Abstract

Background

Patients with personality disorders (PDs) often have insecure attachment patterns and may be especially vulnerable to abrupt treatment changes. Patients with borderline PD (BPD) are often considered vulnerable to treatment interruption due to chronic fear of abandonment. Nonetheless, other PDs are poorly investigated. In the first Covid-19 wave in Norway, in-person treatment facilities and group treatments were strongly restricted from March 12th until May/June 2020.

Objectives

To examine and compare changes in outpatient treatment for patients with avoidant (AvPD) and BPD during the first Covid-19 wave in Norway, and patients’ reactions to these changes.

Methods

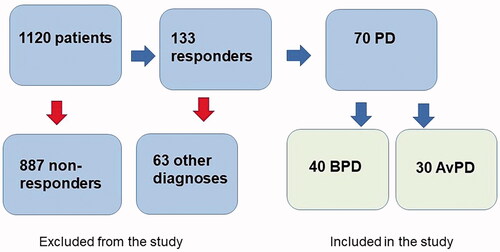

The study is based on a cross-sectional survey distributed to 1120 patients referred to 12 different PD treatment units on a specialist mental health service level within the Norwegian Network for Personality Disorders. The survey included questions on treatment situation, immediate reactions, and changes during the crisis. From 133 responders (response rate 12%), 40 patients reported BPD and 30 AvPD as diagnosis.

Results

All patients were followed up from their therapist after March 12th. Almost all patients in both groups expressed satisfaction under the new circumstances. Both groups experienced the same regularity as before, but more AvPD patients reported less than weekly consultations. AvPD patients reported more negative feelings about changes in therapy, and missed the therapy and group members more than the BPD group.

Conclusion

After the lockdown, BPD patients received a closer follow-up than AvPD patients, and the latter reported more negative feelings related to change in their treatment situation.

Introduction

Background

Mental health problems during the Covid-19 pandemic

Mental health problems related to consequences of the Covid-19 crisis have been broadly described, both in the general population as well in clinical populations [Citation1–3]. Studies refer to more depression, anxiety and an increase of symptoms in different diagnostic groups. Personality disorders (PDs) represent severe and prevalent conditions and at an early time point in the pandemic, Preti et al. [Citation4] specifically outlined possible reactions and differences between PDs. Concern has also been raised about how Covid-19 restrictions affected the delivery of mental health services [Citation5–6]. Avoidant (AvPD) and borderline personality disorder (BPD) are the two most frequent PDs within treatment seeking patient samples [Citation7], and the two conditions often have contrastingly different clinical characteristics and social strategies [Citation8–9]. Nonetheless, to our knowledge, no study has specifically studied and compared AvPD and BPD patients during the Covid-19 crises, nor investigated their reactions to the Covid-19 inflicted changes, their experience of treatment availability, contact and format.

Therapy lockdown experiences

In Norway, the Covid-19 pandemic and societal lockdown lead to a dramatic restriction of regular outpatient consultations and group treatments within hospitals and mental health services. The official lockdown date was March 12th 2020. Physical admittance to mental health services was for some time largely limited. Telephone consultations represented a dominating alternative contact form as more technical solutions such as video consultations took longer time to implement [Citation10]. From late May and during summer 2020, it was possible to resume more regular outpatient sessions within health services.

In Norway, a large proportion of PD patients are treated within the Network for Personality Disorders (Network), which is a clinical research collaboration involving treatment units within specialist mental health [Citation11]. Before the pandemic patients in the Network received a combination of group therapies and individual therapy, in which different approaches like mentalization-based therapy, psychodynamic therapy, schema therapy and metacognitive interpersonal therapy. This was abruptly discontinued after March 12th.

In response to the pandemic, many mental health services have tried to adapt by means of telepsychiatry [Citation12–14]. However, replacements for advanced therapy programs for PD patients, may be complicated to find. There are several obstacles to conduct individual psychotherapy [Citation12] as well as group therapy online [Citation15]. The most common – and often only – services offered in this situation have been telephone and video consultations. A handful of studies have described this transition, both with success and complications. With continued contact through telephone and e-mail, BPD treatments based on dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) and schema focused therapy (SFT) have been described with positive effects [Citation16–19]. An Australian study specified characteristics of effective online interventions for adolescents with PDs [Citation14], including specific focus on self-harm, suicidality, interpersonal difficulties, emotion regulation difficulties, and other features of PDs. In London, Bateman and his colleagues have by clinical vignettes described how to use mentalization by remote therapy with BPD patients [Citation19]. While several have outlined principles, practices, and effects of treatment for BPD, we have presently not found studies including AvPD patients and their treatment situation during the pandemic.

