ABSTRACT

Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) constitute a very large part of every country’s economy and play an essential role in economic growth and social development. SMEs are frequent targets of cyberattacks. Unlike large enterprises, SMEs generally have limited capabilities regarding cybersecurity practices. Assessment and improvement of cybersecurity capabilities are crucial for SMEs to survive and sustain their operations. Despite the availability of maturity assessment models and standards to assess and improve cybersecurity capabilities, SMEs’ specific requirements and roles in the digital ecosystem are often neglected. This paper presents high-level SME requirements regarding cybersecurity maturity assessment and standardization and translates them into an Adaptable Security Maturity Assessment and Standardization (ASMAS) framework to address this gap. The framework is demonstrated by a web-based software prototype. In the evaluation study conducted with SMEs, we obtained positive results for perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use of the framework, and intention to use it.

1. Introduction

Information security and cybersecurity deal with ensuring confidentiality (C), integrity (I), and availability (A) of information. Other information properties, such as authenticity and reliability, can also be involved. According to the ISO/IEC 27032 standard, cybersecurity is preserving those properties in cyberspace. In contrast, information security is not limited to cyberspace and is preserving the CIA in general.Citation1 Having made this distinction, our focus in this paper is all-encompassing. Thus, we investigate cybersecurity and information security in conjunction and refer to them as security.

According to the World Bank, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) represent 90% of businesses and more than 50% of employment worldwide.Citation2 As SMEs are the backbone of every country or region’s economy and digitalization is no longer optional, their resilience to malicious attacks and dependability are increasingly important. SMEs often share a business ecosystem by providing services to large enterprises. An OECD report on the digital transformation of SMEs states that during the ongoing pandemic, SMEs are increasingly using online platforms.Citation3 The prior security challenges for SMEs remain but are amplified with the surge of teleworking and the need for operating remotely.Citation3,Citation4 Malicious actors exploit these difficult times for their objectives, and governments issue alerts for individuals and organizations to warn them and increase awareness.Citation5 Having weak security practices has a twofold effect on SMEs. On the one hand, it can create a barrier for them to engage with large businesses. On the other hand, it can make them targets for attacks as a gateway to penetrate their alliances. SMEs can build trust in their existing or target business ecosystem by establishing good security practices. By doing so, they will have the advantage of pursuing new engagement opportunities.Citation3 “Digital technology and security” is identified as one of the dimensions of digitally enabled growth in SMEs.Citation6

The European Digital SME Alliance represents about twenty thousand digital SMEs in Europe. Their position paper on Covid-19 economic recovery proposes the key areas in which quick actions are needed for recovery, one of which is cybersecurity & standards. They emphasize the heterogeneity of SMEs, thus the need for tailored and practical solutions and ensuring SMEs’ access to and awareness of standards.Citation7 Both security maturity assessments and security standardization help organizations improve their security capabilities and processes.Citation8,Citation9 We refer to standardization as adopting existing standards (international, regional, or national). Despite the challenges faced by SMEs, research on cybersecurity considering SMEs has been scant in the literature.Citation10

Originating from the software engineering domain, organizations have used maturity models to assess and improve their capabilities for a couple of decades.Citation11 Maturity modeling has attracted researchers’ attention in various domains.Citation12 Information security and cybersecurity domains were no exception.Citation13–15

Cybersecurity or information security needs, goals, and requirements depend on the organizational context.Citation16 Therefore, the adaptivity of security solutions, including maturity models and standards, to varying organizational contexts is essential. In security maturity assessment literature, researchers have investigated the organizational context and adaptivity of the assessment models from various angles. An information security maturity assessment and process improvement tool has been proposed for SMEs.Citation17 This tool is in the form of a standards-based questionnaire conducted by the researchers. However, there is no information in the published work about how the questionnaire is adapted to different organizational contexts.Citation17 Mijnhardt et al.Citation18 approach organizational characteristics in two ways. First, as some indicators such as the number of employees and revenue. Second, as the nature of business processes such as outsourcing of or complexity in information technologies. Yigit Ozkan and SpruitCitation19 have investigated the design requirements for an information security maturity model adaptable to SMEs by focusing on internal characteristics of SMEs, such as lack of organizational capabilities, short-term vision, and orientation.

In cybersecurity standardization literature, gaps and needs for SMEs have been identified in a research agenda that points out the adaptivity issues within several research questions.Citation10 Barlette and FominCitation20 state the need for future research on the creation and adoption of simplified security methods or standards dedicated to SMEs. Manso et al.Citation21 recommend that “standards applicable by SMEs should incorporate maturity levels with different sets of requirements to facilitate a phased implementation” to facilitate the implementation of security standards by SMEs. Inspired by these research gaps in the literature regarding adaptivity issues in security maturity assessment and standardization, and adoption challenges of SMEs, we state our research objective as “To integrate security maturity assessment and standardization in an adaptive instrument to support concurrent implementation efforts of digital SMEs.”

To address this research objective, we employ a Design Science Research approach. We investigate the needs, goals, and requirements of SMEs and propose a design artifact as a solution. Our design artifact is the Adaptable Security Maturity Assessment and Standardization (ASMAS) framework for digital SMEs. The framework builds on a set of high-level SME requirements, is adaptable to the different roles SMEs take in digital ecosystems, and embeds security risk management and standardization concepts. The artifact is developed to support SMEs in establishing, improving and demonstrating security maturity and standardization concurrently. The framework may also guide researchers and practitioners in the development of security maturity assessment models for SMEs.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides the relevant background information. In Section 3, we explain our research approach and methodology. Section 4 introduces the high-level SME requirements regarding security maturity assessment. Section 5 presents the ASMAS framework and its aspects that address the high-level requirements. In Section 6, we describe the software prototype. Section 7 presents the evaluation of the framework and the evaluation results. In Section 8, we discuss the results and the limitations. Finally, conclusions are drawn, and potential areas for future research are proposed.

2. Background

2.1. SME characteristics and categories

Several researchers investigated how SME characteristics are different from larger companies.Citation22–24 The implications of SME characteristics on information security have been investigated at single SME and cluster levels.Citation18,Citation25,Citation26 Furthermore, the effect of SME characteristics on the design of information security maturity models has been investigated, and the design requirements to be considered have been reported.Citation19 The question of what approach to take for categorizing SMEs according to their security requirements has been a pertinent one. The European Digital SME Alliance has proposed SME categories with respect to SMEs’ role in the digital ecosystem in their position paper on the European Union Cybersecurity Act and the role of standards for SMEs.Citation27 presents these categories.

Table 1. SME categories according to their roles in the digital ecosystem.Citation27.

The European Digital SME Alliance focuses on two challenges of SMEs: cybersecurity and standardization that are to be addressed by distinguishing the SME categories.Citation27 The categorization in takes into account the different security requirements of digital SMEs that originate from their various roles in the digital ecosystem. As our research aim is to support digital SMEs in their security and standardization efforts, in this research, we opted to use these categories presented in . SMEs’ security and standardization requirements depend on and are shaped by their roles in the digital ecosystem. The Start-ups category in this categorization does not refer to the stage of the operation of a company, as described in , these SMEs are the ones that neglect or are not well aware of cybersecurity.

