Abstract

Objective

To investigate the correlations between serum antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) and clinicopathological features, induction treatment response, and prognosis of lupus nephritis (LN) patients.

Methods

In this retrospective study, biopsy-proven LN patients from October 2010 to September 2020 were tested for serum ANCA by indirect immunofluorescence and ELISA and were divided into ANCA-positive group and ANCA-negative group. The clinicopathological data of the two groups were analyzed and compared.

Results

Thirty-five of 115 patients (30.43%) were seropositive for ANCA. ANCA-positive patients had significantly higher systemic lupus erythematosus activity index and activity index scores, higher 24-h urinary protein, and lower complement three levels (p = 0.001, 0.028, 0.023, 0.009, respectively). The incidences of oral ulcers, thrombocytopenia, and leukocyturia, and the positive rates of anti-dsDNA antibody and anti-histone antibody were significantly higher in ANCA-positive group (p = 0.006, 0.019, 0.012, 0.001, 0.019, respectively). Class IV LN and fibrinoid necrosis/karyorrhexis were significantly more common in the ANCA-positive group (p = 0.027, 0.002). There was no significant difference in the total remission rate of ANCA-positive patients receiving cyclophosphamide and mycophenolate mofetil as induction therapies (83.33% vs. 66.67%, p > 0.05), while patients receiving cyclophosphamide as induction therapy had a higher total remission rate than those receiving other immunosuppressants (83.33% vs. 20%, p = 0.028).

Conclusions

LN patients with ANCA seropositivity at renal biopsy have a significantly higher disease activity, and their pathological manifestations are predominantly proliferative LN. These patients require a more active immunosuppressive therapy with cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate mofetil to improve their remission rate.

1. Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease which usually involves multiple organs [Citation1]. The incidence of renal involvement in SLE is approximately 40–60% [Citation2], and lupus nephritis (LN) can be the first manifestation of SLE or occur within 5 years after SLE diagnosis [Citation3,Citation4]. It has been reported that 5-20% of LN patients develop into end-stage renal disease (ESRD) within 10 years after the diagnosis of SLE [Citation3]. LN is the leading cause of mortality in SLE patients [Citation5,Citation6]. Early identification of patients with active LN and providing them with aggressive immunosuppressive therapy is essential to increase remission rate and improve prognosis.

Some studies have shown that the clinical manifestations and laboratory findings of LN are not always parallel to the extent and severity of renal lesions, and early renal biopsy can help to confirm the diagnosis, assess the disease activity, and provide information for therapeutic decisions [Citation7,Citation8]. Although renal biopsy is now a routine operation in the Department of Nephrology, it is not very popular in other departments including rheumatology and dermatology. Also, some community hospitals or grassroots hospitals do not have the condition to perform renal biopsy, preventing some SLE patients from accessing timely renal pathological identification, which to some extent, affects the formulation of treatment plans. A study by Turner-Stokes T et al. [Citation9] observed that serum ANCA positivity was associated with renal pathological features of LN patients, and class IV-S LN was more common in the ANCA-positive group. If serum ANCA can serve as an alternative biomarker to predict active lesions in renal pathology, it will bring great convenience to the diagnosis and treatment of LN patients who cannot undergo renal biopsy.

As hallmark antibody for the diagnosis of primary systemic vasculitis, ANCA is a group of autoantibodies that uses the primitive granule component of neutrophil cytoplasm as a target antigen [Citation10]. The routine test for the detection of serum ANCA is indirect immunofluorescence, which is confirmed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The positive staining of ANCA can be categorized into three groups according to the staining patterns: cytoplasmic ANCA (c-ANCA), perinuclear ANCA (p-ANCA), and atypical ANCA (a-ANCA) [Citation11]. In addition to its existence in primary systemic vasculitis, ANCA has been detected in the serum of patients with SLE, anti-glomerular basement membrane disease, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, endocarditis, chronic infections, hematopoietic malignancies, and in patients who use certain medications [Citation12].

