ABSTRACT

Although wealth concentration and large fortunes have attracted increased scholarly attention in recent decades, this work has been largely gender-blind. This study examines changes in the gender composition of global billionaires over the last 14 years (Forbes world’s billionaires list, 2010 – 2023) and asks how male and female billionaires differ in their likelihood to perpetuate their billionaire status. Between 2010 and 2023, we find a modest increase in the percentage share of female billionaires, from 9.0 to 12.8 percent. While the share of female self-made billionaires more than doubled, the share of female billionaire heirs increased only by 43 percent during the observed period, highlighting the importance to differentiate between the source of billionaires’ wealth when studying gender differences. To examine differences in the long-term perpetuation of billionaire fortunes by gender and source of wealth of billionaires, we apply survival analyses. We find that men stay on the Forbes list significantly longer than women. Overall, this study contributes to the literature on gender wealth inequalities by showing how billionaires’ wealth is structured by gender.

Introduction

The gap between the super-rich and average citizens has widened dramatically over the past 40 years due to a tremendous increase in private wealth concentration (Chancel et al. Citation2022; Piketty Citation2014). A small share of the population holds huge amounts of wealth, whereas the vast majority has no or even negative wealth holdings: The top ten percent own about three-quarters of the global wealth, while the bottom half possesses roughly two percent (Chancel et al. Citation2022). Rising wealth inequality is considered a central characteristic of contemporary capitalism (Piketty Citation2014). Although the wealthy are such a small and highly selective population, they are essential to understanding the structure, dynamics, and reproduction of economic and social inequality (Hecht Citation2017; Khan Citation2012). In more recent years, the accumulation of wealth by economic elites has received greater attention (e.g., Keister, Lee, and Yavorsky Citation2021; Keister, Thébaud, and Yavorsky Citation2022; Khan Citation2012; Sherman Citation2017). Wealth is far stronger concentrated than income (Keister, Lee, and Yavorsky Citation2021) and has, in contrast to income, specific qualities that enhance and secure economic well-being in the long term. It can be a use value, for instance in the form of homeownership, or it can provide financial income and a buffer in case of unexpected expenditures. Moreover, wealth generates social advantages for current and future generations, such as educational or occupational opportunities, political influence, and the power to shape social and cultural norms (Deere and Doss Citation2006b; Keister Citation2014; Keister and Lee Citation2017; Keister, Lee, and Yavorsky Citation2021; Page, Seawright, and Lacombe Citation2019).

We are only at the beginning of understanding who those at the top of the wealth distribution are. So far, most research on super-rich individuals has largely been gender-blind (Keister, Lee, and Yavorsky Citation2021; Keister, Thébaud, and Yavorsky Citation2022). However, taking gender into account is necessary to understand the power structures in society (Chang Citation2010). As Glucksberg (Citation2018b, 20) argues, ‘inequality is reproduced through gendered, classed, sexed relationships that stretch from individuals to families, to businesses, and to the broader social structures that exist within a capitalist society.’ Although the scholarly body on the gender wealth gap, explaining why women own less wealth in general, is nascent (e.g., Deere and Doss Citation2006a; Citation2006b; Ruel and Hauser Citation2013; Sierminska, Frick, and Grabka Citation2010), there is only very little research on those women that do belong to the top wealth holders (Adamson and Johansson Citation2021; Glucksberg Citation2018b). This is partly due to data limitations since population surveys often measure wealth at the household instead of the individual level. Furthermore, top wealth strata are often not well represented in surveys.

We help to fill this research gap by exploring changes in the share of female billionaires between 2010 and 2023. Furthermore, we examine gender differences in the perpetuation of billionaire fortunes over time, also considering whether the fortune is inherited or self-made. To this end, we analyse the richest population in the world using the Forbes world’s billionaires’ rich lists from 2010 to 2023. We created a unique dataset covering the world’s largest fortunes over the last 14 years. First, we explore the sample descriptively with regard to gender differences in shares and the source of wealth. Second, we conduct survival analyses to examine whether female or male billionaires are more likely to perpetuate their billionaire fortunes over the long term. Here, we follow the approach of Korom, Lutter, and Beckert (Citation2017) who analysed the likelihood to remain listed in the American Forbes 400 list from 1982 to 2013. Our analysis differs from this study in examining global billionaires and putting a specific focus on gender.

This study uniquely contributes to the literature on gender differences in wealth and the long-term perpetuation of large fortunes. First, by using a novel dataset based on the Forbes world’s billionaires’ rich lists, we provide descriptive insights into changes in the gendered composition of the world’s largest fortunes. We show that the share of female billionaires increased by 42 percent over the last 14 years. Second, survival analyses generate important insights into the long-term perpetuation of the world’s largest fortunes as a function of gender and source of wealth. We show that men remain on the Forbes list significantly longer than women, with male heirs having the lowest drop-out hazards and self-made women having the highest. Finally, by including all countries with at least one listed billionaire within the observed period (n = 86), this study adds to existing research on the wealth elite which mainly focuses on the US-American context (e.g., Davies-Netzley Citation1998; Kaplan and Rauh Citation2013; Keister, Lee, and Yavorsky Citation2021; Korom, Lutter, and Beckert Citation2017; Ruel and Hauser Citation2013), or other single-country studies in the Western world (e.g., Bach, Thiemann, and Zucco Citation2019; Baselgia and Martínez Citation2021). We show that there are pronounced differences in the share of female billionaires between countries. Taken together, our analysis contributes to understanding the composition of the super-rich by focusing on gender as a key element at the top of the global wealth distribution.

The remainder of this study is structured as follows. In Section 2, we elaborate on the existing literature on gender differences within wealth elites and develop our hypotheses. Section 3 describes the data and methodology, followed by descriptive and multivariable analyses of the super-rich and their gendered long-term perpetuation of wealth in Section 4, and concluding remarks in Section 5.

