Abstract

Background: The mortality of forensic psychiatric (FP) patients compared to non-forensic psychiatric (non-FP) patients has been sparsely examined.

Methods: We conducted a matched cohort study and compared Danish male FP patients (n = 490) who underwent pre-trial forensic psychiatric assessment (FPA) 1980–1992 and were subsequently sentenced to psychiatric treatment with matched (on year of birth, marital status, and municipality of residence) male non-FP patients (n = 490) and male general population controls (n = 1716). FP and non-FP patients were also matched on major psychiatric diagnostic categories. To determine mortality and identify potential predictors of mortality, we linked nationwide register data (demographics, education, employment, psychiatric admission pattern and diagnoses, cause of death) to study cohorts. Average follow-up time was 19 years from FPA assessment/sampling until death/censoring or 31 December 2010 and risk factors were studied/controlled with Cox proportional hazard analysis.

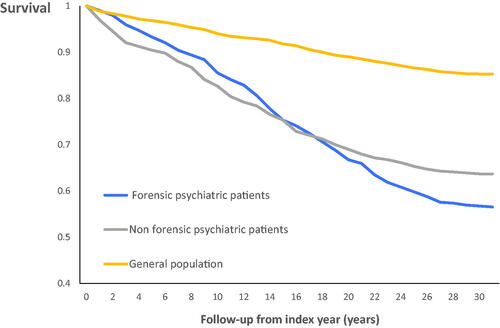

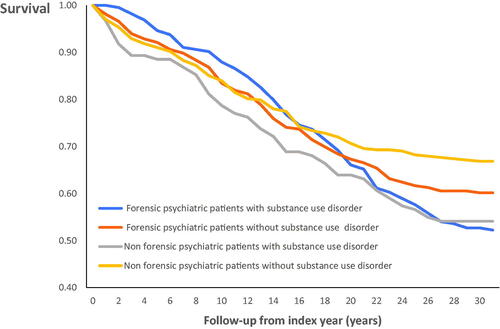

Results: Overall, psychiatric patients had significantly higher mortality compared to matched general population controls (medium to large effects). Among patients, 44% (213) of FP vs. 36% (178) of matched non-FP patients died during follow-up (p = 0.02). When we used Cox regression modeling to control for potential risk factors; age, education, immigrant background, employed/studying at index, length of psychiatric inpatient stay/year, and ever being diagnosed with substance use disorder (SUD), FP patient status was no longer significantly associated with increased mortality, whereas SUD and longer inpatient time per year were independently associated with increased mortality.

Discussion: This study suggests that SUD and longer inpatient time per year are independent risk factors for increased mortality in psychiatric patients.

Background

The mortality of forensic psychiatric (FP) patients has been sparsely described. A recent systematic review on mortality among patients discharged from secure hospitals found eight publications with 2226 subjects, of which 225 deceased during follow-up. The pooled all-cause crude death rate for FP patients was high with 1538 (95% CI: 1175-1901) per 100,000 person-years, ranging from 789 to 2828 across studies. Due to insufficient information in the original studies, the review did not report an overall standardized mortality ratio (SMR) comparing the mortality of FP patients with general population subjects [Citation1].

In addition, even less is known about FP patient mortality compared to that among non-forensic psychiatric (non-FP) patients. This comparison is quite relevant as FP patients are often characterized by well-established risk factors for increased mortality [Citation2] such as low education, unstable employment and concomitant substance abuse [Citation3–5].

On the contrary, FP services generally provide treatment with longer inpatient stays [Citation6], higher staffing and closer outpatient monitoring compared to general psychiatry; all of which might decrease mortality [Citation7]. However, when examining the association between lengths-of-stay and FP patient mortality, Fazel et al. [Citation8] did not find that longer length of psychiatric inpatient stay were linked to decreased mortality once age, sex, diagnosis, index offence and secondary substance use disorder (SUD) were controlled for. Finally, it has been proposed that increased FP patient mortality might be associated with the concurrent mental illness component of being in secure care rather than the forensic context per se [Citation9].

