Abstract

Although many recognize the importance of addressing the spiritual domain in palliative care, empirically grounded interventions designed to alleviate spiritual needs for patients in palliative care are remarkably scarce. In this paper we argue that the development of such interventions for chaplains is important in order to improve spiritual care in a (post)secular and religiously plural context. We therefore propose an interfaith chaplain-led spiritual care intervention for home-based palliative care that addresses patients’ spiritual needs. The intervention is based on elements of spiritual care interventions that have been investigated among other populations. Three important characteristics of the proposed intervention are (1) life review; (2) materiality, ritual and embodiment; and (3) imagination. The aim of this intervention is to improve palliative patients’ spiritual wellbeing. It is anticipated that such a structured intervention could assist in improving spiritual care in palliative care.

Introduction

In the coming decades, an increasing number of people will suffer from progressive, life-threatening diseases, such as organ failure, incurable cancer and dementia (World Health Organization, Citation2017, Citation2018a, Citation2019). Besides an immense societal impact, these diseases have a major individual impact on patients’ quality of life—not only affecting a patient’s physical, social and psychological wellbeing, but also his or her existential or spiritual wellbeing. A progressive disease may confront patients and their relatives with existential and spiritual concerns, that include the following: loss of meaning or purpose in life, a sense of hopelessness, isolation, fear of dying (Boston et al., Citation2011), and wanting to find answers to questions such as: “Where do I fit in? What have I done to deserve this?” (Murray et al., Citation2004, p. 41). Experiences of existential and spiritual suffering can lead to an existential reorientation or revaluation of the life story (Anbeek, Citation2017; Post et al., Citation2020; Van Knippenberg, Citation2018). Such a reorientation can be characterized as a rewriting of the life story in search for meaning and connectedness as a response to the disruptive experience of vulnerability. People’s story telling about living with serious and progressive illness may lead to self-change or discovery of meaning when the storytellers have listeners who honor and nurture their stories and suffering (Frank, Citation2007).

Spiritual care is an important and intrinsic part of palliative care and is recognized as such by the World Health Organization (Citation2018b) which states that palliative care aims to improve patients’ quality of life by alleviating problems of physical, psychosocial and spiritual nature. In the Netherlands, palliative care is provided for people who live with a serious and life-limiting disease. In a widely accepted perspective on health, the spiritual or existential dimension is identified as one of the six main dimensions of promoting and maintaining health (Huber, Citation2014; Huber et al., Citation2011). Also, practical guidelines for health care professionals in palliative care stress the importance of addressing the spiritual domain (IKNL, Citation2018). Various studies demonstrate positive associations of spiritual care and patients’ quality of life (Gijsberts et al., Citation2019). Research shows that spiritual wellbeing is associated with a strengthening of quality of life for patients with a chronic illness (Cohen et al., Citation1996; Puchalski et al., Citation2014). However, despite growing recognition of the importance of spiritual care in palliative care, spiritual care continues to be the most underdeveloped dimension of palliative care (Gijsberts et al., Citation2019; Selman et al., Citation2014) and spiritual needs of patients with a life-threatening illness often remain unmet (Koper et al., Citation2019).

Although patients may express the need to talk about spirituality and the end of life with their health care providers, many care workers such as physicians and nurses struggle to provide spiritual care (Koper et al., Citation2019; Sinclair & Chochinov, Citation2012). The provision of spiritual care is hampered by institutional elements such as staff shortage, a high workload, a lack of training in addressing the spiritual domain, and personal or cultural elements like considering spirituality a personal matter or feeling inadequate to address patients’ spirituality due to religious differences (Koper et al., Citation2019). When spiritual issues are insufficiently addressed, this may induce spiritual distress (Murray et al., Citation2004). As professionals in spiritual care, chaplains provide support, guidance, and advice regarding meaning, worldview, and spirituality (VGVZ, 2015). These professionals are ideally suited to provide spiritual care in palliative care. However, the structural contribution of chaplains in palliative care remains relatively small (Damen & Leget, Citation2017). In this article, we focus explicitly on the care chaplains can provide in the palliative phase.

