ABSTRACT

This article reassesses themes in the present literature on borders in political geography by using the case study of Israel's border with Lebanon. This securitized landscape invites a definition of the border predicated on a neat dichotomy between one's own identity and a foreign and dangerous “Other.” However even this border is a complex and contradictory boundary, in which residents’ attitudes, beliefs and practices are ambivalent and defy neat categorization. This study provides a more nuanced account of geographical imagination at this border by treating the borderland as a heterotopic space, rather than perceiving the border as a fixed line, and by examining the everyday “micro-political” operations and materialities that inhabitants of the border region perform and experience. While there is clearly a relationship between security and identity at this border, the outcome of this research indicates that this relationship is non-linear and more complex than can be allowed for by a hostile cultural imagination solely based on a self/Other dyad.

Introduction

For recent theoretical conceptualizations of borders in geography and related disciplines, Israel's northern border with Lebanon is a glaring anachronism. The Blue Line, the armistice line between Israel and Lebanon delineated by the UN in 2000 that acts as a de facto border due to the lack of a permanent border agreement between the two states, remains a heavily militarized and sealed boundary (O'Shea Citation2004). This confounds critical and post-structuralist geographers’ recent focus on reterritorialization through “smart borders” that use advanced surveillance technologies and human intelligence to selectively include “desirables” while filtering out the dangerous Other as a way of reconciling globalized neo-liberal flows with post 9–11 insecurity (Sparke Citation2006).

This article will address this disjunction between recent theoretical directions and the conditions on the ground at a specific border by examining the small scale “micro-politics” that make up the Israeli side of the border, rather than attempting to analyze both sides of the Israel-Lebanon border from a traditional perspective through top-down terms of regional politics and international relations. In doing so it will attempt to explicate how the identities and geopolitical positions of Israeli border residents are affected by the spatial proximity of the securitized border.

In particular, this research will question the notion evinced by some post-structuralist geopolitics and critical security studies that the materialities of security are the function of a binary geographical imagination of identity being constructed in diametric opposition to a threatening or somehow irreconcilably different “Other.” One of the most influential works in this vein is Derek Gregory's polemic The Colonial Present. In this book Gregory (Citation2004) argues that a colonial “geographical imagination” operates through security discourses to influence the militaristic materialities that enforce occupation. He traces this imagination to Said's Orientalism in which difference is “construct[ed] and calibrat[ed]” (Gregory Citation2004, 17) by “designating in one's mind a familiar space which is ‘ours’ and an unfamiliar space beyond ‘ours’ which is ‘theirs'” (Said Citation1979, 54). This sense of intractable difference gives rise to a colonialist imperative by “the West” directed at “the East” that is used to justify invasions and atrocities. Gregory's exemplars are the US post-9/11 interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan and Israel's military activity in the West Bank and Gaza.

Yiftachel points out that Gregory's analysis is particularly problematic with respect to Israel due to its “flattening of difference between American and Israeli colonialism(s)” and its “overlooking of the dialectics of violence and deep chasms in Israeli society” (Yiftachel Citation2008, 365). An integral part of Gregory's argument is that imagined distance has an influence on the actions of the “colonial powers” that supercedes physical distance. In other words, violence becomes acceptable because of the salience of an imagined separation between “the self” and “the Other” despite the physical proximity between soldier and (human) target. In the Israeli case in particular, this ignores the complexity of the close physical proximity of Israelis and the “Arab Other” in shaping the discourses and materialities of security. It also paints Israel as “monolithic,” ignoring the “highly controversial” nature of the nationalist “expansionist ethnicization project” that has “caus[ed] widespread discrimination, dispossession and conflict” deeply dividing mainly secular Israeli leftists from their religious-nationalist right-wing counterparts, and has been the cause of “repeated political crises” (Yiftachel Citation2008, 367).

Another critique of The Colonial Present presented by Ó Tuathail is that it lacks a sophisticated concept of the relationship between “the more formalized geopolitical visions and the high practical geopolitics of statecraft” and the more “mundane … popular geopolitics.” He further suggests that Gregory is unable “to distinguish competing geopolitical discourse within these geopolitical cultures, alternative geopolitical storylines which contest those held by the administration in power” (Ó Tuathail Citation2008, 341–342). This critique corroborates the argument presented in this article that a dualistic Saidian cultural imagination of “us/them” (Ó Tuathail Citation2008, 341) is unable to account for the acute level of nuance and diversity of geopolitical understandings expressed through quotidian “popular geopolitics.” While the “architecture of enmity” that Gregory (Citation2004, 20) describes certainly does exist along the Blue Line in the form of border fences and military installations, this is related to a materialized discourse of security and does not constitute a coherent “geographical imagination,” particularly when culture is given consideration in light of the spatial proximity and cultural “transition zone” of the borderland (Popescu Citation2012, 16). In other words, the “enmity” produced by elite geopolitical discourses are not uncritically accepted verbatim by the public as Gregory (Citation2004, 141) insinuates. Rather, much like the heterotopic space of the borderland, everyday geopolitical imaginations in border spaces are heterogeneous and ambivalent, often defying the binary terms favored in the Western philosophical tradition that seek to classify space into neatly divided categories (Ahn Citation2010, 206).

Borders in theory and practice

Recent post-structuralist border theorists have worked to emphasize the contingency and multiple aspects of borders. In doing so, they see the borders not as a fixed line, but as a mutable process that is constantly reshaped and negotiated through processes of deterritorialization and reterritorialization (e.g. Ó Tuathail Citation1998; Paasi Citation1998, Citation1999). Based on Deleuzian theory, the concept of deterritorialization suggests that borders rapidly dissolve due to factors such as new interstate configurations including the EU, globalization and network flows, and the collapse or split of nation-states. However, this dissolution is not an ultimate step in a historical teleology. Ó Tuathail argues “that what we are dealing with is not deterritorialization alone but a rearrangement of the identity/border/order complex that gives people, territory, and politics their meaning in the contemporary world.” Put differently, “geography is not so much disappearing as being restructured, rearranged and rewired” (Ó Tuathail Citation1999, 143, 147).

