ABSTRACT

Leadership training commonly brings individuals or teams together in face-to-face settings to network and build their skills in groups referred to as “cohorts.” The pandemic of 2020 forced leadership training programs to be held virtually, bringing into question how programs could foster a sense of “cohortness,” or a collegial sense of group identity, even when the participants could not meet face-to-face. For this study, two programs, the Clinical Scholars (CS) program (n = 34), and the Food Systems Leadership Institute (FSLI) (n = 23), collaborated to explore how participants expecting an in-person program responded to adaptations made for a virtual launch of their program and how connected they felt to their fellow classmates. Analysis of qualitative and quantitative data showed that prior to attending each program, fewer than half of participants expected to feel slightly to very connected as a cohort. At program completion, 96% reported feeling slightly to very connected. Both CS and FSLI participants ranked 1) Frequent small group exercises, 2) small group ice breakers, 3) Team introductions prior to the retreat 4) Virtual orientation as the top activities contributing to their sense of being a cohort. Although the pandemic will pass, the insights gained from examining how to foster professional networks and a collegial sense of group identity (“cohortness”) among virtually convened participants can benefit leadership development programs that must continue to meet virtually for financial or other reasons and can benefit those programs, which eventually resume in-person convenings.

Introduction

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic-forced face-to-face learning environments to pivot to distance-based learning platforms across the educational spectrum. This change affected K-12 (Kuhfeld, et al., Citation2020) and higher education (Liberman-Martin & Ogba, Citation2022), post-graduate education activities, and workforce development approaches, such as conferences and advanced learning institutes (Fingar, Citation2021). Two such programs, Clinical Scholars (CS) (www.ClinicalScholarsNLI.org), and the Food Systems Leadership Institute (FSLI) (www.FSLI.org), had to transform instruction from in-person convened intensive sessions to a variety of virtual-learning synchronous and asynchronous formats. The transformation of the experience illuminates two different concerns: efficacious learning and group bonding. We have demonstrated that engagement in learning and skill-building in the CS program can expand during this pivot (Fernandez et al., Citation2021a). Our findings are consistent with other results in the literature for medical education (Blake, Bermingham, Johnson, & Tabner, Citation2020; Gordon et al., Citation2020). However, staff in the CS and FSLI programs remained significantly concerned about how training programs can catalyze connectivity within a new incoming group of participants to create intra-cohort “bonding” when conducting intensive programs virtually, which we refer to as the concept of “cohortness.” For this paper, we define the term “cohortness” as the collegial sense of belonging to a defined group within the program, a sense of being connected to others in one’s incoming class, and a sense of identifying as a “Program Fellow.” Participants enrolled in CS and FSLI are referred to as “Fellows” by their respective programs and funders.

Interpersonal networking, bonding, and developing collegial relationships are an essential aspect of professional development programs, such as leadership development institutes (Cleary et al., Citation2020; Levine, Gonzalez-Fernandez, Bodurtha, Skarupski, & Fivush, Citation2015; Nowling et al., Citation2018; Sonnino, Citation2013) and represent a common focus of such programs (Geerts, Goodall, & Agius, Citation2019; Sonnino, Citation2013). As the pandemic initially caused us to cancel our planned onsite programs, current CS and FSLI program Fellows expressed appreciation for the previous in-person intensives. Expressly, that they missed those interpersonal connections when both programs had to transition face-to-face convenings into virtual sessions and gatherings (Fernandez et al., Citation2021a; personal communications). Collectively, we felt the echo in our participants of the loneliness and isolation during the pandemic reported by researchers, such as Smith & Lim (Smith & Lim, Citation2020), and that perception intensified both programs’ desire to experiment and learn how to foster “cohortness” through activities connecting individual participants and the program. Particularly for the newly accepted cohorts of participants who had not yet met or established strong bonds with one another, we hoped that efforts to facilitate connections through these virtually deployed professional development programs could support individual growth and learning and possibly help address other such interpersonal concerns. By way of example, in FSLI some participants deferred 2020 enrollment because of their concerns for learning and networking virtually (personal communications).

