ABSTRACT

The starting point of conversation analytical research on psychotherapy was in Kathy Davis’s work on problem reformulations in the mid 1980s. Since then there has been a growing body of analysis of psychotherapy, based on the close, sequential relations between adjacent utterances. Through examples drawn from CA studies on psychotherapy in the past decade, this review shows that sequential relations between utterances enable a process of transformation of experience. This process pertains to referents, emotion, and momentary relations between the therapist and the client. The utterance-by-utterance transformation contributes to the process of change in more macroscopic time, spanning the continuum of psychotherapeutic sessions. The recent developments of CA research on psychiatric consultants will also be discussed. Data are in Finnish and English.

Conversation analytical research on psychotherapy has a double task: On one hand, it shows how the machinery of interaction is adapted to serve the institutional tasks of therapists and clients, and on the other, it shows how the process of emotional and cognitive change takes place in and through the interactions between the therapist and the client. In this review, I will discuss the ways in which CA has dealt with both questions. Alongside psychotherapy proper, psychiatric consultations have in recent years become a topic of conversation analytical studies; at the end of the review, I will also discuss that emergent field.

The double task of CA in research on psychotherapy: Overview and background

The history of conversation analytical research on psychotherapy has in recent years been described in other outlets (Peräkylä et al., Citation2008a; Peräkylä, Citation2012); a rather short account is sufficient here. The origin of qualitive empirical interaction research on psychotherapy can be traced back to the work of Pittenger, Hockett, and Danehy (Citation1960). They presented a detailed account on the first five minutes of a psychotherapeutically oriented psychiatric interview. While conversation analysis did not exist as a method at the time, the concern for linguistic detail (lexical choice and prosody) and interactional meanings of actions justify seeing their work as an antecedent to CA studies of psychotherapy. The same is true regarding Scheflen’s (Citation1973) work on interactional uses of body posture and body movement during psychotherapy sessions, as well as Labov and Fanshel’s (Citation1977) work on speech acts in psychotherapy interaction. Labove and Fanshel were important also in depicting the organization of knowledge and ownership of experience in psychotherapy.

While Sacks used group therapy sessions as data in some of his work, he did not investigate them from the point of view of therapeutic practice but rather as examples of generic properties of interaction. It was Kathy Davis (Citation1986) who for the first time used CA methods to investigate practices that are central in psychotherapy in her case problem reformulation. After Davis’s trailblazing work, it took another 15 years before CA research on psychotherapy started to proliferate through the work of many European and American researchers. The field was solidified by the collection Conversation Analysis and Psychotherapy (Peräkylä, Citation2008b), which brought together some of the main projects at the time. Since then, the study of emotion, empathy, and affiliation have become even more central in conversation analysis of psychotherapy (see, e.g., Voutilainen et al., Citation2010a; Ekberg, Shaw, Kessler, Malpass, & Barnes, Citation2016; Muntigl & Horvath, Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Muntigl, Knight, Watkins, Horvath, & Angus, Citation2013; Weiste & Peräkylä, Citation2014). Furthermore, conversation analytical research is increasingly addressing questions and concerns of clinical relevance (see, e.g., Buchholtz, Spiekermann, & Kächele, Citation2015; Buchholz & Kächele, Citation2017; Lepper, Citation2009; Sutherland, Peräkylä, & Elliott, Citation2014).

The current state of the art

It is characteristic for psychotherapy as interaction that it aims toward change in the feelings, thoughts, and behaviors in the client. Conversation analysis offers unique methods for investigating such change in situ because it is geared to describe moment-by-moment evolution of talk that is organized as sequences of actions. The existing CA research on psychotherapy has thus a double foci: One is on the organization of sequences of action, and the other is in the process of therapeutically relevant change that takes place in and through these action sequences. In what follows, I will present the existing CA research on psychotherapy, first considering therapy as action sequences and then considering the therapeutic change that takes place through such sequences.

Sequence organization and psychotherapy

Among the generic structures of conversational interaction (Schegloff, Citation2007), it is sequence organization that has most explicitly been attended to in CA research on psychotherapy. There are also other generic structures—interactional organizations that need to be worked with in any social encounter, such as repair, turn taking, and participation. They, however, have thus far been more in the background in CA studies on psychotherapy (see, however, Madill, Citation2015).

On the most primordial level, sequential structure involves the inherent connectedness of adjacent utterances. A prior utterance constrains the next one, and the next one reflectively shows what the prior one was understood to be (Heritage & Atkison, Citation1984). As Schegloff (Citation2007, p. 15) put it, “Next turns are understood by co-participants to display their speaker’s understanding of the just prior turn and to embody an action responsive to the just-prior turn so understood.”

Utterances connected in this way are further organized into first- and second-position actions, as well as pre-, insert, and postexpansions (Schegloff, Citation2007). This sequential machinery provides for many possibilities in the assembling trajectories of conversational interaction. One of the most basic ones involves three steps:

Initiation (e.g., Question)

Response (e.g., Answer)

Third-position action (e.g., “Thank you”)

Such three-turn (or three-action) structures have indeed been explicated in many CA studies on psychotherapy. The studies show in many ways that the participants orient themselves to such structure. In what follows, I will use it as a template, to orient myself and the reader, in discussing some key studies on psychotherapy interaction.

Let us start by considering an example from computer-mediated therapy. Ekberg et al. (Citation2013, Citation2016) investigated cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that was conducted online via chat between the therapist and the client. The online environment makes the record of the interaction—log of the chat—readily available for the analysis. Such a log also makes sequential structures particularly transparent. Ekberg et al. studied question-answer sequences, with a particular focus on the third-position action that comes after the client’s answer to the therapist’s information elicitation question. Regarding questions and answers that may have emotional relevance for the client, they differentiate between three types of third-position actions: thanking, commiseration, and emotional inference. I will show an example of each. Consider Extract 1 as an example of thanking.

Extract 1 (Ekberg et al., Citation2013)

1 T: That is a long relationship. Hope you don't2 mind, I am going to switch topics, but would3 like to talk more about your relationship4 another time. How would you describe your5 health and fitness?6 C: i describe it as bad i drink eat junk food and7 not a lot of excercise but this is only the last8 year9 T: How different was it before last year?10 C: i was interested in doing things and enjoyed 11 and tried different things12 T: Thanks. How much do you drink in a typical day13 or week now?14 C: used to drink daily now 2 or 3 nights average15 of 8 pints of lagerThe therapist (T) is involved in a question-answer series, inquiring about the client’s (C) health and fitness. The focal sequence is in lines 9–13. As follow-up to the client’s prior answer, the therapist in line 9 inquires about the client’s habits prior to the last year (that the client has described as bad). In her answer (lines 10–11), the client conveys that then her habits were good. In the third-position action (lines 12–13), the therapist acknowledges the prior answer with thanks, then moving on to another question that focuses on the client’s current habits. By thanking the client, the therapist treats the prior answer as not relevant for further attention or elaboration at this particular moment.