Theoretical Framework

The Gender Wealth Gap (at the Top)

Women possess less wealth than men, regardless of country-specific formal and informal gender equality (Deere and Doss Citation2006a; Citation2006b; Ruel and Hauser Citation2013; Sierminska, Frick, and Grabka Citation2010). This gender wealth gap is particularly pronounced in the upper wealth strata, where women are strongly underrepresented (Baselgia and Martínez Citation2021; Edlund and Kopczuk Citation2009; Keister, Thébaud, and Yavorsky Citation2022). Studies exploring structural issues related to elite mobility argue that gendered patterns generate differing mobility opportunities for women and men on their path to the economic elite (Toft and Flemmen Citation2018). These paths will result in notably different wealth portfolios for those who reach the top (Keister, Lee, and Yavorsky Citation2021). To accurately illustrate the gendered composition of the super-rich, it is crucial to understand the dynamics of gendered pathways to high wealth. There are two main paths to the top of the wealth distribution, which entail highly gendered dynamics: inheriting a large fortune or building one through entrepreneurial activity. Men are more likely to have resources from current income and businesses to save and accumulate assets. Women, on the other hand, rely more on transfers and inheritances from their family or, in most cases, from their husbands to become part of the super-rich (Edlund and Kopczuk Citation2009; Keister, Lee, and Yavorsky Citation2021; Yavorsky et al. Citation2019; Yavorsky, Keister, and Qian Citation2020). In order to achieve a position at the top of the wealth distribution, women require a much stronger socio-economic and cultural background than men (Hansen Citation2014; Vianello and Moore Citation2000). As Knowles (Citation2022, 143) argues, women often access wealth through indirect means, such as inheritance, marriage, or divorce settlements, which limits their fundamental power and reinforces subordination to men.

Historically, women’s property and inheritance rights were restricted in most countries; in some, they are still today (Beckert Citation2008; Keister, Lee, and Yavorsky Citation2021). These country-specific differences in legal regulations and their practical implications may result in strongly diverging portfolios of women and men in the respective wealth distributions. Even if legal regulations do not actively prevent women from accumulating wealth and wealth shares are divided equally between family members on paper, women are often disadvantaged in legal practice (Bessière, Gollac, and Rogers Citation2023; Knowles Citation2022; Mehrotra et al. Citation2011). Super-rich individuals may, for instance, employ a team of lawyers and tax advisors to ensure that their divorce is as advantageous as possible, a practice referred to as ‘jurisdiction shopping’ (Knowles Citation2022, 110). It involves advising clients on the most favourable countries for executing a divorce and distributing undisclosed assets among offshore accounts to prevent the former spouse from inheriting their rightful share. As the husbands usually have a better knowledge of the true extent of their wealth than their wives or lawyers, they are typically at an advantage in these proceedings (Knowles Citation2022).

Women’s access to the corporate world, and therefore to accumulating a fortune on their own, is significantly stronger restricted than their access to inherited fortunes. Despite slow and steady improvement in women’s access to top corporate positions associated with the highest incomes and generous benefits, women continue to face challenges that men do not (Adamson and Kelan Citation2019; Carli and Eagly Citation2016). Women face a labyrinth of complex challenges allowing only a small majority to advance to the top (Carli and Eagly Citation2016).Footnote1 Women’s way into the business elite seems to be much more contingent on the material, cultural, or social resources of their family of origin compared to men’s (Hansen Citation2014; Lawler Citation1999; Mavin and Grandy Citation2016).

First, entrepreneurial roles are strongly gendered. According to the expectation states theory, social beliefs about gender entail hegemonic assumptions that lead to discrimination against women by discounting their competencies (Yang and Aldrich Citation2014). The implicit ideal of a manager privileges masculine traits and behaviours, making women seem to be less suitable (Eagly and Karau Citation2002; Koenig et al. Citation2011; Mavin and Grandy Citation2016). Women are perceived to be lacking agentic qualities and to be rather kind, warm, and helpful. Becoming and being a wealthy woman requires particular discursive self-representations to balance typically masculine success story tropes and an appropriate feminine identity (Mavin and Grandy Citation2016). The continuous underrepresentation of women in leadership positions signals that these masculine ideals persist.

Second, women’s job performance is evaluated as worse compared to male peers in similar positions, which affects their likelihood to be hired or promoted into beneficial positions. This discrimination becomes particularly apparent when being evaluated by men (Koch, D’Mello, and Sackett Citation2015). Consequently, based on a UK study, men receive larger bonuses and managerial compensation that is much more performance-sensitive than that of female executives (Kulich et al. Citation2011). In their study on entrepreneurial teams in the US, Yang and Aldrich (Citation2014) find that men have a significantly higher chance of becoming the leader in mixed-gender entrepreneurial teams during the process of the formation of new organisations, even after controlling for merit and human capital.

Third, women have less access to powerful sponsors and formal or informal networks (Davies-Netzley Citation1998; Hewlett Citation2013). Among entrepreneurs, men continue to have greater access to financial capital to start and grow their businesses (Yang and Aldrich Citation2014). Davies-Netzley (Citation1998) interviewed female and male CEOs in California to find that, whereas men stress individualism as an explanation for success, women emphasise social networks and peer similarities for succeeding in elite positions. With regard to informal networks, private members clubs frequented by the wealth elite often exclude women from membership and may only invite them as guests in order to attract more male attendees to their events (Glucksberg Citation2018a; Knowles Citation2022). Thus, even after gaining access to elite positions despite all obstacles, women face specific pressures, such as high levels of visibility, isolation, and gendered role stereotypes (Davies-Netzley Citation1998; Kanter Citation2010).