While the two programs highlighted in this manuscript serve different audiences working to achieve other goals, both programs share many of the same core competencies, learning structure, learning elements, leadership development theories, administrative support, and teaching faculty. CS and FSLI enrolled their first all-virtual new cohort in 2020 (Cohorts 5 and 16, respectively). How the programs might foster the kind of interpersonal connections that would replicate the bonding that previously took place in the onsite experience became a focus of study.

As the pandemic continued into the fall of 2020, the leadership teams of both programs collaborated to investigate how the distance-based strategies for leadership development fostered “cohortness” among the new cohorts, the vast majority of whom would not have the opportunity to meet in person for the foreseeable future. Even in CS, while most applying teams are geographically co-located, team members historically have varied widely in the degree of in-person interaction before selection. Indeed, many teams had no prior collaboration history. This paper reports on the programmatic methods used by CS and FSLI and evaluation data collected regarding both programs’ participants’ perceptions of connectedness with other participants and with the program, in order to gain insight into the concept of fostering “cohortness” in virtually convened environments.

Methods

Setting

The FSLI program is a two-year leadership development program for senior academic administrators, industry leaders, and government officials, enrolling up to 25 Fellows per cohort and has been described in depth elsewhere (Fernandez, Noble, Jensen, Martin, & Stewart, Citation2016a). The program received seed-funding from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. Fellows complete an individual leadership development project relevant to their organization or their profession and traditionally engage in three in-person retreats during the first year of their experience. The CS program enrolls up to 35 individual “Fellows” participating in interdisciplinary teams of three-to-five health-care professionals in a three-year leadership development program founded on principles of equity, diversity, and inclusion. The structure, evaluation, and outcomes of CS have been described in depth elsewhere (Fernandez et al., Citation2021b). Funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, program Fellows complete a team-based leadership development project focusing on a “wicked problem” (Camillus, Citation2008; Rittel & Webber, Citation1973) to advance health equity in their communities. presents the comparison of program structure between FSLI and CS. Prior to the pandemic and the forced pivot to virtual intensive convening, FSLI Fellows reported a strong sense of intra-cohort bonding, and CS Fellows reported a strong sense of both intra- and inter-cohort bonding, network development, and collegial relationships (Dave, Noble, Chandler, Corbie-Smith, & Fernandez, Citation2021, and internal communications, program evaluation data). In the fall of 2020, the FSLI and the CS programs each presented a four-day virtual experience (24 and 23.25 contact hours, respectively). Given the multiple-time zones for program Fellows, both programs offered sessions from 11:00 AM or 12:00 PM through 5:30–6:30 PM eastern time. The programs are identical in structure in that they provide an array of valid and reliable psychological assessment tools typically included in leadership development programs and an array of sessions led by recognized subject matter experts. Both programs were administered virtually via the Zoom platform and incorporated easily accessible web-based collaborative space to support interactive learning; specifically, we used Google docs and Miro boards, an online virtual interactive whiteboard/flipchart.

Table 1. Comparison of Structural elements of CS and FSLI programs.

Participants

Of the 34 Fellows enrolled in the CS program and completing the virtual retreat, seven reported as men and 27 as women with an average age of 45.45 years (range 35–66 years). Fellows reported race included Asian: 6; Black: 6: White: 20; Bi-racial/Multi-racial: 1; Missing: 1; Hispanic ethnicity: 3. These participants represent organizations in seven states. Of the 23 Fellows enrolled in the FSLI program and completing the virtual retreat, 14 reported as women and nine as men, with an average age of 51.1 years (range: 33–70 years), one individual declined to provide their age. Fellows’ reported race included Black: 6; White: 16; Arabic: 1. One individual identified as Hispanic. These participants represent organizations in 16 states.

FSLI and CS program staff separately brainstormed ways to promote connectivity and bonding and shared those ideas across the two programs. Each program adopted strategies that best suited the program format and goals. Approaches made to foster the sense of “cohortness” fell into four areas, as noted in .

Table 2. Methods to foster cohortness among virtually convened members of CS Cohort 5 and FSLI Cohort 16.