Previous study has reported that ANCA-positive LN patients often exhibit proliferative lesions, class IV LN, and high activity index in histological features [Citation13]. Another study found a significant increase in serum ANCA positivity in patients with crescentic LN [Citation14]. These results suggest that serum ANCA positivity may be associated with active proliferative LN. However, others revealed that there was no correlation between ANCA and disease activity [Citation15], and there was no significant difference in pathological type of LN between ANCA-positive and ANCA-negative groups [Citation16]. To further explore the correlations between ANCA and clinicopathological characteristics of LN, 115 biopsy-proven LN patients were divided into ANCA-positive and ANCA-negative groups. Their clinicalpathological features and prognosis were analyzed retrospectively.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients

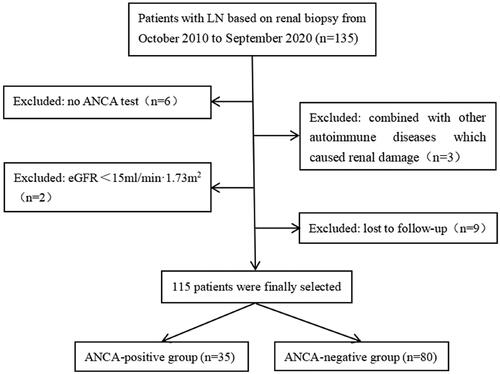

A total of 135 LN patients diagnosed by renal biopsy were recruited from October 2010 to September 2020 at the Department of Nephrology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University (Fuzhou, China). Inclusion criteria: (1) met the 1997 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) revised criteria for the diagnosis of SLE [Citation17]. (2) used the 2018 International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society (ISN/RPS) criteria for the classifications of LN [Citation18]. (3) detected the serum ANCA by indirect immunofluorescence and ELISA. Exclusion criteria: (1) combined with other autoimmune diseases (e.g. Sjogren’s syndrome). (2) ANCA false positive induced by some medications (e.g. penicillamine). (3) the presence of ESRD (eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2) at the time of renal biopsy. (4) with a follow-up duration of less than 6 months. Finally, 115 patients were selected and divided into an ANCA-positive group of 35 cases and an ANCA-negative group of 80 cases based on the ANCA test results ().

2.2. Data collection

Clinical parameters: gender; age; disease duration; SLE disease activity index (SLEDAI) [Citation19]; clinical manifestations, including malar rash, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, alopecia, adarthralgia, serositis, neuropsychiatric symptoms, fever, edema; laboratory data, including white blood cell count, lymphocyte count, hemoglobin, platelet count, serum albumin, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), urinary protein, microscopic hematuria, leukocyturia, 24-h urinary protein quantification, complement 3 (C3), complement 4 (C4), ANCA, ANA, anti-dsDNA antibody, anti-Sm antibody, anti-SSA antibody, anti-SSB antibody, anti-nucleosome antibody, anti-ribosomal P antibody, anti-Ro-52 antibody, and anti-histone antibody.

Pathological data: classification of LN, including class I, II, III, IV, V, and VI; the presence of endocapillary hypercellularity, glomerular leukocyte infiltration, microthrombosis/wire loop lesions, fibrinoid necrosis/karyorrhexis, cellular crescents, interstitial inflammation, glomerular sclerosis, fibrous crescents, tubular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis, and arteriolar lesions. Semi-quantitative scores for pathological activity index (AI), chronicity index (CI), and tubular interstitial lesion (TIL) were calculated with reference to the scoring method proposed by Austin HA et al. [Citation20].

2.3. Induction therapies and follow-up

Induction therapies, including steroid, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, and other immunosuppressants used during the first 6 months of renal biopsy were recorded. All 115 participants were followed up until March 31, 2023 or reached the observation endpoints. Each patient was followed up for at least 6 months, with serum creatinine, serum albumin, urinary protein or 24-h urinary protein quantification being recorded. After 6-months of induction therapy, their treatment response was classified as complete remission, partial remission, or non-remission based on the aforementioned indicators.

2.4. Definitions

Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg on three measurements taken on different days at rest, or a history of hypertension, or using antihypertensive medications to control blood pressure.

Leukopenia was defined as white blood cell count ˂ 4 × 109/L; anemia was defined as hemoglobin ˂ 120 g/L in males and hemoglobin ˂ 110 g/L in females; thrombocytopenia was defined as platelet count ˂ 100 × 109/L.

