ABSTRACT

Approximately 65% of the organizations in the United States have fallen victim to a successful phishing attack. Many organizations offer anti-phishing training to their employees to defend against phishing attacks. The purpose of this study is to examine factors impacting the effectiveness of anti-phishing training and study the relationship between personality traits and phishing susceptibility. Participants filled out pre- and post-training surveys that included questions on identifying phishing and legitimate URLs and questions to determine DISC (Dominant, Influence, Steadiness, and Conscientiousness) personality traits. An analysis of the survey data shows that the participants’ average accuracy in detecting phishing URLs increased 8% (t = 2.144, p-value = 0.0374) and their confidence in their answer choices increased 6% (t = 2.032, p-value = 0.0464) from pre-training to post-training surveys. Before and after training, participants with the Influence personality trait had the lowest susceptibility while both Dominant and Steadiness personalities had the highest susceptibility before and after training respectively.

1. Introduction

In today’s society, information and communication technology such as cellular phones, e-mails, Internet, laptops/workstations, phone applications, voice assistants (Siri, Alexa, etc.), etc. has become essential, particularly for businesses. This has enabled cyber criminals to easily exploit the security’s “weakest link” – the human element.Citation1–3 Such attacks are often accomplished through social engineering, which is the process of getting a person to complete a service or task that may cause the victim to unknowingly give away private and/or confidential information.Citation4 As more and more cyber criminals rely on social engineering techniques, it is imperative that organizations utilize efficient training programs. Social engineering attacks are not new; however, as more technical experience is required for cyber criminals to launch attacks, many are falling back on social engineering.Citation5

Phishing is the most common type of social engineering attack.Citation6 Phishing involves an attacker – known as a phisher – posing as a trustworthy source in an attempt to have the victim release personal or private information.Citation7 Phishers frequently pretend to be companies like eBay, PayPal, and various banking organizations in order to trick and deceive individuals into giving them information. These phishing deceptions can come in the form of e-mails or entire websites and have the ability to target large amounts of people en masse.

During the early days of phishing, phishing attacks rapidly grew in number due to the use of online do-it-yourself phishing kits and other similar factors.Citation8,Citation9 In 2017, more than 7,700 organizations were targeted by business e-mail compromise scams. The targeted organizations were attacked, on average, around five times throughout the year.Citation10 It is difficult to calculate just how much damage phishing attacks cost annually due to the number of unreported attacks; however, researchers have estimated that phishing attack costs could be anywhere from 61 USD million to 3 USD billion per year in the United States.Citation11 This does not include the costs of indirect damage to reputation, recovery measures, and other affected areas for companies.

Mitigating phishing attacks has long been a challenge in cybersecurity. There are three key aspects of phishing mitigation – detection of the attack, educating and training employees, and determining user susceptibility.Citation12 Detecting phishing attacks can be automatic or manual. Automatic methods are generally browser tools designed to block phishing websites. Many of the anti-phishing browser tools only block websites that appear on a blacklist and take no further consideration. A study reported that the highest accuracy produced by one of the tools was over 90%; however, the tool also falsely identified 42% of the legitimate websites as phishing websites.Citation13 Because of such results, manual detection methods like the social engineering attack detection model created in 2015 by Mouton et al.Citation14 were promoted. However, expecting users to detect phishing attacks requires them to be educated and trained on these malicious attacks.

Education and training programs are the most common method of informing and teaching employees about phishing attacks and phishing prevention. However, in a study by Douglas Twitchell,Citation5 it appears that the majority of cybersecurity education and training programs do not discuss phishing attacks, let alone social engineering. Of the programs that discuss social engineering, only half of them mention prevention techniques. A university in the United States, henceforth referred to as “The University,” recently adopted a new security training program – KnowBe4 – in an attempt to offer education and training of employees, especially on topics of phishing. KnowBe4 is a web-based security training program that utilizes simulations, interactive security modules/activities, and newsletters, along with several other services. Jocelyn Sloan, MCS investigated phishing mitigation solutions for small and medium sized businesses and found that KnowBe4, as well as other software as a service products, can be affordable solutions.Citation15 KnowBe4 also grants the ability to make personalized training modules to create perpetual assessments and perpetual security training/education sessions. Personalization comes in the form of being able to choose and select different types of training modules for different training sessions, which highlights one of the benefits of the KnowBe4 training program. In addition to the discussion of social engineering and phishing attacks, KnowBe4 also has the capability to provide short-term and long-term retention options. If the education and training programs are designed to provide participants’ training results immediately after receiving the information, it is short-term retention. However, KnowBe4 has the option to produce new training results for participants weeks or months after their initial training by supplying fake phishing attacks and other options. This shows how long participants retain the information learned during the training.

For this research, we focus on the anti-phishing training of KnowBe4. At the time of this study, The University had chosen to create their training using four modules. The first module is a combination of The University’s Information Security Policy and their Acceptable Use Policy. In this module, participants will be presented a recorded slide show detailing both policies. An example of the information covered in this section includes the different levels of confidential data and examples of each level for better understanding. Next up is the Common Threats module. The common threats module is a series of interactive videos for the participant to watch. This module discusses social engineering and phishing attacks and provides participants with valuable definitions regarding threats and security features. Participants must complete a quiz on the information and pass with at least an 80% to finish the module. The third module is the KnowBe4 Security Awareness Fundamentals Training. This module focuses on enhancing participants’ risk perception, awareness, and response. Participants are given information on phishing and other social engineering attacks, incident response, good security behaviors, and more. After exploring the information, participants must pass a quiz on the section with a score of at least 80% to complete the training. For all quizzes, if a participant does not score at least 80%, they must retake the quiz. The last module is Spot the Phish, where participants are given different scenarios and must spot the difference between the phishing scenarios and the legitimate scenarios. The scenarios may have different phishing or other social engineering features that participants must identify.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of the anti-phishing training program and to examine user susceptibility to phishing attacks. The following two research questions are addressed in this study: (1) To what extent does the KnowBe4 training program impact participants’ knowledge, behavior, perceived risk, and performance associated with identifying phishing attacks? (2) To what extent do participants’ demographics and personality traits impact the effectiveness of the KnowB4 training program? This study tests the following three hypotheses: (1) The KnowBe4 training program improves participants’ self-reported phishing knowledge, behavior tendencies, and perceived risk; (2) Participants are able to identify phishing attacks at a higher accuracy after completing the KnowBe4 training; and (3) Participant’s demographics and personality traits will not have a significant impact on the effectiveness of the KnowBe4 training program.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides information on the demographics obtained and personality assessment utilized in the study. Section 3 focuses on related research associated with the topic. Section 4 discusses the methodology behind our research, including the survey. Section 5 discusses the results of the study. Section 6 discusses the limitations of this study and section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Background

2.1. Demographics and the DISC personality assessment

This research evaluates the effects of user demographics and personality traits on the effectiveness of a phishing security training program. The demographic information collected from each participant included age, gender, race/ethnicity, years of experience, education, department, and work status (full-time, part-time, student). In order to determine personality traits, participants were required to complete a personality test based on the DISC (Dominant, Influence, Steadiness, and Conscientiousness) personality assessment.Citation16

Creation of the DISC Assessment is primarily credited to William Marston, an American physiological psychologist.Citation17 According to Jones and Hartley,Citation17 Carl Jung laid the original groundwork for how a person’s “psychological make-up ‘temperament,’ ‘style,’ or ‘type’” can impact choices they make – based on the work of Hippocrates. In creating the DISC Assessment, Marston was focused on improving human relationships. The assessment Marston created determines which of the four personality traits (i.e., Dominant, Influence, Steadiness, and Conscientiousness) a user most exemplifies.