In many European countries, the numbers of FP beds have been increasing since 1990, indicating an increase in the number of FP patients [Citation10]. In Denmark the number of FP patients rose substantially from 1445 in 2001 to 4393 in 2014 [Citation11].

To reduce the excess mortality among this growing subgroup of psychiatric patients, we need a clearer understanding of mortality patterns and associated risk factors.

We hypothesized that FP patient status as such (vs. being a non-FP patient) would no longer be significantly related to overall mortality once we controlled for likely risk factors; age, education, employment, immigrant background, ever being diagnosed with SUD, and length-of-stay in psychiatric hospital.

Method

Danish legislation concerning forensic psychiatry

The Administration of Justice Act states that a pre-trial forensic psychiatric assessment (FPA) must be performed when this might affect the ruling of the court; i.e. when the defendant might have a mental disorder, or the alleged criminal act is of a certain nature or severity. FPAs are performed by independent, general psychiatrists in approved centers, in collaboration with psychologists and social workers. The concepts “not guilty by reason of insanity” and “unfit to stand trial” are not used in Danish legislation, as mentally ill and mentally healthy offenders are tried identically [Citation12].

The Code of Penal Law §16 states; “Persons, who, at the time of the act, were irresponsible owing to mental illness or similar conditions are not punishable”. The legal term “mental illness” is essentially equivalent to the clinical term psychosis; thus, offenders with psychosis/similar conditions are imposed with a treatment order and referral to a psychiatric facility. According to the Code of Penal Law §69, non-psychotic mentally ill offenders may be sentenced to a psychiatric treatment order, if this is considered as more expedient than a sentence to punishment in order to prevent reoffending [Citation13].

There are three main types of treatment orders (Penal Law §68): type 1 is initiated in a psychiatric outpatient clinic and followed by inpatient treatment if necessary, type 2 is initiated as inpatient treatment in a psychiatric hospital while type 3 is a direct placement order in a psychiatric hospital. Hence, treatment orders types 1 and 2 are rather similar since both may include inpatient care if needed. Whereas those sentenced to treatment (types 1 and 2) can be discharged from hospital by the responsible consultant psychiatrist, those sentenced to placement (type 3) can be discharged only by the prosecutor or court.

Cohort sampling, characteristics and follow-up

The FP patients were drawn from a larger cohort; the Danish PAK-study [Citation14]. Initially, we ran a full Cox regression model including men and 34 individually matched female FP patients (data not shown). Although the results were generally quite similar with or without women, the low number of females rendered the statistical model unstable. Hence, analyses presented here are based on cohorts comprising only male subjects.

Between 1 January 1980 and 31 December 1992, 1667 male subjects underwent a pretrial FPA at the Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Aarhus University Hospital or the Clinic of Forensic Psychiatry, Ministry of Justice in Copenhagen. The 1667 subjects are estimated to constitute 85% of those who underwent FPA in Denmark during the same period.

Among the 1667 subjects, 1553 could be identified in Statistics Denmark registers and of these 573 subjects received a sentence to treatment.

The index cohort of 573 male FP patients was linked to Danish nationwide, population registers through the personal identification number assigned to each Danish citizen. Although our principal aim was to compare mortality rates and risk factors between FP and non-FP patients, we included mortality data for the general male population to improve comparability with prior reports. Hence, we created two matched cohorts: one with male non-FP patients (1:1) and a second with general population individuals (1:4).

Subjects in the two comparison cohorts; non-FP patients and general population subjects were individually matched to FP patients on age, marital status, and municipality of residence at the time of index FPA. Further, FP and non-FP patients were also matched on main ICD-10 diagnostic categories (F1, F2 etc.) at the date of the FP patient’s index FPA. Complete individual matching (1:1) of FP patients was possible with 490 male non-FP patients.

