?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Exploring the grammar–body interface, the present study examines employment of Hebrew causal clauses prefaced by the conjunction ki “because” in responsive disaffiliative moves. We show that in such environments, ki-clauses tend to convey information that appeals to the participants’ shared knowledge and to be accompanied by the Palm Up Open Hand gesture (PUOH). We argue that the PUOH in such contexts constitutes an embodied epistemic stance marker functioning to present the account prefaced by ki as based on shared knowledge, in pursuit of intersubjectivity and a shared perspective. The reference to shared epistemic access implies an interpretation of the disaffiliative move as reasonable under the circumstances provided by the account, inviting co-participants to display affiliation. The study thus validates that causality is a socially constructed, complex configuration that may include the speaker’s epistemic stance toward the actions accomplished in an interaction and suggests an interactional source for their interrelatedness. Data are in Hebrew

Adopting an embodied and situated view of talk (e.g., Goodwin, Citation1979, Citation1984, 2000, Citation2018; Hayashi, Citation2005; Iwasaki, Citation2009; Keevallik, Citation2018; Mondada, Citation2006, 2014; Pekarek Doehler et al., Citation2021; Streeck, Citation2009) and a conception of grammar as fundamentally temporal, emergent, dialogic, and interlaced with other semiotic resources (see Auer, Citation2009; Hopper, Citation1987; Keevallik, Citation2013; Linell, Citation2009; Maschler et al., Citation2020; Thompson et al., Citation2015), this study examines the emergence of an adverbial clause-combining pattern in Hebrew talk-in-interaction. We examine employment of Hebrew causal clauses prefaced by the most common causal conjunction (Maschler, Citation2018) found in our corpus (see below), ki (“because.”)Footnote1 Hebrew ki has been described as a polyfunctional marker projecting reference to a cause/reason for an event, state, or belief in the extralingual world, or projecting an account for an action in the discourse realm (Glinert, Citation1989; Livnat & Yatziv, Citation2003; Maschler, Citation1994; cf., e.g., Degand, Citation2000; Ford, Citation1993; Günthner, Citation1996; Li, Citation2016; Schiffrin, Citation1987; Spooren et al., Citation2010; Sweetser, Citation1990 for “equivalents” of ki in other languages). We focus here on ki-clauses by which speakers provide accounts for their responsive disaffiliative moves.Footnote2

Disaffiliative moves are normally dispreferred (Sacks, Citation1987; Schegloff, Citation2007; Schegloff & Sacks, Citation1973) format actions, which are generally destructive of social solidarity (Heritage, Citation1984a, p. 269). In such contexts, a range of different first actions—such as requests, offers, or assessments—receive a rejection or other response that does not support or endorse the first speaker’s stance or point of view (cf., Pomerantz, Citation1984; Stivers, Citation2008). Accounts have been shown to be regular components of disaffiliative moves in English and Japanese talk-in-interaction (Couper-Kuhlen & Selting, Citation2018, p. 455; Ford, Citation2001; Ford & Mori, Citation1994; Mori, Citation1994, 1999; Pomerantz, Citation1984; Robinson, Citation2016; Sacks, Citation1987) and, as found in this study, in Hebrew as well.

We have found that when speakers establish a disaffiliative context, accounts provided by ki-clauses tend to have two prominent features. In terms of content, the accounts appeal to (assumed) shared knowledge of the participants. In terms of form, such accounts tend to be accompanied by the Palm Up Open Hand gesture (PUOH; see see below: Previous Studies: The Palm Up Open Hand gesture, visibility, and obviousness), which, in its prototypical realization, manifests a rotation of the speaker’s forearm so that the extended or semi-extended palm turns upward (; see discussion on variations in manifestation of this gesture in Section on data and methodology (below).

Based on the observation that speakers accompany ki-clauses with the PUOH while providing accounts based on (assumed) shared knowledge, and defining epistemic stance as “different ways of showing commitment towards what one is saying” (Kärkkäinen, Citation2003, p. 19), we suggest that through this gesture, speakers convey an epistemic stance toward their accounts (cf., Marrese et al., Citation2021). It is in this sense that the PUOH can be described as constituting an embodied stance marker. As such, our study frames the relation between causality and epistemicity as a joint communicative project. Moreover, in line with previous research (e.g., Debras, Citation2017; Ford et al., Citation2012; Goodwin, Citation2009, 2018; Inbar, Citationin press; Jehoul et al., Citation2017; Marrese et al., Citation2021; Shor & Marmorstein, Citation2022), the present study shows that embodied resources can be mobilized to display a speaker’s stance and make it interpretable, thereby furthering our understanding of the grammar–body interface.

Shared knowledge in which speakers ground their accounts may range from factual information with which interlocutors are familiar to general knowledge pertaining to general social conduct, “ways of being-in-the-world” (Heidegger, Citation1927; see also, Clark, Citation1996; Garfinkel, Citation1967; Wittgenstein, Citation1953). In Garfinkel’s (Citation1967) words, this includes “common sense knowledge of social structures, and of practical sociological reasoning” (p. vii). We suggest that invoking equality of access to the referred situation or state of affairs provided as an account for the disaffiliatve move may mitigate threats to social solidarity and strengthen social relations, as management of congruency of epistemic stances between participants leads to affiliation (see Asmuß, Citation2011; Clayman & Raymond, Citation2021b; Heritage, Citation2013; Heritage & Raymond, Citation2005; Jefferson, Citation1972).

Following a short review of the relevant literature and presentation of our data and methodology, we illustrate ki-clauses accompanied by the PUOH that appeal to shared knowledge, distinguishing between shared information provided at the level of explicature and presuppositions. We then provide a contrastive example in which the speaker provides a ki-prefaced account in a disaffiliative context, oriented to knowledge that is not held in common. Following an examination of the details of turn and action design in the environments wherein such accounts occur, we discuss our findings and conclude the study.

Previous studies: The Palm Up Open Hand gesture, visibility, and obviousness

In the field of gesture studies, the PUOH is conceived of as derived from actions of object transfer, such as presenting, offering, or handing over (e.g., Cooperrider et al., Citation2018; Lopez-Ozieblo, Citation2020; Müller, Citation2004; Streeck, Citation2009). Although this gesture may have a referential nature while representing such everyday actions, it is often used as a recurrent gesture (e.g., Cienki, Citation2015, pp. 506–508; Harrison, Citation2018, §1.4; Harrison et al., Citation2021; Kendon, Citation2004, p. 227; Ladewig, Citation2014; McNeill, Citation2018; Müller, Citation2017) with primarily pragmatic functions associated with delivery of information (Bavelas et al., Citation1995; Kendon, Citation2004; Müller, Citation2004). Following Harrison (Citation2018), “recurrency is a dimension of gesture form and function that leads to the repeated performance of similar gestures to achieve similar functions by different speakers in different contexts” (p. 8).

Müller (Citation2004) hypothesized that, by metaphorical presentation of the discursive “object” on an open hand, speakers perform it as visible, offering it for joint inspection. Visible things—that is ones shared by virtue of being potentially perceived by all—can also be said to be “obvious.” Indeed, studies from different theoretical backgrounds have shown that the PUOH is often associated with obviousness and shared knowledge (e.g., Bavelas et al., Citation1995; Calbris, Citation1990, p. 187; Cooperrider et al., Citation2018; Kendon, Citation2004; Lopez-Ozieblo, Citation2020; Marrese et al., Citation2021; McNeill, Citation1992, p. 198; Müller, Citation2004).

Moreover, in many languages, the visual domain is used to structure the description of our intellectual processes, such as knowing, understanding, and certainty (Sweetser, Citation1990, pp. 39–40). In Hebrew, for example, the connection between such mental states and vision is reflected in lexemes, such as polysemic barur, whose abstract sense “evident” is metaphorically derived from its concrete sense “clearly visible”; lehavin (“to understand”) and muvan (“understandable”) are both etymologically derived from the root √b.i.n., which has to do with “observing, watching” (lehitbonen, “to observe”); most scholars believe that the epistemic particle harey, often glossed as “as you know,” originates from Aramaic “see” (e.g., Mor, Citation2006). Interestingly, many of these expressions were observed in our data to be often accompanied by the PUOH. As noted by Sweetser (Citation1990), physical sight as a metaphorical domain of knowing has its basis in the primary status of vision as a source of data: Cross-linguistic studies of evidentials show that direct visual evidence is considered the strongest and most reliable source of data, the most certain kind of knowledge (pp. 33, 39).

