Abstract

Introduction: Recently, schizotypal personality traits were measured in a multinational sample recruited from 14 countries, however no Scandinavian cohort was included. The aim of this study was, therefore, to measure schizotypal personality traits in Swedish-speaking populations, with and without psychiatric disorders, and to investigate the psychometric properties of the Swedish version of the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire-Brief (SPQ-B).

Methods: The SPQ-B results from 50 psychiatric patients were compared to controls (n = 202). An additional sample of 25 controls completed the full SPQ twice and we calculated test-retest reliability for SPQ and SPQ-B. We estimated the internal consistency for SPQ-B and SPQ-B factors with omega. We compared the results of SPQ-B (M and SD) in patient and control groups to corresponding results worldwide.

Results: We found similarity between our SPQ-B scores and those from other published samples. SPQ-B showed good internal consistency and acceptable test-retest correlations. The results indicate that the Swedish version of the instrument is valid and can differentiate psychiatric cohorts from non-psychiatric controls.

Conclusion: The Swedish version of the SPQ-B exhibit good psychometric properties and is useful for assessing schizotypal traits in clinical and non-clinical populations.

1. Introduction

The term schizotypy has been referred to as a personality organization construct that indicates latent psychosis liability, and risk for psychosis-spectrum disorders [Citation1]. The phenotypic manifestations of schizotypy range from its fully compensated form, with almost no pathological signs or symptoms at all, to schizotypal traits, and to its fully uncompensated form, which is schizophrenia. Alternatively, the construct of schizotypal personality disorder (SPD) corresponds to observable aggregated signs and symptoms resulting in a disorder [Citation1,Citation2]. The construct of schizotypal personality disorder, originally added to the third edition of DSM is essentially unchanged in DSM-5. It is defined by a pervasive pattern of social and interpersonal deficits along with other features of schizotypy, i.e. ideas of reference, odd beliefs, unusual perceptual experiences, odd speech and thinking, suspiciousness and paranoid ideation, inappropriate or constricted affect, odd or eccentric behavior, lack of close friends, and excessive social anxiety [Citation3]. ICD- and DSM-classifications differ, in that schizotypal disorder is categorized as a personality disorder in DSM, but not in the ICD classification. It is, however, in ICD as well as in DSM, considered a schizophrenia spectrum disorder [Citation4].

In community studies, reported rates of Schizotypal personality disorder range between 0.6 and 4.6% [Citation3]. It is determined by both cultural and genetic components, thus it is more prevalent among first-degree family members of individuals with schizophrenia, than among other populations [Citation3]. In consequence, schizotypal personality traits could be viewed as an indirect measure for psychosis proneness (prediction of psychosis in high-risk patients). However, schizotypal personality disorder is also overrepresented in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [Citation5] and in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) [Citation6,Citation7]. The overlap between schizotypal personality traits and autistic symptoms is considerable [Citation8]. Moreover, these traits are associated with poor treatment response in OCD [Citation9], and with severe dissociative experiences in individuals with borderline personality disorder [Citation10]. Subsequently, valid instruments for assessment of schizotypal traits are warranted. In the Nordic countries, the use of standardized assessments in public mental health services is well accepted [Citation11], however, a Swedish screening tool for assessing schizotypal traits is still lacking.

The Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire (SPQ), modeled on the DSM diagnostic criteria for Schizotypal personality disorder [Citation12], is a widely used 74 item self-report with solid psychometric properties [Citation13–16]. SPQ includes nine subscales, each representing the schizotypal traits that define Schizotypal personality disorder [Citation13].

The 22-item Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire-Brief (SPQ-B) [Citation17], is an abbreviated version of the SPQ scale. It is designed to screen for schizotypal personality traits prior to a confirmatory clinical interview and to identify these traits in the general population. Recently, schizotypal personality traits were assessed with SPQ-B in a large multinational sample recruited from 14 countries [Citation18]; however, no Scandinavian cohort was included.

