichotomized to fulfill statistical assumptions and to make interpretation easier. Statistical assumptions for the linear regression models were adequately met. The significance level was chosen as p < 0.05. SPSS version 24.0 (IBM® SPSS®) was used for statistical analyses.

Results

Study population with ambulatory blood pressure measurement (n = 108)

Clinical and laboratory data of the 108 participants are presented in . The majority of the study population were middle-aged, white males, 34% were overweight, and 5% were obese. All but one patient had eGFR >60 mL/min. Modes of HIV transmission were homosexual (56%), heterosexual (37%), intravenous drug use (5%), or unknown (2%). The duration of ART ranged from 2 to 15 years. One third (30%) had previous interrupted ART, and all but two patients had been on stable ART for at least nine months at the time of ABP measurement. About one third of the study population (37%) had CD4/CD8 ratio <0.4, and 32% had nadir CD4 cell count <100 cells/μL. Nadir CD4 cell count, current CD4 cell count, and CD4/CD8 ratio were, with one omission, associated with 24h SBP and DBP level with Spearman’s rsp ranging from −0.20 to −0.28 (p = 0.003–0.062).

Table 1. Characteristics of 108 HIV-infected patients with and without diurnal non-dipping blood pressure pattern.

Predictors of nocturnal blood pressure decline

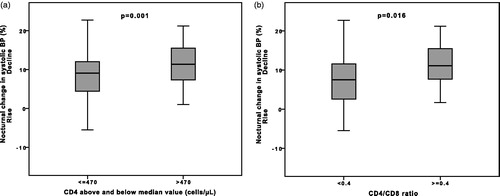

Nocturnal non-dipping pattern was observed in 51% of the patients (). Nocturnal systolic and diastolic BP decline did not differ between hypertensive and normotensive patients either classified by office BP or 24h ABP (p > 0.054). Nocturnal decline in both SBP and DBP correlated with lower CD4 cell count (rsp = 0.21, p = 0.032; rsp = 0.20, p = 0.043) and lower CD4/CD8 ratio (rsp=0.26, p = 0.008; rsp = 0.36, p < 0.001), but not with nadir CD4 cell count. Nocturnal BP decline were lower in patients with CD4 cell count below the median value (8.2 ± 7.1 vs. 11.2 ± 5.3%, p = 0.016) and in those with CD4/CD8 ratio <0.4 (7.0 ± 7.2 vs. 11.4 ± 5.4%, p = 0.001, ).

Figure 1. Nocturnal decline in systolic BP according to (a) two groups of CD4 cell count and (b) two groups of CD4/CD8 ratio.

Univariate regression analyses with nocturnal decline in SBP as outcome are presented in . In multivariate linear regression analyses, CD4/CD8 ratio <0.4 and lower BMI remained independent predictors of reduced decline in nocturnal systolic BP, and the model yielded R2 = 0.202 (). A similar multivariate regression model with nocturnal decline in DBP as outcome yielded identical independent predictors (R2 = 0.210, data not shown).

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate linear analyses with nocturnal decline in systolic blood pressure as outcome, n = 108.

Echocardiography (n = 51)

The characteristics of the randomly selected 51 HIV-infected patients that underwent echocardiography are presented in . Eleven patients (22%) had mildly enlarged left atrium with left atrial area ranging from 20 to 26 cm2, 8% had increased RWT, while no patients had abnormal LV mass. Four patients (8%) fulfilled criteria for concentric remodelling. Patients with hypertension based on 24h ABP (27%) had higher RWT (median 0.38 [IQR 0.33–0.42] vs. 0.32 [0.30–0.37], p = 0.011). Early diastolic tissue velocity e’ ranged from 5.7 to 13.1 cm/s, whereas E/e’ ratio ranged from 4.9 to 12.9. Both e’ and E/e’ correlated with 24h DBP (r = −0.30, p = 0.033 and r = 0.30, p = 0.032, respectively) but not with 24h SBP. All patients had normal LV ejection fraction. Long-axis strain ranged from 14 to 22%, and 16% of the patients had low long-axis strain.

Table 3. Characteristics of 51 HIV-infected patients who performed echocardiography.