2.2. Security standardization and SMEs

Despite SMEs’ challenges in security standardization,Citation27 there are no information security or cybersecurity standards available specifically for SMEs.Citation10 Barlette and FominCitation20 state that few information security standards are theoretically suitable for SMEs, but given the cost, the skills needed, and the language issues, it can be assumed that there is no method that can help SMEs to improve their security. This hasn’t changed in time; however, there are guidelines, technical reports, and frameworks that can help SMEs in security standardization.Citation28–30 Security standardization produces opportunities but also presents challenges for SMEs. The Digital SME alliance in corporation with Small Business Standards has published an SME GuideCitation31 for the implementation of ISO/IEC 27001 for establishing an information security management system. There are initiatives of public and private sector actors in different countries to help SMEs with cybersecurity. These initiatives are in the form of guidelines, frameworks and certification schemes. Some examples are as follows: Cyber Essentials from the UK,Citation32 The Center for Cyber Security Belgium SME Guide from Belgium,Citation33 Center for Internet Security Controls from USA,Citation34 and ETSI (global),Citation35 NIST Small Business Information Security from USA,Citation36 and Finnish Cyber Security Certificate from Finland.Citation37

2.3. Security maturity assessment

Maturity models in different domains have been developed and used since they became popular after the introduction of the Capability Maturity Model of the Software Engineering Institute of Carnegie Mellon University.Citation11 There is abundant research related to security maturity modeling.Citation8,Citation14,Citation38

The SME characteristics that influence their security maturity proposed by Mijnhardt et al.Citation18 are indicators (e.g., number of employees, revenue) to distinguish between a wide variety of different organizations. Following a similar categorization, Sánchez et al.Citation39 proposed a maturity model for information security management within SMEs. In another study, researchers investigated how to address internal SME characteristics for designing information security maturity models.Citation19 Benz and ChatterjeeCitation40 proposed a cybersecurity assessment tool specifically for SMEs. The tool is based on the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST) Cybersecurity Framework (CSF),Citation41, and it uses a subset of activities of the NIST CSF that are chosen as applicable to or feasible for SMEs. Although the proposed tool provides SMEs with a tool for assessing their cybersecurity capabilities concerning (a subset of) a reference model, it does not take the SMEs’ different roles in the digital ecosystem and their different needs that emerge out of their roles.Citation40 NIST CSF itself includes tiers that “describe an increasing degree of rigor and sophistication in cybersecurity risk management practices” which may guide SMEs to start with informal and reactive approaches and progress toward more risk-informed approaches.Citation41

Although research has been carried out on security maturity models targeting SMEs, or the adaptability of existing models to SMEs, no studies have considered the different roles SMEs take in the digital ecosystem.

3. Research methodology

We followed the Design Science Research (DSR) methodology consisting of the following steps: identify problem and motivate, define objectives of a solution, design and development, demonstration, evaluation and communication.Citation42 Accordingly, our research includes realizing a problem situation, identifying high-level SME requirements (objectives of a solution), developing the framework, demonstrating and evaluating the use of the framework with a prototype, and communicating the research results. Our research process is presented in .

Figure 1. The research process.Citation42

As discussed in the introduction and background sections, we reviewed the literature to identify the problem and motivate our research. The problem identification and motivation step provided the input for setting the high-level requirements for security maturity modeling and standardization for SMEs. These requirements serve as objectives for the design and development step to be addressed by the framework (i.e., design artifact) aspects and components. The framework was developed by assembling the aspects and components to address the requirements.

To evaluate our framework, we adapted the “Prototyping” evaluation pattern for DSR artifacts, and hence we provide an implementation of the solution through a prototype.Citation43 We created a knowledge base in the prototype to demonstrate the aspects included in the framework. Pries-Heje et al.Citation44 investigate the strategies for DSR evaluation and propose a framework that encompasses both ex-ante and ex-post orientations in naturalistic or artificial settings for DSR evaluation. We adapted evaluation constructs from the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)Citation45 to evaluate our framework with SMEs for predicting how likely our design artifact is to be adopted in practice.Citation46 Our evaluation study was conducted with practitioners from real SMEs after the artifact was constructed; therefore, our evaluation is ex-post. We evaluated the ASMAS framework by conducting interviews with SMEs, which is accompanied by an evaluation form.

4. High-level requirements

In the DSR, understanding the problem space is crucial to propose useful artifacts to real-world problems.Citation46 There are four key concepts to understand and define the problem space: needs, goals, requirements, and stakeholders.Citation47 The stakeholders in our research are SMEs. On the one hand, being non-homogeneous, SMEs have different needs regarding cybersecurity and standardization that depend on their organizational context (i.e., their role in the digital ecosystem). On the other hand, SMEs’ goal (intended outcome) is to secure their organization against cyber threats. We derived a set of high-level requirements (HLRs) regarding security maturity modeling and security standardization for SMEs to address this goal.

4.1. HLR1- Easy to use, self-assessment, do-it-yourself

Assessment and improvement planning should be easily realized by SMEs, requiring minimal extra resources.

Rationale: SMEs lack the resources (time, money, and expertise) to establish security capabilities and security standardization.Citation22,Citation48 The existing security maturity models and standards are costly and complex. Lack of financial resources is a barrier for SMEs to get external support to help with cybersecurity.Citation49 Self-assessment is a means by which an organization assesses compliance to a selected reference model or module without requiring a formal method.Citation50 Ritchie and DaleCitation51 summarize the benefits of self-assessment from a quality management perspective. Most of the benefits are also applicable from a security management perspective. The following are critical for SMEs with a security perspective: self-assessment helps keep costs down, raises understanding and awareness of security, and develops a holistic approach to security. The Cyberwatching.eu project surveyed cybersecurity standardization gaps. Their white paper summarizes the findings and recommendations and states the need to explore self-assessment and other low-cost solutions.Citation52

4.2. HLR2 – Situational awareness

The assessment model should provide customized guidance and implementation plan according to SME categories.

Rationale: Digitalization brings security as a critical element in business model scaling, and it is both a necessity and an enabler for SMEs.Citation53 Depending on the digitalization level, SMEs’ needs for cybersecurity dramatically differ. None of the available security models addresses this situational aspect. In design science research, artifact mutability ‒ the adaptability of DSR artifacts ‒ is proposed as one of the components of design theories.Citation54 The design of adaptable artifacts is referred to as situational artifact construction (SAC). SAC allows the researcher to develop artifacts which are adaptable to different design problems within a problem class, and to understand the relevant design situations within this class.Citation55 As the costs for adapting a more generic solution artifact to a specific design problem are higher than those for adapting the more specific solution artifact, developing situational artifacts reduces the cost of adaptation.Citation55 Understanding the organization’s context is the primary step when establishing information security or cybersecurity.Citation16 SMEs are not homogenous, and they differ in their requirements for security. The difference between SMEs can be characterized by their role in the digital ecosystem.Citation27,Citation53

4.3. HLR3 – Support for standardization and standards-transparency

The framework should support the ability to adhere to related standards on security. The relation between security capabilities and standards should be transparent. The framework should provide a progressive path for adopting standards and frameworks to help SMEs follow a step-by-step approach.

Rationale: In standard development, SMEs are often neglected and require financial support, access to technical expertise, and assistance to be active stakeholders.Citation56 Maturity models have the basic design principle of “Definition of central constructs related to the application domain.”Citation57 If the application domain has achieved a level of maturity to have published standards by standards developing organizations, these standards can be used as sources for defining domain-specific constructs of the maturity model.Citation58 A maturity assessment model having constructs based on standards in the application domain can help organizations in both their maturity improvement and standardization efforts simultaneously by integrating maturity assessment and standardization in the same tool (design artifact). Organizations using the maturity assessment model to improve their cybersecurity would be able to adhere to (or adopt) the standards in the application domain. While establishing security capabilities, SMEs can improve their adherence to security standards. This can be accomplished by using standards as the primary source for maturity model capabilities. Consequently, we derive the following HLR:

4.4. HLR4 – Provide security awareness

The model should help increase security awareness concerning the assessed capabilities by considering SME categories.

Rationale: SMEs’ awareness of security and related standards is low. This partly stems from the lack of resources and the security domain’s perceived complexity.Citation59 SMEs’ level of security awareness might differ according to their role in the digital ecosystem. By considering human actors as part of the solution rather than the problem regarding security,Citation60 awareness of the organizations’ employees and managers has critical importance.

4.5. HLR5 – Maintainability and adaptability by design

New standards, threats, risks, and capabilities should easily be included in the assessment model.

Rationale: Given the ever-changing and dynamic nature of security threats and risks, it is crucial to incorporate emerging security capabilities and standards. This will ensure the maintainability of the assessment model and support it to be future-proof. In design science research, this phenomenon is referred to as “mutability-in-use,” a strategy that takes into account the future needs that may emerge when the artifact is in use.Citation61

In the following section, we propose an adaptable security maturity assessment and standardization framework to address the HLRs.