Chaplaincy in palliative care faces several challenges. First, the religious and spiritual landscape in Western societies has changed incredibly in the last decades because of processes such as secularization, globalization, and pluralization (Woodhead et al., Citation2016). This diversity implies that chaplains must meet the existential and spiritual needs of a diverse patient population. Meanwhile, it is not always clear how chaplains, traditionally representing religious or humanist affiliations, can achieve this (Ganzevoort et al., Citation2014). Chaplains can encounter dilemmas in balancing their own personal denominational identity with the need to provide care to people from diverse religious backgrounds. Second, chaplains are available in healthcare facilities but barely in home-based care (IKNL, Citation2018). In the Dutch home-based care context, for instance, referrals to chaplains are still rare (Koper et al., Citation2019) and the access to home-based chaplaincy is only recently developing (Agora, Citation2019). Hence, most chaplains are new in this field and population of patients. Consequently, chaplains are required to adjust their practice in order to address the spiritual needs of this diverse patient population and to become recognized as contributors to the care provision in this new field. Third, there is a lack of research on the effectiveness of chaplaincy practices in health care, especially with regard to methodologies and validated interventions, while there is a need for evidence about the contributions and value of chaplaincy (Damen & Leget, Citation2017; Gijsberts et al., Citation2019; Handzo et al., Citation2014; Kruizinga et al., Citation2018; Smit, Citation2015).

Against the background of these three challenges, we present in this article a narrative and interfaith spiritual care intervention that will be used to investigate how chaplaincy can effectively contribute to spiritual wellbeing of patients in palliative home-based care. First, we explore what might be the specific spiritual needs in the palliative phase using theories about meaning making and spiritual coping. Then we substantiate our claim of a need for a new chaplain-led intervention, building on various promising and effective interventions of spiritual care that have been developed in recent years. After that, we present the elements of our new intervention for chaplaincy to improve the spiritual wellbeing of patients in palliative, home-based care. These elements include: (1) life review; (2) materiality, ritual and embodiment; and (3) imagination. The focus is primarily on an intervention for the Dutch context. In the discussion we address the question of its applicability in a broader context.

Background

Understanding spiritual needs in the palliative phase

When people are confronted with a life-threatening illness, increasing suffering, deteriorating physical possibilities and the nearing of death, this may evoke existential and spiritual needs. Both terms are disputed and there is a lot of debate on the relationship between the concepts of existential and spiritual issues (Boston et al., Citation2011; Sinclair & Chochinov, Citation2012). In this article, we follow the European definition of spirituality that reads: “Spirituality is the dynamic dimension of human life that relates to the way persons (individual and community) experience, express and/or seek meaning, purpose and transcendence, and the way they connect to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, to the significant and/or the sacred” (Nolan et al., Citation2011, p. 88).Footnote1 This definition emphasizes the multifaceted character of the spiritual field and argues that ‘spirituality’ comprises existential issues (questions concerning, for example, meaning, suffering, reconciliation and hope), value-based concerns (which means those dimensions that are of great importance to people) and religious principles and considerations (beliefs and behaviors). Hence, in this article we approach spiritual issues to encompass existential, value-based and religious issues. Patients faced with a life-threatening illness may struggle with spiritual needs such as feelings of fear, despair, loneliness, loss of hope, loss of meaning and fear of dying (Murray et al., Citation2004). Spiritual needs may lead to existential suffering or spiritual distress, but also provide space for discovering new meaning, reorientation and transformation (Post et al., Citation2020).

Park (Citation2013) developed the “Meaning Making Model” in which she explains how profound experiences can initiate a meaning making process. In this model, “global meaning” and “situational meaning” are distinguished. Global meaning concerns someone’s comprehensive meaning system including one’s beliefs and goals. When people are confronted with existential experiences, a discrepancy can arise between one’s global meaning and the meaning that they assign to this specific experience (situational meaning). In the palliative phase, patients’ existential experiences may show discrepancies between attributed meaning regarding a specific situation (such as the approaching end of one’s life) and the person’s comprehensive meaning system. This calls for a reorientation of the global and situational meaning, so that either—or both—can be adjusted and the discrepancy eliminated.

Questions concerning meaning occur when people experience contingencies in their lives. According to Van Knippenberg (Citation2018), these questions can be thought of as junctions in the life story. People tell their life story in order to make sense of the different experiences in life. By telling, they bring order and coherence in their life story, and they evaluate and appropriate their life (Linde, Citation1993; Post et al., Citation2020). This allows people to understand the present and past, to provide orientation for the future, and to assign meaning and purpose to life (McAdams, Citation2001; Post et al., Citation2020). Van Knippenberg refers to three story lines: (a) the time line, which revolves around the question of who someone is in relation to who he/she was in the past and will be in the future; (b) the space line, which is about the position someone takes with regard to his/her social environment and the context in which someone lives; and (c) the transcendence line, which is characterized by the question: why am I here, and where do I belong?