Correlations of nocturnal blood pressure decline and immunological markers with echocardiographic parameters

One third of the subpopulation were non-dippers (33%). The clinical, laboratory, or echocardiographic characteristics did not differ between patients with dipping and non-dipping pattern (). Nocturnal decline in both SBP and DBP correlated weakly with e’, but not with other echocardiographic parameters (). Furthermore, nocturnal decline in SBP and DBP correlated with CD4/CD8 ratio (rsp = 0.34, p = 0.013; rsp = 0.32, p = 0.025), but not with nadir or current CD4 cell count.

Table 4. Correlations between selected echocardiographic parameters and immunological markers as well as nocturnal blood pressure decline.

Lower CD4/CD8 ratio correlated with reduced systolic function (long-axis strain, ), whereas lower nadir CD4 cell count correlated with impaired diastolic function (lower e’ () and higher E/e′, rsp =−0.39, p = 0.004). Lower nadir CD4 cell count also correlated with higher RWT ().

Predictors of early diastolic tissue velocity (e’)

Univariate associations with e′ are presented in . In multivariate linear regression analyses, adjusting for nocturnal decline in SBP as well as 24h SBP, nadir CD4 cell count <100 cells/μL (unstandardized β −0.91 [95% confidence interval (CI) −1.76 to −0.06], p = 0.037) and age (unstandardized β −0.07 [95% CI −0.11 to −0.04], p < 0.001) remained independent negative predictors of e’, and the model yielded R2 = 0.417. Decline in SBP did not remain an independent predictor (unstandardized β 0.07 [95% CI −0.01−0.14], p = 0.083).

Discussion

In this study, we have reported findings that link immune dysfunction in HIV to adverse cardiovascular effects. Incomplete immune restoration in virologically suppressed HIV infection with ART seemed to attenuate the nocturnal decline in BP. Other studies reporting on diurnal BP pattern in HIV-infected patients have included normotensive and hypertensive HIV-infected patients with or without ART as well as controls [Citation16,Citation33–35]. All studies have stated non-dipping to be more prevalent in HIV-infected patients. However, only one study explored predictors of nocturnal BP reduction, and De Socio et al. found lower CD4 cell count as well as HIV viremia to be associated with attenuated nocturnal BP decline in an ART naïve, normotensive HIV cohort [Citation35]. Apart from risk of AIDS progression, there were no other determinants of nocturnal BP decline in their cohort. Borkum et al. reported the prevalence of non-dipping unchanged six months after the onset of ART despite rising CD4 cell count [Citation34]. In our cohort of virologically suppressed patients on ART, incomplete immune restoration, expressed by low CD4/CD8 ratio, were independently related to attenuated diurnal BP rhythm. Twenty-two patients were excluded from our study as they were ART naïve or not on current ART. This group had similar prevalence of non-dipping, lower nocturnal BP decline, and lower CD4/CD8 ratio compared to the study population (data not shown). Our findings would be in accordance with the data from de Socio et al., indicating that immune dysfunction is involved in the pathogenesis of blunted diurnal BP in HIV. HIV infection induces immune dysfunction via a wide array of mechanisms, and this dysfunction persists to a variable extent despite successful ART [Citation36,Citation37]. After the onset of ART, CD4 cell count usually restores rather well, whereas quantitative and qualitative defects in the CD8 cell compartment continues [Citation38,Citation39]. Early initiation of ART is associated with reduced CD8 cell activation and improved CD4/CD8 ratio [Citation40]. A persistent inversed ratio is a marker of incomplete immune restoration after ART, and lowered ratio is linked to risk of non-AIDS disease [Citation6,Citation8,Citation41–43]. No fixed threshold for harmful CD4/CD8 ratio has been determined, but a CD4/CD8 ratio below 0.4 and 0.3 have been reported as thresholds for the highest risk of non-AIDS events and non-AIDS mortality [Citation6,Citation42].