The recent theorization of fluid borders has also been critiqued as partial and naïve since “territorial borders are still used as key strategies to objectify space” (Van Houtum and Naerssen Citation2002, 128). Furthermore, the treatment of deterritorialization and reterritorialization as an altogether novel phenomenon concomitant with globalization has been brought into question. Walters writes that borders have “always” existed for the purpose of selectively “filter[ing] … the good and the bad, the useful and the dangerous, the licit and the illicit” in order to produce a “high-trust” interior secured from the wild zones outside (Walters Citation2006, 197).

In keeping with the understanding that borders are malleable and ever-changing, Popescu has created a typology that resists limiting the border to a specific location but rather suggests that bordering takes place at multiple scales and locations through “borderlands, networked borders and border lines” (Popescu Citation2012, 77–78). While this article will draw on all three elements of this border typology, the borderland concept is a particularly useful tool for thinking about the Galilee border region as it spatializes the fixed territorial aspect of bordering processes in addition to the border's permeable qualities. Newman further elaborates on the unique spatial configuration of the borderland:

The discussion concerning the nature of borders as bridges and points of interaction (as contrasted to their traditional role of barriers) is of relevance in the sense that borders can become transformed into the frontiers (in the most positive sense of the term) where people or groups who have traditionally kept themselves distant from each other, make the first attempts at contact and interaction, creating a mixture of cultures and hybridity of identities. (Newman Citation2006, 150).

The notion of the borderland as a “frontier” suggests that the physical distance from the core has the productive effect of creating an epistemological distance from dominant discourses and the exercise of state power that can facilitate the dissolution of boundaries that create absolute difference. However, Diener and Hagen counter an overly naive perception of borderlands as sites of hybridity, stating that although “[o]ften portrayed in the positive light of cosmopolitanism, borderland populations can exist at both the physical and social margins of their national society” (Diener and Hagen Citation2009, 1207). This article will exploit the tension between the borderland as a site of mixity with the potential to break down barriers, and the contrasting view of the borderland as a marginalized periphery to evoke the complex and contradictory qualities of the ontological processes that occur at the border.

Megoran suggests that as “an alternative way forward that builds on an understanding of boundaries and borders as social processes in general but that addresses the shortcomings of the bordering and bounding approach … it is productive to think about international boundaries as having biographies” (Megoran Citation2011, 467). This approach is a productive way of thinking about the specific historical, geopolitical and ethno-national circumstances that contextualize the border to deconstruct an essentialist and synchronic reading of border landscapes. Megoran, also cautions in his article on the geopolitics of danger in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan “that not all societies operate the same mechanisms of demonization and exclusion, and we must be wary of reinscribing them as inevitable conditions of social formation” (Megoran Citation2005, 575). In keeping with Megoran's methodology, this research will examine how Israel's northern border is re/produced by documenting and explaining some of the practices and knowledges that elucidate Israeli understandings of identity, security and space. This approach has the potential to reveal new knowledge about how borders shape “geographical imaginations” (Gregory Citation2004).

A notable difference between Megoran's research and my own was his sole methodological focus on representation in texts such as newspaper and printed media, while my research combined textual analysis with a study of everyday practices, symbols and materialities. Dittmer and Gray note that one of the main contributions of “critical” geopolitics “has been the recognition of geopolitics as something everyday that occurs outside of academic and policymaking discourse.” However, they admonish critical geopolitics’ “excessive attention to texts” and overemphasis on power relations and the agency of elites in shaping geopolitical discourses (Dittmer and Gray Citation2010, 1664–1665). This call to pay attention to “popular geopolitics” effectively critiques the Gramscian notion held by many academics that individuals uncritically consume and internalize “elite” discourses disseminated through media outlets and official propaganda.

Ethnography is an appropriate methodology for getting at “popular geopolitics” as it allows for evidence to be gathered at the everyday level to uncover insights that analysis of grand geopolitical narratives would obfuscate. Müller suggests that the geopolitical discourses typically represented in “critical” geopolitics ignore “the influence of local, regional or institution context” and

elides the fact that … there is a reciprocal relationship between the national or global level, and the local or organisational level, and … that at these sub-levels the imaginations may be far more fiercely contested than becomes apparent from looking at codified sublimations only (Müller Citation2009, 12).

According to Müller, ethnography provides a corrective for the totalizing perspective of much geopolitical research because of “its ability to listen to the routine ways in which people make sense of the world in everyday life” (Müller Citation2009, 74–75). In the specific context of borders, Newman suggests that

one of the challenges of border theorizers is to collect these narratives and to put them together in such a way that the different types of barrier or interaction functions of the border—be they visible in the landscape or not—are understood at this local level of daily life practices (Newman Citation2006, 153–154).

Due to the political sensitivity of this research, careful use of informal semi-structured interviews as an ethnographic technique helped to establish a rapport with informants that made them more open to sharing information and opinions. Semi-structured interviews work as “conversation with a purpose” to gain in-depth understandings that dynamically respond to interviewees’ knowledges and subjectivities, and unlike more structured data gathering methods, is sensitive to informants and fosters more balanced power relations based on dialogue rather than interrogation by the researcher (Eyles Citation1988). While a researcher from a British university is likely to be spatially and emotionally distant from the violence that has periodically erupted along the Israel–Lebanon border, he or she must be empathetic since many of the local informants will have been directly affected by this political violence. Also, a direct line of question might only lead to a superficial recitation of dominant “security” language broadcasted by political elites. While such a stance is certainly likely to be an internalized aspect of an individual's response to geopolitical danger and should not be dismissed out of hand, it might elide the complexity or nuances of a person's views.

The analysis of textual representations of the border in Israeli newspaper reports provided some useful perspectives about cultural imaginations of the border, narratives about difference, and the political production of space to supplement the primary ethnographic research. Newspaper accounts also provide detailed description of specific key incidents in detail and in some cases document their aftermath and effects to show how security is relationally produced. In order to critically evaluate the discursive position and bias of journalistic texts, and to demonstrate how the meaning of these texts are produced in dialogue or opposition to other texts and discursive positions (Fowler Citation1991), I deliberately sampled from a range of English language daily newspapers. These included the left-wing Haaretz, Ynet, the web outlet for the popular centrist Yedioth Ahranoth, and the conservative-leaning Jerusalem Post.