People who display the Dominant personality trait as their primary personality are known for being outgoing and task-oriented. Additionally, Dominant individuals are also categorized as leaders, fearless, bold, and daring. People who display the Influence personality trait as their primary personality are known for being outgoing and people-oriented. This type of person is also found to be sociable, entertaining, and talkative. People who display the Steadiness personality trait as their primary personality are known for being reserved and people-oriented. Individuals with this primary trait also tend to be generous, loyal, patient, and calm. Finally, people who display the Conscientiousness personality trait as their primary personality are known for being reserved and task-oriented. Conscientious individuals are typically found to be calm, private, shy, and agreeable.

The DISC assessment was chosen because it “measures surface [personality] traits and is intended to explain how they lead to behavioral differences among individuals.”Citation17 This information is important as we will be able to see how individuals with each personality trait behave after completing the KnowBe4 training. There have been several papers in which phishing and the Big Five personality traits – also known as OCEAN (Openness, Conscientiousness, Extroversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism) were investigated; however, this is the first work utilizing the DISC personality traits in this respect; therefore, this research could provide insights on how the four personality traits identified by this assessment can impact the effectiveness of organizational cybersecurity training programs.

2.2. Technology threat avoidance theory

In 2009, Liang and Xue proposed the Technology Threat Avoidance Theory (TTAT).Citation18 The theory states that a person’s perceived threat susceptibility and perceived threat severity impact their overall perception of the threat. This means that a person’s awareness of their chances to fall victim to a threat and knowledge of the amount of damage the threat could cause to their devices/systems, impacts their ability to determine the true damage that can be caused by a threat. Likewise, a person’s perceived threat, along with safeguard effectiveness, cost, and ease of implementation impact their avoidance motivation. This means that a person’s ability to determine the magnitude of the threat, the effectiveness of available anti-threat tools, the cost (e.g., time, effort, and money) of those tools, and their belief in how well they can handle the threat play a role in how motivated they are to avoid the threat. Finally, a person’s avoidance motivation impacts their avoidance behavior. Meaning their motivation to avoid the threat directly impacts the behaviors they exude to avoid the threat. In summation, the TTAT states that a person’s perceived susceptibility and threat severity to cyber threats affects their awareness of the threats which, in turn, impacts their motivation and behavior to avoid the threats.Citation18,Citation19 The TTAT advocates for recurring cybersecurity education and training programs as over time, people forget what is taught to them. Therefore, to keep users motivated to avoid cyber threats, it is imperative that education and training materials improve a person’s perceived susceptibility and threat severity.

Our first research hypothesis “The KnowBe4 training program improves participants’ self-reported phishing knowledge, behavior tendencies, and perceived risk” is based on the TTAT. The perceived threat susceptibility in TTAT relates to our perceived risk, while perceived threat severity relates to our phishing knowledge, and threat avoidance behaviors relates to our behavioral tendencies.

3. Related works

Several research papers discussed the effectiveness of anti-phishing education and training, as well as phishing related behaviors. Researchers have also conducted studies to discover what types of demographics and personality traits are most susceptible to phishing attacks.

3.1. Effectiveness of anti-phishing education and training programs

In order to improve the amount of information participants retain from education and training programs, researchers have been using games and interactive sessions/materials.Citation20,Citation21 In KnowBe4, Spot the Phish is an example of an anti-phishing interactive training module. Alkhamis and RenaudCitation22 created an interactive training video that helped participants improve their pretest questionnaire scores. Sheng et al.Citation23 created Anti-Phishing Phil, a game for educating people about phishing attacks. In their study, they discovered that participants in their gaming group experienced improved posttest scores and increased confidence in their answers. Kumaraguru et al.Citation24,Citation25 observed a similar result when they used Anti-Phishing Phil and the PhishGuru cartoon. In a 2007 study, Kumaraguru et al.Citation21 discovered that the PhishGuru cartoon also improved participants posttest scores. Three years later, Kumaraguru et al.Citation22 found that between a traditional training methods group, a PhishGuru group, and an Anti-Phishing Phil group, only participants from the Anti-Phishing Phil group were able to receive similar scores on their immediate posttest and their one-week delayed posttest.Citation25

A study conducted at Columbia University (CU) employed an iteration-based ant-phishing training program.Citation26 The researchers sent out four types of phishing e-mails to students, staff, and faculty at CU. They collected e-mail addresses by using a crawler module on the CU directory. If a user fell for a phishing attack, the time the user clicked on a link, their role, and their department were recorded. Phished users were also displayed a message stating that the phishing e-mail was from an experiment conducted at CU and to be aware of suspicious e-mails in the future. Each user who fell for a phishing e-mail was sent another phishing e-mail in the next wave of phishing attacks. It took four iterations before no users fell victim to one of the phishing attacks. However, initially, 19.6% of the staff members targeted fell victim to the phishing attacks compared to 11.6% of the targeted students. The researchers stated that they believe “users can be trained using decoy technology to be cognizant of potential threats.”Citation26

An effective phishing education and training program should also be able to improve a person’s self-perceived risk and susceptibility. For instance, based on the protection motivation theory (PMT) discussed in McBride et al., “when individuals perceive that they are more susceptible to security threats … and when the threats are more severe, they are more likely to adopt a recommended response to the threat.”Citation27 This is further supported in a paper by Johnston and Warkentin in which they discuss how a person’s perceived threat susceptibility and severity impact their self-efficacy and response efficacy.Citation28

3.2. Phishing related behaviors

In 2013, Arachchilage and Love discussed a game design framework to help users avoid phishing attacks and increase the use of safeguard measures.Citation29 Using the TTAT model and relevant research, they created a questionnaire. To begin the study, participants were asked if they knew what phishing attacks were and if not, they were given a definition. The questionnaire contained topics on perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived threat, and safeguard effectiveness, safeguard cost, self-efficacy, avoidance motivation, and avoidance behavior. Using pearson correlation analysis on the results of the questionnaire, they found that perceived threat is significantly determined by perceived susceptibility and severity and is influenced by the interaction between the two factors. Meanwhile, avoidance motivation is significantly determined by perceived threat, safeguard effectiveness, the interaction of these two factors, self-efficacy, and safeguard cost. Finally, avoidance behavior is significantly influenced by avoidance motivation. Using this information, Arachchilage and Love decided to incorporate elements from each topic into the game design framework. It is important to note that unlike other influences, the safeguard cost negatively impacted avoidance motivation. Meaning as the cost to safeguard increases, user motivation to avoid phishing attacks decreases. The researchers plan to further increase their knowledge by designing and evaluating a mobile game.