5. The Adaptable Security Maturity Assessment and Standardization (ASMAS) framework

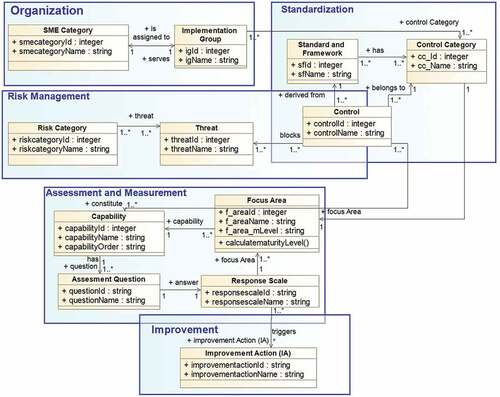

The ASMAS framework integrates five aspects: organization, standardization, risk management, assessment and measurement, and improvement. illustrates the meta-model of the ASMAS framework.

Figure 2. The meta-model of the Adaptable Security Maturity Assessment and Standardization (ASMAS) Framework.

In the following subsections, we elaborate on why the aspects are needed to address the high-level requirements presented in Section 4 and how the aspects work together. The framework addresses the SME categories shown in . The Organization aspect presented in Section 5.1 elaborates on how this is accomplished. A mapping of the high-level requirements and the aspects that address them is presented in Section 5.6.

5.1. Organization aspect

The Organization aspect is included in the framework to mainly make it situation-aware and enable self-assessment by organizations. The Organization aspect comprises the SME categories and Implementation Groups (IGs). IGs are composed of Control Categories. Each control category (1 to n) has several controls populated from standards and frameworks. IGs are constructed according to SME categories and provide SMEs in each category with a tailored perspective on the controls and capabilities relevant to their organizational profile. The Organization aspect enables SMEs to explore and use the framework according to their IG. illustrates the Control Categories, IGs, and the associations between the SME categories and the IGs.

Figure 3. Control categories, implementation groups, and their associations with the SME categories.

The Organization aspect addresses the “self-assessment” HLR(#1) and the “situational awareness” HLR(#2) by using a designated implementation group per SME category. The Organization aspect introduces configuration parameters for artifact mutability.Citation62

5.2. Standardization aspect

The standardization aspect is included in the framework to provide organizations with support in their standard adherence and awareness processes. The Standardization aspect comprises standards and frameworks. Standards and frameworks are the sources of security controls in the Risk Management aspect. Controls are the sources for capabilities and assessment questions in the Assessment and Measurement aspect. The Standardization aspect addresses HLR(#3) (support for standardization and standards-transparency), and HLR(#5) (maintainability and adaptability by design) by facilitating the inclusion of new standards and frameworks (mutability-in-use).

Overlapping controls in the standards and frameworks should be taken into account to eliminate duplicate end-user efforts. This is accomplished by deriving the capabilities (see Section 5.4) by considering all the controls from relevant standards and frameworks for each control category.

The Standardization aspect introduces best practices from standards and enables the integration of maturity assessment and standardization in one framework.

5.3. Risk management aspect

The Risk Management (RM) aspect is included in the framework to provide organizations with cybersecurity awareness based on threats, risks, and associated controls from the standards and frameworks. The RM) aspect introduces the core concepts of security risk management and comprises threats, risks, and controls. Ontologies and taxonomies can be used as sources of threats and risks. Control categories and controls are to be derived from standards and frameworks. Control categories are considered as a group of controls that have common objectives. The RM aspect enables SMEs to explore and use the framework according to their threats and risks. The RM aspect addresses “the situational awareness” HLR (#2) (by the association of implementation groups and controls). As the RM aspect incorporates risks and threats, it addresses the “provide security awareness” HLR (#4). The RM aspect also addresses “the maintainability and adaptability by design” HLR (#5) by enabling the inclusion of emerging threats, risks, and controls (mutability-in-use).

For specific SMEs, we presume that a security risk analysis will yield more appropriate controls than those assigned per SME category through implementation groups. The concern is to provide SMEs with a quick start to security that can be improved upon. The RM aspect in the framework is for supporting SMEs to have a risk-based view on the controls.

5.4. Assessment and measurement aspect

The Assessment and Measurement (A&M) aspect is included in the framework to provide organizations with a means for self-assessing their security capabilities. One of the purposes of using a security maturity model is the assessment of existing capabilities and measuring performance.Citation8,Citation57,Citation63,Citation64 This purpose of use is referred to as “descriptive purpose of use.”Citation57 The A&M aspect comprises the following: capabilities, assessment questions, measurement mechanism, focus areas, response scale, and maturity levels. To assess the current maturity level of a functional domain, measures must be defined for each of the capabilities. This can be done by formulating assessment questions for each capability. Formulation of the questions is usually based on the descriptions of the capabilities, experience, and practices.Citation65

A measurement mechanism is required for measuring the current level of an organization’s capabilities. Although a two-level scale (Implemented‒Not-implemented) might be used, a four-level scale will give higher precision.Citation66 Focus areas are the areas that have to be developed to achieve maturity in a functional domain.Citation65 In our framework, control categories in the Standardization aspect correspond to focus areas in the A&M aspect. Given the answers to the assessment questions, a maturity level per control category (i.e. focus area) can be calculated according to the desired measurement mechanism. The function calculatematurityLevel() function in is to be developed to achieve this purpose. Together with the Organization aspect, the A&M aspect addresses the self-assessment HLR(#1) and situational awareness HLR(#2). SMEs will face the applicable assessment questions associated with their organizational profile (mutability-in-design). Measurement of the maturity is based on the answers provided to the assessment questions.

5.5. Improvement aspect

The improvement aspect is included in the framework to provide organizations help with approaching security and standardization progressively. The Improvement aspect is tied to the capability assessment questions and triggered by the assessment results. Another purpose of using maturity models is to improve capabilities to the desired level on the scale. This purpose of use is referred to as “prescriptive purpose of use.”Citation57 The Improvement aspect comprises improvement actions. When the SME performs a self-assessment using the assessment questionnaire, based on the given answers, the capabilities that are not currently fully implemented can be used to formulate a customized improvement plan that also facilitates standardization efforts.

The standards transparency HLR(#3) is addressed by the Improvement aspect, which ensures that SMEs have a quick reference for the capabilities (that are derived from standards and frameworks), increase their standards awareness and adherence to standards. Together with the Organization and Risk Management aspect, the Improvement aspect addresses the situational awareness HLR(#2). Personalized improvement plans can be prepared by selecting controls that are designated according to the SME categories. Both the Organization aspect (by implementation groups) and the Risk Management aspect (by the association of implementation groups and controls) play a role in accomplishing this. As part of the Improvement aspect, providing security awareness addresses another HLR(#4).

5.6. Mapping of high-level requirements and aspects

shows the mapping of the high-level requirements and the aspects that address the corresponding requirement. The rationale for these mappings is discussed in Section 5.1–5.5.

Table 2. Mapping of the high-level requirements (HLRs) and the framework aspects.(O: Organizational, S: Standardization, RM: Risk Management, A&M: Assessment and Measurement, I: Improvement).

The ASMAS framework addresses all high-level requirements by integrating the aspects that are described above and visually presented in the meta-model (). Given the challenges faced by SMEs, the ASMAS framework proposes a “one-stop-shop” for SMEs to start with security and standardization.

6. The software prototype and the knowledge base

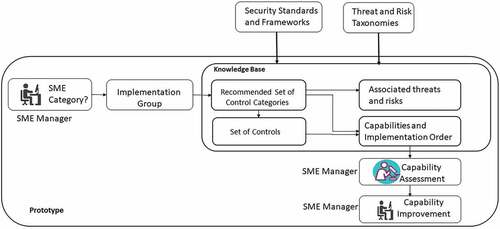

A prototype is implemented to demonstrate the ASMAS framework as a web-based application using a low-code software development tool ‒ Mendix Studio Pro 9.0.2 platform ‒ (free version).Citation67 The screenshots of the prototype are presented in Appendix 1 and illustrations based on scenarios are presented in Appendix 2. presents the conceptual model of the prototype.