Data collection and main indicators

The research team coordinated evaluation approaches by collecting data within programs and aggregating across programs. Using Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Citation2020), both quantitative and qualitative data were collected online during dedicated time at the end of the final day of the program (CS), with links also sent via a follow-up e-mail reminding participants of the request for completion (both programs).

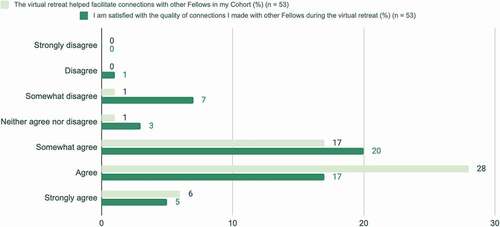

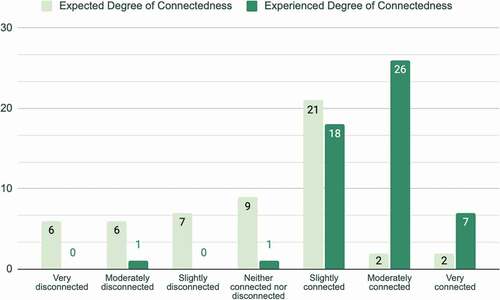

Using a retrospective pre and posttest format (Fernandez, Noble, Jensen, & Steffen, Citation2014; Lam & Bengo, Citation2003; Pratt, Mcguigan, & Katzev, Citation2000; Sprangers & Hoogstraten, Citation1989), the research team asked participants to provide two ratings: 1) a retrospective rating of their pre-program feelings of how connected to others they expected to feel after attending the retreat, and 2) a post-program rating of how connected they felt to others in their program after attending the virtual retreat. For both items, participants used a 7-point Likert scale: 1 = Very disconnected, 2 = Moderately disconnected, 3 = Slightly disconnected, 4 = Neither connected nor disconnected, 5 = Slightly connected, 6 = Moderately connected, 7 = Very connected. Participants also rated how well the virtual retreat helped facilitate connections with other Fellows in the cohort and their degree of satisfaction with the quality of the connections made. These questions used a 7-point Likert scale to evaluate the level of agreement with the two statements: 1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Somewhat disagree, 4 = Neither agree nor disagree, 5 = Somewhat agree, 6 = Agree, 7 = Strongly agree.

Both programs explicitly offered targeted connection activities () with specific post-program ranking for eight such activities in CS and six in FSLI with participants ranking the most useful first and the least useful last (See ). The survey asked participants to indicate how they planned to connect with other cohort members, by asking them to choose among six options, including an open-ended “other” option. Participants were instructed to select all options that applied.

Table 3. Factors that affected connection building in the virtual environment.

Finally, participants were asked to respond to two open-ended questions: 1) “What factors do you think affect building connections (positively or negatively) in a virtual environment?” and 2) “Do you have any recommendations or feedback for ways to improve connection and bonding within the cohort during future virtual retreats?” Consent was obtained from all participants prior to the collection and analysis of these data and all UNC-IRB ethical guidelines were followed.

Data analysis

The research team exported data from Qualtrics to an MS Excel database. Descriptive statistics were analyzed for the survey responses. Numerical values assigned to Likert scale responses were used to calculate means and standard deviation. Qualitative survey data were also analyzed to identify emergent themes across both groups of participants and the frequency of each theme. Each statement was coded independently.

Results

Participant responses

Many participants gave multiple responses to each open-ended question; the 49 participants (29 from CS and 20 from FSLI) who responded to the first question gave 63 unique statements, and the 36 participants (20 from CS and 16 from FSLI) who responded to the second question provided 40 unique statements.

Overall perceptions of connectedness for virtually convened retreat

Clinical Scholars and FSLI participants rated their expectations for making meaningful connections as low, with 52% rating between very disconnected to neutral and 40% rating their expectation as “slightly connected.” Only a small minority (8%) anticipated that they would feel moderate to very connected by the end of their retreat experience (). At the end of the program 83% rated their actual feeling of connectedness as “slightly” to “moderately” connected, and 13% rated it as “very connected” (). The mean rating on the 7-point scale was 3.89 (SD = 1.59) for expected degree of connectedness and 5.68 (SD = .87) for experienced degree of connectedness (mean difference = 1.79).