Another third-position practice in the question-answer sequences investigated by Ekberg et al. (Citation2013) involved what they called commiseration. Consider Extract 2.

Extract 2 (Ekberg et al., Citation2013)

1 T: yes, poor memory can be a real2 inconvenience when your mood is3 low, tell me a little bit about your4 situation?5 T: when did you go see the doctor?6 how long have you been feeling this7 way? is this the first time you've felt8 low?9 C: i went to see the doctor after bad10 work situation she suggested this11 treatment she is very good, suggest i12 try this to see if it helps. have been13 suffering from depression for 7 years,14 took a course of anti depression for 515 months back in 2000, this helped but16 came off because i did not want to tbe17 dependent.18 T: has there been a time in the 7 years19 when you have felt well? is the work20 situation ongoing?21 C: always well enough to work, always22 function well at work, but tend to stay 23 indoors and not socialise, cut myself off24 for 7 years now,25 T: i'm sorry to hear that jennifer.26 what about the bad work situation, can27 you tell me a bti more about it?28 C: i am a careers advisor, worked in wales,29 finished 2 weeks ago, after being on sick30 leave for a month ((Jennifer's telling continues))The therapist and the client are engaged in exploration of the history of the client’s problems through a series of questions and answers. In lines 18–20, the therapists asks a question to follow up the client’s account of her seven-year-long depression (line 13). In her answer in lines 21–24, the client depicts her situation during those years, first reporting the positive aspects and then giving a three-part list (Jefferson, Citation1990) of the negative ones (staying indoors, not socializing, cutting herself off). The temporal reference at the end of the turn (“for 7 years now”; circulating temporal references from lines 9 to 20) emphasizes the seriousness of the problems. It is these emphasized negative aspects of the client’s situation that the therapist attends to in her next turn that begins with I’m sorry to hear that jennifer. Like thanking in Extract 1, the therapist’s third-turn response acknowledges the prior response and works as a “sequence closing third” (Schegloff, Citation2007) to end up the prior question-answer sequence. However, unlike in Extract 1, here the third-turn response “displays an explicit personal stance towards the information contained in [the client’s] response” (Ekberg et al., Citation2013). After the third-turn response, the therapist here, as in Extract 1, proceeds to another question exploring the client’s situation (lines 26–27).

In Ekberg et al.’s (Citation2013, Citation2016) data, commiserations were not the only third-turn response that acknowledged the emotional valence of the client’s response. In emotional inference, the therapist formulates a mental state “that is marked as an inference through the inclusion of an evidential verb” (Ekberg et al., Citation2016, p. 316). Emotional inferences are used when the client’s answer is affective but does not involve an explicit first person emotion description. Consider Extract 3. In his past, the client has been involved in illegal drugs, and it is that past that the therapist is asking him questions about.

Extract 3 (Ekberg et al., Citation2016)

1 T: perhaps we should turn to looking2 at how you feel about yourself? Do3 you think you have forgiven yourself4 yet?5 C: yes i have forgiven myself, put it6 down to experience,but i still have7 nightmares about police busting into8 our houseturning thee place upside9 down and being chucked in a cell10 T: sounds terrifying. When you say11 nightmares, you mean dreams that12 happen when you are asleep?13 C: yes14 T: And do you get flashbacks at all-15 waking experiences where you relive16 the awful things as if they were17 real again?In lines 5–9, the client volunteers an account about his nightmares, which apparently reinvoke his past experiences with illegal drugs. The scenario that he depicts is highly emotional, yet he does not explicate his own feelings associated to that. In response to the client’s answer, the therapist in line 10 asserts sounds terrifying. Thereby, she shows on one hand his/her own emotional reaction and, on the other, the emotion that s/he thinks that the client has experienced.

To summarize, Ekberg et al. showed three variants of a sequence consisting of a question, an answer, and an utterance doing the work of a “sequence closing third” (Schegloff, Citation2007). The therapist’s third-turn action embodied the difference between the three variants. This choice was informed by the client’s answer—whether or not it was foregrounding negative emotionally relevant material (which was the case in Extracts 2 and 3, but not so much in 1): The less emotional answers could be responded to with a nonemotional thank you, whereas the more emotional answers made relevant the other types of responses. Furthermore, it was relevant whether the client’s answer included a lexical first person emotion description (as in 2) or conveyed the emotion indirectly (as in 3)—in the former case, commiseration was relevant, whereas in the latter case, emotional inference.

The work of Ekberg et al. (Citation2013, Citation2016) is exemplary as it so clearly shows the sequential focus of CA approach to psychotherapy. This clarity is also made possible by the lack of the expressive complexity characterstic for the co-present interactions; yet as I will show, similar structures have been found also from the co-present therapeutic sessions.

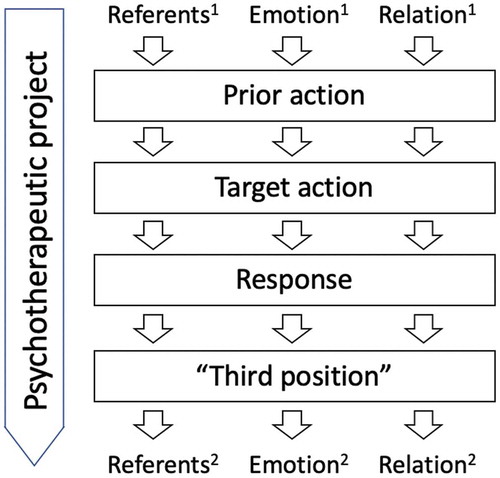

On the basis of the existing research and conversation analytical theory, a general model of sequential organization of psychotherapy interaction can be outlined. Such a model can help us to depict the existing research on psychotherapy interaction, and it can also serve as a heuristic aid, helping researchers to identify sequential relations in their psychotherapeutic data. The model is very simple, and it is presented in .

Figure 1. A simple model of the sequential organization of psychotherapy interaction. (The text in the right-hand column is from Extract 2.)

“Target action” can refer to any distinguishable action that the conversation analyst focuses on. Most of the CA research on psychotherapy has focused on a therapist’s actions, such as formulations (e.g., Antaki, Citation2008), interpretations (e.g., Bercelli, Rossano, & Viaro, Citation2008; Peräkylä, Citation2004), or questions (e.g., MacMartin, Citation2008). Yet clients’ actions—for example, narration or complaining—could quite as well be taken as the target. While actions can be predominantly initiatory (such as questions, or more generally, first pair-parts; Schegloff, Citation2007) or responsive (such as answers, or more generally, second pair-parts; Schegloff, Citation2007), there is a responsive and initiatory dimension in virtually all actions: They deal with something that was just before, and they have consequences to what can happen next (Heritage & Atkison, Citation1984). This is how we can understand our target actions. “Prior action” involves what comes before the target action. The prior action creates affordances and/or relevancies for the target action: For example, the client’s narration can make possible or invite evaluations, formulations, interpretations, or questions. “Response,” naturally, is what the target action makes relevant, while the “third position action” involves what the producer of the target action (usually the therapist) does in “response to the response,” i.e., what he or she makes out of the response.