The aims of this study are to test the psychometric properties of the SPQ-B, translated into Swedish, and to compare the level of schizotypal traits in a Swedish-speaking population to those reported from other countries. We hypothesized that the rates would be similar to those reported from other European countries.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Instrument

The SPQ and SPQ-B consist of questions and statements, with the response alternatives yes (=1 point) and no (=0 points). The total SPQ score subsequently ranges from 0 to 74, and the SPQ-B from 0 to 22. Most confirmatory factor analysis of the SPQ and SPQ-B subscales specify three main factors, namely Cognitive-Perceptual deficits, Interpersonal deficits and Disorganized/Oddness [Citation13,Citation18–20]. A bifactor model with three first-order factors plus a general factor of schizotypal personality was also presented [Citation18]. Measurement invariance testing of SPQ-B with confirmatory factor analysis showed configural invariance across samples from different countries, although invariance in the sense of equivalence of factor loadings or intercepts could not be established [Citation18].

SPQ-B was originally published in English [Citation17] and is translated into Spanish, Italian, Chinese, Arabic, French, Creole, Greek and German [Citation18]. A senior psychiatrist (SB) and a bilingual psychologist (Stephanie Plenty, Ph.D.) translated SPQ into Swedish, and a professional translator back translated it (available in Supplementary material).

2.2. Participants completing the SPQ

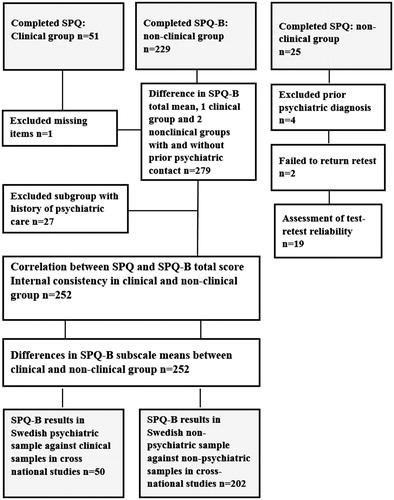

A diagnostically heterogeneous sample of 51 Swedish-speaking psychiatric patients, (mean age 33.0 ± 13.1, range 16–64 years) was administered the full 74-item SPQ, as part of two separate research projects [Citation21,Citation22]. Inclusion criteria for the Manouilenko study were being a patient at a specialized psychiatric care unit for at least one year. Exclusion criteria were current or past neurological disorders, epilepsy, a history of brain damage, hearing impairment, intellectual disability, or inability to attend mainstream school. In addition, ongoing illicit substance abuse was excluded by means of urinary drug screening. Inclusion criteria in the Hesselmark study were to have a psychiatric disorder requiring specialist care, age below 40 years and Swedish speaking. No exclusion criteria were applied. Details of the procedures are described in these original publications. In brief, the included patients had been diagnosed according to DSM-IV prior to our assessments. Diagnoses were thereafter confirmed by senior psychiatrists in a 3–5 h long clinical interview, including the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview [Citation23] and several validated diagnosis-specific questionnaires (e.g. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale [Citation24], the semi-structured Diagnostic Interview for adult ADHD [Citation25] and the Ritvo Autism Asperger’s Diagnostic Scale-Revised [Citation26,Citation27]). Twelve patients had a lifetime diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorder (SSD), whereas 38 patients, diagnosed with ASD, OCD, and ADHD, had never experienced a psychosis (). Exclusion criteria in this study was above 20% missing items. One patient was excluded due to too many missing items and eleven of the remaining patients had missing data with a mean of 2.73 missing items in the full SPQ, ranging from one to five items per patient.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants and differences between samples, n = 252.

2.3. Non-psychiatric control groups

The non-clinical sample consisted of a total of 229 participants (men = 24; women = 189, missing data n = 16) with a mean age of 45.3 ± 11.7 years (range 20–75, missing data n = 6). They were included from two different sources: a subgroup of 11 individuals, initially recruited from the community as a part of the aforementioned larger research project [Citation21] had filled out the full SPQ. All other non-clinical participants were professionals attending a course on mental health in Hudiksvall, Sweden (n = 143) or Mariehamn, Finland (n = 75) and they filled out the SPQ-B anonymously. Inclusion criteria for the non-clinical sample were age 18 years or above, and full understanding of the Swedish language. The only exclusion criterion was 20% or more, missing items on the SPQ-B. Thirteen of the participants had missing items, with a mean of 1.46 per person (range, 1–3).

