Abstract

Background

The push to systematically follow treatment outcomes in psychotherapies to improve health care is increasing worldwide. To manage psychotherapeutic services and facilitate tailoring of therapy according to feedback a comprehensive and feasible data system is needed.

Aims

To describe the Finnish Psychotherapy Quality Register (FPQR), a comprehensive database on availability, quality, and outcomes of psychotherapies.

Methods

We describe the development of the FPQR and outcome for outsourced psychotherapies for adults in Helsinki and Uusimaa hospital district (HUS). Symptom severity and functioning are measured with validated measures (e.g. CORE-OM, PHQ-9, OASIS, AUDIT, and SOFAS). Questionnaires on therapeutic alliance, risks, methods, and goals are gathered from patients and psychotherapist.

Results

During 2018–2021, the FPQR included baseline data for 7274 unique patients and 336 psychotherapists. Response rate of measures was 85–98%. The use of the register was mandatory for the outsourced therapist of the hospital districts, and the patients were strongly recommended to fulfill the questionnaires. We report outcome for three groups of patients (n = 1844) with final/midterm data. The effect sizes for long psychotherapy (Hedge’s g = 0.65 of SOFAS) were smaller than those for short psychotherapy (g = 0.75–0.91). Within three months of referral, 26–60% entered treatment depending on short- or long-term therapy.

Conclusion

The FPQR forms a novel rich database with commensurate data on availability and outcomes of outsourced psychotherapies. It may serve as a basis for a national comprehensive follow-up system of psychosocial treatments. The Finnish system seems to refer patients with milder symptoms to more intensive treatments and achieve poorer results compared to the IAPT model in UK, Norway, or Australia.

Introduction

A solid body of evidence supports the cost-effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions for mental disorders [Citation1–3]. Nevertheless, organizing a comprehensive psychotherapeutic service that can implement evidence-based treatment methods and realize measurable benefits in real-life is complicated [Citation4–6]. One key component of success is the ability to track both functioning of the whole service on macro level and outcomes of psychotherapy on individual patient and therapist level [Citation7,Citation8]. To manage a psychotherapy services system in an evidence-based manner, one should be able to follow treatment availability, waiting times, the process of matching patients to therapists, therapy process, multidimensional outcomes and side effects, costs, and personnel issues. All this should be done without excessively burdening therapists or patients. To complicate matters further, psychotherapy is often provided on many levels of health care systems, in complex multi-provider settings, and using a plethora of different interventions for the same problem, making it hard to manage as a whole. For psychotherapy research, studying the outcomes of different psychotherapies in a comprehensive naturalistic database is of great interest. A comprehensive database that includes information on individual patients, therapists, alliance and therapeutic methods would provide a unique possibility to study the factors that mediate or moderate therapy outcomes – different frameworks, diagnoses and so called common factors of psychotherapy all in same database [Citation9]. Optimizing common factors may boost outcome-oriented health services, as they seem to account for a large proportion of variance in therapy outcomes [Citation10–12].

The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) program in the UK is an example of a national level approach to organize treatment provision and efficient data collection within comprehensive services. Since 2008, thousands of therapists have been trained within the IAPT program to deliver evidence-based treatment methods recommended in NICE guidelines for mild to moderate depression and some anxiety disorders. Annually more than a 0.6 million referrals access the services, and more than 50% of patients recover [Citation13,Citation14]. The IAPT program has inspired mental health development in many other countries, Finland included [Citation15–18].

In Finland, the responsibility to provide primary care treatment is scattered for around 330 municipalities. The municipalities form 20 hospital districts that are responsible for specialty care and psychiatry, including psychotherapy. However, the largest funding source for psychotherapies is the Social Insurance Institution of Finland (SII) that funds mostly long psychotherapy (i.e. 1–3 years). Only certified psychotherapists with minimum training of 60 ECTS credits may provide psychotherapy. The Finnish healthcare system is undergoing a thorough reform in 2023, centralizing municipalities’ responsibilities to 22 regions.

The SII funding is available only for ‘rehabilitative psychotherapy’ and limited to people aged 16–67 years and who are employed or likely to return to work or studies. This excludes patients whose likelihood to return to working life is low, as well as retired and adolescents. To get into this rehabilitative psychotherapy, a psychiatrist statement and a minimum of three months treatment without sufficient response are needed. This creates a structural delay and a practical bottleneck due to the shortage of psychiatrists. In Finland, with a population of 5.5 million, the SII uses over 100 million euros annually to fund psychotherapy for over 60,000 persons [Citation19].

