Abstract

Purpose: Childhood trauma in an important public health concern, and there is a need for brief and easily administered assessment tools. The Early Trauma Inventory (ETI) is one such instrument. The aim of this paper is to test the psychometric properties of the Swedish translation of the short, self-rated version (ETISR-SF), and to further validate the instrument.

Materials and Methods: In this cross-sectional study, 243 psychiatric patients from an open care unit in Sweden and 56 controls were recruited. Participants were interviewed and thereafter completed the ETISR-SF. Internal consistency was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed and goodness-of-fit was determined. Intra Class Correlation (ICC) was used to calculate test-retest reliability. Discriminant validity between groups was gauged using the Mann–Whitney U-test.

Results: Cronbach’s alpha varied between 0.55 and 0.76, with higher values in clinical samples than in controls. Of the four domains, general trauma showed a lower alpha than the other domains. The CFA confirmed the four-factor model previously seen and showed good to acceptable fit. The ICC value was 0.93, indicating good test–retest reliability. According to the Mann–Whitney U-test, the non-clinical sample differed significantly from the clinical sample, as did those with PTSD or borderline diagnosis from those without these diagnoses.

Conclusions: The Swedish translation of the ETISR-SF was found to have similar psychometric properties as both the original version and translations. ETISR-SF scores could also distinguish between different diagnostic groups associated with various degrees of trauma, which supports its discriminant validity.

Background and aims

Childhood trauma is an important public health concern because it is common and associated with a range of adverse psychiatric outcomes as well as somatic discomfort [Citation1]. Childhood trauma is associated with functional impairment [Citation2–5] and a lower quality of life [Citation6–9]. Perhaps this is due to depressive and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)-related symptoms [Citation10]. Early trauma is also associated with psychiatric morbidity, e.g. mood disorders [Citation11–13], attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [Citation14], substance abuse [Citation13] and psychosis [Citation15] in addition to PTSD, where experienced trauma is a part of the diagnostic criteria [Citation16]. Reported traumas are often categorized as either general trauma, sexual abuse, physical abuse or emotional neglect. However, those who report one type of trauma often report several other types [Citation17]. Experience of more trauma types is related to PTSD [Citation7,Citation18] and borderline personality disorder (BPD) [Citation19–22]. In regards to BPD, a causal relationship has been proposed [Citation23]. For some diagnoses, certain trauma types are very common, e.g. sexual abuse for BPD [Citation24] and some trauma types have been shown to be associated with symptom severity [Citation19,Citation25]. Therefore, the assessment of trauma type and total number of traumatic experiences are important in both researches as well as in clinical practice. However, assessing childhood trauma in adults is hampered by difficulties such as the accuracy of recall or the reluctance to report trauma in person because of the associated negative feelings, thus causing the validity of recalled trauma memories to come into question [Citation26–28]. Several interviewer-administered and self-report questionnaires have been developed to meet the need for valid and reliable tools for childhood trauma assessment. The psychometric properties for the majority of the instruments are acceptable (for review see Roy et al. or Pietrini et al. [Citation29, Citation30]). The Early Trauma Inventory (ETI) is one such instrument [Citation31].

Initially, ETI was created by Bremner et al. [Citation31] as a comprehensive expert-rated interview. A self-rated version (ETI-SR) was later developed and a briefer self-rated short form (ETISR-SF) was made after a psychometric analysis identified redundant items [Citation32]. Because it measures several different trauma domains as well as the age of onset, duration and frequency of traumatic events, perpetrator(s) and the emotional impact of the traumas, it could be a useful instrument in research as well as in specialized clinical settings.

The ETISR-SF has been shown to be a valid instrument for retrospective self-assessment of childhood trauma in diverse populations [Citation32–36] and has good test-retest-reliability [Citation34–36]. It has been translated with preserved psychometric properties to several cultural contexts and languages including: Spanish [Citation34], Korean [Citation35], Brazilian Portuguese [Citation36], Dutch [Citation37] and Chinese [Citation38]. However, to our knowledge, it has not yet been translated to or psychometrically tested in Swedish.

Aims

The aims of this study are to examine the psychometric properties of the Swedish translation of the ETISR-SF and further validate the instrument in two clinical samples of young psychiatric outpatients as well as in one sample of non-clinical controls.