Apart from responding to the SPQ-B items and provide information on gender and age, these participants were asked whether they had sought psychiatric care or ever been diagnosed with a psychiatric illness. Twenty-seven individuals reported a history of psychiatric problems, they were included in an analysis of the total SPQ-B score as a separate comparison group and thereafter excluded from further analyses (see flowchart, ).

An additional community sample of 25 individuals were administered the full SPQ (web-questionnaire) for a test-retest analysis. They were asked to fill in gender, age, and whether they had sought psychiatric care or ever been diagnosed with a psychiatric illness, which resulted in exclusion of four individuals. Another two individuals failed to submit a retest after having received two written reminders. SPQ-B scores from 19 participants were subsequently used in the test-retest analysis ().

2.4. Statistics

Imputation was performed by replacing missing data points with the mean for each individual’s completed items. Missing items were assigned to 0 if the completed item mean was ≤0.5 and to 1 if it was ≥0.51. Sixty-one individuals (patients n = 50, non-psychiatric controls n = 11) and the test-retest sample (n = 19) completed the full SPQ. The SPQ-B scores were then derived from their SPQ results. Omega coefficients were used to estimate internal consistency to facilitate comparison with international research [Citation18]. Pearson correlations were calculated between SPQ and SPQ-B scores, for test-retest correlation and for correlation between age and SPQ-B results. Mean duration between test and retest was 31.1 days (range, 17–49). Effects of gender on SPQ-B results were examined with t-tests on patients and controls separately. We analyzed total SPQ-B-total differences between patients, non-psychiatric controls and the 27 controls with a reported psychiatric history using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to evaluate differences in SPQ-B subscale means (the 27 controls with psychiatric history were removed). The effect sizes of mean differences were assessed. We ran all analyses in IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 22.0. The Regional ethic review board in Stockholm approved the study (2012/395-31/4, 2014/551-31/2, and 2018/1975-32).

3. Results

3.1. Reliability measures

The correlation between the full SPQ and SPQ-B total score was 0.96 (n = 61). Omega coefficients for SPQ-B total in the psychiatric group (n = 50) and the non-psychiatric group (n = 202) were good (0.88 and 0.80). Omega coefficients for the SPQ-B factors were lower, albeit higher for the psychiatric group than for the controls (perceptual cognitive (0.81; 0.64), interpersonal (0.78; 0.67) and disorganized (0.73; 0.59). The test-retest correlations for SPQ and SPQ-B were 0.90 (p<.001) and 0.62 (p<.001), respectively.

3.2. Difference in SPQ-B total between psychiatric patients, and non-clinical controls with and without a history of psychiatric illness

There was a significant difference in SPQ-B total score between the three groups of patients n = 50 (M = 9.30 ± 5.52), the 27 controls with a reported history of psychiatric illness (M = 7.33 ± 4.50) and those without a history of psychiatric illness n = 202 (M = 5.24 ± 3.89), [F (2, 279)=19.09, p<.001)], η2 = 0.122. Post hoc tests with Bonferroni correction revealed that patients scored significantly higher on the SPQ-B than the controls (p<.001). However, the subgroup with a history of psychiatric illness did not score significantly lower than the patients (p=.17). Moreover, they showed a trend towards a higher score compared to the controls without a history of psychiatric illness (p=.054).

3.3. Comparison of SPQ-B subscales between psychiatric patients and controls without a history of psychiatric illness

The one-way MANOVA analysis on the SPQ-B subscales showed a significant difference between the clinical and non-clinical group, F (3,248) = 19.64, p < .001; Pillai’s Trace = 0.192, η2 = 0.192. Pairwise comparisons showed that Interpersonal deficits and Disorganized/Oddness subscales were significantly different between samples (p < .001, η2 = 0.139 and 0.143, respectively, but the difference in the Cognitive-Perceptual deficits subscale was non-significant p = .062 (). Gender and age did not affect the SPQ-B scores in neither group.