Finally, women still have greater childcare and domestic responsibilities, leading them to interrupt or quit their careers. The requirements and structures in highly paid jobs, such as overwork, the willingness to travel, or constant availability, favour a stereotypically male biography (Carli and Eagly Citation2016; Keister, Thébaud, and Yavorsky Citation2022). Professional women are less likely to find a partner who stays home, which often leads them to quit or switch to lower-paying female-dominated occupations (Lovejoy and Stone Citation2012). Entrepreneurial women opt out in far greater numbers than men (Stone Citation2007). This is particularly prevalent among the super-rich: Very wealthy couples are significantly more likely to have a traditional labour division of a male breadwinner and a female homemaker than comparable couples in lower economic strata (Bessière, Gollac, and Rogers Citation2023; Knowles Citation2022; Yang and Aldrich Citation2014; Yavorsky et al. Citation2019; Yavorsky, Keister, and Qian Citation2020).

The prevalence of inherited versus self-made wealth is strongly linked to the country's context. Whereas in China or the US self-made wealth is dominant (Freund and Oliver Citation2016; Khan Citation2012; Korom, Lutter, and Beckert Citation2017), most European countries have a higher share of heirs among their wealth elite (Baselgia and Martínez Citation2021; Freund and Oliver Citation2016). Following Edlund and Kopczuk’s (Citation2009) assumption that both women and men inherit large fortunes, but men are much more likely than women to accumulate wealth themselves, a rising share of self-made wealth among the super-rich would indicate a declining share of women. However, there are some reasons to question this assumption. Despite numerous structural barriers, gender differences in processes that lead to elite status have changed over time. Women’s labour force participation and their educational and occupational attainment have been increasing in wealthy democracies (Davidson and Burke Citation2011; Keister Citation2014; Mavin and Grandy Citation2016). In many cases, the share of women in higher education is now equal to or greater than that of men. Moreover, women tend to enter the workplace at similar levels to men, with similar credentials and expectations (Davidson and Burke Citation2011). Increasing industrialisation and a growing service and public sector have created new opportunities for women. In addition, family-friendly policies such as parental leave or the possibility to work part-time have been introduced in many countries (Carli and Eagly Citation2016).

Moreover, although rather slowly, women are increasingly present in managerial positions. Today, there are more female leaders than ever. Leadership positions are an important source of elite power with women’s voices being increasingly represented in large organisations (Keister, Thébaud, and Yavorsky Citation2022). Women’s economic self-reliance and bargaining power have increased in recent decades, leading to women being increasingly integrated into managerial occupations, although not in the highest positions (England, Levine, and Mishel Citation2020). Advances that women have made and changes in the perception of leadership have eased women’s pathways to advancement. In Norway, for instance, the share of women has steadily increased within the top one and the top 0.1 percent of the wealth distribution between 1993 and 2010 (Hansen Citation2014). Attitudes toward working women, particularly those with children, as well as political and legal initiatives, support this trend (Davidson and Burke Citation2011). In particular, female upward mobility also becomes apparent in public attitudes toward female leaders. Whereas female leadership quality was perceived as lower relative to men’s, female CEOs are now perceived as being equally, if not more effective than men today (Paustian-Underdahl, Walker, and Woehr Citation2014). Therefore, we assume:

H1: Gender differences among billionaires decrease over time. This decrease is stronger among self-made billionaires.

Long-Term Perpetuation of Wealth

Today, women start more businesses than ever, but still at lower rates than men. However, even if women establish their own fortune through entrepreneurial activities, they are more at risk to lose their fortune compared to their male peers. Women persist in new ventures for shorter periods than their male counterparts (Keister, Lee, and Yavorsky Citation2021). According to the ‘glass cliff’ hypothesis (Ryan and Haslam Citation2005), women in high entrepreneurial positions are offered especially precarious and risky positions with greater potential for failure. This hypothesis finds support in prior research conducted in the US (Adams, Gupta, and Leeth Citation2009) and in the UK (Mulcahy and Linehan Citation2014). Regarding highly paid managerial positions as one precondition to building up a billionaire fortune, those disrupted career paths may hamper the long-term persistence of large fortunes held by females.

In the context of inherited fortunes, the perpetuation of wealth across family dynasties passing relies on established institutions of wealth perpetuation, such as family constitutions, family trust companies, family foundations, and family offices (Beckert Citation2022). These institutions are, however, often gendered (Bessière, Gollac, and Rogers Citation2023). Typically, fortunes inherited by women were previously owned by men (Edlund and Kopczuk Citation2009), which places men in a privileged position to seek professional advice on wealth preservation and transfer. Conversely, women’s persistent reliance on men for accessing high wealth (e.g., through inheritance or marriage) leaves them in a subordinate position that limits their ability to negotiate and exert control over wealth shares (Knowles Citation2022, 143).

The entrepreneurial sphere is more dynamic compared to established, dynastic fortunes. Explanations referring to global changes in the sectoral composition of markets highlight the disproportionate success and wealth accumulation of highly skilled ‘superstars’ (Kaplan and Rauh Citation2013; Korom, Lutter, and Beckert Citation2017). Using the annual American Forbes 400 rich lists (1982–2013), Korom, Lutter, and Beckert (Citation2017) show that despite a growing share of entrepreneurial wealth, those with inherited wealth are significantly more likely to remain listed in the long term. Inherited fortunes, thus, appear to be significantly more stable, even in economies with a more dynamic composition of the wealth elite, such as the US. That is why we expect that independent of the source of wealth, male fortunes persist longer than female ones. When accounting for the source of wealth, female self-made fortunes are expected to persist for a shorter term than self-made male and inherited fortunes. We hypothesise:

H2: Male billionaire fortunes persist for longer periods than female fortunes. This is especially the case for billionaires with self-made wealth.

