In 1901, Rubén Darío commented on the lack of knowledge, in Paris, of Latin American letters: “Unfortunately, it is all a question of fashion.”Footnote1 Darío’s renovation of Latin American literature created a tension between artistic autonomy and the desires of the masses mediated through newspapers and magazines. This tension gave life to Modernismo, the first cohesive literary movement to form in Latin America. Modernistas wrote poetry, fiction, and non-fiction prose whose core values concerned aesthetic matters and poetic innovation. The writers gained a strong presence in the public sphere through political appointments and relationships with the cultural and political elite. Out of this friction came Darío’s collections of prose and poetry, titles now familiar to anyone with exposure to Latin American letters: Azul . . . , Prosas profanas, Los raros, Cantos de vida y esperanza. What Latin American schoolchild cannot recall from memory the iconic lines: “La princesa está triste . . ., ¿qué tendrá la princesa?” [The princess is sad . . . , What’s wrong with the princess?]Footnote2 These lines, almost universally known in the Spanish-speaking world, represent Darío’s poetic innovation with its medieval alejandrino verses and dactyl meter. Assessing his poetry towards the end of his life, Darío proclaimed that “Sonatina is the most rhythmic and musical of all of these compositions, and the poem deemed to be most fashionable in Spain and America.”Footnote3 The poet celebrated “Sonatina” as highly fashionable, with its popular song-like construction, its striking appeal to the senses, and its manifestation of exoticism and young romantic longing. This unique invention of a poetic fashion would preserve the legacy of Darío and Modernismo to the present day.

This special Review issue on Darío and the Modernista movement comes on the heels of the centennial commemoration of the poet’s death in 1916. The Nicaraguan ushered in a century of original and revolutionary poetics and public intellectualism, the intersection of politics and prose, a cosmopolitanism firmly grounded in a Latin American consciousness, and enduring regional literary expression. This dossier highlights, celebrates, and complicates the enduring legacies left behind by Darío. In considering the context of Modernismo and the mission of Review to disseminate Latin American literature in the English language, I thought it necessary to include a selection of women Modernista writers who challenged the norms of the literary field during Modernismo and made fundamental contributions to literary expression. The lines of Alfonsina Storni, in her poem “A Few Words for Rubén Darío,” contain this powerful assertion: “Fresh forms attract me, colors on parade . . . / I love fierce styles, fangs she-wolves bare with glee.”Footnote4 The ravenous celebration of new forms, new colors, new ways of seeing, define a Modernismo that left the door only partially open for women’s expression. These voices need to be further represented in English translations like those that appear in this issue.

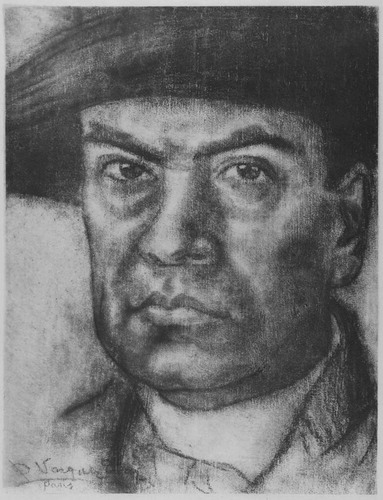

From an early age, Darío avidly read classic and contemporary literature and wrote poetry. He published his first lines of verse at the age of twelve and by thirteen he was collaborating with the literary magazine El ensayo in León. At seventeen, he obtained employment in the National Library of Managua and as the private secretary of Nicaraguan president Adán Cárdenas. At nineteen, he began a life of travel, returning to his home country only for short stays. He spent his adult years between Chile, Argentina, Spain, France, and the U.S., with stops across Latin American and Europe along the way. Sick and nearly destitute, he returned home to León, Nicaragua to die at the age of 49.