In 2021, Canham et al.Citation30 investigated phishing related behaviors at a southeastern university in the United States. The focus for this study was on determining employee cluster types for responses to phishing attacks based on positive and negative actions. Participants in this study were sent 20 training phishing e-mails from June 2018 to December 2019. Canham et al. utilized the KnowBe4 platform as the source of the phishing e-mail campaign and sent the messages to over 6,000 faculty and staff. Each employee’s behavior was categorized as either reported or failure. Employee behavior was marked as reported if they reported the phishing e-mail to the appropriate department. Otherwise, employee behavior was marked as failure if the employee clicked on any links in the e-mail, responded to the e-mail, or entered data after clicking the link in the e-mail. It was not stated whether employees that ignored or deleted the e-mails were placed in a group. They found that around 51% of the employees never fell for a phishing attack, while around 44% occasionally fell for an attack (1–3 times), and around 6% repeatedly fell for an attack (4+ times). Using k-means clustering, the researchers noted the development of four clusters – nicknamed Gaffes, Beacons, Spectators, and Gushers. The Gaffes group contained employees who typically clicked on links in the phishing e-mails at a high rate. The Beacons group contained employees who typically did not fall for the phishing e-mails and reported phishing e-mails. The Spectator group is the largest and contained employees who typically did nothing (neither clicked on links at a high rate nor reported phishing e-mails). Finally, the Gusher group contained employees who did not click on links as often as Gaffes but filled out data requested in phishing e-mails at a high rate. Out of 6,126 employees, 344 belonged to the Gaffes, 1,361 belonged to the Beacons, 4,050 belonged to the Spectators, and 371 belonged to the Gushers. Canham et al. noted that security training is “as expected” not perfect as even in the Beacon and Spectator clusters, around 3–4% of the employees fell victim.Citation30

3.3. Demographics and susceptibility

Sheng et al.Citation31 conducted research to study how age and gender affect phishing susceptibility. Results of this study show that women are more likely than men to fall for a phishing attack and people in the age group 18–25 are more likely to fall for phishing than people over the age of 25. However, no strong correlation between education or race and phishing susceptibility were observed from this study. Jagatic et al.Citation7 conducted a study that used social networks to target students at Indiana University with phishing attacks. The phishing attacks overall had a 72% success rate. It was found that 77% of the female participants fell for the phishing attacks compared to 68% of the male participants. Similarly, Alam et al.Citation32 conducted a study that showed a relation between phishing susceptibility and the use of social media. Specifically, the researchers discovered that the amount and quality of information posted online by people in the age group of 18–25 years old could possibly increase their susceptibility to phishing and spear phishing attacks. This could explain why a large number of students fell for phishing attacks in the study conducted by Sheng et al.Citation31 and the success rate experienced in the study by Jagatic et al.Citation7

Mohebzada et al. conducted two phishing experiments on the faculty, staff, students, and alumni of the American University of Sharjah (AUS).Citation33 The first experiment impersonated the IT department and asked users to reset their university account’s password on a fake website. The e-mail was made to look like a legitimate e-mail from the IT department and the link went to a website that had a similar URL to the school’s official website. Out of 10,917 targets, with 10,217 students and alumni and 700 faculty and staff, 954 people fell victim. Of the victims, 485 (50.8%) of the victims were female, 469 (49.2%) were male, 918 (95.8%) were students and alumni, and 36 (3.8%) were faculty and staff. The second experiment ran immediately after the first. This time, the attackers posed as the university’s research office and sent a link out for the victims to complete a survey. The link actually sent the victims to a form on the researchers’ fake website and asked them to fill out personal information and optionally, their banking information. This time, the IT department sent out a warning just 2 hours after the phishing e-mail; however, 98 people still fell victim after the warning. There was a total of 224 people who fell victim to the second attack. Of the 224, 220 (98.2%) were students and alumni and four (1.8%) were faculty and staff. Of the 220 students who responded to the phishing attack, 86 (39.1%) were female and 134 (60.9%) were male. Based on these observations, the researchers noted that gender and age are not conclusive in determining susceptibility to phishing attacks. Anwar et al.Citation34 conducted a study to examine the effect of employment status on user behavior. They created a survey to measure participants’ self-reported cybersecurity behaviors and found that there were statistically significant negative correlations between employment status and perceived vulnerability, prior experience with cybersecurity practices, and computer skills. They concluded that organizations should place emphasis on training part-time employees as they are more susceptible than full-time employees.

3.4. Personality and susceptibility

In 2016, Cho et al.Citation35 conducted a study on the effect of the Big Five personality traits on phishing susceptibility. The results of this study showed that the Agreeableness and Neuroticism personality traits greatly impact how people perceive information in terms of trustworthiness. Consequently, individuals who score high in these two traits tend to be more susceptible to phishing attacks. In another study utilizing the Big Five personality traits, Halevi et al.Citation36 looked into the correlation between phishing, personality traits, and Facebook activity. The participants were asked to complete an online survey where the authors acquired their demographics/background information, online activity, and Facebook related information. Using the e-mail provided from the survey, the authors also sent out a fake phishing e-mail to all participants. Seventeen percent of the participants fell victim to the phishing attack. Fourteen percent of the male population fell victim along with 53% of the female population. In regard to the personality traits, for women, it was found that there was a very high positive correlation between Neuroticism and phishing. However, there were not any correlations found between men and any of the personality traits.

Several researchers have referenced principles of persuasion being used in effective phishing e-mails. Based on the work of Robert Caldini, the most common principles of persuasion are authority, social proof, scarcity, liking/similarity, commitment/consistency, and reciprocation.Citation37–39 However, in terms of phishing e-mails, researchers agree that authority is one of the most effective principles of persuasion.Citation37,Citation39 As it relates to authority, Caldini states “Information coming from a recognized authority can provide us a valuable shortcut for deciding how to act in a situation.”Citation40 In addition, Jones’ and Hartley’sCitation17 research discusses defining adjectives for the DISC traits whereby the adjectives listed for Steadiness include loyal, obedient, and obliging; while those listed for Conscientiousness include compliant, resigned, and well-disciplined. These adjectives can be associated with someone who respects and responds well to authoritative fFigures

4. Methodology

Based on previous work regarding user susceptibility and cyber security education and training, we developed several research questions and hypotheses. Our research questions aim to examine the effectiveness of training programs and how participants’ demographics may impact user susceptibility. Based on previous research, we know that training programs are capable of teaching participants about phishingCitation12,Citation19. However, we also want to know how they impact a person’s ability to mitigate phishing attacks and determine risk. Taking this a step further, we also decided to investigate how a person’s demographics and personality traits impact the training program. Our hypotheses were formulated based on the objectives of the training program and previous studies on user susceptibility. Utilizing the TTAT and the KnowBe4 objectives – recognizing personal risk, demonstrating risk awareness, and taking actions to minimize risk – we developed our first hypothesis stating that the training will improve participants’ self-perceived knowledge, tendencies, and risk. Based on the assumption that security training programs that discuss phishing should decrease user susceptibility, we developed our second hypothesis stating that the training will improve participants’ ability to detect phishing attacks. Finally, based on the results of previous studies that provided conflicting demographic susceptibility results, we developed our last hypothesis stating that the demographics and personality traits will not have a significant impact on the effectiveness of the training.

The pre- and a post-training surveys were developed by adapting questions from relevant previously published studies. For example, questions pertaining to computer skills and perceived risk were adapted from work by Anwar et al.Citation34 By adapting questions from relevant studies, we were able to use vetted survey questions rather than implementing newly created questions that may not be suited for measuring objective related data. In regard to the personality trait portion of the survey, the questions were gathered from online DISC assessments.Citation41 The study protocol received the approval of the IRB by way of an exempted status. The KnowBe4 training used for this research was purchased through a license by The University and was conducted by its IT department. Participants were recruited from The University’s employees who were registered to complete the training through KnowBe4. The link to the pre-training survey was sent out through an e-mail explaining the research and asking for participants. The link to the post-training survey was only sent out to participants who completed the pre-training survey. The training was supposed to be administered to the entire campus faculty and staff; however, due to the coronavirus outbreak, only a portion of the faculty and staff received training, which reduced the participant pool for the post-training survey.