Figure 1. Expected vs Experienced Connectedness among FSLI and CS participants post-retreat (n = 53).

shows the level of agreement among retreat participants with statements evaluating how well the virtual retreat facilitated connections and how satisfied participants were with the quality of connections they formed. A total of 64% agreed or strongly agreed that the virtual retreat helped facilitate connections with other Fellows in their cohort, with 32% somewhat agreeing. Concerning satisfaction with the quality of the connections made, 41% reported agreeing or strongly agreeing with being satisfied, while 38% “somewhat agreed” and 13% “somewhat disagreed” with the statement.

CS (n = 32) and FSLI (n = 20) participants ranked activities similarly in order of effectiveness, with both programs giving the highest average rankings to 1) frequent small group exercises, 2) small group icebreakers, 3) introduction activities prior to the retreat, and 4) a virtual orientation session. The box of retreat materials, including branded items and incentives, sent in advance of the retreat received the lowest ranking in both programs.

Participant plans for post-program follow up

Fifty-one participants indicated how they planned to connect with other cohort members after the retreat (). Post-program intentions to follow up with other Cohort members included sharing contacts (reported by over half of all participants) and gathering information together (reported by one-third of all participants). These data were quite similar across the two programs. Another third of participants said they had no plans at the end of the virtual retreat. Other participants were planning on engaging in peer coaching relationships (20%), partnering on new projects (14%), engaging in a mentoring relationship (14%), or other strategies (8%). Slightly more CS participants indicated the intent to stay connected following the retreat, with 68% of CS participants and 60% of FSLI participants sharing one way they planned to connect.

Table 4. Ways Fellows intend to stay connected with each other after attending the virtual retreat.

Open-ended feedback

Forty-nine participants (29 from CS and 20 from FSLI)) responded to “What factors do you think affect building connections (positively or negatively) in a virtual environment?” and 36 (20 from CS and 16 from FSLI) responded to “Do you have any recommendations or feedback for ways to improve connection and bonding within the cohort during future virtual retreats?” Multiple answers were each coded as separate data points.

Open-ended feedback on what factors either negatively or positively affect building connections in a virtual environment showed that even with issues that are inherent to virtual environments (difficulty reading nonverbal cues, having to navigate technical barriers), many participants could identify components of the retreat that successfully facilitated connections (). The most commonly cited factor to positively impact connections was the small virtual breakout groups, where participants could have more intimate conversations and share information about their projects or other issues. Factors that negatively affected Fellows’ ability to build connections included the lack of opportunity for informal conversations and bonding (such as during meals or breaks between sessions), trouble using the virtual platforms, and insufficient social time within the sessions, including for introductions and within small groups.

Table 5. Recommendations and feedback to improve connections during future virtual retreats.

Many participants who offered feedback on ways to improve future retreats recommended more time in small groups – both casual, unstructured time to socialize and time with standardized groups to synthesize content (). Several participants noted that they would welcome a longer retreat overall if it meant more time to interact with other Fellows. Compared to CS Fellows, FSLI participants offered more specific suggestions on how to maximize small group time, such as assigning different group configurations on different days but keeping participants in consistent groups within each day, more concentration on mixing small groups so participants have a chance to socialize with everyone, and creating opportunities for Fellows to connect one-on-one.

Discussion

Our experience with these two programs launching new cohorts of incoming leadership program Fellows indicates that creating cohort connectedness in virtual spaces can be accomplished using strategies designed to personalize distance-based training. We found that small group exercises tied to instruction time and informal time for participants to meet are critical to building that in-cohort connection, much as Kumar and Heathcock noted in their extensive review of creating supportive online learning environments (Kumar & Heathcock, Citation2014). However, unlike with in-person environments, these connections do not happen naturally and must be intentionally planned into the structure of the interactions and accounted for in the instructional time (Kumar & Heathcock, Citation2014; Roddy et al., Citation2017).

