ABSTRACT

In inclusive education, learning and support assistants (LSAs) play an increasingly prominent role in supporting students with disabilities in regular classrooms. Previous research has identified various factors that influence the implementation of inclusive education, such as collaboration and the self-efficacy beliefs amongst the involved professions. The present cross-sectional study examined the self-efficacy beliefs of 89 Styrian LSAs in interaction with their age, qualification, specialist knowledge and quality of collaboration with teachers. Our findings reveal that Styrian LSAs show a high amount of self-efficacy beliefs. Correlations confirm that their age, knowledge about special education, assessment of feeling qualified based on completed training and the estimated quality of teacher collaboration relate significantly to their self-efficacy beliefs. Further analyses demonstrate that respondents who had completed a degree in social work have the highest sense of self-efficacy and are thus feel best qualified for supporting children with disabilities due to their previous training. In line with earlier research, these findings strengthen the claim for LSAs to receive training that would impact their self-efficacy beliefs, which, in the long run, could increase the likelihood of inclusive educational practices being successfully implemented.

Introduction

Since the ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN-CRPD) (United Nations Citation2006), educational systems around the world have tried to implement and enhance inclusive thinking and practice. According to Ainscow, Booth and Dyson (Citation2006), an inclusive educational system allows all children and young people equal participation in education, it respects and recognises the diversity of all students and values their different abilities and competences. In addition, an inclusive educational system recognises the capacities of all students within a classroom and encourages them according to their individual abilities (Feyerer Citation2012). In order to successfully implement inclusive education according to the UN-CRPD, adequate support measures must be provided to meet the individual needs of the students (United Nations Citation2006).

Children with disabilities and special educational needs (SEN), in particular, rely on these (additional) support measures. According to Austrian law, a child has SEN if he or she is unable to follow the regular curriculum without special support due to a physical or psychological disability that lasts for a period of more than six months (Rechtsinformationssystem des Bundes Citation1985). In this context, learning and support assistants (LSAs) – also called paraprofessionals (Giangreco, Suter, and Doyle Citation2010), teacher assistants (Giangreco, Doyle, and Suter Citation2014) or teaching assistants (Webster et al. Citation2010) – have become increasingly important for inclusive education. In this paper, we use the term learning and support assistants (LSAs) because in Austrian schools, these personnel play a vital role in engaging students with SEN in every aspect of compulsory and post-compulsory education, including supporting their learning and social inclusion as well as fostering peer interactions and relationships.

Currently, LSAs are a pivotal resource for the implementation of inclusive education. Without the support of LSAs, many children would not be able to attend regular schools (Laubner, Lindmeier, and Lübeck Citation2017). Nevertheless, research has been critical of LSAs’ roles in schools. Scholars have shown that with the increasing support from LSAs, teacher-to-student interactions have decreased, and it is LSAs – not teachers – who interact with students with SEN, taking on the role of primary teacher in the process (Broer, Doyle, and Giangreco Citation2005). As Webster et al. (Citation2010) noted, this has led to students with high levels of need often being supported by the least qualified staff instead of well-trained teachers. This could lead to LSAs contributing to the separation of students with SEN rather than their inclusion (Webster et al. Citation2010). To avoid such developments, a close and content-oriented collaboration between LSAs and teachers is crucial.

Multi-professional collaboration towards inclusive education

Collaboration between different professions is not only important for students with and without disabilities (Meyer Citation2017), but it is also socially supportive for the involved professions. It enables them to bring in a wide range of expertise, which has positive effects on the quality of work and students’ academic progress (Meyer, Nonte, and Willems Citation2017).

Henn et al. (Citation2019) describe a successful collaboration as a trusting cooperation between teachers and LSAs that requires mutual exchange, joint formulation of objectives and shared achievement of goals. Further studies have identified various factors for collaboration between LSAs and teachers to be effective, including supporting each other through sharing information about students, possessing knowledge about the corresponding subject, having clear but flexible responsibilities and treating each other with respect (Devecchi and Rouse Citation2010).

Scholars have also identified factors that can obstruct the successful collaboration between teachers and LSAs, including the conditions of employment and LSAs’ related status in school hierarchies (Beck and Maykus Citation2016). In Austria, LSAs are responsible for supporting a specific child for a certain amount of state-approved hours. But these hours do not include time for exchanging information and joint planning of lessons with teachers (Meyer Citation2017). If LSAs participate in meetings with teachers, for example, these are not considered as working time to be compensated for (Henn et al. Citation2019). Compounding this problem, LSAs are employed by external social service providers and are therefore not part of the school community. This could induce restricted collaboration and involvement of LSAs in school activities. Another factor that can obstruct successful collaboration is the perception that LSAs, due to the absence of qualification requirements in Austria, are unskilled workers (Lübeck Citation2017). Beside of contextual factors, individual attitudes, such as people’s willingness for interdisciplinary cooperation and openness towards other involved professions (Henn et al. Citation2019), as well as self-efficacy beliefs of the involved professions have been recognised as factors that influence effective collaboration in multi-professional teams (Meyer Citation2017).

