Abstract

The concept of customer centricity is frequently debated by sales and marketing researchers and practitioners. However, to date no validated scale exists that measures to what extent customers perceive companies as customer centric. Against this backdrop, drawing on prior literature, qualitative interviews, and a customer survey (N = 246), the authors develop and validate a measurement scale for perceived customer centricity. In addition, using matched survey and financial data from industrial customers (N = 1,089), the authors examine antecedents and consequences of perceived customer centricity. Results show that customers perceive firms as customer centric if the supplier is customer oriented on both the overall firm level and the salesperson level. Furthermore, perceived customer centricity is strongly linked to customers’ loyalty intentions and objective sales revenue, particularly if customers perceive a firm to exhibit high prices. Thus, this article equips managers with a validated and easy-to-use measurement that allows monitoring a firm’s progress toward customer centricity.

To achieve a competitive advantage, companies increasingly strive to be perceived by their customers as customer centric (e.g., Selden and MacMillan Citation2006; Shah et al. Citation2006; Lee et al. Citation2015). For example, Amazon states in its marketing communication that it aims to be Earth’s most customer-centric firm (Amazon Citation2019). Similarly, Hewlett Packard and Fresenius emphasize that they put their customers first in everything they do (Hewlett Packard Citation2019; Fresenius Citation2019). Furthermore, the number of Google searches for the term “customer centricity” more than doubled from 2008 to 2018 (Google Trends Citation2019), and several prestigious business schools included courses on customer centricity in their executive education programs (e.g., Kellogg Citation2019; Stanford Citation2019).

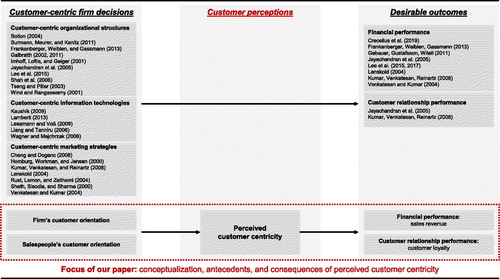

Managers’ growing interest in being perceived as customer centric is reflected by academic research. Customer centricity is defined as putting customers’ interests at the center of a firm’s actions (e.g., Burmann, Meurer, and Kanitz Citation2011; Gummesson Citation2008a, Citationb; Shah et al. Citation2006; Sheth, Sisodia, and Sharma Citation2000; see also ) and can be achieved by implementing customer-centric organizational structures (e.g., Galbraith Citation2005; Shah et al. Citation2006; Lamberti Citation2013), customer-centric information technologies (e.g., Wagner and Majchrzak Citation2006; Waisberg and Kaushik Citation2009), and customer-centric marketing strategies (e.g., Lenskold Citation2004; Gurău, Ranchhod, and Hackney Citation2003; Sheth, Sisodia, and Sharma Citation2000). Implementing such changes to instill customer centricity can improve firm performance (e.g., Sheth, Sisodia, and Sharma Citation2000; Fader Citation2012; Lee et al. Citation2015; Crecelius et al. Citation2019; see ).

Table 1. Definitions of customer centricity.

Visible in this short depiction of existing literature, extant studies have mostly adopted a firm-centered view on customer centricity, examining effective management levers to enhance customer centricity. Interestingly, however, extant research has not conceptualized and empirically explored customers’ perceptions of customer centricity. More specifically, to our best knowledge, no study has developed a validated scale that measures customers’ perceptions of customer centricity, which we define as the degree to which customers perceive a firm to put customers’ interests at the center of all of its actions. We consider this omission as striking for two reasons.

First, without a validated scale, sales and marketing managers cannot monitor how their intentions and measures to develop customer centricity in fact translate into customer perceptions. Importantly, the difference between a firm’s intended customer centricity and the customer centricity perceived by the customer is essential: While firms may make honest efforts to act in a customer-centric manner (e.g., by adjusting organizational structures, information technology, or marketing strategies), these efforts may not necessarily pay off, leading to stagnating customer perceptions of customer centricity. Thus, to track their progress in becoming customer centric, managers require a measurement they can readily employ in customer surveys. Given the nature of customer centricity, we consider it paradoxical if companies aim to improve customer centricity yet neglect to consider customers’ feedback on their progress.

Second, given the lack of a validated measurement scale, academics have been unable to analyze (a) the consequences and (b) the antecedents of perceived customer centricity. As to the first, improving our understanding of consequences of perceived customer centricity is necessary to evaluate whether setting customers’ perceptions of customer centricity as a firm objective is sensible (see the case of Amazon Citation2019). This notion follows Shah and colleagues (Citation2006, 122), who suggested that “a major research stream relevant to customer centricity is warranted in the context of exploring its financial implications.” In addition, improving our understanding of antecedents of perceived centricity helps companies decide which measures to implement if they intend to be perceived as customer centric. We consider it particularly interesting to explore how salespeople, as key intermediaries between firms and customers, forge customers’ perceptions of a firm’s overall customer centricity. This question seems highly relevant considering that firms put substantive effort into orienting their sales departments to their customers (e.g., Lee et al. Citation2015) and sales managers regard articulating a solution that centers on customers’ needs as the most significant sales practice (CSO Insights Citation2017).

In summary, developing a validated scale of perceived customer centricity has merits both for academic research and for sales and marketing practice. Against this backdrop, we set out to develop and empirically validate a scale of customer centricity as perceived by customers. Building on established scale development and validation procedures (e.g., Churchill Citation1979; Gerbing and Anderson Citation1988; DeVellis Citation2003), our final measurement scale comprises six items that exhibit good convergent and discriminant validity. We then conceptualize potential antecedents and consequences of perceived customer centricity and test our hypotheses using survey data matched with firm records from 1,089 industrial customers. Results show that customers’ perceptions of a firm as customer centric are decisively driven by the firm’s customer orientation both on the firm level and on the level of individual salespeople. Furthermore, perceived customer centricity increases customers’ loyalty intentions and purchase volume, particularly if customers perceive the firm to exhibit high prices.

Our study makes three important contributions to academia. First, our study is the first to conceptualize customers’ perceptions of a firm’s customer centricity and provides a validated measurement scale. Future studies may employ this scale to deepen our understanding of customer centricity. Second, our study provides insights into consequences of customer centricity as perceived by customers. Seeing its effects on customer loyalty and sales revenue, our results imply that perceived customer centricity may in fact be an important addition to models exploring the effectiveness of customer centricity initiatives (e.g., Lee et al. Citation2015; Burmann, Meurer, and Kanitz Citation2011). Furthermore, by showing that perceived customer centricity is not equally beneficial for all customers, we contribute to literature that examines contingent effects of customer centricity (Frankenberger, Weiblen, and Gassmann Citation2013). Third, our study contributes to literature on how to implement customer centricity. While prior literature has particularly examined strategic decisions affecting organizational structures, information technology, and marketing strategies (e.g., Galbraith Citation2005; Waisberg and Kaushik Citation2009; Lenskold Citation2004), our study shows that customers’ perceptions of customer centricity crucially depend on specific behaviors of a firm and its salespeople.

For sales and marketing managers, our study provides three key recommendations. First, as perceived customer centricity increases sales revenue, managers should strive to establish that their customers perceive the firm as customer centric. This is especially true for firms with a high price positioning, for which perceived customer centricity most strongly increases sales revenue and customer loyalty. Second, to be perceived as customer centric, managers need to foster customer orientation both on the level of the firm and on the level of individual salespeople. Put differently, rather than trying to foster customer centricity through marketing communications, managers need to remind themselves that actions speak louder than words. Third, managers may use the measurement scale developed in our study to monitor the degree to which their firm is perceived as customer centric. The scale requires little effort to complete, yet has good psychometric properties, including predictive validity.

Conceptualizing perceived customer centricity

To anchor our conceptualization of perceived customer centricity in prior research, we provide a literature review on established definitions of customer centricity (see ). While these definitions differ across studies, we identified three recurring themes that seem to be well-accepted characteristics of customer centricity: (1) the firm unit of analysis, (2) the focus on customers’ interests, and (3) the active prioritization of customers. In the following, we elaborate on these themes and subsequently use them to develop our own definition of perceived customer centricity.