As shown in , the prototype includes a knowledge base of the framework components (e.g., control categories, controls, standards, risks, threats). The knowledge base was populated from five standards and frameworks (control sources).Citation28 These standards and frameworks are as follows: Cyber Essentials from the UK,Citation32 The Center for Cyber Security Belgium SME Guide from Belgium,Citation33 Center for Internet Security Controls from USA,Citation34 and ETSI (global),Citation35 NIST Small Business Information Security from USA,Citation36 and ISO/IEC 27002:2013.Citation68 We analyzed these standards and frameworks and put forward a union set of control categories (see Section 5.3). We used the SME categories presented in to identify the SME profiles (Implementation Groups) in the prototype. We populated the knowledge base with the threat taxonomy of ENISA (European Union Agency for Cybersecurity),Citation69 and with the taxonomy of operational cybersecurity risks from the Carnegie Mellon University, USA.Citation70

The knowledge base’s content implemented in the prototype is summarized in . Appendix 3 presents the illustration of the controls and capabilities for a control category.

Table 3. The summary of control-related content of the knowledge base.

Table 4. The summary of capability, risk, and threat-related content of the knowledge base.

In the prototype, the process starts with the SME manager identifying their organization’s category according to . Subsequently, the prototype assigns an implementation group for the SME, and the SME manager can view the recommended set of controls for their category. The prototype incorporates considerably simple frameworks such as Cyber Essentials, as well as a comprehensive standard such as ISO/IEC 27002. The inclusion of such diverse sources of controls and unified control categories enables digital SMEs to be able to see and compare the controls that standards and frameworks offer. A digital SME, having implemented Cyber Essentials, can see what additional controls are included in ISO/IEC 27002. SMEs can also focus on one control category that they consider would be useful in their business context and plan for acquiring the capabilities associated with that control category. As the prototype has been designed in a way that the appropriate set of control categories are assigned to SME profiles, the cost of adopting the capabilities can be reduced.

presents the functions implemented in the software prototype.

Table 5. The functions in the ASMAS framework prototype.

7. Evaluation of the framework

In this section, we present the evaluation of the ASMAS framework by instantiating and demonstrating the framework using the software prototype and the evaluation results. We followed purposive sampling to find the participants for our evaluation study that fit our research context. We aimed to find SMEs that are related to cybersecurity maturity. To acquire SMEs for our evaluation study, we reached out to the SME participants in the EU Horizon2020 SMESEC projectCitation71 and the EU Horizon2020 GEIGER project.Citation72 The focus of these two projects is cybersecurity for SMEs. We conducted evaluation sessions with SMEs that responded positively to our request.

We have conducted seven evaluation sessions with six SMEs. Each session consisted of an approximately one-hour online interview. There were two experts from one SME who were willing to participate in the evaluation study. In each session, one of the researchers presented the conceptual framework and then demonstrated the framework using the software prototype. This was followed by a discussion. At the end of each interview session, we sent out evaluation forms to the participants to obtain their feedback on the utility of the proposed framework.

To understand and predict the acceptance of our design artifact, we have focused on the constructs perceived usefulness, ease of use, and intention to use in line with the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) core constructs.Citation45,Citation46 Perceived usefulness refers to the user’s perception concerning how the design artifact enables the user to enhance their performance in a given context. Perceived ease of use entails the user’s perception concerning the degree to which use of the artifact would not require physical or mental effort. Intention to use explains user acceptance of the design artifact.Citation45 The perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness affect the intention to use the design artifact. External variables (e.g., training, background experience, risks, and opportunities) also affect the intention to use. Intention to use can be used to explain what utility is created by means of the use of the artifact. We used these three constructs to guide the further design of our evaluation interviews and questionnaires. presents the set of questions in the evaluation form to evaluate each construct. We used three statements per evaluation construct to evaluate the framework resulting in nine statements.

Table 6. Set of questions used to evaluate the utility of the ASMAS framework.

In the evaluation form, we used a 5-point Likert scale to understand the level of agreement of the interviewee concerning each statement, for which 1 represents ‘strongly disagree’ and 5 represents ‘strongly agree.’ We also gathered the characteristics of the SMEs and the interviewees via the evaluation form. These characteristics are presented in .

Table 7. Evaluation study participants’ characteristics

7.1. Evaluation results

The results of the evaluation are presented in . We elaborate on the findings per evaluation criteria and present quotes from the participants in the following paragraphs.Citation32

Table 8. Responses to the evaluation form statements.

We also included optional open-ended questions in our evaluation form to gather more insights on the perception of the framework. Not every SME preferred to answer those questions. We also present and discuss the answers we gathered for the open-ended questions in the following paragraphs.

7.1.1. Perceived usefulness

Regarding the perceived usefulness, the majority of the participants considered the ASMAS framework as useful, given the high responses associated with the corresponding statements (statements 1, 2, and 3).

The answers to the open-ended questions support the findings as follows.

“The framework can also be used to support standard compliance efforts.” [Participant 1]

“Provides order, structure, guidance, helps SMEs get started, extensible, can be used or adopted by practitioners” [Participant 3]

“Having a single place where all the major standards/frameworks are collected without having to look for them in many different places is certainly a strong point. Prioritization of the different gaps is also a strong point.” [Participant 7]

7.1.2. Perceived ease of use

Most of the participants considered the ASMAS framework easy to use, given the high responses associated with the corresponding statements (statements 4, 5, and 6). The answers to the open-ended questions support the findings as follows.

“Easy to use, particularly if a minimal level of proficiency is already present. Great for figuring out different standards and requirements.” [Participant 4]

“Despite being easier to use than the standards that are incorporated, it may still be useful to provide a tutorial/”getting started” for SMEs in order to get them started using the framework.” [Participant 4]

“Although it provides a very good introduction into the topic, SME might be overwhelmed by the number of questions and tasks.” [Participant 5]

7.1.3. Intention to use

The participants had diverse responses associated with the corresponding statements (statements 7, 8, and 9) regarding the intention to use the framework. The answers to the open-ended questions support the findings as follows.

“It’s really interesting and definitely, I would use it if it’s available.” [Participant 2]

“I would consider using this tool, but now am getting more familiar with ISO 27001 every day and may not be in the target audience anymore.” [Participant 4]

One SME disagreed with all of the statements that were designed to evaluate the intention to use the framework. This SME defines its business as follows: “Provider of a SaaS Solution for Internal Control, Audit Management, ISMS, Governance Risk and Compliance.” As their security maturity is relatively high and they provide security services consultancy, their intention to use the framework is low.

7.1.4. Other feedback and discussions

“The framework could also support subcategories of SMEs under the given categorization” [Participant 1]. We discussed this feedback with the participant; it refers to more tailoring for SME categorization. For example, subcategories might be introduced according to other characteristics of an SME category.

“We have the experience that even if SMEs want to take care of the topic, business needs always have priority, and since they are short on resources, this topic often gets the least attention. Not good, but the reality.” [Participant 5]. This feedback is relatively straightforward, and supports the high-level requirements that we pointed out in Section 4.

“It would be nice if the framework could give an indication of the initial status of the SME (good – sufficient – bad, for example, or a scoring system) and update this each time a new assessment is performed. SMEs might not be able to cope with all the gaps identified by the framework due to lack of time so maybe you could reduce the gaps to just the ones which are more important and leave the less important ones as simple ‘suggestions.’” [Participant 7]. This feedback is about complexity as the participant suggests categorizing the capabilities as mandatory/suggestion. The implementation of the capability levels from A-D in the prototype was designed to help reduce the implementation complexity for SMEs. This can be interpreted as level A capabilities being mandatory to implement and followed by B, C, and D level capabilities.