Reactions to therapy lockdown

Only a few studies have described patients’ reactions to changes in therapy format, and AVPD or BPD are not specifically highlighted. An Austrian study showed that clients perceived therapeutic interventions differently by remote therapies than with in-person therapy [Citation20]. In South-East of England, a therapy program for eating disorders (N = 7) was successfully able to continue through a combination of online individual and group consultations and e-mails [Citation13], although participants also described challenges with this format.

Objectives

This study is based on a survey administered to patients enrolled in specialized PD treatments in Norway [Citation21]. Former recent studies based on the same survey have described considerable vulnerability of patients with PD during the Covid-19 lock down, including both mental distress and their treatment situation [Citation10,Citation21]. The current study aimed to examine and compare patients with AvPD and BPD, and specifically focuses on: (1) treatment received in the two different PD patient groups after March 12th and (2) patients' self-reported emotional reactions to the change from an ordinary in-person group/individual therapy to alternative therapy formats.

The hypotheses we propose for this study are: (a) both patient groups were equally offered alternative therapies shortly after lockdown. (b) Digital solutions took more time to establish for both groups. (c) Both patient groups were equally troubled by the change in therapy format and expressed negative feelings toward this change.

Methods

Study design/setting

The current study is based on an anonymous, cross-sectional survey performed in June–October 2020. The survey was developed in a multidisciplinary work group with researchers, clinicians, and users in the Network [Citation21].

Participants

All patients invited to the survey had been admitted to one of 12 PD treatment units within the Network before March 12th. The treatments are designed for patients with PDs and relevant personality problems, and patients with psychosis, bipolar disorders and developmental disorders are normally not admitted. As a cross-sectional study, the recruited responders represented different phases of treatment or pretreatment initial assessment. The 12 treatment units participated by distributing questionnaires to 1120 patients mainly by mail.

Variables

The Network provides a standard set of self-report questionnaires for routine evaluation of personality functioning, symptom distress and social/occupational functioning. All therapists are trained in systematic interviews for diagnostic evaluation according to the DSM-5 [Citation22] by use of MINI for symptom disorders [Citation23] and SCID-5-PD for PDs [Citation24]. In addition, routines are established for feedback procedures providing information on diagnoses, levels of symptoms and the treatment process. In the present study, information on diagnoses is based on patients’ report in the survey.

Data sources/measurement

Survey-specific items were:

Treatment before March 12th (answer options: pretreatment assessment, in psychotherapy, planning to end treatment), duration (months) and type of treatment (answer options: individual psychotherapy, group psychotherapy, medication).

Diagnoses received on initial assessment before starting PD treatment (answer options: avoidant PD, BPD, other PD, unknown). The answer options were based on data from the Network concerning the most frequently accounted PDs. Symptom disorders were first confirmed or rejected (yes/no). If yes, specification included options of mood disorders, anxiety disorders, OCD, eating disorders, PTSD, substance use disorder, autism, psychosis, other, and unknown.

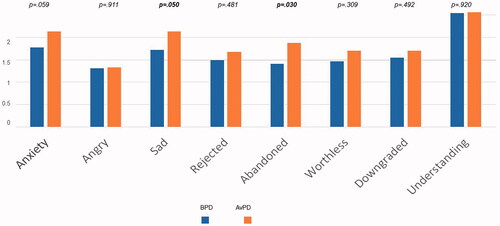

Immediate emotional reactions to the lockdown of regular treatment (answer options included a list of emotional states, , with degrees from 1 to 3) and enquiry about change in negative emotional reactions (answer options: reduced, the same, stronger).

Treatment after March 12th: (a) telephone consultations (answer option yes/no), time until first telephone (weeks). (b) Digital consultations, individual/group (answer option yes/no), and time until first individual/group digital consultation (weeks). (c) Physical face-to-face consultations, individual/group (answer option yes/no), and time until first individual/group physical face-to-face (weeks).