In , segments from Extract 2 are placed in the sequential template. While the papers of Ekberg et al. (2013, 2016) were primarily concerned about the third-position actions, I have here shifted the focus, taking the question that initiates the sequence as the target action.

CA studies have indeed shown numerous sequential patterns through which psychotherapy gets done. CA research has shown how these sequences of action emerge, how the therapist’s actions create different constraints for client response, and also avenues for resistance. Among the most powerful examples are formulations.

Formulations

Formulations are perhaps the most researched action in conversation analysis of psychotherapy (Antaki, Citation2008; see also Antaki, Barnes, & Leudar, Citation2005; Bercelli et al., Citation2008; Hutchby, Citation2005; Madill, Widdicombe, & Barkham, Citation2001; Vehviläinen, Citation2003). The concept of formulation comes from Garfinkel and Sacks (Citation1970) and Heritage and Watson (Citation1980). In a formulation, as it usually emerges in psychotherapy, a speaker suggests the meaning—a candidate understanding—of the other speaker’s prior talk. In doing that, formulations are selective (focusing on something, and focusing away from something else, that the interlocutor just said). They make relevant confirmation or disconfirmation, often also elaboration, by the next speaker.

A speaker can formulate many kinds of interlocutor talk. In psychotherapy, formulation of the other’s subjective experience is particularly salient. In a study comparing psychoanalytic and cognitive therapies, Weiste and Peräkylä (Citation2013) showed four types of formulations of the client’s descriptions of their problematic experiences: highlighting, rephrasing, relocating, and exaggerating formulations. They differ from each other in terms of the lexical and sequential features, as well as the therapeutic task. encapsulates the differences.

Table 1. Four types of formulations (Weiste & Peräkylä, Citation2013).

Let us consider two different types of formulation of the client’s subjective experience description. Extract 4 involves a rephrasing formulation. In a rephrasing formulation, the therapist renames the client’s subjective experience and thereby invites self-reflection. The client in Extract 4 has been telling about a work-related conflict between himself (a manager in a social service institution) and his staff.

Extract 4 (Weiste & Peräkylä, Citation2013)

In lines 1–8, the client describes his problematic experience. In his formulation in line 10, the therapist focuses on the client’s emotion in his narrative, rephrasing the client’s prior description using a common psychological category “anxious.” The client confirms and upgrades the formulation in line 11, whereafter he elaborates his viewpoint and experience (lines 13–53). Here, the task (and effect) of the formulation seems to be to enhance the client’s self reflection: focusing on the personal emotional meaning of the events that he was telling about.The formulation in Extract 5 has a rather different therapeutic task. We call this an exaggerating formulation. As in Extract 4, the sequence begins with the client’s description of a problematic experience, which in this case has to do with the attitude of the client’s mother: She wants her children to be humble and rejects all criticism (lines 1–8).

Extract 5 (Weiste & Peräkylä, Citation2013)

In her formulation (lines 12–14) the therapist exaggerates the point of the client’s prior description, thereby showing that the mother’s attitude is unreasonable and even ridiculous. Rather than agreeing, the client disagrees in line 15—and this indeed seems to be the response that the exaggerating formulation elicited. The therapeutic task of the formulation was to challenge the client’s way of relating to her mother’s views, to encourage her to question them.Extracts 4 and 5 exhibited similar sequential structure: Client talk about problematic experience was formulated by the therapist, and the client responded to the formulation. The target action, formulation, was in a broad and structural sense similar: The therapist suggested a meaning of the client’s prior talk. However, the therapeutic tasks of the formulations were different. This difference was achieved by means of lexical choices (how the formulation was related to the client’s prior talk) and response relevancies (what kind of response the formulation elicited), as shown in more detail in .

How to understand the psychotherapeutic process

Showing sequential patterns (in questions, formulations, interpretations, etc.) is not the only thing that CA on psychotherapy does—and perhaps not even the most important thing. CA also seeks to show how psychotherapeutic process takes place through these sequences. Here, the concerns of CA and the concerns of clinical practice meet, as we try to understand how the sequential structures (concern of CA) facilitate the sociopsychological “substance” of psychotherapy (concern of clinical practice). Psychotherapy process, in any psychotherapeutic approach, is about transformation of experience. This transformation has been elucidated through conversation analytical studies.

A key to a CA view about transformation comes from the understanding that adjacent turns are tightly linked and that this linkage involves a constantly updating display of the interactants’ understandings of each others’ actions. This is how Schegloff formulates it: “Next turns are understood by co-participants to display their speaker’s understanding of the just prior turn and to embody an action responsive to the just-prior turn so understood” (Schegloff, Citation2007, p. 15).

Based on this very basic CA view, we can consider the sequence of adjacent turns as a vehicle of a transformation of experience. Understanding what actions and turns are doing involves understanding experience: the intention, cognitive state, and emotional stance that are part of the action and in many ways constitute it (see Enfield & Levinson, Citation2006; Levinson, Citation2006). Each turn in sequence embodies a description of the participants’ experience—in psychotherapy, usually foregrounding the client’s experience. “Nextness” of any turn at talk makes it inevitable that the current speaker will orient him/herself to the experience embodied in the prior turn.

he experience-under-transformation that is incorporated in action sequences is a target—perhaps the primary target—of CA studies on psychotherapy. But what does this interactionally enacted experience involve? To clarify this, let us return to Ekberg et al.’s (Citation2013, Citation2016) studies on online cognitive-behavioral therapy. Extract 6 is a fragment from Extract 3 shown earlier.

Extract 6 (fragment of Extract 3)

As Ekberg et al. (Citation2016) point out, through Extract 6, the client and the therapist orient themselves to the client’s emotion. The client first talks about forgiving himself and then describes his scary dreams; in response, the therapist in line 6 puts into words feeling that the description of the dreams evokes in her.Alongside emotion, relation is part of the interactionally enacted experience. In and through her emotional inference (Ekberg et al., Citation2016), the therapist empathizes with the client. By designing her third-position turn as an inference—or what Heritage (Citation2011) calls a subjunctive assessment—he empathizes in a particular way: respecting the boundaries of the client’s subjective experience, showing that she cannot experience what the client has experienced, but still recognizing the client’s feelings associated with his experiences.

The participants’ orientation to emotions and their management of their relation takes place through talking about real and fantasied objects in the world. Perhaps more than in some other contexts, the referential meaning of utterances is crucial in psychotherapy. It is the client’s and the therapist’s task to invoke memories, fantasies and dreams, real and fantasied worlds, through their talk. So, in Extract 6, the client invokes “nightmares” as a referent to attend to and describes the scenes in them. In her question after the emotional inference, the therapist seeks clarification to the referent: Are they in the nightly dreams (or in awake fantasies).