In order to answer the research questions, participants were asked to fill out a survey before and after completing the training. Since participants were able to complete the training on their own terms, they were asked to fill out the post-training survey shortly after completing the training program. This is a practice used in several similar previous studies.Citation3,Citation22,Citation23 The pre-training survey consists of 75 questions split into eight sections while the post-training survey has 56 questions and includes six of the original eight sections. The sections are shown in and the questions from the surveys can be found in Appendix A.

Table 1. Pre and post training survey sections.

The demographics section included questions about gender, race/ethnicity, age, and education. The perceived computer skills section asked about the participant’s self-perceived computer skills. The personality traits section utilized a simple 14 question DISC personality assessment created using specific keywords to describe the traits. The questions for this assessment came from an online DISC assessment.Citation36 In the pre-training survey, the phishing knowledge section was used to gain understanding of the participants’ prior knowledge of phishing attacks. However, in the post-training survey, the phishing knowledge section was used to gain understanding of any new information learned by the participants. For the pre-training survey, the behavioral tendencies section depicts the current positive and negative behaviors of the participant; whereas, in the post-training survey, this information shows which tendencies the participant thinks are important or unimportant for preventing phishing attacks. This section included questions on topics such as opening e-mails from unknown senders and informing the IT department about suspicious e-mails. The perceived risks section assessed participants’ self-perceived risk by asking questions to determine how well the participants believe their work environment is protected/safe against phishing attacks. The phishing identification section consisted of a phishing test where participants were given several phishing and legitimate URLs and were asked to differentiate which URL belongs to which category and their confidence level (based on a Likert scale) in their answer. The participants were never given the answer to a question and were given the same URLs in the pre-training and post-training surveys in order to measure improvement. The scenarios section included five scenario-based short answer questions to determine susceptibility. The purpose of these five questions is to see the thought process behind the participants’ actions in the case of a phishing attack. Both the pre-training and post-training surveys were completed online via an online survey tool software – Qualtrics. A python program was used to extract the data from a csv file generated by Qualtrics and place it into a Pandas data frame. The data frames were traversed to determine any increases/decreases in the participants’ self-perceived categories.

5. Results and discussion

There were 119 responses to the pre-training survey and 33 responses to the post-training survey. Due to a technical error, nine of the responses for the pre-training survey had answers that were omitted when submitting, so those nine responses were not included in the data analysis. There was also one response from the post-training survey data that had an omitted answer; thus, it was not included in the data analysis. These ten responses were only used for examining the overall comparison between the pre- and post-training surveys. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the KnowBe4 training at The University was suspended after a month and a half. At the time this manuscript was written, training had not resumed which prevented the acquisition of more participants.

5.1. Pre and post training accuracy and confidence

The pre- and post-training accuracy in the phishing identification test and their confidence in their answers are presented in , while t-test results are presented in .

Table 2. Pre and post training average accuracy and confidence.

Table 3. Pre and post training accuracy and confidence T-Test.

That data analysis showed that both average accuracy and confidence increased between the pre- and post-training surveys. The accuracy increased around 8% – from 59.524% to 67.677% – while confidence had an increase of around 6% – from 66.653% to 72.828%. This information was further analyzed through a two-sample unequal variance t-test with an alpha level of 0.05. The results of this analysis are a p-value of 0.0374 between the pre- and post-training average accuracies, and a p-value of 0.0464 between the pre- and post-training average confidence levels. A moderate positive correlation (Pearson’s r = 0.4996, p-value = 0.0036) between post-training accuracy and post-training confidence was also found. This confirms the hypothesis that the KnowBe4 training has a positive impact on participants’ performance in identifying phishing attacks.

5.2. Phishing knowledge, behavior, and risk

The data analysis also showed increases in phishing knowledge, behavior, and perceived risk from the pre- to post-training (shown in ). The average for phishing knowledge score increased from 3.63 to 4.25 out of a total of 5.33. The average response for user behavior improved, whereby the average score increased from 2.86 to 3.28 out of a total of 5. The average score for self-perceived risk increased from 5.48 to 5.6 out of a total of 7. A two-sample unequal variance t-test results showed statistically significant differences in pre- to post-training phishing knowledge (t-stat = 4.86, p-value = 0.0000) and user behavior (t-stat = 2.09, p-value = 0.0419).

Table 4. Pre and post training self-perceived value averages.

5.3. Personality traits and accuracy/confidence

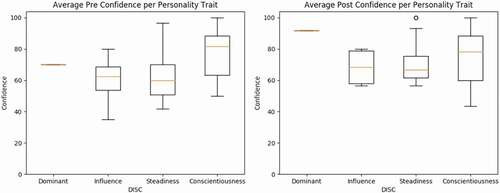

For the rest of the analysis, a one-hot encoding on the Pandas data frame to change each subcategory into a binary value was used first. Then either PB Correlation or Biserial Correlation analyses between each binary subcategory value and the four components of the pre- and post-training data were performed. displays the average accuracy with standard deviation and confidence with standard deviation per personality trait, while contains the PB Correlation coefficients and p-values. Correlations are considered weak if r < 0.4, moderate if 0.4 ≤ r < 0.6, and strong if r ≥ 0.6. A box and whiskers plot of the pre- and post-confidence per personality trait are presented in .

Table 5. Pre and post training personality trait average accuracies and confidence.

Table 6. Personality PB correlation coefficients and P-values.

Due to the limited responses of the post-training survey data, only one participant belonged to the Dominant personality group; therefore, no inferences were made about this data. Four participants belonged to the Influence personality group, eighteen belonged to the Steadiness personality group, and nine belonged to the Conscientiousness personality group. Participants within the Influence (63.89%) and Conscientiousness (63.14%) personality groups had the highest accuracy scores, before training. The Influence group also had the highest accuracy score (81.25%) after training, while the Dominant group had the next highest accuracy score (75%). The Dominant and Conscientiousness groups ranked the highest in average confidence level in their answer choices before training: 72.88% and 72.63%, respectively. The Dominant group had the highest level of confidence in their choices after training with an average confidence level of 91.67%. The most susceptible personality group before training was the Dominant group with the lowest average accuracy of 51.52%. After training, the Steadiness group was the most susceptible with an average accuracy of 65.28%. The Conscientiousness group was not far behind with an average accuracy of 67.59%. In addition to this information, it was also noted that the Dominant group had the largest difference between pre- and post-training data followed by the Influence, Steadiness, and Conscientiousness groups. Significant correlations were found in participants’ confidence levels for both the Steadiness and Conscientiousness groups. For instance, there was a weak negative correlation between the Steadiness group and the participants’ pre-training confidence level (rpb = −0.1867, p-value = 0.0509). This means participants in the Steadiness group had less confidence in their answer when identifying phishing URLs when compared to participants within the other personality groups. There was a weak positive correlation between Conscientiousness and participants’ pre-training confidence level as well (rpb = 0.2033, p-value = 0.0332). This is the opposite of the participants in the Steadiness group, which implies participants in the Conscientious group have more confidence in identifying phishing URLs than participants in the other personality groups.