Darío’s poetic influence has been universally celebrated following his death in 1916. Canonical Latin American writers Jorge Luis Borges, Gabriela Mistral, Gabriel García Márquez, Pablo Neruda, Marío Vargas Llosa, and Elena Poniatowska have all documented the lasting impact of Darío’s poetic revolution. Borges called him “the Liberator” for opening the continent to literary renovation that “will not cease.”Footnote5 The inclusion of Borges’s essay celebrating the poet, along with the famous 1933 speech at the banquet of the Buenos Aires PEN Club by Pablo Neruda and Federico García Lorca, both documents translated for the first time into English, highlight Darío’s lasting prestige among essential literary circles in Latin America and across the Atlantic.

Darío’s relationship with the U.S. is complex and nuanced, as outlined in the multiple textual examples in José Eduardo Arrellano’s essay. An additional objective of this special issue is to represent Darío’s relationship with the U.S. Darío visited New York for the first time in 1893, returned in 1907 and again in 1914 for what the New York Times labeled as “a lecture tour in the interests of international peace.”Footnote6 The two Darío essays included here, “Por el lado del Norte,” published in 1892, and “El cetro de chiffon,” in 1907, show an acute awareness of the military, governmental, and cultural domination of the U.S. towards its southern neighbors. Despite few instances of an attitude of diplomacy and fraternity regarding the U.S., the poet regularly exhibits an impassioned contempt for American abuses of power and its attitude of superiority over Latin America.

Scholarship on Darío has been fruitful in understanding the poet, the material and cultural contexts of his life and literature, and the literary reverberations still felt by his poetry and prose. The four scholarly studies featured in this issue indicate that current Darío studies are more nuanced, thoughtful, and innovative than ever before. In the first essay, Gwen Kirkpatrick echoes Mexican poet José Emilio Pacheco’s call to “forgive Darío.” For Kirkpatrick, Darío incorporates a profusion of forms to create a fragmented and “reckless” heritage. Nevertheless, despite the poet’s precarious style and humiliation abroad as a mestizo, Darío’s work and influence is repeatedly taken up by writers throughout the twentieth century. The wandering, mestizo, cosmopolitan poet’s legacy continues today with authors such as Sergio Ramírez and Álvaro Enrigue. Adela Pineda Franco turns to the challenge of Darío in his later years to situate Latin American art as a response to the adverse social climates of Western society in the first decades of the twentieth century. Darío addresses Western deterioration through journalistic chronicles that, often between the lines, strongly critique and confront the “naked violence of [European] colonialism.” For this reason, the poet resists the aesthetic trends of Europe at that time, what Pineda Franco calls the “cultural exhaustion of European modernity,” to retrench his literary perspective in a high, aristocratic perspective as continually outlined in publications such as his Parisian periodical, Mundial Magazine.

The incorporation of digital tools in literary analysis has quickly advanced the burgeoning field of Digital Humanities in scholarly circles around the world. José González is one of the first to bring this new set of interpretive mechanisms to Modernismo and Darío scholarship. His study, co-authored with Monserrat Fuente-Camacho and Marcus Barbosa, runs a group of Modernista novels through vocabulary-sorting software to seek out, confirm, and complicate distinctive features that have typically defined the Modernista literary canon. These digital tools allow the study’s authors to analyze features of large groups of texts, in this case 76 novels, and then illustrate how writers across gender, throughout the decades of the movement, exhibit Modernista textual markers. New digital approaches such as these construct innovative perspectives on literary production and help to question the cohesiveness of Modernismo as a transnational literary movement that spanned over four decades. To conclude the scholarly section, Julia Medina gives a close reading of the poet’s last texts through the theoretical lenses of Foucault’s biopolitics and the conflicting ecological references in Darío’s final works. The poet, conscientious of his waning life, suggests a nomadic Americanism that Medina aptly calls a distortive “organic archive” which, as applied to Darío’s bibliography, occurs across registers and eschews permanence and national identity. In his final year, Darío described, in fiction and chronicle form, the biopolitical forces that resisted Western thought and situated the poet firmly within a nomadic identity. These essays celebrate Modernista scholarship and critically represent uncovered impacts of the poet and his movement, societal critiques that have yet to be explored, and new directions of digital scholarship.