One way to conceptualize the experience-under-transformation in psychotherapy interaction arises from this. Referents, emotion, and relation are three overlapping realms of experience, the transformation of which takes place through the sequentially organized talk in psychotherapy. We can now complement our template for analyzing the psychotherapy interaction.

below depicts three psychosocial processes that take place through the sequentially organized talk and action: transformation of referents, transformation of emotion, and transformation of relation. Each utterance in the continuum of actions involves a momentary documentation of referents, emotion, and relation. Each next utterance involves such documentation as well, but necessarily something has changed: The next speaker attends to the referents, emotion, and relation as they were in the prior turn, but in his or her turn, they also become different. This is where the psychotherapeutic process takes place.

When things go well, the change in referents, emotion, and relation is not arbitrary or completely unexpected. The goal of psychotherapy interaction is to facilitate such transformation in the referents, emotion, and relation that helps the client to overcome the difficulties that brough him/her to therapy. This can be called the psychotherapeutic project: the overall goal setting and structuring of the interaction that is meant to help this particular client to overcome his/her particular obstacles in his/her behavior, social relations, or internal life. Which one of these is emphasized depends on the psychotherapeutic approach. Regardless of the approach, however, the psychotherapeutic project involves a professional understanding of the client’s problem and its possible remedies. In , such goal setting is depicted by the big downward arrow in the left-hand side.

Transformation of referents

Most, if not all, utterances in conversation invoke and maintain the interactant’s attention to some referents. The referents may be in the shared perpectual world, but they can also be outside the interactional situation, invoked by narratives, assertions, and the like. Referentiality of talk is particularly salient in psychotherapy. The clients and the therapists discuss various aspects of the client’s experience in the world—be it real, imagined, or dreamed about. Questions, narratives, formulations, and interpretations deal with shared referential worlds. The referents get transformed in and through sequentially organized actions.

Consider Extract 7. It is taken from a sequence of interpretation. In an interpretation, unlike in formulation, the therapist presents his own view about something that the client has spoken about (Bercelli et al., Citation2008; in formulation the therapist suggests a meaning of the client’s talk). The client is a man in his forties. Before the extract, he was talking about his youth hobby, athletics, in a narrative that involved a complaint about his mother, who did not encourage him in his hobby but was rather critical about it. The therapist’s interpretation (the end part of which is shown in the following extract) suggests that actually the client is dissatisfied for the mother not having been the father and that it is difficult for the client to admit that the father wasn’t there. (The father left the family and became an alcoholic. Various aspects of this interpretation have been investigated in Peräkylä (Citation2005, Citation2011).

Extract 7 (Peräkylä, Citation2011)

In Extract 7, what we could call a referential chain emerges: an utterance-by-utterance (even moment-by-moment) shifting focus of attention to objects that are being talked about. In the beginning part of the extract, in his interpretation, the therapist is referring to the client’s feelings, expectations, and disappointments regarding his father and mother. The client does not respond to the interpretation (see silences in lines 4, 8, 12). Seemingly alive to the client’s nonengagement and to pursue response, the therapist adds a new element to the interpretation in lines 19–25. In line 19, a referential shift occurs, from the client’s inner world to outer realities. The therapist now characterizes the father’s conventional duties; the description of these duties is offered as evidence for the therapist’s interpretative claim that the client’s disappointment actually concerns his father and not the mother.As the client eventually takes up the interpretation, the referential focus shifts once more: He comes back to the world of his narrative (delivered before the interpretation, data not shown) and depicts a retrospective hypothetical scene where his father is whooping in support of him, thereby acknowledging where the real father was absent from. In the third position, yet another referential shift takes place: The therapist remains in the imagined world that shows where the real father was not, but now the father is depicted in another context, as a key figure in the athletics club.

The evolvement of the referential chain is meaningful regarding the aims of the therapy. In his response to interpretation (lines 29–32), the client acknowledges what the therapist is suggesting to him: The father was absent, and it was a loss to him. In the third position, by yet another transformation of the referential world, the therapist foregrounds a particular aspect of this loss: It was not only the “whooping father”—one fascinated by his son’s success—but also a powerful and protective father—one in the steering committee of the athletics club—that the client was missing. The loss was even bigger than what the client first acknowledged (see Peräkylä, Citation2011).

Transformation of emotion

In the past decade or so, conversation analytical studies on emotion have proliferated, documenting the verbal and nonverbal means of interactional regulation of emotion that may indeed be an aspect of all encounters (Peräkylä & Sorjonen, Citation2012; Stevanovic & Peräkylä, Citation2014). In psychotherapeutic interaction, such regulation of emotion is among the participants’ core institutional tasks. Like transformation of referents, also the transformation of emotion takes place in and through adjacent utterances. Many CA studies show how the therapists’ actions are geared to work with the clients’ emotions (Ekberg et al., Citation2016; Peräkylä, Citation2008a; Rae, Citation2008; Voutilainen, Peräkylä, & Ruusuvuori, Citation2010a, Citation2010b). Resources for the work with emotions involve lexical choice and grammatical structures, prosodic features of talk (for studies on prosody, see Fitzgerald, Citation2013; Weiste & Peräkylä, Citation2013) as well as crying (Muntigl & Horvath, Citation2014a) and laughing. Facial expressions are surely also involved, but facial expression in psychotherapy still waits for its conversation analytical appropriation (see, however, Bänninger-Huber & Widmer, Citation1999).

A beautiful example of the therapist’s work with emotions is in Rae’s (Citation2008) paper on lexical substitutions. It involves a case study of one therapy session. The focus is on a particular variation of a practice well known in conversation analysis: other-initiated repair (Schegloff et al Citation1977). With this variant, called lexical substitution, the therapist can intensify the emotional content of the client’s talk. The prior action can involve a client’s problem indicative talk, as in Extracts 8 and 9.

Extract 8 (Rae, Citation2008)

Extract 9 (Rae, Citation2008)

In both cases, the client is telling about her recent difficult experiences. The therapist makes “corrections” to the client’s talk: in Extract 8, he substitutes “a lot” to client’s “a little” and in Extract 9, “pretend” to client’s “do.” In both instances, the emotional import of the description gets intensified. Thereby, the therapist shows that he recognizes the client’s painful experiences and indeed suggests that the experiences are more painful than what the client initially indicated. This transformation of emotion can be therapeutically meaningful, as a means of showing empathy and/or as a means of helping the client to face difficulties in her situation. In both cases, the client recycles the substituted words and shows her agreement with the “upgraded” depiction of emotion.For another example of transformation of emotions, consider again Extract 5. In lines 1–9, the client is telling about her relation to her mother. She talks in a complaining stance that is conveyed by her lexical choices (e.g., “feels like being in debt” in 1) and discourse strategies such as citing the mother (in lines 7–9). The therapist’s exaggerating formulation in lines 12–14 conveys another kind of stance: defiance toward the mother and toward the client’s feeling of being in debt. This shift in the emotional stance is therapeutically important as a means of enhancing the clients independency and agency vis-à-vis the mother.

