Introduction

The history of tenant movements and rent strikes is a blind spot in the general history of emancipatory social movements. As the primary protagonists of protest against the capitalist mode of production, working-class labour movements have been the main subject of research in this field, with housing struggles and tenant movements depicted as a derivative of their class struggle (Madder and Marcuse Citation2016). Growing interest in housing and residential struggles, particularly following the financial implosion of 2008, has provided greater knowledge and research on the topic, yet scholarly literature on the historical emergence of tenant movements and the proliferation of rent strikes remains scattered and confined within its own limits. Further research is needed to trace, weave and theorise the contentious politics deployed by tenant movements through rent strikes, those particular “moments of madness” in housing struggles when “all is possible” (Zolberg Citation1972). The value of this task is twofold. On the one hand, unearthing the collective memory of tenant movements through turbulent points of history contributes to the elaboration of a critical ontology of the present housing struggles. On the other, it allows us to consider housing as a space of conflict that, under the yoke of financial capitalism, harbours the potency of an antagonist movement that is able to contest the commodification and financialisation of housing.

This article seeks to contribute to this task by analysing rent strikes and the tenant movements conducting them in terms of their theoretical and historical value for emancipatory politics. First, we theorise the rent strike as a modular repertoire of contention, building upon the theoretical endeavour developed by Tilly (Citation1986) and Tarrow (Citation1993). Theoretical reflection on the rent strike also leads us to notionally conceive it as a negative action. Secondly, by bringing in the existing literature on the rise of rent strikes at the outset of the 20th century, we contend that rent strikes have their own historical thread, which should be analysed in depth in order to understand the dynamic underpinning the contentious politics of tenants’ movements. Thirdly, we argue that the antagonism exercised by tenant movements and their contentious episodes has been transformative of legal protections in the private-rental housing sector. Put simply, the development and evolution of tenants’ rights, such as the right to withhold rent, should be seen as the constituent force of tenant organisation. Last but not least, this article seeks to strengthen the theoretical link which weaves together social reproduction theory (SRT) and housing struggles conducted by tenant movements. The fundamental insights of SRT are essential to understand the underestimation of housing struggles in particular, and that of social reproduction struggles in general (Bhattacharya Citation2017). We therefore understand tenant struggles and rent strikes as historical applications of the key theoretical components outlined by SRT.

The rent strike as a negative collective action

Although the strike tactic has a very long history, it is a tactic historically attached to the labour movement and the sphere of production as an expression of workers’ unrest. The strike is often conceived as the working-class collective refusal to work under the conditions required by employers. Using the concept of the repertoire developed by Charles Tilly (Citation1986), the strike tactic evokes the repertoire of collective action undertaken by labour unions to short-circuit the labour process – and hence the process of creating value – for a political aim, which is often distinguished between economic conditions (improving wages and benefits) and labour practices (intended to improve labour conditions). Yet the strike tactic has also been undertaken outside the realm of the labour movements. Insofar as capital has become a mechanism for capturing value from the metropolis itself (Negri Citation2018), it is particularly relevant to conceptualise the strike beyond the sphere of production. Following Tarrow’s (Citation1993) formulation, the strike tactic can be understood as a modular form of collective action, as it can be employed by a variety of social actors in a variety of settings against a variety of opponents. Its capacity for adaptation to different contexts has made it one of the most flexible repertoires of collective action for social and labour movements.

The modularity of this form of contention is shown in other forms of strikes such as student strikes, hunger strikes in prisons, or rent strikes. Our claim is that rent strikes are a particular form of contentious collective action that has been underestimated, despite its wide use throughout the 20th century by tenants’ organisations and associations. A rent strike consists in the concerted withholding or reduction of rents by tenants. It is a strategy deployed by tenants for a political goal that opens up a conflict with the landlord in order to fight against rent hikes or poor housing conditions. Rent strikes are tactics of economic bargaining in the reproductive sphere to force landlords to negotiate and accept tenants’ claims. If we follow the seminal distinction of contentious politics made by McAdam et al. (Citation2001), a rent strike is a form of transgressive contention since it challenges established institutional means and crosses into forbidden or unknown territory in a given political regime by employing innovative collective action. Although rent strikes are not a legal right in most countries, some jurisdictions have included partial rent strikes in their legislation in order to protect tenants against abusive practices by landlords, as we will explain in section four.

The potential of rent strikes lies in the fact that they collectively end the monthly economic transfer tenants make to their landlords. The rent strike can be understood as a process of active demobilisation, a contentious action that, in its refusal of rent payment, catalyses a conflict to reconfigure the power relations between tenant and landlord. Seen from this lens, a rent strike is a negative form of contention, as it refuses and disobeys by not doing. Negative forms of collective action have been conceived by Virno (Citation2021, Citation2013) as a particular emotive tonality that characterises the state of the multitude, understood here as a political subject, namely the political existence of many in the public scene. As Virno (Citation2021) has recently argued, negative actions forbid the energheia of a given dynamis in order to deploy the energheia of a totally different dynamis. In other words, negative actions do not entail the collapse of collective praxis, but rather they lay out a different web of contentious relations. The active demobilisation – or negative action – performed by the rent strike is an end in itself: its political power takes shape insofar as it is deployed in the concerted process of consciousness-raising. The rent strike necessarily engenders uncertainty, but it is an organised uncertainty, as it also produces a process of collective learning, mutual aid, and cooperation. It is in the process itself where the potency – the energheia – of a rent strike blossoms, though there always remains a degree of indeterminacy and contingency.