The eGFR was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiological Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation [Citation21].

Composite renal endpoint was defined as all-cause death, doubling of baseline serum creatinine, or progression to ESRD.

Complete remission was defined as proteinuria ˂ 0.3 g/24h, with serum albumin >35 g/L, and a normal range of serum creatinine. Partial remission was defined as proteinuria reduced to 0.3-2.9 g/24h and > 50% reduction from baseline value or urine protein (± - +), with serum albumin > 30 g/L, and a stable renal function (serum creatinine elevation ≤ 15% of the baseline value). Non-remission was defined as not meeting the abovementioned criteria.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS 25.0 software. All continuous variables underwent K-S test to determine normality. Normally distributed variables were presented as means ± standard deviation, and t-test was used for comparison between two groups. Non-normally distributed variables were presented as medians and interquartile ranges, and Mann–Whitney U-test was used for comparison between two groups. Categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages, and chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test were used for comparison between two groups. Kaplan–Meier survival curves and log-rank test were used to explore the relationship between ANCA and the cumulative renal survival rate of LN patients. Two-sided p < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

3. Results

3.1. General data and clinical parameters

A total of 115 patients with biopsy-proven LN were included in this study, including 14 males and 101 females, with a male-to-female ratio of 1:7.21. By the time of renal biopsy, patients’ age was 32 (26, 43), the disease duration was 8 (1, 60) months. There were 35 patients (30.43%) in the ANCA-positive group, of which 28 were pANCA, one was cANCA, and six were aANCA. Compared with the ANCA-negative group, the ANCA-positive group had significantly higher incidences of oral ulcers and thrombocytopenia (p = 0.006, 0.019, respectively). The SLEDAI score was significantly higher in the ANCA-positive group (p = 0.001). There were no significant differences in gender, age, and disease duration between the two groups. In terms of clinical manifestations, the incidences of malar rash, photosensitivity, alopecia, arthritis, serositis, neurological disorder, anemia, leukopenia, fever and edema did not differ significantly between the two groups ().

Table 1. Clinical characteristics and laboratory parameters of LN patients with and without ANCA.

3.2. Laboratory indexes

Compared with the ANCA-negative group, the ANCA-positive group had significantly lower lymphocyte count, serum albumin, and eGFR levels (p = 0.039, 0.027, and 0.045, respectively), higher 24-h urinary protein, serum creatinine, and uric acid levels (p = 0.023, 0.040, and 0.002, respectively), and a higher incidence of leukocyturia (p = 0.012). The ANCA-positive group also showed a significant decrease in C3 level (p = 0.009) and higher positive rates of anti-dsDNA antibody and anti-histone antibody (p = 0.001, 0.019, respectively) than the ANCA-negative group. The level of C4, the incidence of microscopic hematuria and the positive rates of ANA, anti-Sm antibody, anti-SSA antibody, anti-SSB antibody, anti-nucleosome antibody, anti-ribosomal P antibody, and anti-Ro52 antibody did not differ significantly between the two groups ().

3.3. Pathological indicators

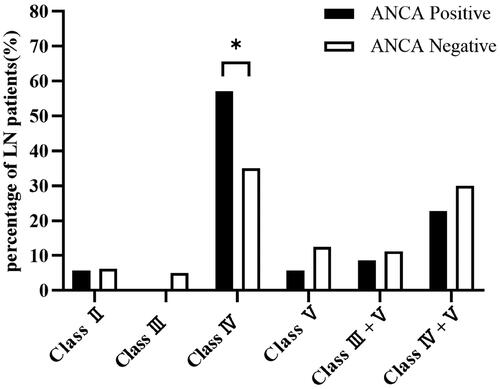

Class IV LN was the most common pathological type in both ANCA-positive and ANCA-negative groups, followed by class IV+V LN. The proportion of class IV LN was significantly higher in the ANCA-positive group than that in the ANCA-negative group (57.14% vs. 35%, p = 0.027), and there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in the other classes of LN (). The ANCA-positive group had a significantly higher AI score than the ANCA-negative group (11 vs. 8, p = 0.028), and the differences in CI and TIL scores were not statistically significant between the two groups. The incidence of fibrinoid necrosis/karyorrhexis was significantly higher in the ANCA-positive group compared with the ANCA-negative group (p = 0.002), whereas there were no statistically significant differences in the presence of endocapillary hypercellularity, glomerular leukocyte infiltration, microthrombosis/wire loop lesions, cellular crescents, interstitial inflammation, glomerular sclerosis, fibrous crescents, fibrillar crescents, tubular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis, and arteriolar lesions between the two groups ().

