Abstract

In this article, we use narrative inquiry to examine one teacher’s experiences of participating in an inquiry-based teacher writing group. Narrative inquiry centers teachers’ stories, revealing the complexities of teaching and writing identities. We argue that, despite the “cover story” of a binary writing identity, teachers’ stories about their lives and their practice reveal much more complex writing and teaching identities. Inquiry-based professional learning experiences invite teachers to bring in their lived experiences and collaborate with one another to (re)story themselves as professionals, writers, and teachers of writing. Rewriting these identities and crafting new storied selves is an important part of professionalizing teaching, fostering teacher agency and supporting sustained professional learning. The findings demonstrate the need for a re-envisioning of teachers’ positioning in professional learning, restructuring professional development to value the work teachers can produce together when given an opportunity to engage as learners in their everyday school contexts.

In this article, an inquiry-based teachers’ writing group serves as the basis for examining how one teacher restoried her writing identity, writing practice, and professional learning through active participation in an inquiry-based teaching writing group. Through narrative inquiry, this examination extends the literature on professional learning by understanding stories as a way to foster teacher agency and cultivate reflection and action on meaningful professional learning. The opportunity for change is powerful because teachers “teach profoundly what we are, what we know, what we value, and what we believe” (Vinz, Citation1996, p. 185). In this article, we argue that as the work of inquiry-based writing shifts, adds to, or rewrites one’s identities, knowledge, values, and beliefs, this work can also shift, add to, or rewrite one’s professional learning.

Teachers’ storying professional practice

The stories that teachers tell about their own practice—those that position an individual as more or less a part of a community or identity position—are important. But they are often undervalued or silenced, as admitting uncertainty or the desire to experiment and take risks can make one vulnerable in evaluation systems and rankings (Taubman, Citation2010). Teachers are expected to already know when they take responsibility for a classroom. Their stories are considered finished, rather than being continuously revised and coauthored by their developing expertise, reflexive practices, or interactions with students and colleagues. The pervasive audit culture of education (Apple, Citation2004) constrains teachers; conversely, providing a space for inquiry, writing, and discussion opens up other possibilities for stories, questioning, and identity construction.

In this article, we focus on one teacher’s experiences participating in an inquiry-based teacher writing group. Using narrative inquiry (Chase, Citation2011; Connelly & Clandinin, Citation1990), we examine the stories this teacher-writer told about her practice, her life, and her writing identity. This orientation to analysis interrogates this teacher-writer’s stories and identities as they are enacted, resisted, laminated, and performed individually and collaboratively. Our focal participant highlights the restorying that is possible when colleagues join together as inquiry-based writers, disrupting the previous ways they collaborated or engaged in professional development. In the following sections, we discuss our theoretical framing through conceptualizing professional learning, inquiry communities, and teachers’ writing identities. Together, these bodies of literature demonstrate the power of teachers’ stories.

Conceptual framework

Professional development tends to focus on content knowledge and instructional methods without opportunities for teachers to write or learn more about themselves as writers (Bomer et al., Citation2019; College Board, 2003; Norman & Spencer, Citation2005). Inquiring as a writer affords examination of one’s own identities as fluid and complex which can offer insight into the identities of others and the contexts in which teaching and learning take place. By challenging these dominant conceptions of professional development, we argue that professional learning driven by teachers’ inquiries and shared stories provides a more meaningful and enduring learning experience that has the power to shape both teachers’ identities and knowledge of practice.

Teachers’ professional learning

How teachers’ professional knowledge is defined directly relates to how teachers and their professional learning is valued, encouraged, and supported. Cochran-Smith and Lytle (Citation1999) provided a framework for conceptualizing the development of teacher learning in communities by arguing that teacher learning is socially constructed, stemming from and disseminated by teachers themselves. By framing professional learning as developing knowledge-of-practice, Cochran-Smith and Lytle reorient what knowledge means and how it is enacted within the teaching profession. However, much of the professional development for teachers is still animated by previous notions of teacher learning, what Cochran-Smith and Lytle termed knowledge-for-practice and knowledge-in-practice, which limits understanding of teachers’ professional learning to either formal knowledge or practical knowledge, both emphasizing external expertise rather than teachers’ own developing knowledge.

Knowledge-of-practice, however, positions knowledge-making as a “pedagogic act” through which teachers’ knowledge is socially constructed based on their experiences, prior knowledge, and dynamic array of resources. Thus, knowledge-of-practice is grounded in the assumption that teachers “make problematic their own knowledge and practice as well as the knowledge and practice of others, and thus stand in a different relationship to knowledge” (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, Citation1999, p. 273). This knowledge-of-practice orientation involves teachers learning collaboratively in inquiry communities or networks (Butler & Schnellert, Citation2012; Dyson, Citation2020; Timperley & Alton-Lee, Citation2008), a key element similar to the National Writing Project in the United States (Khachatryan & Parkerson, Citation2020; Whitney & Friedrich, Citation2013), teacher researcher-based professional learning networks (e.g., Juuti et al., Citation2021; Rogers et al., Citation2005), and professional collaborative communities (e.g., New York Collective of Radical Educators, n.d.; Teacher Action Group–Philadelphia, n.d.). In such inquiry communities, all group members, regardless of hierarchical positioning, engage in the same intellectual work together, inquiring into the complex and messy work of teaching, learning, and social change. Inquiry groups, with an emphasis on teacher collaboration, have been posited as a primary mechanism for schools to disrupt the historical isolation of teaching, serving as both the means to achieve particular long-term goals and as ends in themselves.

Practitioner inquiry, then, requires sufficient time and duration, discourse of rich, descriptive talk and writing, and a sense of purpose to make consequential change. All the work of an inquiry community is ultimately in service of a broader aim: “enhancing educators’ sense of social responsibility and social action in the service of a democratic society” (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, Citation2009, p. 58). We argue that this possibility hinges on teachers’ beliefs about who they are personally and who they are professionally. Therefore, identity work must be at the center of teacher inquiry and professional learning.