The rent strike as a tenant repertoire of contention also lends to reflection on the political conditions of possibility that facilitate the emergence of emancipatory politics in the field of housing. We contend that the history of rent strikes, and more broadly the history of the tenant movement, can be understood from the perspective of a constituent materialism that very much bears the stamp of Autonomist Marxism (Hardt and Virno Citation1996; Negri Citation1999; Wright Citation2002). Autonomist Marxism set the stage for a revolutionary understanding of the dialectical relationship between capital and labour. It understands that the development of the capitalist regime of production must be analysed as a political response to working-class struggle (Tronti Citation2019). It is the socio-political organisation of the working-class, and the contentious politics it performs, that constitutes a creative force which shapes the way capital responds and adapts its power of command in the future (Tronti Citation2019). The Autonomist thinker Antonio Negri (Citation1999) elaborated the concept of “constituent power” to move beyond its conceptual antagonist, sovereign power. Where sovereign power attempts to deploy its strategies of subjection and domination, it will always clash against a line of flight that opens the antagonist political field, namely constituent power (Negri Citation1999). The political operation of Autonomist Marxism was geared towards establishing a novel understanding of class struggle. In a theoretical reformulation of the emancipatory subject in the post-Fordist regime of production, Italian operaismo developed the concept of “class-composition”. With this notion, Autonomist thinkers aimed to overcome Hegel’s dialectical method by removing any ontological consistency from the concept of the working-class as the unique revolutionary subject (Tronti Citation2019). Put simply, capital does not give an ontological status of class subject to the working class. Rather, it is the struggle that produces a collective subject that ultimately develops a class consciousness. There is no class subject prior to social struggle: operaismo thinks in terms of autonomy and antagonism. This class-composition is the base from which rent strikes emerge: class is constituted through struggle, in the awareness that an individual problem is a collective issue that can be collectively reverted.

The development of tenant movements and the proliferation of rent strikes can be understood from this political conception. The tenant organisation turns the problem of workers and capital upside down, shifting the political orientation towards analysing the antagonism performed by tenants in order to understand capitalist development in a rentier economy.Footnote1 The response of landlords is subordinated to tenant struggle, and the set of rules and laws governing the private-rental housing sector are the result of previous tenant struggles. This political conception can be viewed through genealogical research on the rent strikes of the early 20th century, to which we now turn.

The history of rent strikes in the early 20th century

The existing literature on tenant movements has focused on examining major historical events where their collective action centred around rent withholding. Knowledge of the external conditions that made the emergence of rent strikes possible, however, is less developed. In what ways do rent strikes constitute a contagious repertoire of contention that is reproduced in different places? To what extent does the frequency of rent strikes depend on economic fluctuations? What are the political and legal configurations resulting from such contention in the field of housing? We argue that rent strikes have their own historical thread which must be fully developed to understand the dynamics of contention underlying the rise of tenant movements. As existing literature demonstrates, the rise of rent strikes in different countries at the beginning of the 20th century displays a pattern of discontinuity that remains to be examined.

The first evidence of rent withholding as a collective praxis harkens back to at least the 15th century, when the struggle between lords and tenants was one of the factors leading to social and agrarian changes. The historical work of Dyer (Citation1968) shows how the collective action of peasants was recorded in the arrears list as “because the tenants refuse to pay” (quia tenentes negant solvere). Rent strikes were instrumental in securing rent reductions, as they formed the most effective sanction for tenants in any bargaining that took place over the level of rent in the 15th century. It was also when the idea of a “fair rent” emerged as a principle of the moral economy of tenants (Dyer Citation1968). Nonetheless, there is a dearth of research regarding the frequency of rent withholding throughout the Middle and Classic Ages. A large historical leap must be made to the 19th century to find documentary evidence on tenant movements. At the end of 1880s, with the making of the urban working-class in European cities, it was a common practice to withhold rents. According to Forsell (Citation2006, Citation2003), there is evidence on the establishment of landlords’ organisations in cities such as Stockholm and Berlin in order to defend their properties against the widespread worker practice of rent withholding. Landlords created blacklists of workers who either refused to pay or were unable to meet rental payments. The emerging rentier economy was not an established practice, and the capitalist drive in the urban built environment was yet to be developed. As Forsell (Citation2003) has noted, the conservative German press of that time reproduced the landlords’ perspective in the following manner: “A man has to be educated to understand how the rent-market functions.” The disciplining of the working-class under the industrial regime of production was accompanied by the disciplining of tenants in the private-rental sector.

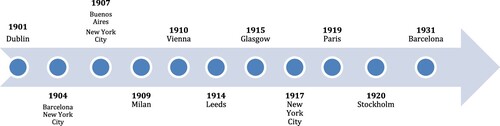

We can see the modern formulation of the tenant–landlord antagonism in the 19th century. Yet it is during the first decades of the 20th century that this deep-seated antagonism becomes more contentious, primarily through the emergence of rent strikes as a form of protest organised by tenant organisations and associations. We claim that the rent strikes undertaken in different countries during this period constitute a “stream of contention” (Tilly and Tarrow, Citation2015) that remains to be historically apprehended, that is, a sequence of collective claim making for housing justice that needs to be singled out for further explanation. In we present a summary of the most remarkable rent strikes that took place at the beginning of the last century.

Fig. 1. Rent Strikes (1900–1931).

Source: Authors’ elaboration from the literature consulted for this article.

Recent research by Wolf (Citation2019) reveals a forgotten episode in Irish history: in 1901, tenants on an Irish rural estate owned by Arthur French (4th Baron De Freyne) stopped paying rent. From this event, Wolf explains how a national movement emerged which fought for land reform and home rule against landlordism. The Irish tenants’ act of rebellion was debated in the Irish Parliament and made headlines in Dublin, London, and New York, among other cities. Most importantly, as the work of Wolf examined, this event culminated in a conciliatory conference between landlords and tenants’ advocates in 1902, which in turn prepared the terrain for the Wyndham Land Act of 1903, the act which signalled the end of landlordism in Ireland.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the Argentinian capital witnessed an episode that has been well documented by scholars, the Buenos Aires rent strike of 1907. Tenants of a large conventillo – tenement house – protested a 47-percent rent increase by striking against their landlord, which prompted a reaction in nearby buildings, with data suggesting that roughly 2,000 buildings in Buenos Aires had joined the strike by the end of 1907 (Baer Citation1993). This rent strike has been studied as one of the largest forms of working-class collective action in early 20th-century Argentina. What remains most notorious in the Argentinian rent strike is the crucial role played by women. It is not a coincidence that the strike is known as the “broom strike”, since it was the women who “swept” the rent hikes away from their homes by refusing to pay higher rents to their landlords, an image epitomised through the organisation of “broom parades” (“marcha de las escobas”) in the streets to make their struggle visible and demand a 30-percent rent reduction (Wood and Baer Citation2006). The response from the landlords was fierce, sparking a mass wave of evictions and blacklisting tenants who joined or supported the rent strike (Castro Citation1990).