Table 2. Pathological features of LN patients with and without ANCA.

3.4. Induction therapy, treatment response, and renal outcomes

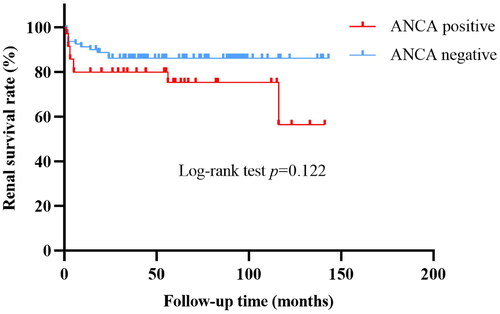

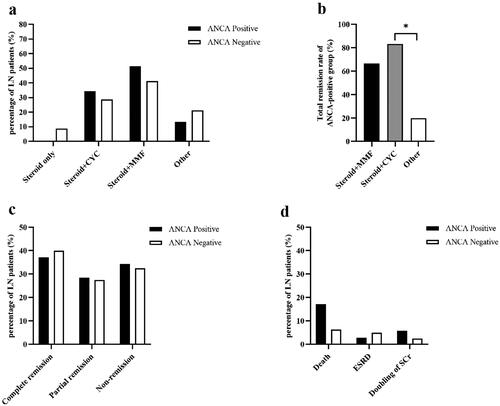

The induction therapy regimen for LN patients between ANCA-positive and ANCA-negative groups showed no statistically significant differences (). Among the 35 ANCA-positive LN patients, 18 (51.43%) received steroid + mycophenolate mofetil as induction therapy and 12 (34.29%) received steroid + cyclophosphamide. Among the 80 ANCA-negative LN patients, 33 (41.25%) received steroid + mycophenolate mofetil as induction therapy and 23 (28.75%) received steroid + cyclophosphamide. After 6 months of treatment, there were no significant differences in the complete remission rate, partial remission rate and non-remission rate between the two groups (). At the end of the study, the ANCA-positive group was followed up for 55 (14, 71) months, and the ANCA-negative group was followed up for 58.5 (33.5, 93.75) months. The incidences of all-cause death, doubling of serum creatinine, or ESRD did not differ significantly between two groups (). The causes of death in both groups were all respiratory failure or shock induced by severe infections. The cumulative survival rate of the ANCA-negative group was 86.25%, which was slightly higher than that of the ANCA-positive group (74.29%). Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed no significant difference in cumulative renal survival rate between the two groups (Log-rank test, χ2 = 2.396, p = 0.122) ().

Figure 3. Induction therapy, treatment response and renal outcomes of LN patients with and without ANCA. (a) Induction therapy of LN patients between ANCA-positive and ANCA-negative groups. (b) Induction therapy of ANCA-positive LN patients. (c) Treatment response of LN patients between ANCA-positive and ANCA-negative groups. (d) Renal outcomes of LN patients between ANCA-positive and ANCA-negative groups. *p = 0.028. CYC, cyclophosphamide; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; Scr, serum creatinine.

3.5. Treatment response of ANCA-positive LN patients

Of the 35 LN patients with serum ANCA positivity, 12 (34.29%) received cyclophosphamide as induction therapy, 18 (51.43%) received mycophenolate mofetil as induction therapy, and 5 (14.28%) received other immunosuppressants as induction therapy. The total remission rate (the sum of complete and partial remission rates) of those who receiving cyclophosphamide as induction therapy was 83.33%, which was slightly higher than those receiving mycophenolate mofetil (66.67%), however, this difference was not statistically significant. Patients receiving cyclophosphamide as induction therapy had a significantly higher total remission rate than those receiving other immunosuppressants. (83.33% vs. 20%, p = 0.028) ().