Self-efficacy of the involved professions implementing inclusive education

Self-efficacy has been defined as the amount of confidence one has in one’s capabilities (Bandura Citation1993). According to Bandura (Citation1977, Citation1994), major sources for enhancing self-efficacy beliefs are verbal persuasion and physiological states, performance accomplishment based on personal mastery experiences and vicarious experience provided by social models, i.e. seeing others with similar abilities handle challenging situations successfully.

Differentiating this concept, other scholars have divided self-efficacy into two types: general self-efficacy and specific self-efficacy (Schwarzer and Jerusalem Citation2002). While general self-efficacy covers all areas of life, specific self-efficacy relates to specific areas of competence. In the context of education, teachers’ self-efficacy is a strong influencing factor on the success of inclusion in school. Teachers with high self-efficacy beliefs for inclusive education are confident that students with SEN can be effectively taught in their classroom. Moreover, these teachers remain persistent with low-achieving students and use better teaching strategies that allow them to learn more effectively (Sharma, Loreman, and Forlin Citation2012).

In light of these findings, we assume that the self-efficacy of LSAs might be even more important for the success of inclusive education than that of teachers. LSAs decide intentionally and with well-founded reasons to work with children with SEN, while this may not be the case for teachers. LSAs’ interest in and passion for inclusive education might be, compared with teachers, more inherent to their understanding of their role within the classroom and for their motivation to work in this field. Moreover, LSAs might have a greater enthusiasm and commitment for supporting students with SEN and implementing inclusive practices.

Most research has focused on teachers’ self-efficacy for inclusive education, yet LSA’s self-efficacy has been overlooked (Meyer Citation2017). Since both professions work in the same field with similar tasks, however, we assume that similar factors that influence teachers’ self-efficacy also influence the self-efficacy of LSAs.

Factors associated with self-efficacy for inclusive education

Previous research has identified various factors related to teachers’ self-efficacy for inclusive education. Pre-service teachers enrolled in an intensive training in disabilities and inclusion as well as those with extensive experience with students with SEN had significantly higher self-efficacy scores than the group with minimal training and experience (Leyser, Zeiger, and Romi Citation2011). Other factors also correlated with their self-efficacy for inclusion, including frequency and intensity of contact with people with disabilities (r = .09), the number of semesters of study (r = −.19) and prospective teachers’ motivation for working in inclusive education (r = .38) (Schwab, Hellmich, and Görel Citation2017). Moreover, Hellmich and Görel (Citation2014) found significant relationships between experienced primary teachers’ self-efficacy and their attitudes towards inclusion (r = .53) as well as between teachers’ self-efficacy and their motivation to deal with inclusive education (r = .49). Additional results from a structural equation model revealed teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs as the main predictor to explain differences in teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education (.42).

As previously mentioned, collaboration in multi-professional teams is also related to the self-efficacy beliefs of the involved professions. Guo et al. (Citation2011) found a significant and moderate correlation between teachers’ self-efficacy and teacher collaboration (r = .39), which they defined as teachers’ reported levels of collaboration and what type of collaboration this was. Teacher collaboration was a significant predictor of teachers’ self-efficacy (β = .40; p = .02), which explained 15% of variance.

Moreover, focusing on multi-professional collaboration in inclusive schools, Meyer (Citation2017) reported similar results for LSAs as for teachers, in particular significant correlations between LSAs’ self-efficacy, role security and job satisfaction. In addition, a significant but small correlation was found between LSAs’ self-efficacy and the quality of collaboration with teachers (r = .27).

Research aims

To our knowledge, the self-efficacy of LSAs has yet to be investigated. Due to this, our cross-sectional study investigated the self-efficacy of Styrian LSAs for inclusive education and examined correlations between self-efficacy, qualifications, knowledge about disabilities and inclusion and the amount of experience with people with SEN (Leyser, Zeiger, and Romi Citation2011; Schwab, Hellmich, and Görel Citation2017). The quality of collaboration in multi-professional teams – which depends on self-efficacy beliefs of those involved – is important for the successful implementation of inclusive education (Walk and Beck Citation2016). Due to its significance, our study investigated collaboration between LSAs and teachers. The following research questions were addressed:

To what extent do Styrian LSAs experience their professional activity as efficient?

Which factors are related to Styrian LSAs’ self-efficacy regarding inclusive education? Based on previous findings, expected influential factors are the qualification and professional knowledge of the LSAs, their experience with students with SEN and the quality of cooperation with teachers.

Method

The research described here was part of a larger project investigating LSAs’ contribution to the successful implementation of inclusive education in the Austrian province of Styria. Therefore, a cross-sectional online survey was conducted. The questionnaire contained socio-demographic information (e.g. sex, age, highest educational level, but no personal information in order to guarantee anonymity), information regarding the current job situation (e.g. number and disabilities of supported children, work setting, etc.) and included scales to estimate LSAs’ level of knowledge and skills regarding special education, additional training needs, job-related tasks and influencing factors for successful inclusive education. This article only reports the instruments and variables relevant for this study.