Not received any consultations after March 12th (answer option yes/no).

Experiences of therapy:

Frequency of contact (answer options: no contact, less than once a month, once a month, every second week, once a week, twice a week or more), regularity/quality (report with therapist)/purpose of sessions, and comparison to before March 12th (options: less frequent/worse, unchanged, more frequent/better),

Experience of telephone calls (options: intruding, all right, supportive), and not seeing the therapist (options: difficult, all right, an advantage).

Privacy concerns in remote therapies (options: no, not always, usually),

Satisfaction (options: dissatisfied, acceptable in the current situation, very satisfied),

Missing group therapy (options: no, quite a bit, a lot), thinking about group members (options: a little, quite a bit, very often), worrying about group members (options: a little, quite a bit, a lot).

Concerns about own treatment (options: not worried, quite a bit, very).

Table 1. Description of survey subsamples with BPD and AvPD (single diagnoses) compared to the NETWORK population.

Study size

From the 1120 who received the survey, the responding patients (N = 133) sent the completed survey by prepaid mail to the research center (response rate 12%). Among these, 40 patients reported having BPD and 30 patients AvPD as their only PD diagnoses. These 70 patients constitute the current study sample (see ).

Quantitative variables

Most of the variables in this study are categorical. Continuous variables include duration from close-down to contact with a therapist at the therapy unit (weeks), frequency of this contact, and the list of emotional states rated from 1 to 3.

Statistical methods

Data were analyzed by IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Release 26 (Armonk, NY) [Citation25]. In the comparison of groups with BPD and AvPD, calculation of between-group differences for categorical variables was based on Crosstabs and Pearson’s Chi-square tests, and for continuous variables t-test for independent samples was used. Cases with missing data were omitted from calculations and tables.

Results

Participants and descriptive data

shows characteristics of the 40 BPD patients and the 30 patients with AvPD and includes a comparison to regular patients in the Network registered in the period 2018 to 2020. The only significant difference between the study sample and regular Network patients was an underrepresentation of AvPD patients in the study sample (23% vs. 36%, p < 0.05).

Table 2. Treatment after March 12th.

Comparing patients with AvPD and BPD in the study sample, female gender dominated in both groups. The BPD group was, on average, seven years younger than the AvPD group (p<.001). A significantly higher proportion of AvPD patients reported a comorbid mood disorder (p<.05). Around half of the patients reported a comorbid anxiety diagnosis, and more than one-third of the patients were living alone at the time of the survey (but not significant difference between the groups). Almost a third of the BPD group reported a comorbid PTSD diagnosis, compared to 14% within the AvPD group (n.s.).

The majority of the patients (89% totally) had started in treatment at the time of the survey, while the rest were under pretreatment assessment. Significantly more AvPD patients than BPD patients were enrolled in group therapy (93% vs. 68%, p< 0.01), while there were no significant differences with respect to individual therapy.

Main results

Follow up by telephone and video consultations

All patients were offered telephone consultations from their therapist within an average of 2 weeks after lockdown. Almost everyone accepted (), and there were no group difference. A larger proportion of patients in the BPD than in the AvPD group reported to have been offered video-consultations (p< 0.05). This option was available after approximately 3 weeks from March 12th for BPD patients, while AvPD patients waited almost 6 weeks for this (, p< 0.05).

Table 3. Experiences of regularity and therapist follow-up.

Video-based group therapy was not commonly used, only 11 patients reported to have been offered this opportunity, approximately 4 weeks after lockdown, and there was no difference between the two groups (). In-person therapy was offered to more than half of the patients after an average of 7 weeks. For in-person group therapy, i.e. group with attendance, this number was only 24% (seven patients). For BPD and AVPD patients, in-person group therapy was offered within 7 and 9 weeks, respectively (not a significant difference). No patients reported not receiving any therapy or follow-up.

Medication

Fifteen of 30 AvPD patients and 21 of 40 BPD patients answered questions about medication before and after the pandemic. While all AvPD patients who used medication continued to use this, 43% in the BPD grouped group (nine of 21) reported reduced use of medication after March 12th (p= 0.014).