Janoff-Bulman (Citation1992) argues, based on research into traumatized patients, that a healthy life story is characterized by three key assumptions, which seem to be reflected in the three story lines by Van Knippenberg (Citation2018): the belief (1) that the person in question is of value (positive self-evaluation); (2) that others (people, but also nature or God) are helpful and benevolent to the person in question; and (3) that life has a meaningful and righteous coherence and is therefore reliable. An experience such as living with a life-threatening disease may harm and disrupt these key assumptions in life. Feelings of fear, doubt, lack of self-esteem and worthlessness—related to the often-increasing dependence on others—suggest a violation of the first key assumption. Relational problems, feelings of loneliness, guilt, not belonging and not being of value to others relate to the second key assumption. Questions such as “Why does this happen to me?” (Murray et al., Citation2004, p. 41) suggest that the meaningful coherence of life is under pressure. These key assumptions in life also relate to our understanding of spirituality including connectedness with the self, others and with something greater than ourselves (Nolan et al., Citation2011).

The exploration of the life story along these lines gives us direction for understanding palliative patients’ spiritual needs and search for meaning and connectedness. Another important concept related to palliative patients’ spiritual needs and contributing to spiritual wellbeing is hope (Olsman et al., Citation2015). According to Van Knippenberg (Citation2018), hope is directed to the future and helps to reconcile with the present situation in the here and now. Hope can direct in times of balancing between change and continuity. In the palliative phase, patients may deal with questions concerning hope versus despair. Erikson (Citation1950) assumes people pass through different stages during life in which the final stage focuses on the question of acceptance of life. He distinguishes two opposites in this stage: ego-integrity (a positive acceptance or reconciliation with one’s own life) versus despair. The feelings of doubt, fear and despair which may occur as spiritual needs in the palliative phase (Murray et al., Citation2004) could indicate difficulty in balancing these two opposites. A narrative approach, to which we turn next, enables people to obtain self-affirmation and self-acceptance (Post et al., Citation2020) and hence achieve ego-integrity and hope instead of despair (Pinquart & Forstmeier, Citation2012).

The need for a new spiritual narrative chaplain-led intervention for palliative care

Chaplains can provide spiritual care to address palliative patients’ spiritual needs and improve their spiritual wellbeing. In order to improve spiritual care, research into the effects of chaplaincy, and the development of clear goals and validated methodologies for chaplains is essential in the current context of the profession (Damen et al., Citation2020; Handzo et al., Citation2014; Swinton, Citation2013). However, the spiritual care chaplains provide has sporadically been evaluated in standardized interventions (Steinhauser et al., Citation2016) and research examining effects of spiritual care interventions for palliative patients is scarce (Gijsberts et al., Citation2019). In the last couple of years, various promising and effective interventions for spiritual care have been developed.Footnote2 These interventions are based on a narrative paradigm: they focus on working with the life story, investigating what is of ultimate concern in this life story and promoting dialogue about existential questions from different philosophical or religious points of view.

Two interventions are specifically developed for chaplains in the Netherlands in which working with life review methods is central: the “Life InSight Application” (LISA) study (Kruizinga et al., Citation2013) and a spiritual life review intervention (Post et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, other studies and interventions provide building blocks for a narrative intervention for chaplain-led spiritual care, such as (narratively) working with hope (Olsman et al., Citation2015), positive revaluation (Körver, Citation2013), the art of dying (Leget, Citation2017) and rituals (Körver, Citation2016). All these models and approaches are based on the importance of stories and life review for developing life-orientation and directed at meaning-making and connectedness in life.

However, no chaplain-led intervention has been developed for home-based palliative care. One of the mentioned interventions is intended for groups rather than individuals (Post et al., Citation2020), and the LISA intervention is developed for the context of hospitals (Kruizinga et al., Citation2019; Kruizinga et al., Citation2013). Therefore, we propose an interfaith, narrative chaplain-led intervention for palliative patients living at home aimed to improve spiritual wellbeing. The proposed intervention is specifically intended for individual consultations between chaplains and palliative patients in the home setting. Results from previous research suggest that a short intervention does not provide enough time and space to achieve a lasting effect (Kruizinga et al., Citation2019). In contrast, an intervention consisting of six to eight meetings seems to be more effective in the long term (Post et al., Citation2020). Therefore, we chose to develop an intervention consisting of six meetings. We will collect qualitative and longitudinal quantitative data in order to investigate the effect of the intervention on patients’ spiritual wellbeing.Footnote3 We will now outline the structure of the proposed intervention and then elaborate on three main characteristics, which are based on a combination of elements from existing interventions and models associated with spiritual wellbeing. We assume these characteristics to contribute to improving palliative patients’ spiritual wellbeing.