Recent interactional linguistic studies of perception verb constructions (e.g., San Roque et al., Citation2018) point to some interactional origins of such metaphorical extensions. In the particular case of visual perception, which Müller associated with the PUOH (Müller, Citation2004), constructions involving the verb “see” in various (typologically unrelated) languages—such as Hebrew 'at/a ro'e/a? (“you see?”; see Miller Shapiro, Citation2014; Polak-Yitzhaki, Citation2020; Polak-Yitzhaki et al., Citation2021); Arabic raʔā (“see”), particularly in dialects (Taine-Cheikh, Citation2013); Estonian näed (“you see?”; see Keevallik, Citation2008; Polak-Yitzhaki et al., Citation2021), and English see? (Kendrick, Citation2019)—have been shown to manifest an evidential use in interaction, inviting the interlocutor to share the speaker’s perception and understanding that the just prior turn, action, or event serves as evidence for the speaker’s argument (Polak-Yitzhaki et al., Citation2021, cf., Kendrick, Citation2019). Furthermore, Polak-Yitzhaki (Citation2020) found that when Hebrew 'at/a ro'e/a (“you see?”) is employed in this evidential manner, it is often accompanied by the PUOH (cf., Calbris, Citation1990, p. 187, for French vous voyez).

The PUOH is characterized by a post-stroke hold, a brief but visible suspension of the gesture from a dynamic to a static position, before retracting or beginning the next gesture (e.g., Kendon, Citation1980; Kita et al., Citation1998; Bressem & Ladewig, Citation2011). Sikveland and Ogden (Citation2012) showed that in Norwegian interactions, participants may orient themselves to held gestures in general, beyond the end of the turn-at-talk, as displays of occasions in which participants do not (yet) have a shared understanding. Thus, the suspension of the PUOH may be seen to be inextricably linked to disaffiliative contexts in which shared understanding and affiliation have not (yet) been established.

Data and methodology

The current study is part of a larger project in which we examine the use of Hebrew ki-clauses in interaction. The study is based on the Haifa Multimodal Corpus of Spoken Hebrew (Maschler et al., Citation2023), consisting of casual, everyday conversation among friends and relatives, video-recorded over the years 2016–2023. Informed consent for collection and publication of the data was obtained from all participants.Footnote3 The corpus is segmented into intonation units (Chafe, Citation1994), transcribed following Du Bois (Citation2012) as adapted for Hebrew (Maschler, Citation2017; see Appendix).Footnote4 The transcription of embodied conduct in the excerpts below follows Mondada (Citation2019). At the time of data collection, this corpus comprised ca. five hours (298 minutes) of talk among 20 participants, in nine different interactions. This corpus manifests altogether 318 tokens of the causal conjunction ki.

As we explored the data, we noticed that the most frequent gesture that was coordinated with ki-clauses in general was the PUOH. We found that such ki-clauses generally emerged within a variety of sequences—for example, following responsive disaffiliative moves, such as opposition, disagreement, or rejection—or when speakers anticipate a possible problem with comprehension of their immediately prior utterance, prompted by exaggeration, contradictions, and so on. In this latter type of sequence, the addressee may have displayed misunderstanding or doubt through either verbal or embodied conduct. The current study focuses exclusively on the action of providing an account in the sequential environment of a responsive disaffiliative move, in order to determine what integration of the PUOH adds to the actions accomplished by ki-clauses in this sequential position.Footnote5

Of the 318 ki-clauses in our database, 43 occurred in responsive disaffiliative moves. Of those 43, 33 convey information that appeals to the participants’ shared knowledge. Of those 33 cases, 19 (ca. 58%) are accompanied by the PUOH. It should be noted, however, that in nine of the remaining 14 ki-clauses conveying shared knowledge in responsive disaffiliative moves, the speaker’s hands were occupied in some way or other, either with activities such as eating or closing a window or performing movements that regulate the state of the speakers or their relationship with other persons or objects, such as body scratching or holding something (adaptors, e.g., Ekman & Friesen, Citation1969). Thus, the only pragmatic gesture found in such sequences was the PUOH. Furthermore, the PUOH was not found in any of the remaining 10 cases of ki-clauses in disaffiliative moves (those not appealing to shared knowledge). Even though the PUOH—an embodied action pervasive in Hebrew interaction—is by no means restricted to causal clauses, the frequent and systematic occurrence of this gesture alongside ki-clauses in this particular sequential position, which our data attest, requires explanation.

We are taking the view that the PUOH, as a recurrent gesture (e.g., Ladewig, Citation2014), is a gesture type, or gesture family. Therefore, although the PUOH is usually characterized by a rotation of the speaker’s forearm so that the extended or semi-extended palm turns upward (see ), such a form should be seen as a prototype of the gesture (cf., Cienki, Citation2016), as in many contexts it can be realized in various configurations (see, for example, Figures 3 and 5, below), depending on different factors, such as physical environments (Clift, Citation2020) or verbal contexts (Müller, Citation2004). In other words, its forms may appear diverse, forming a continuum in terms of the different degrees of exertion involved in their production (Cienki, Citation2021). As was noted by one of the reviewers of this article, such a diversity of forms raises “a conundrum in trying to ‘objectify’ gesture descriptions/function assignments.” To confront the challenge of operationalizing with this variety of forms in interaction, we adopted the following methodology: Once the contexts of use were established based on the prototypical form of the PUOH, the less prototypical, although kinetically related, manifestations of the gesture were also considered.

In what follows, employing interactional linguistic methodology (Couper-Kuhlen & Selting, Citation2018) and multimodal conversation analysis (e.g., Goodwin, Citation2018; Mondada, Citation2006), we analyze sequential environments yielding such multimodal patterns. We focus on what the embodied resource of the PUOH accomplishes in the moment in which it is produced.

Shared knowledge residing in ‘what is said’

Our first excerpt illustrates an account based on shared knowledge that consists of information held in common among co-participants delivered explicitly. This account is provided for a contrastive assertion offered in response to an assertion made by the interlocutor. The extract is drawn from a face-to-face conversation between two friends, Eyal and Aya.Footnote6 Eyal tells Aya that he had suggested to his girlfriend Kati that they officially move in togetherFootnote7Excerpt 1: ‘Let’s move in together’ (From ‘Ammonia leak’ 00:36)

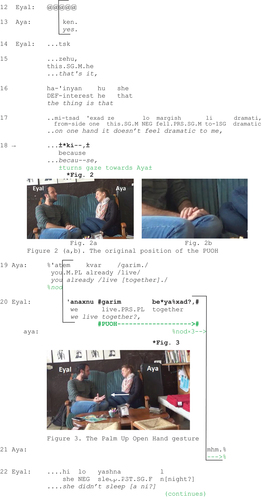

Aya responds to Eyal’s informing (lines 1–5), saying that it is a much more “dramatic” telling than she had expected upon hearing Eyal’s opening (lines 6–8, 11). Following a humorous clarification request from Eyal concerning what exactly she found “dramatic” (lines 9–10) and Aya’s humorous confirming response (line 13), Eyal begins with a cluster of two discourse markers composed of a click (Maschler, Citation2002) projecting a transformative response (Ben Moshe & Maschler, Citation2019; cf., Stivers & Hayashi, Citation2010) and the particle zehu lit. (“that’s it”; see Bardenstein et al., Citation2020) followed by the projecting construction (Auer, Citation2011Citation2005) ha'inyan hu she- (“the thing is that”; cf., Günthner, Citation2011; lines 14–16)—all projecting that what is about to follow will be contrary to what was just said by Aya: namely, that Eyal’s suggestion to Kati was “dramatic.” In line 17, Eyal indeed explicitly provides a contrasting assertion: ze lo margish li dramati (“it doesn’t feel dramatic to me”) by which he (momentarily)Footnote8 disagrees with Aya’s statement. This assertion ends in mid-level, mid-rise, mid-fall intonation, projecting continuation in Hebrew (hereafter, “continuing intonation,” Du Bois, Citation2012, p. 5.3), most probably an account. Indeed, turning his gaze to Aya, in line 18, Eyal produces the causal conjunction ki (“because”) as a separate intonation unit, also realized in continuing intonation, projecting more strongly that an account for his contrasting assertion will follow. Moreover, the causal conjunction ki being offered up in its own intonation unit (line 18) might be argued as a momentary claim that, from the speaker’s perspective, the account is/should be commonsensical and self-evident (cf., Bolden & Robinson, Citation2011, pp. 101, 106).