4. Discussion

In this study, we found that LN patients with serum ANCA positivity at renal biopsy had significantly higher SLEDAI and AI scores than those without. Proliferative LN was more common in ANCA-positive group and these patients had a significantly higher total remission rate when receiving cyclophosphamide as induction therapy. However, we did not find serum ANCA positivity was associated with the induction treatment response and poor renal outcomes of LN.

The positive rate of ANCA in LN patients varied widely among different studies, ranging from 13.2%−37.3% [Citation16,Citation22,Citation23]. This may be due to demographic differences, different inclusion criteria, and different ANCA detection methods. In this study, 35 of 115 patients (30.43%) were found to be positive for ANCA detecting by indirect immunofluorescence, of which 28 were pANCA, one was cANCA, and six were aANCA. ELISA detection for ANCA was mainly aimed at anti-MPO and PR3 antibodies, unfortunately, few patients had positive anti-MPO and PR3 antibodies. It has been reported that the positivity of serum ANCA was significantly higher in patients with LN than in SLE patients without renal involvement [Citation24,Citation25]. Another study has shown that the proportion of pANCA was significantly higher in diffuse proliferative LN [Citation23], suggesting that ANCA may be associated with renal involvement in SLE, especially with proliferative LN.

Our study found that patients in the ANCA-positive group exhibited a significantly higher SLEDAI score than those in the ANCA-negative group, indicating that ANCA is associated with disease activity, which is consistent with the results shown in previous studies [Citation24,Citation25]. In terms of clinical manifestations, the incidences of oral ulcers, thrombocytopenia, and leukocyturia in the ANCA-positive group were significantly higher than that in ANCA-negative group. Since oral ulcers, thrombocytopenia and leukocyturia are all indicators of disease activity in the SLEDAI score program [Citation19], this further confirms the correlation between ANCA and disease activity. It was reported that the incidences of renal involvement, neurological disorders, myocarditis, and plasmapheresis were significantly higher in SLE patients with serum ANCA positivity than those without [Citation26]. Another study found that LN patients in the ANCA-positive group had significantly higher incidences of alopecia, oral ulcers, photosensitization, and skin damage than those in ANCA-negative group [Citation22]. These results suggest that ANCA positivity is associated with some clinical manifestations and organ damage in SLE. However, a previous study reported that although ANCA was only associated with SLE disease activity, and there was no correlation between ANCA and clinical manifestations or organ involvement [Citation26]. Another investigation suggested that ANCA positivity was not associated with either SLE disease activity or specific organ damage [Citation15].

Many studies have shown a worse baseline renal function, a more significant decrease in serum C3 or C4 levels, and an increased odds of having abnormal antibody profiles in ANCA-positive patients [Citation9,Citation25,Citation27]. Similarly, in our study, LN patients in the ANCA-positive group had a lower eGFR level and a higher serum creatinine level, which also justified the worse renal function of ANCA-positive patients at the time of renal biopsy. Moreover, the ANCA-positive group had higher positive rates for anti-dsDNA antibodies and anti-histone antibodies, with a lower C3 level. It is well known that C3 and anti-dsDNA antibody are sensitive indicators of SLE and LN disease activity [Citation28]. Thus, our study further supports that ANCA is associated with LN disease activity. There is existing evidence showing that serum albumin and uric acid levels are associated with SLE disease activity and renal involvement. Yip J et al. [Citation29] found a negative correlation between serum albumin and SLEDAI-2K score, which was particularly strong in LN patients compared to SLE patients without renal involvement. Hafez EA et al. [Citation30] observed that blood uric acid was positively correlated with SLEDAI score, and the blood uric acid level and SLEDAI score of LN patients were significantly higher than those of SLE patients without renal involvement. We found a significant decrease in serum albumin level and significant increases in blood uric acid and 24-h urinary protein levels in the ANCA-positive group than that in the ANCA-negative group, reiterating the correlation between ANCA and disease activity.