Description of the intervention: “In dialogue with your life story”

Structure of the intervention

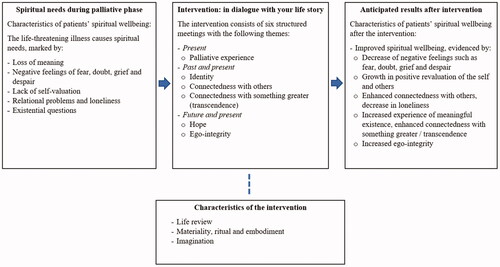

We developed a structured intervention consisting of six weekly meetings. We will now briefly elaborate on the proposed intervention and the themes that are central in each meeting. In the first meeting—in addition to an introduction with each other and the intervention—the present situation of the patient will be explored. This meeting is about the way in which the present situation—of the palliative experience and possible spiritual needs—is experienced and the meaning one assigns to this experience and current situation (“situational meaning”).

In the second, third and fourth meeting the way the patient used to live life and give meaning to life—his/her global meaning (Park, Citation2013)—will be discussed. These meetings are structured by three core themes that connect with the storylines as distinguished by Van Knippenberg (Citation2018), the basic assumptions as distinguished by Janoff-Bulman (Citation1992), and the connectedness on three levels spoken of in the definition of spirituality (Nolan et al., Citation2011): identity and connection with the self (meeting 2); connection with others (meeting 3); and connection with something greater than ourselves, the search for a meaningful coherence or transcendence (meeting 4). During each of these meetings, narratives about the past are linked to the present and the relationship between global and situational meaning is elaborated upon. In the fourth meeting, the attention is shifted from present-past to present-future.

The fifth and sixth meeting focus on the question of ego-integrity and hope versus despair (Erikson, Citation1950; Olsman et al., Citation2015). These themes will be explored by speaking about hope and fear towards the future (meeting 5) and gratitude and regret towards life and the self (meeting 6). A schematic overview of the proposed intervention can be found in .

Life review

In the proposed intervention, chaplains will follow a structured protocol in order to stimulate the patient to tell about his or her life now, and in the past and future. As argued, patients in the palliative phase may be confronted with spiritual needs and a loss of meaning. Having a conversation about vulnerability and suffering creates space to speak about what is of value, what gives strength and where new paths emerge (Anbeek, Citation2017). People construct stories about themselves and their lives in order to understand reality and themselves. By telling one’s life story, new insights can be obtained that may lead to a renewed self-understanding (Tromp & Ganzevoort, Citation2009) and discovery of meaning in life (Alma & Anbeek, Citation2013).

Life review is a specific form of a narrative intervention, in which people evaluatively look back on their lives (Keall et al., Citation2015; Sools et al., Citation2015; Westerhof & Bohlmeijer, Citation2014). Life review encourages people to organize memories, look for meaning in the events of their lives and evaluate and integrate the different life experiences in a meaningful coherence. This can lead to reconciliation with the self and attaching (new) meaning to life. Research indicates that storytelling improves people’s wellbeing and that life review, as well as storytelling about one’s future, contributes to the strengthening of meaning making (Sools et al., Citation2015). The process of recalling and sharing memories called reminiscence helps people to prepare and accept mortality, solve current problems by remembering coping strategies in the past, and construct or interpret one’s identity by reflecting on the past (Westerhof & Bohlmeijer, Citation2014). Chaplains use the structured intervention to encourage patients to share their stories and memories.

Materiality, ritual and embodiment

In the proposed intervention, we focus on the embodied, every day and lived experiences of people’s spirituality in which ritual and artefacts often play an important role. The material and ritual dimension of religion and spirituality is often downplayed while in fact it is an inseparable aspect of religion and spirituality (Alma & Anbeek, Citation2013; Geertz, Citation1973; Meyer & Houtman, Citation2012). Texts, pictures and other material forms that involve bodies and objects appear as the visible, living and enabling conditions of religion or spirituality. According to Körver (Citation2016), rituals may give rise to experiences of consolation and connectedness, regardless of specific religious traditions. Moreover, rituals create space where a new reality may be found. In this new space, the imagining of alternative possibilities can help people in disruptive experiences of fragility to face reality with new hope. In the proposed intervention, embodied experiences and the focus on artefacts and ritual is central.

Imagination

The process of imagination is woven into the proposed intervention. When people search for meaning and spiritual orientation, they are guided by their imaginations of different realities (Alma, Citation2008; Körver, Citation2016). This process of imagination is important in experiences of fragility because it helps to build a bridge between what is and what could be. Imagination is a force that enables people to realize possibilities for change and it supports this transformation. Imagination is closely connected to the future, as the future is the domain of the possible. Sools et al. (Citation2015) show that future imagination encourages an active process of future-oriented action, that seems to correlate with a strengthening of wellbeing, meaning making and positive emotions. In the proposed intervention, chaplains encourage palliative patients to imagine new possibilities and act accordingly.