The statement anaxnu garim beyaxad (“we live together,” line 20), presented as the account for Eyal’s previous assertion, is coordinated with the PUOH performed with both hands (Figure 3). The original position of the PUOH is with the speaker’s hands on his legs, left hand resting on the right hand (Figure 2). As Eyal utters his account (line 20), his hands turn out from the lower arms reaching a palm-up position in a somewhat less effortful instantiation of the gesture, and then return to their original position. This account serves as an affiliative reminder of knowledge that the interlocutor already possesses, as evident in Aya’s utterance of line 19, partly overlapping Eyal’s account. Moreover, the account is produced in rising intonation (line 20), also characterized as “try-marked” intonation (Sacks & Schegloff, Citation1979)—an intonation contour that in Hebrew is designed to seek a (minimal) response from the listener while projecting “more to come” (hereafter, “continuing appeal intonation,” Du Bois, Citation2012, p. 5.3)—requesting Aya’s confirmation that this information is not new to her. Indeed, Aya confirms with nodding and a mhm (lines 20–21), the former of which may be seen as a token of affiliation (Stivers, Citation2008), and Eyal continues elaborating on Kati’s living situation (line 22 and on).

Shared knowledge as a presupposition

Whereas in the speaker appeals to information shared between the particular interlocutors by virtue of their prior mutual acquaintance, in , the account is based on general knowledge assumed to be shared by all speakers belonging to the speech community (Gumperz, Citation1968, p. 463)—namely, that Canon is known as a good camera brand. The speaker appeals to this knowledge as a presupposition, while the explicit information conveyed as an account is (probably) unknown to the addressee. is taken from a conversation between three female friends in their early 20s discussing what would be the best camera for Tom to buy for her upcoming post-army trip to the Far East. Adi mentions her cousin’s compact camera, which is, in her opinion, suitable for Tom: Excerpt 2: ‘Camera’ (From ‘Sponsored by dad’ 5:15)

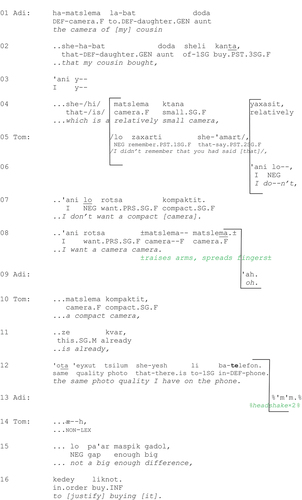

In response to Adi’s suggestion that Tom buy a compact camera like Adi’s cousin’s (lines 1–4), Tom announces that she is not interested in compact cameras (lines 6–7); she wants a “camera-camera” (line 8), depicting a “real” large camera by raising her arms and spreading her fingers. Adi displays understanding with the Hebrew change-of-state token 'ah (“oh,” line 9; Maschler, Citation1994; cf., Heritage, Citation1984b). Tom then presents her argument for preferring a larger camera and rejecting Adi’s suggestion: A compact camera has the same photo quality she already has on her cellphone (lines 10–12).

Adi expresses her disagreement with Tom’s assertion with an 'm'm accompanied by two headshakes (line 13). Tom dismisses Adi’s disagreement with the nonlexical vocalization æ--h (line 14) and claims that the difference between a compact camera and a cellphone camera does not justify buying a compact camera (lines 15–16). This assertion, followed by be'emet (“really,” line 17) functioning to negate any doubt (Maschler & Estlein, Citation2008), is strongly designed for receiving acceptance and agreement. Indeed, in line 20, Adi produces the negator lo (“no”), used here as an interactionally preferred response to a prior negatively framed utterance, implementing agreement (e.g., Heinemann, Citation2005; Jefferson, Citation2002). However, then, following a longer than average pause, Adi produces a contrastive assertion prefaced by 'aval (“but,” line 21), claiming that the camera she had suggested is still a good one for taking on trips (line 22). This disaffiliative move is immediately followed by an account: hi shel kan. kenon “it’s a Kun. Canon,” lines 24–25). Adi’s account is projected by the continuing intonation ending her contrastive assertion (line 22), and it is explicitly designed as such by being prefaced by the causal conjunction ki (“because”) in a separate intonation unit, also in continuing intonation (line 23). Adi first mispronounces the make of the camera as kan- (line 24) but then self-repairs to kenon, in high rising intonation (line 25), appealing to the interlocutor (Du Bois, Citation2012, p. 5.3; Du Bois et al., Citation1992, p. 30) for confirmation of the self-repaired version. This appeal implies that Adi assumes that Tom is familiar with this camera brand. Tom confirms with a nod (line 26), showing that she is indeed familiar with Canon cameras.

The account—namely, that the camera is “a Canon”—is coordinated with the PUOH (see Figure 5). The gesture originates from the hands joined and placed on the speaker’s legs (Figure 4). As Adi presents her account (line 24), her hands turn out from the lower arms reaching a palm-up position, and then return to their original position. In this case, the speaker appeals to the shared knowledge concerning the high quality of cameras made by Canon as a presupposition, whereas the explicit information conveyed—that the suggested camera is made by Canon—is probably unknown to the addressees. The appeal to this shared knowledge forms part of the speaker’s strategy of making yet another effort at convincing Tom that the camera is suitable for her. Indeed, in lines 27 and 29, Adi adds that the camera is tova (“good”) and Amit, the third participant, shows interest in the camera, asking about its price (line 28).

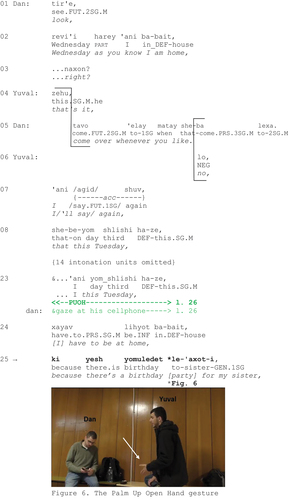

Our next excerpt is based on shared knowledge pertaining to general social conduct (Garfinkel, Citation1967). This type of knowledge is common to the interlocutors by virtue of their common life experience (Bourdieu, Citation1990 [1980]; Clark, Citation1996; Heidegger, Citation1927; Wittgenstein, Citation1953) and shared prior-text (Becker, Citation1979). comes from an interaction between two students: Dan and Yuval. Prior to the extract in , Dan had invited Yuval to come over for a study “Marathon,” and Yuval had rejected the offer to come that day, suggesting Wednesday instead, and mentioning that he is free in principle until 6 p.m. Dan responds: Excerpt 3: ‘Sister’s birthday’ (From ‘University of Haifa 2’ 17:34)

In response to Yuval’s saying that he could probably come over on Wednesday and study with Dan until about 6 p.m. (not shown), Dan says that he’ll be home all day Wednesday, and therefore Yuval could come over as early as he’d like to that day (lines 1–3, 5). In response to this proposal, Yuval produces the particle zehu lit. (“that’s it,” line 4), projecting that he is going to oppose the proposal to come early on Wednesday (Bardenstein et al., Citation2020). Indeed, partly overlapping Dan’s proposal, Yuval rejects it with lo (“no,” line 6). He then begins recounting something he has to do that Tuesday (lines 7–8) and, following an insertion about a hypothetical situation in which he would have been able to come already on Tuesday (not shown), returns to this point in line 23, asserting that this particular Tuesday he must be home (lines 23–24) because his sister is having a birthday party and his family would like him there (lines 25–26). In line 36, Yuval asserts that after this celebration he intends to wake up late the next morning and, following a long pause, adds that he’ll take the opportunity to sleep in (line 37). The implication is that he is rejecting Dan’s invitation to get to his place early Wednesday morning.

An account for this disaffiliative move—ki yesh yomuledet le-'axot-i, ve-rotsim she-'ani 'ehye sham (“because there’s a birthday [party] for my sister, and they want me to be there,” lines 25–26)—is produced ending in continuing appeal intonation, seeking a (minimal) response from the listener (Du Bois, Citation2012, ch. 5.3). In response, Dan shifts his gaze from his cellphone to Yuval, and Yuval upgrades his assertion concerning the family event, adding that his sister will be celebrating turning 12 years old (line 27), a landmark in Jewish tradition, to which Dan responds with the non-lexical vocalization ya'a (line 29), which may be interpreted here as an enthusiastic change-of-state token (cf., Heritage, Citation1984b), and with congratulations (line 31). Yuval acknowledges with ken (“yes,” line 32) and repeats that he therefore has to be at home (lines 33–34). Although Dan was most likely not aware of the fact that Yuval’s sister was having a birthday that Tuesday, as suggested from his response with the enthusiastic change-of-state token (cf., Heritage, Citation1984b) ya'a (line 29), the presupposition that one must participate in one’s sister’s twelfth birthday party, qualifies the account as valid for the refusal to come over early on Wednesday.