Hypotheses to be tested are:

The Swedish version of the ETISR-SF will exhibit similar psychometric properties (internal consistency, factor structure) as previous translations and the original English version.

Test-retest-reliability of the Swedish version will be comparable with Spanish, Korean and Portuguese versions.

As an indication of discriminant validity, the ETISR-SF will be able to discriminate between non-clinical controls and psychiatric patients as well as patients with or without two diagnoses (PTSD and BPD) theoretically associated with trauma.

Materials and methods

Ethics

The study procedures are in accordance with ethical standards for human experimentation, and the study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala, Dnr 2008/171 (BBA), 2012/81 (2014-01-28), 2013/219 (2013-06-26) and 2012/81/3 (2015-11-20).

Participants

The ETISR-SF was validated in three different samples: two clinical and one non-clinical (see below).

BBA-sample; young patients with borderline personality disorder, bipolar disorder and/or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Patients were recruited from the Unit for Young Adults at the Department of General Psychiatry at the University Hospital in Uppsala, Sweden. All patients (n = 759) diagnosed between the 1st of May 2005 and the 31st of October 2010 with either Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), Bipolar Disorder (BP), ADHD or any combination of the three were identified from the administrative patient register and sent a study invitation by post. Two hundred and thirty patients (30.3%) agreed to participate and signed a written consent. Exclusion criteria were severe manic or psychotic symptoms during the interview. One patient was excluded because of mania. Eighty-six (37.4%) patients were excluded because they did not complete the necessary study measures, participate in the diagnostic interviews or had too much missing data in the ETI. Finally, 143 patients were eligible. Diagnostic characteristics for the study sample are presented in .

Table 1. Age, gender and diagnostic groups (current diagnosis only) in the three samples.

Each participant was interviewed by one of three medical doctors, all of whom had worked at the clinical unit where the patients were recruited. After a brief anamnestic interview, complementary semi-structured diagnostic interviews were performed for those patients whose diagnoses were not previously attained by diagnostic interviews. After the interviews, the participants filled in the ETI and were asked whether they would accept another self-assessment, which was then sent to them by mail on average 11.2 (SD =15.9) weeks later. Forty-two patients completed the ETI twice.

Uppsala Psychiatric Patients (UPP); young psychiatric patients from general psychiatry recruited at intake: Patients were recruited from the same unit as the BBA sample, but several years later. All new patients (n = 372) from the 14th of January to the 2nd of December 2013 were invited to participate. Among 151 participants, 100 (66.2%) had sufficient diagnostic and ETI data for this study. Subjects were diagnosed with a structured or semi-structured diagnostic interview (the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) or the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-Axis I Disorders, Clinical Version (SCID-I CV)) after an appointment wherein medical history was collected and a clinical evaluation was performed. Interviewers were trained psychiatrists, residents in psychiatry and trained clinical psychologists. Participants filled in the ETI on a separate occasion, shortly after the initial diagnostic evaluation.

Nonclinical control sample: The controls (n = 80) were recruited from university employees and students who were asked to participate in the same procedures and fill in the same questionnaires as the UPP-sample. However, the MINI interview was performed by telephone. Those who completed both the MINI and the ETISR-SF were eligible for this study (n = 56, 70.0 %).

Measures

Etisr-sf

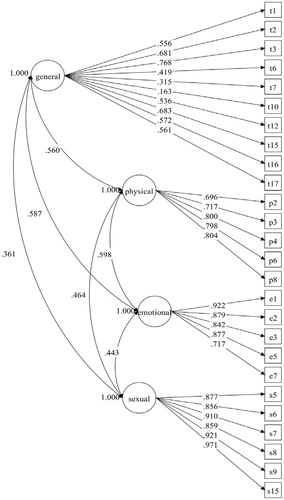

The ETISR-SF is designed to retrospectively measure trauma before the age of 18 and can be self-administered in about 15 min. It comprises 27 specific trauma-items organized in four domains: general trauma (11 items), physical abuse (5 items), emotional abuse (5 items) and sexual abuse (6 items), see . The domains are defined by Bremner et al. [Citation32].

Table 2. Frequency of endorsement, Cronbachs alpha minus item, item-total correlations.).

For each domain, except general trauma, there are follow-up questions on each trauma type regarding frequency, type of perpetrator and age of onset (ages 0–5, 6–12 and 13–18). All domains are concluded by Likert scale questions concerning to what extent the trauma affects the subject emotionally, at work or school as well as in social relationships.