Discussion and conclusion

The aim of this article was to investigate how chaplaincy can contribute to the spiritual wellbeing of patients in palliative home-based care. We showed how spiritual needs play a role in the palliative phase and argued that the development of a systematic, narrative intervention can assist chaplains in addressing these spiritual needs and contributing to the spiritual wellbeing of patients. We argued a new intervention is necessary, mainly because no chaplain-led intervention has been developed for the palliative home-based context before in the Netherlands. We developed the proposed intervention by combining and structuring relevant elements from previous research. The proposed intervention provides a guide for chaplains to address spiritual needs that can arise in the palliative phase and contribute to patients’ spiritual wellbeing.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the proposed intervention is that it is based on themes and competencies that chaplains are familiar with, which means that chaplains may easily work with the method and incorporate it in their regular patient care. Working narratively and ritually is inherent to chaplaincy of diverse backgrounds and is central in the proposed intervention. The intervention provides a framework for chaplains to address spiritual needs. This framework is no rigid frame that is forced upon the patient. Rather, it creates possibilities for the patient to, with support and encouragement from the chaplain, discuss his/her personal life story, existential questions and experiences and the ways he/she attaches meaning to these questions and experiences in a structured and in-depth manner. This also relates to another strength of this study: the interfaith character of the proposed intervention. The intervention offers patients from diverse backgrounds the opportunity to include those aspects that are relevant for them in their current situation. On the caregiver’s side, the care provided is not stripped of the chaplain’s denominational identity, but this identity is not the most important feature as the main focus is on the patient’s story. We therefore assume chaplains and patients from a diversity of backgrounds can benefit from this intervention.

Meanwhile, there are several limitations to this intervention as well. First, although we assume the proposed intervention contributes to patients’ spiritual wellbeing, we have not yet tested the effects of the intervention empirically. Therefore, we do not yet know whether the proposed intervention will have the impact we presume. To investigate the impact of the structured intervention on patients’ spiritual wellbeing, a study will be conducted that combines longitudinal survey data among patients with qualitative data from interviews with and reflection notes by patients and chaplains (for the design of this study, see Liefbroer et al., Citation2021). A second limitation is that the impact and success of the intervention in part depends on the skills of the chaplains involved in the study. Therefore, the intervention is designed for experienced chaplains, who will be trained to work with this particular intervention. A third limitation is that the proposed intervention is based on building blocks from previous research mainly conducted in a secularized, and European—primarily Dutch—context. The development of such an intervention raises questions about the applicability of the intervention in other, less secularized, contexts. Moreover, it raises the question whether a more universal model is feasible and desirable, or that interventions need to be developed as specific strategies fitting the context and target group. Future research may scrutinize whether and how the proposed elements and characteristics of the intervention fit to and function in other contexts.

Relevance and implications for practice

The proposed intervention provides a useful frame for chaplains practicing spiritual provision in palliative care, for several reasons. First, the systematic nature of this intervention supports the need for more outcome-oriented and evidence-based chaplaincy. Second, it supports chaplains to articulate what their contribution and value is, which is a necessity for the development of the chaplaincy profession as such. Third, the intervention connects the spiritual needs that can arise in the palliative phase with a systematic methodology for chaplains to respond to these spiritual needs and work towards the goal of strengthening patients’ spiritual wellbeing. Working with such a structured intervention may support chaplains to be increasingly recognized by other care workers as equal professionals in the health care process. Although working with clear methodologies and with an articulated aim is still in its’ infancy in the field of chaplaincy, we believe that the development of evidence-based interventions for chaplains will improve spiritual care provision and will be a fruitful step for further developing the chaplaincy profession.

Ethical approval statement

This research does not fall within the scope of the Dutch law on medical-scientific research involving human subjects (WMO). This has been confirmed by the research ethic committee of Brabant (identification code: NW2020-05). In addition, the ethical review board of Tilburg School of Catholic Theology, Tilburg University approved this research (identification code: ERB-TST # 2020/6). Participants in the research are asked to sign an informed consent form before participating.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Christa Anbeek, Renske Kruizinga and Erik Olsman for their valuable contributions in the development of the intervention.

Disclosure statement

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This definition is based on the North-American consensus definition of spirituality (Puchalski et al., Citation2009) but adjusted for the European context.