Leadership development activities often include structured interactions, such as peer coaching (Frich, Brewster, Cherlin, & Bradley, Citation2015), networking, and peer-to-peer mentoring. While these activities can be highly impactful, they function best when built on a groundwork of trust (Vidmar, Citation2006), and participants can build trust more quickly when they can meet, get to know one another, and learn together (Campbell, McBride, Etcher, & Deming, Citation2017). For example, as a strategy to foster trust, we asked that cameras stay on during all sessions.

We have previously shown that pivoting a leadership curriculum to virtual delivery can maintain learner engagement as well as knowledge and skill acquisition but that the pivot sacrifices the breadth of learning through a combination of limited contact hours and a stronger and more narrow focus on fewer topics/learning objectives (Fernandez et al., Citation2021a). From this data, we conclude that many of the strategies used to focus the curriculum (frequent breakouts, small group virtual work, teach-then-apply strategies) in addition to open-format informal connection time help foster this sense of connection.

All too often, training and development activities are considered expendable during times of financial crisis or disruption of regular routines. However, as the pandemic of 2020–2021 illustrated, the need for enhanced skill sets, for sharing knowledge, and for tapping into supportive networks of colleagues does not diminish during crises – if anything, it becomes of paramount importance (Heath, Sommerfield, & von Ungern-sternberg, Citation2020; Krystal et al., Citation2021). Given the common reports of increased rates of loneliness and isolation in 2020 (Smith & Lim, Citation2020), efforts to connect the workforce through virtual professional development could help to prevent or ameliorate other such personal concerns while they simultaneously support individual and collective growth and learning.

Given the wide acknowledgment of the important role professional networks play (Cullen-Lester, Woehler, & Willburn, Citation2016) particularly in leadership roles (Baltodano, Carlson, Jackson, & Mitchell, Citation2012) it is crucial that when leader and workforce development programs are offered virtually, they must still place careful consideration on how to achieve the aim of developing and strengthening such connections. Prior to the pandemic, Kumar and Heathcock (Kumar & Heathcock, Citation2014) identified a sense of belongingness or community as a critical pillar supporting student success in virtual environments. Even for programs in which virtual training is the plan and not the pivot, the development of professional networks poses a serious concern. When programs originally structured as face-to-face convenings need to pivot to virtual administration due to external crises – such as the pandemic – the chaos, fear, and even simple break from the routines of everyday life underscores the importance of fostering professional networks during the training experience.

Creating a sense of bonding and connectedness, resulting in the collegial sense of belonging to the group, an idea we refer to as “cohortness” is challenging but possible to achieve even in a virtual environment (Kumar & Heathcock, Citation2014), and even when participants enrolled are anticipating an in-person experience. illustrates that most participants did not hold high hopes for their collegial experience in the programs, expecting that they would feel slightly connected or very disconnected to their fellow Cohort members. However, given the intentional focus on the development of “cohortness,” we found that the majority of the participants reported their experience greatly exceeded initial expectations by the end of the virtual retreat. However, it is of note that one-third of participants expressed no plans to follow-up with colleagues post-program, which suggests that structured opportunities might facilitate ongoing peer-to-peer connections for those who do not seem inclined to pursue them independently. We recognize that time devoted to building connections still counts as program time, and that time is a valuable commodity for these busy professionals who in CS represent health-care providers, many first responders during the pandemic, and who in FSLI represent mid and upper-level administrators in higher education. Both groups routinely share that time pressures are significant issues.

One challenge the teams running both FSLI and CS gave serious consideration to was the important trade-off between instruction time and participant bonding time. Particularly when programs are virtually deployed, we have experienced a trade-off for time in developing “cohortness” because the minutes committed to interpersonal interactions take away from time for traditional instruction, knowledge sharing, practice application, and refinement as with Q&A sessions with subject matter experts. We found that it is possible to weave the concepts together, with small-group focused activities applying the learning, however we recognize that “task completion oriented” skill-practice and case studies by their nature still impede the more casual networking and getting-to-know-one-another activities that almost naturally take place during in-person convened meetings. The feedback suggestion from participants that dedicated small groups, which continue to stay together and work together across a day of program activities or longer, are more effective than strategies to ensure that everyone in a new cohort meet one another, was interesting and not tested out in this investigation. Additionally, unstructured open-opportunity social time was offered in these programs as “Virtual Hang Outs” for the FSLI Fellows and “Virtual Fireside Chats” for the CS Fellows at the end of each day’s more formal sessions. Participation in these sessions was lighter, with Fellows informally reporting fatigue after several hours of virtual learning, a symptom, which has been subsequently supported in the literature (Bailenson, Citation2021; Ramachandran, Citation2021). In future convenings, we planned to offer these unstructured, informal sessions prior to the day’s programming and found similarly limited participation. We suggest that unstructured time be included within the regular programming schedule in order to more fully support networking and other connections.