Transformation of relation

Any social encounter documents, reproduces, and renews the social relation between the participants (Goffman, Citation1971, Citation1983). Psychotherapeutic encounters not only involve the general institutional identities of the client and the therapists but perhaps more importantly, they document, reproduce, and renew the particular socioemotional relation between this particular therapist and this particular client moment by moment. The key relational phenomena here include agreement and disagreement or resistance (Ekberg & LeCouteur, Citation2015; MacMartin, Citation2008), affiliation or disaffiliation (Ekberg et al., Citation2016; Muntigl & Horvath, Citation2014b; Muntigl et al., Citation2013; Voutilainen, Peräkylä, & Ruusuvuori, Citation2010c), and the epistemic relation between the participants (Ekberg & LeCouteur, Citation2015; Muntigl et al., Citation2013; Weiste, Voutilainen, & Peräkylä, Citation2016). These and other aspects of the momentary relation get transformed through sequentially organized actions.

The work of Muntigl and collaborators (Muntigl & Horvath, Citation2014b; Muntigl et al., Citation2013) is exemplary for the analysis of momentary transformations of relation. Their focus is on affiliation and disaffiliation, understood as a speaker’s endorsement, of lack of it, of the preferences realized in a prior speaker’s utterance (Muntigl et al., Citation2013). Studying emotion-focused therapy with depression, they examine the therapists’ formulations and the clients’ responses to them. Disaffiliative responses to formulations may be such that they do not endorse the therapist’s version of client’s situation, or they may embody client resistance to the therapist’s agenda. A central question for Muntigl and colleagues is: What happens after the client’s dissaffiliative response? How is affiliation achieved again? The focus of Muntigl and colleagues’ studies is thus in third position, in the therapist’s actions after the client’s response to a formulation.

Muntigl and Horvath (Muntigl & Horvath, Citation2014b; see also Muntigl et al., Citation2013) focus mostly on third-position actions that secure reaffiliation. In typical moves, the therapist retreats from the position s/he expressed in the formulation and joins with the client’s position brought up in his/her disaffiliative response to the formulation. Such joining of the client’s position can be done both nonverbally by nodding and verbally. The other avenue for third-position action is more confrontational: The therapist confronts the client’s disagreement, usually treating it as a problem of understanding that requires repair. The confrontational third-position action does not necessarily lead to reaffiliation.

Consider Extract 10 as an example of reaffiliation in the third position.

Extract 10 (Muntigl & Horvath, Citation2014b)

In Weiste and Peräkylä’s (Citation2013) terms, the target action in lines 13–16 seems to have some characteristics of an exaggerating formulation: It challenges the client’s prior reasoning by depicting it in such a way that is difficult to agree with. However, unlike Weiste and Peräkylä’s exaggerating formulations, this one does not invite clear disagreement either; its import seems to be to invite the client into more exploration of her feelings and preferences. The client’s response in lines 17–21 is disaffiliative: By appealing to lack of knowledge, she avoids engaging herself in further exploration that the therapist invited her to. In her third-position action (lines 23 and 25), the therapist first, with prosodically marked tokens, agrees with what the client said and then produces a “second formulation” (Muntigl et al., Citation2013, p. 12) of the client’s response (so that’s a big unknown (…) maybe ye (…) would just be the same). Furthermore, in lines 27–33, the therapist and the client collaborative elaborate each other’s descriptions. Through these actions, the therapist and client reaffiliate after the moment of disaffiliation.The moment-by-moment work with affiliation may be therapeutically significant in two ways. On one hand, affiliation can be like an infrastructure of therapy: To maintain the cleint’s commitment to therapy, a basic level of affiliation between the participants needs to be maintained. The other therapeutic task for the work with affiliation is more complex. It can be important for some clients to learn to move safely and freely between moments of affiliation and disaffiliation rather than being persistently “stuck” in a position of affiliation or disaffiliation. The variation between disaffiliation and reaffiliation described by Muntigl and colleagues may also enhance such movement.

Therapeutic projects across sequences and sessions

While conversation analysis predominantly focuses on the organization of adjacent utterances or actions that form sequences, it also acknowledges organizations that go beyond single sequences. One such is “interactional project,” which involves a “course of conduct being developed over a span of time (not necessarily in consecutive sequences) to which co-participants may become sensitive” (Schegloff, Citation2007, p. 244). So, interactional projects involve longer-term intentionality in the part of one or more interactants: aims or purposes that give meaning to actions and sequences of action (see also Levinson, Citation2012).

Psychotherapy is characterized by interactional projects with accompanying therapeutic aims. They can be called therapeutic projects (Peräkylä, Citation2011). The therapist has an understanding of the client’s problems and possible avenues of improvement; such understanding may, to a larger of smaller degree, be shared between the client and the therapist. The transformations of experience through sequences of action occur in the context of such projects, incorporating the therapist’s efforts to nurture particular kinds of experiences and understandings in the client. Arguably, these projects persist over sequences and over sessions, as the therapist’s understanding of his/her client’s core problems evolve.

Studies by Voutilainen, Peräkylä, and Ruusuvuori (Citation2011), Peräkylä (Citation2012), and Bercelli, Rossano, and Viaro (Citation2013) have documented both continuities and evolvement over time in psychotherapeutic interaction. Their studies show how a particular theme, addressed in a specific sequential context (e.g., in an interpretation or a formulation) evolves over time across therapy sessions. This evolvement incorporates what in clinical language is called “psychotherapeutic process” (see also Voutilainen, Rossano, & Peräkylä, Citation2018). In the context of couples therapy, Muntigl (Citation2013) showed comparable evolvement over sessions: in this case, an increase of the counselors’ third-position disaffiliation to clients resisting answers.

For an example of a therapeutic project over sessions, let us return to the example of interpretation that was shown earlier (see Extract 7; Peräkylä, Citation2011, Citation2013). During sessions subsequent to the one from which Extract 7 was taken, the participants returned to themes that emerged in the therapist’s interpretation and his third-position comments. We will now consider two extracts, taken from different sessions, that demonstrate the progression of the therapeutic project. Consider first Extract 11, which shows that in the initial interpretative sequence (see Extract 7), the client did not so much attend to the way in which the therapist depicted his missing father differently from his own depiction of the father.