Incomplete immune restoration is linked to increased immune activation in HIV [Citation41] which fuels systemic inflammation [Citation5,Citation44]. In the general population, increased systemic inflammation has been described as a determinant of non-dipping BP pattern [Citation45–47] including inflammatory markers linked to endothelial dysfunction [Citation46]. Immune activation and inflammation in HIV is known to promote vascular stiffness and atherosclerosis [Citation5,Citation48,Citation49]. Endothelial dysfunction may induce vascular stiffness through pro-atherogenic stimuli, and endothelial dysfunction and vascular stiffness have been related to impaired nocturnal BP decline [Citation50–52]. Thus, the link between deficient immune reconstitution and attenuated BP decline in our HIV infected cohort could be explained by adverse vascular effects of immune activation and inflammation. We have earlier shown that markers of microbial translocation are predictors of hypertension in HIV [Citation53]. Possibly, adverse vascular effects induced by immune activation and inflammation could also contribute to elevated blood pressure in HIV infection.

Lower BMI also turned out as an independent predictor of nocturnal BP decline. This is a somewhat surprising finding as decreased nocturnal BP decline in the general population is linked to adverse cardiovascular traits such as increasing age, hypertension and increased BMI [Citation54].

Diastolic function reflects the ability of LV relaxation; lower early diastolic tissue velocity e’, and higher early diastolic transmitral flow E/e’ both reflect impaired diastolic function. In the present study, we observed a weak correlation between e’ and nocturnal decline in BP, however, nocturnal BP decline did not turn out as in independent predictor of e’. Additionally, we were not able to show any link between either non-dipping status or nocturnal BP decline with echocardiographic parameters of LV mass and geometry. The lack of independent associations between attenuated nocturnal BP decline and adverse cardiac effects in our population is opposed to the literature on the general population [Citation22], this is a surprising finding that could possibly be explained by lack of statistical power. As far as we know, others have not explored these associations in HIV-infected patients.

In the pre-ART era, systolic heart failure from HIV-associated cardiomyopathy was a well-known complication of advanced disease [Citation55]. After ART became widely available, subtler cardiac abnormalities has been detected by echocardiography and magnetic resonance imaging. These include increased LV mass [Citation26,Citation56], diastolic dysfunction [Citation23,Citation25,Citation56], as well as myocardial remodelling with fibrosis and steatosis [Citation24,Citation57]. In the present study we found that earlier advanced HIV infection, expressed by nadir CD4 cell count <100 cells/μL, were independently related to impaired diastolic function. This finding is in accordance with the data on HIV infection as linked to cardiac dysfunction. Nevertheless, nadir CD4 cell count has not been related to measures of diastolic dysfunction in other studies exploring this association [Citation57–59].

Low nadir CD4 is a determinator of later incomplete immune restoration and a predictor of non-AIDS diseases that are often age-related. The observed independent contribution to impaired diastolic function in our study could be a feature of adverse vascular effects induced by immune dysfunction and immunosenescence. Additionally, high burden of viremia and inflammation in earlier advanced HIV may have caused persistent myocardial damage. Also, those with low nadir CD4 cell count would possibly more often have initiated older ART-regimes. Mitochondrial toxicity, induced by older nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors therapy such as zidovudine, could be a contributor to impaired diastolic function in those with low nadir CD4 cell count [Citation55,Citation60].

We acknowledge several limitations in this study. We did not record reports on sleeping hours, and nocturnal BP is consequently recorded during fixed hours and not during self-recorded sleeping hours as is now recommended [Citation61]. This would probably cause underestimation of nocturnal BP decline and overestimation of the prevalence of non-dipping in our cohort. Furthermore, we do not have data on either cumulative or current exposure to different ART classes or the use of lipid lowering agents at the time of ABP measurement. Additionally, we lack data on metabolic and inflammatory parameters, as well as data on life style. Lack of these data is a limitation, as these parameters would facilitate exploration of other contributors to attenuated BP decline. The study population is small, and only half of the population underwent echocardiographic examination, undermining statistical power. The lack of a HIV-negative control group is another limitation, as matched controls would have made it possible to elucidate HIV-specific contributions to the outcomes. A major strength in this study is the inclusion of virologically suppressed patients on ART and without antihypertensive medication.