LN is characterized by subepithelial or subendothelial immune complex depositions [Citation31], while ANCA-associated vasculitis is characterized by scanty immune depositions [Citation32]. Recently, some studies have reported that the pathologic changes of ANCA-associated vasculitis can be found in the renal biopsy pathology of LN patients with serum ANCA positivity, exhibiting as more crescent formation and less subendothelial immune deposition [Citation33,Citation34], suggesting that ANCA may be involved in the pathogenesis of crescentic LN. We found that the proportion of class IV LN in the ANCA-positive group was significantly higher than that in the ANCA-negative group (57.14% vs. 35%, p = 0.027), which was in accordance with previous reports [Citation9,Citation13,Citation23]. This result indicated that ANCA may reflect the pathologic characteristics of class IV LN. We also found that the AI score and the incidence of necrosis/karyorrhexis were significantly higher in the ANCA-positive group, suggesting a correlation between ANCA and active proliferative lesions. Li C et al. [Citation35] revealed that ANCA-positive LN patients had significantly higher AI and CI scores than ANCA-negative LN patients, with significantly higher proportion of cellular crescents, interstitial inflammation, tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis. In contrast, Pyo JY et al. [Citation16] showed that ANCA positivity at renal biopsy was associated with the CI score and was irrelevant to the AI score. Fan Y et al. [Citation36] demonstrated that the proportion of ANCA did not differ significantly between LN patients with scanty immune deposits and with immune complex deposits, and LN patients with scanty immune deposits exhibited significantly lower activity characteristics on renal biopsy. Therefore, serum ANCA positivity may be related to either active or chronic lesions in renal biopsy of LN patients. It is highly recommended that these patients should undergo renal biopsy as soon as possible to determine their pathological changes.

Steroid combined with cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate mofetil is a commonly used induction therapy for proliferative LN. A systematic review covering 67 studies and 4791 participants showed that in the induction therapy of proliferative LN, mycophenolate mofetil may increase the complete remission rate of patients compared to intravenous injection of cyclophosphamide, without increasing the incidence of adverse events [Citation37], indicating that compared to cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil maybe a more effective and safer induction therapy for patients with proliferative LN. In our study, class IV LN was most common in both the ANCA-positive and ANCA-negative groups, and there were no significant differences in the induction therapy regimen and treatment response between the two groups. However, some studies have shown that the remission rate of ANCA-negative group was significantly higher than that of ANCA-positive group [Citation22,Citation27]. This difference may be due to the small sample size of this study, and some patients may take longer than 6 months to achieve remission. Regarding induction therapy in ANCA-positive LN patients, a study observed that patients receiving mycophenolate mofetil as induction therapy had a higher total remission rate than those receiving cyclophosphamide as induction therapy (75% vs. 33.3%, p = 0.021) [Citation35]. However, we found no significant difference in the total remission rate between the mycophenolate mofetil group and cyclophosphamide group after 6-months of induction therapy (66.67% vs. 83.33%, p > 0.05). Our study revealed that patients receiving cyclophosphamide as induction therapy had a higher total remission rate than those receiving other immunosuppressants as induction therapy (83.33% vs. 20%, p = 0.028). Given the pathological presentation of ANCA-positive LN patients are often proliferative LN, active immunotherapy should be used to improve the remission rate of these patients. Our study confirmed that cyclophosphamide has better efficacy in these patients.

Opinions on whether ANCA affects the prognosis of LN patients are still inconsistent. Some studies have reported that the cumulative renal survival rate of ANCA-positive LN patients is significantly lower than that of ANCA-negative patients, ANCA positivity is an independent risk factor affecting the prognosis of LN [Citation22,Citation27]. Other study found that ANCA positivity was not associated with death or renal failure of LN patients [Citation16]. In our study, the cumulative renal survival rate in the ANCA-negative group was slightly higher than that in the ANCA-positive group (86.25% vs. 74.29%), however, Kaplan-Meier analysis showed no statistically significant difference in renal survival rate between the two groups. It is worth mentioning that all patients entering the renal composite endpoint event were class IV or IV + V LN patients, and the causes of death were all respiratory failure or shock induced by severe infections. The increased risk of infection might be explained by the active immunosuppressive therapy adopted by these patients whose renal pathology mostly showed proliferative changes. Therefore, patients with active proliferative LN should be carefully monitored to prevent the occurrence of infection while using immunosuppressive therapy.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, it was a single-center study with a small sample size. Secondly, the progression of LN patients is slow, and the median follow-up time in this study is relatively short (< 5 years), hence the long-term outcomes of patients are yet to be observed. Thirdly, the types of ANCA detected by ELISA in our center were MPO and PR3, and due to the small sample size, there were few cases involving MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA. Thus, MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA were not analyzed in this study. Therefore, prospective, multicenter, and large-scale studies are required to further verify the clinical significance of ANCA positivity in LN patients.