For the general population cohort, we identified 1960 individually matched men (1:4); exclusion of those convicted or receiving psychiatric inpatient treatment during follow-up yielded a final sample of 1716 male general population subjects.

After matching, the mean subject age in all 3 cohorts was 33 years (SD = 12 years) and 14% were married. In the two psychiatric patient cohorts (FP and non-FP) 63% had a primary diagnosis of a major psychiatric disorder (ICD-10: F2 [schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders] or F3 [mood, including bipolar, disorders]), 19% a personality disorder (ICD-10: F6), and 18% another disorder as primary diagnosis (ICD 10: F0, F1, F4, F5, F8, F9).

All three cohorts were followed from the time of the index FPA of the FP patient to death or emigration (when censored) or to December 31, 2010. The mean follow-up time for FP patients was 19.4 years (SD = 7.4), 18.9 years (SD = 8.3) for non-FP patients and 19.6 years (SD = 8.3) for matched male general population subjects.

Risk factors

We identified four risk factors for premature death in prior research; highest completed education, employed/studying at the time of index (i.e. the FPA), average psychiatric inpatient time/year of follow-up and ever being diagnosed with SUD in the Psychiatric Patient Register (PPR). Data were collected from five longitudinal, nationwide Danish registers; the PPR, the Central Person Register (CPR), and the Population Education, Employment, and Death Registers. We drew data on immigrant background (immigrant vs. not) from the CPR.

The PPR contains information on discharge diagnoses and length-of-stay for all inpatients in low (general psychiatry), medium and high security psychiatric hospitals [Citation15]. The clinical discharge diagnosis was assigned according to ICD-8 from 1977 to 1993, and from 1994 according to the ICD-10 (Denmark never implemented ICD-9). Hence, ICD-8 diagnoses were translated into their corresponding ICD-10 entities [Citation16]. For reasons of generalizability, we excluded <5 eligible patients admitted to the only high security FP hospital in Denmark; Sikringsafdelingen in Slagelse.

Subjects ever being diagnosed with a principal or concomitant SUD in the PPR (ICD-8 codes: 291, 303 and 304. For ICD-10: F1) were coded as having SUD.

The CPR contains data on immigrant background, current marital status, and address. CPR defines immigrant background as; not being Danish citizen and both parents neither born in Denmark nor being Danish citizens.

The Population Education Register supplied data on individuals’ highest level of completed education. Education data were missing for 11% (57/490) of FP patients, and 7% (36/490) of non-FP patients. We dichotomized education obtained at index into having completed 9 years or less of primary education vs. completed more than 9 years education [Citation17].

The Employment Register (ER) contains continuously updated information on present employment. ER data were missing for 0.4% (2/490) of FP patients and 1% (5/490) of non-FP patients. We dichotomized employment into employed (included being a registered student) or not at the FPA of each index FP patient.

The Death Register holds ICD codes on cause-specific deaths based on physician-completed death certificates. Importantly, a 2002 change in coding practice did not impact overall registration and resulting mortality rates (dead/alive) [Citation18].

Statistical analysis

We applied chi-square tests for comparisons with categorical variables (proportions), t-tests for normally distributed continuous variables (means), and the Mann-Whitney U-test with (non-parametrically distributed) continuous variables (means), and calculated Kaplan-Meier survival curves to illustrate the timing of mortality. We also calculated crude mortality rates; the number of deaths divided by person-years at risk. Significance level of 0.05 is used and p-value two-tailed test reported. We used Cox proportional hazards regression modeling to determine the association between risk factors and mortality [Citation19].

The model includes the explanatory variables; being an FP patient, being unemployed/not studying at index FPA, ever diagnosed with SUD in the PPR and length of psychiatric inpatient stay/year. We also controlled for age and immigrant background (adjusted hazard ratios not reported).