Living on the edge: locating the border in Israeli space

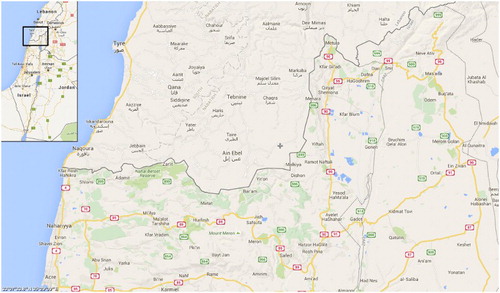

The Galilee region is a frontier located at the periphery of Israeli space in relation to the core region encompassing the area between Haifa and Jerusalem (). The Galilee is highly ethnically mixed with a roughly even population of Jews and ethnic minorities. According to a recent OECD report submitted by Israel “[w]ith 44% Jews, 46% Arab and 8% Druze, the Northern District is the most diverse in Israel.” The remaining 2% is mostly comprised of Circassians and Bedouin (Golub Citation2009, 14).

Figure 1. Map of the Israel/Lebanon/Syria Border Region Showing the Blue Line and the Northern Half of the Golan Heights. Source: Google Earth.

From a historical perspective, between the 1500s and the First World War, the entire Levant was part of the Ottoman Empire and the distinct national entities endemic to the region at present did not exist. Rather, the territory belonged to Ottoman administrative districts (Fraser Citation2004, 2). Following the Ottoman’ defeat in the First World War the empire was dismantled and the territory was partitioned by the victors into a British Mandate comprised of Palestine, Trans-Jordan (although the British granted limited political control to the Hashemite Emirate) and Iraq and a French Mandate that included Lebanon and Syria (Gil-Har Citation2000, 70). The border between British and French rule was carved by French and British cartographers, along boundaries agreed during the San Remo Peace Conference in 1920, which were partly based on the earlier secret Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916. Kaufman notes that “as in other places in the Middle East, and for that matter in the colonial world as a whole, it was impossible to create these borders without influencing and disturbing the local population for whom they made little sense” (Kaufman Citation2006, 705). This suggests that the present delineation of nation states in the region is not an intrinsic or inalienable set of cultural categories for residents of the borderlands, notwithstanding the later introduction of more extensive Jewish settlement in the Galilee.

The spatial dynamics of the border region were drastically altered following the creation of the State of Israel in the aftermath of the 1948 Arab–Israeli war. The North became an internal frontier that Zionist leaders in the post-1948 period sought to “Judaize” through regional planning policies. According to Kipnis the two main objectives of these policies were to engineer “a demographic balance in favor of Jews” and “the deployment of a continuous network of Jewish settlements along hostile borders and densely populated Arab territories” (Kipnis Citation1984, 191). The latter objective indicates the “defensive function” of civilian settlements in the “security landscape” of the Israeli periphery based on their location in areas deemed to be of “present, or future, strategic importance to [the] Jewish state” (Newman Citation1989, 220; Soffer and Minghi Citation1986).

A specific feature of the Israeli “periphery” in the Galilee is the phenomenon of “Development Towns” (DTs) in which planners strategically deployed “marginal segments” of the Jewish migrant population, first Mizrahi immigrants from North Africa in the 1950s and later Russian Jews, in order to achieve Jewish control of the North. Tzfadia argues that “these policies perpetuate the marginality of the towns and preserve the unequal geographical distribution of power and wealth, as well as reinforce ethnic and class stratification” (Tzfadia Citation2006, 523). Furthermore, Falah problematizes the “Judiazation” policy in relation to the Galilean Arab minority within the framework of Israeli democracy as they are Israeli citizens “theoretically entitled to equal rights” to Jews, while simultaneously being “perceived as belonging in national terms to the broader Palestinian people, with whom Israeli Jews are locked in struggle over the territory of Palestine” (Falah Citation1989, 230).

The ethnographic component of this research was mostly carried out in and around the development towns of Kiryat Shemona and Maalot-Tarshiha, both located within ten kilometers of the Blue Line. The latter is a particularly interesting site as it is a mostly ethnically segregated but jointly administered conurbation comprised of the Arab town of Tarshiha and the Jewish DT of Maalot, built more recently alongside it (Shmueli and Kipnis Citation1998, 227). Generally, the DTs featured calculated urban planning with communist-style concrete apartment blocks. Until quite recently these towns were viewed as highly undesirable places to live due to poor quality housing, a lack of jobs, and high levels of social deprivation, and to some extent still are due to the higher risk of political violence from across the border. However in the last few years, the stigma attached to the DTs has decreased due to the building of new neighborhoods with large single-family suburban style homes, increased government investment in business and infrastructure, and financial incentives such as subsidies and tax breaks to encourage families to move there (Yiftachel Citation1997).

In agreement with Gregory's notion of understanding of colonialism as a “cultural process … energized through signs, metaphors and narratives” (Gregory Citation2004, 8), Yiftachel defines the frontier in which the northern development towns are located as “the geographical, political or cultural margins of the collective” (Yiftachel Citation1997, 151). He continues by suggesting that the settlement of frontiers is a powerful tactic employed by the dominant group to maintain its hegemonyFootnote1:

Significantly, internal frontiers also play a central role in nation- and state-building. These are “alien” areas within the collective's boundaries into which the core attempts to expand, penetrate and increase its control. (Yiftachel Citation1997, 151)

Yiftachel aptly points out that internal frontiers are marginal spaces with a weak relation to the centers of power and control located at the core and has repeatedly used the Galilee region as a case study for the “frontier” (Yiftachel Citation1997, Citation1998, Citation2001; Yiftachel and Meir Citation2006). However, the way he views the processes at work on the border takes an inflexibly top-down view that denies the possibility of local agency and cultural transformation, which this article shows to be subtly but powerfully changing the periphery. Furthermore, the unidirectional flow of power dictated by the core/periphery model ignores the ways in which the local cultures can form organically without strict orchestration from the core, or even dialogically with the core, and how cultural and social processes can “rebound” from the margins to reconfigure the center.