Data and Methods

Data

Data availability is a major challenge in studying the super-rich. Administrative tax data and traditional surveys have considerable shortcomings in empirically capturing this population, especially when exploring the international wealth elite. Therefore, prior studies often relied on rich lists when studying the super-rich (e.g., Bach, Thiemann, and Zucco Citation2019; Beckert Citation2022; Freund and Oliver Citation2016; Korom, Lutter, and Beckert Citation2017). Since 1987, Forbes magazine publishes its annual list of billionaires, including all individuals with an estimated fortune of at least one billion dollars by March of each year. Their net wealth is estimated by journalists based on shareholder information, company financial statements, current exchange rates, and meetings with candidates (Bach, Thiemann, and Zucco Citation2019). The financial figures are converted from the respective currencies to improve comparability. However, they do not account for country-specific inflation rates which weakens the informative value of wealth estimates when applying a global perspective. Further, it is important to recognise that it is difficult to generate a complete picture of a billionaire’s total wealth, thus, all figures are provided as estimates only. Notwithstanding these limitations, the Forbes billionaires rich list has the advantage of offering the most extensive series of billionaires by name. It provides the best available profile of the wealthiest individuals around the world by tracking their fortunes on an annual basis and examining in depth who remains above the one-billion-dollar threshold and who does not.

To analyse gender differences among the world’s billionaires, we use the Forbes lists of billionaires from 2010 to 2023. Thereby, we generate a longitudinal dataset covering 14 years, containing 4,230 billionaires in 26,715 person-years. 38 entries list couples or families instead of an individual. Because we cannot assign a gender to those entries, our analysis sample comprises 4,192 persons and 26,479 person-years.

Analysis Strategy and Data Preparation

This study has two empirical objectives. First, we examine changes in the share of female billionaires over time. To that end, we descriptively study the development of the number of female and male billionaires over time. Furthermore, we provide a brief insight into international variations in the share of female billionaires.

The second objective is to assess the gender-specific long-term perpetuation of inherited and self-made billionaire fortunes. For this purpose, we conduct survival analyses, a method that is applied in a variety of scientific disciplines.Footnote2 Indeed, prior research on wealth elites has already made use of survival analysis to examine the number of years a person is listed on a US rich list (Korom, Lutter, and Beckert Citation2017). Applying survival analyses is used to examine the time it takes for an event of interest to occur (Mills Citation2011), which, in our case, is the year in which a billionaire drops off the Forbes list. The goal is to estimate the probability of dropping off the list at a certain point in time and to identify the factors that may be related to this probability. We argue that listing as a Forbes billionaire signals status and power in addition to mere economic standing. Thus, even if dropping off the list does clearly not mean that the individual enters poverty it might signal a loss in status and power. Therefore, we consider it relevant to examine gender differences in the duration of staying within the top echelon of the world’s wealth distribution.

We now describe the variables used in this study. The two core indicators are the billionaires’ gender and their source of wealth, both measured as binary. The variable female takes the value 1 if the billionaire is a woman and 0 if it is a man. The variable self-made indicates whether the billionaires’ wealth is self-made (1) or inherited (0). As control variables, we use the billionaires’ age, amount of wealth, sector of business, continent of residence, and a variable indicating whether the billionaire is deceased. The age variable is based on the billionaires’ birth years. If the birth year could not be identified, the average age of billionaires of the same gender and source of wealth was applied (1.8 percent of person-years).Footnote3 While younger billionaires may benefit from digital knowledge and opportunities, older ones may have had longer careers or built their fortunes in traditional fields, such as the resource-related sector (Korom, Lutter, and Beckert Citation2017). That is why we include a linear and squared age term. We further control for the level of wealth. We adjusted the wealth measures for inflation based on the US Bureau of Labor Statistics March Consumer Price Index (2023) so that all financial data are provided in 2023 constant US dollars. The hazard of dropping from the list might be related to the amount of wealth as it determines the distance to the one-billion-dollar threshold. To account for the skewness of wealth data and potential non-linearity, we use the logarithm of the amount of wealth. By adopting the coding scheme by Kaplan and Rauh (Citation2013) and Korom, Lutter, and Beckert (Citation2017), we identify the sector in which the wealth of each individual originated, classified into six categories (resource-related, new, non-tradable, financial, tradable, and diversified). Including this variable controls for the impact of growing or declining industries. Because the billionaires in our sample are located in 86 different countries, we control for the continent to account for geographical locations, with North America as reference category. Last we included a variable indicating if an individual is deceased because we coded death not as a drop-out.Footnote4

Results

Women’s Share in Billionaire Wealth

We start by giving an overview of between-country variations in the share of female billionaires. presents the ten countries with the most billionaires. Almost half of them originate from the US and China. The gender composition of the top wealth strata varies greatly across countries. For instance, about one-quarter of Germany’s, Brazil’s, or Italy’s billionaires are female whereas Russia’s largest fortunes are almost exclusively held by men. In most countries, the share of women among self-made billionaires is significantly smaller than the share of women among billionaires with inherited wealth. Interestingly, the opposite is the case in the UK.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics on the top ten countries with the most billionaires.