Sensitivity analyses were used to evaluate risk factors and test for time dependency. Due to variable mortality rates over time an Accelerated Failure Time model could have been used [Citation20]. However, we chose a Cox proportional hazards regression model since it is more widely used and results easier to communicate and compare. Testing the same explanatory variables in complementary ATF model suggested mainly similar results (data not shown). All calculations were performed with SAS version 9.4 computer software.

Ethics

The Regional Research Ethics Committee stated that the original PAK cohort study did not need formal ethical approval. This study was approved as part of the PAK study by the Legal Office at the Denmark’s Central Region (file number 1-16-02-530-18) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (file number 2002-41-2073).

Results

Descriptive cohort data

suggests that subjects with immigrant background were evenly distributed among FP and non-FP patients (9% vs. 10%), as opposed to 18% among general population controls. In contrast, FP patients had less education and were less often employed/studying compared to non-FP patients. FP patients were also admitted to inpatient psychiatric care on average 13 days longer yearly than non-FP patients during follow-up (mean 23.9 months, SD 38.6 vs. mean 10.6 months, SD 20.2).

Table 1. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline, inpatient time, and mortality among 490 male forensic psychiatric patients and 490 matched male non-forensic psychiatric patients in Denmark followed 1980–2010.

Overall mortality

During follow-up, 44% (n = 213) of FP patients died compared to 36% (n = 178) of non-FP patients (p = 0.02) ( and ) and 15% (n = 253) of matched general population men. The all-cause mortality rate per 100,000 person-years at risk was 2240 for FP patients, 1920 for non-FP patients and 750 for general population males.

Cause-specific mortality

No significant overall difference was found in cause-specific mortality across 8 categories (neoplasms, circulatory diseases, digestive system diseases, nervous diseases, accidents, suicide, homicide and other diseases/unknown) when comparing mortality causes for FP and non-FP patients (p = 0.36). Specifically, similar elevated proportions of FP patients (27%) and non-FP patients (31%) died from unnatural causes (suicide, accidents, homicide) compared to 9% of the general population subjects.

Independent risk factors

The multivariable Cox proportional hazard model () suggested that being a FP vs. a non-FP patient was no longer an independent risk factor for premature death when controlling for other measured covariates and neither was being unemployed/not studying at the index time of the FPA. In contrast, ever being diagnosed with SUD in the PPR and having longer average inpatient admissions per year during follow-up were independently associated with increased mortality ().

Table 2. Multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression model of risk factors for overall mortality among 490 male forensic and 490 matched non-forensic psychiatric patients in Denmark, followed 1980–2010.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves stratified by substance use disorder

Among 224 FP patients ever diagnosed with SUD, 47% (106/224) deceased compared to 46% (56/122) similarly diagnosed non-FP patients (p = 0.74). Conversely, 40% (107/266) of FP patients without SUD diagnoses died compared to 33% (122/368) of non-FP patients without SUD (p = 0.08). After 20 years of follow-up, FP and non-FP patients diagnosed with SUD exhibited nearly identical survival curves ().

Discussion

We conducted a matched cohort study of men sentenced to FP treatment in Denmark 1980–1992 and compared them to matched male non-FP psychiatric patients and general population controls. Mortality rates, patterns and risk factors were studied, and three potentially meaningful findings are suggested.

First, while rates of mortality rates among forensic patients were high in absolute terms (a mortality rate of 44% in FP patients vs. 36% in non-FP patients and 15% in general population controls), the higher crude all-cause mortality initially seen in FP vs. non-FP psychiatric patients no longer remained when controlling for potential confounders overrepresented in FP subjects. In contrast, ever being diagnosed with SUD in the Danish Psychiatric Register persisted as a moderately strong independent risk factor for premature death. Second, longer periods of inpatient treatment during follow-up were associated with increased mortality. Third, cause-specific mortality rates of death from unnatural causes did not differ between FP and non-FP patients.