Writing as professional learning to restory teacher identities

Gee’s (Citation1989) concept of Discourse as an “identity kit” (p. 51), a socially situated identity and a way of being in the world, is useful for considering how teachers’ writing and teaching practices are animated by the Discourses that circulate in their classrooms, school, and society. Teachers may position themselves and their colleagues in relation to the dominant Discourses of teaching and writing to which they have access. Bomer et al. (Citation2019) and Kline et al. (Citation2021) utilize Ivanič’s (Citation2004) framework to examine the discourses about writing that teachers have access to: skills, creativity, process, genre, social practices, and sociopolitical. Both groups of scholars acknowledge the significant - and underutilized - potential for disruption and transformation by supporting teachers in accessing and mobilizing social and sociopolitical discourses. Teachers’ experiences and interactions with others around writing, such as with their colleagues, students, administrators, and curricular materials, may lead to constructed knowledge that both defines and changes the way they participate in the world (Bomer et al., Citation2019; Cremin & Baker, Citation2014; Kline et al., Citation2021). Through writing, teachers can construct an understanding of themselves in interactions with their students, which then shapes and changes the next interaction (Dawson, Citation2017; Whitney & Friedrich, Citation2013).

Thus, teachers’ writing and teaching identities can be understood as fluid social constructions. Gee’s (Citation1989) concept of an “identity kit” can be paired with Moje and Luke (Citation2009) metaphor of identity-as-narrative; identities are constructed in and through the stories people tell about themselves and their experiences. Teachers’ identities do not remain static upon entering the profession; like stories, they continue to shift through revision as they are shaped by colleagues, students, and school contexts. The concept of “storied selves” delineates the process by which people arrive at their sense of selfhood and social identities (Luttrell, Citation1997). Thus, restorying is an act of agency to reshape one’s narrative, particularly in response to marginalization or silencing (Thomas & Stornaiuolo, Citation2016). We connect this to teachers’ experiences of deprofessionalization and the ways that audit culture and dominant Discourses of teaching so often narrate teachers’ stories for them. Sharing narratives about themselves provides teachers a way to hold together multiple experiences, constructing and claiming an identity as a particular kind of writer or learner.

While identity-as-narrative metaphors clarify the “what” of identity, identity-as-position metaphors clarify the “how” of building identities (Moje & Luke, Citation2009). Such positioning refers to the process of forming identities, “the ways people are cast in or called to particular positions in interaction, time, and spaces, and how they take up or resist those positions” (p. 430). Teacher-writers, then, construct their identities across the spaces, times, and interactions of their careers. They are called to particular positions, such as “model writer,” and might take up those positions or resist them. Identities can “thicken” over time as a result of the multiple subject positions experienced in the practice of everyday life (Holland & Leander, Citation2004). For example, an identity as “not a writer” may thicken through experiences of negative feedback as a student. Laminations also help to explain how identities can appear stable, yet are also multiple and, at times, contradictory (Holland & Leander, Citation2004); laminations are built through the layering of identity positions over one another, so identity-as-(layers of)positions carries with it the histories of past experiences, and those layers may peek through in the enactment of identities.

In taking up the knowledge-of-practice view of teacher knowledge, teaching and identities cannot be separated from the multiple (gendered, raced, classed) subject positions that individuals take up, or the power asymmetries that are inherent in school contexts and society at large (Chavez, Citation2021; Love, Citation2019; Picower, Citation2021) . This is particularly relevant in a writing space where participants are storying writing identities as a part of a feminized profession within an audit culture that works to constrain what stories are sayable both as writers and as practitioners (Lagemann, Citation2000; Lensmire & Schick, Citation2017). And if identity is positioned at the center of professional learning rather than particular knowledge, this has implications for what the spaces for teacher learning might look like. Rather than a procedural schooled model of professional learning in pursuit of narrow ends defined by test outcomes, a model that centers the constant becoming of fluid identity work might implicate a space for teacher learning that is also more fluid.

While the literature on teachers’ professional learning, inquiry communities, and writing to restory identities has furthered understanding of how teachers work and learn together, less is known about how teachers’ stories are told and retold in these communities, revealing additional complexities of teachers’ writing identities. This paper examines an inquiry-based teacher writing group that sought to explore writing—the act of writing, the texts of teacher writing, and the identities of teachers as writers as a form of professional learning. We focus on one participant, Belle, a veteran elementary math coach with experience as a classroom teacher and administrator, and a self-proclaimed “bad writer” at the outset of the study. Belle’s story highlights the importance and potential power of a professional learning approach that provides meaningful opportunities for inquiry, even across content areas. Through engaging and sharing in the group, Belle’s teaching and coaching practice became a text for inquiry alongside the texts she wrote, and she restoried her own identity as a writer and learner. In the following sections, we will share our methodology for analyzing Belle’s participation in the writing group and its impact on her identities as a writer and a learner. Then, we will share Belle’s story and discuss the implications it has for other educators and professional learning more broadly.

Methods

Using narrative inquiry (Chase, Citation2011), we analyzed the construction and reconstruction of the stories of our focal participant, Belle, in and around the acts of writing and teaching. Narrative inquiry revolves around an interest in life experiences as narrated by those who live them. Narrative is a distinct form of discourse involving “the shaping or ordering of experience, a way of understanding one’s own or another’s actions, of organizing events and objects into a meaningful whole, of connecting and seeing the consequences of actions and events over time” (Chase, Citation2011, p. 421). A focus on narrated lives allows consideration of the ways a person is constantly “living, telling, retelling, and reliving stories” (Connelly & Clandinin, Citation1990, p. 4). The stories that we tell ourselves and others play a role in how individuals make and continuously re-make meaning. Meaning-making, or making experience of events, is discursive and happens through language and narrative (Smith & Watson, Citation2010), then conveyed to others through storytelling. As stories are told, “discursive patterns both guide and compel us to tell stories about ourselves in particular ways” (Smith & Watson, Citation2010, p. 32). Within the writing group, Belle constructed multiple narratives through her writing and conversations with other writing group participants. While all group participants were part of the larger research study and data set, in this paper we use narrative inquiry to provide an in-depth analysis of Belle, in particular, which allowed us to focus on all aspects of her participation. With this in mind, we posed the following research question: How was one teacher’s writing identity, writing practice, and professional learning restoried through active participation in a teacher writing inquiry group?