First, most articles that we reviewed analyzed customer centricity as a phenomenon on the level of the firm (e.g., Sheth, Sisodia, and Sharma Citation2000; Shah et al. Citation2006; Crecelius et al. Citation2019). This means that extant research typically conceptualized firms (rather than specific functions or individuals within these firms) as the entities that exhibit customer centricity. Few studies conceptualized customer centricity on a functional level. For example, Cheng and Dogan (Citation2008) focused on customer-centric marketing, Kumar, Venkatesan, and Reinartz (Citation2008) investigated customer-focused sales campaigns, and Liang and Tanniru (Citation2006) examined customer-centric information systems.

Second, most definitions emphasized that high customer centricity is characterized by a strong focus on addressing customers’ interests (e.g., Bolton Citation2004; Shah et al. Citation2006; Kumar, Venkatesan, and Reinartz Citation2008). Seeing that these interests are typically not universal for all customers, some works considered customer centricity to entail a customer-segment-specific consideration of customers’ interests (Burmann, Meurer, and Kanitz Citation2011; Frankenberger, Weiblen, and Gassmann Citation2013; Lee et al. Citation2015; Crecelius et al. Citation2019).

Third, some studies conceived customer centricity as entailing the active prioritization of customers and their interests over internal firm concerns (Jayachandran et al. Citation2005; Shah et al. Citation2006; Burmann, Meurer, and Kanitz Citation2011). For example, Shah et al. (Citation2006, 115) stated that “all decisions start with the customer,” and Jayachandran et al. (Citation2005, 179) understood a customer-centric management system as a management system where “actions are driven by customer needs and not by the internal concerns of functional areas.” Other studies however did not go this far and merely conceptualized customer centricity as adaptations of firm structures and processes to customer interests (e.g., Bolton Citation2004; Lee et al. Citation2015; Crecelius et al. Citation2019).

In summary, while extant studies differ in the nuances of definitions of customer centricity, three recurring themes across these definitions are the firm unit of analysis, focus on customers’ interests, and a prioritization of customers. Interestingly, however, none of these studies conceptualized customer centricity as a customer perception. To incorporate this notion and deduce a conceptual definition of perceived customer centricity as a first important step in this article, we merge the three themes of previous definitions with our notion of customer centricity as a customer perception (see ). Essentially, we define perceived customer centricity as the degree to which a customer perceives a firm to put customers’ interests at the center of all of its actions.

Two questions arise when considering the conceptualization of customer centricity. First, how is customer centricity different from customer orientation? Both concepts are similar because they can be conceptualized on the level of firms and on the level of subunits (e.g., salespeople, functions) and entail a strong focus on customer needs. A major difference between the concepts is the degree to which they entail a prioritization of customers. Whereas customer orientation is characterized as a tendency to meet customer needs (Brown et al. Citation2002), customer centricity may be viewed as wider reaching by giving customer interests priority and putting them at the center of all of a firm’s actions (Jayachandran et al. Citation2005; Shah et al. Citation2006; Burmann, Meurer, and Kanitz Citation2011).

Second, is perceived customer centricity a multidimensional or a unidimensional construct? For example, following Lamberti (Citation2013), customer centricity may comprise three elements: customer intelligence generation, co-creation, and experience marketing; Shah et al. (Citation2006) propose nine dimensions that differentiate a customer-centric approach, such as product positioning, organizational structure, and performance metrics. However, we deliberately decided for a unidimensional definition and measure for three reasons. First, our study focuses on customer perceptions rather than structural elements of a firm’s customer centricity. While customers may consolidate perceptions of multiple aspects to an overall perception of a firm’s customer centricity, we hold that such aspects would constitute antecedents rather than dimensions of perceived customer centricity. Second, we strove to develop a measure that is easy to apply for both academics and practitioners. However, measuring various dimensions limits the applicability of the scale due to an increasing number of measurement items. Furthermore, certain dimensions may be more or less relevant depending on a firm’s industry and target market (e.g., co-creation; Lamberti Citation2013), rendering benchmarking more difficult. Third, previous research questioned the validity of higher-order formative latent variables (e.g., Cadogan and Lee Citation2013; Lee and Cadogan Citation2013). Thus, we decided to refrain from defining and operationalizing perceived customer centricity as a multidimensional construct.

Study 1: Developing a customer centricity scale

In our first study, we developed a scale to measure customer centricity as perceived by customers in accordance with our definition. When developing the new scale of perceived customer centricity, we aimed for parsimony, readability, and simplicity of the measurement items (e.g., Churchill Citation1979; Gerbing and Anderson Citation1988; DeVellis Citation2003). Following prior research on scale development, we applied well-established scale development procedures (e.g., Churchill Citation1979; Gerbing and Anderson Citation1988; DeVellis Citation2003).

In the following three sections, we describe the measurement development process we adopted to generate a set of items for a measurement scale of perceived customer centricity: (1) generation of an initial measurement pool, (2) refinement and reduction of the initial item pool, and (3) quantitative measure validation of the remaining items (e.g., Churchill Citation1979; Gerbing and Anderson Citation1988; DeVellis Citation2003).

Generation of the initial item pool for measuring perceived customer centricity

In a first step, based on the procedure proposed by Churchill (Citation1979), we generated an initial item pool for the measure of perceived customer centricity. We deduced items for our initial item pool from academic literature (e.g., Lee et al. Citation2015; Gummesson Citation2008a; Shah et al. Citation2006; Bolton Citation2004), managerial literature (e.g., Selden and MacMillan Citation2006; Rust, Zeithaml, and Lemon Citation2004; Galbraith Citation2005; Lenskold Citation2004), and firms’ vision statements (e.g., Amazon Citation2019; Hewlett Packard Citation2019; Fresenius Citation2019). Furthermore, we initiated discussions with four marketing academics of several institutions and asked them to propose items to measure customer perceptions of a firm’s customer centricity. After consolidating items from the three sources, our initial pool comprised 12 items. To reduce items during scale refinement, we followed the approach of DeVellis (Citation2003). Specifically, “by using multiple and seemingly redundant items, the content that is common to the items will summate across items while their irrelevant idiosyncrasies will cancel out” and “you want considerable more than you plan to include in the final scale” (DeVellis Citation2003, 65–66).

Refinement and reduction of the initial item pool (Study 1.1 to Study 1.3)

In a second step, we pretested the initial pool of 12 scale items with 10 customers for comprehension, logic, and relevance (Study 1.1). This procedure is well established in scale development and in line with the procedure of Churchill (Citation1979). We provided our definition of perceived customer centricity as well as the initial pool of items to our group of customers and asked them to rate each item concerning (1) its ability to assess the item, that is, whether they had the necessary insights to assess the item, (2) the comprehensibility and clarity of the item compared to the other items, and (3) the general ability of the item to measure a customer’s perceptions of a firm’s customer centricity. Drawing on the feedback of the group of customers, we made several adaptions to the initial items regarding wording and eliminated three of the initial 12 items.

In a third step, we presented the remaining items to a panel of four academic experts of marketing and sales faculties (Study 1.2) to examine face validity based on the same questions we asked the group of customers. Besides further adaptions regarding the wording of the items, the panel suggested eliminating one further item, resulting in a list of eight scale items.

In a fourth step, we administered the remaining scale items to a panel of four managers, from the consulting, automotive, banking, and online platform operator industries, for further screening of content and face validity (Study 1.3). We asked the managers to rate each item as clearly representative, somewhat representative, or not representative for a scale that measures the degree to which a customer perceives a firm to put customers’ interests at the center of all of its actions. We followed Bearden, Netemeyer, and Teel (Citation1989), Tian and McKenzie (Citation2001), and Zaichkowsky (Citation1985) by selecting the items that remained in the scale. Specifically, to remain in the scale, an item had to be rated as clearly representative by all managers, or it had to be rated as clearly representative by at least three-quarters of the managers and as somewhat representative by the remaining managers. Using this well-established scale development process step, we eliminated two additional items. The remaining six items were considered for further refinement as described in the next process step. The remaining six items represent 50% of the initial large pool of items, which is still valued as suitable in scale development research (e.g., Babin, Darden, and Griffin Citation1994; Toncar et al. Citation2006; Yi and Gong Citation2013). provides sample characteristics of our three different panels.

Table 2. Study 1: Sample characteristics.