In both the CS and FSLI programs, program faculty and administrators focused diligent effort to the “minute-by-minute” experience of the newly incoming learners, so that each facet of their learning and interaction was balanced and intentional. Program teams examined the minutes to be spent in learning and engaged activities, those in knowledge acquisition (i.e. lecture formats), interpersonal time, and personal time (breaks). Our team decided upon the specific strategies employed primarily through brainstorming and collaboration, given that our instructional faculty have decades of experience in the field. One aspect of the CS program evaluation is exploring is the development of networks within cohorts. Over time, we will be able to see if this cohort that started virtually has a different experience of network building than the cohorts who started in-person. We recommend that both network building and an investigation of various impacts of small group instruction in virtual settings provide opportunities for further research.

Limitations

While we gathered data related to perceptions of “collegial connectedness,” we did not a priori define “cohortness” to the participants. Rather, we considered “collegial connectedness” a proxy for creating the sense of community that helps identify an individual with the program and with their fellow participants. As with any self-report data, social desirability bias may have been a contributing factor, in that participants may have wanted to please the program staff or may have even been influenced by being asked the question about program connections and connectedness (Furnham, Citation1986). Such bias is an inherent concern in all studies that use self-report methods (Fernandez, Noble, Jensen, & Chapin, Citation2016b). However, use of retrospective pre- and posttest format, which was used here to measure degree of connectedness before and after the retreats, can lower the risk of social desirability bias provide a more accurate measure of change (Fernandez et al., Citation2016a; Lam & Bengo, Citation2003; Pratt et al., Citation2000; Rohs, Citation1999; Sprangers & Hoogstraten, Citation1989). As a final important point, participants were not asked about loneliness or feelings of isolation, thus no conclusions can be drawn as to how virtual programs or any specific strategies could lessen those perceptions even while ratings of greater connection were reported.

Conclusions

Our data indicate that leadership development programs can support and foster both professional networks and the sense of collegial connectedness, our proxy for “cohortness,” even when those programs are deployed in virtual settings. Success comes from serious and intentional efforts at planning the curricular and non-curricular experiences of the participants. These data show that while participants can exceed their own expectations for bonding with other cohort members, even with incredible attention to detail, Fellows still felt a sense of disconnection and a desire to be in person. Their responses are likely biased due to the fact that they initially enrolled in an in-person training. Although the pandemic will come to an end, the insights gained from examining how to foster professional networks and “cohortness” among virtually convened participants can benefit leadership development programs that must continue to meet virtually for financial or other reasons and can benefit those programs, which eventually resume in-person convenings.

Ethics approval

Fellows in the Clinical Scholars and FSLI programs provide consent for their data to be used for educational research and program improvement purposes and all ethics guidelines of the Internal Review Board (IRB) at UNC were followed (IRB # 16-1817).

Publication consent

The authors of this manuscript consent for it to be published and warrant that this data is not being considered for publication elsewhere.

Data availability

This data is not publicly available but can be shared upon request.

Author contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a generous grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, as a part of their Leadership for Better Health–Culture of Health initiative. The authors would like to thank Dr. Carol E. Lorenz, PhD for her deft work in editing this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

Conflict of Interest: Mr. Ruben Fernandez J.D. serves as a faculty member and as an executive coach in both the FSLI and CS programs, is the co-author of It-FACTOR Leadership: Become a Better Leader in 13 Steps, a principal text used in both programs, and is the spouse of Dr. Claudia Fernandez. No other authors have conflicts to report.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bailenson, J. N. (2021). Nonverbal overload: A theoretical argument for the causes of Zoom fatigue. Technology, Mind and Behavior, 2(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/tmb0000030

- Baltodano, J. C., Carlson, S., Jackson, L. W., & Mitchell, W. (2012). Networking to leadership in higher education: National and state-based programs and networks for developing women. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 14(1), 62–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422311428926

- Blake, H., Bermingham, F., Johnson, G., & Tabner, A. (2020). Mitigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: A digital learning package. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9) 2997. PMID: 32357424; PMCID: PMC7246821. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17092997.