8. Discussion and Limitations

To summarize, we demonstrated the framework aspects and the high-level requirements by using a software prototype. Concerning validity, the prototype addresses HLR2, HLR3, HLR4, and HLR5. The HLR1 (Easy to use, self-assessment, do-it-yourself) is partially addressed by the Assessment and Measurement aspect, and the Organization aspect in the prototype as the SMEs are exposed to the components (i.e., controls, control categories, and capabilities) of the framework according to their profile that makes the framework easier to use. The demonstration of the perceived ease of use as part of the HLR1 requires SMEs’ involvement as the framework’s end-users. Concerning the technical feasibility, the development of the software prototype shows that the framework can be operationalized. The answers to the open-ended questions and the feedback gathered during the interviews support the high-level requirements presented in Section 4. As discussed in Section 4, designing situational artifacts reduces the cost of adaptation. As the ASMAS framework proposes the set of control groups and capabilities dedicated to SME profiles (i.e., based on their roles in the digital ecosystem), SMEs have the opportunity to have the advantage of cost reduction benefits by implementing only the appropriate controls and capabilities concerning their profiles.

We explained the selection process of the evaluation study participants in Section 7. Due to the high resource intensiveness of the evaluation sessions both on the researchers’ side and the interviewees’ side and the difficulties in finding other SMEs, we had to limit the number of evaluation sessions to 7. Our evaluation study has been conducted through in-depth interviews. Each session has taken at least 1 hour in addition to preparations. During the sessions, we introduced the framework, demonstrated the framework via the prototype, and answered the questions posed by the interviewees. The evaluation sessions are accompanied by an evaluation form sent to the interviewees. We conducted evaluation sessions with SMEs that responded positively to our request. Considering the design of the evaluation study (in-depth interviews), the number of SMEs who participated in the evaluation study is deemed reasonable. More interviews, especially at least one interview with a start-up SME, can be considered future work.

The ASMAS framework can support current initiatives for adopting standards and frameworks (e.g., Cyber Essentials,Citation32 The Center for Cyber Security Belgium SME Guide,Citation33 Center for Internet Security Controls,Citation34 ETSI (global),Citation35 and NIST Small Business Information Security). A scenario illustrating how this can be achieved is given in Appendix 2, Scenario 1. The example scenario is illustrated based on The Center for Cyber Security Belgium SME Guide, but the same approach is applicable to the other standards and frameworks. The framework also enables the adoption of more than one standard and framework simultaneously with the help of a unified set of control categories. It is worth mentioning that adopting or adhering to more than one standard or framework can be a business (e.g., expanding business in other countries) or contractual requirement. In comparison to current initiatives mentioned in the paper at hand, the ASMAS framework does not offer new controls for cybersecurity. The ASMAS framework aims for putting applicable initiatives together within a unified set of control categories and enhancing their use with a situational assessment perspective that incorporated risk and threat information.

Although further research could be conducted to validate the high-level requirements, the evaluation results of the design artifact that addresses the HLRs support their validity implicitly. In addition, the quotes from the interviewees support the validity of the HLRs.

9. Conclusion

Emerging cyber threats, standards, and regulatory requirements place organizations under pressure to implement security measures and provide assurance to regulators promptly. Organizations can establish and improve their security and compliance using maturity assessments and standards. We have formulated our research objective to support organizations to accomplish this with an adaptive instrument. We have proposed an Adaptable Security Maturity Assessment and Standardization (ASMAS) framework to address our research objective. We have presented the high-level requirements of such a framework by adopting an SME perspective. Since SMEs are not homogenous, and their cybersecurity needs differ, we augmented our framework by incorporating SMEs’ roles in the digital ecosystem. We then presented the five aspects of the framework: Organization, Standardization, Risk Management, Assessment and Measurement, and Improvement that facilitate a novel approach to security maturity assessment and standardization through a meta-model and a software prototype. We pointed out how the aspects support the five high-level requirements, and we integrated the aspects to construct a software prototype that demonstrates the validity and applicability of the framework.

We conducted seven evaluation interviews with six SMEs from five countries. We used the evaluation constructs based on the Technology Acceptance Model to explain and predict the utility of the ASMAS framework. The evaluations using a Likert scale (1–5) resulted in average scores of 4.29 for perceived usefulness, 4.14 for perceived ease of use, and 3.62 for intention to use evaluation constructs. When we specifically looked into the perceived usefulness of the framework for increasing the awareness of cybersecurity standardization, 85.7% of the interviewees responded positively (agree and strongly agree). The same result has been achieved for the perceived usefulness of the framework for supporting SMEs to assess and improve their information security and cybersecurity. These results show that SMEs can benefit from the approach of integrating cybersecurity maturity assessment and standardization in the same framework.

This holistic and integrated approach of a multi-aspect security assessment framework that facilitates both standardization and risk management adopting an SME perspective, is the first of its kind. Given the challenges faced by SMEs with limited resources, we believe our holistic approach can facilitate and consolidate SMEs’ security assessment and standardization efforts.

By conducting maturity assessments based on the ASMAS framework, SMEs can assess their security capabilities, identify areas of improvement and increase adherence to standards. SMEs can also use the high-level requirements and the framework to evaluate any maturity model proposed for their use.

A real-world implementation of the framework should include security functions (e.g., users, roles, authorizations). Future research can implement these security functions, and a more naturalistic evaluation can be carried out in a real organizational context. The findings from the evaluation study show that regarding the utility of the framework, generally positive results have been obtained. This research has shown that security maturity assessment and standardization frameworks such as ASMAS provide a much-needed and feasible foundation for a more secure future for SMEs, guided by established best practices.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible with funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 740787 (SMESEC). The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the funding body.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- ISO/IEC. ISO/IEC 27032:2012 - Information technology – Security techniques – Guidelines for cybersecurity [Internet]. 2012 [accessed 2017 Dec 14]. https://www.iso.org/standard/44375.html.

- World Bank. World Bank SME finance. World Bank [Internet]; 2021 [accessed 2021 Aug 17]. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance.

- OECD. The digital transformation of SMEs [Internet]. 2021 [accessed 2021 Aug 19]. http://www.oecd.ilibrary.org/industry-and-services/the-digital-transformation-of-smes_bdb9256a-en.

- Lanz J, Sussman BI. Information security program management in A COVID-19 world. CPA J. 2020;90(6):28–36. [accessed 2021 Jan 6]. http://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=AONE&sw=w&=07328435&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CA632049489&sid=googleScholar&linkaccess=abs.

- UK National Cyber Security Centre. Advisory: COVID-19 exploited by malicious cyber actors [Internet]. 2020 [accessed 2021 Jan 6]. https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/news/covid-19-exploited-by-cyber-actors-advisory.

- North K, Aramburu N, Lorenzo OJ. Promoting digitally enabled growth in SMEs: a framework proposal. JEIM [Internet]. 2019;33(1):238–62. doi:10.1108/JEIM-04-2019-0103.

- European Digital SME Alliance. DIGITAL SME recommendations on COVID-19-recovery [Internet]. Brussels; 2020 [accessed 2021 Jan 6]. https://www.digitalsme.eu/digital/uploads/DIGITAL-SME-Recommendations-on-COVID-19-Recovery.pdf.

- Le NT, Hoang DB. Can maturity models support cyber security? 2016 IEEE 35th International Performance Computing and Communications Conference (IPCCC); 2016. USA; p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/PCCC.2016.7820663.

- Siponen M, Willison R. Information security management standards: problems and solutions. Inf Manag J [Internet]. 2009;46(5):267–70. doi:10.1016/j.im.2008.12.007.

- Yigit Ozkan B, Spruit M. Cybersecurity standardisation for SMEs: the Stakeholders’ perspectives and a research agenda. IJSR [Internet]. 2019;17(2):32. doi:10.4018/IJSR.20190701.oa1.

- Paulk MC, Curtis B, Chrissis MB, Weber CV. Capability maturity model, version 1.1. IEEE Software; Los Alamitos [Internet]. 1993;10(4):18–27. doi:10.1109/52.219617.