5.4. Gender and accuracy/confidence

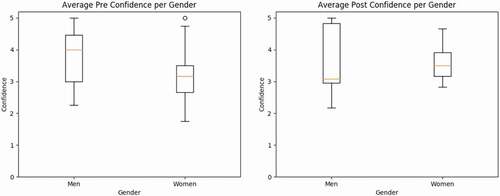

About one third of the participants from each of the pre- and post-training groups were males. shows the pre- and post-training survey information while shows the PB Correlation coefficients and p-values. Only the results for the pre-training confidence scores were significant, such that the PB Correlation analysis shows a weak positive correlation for the males (rpb = 0.1957, p-value = 0.0405) and a weak negative correlation for the females (rpb = −0.1957, p-value = 0.0405). This means that before completing the training, males were more likely to be confident in their answer choices than females. A box and whiskers plot pertaining to the pre- and post-confidence for each gender can be found in .

Table 7. Pre and Post Training Gender Average Accuracies and Confidence.

Table 8. Gender PB correlation coefficients and P-values.

5.5. Race/ethnicity and accuracy/confidence

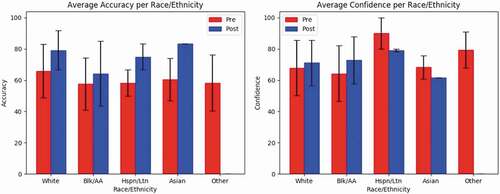

The next category with a significant correlation is the race/ethnicity category. There were a couple of subcategories that were not represented in the pre-training or post-training data (i.e., American Indian/Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander) and they were removed from the following race/ethnicity tables. For the other subcategories, the number of people – along with the average accuracy and confidence – can be seen in . As seen in , only Whites and Hispanics/Latinx experienced slight correlations; however, both subcategories have limited sample sizes, so no inferences can be made within these subcategories. The Whites had a weak positive correlation for pre-training accuracy (rpb = 0.1977, p-value = 0.0385). This means that compared to other races before training, White participants were able to detect phishing URLs at a higher rate. displays the accuracy and confidence information for the Race/Ethnicity category.

Table 9. Pre and post training race/ethnicity average accuracies and confidence.

Table 10. Race/Ethnicity PB correlation coefficients and P-values.

5.6. Years working and accuracy/confidence

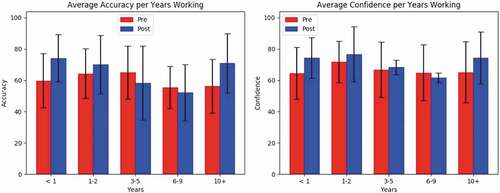

The years working at The University also resulted in significant accuracy and confidence correlations. The categorical information can be found in . This was also the first section using Biserial Correlation instead of PB Correlation as seen in . Here, participants who have been working at The University between 6–9 years had moderate negative correlations with both post-training accuracy (rb = −0.4976, p-value = 0.0155) and confidence (rb = −0.4559, p-value = 0.0285). shows the average accuracy and confidence for each subcategory group within the Years Working category.

Table 11. Pre and post training years working average accuracies and confidence.

Table 12. Years working biserial correlation coefficients and P-values.

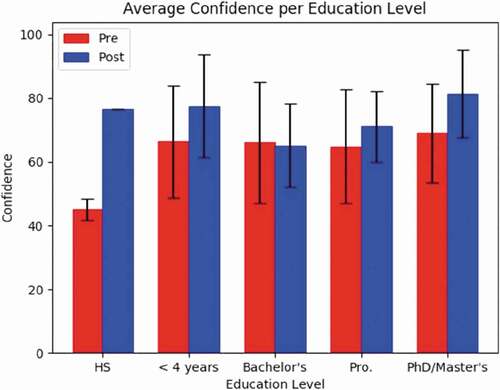

5.7. Education level and accuracy/confidence

show the categorical information and Biserial correlation information for the Education category, respectively. The Bachelor’s degree group had a moderate negative correlation with post-training confidence (rb = −0.4496, p-value = 0.0311) and the PhD/Master’s group had a moderate positive correlation with post-training confidence (rb = 0.4246, p-value = 0.0431). This means, after training, employees with only a Bachelor’s degree had less confidence in identifying phishing and legitimate URLs than other groups while employees with a PhD/Master’s degree had more confidence than other groups. depicts the average pre- and post-training confidence per Education level of the participants.

Table 13. Pre and post training education average accuracies and confidence.

Table 14. Education biserial correlation coefficients and P-values.

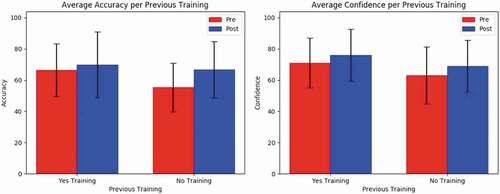

5.8. Previous training

The Previous Training category was formed by participants selecting whether or not they had participated in any previous security training. Participants who were unsure of previous training were grouped with participants without previous training. The categorical information is shown in while shows the PB correlation information. illustrates the accuracy and confidence information found in . There were significant correlations between previous training with pre-training accuracy and confidence level. There were weak positive correlations for participants with previous training for both pre-training accuracy (rpb = 0.317, p-value = 0.0007) and confidence (rb = 0.2185, p-value = 0.0218) while participants who were unsure of or had not had previous training had weak negative correlations with both pre-training accuracy (rpb = −0.317, p-value = 0.0007) and confidence (rb = −0.2185, p-value = 0.0218). This means that participants who experienced previous training were better and more confident in identifying phishing and legitimate URLs than participants who had not or were unsure of completing previous training.

Table 15. Pre and post training previous training average accuracy and confidence.

Table 16. Previous Training PB correlation coefficients and P-values.

5.9. Age and employment status

The Age and Employment Status categories had no apparent influence on susceptibility (see ).

Table 17. Pre and post training age and employment status accuracies and confidence.

Table 18. Age and employment status biserial correlation coefficients and P-values.

5.10. Discussion

summarizes the findings in terms of the three hypotheses. Based on the results of the analyses, the first and third hypotheses can only be partially accepted, while the second hypothesis can be fully accepted. The first hypothesis stated that, following the logic of the TTAT and, because of the KnowBe4 training, participants would experience an improvement in phishing knowledge, user behavior, and perceived risk. After running a t-test on the data collected, only participants’ self-perceived phishing knowledge and behavior improved as a confirmed result of the training. However, improvement in participants’ self-perceived risk cannot be confirmed.

Table 19. Hypotheses results and explanations.

The third hypothesis postulates that due to the various training methods, there will not be a difference between the subcategories within each demographic or the personality traits. This, again, is partially accepted and supported through the correlations between each subcategory and the accuracies and confidence levels. There were several subcategories that had a direct correlation with regard to producing higher accuracies and confidence levels and some that had a direct correlation with regard to producing lower accuracies and confidence levels. We can state that subcategories that produced significantly higher results are less susceptible to phishing attacks than their counterparts while subcategories with significantly lower results are more susceptible. Finally, based on the results, the second hypothesis, which states that because of the various training methods, the participants will be more adept at identifying phishing attempts, can be fully accepted based on the increase in accuracy and confidence level experienced after training. In addition to the t-test showing a significant increase in accuracy and confidence level, a direct correlation between post-training accuracy and confidence level was also discovered. This means that participants who were able to correctly identify phishing attacks were more confident in their answer choices.