I witnessed a moment of such potential transformation during a previous visit to the area in August, 2011. At the time, nationwide social protests were taking place in solidarity with the “tent city” protests in Tel Aviv over domestic concerns such as the lack of affordable housing and the high cost of living in Israel. At the entrance to the Druze village of Hurfeish, about 2.8 miles from the Blue Line, protesters had erected a large tent over the square containing an equestrian statue of the Druze hero Sultan Al-Atrash. Along with local youths burning tires in a display of dissent, the protesters had hung a large Druze flag and homemade signs around the square with political slogans. One of these entreated “Gilad and Bibi come home,” a call for both the return of the hostage Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit, who had been held captive in Gaza for over five years at that point, and for Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu to leave office.Footnote2 Another sign called for more housing to be funded for Druze ex-soldiers.

This instance shows Druze identification with the goals of the national protest movement and its participation within Israeli civil society. It also simultaneously highlights a demand for recognition of the community's Druze identity as distinct and viable, as evidenced by the symbolic significance of placing a tent over the statue of a revered Druze leader and the high visibility of the large Druze flag to those entering the village from the busy public road that cuts through it. The voice of the Druze community is also given weight in public discourse by the fact that, other than the small Muslim Circassian community, they are the only ethnic minority in Israel that face mandatory conscription into the Israel Defense Forces (IDF).Footnote3 Hence the significance of the sign in support of Shalit, since he was a national symbol as an “everyman” for all young conscripts who risk sacrificing “a quiet, peaceful, dignified life” for the security of the state (Leibovitz Citation2011).

Security and threat at the border

Daily life in the Galilee is in part defined by its geopolitical position in proximity to the borders of the “enemy” states of Lebanon and Syria. This closeness is perceived as a root cause of threat, particularly in the form of Katyusha rocket fire and cross-border terror attacks from Hezbollah, the Shiite political and militant group that controls southern Lebanon, and Palestinian militant factions in Lebanon. As a result, the area features prominently in the national security discourse and is materially securitized through architecture, military technologies and bodily practices.

Two diametric psychological operations work simultaneously at Israel's northern borders in relation to danger and security, fear and normalization. Fear reflects the deep anxiety inhabitants face about the possible threat of bodily harm from rockets, artillery, bombs and gunfire. Normalization is a “tactic” deployed by residents to make everyday life livable in the face of adversity (Certeau Citation1984: xix).

Megoran presents the notion of danger as worthy of consideration at the local level in his work on Uzbekistan. He cites the dominant academic discussions of danger in the realist “international relations literature, where it is commonly discussed in terms of challenges to the ‘security’ or survival of a state” (Megoran Citation2005, 558). In contrast, the main position articulated by critical geopolitics is that danger should “be considered a subjective and politicized exercise rather than an objective assessment” (Megoran Citation2005, 559). Dalby argues that “the mobilization of ‘discourses of danger’” gives authority to the state “as the providers of protection, or ‘security’” (Dalby Citation1993, 439). Furthermore, he suggests that “threats” are spatialized relative to their proximity to a given state, with closer threats being “portrayed” as more dangerous while those further away are constructed as “less dangerous.” However, Dalby qualifies that intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and the political and economic forces of globalization have “complicated” this model (Dalby Citation1993).

In his work on the Finnish–Russian border, Paasi has theorized that the idea of threat to territorial sovereignty is “inextricably bound” with national “identity formation” (Paasi 1996; paraphrased from Megoran 2005, 559–560). As the previous section illustrates, identity in the northern Israeli borderland is too heterogeneous and complicated to suggest a monolithic national identity or positive identification with the state in binary opposition to Lebanon as a dangerous “Other,” particularly among Arabs and Druze. However, safety and security is demanded from the state from both the Jewish majority and minority groups through the language of citizens’ rights and state responsibility (Mossawa Center Citation2006).

The landscape of Israel's border with Lebanon is proliferated by the materialities of security. The area contains a network of radar installations, military bases, fences, patrol roads, soldiers with guns, armoured vehicles, hidden air raid sirens and bomb shelters. Furthermore, the materialities and bodily practices of security even penetrate within the private sphere of the home. Water security is kept in mind when saving any unused drinking water or putting buckets in the shower to save the water that would be wasted while it is warming up to be used for cleaning or watering plants. Another example is that Israeli law requires the inclusion of a “bombproof” reinforced concrete room in every house.

The most overt security threat faced by civilians in the North is rocket fire from Hezbollah militants and other factions based in southern Lebanon. The bulk of the projectiles fired throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the 2006 war and occasionally after that conflict are the short-range 122 mm Grad “Katyusha” rockets based on a Soviet design with a maximum range of 25 km. The advantages of these rockets for militants are that they are inexpensive, easy to stockpile and conceal due to their relatively small size and they can be prepared and fired very quickly from mobile launchers, making it hard for the Israeli Air Force to identify and neutralize launch sites. Due to their “lack of a guidance system” Katyushas are extremely inaccurate and have the most impact when fired in volleys (Gardner Citation2006).

Discourses about Katyushas are tied to their physical properties. A report by the American think-tank The Jamestown Foundation suggests that by “firing Katyusha-type rockets singly … Hezbollah has forgone the tactical use of this weapon for strategic purposes” instead using them as “political” weapons in “media warfare” as acts of “defiance” that “signal to the Arab world that Israel is not invincible” (McGregor Citation2006). Hezbollah also combined rocket fire with “psychological operations” within Israel to influence public opinion towards its goals. It used the communications equipment of its Al-Manar network to broadcast television messages targeted at Israeli audiences “complete with Hebrew subtitles calling on them to go back to Europe and the United States” (McGregor Citation2006, 15). Schleifer argues that “these transmissions … [sought] to create in the Israeli mind a frightening connection between Al-Manar's ability to target their televisions sets and Hezbollah's ability to shell their homes” (McGregor Citation2006, 15). Hezbollah also cited its ability to continue firing rockets at Israel, despite heavy bombardment and a ground invasion by the well-equipped and highly trained IDF, as proof of its “victory” in the 2006 war. This ability had as much to do with the compactness, portability and operational efficiency of the rockets as it did the determination or martial prowess of the fighters who used them. These nonconventional uses of both missiles and communications technologies to circumvent the border fence and the impact for those on the other side support Elden's call to move towards a “volumetric” understanding of territory that “goes up and down” rather than “just exist[ing] as a surface” (Elden Citation2013, 49).