Extract 11 (Extension of extract 7; Peräkylä, Citation2011)

As we pointed out, the analyst’s third-position action (lines 7–8) arguably does significant psychotherapeutic work: By invoking the figure of the powerful father, he demonstrates the magnitude of the client’s loss. He did not only miss the father who would be fascinated by his success in sports (the whooping father) but also a father who would support him and the local community, a powerful father, one for the son to be proud of. The transformation of referents here is interwoven with transformation of emotion (intensification of the loss).The client receives the therapist’s third-position action first by minimal but emphasized agreement (line 10). This is followed by a silence of 35 seconds, whereafter the client continues on topic. His utterance in line 14–16 conveys that what the analyst has said gave him a new perspective to his relation to his father. However, the client does not display any orientation to the transformation of emotion and referents in the therapist’s third-position utterance: In saying that I didn’t assume that (…) father would do something like that (lines 15–16), he does not make a differentiation between the “whooping” father (lines 2, 4) and the representation of the powerful father in the steering committee (lines 7–8). So, by now, the transformation of referents and emotion in the third position remains implicit.

However, examination of the subsequent sessions suggests that the transformation of referents and emotion in the third position still was meaningful in the context of a therapeutic project. The loss of a father was a thematic thread across the sessions. Two sessions after the one from which Extracts 7 and 11 were taken, the client described his loss once more—and now, the questions of the father’s weakness and his place in the local community were prominent. Consider Extract 12, where the client, on his own initiative, talks about the shame for the father in the local community.

Extract 12 (two sessions after extract 11; Peräkylä, Citation2012)

The client’s memories about his father in the context of the local community, discussed two sessions after Extract 11, are diametrically opposite to the depiction of the missing father in the therapist’s third-position utterance in Extract 11. Against the backdrop of the client’s shameful memories of his real father, the loss of the father as a benefactor in the local community—foregrounded by the analyst’s transformation of referents in third position—seems to be all the more painful.As seen in the light of the subsequent sessions (a glimpse of which is shown in Extract 12), the third-position transformation of referents in Extract 11 shown earlier seems to be a part of a progressive psychotherapeutic project. In this project, the therapist is—quite successfully—helping the client to face and “own” the pain caused by the loss of the father. Processes like this can be called “assimilation of problematic expriences” (Stiles et al., Citation1990), and they are at the core of clinical understandings of psychotherapy. Segments of talk in different sessions (such as Extracts 11 and 12) are part of the psychotherapeutic project, and the progression of the project can be investigated by examining how the talk changes—in particular, in terms of referents, emotion, and relation—in and between such segments (Voutilainen et al., Citation2018).

The future of CA and psychotherapy research

In the coming years, the conversation analytical understanding of psychotherapeutic interaction will probably be deepened in three directions:

We will probably be exploring aspects of interaction that are tied to particular disorders (such as depression or personality disorders) and their therapeutic management. Up until now, most CA research on psychotherapy has been indifferent regarding the actual psychiatric problems that the clients have: The focus has been on more generic therapeutic techniques or client practices, without making differentiation between different disorders. In recent work by Muntigl (Citation2016), the specifics of therapeutic interaction with depressed clients have been taken up. In a nontherapeutic context, Mikesell and Bromley (Citation2016) have used conversation analysis to explore the variety of talk in schizophrenia. There is still much to do: We could explore what are the interactional manifestations of, say, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorders, or personality disorders, and how different therapeutic approaches deal with them.

The uses of body in psychotherapy interaction also call for further research. The work thus far has been perhaps more “logocentric” than most other subfields of CA, partially because the data used in studies in this field are still quite often audio rather than video. Video is, however, the gold standard for interaction studies, and it is important that the future studies use video whenever possible. Muntigl et al.’s (Citation2013) work on nodding as a means to regain affiliation after disagreement is exemplary. In another vein, Voutilainen et al. (Citation2018) have combined conversation analysis with the measurement of autonomic nervous system responses, to track the linkages between interactional practices and bodily responses during psychotherapy sessions. In spite of these developments, it needs to be acknowledged that in “non-CA” interaction research, the exploration of the uses of the body in therapeutic settings has been more intensive and detailed than in CA thus far (see, e.g., Lavelle, Healey, & McCabe, Citation2014; Ramseyer & Tschacher, Citation2011; Scheflen, Citation1973). The combination of up-to-date motion-capturing techniques and conversation analytic insights is possible (see Stevanovic et al., Citation2017)—applications in therapeutic interaction await future study.

The incipient research on processes of change taking place over several sessions is also a field that awaits further elaboration. The recent collection on longitudinal CA studies (Pekarek Doehler, Wagner, & Gonzáles-Martínez, Citation2018) shows various possible avenues for longitudinal investigation of change in interaction. The perspectives that have emerged from the study of various institutional and noninstitutional settings can be adopted in the study of psychotherapy. Examining change is important because psychotherapy aims at change: Here research meets the clinical priorities.

Alongside the deepening of study of psychotherapeutic interaction, conversation analysis is becoming engaged in a closely related clinical practice: psychiatric encounters. It is important to remember the difference between these two: While psychotherapy involves frequent encounters between client and clinician with the aim of exploring and transforming the client’s mind, psychiatric encounters are more infrequent; their aim is to diagnose or monitor the client’s mental disorders and to decide about the treatment. The conversation analytical studies of psychiatric encounters have proliferated in recent years. Two distinct foci emerge from the studies.

Studies on the interactional organization of treatment decisions have mostly dealt with adjustment of medication in long-term patients. They have showed patterns of patient engagement in decision making (Bolden & Angell, Citation2017; Quirk, Chaplin, Lelliott, & Seale, Citation2012) as well as variation in the clinicians’ claims, and patients’ submission, to deontic authority (Thompson & McCabe, Citation2018). Another set of studies deals with the place of patients’ subjective experience in psychiatric consultations. McCabe, Skelton, Heath, Burns, and Priebe (Citation2002) explicated the ways in which psychiatrists use counter-questions, smile, and laughter to resist the patients’ efforts to talk about their psychotic symptoms such as delusions. Another study (McCabe, Sterno, Priebe, Barnes, & Byng, Citation2017) documented the ways in which the grammatical form of clinicians’ questions regarding the patients’ suicidal thoughts predicted the answers: Patients were much more likely to claim that they have no such ideas after negatively polarized questions (such as You don’t have thoughts about harming yourself?), as compared to positively polarized questions. Recently, Savander et al. (Citation2019) compared two approaches of assessment interview, showing that in the standard medical interview format, the patients’ accounts or their subjective experiences often run against the agenda set by the clinicians’ questions, whereas in an alternative practice influenced by psychotherapeutic ideas, the questioning facilitates such accounts. Future studies on psychiatric encounters will probably continue exploring history taking, treatment decisions, and delivery and reception of diagnosis. In doing that, a perspective originally formulated by Bergmann (Citation1992, Citation2016) will probably require further work. According to Bergmann, the medical and the moral orientations are intrinsically interwoven in psychiatry. It will be the task of conversation analysis to show how this dual orientation emerges and is managed in moment-by-moment interaction.