Research site

Located in a culturally and linguistically diverse neighborhood, P.S. 999 serves a very diverse population of Pre-K-5 students. Approximately 90% of students qualified for the Free and Reduced Lunch program, one third (31%) of students were English Language Learners, and over 20 languages were spoken by students and staff. With only 28% of students in Grades 3-5 scoring Proficient or higher on the state achievement test in English Language Arts the year prior, P.S. 999 had received additional attention as a “focus school” from the district superintendent, heightening anxiety in the school community over test scores. Teachers discussed limited professional learning, lowered morale, and a segregated curriculum for marginalized students. The Discourses of teacher “effectiveness” and accountability that permeated the school manifested in tensions for teachers, who sought to perform an idealized teacher identity that conformed to the demands of their context.

Administrators explicitly articulated a goal of professional development and study as “essential” for faculty. This was enacted through cycles of coaching with school-based curriculum coaches, weekly grade-level collaborative planning blocks, and district-required weekly afterschool professional development sessions. However, most of these professional learning experiences retained a knowledge-for-practice orientation; they were often mandated sessions planned without teacher input, allowing for little autonomy or reflexivity. Thus, the inquiry-based teacher writing group disrupted the contextual norms of professional learning and offered an alternative space for teachers to engage with one another and their work differently.

Participants

All faculty at P.S. 999 were invited to join the inquiry-based teachers’ writing group. The invitation indicated the meeting schedule and the inquiry-based structure, which consisted of…. Participants were aware that, within the time and space of the group, they could take up writing projects of their choice for their own purposes, including drafting mentor texts for use in the classroom and/or writing for personal or sociopolitical purposes. Participants included three upper-grade classroom teachers, two instructional coaches, one administrator, and Amy, who worked as a staff developer in the school for three years prior to the study. Therefore, she had already established ties to and knowledge of this research site. Each participant selected their own writing project and process, and the group decided collaboratively on ways of working and inquiring together. Moving fluidly between the roles of author and audience, all participants shared written pieces with partners and the whole group.

Four of the original seven participants (Valerie, Luis, Belle, and Amy) continued throughout the entire study, attending meetings and completing their writing projects. Luis, a fourth-grade teacher, first proposed the idea of a writing group to Amy over lunch during staff development. He expressed the desire to participate in a teachers’ writing group to work on his own writing and be in community with other teachers. Belle and Valerie joined him as the inquiry group pursued writing projects.

As previously noted, Amy was a participant in the writing group. Kelly joined the study after data collection and contributed an outsider perspective on the data as a critical friend (Costa & Kallick, Citation1993) and coauthor. Both authors are former classroom teachers who were doctoral students in the same city as P.S. 999 at the time of data collection and currently work as teacher educators in literacy. Both authors identify as cisgender, middle-class white women and acknowledge that our positionality shapes our analysis.

Focal participant

Belle, a veteran educator and the school’s math coach, is a woman of Jewish heritage who is passionate, politically engaged, and known for her self-deprecating wit. Belle worked closely with Luis, the fourth-grade teacher, planning and implementing math curriculum in addition to attending and planning math professional development. Belle’s professional role included coaching and modeling in classrooms, working with groups of students, and planning and leading meetings and professional development sessions. Through narrative inquiry, we explored the ways that Belle storied and re-storied writing and teaching. Belle was selected as our focal participant due to the significant revision her writing identity underwent, and her self-awareness in narrating the story of this change. While all participants restoried their identities in different ways, our goal is to use Belle’s example to illustrate what is possible when teachers engage in writing as a community, even (or perhaps especially) when they work across content areas.

Data collection

Data collection included participant observations, semi-structured individual conversations, field notes, memos, and document analysis. During writing group meetings, the Amy joined as a participant observer to engage in the writing process alongside the participants. Meetings were held every other week over the course of six months; each of the ten meetings was approximately an hour and half in duration. In the interest of studying life experiences as narrated by those who lived them, meetings were recorded and transcribed so that the exact language all participants used to narrate their writing and teaching experiences was captured and turn taking, interactions, and the co-creation of stories within the group were noted.

In addition to group meetings, one-on-one conversations with each of the writing group members were a part of data collection. These conversations were semi-structured (Spradley, Citation1979) to encourage participants to pursue their lines of thinking freely; two to three individual conversations were completed with each participant, each ranging from an hour to two hours in length. Field notes were written after each group meeting and interview. Finally, other documents for analysis consisted of writing that participants completed as a part of the writing group. These included “finished” pieces and plans, drafts, and/or revisions of ongoing projects. Some were created in the space and time of group meetings, while others were written in individual contexts and shared during a group meeting.

Data analysis

Drawing on Riessman’s scholarship (Citation2008), we began with thematic analysis, leading to dialogic/performance analysis in order to attend to context and interaction. Thematic analysis is content-focused and aims to examine the meaning a narrative communicates. We examined first the interview transcripts, then meeting transcripts, for narrative units, attempting to keep each story intact, looking at both what was spoken and the “overall structure of each story” (p. 68). In determining the narrative units, we began from Riessman’s definition of “a bounded segment of talk that is temporally ordered and recapitulates a sequence of events” (p. 116), and aimed to preserve sequences rather than coding segments. While the process of determining the boundaries of stories is interpretive, it was important that we not fracture these narratives into decontextualized bits of data. For the purpose of this study, we used thematic analysis to identify the stories Belle told about herself as a writer, looking first within, and then across stories to determine themes, including the identities and positions she both took up and resisted as well as the ways in which she positioned herself and others within these stories. Once the narrative segments were identified, we first looked within each segment to explore the meaning Belle conveyed; we then looked across stories to determine themes. We identified themes through multiple and overlapping pathways, including declaration, frequency, and similarity.

While thematic analysis is especially useful for noting thematic threads in the data, it neglects meaning as constructed and negotiated within a particular context and assumes too direct a lineage between story and intentionality. Little attention is paid to the context in which the story is told, language choices, and form. Thus, we also used dialogic/performance analysis to interrogate how talk among speakers was interactively produced and performed as narrative (Riessman, Citation2008). Specifically, this approach asks who is being spoken to, when, and why, considering the purpose for which the narrator is telling the story. This necessitates an explicit consideration that stories are “composed and received in contexts—interactional, historical, institutional, and discursive—to name a few” (p. 105). As the site-based context of the study was integral to shaping the interactions, discourses, and roles of all members of the writing group, a consideration of context was imperative. This approach allowed us to consider the impact participation in the group had on Belle, and the ways she co-created stories with others. We coded instances of Belle’s interaction with other group members during meetings, and analyzed the ways in which Belle positioned herself and others, and the ways others positioned her, within those co-created narratives. Dialogic/performative analysis allowed us to consider the way Belle narrated herself in the context of one-on-one interviews as compared to within the context of the group meetings and fostered understanding of Belle’s identities as multiple, fluid, and even sometimes contradictory.