Because they are unguided, inaccurate by design and are launched at an area with a high Arab population, a moral condemnation was voiced by informants, and hinted at in newspaper reports, that they indiscriminately harm both Jews and Arabs. This accusation is intended to refute Hezbollah's public claim to represent broader Arab interests, in addition to Shiite ones, in the region against Israel. One informant recounted the story of three Arab youths from Tarshiha, who were killed when driving near the town. In response to another instance, a 2011 article on Ynet, the online outlet of centre-left Israeli daily Yedioth Ahronoth, used the headline “Lebanese woman hit by Katyusha” for an article describing how a misfired rocket directed at Israel landed on an apartment block inside Lebanon to draw attention to the fact that rocket attacks also harm the antagonists’ own compatriots (Ynet News Citation2011).

An editorial piece by a security analyst in the right-leaning English language daily The Jerusalem Post about the most recent rocket attack to hit Israel in late 2011, explicates the discursive use of weapons as a form of communication in the absence of verbal dialogue. The author cites Hezbollah's restraint considering its “capability to simultaneously launch hundreds of rockets as far south as the city of Dimona at nearly a moment's notice” to argue that rocket fire from Lebanon is always a calculated action permitted by Hezbollah and “its backers in Iran and Syria,” sometimes using Sunni and Palestinian militant groups as proxies (Nisman Citation2011). He also argues that these incidents are not isolated, but rather contingent on contemporaneous events in the Middle East, including those involving the Palestinians. A worded articulation of the most recent flare-up, including Israel's characteristic response of “symbolic artillery barrages in open areas,” is:

that the Iranians and Syrians wanted to warn the state of Israel that operations to undermine Iranian or Syrian aspirations will not go unchecked. Israel's limited response, as well, was meant to send a message that it will retaliate for any provocation, but yet does not seek a major conflict. (Nisman Citation2011)

This analysis both exemplifies the power of weapons to articulate discourse, in lieu of speech acts, and the view of their use in the Israeli–Lebanese conflict as a clever form of gamesmanship in the realpolitik outlook of dominant Israeli security discourses.

The combined factors of the proximity of the northern border to Lebanon, and Hezbollah and allied militant groups’ predilection for Katyushas, gives the region a reputation as a home front under siege within Israeli public discourse and in the media. Civilian experiences play a prominent role in articles from two of three Israeli newspapers reporting on the same rocket attack discussed above. While both articles from The Jerusalem Post focused on the regional implications and focused on “elite” international relations discourses (Lappin and Katz Citation2011; Nisman Citation2011), the articles from Ynet and the left-wing daily Haaretz both discussed the human concerns, although in slightly different ways.

The Haaretz article used a quote from a local civic official to highlight a “business as usual” attitude that valorized an Israeli cultural trait of “toughness” in the face of terror. It also added a critique of the retaliatory imperative of “elite” security actors by paraphrasing the same official as saying “Israel's defense establishment should carefully weigh its options following the rocket fire,” as well as advocating for the implementation of the Iron Dome rocket interception system in the North (Ashkenazi, Khoury, and Harel Citation2011). In contrast, Ynet spent the latter half of its article emphasizing the traumatic effect of the incident for local residents. One resident is quoted as saying “[my] entire village is in shock” and another is written about describing “a mushroom cloud billowing in the sky followed by the thick smell of gunpowder. ‘It was 20 meters from my house,’ he added” (Buchnik Citation2011).

This section has demonstrated how danger is related to both proximity and national identity at Israel's northern border. The closeness of the area to Hezbollah's southern Lebanese heartland creates a sense of threat for border residents, while at the same time a “keep calm and carry on” attitude seeks to normalize this danger in order to perpetuate an image of stoicism and brave resilience that feature in Israeli narratives of national character. However, these two ways of thinking and acting in response to the specific aspect of danger cannot adequately account for the complexity of geographical imaginations at the border. The incompleteness of a border view solely predicated on threat can be partially explained by the fluidity and lack of absolute difference inherent to the borderland concept.

A hostile imagination?

The borderland can be theorized as a “place of contact, confluence and hybridity” (Popescu Citation2012, 80), although caution should be used against suggesting that these identities are necessarily fluid and coherent. Saada-Ophir writes that “this new perspective presents the borderland as an evasive space of interwoven entities, emerging through ongoing negotiations between state policies, such as border patrols, checkpoints, and containment walls, and the agency of those residing there” (Saada-Ophir Citation2006, 206–207). The “evasiveness” of the border can be evinced by the multiple, fragmented entities that are tactically performed in different ways in different contexts as means of “making do” (Certeau Citation1984, 29–30).

Despite the material threat faced by the northern border's residents from sporadic bouts of rocket fire from Lebanon, this does not lead to a Manichaean imagination of Lebanon as a dangerous Other. Rather, both border residents and the Israeli political establishment tend to identify Hezbollah as a primary threat, rather than the Lebanese state. This is evidenced in the repeated discussion of “Hezbollah” as an antagonist rather than “Lebanon” in the newspaper discourse analysis conducted in the previous section. Furthermore, my informants discussed Hezbollah as a direct threat rather than Lebanon. For example, one informant described feeling threatened by a Hezbollah flag that was visible from a farm across the border fence. Another informant, Avi, a 25-year-old former conscript in the IDF who was stationed in the Shebaa Farms area along the border, described the danger of ambush from Hezbollah fighters as the main threat he faced, rather than Lebanese government forces.

In fact, my research suggests that one of the most prominent cultural imaginations at work concerning Lebanon is indifference. Residents of the areas I observed were more interested with going about their day-to-day business and were able to do so by ignoring danger from across the border. Furthermore, most of the people I spoke to did not view Lebanon or Lebanese people diametrically in malignant terms as “the enemy.” Moshe, a Jewish small business owner from Maalot in his 40s, epitomized this attitude when asked what he thought about Lebanese people (in the context of the conflict between Israel and Lebanon):

I'm not worried. If I have to worry, they have to too. They're just like me. They don't want to put up with the same shit. It's the governments who are worried.

Moshe's reply explicitly rejects the “elite” discourse of the state which classifies Lebanon as an “enemy.” His statement also conveys an empathy with the position of the supposed “Other” that contradicts the binary “geographical imagination” posited by Gregory.