Study 2: Verifying the scale’s construct, convergent, and discriminant validities

Data collection and sample

We conducted Study 2 to test the construct validity, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the perceived customer centricity scale developed in Study 1. Furthermore, we sought to verify that the scale and the concept of perceived customer centricity were understood by survey participants and customers. For this purpose, we administered a survey to 246 customers (mean age of 33 years, 45.5% female; detailed demographics in ) via a crowdsourcing Internet marketplace. Whereas the data for Study 1.1 to Study 1.3 were collected in Europe, data for Study 2 were collected from consumers in the United States. The participants were asked to think about the bank with which they conduct their main share of banking business. Then we asked participants to evaluate the bank using our newly developed items of perceived customer centricity as well as established and widely used measurements of a firm’s customer orientation (Im and Workman Citation2004; Narver and Slater Citation1990) and salespeople’s customer orientation (Saxe and Weitz Citation1982; Dwyer, Hill, and Martin Citation2000; Homburg, Müller, and Klarmann Citation2011a,b). All questions in Study 2 used 7-point Likert scales (a list of all items is provided in Appendix 1). In what follows, we describe the approach we used to analyze the data.

Table 3. Studies 2 and 3: Sample characteristics.

Tests for construct, convergent, and discriminant validities

To assess discriminant validity, we tested our measure of perceived customer centricity against well-established scales of a firm’s customer orientation and salespeople’s customer orientation. Because the concepts of customer orientation and perceived customer centricity are closely related, yet distinct (Lamberti Citation2013; Sheth, Sisodia, and Sharma Citation2000), we aimed to test our scale’s discriminant validity.

First, results of an exploratory factor analysis with Promax rotation including the six items of perceived customer centricity, four items of a firm’s customer orientation, and four items of salespeople’s customer orientation revealed that three factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were extracted (e.g., Kaiser Citation1960; see ). All items loaded on their corresponding factors, and no cross-loadings were greater than .29. Whereas every item of perceived customer centricity loaded on its corresponding factor with no smaller factor loadings than .69 and no cross-loadings greater than .15, the well-established scales of a firm’s customer orientation and salespeople’s customer orientation indicated factor loadings that were smaller than .70. Web Appendix W1 provides further insights that reveal that these results do not affect the construct validity, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of perceived customer centricity. Furthermore, Web Appendix W2 establishes the discriminant validity of perceived customer centricity against alternative operationalizations of customer orientation (Brown et al. Citation2002).

Table 4. Studies 2 and 3: Results of exploratory factor analyses.

Second, we tested for internal consistency, composite reliability, and average variance extracted for the measurement scales of perceived customer centricity, a firm’s customer orientation, and salespeople’s customer orientation. Internal consistency was given seeing that no Cronbach’s alpha values were lower than .87. Furthermore, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis indicating a good fit of the model (e.g., RMSEA = .08; CFI = .94; TLI = .93; SRMR = .04). No composite reliabilities were lower than .87 and no values for average variance extracted were lower than .62, thus meeting or exceeding the recommended thresholds (Bagozzi and Yi Citation1988). We additionally assessed the discriminant validity of the construct measures by using Fornell and Larcker’s (Citation1981) criterion. The squared estimated correlation of every pair of factors was smaller than each factor’s average variance extracted. In summary, these analyses confirm our scale’s construct validity, convergent validity, and discriminant validity.

Tests for face validity

In addition, we tested whether participants of Study 2 understood the meaning of perceived customer centricity and each of its six items. Therefore, we provided participants our definition of perceived customer centricity and asked them whether they understood the concept, using both a binary and a Likert-scaled question; 97.2% of participants indicated that they understood the meaning of the concept of perceived customer centricity, and the mean on a 7-point Likert scale was 5.85 (from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Furthermore, we asked participants how easy it was for them to answer each of the items of perceived customer centricity. The lowest mean on all items was 5.15 (7-point Likert scale, from 1 = very difficult to answer to 7 = very easy to answer). These results indicate that participants understood our measurement items and the concept of perceived customer centricity.

Antecedents and consequences of perceived customer centricity

Our newly developed and validated measurement scale enables us to examine (1) how companies can engender perceptions of customer centricity and (2) what consequences perceptions of customer centricity have for firms. To this end, we initially review prior literature on antecedents and consequences of customer centricity and subsequently derive hypotheses on the construct of perceived customer centricity.

Literature review on customer centricity

Antecedents of customer centricity

To our best knowledge, no prior study has examined customer perceptions of customer centricity. Instead, previous research predominantly focused on specific ways of implementing customer centricity, such as adjusting organizational structures, information technologies, and marketing strategies. In the following, we elaborate on key findings of prior studies.

First, several studies examined how firms can adapt their organizational structure to customers and their needs to achieve higher customer centricity. Organizational structures reflect the extent to which a firm’s organizational design aligns with its customers or customer groups (e.g., Imhoff, Loftis, and Geiger Citation2001; Wind and Rangaswamy Citation2001; Galbraith Citation2002, Citation2011; Shah et al. Citation2006; Lee et al. Citation2015). Academic marketing literature on customer-centric organization structures claims that aligning organizational structures to customers instead of having functional or product-oriented structures increases customer centricity and firm success (e.g., Burmann, Meurer, and Kanitz Citation2011; Shah et al. Citation2006). However, Lee et al. (Citation2015) indicated that aligning organizational structures to customers to become more customer centric comprises an inherent cost–benefit tradeoff. Specifically, for firms being organized in large divisions or for firms competing in different markets, customer-centric organization structures do pay off financially. By contrast, for firms that are already aligned with their customers, with small divisions serving less-diverse markets, or for firms competing in only few markets, the additional infrastructure costs and communication complexity outweigh the benefits of being organized customer centric (Lee et al. Citation2015).

Second, prior literature focused on how firms can use information technologies that consider customers and their needs to implement customer centricity (e.g., Lessmann and Voß Citation2009; Wagner and Majchrzak Citation2006; Kaushik Citation2009; Liang and Tanniru Citation2006). Lessmann and Voß (Citation2009) show that analyzing a firm’s data streams helps firms gain insights into customer behavior, needs, and preferences and thereby can improve decision making in customer-centric planning tasks. Furthermore, Wagner and Majchrzak (Citation2006) illustrated that firms can use “customer wikis” to become more customer centric. Customer wikis allow customers to not only access but also change a firm’s online presence and enable collaborative content and joint solution development.

Last, prior literature offers important insights on how firms can improve their performance through customer-centric marketing strategies. Sheth, Sisodia, and Sharma (Citation2000, 65) implied that customer-centric marketing will increase efficiency in marketing processes not by influencing people in terms of what to buy, when to buy, and how much to buy, but by being more concerned to better respond to customer demands (Sharma and Sheth Citation2004). Specifically, firms may improve profits and return on marketing communications through the appropriate identification of customers for customized communications, collaborative development of campaigns, and the matching of the channel of communication with customers’ preferences (e.g., Sheth, Sisodia, and Sharma Citation2000; Venkatesan and Kumar Citation2004; Lenskold Citation2004; Cheng and Dogan Citation2008). Customer-centric sales campaigns not only may increase firm profits and return on investment but may additionally have a positive impact on the relationship quality between the customer and the firm (Kumar, Venkatesan, and Reinartz Citation2008). Nonetheless, Venkatesan and Kumar (Citation2004) indicated that financial benefits of customer-centric marketing strategies may not be realized immediately because firms need to incur costs to move their organization toward customer centricity.

Consequences of customer centricity

Although customer centricity has been regarded as important for firms for several decades (e.g., Sheth, Sisodia, and Sharma Citation2000; Shah et al. Citation2006; Gummesson Citation2008a), research investigating consequences of customer centricity empirically is relatively scarce. Existing marketing literature mainly concentrates on how objective firm characteristics classified as customer centric affect firm performance (e.g., Lee et al. Citation2015; Sheth, Sisodia, and Sharma Citation2000; Fader Citation2012; Crecelius et al. Citation2019) and on how customer-centric marketing strategies perform (e.g., Homburg, Workman, and Jensen Citation2000; Kumar, Venkatesan, and Reinartz Citation2008).