It is plausible that from the beginning Yuval had intended to present as account this information concerning his sister’s birthday party, his mentioning of Tuesday already in line 8 supports this conjecture. This may explain the early deployment of the PUOH, maintained throughout the production of the whole stretch of talk that comprises the implicit rejection of Dan’s invitation and its uncontroversial argumentation (lines 23–26), including part of the insertion about the hypothetical situation in which he would have been able to come (lines 16–22, not shown).Footnote9 Thus, the gesture not only indexes that the account is based on shared knowledge—in this case, shared knowledge pertaining to general social conduct—its early deployment may also trigger the prediction of such an account being produced (cf., Holler & Levinson, Citation2019).

In this example, the PUOH is performed in a beat-like fashion (McNeill, Citation1992, p. 80). The beats are produced in accordance with each prosodic unit, delivering strongly emphatic speech in which Yuval shows his involvement (Ferré, Citation2011). The repetitions of the PUOH may also symbolize a listed sequence of different discursive objects (Müller, Citation2004, p. 245), which Yuval puts forward as an account for declining Dan’s invitation. Furthermore, as shown by Streeck (Citation2009, pp. 116–117), speakers often intensify their gestures in order to gain their addressees’ attention—something Yuval may be doing here, in addition to the continuing appeal intonation (line 26), in order to regain the gaze of his interlocutor, who has been busy with his cellphone (lines 22–26). Indeed, Yuval withdraws his PUOH as soon as Dan begins to return his gaze to him (lines 26–27).

Accounts based on knowledge that is not assumed to be held in common

Our final excerpt presents a contrastive example, in which the speaker provides an account based on information that is not assumed to be shared among the participants. Although the ki-clause appears in a disaffiliative context, it is not accompanied by the PUOH. Such examples are fewer in number, suggesting that speakers tend to ground their accounts for disaffiliative moves in information held in common.

Prior to the extract in , Alex had been telling Dotan about the tonal system in Mandarin Chinese, specifically, that the meanings of lexemes can be differentiated based solely on their tones. Excerpt 4: ‘Asian tunes’ (From ‘Chinese poetry’ 2:05)

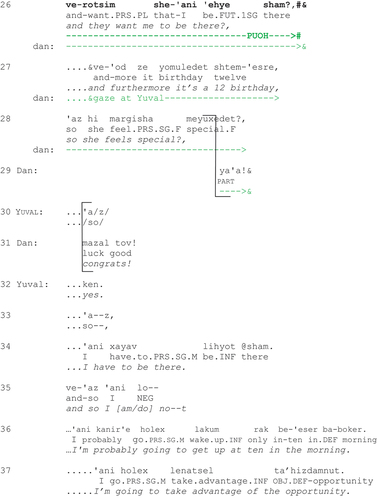

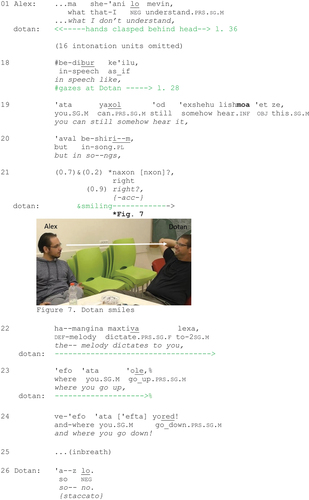

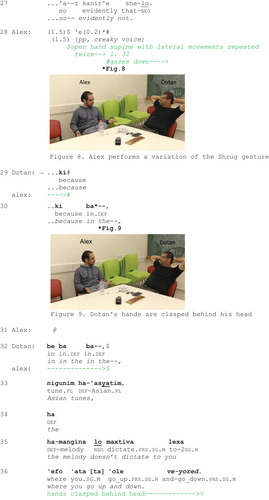

Following a short mutual musing at the peculiarities of the Mandarin Chinese tonal system (not shown), Alex continues the matter he had begun earlier: In speech it is still possible to somehow hear the Mandarin Chinese tones (and, subsequently, to distinguish between lexemes; lines 18–19), but what he doesn’t understand is how the tonal system works in songs (lines 1, 20). Dotan smiles (Figure 7) following the mention of “songs” at line 20, perhaps projecting an upcoming disagreement (Bousmalis et al., Citation2013, p. 206). By employing the discourse marker naxon (“right”) in continuing appeal intonation (line 21), Alex requests confirmation for his previous utterance concerning songs (line 20) while also framing his upcoming elaboration of it as something Dotan is supposed to agree with, in an attempt to increase the addressee’s involvement in the discourse and create alignment (e.g., Maschler & Miller Shapiro, Citation2016). Alex then elaborates that in songs it is the melody that dictates the tones (rather than the meanings of the words, as usually happens in Mandarin Chinese; lines 22–24). Alex’s turn is strongly designed for acceptance and agreement (Pomerantz, Citation1984). It is produced at a higher volume, suggesting Alex’s certainty regarding his assertion. Moreover, the impersonal use of the second person pronouns lexa (“to you,” line 22) and 'ata (“you,” lines 23–24) is designed to create solidarity with the interlocutor (e.g., Tobin & Stern-Perez, Citation2009). Such pronouns often occur in discourse situations in which speakers convey a generally admitted truth or personal opinions that they believe are shared (Kitagawa & Lehrer, Citation1990; Laberge & Sankoff, Citation1979, p. 275). Yet Dotan disagrees here with a staccato 'a--z lo “so--no,” line 26), and then repeats his disagreement adding kanir'e (“evidently,” line 27). In response, Alex performs a variation of the shrug gesture (e.g., Debras, Citation2017; Streeck, Citation2009, p. 191), which includes a component of rotating his forearms outward with extended fingers to a palm up position, moving his arms twice away from his body and then back (lines 28–32; Figure 8) while voicing a creak (line 28). In the given context, the gesture can be interpreted as displaying puzzlement and soliciting an account for Dotan’s disaffiliative move. Indeed, prefaced by ki (lines 29–30), Dotan explains in response that in Asian tunes in general it is not the case that the melody dictates the tones (lines 32–36). Because the information presented as Dotan’s account (lines 32–36) contradicts Alex’s statement (lines 20, 22–24), it cannot be assumed by Dotan to be held in common between them at the moment, and the account is indeed not coordinated with the PUOH. The speaker’s hands are clasped behind his head throughout this entire excerpt (Figure 9).

Discussion

Our study shows a recurrent systematic arrangement of a manual and a vocal practice, which participants locally assemble in disaffilative sequences for constructing accounts based on shared knowledge. We suggest that the PUOH, co-occurring with ki-clauses in such environments, can be interpreted as a device presenting the account as based on shared knowledge, and as such, can be seen as an addressee-oriented move that serves as an invitation to consider the speaker’s account as valid, encouraging the co-participant to affiliate. Embodied conduct thus functions here to reinforce actions accomplished vocally. In some cases, the PUOH is associated with accounts that serve as a form of reminder of information that the interlocutor was (supposed to have been) aware of or had access to (). The assumption that the information conveyed is held in common can be based on specific details derived from joint past experiences, including prior conversation. We showed that speakers can appeal to shared knowledge also as a presupposition. In such cases, although the information provided as account is not shared, participants share a presupposition pertaining to some general knowledge () or social conduct () that are referred to by such accounts.

Even if recipients lack the particular knowledge of the generic information (cf. ) or knowledge pertaining to general social conduct (cf. ), they can acquire it from being recipients of the very practice itself of presenting accounts coordinated with the PUOH and, as such, marked as shared knowledge. Thus, this practice can be seen as an interactional process of how participants create the very reality of, for example, Canon being so “obviously” a good camera brand or of the obligation to attend a sister’s birthday party (cf., Berger & Luckmann, Citation1966). This is another reason why the same practice can be used for both “knowing” and “unknowing” recipients.Footnote10 In this way, grammar intersects with normative understandings about the world and thus with how participants establish intersubjectivity (Raymond, Citation2019).Footnote11

In the conversation-analytic and ethnomethodological traditions, common ground—or intersubjectivity—constitutes a central feature of interaction (e.g., Heinemann et al., Citation2011; Lindström et al., Citation2021; Stivers et al., Citation2011). The centrality of shared knowledge to talk is evident in that languages provide resources such as epistemic particles like Hebrew harey (Ariel, Citation2010), Danish jo, Swedish ju (Heinemann et al., Citation2011), English oh (Heritage, Citation1998), and constructions “equivalent” to English you know (e.g., Asmuß, Citation2011; Clayman & Raymond, Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Jefferson, Citation1972; Keevallik, Citation2003; Lindström & Wide, Citation2005; Maschler, Citation2012), dedicated to pointing out that information is shared. Some of the studies quoted above link such constructions to dealing with problems and potential disagreement in talk, showing that the appeal to shared knowledge is a resource for establishing agreement (e.g., Asmuß, Citation2011; Clayman & Raymond, Citation2021b; Heritage, Citation2013; Jefferson, Citation1972; Keevallik, Citation2003; Maschler, Citation2012). In a similar vein, our study suggests that accounts based on shared knowledge serve as a relevant premise for the speaker’s disaffiliative move, implying that a disaffiliative move was reasonable under the circumstances referred to in the ki-clause. The deployment of the PUOH in such environments may qualify an account as valid for the disaffiliative move, creating a rather strong plea for shared understanding and affiliation.