The complexity of border identities is also evinced by the positive imaginations that work alongside the indifferent and “dangerous” cultural imaginations of Lebanon. During my research I was able to identify several recurring motifs in how Lebanon was imagined by my informants. One is that Lebanon is more cosmopolitan and “westernized” than other Middle Eastern countries. This is congruous with the well circulated aphorism in Europe that Beirut is “the Paris of the Middle East,” and implies that the Lebanese worldview is less threatening than other Middle Eastern countries, such as Saudi Arabia or Iran, where Islamic fundamentalism is perceived to be the dominant outlook. Tourism was another theme that came up in terms of future possibility. Avi, the informant described above, when asked what he thought about Lebanon, discussed wanting to visit Lebanon to go skiing. He elaborated by saying it was supposed to be a great location for the sport and that many Europeans had holiday homes in the Lebanese mountains. The positive futurity of his answer suggests that tourism could be deciphered as a metonym for peace between the two states.

Stokes notes that the “non-verbal domain” is a vital “cultural resource in the management of border lives” since it is where “people are often able to embrace notions of hybridity and plurality which are often unsayable” (Stokes Citation1998, 264). Within this non-verbal domain the material and symbolic engagement that occurs through the consumption of food and drink can in a commodified setting can be “reshaped” to the “advantage” of marginal groups and that a “more complex view of commodification acknowledges the many ways in which objects become ‘entangled’ in a web of wider social relations and meanings” (Jackson Citation1999, 101).

In the Druze village of Hurfeish mentioned previously, which is a fifteen-minute drive from Maalot, the highly conspicuous symbols of flags are used publicly in commercial spaces to express a complicated projection of Druze identity. The main concentration of shops and restaurants are located along Route 89, the main thoroughfare that bisects the village. Israeli flags and a few five-coloured Druze flags are visible in front of many of the shops and houses near the highway and on the hills ascending from the highway. One of the village's main draws are the several restaurants serving the Druze specialty sambusek, a filled flatbread served with locally produced olives. In one such restaurant I ate at, there were pennants with Israeli flags strung from the ceiling. Another sambusek restaurant visible from the highway flew an Israeli flag flanked by two Druze flags on the outside signage, which also used as its logo a cedar tree, an iconographic metonym for Lebanon. The glass front of the restaurant, shown in , had an Israeli flag and a Lebanese flag on opposite sides. This indicates both the Druze assertion of their unique identity, as well as their claim for recognition as part of the greater Israeli. The inclusion of the Lebanese flag and the “cedar of Lebanon” in this arrangement also proclaims Hurfeish's Druze population's cultural ties to Lebanon.Footnote4

Figure 2. Israeli and Lebanese Flags Displayed at a Sambusek Restaurant in the Village of Hurfeish. Source: the author.

This juggling of three identities, one of which links to Lebanon, which is technically at war with the Israeli state, highlights the precarious and seemingly contradictory ways identity is negotiated and performed at the border in order to make a “liveable” space. Although Druze theology requires political loyalty to the state that a Druze population inhabits, Maher writes that as a culture:

The Druze community of Israel at present suffers doubts as to their identity and political orientation. Not Jewish enough to be totally assimilated by the Jewish state, Muslim enough to be Arab Muslim or Christian enough to claim deep kinship with the Arab Christian “minority of a minority,” the true Druze “state” is a borderless entity, with outposts in Syria and Lebanon. (Maher Citation2009, 423)

In the geographical literature the consumption of ethnically different foods and products, and by extension their symbolic value, has been typically analyzed in terms of cosmopolitanism as a function of spatial distance (e.g. Jackson Citation1999). However, in the present case, the consumption of Lebanese foods should be examined as an integral aspect of spatial nearness to Lebanon and the heterogeneity of the borderland. The plethora of Lebanese restaurants and food stands in the border region, as well as the availability of food and drink associated with Lebanon (although not actually produced in Lebanon due to the closed border), indicates a form of cultural commodification and consumption of Lebanon as an idea. For the mainly Druze, Muslim or Christian owners of these food outlets such deployment of commodified representations can be both an economic tactic, and a means of asserting their Israeli-Lebanese border identity within the public sphere.

Conclusion

In the area proximate to the Blue Line, the spatial practices of security at the border are hermetic, while oppositely, everyday practices and occasional military activity elide this clear division of space. The security constructions and practices that materialize this border are salient as a process to manage the circumnavigating ballistics of rockets and periodic ground incursions by Hezbollah, Palestinian militant groups and the IDF. The treatment of danger by inhabitants of the border region alternates between the experience of fear and the normalization of threat and the materialities of security. While a persistent sense of threat does shape attitudes to security, at the same time this sense of threat is tempered to make daily life livable through a calculated obliviousness to the proliferation of military technology and the volatile potential for political violence to erupt.

This convolutedness also extends to the ambivalent relationship between security and identity at this border. Instead of basing security and military activity on a geographical imagination of binary difference, the spatial proximity of the borderland and the lack of a distinct cultural border in contrast to the discrete physical demarcation between Israel and Lebanon indicate a non-essentialist relationship between security and identity. This ambiguity is manifested through ambivalent and positive cultural imaginings of Lebanon, rather than an imagination based solely on enmity and a desire to recapitulate the grand political narratives of the state. This does not naively imply that the predictable imaginations of threat from Hezbollah are not salient, as the “Security and Threat” section demonstrates, rather that contrasting ideas of Lebanon are simultaneously at work, complicating the unity of border residents’ geographical imaginations. An interesting question in response to this research's call for specificity is to ask what would be the outcome if a similar project were repeated on the Lebanese side of the fence? This question is especially penetrating considering the Shiite community's support of Hezbollah in Southern Lebanon.