In conclusion, LN patients with serum ANCA positivity at renal biopsy have a significantly higher disease activity, with their pathology more commonly manifested as proliferative LN. These patients require active immunosuppressive therapy with cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate mofetil to improve the remission rate.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: Yi Chen, Jianxin Wan; Data curation: Jing Zhang; Formal analysis: Jing Zhang, Ruoshan Lian; Investigation: Yi Chen, Jianxin Wan; Methodology: Yi Chen; Software: Ruoshan Lian; Supervision: Yi Chen, Jianxin Wan; Writing—original draft: Jing Zhang, Ruoshan Lian; Writing—review & editing: Yi Chen, Jianxin Wan; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Hospital Affiliated to Fujian Medical University [Min Medical University Affiliated to the First Ethical Medical Technology Review (2015) 084-1].

Informed consent statement

All patients had provided written informed consent to participate in the study, and the study protocol was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the study patients and doctors in the Department of Nephrology, Blood Purification Research Center, the First Affiliated Hospital, Fujian Medical University who contributed to this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Yu C, Li P, Dang X, et al. Lupus nephritis: new progress in diagnosis and treatment. J Autoimmun. 2022;132:1.

- Weinmann-Menke J. [Lupus nephritis: from diagnosis to treatment]. Inn Med (Heidelb). 2023;64(3):225–10. doi: 10.1007/s00108-023-01489-y.

- Anders HJ, Saxena R, Zhao MH, et al. Lupus nephritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):7. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0141-9.

- Mahajan A, Amelio J, Gairy K, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus, lupus nephritis and end-stage renal disease: a pragmatic review mapping disease severity and progression. Lupus. 2020;29(9):1011–1020. doi: 10.1177/0961203320932219.

- Renaudineau Y, Brooks W, Belliere J. Lupus nephritis risk factors and biomarkers: an update. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(19):14526. doi: 10.3390/ijms241914526.

- Obrișcă B, Sorohan B, Tuță L, et al. Advances in lupus nephritis pathogenesis: from bench to bedside. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(7):3766. doi: 10.3390/ijms22073766.

- Hsieh YP, Wen YK, Chen ML. The value of early renal biopsy in systemic lupus erythematosus patients presenting with renal involvement. Clin Nephrol. 2012;77(1):18–24. doi: 10.5414/cn107094.

- Mahmood SN, Mukhtar KN, Deen S, et al. Renal biopsy: a much needed tool in patients with systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE). Pak J Med Sci. 2016;32(1):70–74. doi: 10.12669/pjms.321.3386.

- Turner-Stokes T, Wilson HR, Morreale M, et al. Positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody serology in patients with lupus nephritis is associated with distinct histopathologic features on renal biopsy. Kidney Int. 2017;92(5):1223–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.04.029.

- Cristea A, Badea T, Bodizs G, et al. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies (ANCA)–markers in diagnosis and monitoring systemic vasculitides. Rom J Intern Med. 1995;33(1-2):37–46.

- Suwanchote S, Rachayon M, Rodsaward P, et al. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and their clinical significance. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37(4):875–884. doi: 10.1007/s10067-018-4062-x.

- Weiner M, Segelmark M. The clinical presentation and therapy of diseases related to anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15(10):978–982. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2016.07.016.

- Lacetera R, Calatroni M, Roggero L, et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of ANCA positivity in lupus nephritis: a case series of 116 patients and literature review. J Nephrol. 2023;36(4):1059–1070. doi: 10.1007/s40620-023-01574-3.

- Yu F, Tan Y, Liu G, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics and outcomes of patients with crescentic lupus nephritis. Kidney Int. 2009;76(3):307–317. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.136.