Among European countries, the organisation of tenants became an important feature of the working-class movement. According to Spanish newspapers of the time, Milan established a tenant union in 1909 which is said to have called for rent strikes during the first decades of the 20th century. During the years preceding World War I, tenants in Budapest employed rent strikes as a strategy against landlords who increased rents, together with mass demonstrations in the streets (Gyáni Citation1990). In 1911, a tenants association was created in Vienna in response to a 20-percent rent increase, which sparked rent strikes (Banik-Schweitzer Citation1990). According to Forsell (Citation2003), women played a leading role in Vienna’s rent strikes from 1910 to 1911, as they were generally responsible for household budgets and carrying out rental payments, a role that resulted in their direct confrontation with landlords. In 1914, the Property Owners Association called for a rent increase in Leeds, which resulted tenants also contested through a rent strike (Bradley Citation1997). A Tenants Defence League was formed to spread the rent campaign across the city through a series of public meetings and neighbourhood canvassing (Bradley Citation1997). The Leeds rent strike was among the first tenant campaigns to demand public housing.

The year 1915 is a remarkable date for the memory of the Scottish working class and generally for the history of the socialist movement. The 1915 Glasgow rent strike arguably represents the most successful housing struggle the UK has ever seen. By resisting evictions and collectively withholding increased rents from landlords, tenants multiplied their power to win their immediate urban struggle for rent controls, while forcing the state to nationalise housing policy, ultimately laying the foundation for mass public housing in the 20th century. The Glasgow rent strike is also remarkable for the role of women’s association, and it is also known as the strike of “Mrs Barbour’s army”. Mary Barbour led the movement to reduce rents together with the Glasgow Women’s Housing Association, with leading roles also played by Agnes Dollan and Helen Crawford, who were active in the Scottish labour movement (Melling Citation1983).

The period between the two World Wars was an intense period of tenant organising, as the housing question remained a crucial issue for industrial workers in large cities. In 1919 and 1923, historiographical work documents the call for direct action made by the Fédération des Locataires de la Seine (FLS), using the threat of “la grève des loyers” against the rent hikes (Magri Citation1986). The antagonism between tenants and landlords was particularly visible during the period 1919–1925 of the Parisian tenant movement, which demanded public housing, rent reductions and improvement of housing quality (Magri Citation1986). A similar period is seen in the work of Fogelson (Citation2013), who documented the history of rent strikes in New York between 1917 and 1929.

The influence of the Parisian tenant strikes was crucial for the development of the rent strike that took place in Barcelona in 1931. Renters in Barcelona were subjected to severe housing precarity, with the subdivision of apartments, the absence of public investment in housing and the landlord lobby taking the upper hand thanks to a housing shortage in the city (Ealham Citation2005). The Tenants’ Union (Sindicato de Inquilinos) launched a rent strike with the support of the Builders’ Union and the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT [National Confederation of Labour]), the labour union that had the largest numbers of unemployed members (Ealham Citation2005). Rent strikers announced their refusal to pay exorbitant rents and demanded a 40-percent reduction. There was a fierce response from the landlord lobby and the police, as it was not only understood as a strategy of contention against landlordism in Barcelona, but also as a reflection of the broader politics of the Second Republic in Spain.

If the art of revolution lies in “unsettling established customs by delving to their core in order to demonstrate their lack of authority and justice”, as Pascal (Citation1995: 24) put it, the history of the rent strikes and tenant activism in the early 20th century demonstrates its revolutionary character. Though they shook the foundations of the rentier economies in different countries, they did so with the same repertoire of contentious collective action.

The rent strike as a tenant’s right? Transgressive practices beyond a formal right

As we have just described, contentious mobilisations against rent hikes and crumbling housing conditions through politisation of the tenant–landlord relationship resulted in major rent strikes in the early 20th century. But such a repertoire of contention in the rental housing field has also forced the implementation of legal protections for renters. There has been an evolution of legal rights and regulations aiming to guarantee the right of rent withholding in certain cases (cf. Lawson Citation1983). The emergence of such legal schemes should be understood as a response to tenants’ collective action and rent strikes. In the same way that the right to strike has been achieved by labour unions and working-class struggles, legal protections such as the right of rent withholding in the private-rental housing sector has been attained through major contentious episodes. The collective organisation of both workers and tenants is essential to understand the contractual relationships established both in the labour sphere and the housing sector. In other words, antagonist movements in the productive and reproductive sphere are crucial to understanding the achievement of legal protections and collective rights. We trace the evolution of the “right to rent strike” as it has been established in some countries in the aftermath of tenants’ struggles.

According to the legal historiography of labour law, since the 19th century labour-specific regulations and rights have evolved in tension with workers’ struggles and mobilisations, and has been influenced by the ideological positions of organised labour (Fogelson Citation2013). Despite the lack of a well-established legal historiography in housing and rent law akin to labour law, rental housing legislation has also evolved as the result of mounting social conflicts since the beginning of the 20th century. The historical genealogy of rent strikes in the previous section substantiates this argument. Examples of this early evolution of rent regulation include the implementation of rent controls and tenant-protective legal schemes in Spain (1920), Scotland (1915) and New York (1920) (González Guzmán & Sabaté Muriel Citation2020; Gray Citation2018; Lawson Citation1983). These legal protections have limited rents and recognised collective bargaining schemes, but they have also legalised tenants’ unions – such as in Sweden (1950s) (Rolf Citation2021) – and specific forms of rent withholding, or rent striking – as in New York (1929, 1970s) (Lawson Citation1983).