Barry recommends that for political research “the case or the field should never be considered as an example which merely illustrates or applies established theoretical principles; it should tell us something new that makes application difficult or problematic” (Barry Citation2013, 417). This article has used such an approach to examine how the complex, ambivalent and contradictory processes that make up Israel's border with Lebanon problematize dominant concepts within political geography. In doing so, it has demonstrated that as a case study this particular border does not fit neatly with an understanding of the border as a signifier of absolute difference, nor does it corroborate the recent theoretical positions about contemporary borders becoming deterritorialized and reterritorialized as a result of globalization. Rather it is a location that is both spatially reified and territorially secured, while simultaneously remaining permeable in ways that generate both immanent potential for social change and danger. This convoluted and somewhat paradoxical finding demonstrates the need for the inductive study of places based on their unique historical, cultural, political and sociological trajectories in order to nuance and reshape existing theories, or if necessary to develop entirely new paradigms that can better relate the observed phenomena to empirical evidence from other categorically related sites.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Dr Ian Klinke in preparing this research for publication. The author would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful critiques.

ORCID

Ian Slesinger http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9802-8938

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In the Israeli case, according to Yiftachel (Citation1998), this hegemonic elite is the Ashkenazi Jews. There are two main ethno-cultural branches of the Jewish people, Ashkenazi and Mizrahi, or Sephardi. Ashkenazi Jews were endemic to Northern and Eastern Europe, while Mizrahi Jews came from Southern Europe, North Africa, the Middle East and the Caucuses. Social and historical research on Israel shows a tendency of political domination, cultural elitism and discrimination by an Ashkenazi “elite” over Mizrahi Jews although conditions are becoming more egalitarian.

2. Bibi is a commonly used nickname for Netanyahu in the press and in public discourse.

3. The “common wisdom” in Israel is that Druze leaders in the 1950s requested conscription out of patriotic duty and to facilitate Druze integration into Israeli society. However, recent scholarship has suggested that this decision was contentious and resulted from factionalism among the Druze leadership along with an element of coercion by the state (Cohen Citation2010, 159–161).

4. A caveat should be noted that Druze political views within Israel are in no way homogenous or unified. Druze MKs in the Knesset at the time of writing ranged across the political spectrum from the Arab interest left-wing Balad party to the centrist Kadima party to the ultra-nationalist Yisrael Beiteinu party.

References

- Ahn, Ilsup. 2010. Deconstructing the DMZ: Derrida, Levinas and the Phenomenology of Peace. Cooperation and Conflict 45, no. 2: 205–223. doi: 10.1177/0010836710370249

- Ashkenazi, Eli, Jack Khoury, and Amos Harel. 2011. Al-Qaida Linked Group Claims Responsibility for Katyusha Fire against Israel. Haaretz. Tel Aviv. http://www.haaretz.com/news/diplomacy-defense/al-qaida-linked-group-claims-responsibility-for-katyusha-fire-against-israel-1.398495.

- Barry, Andrew. 2013. The Translation Zone: Between Actor-Network Theory and International Relations. Millennium – Journal of International Studies 41, no. 3: 413–429. doi: 10.1177/0305829813481007

- Buchnik, Maor. 2011. UNIFIL to Probe Katyusha Fire at Western Galilee. Ynet News. Tel Aviv. http://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-4154458,00.html.

- Certeau, Michel de. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Cohen, Hillel. 2010. Good Arabs : The Israeli Security Agencies and the Israeli Arabs, 1948–1967. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Dalby, Simon. 1993. The ‘Kiwi Disease’: Geopolitical Discourse in Aotearoa/New Zealand and the South Pacific. Political Geography 12, no. 5: 437–456. doi: 10.1016/0962-6298(93)90012-V

- Diener, Alexander C., and Joshua Hagen. 2009. Theorizing Borders in a ‘Borderless World’: Globalization, Territory and Identity. Geography Compass 3, no. 3: 1196–1216. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-8198.2009.00230.x

- Dittmer, Jason, and Nicholas Gray. 2010. Popular Geopolitics 2.0: Towards New Methodologies of the Everyday. Geography Compass 4, no. 11: 1664–1677. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-8198.2010.00399.x

- Elden, Stuart. 2013. Secure the Volume: Vertical Geopolitics and the Depth of Power. Political Geography 34, no. 1: 35–51. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2012.12.009

- Eyles, John. 1988. Interpreting the Geographical World: Qualitative Approaches in Geographical Research. In Qualitative Methods in Human Geography, ed. J. Eyles and D.M. Smith, 1–16. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Falah, Ghazi. 1989. Israeli ‘Judaization’ Policy in Galilee and Its Impact on Local Arab Urbanization. Political Geography Quarterly 8, no. 3: 229–253. doi: 10.1016/0260-9827(89)90040-2

- Fowler, R. 1991. Language in the News: Discourse and Ideology in the Press. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Fraser, T. G. 2004. The Arab-Israeli Conflict. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gardner, Frank. 2006. Hezbollah Missile Threat Assessed. BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/5242566.stm.

- Gil-Har, Yitzhak. 2000. Boundaries Delimitation: Palestine and Trans-Jordan. Middle Eastern Studies 36, no. 1: 68–81. doi: 10.1080/00263200008701297

- Golub, John E. 2009. The Galilee, Israel: Self-Evaluation Report. OECD Reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development, IMHE. http://www.oecd.org/edu/imhe/reviewofhighereducationinregionalandcitydevelopment2008–10thegalileeisrael.htm.

- Gregory, Derek. 2004. The Colonial Present: Afghanistan, Palestine, and Iraq. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Jackson, Peter. 1999. Commodity Cultures: The Traffic in Things. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 24, no. 1: 95–108. doi: 10.1111/j.0020-2754.1999.00095.x

- Kaufman, Asher. 2006. Between Palestine and Lebanon: Seven Shi'i Villages as a Case Study of Boundaries, Identities, and Conflict. Middle East Journal 60, no. 4: 685–706.

- Kipnis, Baruch. 1984. Role and Timing of Complementary Objectives of a Regional Policy, the Case of Northern Israel. Geoforum 15, no. 2: 191–200. doi: 10.1016/0016-7185(84)90031-9

- Lappin, Yaakov, and Yaakov Katz. 2011. Lebanese Rockets – an Indirect Message? Jerusalem Post, Jerusalem. http://www.jpost.com/Defense/Article.aspx?id=247355.

- Leibovitz, Liel. 2011. Moving On. Tablet Magazine. http://www.tabletmag.com/jewish-news-and-politics/80664/moving-on.

- Maher, John. 2009. Between Israel and Lebanon: The Druze Intifawda of October 2007. Israel Affairs 15, no. 4. 413–426.