Due to a lack of adequate participation in the post-training survey, inferences between many of the subcategories and their accuracy and confidence levels when detecting phishing URLs cannot be made. However, when looking into the Biserial and PB Correlation, there were some subcategories that were close to the 0.05 alpha level. There is a negative correlation between Blacks/African Americans with pre- and post-training accuracy. Meaning that Blacks/African Americans could be more susceptible than other races/ethnicities before and after the training. There is also a slight correlation between Hispanics/Latinx and pre-training confidence, indicating a higher chance in Hispanics/Latinx being confident in their answer choices more than other races/ethnicities. Meanwhile people working at The University 3–5 years had a positive correlation with pre-training accuracy, meaning that employees in this group were able to accurately identify phishing and legitimate URLs better than other groups. There were also other trends that could be significant with a larger sample size. After training, we can state that people with Bachelor’s degrees are less confident in identifying phishing URLs while people with PhDs/Master’s degrees are more confident in identifying phishing URLs. In addition, much like in Anwar’s 2016 paper, it appears that more security training is needed as a majority of the employees have not had or are unsure of having previous security training.Citation34 Also, interestingly, part-time employees are originally more susceptible to phishing attacks than full-time employees; however, this changed after both parties experienced the training. Similar to Anwar et al.’sCitation42 study showing that females reported lower self-efficacy scores than males, we noted that females reported lower confidence than males before and after training. Our findings on personality traits do not support the conclusion by Cho that people expressing agreeableness are more susceptible to phishing attacks.Citation35 Agreeableness in the Big Five personality traits is comparable to people expressing the Conscientiousness DISC personality trait, which according to our research, is one of the least susceptible personality traits before training.

The results of our research suggests that women are more susceptible than men; however, based on the number of false negative responses, women are less susceptible after training. The percentage of false negative responses for women was 18.3% before training which decreased to 15.9% after training. Other subcategories saw improvements in true and false negative responses as well. The Steadiness group’s percentage of false negatives decreased from 20.3% before training to 13% after training and the percentage of true negatives increased from 47.2% to 52.8%. Two subcategories in the Years Working group improved their true and false positive responses as well. The 3–5 years group improved their true negatives from 44.4% to 50% and their false negatives from 16.7% to 0%. The 6–9 years group improved their false negatives from 29.2% to 12.5% while their true negatives did not change. Participants who only completed some college decreased their false negatives from 29.1% before training to 8.3% after training and increased their true negatives from 41.7% to 50%. Both participants who did not have previous training and were unsure of previous training improved their true and false negatives after the KnowBe4 training.

6. Limitations

There are several limitations in this work. The most obvious limitation is the difference in research participants between the pre- and post-training sessions. This difference caused issues with collecting information from each subcategory in each demographic section. Therefore, we were not able to come to a full conclusion about certain subgroups’ susceptibility to phishing attacks. For example, conclusions on race were not drawn for the Hispanic, Asian, and Other groups due to the small number of participants for those groups. This limitation was mostly caused by the impact of the COVID-19 global pandemic. Also, we did not consider how long it took participants to complete a training module or how many attempts it took for them to pass the quizzes as this information was not provided to us by the University. Another limitation is only testing the participants immediately after training. Participants are hyperaware of phishing attacks immediately after training which is not a normal phishing scenario.

7. Conclusion and future work

This research was designed to investigate the effects of specific user demographics and personality traits on anti-phishing training programs and user susceptibility as they relate to the identification of phishing URLs. Based on the data collected, significant results were found. For example, by running two-sample t-tests, we were able to determine that the anti-phishing training had a positive improvement on participants’ phishing knowledge, their behavioral tendencies, and their ability to identify phishing attacks. These t-tests also determined that people with different levels of education may be impacted differently by the training. We were also able to illustrate that the training does not improve a participants’ perceived risk or reduce their susceptibility based on the DISC personality traits. This research is important so that organizations may be able to target highly susceptible individuals for increased training to prevent any breaches in security. Based on the results of this research, we believe that organizations may benefit from increasing training for employees who have been working between 6–9 years, have a Bachelor’s degree as their highest level of education, or are unsure of having or have not had previous training. In the future, we would like to address the limitations and biases of this work. By interviewing participants who completed the anti-phishing training, we could inquire more on their thoughts and understanding of phishing attacks before and after training. We would also like to continue examining phishing susceptibility by expanding the research to a wider participant pool. With an increased number of participants, we would like to analyze multiple categories at once to determine phishing susceptibility. For example, we could analyze age and gender or race/ethnicity and education level. Another plan for future implementation is to work closely with The University in order to create a long-term retention study where we can continue to test participants over an extended period of time to see how much information they retain from the training and to gather data from a non-hyper aware group.

References

- Heartfield R, Loukas G. A taxonomy of attacks and a survey of defence mechanisms for semantic social engineering attacks. ACM Comput Surveys (CSUR). 2016;48(3):37. doi:10.1145/2835375.

- Luo X, Brody R, Seazzu A, Burd S. Social engineering: the neglected human factor for information security management. Info Resour Manage J (IRMJ). 2011;24(3):1–8. doi:10.4018/irmj.2011070101.

- Orgill GL, Romney GW, Bailey MG, Orgill PM. The urgency for effective user privacy-education to counter social engineering attacks on secure computer systems. in Proceedings of the 5th conference on Information technology education. Salt Lake City, Utah, USA. 2004. ACM.

- Gragg D. A multi-level defense against social engineering. SANS Reading Room. 2003;13. p. 15 – 36

- Twitchell DP Social engineering in information assurance curricula. in Proceedings of the 3rd annual conference on Information security curriculum development. Kennesaw, Georgia, USA. 2006. ACM.

- KnowBe4. Phishing. Available from: https://www.knowbe4.com/phishing

- Jagatic TN, Johnson NA, Jakobsson M, Menczer F. Social phishing. Commun ACM. 2007;50(10):94–100. doi:10.1145/1290958.1290968.

- Garera S, Provos N, Chew M, Rubin AD. A framework for detection and measurement of phishing attacks. in Proceedings of the 2007 ACM workshop on Recurring malcode. Alexandria, Virginia, USA. 2007. ACM.

- Jakobsson M Modeling and preventing phishing attacks. in Financial Cryptography. Roseau, The Commonwealth of Dominica. 2005.

- Symantec, Internet Security Threat Report. 2018. p. 64–77.

- Hong J. The Current State of Phishing Attacks. In: Communications of the ACM. 2012;55(1): p. 74 – 81.

- Sumner A, Yuan X. Mitigating Phishing Attacks: an Overview. in Proceedings of the 2019 ACM Southeast Conference. Kennesaw, Georgia, USA. 2019.

- Zhang Y, Egelman S, Cranor L, Hong J. Phinding phish: evaluating anti-phishing tools. In: Proceedings of the NDSS Symposium. San Diego, California, USA. ISOC; 2006.

- Mouton F, Leenen L, Venter HS. Social engineering attack detection model: seadmv2. in Cyberworlds (CW), 2015 International Conference on. Visby, Sweden. 2015. IEEE.

- Sloan J. Phishing Mitigation for Small and Medium Businesses. 2020.

- Kowalski K, Billings DM, Kowalski K. Self-Assessment and the DiSC. J Conti Educ Nursing. 2019;50(8):347–48. doi:10.3928/00220124-20190717-04.

- Jones CS, Hartley NT. Comparing correlations between four-quadrant and five-factor personality assessments. Am J Business Educ. 2013;6:459–70.

- Liang H, Xue Y. Avoidance of information technology threats: a theoretical perspective. MIS quart. 2009;33(1):71–90. doi:10.2307/20650279.