Crude mortality rates

The present crude mortality rate for male FP-patients of 2240 deaths per 100,000 person-years is slightly higher than the 1916 deaths (men and women) per 100,000 person-years found in a Swedish study on FP patient mortality [Citation8]. The Swedish health care system is comparable to the Danish in many respects; both are comprehensive, publicly funded with equal access and low “out of pocket” spending on healthcare. However, the Swedish population has a healthier lifestyle compared to the Danes [Citation21]. The higher crude mortality rate among Danish FP patients might reflect overall national mortality patterns [Citation22]; as Danish psychiatric patients and general population alike have increased mortality compared to their Swedish counterparts [Citation23,Citation24]. The lower mortality rate reported in Swedish data could also, at least partly, result from the inclusion of 11% females in the Swedish FP study sample (vs. our exclusively male FP cohort); women in both Denmark and Sweden generally have higher life expectancy as compared to men. Further, the proportion of severely mentally ill patients, with the highest mortality, was considerably lower in the Swedish study compared to our cohort (42.5% vs. 63%). Finally, the lower rate in the Swedish study might be due to immortal time bias. That is, Swedish subjects entered the cohort when discharged from FP inpatient treatment, whereas subjects in the present study did so at the time of the FPA and received psychiatric treatment afterwards.

Our general population sample was matched with the FP cohort on factors associated with increased mortality; hence, only 14% were married. Being single and male is associated with increased mortality, which might explain the 15% mortality rate among our general population cohort [Citation25].

Offending and mortality

Our data suggest that the association between being an FP vs. a non-FP patient and increased mortality may be spurious. That is, possibly associated to underlying, confounding factors related to both offender status and mortality; represented by lack of employment/study interest or ability, SUD and longer inpatient length-of-stay. Likewise, mentally healthy offenders do not necessarily have increased mortality when compared to non-offending comparison subjects from similar social backgrounds [Citation26]. It has also been put forward that FP patients have mortality rates similar to those of patients with predominantly schizophrenia-spectrum disorder, suggesting that it is the mental illness component of being in secure care that contributes to the increased mortality risk rather than the forensic setting itself [Citation1].

Substance use disorder and mortality

The detrimental effects of substance abuse on health and mortality population-wise has been extensively documented [Citation27]. Further, SUDs have been identified as the psychiatric disorders that cause the largest reduction in remaining life expectancy among subjects with mental disorders [Citation28]. Specifically, a substantial body of research has found (some forms of) substance abuse to be a risk factor both for being classified as a FP patient and violent reoffending among psychiatric patients [Citation29,Citation30]. Substance properties, amounts, abuse contexts and persistence may also interact to initiate or aggravate mental illness, increase impulsivity or risky behavior, and reduce treatment efficacy. Deaths from unnatural causes have been found to be significantly higher among FP patients with SUD compared to FP patients without SUD. Despite the importance of diagnosing (and treating) SUD, recent data indicate suboptimal recognition of SUD, which may ultimately lead to lack of treatment [Citation31]. Altogether, these issues identify SUD as a major modifiable treatment target as SUD impacts several health outcomes. However, the possible effect of psychosocial interventions against SUD on mortality in psychiatric patients remains uncertain [Citation32], whereas restrictions to alcohol availability and marketing may be highly cost-effective measures for gaining healthy life-years [Citation33].

Longer length of stay and mortality

Patients with schizophrenia suffer excessive morbidity and mortality compared to the general population and subjects diagnosed with other psychiatric disorders [Citation34]. They also constitute a majority of long-stay psychiatric inpatients [Citation6]. Most patients in our clinical cohorts (FP and non-FP) indeed suffered from a psychotic disorder, which might explain our finding that longer admission time was associated with increased mortality, as longer length of stay is a likely proxy for mental illness severity. In other words, our finding that longer length of stay increased mortality should not be interpreted to indicate that treatment as such increases mortality, but may rather reflect additional risk (seldom systematically measured) in those admitted more often, including disorder severity, medication non-adherence and SUD. Again, our findings , support previous research in that it may be the mental illness that contributes to increased mortality rather than the FP context in itself [Citation9].