Instruments

Self-efficacy for inclusive education

LSAs’ self-efficacy for inclusive education was assessed with an adapted version of the German-language Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practices (TEIP) (Feyerer et al. Citation2016). For the present study, only 10 out of 18 items were used to assess LSAs’ self-efficacy regarding inclusive practices. Specifically, one of the included items was ‘Wenn ich bei der Arbeit mit einem Problem konfrontiert werde, habe ich meist mehrere Ideen, wie ich damit fertig werde’ (‘When confronted with a problem at work, I usually have several ideas of how to cope with it’). The remaining eight items were specifically related to teachers and therefore not included in the adapted scale. For the adapted version used in this survey, a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 = ‘strongly agree’ was used. The adapted version of the TEIP has a Cronbachs α = .91.

LSAs’ professional knowledge

In order to investigate LSAs’ evaluation of their own knowledge and skills level about special needs education, items were used from the Council for Exceptional Children (Citation2004)standards for paraeducators (Council for Exceptional Children Citation2004) adapted by Carter et al. (Citation2009). These CEC standards represent basic standards of knowledge LSAs are expected to possess when beginning their job. The original scale consists of 15 items including statements regarding respondents’ knowledge about special education foundations, development and characteristics of learners, instructional strategies, learning environments and social interactions, professional and ethical practices and collaboration. In this scale, LSAs were asked to rate each item along three different dimensions (level of knowledge, need for additional training and previous training) on a five-point Likert scale (Carter et al. Citation2009). For the present study, a translated and adapted version of these 15 knowledge-related items was used. For example, one item was ‘Ziele der Programme für Schüler/innen mit Beeinträchtigung’ (‘goals of support programme services for children with special needs’). LSAs were asked to rate their level of knowledge along three dimensions (level of knowledge, need for additional training and previous training) on a three-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = ‘no knowledge’ to 3 = ‘substantial knowledge’. The translated and adapted version of the CEC standards has a Cronbachs α = .90.

Collaboration in multi-professional teams

To assess the quality of collaboration between LSAs and teachers, an adapted version of the Questionnaire on Teamwork (FAT) was used (Kauffeld Citation2004). This questionnaire consists of two subscales: the first subscale includes 12 person-oriented items (α = .74) and the second subscale contains 11 structure-oriented items (α = .86). Our study used 23 of the 24 items (the item for social desirability was not included). One item on this questionnaire was ‘Die Teammitglieder kennen ihre Aufgaben’ (‘The team members understand their jobs’). The rating scale system for both subscales were reversed and ranged from 1 = ‘never applies’ to 4 = ‘always applies’. This adapted version of the FAT has a Cronbachs α = .88.

Pilot testing

In order to pilot the questionnaire, a pre-test with five LSAs was carried out. Based on the results of this test, minor adjustments were made.

Data collection and procedure

The data for our study were collected in spring 2018. Initially, 16 social service providers for people with disabilities in Styria were contacted by email and given a short introduction to the study. If social service providers did not respond within two weeks, they were contacted by phone. Of the 16 contacted organisations, 11 agreed to participate in our study. Subsequently, a hyperlink to the online survey was sent to those who agreed to participate, and they were asked to forward it to LSAs within their organisation.

In 2017, the Styrian state government estimated that there were 550 LSAs supporting students with disabilities in the state (Rossacher Citation2017). Based on this number, we estimate that we reached 16% of the Styrian LSAs with this survey.

Sample

Data were collected from 89 Styrian LSAs who were employed by social service providers for people with disabilities. 87.6% of the respondents were woman and 12.4% were men. The mean age of the sample was 35 years (SD = 10.52 years), 50.6% of the participants were between 20 and 30 years, 18% were between 31 and 40 years, 15.7% were between 41 and 49 years and 15.7% were ≥50 years.

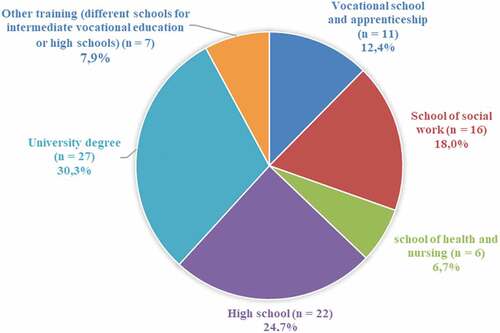

Regarding respondents’ educational levels, 32.9% of the LSAs possessed a university degree, 26.8% a high school degree, 26.8% completed an intermediate vocational school (of which 19.5% completed a school of social work, e.g. in the field of family support or with disabled persons, and 7.3% completed a school of health and nursing) and further 13.4% completed a vocational school and apprenticeship. 7.9% completed other types of training, e.g. different schools for intermediate vocational education or high schools ().

Of the 89 respondents, 85.4% supported children and young people with SEN in regular schools and the others supported children and young people with SEN in both regular schools and in extracurricular settings (afternoon support in schools). Regarding the types of schools where LSAs support students with SEN, 56.2% of the respondents worked in primary schools, 37.1% at lower secondary level (36.0% in new secondary school and 1.1% at the lower level of the ‘Gymnasium’, the academic secondary school), 3.4% at upper secondary level and 3.4% in special schools (for more information about the Austrian Education System: Bundesministerium für Bildung Citation2017).