To supplement SII-funded psychotherapy also hospital districts and municipalities offer psychotherapies, often outsourced to private practitioners. Helsinki and Uusimaa hospital district (HUS, the largest in Finland) uses vouchers to provide outsourced psychotherapies free of cost for the patient. Therapists are accepted to the system according to certain criteria. Different vouchers are given to different patient groups according to evidence-based guidelines. For example, patients with bipolar or psychotic disorder can be treated only by a clinically experienced psychotherapist trained in cognitive or integrative frameworks, whereas a patient with uncomplicated unipolar depression can select a psychotherapist of any evidence-based framework.

The supply of short, structured psychosocial treatments targeted to mild to moderate symptom levels has been very limited, with only internet-delivered CBT being available nationwide. A national First-line Therapies initiative is trying to remedy this by introducing a selection of evidence-based psychosocial interventions into primary care [Citation18].

For psychotherapy research, studying the outcomes of different psychotherapies in a comprehensive naturalistic data are of great interest. A comprehensive database that includes information on individual patients, therapists, alliance and therapeutic methods would provide a unique possibility to study the factors that mediate or moderate real-life therapy outcomes – different frameworks, diagnoses and so-called common factors of psychotherapy, all in same database [Citation9]. In a system without executive direction, gathering comparable data from different organizations, and using it for benchmarking, is a way to improve the performance of the whole system through self-organized convergence toward visibly efficient practices.

In this paper, we describe the development and initial results of the Finnish Psychotherapy Quality Register (FPQR) that was created to provide structured data on psychotherapy availability, process, outcomes, and mediating factors across multi-provider service system. The aim is to evaluate the feasibility of the register from health care systems point-of-view and describe the potential for psychotherapy research.

Methods

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of HUS (HUS/3150/2020) and the study permission was granted by Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital district (HUS/2293/2021). As the study uses only register data, no informed consent of the patients was required.

Developing the first version of the register

The first version of FPQR was developed during 2016–2018 as a joint effort of all five Finnish university hospitals and the technical solution was provided by the BCB Medical [Citation20] software company. In 2016, HUS convened a consortium of experts from all university hospitals to develop the psychotherapy quality register. The consortium held consensus meetings twice a year throughout 2016–2018, to select instruments and create questionnaires included in the register. Department heads and leading scientific and clinical experts were included in an iterative process, as the register aims to fulfill both management and scientific needs. The leading principle in this work was to find an optimal combination of validated outcome measures without excessively burdening patients or therapists. Register content was defined separately for adult (>18 years), adolescent (13–18 years), and child (<13 years) psychiatry, as these are three different medical specialties in Finland. This paper presents the content of FPQR for all age-groups. However, as the implementation of the register is separate for different age groups and started with adults, the implementation and baseline data are presented only for adults.

The FPQR is integrated to hospital EHR systems so that public sector employees can access the register via them. It can also be used as a standalone program (in case of private therapists) via web interface.

Main indicators including number of patients, waiting times, and treatment outcomes are collected on a Power-BI-based dashboard. These variables can be stratified by diagnostic groups, age categories, site of referral or therapeutic framework, etc. The dashboard is open and modifiable for the team responsible for organizing psychotherapies. Key indicators are presented in a summary report to heads of units.

Data gathering process and instruments used

All patients and therapists fill in questionnaires at least in the beginning and at the end of therapy, and annually in case of a long (i.e. 1–3 years) psychotherapies. Since 2021, therapists have the possibility to use the FPQR for routine outcome measuring (ROM) by activating the questionnaires as often as needed.

Evaluations on therapeutic alliance, risks, methods, and goals are gathered from patients and psychotherapists. Patients provide information on medication and socioeconomic status. They can give direct feedback to the referring professional in case they do not want to raise an issue with the therapist. These detailed PREMs (patient reported expectation measures) are a specific strength of the FPQR (see the supplementary appendix).

Symptom severity and functioning are measured with validated measures (CORE-OM [Citation21], PHQ-9 [Citation22], OASIS [Citation23], AUDIT [Citation24], and SOFAS [Citation25]) for all adult patients. Diagnosis-specific questionnaires are included when appropriate (e.g. EDE-Q [Citation26] in eating disorders or BPRS [Citation27] psychotic disorder).

The case manager opens the case in FPQR at the time of referral. The register automatically collects background information (age, sex, and date of referral) from the EHR. The patient selects a therapist according to the clinical recommendations from a list of available therapists.

The adult and adolescent patients get an SMS or email containing a link and a unique pin-code to the questionnaires, which can be filled in using a smartphone, tablet, or computer. The therapists are advised to help patients in case of technical problems. Children’s questionnaires all filled in at the appointment in the outpatient clinic. The therapist logs in to the software to fill in the questionnaires.

The software generates a structured case summary at the start and end of therapy. Once the summary is approved by a locally authorized person, it is saved to the local EHR system and, via that, to the national patient data repository.