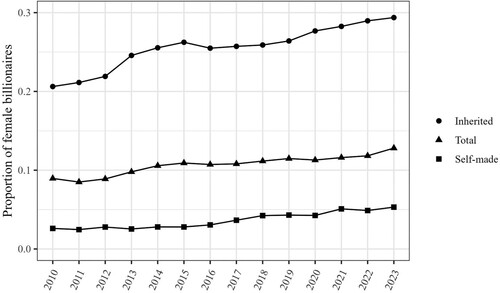

We now turn to examine changes in women’s share in billionaires’ wealth over time. For this purpose, we pool all countries. depicts the share of female billionaires among all billionaires over time. We see a slight increase in the share of female billionaires from 9.0 to 12.8 percent between 2010 and 2023. This corresponds to a growth of 3.8 percentage points, or a 42 percent increase. This finding provides support for H1, expecting an increase in the share of women among the world’s billionaires over time. If we differentiate between the source of wealth (inherited versus self-made), we learn that the share of female billionaires is much higher for inherited wealth compared to self-made wealth. In addition, the share of female billionaires among heirs experienced a steeper rise, going from 20.6 to 29.4 percent (8.8 percentage points). This suggests that the inheritance of wealth plays a significant role in increasing the representation of women among billionaires. In contrast, the increase in the share of female self-made billionaires was more modest, rising from 2.6 to 5.3 percent (2.7 percentage points).

However, it is also important to examine the relative increase in the share of female billionaires. While the increase in the share of female heirs is comparatively lower at 43 percent, the share of female self-made billionaires more than doubles between 2010 and 2023, with a 104 percent increase. Accordingly, our findings support H1, expecting that gender differences decrease to a stronger degree among self-made billionaires. Although women’s way into business, and, therefore, to self-made wealth seems to remain much more restricted than their access to inherited wealth (Edlund and Kopczuk Citation2009; Keister, Lee, and Yavorsky Citation2021; Yavorsky et al. Citation2019; Yavorsky, Keister, and Qian Citation2020), women who built their fortunes themselves experienced significant progress and seemed to close the gender gap to a greater extent during the observed period.

Gender-Specific Perpetuation of Billionaire Fortunes

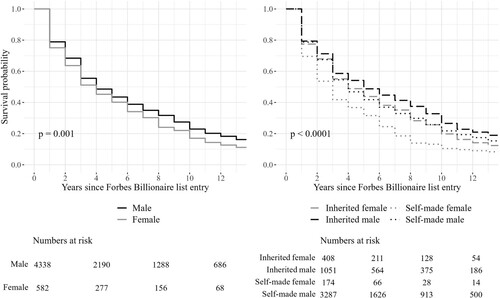

Are there gender differences in the number of years being listed in the Forbes billionaire ranking for inherited and self-made billionaires? depicts Kaplan Meier Curves and the number-at-risk table to compare the survivor curves of female and male billionaires in general, and female heirs, male heirs, female self-made, and male self-made billionaires in particular. The group differences are statistically significant.Footnote5 The five-year probability of survival is higher for male billionaires (44 percent) than for females (40 percent). The five-year probability of survival separated by gender and by the source of wealth is between 32 (self-made female) and 49 percent (inherited male). According to , there are notable gender differences in the length of time a billionaire remains on the list, with male billionaires remaining listed longer than females. These gender differences in long-term wealth perpetuation are more pronounced among self-made billionaires.

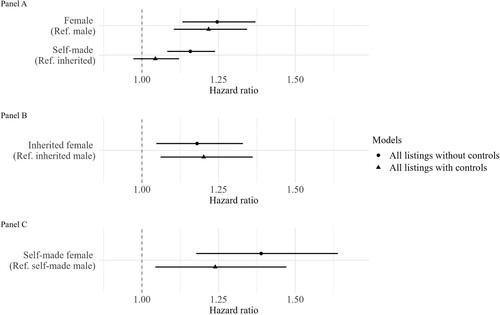

For a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics within top wealth, we analyse the factors that relate to the duration of staying listed as billionaires. presents the results of the Cox proportional hazards regressions.Footnote6 For the full regression output see Table A2 in the Supplemental Material. The coefficient plot in represents two models applied to different samples of billionaires: first, we conduct survival analyses on the total sample (Panel A), followed by analyses on sample subsets categorised by the different sources of wealth, namely, inheritance (Panel B) and self-made wealth (Panel C). The first model includes only the main variables gender and source of wealthFootnote7 without further controls. It examines the hazard ratios (HR) to drop off the list for female billionaires compared to male billionaires, and the hazard ratios for self-made billionaires compared to those with inherited wealth. The second model includes the control variables mentioned above.

Figure 3. Cox proportional hazards regression coefficients.

Note: N = 4,920 listings (recurrent drop-outs). 95% confidence intervals are shown.

The coefficient plot provides insights into the relationship between gender as well as the source of wealth and the likelihood for billionaires to drop off the Forbes list. Panel A shows the main effects of gender and source of wealth in the total sample. Panel B and C focus on gender differences in the subsample of inherited and self-made billionaires, respectively. More specifically, Panel B displays the probability of female heirs dropping off the list copmared to male heirs, while Panel C examines gender differences in the hazard ratios among self-made billionaires.

In the following, we interpret the coefficients in Panel A. Female billionaires have a 1.25 greater chance of drop-out than men (p < 0.001), even after including the control variables (HR = 1.22; p < 0.001). This finding supports H2, expecting that male billionaires tend to remain listed for longer periods compared to females. Since the coefficient remains significant even after considering various control variables, this finding highlights the significant role of gender in the long-term perpetuation of large fortunes. Thus, our results indicate that women not only encounter significant barriers in accessing high wealth, but they also have a higher likelihood of losing it over time. Billionaires with self-made wealth drop off the list with a 1.16 times higher chance compared to those with inherited wealth (p < 0.001). However, this difference loses statistical significance after including the control variables (p = 0.237).

Panel B displays the gendered drop-out hazards exclusively for billionaires with inherited wealth. Female heirs have a significantly higher likelihood to drop off the Forbes list compared to their male counterparts. More specifically, they are 1.18 times more likely to lose their billion-dollar fortune at a given point in time than male heirs (p = 0.007). These hazard ratios increase even slightly after accounting for the control variables (HR = 1.20, p = 0.004). Accordingly, gender seems to play a significant role in the long-term perpetuation of inherited wealth.