Limitations and strengths

The present male FP patient cohort includes a representative absolute majority of those who underwent FPA and subsequently received a sentence to FP treatment in Denmark 1980–1992. Hence, although not formally a nation-wide sample, we have no reasons to believe that our FP cohort suffers from substantial selection biases. FP patient data included both inpatients and outpatients admitted to low (general psychiatry) or medium secure psychiatric settings and linked register data were from longitudinal national, high quality sources. Further, since high security unit patients are characterized by longer stays and severe mental illness, associated with higher mortality, our inclusion of high security patients might have amplified the association between length of stay and mortality.

Our definition of SUD was rather inclusive; patients admitted once with an acute intoxication, for example, would be diagnosed with SUD. A less inclusive SUD definition would probably have strengthened the association between SUD and increased mortality, albeit at the expense of lowered statistical power.

The present findings based on male cohorts should only be generalized to female FP patients with substantial caution; as FP females differ from FP males regarding diagnostic profiles, age at first offence and offence types [Citation35]. Further, criminally violent women may have a higher likelihood of being declared medico-legally insane compared to men [Citation36]. Finally, the association between SUD and mortality among FP patients has been shown to differ across sex, as FP males with SUD had a significantly higher mortality compared to those without SUD, but this association could not be found among women [Citation31].

Due to cohort effects, our results concerning FP patient mortality might not be fully generalizable to cohorts selected more recently. The mortality gap between people with severe mental illness and the general population has increased over the last decades, possibly caused by an increased mortality rate of the former [Citation37].

Compared to previous studies on mortality of FP patients, the strengths of this study are the large cohort of FP patients, the matched control groups of non-FP patients and general population sample, the prolonged follow-up, the carefully selected risk factors and the high-quality data from national registers.

Implications

Inpatient admission involves a variety of intervention components; pharmacological and other medical treatment, social and psychological support, including coordination of professional and private social networks etc. Inpatient settings should lower the use of alcohol and illicit drugs, provide adequate antipsychotic and other medications, healthier eating and other health-promotive opportunities, relevanttreatment for somatic illness , and relative protection from most unnatural causes-of-death. All these aspects have been mentioned as instrumental in reducing mortality among psychiatric patients. Evidently, more controlled intervention studies are needed to elucidate which specific components of FP care that may have the greatest impact on mortality and other adverse outcomes [Citation38]. Kennedy and others have emphasized the need to secure evidence-based treatment-as-usual and consistent models of care. Further advances require attention at both national and international levels; which might be achieved by creating a network of forensic psychiatry centers of excellence [Citation39].

Author contributions

Data were collected and paired with register-based information within thePAK-study (English: Study of Mentally Disordered Offenders) designed by SB and JL. SB and JL collected data for PAK. For the current study, LU further developed the study protocol, selected risk factors, and drafted the manuscript. JL, SB and NL were involved in study conception and analytic strategy whereas MI performed data analyses. LU, MI, SB, JL and NL all provided important intellectual input on study design and contributed substantially to the interpretation of findings and manuscript revision.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Department of Forensic Psychiatry,, Aarhus University Hospital Psychiatry Denmark and to theMinistry of Justice’s Clinic of Forensic Psychiatry, Copenhagen, Denmark for permission to conduct the PAK study. We also thank Dr. Aksel Bertelsen, editor of the Danish version of ICD-10, for translating ICD-8 diagnoses into their ICD-10 counterparts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflicts of interest were reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lisbeth Uhrskov Sørensen

Niklas Långström, MD, PhD, trained as a psychiatrist in child and adolescent psychiatry and forensic psychiatry. He is currently associate professor at Karolinska Institutet (KI) in Stockholm, Sweden, headed the Center for Violence Prevention at KI from 2006 to 2013 and was professor of psychiatric epidemiology at KI 2010–2016. Niklas Långström conducts research on mental illness, risk factors for violent and sexual crime and preventive treatments.