Conclusion

Combining CA insights on the sequential organization of interaction, with sensitivity to the psychological processes that take place in and through interaction, is a key challenge of conversation analytical research on psychotherapy. This review has sought to show that such a combination has been achieved in recent studies on psychotherapeutic interaction. The studies thus far have been successful in demonstrating the ways in which sequential organizations promote moment-by-moment transformation of experience. Recent studies are also beginning to show the psychotherapeutic processes in a more extended temporal frame. These studies can address conversation analysts more broadly as they explore the intersection of the organization of sequences and the organization of experience. They can also address clinicians and psychotherapy reserachers as they show how psychotherapeutic processess are embedded in the concrete details of social interaction.

References

- Antaki, C. (2008). Formulations in psychotherapy. In A. Peräkylä, C. Antaki, S. Vehviläinen, & I. Leudar (Eds.), Conversation analysis and psychotherapy (pp. 26–42). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Antaki, C., Barnes, R., & Leudar, I. (2005). Diagnostic formulations in psychotherapy. Discourse Studies, 7(6), 627–647.

- Bänninger-Huber, E., & Widmer, C. (1999). Affective relationship patterns and psychotherapeutic change. Psychotherapy Research, 9(1), 74–87.

- Bercelli, F., Rossano, F., & Viaro, M. (2008). Clients’ responses to therapists’ reinterpretations. In A. Peräkylä, C. Antaki, S. Vehviläinen, & I. Leudar (Eds.), Conversation analysis and psychotherapy (pp. 43–61). Cambridge University Press.

- Bercelli, F., Rossano, F., & Viaro, M. (2013). Supra-session courses of action in psychotherapy. Journal of Pragmatics, 57, 118–137.

- Bergmann, J. (1992). Veiled morality: Notes on discretion in psychiatry. In P. Drew & J. Heritage (Eds.), Talk at work: Interaction in institutional settings (pp. 137–162). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Bergmann, J. R. (2016). Making mental disorders visible: proto-morality as diagnostic resource in psychiatric exploration. In M. O’Reilly & J. N. Lester (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of adult mental health (pp. 247–268). London, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bolden & Angell. (2017). The organisation of the treatment recommendation phase in routine psyciatric visits. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 50(2), 151–170.

- Buchholtz, M. B., Spiekermann, J., & Kächele, H. (2015). Rhythm and blues–Amalie’s 152nd session: From psychoanalysis to conversation and metaphor analysis–And back again. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 96(3), 877–910.

- Buchholz, M. B., & Kächele, H. (2017). From turn-by-turn to larger chunks of talk: An exploratory study in psychotherapeutic micro-processes using conversation analysis. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, 20(3), 161–178.

- Davis, K. (1986). The process of problem (re)formulation in psychotherapy 1. Sociology of Health & Illness, 8(1), 44–74.

- Ekberg, K., & LeCouteur, A. (2015). Clients’ resistance to therapists’ proposals: Managing epistemic and deontic status. Journal of Pragmatics, 90, 12–25.

- Ekberg, S., Barnes, R., Kessler, D., Malpass, A., & Shaw, A. (2013). Managing the therapeutic relationship in online cognitive behavioural therapy for depression: Therapists’ treatment of clients’ contributions. Language@ Internet, 10.

- Ekberg, S., Shaw, A. R., Kessler, D. S., Malpass, A., & Barnes, R. K. (2016). Orienting to emotion in computer-mediated cognitive behavioral therapy. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 49(4), 310–324.

- Enfield, N. J., & Levinson, S. C. (2006). Introduction: Human sociality as a new interdisciplinary field. In S.C. Levinson & N.J. Enfield (Eds.), Roots of human sociality. Culture, cognition and interaction (pp. 1–38). Oxford, England: Berg.

- Fitzgerald, P. (2013). Therapy talk: Conversation analysis in practice. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Garfinkel, H., & Sacks, H. (1970). On formal structures of practical actions. Theoretical sociology: perspectives and developments (pp. 338–386). New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Goffman, E. (1971). Relations in public: Microstudies of the public order. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

- Goffman, E. (1983). The interaction order: American sociological association, 1982 presidential address. American Sociological Review, 48(1), 1–17.

- Heritage, J. (2011). Territories of knowledge, territories of experience: Empathic moments in interaction. The Morality of Knowledge in Conversation, 29, 159–183.

- Heritage, J., & Atkison, M. (1984). Introduction. In J. M. Atkinson, J. Heritage, & K. Oatley (Eds.), Structures of social action (pp. 1–15). Cambrdige, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Heritage, J. C., & Watson, D. R. (1980). Aspects of the properties of formulations in natural conversations: Some instances analysed. Semiotica, 30(3–4), 245–262.

- Hutchby, I. (2005). ‘Active listening’: Formulations and the elicitation of feelings- talk in child counselling. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 38(3), 303–329.

- Jefferson, G. (1990). List construction as a task and resource. In G. Psathas (Ed.), Interaction competence (pp. 63–92). Washington, DC: University Press of America.

- Labov, W., & Fanshel, D. (1977). Therapeutic discourse: Psychotherapy as conversation. New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Lavelle, M., Healey, P. G., & McCabe, R. (2014). Participation during first social encounters in schizophrenia. PloS One, 9(1), e77506.

- Lepper, G. (2009). The pragmatics of therapeutic interaction: An empirical study. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 90(5), 1075–1094.

- Levinson S. C. (2012). Action formation and ascription. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.), Handbook of conversation analysis. Boston, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Levinson, S. C. (2006). On the human “interaction engine”. In S. C. Levinson & N. J. Enfield (Eds.), Roots of human sociality. Culture, cognition and interaction (pp. 39–69). Oxford, England: Berg.

- MacMartin, C. (2008). Resisting optimistic questions in narrative and solution-focused therapies. In A. Peräkylä, C. Antaki, S. Vehviläinen & I. Leudar (Eds.), Conversation analysis and psychotherapy (pp. 80–99). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Madill, A. (2015). Conversation analysis and psychotherapy process research. In O. Gelo, A. Pritz, & B. Rieken (Eds.), Psychotherapy research (pp. 501–515). Vienna, Austria: Springer.

- Madill, A., Widdicombe, S., & Barkham, M. (2001). The potential of conversation analysis for psychotherapy research. Counseling Psychologist, 29(3), 413–443.

- McCabe, R., Skelton, J., Heath, C., Burns, T., & Priebe, S. (2002). Engagement of patients with psychosis in the consultation: Conversation analytic study. British Medical Journal, 325(7373), 1148–1151.

- McCabe, R., Sterno, I., Priebe, S., Barnes, R., & Byng, R. (2017). How do healthcare professionals interview patients to assess suicide risk? BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 122.

- Mikesell, L., & Bromley, E. (2016). Exploring the heterogeneity of ‘schizophrenic speech’. In M. O’Reilly & J. N. Lester (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of adult mental health (pp. 329–351). London, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Muntigl, P. (2013). Resistance in couples counselling: Sequences of talk that disrupt progressivity and promote disaffiliation. Journal of Pragmatics, 49(1), 18–37.