In a recent multimodal conversation analytic study of the PUOH, Marrese et al. (Citation2021) studied a publicly accessible online corpus of videos in which people were challenged for speaking languages other than English in public. In this highly conflictual context, the PUOH was found to often be employed in argument sequences, at a point in which participants reach what the authors termed an “impasse,” “where both sides maintain opposing stances, and neither gives way to their opponent” (p. 13). The authors suggested that at such moments in interaction, “participants can employ the PU gesture to not only pursue a previously established position, but also take an epistemic stance to index the obviousness of that position in the face of attempted counteractions by the recipient” (emphasis added).

The current study explores employment of the PUOH in casual conversation, albeit in far less conflictual environments, grounding the obviousness often associated with this gesture in the participants’ shared knowledge. Consider the account in , based on the shared knowledge of the speakers: The speaker and his girlfriend do not officially live together. However, if practically speaking they do live together, then it is obvious that it doesn’t feel “dramatic” for the speaker to suggest to his girlfriend that they officially move in together. Under such circumstances, the disaffiliative move of the speaker—a contrastive statement—is captured as reasonable, and shared understanding and affiliation can be established. The account in is based on information that is more generic: Canon is a company known for its high-quality cameras. Therefore, if the suggested camera is made by Canon, then it is obvious that it is good, and disagreeing with the interlocutor is reasonable. The account provided in is based on knowledge pertaining to general social conduct. If the speaker’s sister is having a birthday party, then it is obvious that he must attend. Therefore, the speaker’s refusal to go over to his friend’s place is understandable: He will not be able to come. These examples, then, illustrate how shared knowledge, obviousness, and the PUOH can be related in interaction. Indeed, throughout our data, when accounts provided in disaffiliative contexts did not involve reliance on shared knowledge, there was also no deployment of the PUOH (e.g., ).

Conclusions

The foregoing study reveals the moment-by-moment emergence of an adverbial clause-combining pattern in Hebrew talk-in-interaction in response to the on-line unfolding of turns and actions, and it explores the ways this unfolding in time is intimately intertwined with participants’ embodied conduct. In this we hope to have contributed to the recently growing field investigating the grammar–body interface in the emergence of complex syntax in interaction (e.g., Ehmer et al., Citation2016; Keevallik, Citation2013; Maschler et al., Citation2020).

More specifically, by considering the gestural practice we focus on alongside the verbal resource of ki-clauses that appeal to (assumed) shared knowledge, our study contributes to an embodied conceptualization of grammar—epistemicity, and proposes new lines of inquiry for delving deeper into the different uses of the PUOH. Our study shows that the PUOH can modify ki-prefaced accounts based on shared knowledge, independently of verbal expressions used to build common ground and appeal to understanding, certainty, or evidentiality.Footnote12 Whereas the study by Marrese et al. (Citation2021) used the sequentiality of the interaction to ground the claims of obviousness often recognized with the PUOH, the current study grounds it primarily in commonsensicality. As such, our study points out that the epistemic work that the PUOH does can have different “groundings”—be it the progression of the talk thus far (Marrese et al., Citation2021) or cultural/commonsense understandings.

Moreover, the use of the PUOH as a means for establishing the speaker’s position by appeal to epistemicity (albeit in different sequential environments) has already been observed by Mondada (Citation2015, p. 280). The author suggested that in environments in which speakers compete regarding their epistemic superiority, the PUOH, as a gesture of presentation of contents (e.g., Kendon, Citation2004), may be considered as indexing the authority of the speaker concerning this content. In the environments presented in our study, however, the gesture indexes not the speaker’s epistemic authority but the authority of the knowledge itself, which stems from a high level of factuality by virtue of being shared by the speaker and the addressee. Thus, our study confirms that the understanding of gestures is sensitive to how they temporally and sequentially relate to environing talk (e.g., Clift, Citation2020; Mondada, Citation2018; De Stefani, Citation2022).

The frequent and systematic co-occurrence of the PUOH with accounts, as attested in our study, confirms that the action of offering an account is often intertwined with epistemicity—pointing out shared epistemic access. Indeed, in some languages, the connection between causality and shared knowledge has become grammaticized into the conjunction paradigm, and specific causal conjunctions or particles are dedicated to presenting an account as based on the common ground of the speakers. In Russian, for example, the particle ved’ (“because”) introduces an utterance as an obvious cause/motivation, whereas an “ordinary” causal conjunction, potomu shto “because,” may be used in all contexts (Podlesskaya, Citation1993). Unlike English because, the causal conjunction since tends to express epistemic stance, such that clauses within its scope are seen as representing “factual” or presupposed information (Dancygier & Sweetser, Citation2000). In formal, written registers of Hebrew, the causal conjunctions sheharey (“because”) and sheken (“because”) are dedicated to presenting accounts that comprise shared knowledge of the speaker and the addressee, (Bliboim, Citation2003). We have shown that in Hebrew talk-in-interaction, however, such features tend to be indicated in gestural formats co-occurring with ki-clauses.

By showing interrelatedness of knowledge and affiliation, this study supports the view that questions of epistemics play an important role in the negotiation of shared understanding and agreement in talk (e.g., Asmuß, Citation2011; Clayman & Raymond, Citation2021b; Heritage & Raymond, Citation2005). Hence, the PUOH co-occurring with accounts emerging in disaffiliative environments may be seen as a resource in interaction promoting a sense of shared understanding and enhancing social affiliation among the speakers, providing a platform of shared perspective from which participants can progress with the activity in which they are engaged. The appeal to shared knowledge by employing the PUOH suggests that verbal and embodied resources operate conjointly in creating a rather strong plea for shared understanding and affiliation.

Finally, the study of embodied conduct accompanying Hebrew ki-clauses not only contributes to a systematic analysis of causal clauses but also, by framing the relation between causality and epistemicity as a joint communicative project, validates an interrelation between these domains and suggests an interactional source for their interrelatedness.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Hebrew has numerous strategies for providing accounts, such as prefacing by a variety of conjunctions, for example, mishum she-, mikevan she-, biglal she- sheken, etc., as well as asyndetic constructions. The division of labor concerning these strategies in face-to-face interaction has not yet been explored in detail. In this study, we focus solely on ki-clauses, the most common causal conjunction in our data.

2 It should be noted that ki occurs in other environments and has a variety of additional functions throughout our data (see Inbar & Maschler, Citationforthcoming).

3 Ethical and legal permission to conduct the study was granted by the Faculty of Humanities’ IRB Committee, University of Haifa (permission #095/23).

4 As the intonation unit has proven a crucial unit of analysis in studies of this corpus, it has been transcribed according to the Santa Barabara school, in which this prosodic unit plays a most central role.

5 For a study of the other environments in which ki-clauses accompanied by the PUOH are found in our data, see Inbar and Maschler (Citationforthcoming).

6 The clips (including English subtitles) are available at https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/16U9o4rEqyNmCWwp4nDuYd6JTzTSpIonU?usp=sharing.

7 For transcription conventions, see the Appendix.

8 The discourse marker mitsad ‘exad “on the one hand” (line 17) projects a contrasting second part to Eyal’s response, which will likely open with mitsad sheni “on the other hand,” which is indeed verbalized 16 intonation units later (not shown). Thus, the disaffiliative move here is projected as momentary.

9 We have removed these lines because of space limitations, but they can be viewed in the video clip (see footnote 5).

10 On the co-incidence of the same marker with information that can be either shared or unshared among interlocutors, see Ariel (Citation2010, pp. 42–43, 163).

11 Intersubjectivity is considered here as an interactional achievement of mutual understanding and coordination around a common activity (e.g., Schegloff, Citation1991).

12 In our corpus, the PUOH is also often coordinated with various expressions referring to shared knowledge, obviousness, and so on, such as the Hebrew equivalents of “you know,” “you see,” and other expressions used to build common ground. What struck a chord was that with ki-clauses the gesture may be seen as signaling shared knowledge independently of verbal expressions dedicated to building common ground.

References

- Ariel, M. (2010). Defining pragmatics. Cambridge University Press.

- Asmuß, B. (2011). Proposing shared knowledge as a means of pursuing agreement. In T. Stivers, L. Mondada, & J. Steensig (Eds.), The morality of knowledge in conversation (pp. 207–234). Cambridge University Press.