Research on consequences of customer-centric firm characteristics indicates that structuring divisions around customer groups improves financial performance by increasing customer satisfaction but harms financial performance through coordinating costs (Lee et al. Citation2015). Lee et al. (Citation2017) showed that, when considering investments in personal selling and advertising, the payoff of such investments improves if a firm exhibits a customer-aligned structure. Furthermore, customer-centric management systems have been shown to enhance relational information processes with customers and, thus, customer relationship performance (Jayachandran et al. Citation2005). In addition, Crecelius et al. (Citation2019) found that suppliers that exhibit customer centricity by proactively assessing the structure of their customers can enhance revenue and mitigate costs.

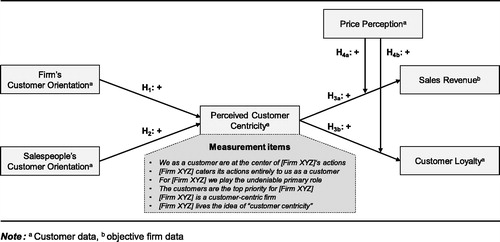

Hypotheses on perceived customer centricity

Aiming to extend prior literature, we propose that a firm’s customer orientation and that of its salespeople foster customers’ perceptions of customer centricity, which in turn increase customers’ sales revenue and loyalty. Customer orientation entails behaviors related to understanding and meeting customer needs and should therefore reflect an important cue for customers to perceive firms as customer centric. Furthermore, we suggest that the consequences of perceived customer centricity on sales revenue and customer loyalty depend on customers’ perceptions of a firm’s prices. Specifically, we suggest that customers who perceive a company’s prices as high might place a higher importance on customer centricity and are thus more likely to purchase and to be loyal when they perceive the firm to be highly customer centric. provides our conceptual framework and displays all proposed hypotheses. We proceed by developing these hypotheses and subsequently empirically test them in Study 3.

We draw on diagnosticity theory (Feldman and Lynch Citation1988) to derive the effects of a firm’s customer orientation and salespeople’s customer orientation on perceived customer centricity. According to diagnosticity theory, to make inferences, individuals rely on the most useful (i.e., “diagnostic”) cues available and refrain from using other, less useful, cues (e.g., Feldman and Lynch Citation1988; Skowronski and Carlston Citation1987). For example, customers may base their evaluation of a seller’s product quality on their own experiences with the seller’s products rather than on advertising claims (Feldman and Lynch Citation1988). Prior research has applied diagnosticity theory to customer decision making (e.g., Alavi, Bornemann, and Wieseke Citation2015; Dick, Chakravarti, and Biehal Citation1990) and customers’ evaluations of corporate messages (e.g., Biehal and Sheinin Citation2007; Habel et al. Citation2016).

In the following, we use diagnosticity theory to propose antecedents of perceived customer centricity. Our argument builds on the notion that it is difficult, if not impossible, for customers to evaluate whether a firm genuinely places customers’ interests in the center all of its actions because most of these measures are not directly visible and accessible to customers. Therefore, customers need to base their evaluation of customer centricity on diagnostic cues that they are in fact able to access (Feldman and Lynch Citation1988). A firm’s customer orientation may serve as a diagnostic cue in this respect. Specifically, a firm’s customer orientation reflects the degree to which a firm tends to collect intelligence about customers and addresses customers’ needs (e.g., Im and Workman Citation2004; Kohli and Jaworski Citation1990; Narver and Slater Citation1990; Verbeke et al. Citation2008; Franke, Keinz, and Steger Citation2009). Such behavioral tendencies both are accessible to customers and may be interpreted as signals of a firm’s customer centricity. To illustrate, imagine a customer who is regularly asked by a firm to give feedback and experiences that the firm intensively uses her feedback to improve its products and services. This customer is likely to infer from her experience that the firm regards customers’ interests as central. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H1: A firm’s customer orientation has a positive effect on perceived customer centricity.

Beyond the organizational level, customer orientation has been conceptualized on the individual customer-contact level (e.g., Cross et al. Citation2007). Salespeople’s customer orientation focuses on this individual customer-contact level and reflects salespeople’s tendency or predisposition to meet customer needs (Brown et al. Citation2002, 111). Customer-oriented salespeople focus on the understanding of customer needs, low-pressure selling, and problem-solution selling approaches (Saxe and Weitz Citation1982).

Parallel to our argument regarding a firm’s customer orientation, we expect that customers base their evaluation of a firm’s customer centricity on salespeople’s customer orientation as a diagnostic cue (Feldman and Lynch Citation1988). Specifically, if a firm’s salespeople aim to identify customers’ needs, engage in problem-solution selling approaches, and conduct low-pressure selling (Saxe and Weitz Citation1982; Homburg, Müller, and Klarmann Citation2011b), customers might conclude that the firm regards customers’ interests as central.

The potentially crucial role of salespeople in this respect has also been highlighted by prior research. In particular, as salespeople are the key intermediary between the firm and customers, they have the crucial role to cater to customers’ interests throughout the sales process (Sirdeshmukh, Singh, and Sabol Citation2002; Palmatier, Scheer, and Steenkamp Citation2007). They are therefore a key resource for the implementation of a firm’s customer centricity, which is highly palpable for the customer (Sheth, Sisodia, and Sharma Citation2000; Shah et al. Citation2006). Therefore, we propose the following:

H2: Salespeople’s customer orientation has a positive effect on perceived customer centricity.

Customers who perceive a firm as customer centric experience their interests to reside in the center of the firm’s actions and are thus likely to expect increased benefits along their relationship with the firm. Specifically, customer-centric firms tailor their activities to better respond to customer demands, which enables them to meet customer needs and thus engender customer satisfaction (Sheth, Sisodia, and Sharma Citation2000; Shah et al. Citation2006). As a result, customers should be motivated to purchase a higher share of their overall demand from that firm (e.g., Kumar, Venkatesan, and Reinartz Citation2008; Palmatier et al. Citation2006). Furthermore, if a firm is perceived to prioritize its customers and to offer superior customer value, customers are likely to develop loyalty intentions (Gulati Citation2007; Lee et al. Citation2015). Therefore, we suggest the following:

H3: Perceived customer centricity has a positive effect on (a) sales revenue with a customer and (b) customer loyalty.

We expect the effects of perceived customer centricity on sales revenue and customer loyalty to depend principally on customer perceptions of the firm’s prices. In line with equity theory, customers are likely to have higher expectations of a firm’s performance if a firm demands high prices (e.g., Rao and Monroe Citation1989; Dodds et al. Citation1991). Such elevated expectations are more likely to be confirmed by firms perceived as customer centric because these firms tend to offer additional value by putting customers’ interests at the center of all of their actions. Therefore, we suggest that customers who perceive the prices of the firm as high might be more demanding and, thus, might ascribe a greater importance to high customer centricity for remaining loyal and extending business with the firm.

By contrast, customers who perceive the prices of the firm as low might particularly remain loyal and extend business because of their economic benefits rather than their perception of being the center of the firm’s attention (Oliver Citation1999; Gustafsson, Johnson, and Roos Citation2005; Wieseke, Alavi, and Habel Citation2014). Therefore, higher perceptions of customer centricity might transfer less to increases in sales revenue or customer loyalty if customers perceive the prices of the firm as low. We hypothesize the following:

H4: A customer’s price perception moderates the effect of perceived customer centricity on (a) sales revenue and (b) customer loyalty. Specifically, the effect of perceived customer centricity on sales revenue and customer loyalty is more positive when customers perceive prices as high.

Study 3: Examining antecedents and consequences of perceived customer centricity

Data collection and sample

Study design and procedure. To collect the data for Study 3, we collaborated with a multinational information technology firm (IT firm). The IT firm provided us with the contact data of 9,566 of their German customers’ key informants. Key informant surveys like ours are a well-established data source in sales and marketing research to provide reliable and valid survey results (e.g., Homburg et al. Citation2012; John and Reve Citation1982). When dispatching the survey to the IT firm’s customers we used a well-established online survey tool and provided a lottery for a tablet as incentive for the participants of the survey. We matched survey responses of the IT firm’s customers with corresponding data on sales revenue from the company’s database by using a unique identifier for each customer.

Measures

This study employs measurements that are established in the marketing literature with adjustments to suit our study’s context (see Appendix 1). Our key dependent variables are sales revenue and customer loyalty. In line with prior works, we chose customer’s sales revenue with the IT firm over one year as the dependent variable (e.g., Habel, Alavi, and Pick Citation2017). Customer loyalty was measured by using a two-item scale that was administered to customers of the IT firm and was based on Zeithaml, Berry, and Parasuraman (Citation1996).