Regularity and experiences with the therapy

Overall, patients in both groups were satisfied with the follow-up offered by their therapy unit, and satisfaction was categorized as either ‘good enough’ or ‘excellent’ (). The groups differed on three areas (): (1) AvPD patients were offered less frequent consultations than BPD patients, most of them less than weekly (p< 0.01), (2) BPD patients reported the contact to be at regular times more often than AvPD patients (p< 0.01), and (3) more AvPD patients experienced a reduced quality of contact with the therapist after March 12th.

Table 4. Concerns about therapy.

Patients’ immediate emotional reactions about changes in the treatment

Most patients scored highest on the positive item ‘Understanding’ (more than 90% expressed a degree of accommodating attitude). There were no group differences. Across PDs, only seven patients reported no accommodating attitude.

The most significant differences between BPD and AvPD patients were found for the following negative feelings: AvPD patients expressed clearly more sadness (p= 0.05), more feeling of abandonment (p< 0.05), and to some degree more anxiety (p= 0.059) ().

There were low scores in both groups on feelings of shame, offence, and anger. Two-thirds of patients in both groups reported that these reactions had decreased by the time of the survey.

Concerns about therapy

As shown in , there were significant differences between the two patient groups concerning worries about therapy and missing the group. Ninety-four percent of the AvPD patients missed group therapy as compared to 49% of BPD patients (p= 0.001). Eighty-five percent of the AvPD patients had some or many thoughts about other group members, as compared to 60% in the BPD group (p< 0.05). When asked if they worried about other group members, three quarters of the AvPD patients reported to worry a little or a lot, in contrast to less than half of the patients in the BPD group (p< 0.05). A majority of AvPD patients (81%) worried somewhat or a lot about their own therapy, as compared to 42% of the BPD patients (p < 0.01).

Other analyses

As the AvPD patients were somewhat older than BPD patients in this sample, we investigated the influence of age on immediate emotional reactions about changes in the treatment. There were no significant correlations between age and emotional reactions. For the two items which discriminated the two groups; sadness and abandonment, Pearson’s correlations were respectively r = 0.124, p = 0. 311 and r = 0.010, p = 0.937. There was also a low correlation between age and weeks until establishments of video consultations (r = 0.520, p = 0.151).

We also investigated possible associations with depression. Patients who reported depression as an additional diagnosis were generally less satisfied with changes in the treatment situation (Pearson’s Chi sq = 6,593, p = 0.037), but this item did not differentiate between AVPD and BPD subgroups.

As there were more PTSD patients in the BPD group, we investigated if this could have biased differences between the PD subgroups. We found that comorbid PTSD did not impact scores of sadness for patients with AVPD, but sadness was higher among BPD patients with additional PTSD (Chi sq = 9,342, p = 0.009).

Discussion

Key results

There was high satisfaction in both groups, with the delivered treatment follow-up generally perceived as ‘good enough’ or ‘excellent’ (95% in the BPD group and 97% in the AvPD group). According to our original hypotheses (a and b), we expected patients with AvPD and BPD to be offered similar alternative treatments after the lockdown. The study shows there was no substantial difference in the treatment offered to the two groups, but AvPD patients reported less intensive treatment and they reported that digital solutions took longer time to establish. However, we have no information/facts about number of contacts in this period, so it may be that both groups received more similar therapy than reported.

Furthermore, we hypothesized (c) that both patient groups would react with similar, negative attitudes to the lockdown and change in treatment. Contrary to these expectations, the study demonstrates that patients with AvPD were more troubled by the change in therapy format than BPD patients. Additional analysis did not indicate that differences were explained by selection biases between the groups.

BPD patients reported more satisfaction with follow-up and reduced medication more

Patients with BPD are often more expressive, their sensibility to separation and poor emotional regulation is well described and they are more prone to high-risk behaviors [Citation26]. In response to the lockdown, therapists are likely to immediately consider potential risks and feel compelled to rapidly target interventions in order to prevent decompensation and severe adverse behaviors. In another study from the same survey [Citation10], more self-harming behaviors known before the lockdown were indeed associated with receiving more frequent therapist contact after the lockdown. Many of these patients may have had BPD. An interesting finding though, is that a large proportion of BPD patients – almost half in the studied group – report reduced use of medication during the first pandemic wave. This may be connected to a recent study of BPD patients in Spain [Citation27], where subgroup of BPD patients felt better due to less social contacts in the pandemic.