Most of the participants (40.4%) had been working as LSAs for less than a year (n = 36), 16.9% had worked in the field for one year (n = 15), 19.1% for two years (n = 17), 16.9% for three years (n = 15) and 6.7% for four or more years (n = 6).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the statistic software SPSS 23. First, Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests were conducted to determine the distribution of the data. The results showed that the data were not normally distributed. Hence, Spearman correlations were calculated. Furthermore, a Kruskal-Wallis-test was conducted to analyse differences between LSAs working in primary schools and secondary schools regarding their self-efficacy, professional knowledge and collaboration. Another Kruskal-Wallis-test was used to identify differences in LSAs’ feeling of being qualified due to their training and their highest educational level. Finally, a Kruskal-Wallis-test was used to investigate differences between LSAs’ self-efficacy beliefs and their highest level of education.

Results

Self-efficacy of Styrian LSAs

Concerning the self-efficacy of LSAs, results showed an average specific self-efficacy for inclusive education of M = 4.14 (SD = .69) on a five-point Likert scale. According to these findings, it can be assumed that Styrian LSAs have a high self-efficacy for inclusive education and they perceive their actions as effective.

Potential differences between LSAs working in primary and secondary education regarding their self-efficacy for inclusion were investigated by a non-parametrical Kruskal-Wallis test. Due to the small sample size, we merged LSAs working in lower (n = 33) and upper secondary education (n = 3). Results showed that there were no significant differences between the two groups of LSAs (H1 = .13; p = .72).

Qualifications of Styrian LSAs

In the survey, LSAs were asked to assess their knowledge about special education based on the CEC standards. The average estimation was M = 2.31 (SD = .42) on a three-point Likert scale. In total, 79.8% of the respondents evaluated their knowledge about special education as ‘good’. In the further calculations regarding LSAs’ highest educational level, respondents who completed other training (n = 7) were not included. These participants completed different types of training and therefore the results provide little validity.

also reveals that 93.8% of the respondents, who completed a school of social work as their highest educational level assessed their knowledge level, on average, as ‘most comprehensive’. Since the frequencies in some cells were less than 5, chi-square distribution was too deviant and could not be interpreted. However, according to Cramer’s-V = .36 (p = .03), there was a medium association between the variables (highest educational level and knowledge level about special education).

Table 1. LSAs’ knowledge about special education and their highest level of education.

Besides the CEC standards, LSAs were asked to assess to what extent they feel qualified due to their training. The mean was recorded at M = 4.10 (SD = .92) on a five-point Likert scale and implies that most of the respondents feel well or very well qualified due to their completed training (76.4%).

Results of a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis-test revealed that LSAs’ assessment of feeling qualified due to their training was significantly affected by their highest educational level (H4 = 9.72; p = .045). Pairwise comparisons with adjusted p-values showed significant differences between LSAs’ assessments of feeling qualified when respondents had a high school degree or when completed a school of social work as their highest educational level (p = .03; r = .33). A comparison of the mean ranks demonstrated that respondents with a high school degree scored lowest and those who completed a school of social work achieved the highest mean ranks regarding their assessment of feeling qualified due to their training.

Differences between LSAs’ self-efficacy for inclusion and their highest educational level were also investigated by a non-parametrical Kruskal-Wallis test. Results showed a significant main effect for LSAs’ self-efficacy and their level of education (H4 = 9.91; p = .04). Pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences between LSAs’ self-efficacy when respondents had a university degree or when completed a school of social work as their highest educational level (p = .01; r = .28). A comparison of the mean ranks revealed that LSAs with a university degree showed the lowest means. In contrast, LSAs, who completed a school of health and nursing followed by those who completed a school of social work showed the highest means (). These results indicate that LSAs with a university degree experience their actions as less self-effective and those with a training in health and nursing and for social work perceive their actions as most self-effective.

Table 2. Means and standard deviations of LSAs’ self-efficacy according to their highest educational level.

Factors associated with LSAs’ self-efficacy

Spearman correlations of factors associated with LSAs’ self-efficacy showed that ‘experiences in supporting students with SEN’ was not significantly related to LSAs’ self-efficacy. In contrast, the age of the participants correlated significantly with their self-efficacy, but only to a minor extent (r = .28; p = .01). This finding indicates the older LSAs are, the stronger their perceived self-efficacy beliefs. In addition, LSAs’ knowledge level about special education (r = .62; p = .00) and their assessment of feeling qualified due to their completed training were significantly related to their self-efficacy (r = .45; p = .00). Based on these findings, it can be assumed that LSAs with a comprehensive level of knowledge about special education and those who feel best qualified due to their completed training have a higher sense of self-efficacy.

Collaboration between LSAs and teachers

LSAs rated the quality of collaboration with teachers as moderate (M = 2.85; SD = .47). Additionally, results from the Spearman correlations showed a significant positive and moderate correlation coefficient between the collaboration with teachers and LSAs’ self-efficacy for inclusive education (r = .46; p = .00). This result suggests a reciprocal influence between self-efficacy and quality of collaboration. On the one hand, the stronger the perceived self-efficacy of LSAs, the better the collaboration with teachers. On the other, it also implies that the better the collaboration between LSAs and teachers, the stronger the perceived self-efficacy of LSAs. Finally, results revealed a significant positive correlation (r = .43; p = .00) between LSAs’ knowledge level about special education and the perceived collaboration with teachers, which represents a medium association between the variables. This finding indicates the more comprehensive LSAs’ knowledge about special education, the better the quality of the collaboration with teachers is (or vice versa).