In summary, we have reported low CD4/CD8 ratio as an independent predictor of attenuated nocturnal blood pressure decline, and low nadir CD4 cell count as an independent predictor of impaired cardiac diastolic function. Hence, this study show that advanced HIV infection before the onset of ART, as well as incomplete immune restoration after ART have adverse cardiovascular effects. These data supports the knowledge that early initiation of ART is important to prevent adverse cardiovascular outcomes in HIV infection.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients for their participation. We acknowledge the skilled assistance of the staff at the Outpatient Clinic of Nephrology and the Outpatient Clinic of Infectious Diseases at Oslo University Hospital, Ullevål.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Guaraldi G, Orlando G, Zona S, et al. 2011. Premature age-related comorbidities among HIV-infected persons compared with the general population. Clin Infect Dis. 53:1120–1126.

- Freiberg MS, Chang CC, Kuller LH, et al. 2013. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med. 173:614–622.

- Lohse N, Gerstoft J, Kronborg G, et al. 2011. Comorbidity acquired before HIV diagnosis and mortality in persons infected and uninfected with HIV: a Danish population-based cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 57:334–339.

- Deeks SG, Phillips AN. 2009. HIV infection, antiretroviral treatment, ageing, and non-AIDS related morbidity. BMJ. 338:a3172.

- Longenecker CT, Sullivan C, Baker JV. 2016. Immune activation and cardiovascular disease in chronic HIV infection. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 11:216–225.

- Mussini C, Lorenzini P, Cozzi-Lepri A, et al. 2015. CD4/CD8 ratio normalisation and non-AIDS-related events in individuals with HIV who achieve viral load suppression with antiretroviral therapy: an observational cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2:e98–106.

- Leung V, Gillis J, Raboud J, et al. 2013. Predictors of CD4:CD8 ratio normalization and its effect on health outcomes in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. PLoS One. 8:e77665.

- Castilho JL, Shepherd BE, Koethe J, et al. 2016. CD4+/CD8+ ratio, age, and risk of serious noncommunicable diseases in HIV-infected adults on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 30:899–908.

- Lapadula G, Cozzi-Lepri A, Marchetti G, et al. 2013. Risk of clinical progression among patients with immunological nonresponse despite virological suppression after combination antiretroviral treatment. AIDS. 27:769–779.

- Serrano-Villar S, Deeks SG. 2015. CD4/CD8 ratio: an emerging biomarker for HIV. Lancet HIV. 2:e76–e77.

- Robbins GK, Spritzler JG, Chan ES, et al. 2009. Incomplete reconstitution of T cell subsets on combination antiretroviral therapy in the AIDS Clinical Trials Group protocol 384. Clin Infect DIS. 48:350–361.

- Kaufmann GR, Furrer H, Ledergerber B, et al. 2005. Characteristics, determinants, and clinical relevance of CD4 T cell recovery to <500 cells/microL in HIV type 1-infected individuals receiving potent antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 41:361–372.

- Neuhaus J, Angus B, Kowalska JD, et al. 2010. Risk of all-cause mortality associated with nonfatal AIDS and serious non-AIDS events among adults infected with HIV. AIDS. 24:697–706.

- Manner IW, Troseid M, Oektedalen O, et al. 2013. Low Nadir CD4 Cell Count Predicts Sustained Hypertension in HIV-Infected Individuals. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 15:101–106.

- De Socio GV, Ricci E, Maggi P, et al. 2014. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rate of hypertension in HIV-infected patients: the HIV-HY study. Am J Hypertens. 27:222–228.

- Baekken M, Os I, Stenehjem A, et al. 2009. Association between HIV infection and attenuated diurnal blood pressure rhythm in untreated hypertensive individuals. HIV Med. 10:44–52.

- Kent ST, Bromfield SG, Burkholder GA, et al. 2016. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in individuals with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 11:e0148920

- Ohkubo T, Hozawa A, Yamaguchi J, et al. 2002. Prognostic significance of the nocturnal decline in blood pressure in individuals with and without high 24-h blood pressure: the Ohasama study. J Hypertens. 20:2183–2189.

- Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Mojon A, et al. 2013. Blunted sleep-time relative blood pressure decline increases cardiovascular risk independent of blood pressure level–the “normotensive non-dipper” paradox. Chronobiol Int. 30:87–98.