Generally, therapists treating patients with cluster C PDs have reported more positive and stable counter-transference feelings as compared to therapists treating patients with cluster A and B disorders [Citation28–30]. In a normal therapeutic setting, AvPD patients are known to evoke protective therapists’ responses [Citation31,Citation32]. However, crises management and treatment interruption are poorly described among patients with AvPD. Characteristically, AvPD patients do not have the same treatment irregularity as often described for BPD [Citation33]. It could therefore be speculated that in a crisis, such as the lockdown, the more quiet and introvert AvPD patients might not evoke so much concern among therapists. It is also conceivable that the AvPD tendency to be pleasing and submissive, may have further facilitated treatment delay [Citation34,Citation35]. In this crisis context, it is noteworthy that self-destructive actions are also prevalent among patients with AvPD.

AvPD patients were more worried about missing treatment

AvPD patients often have sparse social networks [Citation35]. Many describe anxious and fearful attachment styles in close relationships [Citation36] – tending toward withdrawal as the preferred management of personal distress. Being accustomed to isolation, it is thus easy to suspect that patients with AvPD would have advantages during periods with Covid restriction.

Both BPD and AvPD patients are known to be highly sensitive to rejection [Citation37] and although AvPD research is scarcer, proneness to negative rumination has been demonstrated [Citation38]. The present study points to how AvPD patients were far more attached to the treatment situation than assumed and feelings of abandonment and sadness were frequently reported. The lack of group therapy during the lockdown was common to both BPD and AvPD patients. However, unexpectedly, a larger proportion of AvPD patients explicitly reported missing group sessions and being worried about their therapy in general. Only patients enrolled in group therapy were compared here; hence, there was no bias caused by the fact that less BDP patients received group therapy by 12 March 2020. The present study thus suggests that the distress associated with the treatment interruption and change of format was stronger among AvPD patients than among patients with BPD.

Possible lack of competence on AvPD crises management

The differences observed in this study, include both the actual quantity of received treatment and the patients experience of the treatment interruption and alternative formats. It points to a possible lack of competence in crises understanding and management for AvPD.

The study highlights the importance of AvPD patients’ relation to therapists and relations within treatment groups. The expense of a long-standing avoidant personality strategy is often loneliness. Over time, patients lack possibilities to develop and refine relational competence, the sharing of feelings and experiences, learning through community, experiencing trust and consolement. It may be profoundly difficult to enter a therapeutic process addressing such highly sensitive issues. In such a perspective, as possibly indicated in our study, involuntary interruption of an ongoing therapy is a major issue.

In sharp contrast to the evidence-base for BPD treatment, structured, manualized treatments for AvPD are generally not established [Citation29,Citation39]. Treatment for AvPD often incorporates elements from BPD treatments, cognitive and psychodynamic approaches, including adjusted psychoeducation, and group and individual therapy formats. It is conceivable, that a lack of AvPD treatment standards and specific techniques may have facilitated some passivity among therapists concerning what to offer this patient group in a crisis situation and how rapid a response is needed. In a qualitative study from our research group, based on the same sample, patients described vulnerability for not being remembered in the pandemic crisis [Citation40].

Strength and limitations

The pandemic is an extraordinary situation, and we emphasize that this is one of the first studies to compare two clinically frequent PD groups during the Covid-19 crisis and their experiences of the crisis-induced treatment changes. The study captures the first wave of Covid-19 in Norway, where fear and depression were generally enhanced in the general population [Citation1] as well as patients with PD [Citation21]. It is based on an anonymous survey and hence not biased by the patient’s relations to their therapists or units. Patients are recruited from a naturalistic, real-life, clinically relevant, treatment setting within the Network [Citation10].

The low response rate and small sample size limits our conclusions. The frame of the study, which was based on anonymous data, did not give opportunity to compare responders to non-responders or late responders on clinical measures [Citation41]. However, demonstrates a high degree of similarity on essential measures when comparing the responders to data from the research database of whole Network sample. The small sample size may have obscured possible differences between our samples, and regarding the lack of studies on AVPD, the differences detected in our investigation are thus noteworthy.