- Auer, P. (2005). Projection in interaction and projection in grammar. Text, 25(1), 7–36. https://doi.org/10.1515/text.2005.25.1.7

- Auer, P. (2009). On-line syntax: Thoughts on the temporality of spoken language. Language Sciences, 31(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2007.10.004

- Bardenstein, R., Shor, L., & Inbar, A. (2020). hatseruf zehu ba’ivrit haisra’elit hameduberet [Zehu ‘that’s it’ as a discourse marker in spoken Israeli Hebrew]. Balshanut ‘Ivrit [Hebrew Linguistics], 74, 27–56.

- Bavelas, J. B., Chovil, N., Coates, L., & Roe, L. (1995). Gestures specialized for dialogue. Pspb, 21(4), 394–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167295214010

- Becker, A. L. (1979). Text-building, epistemology, and aesthetics in Javanese shadow theater. In A. L. Becker & A. Yengoyan (Eds.), The imagination of reality (pp. 211–243). Ablex.

- Ben Moshe, Y. M., & Maschler, Y. (2019, June 9–14).Hebrew clicks: From the periphery of language to the heart of grammar [Paper presentation]. 16th International Pragmatics Association conference (IPrA), Hong Kong.

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Doubleday & Company.

- Bliboim, R. (2003). Milot hasiba svivatan hasemantit veshimushan kesimane signon [Causal conjunctions and their use as stylistic markers] [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Bar Ilan University.

- Bolden, G. B., & Robinson, J. D. (2011). Soliciting accounts with ’why’-interrogatives in naturally occurring English conversation. Journal of Communication, 61(1), 94–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01528.x

- Bourdieu, P. (1990 [1980]). The logic of practice ( R. Nice, Trans.). Stanford University Press.

- Bousmalis, K., Mehu, M., & Pantic, M. (2013). Towards the automatic detection of spontaneous agreement and disagreement based on nonverbal behaviour: A survey of related cues, databases, and tools. Image and Vision Computing, 31(2), 203–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imavis.2012.07.003

- Bressem, J., & Ladewig, S. H. (2011). Rethinking gesture phases: Articulatory features of gestural movement? Semiotica, 184(1/4), 53–91. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.2011.022

- Calbris, G. (1990). The semiotics of French gestures. Indiana University Press.

- Chafe, W. (1994). Discourse, consciousness, and time. University of Chicago Press.

- Cienki, A. (2015). Spoken language usage events. Language and Cognition, 7(4), 499–514. https://doi.org/10.1017/langcog.2015.20

- Cienki, A. (2016). Cognitive Linguistics, gesture studies, and multimodal communication. Cognitive Linguistics, 27(4), 603–618. https://doi.org/10.1515/cog-2016-0063

- Cienki, A. (2021). From the finger lift to the palm-up open hand when presenting a point: A methodological exploration of forms and functions. Languages and Modalities, 1, 17–30. https://doi.org/10.3897/lamo.1.68914

- Clark, H. H. (1996). Using language. Cambridge University Press.

- Clayman, S. E., & Raymond, C. W. (2021a). An adjunct to repair: You Know in speech production and understanding difficulties. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 54(1), 80–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1864157

- Clayman, S. E., & Raymond, C. W. (2021b). You know as invoking alignment: A generic resource for emerging problems of understanding and affiliation. Journal of Pragmatics, 182, 293–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2021.02.011

- Clift, R. (2020). Stability and visibility in embodiment: The ‘Palm Up’ in interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 169, 190–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2020.09.005

- Cooperrider, K., Abner, N., & Goldin-Meadow, S. (2018). The palm-up puzzle: Meanings and origins of a widespread form in gesture and sign. Frontiers in Communication, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2018.00023

- Couper-Kuhlen, E., & Selting, M. (2018). Interactional linguistics. Cambridge University Press.

- Dancygier, B., & Sweetser, E. (2000). Constructions with if, since, and because: Causality, epistemic stance, and clause order. In E. Couper-Kuhlen & B. Kortmann (Eds.), Cause, condition, concession and contrast: Cognitive and discourse perspective (pp. 111–142). Mouton de Gruyter.

- De Stefani, E. (2022). On Gestalts and their analytical corollaries: A commentary to the special issue. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v5i2.130875

- Debras, C. (2017). The shrug: Forms and meanings of a compound enactment. Gesture, 16(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1075/gest.16.1.01deb

- Degand, L. (2000). Causal connectives or causal prepositions? Discursive constraints. Journal of Pragmatics, 32(6), 687–707. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00066-1

- Du Bois, J. W. (2012). Representing discourse. Linguistics Department, University of California at Santa Barbara. http://www.linguistics.ucsb.edu/projects/transcription/representing

- Du Bois, J. W., Cumming, S., Schuetze-Coburn, S., & Paolino, D. (1992). Discourse transcription: Santa Barbara papers in linguistics (Vol. 4). University of California.

- Ehmer, O., & Barth-Weingarten, D., (Eds.). (2016). Adverbial patterns in interaction [Special issue]. Language Sciences, 58, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2016.05.001

- Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1969). The repertoire of nonverbal behaviour: Categories, origins, usage, and coding. Semiotica, 1(1), 47–98. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.1969.1.1.49

- Ferré, G. (2011). Functions of the three open-palm hand gestures. Multimodal Communication, 1(1), 5–20.

- Ford, C. E. (1993). Grammar in Interaction. Cambridge University Press.

- Ford, C. E. (2001). Denial and the construction of conversational turns. In J. Bybee & M. Noonan (Eds.), Complex sentences in grammar and discourse (pp. 61–78). John Benjamins.

- Ford, C. E., & Mori, J. (1994). Causal markers in Japanese and English conversations: A cross-linguistic study of interactional grammar. Pragmatics, 4(1), 31–62. https://doi.org/10.1075/prag.4.1.03for

- Ford, C. E., Thompson, S. A., & Drake, V. (2012). Bodily-visual practices and turn continuation. Discourse Processes, 49(3–4), 192–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2012.654761

- Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in Ethnomethodology. Prentice–Hall.

- Glinert, L. (1989). The grammar of modern hebrew. Cambridge University Press.

- Goodwin, C. (1979). The interactive construction of a sentence in natural conversation, and G. Psathas (Ed.), Everyday language: Studies in ethnomethodology (pp. 97–121). Irvington Publishers.

- Goodwin, C. (1984). Notes on story structure and the organization of participation. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action (pp. 225–246). Cambridge University Press.

- Goodwin, C. (2000). Action and embodiment within situated human interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 32(10), 1489–1522. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00096-X

- Goodwin, C. (2009). Interactive footing. In E. Holt & R. Clift (Eds.), Reporting talk: Reported speech in interaction (pp. 16–46). Cambridge University Press.

- Goodwin, C. (2018). Co-operative action. Cambridge University Press.

- Gumperz, J. J. (1968). Types of linguistic communities. In J. Fishman (Ed.) Readings in the sociology of language (pp. 460–472). Mouton.

- Günthner, S. (1996). From subordination to coordination? Verb-second position in German causal and concessive constructions. Pragmatics, 6(3), 323–356. https://doi.org/10.1075/prag.6.3.05gun

- Günthner, S. (2011). N be that-constructions in everyday German conversation. In R. Laury & R. Suzuki (Eds.), Subordination in conversation: A crosslinguistic perspective (pp. 11–36). John Benjamins.

- Harrison, S. (2018). The impulse to gesture: Where language, minds, and bodies intersect. Cambridge University Press.

- Harrison, S., Ladewig, S. H., & Bressem, J. (2021). The diversity of recurrency: A special issue on recurrent gestures. Gesture, 20(2), 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1075/gest.21018.edi

- Hayashi, M. (2005). Joint turn construction through language and the body: Notes on embodiment in coordinated participation in situated activities. Semiotica, 156, 21–53. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.2005.2005.156.21

- Heidegger, M. (1927). Being and time ( J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). Harper & Row.

- Heinemann, T. (2005). Where grammar and interaction meet: The preference for matched polarity in responsive turns in Danish. In A. Hakulinen & M. Selting (Eds.), Syntax and lexis in conversation: Studies on the use of linguistic resourses in talk-in-interaction (pp. 375–403). John Benjamins.

- Heinemann, T., Lindström, A., & Steensig, J. (2011). Addressing epistemic incongruence in question–answer sequences through the use of epistemic adverbs. In T. Stivers, L. Mondada, & J. Steensig (Eds.), The morality of knowledge in conversation (pp. 107–130). Cambridge University Press.

- Heritage, J. (1984a). Garfinkel and ethnomethodology. Polity Press.