- McGregor, Andrew. 2006. Hezbollah's Rocket Strategy. Terrorism Monitor. Washington, DC: The Jamestown Foundation. http://www.jamestown.org/programs/gta/single/?tx_ttnews[tt_news]=869&tx_ttnews[backPid]=181&no_cache=1.

- Megoran, Nick. 2005. The Critical Geopolitics of Danger in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 23, no. 4: 555–580. doi: 10.1068/d56j

- Megoran, Nick. 2011. Rethinking the Study of International Boundaries: A Biography of the Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan Boundary. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 102, no. 2: 464–281. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2011.595969

- Mossawa Center. 2006. The Arab Citizens of Israel and the 2006 War in Lebanon: Reflections and Realities. Haifa: Mossawa Center. http://www.mossawa.org/files/files/File/Reports/2006/TheArabCitizensofIsraelandthe2006WarinLebanon.pdf.

- Müller, Martin. 2009. Making Great Power Identities in Russia: An Ethnographic Discourse Analysis of Education at a Russian Elite University. Berlin: Lit Verlag.

- Newman, David. 1989. Civilian and Military Presence as Strategies of Territorial Control: The Arab-Israel Conflict. Political Geography Quarterly 8, no. 3: 215–227. doi: 10.1016/0260-9827(89)90039-6

- Newman, David. 2006. The Lines That Continue to Separate Us: Borders in Our ‘Borderless’ World. Progress in Human Geography 30, no. 2: 143–161. doi: 10.1191/0309132506ph599xx

- Nisman, Daniel. 2011. Northern Border: Rocket Attacks Are a Sign of the Times. The Jerusalem Post, Jerusalem. http://www.jpost.com/Opinion/Op-EdContributors/Article.aspx?id=247650.

- Ó Tuathail, Gearóid. 1998. Political Geography III: Dealing with Deterritorialization. Progress in Human Geography 22, no. 1: 81–93. doi: 10.1191/030913298673827642

- Ó Tuathail, Gearóid. 1999. Borderless Worlds? Problematising Discourses of Deterritorialisation. Geopolitics 4, no. 2. Routledge: 139–154. doi: 10.1080/14650049908407644

- Ó Tuathail, Gearóid. 2008. Derek Gregory's The Colonial Present (Book Review), Political Geography 27, no. 3, 339–343.

- O'Shea, Brendan. 2004. Lebanon's ‘Blue Line’: A New International Border or Just another Cease-Fire Zone? Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 27, no. 1: 19–30. doi: 10.1080/10576100490262124

- Paasi, Anssi. 1998. Boundaries as Social Processes: Territoriality in the World of Flows. Geopolitics 3, no. 1: 69–88. doi: 10.1080/14650049808407608

- Paasi, Anssi. 1999. Boundaries as Social Practice and Discourse: The Finnish–Russian Border. Regional Studies 33, no. 7: 37–41. doi: 10.1080/00343409950078701

- Popescu, Gabriel. 2012. Bordering and Ordering the Twenty-First Century : Understanding Borders. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. [Kindle Edition]

- Saada-Ophir, Galit. 2006. Borderland Pop: Arab Jewish Musicians and the Politics of Performance. Cultural Anthropology 21, no. 2: 205–233. doi: 10.1525/can.2006.21.2.205

- Said, Edward. 1979. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books.

- Schleifer, Ron. 2006. Psychological Operations: A New Variation on an Age Old Art: Hezbollah versus Israel. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 29, no. 1: 1–19. doi: 10.1080/10576100500351185

- Shmueli, Deborah, and Baruch Kipnis. 1998. Participatory Planning and Ethnic Interaction in Ma'alot–Tarshiha, a Jewish–Arab Community. Applied Geography 18, no. 3: 225–241. doi: 10.1016/S0143-6228(98)00016-2

- Soffer, Arnon, and Julian V. Minghi. 1986. Israel's Security Landscapes: The Impact of Military Considerations on Land Uses. The Professional Geographer 38, no. 1: 28–41. doi: 10.1111/j.0033-0124.1986.00028.x

- Sparke, Matthew B. 2006. A Neoliberal Nexus: Economy, Security and the Biopolitics of Citizenship on the Border. Political Geography 25, no. 2: 151–180. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2005.10.002

- Stokes, Martin. 1998. Imagining ‘the South’: Hybridity, Heterotopias and Arabesk on the Turkish-Syrian Border. In Border Identities: Nation and State at International Frontiers, ed. Thomas M. Wilson and Hastings Donnan, 263–288. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tzfadia, Erez. 2006. Public Housing as Control: Spatial Policy of Settling Immigrants in Israeli Development Towns. Housing Studies 21, no. 4: 523–537. doi: 10.1080/02673030600709058

- Van Houtum, Henk, and Ton van Naerssen. 2002. Bordering, Ordering and Othering. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 93, no. 2: 125–136. doi: 10.1111/1467-9663.00189

- Walters, W. 2006. Border/Control. European Journal of Social Theory 9, no. 2: 187–203. doi: 10.1177/1368431006063332

- Yiftachel, Oren. 1997. Nation-Building or Ethnic Fragmentation? Frontier Settlement and Collective Identities in Israel. Space and Polity 1, no. 2: 149–169. doi: 10.1080/13562579708721761

- Yiftachel, Oren. 1998. Nation-Building and the Division of Space: Ashkenazi Domination in the Israeli ‘Ethnocracy’. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 4, no. 3: 33–58. doi: 10.1080/13537119808428537

- Yiftachel, Oren. 2001. The Consequences of Planning Control: Mizrahi Jews in Israel's Development Towns. In The Power of Planning: Spaces of Control and Transformation, ed. Oren Yiftachel, Jo Little, David Hedgcock, and Ian Alexander, 117–134. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Yiftachel, Oren. 2008. (Un)Settling Colonial Presents. Political Geography 27, no. 3: 364–370. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2008.01.005

- Yiftachel, Oren, and Avinoam Meir. 1996. Ethnic Frontiers and Peripheries: Landscapes of Development and Inequality in Israel. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Ynet News. 2011. Lebanese Woman Hit by Katyusha. Ynet News. http://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-4160264,00.html.