- Wendler R. The maturity of maturity model research: a systematic mapping study. Inf Softw Technol [Internet]. 2012;54(12):1317–39. doi:10.1016/j.infsof.2012.07.007.

- Spruit M, Roeling M. ISFAM: the information security focus area maturity model. Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS); 2014, June 9-11; [Internet]. Tel Aviv, Israel: Association for Information Systems; [accessed 2019 Mar 30]. p. 15. https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2014/proceedings/track14/6

- Rabii A, Assoul S, Ouazzani Touhami K, Roudies O. Information and cyber security maturity models: a systematic literature review. Inf Comput Secur [Internet]. 2020;28(4):627–44. doi:10.1108/ICS-03-2019-0039.

- Yigit Ozkan B, van Lingen S, Spruit M. The cybersecurity focus area maturity (CYSFAM) model. J Cybersecur Privacy [Internet]. 2021;1(1):119–39. doi:10.3390/jcp1010007.

- ISO/IEC. ISO/IEC 27001:2013 - Information technology – security techniques – information security management systems – requirements [Internet]. 2013 [accessed 2017 Dec 15]. https://www.iso.org/standard/54534.html

- Cholez H, Girard F. Maturity assessment and process improvement for information security management in small and medium enterprises. J Software Evol Process [Internet]. 2014;26(5):496–503. doi:10.1002/smr.1609.

- Mijnhardt F, Baars T, Spruit M. Organizational characteristics influencing SME information security maturity. J Comput Inf Syst [Internet]. 2016;56(2):106–15. doi:10.1080/08874417.2016.1117369.

- Yigit Ozkan B, Spruit M. Addressing SME characteristics for designing information security maturity models. In: Clarke N, Furnell S, editors. Human aspects of information security and assurance. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 161–74. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-57404-8_13.

- Barlette Y, Fomin VV. Exploring the suitability of IS security management standards for SMEs. Proceedings of the 41st Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS 2008); 2008; Hawaii. p. 308–308. doi:10.1109/HICSS.2008.167

- Manso CG, Rekleitis E, Papazafeiropoulos F, Maritsas V. Information security and privacy standards for SMEs: recommendations to improve the adoption of information security and privacy standards in small and medium enterprises. [Internet]. Heraklion: ENISA; 2015 [accessed 2018 Oct 16]. http://bookshop.europa.eu/uri?target=EUB:NOTICE:TP0215977:EN:HTML.

- Cocca P, Alberti M. SMEs’ three-step Pyramid: a new performance measurement framework for SMEs. Göteborg, Sweden; 2009. p. 13.

- Hudson M. Introducing integrated performance measurement into small and medium sized enterprises [Research Theses] [Internet]. UK: University of Plymouth; 2001 [accessed 2020 Jan 10]. https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk/handle/10026.1/400.

- Storey DJ. Understanding the small business sector. 1994. p. 48.

- Mayer N. A Cluster approach to security improvement according to ISO/IEC 27001. Proceedings of the 17th European Systems & Software Process Improvement and Innovation Conference (EUROSPI’10); 2010; Grenoble, France.

- Yigit Ozkan B, Spruit M, Wondolleck R, Burriel Coll V. Modelling adaptive information security for SMEs in a cluster. JIC [Internet]. 2019;21(2):235–56. doi:10.1108/JIC-05-2019-0128.

- The European Digital SME Alliance. The EU cybersecurity act and the role of standards for SMEs [Internet]. Brussels; 2020 [accessed 2020 Jan 28]. https://www.digitalsme.eu/digital/uploads/The-EU-Cybersecurity-Act-and-the-Role-of-Standards-for-SMEs.pdf.

- ETSI. CYBER; cybersecurity for SMEs; Part 1: cybersecurity standardization essentials [Internet]. 2021 [accessed 2021 Jun 2]. https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_tr/103700_103799/10378701/01.01.01_60/tr_10378701v010101p.pdf.

- Ponsard C, Massonet P, Grandclaudon J, Point N. From lightweight cybersecurity assessment to SME certification scheme in Belgium. 2020 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW). [place unknown]; 2020. p. 75–78. doi:10.1109/EuroSPW51379.2020.00019

- ENISA. Cybersecurity for SMEs - challenges and recommendations [Internet]. [place unknown]: ENISA; 2021 [accessed 2021 Oct 23]. https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/enisa-report-cybersecurity-for-smes.

- SBS, Digital SME Alliance. SME guide for the implementation of ISOIEC 27001 on information security management [Internet]. 2018 [accessed 2018 Sep 2]. https://www.digitalsme.eu/digital/uploads/SME-Guide-for-the-implementation-of-ISOIEC-27001-on-information-security-management.pdf.

- National Cybersecurity Centre. National cybersecurity centre - cyberEssentials (UK). Cyber Essentials [Internet]. 2017 [accessed 2019 Dec 11]. https://www.cyberessentials.ncsc.gov.uk/.

- Centre for Cyber security Belgium. Guide for SME. Centre for Cyber security Belgium [Internet]. 2017 [accessed 2020 Apr 15]. https://ccb.belgium.be/en/document/guide-sme.

- Center for Internet Security. CIS Controls [Internet]. 2018 [accessed 2018 Aug 31]. https://learn.cisecurity.org/20-controls-download.

- ETSI. ETSI TR 103 305 CYBER; Critical Security Controls for Effective Cyber Defence. 2015.

- Paulsen C, Toth P. Small business information security: the fundamentals [Internet]. USA: National Institute of Standards and Technology; 2016. doi:10.6028/NIST.IR.7621r1.

- JAMK University of Applied Sciences. FINCSC – finnish cyber security certificate. Finnish Cyber Security Certificate [Internet]. 2020 [accessed 2020 Mar 3]. https://www.fincsc.fi/en/services/.

- Akinsanya OO, Papadaki M, Sun L. Current cybersecurity maturity models: how effective in healthcare cloud? New Delhi (India): CERC; 2019. p. 211–222.

- Sánchez LE, Villafranca D, Piattini M. Developing a maturity model for information system security management within small and medium size enterprises. Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on Security in Information Systems [Internet]; 2006; Paphos, Cyprus: SciTePress - Science and and Technology Publications; [accessed 2021 Jan 13]. p. 256–66. doi:10.5220/0002502602560266

- Benz M, Chatterjee D. Calculated risk? A cybersecurity evaluation tool for SMEs. Bus Horiz [Internet]. 2020;63(4):531–40. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2020.03.010.

- NIST. Framework for improving critical infrastructure cybersecurity, version 1.1 [Internet]. Gaithersburg (MD): National Institute of Standards and Technology; 2018. doi:10.6028/NIST.CSWP.04162018.

- Peffers K, Tuunanen T, Rothenberger M, Chatterjee S. A design science research methodology for information systems research. J Manage Inf Syst [Internet]. 2007;24(3):45–77. doi:10.2753/MIS0742-1222240302.

- Sonnenberg C, Vom Brocke J. Evaluation patterns for design science research artefacts. In: Helfert M, Donnellan B, editors. Practical aspects of design science. Berlin (Heidelberg): Springer; 2012. p. 71–83. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-33681-2_7.

- Pries-Heje J, Baskerville R, Venable J. Strategies for Design science research evaluation. ECIS 2008 Proceedings [Internet]; 2008; Ireland. https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2008/87

- Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly [Internet]. 1989;13(3):319–40. doi:10.2307/249008.

- Hevner A, March ST, Park J, Ram S. Design science in information systems research. MIS Q [Internet]. 2004 [accessed 2017 Dec 13];28(1):75–105. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2017212.2017217

- Maedche A, Gregor S, Morana S, Feine J. Conceptualization of the problem space in design science research. In Tulu B, Djamasbi S, Leroy G, editors. Extending the boundaries of design science theory and practice [Internet]. Vol. 11491. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 18–31. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-19504-5_2.

- de Vries H, Blind K, Mangelsdorf A, Verheul H. SME access to European standardization [Internet]. 2009 [accessed 2019 Aug 1]:95. https://www.unms.sk/swift_data/source/dokumenty/technicka_normalizacia/msp/SME-AccessReport.pdf.