We incorporated a firm’s customer orientation and salespeople’s customer orientation as independent variables in our model. To measure a firm’s customer orientation, we used a four-item scale based on Im and Workman (Citation2004) and Narver and Slater (Citation1990). Salespeople’s customer orientation was assessed by four items based on Saxe and Weitz (Citation1982) and Dwyer, Hill, and Martin (Citation2000) that have been shown to be highly reliable by previous research (e.g., Homburg Müller, and Klarmann Citation2011a,b). Our moderator variable customer price perception was measured by two items that are based on Bornemann and Homburg (Citation2011). To reduce omitted variable bias, we controlled for respondents’ quality perception, competition intensity, length of relationship with the supplier, and size of respondents’ firm. Importantly, because all customers evaluated the same supplier, by design we additionally control for a firm’s organizational structure, information technologies, and marketing strategies.

Sample characteristics

The data set of Study 3 comprises responses from a total of 1,089 customers (of 9,566), reflecting a response rate of 10.91%. A comparison of early and late respondents indicated that nonresponse bias was not an issue in our data (Armstrong and Overton Citation1977). All participating customers are system vendors in a business-to-business context that obtain products and services from the IT firm. The customers offer these products and services to their own customers, who are mostly end customers such as small- and medium-sized companies. presents details on the sample characteristics.

Psychometric properties of measurement variables

presents descriptive statistics, psychometric properties, and intercorrelations of the study’s core variables. Overall, the results of the confirmatory factor analysis indicate that the hypothesized model fits the data well (e.g., RMSEA = .063; CFI = .944; TLI = .933; SRMR = .032). No Cronbach’s alpha value is smaller than .68, and no average variance extracted is below .60, thereby exceeding the recommended thresholds (Bagozzi and Yi Citation1988). In addition, we assessed discriminant validity by using the criterion developed by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981). All average variances extracted exceeded the squared correlations between all pairs of constructs and met this criterion.

Table 5. Study 3: Correlations and psychometric properties of variables.

Model estimation and results

Model specification

We conducted a path model approach to test our hypotheses. In our main effects model, we investigated the effects of a firm’s customer orientation and salespeople’s customer orientation on perceived customer centricity and examined how perceived customer centricity affects sales revenue and customer loyalty. To examine whether customers’ price perception influences the effects of perceived customer centricity on sales revenue and customer loyalty, we included corresponding interaction effects. Therefore, we followed the procedure outlined by Aiken and West (Citation1991, 9) and included the interaction term of perceived customer centricity and price perception as an additional predictor on sales revenue and customer loyalty in our model. We calculated the interaction term by multiplying the mean-centered variables perceived customer centricity and price perception. Furthermore, we employed the procedure by Ganzach (Citation1998) by additionally including quadratic effects of perceived customer centricity and price perception on sales revenue and customer loyalty to account for potential collinearity of predictors and moderators. In addition, we controlled for the effects of a firm’s and salespeople’s customer orientation on sales revenue and customer loyalty and included several control variables (customers’ quality perception, length of relationship with the IT firm, competition intensity, and customer size).

Results

presents our results of Study 3. Model 2 is the full model including interaction effects as illustrated in . The effect of firm’s customer orientation on perceived customer centricity is positive and significant (bFirm’s customer orientation → perceived customer centricity = .40, p < .01). This offers support for H1 and suggests that in line with our reasoning, a firm’s customer orientation is associated with higher levels of perceived customer centricity. Furthermore, the effect of salespeople’s customer orientation on perceived customer centricity is positive and significant (bSalespeople’s customer orientation → perceived customer centricity = .17, p < .01). Thus, H2 is supported.

Table 6. Study 3: Results of path modeling.

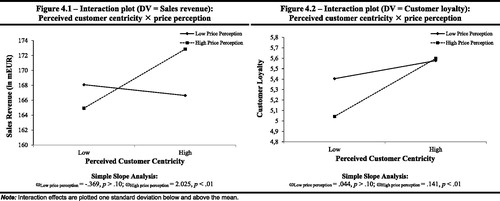

Results of the consequences of perceived customer centricity offer support for H3a and H3b by revealing that perceived customer centricity has a positive and significant impact on sales revenue (bPerceived customer centricity → sales revenue = .83, p < .05) and customer loyalty (bPerceived customer centricity → customer loyalty = .09, p < .01). Furthermore, we examined whether customers’ price perceptions influence the effects of perceived customer centricity on sales revenue and customer loyalty. Our results offer support for H4a by showing that the interaction effect of perceived customer centricity and price perception on sales revenue is positive and significant (bPerceived customer centricity × price perception → sales revenue = 1.32, p < .01). reveals further insights by indicating that the effect of perceived customer centricity on sales revenue is positive and significant if customers perceive a firm’s prices as high (ωHigh = 2.03, p < .01) but becomes nonsignificant when customers perceive a firm’s prices as low (ωLow = -.37, p > .10). Thus, customers who perceive firm prices as high tend to have a higher sales revenue when they perceive the firm to be highly customer centric. Furthermore, our results offer support for H4b by showing that the interaction effect of perceived customer centricity and price perception on customer loyalty is positive and significant (bPerceived customer centricity × price perception → customer loyalty = .05, p < .05). offers further support for the reasoning that customer loyalty can be based either on prices of a firm or on the performance that a firm offers. Specifically, reveals that the effect of perceived customer centricity on customer loyalty is not significant when customers perceive a firm’s prices as low (ωLow = .04, p > .10) whereas it is significant and positive if customers perceive a firm’s prices as high (ωHigh = .14, p < .01).

In addition, we conducted mediation analyses to explore whether the effects of a firm’s and salespeople’s customer orientation on sales revenue and customer loyalty are explained by perceived customer centricity. presents our results. We find significant and positive indirect effects of firm’s and salespeople’s customer orientation on both sales revenue and customer loyalty. Thus, perceived customer centricity mediates the influence of firm’s and salespeople’s customer orientation on sales revenue and customer loyalty. Specifically, the effect of salespeople’s customer orientation on customer loyalty is partially mediated by perceived customer centricity, and the effects of firm’s customer orientation on sales revenue and customer loyalty and the effect of salespeople’s customer orientation on sales revenue are fully mediated by perceived customer centricity.

Table 7 Study 3: Results of mediation analyses.

Supplemental analyses

We conducted two robustness checks to ensure the validity of our findings and of the perceived customer centricity scale. First, to ensure that common method variance does not affect our results, we followed the procedure outlined by Ramani and Kumar (Citation2008; see also, e.g., Griffith and Lusch Citation2007; Josiassen Citation2011) and conducted both a confirmatory factor analytical approach to Harman’s one-factor test and the marker-variable approach developed by Lindell and Whitney (Citation2001). Results of the factor analytical approach to Harman’s one-factor test show a poor fit of the one-factor model (e.g., RMSEA = .17; CFI = .54; TLI = .50), which offers first indications that common method variance does not affect our findings. To substantiate these findings, we conducted the marker-variable approach (Lindell and Whitney Citation2001) and considered the length of the relationship between the IT firm and its customer as a marker variable. Using the lowest positive correlation between the marker variable and one of the core variables (i.e., firm’s customer orientation r = .001; p > .10) to adjust the other correlations does not change the significance of any correlation between the core variables of the model. This result offers further support that common method variance is not an issue in our analyses.

Second, we conducted tests to evaluate the extent to which participants in Studies 2 and 3 attributed the same meaning to the latent construct (Brown Citation2014; Van de Schoot, Lugtig, and Hox Citation2012) and, thus, whether the items have equal factor loadings in both studies (i.e., metric invariance). We therefore merged the data sets of both studies and reran our factor analysis with two factors of perceived customer centricity. The loadings emerged as highly comparable for both factors, with differences ranging between .035 and .075. Results of model comparison tests revealed that metric invariance between both groups can be assumed when one factor loading of item five (“[Firm] is a customer-centric firm.”) was allowed to differ between groups (Δχ2 = 7.28; p > .10; Δ(−2*log-likelihood) = 3.64; p > .10). When all factor loadings were constrained as equal between both samples, results were mixed (Δχ2 = 20.35; p < .01; Δ(−2*log-likelihood) = 10.18; p > .10), which is not surprising given the large study sample of more than 1,300 observations. Thus, in summary, our scale exhibits at least partial metric invariance across two vastly different study contexts (Study 2: business-to-customer (B2C), financial services; Study 3: business-to-business (B2B), information technology). We consider this outcome as satisfactory seeing that full measurement invariance is unlikely (e.g., Steenkamp and Baumgartner Citation1998; Banerjee, Iyer, and Kashyap Citation2003; Erdem, Swait, and Valenzuela Citation2006; Tellis, Prabhu, and Chandy Citation2009).