Using both thematic and dialogic/performance analysis, we examined how Belle’s participation in the teacher inquiry group restoried her writing identity, writing practice, and professional learning. As we coded, we were able to bring in an insider perspective from Amy and an outsider perspective through Kelly lens. Kelly was able to ask challenging questions and provide a different perspective on data (Costa & Kallick, Citation1993).

Findings

Pushing beyond cover stories

Though the literature conceptualizes writing identities as fluid and complex, teachers often position themselves on one side of a binary: “a writer” or “not a writer.” As Belle illustrates, these binary identities work as cover stories, constructed narratives complicated or even contradicted by the lived experiences of teacher-writers. Below, we analyze Belle’s cover story, which she shared in her first interview, and the more complicated experiences and actions that disrupt it.

In elementary school, it was book reports…I was in a K-8 school, so probably some time, seventh and eighth grade through high school, it became about essays on tests and how quickly can I spit back what it was, as short as possible. And then in college… writing 101 and more essay stuff. And graduate school, we had to write real papers and I started to actually proofread things. And then the math stuff that we talked about is informational.

When I was an AP for a couple of years, at the time, the observations were these full one-page narratives which were freaking torture for me to write because I was crazy obsessive-compulsive about them. But they also… if the observation was on a Monday, if they didn’t have their full write-up by Wednesday, I was having a meltdown because I can’t have things on my plate.

So, there was this crazy anxiety associated with it, which is the reason I never liked to do papers…So that’s pretty much my writing history. It’s very limited.

Belle was initially the group member who held the most negative view of writing and herself as a writer. As she described her writing history above, she remembered the different kinds of writing she had done in each stage throughout her life. Her writing, despite beginning in elementary school and running to the present (her “math stuff”), was described as “limited.” Despite her skills being, at minimum, competent enough to take her through graduate school and employment, she associated writing with negative emotions; the terms “torture,” “crazy anxiety,” “obsessive-compulsive,” and “having a meltdown” highlight Belle’s perception of her writing experiences. Her cover story of a “limited” writing life was contradicted here, but the emotional nature of these experiences seemed to peek through for Belle and obscure the ways she had successfully used these practices throughout her life. As she had experienced these positions of anxiety in the past, she came to imagine her future self moving within these positions as well.

Later on in a group meeting, Belle outlined a distaste for the physical act of writing as well as a sense of anxiety over the products she produced. Belle’s physical actions as a writer, and the pain those actions evoke, contributed to her cover story as “not a writer.” While Belle took on multiple positions here, acknowledging there were parts of the process she did not mind and she could be in the “right mood,” she represented herself as “hating” the act of writing. Her perceived lack of writing experience and acumen made Belle more conscious of her participation in the study, and she often voiced her concerns that she would not be a productive participant or live up to the expectations of the group. The excerpt below is from her first interview with Amy when she was asked if there were particular people who influenced her as a writer:

Belle: No, because I had almost no… Again, any writing I did, I did because I had to do it. There was literally no writing in my life. Now that I’m talking about it, it’s just so interesting, because reading I can talk a lot about, even if I wasn’t taught it explicitly, I can talk a lot about influences in reading, in sitting with my father, in his big giant chair. He would fall asleep half the time. I have some of the books that he used to read to me over and over, as a really, really little kid, but writing, no. This isn’t working well for your [study].

Indicating that there “was literally no writing in [her] life,” Belle rejected a past identity as a writer in its entirety. She positioned herself clearly on one side of the binary identity, indicating that she had difficulty talking about writing and making a comparison to her own feelings and memories about reading. This seemed to be an identity that had laminated with retellings over time, as Belle described engaging in “no” writing as a child and a student, and continuing to avoid the task as an adult. This self-declaration is a refusal of the “ideal writer” that Belle felt pressure to embody, not only in talk but in the production of her written products.

This positioning threads through Belle’s confidence in terms of her written products. She described an “intangible” quality of effective writing that she was sometimes able to capture, while other times it felt unreachable; thus, sometimes, she was successful in a writing task, and other times she was not. Again, her comments suggested that writing was not solely an autonomous skill for Belle, but one with a deeply emotional component. It was also an indication that her identity in activity was actually much more fluid; her successful writing experiences intermixed with the times she fell short. For Belle, this process—when writing goes well, when it does not, and why—seemed to have no discernable pattern; however, she felt it could be the result of a lack of practice. Belle connected her perceived lack of practice and fluency in writing with ineffective or unsatisfying products. Falling short of this ideal, even only sometimes, is enough to limit Belle’s ability to narrate herself as a writer. As a structured, linear thinker, she aspired to follow the steps of a process to achieve a “professional” product consistently. Yet, a structured, linear writing process did not work for her in a reliable way that could be replicated across pieces.

As a math coach and self-professed non-writer, Belle was perhaps initially an unlikely candidate for participation in the writing group. Her entrance into the writing group was, admittedly, reluctant. She recounted:

I had no intention of being part of it, and then…Luis said something. I’m like “Yeah, I can’t be a part of that, that’s so hard.” He was like, “Well, that’s why you should be.” I started to think about all the people saying, “I don’t want to do a math problem because it’s hard and I don’t like math…” I’m like, “Yeah, Belle, practice what you preach.” It was really about stepping up to the plate for myself, not that I think anyone is going to know other than Luis and Valerie and you. It’s kind of like, “Yeah, you talk the talk, you better walk the walk.” That’s really, really what brought me to the group.