Different methods of scoring ETI have been discussed [Citation31, Citation32]. Simply counting the number of traumatic events was shown by Bremner et al. [Citation32] to be as valid as other more complicated scoring algorithms and is, therefore, also used in this study

The ETI was translated from its original English version with permission from J. D. Bremner. It was first translated by a doctoral student and then back-translated by an independent native-English translator. The back-translated inventory was very similar to the original version. To verify semantic equivalence, the original translated and back-translated versions of the inventory were compared and discussed by the research group, wherein all had good knowledge of the English and Swedish languages, resulting in a few minor corrections. After the first 52 participants in the BBA sample had filled in the questionnaire, minor graphical changes were made in order to make the inventory clearer and easier to rate. The first version had similar internal consistency as the second version (Cronbach’s alpha =0.741 for the first version and 0.732 for the second). Therefore, they are not analyzed separately below.

Scid-I cv

SCID-I CV [Citation39] was used for diagnosing axis I disorders in the BBA-sample. The reliability of SCID-I CV has generally been shown to be good [Citation40–42]. SCID-I has demonstrated superior validity over standard clinical interviews [Citation43, Citation44].

Scid-ii

SCID-II (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-Axis II Disorders) was used to diagnose personality disorders [Citation45] in the BBA-sample. SCID-II has demonstrated good reliability in most studies [Citation46–48].

K-sads

The ADHD/ADD-module from the K-SADS (Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Present and Lifetime Version) [Citation49], originally designed for children between six and 17 years of age, was used to diagnose ADHD/ADD/HDD in the BBA-sample. K-SADS has good reliability [Citation49].

Mini

MINI [Citation50] is a widely used structured diagnostic interview for several common mental disorders, developed for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The validity and reliability have been shown to be good [Citation51, Citation52].

Statistical methods

SPSS version 21 was used for all statistical analyses, except for factor analysis, wherein MPLUS version 7 was used. Internal consistency was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha [Citation53]. As in most previous psychometric studies [Citation35, Citation36], a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed in order to examine the translated version of the ETI as to whether it fits a four-factor model (an exploratory factor analysis has previously been made by Bremner et al. [Citation32]). All three groups were pooled for the analysis, and standardized loadings were used using variance-adjusted weighted least square (WLSMV) estimator. To determine goodness-of-fit, Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) and comparative fit index (CFI) were used. RMSEA-values range from 0 to 1, with lower values indicating a better fit, and values ≤0.06 indicating an acceptable model fit. TLI and CFI-values range from 0-1, with higher values indicating better fit. Values larger than 0.9 indicate acceptable fit and >0.95 indicate good fit [Citation54]. One item from the general domain (‘Seeing someone murdered’) was excluded from the factor analysis since no participant endorsed this. Intra Class Correlation (ICC) was used to calculate test-retest reliability. Discriminant validity was gauged by calculating the ETI’s ability to distinguish between patients with and without known or probable traumatic history (PTSD or borderline diagnosis) from the other patients in the BBA group. Since there were too few participants with PTSD diagnosis in the other groups, this was performed solely in the BBA group. To further examine discriminant validity, patients and controls were also compared. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used since the ETI total score (number of traumas endorsed) was not clearly normally distributed, and the size of the compared groups differed considerably.

Results

Descriptives

Descriptive ETISR-SF data are presented in . ETISR-SF domain and total scores are presented in .

Table 3. ETI score.

Internal consistency

Cronbach’s alpha, as a measure of internal consistency, varied among the three study groups (). Overall, the control group showed lower α:s, both on the four domains (α = 0.143–0.692) as well as on the total ETI score (α = 0.552) as compared to the clinical groups (α = 0.557–0.840 for the different domains, α = 0.736–0.760 for the whole instrument). Also, the general trauma domain exhibited a lower α in all study groups.

Table 4. Cronbach alpha.

Factor analysis

The CFA confirmed that a four-factor model showed adequate fit, with RMSEA = 0.055, TLI = 0.891 and CFI = 0.92. Overall, the items in the general trauma domain showed a poorer loading towards the general trauma factor (0.163–0.768 with only one item >0.7) compared to items in the other domains, where all items showed strong loadings towards their factors - all but one item (0.696) > 0.7 and several >0.9. See for more details on factor loadings. The covariance between the different factors was <0.60 (0.361–0.598).