There is a remarkable similarity in how labour and tenants’ movements have criticised the liberal understanding of legal contractual obligations, which presupposes the efficiency and legitimacy of contracts signed by free parties. In the same way that a worker notionally sells labour-power to an employer freely contracting the terms, a tenant freely rents a house through a contract. The equality and freedom involved in both the purchase of labour-power and the rental of a home appear as a juridical form that disguises a relation of domination. As Lewis contends in his analysis of British labour law:

The contract in question as far as workers were concerned was the contract of employment, a legally enforceable relationship subsisting between every individual employee and his employer. The nineteenth-century judges insisted that the parties to the contract were free and equal in coming together to form the contract and in the negotiation of its terms. This ignored the economic necessity of the worker to sell his labour and the fact that the employer was often powerful enough to impose his own terms. As Webb remarked: “Whenever the economic conditions of the parties are unequal, legal freedom of contract merely enables the superior in strategic strength to dictate the terms.” Trade unions were needed to redress the balance. (1976: 2)

The criticism and, above all, the class organising around labour/industrial relations have resulted in the consolidation of the legal right to strike, which has been fully legalised and turned into a basic political right with constitutional value (for instance, it was included in the French Constitution after 1946, and in the Spanish Constitution of 1978). Rent strikes have not been consolidated as political rights, but, as we shall see, are limited to allowing rent withholding under very specific circumstances. Nevertheless, the process of legalisation of the labour strike right sheds light into similar dynamics that took place in rent striking as a transgressive practice.

The path towards the legalisation of labour strikes in Western states was marked first by the decriminalisation of unions, secondly by the legalisation of trade unionism and the right of assembly, and accompanied by the constant disobedience of organised labour, which kept striking and mobilising despite facing criminal charges (Ramos Vázquez Citation2020). In the UK, in spite of its early development of legalised trade unionism, anti-union judges prosecuted strikers first via criminal and civil/tort liabilities (Lewis Citation1976). In the case of France, the acts of 1834 and 1849 which respectively prohibited unions and strikes were actively disobeyed by a population in constant revolt. Moreover, French unionists vigorously rejected the Loi Waldeck-Rousseau, which legalised unions but restricted their scope of intervention to a de-politicised defence of economic, commercial, industrial and agrarian interests (Ramos Vázquez Citation2020). In Spain, some advances were made after the 1868 revolution, with the decriminalisation of associations and the recognition of the right to assemble. Nevertheless, the Spanish Criminal Code still considered that associations with economic aims could commit a “criminal offence against property” by “altering the price of things'‘, in particular the price of labour (wages), and were therefore considered “social criminal offences” (Ramos Vázquez Citation2020: 88).

The history of rent strikes and their legal manifestations mirrors the limitations and obstacles involved in the legalisation of the labour strike. Correspondingly, in some parts of the world, the right to withhold rent has been effectively regulated and legalised, as depicted in .

Table 1. The formalisation of the right to withhold and reduce rent in European countries and in the US.

In the countries of group A in , rent strikes are allowed as a unilateral right to be exercised. Some of these coincide with the places where a tenant movement has been historically strong. The legalisation of rent strikes is also the crystallisation of a criticism of the false prevailing freedom of contract between tenants and landlords. Indeed, although the formal recognition of tenant unions and associations holds an implicit recognition of the collective nature of rent conflicts, the right to rent strike was formalised after the incorporation of contract-like doctrine into rental leases. In the case of New York, the Warranty of Habitability legislation held landlords responsible for complying with their part of the rental contract, which mostly corresponds with maintaining the habitability of rented units; in turn, if these obligations were not fulfilled, tenants had the right to rent abatements or rent withholdings (Lawson Citation1983).

Tenants under protective legal schemes allowing unilateral rent reductions, and those whose associations are institutionally recognised, arguably have greater collective bargaining power to counter the dominant position of landlords in the contractual relationship. Nevertheless, as observed by Lawson (Citation1983), “over time, the rent strike was transformed from what was perceived as a revolutionary threat to a mechanism for redress of grievances recognized in law and official programs” (Lawson Citation1983: 271). In that sense, the progress of the rent strike, Lawson argues, parallels the earlier French labour strike, insofar as it became a more accessible and “less risky way of making demands”, losing part of its expressive function and revolutionary potential in the process.

In its most protective form, the right to withhold rent is in fact limited to cases where tenants suffer from housing decay, disrepairs, and other safety issues. It does not, however, legally allow withholding rent as a protest against lawful rent increases. This limitation is reminiscent of the 19th-century Spanish judicial consideration of labour strikes – which attempted to “change the price of things” – as an “offence against Property”, and therefore, illegal. Rent strikes that go to the kernel of the rent conflict, and dispute the actual price of rent, are therefore not legally protected as a political right.

Although rent strikes have achieved formal rights, they are contentious tactics first and foremost. Tenant movements constantly develop innovative ways to use the limited legal right to rent strike in order to develop more radical ways of pressuring landlords and securing contractual and material improvements beyond the legally protected notion of “habitability” (Lawson Citation1983). Lewis explains how, in the UK, “trade unions had learnt to rely on their own industrial strength rather than the law in securing recognition and enforcing collective agreements” (Citation1976: 6). Similarly, tenant organisations and movements have learned to mobilise beyond institutional mechanisms, broadening the scope of legally recognised rights primarily through rent strikes. As a result, they remain a form of transgressive contention, rather than a legal or institutional mechanism to organise and mitigate rent conflict.