2 A narrative approach is often used in interventions for spiritual care, however these spiritual care interventions are not exclusively developed for chaplains but often for other health care professionals. According to a recent systematic review examining spiritual interventions addressing existential needs on quality of life of cancer patients, one out of fourteen interventions was performed by spiritual healers, others by psychologists/psychiatrists, oncology professionals or general health care professionals (Kruizinga et al., Citation2016). IKNL (Citation2018) recommends three assessments tools for health care providers to explore palliative patients’ spiritual needs, namely the questions in the Mount Vernon Cancer Network assessment tool (Mount Vernon Cancer Network, Citation2007), the Ars Moriendi (Art of Dying) model (Leget, Citation2017) and the FICA Spiritual History Tool (Borneman et al., Citation2010). In the Netherlands, various models are developed primarily for health care professionals. The intervention called “Precious Memories” is developed for volunteers (Westerhof et al., Citation2018) and another intervention is developed for psychologists (Van der Spek et al., Citation2017). The dialogue model is developed for a group of participants without supervisor (Anbeek, Citation2017) and the Life Story Book Method is developed for nurses and volunteers (Ganzevoort & Bouwer, Citation2007; Tromp, Citation2011).

3 For detailed information about the research design of this intervention study see Liefbroer et al. (Citation2021).

References

- Agora (2019). Factsheet 2 - Subsidieregeling geestelijke verzorging thuis. Retrieved from https://vgvz.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/190513-Factsheet-2-GV-in-de-thuissituatie.pdf.

- Alma, H. A. (2008). Self-development as a spiritual process: The role of empathy and imagination in finding spiritual orientation. Pastoral Psychology, 57(1–2), 59–63. doi:10.1007/s11089-008-0168-4

- Alma, H. A., & Anbeek, C. (2013). Worldviewing competence for narrative interreligious dialogue: A Humanist contribution to spiritual care. In D. S. Schipani (Ed.), multifaith views in spiritual care (pp. 149–166). Kitchener, Ontario: Pandorapress.

- Anbeek, C. (2017). World-viewing dialogues on precarious life: The urgency of a new existential, spiritual, and ethical language in the search for meaning in vulnerable life. Essays in the Philosophy of Humanism, 25(2), 171–185. doi:10.1558/eph.33444

- Borneman, T., Ferrell, B., & Puchalski, C. M. (2010). Evaluation of the FICA tool for spiritual assessment. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 40(2), 163–173. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.019

- Boston, P., Bruce, A., & Schreiber, R. (2011). Existential suffering in the palliative care setting: An integrated literature review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 41(3), 604–618. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.05.010

- Cohen, S. R., Mount, B. M., Tomas, J. J., & Mount, L. F. (1996). Existential well‐being is an important determinant of quality of life: Evidence from the McGill quality of life questionnaire. Cancer, 77(3), 576–586. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960201)77:3<576::AID-CNCR22>3.0.CO;2-0

- Damen, A., & Leget, C. (2017). Kennissynthese onderzoek naar geestelijke verzorging in de palliatieve zorg. Den Haag: ZonMW.

- Damen, A., Schuhmann, C., Lensvelt-Mulders, G., & Leget, C. (2020). Research priorities for health care chaplaincy in the netherlands: A Delphi study among Dutch Chaplains. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 26(3), 87–102. doi:10.1080/08854726.2018.1473833

- Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

- Frank, A. W. (2007). Just listening: Narrative and deep illness. In S. Krippner, M. Bova, & L. Gray (Eds.), Healing stories: The use of narrative in counseling and psychotherapy (pp. 21–40). Charlottesville, VA: Puente Publications.

- Ganzevoort, R. R., Ajouaou, M., Van der Braak, A., de Jongh, E., & Minnema, L. (2014). Teaching spiritual care in an interfaith context. Journal for the Academic Study of Religion, 27(2), 178–197. doi:10.1558/jasr.v27i2.178

- Ganzevoort, R. R., & Bouwer, J. (2007). Life story methods and care for the elderly. An empirical research project in practical theology. In H. G. Zieberts & F. Schweitzer (Eds.), Dreaming the land. Theologies of resistance and hope (pp. 140–151). Münster: LIT-Verlag.

- Geertz, C. (1973). Religion as a cultural system. In C. Geertz (Ed.), The Interpretation of Cultures. Selected essays (pp. 87–125). New York: Basic Books.

- Gijsberts, M. H. E., Liefbroer, A. I., Otten, R., & Olsman, E. (2019). Spiritual care in palliative care: A systematic review of the recent European literature. Medical Sciences, 7(2), 25. doi:10.3390/medsci7020025

- Handzo, G. F., Cobb, M., Holmes, C., Kelly, E., & Sinclair, S. (2014). Outcomes for professional health care chaplaincy: An international call to action. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 20(2), 43–53. doi:10.1080/08854726.2014.902713

- Huber, M. (2014). Towards a new, dynamic concept of health: Its operationalisation and use in public health and healthcare and in evaluating health effects of food. Maastricht: Maastricht University.