Panel C shows the gendered hazard ratios among self-made billionaires. Again, women are significantly more likely to drop off the Forbes list compared to men: female self-made billionaires are 1.39 times as likely to fall from the list compared to males (p < 0.001). The effect size decreases, however, when adding the controls: females are 1.24 times as likely to drop off the list compared to male self-made billionaires (p = 0.014). Based on these hazard ratios, the gender differences seem to be more pronounced among self-made billionaires than among heirs. However, in the models with control variables, the gender differences among self-made billionaires and among heirs do not seem to differ much. We cannot finally test these group-based gender differences in our models, because we do not test these coefficients against each other in one model. Consequently, based on the empirical evidence, H2 is only partially supported. Male billionaire fortunes persist for longer periods than female fortunes but we cannot clearly state that those gender differences are more pronounced among self-made billionaires.

Conclusion

Despite increasing academic and public attention to extreme wealth concentration, we only know little about the role of gender at the top of global wealth. To help to fill this research gap, we have analysed the Forbes world’s billionaires’ rich lists from 2010 to 2023, including the world’s richest individuals. These data uniquely allow for a gendered examination of the super-rich. First, this study descriptively explored variations in the share of female billionaires between countries and the changes in the share of female billionaires over time. Second, we conducted a survival analysis to assess gender and source of wealth differences in the long-term perpetuation of billion-dollar fortunes in order to assess who is more likely to maintain their wealth and the corresponding privileges.

The key findings of this study are as follows: The share of female billionaires varies across countries, source of wealth, and over time. The female share is higher among heirs compared to self-made billionaires because women encounter significant barriers in their pursuit of wealth through entrepreneurial activities, experiencing greater difficulty compared to their male counterparts. The barriers they face can range from limited access to financial resources and networks to societal biases and stereotypes (Hewlett Citation2013; Mavin and Grandy Citation2016). These factors contribute to a lower representation of women among self-made billionaires. While both groups, namely billionaires with inherited and self-made wealth, experienced an increase in their female share from 2010 to 2023, the growth observed among heirs was more substantial when considering the absolute number of female billionaires. However, the rate of increase is more pronounced in relative terms among self-made billionaires.

Regarding the long-term perpetuation of billionaire fortunes, our findings indicate that women are more likely to fall off the Forbes list compared to men, regardless of their source of wealth and even after accounting for various controls. This result highlights the central role of gender with regard to the long-term perpetuation of billionaire fortunes. Women who do overcome numerous formal and informal barriers and succeed in accumulating wealth, either through inheritance or through entrepreneurial activities, are confronted with a high likelihood to lose their fortune again. This finding sheds light on the complex dynamics surrounding gender, entrepreneurship, and wealth accumulation.

This study has certain limitations. Although rich lists are the best available data source to empirically assess the world’s wealth elite, we must bear in mind that it is impossible to provide a comprehensive and complete picture of a billionaire’s total wealth. Although we controlled for dollar inflation, the financial data do not account for country-specific inflation trends (Furth Citation2017). Thus, especially the financial figures must be regarded as estimates, considering this inherent uncertainty. The Forbes magazine itself must be criticised for not being a neutral data source. Rather, the magazine is characterised by an ideological preference for entrepreneurs (Korom, Lutter, and Beckert Citation2017). Furthermore, apart from the data source, the binary variable indicating the source of wealth discards potential variations in the billionaires’ social background. Accounting for the relative affluence before becoming a billionaire would enhance the data and enable an even better description of the super-rich. Regarding our survival analyses, we must keep in mind that falling off the Forbes list does clearly not imply being poor afterward. Rather, the billionaires usually ‘only’ become multimillionaires (Korom, Lutter, and Beckert Citation2017).

The results of this study highlight the enduring importance of gender in shaping the social order by focusing on the most extreme end of the wealth distribution. While there appears to be a gradual increase in the representation of female billionaires, the barriers restricting their access to high levels of wealth persist, reinforcing privileged positions held by men. Despite ongoing efforts to support female entrepreneurs, men continue to dominate the most economically advantageous positions. The results shed light on the structural exclusion of women from positions of power and raise critical questions about gender wealth inequality. It is essential to examine the broader systems and structures that perpetuate gender disparities and concentrate wealth in the hands of a few.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (203.3 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study will be made openly available in OSF at https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/yekqx.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Emma Ischinsky

Emma Ischinsky is a PhD student in the research group ‘Wealth and Social Inequality’ at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies in Cologne, Germany. In her PhD she studies how the wealthy and their interests are portrayed in German media, considering also the role of gender. In prior research she examined the historical origins of the super-rich in Germany.

Daria Tisch

Daria Tisch is a senior researcher in the research group ‘Wealth and Social Inequality’ at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies in Cologne, Germany. Her current research field is wealth and the family, focusing on gender inequality and intergenerational transfers at the top of the wealth distribution. She has previously published articles on this topic in journals such as Journal of Marriage and Family, Socio-Economic Review, European Sociological Review, and European Journal of Population.

Notes

1 Carli and Eagly (Citation2016) introduce the metaphor of a ‘labyrinth’ as a contrast to the ‘glass ceiling’ or the ‘sticky floor’ to describe women’s barriers to corporate leadership.

2 Please note that the analysis strategy and data preparation is described in relatively short terms in this chapter. For readers who are more familiar with these concepts we provide a more detailed description in the Supplemental Material.

3 Mean age in years: self-made male 63.7; inherited male 66.5; self-made female 60.9; inherited female 63.2.

4 Table A1 in the Supplemental Material summarises descriptive statistics of the variables in the models.

5 Difference between male and female: chi-square statistics = 11.2, p < 0.001.

Difference between female heirs, male heirs, female self-made and male self-made: chi-square statistics = 36.5, p < 0.001.