- Fagard RH, Thijs L, Staessen JA, et al. 2009. Night-day blood pressure ratio and dipping pattern as predictors of death and cardiovascular events in hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 23:645–653.

- Salles GF, Reboldi G, Fagard RH, et al. 2016. Prognostic effect of the nocturnal blood pressure fall in hypertensive patients: the ambulatory blood pressure collaboration in patients with hypertension (ABC-H) meta-analysis. Hypertension. 67:693–700.

- Cuspidi C, Sala C, Tadic M, et al. 2015. Non-dipping pattern and subclinical cardiac damage in untreated hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of echocardiographic studies. AJHYPE Hypertens. 28:1392–1402.

- Cerrato E, D'Ascenzo F, Biondi-Zoccai G, et al. 2013. Cardiac dysfunction in pauci symptomatic human immunodeficiency virus patients: a meta-analysis in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. Eur Heart J. 34:1432–1436.

- Thiara DK, Liu CY, Raman F, et al. 2015. Abnormal myocardial function is related to myocardial steatosis and diffuse myocardial fibrosis in HIV-infected adults. J Infect Dis. 212:1544–1551.

- Fontes-Carvalho R, Mancio J, Marcos A, et al. 2015. HIV patients have impaired diastolic function that is not aggravated by anti-retroviral treatment. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 29:31–39.

- Mansoor A, Golub ET, Dehovitz J, et al. 2009. The association of HIV infection with left ventricular mass/hypertrophy. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 25:475–481.

- Baekken M, Os I, Sandvik L, et al. 2008. Hypertension in an urban HIV-positive population compared with the general population: influence of combination antiretroviral therapy. J Hypertens. 26:2126–2133.

- Manner IW, Baekken M, Oektedalen O, et al. 2012. Hypertension and antihypertensive treatment in HIV-infected individuals. A longitudinal cohort study. Blood Press. 21:311–319.

- Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. 2009. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 150:604–612.

- Okada K, Mikami T, Kaga S, et al. 2011. Early diastolic mitral annular velocity at the interventricular septal annulus correctly reflects left ventricular longitudinal myocardial relaxation. Eur J Echocardiogr. 12:917–923.

- Schwartz T, Sanner H, Gjesdal O, et al. 2014. In juvenile dermatomyositis, cardiac systolic dysfunction is present after long-term follow-up and is predicted by sustained early skin activity. Ann Rheum Dis. 73:1805–1810.

- Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. 2005. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 18:1440–1463.

- Schillaci G, Maggi P, Madeddu G, et al. 2013. Symmetric ambulatory arterial stiffness index and 24-h pulse pressure in HIV infection: results of a nationwide cross-sectional study. J Hypertens. 31:560–567. Discussion 7.

- Borkum M, Wearne N, Alfred A, et al. 2014. Ambulatory blood pressure profiles in a subset of HIV-positive patients pre and post antiretroviral therapy. CVJA. 25:153–157.

- De Socio GV, Bonfanti P, Martinelli C, et al. 2010. Negative influence of HIV infection on day-night blood pressure variability. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 55:356–360.

- Lederman MM, Calabrese L, Funderburg NT, et al. 2011. Immunologic failure despite suppressive antiretroviral therapy is related to activation and turnover of memory CD4 cells. J Infect Dis. 204:1217–1226.

- Neuhaus J, Jacobs DR Jr, Baker JV, et al. 2010. Markers of inflammation, coagulation, and renal function are elevated in adults with HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 201:1788–1795.

- Helleberg M, Kronborg G, Ullum H, et al. 2015. Course and clinical significance of CD8+ T-cell counts in a large cohort of HIV-infected individuals. J Infect Dis. 211:1726–1734.

- Cao W, Mehraj V, Kaufmann DE, et al. 2016. Elevation and persistence of CD8 T-cells in HIV infection: the Achilles heel in the ART era. J Int AIDS Soc. 19:20697

- Cao W, Mehraj V, Trottier B, et al. 2016. Early initiation rather than prolonged duration of antiretroviral therapy in hiv infection contributes to the normalization of CD8 T-Cell Counts. Clin Infect Dis. 62:250–257.