CFA of a second order model, performed by Osorio et al. [Citation36], was also tested but did not improve the goodness-of-fit and exhibited similar values (RMSEA = 0.054, TLI = 0.895, CFI = 0.905).

Test-retest reliability

Test-retest reliability was assessed for some participants in the BBA group (n = 42). The ICC-values were 0.93 for the global scale, 0.81 for general trauma, 0.86 for physical abuse, 0.92 for emotional abuse and 0.91 for sexual abuse.

Discriminant validity

According to the Mann–Whitney U-test, the non-clinical sample differed significantly from the two clinical samples in respect to ETI total scores (z = −6.796, p ≤ .001).

When compared within the BBA sample, the total ETI scores of patients with PTSD diagnosis significantly differed from the rest of the subjects in the sample who had lower scores (z = −3.938, p ≤ .001). The same was true for those with BPD diagnoses compared to those without (z = −3.030, p < .002).

Conclusion

The Swedish translation of the ETISR-SF was found to have similar psychometric properties as both the original version and the translations, with similar factor structure and internal consistency in this study. ETISR-SF results could also distinguish different diagnostic groups associated with various degrees of trauma, which supports its discriminant validity.

The Swedish translation showed high internal consistency for the two clinical samples, comparable to previous research [Citation32–34, Citation36, Citation37]. As in preceding studies, the Cronbach’s α for general trauma was somewhat lower. As previously hypothesized, an explanation for this could be that the general subscale measures a broader range of heterogeneous traumatic events, ranging from natural disasters to mental health problems within the family and, thus, this subscale is more heterogeneous and does not measure a single construct [Citation34].

The non-clinical sample had markedly lower internal consistency (0.55 compared to 0.74-0.76 for the total score), especially in the general (0.14 compared to 0.56-0.62) and sexual (0.49 compared to 0.84) domains. The control group generally had experienced fewer traumas, thus resulting in lower internal consistency. Some items that no participant endorsed (such as seeing someone murdered) could also have affected the internal consistency negatively for all subgroups. The non-clinical controls, however, had a higher number of unendorsed items (one in the physical abuse subscale and three in the sexual abuse subscale), which, as well as the controls being a smaller group, could further explain the relatively lower internal consistency.

The CFA supported the four-factor structure previously suggested. The three different fit indices exhibited good (RMSEA) to acceptable (CFI, TLI) fit. This was comparable, although slightly weaker than in preceding studies [Citation35, Citation36]. The fact that the items in the general domain exhibited considerably weaker correlations to the latent general trauma factor could also indicate that the items in that domain do not represent one homogeneous factor (which is supported by exploratory factor analysis in previous research [Citation32]).

Test-retest reliability for the Swedish translation was good on all subscales as well as total ETI score. It was also comparable with previous translations [Citation34–36]. The original English version of the self-rated version has not as yet been tested with ICC values; however, Bremner et al. [Citation31] showed that the interview version had good test-retest reliability. As for internal consistency, the general trauma domain had a somewhat lower ICC score (0.81 compared to 0.86-0.92).

The Swedish version of the ETISR-SF was able to discriminate between groups with different expected levels of traumatization. This supports the ETI’s validity and is also in line with previous research, wherein ETI was able to discriminate patients with known associations with trauma from comparison subjects [Citation32].

As measured by the ETI, the mean value of experienced trauma in a non-clinical Swedish population is 2.7, compared to healthy subjects in a Korean (2.3) [Citation35] and US population (3.5) [Citation32]. The fact that Swedish subjects have experienced slightly fewer traumas has also been observed in previous research [Citation55].

From a participant’s perspective, some had concerns about the length of the instrument as well as the questions where the trauma categories could be rated as having had a positive impact on emotional well-being and functioning. They perceived this as a very unlikely and almost offensive option. A solution to both these problems could possibly be to develop an even shorter version of the ETI, which would only measure the number of different traumas and not any additional information. The information obtained would, of course, not be as comprehensive, but since a number of traumas is the most widely used measurement in the articles we have read, it would probably be sufficient for at least some situations where the ETI is used.

The more general problem with recall bias concerning recollection of childhood trauma has been previously discussed in many articles [Citation26–28]. However, it’s difficult to see other realistic and more reliable ways to measure childhood trauma other than the patient’s own recalled memories. Another weakness of the present study is the homogeneity of the clinical samples. The participants were all young and came from one clinic in one town in Sweden. This limits the generalizability of the results.