Susanne Bengtson

Susanne Bengtson, MSc, PhD, was employed as a researcher at the Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Aarhus University Hospital Psychiatry for a number of years. She is currently senior researcher at the Sexological Clinic, Psychiatric Center Copenhagen, Denmark.

Michael Ibsen

Michael Høffding Ibsen received a Master of Arts and Economics from the University of Aarhus in 1997.Since 2012, he is senior analyst and partner at i2minds, an independent scientific research company in Aarhus, Denmark. i2minds performs data management and statistical analyses for research projects and has many years of experience in register-based research. Primary research areas are health economics, forensic psychiatry and labour economics.

Niklas Långström

Lisbeth Uhrskov Sørensen, MD, PhD. She also holds a Master of Science in Health Policy and Planning from London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and London School of Economics and Political Science. She is senior consultant and research leader at the Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Aarhus University Hospital Psychiatry and associate professor at Aarhus University, Faculty of Health.

References

- Fazel S, Fimińska Z, Cocks C, et al. Patient outcomes following discharge from secure psychiatric hospitals: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(1):17–25.

- Penney SR, Seto MC, Crocker AG, et al. Changing characteristics of forensic psychiatric patients in Ontario: a population-based study from 1987 to 2012. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019;54(5):627–638.

- Bronnum-Hansen H, Baadsgaard M. Widening social inequality in life expectancy in Denmark. A register-based study on social composition and mortality trends for the Danish population. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:994.

- Roelfs DJ, Shor E, Davidson KW, et al. Losing life and livelihood: a systematic review and meta-analysis of unemployment and all-cause mortality. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(6):840–854.

- Charlson FJ, Baxter AJ, Dua T, et al. Excess mortality from mental, neurological and substance use disorders in the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2015;24(2):121–140.

- Sharma A, Dunn W, O’Toole C, et al. The virtual institution: cross-sectional length of stay in general adult and forensic psychiatry beds. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2015;9(1):25.

- Durcan G, Hoare T, Cumming I. Unlocking pathways to secure mental health care. Report. Centre for Mental Health; London. 2011.

- Fazel S, Wolf A, Fimińska Z, et al. Mortality, rehospitalisation and violent crime in forensic psychiatric patients discharged from hospital: rates and risk factors. PloS One. 2016;11(5):e0155906.

- Ojansuu I, Putkonen H, Tiihonen J. Cause-specific mortality in Finnish forensic psychiatric patients. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72(5):374–379.

- Chow WS, Priebe S. How has the extent of institutional mental healthcare changed in Western Europe? Analysis of data since 1990. BMJ Open. 2016;6(4):e010188.

- Kortlaegning af retspsykiatrien: Mulige årsager til udviklingen i antallet af retspsykiatriske patienter samt viden om indsatser for denne gruppe. (Possible causes for the development in the number of forensic psychiatric patients and the knowledge concerning interventions for this group). Copenhagen: Sundheds-og Ældreministeriet (Ministry of Health and Elderly); 2015.

- Administration of Justice Act. (c.75) Online Copenhagen: The Ministry of Justice. Accessed March 23rd 2020. Available from: https://www.retsinformation.dk/Forms/R0710.aspx?id=209542

- Code of Penal Law (c.3) and (c.9) Online Copenhagen: The Ministry of Justice. Accessed March 23rd 2020. Available from: https://www.retsinformation.dk/Forms/R0710.aspx?id=209398#id1684713c-faf1-45ff-b1b7-4ee52e12198d

- Bengtson S, Lund J, Ibsen M, et al. Long-term violent reoffending following forensic psychiatric treatment: comparing forensic psychiatric examinees and general offender controls. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10(715).

- Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB. The Danish psychiatric central research register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):54–57.

- WHO. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: conversion tables between ICD-8, ICD-9 and ICD-10, Revision 1. World Health Organization, Health DoM; Geneva. 1994.

- Jensen VM, Rasmussen AW. Danish education registers. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):91–94.

- Helweg-Larsen K. The Danish register of causes of death. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):26–29.

- Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J Royal Statis Soc Series B (Methodological). 1972;34(2):187–220.

- Wei LJ. The accelerated failure time model: a useful alternative to the Cox regression model in survival analysis. Statist Med. 1992;11(14–15):1871–1879.

- Christensen K, Davidsen M, Juel K, et al. The divergent life-expectancy trends in Denmark and Sweden - and some potential explanations. In: Crimmins EM, Preston SH, Cohen B, editors. International differences in mortality at older ages: Dimensions and sources. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2010. p. 385–408.

- Rose G. The strategy of preventive medicine. Oxford University Press; Oxford. 1995.

- Nordentoft M, Wahlbeck K, Hällgren J, et al. Excess mortality, causes of death and life expectancy in 270,770 patients with recent onset of mental disorders in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. PloS One. 2013;8(1):e55176.

- Wahlbeck K, Westman J, Nordentoft M, et al. Outcomes of Nordic mental health systems: life expectancy of patients with mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(6):453–458.

- Berntsen KN. Trends in total and cause-specific mortality by marital status among elderly Norwegian men and women. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):537.

- van de Weijer S, Bijleveld C, Huschek D. Offending and mortality. Adv Life Course Res. 2016;28:91–99.

- Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1575–1586.

- Plana-Ripoll O, Pedersen CB, Agerbo E, et al. A comprehensive analysis of mortality-related health metrics associated with mental disorders: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Lancet. 2019;394(10211):1827–1835.

- Fazel S, Långström N, Hjern A, et al. Schizophrenia, substance abuse, and violent crime. JAMA. 2009;301(19):2016–2023.

- Vevera J, Svarc J, Grohmannova K, et al. An increase in substance misuse rather than other mental disorders has led to increased forensic treatment rates in the Czech Republic. Eur Psychiatr. 2009;24(6):380–387.

- Ojansuu I, Putkonen H, Lahteenvuo M, et al. Substance abuse and excessive mortality among forensic psychiatric patients: a Finnish nationwide cohort study. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:678.

- Baxter AJ, Harris MG, Khatib Y, et al. Reducing excess mortality due to chronic disease in people with severe mental illness: meta-review of health interventions. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(4):322–329.

- Chisholm D, Moro D, Bertram M, et al. Are the “best buys” for alcohol control still valid? An update on the comparative cost-effectiveness of alcohol control strategies at the global level. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2018;79(4):514–522.

- Schoepf D, Uppal H, Potluri R, et al. Physical comorbidity and its relevance on mortality in schizophrenia: a naturalistic 12-year follow-up in general hospital admissions. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;264(1):3–28.

- de Vogel V, de Spa E. Gender differences in violent offending: results from a multicentre comparison study in Dutch forensic psychiatry. Psychol, Crime & Law. 2018;25(7):739-751.

- Yourstone J, Lindholm T, Grann M, et al. Gender differences in diagnoses of mentally disordered offenders. Int J Foren Mental Health. 2009;8(3):172–177.

- Lomholt LH, Andersen DV, Sejrsgaard-Jacobsen C, et al. Mortality rate trends in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: a nationwide study with 20 years of follow-up. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2019;7(1):6.

- Vollm BA, Clarke M, Herrando VT, et al. European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on forensic psychiatry: evidence based assessment and treatment of mentally disordered offenders. Eur Psychiatr. 2018;51:58–73.

- Kennedy HG, Simpson A, Haque Q. Perspective on excellence in forensic mental health services: what we can learn from oncology and other medical services. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10(733).