Luis, then, offered a subject position to Belle, calling on her “good teacher” identity, proposing that she was a particular type of subject (one who serves as a model for others and backs up her words with actions). Belle, in turn, had to decide whether to accept or refuse that position. The commitment, for Belle, was both about social obligations (meeting a friend’s challenge and honoring a commitment she made to Amy) and about living a life in line with her own values, living up to the self as interpellated (Althusser, Citation1971). As a math coach, Belle had often encouraged reluctant teachers to embrace math work, even when they were “not math people.” Faced with a similar challenge to her own identity, Belle felt obligated to follow her own advice; with an understanding of math identities as fluid but her own writing identity as binary, Belle was pushed to reconsider her understanding of herself as a non-writer. In other words, her role as a coach prompted her to consider her role as a learner and a practitioner of writing. Her multiple identities began to “overlap and layers [began] to congeal across identity compartments, thus producing hybrid identities” (Hall, Citation1996, as cited in Moje & Luke, Citation2009, p. 431). When asked about her goals for the group’s work, then, Belle was committed to engaging and practicing, but uncertain of her own abilities. In an interview, she stated “I made a commitment to you, and I’m really going to try to stick with it, and come up with some finished product. How good it will be I don’t know…”

Belle’s direct acknowledgment of the study, as seen in the beginning of this excerpt as well as the excerpt that began this section, spoke to Amy’s positioning as well as Amy and Belle’s relationship. She wanted to “do well” in the study and compared herself to her conception of what Amy “wanted” from her, an idealized interviewee; this provides an important example of the ways dialogic/performative analysis allows us to attend to the context and audience for which a story is told. Belle’s comments implied that she wanted to do well for Amy because of their existing relationship (“I made a commitment to you”); she felt as though she was somehow letting Amy down because her writing experiences were “not meaty” enough. She drew attention to her perceived “novice” status as a writer in her goal to write in a way that did not sound “like a two-year-old wrote it.” Her comments positioned her as a “good colleague,” while at the same time distancing herself from an identity as a writer.

Rewriting a writing identity

While many teachers narrate themselves on one side of the writing identity binary or the other, Belle’s story illustrates that these identities are much more complicated. We argue that teachers rewrite their writing identities through inquiry and collaborative experiences alongside colleagues that encourage agency and autonomy. In the following vignette, a vivid example of the co-construction of a narrative, we highlight the ways that Belle’s sense of her own identity was shifting, and the ways her enactment of that identity with others was shifting as well.

Approximately two-thirds of the way through the group’s time together, a seemingly unremarkable moment occurred; as we were getting ready to leave, the group meeting over for the day, Belle was rushing to get home for her typical Tuesday evening laundry regimen. All the group members knew that she rushed home every Tuesday for this routine and would not miss or change it under any circumstances. On this particular day, Luis teasingly told Belle that she should write about her laundry routine since it was so important to her. Belle laughed the comment off in the moment and we all parted ways. However, when Belle took Luis’s suggestion and put it into action, this unremarkable moment and the effect it ultimately had on Belle became a critical incident for analysis, one that shifted both Belle’s writing and the story of her identities.

One day not long after, Amy was in the school for staff development, with no group meeting planned, and Belle asked her to visit when she could. When she did, Belle began recounting her success in writing about her “laundry anxiety.”

I was thinking about this whole…the way school works. You’ve got forty-five minutes, and you need to do your draft. And in another forty-five minutes you need to figure out your math problem. And in another forty-five minutes you…And it’s like, brains don’t work that way. They just don’t. I happened to have this idea, or Luis. I don’t even know who had it. I thought about it on the train, I sat down, and it worked out. I happened to just write it, while in between going up and down to get my laundry and eating, in one sitting pretty much. But you know the [letter] is taking me months and months and months. And it’s not very good.

Belle referred here to the co-creation of the story, sharing some of the credit with Luis by indicating she was not sure whose idea it was and acknowledging the spontaneity of the piece. She also contrasted this new writing piece to her previous project. While she was previously working on an informational letter to the School Chancellor, an idealized “professional” text, this teasing interaction led to a writing piece that began:

I am anxiety prone, a Nervous Nellie, a worrywart, the kind of girl who always has butterflies in her stomach. And yes, I hear you, that is one of the pervasive laments of our culture…. But my brand is rather unique. I have a huge case of LAUNDRY ANXIETY. Joking—I am not. Here’s the deal.

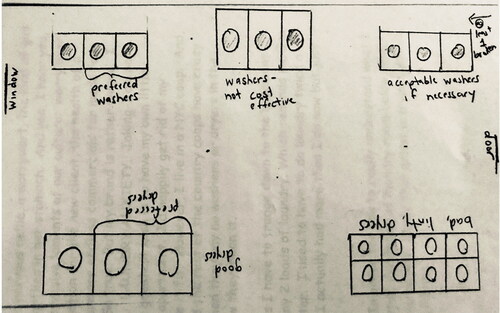

This essay came complete with a diagram that indicated preferred washers and dryers and the many challenges of the laundry room, such as linty dryers and washers that were just not cost-effective ().

Finding a new genre to write in—essays that incorporated her self-deprecating humor—opened up Belle’s writing in a new way. Luis’s casual comment tacitly gave Belle permission to take on a new identity as a writer, one that would not have been possible without the group interaction. The moment of teasing, then, emerged as a moment of irreverence or interruption in the work of the group (Lensmire, Citation2000), in which Luis drew on the language of writing workshop pedagogy (the directive to write what is important to you) in a parody (to write about doing laundry), opening up a space in which Belle could engage in playful manipulation with what “counted” as writing. This new possible writing identity, co-written by Belle and Louis and pushing back on the “ideal” writer, continued to grow in ways none of us expected across the rest of the group’s time together. In the concluding interview, Belle narrated her new writerly identity as follows:

Belle: So, big picture…I’m your success story!

Amy: Yay!

Valerie: Make her a little picture frame.

Amy: I will. Make you a little award, “Most Improved.”

Belle: I don’t know if I’m really gonna follow through on this, but theoretically I’m gonna have, over a long time, something titled…I have a book called “Laundry Night and Other Overwhelming Life Issues,” because I [recently] wrote another little piece about classroom pets. I’ve had some very bad luck with classroom pets.

Amy: You’ve taken on multiple writing projects at this point, voluntarily.

Belle: I have. I know. It’s weird.

Amy: Why is it weird?