We have introduced the interconnectedness and parallels between labour and rent struggles by describing their collective articulation against the imposed individualism of contractual logics and their criticism of freedom of contract doctrine. In what follows, we further explore the ways in which residential struggles and their manifestations, such as rent strikes, are to be understood within the dynamics of capital, whereby accumulation and exploitation are also enacted in the sphere of reproduction and face resistance from below.

Social reproduction and rent: striking at point zero

SRT provides a fertile theoretical field for embedding the rent strike phenomenon and housing-related struggles in the analysis of contemporary class dynamics. SRT allows a deeper analysis of the links between labour and housing struggles by positioning the rent antagonism as integrated in both the productive and reproductive life spheres, thereby showing their interconnectedness beyond the simple production-consumption duality. In the following analysis, we emphasise the historical role of women in subsistence struggles and rent strikes, and how Marxist frameworks have been insufficient to understand and theorise the reproductive social struggles to which housing and rent struggles pertain. Secondly, we argue that SRT provides a critical analysis of capitalist dispossession in the realm of housing as well as of the rent antagonism, although its theoretical connection has been underdeveloped. Finally, we use SRT as an analytical tool to understand the current articulations of the biopolitical conflict between capital and life, namely the so-called “care crisis”, which has been aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic. We briefly introduce how the international response to this crisis was articulated through rent strikes in different parts of the world.

Women have historically played a prominent role in rent strikes and housing-related struggles. As discussed in Section 2, the history of rent strikes and tenant movements demonstrate the crucial role of women in contentious collective action. The rent strikes that took place in Buenos Aires in 1907 and Glasgow in 1915 are two examples of women’s leadership in the development of these events (Currie Citation2018; Yujnovsky Citation2004). Indeed, historical accounts are full of examples of how women have led struggles for subsistence, which, beyond housing, include other essential goods. Key examples include the women’s uprising against coal price increases in Barcelona in 1918 (Álvaro Citation2018), as well as mobilisations in the 21st century to obtain access to land for subsistence agriculture (Federici Citation2012a). That women are the main subjects organising against the withdrawal or deprivation of any basic reproductive infrastructure or subsistence good is the result of the historical development of capitalist economic and social organisation. Women’s subjective position as de facto managers of the household was forged after the privatisation and individualisation of care work. In this process, women were not only separated from the direct means of subsistence (mostly communal land) but also excluded from the productive-waged sphere and thereby confined to their patriarchal homes, where they were tasked with the reproduction of the working class under precarious conditions (Federici Citation2004; Ferguson Citation2020).

By focusing on the subjective position and role of women in capitalist social relations, SRT can unveil processes, oppressions and exploitations that are central to the functioning of capitalism beyond the point of production. In fact, SRT holds that capitalist social relations started “above all in the kitchen, the bedroom, the home”, where people assemble their means of subsistence, thereby granting centrality to “point zero”, that is, the point of reproduction (Federici Citation2012b: 8). Even more so, capitalist property relations originated with the imposition of rents on rural lands, which separated peasants – who were turned into tenants – from their direct means of subsistence (Wood Citation2002). Therefore, the monetisation and marketisation of access to indispensable means of reproduction, such as land, was arguably a central process in the formation of the proletariat.

SRT precisely aims to bring all that happens in the reproductive sphere to the analysis of capitalism, emphasising the very point at which labour power is “produced” (Bhattacharya Citation2017). Applying Marxist tradition and analytical concepts (value theory of labour, labour power, the productive-reproductive divide, etc.), SRT departs from a critique of what Marx left largely unaddressed, namely the activities – mostly informal and gendered care work – that the reproduction of labour power, that is, human life, involves. Marx, and orthodox Marxist analysis after him, reduced the question of reproduction to workers’ consumption of the commodities their wages can buy, and the (formal) work that the production of these consumed commodities requires:

… the reproduction of the working class remains a necessary condition for the reproduction of labour. … But the capitalist may safely leave this to the worker’s drives for self-preservation and propagation. All the capitalist cares for is to reduce the worker’s individual consumption to the necessary minimum. (Marx Citation1976: 718)

If we look at early analytical efforts to theorise housing and other urban community struggles as a form of class struggle, we note how they were still regarded as a matter of consumption (Castells Citation1974; Harvey Citation1976). The simple divide between consumption and production relegated such struggles to a subordinate position in relation to the productive-wage struggles of organised labour at the point of production. The use of concepts such as “collective consumption” to define community struggles (Castells Citation1974), or “consumption fund items” (Harvey Citation1976) to define housing and other infrastructures needed for reproduction, are representative of this focus. Yet housing is much more than a commodity or a basic consumption good; it is a key element for understanding social structures. Residence is a complex social relation, embedded both in the institutional and the socio-spatial structure of society (Kemeny Citation2003) and, we might add, a central element of social-reproductive dynamics. As Madden and Marcuse have argued:

… housing is the precondition both for work and for leisure. Controlling one’s housing is a way to control one’s labor as well as one’s free time, which is why struggles over housing are always, in part, struggles over autonomy. More than any other item of consumption, housing structures the way that individuals interact with others, with communities, and with wider collectives. Where and how one lives decisively shapes the treatment one receives by the state and can facilitate relations with other citizens and with social movements. No other modern commodity is as important for organizing citizenship, work, identities, solidarities, and politics. (2016: 11).