The data gathering process and instruments used are summarized in and supplementary material.

Table 1. Summary of register process and content of all age groups.

Table 2. Data coverage by therapy class (%).

Table 3. Patient background variables by therapy class (%), adult outsourced psychotherapies (n = 1844).

Implementation and uptake

We present the implementation of FPQR in Helsinki University Hospital. The implementation in HUS child and adolescent psychiatry, and many other hospital districts is ongoing.

The register opened for pilot testing June 2018. Official implementation was started in September 2018. In the first phase, all psychotherapies that the HUS purchases for adults from private producers were included. Outsourced services form the main body of psychotherapies offered to adult patients and include three groups: (1) primary care patients referred to short psychotherapy (later: ‘short psychotherapy, primary care’), (2) patients in psychiatric specialty care, referred to short psychotherapy (‘short psychotherapy, specialty care’) and (3) patients in psychiatric specialty care, referred to long psychotherapy (‘long psychotherapy’). Short psychotherapy covers up to 20 sessions; long psychotherapy includes 40 sessions per annum, for up to three years. Therapists commit to using the FPQR when applying to become a provider of outsourced services. Invoicing checks that the therapist have entered the data before the invoices are approved. Thus, the incentives for using the register are clear for the therapists. Response rate can be calculated by comparing invoicing and FPQR. Non-Finnish speaking therapists are not required to use FPQR because the contents are only in Finnish. A short (0.5–2 h, live or online) training in the software is offered to the therapists. Additional training and individual help in using the registry is available on demand.

The measures and questionnaires have not changed, but otherwise the software has been constantly updated. Due to challenges related to privacy protection, the first version of the software did not allow private psychotherapists to access any patient data. This was obviously demotivating for psychotherapists. Versions since autumn 2021 allow the psychotherapists to access the data of their own patients, as well as to send extra symptom measures to patients at any time. This enables therapist to use FPQR for continuous ROM for example on weekly basis. Therapists can also add new questionnaires in case new symptomatology emerges or the focus of the therapy is changed during the course of the treatment. Therapists are encouraged to use the system for tailoring their treatment according to individual outcome measuring [Citation42]. The therapists are offered free training on the rationale and evidence behind ROM and feedback informed therapy as well as technical support to encourage uptake.

Psychotherapists producing the SII funded psychotherapies were also given a possibility to use the FPQR for patients in HUS area, but this was not required by SII. Instead, the SII requires the therapists to produce annually a semi structured written case summary, which could not be replaced by the automatically formed case summary of the FPQR. In consequence, the FPQR was used only by a very few SII therapists, and the practice was terminated in September 2020.

Analysis

This paper presents the data collected with FPQR in HUS catchment area during the first three years (6/2018 to 9/2021). We present data on adults, as these comprise 89% of patients so far. We describe the baseline characteristics only for completed short psychotherapies, and long psychotherapies treatments with at least one mid-term follow-up. For the descriptive statistics comparing groups, we used Chi-squared tests for a null hypothesis of equal frequencies across service classes. We present results on the most important symptom-inventory scores and on changes in these symptom measures during therapy separately for the three patient groups: (1) short psychotherapy, primary care, (2) psychotherapy, specialty care, and (3) long psychotherapy. Patients with several psychotherapy episodes were excluded due to the possible cumulative treatment effects and small number of such cases. We report three different but related standardized effect sizes for change of scores from pre- to post-therapy. Cohen’s d for paired samples standardizes average score change from pre- to post assessment to the standard deviation of the (within-patient) changes. Glass’s Δ standardizes change score to the unit of baseline standard deviation, being more sensible in repeated assessment and perhaps when comparing interventions that might be differentially associated with post-treatment variance [Citation43]. Finally, Hedge’s g uses pooled pre- and post-treatment variance without taking in account their statistical dependency, but it is in more familiar units than the paired-samples d and therefore has been recommended also for two repeated assessments [Citation44]. Ninety-five percent bootstrap percentile confidence intervals were computed for the effect size estimates [Citation45]. In some cases, the significance status of specific group differences was verified using Welch’s t-test.

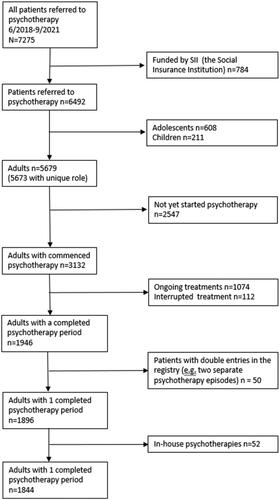

We included baseline score values only for such first recorded entries that were unanimously registered as belonging to the ‘initial’ assessment (a missing value ensued when none of the entries belonged to this phase). Furthermore, we included follow-up values only for such last records of a patient that were created at least 30 days after the initial record and that were registered as ‘midterm’ or ‘final’ assessments. That is, we enforced a conservative interpretation of the data timing wherein we disallowed retrospective recording of baseline data to the register (within 30 days from follow up), even if it might have been possible. The data flowchart is presented in .