6 Table A3 (total sample), Table A4 (only inherited), Table A5 (only self-made), and Figure A1 in the Supplemental Material provide the Cox regression results with further robustness checks: only including the first listing of a billionaire and excluding recurrent entries (F), including only those individuals who were first listed after 2010 (A), and controlling for time-dependent variables (T).

7 Source of wealth is only included in the first panel since the outputs in the second and third panel are already split by source of wealth. Panel B and C only show the hazard ratios of the gender variable.

References

- Adams, Susan M., Atul Gupta, and John D. Leeth. 2009. “Are Female Executives Over-Represented in Precarious Leadership Positions?” British Journal of Management 20 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2007.00549.x.

- Adamson, Maria, and Marjana Johansson. 2021. “Writing Class In and Out: Constructions of Class in Elite Businesswomen’s Autobiographies.” Sociology 55 (3): 487–504. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038520962393.

- Adamson, Maria, and Elisabeth K. Kelan. 2019. ““Female Heroes”: Celebrity Executives as Postfeminist Role Models.” British Journal of Management 30 (4): 981–996. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12320.

- Bach, Stefan, Andreas Thiemann, and Aline Zucco. 2019. “Looking for the Missing Rich: Tracing the Top Tail of the Wealth Distribution.” International Tax and Public Finance 26 (6): 1234–1258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-019-09578-1.

- Baselgia, Enea, and Isabel Z. Martínez. 2021. “Tracking the Super-Rich: What Can We Learn from Swiss Rich Lists?”.

- Beckert, Jens. 2008. Inherited Wealth. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691187402.

- Beckert, Jens. 2022. “Durable Wealth: Institutions, Mechanisms, and Practices of Wealth Perpetuation.” Annual Review of Sociology 48 (1): 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-030320-115024.

- Bessière, Céline, Sibylle Gollac, and Juliette Rogers. 2023. The Gender of Capital: How Families Perpetuate Wealth Inequality. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Carli, Linda L., and Alice H. Eagly. 2016. “Women Face a Labyrinth: An Examination of Metaphors for Women Leaders.” Gender in Management: An International Journal 31 (8): 514–527. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-02-2015-0007.

- Chancel, Lucas, Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman. 2022. World Inequality Report 2022. World Inequality Lab.

- Chang, Mariko Lin. 2010. Shortchanged: Why Women Have Less Wealth and What Can Be Done About It. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Davidson, Marilyn J., and Ronald J. Burke. 2011. Women in Management Worldwide: Progress and Prospects. 2nd ed. Farnham, Surrey, VT, England Burlington: Gower Pub.

- Davies-Netzley, Sally Ann. 1998. “Women above the Glass Ceiling: Perceptions on Corporate Mobility and Strategies for Success.” Gender & Society 12 (3): 339–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243298012003006.

- Deere, Carmen Diana, and Cheryl R. Doss. 2006a. Gender and the Distribution of Wealth in Developing Countries. Helsinki: UNU WIDER.

- Deere, Carmen Diana, and Cheryl R. Doss. 2006b. “The Gender Asset Gap: What Do We Know Any Why Does It Matter?” Feminist Economics 12 (1–2): 1–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545700500508056.

- Eagly, Alice H., and Steven J. Karau. 2002. “Role Congruity Theory of Prejudice toward Female Leaders.” Psychological Review 109 (3): 573–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573.

- Edlund, Lena, and Wojciech Kopczuk. 2009. “Women, Wealth, and Mobility.” American Economic Review 99 (1): 146–178. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.99.1.146.

- England, Paula, Andrew Levine, and Emma Mishel. 2020. “Progress toward Gender Equality in the United States Has Slowed or Stalled.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (13): 6990–6997. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1918891117.

- Freund, Caroline, and Sarah Oliver. 2016. “The Origins of the Superrich: The Billionaire Characteristics Database.” Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper 16 (1): 1–30.

- Furth, Salim. 2017. “Measuring Inflation Accurately.” The Heritage Foundation 3213: 1–27.

- Glucksberg, Luna. 2018a. “Gendering the Elites. An Ethnographic Approach to Elite Women’s Lives and the Reproduction of Inequality.” In New Directions in Elite Studies, edited by Olav Korsnes, 227–243. Routledge Advances in Sociology 237. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Glucksberg, Luna. 2018b. “A Gendered Ethnography of Elites.” Focaal 2018 (81): 16–28. https://doi.org/10.3167/fcl.2018.810102.

- Hansen, M. N. 2014. “Self-Made Wealth or Family Wealth? Changes in Intergenerational Wealth Mobility.” Social Forces 93 (2): 457–481. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sou078.

- Hecht, Katharina. 2017. A Sociological Analysis of Top Incomes and Wealth. A Study of How Individuals at the Top of the Income and Wealth Distributions Perceive Income Inequality. London: London School of Economics.

- Hewlett, Sylvia Ann. 2013. (Forget a Mentor) Find a Sponsor: The New Way to Fast-Track Your Career. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press.

- Kanter, Rosabeth Moss. 2010. Men and Women of the Corporation. Nachdr. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Kaplan, Steven N, and Joshua D Rauh. 2013. “Family, Education, and Sources of Wealth among the Richest Americans, 1982–2012.” American Economic Review 103 (3): 158–162. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.3.158.

- Keister, Lisa A. 2014. “The One Percent.” Annual Review of Sociology 40 (1): 347–367. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-070513-075314.

- Keister, Lisa A., and Hang Young Lee. 2017. “The Double One Percent: Identifying an Elite and a Super-Elite Using the Joint Distribution of Income and Net Worth.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 50 (August): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2017.03.004.