In spite of housing and residence being both economic and extra-economic relations that structures social reproduction, they have barely been analysed through the lens of SRT. Among the scarce examples of scientific literature bringing together housing or rent and social reproduction we find the work of Roberts (Citation2013), Ribera-Almandoz (Citation2019) and, more recently, Byrne (Citation2020a). Roberts contends that housing is “one of the most basic aspects of social reproduction” (2013: 9) and, according to Byrne, the “home is also a kind of centrepiece, nexus and anchor of a set of resources central to social reproduction”. Such resources are, in turn, “produced by the tenant through practical activity, i.e. labour” (2020a: 14). To a certain extent, both Currie (Citation2018) and Hughes and Wright (Citation2018) also take a SRT perspective to analyse the events of the Scottish rent strikes of 1915 and their aftermath. The latter, when analysing women’s struggles for better housing conditions, identifies the increasing prominence of a domestic ‘politics of the kitchen that:

… was in turn based upon an informal politics of everyday life, where direct action continued to act as a lynchpin between older ideas of the preindustrial moral economy of justice, fairness and equality and ideas of reciprocity which historians now link to the operation of the welfare state in Britain. (Hughes and Wright, Citation2018: 22)

Today we are similarly facing a social-reproductive crisis. As Bhattacharya (Citation2017) points out, the attack on labour unionism carried out after capitalism’s neoliberal counter-reform was met by an attack on key areas of social reproduction. The material and emotional deprivation caused by financialised capitalism and austerity has been recently framed as a care crisis (Dowling Citation2021), which is actually another way to name “the social-reproductive contradictions of financialized capitalism” (Amaia Citation2014; Fraser Citation2017). Capitalism’s need to constantly accumulate sits in stark contradiction with the reproductive needs of workers and the sustainability of their lives, thereby jeopardising capitalism’s own survival (Fraser Citation2017). We argue that rent overburden as a form of exploitation, evictions for rental non-payment, displacements, and the broader emergence of the “rent question” Europe is facing (Soederberg Citation2018) must be framed as an onslaught against social reproduction.

The concept of the “residential rent relation” developed by Byrne presents how rent, as a socio-economic relation, is articulated through the antagonism between landlords and tenants, that is, between accumulation and social reproduction (2020a: 14). Housing is thus being targeted through the reprivatisation of social reproduction, exemplified by the privatisation and dismantling of policies favouring the collective provision of housing. Risks are being individualised, and the most exposed are women, racialised people, and the working class (Roberts Citation2013). This has become even more evident after the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak, and in particular during the various lockdowns, in which inequalities in the ability to cope with the lockdown and protect oneself from the virus were primarily based on socio-economic status and ethnicity. We also saw how women, again, bore with the increased care-work burden (Dowling Citation2021). Moreover, amid the adoption of the #StayHome policy internationally, housing emerged as a critical infrastructure of care, where one’s life is protected against the virus (Byrne Citation2020b). Several reflections in opinion-analysis pieces after the COVID-19 outbreak stressed housing as a key terrain of social reproduction, which was being antagonised by the rentier drive of landlords’ thirst for accumulation (Cavallero and Gago Citation2020; Madden Citation2020; Vincze Citation2020).

The sudden decline in productive activity and the resulting drop in wage levels began to translate into economic reverberations in households, many of which could not face rent payments. The collective response to the aggravated social-reproductive crisis was organised in the form of grass-roots rent strikes around the globe, among other forms of mobilisation. Calls for rent strikes were reported in Spain, Portugal, the UK, Italy, the US, Australia and Brazil, amongst other countries mapped by the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project (cf. AEMP Citation2020). By consciously stopping rent payments and calling for rent cancellation, rent strikes involved at least two interrelated dynamics. On the one hand, rent strikes were a mechanism to secure care infrastructures by collectively protecting the home in the face of evictions and maintaining available resources (such as household income or savings) for food and other basic goods. On the other hand, by acknowledging that tenants are also workers and wage earners (Soederberg Citation2021) and seeking to cancel rents, the rent strike was simultaneously a strike against debt, that is, against future labour. In this sense, the rent strike was a tactic to break with individual suffering by making collective demands and restoring networks of solidarity and mutual aid.

In other words, the aim of the rent strike was to restore class confidence, reinsert cultures of solidarity, and curate a sense of continuity and class memory, all of which are elements that, following Bhattacharya (Citation2017), had been erased by capital’s attack on social reproduction. As workers’ economic and political struggles in the workplace (for higher wages, less working hours, more social benefits) seek to advance workers’ own personal development against capitalism’s thirst to increase surplus-value via exploitation, so do workers’ struggles at home seek to protect their reproductive and living space against the landlords’ desire to increase profits through rent extraction. Both are “filaments of class solidarity”, forged inside or outside of the workplace, that seek to “increase the ‘share of civilization’ for all workers” (Bhattacharya Citation2017: 139).

Conclusion

Rent strikes have been the most powerful organising tool the tenant movement has historically used to fight back against landlords. We have employed the metaphor of the repertoire to describe the rent strike as a distinctive tactic of collective action available to tenants in the pursuit of shared interests through housing struggle. The concept of class composition as developed by Autonomist Marxism has been used to explain the rent strike as a negative contentious action that creates class as a relation through ongoing struggle in the housing field, that is, the sphere of social reproduction. By activating the boundary of the tenant–landlord relationship, it is the enduring housing struggle itself that creates the tenant subject.

The rent strikes that occurred at the outset of the 20th century overlap like a palimpsest, a shared script rewritten time and time again. We have only focused our historical analysis of the rent strike on the first three decades of the last century, since they constitute the most convulsive cycle of contentious tenant action in recent memory. Yet, the history of modern rent strikes remains to be written in its entirety. Historical analysis of rent strikes has led us to understand them from the perspective of constituent materialism: tenant struggles prefigure the changing legal environment that protects their right to housing through rent controls, the improvement of housing conditions, investment in public housing and so on. We have analysed the formalisation and legalisation of certain types of rent withholding and the institutionalisation of collective bargaining mechanisms in some jurisdictions as the authority’s response to rent strikes. Although rent withholding is not a widespread political right, it is a tactic of resistance which often parallels the labour movement and the history of labour strikes. Both rent and labour strikes are enacted as an opposition to the liberal freedom of contract doctrine, which is a relation of forces favourable to landlords and employers through labour precarity and residential conditions. Both forms of struggle, in the sphere of production and social reproduction, seek to increase “the share of civilisation” of the working class.