When reporting numbers by primary diagnosis, for brevity, we grouped diagnoses to sub-categories of depressive disorders (any ICD-10 code in categories F32–F39, 45% of total cases), anxiety disorders (F40–F49, 43%), alcohol-related disorders (F10, 0%), physiology-related mental disorders (F50–F59, 2%), psychotic disorders or bipolar disorder (F20–F29 or F31, 3%), and other disorder codes (F0–09, F80–99, 4%).

Results

Data accumulation and response rates

Between June 2018 and September 2021, the register contained altogether 7275 unique psychotherapy patients (5673 adults, 608 adolescents, and 211 children). In August 2021, there were 336 unique psychotherapist producing outsourced psychotherapies.

The register includes 784 non-mandatory entries for therapies funded by SII, as the register was offered for voluntary use to follow the patients referred to SII funded psychotherapies. However, only 4.7% (37) of SII funded therapies were reported, so only entry-point data are available for the rest.

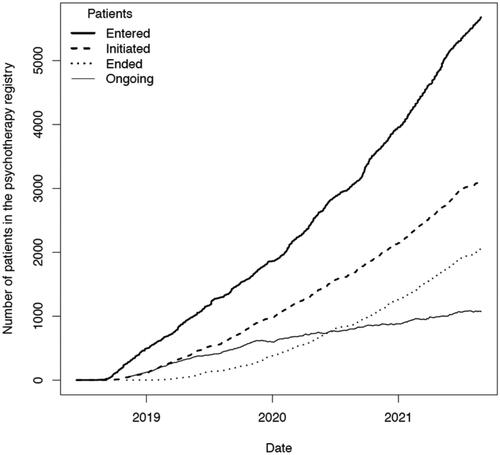

illustrates how the data on adult patients have accumulated to the register over the first three years (N = 5673).

Figure 2. Accumulation of data on adult psychotherapies to the HUS Psychotherapy Quality Register for the first three years.

Due to novelty of FPQR, 1074 (19%) of the adult psychotherapies were still ongoing at the time of our data order. Since new referrals are coming in increasing numbers, the number of patients in FPQR is growing rapidly. Many of the patients (n = 2547, i.e. 45%) had not yet started the treatment.

Altogether 112 psychotherapies were interrupted after initiation. The therapy was defined as interrupted if the therapist selected in the final evaluation the rationale for terminating the therapy as ‘interrupted’ instead of ‘planned’. If the therapy was interrupted, the therapist was asked to specify the reason in a free-text field. The interrupted therapies were not included in analyses.

In this report, we deliver results on the adult patients with single completed therapy, or a single long psychotherapy completed at least to midterm. We excluded 52 in-house produced psychotherapies. With these restrictions in effect, we focus here on altogether 1844 patients with a single registered and completed or partly completed psychotherapy.

Even among the completed psychotherapies, some parts of the data remained missing despite the strong incentives for therapists to use the register. shows the percentage of patients with data per psychotherapy group. The uptake of the register has been high among the psychotherapies outsourced from the hospital district (91–98% for psychotherapist entries and 85–92% for patient entries).

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics, therapy types and main diagnoses are presented in and . Primary care patients tended to be younger and more likely employed and cohabiting than those in specialty care.

Table 4. Therapy related patient characteristics by therapy class (%), adult outsourced psychotherapies (n = 1844).

Compared to others, patients receiving long psychotherapy were less likely to be employed, cohabiting, or suffering from anxiety disorders, and more likely to smoke, use regular psychotropic medication or suffer from schizophrenia or personality disorders. Long therapies were more likely to be psychodynamic and less likely to be solution focused.

Average symptoms and functioning

characterizes the patient population in terms of the outcome measures and reports crude effect-size measures for the difference in scores between patients’ baseline and their last reports.

Table 5. Patient outcomes by service class as average scores and effect sizes.

Overall, the symptom scores at baseline were at mild to moderate levels on different measures. For example, PHQ-9 scores varied between 9.08 and 12.73 in different service classes. This is roughly at moderate depression level, which is usually defined at 10–14 points [Citation22]. OASIS scores were ≤5 in all groups indicating low levels of anxiety [Citation46].