- Carpenter D, Young DK, Barret P, McLeod A. Refining technology threat avoidance theory. Comm Assoc Info Sys. 2019;44:380 – 407.

- Annetta LA. Video games in education: why they should be used and how they are being used. Theory Pract. 2008;47(3):229–39. doi:10.1080/00405840802153940.

- Papastergiou M. Digital game-based learning in high school computer science education: impact on educational effectiveness and student motivation. Comput Educ. 2009;52(1):1–12. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2008.06.004.

- Alkhamis E, Renaud K. The Design and Evaluation of an Interactive Social Engineering Training Programme.In: Tenth International Symposium on Human Aspects of Information Security & Assurance. Frankfurt, Germany. 2016. p. 125 – 134.

- Sheng S, Magnien B, Kumaraguru P, Acquisti A, Cranor LF, Hong J, Nunge E. Anti-phishing phil: the design and evaluation of a game that teaches people not to fall for phish. in Proceedings of the 3rd symposium on Usable privacy and security. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA. 2007. ACM.

- Kumaraguru P, Rhee Y, Sheng S, Hasan S, Acquisti A, Cranor LF, Hong J. Getting users to pay attention to anti-phishing education: evaluation of retention and transfer. in Proceedings of the anti-phishing working groups 2nd annual eCrime researchers summit. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA. 2007. ACM.

- Kumaraguru P, Sheng S, Acquisti A, Cranor LF, Hong J. Teaching Johnny not to fall for phish. ACM Transac Internet Technol (TOIT). 2010;10(2):7. doi:10.1145/1754393.1754396.

- Bowen BM, Devarajan R, Stolfo S. Measuring the human factor of cyber security. in 2011 IEEE International Conference on Technologies for Homeland Security (HST). Waltham, Massachusetts, USA. 2011. IEEE.

- McBride M, Carter L, Warkentin M. Exploring the role of individual employee characteristics and personality on employee compliance with cybersecurity policies. RTI Int Instit Homeland Security Sol. 2012;5:1.

- Johnston AC, Warkentin M. Fear appeals and information security behaviors: an empirical study. MIS quart. 2010;34(3):549–66. doi:10.2307/25750691.

- Arachchilage NAG, Love S. A game design framework for avoiding phishing attacks. Comput Human Behav. 2013;29(3):706–14. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.12.018.

- Canham M, Posey C, Strickland D, Constantino M. Phishing for Long Tails: examining Organizational Repeat Clickers and Protective Stewards. SAGE Open. 2021;11(1):2158244021990656. doi:10.1177/2158244021990656.

- Sheng S, Holbrook M, Kumaraguru P, Cranor L, Downs J.Who falls for phish?: a demographic analysis of phishing susceptibility and effectiveness of interventions. in Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Atlanta, Georgia, USA. 2010. ACM.

- Alam S, El-Khatib K. Phishing susceptibility detection through social media analytics. in Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Security of Information and Networks. Newark, New Jersey, USA. 2016. ACM.

- Mohebzada JG, Zarka AE, Bhojani AH, Darwish A.Phishing in a university community: two large scale phishing experiments. in 2012 international conference on innovations in information technology (IIT). Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. 2012. IEEE.

- Anwar M, He W, Yuan X. Employment status and cybersecurity behaviors. in 2016 International Conference on Behavioral, Economic and Socio-cultural Computing (BESC). Durham, North Carolina, USA. 2016. IEEE.

- Cho J-H, Cam H, Oltramari A. Effect of personality traits on trust and risk to phishing vulnerability: modeling and analysis. in Cognitive Methods in Situation Awareness and Decision Support (CogSIMA), 2016 IEEE International Multi-Disciplinary Conference on. San Diego, California, USA. 2016. IEEE.

- Halevi T, Lewis J, Memon N, Phishing, personality traits and Facebook. arXiv preprint arXiv:1301.7643, 2013.

- Ferreira A, Lenzini G. An analysis of social engineering principles in effective phishing. in 2015 Workshop on Socio-Technical Aspects in Security and Trust. Verona, Italy. 2015. IEEE.

- Williams EJ, Hinds J, Joinson AN. Exploring susceptibility to phishing in the workplace. Int J Hum Comput Stud. 2018;120:1–13. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2018.06.004.

- Zielinska O, Welk A, Mayhorn CB, Murphy-Hill E.he persuasive phish: examining the social psychological principles hidden in phishing emails. in Proceedings of the Symposium and Bootcamp on the Science of Security. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA. 2016. ACM.

- Cialdini RB. Influence: the psychology of persuasion. New York: Williams Morrow. 2007. Vol. 55.

- Personality Traits Measured by the DISC Test. [ cited 2019; DISC Personality Questions]. Available from: http://prfwebsite.com/disc-pts/questions_trait_measured_V2.html.

- Anwar M, He W, Ash I, Yuan X, Li L, Xu L. Gender difference and employees‘ cybersecurity behaviors. Comput Human Behav. 2017;69:437–43. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.040.

Appendix A: Participant Survey Questions

Q) What is your gender?

Male

Female

Q) What is your ethnicity?

White

Black or African American

American Indian or Alaska Native

Hispanic or Latino

Asian

Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

Other (please specify) _______________________________

Q) Please select your age group.

18–25

26-36

37–59

60+

Q) Please select your status.

Full-time

Part-time

Student

Other (please specify) _______________________________

Q) How many years have you worked here?

less than 1 year

1–2 years

3–5 years

6–9 years

10+ years

Q) What is your highest level of education?

High school graduate

Some College/Associate’s Degree

Bachelor’s Degree

Professional Degree

Doctorate/Master’s Degree

Other (please specify) _______________________________

Q) What department do you work in?

_______________________________________________

Q) Have you ever completed an information security training session before?

Yes

Unsure

No

Q) If yes, did the training session discuss phishing attacks?

Yes

Unsure

No

Not applicable

End of Block: Demographics/Background

Start of Block: Computer Skills

Q) How comfortable are you with using a computer?

Extremely comfortable

Moderately comfortable

Slightly comfortable

Neither comfortable nor uncomfortable

Slightly uncomfortable

Moderately uncomfortable

Extremely uncomfortable

Q) How comfortable are you with using your e-mail?

Extremely comfortable

Moderately comfortable

Slightly comfortable

Neither comfortable nor uncomfortable

Slightly uncomfortable

Moderately uncomfortable

Extremely uncomfortable

Q12 How would you rate your general computer knowledge/skills?

Q13 How would you rate your internet knowledge/skills?

End of Block: Computer Skills

Start of Block: Personality Questions

Q) Choose one statement that is most like you …

Talkative

Daring

Loyal

Reserved

Q) How do other people see you?

People see me as calm

People see me as being helpful

People usually like my company

People tend to look up to me

Q) You have to work on a team, what role do you take?

I always try to be the team leader

I ensure a strong team dynamic and like everyone to be involved and feel included

I just wait and I certainly don’t seek leadership

I’d rather work alone

Q) Choose one statement that is most like you …

Disciplined

Entertaining

Dominant

Patient

Q) Choose one statement that is most like you …

Charming

Decisive

Private

Cooperative

Q) Choose one statement that is most like you …

Fearless

Sociable

Generous

Analytical

Q) Choose one statement that is most like you …

Systematic

Bold

Even Tempered

Influential

Q) Choose one statement that is most like you …

I am very active, both at work and play

I always take notice of what other people say

I am always cheerful

I like to behave correctly

Q) There’s a conflict on your team, how do you react?