Belle: Because now I’m amused by the whole thing. Going in, basically Luis shamed into being in the group and I had wanted to write this letter…for a long time. It was an excuse to force myself to do it. But it’s like, I’m not a writer, and I’m not really because what I’m doing is I’m sitting down, and it’s almost this sort of stream of consciousness thing. I do it in one sitting. Valerie proofread this one. She made a suggestion. I did change it. But other than that, it’s like I’m not going through the process in the way that I think about or I think is the writing workshop process but it’s on the road possibly.

This exchange showcases Belle’s new self-positioning—as a success story—and her new process—an all-in-one-sitting flow, something she felt she could not get into before. She did make it clear that she was still not living up to her idealized vision of writing, saying “But it’s like I’m not a writer, and I’m not really…going through the process in the way that I think about.” Despite the lingering doubt that she was not following the process she “should,” Belle named her fluency, her revision, and her future plans to continue to work on this voluntary writing process. Though she still rejected the binary “writer” label, her first phrase, “I’m your success story!” and last phrase, “it’s on the road possibly,” displayed a shift in her experience of her own writing identity. While still hesitant to explicitly call herself a writer, Belle’s shifting sense of herself as a writer was evident in her “amusement” with the process, as well as her plans to continue to work on a collection of humorous essays.

Also revealed in this exchange were the ways the writerly relationships developed within the group time were spreading out into the school days when the group did not meet. Belle and Amy discussed her progress with her new project at an unscheduled time, bringing the work of the writing group into her coaching day and Amy’s staff development. Additionally, the new writing project she wanted to share stemmed from her willingness to discuss her writing ideas with a teacher not in the group. Belle also came to Valerie for feedback on her piece outside of the group meeting. These examples indicate that not only was Belle’s sense of her own identity shifting, but her enactment of that identity in interaction with others was shifting as well. This dynamic of co-writing Belle’s (re)written narrative was evident, for example, in the way in which Valerie and Amy responded to her declaration of her position as a “success story.” We teased that we would make Belle a framed award, indicating the irreverence of interactions around Belle’s enactment of her writing identities. This playfulness worked to make visible the ways that writing is ranked and evaluated within school spaces.

Moving across identities

Belle and the other group members drew on their writing experiences to explore their own multiple identities. For Belle, this incorporated the social relationships among members of the group, cross-curricular practices from the writing process to her role as math coach, and how she was situated in other professional learning communities. For instance, responding to Luis in the following excerpt from a group meeting transcript, Belle took up the role of writer and teacher, as well as the role of writing partner - one excited to share in the successes of a fellow writer.

Belle: I think that…and I’m hoping your feelings are the same, but when Valerie sort of changed her mind a million times, and then she had her piece, and I do know Valerie and Luis rather well, like I know what Valerie’s face looks like when she’s happy with something, and you can hear it in her voice, like: “I’m happy!” So the question is, if we, and I don’t think this has to transfer in terms of our thinking to kids, ‘cause I think this group is about us and our own road, but if we do want to think about kids, it’s sort of like, so the three of us are ultimately proud of what we did and that is probably what’s gonna keep us going on this…And so, how do we make [kids feel that pride] and when they do, how do we really capitalize on that? ‘Cause it changes things.

Luis: …it would be wonderful to have like, a group of kids being able to kind of do that same kind of work, reading, sharing, trusting each other, building that trust in their writing process.

Belle here began as a partner. She was attuned to the emotions and body language of the other group members, and identified the “certain pleasure” of pride in a partner’s success. Dialogic/performative analysis highlights the importance of the context and the audience for Belle, as she hoped the group members’ “feelings are the same.” These emotions, the feeling of pride in both what she had accomplished and what her partners had, “change[d] things” for Belle. Moreover, it was this change, this success, even this feeling, that she wanted to bring to students. So, though she positioned herself as a writer, naming that the work of the group was ultimately “about us and our own road,” she was ultimately led through that identity position and into “if we do want to think about kids…how do we make [kids feel that]?” Luis followed up with a specific practice: placing students in small groups for “reading, sharing, trusting each other, building that trust in their writing process,” envisioning what Belle poses along with her.

As this example indicates, and thematic analysis revealed, there were many opportunities for each teacher-writer to connect his or her own process, or the process of the group’s work, to the process their students are asked to go through in the school context. For Belle, whose professional role focused exclusively on math, this often led to cross-curricular connections. For example, in reflecting on her breakthrough with her “Laundry Anxiety” essay in the previous section, Belle began by thinking about herself as a learner, faced with 45-minute blocks to divide her work and how that did not work for her because “brains don’t work that way.” Then, she shifted into considering herself as a writer, narrating her stream-of-consciousness writing process by saying, “I happened to just write it,” indicating that her writing did not come in a predesignated block. As she continued, she moved from her new understanding of herself as a writer to a more common role for her, one as a mathematician. She tied her personal example and amath example back to her shifting understanding as a learner of writing.

School doesn’t work that way. And it’s like, do your on-demand now…here’s our deadline. By this point we’ll be done with our drafts. Now we’re revising. Now we’re editing. Whatever we’re doing. And we’re publishing on this day. And I get that in the real world real writers do have publishing deadlines, but they still do get to work more at their own pace and in their own way than our kids do.

Belle named out the linear steps of the writing process, and considered the messier, freer process of “real writers” (and, implicitly, herself) in comparison to the structured process enforced for students. It was evident here that Belle moved across these different identity positions quickly and automatically, and that the initial experience of reflecting on her own writing process led her to new thoughts and considerations about the learning process and our expectations as teachers.

In moving through her different identity positions with elasticity within this narrative turn, Belle drew on her own experiences as a writer and organically extrapolated implications across curricular areas. She was able to take the perspective of a student, teacher, and “real writer” to reflect on classroom structures, push back upon taken-for-granted norms, and question how learning and teaching might be otherwise. In another group meeting, Belle shifted to yet another identity: that of coach, planning professional learning experiences for the school’s staff.

Belle: Maybe we should commit to getting together next year and maybe for X amount of time it’s around writing, and maybe X amount of time it’s about a book club or reading. And whoever wants to join us can join us. And maybe we can do some fun math. I think that's what I see Professional Monday learning times should be about…it should be connected to what we’re doing, the content and the pedagogy, but it should also be something that we’re getting some enjoyment or pleasure or something out of.