Baseline AUDIT-C was low for all groups. CORE-OM values were in the clinical range, i.e. above the score 9.5 [Citation47]. Patients entering long psychotherapy had more symptoms at baseline and follow up, compared to the patients in short psychotherapies. The effect sizes for long psychotherapy were smaller than those for short psychotherapy. Excluding alcohol use, primary care patients did systematically better in all metrics than the special care patients, both in pre-treatment assessment (; p value ≤0.007, with only AUDIT-C having p= 0.107 in two-group Welch’s t-tests) and post-treatment assessment (all p≤ 0.007). In terms of average effect sizes, primary-care patients also responded to the treatments better than the special-care patients ().

Discussion

The push to systematically follow outcomes relevant to patients and use those to improve health care is increasing worldwide. The best way to do this in practice varies depending both on health care systems (organizers, payers and providers and their relationships) and on available health ICT solutions. The Finnish system is an example of the complexity frequent for psychotherapy services: although responsibility for mental health services is divided to over 300 municipalities, most funding for psychotherapy de-facto comes from the national social insurance institution promoting long psychotherapies in contrast to early-access treatment options. Despite the outsourced 20-session psychotherapies described here, the most prevalent form of psychotherapy in Finland is still very long psychotherapy (up to three years).

We have developed and implemented a quality registry platform for psychotherapy in Finland that is a joint effort of health care organizers and producers. The quality register has three aims: to help manage delivery and quality of psychotherapy in a complex multi-provider setting, to increase significance of empirical measures of effectiveness on system and therapist levels, and to provide a rich naturalistic database for psychotherapy research. We have described the development, the instruments, and the use of the registry, and presented a brief overview of the data from the first three years in use in Helsinki university hospital district. The present review of registry data proves the feasibility of the Finnish psychotherapy quality registry in routinely collecting outcomes and feedback in psychotherapies outsourced from public sector to private producers.

The development

Several psychotherapy quality registers and other ways to collect quality information exist in the world [Citation8,Citation42]. Whereas the ICT-applications and legal possibilities for data gathering vary between countries, the use of well-known psychometric instruments allows international comparisons. The most widespread and systematic data collection system is probably the IAPT, where a national, tax-funded system enables highly standardized data collection [Citation48]; a massive roll-out allows a recent meta-analysis to include over 600,000 patients [Citation14]. As our first implementation of FPQR also focused on IAPT via purchasing clearly defined psychotherapies, we mostly compare our data and experiences to those from the IAPT system.

A quality registry software already used in other fields of specialized health care was mandated as a starting point for the FPQR. Therefore, we could not build a fully dedicated system for psychotherapy. This delayed the availability of the therapist feedback functionality, weakening the user experience for private producers.

As for instruments, the several aims of our registry inevitably required compromises. The questionnaires cannot be too burdensome by routine users with time pressures, limiting the inclusion of instruments for scientific purposes. In practice, we used well-known and validated symptom inventories for outcome measurement but also created our own brief questionnaires for patients and therapists. These allow mapping of scientifically interesting mediating and moderating factors in a concise, user-friendly way.

The selection of instruments was based on a consensus between the university hospital experts, to secure acceptance and uptake of the registry. We are planning a review of the measures based on user feedback and on recent advances in science. Updating the measures on an ICT platform is technically easy. For example, the functionality measure SOFAS and anxiety measure OASIS are under consideration. The use of GAD-7 [Citation49] instead of OASIS [Citation23] and PSWG [Citation32] needs to be considered, to match IAPT practice [Citation6] and the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) recommendation [Citation50].

The implementation

Our approach that was based on a separate registry software, useable as standalone or as integrated to EHR systems, was deemed as the only feasible approach in a scattered multi-producer system like the one in Finland. Unfortunately, for legal reasons, identifiable data cannot be directly pooled across organizers of therapy, but all organizers need to have separate logical registers, each with their own EHR integrations and implementation processes. This adds costs, makes benchmarking more complicated and may hinder small organizations from taking the registry in use.

The use of FPQR should integrate seamlessly to normal workflow and automate as much data gathering as possible. The success in this depends on the ICT systems used by different producers.

Our next challenge is to apply the registry for therapists employed by the public sector, where monetary incentives are not possible. We hope to achieve the intrinsic motivation needed by highlighting the automatically created case summary and educating personnel about the evidence and rationale behind feedback informed treatment. This may require a switch to session-by-session symptom measurement, and better tools for giving feedback to clinicians, for example, pointing out and giving tools to tailor treatment for the patients that are not on expected track to recovery [Citation42,Citation51].

Discussion on empirical findings

Despite the challenges in implementation, our empirical results show that the FPQR can be useful for research and management of psychotherapy.

Using FPQR, we observed no differences in pre-treatment scores between patients referred to short psychotherapy from specialty care and primary care. This poses a question about the functioning of the Finnish healthcare system, as there is supposed to be a clear division of responsibility between primary and specialty care. On the other hand, symptom severity is not the only reason to sort patients to different treatment steps. Even in a highly structured stepped-care model like IAPT, patients directed to step 2 (low-intensity) or step 3 (high-intensity treatments) did not have statistically significantly different intake PHQ-9 scores (13.5 for step 2 and 15.3 for step 3, mean 15.0 for the whole sample) [Citation14]. These are clearly higher than for our patients (PHQ-9 scores at beginning of therapy were 9.8 and 9.6 for the short therapy groups and 12.5 for those beginning long psychotherapy). Australian IAPT application (‘NewAccess’) reported mean PHQ-9 scores of 12.6 [Citation15] and a Norwegian application (‘Rask Psykisk Helsehjelp’) mean scores of 12.5 [Citation16].

Thus, in our data, patients referred from specialty psychiatric care to long psychotherapy (one to three years) have lower (in case of UK) or similar (Australia and Norway) PHQ-9 scores than patients referred to ‘Step 2’ low-intensity treatments in other countries. This may result from the minimal availability of low-intensity treatments in Finland.

As for comparison of effect sizes, a meta-analysis of IAPT therapy completers using PHQ-9 showed an effect size of 1.04 (0.78 with intention to treat – analysis) and 1.09 for step 3 therapy only [Citation14]. NewAccess in Australia demonstrated PHQ-9 effect size of 1.23 [Citation15] and the Norwegian model 1.13 for those with completed pre- and post-treatment questionnaires [Citation16]. The lower effect sizes reported in our sample might be due to the larger heterogeneity compared to IAPT, since we do not have a symptom severity threshold for the treatment. Therefore, some patients are entering treatment with very low scores, and therefore, not having potential to benefit in terms of symptom reduction. Furthermore, many patients had primary diagnoses other than depression which may partly explain lower average PHQ-9 scores and lesser change in them.

Only 41% of patients started therapy within three months in our data. This contrasts with IAPT standards where 75% should start treatment within six weeks. The long waiting times presumably are to a large extent due to therapist shortage in Finland. A rather optimistic interpretation of the long waiting times and lower symptom scores is that some of the patients experience spontaneous symptom alleviation during the waiting time. Whatever is the case, further studies are warranted.

Strengths and weaknesses

Like comparable systems [Citation8,Citation52], the FPQR has some advantages and shortcomings. A special strength of FPQR are the questions considering the alliance, methods, and goal setting, including both the patient experience measures and therapists’ point of view, as well as the relatively broad set of outcome measures. The measures are automatically adapted to the diagnosis chosen as the focus in the current psychotherapy episode, but the therapist can further adapt them during the therapy. On the other hand, the broad set of measures is not suitable for session-to-session use.

The user experience of our system was clearly lacking in the beginning. Our software was updated in autumn 2021 to allow the therapist to have access to patient data and freely send any of the symptom measures to the patient during the therapy. This enables our psychotherapist to take full advantage of the software to introduce outcome informed treatment tailoring and ROM. Thus far it remains unclear whether this will be enough to get clinicians to use the service on voluntary basis.

Overall, the register data appeared of good quality but did not come with a good documentation. More should be required from technical contractors regarding research-user documentation. Nevertheless, these data belong to a national patient register, which makes them a very valuable source of information for future psychotherapy research. As for the empirical data and analyses, we only reported a crude and broad overview of the data. As the registry collapses all kinds of patient sub-groups, more sophisticated outcome analyses will be conducted later.

Conclusion

The FPQR allows, for the first time, to collect, evaluate, and systematically compare psychotherapy process and outcomes at large scale in Finland. It opens the road to both accountability on system level, and to integration of outcome feedback to individual treatment relationships [Citation8,Citation51]. The FPQR is not limited to specific EHR systems but can be used in different organizations and patient groups. The registry is in use in four out of five university hospitals and several central hospitals. The next steps include implementation to other organizations and patient groups and building national benchmarking for executive directing.

Based on our data, the Finnish system described here seems to refer patients with milder symptoms to more intensive, longer, and expensive treatments, and achieve smaller effect sizes, than services following the IAPT model in UK, Norway, or Australia. This requires further study, for example on the long delays before start of therapy.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (139 KB)Disclosure statement

All the authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Notes on contributors

Suoma E. Saarni, MD, PhD, Specialist in psychiatry and health care, Psychotherapist trainer, Adjunct professor in Psychiatric epidemiology at the University of Turku. Chief Physician at the Department of Psychiatry, Brain Center, Helsinki University Hospital and University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. Head of the National university consortium of psychotherapist training.

Tom Rosenström, PhD, PsM, Adjunct professor, Academy research fellow at the Department of Psychology and Logopedics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland.

Jan-Henry Stenberg, PhD, PsL, Head of department ICT Psychiatry and Psychosocial treatments at the Department of Psychiatry, Brain Center, Helsinki University Hospital and University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland.