- Serrano-Villar S, Sainz T, Lee SA, et al. 2014. HIV-infected individuals with low CD4/CD8 ratio despite effective antiretroviral therapy exhibit altered T cell subsets, heightened CD8+ T cell activation, and increased risk of non-AIDS morbidity and mortality. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1004078.

- Serrano-Villar S, Perez-Elias MJ, Dronda F, et al. 2014. Increased risk of serious non-AIDS-related events in HIV-infected subjects on antiretroviral therapy associated with a low CD4/CD8 ratio. PLoS One. 9:e85798.

- Serrano-Villar S, Gutierrez C, Vallejo A, et al. 2013. The CD4/CD8 ratio in HIV-infected subjects is independently associated with T-cell activation despite long-term viral suppression. J Infect. 66:57–66.

- Appay V, Sauce D. 2008. Immune activation and inflammation in HIV-1 infection: causes and consequences. J Pathol. 214:231–241.

- Tsioufis C, Syrseloudis D, Dimitriadis K, et al. 2008. Disturbed circadian blood pressure rhythm and C-reactive protein in essential hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 22:501–508.

- von Kanel R, Jain S, Mills PJ, et al. 2004. Relation of nocturnal blood pressure dipping to cellular adhesion, inflammation and hemostasis. J Hypertens. 22:2087–2093.

- Erdogan D, Icli A, Aksoy F, et al. 2013. Relationships of different blood pressure categories to indices of inflammation and platelet activity in sustained hypertensive patients with uncontrolled office blood pressure. Chronobiol Int. 30:973–980.

- Duprez DA, Neuhaus J, Kuller LH, et al. 2012. Inflammation, coagulation and cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected individuals. PLoS One. 7:e44454.

- Seaberg EC, Benning L, Sharrett AR, et al. 2010. Association between human immunodeficiency virus infection and stiffness of the common carotid artery. Stroke. 41:2163–2170.

- Higashi Y, Nakagawa K, Kimura M, et al. 2002. Circadian variation of blood pressure and endothelial function in patients with essential hypertension: a comparison of dippers and non-dippers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 40:2039–2043.

- Maio R, Perticone M, Sciacqua A, et al. 2012. Oxidative stress impairs endothelial function in nondipper hypertensive patients. Cardiovasc Ther. 30:85–92.

- Jerrard-Dunne P, Mahmud A, Feely J. 2007. Circadian blood pressure variation: relationship between dipper status and measures of arterial stiffness. J Hypertens. 25:1233–1239.

- Manner I, Baekken M, Kvale D, et al. 2013. Markers of microbial translocation predict hypertension in HIV-infected individuals. HIV Med. 14:354–361.

- Staessen JA, Bieniaszewski L, O’Brien E, The “Ad Hoc’ Working Group, et al. 1997. Nocturnal blood pressure fall on ambulatory monitoring in a large international database. Hypertension. 29:30–39.

- Remick J, Georgiopoulou V, Marti C, et al. 2014. Heart failure in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and future research. Circulation. 129:1781–1789.

- Hsue PY, Hunt PW, Ho JE, et al. 2010. Impact of HIV infection on diastolic function and left ventricular mass. Circ Heart Fail. 3:132–139.

- Holloway CJ, Ntusi N, Suttie J, et al. 2013. Comprehensive cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy reveal a high burden of myocardial disease in HIV patients. Circulation. 128:814–822.

- Nayak G, Ferguson M, Tribble DR, et al. 2009. Cardiac diastolic dysfunction is prevalent in HIV-infected patients. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 23:231–238.

- Mondy KE, Gottdiener J, Overton ET, et al. 2011. High prevalence of echocardiographic abnormalities among hiv-infected persons in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 52:378–386.

- Frerichs FC, Dingemans KP, Brinkman K. 2002. Cardiomyopathy with mitochondrial damage associated with nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 347:1895–1896.

- Parati G, Stergiou G, O’Brien E, et al. 2014. European Society of Hypertension practice guidelines for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens. 32:1359–1366.