AVPD and BPD subgroups differed on some variables. Mean age was higher, depression more frequent and there were less PTSD diagnoses in the AvPD group. This may have influenced between-group differences. However, the further investigation of these factors concluded that the differences found between BPD and AvPD were not likely biased by age, depression or comorbid PTSD.

Patients in this survey were asked to label their own diagnosis. This procedure may render uncertainty as regards to correct classification. However, in a survey among psychiatric patients in general, more than 60% labeled their own diagnosis correctly [Citation42]. The Network is a collaboration of specialized PD treatment units, and patients are subjected to thorough diagnostic evaluation by semi-structured interviews before starting therapy. It is a highly recommended practice to have extensive feedback and dialogue on the results of the assessment before entering therapy. The evaluation forms a starting point of treatment, informs the choice of interventions and design of treatment plans and case formulations. Hence, it is likely that the patients who responded were well informed on their diagnoses, possibly more so than in the general psychiatric population. Twelve percent reported not knowing their diagnosis. This is roughly comparable to the percentage of survey patients still under pretreatment assessment.

AvPD patients may have different ways of expressing themselves, with possible different response styles compared to BPD patients. However, different response styles in surveys with AvPD and BPD patients has to our knowledge not been documented in any study so far.

Conclusion

Both subgroups (AvPD and BPD) reported high satisfaction with treatment follow-up and changes in therapy formats during the first Covid-19 pandemic wave. Nonetheless, the present study shows noteworthy differences in treatment experiences. Patients with AvPD reported a prolonged time interval before established contact with therapists and less regularity of sessions. Moreover, AvPD patients reported more often feelings of abandonment and sadness as a reaction to the shutdown. Results may indicate that the vulnerability of patients with AvPD is more easily overlooked or underestimated by therapists.

Generalizability: The main limitation is a small sample size which limits the generalizability of findings. However, results do encourage further research on AvPD as a condition, which no less than BPD, needs to be considered in times of crises and unexpected treatment interruptions.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the efficient research assistance of Elise Bynander, Outpatient Clinic for Specialized Treatment of Personality Disorders, Section for Personality psychiatry and specialized treatments, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo. We also wish to thank the patients and staff from the following 12 units of the Norwegian Network for Personality Disorders for their contribution to this study: Unit for Group Therapy, Øvre Romerike District Psychiatric Center, Akershus University Hospital HF, Jessheim; Group Therapy Unit, Nedre Romerike District Psychiatric Center, Akershus University Hospital, Lillestrøm; Group Therapy Unit, Follo District Psychiatric Center, Akershus University Hospital, Ski; Group Therapy Unit, Kongsvinger District Psychiatric Center, Akershus University Hospital; Section for Personality psychiatry and specialized treatments, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo; Group Therapy Unit, Lovisenberg District Psychiatric Center, Lovisenberg Hospital, Oslo; Unit of Personality psychiatry, Vinderen Psychiatric Center, Diakonhjemmet Hospital, Oslo; Unit of Personality psychiatry, Vestfold District Psychiatric Center, Sandefjord; Unit for Intensive Group Therapy, Aust-Agder District Psychiatric Center, Sørlandet Hospital, Arendal; Unit for Group Therapy, District Psychiatric Center, Strømme, Sørlandet Hospital HF, Kristiansand; Group Therapy Unit, Stavanger District Psychiatric Center, Stavanger University Hospital, Stavanger; Section for group treatment, Kronstad District Psychiatric Center, Helse Bergen and Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen.

Disclosure statement

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability statement

Output files from SPSS data are available on request from corresponding author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kjell-Einar Zahl

All authors collaborate in the research group of Personality Psychiatry, University of Oslo, which is headed by EHK (MD, PhD, associate professor/Head senior consultant, Section for Personality Psychiatry).

KEZ (MA) is a senior psychologist and represents five of the participating units. KEZ is engaged in clinical research within treatment of patients with personality disorder.

Geir Pedersen

GP (MA, PhD, head of the Norwegian Network for Personality Disorders) has experience within clinical research implementation, and psychometric assessments. EHK and GP are joint principle investigators in this project.

Ingeborg Ulltveit-Moe Eikenaes

LIS (MA, PhD) is a researcher/senior psychologist. Her main research interests are within qualitative methodology, case studies, and research focusing on self-harming behaviors among adolescents.