Results from the Spearman correlations are summarised in , which lists the correlation coefficients (r) and significances for all included variables.

Table 3. Summary of non-parametric correlations of LSAs’ self-efficacy and associated factors.

Discussion

Previous research has identified various factors that influence the implementation of inclusive education, including collaboration and self-efficacy beliefs of the people involved (Walk and Beck Citation2016). Teachers’ self-efficacy has been extensively investigated and identified as an important factor for inclusive education (Sharma, Loreman, and Forlin Citation2012). Yet research on LSAs’ self-efficacy has remained sparse, although LSAs’ self-efficacy might be even more important for successful inclusive education than that of teachers. Perhaps because the intent of LSAs is to work with students with SEN, this could affect their intrinsic motivation and passion for inclusive education. For this reason, these professionals might also be more committed to supporting students with SEN and for implementing inclusive practices.

Our study attempted to investigate the self-efficacy beliefs of Styrian LSAs for inclusive education and the relationship to their qualification and professional knowledge, their experience with students with SEN and the collaboration with teachers in inclusive education. Results of the presented cross-sectional study revealed that Styrian LSAs have a high sense of self-efficacy for inclusive education and they perceive their actions as effective. Although differences between LSAs working in primary and secondary education might be expected, we did not find any in relation to their self-efficacy, professional knowledge or the quality of collaboration with teachers. However, positive and medium to high correlations were found between LSAs’ self-efficacy beliefs and their age, their professional knowledge and their perceived feeling of being qualified by previous training.

Taking into consideration that in Austria as well as in many other countries (e.g. UK, Germany, etc.) there are no official qualification requirements for LSAs, a detailed consideration of our data indicated that LSAs, who completed a school of social work as highest educational level evaluated their knowledge about special education as most comprehensive. In addition, this group scored nearly highest in their self-efficacy beliefs for inclusive education. These results correspond to the findings that training in disabilities and inclusion leads to a higher score of self-efficacy beliefs (Leyser, Zeiger, and Romi Citation2011). They also suggest that the school of social work qualifies for supporting children with disabilities in regular schools due to imparting knowledge about pedagogical and medical-nursing skills on a basic level. In addition, this training also includes a mandatory internship with expert guidance. Our findings indicate that these LSAs had numerous possibilities to master challenging situations during their training, which led to a higher sense of self-efficacy beliefs. Furthermore, we presume that graduates may have had vicarious experiences during their internship seeing their mentors handle challenging situations successfully. Hence, our results correspond with Bandura’s social cognitive theory, which contends that performance accomplishments and vicarious experiences have a relevant impact on self-efficacy beliefs (Bandura Citation1977).

Further findings from our study demonstrate that LSAs’ self-efficacy was related to the quality of collaboration with teachers. These results are in line with previous research (Meyer Citation2017). This can be interpreted in two ways: The better the cooperation with teachers, the stronger LSAs’ self-efficacy, or, perhaps, the stronger the perceived self-efficacy of LSAs, the better the collaboration with teachers. These findings confirm the mutual interdependence between self-efficacy and multi-professional collaboration and strengthen the assumption that both factors are crucial for successful inclusive education (Guo et al. Citation2011).

In accordance with previous research, other factors, such as the conditions of employment (Beck and Maykus Citation2016) or sufficient time for exchange and joint planning between the involved professionals (Meyer Citation2017), are significantly influenced by professional knowledge and corresponding training in special education and inclusion (Leyser, Zeiger, and Romi Citation2011). Our results emphasise the need for LSAs to undergo specific ‘LSA training’ as an official qualification requirement. Although the law states that educational activities are not part of LSAs’ duties, scholars have demonstrated that LSAs’ tasks, in reality, range from nursing to educational activities (Carter et al. Citation2009). Based on the connection between low qualifications of LSAs and the slow learning progress of students with SEN (Webster et al. Citation2010), training is urgently needed.

This training should include basic information about disabilities, pedagogical knowledge, instructional strategies, and methods to support students’ learning and social interactions (Carter et al. Citation2009). It should also offer LSAs possibilities to gain practical experience in working with students with disabilities. Making sure LSAs were qualified in this manner would not only prevent negative impacts on students’ academic progress, but it would also enhance the self-efficacy beliefs of the professions involved (Leyser, Zeiger, and Romi Citation2011). This could also contribute to the successful implementation of inclusive education (Sharma, Loreman, and Forlin Citation2012).

Better qualified LSAs could also have a positive impact on their collaboration with teachers. Qualified LSAs could be able to observe learning processes more accurately and to communicate these observations, interpretations and inferences more precisely. They may even gain a certain expert status through their qualification. In the end, this could enhance mutual understanding between LSAs and teachers, and help establish a true educational partnership between them (Sharples, Webster, and Blatchford Citation2018).