- Muntigl, P. (2016). Storytelling, depression, and psychotherapy. In M. O’Reilly & J. N. Lester (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of adult mental health (pp. 577–596). London, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Muntigl, P., & Horvath, A. O. (2014a). “I can see some sadness in your eyes”: When experiential therapists notice a client’s affectual display. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 47(2), 89–108. doi:10.1080/08351813.2014.900212

- Muntigl, P., & Horvath, A. O. (2014b). The therapeutic relationship in action: How therapists and clients co-manage relational disaffiliation. Psychotherapy Research, 24(3), 327–345.

- Muntigl, P., Knight, N., Watkins, A., Horvath, A. O., & Angus, L. (2013). Active retreating: Person-centered practices to repair disaffiliation in therapy. Journal of Pragmatics, 53, 1–20.

- Pekarek Doehler, S., Wagner, J., & Gonzáles-Martínez, E. (eds.). (2018). Longitudinal studies on the organization of social interaction. London, England: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Peräkylä, A. (2004). Making links in psychoanalytic interpretations: A conversation analytic view. Psychotherapy Research, 14(3), 289–307.

- Peräkylä, A. (2005). Patients’ responses to interpretations. A dialogue between conversation analysis and psychoanalytic theory. Communication & Medicine, 2 (2): 163–176.

- Peräkylä, A. (2011). After interpretation: Third-position utterances in psychoanalysis. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 44(3), 288–316.

- Peräkylä, A. (2012). Die Interaktionsgeschichte einer Deutung. In R. Ayass & C. Meyer (Eds.), Sozialität in slow motion Theoretische und empirische Perspektiven (pp. 375–405). Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer.

- Peräkylä, A. (2013). Conversation analysis in psychotherapy. In T. Stivers & J. Sidnell (Eds.), Handbook in conversation analysis (pp. 551–574). Oxford, England: Blackwell.

- Peräkylä, A., Antaki, C., Vehviläinen, S., & Leudar, I. (2008a). Analysing psychotherapy in practice. In A. Peräkylä, C. Antaki, S. Vehviläinen & I Leudar (Eds.), Conversation analysis and psychotherapy (pp. 5–25). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Peräkylä, A., Antaki, C., Vehviläinen, S. & Leudar, I. (Eds.). (2008b). Conversation analysis and psychotherapy. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Peräkylä, A., & Sorjonen, M. L. (Eds.). (2012). Emotion in interaction. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Pittenger, R. E., Hockett, C. F., & Danehy, J. J. (1960). The first five minutes: A sample of microscopic interview analysis. Ithaca, NY: Paul Martineau.

- Quirk, A., Chaplin, R., Lelliott, P., & Seale, C. (2012). How pressure is applied in shared decisions about antipsychotic medication: A conversation analytic study of psychiatric outpatient consultations. Sociology of Health & Illness, 34(1), 95–113.

- Rae, J. (2008). Lexical substitution as a therapeutic resource. In A. Peräkylä, C. Antaki, S. Vehviläinen, & I. Leudar (Eds.), Conversation analysis and psychotherapy (pp. 62–79). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Ramseyer, F., & Tschacher, W. (2011). Nonverbal synchrony in psychotherapy: Coordinated body movement reflects relationship quality and outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(3), 284.

- Savander, E. È., Weiste, E., Hintikka, J., Leiman, M., Valkeapää, T., Heinonen, E. O., & Peräkylä, A. (2019). Offering patients opportunities to reveal their subjective experiences in psychiatric assessment interviews. Patient Education and Counseling. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.02.021

- Scheflen, A. E. (1973). Communicational structure: Analysis of a psychotherapy transaction. Bloomington, ID: Indiana University Press.

- Schegloff, E. A. (2007). Sequence organization in interaction. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Schegloff, E. A., Jefferson, G., & Sacks, H. (1977). The preference for self-correction in the organization of repair in conversation. Language, 53(2), 361–382.

- Stevanovic, M., Himberg, T., Niinisalo, M., Kahri, M., Peräkylä, A., Sams, M., & Hari, R. (2017). Sequentiality, mutual visibility, and behavioral matching: Body sway and pitch register during joint decision making. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 50(1), 33–53.

- Stevanovic, M., & Peräkylä, A. (2014). Three orders in the organization of human action: On the interface between knowledge, power, and emotion in interaction and social relations. Language in Society, 43(2), 185–207.

- Stiles, W. B., Elliott, R., Llewelyn, S. P., Firth‑Cozens, J. A., Margison, F. R., Shapiro, D. A., & Hardy, G. (1990). Assimilation of problematic experiences by clients in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 27, 411–420.

- Sutherland, O., Peräkylä, A., & Elliott, R. (2014). Conversation analysis of the two-chair self-soothing task in emotion-focused therapy. Psychotherapy Research, 24(6), 738–751.

- Thompson, L., & McCabe, R. (2018). How psychiatrists recommend treatment and its relationship with patient uptake. Health Communication, 33(11), 1345–1354.

- Vehviläinen, S. (2003). Preparing and delivering interpretations in psychoanalytic interaction. Text, 23(4), 573–606.

- Voutilainen, L., Peräkylä, A., & Ruusuvuori, J. (2010a). Recognition and interpretation: Responding to emotional experience in psychotherapy. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 43(1), 85–107.

- Voutilainen, L., Peräkylä, A., & Ruusuvuori, J. (2010b). Professional non‐neutrality: Criticising the third party in psychotherapy. Sociology of Health & Illness, 32(5), 798–816.

- Voutilainen, L., Peräkylä, A., & Ruusuvuori, J. (2010c). Misalignment as a therapeutic resource. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 7(4), 299–315.

- Voutilainen, L., Peräkylä, A., & Ruusuvuori, J. (2011). Therapeutic change in interaction: Conversation analysis of a transforming sequence. Psychotherapy Research, 21(3), 348–365.

- Voutilainen, L., Rossano, F., & Peräkylä, A. (2018). Conversation analysis and psychotherapeutic change. In S. Pekarek-Doehler, J. Wagner & E. Gonzáles-Martínez (Eds.), Longitudinal studies on the organization of social interaction (pp. 225–254). London, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Weiste, E., & Peräkylä, A. (2013). A comparative conversation analytic study of formulations in psychoanalysis and cognitive psychotherapy. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 46(4), 299–321.

- Weiste, E., & Peräkylä, A. (2014). Prosody and empathic communication in psychotherapy interaction. Psychotherapy Research, 24(6), 687–701.

- Weiste, E., Voutilainen, L., & Peräkylä, A. (2016). Epistemic asymmetries in psychotherapy interaction: Therapists’ practices for displaying access to clients’ inner experiences. Sociology of Health and Illness, 38(4), 645–661.