- Kertysova K, Bhattacharyya K, Frinking E, van den DK, Maričić A, Bhattacharyya K. Cybersecurity: ensuring awareness and resilience of the private sector across Europe in face of mounting cyber risks - study [Internet]. 2018 [accessed 2018 Oct 16]. https://www.eesc.europa.eu/en/our-work/publications-other-work/publications/cybersecurity-ensuring-awareness-and-resilience-private-sector-across-europe-face-mounting-cyber-risks-study.

- Blanchette S, Keeler JKL. Self assessment and the CMMI-AM – A guide for government program managers [Internet]. USA: Carnegie Mellon University; 2018. doi:10.1184/R1/6583784.v1.

- Ritchie L, Dale BG. Self-assessment using the business excellence model: a study of practice and process. Int J Prod Econ [Internet]. 2000;66(3):241–54. doi:10.1016/S0925-5273(99)00130-9.

- Cyberwatching E. Cybersecurity standard gaps analysis [Internet]. 2018 [accessed 2019 Jun 28]. https://cyberwatching.eu/sites/default/files/White-Paper-Cybersecurity-Standard-Gaps-Analysis_Cyberwatching.eu-October2018.pdf.

- Westerlund M. Digitalization, internationalization and scaling of online SMEs. Technol Innov Manage Rev. 2020;10(4):48–57. doi:10.22215/timreview/1346.

- Jones D, Gregor S. The anatomy of a design theory. J Assoc Inf Syst [Internet]. 2007;8(5). doi:10.17705/1jais.00129.

- Winter R. Problem analysis for situational artefact construction in information systems. In Carugati A, Rossignoli C, editors. Emerging themes in information systems and organization studies [Internet]. Heidelberg: Physica-Verlag HD; 2011. p. 97–113. doi:10.1007/978-3-7908-2739-2_8.

- de Vries H, Verheul H, Willemse H. Stakeholder identification in IT standardization processes. USA; 2003. p. 12–14.

- Pöppelbuß J, Röglinger M. What makes a useful maturity model? a framework of general design principles for maturity models and its demonstration in business process management. Finland: ECIS 2011; 2011.

- Shrestha A, Cater-Steel A, Toleman M, Rout T. Benefits and relevance of international standards in a design science research project for process assessments. Comput Stand Interfaces [Internet]. 2018; 60:48–56. doi:10.1016/j.csi.2018.04.011.

- Paulsen C. Cybersecuring small businesses. Computer [Internet]. 2016;49(8):92–97. doi:10.1109/MC.2016.223.

- Zimmermann V, Renaud K. Moving from a ‘human-as-problem” to a ‘human-as-solution” cybersecurity mindset. Int J Hum Comput Stud [Internet]. 2019; 131:169–87. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2019.05.005.

- Sjöström J, Ågerfalk P, Lochan R. Mutability matters: baselining the consequences of design. MCIS 2011 Proceedings [Internet]; 2011. https://aisel.aisnet.org/mcis2011/33

- Pöppelbuß J, Goeken M. Understanding the Elusive black box of artifact mutability. Wirtschaftsinformatik Proceedings 2015 [Internet]; 2015. https://aisel.aisnet.org/wi2015/104

- Mettler T. Maturity assessment models: a design science research approach. IJSSS [Internet]. 2011;3(1/2):81. doi:10.1504/IJSSS.2011.038934.

- Mettler T. A design science research perspective on maturity models in information systems - Alexandria [Internet]. Switzerland: Institute of Information Management, Universtiy of St. Gallen; 2009 [accessed 2020 Jan 10]. https://www.alexandria.unisg.ch/214531/.

- M van S, Bos R, Brinkkemper S, van de WI, Bekkers W. The design of focus area maturity models. In: Global perspectives on design science research [Internet]. Switzerland: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg; 2010. p. 317–32. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-13335-0_22.

- CMU/SEI. Standard CMMI® Appraisal Method for Process Improvement (SCAMPISM) A, Version 1.2: method definition document [Internet]. 2006 https://resources.sei.cmu.edu/asset_files/Handbook/2006_002_001_14630.pdf.

- Mendix. Mendix - Go Make It. Mendix [Internet]. 2021 [accessed 2021 Mar 26]. https://www.mendix.com/.

- ISO/IEC. ISO/IEC 27002:2013 - Information technology – security techniques – code of practice for information security controls [Internet]. 2013 [accessed 2018 Jul 19]. https://www.iso.org/standard/54533.html.

- Marinos L. ENISA threat taxonomy. Greece: ENISA; 2016.

- Cebula JJ, Popeck ME, Young LR. A taxonomy of operational cyber security risks version 2 [Internet]. Fort Belvoir (VA): Defense Technical Information Center; 2014. doi:10.21236/ADA609863.

- SMESEC. About SMESEC [Internet]. 2017 [accessed 2019 Jun 20]. https://www.smesec.eu/about.html.

- GEIGER Project. GEIGER - Cybersecurity for SMEs [Internet]. 2020 [accessed 2022 Aug 4]. https://project.cyber-geiger.eu/.

- European Commission. SME definition. Internal market, industry, entrepreneurship and SMEs - European commission [Internet]. 2016 [accessed 2021 Aug 10]. https://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes/sme-definition_en.

Appendix 1:

Screenshots of the Prototype

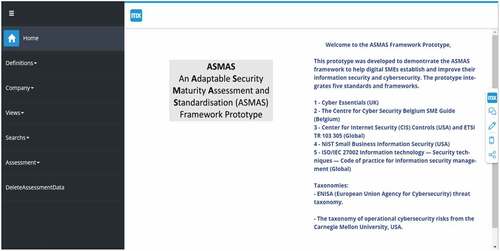

Home Screen:

On the Home screen, we see an introduction text that explains the standards, frameworks, and taxonomies included in the knowledge base of the prototype. In the navigation menu on the left side of the screen, there are menu items that correspond to the functions implemented in the prototype.

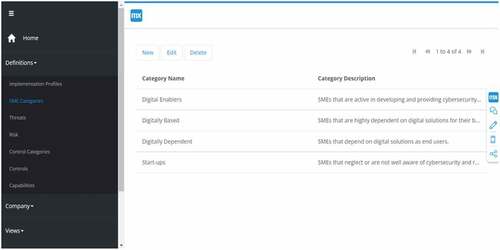

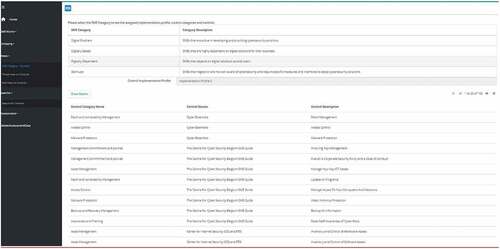

Definitions: SME Category

Using this function, the SME categories and the definitions of the SME categories can be defined. As can be seen here, it is always possible to add more categories or change/delete the existing ones. This is ensured by maintainability by design high-level requirement.

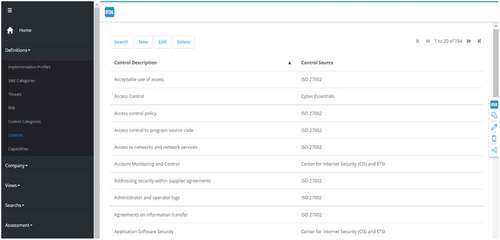

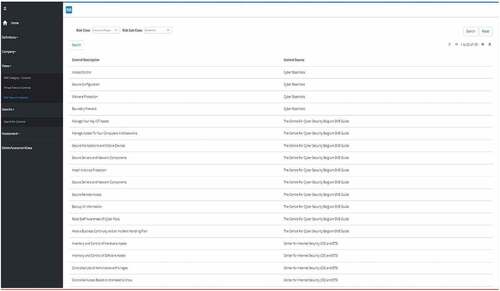

Definitions: Controls

Using this function, controls from standards and frameworks can be defined. Control Source is the name of the standard or the framework.