The distinctive character of the rent strike is that it delves into the political nature of residential rent relationships, which have emerged in the present as one of the most acute expressions of oppression. Under financialised capitalism, global cities have become playgrounds of real estate speculation and demonstrate, as an increasing body of literature is showing, the consequences of rent overburden, evictions and insecure tenancy. The other side of the coin is the increasing economic yields that landlords extract from private-rental housing markets. We have conceived of the rent strike as a contentious collective action against this residential oppression through the lens of SRT. The theoretical tenets of SRT are essential to analysing the empirical manifestations of rent strikes embedded in the broader dynamics of the rentier capitalist economy. Rent strikes therefore emerge as a crucial collective praxis in the face of a social reproductive crisis that is expressed, among other things, by the housing deprivation and residential alienation generated by private housing markets. This crisis, which has also been called a “care crisis”, has been exposed more acutely after the COVID-19 outbreak. The spontaneous international rent withholding that took place during the first lockdown period of the pandemic was a political act of residential sovereignty, which also revealed the centrality of residence and housing as key structures of collective care. Research on this recent wave of rent strikes is yet to be developed.

Analysing housing struggles and the antagonism underpinning them is critical to understanding the care and social reproductive crisis of late capitalism that we are immersed in. If reproductive work – the work required to produce the labour-power that sustains capitalist relations of production – is the ground zero for revolutionary practice, as Silvia Federici put it, rent strikes are an example of a revolution at point zero.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 The work of Risager (Citation2021) is an attempt to analyse a rent strike through the lens of Italian Autonomism by employing the concept of class composition. The author aims to contribute to the reorganisation of the urban working class through a study case of tenants’ struggles against financialised gentrification in a working-class neighbourhood in Hamilton, Ontario.

2 Data for the European states has been retrieved from the TENLAW project country reports (coordinated by the University of Bremen). Available at: https://www.uni-bremen.de/jura/tenlaw-tenancy-law-and-housing-policy-in-multi-level-europe/reports/reports [Accessed on: 19/02/2022, 19:47h GMT+1].

References

- AEMP. (2020). COVID-19 global housing protection legislation & housing justice action [Map]. https://antievictionmappingproject.github.io/covid-19-map/#close

- Álvaro, T. (2018). La revuelta de las mujeres. Barcelona 1918 [The women's revolt. Barcelona 1918]. El Lokal. https://ellokal.org/portfolio-item/la-revuelta-de-las-mujeres-barcelona-1918-de-toni-alvaro-col-histories-del-raval/

- Amaia, P. -O. (2014). Subversión feminista de la economía. Aportes para un debate sobre el conflicto capital-vida [The feminist subversion of economics. Contributions to the debate over the capital-life conflict]. Traficantes de sueños.

- Baer, J. A. (1993). Tenant mobilization and the 1907 rent strike in Buenos Aires. The Americas. 49(3), 343–368.

- Banik-Schweitzer, R. (1990). Vienna. In Housing the workers 1850–1914. A comparative perspective. Bloomsbury Academic Collections.

- Bhattacharya, T. (Ed.). (2017). Social reproduction theory. Remapping class, recentering oppression. Pluto Press.

- Bradley, Q. (1997). The Leeds rent strike of 1914: A reappraisal of the radical history of the tenants’ movement. Housing Studies HNC Research Project.

- Byrne, M. (2020a). Towards a political economy of the private rental sector. Critical Housing Analysis, 7(1), 103–113. https://doi.org/10.13060/23362839.2020.7.1.507

- Byrne, M. (2020b). Stay home: Reflections on the meaning of home and the Covid-19 pandemic. Irish Journal of Sociology, 28(3), 351–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0791603520941423

- Castells, M. (1974). Movimientos sociales urbanos [Urban social movements]. Siglo XXI.

- Castro, D. S. (1990). “El sainete porteño” and Argentine reality: The tenant strike of 1907. Rocky Mountain Review of Language & Literature, 44(1), 55–68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1347058

- Cavallero, L., & Gago, V. (2020, June 26). La batalla por la propiedad en clave feminista [The struggle for property in a feminist register]. El Salto Diario. https://www.elsaltodiario.com/el-rumor-de-las-multitudes/la-batalla-por-la-propiedad-en-clave-feminista

- Currie, P. (2018). ‘A Wondrous Spectacle’. Protest class and femininity in the 1915 rent strikes. In N. Gray (Ed.), Rent and its discontents: A century of housing struggles (pp. 3-16). Rowman & Littlefield International Ltd.

- Dowling, E. (2021). The care crisis. What caused it and how can we end it? Verso.

- Dyer, C. (1968). A redistribution of incomes in fifteenth-century England? Past & Present, 39(39), 11–33.

- Ealham, C. (2005). Class, culture and conflict in Barcelona 1898–1937. Routledge.

- Federici, S. (2004). Caliban and the witch: Women, the body and primitive accumulation. Autonomedia.

- Federici, S. (2012a). Revolution at point zero. Houswork, reproduction and feminist struggle. PM Press.

- Federici, S. (2012b). Women, land struggles, and globalization: An international perspective (2004). In Revolution at Point Zero. Housework, reproduction and feminist struggle. PM Press.

- Ferguson, S. (2020). Women and work. Feminism, work and social reproduction (1st ed.). Pluto Press.

- Fogelson, R. M. (2013). The great rent wars. New York, 1917–1929. Yale University Press.

- Forsell, H. (2003). ‘Paying the rent’ A long-term perspective on changes in an everyday pattern, Stockholm 1850–1939 with a comparative European outlook. Journal of Urban History, 30(1), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144203258341

- Forsell, H. (2006). Property, tenancy, and urban growth in Stockholm and Berlin, 1860–1920. Ashgate.

- Fraser, N. (2017). Crisis of Care? On the Social-Reproductive Contradictions of Contemporary Capitalism. In T. Bhattacharya (Ed.), Social reproduction theory. Remapping class, recentering oppression. Penguin Press.