Limitations and implications

The findings of the present study are limited by some methodological constraints and must be interpreted cautiously. One limitation of the study is that the data are based on the assessment of LSAs only. In order to validate the results, additional data, such as teachers’ evaluation regarding the quality of the collaboration with LSAs, would be important. This would allow a comparison between teachers’ and LSAs’ assessment and would provide more detailed information to understand the collaboration process and related strengths and weaknesses.

The sample size of the study is also an important limitation. Although no information about the exact number of LSAs working in Styria could be found, based on the number of students with SEN in inclusive educational settings (2017/2018: 2.455 students with SEN; Statistik Austria Citation2018) it can be assumed that significantly more than 89 LSAs were employed to support students with SEN. Therefore, it could be the case that only a selective sample participated in this survey. This could be the group of LSAs who were satisfied with their current job situation and their involvement in educational and extracurricular activities. This would explain the tendency for the high ratings of their knowledge level, their self-efficacy and feeling qualified due to their training. A larger representative sample would be needed to validate the findings.

For economic reasons and to avoid overloading the questionnaire, LSAs evaluated their knowledge about special education according to the CEC-Standards on a three-point Likert scale (instead of as a five-point Likert scale as in the original version). Although the adapted scale had a Cronbachs α = .90, previous studies have indicated that using scales with a higher number of response categories provide greater options for answers and thus a differentiated assessment for the respondents (Franzen Citation2014). Implementing this would allow a more accurate measurement and more informative results could perhaps be provided.

This study has not examined contextual factors that are known to be associated with LSAs’ support and students’ (poor) educational achievements, including, for example, the limited time available with teachers to prepare lessons (Webster et al. Citation2010), the conditions of LSAs’ employment and their related status in school hierarchy (Beck and Maykus Citation2016), and the understanding of roles and tasks of those involved. Further studies should consider these contextual factors that might also have a relevant impact on self-efficacy beliefs and the quality of multi-professional collaboration.

Finally, it seems necessary to be aware of the limitation of LSAs as an additional resource for students with SEN. Scholars have questioned whether this resource promotes an inclusive school system through enhancing collaborative and inclusive learning or whether it remains an additional measure which leads to the separation rather than the inclusion of children with SEN (Melzer Citation2019). This difficult question cannot yet be answered, as many teachers do not feel sufficiently prepared for supporting children with SEN in their classes without additional resources. Many teachers feel overwhelmed by their duties if they are responsible for so many different students in class. They can be more relaxed and experience more positive aspects of inclusion when they are supported by LSAs (Giangreco and Doyle Citation2007). Although simply adding more special support measures is not the intent of inclusive education, these extra support personnel might be the best possible solution at the moment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Caroline Breyer

Caroline Breyer, Bakk. phil MSc. is a PhD candidate at the Department for Professional Development in Education, University of Graz, Austria. Her research areas are inclusive education of students with special educational needs, assistance services for students with special educational needs in regular schools and the professional development in education.

Katharina Wilfling

Katharina Wilfling, BA MSc. is a graduate of the master programme Inclusive Education at University of Graz, Austria. Her research areas are inclusive education and assistance services for children with special educational needs in regular schools.

Christoph Leitenbauer

Christoph Leitenbauer, BA MSc. are graduates of the master programme Inclusive Education at University of Graz, Austria. His research areas are inclusive education and assistance services for children with special educational needs in regular schools

Barbara Gasteiger-Klicpera

Dr. Barbara Gasteiger-Klicpera is a Professor of Inclusive Education at the University of Graz, Austria. Her research interests are inclusive education, learning disabilities, diversity and health literacy as well as interventions for children with emotional and social difficulties.

References

- Ainscow, M., T. Booth, and A. Dyson. 2006. “Inclusion and the Standards Agenda: Negotiating Policy Pressures in England.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 10 (4–5): 295–308. doi:10.1080/13603110500430633.

- Bandura, A. 1977. “Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change.” Psychological Review 84 (2): 191–215. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191.

- Bandura, A. 1993. “Perceived Self-Efficacy in Cognitive Development and Functioning.” Educational Psychologist 28 (2): 117–148. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep2802_3.

- Bandura, A. 1994. “Self-Efficacy.” In Encyclopedia of Human Behavior. Vol. 4, 4th ed., edited by V. S. Ramachaudran, 71–81. San Diego:Academic Press.

- Beck, A., and S. Maykus. 2016. “Zusammenarbeit, Lehrerkooperation an Inklusiven Grundschulen Unter Dem Gesichtspunkt Der Interprofessionalität. Empirische Befunde Zu Bewertung Und Erfahrung Schulinterner.” [Collaboration, Teacher Cooperation in Inclusive Primary Schools from the Viewpoint of Interprofessionality. Empirical Findings on Evaluation and Experience of Internal School Personnel.] In Inklusive Bildung in Kindertageseinrichtigungen Und Grundschulen: Empirische Befunde Und Implikationen Für Die Praxis [Inclusive Education in Day Care Centers and Primary Schools: Empirical Findings and Implications for Practice], edited by S. Maykus, A. Beck, G. Hensen, A. Lohmann, H. Schinnenburg, M. Walk, E. Werding, and S. Wiedebusch, 146–172. Weinheim Basel: Beltz Juventa.