In this excerpt, Belle focused the group on their own professional learning. She brought together both the value of teachers engaging in process and experiences together, working across disciplines, and the emotional impact of the writing group, engaging in professional work they enjoyed and felt proud of. She named these elements together as a new belief about how teacher learning can be positioned: “That’s what I see Professional Monday learning times should be about.”

These examples make evident that engaging in the writing process had implications that were not limited to the writing process itself. We were, simultaneously or at different times, learners, writers, readers, mathematicians, teachers, students, parents, coaches, partners, and friends. The elasticity of these teacher-writers’ positions, as they moved in, across, and through them, allowed them to take up or resist different identities, rewriting their stories while also strengthening collaborative relationships and cross-curricular connections and redefining their professional learning.

Discussion

Through this examination of a focal participant in a teachers’ writing group, we argue that despite the “cover story” of a binary writing identity, teachers’ lived experiences reveal much more complicated and complex writing and teaching identities. These findings contribute to the literature by drawing on a narrative inquiry methodology to center the stories and personal and professional experiences of teachers themselves. Inquiry-based professional learning experiences that invite teachers to bring in their lived experiences and collaborate with one another not only allow them to work together as fellow learners and researchers (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, Citation1999) but also inherently allows them to (re)story themselves as professionals, writers, and teachers of writing. Rewriting identities and crafting new storied selves fosters teacher agency and cultivates meaningful professional learning that can disrupt the isolation of teaching and open up new possibilities for knowledge-of-practice.

These findings have several implications for teaching and teacher education. First, the findings demonstrate the continued need for re-envisioning teachers’ positioning in professional learning, specifically by centering teachers’ identities as the crux of this work that deserves space and attention as a form of embedded, in-school professional learning. This study shows how writing-based professional learning (e.g., National Writing Project) might function effectively as professional learning that not only engages teachers in the work of writing and developing a writing identity but also connects that writing identity to the context in which they are working and the impact they can have in their sphere of influence. Inquiry-based writing served as a tool for Belle to collectively and individually engage in the identity examination work crucial to fostering the ideologically-situated work of responsive teachers (Vetter et al., Citation2014). As illustrated through Belle’s narrative, writing alongside her colleagues led to traversing identity roles, from not recognizing herself as a writer to rewriting her former writing identities to then moving across identities that led to reflection on her professional roles. Thus, Belle’s restorying demonstrates how the inquiry-based writing group contributes to the literature on restorying as not just an opportunity for students’ but for teachers as well.

Fostering choice and agency for teachers to inquire into their practice in ways that are meaningful to them means that, rather than being consumers or recipients of knowledge, teacher-writers have the potential power to become creators of it. Building on Bomer et al. (Citation2019) and Kline et al. (Citation2021), pushing back against narrow conceptions of writing and offering access to social practices and sociopolitical discourses of writing can position teachers as “agents of change and ambassadors for broad conceptions of writing” (Kline et al., Citation2021, p. 97). Belle’s plans for future professional development at the school is one example of how professional learning communities can be linked to social transformation by restoring agency to teachers and reframing expertise as responsive to particular contexts. Establishing shared ownership of professional learning, where teachers have power to shape their work rather than it being assigned to and dictated for them, also creates a space where the hierarchy of school culture can be disrupted (Vinz, Citation1996). This elasticity is fostered by the social connection of individuals as stories are shared and relationships become grounded in multiple identities. No longer able to view one another solely as colleagues, trust and risk-taking can increase once a sense of community and shared purpose is built (John-Steiner, Citation2000; Wenger, Citation1998)—or, as Belle put it, we are made to “care more.”

Moreover, reflexive personal learning experience can reshape teaching and writing identities in important ways, as can be clearly witnessed in Belle’s case. Opportunities for teachers to tap into their lived experiences, as Belle did with her anxiety, allows these experiences into their professional stories in ways they had not been before. A low-stakes environment, one in which approximation and vulnerability are expected and encouraged, and where evaluation and competition are absent, is also essential to professional learning spaces. As teacher-writers learn to take risks and make themselves vulnerable, the way they see their students’ writing can change, as well (Whitney & Friedrich, Citation2013). Through critical reflection (Gorski & Dalton, Citation2020; Liu, Citation2015), they can develop empathy for risk-taking and vulnerability in their classrooms and begin to consider ways they can support their students’ emotional lives as writers. Engaging in writing is the starting point, a process that can transfer into the classroom as we share our writing practices and writing lives with students. If we foster a space that is, as Belle put it, “uncomfortable, but very safe,” growth and change in both writing practices and writing lives might be possible. Inquiry-based collaborative professional learning can give teachers the authority to see their practice and themselves as perpetually changeable. This is particularly evident in Belle’s case; when she was able to merge her personal and professional identities, and a space to process her learning, her understanding and narration of her identity - as a writer and as a learner - underwent significant change. She was able to take on different perspectives, reflect on teaching practices, push back upon taken-for-granted norms, and question how teaching might be otherwise.

Finally, Belle’s example also makes an argument for the invitation to the writing group to be extended to all members of the school community, not only those who explicitly teach writing. In conversation with her writing group colleagues, Belle was able to make cross-disciplinary connections that were powerful for both writing and teaching. By inviting in teachers from other disciplines, or even school staff such as custodians and nurses, not only is the writing and professional learning community for adults expanded, but the opportunity is made available for students to see more writing practices and processes and view more of the adults in their community as writers and learners. The dialogic/performance analytical process, in particular, elucidates the contextual importance of such work happening in schools, as a valued form of identity-centered professional learning. Writing groups provide opportunities for collaborative inquiry, using writing to explore teaching and cultivate reflection. As Belle demonstrated in moving across identities, her writing and sharing helped the group better understand our specific teaching roles, and we talked in ways that gave rise to practices to enact in the future; none of this was limited to arbitrary boundaries of subjects or disciplines. This article provides an invitation for further explorations of narrative inquiry into teachers’ writing and teaching identities in order to better understand the potential of writing groups as transformative professional learning spaces.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Althusser, L. (1971). Lenin and philosophy and other essays. Monthly Review Press.