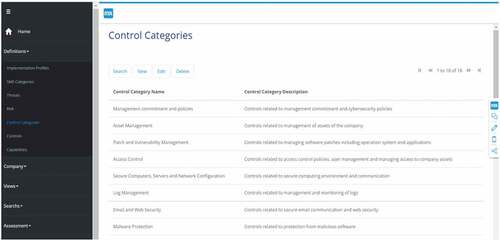

Definitions: Control Categories

Using this function, control categories from standards and frameworks can be defined. Every control belongs to a control category.

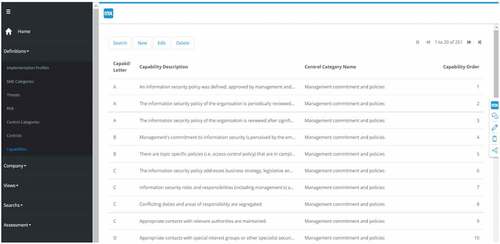

Definitions: Capabilities

Using this function, capabilities per control category can be defined. Capabilities are derived from the implementation guidance presented in standards and frameworks. Capabilities belong to a Level characterized by a letter (i.e., A, B, C, D, E) and an implementation order characterized by Capability Order. The Capability Order is the implementation order of the capabilities associated with a control category.

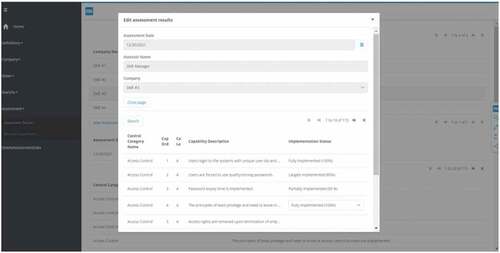

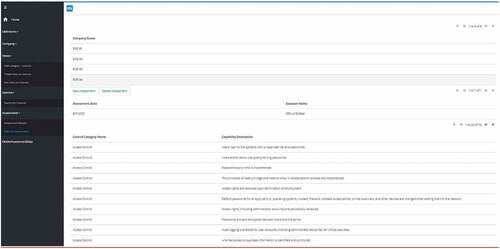

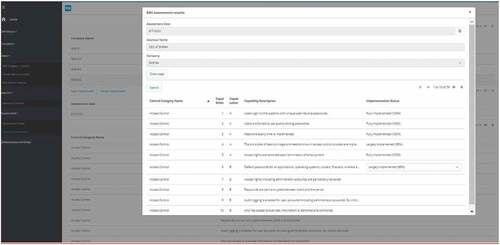

Maturity Assessment

With this function, organizations can assess their cybersecurity maturity by evaluating the capabilities that are applicable to their organizational profile. The assessment is done by giving ratings to the implementation status of the capabilities. Implementation status can be “Fully Implemented,” “Largely Implemented,” “Partially Implemented” or “Not Implemented.” A capability can also be “Not applicable” to an organization. In the screenshot, we also see the information about the assessment (i.e., Assessment date, assessor, company name, and the category). Several assessments can be performed and saved in the prototype. It is to be noted that SME#3 is a Digitally Dependent SME, therefore, only a subset of capabilities (115 out of 251) are shown in the assessment. In case of a Start-up SME, the number of capabilities that are shown to the user reduces to 79 out of 251.

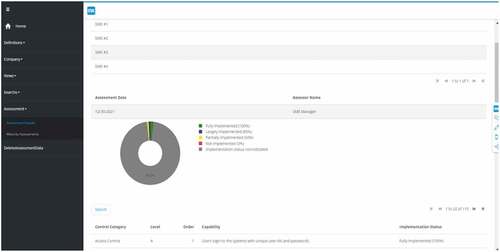

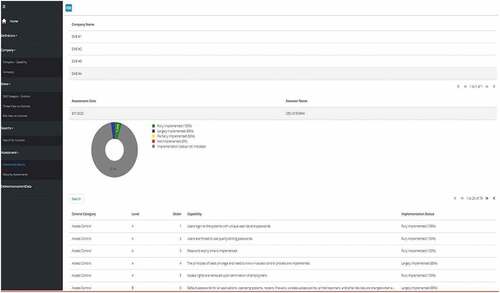

Maturity Assessment Results

In this screen, organizations can review their previously done assessment’s results. The pie chart illustrates the implementation status percentages. Although the current implementation in the prototype presents the whole assessment in one pie chart, a pie chart per control category can also be prepared.

Appendix 2:

Example Scenarios

Scenario 1: The framework can support current initiatives for adopting standards and frameworks

The Center for Cybersecurity Belgium SME Guide example:

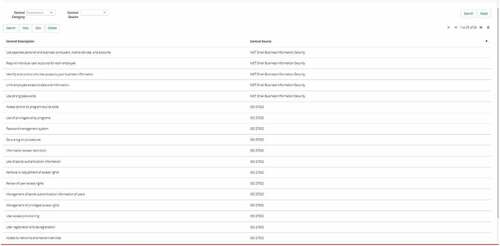

SMEs can see the controls that come from the Center for Cybersecurity Belgium SME Guide associated with their Digital SME profile. The figure below shows 8 controls associated with the Digitally Dependent SME profile.

SMEs can select a risk class and sub-class and see the controls that come from the Center for Cybersecurity Belgium SME Guide. In the figure below, the controls associated with the “Actions of people” class, and “Deliberate” risk sub-class can be seen.

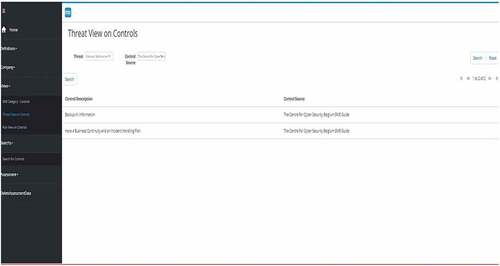

SMEs can select a threat and see the controls that come from the Center for Cybersecurity Belgium SME Guide. In the figure below, the controls associated with the “Failure/Malfunction” threat can be seen.

Scenario 2: The framework can support capability assessment tailored to SME Profile

SMEs can create an assessment for assessing the capabilities associated with their Digital SME profile. The figure below shows an assessment that is created for SME#4 which is a Start-up SME. As can be seen from the figure, the number of capabilities shown in the assessment is 79 out of 251.

SMEs can carry out an assessment of the capabilities associated with their Digital SME profile. The figure below shows the assessment partially completed by SME#4.

SMEs view the results of the assessments that they have carried out. The figure below shows the results of an assessment that has partially been completed by SME#4.

Appendix 3:

Illustration of the Controls and Capabilities for a Control Category

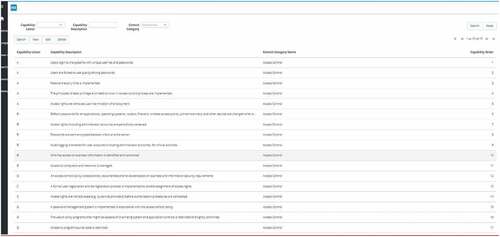

In the prototype, we investigated the standards and frameworks and proposed a unified set of 18 control categories. Each control category (e.g., Access Control) is populated with controls from different standards and frameworks. As expected, there are similar or duplicate controls in each control category. From a capability assessment and improvement point of view, we investigated the controls in the standards and frameworks and proposed a number of capabilities to achieve the objective of the control category. Each capability is associated with a level that provides a progressive approach for improvement planning and an order to provide guidance for implementation planning. The following figure presents the controls from the standards and frameworks for the Access Control control category. There are 24 controls in the Access Control control category.

The investigation of these controls resulted in 17 unique capabilities, as presented in the following figure. Each of the capabilities is associated with a letter representing the capability level (A, B, C, D) and an order (1 to 17). Deriving the capabilities by investigating all the controls in a control category eliminates the duplicate controls and results in a unified set of capabilities to achieve the objectives of the control category.