- Keister, Lisa A., Hang Young Lee, and Jill E. Yavorsky. 2021. “Gender and Wealth in the Super Rich: Asset Differences in Top Wealth Households in the United States, 1989–2019.” Sociologica 15 (2): 25–55. https://doi.org/10.6092/ISSN.1971-8853/12394.

- Keister, Lisa A., Sarah Thébaud, and Jill E. Yavorsky. 2022. “Gender in the Elite.” Annual Review of Sociology 48 (1): 149–169. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-020321-031544.

- Khan, Shamus Rahman. 2012. “The Sociology of Elites.” Annual Review of Sociology 38 (1): 361–377. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145542

- Knowles, Caroline. 2022. Serious Money: Walking Plutocratic London. Dublin: Allen Lane an imprint of Penguin Books.

- Koch, Amanda J., Susan D. D’Mello, and Paul R. Sackett. 2015. “A Meta-Analysis of Gender Stereotypes and Bias in Experimental Simulations of Employment Decision Making.” Journal of Applied Psychology 100 (1): 128–161. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036734.

- Koenig, Anne M., Alice H. Eagly, Abigail A. Mitchell, and Tiina Ristikari. 2011. “Are Leader Stereotypes Masculine? A Meta-Analysis of Three Research Paradigms.” Psychological Bulletin 137 (4): 616–642. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023557.

- Korom, Philipp, Mark Lutter, and Jens Beckert. 2017. “The Enduring Importance of Family Wealth: Evidence from the Forbes 400, 1982 to 2013.” Social Science Research 65 (July): 75–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2017.03.002.

- Kulich, Clara, Grzegorz Trojanowski, Michelle K. Ryan, S. Alexander Haslam, and Luc D. R. Renneboog. 2011. “Who Gets the Carrot and Who Gets the Stick? Evidence of Gender Disparities in Executive Remuneration.” Strategic Management Journal 32 (3): 301–321. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.878.

- Lawler, Steph. 1999. ““Getting Out and Getting Away”: Women’s Narratives of Class Mobility.” Feminist Review 63 (1): 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/014177899339036

- Lovejoy, Meg, and Pamela Stone. 2012. “Opting Back In: The Influence of Time at Home on Professional Women’s Career Redirection after Opting Out.” Gender, Work & Organization 19 (6): 631–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2010.00550.x.

- Mavin, Sharon, and Gina Grandy. 2016. “Women Elite Leaders Doing Respectable Business Femininity: How Privilege Is Conferred, Contested and Defended through the Body: Women Elite Leaders Doing Respectable Business Femininity.” Gender, Work & Organization 23 (4): 379–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12130.

- Mehrotra, Vikas, Randall Morck, Jungwook Shim, and Yupana Wiwattanakantang. 2011. “Adoptive Expectations: Rising Sons in Japanese Family Firms.” NBER Working Paper Series 16874: 1–42.

- Mills, Melinda. 2011. Introducing Survival and Event History Analysis. Los Angeles, Calif.;. London: SAGE.

- Mulcahy, Mark, and Carol Linehan. 2014. “Females and Precarious Board Positions: Further Evidence of the Glass Cliff: Females and Precarious Board Positions.” British Journal of Management 25 (3): 425–438. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12046.

- Page, Benjamin I., Jason Seawright, and Matthew J. Lacombe. 2019. Billionaires and Stealth Politics. Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press.

- Paustian-Underdahl, Samantha C., Lisa Slattery Walker, and David J. Woehr. 2014. “Gender and Perceptions of Leadership Effectiveness: A Meta-Analysis of Contextual Moderators.” Journal of Applied Psychology 99 (6): 1129–1145. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036751.

- Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674369542.

- Ruel, Erin, and Robert M. Hauser. 2013. “Explaining the Gender Wealth Gap.” Demography 50 (4): 1155–1176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0182-0.

- Ryan, Michelle K., and S. Alexander Haslam. 2005. “The Glass Cliff: Evidence That Women Are Over-Represented in Precarious Leadership Positions.” British Journal of Management 16 (2): 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2005.00433.x.

- Sherman, Rachel. 2017. Uneasy Street: The Anxieties of Affluence. Princeton: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400888504.

- Sierminska, Eva M., Joachim R. Frick, and Markus M. Grabka. 2010. “Examining the Gender Wealth Gap.” Oxford Economic Papers 62 (4): 669–690. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpq007.

- Stone, Pamela. 2007. “The Rhetoric and Reality of “Opting Out”.” Contexts 6 (4): 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1525/ctx.2007.6.4.14.

- Toft, Maren, and Magne Flemmen. 2018. “The Gendered Reproduction of the Upper Class.” In New Directions in Elite Studies, edited by Olav Korsnes, Johan Heilbron, Johs Hjellbrekke, Felix Bühlmann, and Mike Savage, 113–133. New York: Routledge.

- Vianello, Mino, and Gwen Moore, eds. 2000. Gendering Elites: Economic and Political Leadership in 27 Industrialised Societies. Advances in Political Science. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: New York: Macmillan Press ; St. Martin’s Press.

- Yang, Tiantian, and Howard E. Aldrich. 2014. “Who’s the Boss? Explaining Gender Inequality in Entrepreneurial Teams.” American Sociological Review 79 (2): 303–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122414524207.

- Yavorsky, Jill E., Lisa A. Keister, and Yue Qian. 2020. “Gender in the One Percent.” Contexts 19 (1): 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536504220902196.

- Yavorsky, Jill E., Lisa A. Keister, Yue Qian, and Michael Nau. 2019. “Women in the One Percent: Gender Dynamics in Top Income Positions.” American Sociological Review 84 (1): 54–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122418820702.