Let’s not upset anyone

Let’s hear more details

Let’s get to the point

Let’s talk about it

Q) Choose one statement that is most like you …

I enjoy chatting with people

I’m a good listener

I like to handle things with diplomacy

I enjoy competition

Q) Choose one statement that is most like you …

I am always willing to do new things – to take a risk

I am always willing to follow orders

I am always ready to help

I am a very social sort of person

Q) Choose one statement that is most like you …

I am very patient

I don’t treat life too seriously

I enjoy competition

I am an agreeable person

Q) Choose one statement that is most like you …

I don’t like arguments

I am a sensitive person

I control my emotions

I am an assertive person

Q) Choose one statement that is most like you …

Shy

Adventurous

Calm

Chatty

End of Block: Personality Questions

Start of Block: Phishing Knowledge

Q) How well do you know about general phishing attacks?

Extremely well

Very well

Moderately well

Slightly well

Not well at all

Q) When browsing the internet, I can identify a phishing website …

Strongly agree

Agree

Somewhat agree

Neither agree nor disagree

Somewhat disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

Q) When using my e-mail, I can identify a phishing e-mail …

Strongly agree

Agree

Somewhat agree

Neither agree nor disagree

Somewhat disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

Q) I know how to prevent a phishing attack …

Strongly agree

Agree

Somewhat agree

Neither agree nor disagree

Somewhat disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

Q) Have you ever received a phishing e-mail?

Yes

Unsure

No

Q) Have you ever fallen victim to a phishing attack?

Yes

Unsure

No

Q) Explain what phishing is to the best of your understanding …

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

End of Block: Phishing Knowledge

Start of Block: Behavioral

Q) How often do you open e-mails from unknown senders?

Always

Most of the time

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

Q) I carefully examine whether an e-mail I received has suspicious links or attachments, even when it comes from someone I know.

Always

Most of the time

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

Q) How often do you check to make sure a website is legitimate?

Always

Most of the time

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

When you receive a suspicious e-mail, how often do you …

Q) inform the rest of your department?

Always

Most of the time

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

Q) inform the IT department?

Always

Most of the time

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

End of Block: Behavioral

Start of Block: Perceived Risk

Q) Phishing is a risk in your department …

Strongly agree

Agree

Somewhat agree

Neither agree nor disagree

Somewhat disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

Q) Phishing attacks are a threat to the university …

Strongly agree

Agree

Somewhat agree

Neither agree nor disagree

Somewhat disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

Q) My e-mail’s security will stop phishing attacks from getting through …

Strongly agree

Agree

Somewhat agree

Neither agree nor disagree

Somewhat disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

Q) My chances of receiving a phishing e-mail are low …

Strongly agree

Agree

Somewhat agree

Neither agree nor disagree

Somewhat disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

Q) If a phishing attack were successful on my workstation/computer it would not affect my department or the university.

Strongly agree

Agree

Somewhat agree

Neither agree nor disagree

Somewhat disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

End of Block: Perceived Risk

Start of Block: Phishing Test

For the following section, please choose whether the website listed is a phishing website or a legitimate website and then mark your confidence level.

Q) https://web-ao.da-us.citibank.com/cgi-bin/

Phishing Website

Legitimate Website

Q) How confident do you feel in your answer?

Extremely confident

Very confident

Moderately confident

Slightly confident

Not confident at all

Q) http://account-verification.com/ebay/verify/

Phishing Website

Legitimate Website

Q) How confident do you feel in your answer?

Extremely confident

Very confident

Moderately confident

Slightly confident

Not confident at all

Q) https://www3.nationalgeographic.com/

Phishing Website

Legitimate Website

Q) How confident do you feel in your answer?

Extremely confident

Very confident

Moderately confident

Slightly confident

Not confident at all

Q) http://secure-signin.ebay.com.ttps.us/

Phishing Website

Legitimate Website

Q) How confident do you feel in your answer?

Extremely confident

Very confident

Moderately confident

Slightly confident

Not confident at all

Q) http://citibusinessonline.da-us.citibank-updates.com/

Phishing Website

Legitimate Website

Q) How confident do you feel in your answer?

Extremely confident

Very confident

Moderately confident

Slightly confident

Not confident at all

Q) www.amazon.com/help/confirmation

Phishing Website

Legitimate Website

Q) How confident do you feel in your answer?

Extremely confident

Very confident

Moderately confident

Slightly confident

Not confident at all

Q) http://www.paypal.com.ssl2.us/webscr.php?cmd=LogIn#

Phishing Website

Legitimate Website

Q) How confident do you feel in your answer?

Extremely confident

Very confident

Moderately confident

Slightly confident

Not confident at all

Phishing Website

Legitimate Website

Q) How confident do you feel in your answer?

Extremely confident

Very confident

Moderately confident

Slightly confident

Not confident at all

Q) http://pages.ebay.com/services/forum/feedback.html

Phishing Website

Legitimate Website

Q) How confident do you feel in your answer?

Extremely confident

Very confident

Moderately confident

Slightly confident

Not confident at all

Phishing Website

Legitimate Website

Q) How confident do you feel in your answer?

Extremely confident

Very confident

Moderately confident

Slightly confident

Not confident at all

Q) http://www.ebay-accept.com/login.php

Phishing Website

Legitimate Website

Q) How confident do you feel in your answer?

Extremely confident

Very confident

Moderately confident

Slightly confident

Not confident at all

Q) https://www.paypal.com/ssl2/us/webscr?cmd=_login-run

Phishing Website

Legitimate Website

Q) How confident do you feel in your answer?

Extremely confident

Very confident

Moderately confident

Slightly confident

Not confident at all

End of Block: Phishing Test

Start of Block: Personality Scenarios

Q) You receive an e-mail from your bank saying that someone may have access to your account. The e-mail contains a link so that you can sign into your online account, change your password, and view recent purchases to confirm if someone has hacked your account.

Is this an example of phishing?

No

Yes, please explain … ________________________________

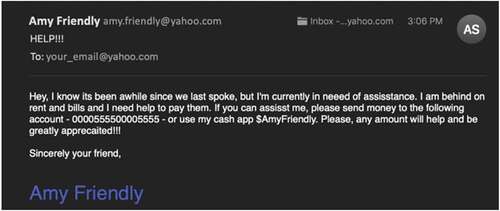

Q) You receive the following e-mail.

Do you think this could be an example of phishing?

No

Yes, please explain … ________________________________

Q) You receive the following e-mail.

Do you think this could be an example of phishing?

No

Yes, please explain … _________________________

Q) You receive an e-mail from your boss, who is out of town. The e-mail asks for you to scan and send them a file that contains sensitive information that they forgot on their desk. You respond saying that you can’t send a file with such information. Your boss responds with the following. Please select which response would most likely make you send the file.

… ”You need to send the file. If you do not then I will write you up when I return.”

… ”I know you shouldn’t send sensitive information, but that file is VERY important for a conference call that I have 10 minutes.”

… ”It’s alright. I will ask someone else to send me the file.”

… ”I know you shouldn’t send sensitive information, that is why I need someone I can trust to make sure that the file is sent and you are the only one in the office that I can trust. “

Q) (optional) In regards to the previous question, is there anything you would have done before sending the file? (i.e. asked around the office, confirmed you were talking to your boss, etc.)

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________

______________________________________________