Line Indrevoll Stänicke

MSP (MA) has a Masters degree of Nursing - Clinical Research and Professional Development and works currently within the addiction field. She has experience with qualitative research methods and also represents a user perspective.

Theresa Wilberg

ÅLB (BA) works currently as communications advisor at the National Advisory Unit for Personality Psychiatry. She is also engaged in health service implementation, qualitative research and user representation.

Åse-Line Baltzersen

MSJ (MD, PhD, head senior consultant) heads one of the participating clinical units. She has clinical and research experience within assessment and treatment of patients with personality disorder.

Mona Skjeklesaether Pettersen

IU-ME (MD, PhD) is head of the National Advisory Unit for Personality Psychiatry and has clinical and research experience within assessment and treatment of patients with personality disorder.

Benjamin Hummelen

EA (MA, PhD) is a clinical psychologist/researcher and head of an addiction research unit. He has clinical and research experience within assessment of patients with personality disorder and a broad range of treatments.

Espen Arnevik

BH (MD, PhD) is a senior consultant/researcher with broad experience of clinical research, project implementation, statistical methodology, diagnostic assessment and treatment of personality disorder.

Merete Selsbakk Johansen

TW (MD, PhD) is a senior consultant/researcher with broad experience of clinical research, project implementation, psychotherapy research, assessment and treatment of personality disorder.

Elfrida Hartveit Kvarstein

EHK (MD, PhD) has clinical and research experience within differential diagnostic assessment and treatment of patients with personality disorder.

References

- Hoffart A, Johnson SU, Ebrahimi OV. Loneliness and social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: risk factors and associations with psychopathology. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:589127.

- Lazzari C, Shoka A, Nusair A, et al. Psychiatry in time of covid-19 pandemic. Psychiatr Danub. 2020;32(2):229–235.

- Vissink CE, van Hell HH, Galenkamp N, et al. The effects of the COVID-19 outbreak and measures in patients with a pre-existing psychiatric diagnosis: a cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord Rep. 2021;4:100102.

- Preti E, Di Pierro R, Fanti E, et al. Personality disorders in time of pandemic. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(12):80.

- Moreno C, Wykes T, Galderisi S, et al. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(9):813–824.

- Moesmann Madsen M, Dines D, Hieronymus F. Optimizing psychiatric care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2020;142(1):70–71.

- Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, Young D. The frequency of personality disorders in psychiatric patients. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2008;31(3):405–420.

- Johansen MS, Normann-Eide E, Normann-Eide T, et al. Emotional dysfunction in avoidant compared to borderline personality disorder: a study of affect consciousness. Scand J Psychol. 2013;54(6):515–521.

- Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, et al. Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(2):276–283.

- Kvarstein EH, Zahl KE, Stänicke L, et al. Vulnerability of personality disorder during the covid-19 crises – a multicenter survey of treatment experiences among patients referred to treatment. Nordic J Psychiatry. 2021;76(1):52–63.

- Karterud S, Pedersen G, Bjordal E, et al. Day treatment of patients with personality disorders: experiences from a Norwegian Treatment Research NETWORK. J Pers Disord. 2003;17(3):243–262.

- Poletti B, Tagini S, Brugnera A, et al. Telepsychotherapy: a leaflet for psychotherapists in the age of COVID-19. A review of the evidence. Counsel Psychol Quart. 2021;34(3–4):352–367.

- Plumley S, Kristensen A, Jenkins PE. Continuation of an eating disorders day programme during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Eat Disord. 2021;9(1):34.

- Reis S, Matthews EL, Grenyer B. Characteristics of effective online interventions: implications for adolescents with personality disorder during a global pandemic. Res Psychother. 2020;23(3):488.

- Weinberg H. Online group psychotherapy: challenges and possibilities during COVID-19—a practice review. Group Dyn Theory Res Pract. 2020;24(3):201–211.

- van Dijk SDM, Bouman R, Folmer EH, et al. (Vi)-rushed into online group schema therapy based day-treatment for older adults by the COVID-19 outbreak in The Netherlands. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28(9):983–988.

- Álvaro F, Navarro S, Palma C, et al. Clinical course and predictors in patients with borderline personality disorder during the COVID-19 outbreak: a 2.5-month naturalistic exploratory study in Spain. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292:113306.