- Broer, S. M., M. B. Doyle, and M. F. Giangreco. 2005. “Perspectives of Students with Intellectual Disabilities about Their Experiences with Paraprofessional Support.” Exceptional Children 71 (4): 415–430.

- Bundesministerium für Bildung. 2017. “Education in Austria 2016/2017.” https://bildung.bmbwf.gv.at/enfr/school/bw_en/bildungswege2016_eng.pdf?6kdmda

- Carter, E., L. O’Rourke, L. G. Sisco, and D. Pelsue. 2009. “Knowledge, Responsibilities, and Training Needs of Paraprofessionals in Elementary and Secondary Schools.” Remedial and Special Education 30 (6): 344–359. doi:10.1177/0741932508324399.

- Council for Exceptional Children. 2004. “The Council for Exceptional Children Definition of a Well-Prepared Special Eudcation Teacher.” https://www.cec.sped.org/~/media/Files/Policy/CECProfessionalPoliciesandPositions/wellpreparedteacher.pdf

- Devecchi, C., and M. Rouse. 2010. “An Exploration of the Features of Effective Collaboration between Teachers and Teaching Assistants in Secondary Schools.” Support for Learning 25 (2): 91–99. doi:10.1111/(ISSN)1467-9604.

- Feyerer, E. 2012. “Allgemeine Qualitätskriterien Inklusiver Pädagogik Und Didaktik.” [General Quality Criteria of Inclusive Pedagogy and Didactics.] Zeitschrift Für Inklusion 6 (3). https://www.inklusion-online.net/index.php/inklusion-online/article/view/51/51

- Feyerer, E., H. Reibnegger, P. Hecht, C. Niedermaier, C. Soukup-Altrichter, C. Plaimauer, E. Prammer-Selmmler, I. Moser, and I. Bruch. 2016. “SACIE-R/TEIP - Skala Für Einstellungen, Haltungen Und Bedenken Zur Inklusiven Pädagogik/Skala Zu Lehrer/Innenwirksamkeit in Inklusiver Pädagogik.” [SACIE-R/TEIP - Scale for Attitudes and Concerns about Inclusive Education/Scale for Teacher Effectiveness in Inclusive Education.] https://www.psycharchives.org//handle/20.500.12034/467

- Franzen, A. 2014. “Antwortskalen in Standardisierten Befragungen.” [Rating Scales in Standardized Surveys.] In Handbuch Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung [Manual of Methods of Empirical Social Research], edited by N. Baur and J. Blasius, 701–711. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Giangreco, M. F., and M. B. Doyle. 2007. “Teacher Assistants in Inclusive Schools.” In The SAGE Handbook of Special Education, edited by L. Florian, 429–439. London: Sage.

- Giangreco, M. F., M. B. Doyle, and J. C. Suter. 2014. “Teacher Assistants in Inclusive Classrooms.” In The SAGE Handbook of Special Education. Vol. 2, 2nd ed., edited by L. Florian, 691–702. London:Sage Publications .

- Giangreco, M. F., J. C. Suter, and M. B. Doyle. 2010. “Paraprofessionals in Inclusive Schools: A Review of Recent Research.” Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation 20: 41–57. doi:10.1080/10474410903535356.

- Guo, Y., L. M. Justice, B. Sawyer, and V. Tompkins. 2011. “Exploring Factors Related to Preschool Teachers’ Self-Efficacy.” Teaching and Teacher Education 27 (5): 961–968. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2011.03.008.

- Hellmich, F., and G. Görel. 2014. “Erklärungsfaktoren für Einstellungen von Lehrerinnen und Lehrern zum Inklusiven Unterricht in Der Grundschule.” [Explaining Factors for Teachers' Attitudes for Inclusive Education in the Primary School.] Zeitschrift Für Bildungsforschung 4 (3): 227–240. doi:10.1007/s35834-014-0102-z.

- Henn, K., L. Thurn, J. M. Fegert, and U. Ziegenhain. 2019. “‘Man Ist Immer Mehr Oder Weniger Alleinkämpfer’ - Schulbegleitung Als Herausforderung Für Die Interdisziplinäre Kooperation. Eine Qualitative Studie.” [‘You are More or Less Fighting on Your Own‘ – Assistance as Challenge for Interdisciplinary Cooperation. A Qualitative Study.] VHN 2 (88): 114–127.

- Kauffeld, S. 2004. FAT - Fragebogen Zur Arbeit Im Team [QAT – Questionnaire about Teamwork]. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

- Laubner, M., B. Lindmeier, and A. Lübeck. 2017. “Schulbegleitung in Der Inklusiven Schule: Einführung in Das Herausgeberwerk.” [“LSAs in Inclusive Schools: An Introduction to the Editorial Work.] In Schulbegleitung in Der Inklusiven Schule. Grundlagen Und Praxishilfen [LSAs in Inclusive Schools. Basics and Practical Advices], edited by M. Laubner, B. Lindmeier, and A. Lübeck, 7–10. 1st ed. Weinheim Basel: Beltz.