- Camillus, J. C. (2008, May). Strategy as a wicked problem. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved February 23 2022 https://hbr.org/2008/05/strategy-as-a-wicked-problem

- Campbell, J. C., McBride, A. B., Etcher, L., & Deming, K. (2017). Robert Wood Johnson foundation nurse faculty scholars program leadership training. Nursing Outlook, 65(3), 290–302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2017.02.003

- Cleary, M., Kornhaber, R., Thapa, D. K., Deependra, K., West, S., & Visentin, D. (2020). A systematic review of behavioral outcomes for leadership interventions among health professionals. Journal of Nursing Research, 28(5), e118. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/JNR.0000000000000397

- Cullen-Lester, K. L., Woehler, M. L., & Willburn, P. (2016). Network-based leadership development: A guiding framework and resources for management educators. Journal of Management Education, 40(3), 321–358. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562915624124

- Dave, G., Noble, C., Chandler, C., Corbie-Smith, G., & Fernandez, C. S. P. (2021). Clinical scholars: Using program evaluation to inform leadership development. In C. S. P. Fernandez & G. Corbie-Smith (Eds.), Leading community based changes in the culture of health in the US: Experiences in developing the team and impacting the community (pp. 51–66). London: InTech Publishers.

- Fernandez, C. S. P., Corbie-Smith, G., Green, M., Brandert, K., Noble, C., & Dave, G. (2021b). Clinical scholars national leadership institute: Effective approaches to leadership development. In C. S. P. Fernandez & G. Corbie-Smith (Eds.), Leading community based changes in the culture of health in the US: Experiences in developing the team and impacting the community (pp. 9–28). London: InTech Publishers.

- Fernandez, C. S. P., Green, M., Noble, C. C., Brandert, K., Donnald, K., Walker, M. R., … Corbie-Smith, G. (2021a). Training “pivots” from the pandemic: Lessons learned transitioning from in-person to virtual synchronous training in the clinical scholars leadership program. Journal of Healthcare Leadership, 13, 63–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S282881

- Fernandez, C. S. P., Noble, C. C., Jensen, E., & Chapin, J. (2016b). Improving leadership skills in physicians: A 6-month retrospective study. Journal of Leadership Studies, 9(4), 6–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jls.21420

- Fernandez, C. S. P., Noble, C. C., Jensen, E., Martin, L., & Stewart, M. (2016a). A retrospective study of academic leadership skill development, retention and use: The experience of the food systems leadership institute. The Journal of Leadership Education, 15(2), 150–171. doi:https://doi.org/10.12806/V15/I2/R4

- Fernandez, C. S. P., Noble, C. C., Jensen, E., & Steffen, D. (2014). Moving the needle: A retrospective pre- and post-analysis of improving perceived abilities across 20 leadership skills. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19(2), 343–352. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1573-1

- Fingar, C. (2021) Covid continues to wreak havoc on the events industry: The Covid-19 pandemic has decimated the meetings, incentives, conferences and exhibitions space, with online and hybrid events enjoying mixed success across industries. Investment Monitor. Posted 5.4.21. Retrieved Aug 27 2021 https://investmentmonitor.ai/investment-monitor-events/covid-wreak-havoc-events-industry

- Frich, J. C., Brewster, A. L., Cherlin, E. J., & Bradley, E. H. (2015). Leadership development programs for physicians: A systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 30(5), 656–674. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3141-1

- Furnham, A. (1986). Response bias, social desirability and dissimulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 7(3), 385–400. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(86)90014-0