- Apple, M. (2004). Schooling, markets, and an audit culture. Educational Policy, 18(4), 614–621. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904804266642

- Bomer, R., Land, C. L., Rubin, J. C., & Van Dike, L. M. (2019). Constructs of teaching writing in research about literacy teacher education. Journal of Literacy Research, 51(2), 196–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X19833783

- Butler, D. L., & Schnellert, L. (2012). Collaborative inquiry in teacher professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(8), 1206–1220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.07.009

- Chase, S. E. (2011). Narrative inquiry: Still a field in the making. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (4th ed., pp. 421–434). Sage.

- Chavez, F. R. (2021). The anti-racist writing workshop: How to decolonize the creative classroom. Haymarket Books.

- Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. (1999). Relationship of knowledge and practice: Teacher learning in communities. In A. Iran-Nejad & C. D. Pearson (Eds.), Review of research in education (Vol. 24, pp. 249–306). American Educational Research Association.

- Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. (2009). Inquiry as stance. Teachers College Press.

- College Board—The National Commission on Writing in America’s Schools. (2003). The neglected “R”: The need for a writing revolution. College Entrance Examination Board.

- Connelly, F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (1990). Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educational Researcher, 19(5), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X019005002

- Costa, A. L., & Kallick, B. (1993). Through the lens of a critical friend. Educational Leadership, 51(2), 49–51.

- Cremin, T., & Baker, S. (2014). Exploring the discursively constructed identities of a teacher-writer teaching writing. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 13(3), 30–55.

- Dawson, C. M. (2017). The teacher-writer: Creating writing groups for professional and personal growth. Teachers College Press.

- Dyson, L. (2020). Walking on a tightrope: Agency and accountability in practitioner inquiry in New Zealand secondary schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 93, 103075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103075

- Gee, J. P. (1989). What is literacy? Journal of Education, 71(1), 18–25.

- Gorski, P. C., & Dalton, K. (2020). Striving for critical reflection in multicultural and social justice teacher education: Introducing a typology of reflection approaches. Journal of Teacher Education, 71(3), 357–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487119883545

- Hall, S. (1996). Who needs “identity”? In S. Hall & P. D. Gay (Eds.), Questions of cultural identity (pp. 1–17). Sage.

- Holland, D., & Leander, K. (2004). Ethnographic studies of positioning and subjectivity: An introduction. Ethos, 32(2), 127–139. https://doi.org/10.1525/eth.2004.32.2.127

- Ivanič, R. (2004). Discourses of writing and learning to write. Language and Education, 18(3), 220–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500780408666877

- John-Steiner, V. (2000). Creative collaboration. Oxford University Press.

- Juuti, K., Lavonen, J., Salonen, V., Salmela-Aro, K., Schneider, B., & Krajcik, J. (2021). A teacher–researcher partnership for professional learning: Co-designing project-based learning units to increase student engagement in science classes. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 32(6), 625–641. https://doi.org/10.1080/1046560X.2021.1872207

- Khachatryan, E., & Parkerson, E. (2020). Moving teachers to the center of school improvement. Phi Delta Kappan, 101(6), 29–34. https://kappanonline.org/moving-teachers-center-school-improvement-khachatryan-parkerson/ https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721720909588

- Kline, S. M., Kang, G., Ikpeze, C. H., Smetana, L., Myers, J., Raskauskas, J., Scales, R., Tracy, K. N., & Wall, A. (2021). A multi-state study of dominant discourses in teacher candidates’ memories of writing. Teacher Education Quarterly, 48(1), 79–99.

- Lagemann, E. C. (2000). An elusive science: The troubling history of education research. The University of Chicago Press.

- Lensmire, T. J. (2000). Powerful writing: Responsible teaching. Teachers College Press.

- Lensmire, A., & Schick, A. (2017). (Re)narrating teacher identity: Telling truths and becoming teachers. Peter Lang.

- Liu, K. (2015). Critical reflection as a framework for transformative learning in teacher education. Educational Review, 67(2), 135–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2013.839546

- Love, B. L. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press.

- Luttrell, W. (1997). Schoolsmart and motherwise: Working-class women’s identity and schooling. Routledge.

- Moje, E. B., & Luke, A. (2009). Literacy and identity: Examining the metaphors in history and contemporary research. Reading Research Quarterly, 44(4), 415–437. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.44.4.7

- New York Collective of Radical Educators. (n.d). Mission. http://www.nycore.org/nycore-info/mission/

- Norman, K. A., & Spencer, B. H. (2005). Our lives as writers: Examining preservice teachers’ experiences and beliefs about the nature of writing and writing instruction. Teacher Education Quarterly, 32(1), 25–40.

- Picower, B. (2021). Reading, writing, and racism: Disrupting whiteness in teacher education and in the classroom. Beacon Press.

- Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage.

- Rogers, R., Kramer, M. A., Mosley, M., Fuller, C., Light, R., Nehart, M., Jones, R., Beaman-Jones, S., DePasquale, J., Hobson, S., & Thomas, P. (2005). Professional development as social transformation: The literacy for social justice teacher research group. Language Arts, 82(5), 347–358.

- Smith, S., & Watson, J. (2010). Reading autobiography: A guide for interpreting life narratives. University of Minnesota Press.

- Spradley, J. P. (1979). The ethnographic interview. Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

- Taubman, P. M. (2010). Teaching by numbers: Deconstructing the discourse of standards and accountability in education. Routledge.

- Teacher Action Group – Philadelphia. (n.d). About: Who we are, what we believe. http://tagphilly.org/about/

- Thomas, E. E., & Stornaiuolo, A. (2016). Restorying the self: Bending toward textual justice. Harvard Educational Review, 86(3), 313–338. https://doi.org/10.17763/1943-5045-86.3.313

- Timperley, H., & Alton-Lee, A. (2008). Reframing teacher professional learning: An alternative policy approach to strengthening valued outcomes for diverse learners. Review of Research in Education, 32(1), 328–369. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X07308968

- Vetter, A., Myers, J., & Hester, M. (2014). Negotiating ideologies about teaching writing in a high school English classroom. The Teacher Educator, 49(1), 10–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730.2013.848000

- Vinz, R. (1996). Composing a teaching life. Heinemann.

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

- Whitney, A. E., & Friedrich, L. (2013). Orientations for the teaching of writing: A legacy of the National Writing Project. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 115(7), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811311500707