- Huber, M., Knottnerus, J. A., Green, L., van der Horst, H., Jadad, A. R., Kromhout, D., … Smid, H. (2011). How should we define health? BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 343, d4163. doi:10.1136/bmj.d4163

- IKNL (2018). Existential and spiritual aspect of palliative care: National guideline. Retrieved from https://www.pallialine.nl/uploaded/docs/Zingeving/Existential_and_spiritual_aspects_of_palliative_care_totaal_incl_ref.pdf?u=1SzaCi

- Janoff-Bulman, R. (1992). Shattered assumptions. Towards a new psychology of trauma. New York: Free Press.

- Keall, R. M., Clayton, J. M., & Butow, P. N. (2015). Therapeutic life review in palliative care: A systematic review of quantitative evaluations. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 49(4), 747–761. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.08.015

- Koper, I., Pasman, H. R. W., Schweitzer, B. P., Kuin, A., & Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B. D. (2019). Spiritual care at the end of life in the primary care setting: Experiences from spiritual caregivers - a mixed methods study. BMC Palliative Care, 18(1), 98. doi:10.1186/s12904-019-0484-8

- Körver, J. (2013). Spirituele coping bij longkankerpatiënten: Tilburg University. doi:10.34894/7QRRHM

- Körver, J. (2016). Ritual as a house with many mansions. Inspirations from cultural anthropology for interreligious cooperation. Jaarboek voor liturgieonderzoek, 32, 105–123.

- Kruizinga, R., Hartog, I. D., Jacobs, M., Daams, J. G., Scherer-Rath, M., Schilderman, J. B. A. M., … Van Laarhoven, H. W. M. (2016). The effect of spiritual interventions addressing existential themes using a narrative approach on quality of life of cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psycho-oncology, 25(3), 253–265. doi:10.1002/pon.3910

- Kruizinga, R., Scherer-Rath, M., Schilderman, H. J. B. A. M., Puchalski, C. M., & Van Laarhoven, H. H. W. M. (2018). Toward a fully fledged integration of spiritual care and medical care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 55(3), 1035–1040. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.11.015

- Kruizinga, R., Scherer-Rath, M., Schilderman, J. B., Hartog, I. D., Van Der Loos, J. P., Kotzé, H. P., … Van Laarhoven, H. W. (2019). An assisted structured reflection on life events and life goals in advanced cancer patients: Outcomes of a randomized controlled trial (Life InSight Application (LISA) study). Palliative Medicine, 33(2), 221–231. doi:10.1177/0269216318816005

- Kruizinga, R., Scherer-Rath, M., Schilderman, J. B., Sprangers, M. A., & Van Laarhoven, H. W. (2013). The life in sight application study (LISA): Design of a randomized controlled trial to assess the role of an assisted structured reflection on life events and ultimate life goals to improve quality of life of cancer patients. BMC Cancer, 13, 360. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-13-360

- Leget, C. (2017). Art of living, art of dying. Spiritual care for a good death. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Liefbroer, A. I., Wierstra, I. R., Janssen, D. J. A., Kruizinga, R., Nagel, I., Olsman, E., & Körver, J. W. G. (2021). A spiritual care intervention for chaplains in home-based palliative care: Design of a mixed-methods study investigating effects on patients’ spiritual wellbeing. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 1–14. doi:10.1080/08854726.2021.1894532

- Linde, C. (1993). The creation of coherence in life stories: An overview. In C. Linde (Ed.), Life stories: The creation of coherence (pp. 3–19). New York: Oxford University Press.

- McAdams, D. P. (2001). The psychology of life stories. Review of General Psychology, 5(2), 100–122. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.5.2.100

- Meyer, B., & Houtman, D. (2012). Introduction. Material religion - how things matter. In D. Houtman & B. Meyer (Eds.), Things. Religion and the question of materiality (pp. 1–23). New York: Fordham University Press.

- Mount Vernon Cancer Network (2007). Spiritual support steering group. Final report on spiritual support. Stevenage, UK: Mount Vernon Cancer Network.

- Murray, S. A., Kendall, M., Boyd, K., Worth, A., & Benton, T. F. (2004). Exploring the spiritual needs of people dying of lung cancer or heart failure: A prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers. Palliative Medicine, 18(1), 39–45. doi:10.1191/0269216304pm837oa

- Nolan, S., Saltmarsh, P., & Leget, C. (2011). Spiritual care in palliative care: Working towards an EAPC Task Force. European Journal of Palliative Care, 18(2), 86–89.

- Olsman, E., Leget, C., & Willems, D. (2015). Palliative care professionals’ evaluations of the feasibility of a hope communication tool: A pilot study. Progress in Palliative Care, 23(6), 321–325. doi:10.1179/1743291X15Y.0000000003

- Park, C. L. (2013). The meaning making model: A framework for understanding meaning, spirituality, and stress-related growth in health psychology. European Health Psychologist, 15(2), 40–47.