3.4. Comparisons of the Swedish speaking samples SPQ-B results to cross-national studies

For comparisons of our results with previous research on SPQ-B on psychiatric and non-psychiatric groups, across nations and languages, see .

Table 2. SPQ-B total and factor scores in psychiatric and non-psychiatric samples.

4. Discussion

This study, using the SPQ-B for assessing schizotypal personality traits, is to our knowledge the first study that includes patients with psychosis, other psychiatric diagnoses, and non-clinical controls. SPQ-B has been validated across 14 nations, but previously not in a Scandinavian setting. The aims of the study were to investigate the psychometric properties of the Swedish SPQ-B and to measure the degree of schizotypal personality traits in Swedish-speaking populations. We found that the Swedish SPQ-B yielded similar scores as those reported by other researchers examining community samples and clinical groups.

In the studies by Moreno-Izco [Citation28] and Axelrod [Citation19], psychiatric patients were assessed with the SPQ-B. Moreno-Izco included 32 patients with SSD, whereas Axelrod investigated 237 adolescents without psychotic disorders. Our psychiatric group scored intermediately between the Moreno-Izco and Axelrod samples, supporting the validity of our findings. Our non-psychiatric group scored within the normal range on SPQ-B, when compared to other community populations worldwide [Citation18]. Interestingly SPQ-B scores vary considerably across nations, ranging between a mean of 4.5 in Germany and 9.3 in Tunisia. Swedish speaking individuals fit in-between with a mean score of 5.24.

4.1. Limitations

The small psychiatric sample and the fact that we did not explore the diagnostic criteria for schizotypal personality disorder are limitations in this study. On the other hand, each patient was carefully assessed face-to-face by senior psychiatrists for several hours, reflecting gold standard for diagnostic work-up. Our psychiatric group scored 80% above the non-psychiatric group, which shows that the groups are clearly separable, although scores overlap. A third limitation is our control group, composed of a convenient sample attending a course on mental health. However, by using this sample we had almost no missing data; participants agreed to fill out the SPQ-B anonymously on the lecturer’s request. A fourth limitation is the fact that the SPQ-B items were extracted from the original full version of the SPQ in the patient group and the test-retest sample. Further, we could not conduct test on invariance between samples due to the small patient sample. Lastly, possible effects of social desirability influence on scores was not assessed, but as most of the participants filled out the SPQ-B anonymously, this should not affect the results.

5. Conclusion

The Swedish version of the SPQ-B exhibit good psychometric properties and is useful for assessing schizotypal traits in clinical and non-clinical populations.

Biography

Susanne Bejerot is professor of psychiatry at Örebro University and researcher in the field of clinical psychiatry. Johan Wallén is a medical doctor and wrote a paper on SPQ during his graduation studies in medicine at Örebro University. Irina Manouilenko is PhD and a senior psychiatrist, presently working in private practice. At the time of the study she worked with patients with psychosis in Stockholm. Eva Hesselmark is PhD and trained in psychology and assessed adult patients with OCD or psychosis. She is currently working at an OCD unit in Stockholm.Marie Elwin is PhD and a licensed psychologist with extensive experience in personality assessments in Region Örebro county.

Contributions

Susanne Bejerot, Eva Hesselmark and Irina Manouilenko assessed the patients and the collected data. Marie Elwin and Susanne Bejerot designed the study. They drafted the initial manuscript with Johan Wallén who also collected data on healthy controls. The co-authors gave final approval to the submitted manuscript.

SPQ_B_supplementary1.docx

Download MS Word (13.2 KB)SPQ_supplementary_file_.doc

Download MS Word (152.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Lenzenweger MF. Schizotypy, schizotypic psychopathology and schizophrenia. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(1):25–26.

- Lenzenweger MF. Schizotaxia, schizotypy, and schizophrenia: Paul E. Meehl’s blueprint for the experimental psychopathology and genetics of schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115(2):195–200.

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- Tyrer P, Reed GM, Crawford MJ. Classification, assessment, prevalence, and effect of personality disorder. Lancet. 2015;385(9969):717–726.

- Barneveld PS, Pieterse J, de Sonneville L, et al. Overlap of autistic and schizotypal traits in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Schizophr Res. 2011;126(1–3):231–236.

- Stanley MA, Turner SM, Borden JW. Schizotypal features in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 1990;31(6):511–518.

- Brakoulias V, Starcevic V, Berle D, et al. The clinical characteristics of obsessive compulsive disorder associated with high levels of schizotypy. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2014;48(9):852–860.

- Bejerot S. An autistic dimension: a proposed subtype of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Autism. 2007;11(2):101–110.

- Moritz S, Fricke S, Jacobsen D, et al. Positive schizotypal symptoms predict treatment outcome in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42(2):217–227.

- Rodriguez-Delgado A, et al. Comorbid personality disorders and their impact on severe dissociative experiences in Mexican patients with borderline personality disorder. Nord J Psychiatry. 2019;73(8):509–514.

- Bjaastad JF, Jensen-Doss A, Moltu C, et al. Attitudes toward standardized assessment tools and their use among clinicians in a public mental health service. Nord J Psychiatry. 2019;73(7):387–396.

- Raine A. The SPQ: a scale for the assessment of schizotypal personality based on DSM-III-R criteria. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17(4):555–564.

- Raine A, Reynolds C, Lencz T, et al. Cognitive-perceptual, interpersonal, and disorganized features of schizotypal personality. Schizophr Bull. 1994;20(1):191–201.

- Fossati A, Raine A, Carretta I, et al. The three-factor model of schizotypal personality: invariance across age and gender. Pers Individ Diff. 2003;35(5):1007–1019.

- Fonseca-Pedrero E, Fumero A, Paino M, et al. Schizotypal personality questionnaire: new sources of validity evidence in college students. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219(1):214–220.

- Fonseca-Pedrero E, Debbané M, Ortuño-Sierra J, et al. The structure of schizotypal personality traits: a cross-national study. Psychol Med. 2018;48(3):451–462.

- Raine A, Benishay D. The SBQ-B: A brief screening instrument for schizotypal personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 1995;9(4):346–355.

- Fonseca-Pedrero E, Ortuño-Sierra J, Lucas-Molina B, et al. Brief assessment of schizotypal traits: a multinational study. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:182–191.

- Axelrod SR, Grilo CM, Sanislow C, et al. Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire-Brief: factor structure and convergent validity in inpatient adolescents. J Pers Disord. 2001;15(2):168–179.

- Ladea M, Szoke A, Bran M, et al. Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire-Brief: Effect of invalid responding on factor structure analysis and scores of schizotypy. Encephale. 2020;46(1):7–12.

- Manouilenko I, Humble MB, Georgieva J, et al. Brainstem auditory evoked potentials for diagnosing autism spectrum disorder, ADHD and schizophrenia spectrum disorders in adults. A blinded study. Psychiatry Res. 2017;257:21–26.

- Hesselmark E, Bejerot S. Clinical features of paediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome: findings from a case–control study. BJPsych Open. 2019;5(2):e25.

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubler Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33; quiz 34–57.

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276.

- Ramos-Quiroga JA, Nasillo V, Richarte V, et al. Criteria and concurrent validity of DIVA 2.0: a semi-structured diagnostic interview for adult ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2016;23(10):1126–1135.

- Ritvo RA, Ritvo ER, Guthrie D, et al. A scale to assist the diagnosis of autism and Asperger’s disorder in adults (RAADS): a pilot study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38(2):213–223.

- Andersen LMJ, Näswall K, Manouilenko I, et al. The Swedish version of the Ritvo autism and asperger diagnostic scale: revised (RAADS-R). A validation study of a rating scale for adults. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(12):1635–1645.

- Moreno-Izco L, Sánchez-Torres AM, Lorente-Omeñaca R, et al. Ten-year stability of self-reported schizotypal personality features in patients with psychosis and their healthy siblings. Psychiatry Res. 2015;227(2–3):283–289.