The creative section of this special issue highlights contemporary literature from Central America, Europe and the U.S. It begins with Sergio Ramírez, who takes us through Darío’s childhood armoire where the poet discovered works such as El Quijote, One Thousand and One Nights, and the Bible. Ramírez positions these books as foundational and repeated references throughout Darío’s textual production. Darío scholar Günther Schmigalle’s memorial to the poet traces a career of discovering the multitude of voices in Darío’s prose and the decades-long project devoted to editing his crónicas.

Following Ramírez and Schmigalle, the issue includes a selection of poems spanning Darío’s literary career in addition to four poetic selections from a range of contemporary women writers influenced by the legacy of Modernismo and Darío. Iliana Rocha, a prominent Latinx poet and author of the award-winning book Karankawa, contributes two original poems that play on the themes and forms of Modernistas Alfonsina Storni and Delmira Agustini. Milagros Terán, winner of Nicaragua’s National Poetry Prize, follows with five short poems that invoke a desire steeped in a Modernista poetic tradition of sensual imagery and longing. The poetry of Guatemalan Ana María Rodas represents Darío’s poetic and literary heritage. Rodas invokes classical themes and intersects them with eroticism and a renewed, modern poetics, similar to Darío’s repeated use of classical figures and symbolism. In this case, Rodas provides a powerful woman’s poetic voice to assure that “some other poet will come along / to recall this love of ours,”Footnote7 who could be someone like Darío or even Rodas herself. The selection of poetry ends with Lucy Cristina Chau, an award-winning Panamanian writer whose three poems introduce themes of poetic subjectivity, youthful nostalgia, and social justice. Finally, a story by Nicaraguan author Erick Blandón creates a world of intertextuality that cinematographically intertwines Tennessee Williams, Edgar Allan Poe, and Gabriel García Márquez with the Modernista poet. This creative section reveals how Modernismo continues to impact vibrant contemporary writers in the U.S. and Central America.

This special issue would not be possible without the patience and guidance of Daniel Shapiro. His support and unwavering editorial abilities make Review the extraordinary and essential publication that it is. Special thanks to the writers and scholars and their dedication to the enduring voices of Modernismo and Rubén Darío.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andrew Reynolds

Andrew Reynolds is Associate Professor of Spanish at West Texas A&M, author of The Spanish American Crónica Modernista, Temporality & Material Culture (2012), and co-editor of Behind the Masks of Modernism: Global and Transnational Perspectives (2016). He has lately co-edited a book with Heather Allen, Latin American Textualities (2018).

Notes

1 Rubén Darío, “Las letras hispanoamericanas en París,”¿Va a arder Paris . . .Crónicas cosmopolitas, 1892-1912, edited by Günther Schmigalle (Madrid: Veintisiente Letras, 2008), 97. All translations in this introduction are my own, except where quoted from works appearing in this issue.

2 Rubén Darío, “Sonatina,” Prosas profanas, 9th Ed. (Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1979), 25. Perhaps the most memorized line in all Latin American letters. It is also a line used by writers throughout Latin American literary history, including contributor Sergio Ramírez in his novels Margarita, está linda la mar and Sombras nada más.

3 Rubén Darío, La vida de Rubén Darío escrito por él mismo (Caracas: Biblioteca Ayacucho, 1991), 145.

4 Alfonsina Storni, “Palabras a Rubén Darío,” Antología poética (Buenos Aires: Editorial Losada, 1971), 116.

5 Jorge Luis Borges, “Mensaje en honor de Rubén Darío,” in Estudios sobre Rubén Darío, edited by Ernesto Mejía Sánchez (México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1968), 13.

6 “Noted South American Poet Writes about New York,” New York Times, Nov. 29, 1914.

7 Mentioned in Rodas’s poem “Vivamos Valeria.”