The strengths of this study include a well-diagnosed and diagnostically heterogeneous study population as well as the inclusion of a non-clinical study group. To our knowledge, this is the first time a Swedish translation of the ETISR-SF has been tested.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the patients who chose to participate as well as to J. D. Bremner for the permission to translate the ETI. Thanks to statistician Hans Arinell, and to Ann-Charlotte Fält and Lena Knutsson-Medin for help with the administrative work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Park S, Hong JP, Bae JN, et al. Impact of childhood exposure to psychological trauma on the risk of psychiatric disorders and somatic discomfort: single vs. multiple types of psychological trauma. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219:443–449.

- Davidson G, Shannon C, Mulholland C, et al. A longitudinal study of the effects of childhood trauma on symptoms and functioning of people with severe mental health problems. J Trauma Dissoc. 2009;10:57–68.

- Gil A, Gama CS, de Jesus DR, et al. The association of child abuse and neglect with adult disability in schizophrenia and the prominent role of physical neglect. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33:618–624.

- Sansone RA, Dakroub H, Pole M, et al. Childhood trauma and employment disability. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2005;35:395–404.

- Peleikis DE, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. Current mental health in women with childhood sexual abuse who had outpatient psychotherapy. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20:260–267.

- Troeman ZC, Spies G, Cherner M, et al. Impact of childhood trauma on functionality and quality of life in HIV-infected women. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:84.

- Agorastos A, Pittman JO, Angkaw AC, et al. The cumulative effect of different childhood trauma types on self-reported symptoms of adult male depression and PTSD, substance abuse and health-related quality of life in a large active-duty military cohort. J Psychiatric Res. 2014;58:46–54.

- Seiler A, Kohler S, Ruf-Leuschner M, et al. Adverse childhood experiences, mental health, and quality of life of chilean girls placed in foster care: an exploratory study. Psychol Trauma. 20158:180–187.

- Skarupski KA, Parisi JM, Thorpe R, et al. The association of adverse childhood experiences with mid-life depressive symptoms and quality of life among incarcerated males: exploring multiple mediation. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20:605–612.

- Aversa LH, Lemmer J, Nunnink S, et al. Impact of childhood maltreatment on physical health-related quality of life in U.S. active duty military personnel and combat veterans. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38:1382–1388.

- Weiss EL, Longhurst JG, Mazure CM. Childhood sexual abuse as a risk factor for depression in women: psychosocial and neurobiological correlates. AJP. 1999;156:816–828.

- Widom CS, DuMont K, Czaja SJ. A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:49–56.

- McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, et al. Clinical characteristics of women with a history of childhood abuse: unhealed wounds. JAMA. 1997;277:1362–1368.

- Rucklidge JJ, Brown DL, Crawford S, et al. Retrospective reports of childhood trauma in adults with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2006;9:631–641.

- Read J, Os J, Morrison AP, et al. Childhood trauma, psychosis and schizophrenia: a literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112:330–350.

- Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Sesar K, Simic N, Barisic M. Multi-type childhood abuse, strategies of coping, and psychological adaptations in young adults. Croat Med J. 2010;51:406–416.

- Frissa S, Hatch SL, Gazard B, et al. Trauma and current symptoms of PTSD in a South East London community. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48:1199–1209.

- Martin-Blanco A, Soler J, Villalta L, et al. Exploring the interaction between childhood maltreatment and temperamental traits on the severity of borderline personality disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2014;55:311–318.

- Widom CS, Czaja SJ, Paris J. A prospective investigation of borderline personality disorder in abused and neglected children followed up into adulthood. J Personal Disorders. 2009;23:433–446.

- Brown GR, Anderson B. Psychiatric morbidity in adult inpatients with childhood histories of sexual and physical abuse. AJP. 1991;148:55–61.

- Herman JL, Perry JC, van der Kolk BA. Childhood trauma in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146:490–495.

- Ball JS, Links PS. Borderline personality disorder and childhood trauma: evidence for a causal relationship. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11:63–68.

- Zanarini MC, Williams AA, Lewis RE, et al. Reported pathological childhood experiences associated with the development of borderline personality disorder. AJP. 1997;154:1101–1106.