- Fauzi AR, Kong NC, Chua MK, et al. Antibodies in systemic lupus antineutrophil cytoplasmic erythematosus: prevalence, disease activity correlations and organ system associations. Med J Malaysia. 2004;59(3):372–377.

- Pyo JY, Jung SM, Song JJ, et al. ANCA positivity at the time of renal biopsy is associated with chronicity index of lupus nephritis. Rheumatol Int. 2019;39(5):879–884. doi: 10.1007/s00296-019-04263-2.

- Hochberg MC. Updating the American college of rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(9):1725–1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928.

- Bajema IM, Wilhelmus S, Alpers CE, et al. Revision of the international society of nephrology/renal pathology society classification for lupus nephritis: clarification of definitions, and modified national institutes of health activity and chronicity indices. Kidney Int. 2018;93(4):789–796. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.11.023.

- Gladman DD, Ibañez D, Urowitz MB. Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(2):288–291.

- Austin HA, 3rd, Boumpas DT, Vaughan EM, et al. Predicting renal outcomes in severe lupus nephritis: contributions of clinical and histologic data. Kidney Int. 1994;45(2):544–550. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.70.

- Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006.

- Wang Y, Huang X, Cai J, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics and outcomes of lupus nephritis with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody: a retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(4):e2580.). doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002580.

- Chin HJ, Ahn C, Lim CS, et al. Clinical implications of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody test in lupus nephritis. Am J Nephrol. 2000;20(1):57–63. doi: 10.1159/000013557.

- Pradhan VD, Badakere SS, Bichile LS, et al. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) in systemic lupus erythematosus: prevalence, clinical associations and correlation with other autoantibodies. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:533–537.

- Pan HF, Fang XH, Wu GC, et al. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in new-onset systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. Inflammation. 2008;31(4):260–265. doi: 10.1007/s10753-008-9073-3.

- Nishiya K, Chikazawa H, Nishimura S, et al. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus is unrelated to clinical features. Clin Rheumatol. 1997;16(1):70–75. doi: 10.1007/BF02238766.

- Wang S, Shang J, Xiao J, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics and outcomes of lupus nephritis with positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody. Ren Fail. 2020;42(1):244–254.

- Alforaih N, Whittall-Garcia L, Touma Z. A review of lupus nephritis. J Appl Lab Med. 2022;7(6):1450–1467. doi: 10.1093/jalm/jfac036.

- Yip J, Aghdassi E, Su J, et al. Serum albumin as a marker for disease activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(8):1667–1672. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.091028.

- Hafez EA, Hassan SAE, Teama MAM, et al. Serum uric acid as a predictor for nephritis in egyptian patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2021;30(3):378–384. doi: 10.1177/0961203320979042.

- Parodis I, Tamirou F, Houssiau FA. Prediction of prognosis and renal outcome in lupus nephritis. Lupus Sci Med. 2020;7(1):e000389. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2020-000389.

- Lamprecht P, Kerstein A, Klapa S, et al. Pathogenetic and clinical aspects of anti-Neutrophil cytoplasmic Autoantibody-Associated vasculitides. Front Immunol. 2018;9:680. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00680.

- Morimoto S, Watanabe T, Lee S, et al. Improvement of rapidly progressive lupus nephritis associated MPO-ANCA with tacrolimus. Mod Rheumatol. 2010;20(3):291–294.

- Nasr SH, D’Agati VD, Park HR, et al. Necrotizing and crescentic lupus nephritis with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody seropositivity. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(3):682–690. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04391007.

- Li C, Zhou ML, Liang DD, et al. Treatment and clinicopathological characteristics of lupus nephritis with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody positivity: a case-control study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(7):e015668. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015668.

- Fan Y, Kang D, Chen Z, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics and outcomes of lupus nephritis patients with scanty immune depositions in kidney biopsies. J Nephrol. 2023;36(8):2345–2354. doi: 10.1007/s40620-023-01622-y.

- Tunnicliffe DJ, Palmer SC, Henderson L, et al. Immunosuppressive treatment for proliferative lupus nephritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6(6):Cd002922.