- González-Guzmán, J., & Sabaté Muriel, I. (2020, June 22). Cien años de lucha por la bajada de los alquileres: El Decreto de 1920 [One hundred years of struggle for lower rents: The decree of 1920]. El Salto. https://www.elsaltodiario.com/memoria-historica/cien-anos-lucha-bajada-de-los-alquileres-el-decreto-1920

- Gray, N. (Ed.). (2018). Rent and its discontents: A century of housing struggles. Rowman & Littlefield International.

- Gyáni, G. (1990). Budapest. In Housing the workers 1850–1914. Bloomsbury Academic Collections.

- Hardt, M., & Virno, P. (1996). Radical thought in Italy: A potential politics. University of Minnesota Press.

- Harvey, D. (1976). Labor, capital, and class struggle around the built environment in advanced capitalist societies. Politics & Society, 6(3), 265–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/003232927600600301

- Hughes, A., & Wright, V. (2018). What did the rent strikers do next? Women and ‘The Politics of the Kitchen’ in the interwar Scotland. In N. Gray (Ed.), Rent and its discontents: A century of housing struggles. Rowman & Littlefield International, Ltd.

- Kemeny, J. (2003). Housing and social theory. Taylor and Francis. https://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=178524

- Lawson, R. (1983). Origins and evolution of a social movement strategy: The rent strike in New York City, 1904–1980. Urban Affairs Quarterly, 18(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/004208168301800306

- Lewis, R. (1976). The historical development of labour law. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 14(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8543.1976.tb00032.x

- Madden, D. (2020). Housing and the crisis of social reproduction. Architecture - e-Flux. https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/housing/333718/housing-and-the-crisis-of-social-reproduction/

- Madden, D., & Marcuse, P. (2016). In defense of housing. The politics of crisis. Verso.

- Magri, S. (1986). Le mouvement des locataires a Paris et dans sa banlieue, 1919–1925. 137, 55–76.

- Marx, K. (1976). Capital. A critique of political economy (B. Fowkes, Trans.; Vol. 1). Penguin Press.

- McAdam, D., Tarrow, S., & Tilly, C. (2001). Dynamics of contention. Cambridge University Press.

- Melling, J. (1983). Rent strikes. People’s struggle for housing in West Scotland 1890–1916. Polygon Books.

- Negri, A. (1999). Insurgencies. Constituent power and the modern state. University of Minnesota Press.

- Negri, A. (2018). From the factory to the metropolis. Essays volume 2. Polity Press.

- Pascal, B. (1995). Pensées and other writings. Oxford University Press.

- Ramos Vázquez, I. (2020). Capítulo 1. Revolución liberal y trabajo. In La formación del derecho obrero en el Reino Unido, Francia y España antes de la Primera Guerra Mundial. Thompson Reuters Aranzadi.

- Ribera-Almandoz, O. (2019). Searching for autonomy and prefiguration. Resisting the crisis of social reproduction through housing and health care struggles in Spain and the UK [Doctoral dissertation, Universitat Pompeu Fabra]. https://www.tdx.cat/bitstream/handle/10803/668176/tora.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Risager, B. S. (2021). Financialized gentrification and class composition in the post-industrial city: A rent strike against a real estate investment trust in Hamilton, Ontario. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 45(2), 282–302.

- Roberts, A. (2013). Financing social reproduction: The gendered relations of debt and mortgage finance in twenty-first-century America. New Political Economy, 18(1), 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2012.662951

- Rolf, H. (2021). Tenant militancy in Gothenburg as a historical example. Radical Housing Journal, 1(3), 20.

- Soederberg, S. (2018). The rental housing question: Exploitation, eviction and erasures. Geoforum, 89, 114–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.01.007

- Soederberg, S. (2021). Urban displacements: Governing surplus and survival in global capitalism. Routledge.

- Tarrow, S. (1993). Cycles of collective action: Between moments of madness and the repertoire of contention. Social Science History, 17(2), 281. https://doi.org/10.2307/1171283

- Tilly, C. (1986). The contentious French: Four centuries of popular struggle. Harvard University Press.

- Tilly, C., & Tarrow, S. (2015). Contentious politics (2nd Edition). Oxford University Press.

- Tronti, M. (2019). Capital and workers. Verso.

- Vincze, E. (2020, October 6). Housing as a field of social reproduction and struggle for housing justice in Romania—Transnational social strike platform. https://www.transnational-strike.info/2020/10/06/housing-as-a-field-of-social-reproduction-and-struggle-for-housing-justice-in-romania/

- Virno, P. (2013). Saggio sulla negazione. Per una antropologia linguistica [Essay on denial: For a linguistic anthropology]. Bollati Boringhieri.

- Virno, P., (2021). Sobre la impotencia. La vida en la era de su parálisis frenética [On powerlessness: Life in an era of frenetic paralysis. Tercero Incluido, Traficantes de Sueños & Tinta Limón.

- Wolf, D. D. (2019). Two windows: The tenants of the De Freyne rent strike 1901–1903 (Publication No. 13861866). [Doctoral dissertation, Drew University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Wood, A., & Baer, J. (2006). Strength in numbers: Urban rent strikes and political transformation in the Americas, 1904–1925. Journal of Urban History, 32(6), 862–884.

- Wood, E. M. (2002). The origin of capitalism: A longer view (New ed.). Verso.

- Wright, S. (2002). Storming heaven: Class composition and struggle in Italian Autonomist Marxism. In Genre (Vol. 35, Issue 1). Pluto Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/00166928-35-1-176

- Yujnovsky, I. (2004). Vida cotidiana y participación política: «la marcha de las escobas» en la huelga de inquilinos, Buenos Aires, 1907 [Daily life and political participation: “The march of the brooms” in the tenant strike, Buenos Aires, 1907]. Feminismo/s, 3, 117–134. https://doi.org/10.14198/fem.2004.3.08

- Zolberg, A. R. (1972). Moments of madness. Politics & Society, 2(2), 183–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/003232927200200203