Discussion

Research issues

Academia and practice have put a growing focus on the concept of customer centricity (e.g., Crecelius et al. Citation2019; Google Trends Citation2019). However, extant research has not yet provided a validated scale to measure the extent to which customers perceive a firm to be customer centric, that is, the degree to which a customer perceives a firm to put customers’ interests at the center of all of its actions. Our study takes this step and hereby contributes to academia in at least three ways.

First, our study is the first to conceptualize and operationalize customer centricity as perceived by customers. Prior research on customer centricity has mainly focused on objective firm characteristics commonly associated with customer centricity while neglecting customer perceptions (e.g., Lee et al. Citation2015, Citation2017; Sheth, Sisodia, and Sharma Citation2000; Fader Citation2012). Complementing prior research, we developed a valid and easily applicable measurement scale of customer centricity as perceived by customers. We verified the scale’s validity in two studies using different industries (banking and IT) in different cultural contexts (United States and Europe). Future sales and marketing research can build on our scale and deepen the understanding of customer centricity. Moreover, a common operationalization of customer centricity as perceived by customers makes research results comparable.

Second, our study contributes to the emergent literature stream on consequences of customer centricity (e.g., Crecelius et al. Citation2019; Lee et al. Citation2015, Citation2017; Shah et al. Citation2006). For example, Lee et al. (Citation2015) and Jayachandran et al. (Citation2005) showed that a firm’s customer-centric organizational structure improves customer relationships. Our article corroborates these results by showing that perceived customer centricity positively affects a customer’s loyalty as well as the revenue a firm generates with this customer.

Importantly, we find that these effects are not equal in size for all customers, but stronger (weaker) for customers who perceive a firm to exhibit high (low) prices. We attribute this effect to the notion that if prices are low, customer loyalty and sales revenue should particularly depend on the economic benefits provided to customers (Wieseke, Alavi, and Habel Citation2014; Gustafsson, Johnson, and Roos Citation2005), which can render perceptions of customer centricity less important. We hereby contribute to literature on contingent effects of customer centricity on desired consequences. For example, previous research identified tie strength and centrality as moderators of the effectiveness of customer centricity on firm performance (Frankenberger, Weiblen, and Gassmann Citation2013). To our best knowledge, however, ours is the first study to add customers’ perceptions of price to the literature on contingent effects of customer centricity.

Third, our study contributes to literature on how to foster customer centricity. Prior literature has examined the implementation of customer centricity through customer-centric organizational structures (e.g., Galbraith Citation2005; Shah et al. Citation2006; Lamberti Citation2013), customer-centric information technologies (e.g., Wagner and Majchrzak Citation2006; Waisberg and Kaushik Citation2009), and customer-centric marketing strategies (e.g., Lenskold Citation2004; Gurău, Ranchhod, and Hackney Citation2003; Sheth, Sisodia, and Sharma Citation2000). Adding to these findings, we show that perceived customer centricity is decisively driven by customer orientation that entails behaviors aimed at identifying and addressing customers’ needs both on the level of the firm and on the level of the salesperson (Im and Workman Citation2004; Narver and Slater Citation1990; Saxe and Weitz Citation1982). Importantly, our study illustrates the outstanding significance of the sales force when aiming to increase customers’ perceptions of customer centricity.

Limitations and avenues for future research

Like any research, ours exhibits limitations that provide interesting avenues for future study. First, our evidence of antecedents and outcomes of perceived customer centricity is correlational rather than causal. One can easily conceive arguments that the causality between our constructs is reverse to what we hypothesized. Specifically, customers who are highly loyal and have a high purchase volume may be more apt to feel that they are a priority for the supplier, and a supplier may be more apt to act in a customer-oriented way toward these valuable customers. Like other cross-sectional studies (e.g., Brown et al. Citation2002; Im and Workman Citation2004; Narver and Slater Citation1990), we cannot empirically rule out such alternative explanations.

However, we hold that it is reasonable to assume that the causality between our constructs is unlikely to be fully reversed for both theoretical and empirical reasons: (a) A causal effect of customer orientation via perceived customer centricity on customer loyalty and purchase volume can be deduced from well-established theories, such as diagnosticity theory (Feldman and Lynch Citation1988) and social exchange including equity theories (Blau Citation1964; Homans Citation1974). (b) Experimental studies have provided strong evidence that focusing on customers improves financial outcomes (e.g., Kumar, Venkatesan, and Reinartz Citation2008). Thus, contrary to fully reversed causality, we would expect bidirectional causal relationships between our constructs. This argument suggests that the coefficients in our model may be inflated and would have to be adjusted downward to understand the magnitude of the causal effects we hypothesized. We therefore urge readers to interpret the sizes of our coefficients with care.

Second, we hold that further research is needed to distinguish the concept of customer centricity from the concept of customer orientation. This seems particularly important seeing that prior literature has not provided a commonly accepted definition of customer centricity. Our literature review suggests that a key differentiator may be the active prioritization of customer interests. Future research may build on this notion and refine the conceptualization of customer centricity, particularly in comparison with customer orientation. In addition, future research might explore how companies can effectively prioritize customers to engender perceived customer centricity without undermining firm profitability.

Third, we conducted Study 3 in an information technology business-to-business context. Therefore, it is questionable to which extent these results generalize to other contexts. Future research might address this limitation by replicating our results in other industries including business-to-customer markets as well as for smaller firms. Furthermore, future research may examine the role of perceived customer centricity in services rather than in goods contexts. It may well be that the effect of customer centricity on sales revenue is stronger for services than for goods because of the higher importance to involve and co-create with customers (Lamberti Citation2013).

Fourth, we conducted Study 3 with customers of a single firm. This approach had the benefit of providing a relatively controlled environment for testing our hypotheses. However, it also precluded us from testing firm-specific antecedents of customer centricity, such as a firm’s organizational structure (e.g., Galbraith Citation2005; Shah et al. Citation2006) and information technologies (e.g., Wagner and Majchrzak Citation2006; Waisberg and Kaushik Citation2009). Future research could use our scale in cross-company and cross-industry contexts to explore such antecedents and verify the generalizability of our findings across contexts.

Managerial implications

Our study provides several actionable implications for managerial practice. First, because being perceived as customer centric is linked to customer loyalty and sales revenue, managers should strive to optimize perceived customer centricity. Thus, our study confirms that companies such as Amazon, Fresenius, and Hewlett Packard are working toward effective positionings (Amazon Citation2019; Fresenius Citation2019; Hewlett Packard Citation2019). Notably, fostering customers’ perceptions of customer centricity seems particularly sensible for companies with a high price positioning relative to competitors because customers of these companies are likely to expect special treatment (e.g., Wetzel, Hammerschmidt, and Zablah Citation2014).

Second, to foster customers’ perceptions of customer centricity, managers are well advised to foster customer orientation both on the level of the firm and on the level of salespeople. Specifically, managers should establish systems and processes to measure and address customers’ needs. They should furthermore enable and motivate their sales force to accomplish the same in individual interactions with customers. This recommendation is in line with CSO Insights (Citation2017, 7), according to which a key performance driver is salespeople’s capability to “consistently and effectively articulate a solution that is aligned to the customer’s needs.”

Notably, the previous recommendation is neither surprising nor new. Customer orientation is an extremely well-established key success factor for both companies and salespeople (e.g., Franke and Park Citation2006; Im and Workman Citation2004) and by definition closely linked to the concept of customer centricity – even to the extent that researchers have wondered whether “marketing primarily applies old and well-tried tricks” when talking about customer centricity (e.g., Gummesson Citation2008a, 326). However, interestingly, the recent surge in managers’ interest in customer centricity (e.g., Google Trends Citation2019; Kellogg Citation2019; Stanford Citation2019) suggests that managers may not necessarily make the connection between customer orientation and customer centricity. Our study may thus serve as a reminder to refocus on the fundamentals of sales and marketing when aiming to be perceived as customer centric: identifying and addressing customers’ needs rather than treating customer centricity as a matter of marketing communications. This recommendation seems particularly warranted because “customer-orientation has been applied half-heartedly and […] is supplier ego-centric rather than customer-centric” (Gummesson Citation2008b, 15). Put differently, we encourage managers to “walk the talk” when it comes to fostering perceptions of customer centricity.