- Pinquart, M., & Forstmeier, S. (2012). Effects of reminiscence interventions on psychosocial outcomes: A meta-analysis. Aging & Mental Health, 16(5), 541–558. doi:10.1080/13607863.2011.651434

- Post, L., Ganzevoort, R. R., & Verdonck-de Leeuw, I. M. (2020). Transcending the suffering in cancer: Impact of a spiritual life review intervention on spiritual re-evaluation, spiritual growth and psycho-spiritual wellbeing. Religions, 11(3), 142. doi:10.3390/rel11030142

- Puchalski, C., Ferrell, B., Virani, R., Otis-Green, S., Baird, P., Bull, J., … Sulmasy, D. (2009). Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: The report of the Consensus Conference. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 12(10), 885–904. doi:10.1089/jpm.2009.0142

- Puchalski, C., Vitillo, R., Hull, S. K., & Reller, N. (2014). Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: Reaching national and international consensus. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 17(6), 642–656. doi:10.1089/jpm.2014.9427

- Selman, L., Young, T., Vermandere, M., Stirling, I., & Leget, C. (2014). Research priorities in spiritual care: An international survey of palliative care researchers and clinicians. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 48(4), 518–531. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.10.020

- Sinclair, S., & Chochinov, H. M. (2012). Communicating with patients about existential and spiritual issues: SACR-D work. Progress in Palliative Care, 20(2), 72–78. doi:10.1179/1743291X12Y.0000000015

- Smit, J. (2015). Antwoord geven op het leven zelf. Een onderzoek naar de basismethodiek van de geestelijke verzorging. Delft: Eburon.

- Sools, A. M., Tromp, T., & Mooren, J. H. (2015). Mapping letters from the future: Exploring narrative processes of imagining the future. Journal of Health Psychology, 20(3), 350–364. doi:10.1177/1359105314566607

- Steinhauser, K. E., Olsen, A., Johnson, K. S., Sanders, L. L., Olsen, M., Ammarell, N., & Grossoehme, D. (2016). The feasibility and acceptability of a chaplain-led intervention for caregivers of seriously ill patients: A Caregiver Outlook pilot study. Palliative & Supportive Care, 14(5), 456–467. doi:10.1017/S1478951515001248

- Swinton, J. (2013). A question of identity: What does it mean for chaplains to become health care professionals? Health and Social Care Chaplaincy, 6(2), 2–8. doi:10.1558/hscc.v6i2.2

- Tromp, T. (2011). Older adults in search of new stories: Measuring the effects of life review on coherence and integration in autobiographical narratives. In G. Kenyon, E. T. Bohlmeijer, & W. Randall (Eds.), Storying later life: Issues, investigations, and interventions in narrative gerontology (pp. 252–272). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Tromp, T., & Ganzevoort, R. R. (2009). Narrative competence and the meaning of life. Measuring the quality of life stories in a project on care for the elderly. In L. J. Francis, M. Robbins, & J. Astley (Eds.), Empirical theology in texts and tables: Qualitative, quantitative and comparative perspectives (Vol. 17, pp. 197–216). London: Brill.

- van der Spek, N., Vos, J., van Uden-Kraan, C. F., Breitbart, W., Cuijpers, P., Holtmaat, K., … Verdonck-de Leeuw, I. M. (2017). Efficacy of meaning-centered group psychotherapy for cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Psychological Medicine, 47(11), 1990–2001. doi:10.1017/S0033291717000447

- Van Knippenberg, T. (2018). Existentiële zielzorg. Tussen naam en identiteit (2nd ed.). Kampen: Van Warven.

- Vereniging van Geestelijk VerZorgers (2015). Beroepsstandaard geestelijk verzorger 2015. Retrieved from https://vgvz.nl/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Beroepsstandaard-2015.pdf.

- Westerhof, G. J., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2014). Celebrating fifty years of research and applications in reminiscence and life review: State of the art and new directions. Journal of Aging Studies, 29, 107–114. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2014.02.003

- Westerhof, G. J., Korte, J., Eshuis, S., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2018). Precious memories: A randomized controlled trial on the effects of an autobiographical memory intervention delivered by trained volunteers in residential care homes. Aging & Mental Health, 22(11), 1494–1501. doi:10.1080/13607863.2017.1376311

- Woodhead, L., Partridge, C., & Kawanami, H. (Eds.). (2016). Religions in the modern world: Traditions and transformations (3rd ed.). London: Routledge.

- World Health Organization (2017). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-(copd)

- World Health Organization (2018a). Cancer. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer.

- World Health Organization (2018b). Palliative care. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care.

- World Health Organization (2019). Dementia. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia.