Abstract

Background

Previous research on patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) has indicated negative effects, including increased suicidality, from long hospital admissions and paternalism. Still, long-term compulsory admissions have been reported to occur regularly. Less is known about how healthcare personnel perceives these admissions and to what extent they think the use of compulsory care can be diminished. This study addresses those questions to make care more beneficial.

Methods

A questionnaire study, the respondents being nurses and psychiatric aides employed at psychiatric hospital wards in Sweden. The questionnaire contained questions with fixed answers and room for comments. 422 questionnaires were distributed to 21 wards across Sweden, and the response rate was 66%. The data were analysed with descriptive statistics and qualitative descriptive content analysis.

Results

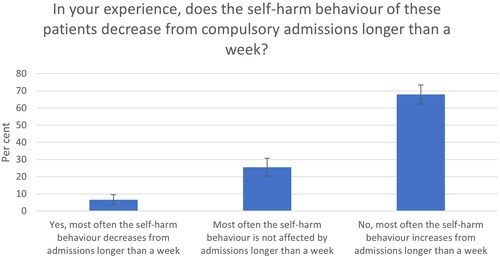

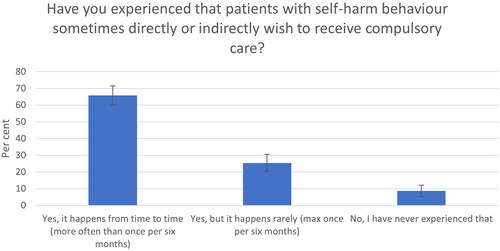

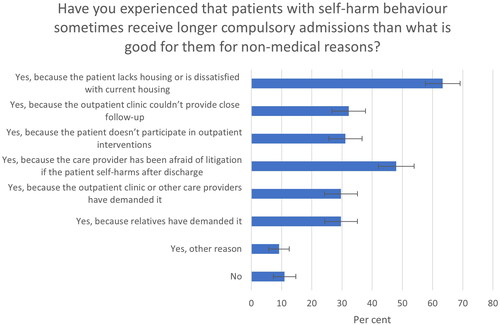

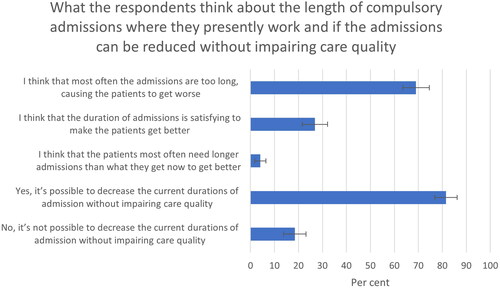

Most respondents experienced that more than a week’s compulsory admission either increased (68%) or had no effect (26%) on self-harm behaviour. A majority (69%) considered the compulsory admissions to be too long at their wards, with detrimental effects on the patients. They also recognized several reasons for compulsory admissions without medical indication, like doctors’ fear of complaints and patients’ lack of housing. Also, patients sometimes demand compulsory care. Respondents recommended goal-oriented care planning, around three-day-long voluntary admissions, and better outpatient care to reduce compulsory hospital admissions.

Discussion

These findings imply that many BPD patients are regularly forced to receive psychiatric care that inadvertently can make them self-harm more. The respondents’ comments can be used as a source when formulating clinical guidelines.

Introduction

Compulsory inpatient care is often used for patients who are assessed with increased suicide risk. This stems from the commonly wielded idea that suicidality is a sign of a psychiatric disorder, which can be successfully treated in the hospital under surveillance, and later the patient can return home feeling well and not being acutely suicidal anymore [Citation1]. The short time the patient is detained against their will is considered a minor violation compared to the great benefit of receiving life-saving care. For some patients, this picture may be true, but for other patients, the reality is more complicated. One group of patients seems to fit exceptionally poorly with the idealised picture of inpatient compulsory care, and that is patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD).

BPD patients have difficulties constructively handling and tolerating negative emotions and life events from early adulthood and forth [Citation2]. Their difficulties lead to rapid mood swings depending on internal or external stressors, dysregulated emotions, separation sensitivity, and transient dissociative symptoms. Also, the patients often develop suicidal behaviour, to escape what they perceive to be unbearable feelings or situations [Citation2–4]. In this paper, suicidal behaviour falls under the broader concept of self-harm behaviour, meaning intentional self-poisoning or injury, with both suicidal and non-suicidal intent [Citation5]. BPD patients usually experience relentless crises due to their maladaptive reactions to normal life stressors and the emotions such events trigger [Citation2]. This background can explain why BPD patients often get in contact with emergency mental health services.

Even though psychiatric hospital admission can seem like a good alternative for BPD patients in crisis, the collected body of evidence suggests that BPD patients do not benefit from staying in the hospital for suicide-protective reasons [Citation2,Citation6–9]. Longer admissions can lead to negative effects such as increased suicidal behaviour [Citation2,Citation6–9], but it has not been thoroughly studied at what length of admission those negative effects begin to show.

When it comes to compulsory care, BPD patients in crisis tend to want others to take responsibility for handling their destructive impulses. Even if the healthcare providers can feel obliged to do so, overtaking the patient’s autonomy by using compulsory care can undermine the patient’s self-efficacy and ability to handle future crises. Consequently, clinical recommendations such as NICE guidelines recommend inpatient care and compulsory care be used sparingly and instead recommend caregivers strengthen their patients’ autonomy and treat them in outpatient care – preferably with psychological interventions [Citation9].

To detain a person under compulsory inpatient care in Sweden, the person must be assessed to suffer from a 'severe psychiatric disorder' and to be in imperative need of psychiatric inpatient care. Also, the person must refuse such care or not be able to partake in the care voluntarily due to the severe psychiatric disorder. The patient’s own need is to be decisive when deciding on compulsory care and the compulsory measures should be proportionate to the objective of the measure (Supplementary Appendix I), [Citation10,Citation11]. According to the proposition of the Swedish Mental Health Act, BPD is not considered to be a 'severe psychiatric disorder’ unless the patient has an 'impulsive breakthrough of psychotic character’ [Citation11]. Such dissociative breakthroughs are described in the diagnostic criteria of BPD and are transient [Citation3]. Therefore, compulsory detention of BPD patients without co-morbidity has little legal support – especially if the compulsory care stretches over more than a few days.

The information presented above contrasts with the fact that BPD patients, mostly young women, are overrepresented when it comes to compulsory care and compulsory measures due to suicidal behaviour [Citation12]. There have also been reports of long non-beneficial hospital admissions for BPD patients at some psychiatric clinics [Citation13], that there may be non-medical motives for such care [Citation13–16], that patients sometimes demand to be compulsorily admitted [Citation15,Citation17], and that the patients’ interaction style (e.g. being demanding) may affect how much care they receive [Citation13]. In conclusion, many BPD patients seem to be treated against their will for longer periods than what is recommended in clinical guidelines or that have legal support, sometimes for non-medical reasons. Such practice can be negative for the patients and increase their suicide risk.

This study aimed to answer our research questions on to what extent non-beneficial compulsory care is used for BPD patients at different inpatient units in Sweden, how healthcare providers perceive the length of compulsory admissions to correlate with negative outcomes, what the non-medical motives are for non-beneficial compulsory care, and whether the respondents think the compulsory admissions can be shortened. We also wanted to investigate the phenomenon of patients demanding compulsory care and how the patients’ interaction style may affect care. Finally, we inquired about the care providers’ suggestions on how to decrease compulsory admissions without decreasing care quality. With this knowledge, we wish to spark a discussion about when and to what extent compulsory care can be ethically, medically, and legally justified, and hopefully decrease the use of compulsory care that is not beneficial for BPD patients.

Materials and methods

Population

In 2021 a questionnaire survey was sent to nurses and psychiatric aides at psychiatric inpatient clinics across Sweden. In Sweden, there are 21 municipalities. We included wards treating self-harming patients – one from each municipality – to participate in the study. Eighteen wards participated in May and three in September because of local practical reasons. The wards were contacted randomly in each municipality, and the first ward to accept participation was included in the study. Twenty questionnaires were sent to each ward to be distributed to the staff, except one ward which accidentally distributed 22 questionnaires. Four hundred and twenty-two questionnaires were distributed to 21 different wards, and 279 were answered, giving a response rate of 66%.

Survey questions

The survey questions aimed to explore the nurses’ and psychiatric aides’ views on whether BPD patients with self-harm behaviour benefit from compulsory admission longer than a week, whether the patients are compulsorily admitted too long or short at the respondent’s ward, whether the compulsory admissions could be shortened at the respondents’ ward without lowering the quality of care, if the patients sometimes demand to be compulsorily admitted, whether there are non-medical reasons for compulsory admissions that are not beneficial, and whether patients perceived as demanding or likeable received more or less care than others. Each question had fixed response alternatives. There was room for comments on each question. See Supplementary Appendix II for a translated version of the questionnaire.

Data analysis

The data from questions with fixed response alternatives was collected in the statistical programmes Excel and SPSS and analysed with descriptive statistics for categorical data. A 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated. The answers were compared to the four background factors of legal gender, profession (nurse or psychiatric aide), years of professional psychiatric experience, and the region of employment.

The respondents’ comments were analysed using qualitative descriptive content analysis, as described by Sandelowski [Citation18], to extract subcategories, categories, and themes. First, the comments were read repeatedly to get an overall impression of the content. Next, abstracted codes expressing the condensed meanings of the comments were identified. Codes expressing similar ideas were sorted into eight subcategories and then three categories. Finally, the latent content of the categories was formulated into two themes [Citation18–20]. The analysis was made inductively, with no predetermined categories.

Results

The results from the quantitative analysis show that 68% (n = 274, CI 62–73%) of the respondents considered that more than a week’s compulsory admission increased self-harm behaviour, 26% (CI 20–31%) perceived no change and 7% (CI 4–10%) responded that the patients got better (see ). Sixty-nine per cent of respondents (n = 268, CI 63-75%) considered the compulsory admissions to be too long at their wards, and 81% (n = 270, 77–86%) thought that the length of admissions could be reduced without impairing care quality (see ). The phenomenon of patients demanding compulsory care was recognized by most respondents, with 66% (n = 275, CI 60–71%) responding that it happens more often than once in six months and 25% (CI 20–31%) that it happens once every six months at the most (see ). The respondents recognized several non-medical reasons for prolonged non-beneficial compulsory admissions, for example, lack of housing for the patients (63%, n = 273, CI 58–69%) and doctors’ fear of litigation if the patient self-harms after discharge (48%, CI 42–54%) (see ).

Figure 2. Number of respondents to the first three statements: 268. Number of respondents to last two statements: 270.

Two questions concerned whether patients perceived as demanding or likeable received more or less care than other, equally ill, patients. Forty-nine per cent (n = 266, CI 43–55%) responded that demanding patients get more care, while 42% (CI 37–48%) responded that this did not affect care, and 9% (CI 5–12%) thought they receive less care. Likeable patients were thought to be given more care according to 31% (n = 263, CI 26–37%) of the respondents, while 64% (CI 58–70) did not think this feature affected care, and 5% (CI 2–7%) thought they get less care.

There were no important significant differences correlated to background factors, except for two: First, respondents with more than 5 years of work experience in psychiatry experienced fewer benefits and more negative effects of longer admissions than a week compared to respondents with a work experience of 0–5 years. Second, respondents with more than 5 years of work experience in psychiatry were more positive about decreasing the duration of admissions in their wards compared to respondents with 0–5 years of work experience in psychiatry.

shows the qualitative analysis of the respondents’ comments (full analysis can be viewed in Supplementary Appendix III). The four main themes were 'Pros and cons of compulsory care’, 'Patients’ actions and influence’, 'Compulsory admissions for other than direct medical reasons’ and 'Suggested changes to improve care'. A few respondents commented that longer compulsory admissions are sometimes helpful. Many respondents described an increase in self-harm behaviour and other negative effects of compulsory admissions longer than a few days. They suggested several explanations as to why patients get worse during admissions, like patients’ letting go of their self-control and therefore self-harm more, patients triggering each other, loss of skills to handle emotions, and an increase in anxiety close to discharge. There were several suggested explanations of the recognized phenomenon of patients demanding compulsory care, like patients wanting to transfer responsibility to others to protect themselves from making bad decisions. The respondents described several non-medical motives for non-beneficial compulsory care, like doctors’ fears and interests and lack of outpatient resources. There were many suggestions on how care can be improved, and compulsory admissions shortened, like around three-day long voluntary admissions, better inpatient structure, and more available outpatient interventions. The patient’s interaction style, like being likeable or demanding as a patient, was thought to possibly affect care but the respondents described that it could result in either more or less care depending on context.

Table 1. Qualitative analysis of comments. See Supplementary Appendix III.

Discussion

Main findings

The main result of the study is that care providers at most psychiatric inpatient wards in Sweden find the compulsory admissions to be too long for BPD patients who self-harm and notice an increase in self-harm behaviour from admissions longer than a week. Sometimes BPD patients demand compulsory care, which can make the reduction of such care more difficult. The respondents recognised several reasons for non-beneficial compulsory admissions, like doctors’ fear of litigation/complaints and social factors like the patient’s lack of housing. To decrease the use of non-beneficial compulsory care, the respondents suggest goal-directed care planning with a discharge date set upon admission, short voluntary admissions (about three days long), focus on the patient’s agency, and more available outpatient care.

Implications

These findings imply that many BPD patients are regularly forced to receive psychiatric care that inadvertently makes them more prone to self-harming behaviour and, thus, perpetuates several of their core problems. In addition, the motives for compulsory care are not always coherent with the legal criteria for compulsory care or in the patient’s best interest. From a cost-benefit perspective, extensive hospital resources are used for patients who are not perceived to benefit from such care. To remedy the problems presented, the respondents’ comments can be used as a source when formulating clinical guidelines on when to use inpatient care and compulsory care for BPD patients, a point we elaborate on below.

Comments on the motives for practising non-beneficial compulsory care

BPD patients have a continuous pattern of recurrent self-destructive behaviour and increased suicide risk. The risk of suicidal events is the main reason for compulsory admissions of BPD patients. However, hospital care of BPD patients has no proven effect on reducing suicidal behaviour and may increase self-harm (with or without suicidal intent) – as supported by this study and previous research [Citation2,Citation4,Citation7,Citation8,Citation21]. In contrast, self-harming BPD patients seem to improve when given more agency and less psychiatric emergency care [Citation2,Citation9,Citation21]. This approach can seem counterintuitive and risky when dealing with suicidal patients, and therefore difficult for caregivers, patients, and society to accept. As a possible consequence, BPD patients still receive long compulsory admissions to reduce their suicidality, despite clinical guidelines recommending otherwise [Citation9] and hospital admissions showing no suicide-protective effect [Citation4,Citation21,Citation22].

When it comes to non-medical reasons for compulsory care, one of the main motives presented in this study is the care providers’ fear of complaints and litigation if the patient self-harms after discharge. Even if the patients may self-harm more when having long admissions, such inpatient self-harm does not seem to reflect badly on the care provider. To do more is intuitively seen as more effective than to do less, even when this is not the case. According to previous research, care providers have experienced that healthcare inspecting authorities endorse the use of compulsory admissions as a suicide preventive measure for BPD patients – and criticize when such care has not been used [Citation15]. Also, other studies have indicated that fear of litigation increases the use of non-beneficial care for BPD patients [Citation13,Citation14]. The respondents in this study described how the practice of non-beneficial compulsory admissions varied depending on whether the doctor in charge 'dared’ to discharge self-harming patients, indicating that doing what may be best for the patient puts the doctor at risk and that the care varies depending on the doctor’s courage. The consequence appears to be that the patient’s right to autonomy is regularly violated, often with negative consequences, to protect caregivers from being professionally criticised.

Non-beneficial compulsory care due to lack of housing is also debatable. Voluntary admissions for such a purpose would be more legally justified, but still problematic from a medical and ethical perspective if they increase self-harm. Drawing on the respondents’ comments, one may speculate if this can be explained by some doctors taking on a paternalist role for the patient, overriding the patient’s autonomy to improve their life in general. Even though the intentions may be good when using compulsory care as a solution to social problems, the results could be problematic in several other aspects, e.g. by increasing the risk of self-harm.

BPD patients are often troubled by feelings of abandonment, lacking self-trust, and maladaptive coping strategies – including suicidal behaviour - to manage adverse events [Citation2,Citation3]. Considering these difficulties, being relieved from their responsibility to manage negative emotions and suicidal impulses may provide a sense of security. This could explain our finding that patients sometimes demand to be taken care of by others through compulsory care. According to some respondents, it could happen as often as weekly. However, even though it may be tempting for the care provider to agree to such care, such intervention could reduce the patient’s capacity to take care of themselves and manage future crises [Citation9,Citation23]. This was further supported by the respondents’ comments, describing how the patients let go of their inner breaks when taken into compulsory care, and therefore self-harm more. The possible connection between rejecting self-responsibility and an increase in self-harm may not always be evident to either the patient or the care provider and could contribute to longer non-beneficial compulsory admissions. Notably, this type of compulsory care on the patient’s demand seems to be regularly accepted when tried in court [Citation16].

Comments on background factors

Respondents working more than 5 years in psychiatry experienced fewer benefits and more negative effects of longer admissions than a week and were more positive about shortening compulsory admissions. One can speculate on whether the nurses and psychiatric aides who are new on the job are still influenced by the generally accepted idea that hospital care reduces suicidality, while those having worked longer have had enough experience to revise their previous ideas.

What can be done?

The respondents in this study gave several practical suggestions on how to shorten compulsory admissions and improve inpatient care. The main suggestions, described under 'Main findings’ above, are supported by a previous study on hospital care for self-harming patients [Citation13]: goal-directed care planning with a discharge date set upon admission, voluntary admissions lasting for about three days, focus on the patient’s agency, and more available outpatient care. Several suggestions are also in line with the NICE guidelines for borderline personality disorder [Citation9] and previous experience from brief admissions [Citation24] and hospitalization of BPD patients [Citation2,Citation7,Citation8], suggesting short admissions and focus on the patient’s agency. These results, taken together, speak in favour of implementing the respondents’ main suggestions in clinical practice.

Currently, there is a politically sanctioned drive for establishing highly specialized care for self-harming patients in Sweden, including a few centralized hospital wards that will be able to admit patients long-term [Citation25]. The results from this study may, together with previous research, provide useful guidance when designing the work model for these units.

There seems to be a general idea in health care that compulsory inpatient care has suicide protective effects for BPD patients. This idea could perpetuate the use of non-beneficial compulsory care. To address this problem, we suggest that care providers are given more information about the possible negative effects of long admissions and compulsory care of BPD patients. Regular medical-ethical discussions in the clinic, e.g. values-based practice [Citation26], could be another means to help care providers handle complex considerations on if or when to use compulsory care.

Strength and limitations

The study conveys the experiences of healthcare providers, not the patients. Only one ward per municipality participated in the study, limiting its generalizability. On the other hand, our results are supported by previous studies on the use of compulsory care on self-harming patients in Stockholm [Citation13] and statistics on compulsory care in Sweden [Citation12]. There is reason to believe that the respondents’ observation of the detrimental effects of longer hospital stays is correct since it is supported by previous research done on inpatient care for BPD patients who self-harm when used for suicide-protective reasons [Citation2,Citation7–9].

Conclusion

The results from our study indicate that BPD patients are regularly subjected to non-beneficial compulsory care, sometimes for non-medical reasons. This study has presented several practical suggestions for improving inpatient care and reducing compulsory admissions, for example, goal-directed care planning with a discharge date set upon admission, short voluntary admissions (around 3 days long), focus on the patient’s agency, and more available outpatient care.

Ethical approval statement and patient consent statement

Ethical approval is not required for this kind of research in Sweden, according to the Swedish Ethical Review Act (2003: 460) [Citation27], since it is not invasive, is not performed with potentially harmful methods, and does not include sensitive personal data (as defined by GDPR). All participants in this study were informed in the cover letter that their participation was anonymous and voluntary (see Supplementary Appendix II). We confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

No other source material was used.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (26.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (61.1 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge all healthcare providers who accepted to participate in the study. Finally, the authors thank all the unit managers in the wards, who accepted their wards to participate in the study and helped with handing out and collecting the anonymous questionnaires.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Antoinette Lundahl

Antoinette Lundahl works at S:t Görans hospital in Stockholm as a consultant psychiatrist in a ward for patients with anxiety- and personality disorders. She is also a PhD student in medical ethics at Karolinska Institutet.

Magdalena Torenfält

Magdalena Torenfält is a medical student at Karolinska Institutet.

Gert Helgesson

Gert Helgesson and Niklas Juth are professors in medical ethics at Karolinska Institutet and Uppsala University, respectively. They both have prior experience with the methods used in this study and are supervisors to Antoinette Lundahl.

Niklas Juth

Gert Helgesson and Niklas Juth are professors in medical ethics at Karolinska Institutet and Uppsala University, respectively. They both have prior experience with the methods used in this study and are supervisors to Antoinette Lundahl.

References

- Socialstyrelsen. Samlat stöd för patientsäkerhet. Suicid och suicidförsök. [The National Board of Health and Welfare. Collected support for patient safety. Suicides and suicide attempts.] Suicid och suicidförsök – Patientsäkerhet. https://patientsakerhet.socialstyrelsen.se/risker-och-vardskador/vardskador/suicid/relsen.se

- Linehan M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993.

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th edn. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

- Chiles JA, Strosahl KD, Roberts LW. Clinical manual for the assessment and treatment of suicidal patients. 2nd revised edition. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

- NICE guidelines. Self-harm. London: The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists. 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs34/resources/selfharm-pdf-2098606243525

- Taiminen TJ, Kallio-Soukainen K, Nokso-Koivisto H, et al. Contagion of deliberate self-harm among adolescent inpatients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(2):211–217.

- Paris J. Suicidality in borderline personality disorder. Medicina. 2019;55(6):223.

- Nationella självskadeprojektet: Behandling av självskadande patienter i heldygnsvård: fynd från forskningen (National project on self-harm: Treatment of self-harming patients in inpatient care: findings from the research). Sweden. 2015. https://www.nationellasjalvskadeprojektet.se/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/supplementrapport-heldygnsvard-20150904.pdf

- NICE guidelines 2009: borderline personality disorder: treatment and management. London: The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2009. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg78/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-242147197

- Lag (1991:1128) om psykiatrisk tvångsvård (Swedish Mental Health Act). https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/lag-19911128-om-psykiatrisk-tvangsvard_sfs-1991-1128

- Regeringens proposition 1990/91:58 om psykiatrisk tvångsvård, m.m. (Swedish government’s proposition 1990/91:58 regarding compulsory care, etc.). 2022. http://data.riksdagen.se/dokument/GE0358

- Socialstyrelsens statistikdatabas (Statistics database of The National Board of Health and Welfare). Psykiatrisk tvångsvård (Psychiatric compulsory care). Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen (The National Board of Health and Welfare); 2013, 2019. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/dokument-webb/ovrigt/barn-psykiska-halsa-statistik-om-psykiatrisk-tvangsvard-enligt-lpt-2013.pdf; https://sdb.socialstyrelsen.se/if_tvangsvard/val.aspx

- Lundahl A, Helgesson G, Juth N. Hospital staff at most psychiatric clinics in Stockholm experience that patients who self-harm have too long hospital stays, with ensuing detrimental effects. Nordic J Psychiatry. 2021;76(4):287–294.

- Krawitz R, Batcheler M. Borderline personality disorder: a pilot survey about clinician views on defensive practice. Australas Psychiatry. 2006;14(3):320–322.

- Lundahl A, Helgesson G, Juth N. Psychiatrists’ motives for practising in-patient compulsory care of patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD). Int J Law Psychiatry. 2018;58:63–71.

- Lundahl A, Hellqvist J, Helgesson G, et al. Psychiatrists’ motives for compulsory care of patients with borderline personality disorder – a questionnaire study. Clinical Ethics. 2021;17:14777509211040190.

- Lundahl A, Helgesson G, Juth N. Ulysses contracts regarding compulsory care for patients with borderline personality syndrome. Clinical Ethics. 2017;12(2):82–85.

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334–340.

- Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):483–488.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112.

- Coyle TN, Shaver JA, Linehan MM. On the potential for iatrogenic effects of psychiatric crisis services: the example of dialectical behavior therapy for adult women with borderline personality disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2018; Feb86(2):116–124.

- Large MM, Chung DT, Davidson M, et al. In-patient suicide: selection of people at risk, failure of protection and the possibility of causation. BJPsych Open. 2017;3(3):102–105.

- Lundahl A, Helgesson G, Juth N. Against ulysses contracts for patients with borderline personality disorder. Med Health Care Philos. 2020;23(4):695–703.

- Helleman M, Goossens PJ, Kaasenbrood A, et al. Evidence base and components of brief admission as an intervention for patients with borderline personality disorder: a review of the literature. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2014;50(1):65–75.

- Beslut om nationell högspecialiserad vård – viss vård vid svårbehandlat självskadebeteende. [Decision on national highly specialized care – certain care for self-harm behaviour that is difficult to treat]. Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare]. 2020. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/dokument-webb/ovrigt/nationell-hogspecialiserad-vard-sjalvskadebeteende-beslut.pdf

- Fulford KW. Values-based practice: a new partner to evidence-based practice and a first for psychiatry? Mens Sana Monogr. 2008;6(1):10–21.

- Lag (2003:460) om etikprövning av forskning som avser människor (the Swedish Ethical Review Act, concerning research on human subjects). 2022. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/lag-2003460-om-etikprovning-av-forskning-som_sfs-2003-460