- Heritage, J. (1984b). A change-of-state token and aspects of its sequential placement. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 299–345). Cambridge University Press.

- Heritage, J. (1998). Oh-prefaced responses to inquiry. Language in Society, 27(3), 291–334. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404500019990

- Heritage, J. (2013). Epistemics in conversation. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.), The handbook of conversational analysis (pp. 370–394). Blackwell.

- Heritage, J., & Raymond, G. (2005). The terms of agreement: Indexing epistemic authority and subordination in assessment sequences. Social Psychology Quarterly, 68(1), 15–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250506800103

- Holler, J., & Levinson, S. C. (2019). Multimodal language processing in human communication. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 23(8), 639–652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2019.05.006

- Hopper, P. J. (1987). Emergent grammar. In J. Aske, N. Beery, L. Michaelis, & H. Filip (Eds.), Proceedings of the thirteenth annual meeting of the Berkeley linguistics society, 13 (pp. 139–157). Berkeley Linguistics Society.

- Inbar, A. ( in press). The raised index finger gesture in hebrew multimodal interaction. In Gesture.

- Inbar, A., & Maschler, Y. ( forthcoming). A multimodal study of Hebrew ki ‘because’-clauses.

- Iwasaki, S. (2009). Initiating interactive turn spaces in Japanese conversation: Local projection and collaborative action. Discourse Processes, 46(2–3), 226–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/01638530902728918

- Jefferson, G. (2002). Is ‘No’ an acknowledgment token? Comparing American and British uses of (+)/(-) tokens. Journal of Pragmatics, 34(10–11), 1345–1283. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(02)00067-X

- Jefferson, G. (1972). Side sequences. In D. Sudnow (Ed.), Studies in social Interaction (pp. 294–338). Free Press.

- Jehoul, A., Brône, G., & Feyaerts, K. (2017). The shrug as marker of obviousness: Corpus evidence from Dutch face-to-face conversations. In E. Zima & A. Bergs (Eds.), Towards a multimodal construction grammar [Linguistics Vanguard, 3 (s1)]. De Gruyter.

- Kärkkäinen, E. (2003). Epistemic stance in English conversation: A description of interactional functions, with a focus on I think. John Benjamins.

- Keevallik, L. (2003). From interaction to grammar: Estonian finite verb forms in conversation. Uppsala University.

- Keevallik, L. (2008). Internal development and borrowing of pragmatic particles: Estonian vaata/vat ‘look,’ näed ‘you see,’ and vot. Finnisch-Ugrische Mitteilungen, 30/31, 23–54.

- Keevallik, L. (2013). The interdependence of bodily demonstrations and clausal syntax. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 46(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2013.753710

- Keevallik, L. (2018). What does embodied interaction tell us about grammar? Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2018.1413887

- Kendon, A. (2004). Gesture: Visible action as utterance. Cambridge University Press.

- Kendon, A. (1980). Gesticulation and speech: Two aspects of the process of utterance. In M. R. Key (Ed.), Nonverbal communication and language (pp. 207–277). Mouton.

- Kendrick, K. H. (2019). Evidential vindication in next turn: Using the retrospective “See?” in conversation. In L. Speed, C. O’Meara, L. San Roque, & A. Majid (Eds.), Perception metaphor (pp. 253–274). John Benjamins.

- Kita, S., van Gijn, I., & van der Hulst, H. (1998). Movement phases in signs and cospeech gestures and their transcription by human encoders. In I. Wachsmuth & M. Fröhlich (Eds.), Gesture, and sign language in human-computer interaction (pp. 23–35). Springer.

- Kitagawa, C., & Lehrer, A. (1990). Impersonal uses of personal pronouns. Journal of Pragmatics, 14(5), 739–759. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(90)90004-W

- Laberge, S., & Sankoff, G. (1979). Anything you can do. In T. Givón (Ed.), Discourse and syntax (pp. 419–440). New York Academic Press.

- Ladewig, S. H. (2014). Recurrent Gestures. In C. Müller, A. Cienki, E. Fricke, S. H. Ladewig, D. McNeill, & J. Bressem (Eds.), Body–language–communication: An international handbook on multi-modality in human interaction [Handbooks of Linguistics and Communication Science 38.2] (pp. 1558–1574). Mouton de Gruyter.

- Li, X. (2016). Some discourse-interactional uses of yinwei ‘because’ and its multimodal production in Mandarin conversation. Language Sciences, 58, 51–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2016.04.005

- Lindström, J., Laury, R., Peräkylä, A., & Sorjonen, M. L. (Eds.). (2021). Intersubjectivity in action: Studies in language and social interaction. John Benjamins.

- Lindström, J., & Wide, C. (2005). Tracing the origins of a set of discourse particles: Swedish particles of the type you know. Journal of Historical Pragmatics, 6(2), 211–236. https://doi.org/10.1075/jhp.6.2.04lin

- Linell, P. (2009). Rethinking language, mind, and world dialogically: Interactional and contextual theories of human sense-making. Information Age Publishing.

- Livnat, Z., & Yatziv, I. (2003). Causality and justification: The causal marker ki in Spoken Hebrew. Revue de Semantique et Pragmatique, 13, 99–119.

- Lopez-Ozieblo, R. (2020). Proposing a revised functional classification of pragmatic gestures. Lingua, 247, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2020.102870

- Marrese, O. H., Raymond, C. W., Fox, B. A., Ford, C. E., & Pielke, M. (2021). The grammar of obviousness: The Palm-Up gesture in argument sequences. Frontiers in Communication, 6, 663067. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.663067

- Maschler, Y. (1994). Metalanguaging and discourse markers in bilingual conversation. Language in Society, 23(3), 325–366. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404500018017

- Maschler, Y. (2002). The role of discourse markers in the construction of multivocality in Israeli Hebrew talk-in-interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 35(1), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327973RLSI35-1_1

- Maschler, Y. (2012). Emergent projecting constructions: The case of Hebrew yada (‘know’). Studies in Language, 36(4), 785–847. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.36.4.03mas

- Maschler, Y. (2018). The on-line emergence of Hebrew insubordinate she- (‘that/which/who’) clauses: A usage-based perspective on so-called ‘subordination.’ Studies in Language, 42(3), 669–707. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.17065.mas

- Maschler, Y., & Estlein, R. (2008). Stance-taking in Hebrew causal conversation via be'emet (really, actually, indeed, lit. “in truth”). Discourse Studies, 10(3), 283–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445608090222

- Maschler, Y., & Miller Shapiro, C. (2016). The role of prosody in the grammaticization of Hebrew naxon (‘right/true’): Synchronic and diachronic aspects. Journal of Pragmatics, 92, 43–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2015.11.007

- Maschler, Y., Pekarek Doehler, S., Lindström, J., & Keevallik, L. (Eds.). (2020). Emergent Syntax for conversation: Clausal patterns and the organization of action. John Benjamins.

- Maschler, Y., Polak-Yitzhaki, H., Aghion, G., Fofliger, O., Wildner, N., Ben Moshe, Y. M., Lagil, R., Saar, S., & Inbar, A. (2023). The Haifa Multimodal Corpus of Spoken Hebrew.

- Maschler, Y. (2017). Blurring the boundaries between discourse marker, pragmatic marker, and modal particle: The emergence of Hebrew loydea/loydat (“I dunno MASC/FEM”) from interaction. In A. Sansò & C. Fedriani (Eds.), Pragmatic markers, discourse markers and modal particles: New perspectives (pp. 37–69). John Benjamins.

- McNeill, D. (1992). Hand and mind: What gestures reveal about thought. University of Chicago Press.

- McNeill, D. (2018). Recurrent gestures: How the mental reflects the social. Gesture, 17(2), 229–244. https://doi.org/10.1075/gest.18012.mcn

- Miller Shapiro, C. (2014). ‘tir’i, hara’ayon po hu shone’: Hapo’al ra’a vesamaney hasi’ax hamexilim ‘oto basi’ax ha’ivri hayom-yomi hadavur [Look, the idea here is different’: The verb ra’a ‘see’ and the discourse markers containing it in everyday spoken Hebrew discourse]. Lešonenu [Our Language], 76(1–2), 165–200.

- Mondada, L. (2006). Challenges of multimodality: Language and body in social interaction. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 20(3), 336–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.1_12177

- Mondada, L. (2014). The local constitution of multimodal resources for social interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 65, 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2014.04.004

- Mondada, L. (2018). Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: Challenges for transcribing multimodality. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2018.1413878

- Mondada, L. (2019). Conventions for multimodal transcription. Retrieved November 14, 2022, from https://www.lorenzamondada.net/multimodal-transcription

- Mondada, L. (2015). Multimodal completions. In S. Günthner & A. Deppermann (Eds.), Temporality in interaction (pp. 267–308). John Benjamins.

- Mor, U. (2006). Two presentative particles in Mishnaic Hebrew according to Ms. Ebr. 32.2 to Sifré on Numbers. Lešonenu [Our Language], 68, 209–242.

- Mori, J. (1994). Functions of the connective datte in Japanese conversation. Japanese/Korean Linguistics, 4, 147–163. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.16.1.04may

- Mori, J. (1999). Well I may be exaggerating but …: Self-qualifying clauses in negotiating of opinions among Japanese speakers. Human Studies, 22(2–4), 447–473. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005440010221

- Müller, C. (2017). How recurrent gestures mean: Conventionalized contexts-of-uses and embodied motivation. Gesture, 16(2), 277–304. https://doi.org/10.1075/gest.16.2.05mul

- Müller, C. (2004). Forms and uses of the palm up open hand: A case of a gesture family? In C. Müller & R. Posner (Eds.), The semantics and pragmatics of everyday gestures (pp. 233–256). Weidler.

- Pekarek Doehler, S., Keevallik, L., & Li, X. (2021). The grammar-body interface in social interaction [Special issue]. Frontiers in Psychology and Frontiers in Communication.

- Podlesskaya, V. I. (1993). Causatives and causality: Towards a semantic typology of causal relations. In B. Comrie & M. Polinsky (Eds.), Causatives and transitivity (pp. 165–176). John Benjamins.

- Polak-Yitzhaki, H. (2020, February 25). hitkab'uta shel hatavnit 'at/a ro'e/a basiax ha'ivri hadavur: Mabat multimodali [The sedimentation of the 'at/a ro'e/a ‘you see’ construction in spoken Hebrew discourse: A multimodal perspective][Paper presentation]. 36th meeting of the Israeli Linguistics Society, Zefat, Israel.

- Polak-Yitzhaki, H., Amon, M., Maschler, Y., & Keevallik, L. (2021, June 27–July 2). Verbs of seeing as evidentials: Hebrew 'ata ro'e and Estonian näed (‘you see’) [Paper presentation]. 17th International Pragmatics Association conference (IPrA), Winterthur, Switzerland.

- Pomerantz, A. M. (1984). Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: Some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shapes. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversational analysis (pp. 57–101). Cambridge University Press.

- Raymond, C. W. (2019). Intersubjectivity, normativity, and grammar. Social Psychology Quarterly, 82(2), 182–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272519850781

- Robinson, J. G. (2016). Accountability in social interaction. In J. G. Robinson (Ed.), Accountability in social interaction (pp. 1–41). Oxford University Press.

- Sacks, H. (1987). On the preference for agreement and contiguity in sequences in conversation. In G. Button & J. R. E. Lee (Eds.), Talk and social organization (pp. 54–69). Multilingual Matters.

- Sacks, H., & Schegloff, E. A. (1979). Two preferences in the organization of reference to persons and their interaction. In G. Psathas (Ed.), Everyday language: Studies in ethnomethodology (pp. 15–21). Irvington Publishers.

- San Roque, L., Kendrick, K. H., Norcliffe, E., & Majid, A. (2018). Universal meaning extensions of perception verbs are grounded in interaction. Cognitive Linguistics, 29(3), 371–406. https://doi.org/10.1515/cog-2017-0034

- Schegloff, E. A. (1991). Reflections on talk and social structure. In D. Boden & D. H. Zimmermann (Eds.), Talk and social structure (pp. 44–70). University of California Press.

- Schegloff, E. A. (2007). Sequence organization in interaction: A primer in conversation analysis. Cambridge University Press.

- Schegloff, E. A., & Sacks, H. (1973). Opening up closings. Semiotica, 8(4), 289–327. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.1973.8.4.289

- Schiffrin, D. (1987). Discourse markers. Cambridge University Press.

- Shor, L., & Marmorstein, M. (2022). The embodied modification of formulations: The Quoting Gesture (QG) in Israeli-Hebrew discourse. Journal of Pragmatics, 192, 22–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2022.01.019

- Sikveland, R. O., & Ogden, R. (2012). Holding gestures across turns: Moments to generate shared understanding. Gesture, 12(2), 166–199. https://doi.org/10.1075/gest.12.2.03sik

- Spooren, W., Sanders, T., Huiskes, M., & Degand, L. (2010). Subjectivity and causality: A corpus study of spoken language. In S. Rice & J. Newman (Eds.), Empirical and experimental methods in cognitive/functional research (pp. 241–255). CSLI Publications.

- Stivers, T. (2008). Stance, alignment, and affiliation during storytelling: When nodding is a token of affiliation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 41(1), 31–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351810701691123

- Stivers, T., & Hayashi, M. (2010). Transformative answers: One way to resist a question’s constraints. Language in Society, 39(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404509990637

- Stivers, T., Mondada, L., & Steensig, J. (Eds.). (2011). The morality of knowledge in conversation [Special issue]. Studies in Interactional Sociolinguistics, 29.

- Streeck, J. (2009). Gesturecraft: The manu-facture of meaning. John Benjamins.

- Sweetser, E. (1990). From etymology to pragmatics. Cambridge University Press.

- Taine-Cheikh, C. (2013). Grammaticalized uses of the verb raʔā in Arabic: A Maghrebian specificity? In M. Lafkioui (Ed.), African Arabic: Approaches to dialectology (pp. 121–159). De Gruyter.

- Thompson, S. A., Fox, B. A., & Couper-Kuhlen, E. (2015). Grammar in everyday talk: Building responsive actions. Cambridge University Press.

- Tobin, Y., & Stern-Perez, A. (2009). Linguistic sign systems indicating proximity and remoteness in the ‘trouble talk’ of Israeli bus drivers who experienced terror attacks. Israeli Studies in Language and Society, 2(2), 144–168.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical investigations ( G. E. M. Anscombe, Trans.). Macmillan.

Appendix

Transcription Conventions

(Following Chafe, Citation1994; Du Bois et al., Citation1992; Du Bois, Citation2012; and adapted for Hebrew by Maschler, Citation2017).

. – perceptible pause of less than 0.1 second

… – average pause (0.1 ≤ x < 1.0 seconds)

… . – pause (1.0 ≤ x < 1.5 seconds)

… . – pause (1.5 ≤ x < 2.0 seconds)

(3.56) – measured pause of 3.56 seconds

– comma at end of line – mid-level, mid-rise, mid-fall intonation, regularly understood in Hebrew as “more to come”

. – period at end of line – low fall intonation, regularly understood in Hebrew as final

? – question mark at end of line – high rising intonation, regularly understood in Hebrew as

final and seeking response from interlocutor

?, – question mark followed by comma – rising intonation, regularly understood in Hebrew as projecting “more to come” while seeking response from interlocutor

! – exclamation mark at end of line – final exclamatory intonation

ø – lack of punctuation at end of line – a fragmentary intonation unit, one which never reached completion.

– two hyphens – elongation of preceding sound

underlined syllable – primary stress of intonation unit

boldfaced syllable – secondary stress of intonation unit

boldfaced words – grammatical components of the target structure (ki-clauses)

@ – a burst of laughter (each additional @ symbol denotes an additional burst)

inverted bracket + alignment such that the right of the top line

is placed over the left of the

bottom line indicates latching, no interturn pause

Musical notation as necessary: e.g., acc – accelerando (progressively faster).

(in regular brackets) – nonverbal action constituting a turn

{in curly brackets} – transcriber’s comments

' – uninverted quotation mark indicates the glottal stop phoneme

’ – inverted quotation mark in a transliterated word indicates an elided form (e.g., ‘an’lo instead of ‘ani lo (lit. ‘I not,’ ‘I don’t’/‘I’m not’))

- one hyphen – bound-morpheme boundary

/words within slashes/ indicate uncertain transcription

/????/ – undecipherable utterance

Transcription of embodied conduct

(following Mondada, Citation2019)

# # Descriptions of embodied conduct are delimited in between symbols.

± ± Two identical symbols (one symbol per participant and per type of conduct) are synchronized with corresponding stretches of talk.

– -> Described embodied conduct continues across subsequent lines

– -># until the same symbol is reached.

… . … . Action’s preparation

– – – Action’s apex is reached and maintained.

# – –>l.12 Described embodied conduct continues until line 12 of transcript.

# – –≫ Described embodied conduct continues beyond end of excerpt.

≪ – – Described embodied conduct begins before the excerpt’s beginning.

* Exact position in the utterance in which a video caption was made.

Glossing conventions – according to the Leipzig glossing conventions.

In addition:

non-lex non-lexical vocalization