Third and last, managers may use the scale developed in our study to measure perceived customer centricity. As our scale items are easy to understand and independent of a firm’s industry or context, and because the scale consists of only six items, it requires little effort to complete. Measuring perceived customer centricity may also be a means to drive organizational change. As outlined in the beginning, fostering customer centricity assumes a high priority for firms yet questions employees’ current practices – which may well evoke employees’ reactance. Firms may alleviate this reactance by measuring and communicating perceived customer centricity as well as effects of perceived customer centricity on desirable consequences. To illustrate, customers of the IT firm in Study 3 that perceived customer centricity as higher than 3.5 (the median of perceived customer centricity) generated on average 1.9 times the revenue of customers who perceived customer centricity as lower than or equal to 3.5.

Declaration of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Appendix 1. Survey constructs: Definitions and measures

Perceived customer centricity/Studies 1–3

Definition: The degree to which a customer perceives a firm to put customers’ interests at the center of all of its actions (our own definition).

We as a customer are at the center of [firm]’s actions.a

[Firm] caters its actions entirely to us as a customer.a

For [firm] we play the undeniable primary role.a

The customers are the top priority for [firm].a

[Firm] is a customer-centric firm.a

[Firm] lives the idea of “customer centricity.”a

Firm’s customer orientation/Studies 2 and 3

Definition: The degree to which a firm collects intelligence about customers to satisfy their needs and desires (based on Im and Workman Citation2004; Narver and Slater Citation1990)

[Firm] measures customer satisfaction systematically and frequently.a

[Firm] constantly monitors our level of commitment and orientation to serve our needs.a

[Firm] understands our needs better than its competitors do.a

[Firm] tries to understand its customers’ needs.a

Salespeople’s customer orientation/Studies 2 & 3

Definition: Salespeople’s tendency or predisposition to meet customer needs (based on Saxe and Weitz Citation1982; Dwyer, Hill, and Martin Citation2000).

[Salespeople] try to understand customer needs.a

[Salespeople] try to influence customers by information rather than by pressure.a

[Salespeople] focus the sales task on the product or service and the benefits it offers.a

[Salespeople] particularly focus on those benefits that are of particular relevance for the customer.a

Customer loyalty/Study 3

Definition: Customer’s intention to perform a diverse set of behaviors that signal a motivation to maintain a relationship with the focal firm (based on Zeithaml, Berry, and Parasuraman Citation1996).

We will remain loyal to [firm].

We will continue to do business with [firm] in the next few years.

Price perception/Study 3

Definition: A customer’s perception of the degree of a firm’s price level (based on Bornemann and Homburg Citation2011).

How do you assess the price level of [firm] compared to its competitors?b

How do you rate the overall price/performance ratio of [firm] compared to its competitors?b

Quality perception/Study 3

Definition: A customer’s perception of the degree of a firm’s product performance (based on Sweeney and Soutar Citation2001).

How do you evaluate [firm]’s product quality compared to its competitors.a

How do you evaluate [firm]’s service quality compared to its competitors.a

How do you evaluate [firm]’s quality of customer-related business processes compared to its competitors.a

Competition intensity/Study 3

Definition: The degree to which a market is characterized by competitive behavior by its market participants (based on Jaworski and Kohli Citation1993).

Competition in our business is severe.a

The number of our direct competitors is very high.a

In our market, one hears of competitive moves almost every day.a

Length of relationship/Study 3

For how many years has the business relationship with [firm] existed?c

Customer size/Study 3

How many employees work at your business unit?d

aScale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

bScale from “significantly worse” to significantly better.”

cOpen text field.

dFewer than 50; 50 to <100; 100 to <500; 500 to <1,000; 1,000 to <2,500; 2,500 to <5,000; 5,000 to 10,000 or more.

Habel et al Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (34.5 KB)References

- Aiken, Leona S., and Stephen G. West. 1991. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Alavi, Sascha, Torsten Bornemann, and Jan Wieseke. 2015. “Gambled Price Discounts: A Remedy to the Negative Side Effects of Regular Price Discounts.” Journal of Marketing 79 (2):62–78. doi: 10.1509/jm.12.0408.

- Amazon. 2019. “Our DNA.” Accessed March 12, 2019. https://www.amazon.jobs/en/working/working-amazon.

- Armstrong, J. Scott, and Terry S. Overton. 1977. “Estimating Nonresponse Bias in Mail Surveys.” Journal of Marketing Research 14 (3):396–402. doi: 10.1177/002224377701400320.

- Babin, Barry J., William R. Darden, and Mitch Griffin. 1994. “Work and/or Fun: Measuring Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Value.” Journal of Consumer Research 20 (4):644–56. doi: 10.1086/209376.

- Bagozzi, Richard P., and Youjae Yi. 1988. “On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 16 (1):74–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02723327.

- Banerjee, Subhabrata Bobby, Easwar S. Iyer, and Rajiv K. Kashyap. 2003. “Corporate Environmentalism: Antecedents and Influence of Industry Type.” Journal of Marketing 67 (2):106–22. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.67.2.106.18604.

- Bearden, William O., Richard G. Netemeyer, and Jesse E. Teel. 1989. “Measurement of Consumer Susceptibility to Interpersonal Influence.” Journal of Consumer Research 15 (4):473–81. doi: 10.1086/209186.

- Biehal, Gabriel J., and Daniel A. Sheinin. 2007. “The Influence of Corporate Messages on the Product Portfolio.” Journal of Marketing 71 (2):12–25. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.71.2.012.

- Blau, Peter M. 1964. Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York: Wiley.

- Bolton, Mike. 2004. “Customer Centric Business Processing.” International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 53 (1):44–51. doi: 10.1108/17410400410509950.

- Bornemann, Torsten, and Christian Homburg. 2011. “Psychological Distance and the Dual Role of Price.” Journal of Consumer Research 38 (3):490–504. doi: 10.1086/659874.

- Brown, Timothy A. 2014. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Brown, Tom, John C. Mowen, D. Todd Donavan, and Jane W. Licata. 2002. “The Customer Orientation of Service Workers: Personality Trait Effects on Self-and Supervisor Performance Ratings.” Journal of Marketing Research 39 (1):110–9. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.39.1.110.18928.

- Burmann, Christoph, Jörg Meurer, and Christopher Kanitz. 2011. “Customer Centricity as a Key to Success for Pharma.” Journal of Medical Marketing 11 (1):49–59.

- Cadogan, John W., and Nick Lee. 2013. “Improper Use of Endogenous Formative Variables.” Journal of Business Research 66 (2):233–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.08.006.

- Cheng, Hsing Kenneth, and Kutsal Dogan. 2008. “Customer-Centric Marketing with Internet Coupons.” Decision Support Systems 44 (3):606–20. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2007.09.001.

- Churchill, Gilbert A. Jr, 1979. “A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs.” Journal of Marketing Research 16 (1):64–73. doi: 10.1177/002224377901600110.

- Crecelius, Andrew T., Justin M. Lawrence, Ju-Yeon Lee, Son K. Lam, and Lisa K. Scheer. 2019. “Effects of Channel Members’ Customer-Centric Structures on Supplier Performance.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 47 (1):56–75. doi: 10.1007/s11747-018-0606-5.

- Cronbach, Lee J. 1951. “Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests.” Psychometrika 16 (3):297–334. doi: 10.1007/BF02310555.

- Cross, Mark E., Thomas G. Brashear, Edward E. Rigdon, and Danny N. Bellenger. 2007. “Customer Orientation and Salesperson Performance.” European Journal of Marketing 41 (7/8):821–35. doi: 10.1108/03090560710752410.

- CSO Insights. 2017. “Running Up the Down Escalator: 2017 CSO Insights World-Class Sales Practices Report.” CSO Insights Research Report. Chicago: Miller Heiman Group.