- Kuo JR, Khoury JE, Metcalfe R, et al. An examination of the relationship between childhood emotional abuse and borderline personality disorder features: the role of difficulties with emotion regulation. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;39:147–155.

- Chu JA, Frey LM, Ganzel BL, et al. Memories of childhood abuse: dissociation, amnesia, and corroboration. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:749–755.

- Williams LM. Recall of childhood trauma: a prospective study of women's memories of child sexual abuse. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:1167–1176.

- Loftus EF, Garry M, Feldman J. Forgetting sexual trauma: what does it mean when 38% forget? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:1177–1181.

- Pietrini F, Lelli L, Verardi A, et al. Retrospective assessment of childhood trauma: review of the instruments. Riv Psichiatr. 2010;45:7–16.

- Roy CA, Perry JC. Instruments for the assessment of childhood trauma in adults. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192:343–351.

- Bremner JD, Vermetten E, Mazure CM. Development and preliminary psychometric properties of an instrument for the measurement of childhood trauma: the Early Trauma Inventory. Depress Anxiety. 2000;12:1–12.

- Bremner JD, Bolus R, Mayer EA. Psychometric properties of the early trauma inventory-self report. J Nervous Mental Dis. 2007;195:211–218.

- Hyman SM, Garcia M, Kemp K, et al. A gender specific psychometric analysis of the early trauma inventory short form in cocaine dependent adults. Addictive Behav. 2005;30:847–852.

- Plaza A, Torres A, Martin-Santos R, et al. Validation and test-retest reliability of Early Trauma Inventory in Spanish postpartum women. J Nervous Mental Dis. 2011;199:280–285.

- Jeon JR, Lee EH, Lee SW, et al. The early trauma inventory self report-short form: psychometric properties of the korean version. Psychiatry Investig. 2012;9:229–235.

- Osorio FL, Salum GA, Donadon MF, et al. Psychometrics properties of early trauma inventory self report - short form (ETISR-SR) for the Brazilian context. PloS One. 2013;8:e76337.

- Rademaker AR, Vermetten E, Geuze E, et al. Self-reported early trauma as a predictor of adult personality: a study in a military sample. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64:863–875.

- Wang Z, Du J, Sun H, et al. Patterns of childhood trauma and psychological distress among injecting heroin users in China. PloS One. 2010;5:e15882.

- First MB, RL, Spitzer, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Clinical Version, (SCID-CV). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1996.

- Skre I, Onstad S, Torgersen S, et al. High interrater reliability for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Axis I (SCID-I). Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991;84:167–173.

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR. Attainment and maintenance of reliability of axis I and II disorders over the course of a longitudinal study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2001;42:369–374.

- Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Bender D, et al. The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study: reliability of axis i and ii diagnoses. J Personality Disord. 2000;14:291–299.

- Ramirez Basco M, Bostic JQ. Methods to improve diagnostic accuracy in a community mental health setting. AJP. 2000;157:1599–1605.

- Kranzler HR, Kadden RM, Babor TF, et al. Validity of the SCID in substance abuse patients. Addiction. 1996;91:859–868.

- First MB, RL, Spitzer, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders, (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1997.

- Arntz A, Beijsterveldt B, Hoekstra R, et al. The interrater reliability of a Dutch version of the structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R personality disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1992;85:394–400.

- Maffei C, Fossati A, Agostoni I, et al. Interrater reliability and internal consistency of the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders (SCID-II), version 2.0. J Personal Disord. 1997;11:279–284.

- Lobbestael J, Leurgans M, Arntz A. Inter-rater reliability of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID I) and Axis II Disorders (SCID II). Clin Psychol Psychother. 2011;18:75–79.

- Ambrosini PJ. Historical development and present status of the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children (K-SADS). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:49–58.

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatr. 1998;59 (Suppl 20):22–33.

- Amorim P, Lecrubier Y, Weiller E, et al. DSM-IH-R Psychotic Disorders: procedural validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). Concordance and causes for discordance with the CIDI. Eur Psychiatr. 1998;13:26–34.

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Harnett Sheehan K, et al. The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. Eur Psychiatry J Assoc Eur Psychiatr. 1997;12:232–241.

- Cronbach L. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334.

- Hu LB, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6:1–55.

- Gerdner A, Allgulander C. Psychometric properties of the Swedish version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF). Nordic J Psychiatry. 2009;63:160–170.