Aino Plattonen, PsM, Clinical psychologist and PhD-student at the Department of Psychiatry, Brain Center, Helsinki University Hospital and University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland.

Matti Holi, MD, PhD, Specialist psychiatry, Adjunct professor, Director of Helsinki University Hospital Area, Helsinki University Hospital and University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland.

Jesper Ekelund, MD, PhD, Professor, Specialist in psychiatry, Director of Brain Center, Senior Medical Director, Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Brain Center, Helsinki University Hospital and University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland.

Niklas Granö, PhD, PsL, Adjunct professor, Leading psychologist at the Department of Adolescent Psychiatry, Brain Center, Helsinki University Hospital and University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland.

Niina Komsi, PhD, PsL, Clinical psychologist, Department of Child Psychiatry, Children and Adolescents, Helsinki University Hospital and University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland.

Samuli I. Saarni, MD, PhD EMBA, Specialist in psychiatry and health care, adjunct professor in Social Psychiatry at the University of Helsinki and Health Care Ethics at University of Turku, Finland. Program director First Line Therapies initiative, Finland.

Data availability statement

Data used in this study are not available due to ethical and legal restrictions. Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Cuijpers P. Four decades of outcome research on psychotherapies for adult depression: an overview of a series of meta-analyses. Can Psychol. 2017;58(1):7–19.

- Lambert MJ, Bergin AE. 2013. Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. Available from: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/helsinki-ebooks/detail.action?docID=1162080

- Nathan PE, Gorman JM. 2015. A guide to treatments that work. Oxford University Press, Incorporated. Available from: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/helsinki-ebooks/detail.action?docID=3564597

- Cuijpers P. The challenges of improving treatments for depression. JAMA. 2018;320(24):2529–2530.

- Delgadillo J, Lutz W. A development pathway towards precision mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(9):889–890.

- The National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. The improving access to psychological therapies manual; 2021. Available from: https://www.England.Nhs.Uk/Publication/the-Improving-Access-to-Psychological-Therapies-Manual/; https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/the-improving-access-to-psychological-therapies-manual/

- Delgadillo J, Huey D, Bennett H, et al. Case complexity as a guide for psychological treatment selection. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2017;85(9):835–853.

- Lutz W, Rubel JA, Schwartz B, et al. Towards integrating personalized feedback research into clinical practice: development of the trier treatment navigator (TTN). Behav Res Ther. 2019;120:103438.

- Cuijpers P, Reijnders M, Huibers MJH. The role of common factors in psychotherapy outcomes. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2019;15:207–231.

- Crits-Christoph P, Connolly Gibbons MB. 2021. Psychotherapy process-outcome research: advances in understanding causal connections. In: Barkham M, Lutz W, Castonguay LG, editors. Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change. Vol. 2021. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. p. 263–295.

- Cuijpers P, Driessen E, Hollon SD, et al. The efficacy of non-directive supportive therapy for adult depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32(4):280–291.

- Wampold BE. How important are the common factors in psychotherapy? An update. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(3):270–277.

- Clark DM. Realizing the mass public benefit of evidence-based psychological therapies: the IAPT program. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2018;14:159–183.

- Wakefield S, Kellett S, Simmonds-Buckley M, et al. Improving access to psychological therapies (IAPT) in the United Kingdom: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 10-years of practice-based evidence. Br J Clin Psychol. 2021;60(1):e12259.

- Baigent M, Smith D, Battersby M, et al. The Australian version of IAPT: clinical outcomes of the multi-site cohort study of NewAccess. J Ment Health. 2020;1–10.

- Knapstad M, Nordgreen T, Smith ORF. Prompt mental health care, the Norwegian version of IAPT: clinical outcomes and predictors of change in a multicenter cohort study. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):260.

- Kobori O, Nakazato M, Yoshinaga N, et al. Transporting cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and the improving access to psychological therapies (IAPT) project to Japan: preliminary observations and service evaluation in Chiba. J Ment Health Train Educ Pract. 2014;9(3):155–166.

- Saarni SI, Nurminen S, Mikkonen K, et al. The Finnish therapy navigator—digital support system for introducing stepped care in Finland. Psychiatria Fennica. 2022;53:120–137.

- Official Statistics of Finland & Harpf. Statistical yearbook of the social insurance institution 2020; 2021, p. 490. Available from: https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/336533/Kelan_tilastollinen_vuosikirja_2020.pdf

- BCB Medical; 2021. Available from: https://bcbmedical.com/

- Evans C, Connell J, Barkham M, et al. Towards a standardised brief outcome measure: psychometric properties and utility of the CORE-OM. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:51–60.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613.