- Leyser, Y., T. Zeiger, and S. Romi. 2011. “Changes in Self-Efficacy of Prospective Special and General Education Teachers: Implication for Inclusive Education.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 58 (3): 241–255. doi:10.1080/1034912X.2011.598397.

- Lübeck, A. 2017. “Außen Vor Und Doch Dabei? Zur Einbindung Der Schulbegleitung Im Schulischen Kollegium.” [Excluded and yet Included? Including LSAs in the School Community.] In Schulbegleitung in Der Inklusiven Schule. Grundlagen Und Praxishilfen [LSAs in Inclusive Schools. Basics and Practical Advices], edited by M. Laubner, B. Lindmeier, and A. Lübeck, 66–73. Weinheim Basel: Beltz.

- Melzer, J. 2019. “Schulassistenz. Motor Oder Bremsklotz Für Eine Inklusive Schulentwicklung?” [Assistance. Engine or Brake for an Inclusive School Development?] Online Journal for Research and Education, no. 11: 1–10.

- Meyer, K. 2017. “Multiprofessionalität in Der Inklusiven Schule: Eine Empirische Studie Zur Kooperation von Lehrkräften Und Schulbegleiter/Innen (Göttinger Schulbegleitungsstudie GötS).” [Multiprofessionality in Inclusive Schools: An Empirical Study on the Cooperation of Teachers and LSAs (Göttinger Study about LSAs).] Göttinger Beiträge Zur Erziehungswissenschaftlichen Forschung 37. doi:10.17875/gup2017-1029.

- Meyer, K., S. Nonte, and A. Willems. 2017. “Mittendrin Und Doch Außen Vor? Eine Empirische Studie Zur Multiprofessionellen Kooperation Aus Der Sicht Von Schulbegleiter/Innen.” [In the Centre of and yet Excluded? an Empirical Study on Multi-professional Cooperation from the Perspective of LSAs.] In Schulbegleitung in Der Inklusiven Schule. Grundlagen Und Praxishilfen [LSAs in Inclusive Schools. Basics and Practical Advices], edited by M. Laubner, B. Lindmeier, and A. Lübeck, 74–89. Weinheim Basel: Beltz.

- Rechtsinformationssystem des Bundes. 1985. Bundesgesetz Über Die Schulpflicht (Schulpflichtgesetz 1985) [Federal Act on Compulsory Education in Austria (Compulsory Education Act 1985)]. Austria. https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=10009576

- Rossacher, T. 2017. “Premiere Für Neuen Stundenplan.” [Premiere for a New Schedule.] https://www.pressreader.com/austria/kleine-zeitung-steiermark/20170526/page/24

- Schwab, S., F. Hellmich, and G. Görel. 2017. “Self-Efficacy of Prospective Austrian and German Primary School Teachers regarding the Implementation of Inclusive Education.” Journal of Research in Reading 17 (3): 205–217. doi:10.1111/1471-3802.12379.

- Schwarzer, R., and M. Jerusalem. 2002. “Das Konzept Der Selbstwirksamkeit.” [The Concept of Self-efficacy.] Zeitschrift Für Pädagogik 44: 28–53.

- Sharma, U., T. Loreman, and C. Forlin. 2012. “Measuring Teacher Efficacy to Implement Inclusive Practices.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 12 (1): 12–21. doi:10.1111/j.1471-3802.2011.01200.x.

- Sharples, J., R. Webster, and P. Blatchford. 2018. Making Best Use of Teaching Assistants. Guidance Report. London: Education Endowment Foundation. https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/Publications/Teaching_Assistants/TA_Guidance_Report_MakingBestUseOfTeachingAssistants-Printable.pdf

- Statistik Austria 2018. “Schülerinnen Und Schüler Mit Sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf 2017/2018.” [Students with Special Educational Needs 2017/2018.] https://www.statistik.at/web_de/statistiken/menschen_und_gesellschaft/bildung/schulen/schulbesuch/029658.html

- United Nations. 2006. “Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Optional Protocol.” http://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf

- Walk, M., and A. Beck. 2016. “‘Die Bereitschaft in Den Köpfen Ist Da’. Einstellungen Und Selbstwirksamkeit von Lehrkräften Auf Dem Weg Zur Inklusiven Schule.” [‘The Willingness in the Minds Is There‘. Attitudes and Self-efficacy of Teachers on the Way to Inclusive Schools.] In Inklusive Bildung in Kindertageseinrichtungen Und Grundschulen: Empirische Befunde Und Implikationen Für Die Praxis [Inclusive Education in Day Care Centers and Primary Schools: Empirical Findings and Implications for Practice], edited by S. Maykus, A. Beck, G. Hensen, A. Lohmann, H. Schinnenburg, M. Walk, E. Werding, and S. Wiedebusch, 209–231. Weinheim Basel: Beltz Juventa.

- Webster, R., P. Blatchford, P. Bassett, P. Brown, C. Martin, and A. Russell. 2010. “Double Standards and First Principles: Framing Teaching Assistant Support for Pupils with Special Educational Needs.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 25 (4): 319–336. doi:10.1080/08856257.2010.513533.