- DeVellis, Robert F. 2003. “Factor Analysis. Scale Development, Theory and Applications.” Applied Social Research Method Series 26:10–137.

- Dick, Alan, Dipankar Chakravarti, and Gabriel Biehal. 1990. “Memory-Based Inferences during Consumer Choice.” Journal of Consumer Research 17 (1):82–93. doi: 10.1086/208539.

- Dodds, William B., Kent B. Monroe, and Dhruv Grewal. 1991. “Effects of Price, Brand, and Store Information on Buyers’ Product Evaluations.” Journal of Marketing Research 28 (3):307–19. doi: 10.1177/002224379102800305.

- Dwyer, Sean, John Hill, and Warren Martin. 2000. “An Empirical Investigation of Critical Success Factors in the Personal Selling Process for Homogenous Goods.” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 20 (3):151–9.

- Erdem, Tülin, Joffre Swait, and Ana Valenzuela. 2006. “Brands as Signals: A Cross-Country Validation Study.” Journal of Marketing 70 (1):34–49. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.2006.70.1.34.

- Fader, Peter. 2012. Customer Centricity: Focus on the Right Customers for Strategic Advantage. Philadelphia: Wharton Digital Press.

- Feldman, Jack M., and John G. Lynch. 1988. “Self-Generated Validity and Other Effects of Measurement on Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior.” Journal of Applied Psychology 73 (3):421–36. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.73.3.421.

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. “Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error.” Journal of Marketing Research 18 (1):39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104.

- Franke, George R., and Jeong-Eun Park. 2006. “Salesperson Adaptive Selling Behavior and Customer Orientation: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Marketing Research 43 (4):693–702. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.43.4.693.

- Franke, Nikolaus, Peter Keinz, and Christoph J. Steger. 2009. “Testing the Value of Customization: When Do Customers Really Prefer Products Tailored to Their Preferences?” Journal of Marketing 73 (5):103–21. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.73.5.103.

- Frankenberger, Karolin, Tobias Weiblen, and Oliver Gassmann. 2013. “Network Configuration, Customer Centricity, and Performance of Open Business Models: A Solution Provider Perspective.” Industrial Marketing Management 42 (5):671–82. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2013.05.004.

- Fresenius, Kabi. 2019. “Our Values.” Accessed March 5, 2019. https://www.fresenius-kabi.com/responsibilities/our-values.

- Galbraith, Jay R. 2002. “Organizing to Deliver Solutions.” Organizational Dynamics 31 (2):194–207. doi: 10.1016/S0090-2616(02)00101-8.

- Galbraith, Jay R. 2005. “Become Customer-Centric.” T + D Training & Development 59 (10):14–5.

- Galbraith, Jay R. 2011. Designing the Customer-Centric Organization: A Guide to Strategy, Structure, and Process. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Ganzach, Yoav. 1998. “Nonlinearity, Multicollinearity and the Probability of Type II Error in Detecting Interaction.” Journal of Management 24 (5):615–22. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2063(99)80076-2.

- Gerbing, David W., and James C. Anderson. 1988. “An Updated Paradigm for Scale Development Incorporating Unidimensionality and Its Assessment.” Journal of Marketing Research 25 (2):186–92. doi: 10.1177/002224378802500207.

- Google Trends. 2019. “Customer Centricity.” Accessed March 5, 2019. https://trends.google.de/trends/explore?date=all&q=customer%20centricity.

- Griffith, David A., and Robert F. Lusch. 2007. “Getting Marketers to Invest in Firm-Specific Capital.” Journal of Marketing 71 (1):129–45. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.71.1.129.

- Gulati, Ranjay. 2007. “Silo Busting: How to Execute on the Promise of Customer Focus.” Harvard Business Review 85 (5):98–108.

- Gummesson, Evert. 2008a. “Customer Centricity: Reality or a Wild Goose Chase?” European Business Review 20 (4):315–30. doi: 10.1108/09555340810886594.

- Gummesson, Evert. 2008b. “Extending the Service-Dominant Logic: From Customer Centricity to Balanced Centricity.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 36 (1):15–7. doi: 10.1007/s11747-007-0065-x.

- Gurău, Călin, Ashok Ranchhod, and Ray Hackney. 2003. “Customer-Centric Strategic Planning: Integrating CRM in Online Business Systems.” Information Technology and Management 4 (2/3):199–214.

- Gustafsson, Anders, Michael D. Johnson, and Inger Roos. 2005. “The Effects of Customer Satisfaction, Relationship Commitment Dimensions, and Triggers on Customer Retention.” Journal of Marketing 69 (4):210–8. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.2005.69.4.210.

- Habel, Johannes, Laura M. Schons, Sascha Alavi, and Jan Wieseke. 2016. “Warm Glow or Extra Charge? The Ambivalent Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility Activities on Customers’ Perceived Price Fairness.” Journal of Marketing 80 (1):84–105. doi: 10.1509/jm.14.0389.

- Habel, Johannes, Sascha Alavi, and Doreén Pick. 2017. “When Serving Customers Includes Correcting Them: Understanding the Ambivalent Effects of Enforcing Service Rules.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 34 (4):919–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2017.09.002.

- Hewlett Packard. 2019. “HP Corporate Objectives and Shared Values.” Accessed March 5, 2019. http://www.hp.com/hpinfo/abouthp/values-objectives.html.

- Homans, George C. 1974. Social Behavior: Its Elementary Forms. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Homburg, Christian, John P. Workman, and Ove Jensen. 2000. “Fundamental Changes in Marketing Organization: The Movement toward a Customer-Focused Organizational Structure.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 28 (4):459–78. doi: 10.1177/0092070300284001.

- Homburg, Christian, Martin Klarmann, Martin Reimann, and Oliver Schilke. 2012. “What Drives Key Informant Accuracy?” Journal of Marketing Research 49 (4):594–608. doi: 10.1509/jmr.09.0174.

- Homburg, Christian, Michael Müller, and Martin Klarmann. 2011a. “When Does Salespeople’s Customer Orientation Lead to Customer Loyalty? The Differential Effects of Relational and Functional Customer Orientation.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 39 (6):795–812. doi: 10.1007/s11747-010-0220-7.

- Homburg, Christian, Michael Müller, and Martin Klarmann. 2011b. “When Should the Customer Really Be King? On the Optimum Level of Salesperson Customer Orientation in Sales Encounters.” Journal of Marketing 75 (2):55–74. doi: 10.1509/jm.75.2.55.

- Im, Subin, and John P. Workman. Jr. 2004. “Market Orientation, Creativity, and New Product Performance in High-Technology Firms.” Journal of Marketing 68 (2):114–32. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.68.2.114.27788.

- Imhoff, Claudia, Lisa Loftis, and Jonathan G. Geiger. 2001. Building the Customer-Centric Enterprise: Data Warehousing Techniques for Supporting Customer Relationship Management. New York: John Wiley & Sons..

- Jaworski, Bernhard J., and Ajay K. Kohli. 1993. “Market Orientation: Antecedents and Consequences.” Journal of Marketing 57 (3):53–70. doi: 10.1177/002224299305700304.

- Jayachandran, Satish, Subhash Sharma, Peter Kaufman, and Pushkala Raman. 2005. “The Role of Relational Information Processes and Technology Use in Customer Relationship Management.” Journal of Marketing 69 (4):177–92. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.2005.69.4.177.

- John, George, and Torger Reve. 1982. “The Reliability and Validity of Key Informant Data from Dyadic Relationships in Marketing Channels.” Journal of Marketing Research 19 (4):517–24. doi: 10.1177/002224378201900412.

- Josiassen, Alexander. 2011. “Consumer Disidentification and Its Effects on Domestic Product Purchases: An Empirical Investigation in The Netherlands.” Journal of Marketing 75 (2):124–40. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.75.2.124.

- Kaiser, Henry F. 1960. “The Application of Electronic Computers to Factor Analysis.” Educational and Psychological Measurement 20 (1):141–51. doi: 10.1177/001316446002000116.

- Kaushik, Avinash. 2009. Web Analytics 2.0: The Art of Online Accountability and Science of Customer Centricity. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Kellogg. 2019. “The Customer-Focused Organization.” Accessed March 5, 2019. https://www.kellogg.northwestern.edu/executive-education/individual-programs/executive-programs/focus.aspx.