- Geerts, J., Goodall, A. H., & Agius, S. (2019). Evidence-based leadership development for physicians: A systematic literature review. Social Science & Medicine, 246(2020), 112709. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112709

- Gordon, M., Patricio, M., Horne, L., Muston, A., Alson, S. R., & Panni, M. (2020). Developments in medical education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 63. Medical Teacher, 42(11), 1202–1215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1807484

- Heath, C., Sommerfield, A., & von Ungern-sternberg, B. S. (2020). Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. Anaesthesia, 75(10), 1364–1371. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15180

- Krystal, J. H., Alvarado, J., Ball, S. A., Fortunati, F. B., Hu, M., Ivy, M. E., … Mayes, L. C. (2021). Mobilizing an institutional supportive response for healthcare workers and other staff in the context of COVID-19: The Yale experience. General Hospital Psychiatry, 68, 12–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.11.005

- Kuhfeld, M., Soland, J., Tarasawa, B., Johnson, A., Ruzek, E., Liu, J. (2020). Projecting the Potential Impact of COVID-19 School Closures on Academic Achievement. Educational Researcher. 49(8) 549–565. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X20965918

- Kumar, S., & Heathcock, K. (2014). Information literacy support for online students in higher education. In S. Mukerji & P. Tripathi (Eds.), Handbook of research on transnational higher education (pp. 624–640). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Lam, T. C. M., & Bengo, P. (2003). A comparison of three retrospective self-reporting methods of measuring change in instructional practice. American Journal of Evaluation, 24(1), 65–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/109821400302400106

- FastTrack Leadership, Inc. http://wetrainleaders.com/, Chapel Hill, NC. Accessed March 29, 2022.

- Levine, R. B., Gonzalez-Fernandez, M., Bodurtha, J., Skarupski, K. A., & Fivush, B. (2015). Implementation and evaluation of the Johns Hopkins University school of medicine leadership program for women faculty. Journal of Women’s Health, 24(5), 360–366. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2014.5092

- Liberman-Martin, A.k Ogba, and O.M. Midsemester transition to remote instruction in a flipped-college-level organic chemistry course. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97, 9, 3188–3193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00632

- Nowling, T. K., McClure, E., Simpson, A., Sheidow, A. J., Shaw, D., & Feghali-Bostwick, C. (2018). A focused career development program for women at an academic medical center. Journal of Women’s Health, 27(12), 1474–1481. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2018.6937

- Pratt, C. C., Mcguigan, W. M., & Katzev, A. R. (2000). Measuring program outcomes: Using retrospective pretest methodology. American Journal of Evaluation, 21(3), 341–349. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/109821400002100305

- Qualtrics [ software]. Provo, UT: Qualtrics; 2020.

- Ramachandran, V. (2021, February 2). Stanford researchers identify four causes of ‘Zoom fatigue’ and their simple fixes. Stanford News. https:/news.stanford.edu/2021/02/23/four-causes-zoom-fatigue-solutions/ accessed 2.23.22

- Rittel, H. W. J., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730

- Roddy, C., Amiet, D. L., Chung, J., Holt, C., Shaw, L., Mckenzie, S., … Mundy, M. E. (2017, November 21). Applying best practice online learning, teaching, and support to intensive online environments: An integrative review. Frontiers in Education, 2. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2017.00059

- Rohs, F. R. (1999). Response shift bias: A problem in evaluating leadership development with self-report pretest-posttest measures. Journal of Agricultural Education, 40(4), 28–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.1999.04028

- Smith, B. J., & Lim, M. L. (2020). How the COVID-19 pandemic is focusing attention on loneliness and social isolation. Public Health Research & Practice, 30(2), 3022008. doi:https://doi.org/10.17061/phrp3022008

- Sonnino, R. E. (2013). Professional development and leadership training opportunities for healthcare professionals. The American Journal of Surgery, 206(5), 727–731. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.07.004

- Sprangers, M., & Hoogstraten, J. (1989). Pretesting effects in retrospective pretest-posttest designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(2), 265–272.

- Vidmar, D. J. (2006). Reflective peer coaching: Crafting collaborative self-assessment in teaching. Research Strategies, 20(3), 135–148. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resstr.2006.06.002