- Norman SB, Cissell SH, Means-Christensen AJ, et al. Development and validation of an Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS). Depress Anxiety. 2006;23(4):245–249.

- Kriston L, Hölzel L, Weiser A-K, et al. Meta-analysis: are 3 questions enough to detect unhealthy alcohol use? Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(12):879–888.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV. Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

- Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. Guilford Press; 2008.

- Ventura J, Green MF, Shaner A, et al. Training and quality assurance with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale: ‘the drift busters’. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1993;3(4):221–244.

- Bohus M, Kleindienst N, Limberger MF, et al. The short version of the borderline symptom list (BSL-23): development and initial data on psychometric properties. Psychopathology. 2009;42(1):32–39.

- Weiss DS. The impact of event scale: revised. In: Cross-cultural assessment of psychological trauma and PTSD. Springer Science + Business Media; 2007. p. 219–238.

- Foa EB, Huppert JD, Leiberg S, et al. The obsessive-compulsive inventory: development and validation of a short version. Psychol Assess. 2002;14(4):485–496.

- Furukawa TA, Katherine Shear M, Barlow DH, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for interpretation of the panic disorder severity scale. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(10):922–929.

- Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, et al. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behav Res Ther. 1990;28(6):487–495.

- Nijenhuis ER, Spinhoven P, Van Dyck R, et al. The development and psychometric characteristics of the Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire (SDQ-20). J Nerv Ment Dis. 1996;184(11):688–694.

- Connor KM, Davidson JR, Churchill LE, et al. Psychometric properties of the social phobia inventory (SPIN). New Self-Rating Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:379–386.

- Twigg E, Barkham M, Bewick BM, et al. The young person’s CORE: development of a brief outcome measure for young people. Counsel Psychother Res. 2009;9(3):160–168.

- Pirskanen M, Laukkanen E, Pietilä A-M. A formative evaluation to develop a school health nursing early intervention model for adolescent substance use. Public Health Nurs. 2007;24(3):256–264.

- Kabacoff RI, Miller IW, Bishop DS, et al. A psychometric study of the McMaster family assessment device in psychiatric, medical, and nonclinical samples. J Fam Psychol. 1990;3(4):431–439.

- Spence SH. Structure of anxiety symptoms among children: a confirmatory factor-analytic study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1997;106(2):280–297.

- Loewy RL, Pearson R, Vinogradov S, et al. Psychosis risk screening with the Prodromal Questionnaire – Brief Version (PQ-B). Schizophr Res. 2011;129(1):42–46.

- Koskelainen M, Sourander A, Kaljonen A. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire among Finnish school-aged children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;9(4):277–284.

- Chorpita BF, Yim L, Moffitt C, et al. Assessment of symptoms of DSM-IV anxiety and depression in children: a revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38(8):835–855.

- Delgadillo J, Overend K, Lucock M, et al. Improving the efficiency of psychological treatment using outcome feedback technology. Behav Res Ther. 2017;99:89–97.

- Rosenström TH, Ritola V, Saarni S, et al. Measurement invariant but non-normal treatment responses in guided internet psychotherapies for depressive and generalized anxiety disorders. Assessment. 2021.

- Goulet-Pelletier J-C, Cousineau D. A review of effect sizes and their confidence intervals, part I: the Cohen’s d family. Quant Methods Psychol. 2018;14(4):242–265.

- Efron B, Tibshirani R. An introduction to the bootstrap. Chapman & Hall; 1993.

- Campbell-Sills L, Norman SB, Craske MG, et al. Validation of a brief measure of anxiety-related severity and impairment: the Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS). J Affect Disord. 2009;112(1–3):92–101.

- Honkalampi K, Laitila A, Juntunen H, et al. The Finnish clinical outcome in routine evaluation outcome measure: psychometric exploration in clinical and non-clinical samples. Nord J Psychiatry. 2017;71(8):589–597.

- NHS England. Psychological therapies. A guide to IAPT data and publications. NHS Digital; 2021. Available from: https://nhs-prod.global.ssl.fastly.net/binaries/content/assets/website-assets/data-and-information/data-sets/iapt/guide-to-iapt-data-and-publications.pdf

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097.

- Obbarius A, van Maasakkers L, Baer L, et al. Standardization of health outcomes assessment for depression and anxiety: recommendations from the ICHOM Depression and Anxiety Working Group. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(12):3211–3225.

- Bone C, Simmonds-Buckley M, Thwaites R, et al. Dynamic prediction of psychological treatment outcomes: development and validation of a prediction model using routinely collected symptom data. Lancet Digit Health. 2021;3(4):e231–e240.

- Delgadillo J, McMillan D, Gilbody S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of feedback-informed psychological treatment: evidence from the IAPT-FIT trial. Behav Res Ther. 2021;142:103873.