- Salamin V, Rossier V, Joye D, et al. Adaptations de la thérapie comportementale dialectique ambulatoire en période de pandémie COVID-19 et conséquences du confinement sur des patients souffrant d’un état- limite. Annal Méd Psychol Rev Psychiatr. 2020.

- Ventura Wurman T, Lee T, Bateman A, et al. Clinical management of common presentations of patients diagnosed with BPD during the COVID-19 pandemic: the contribution of the MBT framework. Counsel Psychol Quart. 2021.

- Probst T, Haid B, Schimböck W, et al. Psychotherapie in Österreich während COVID-19. Ergebnisse von drei Onlinebefragungen (Psychotherapy in Austriaduring COVID-19. Results of three online surveys). SSRN. 2021.

- Kvarstein EH, Zahl KE, Stänicke L, et al. Vulnerability of personality disorder during covid-19 crises – a multicenter survey of mental and social distress among patients referred to treatment. Nord J Psychiatry. 2021;9:1–12.

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th edition (DSM-V). Washington (DC); 2013.

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl. 20):22–33.

- First MB. Structured clinical interview for the DSM (SCID). Hoboken (NJ): Wiley Online Library; 2015.

- IBM. SPSS statistics for windows. Version 26.0. Armonk (NY): IBM Corp.; 2019.

- Zanarini MC, Weingeroff JL, Frankenburg FR. Defense mechanisms associated with borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 2009;23(2):113–121.

- Calvo N, Castell-Penisello E, Nieto-Fernández Z, et al. La experiencia del distanciamento social en pacientes TLP subtipo-desregulación relacional durante el primo confinaimento de la pandemia covid-19. Una seria de casos. Actas Esp Psicuiatr. 2022;50(3):167–168.

- Rossberg JI, Karterud S, Pedersen G, et al. An empirical study of countertransference reactions toward patients with personality disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48(3):225–230.

- Békés V, Aafjes-van Doorn K. Psychotherapists’ attitudes toward online therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Psychother Integ. 2020;30(2):238–247.

- Simonsen S, Eikenaes IU-M, Nørgaard NL, et al. Specialized treatment for patients with severe avoidant personality disorder: experiences from Scandinavia. J Contemp Psychother. 2019;49(1):27–38.

- Colli A, Tanzilli A, Dimaggio G, et al. Patient personality and therapist response: an empirical investigation. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(1):102–108.

- Pettersen M, Moen A, Børørsund E, et al. Therapists’ experiences with mentalization-based treatment for avoidant personality disorder. Eur J Qual Res Psychother. 2020;11:143–159.

- Kvarstein EH, Karterud S. Large variation of severity and longitudinal change of symptom distress among patients with personality disorders. Pers Ment Health. 2013;7(4):265–276.

- Nordahl H, Stiles T. The specificity of cognitive personality dimensions in cluster C personality disorders. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2000;28(3):235–246.

- Kvarstein EH, Antonsen BT, Klungsøyr O, et al. Avoidant personality disorder and social functioning: a longitudinal, observational study investigating predictors of change in a clinical sample. Pers Disord Theory Res Treat. 2021;12(6):594–605.

- Eikenaes I, Pedersen G, Wilberg T. Attachment styles in patients with avoidant personality disorder compared with social phobia. Psychol Psychother. 2016;89(3):245–260.

- Berenson KR, Van De Weert SM, Nicolaou S, et al. Reward and punishment sensitivity in borderline and avoidant personality disorders. J Pers Disord. 2020;35(4):573–588.

- Bowles DP, Meyer B. Attachment priming and avoidant personality features as predictors of social-evaluation biases. J Pers Disord. 2008;22(1):72–88.

- Lampe L, Malhi GS. Avoidant personality disorder: current insights. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2018;11:55–66.

- Stänicke LI, Arnevik E, Pettersen M, et al. The importance of feeling remembered during the covid-19 crisis – a qualitative study of experiences among patients with personality disorders. Nord Psychol. 2022;1–20.

- Johnson TP, Wislar JS. Response rates and nonresponse errors in surveys. JAMA. 2012;307(17):1805–1806.

- Wetterling T, Tessmann G. Patient education regarding the diagnosis. Results of a survey of psychiatric patients. Psychiatr Prax. 2000;27(1):6–10.