ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to establish historical enrollment trends, student demographics, and home-based pedagogies of nonclassroom-based schools in California in an effort to gain insights into lesser-known homeschooling practices. According to the United States Department of Education, in 2016, homeschooling had progressively increased to 3.3%. To determine whether California has a similar trend in students’ learning outside of a traditional classroom-based learning environment, we evaluated eight years of student enrollment data from the California Department of Education. Potential implications for this student population in relation to California’s vaccination legislation, as well as the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, are explored. The demographic information of nonclassroom-based public school students in California was summarized and compared to that of classroom-based students in California and homeschooled students in the United States, finding less ethnic diversity in nonclassroom-based schools. Our findings of home-based pedagogies suggest families of California nonclassroom-based charter schools lean more toward a standards-based, traditional (57.8%) pedagogy, followed by Classical (10.8%) and Project/Unit-based (9%).

Introduction

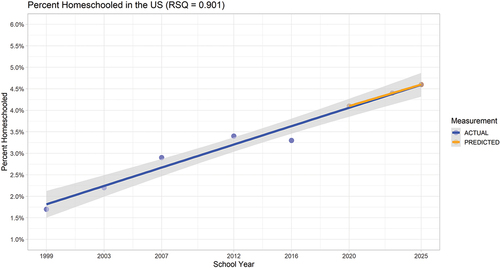

The modern homeschooling movement originated in the 1970s, predominantly from the desire of Protestant parents to provide their children with an alternative education that was more compatible with their religious beliefs and ideological backgrounds; however, many child-centered families homeschooled with the goal of improving their children’s education (Stevens, Citation2001; Van Galen, Citation1991). During the mid-1970s, an estimated 0.03% of all school-age children were homeschooled (Lines, Citation1999). During the 1980s, homeschooling parents in the United States sought the legal right to do so, as homeschooling was considered to be a form of truancy (Isenberg, Citation2007). After a series of successful legal battles, homeschooling was legalized in all 50 states by 1993 (Angelis, Citation2008). Since then, parents have become increasingly aware of this alternative educational option through the expansion of available means of homeschooling, particularly through the disruption in K-12 education caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. In an effort to quantify this segment of K-12 education, in 1999, the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) at the Institute of Education Sciences began collecting nationally representative data (McQuiggan & Megra, Citation2017; Snyder, de Brey, & Dillow, Citation2019), when it was estimated that 1.7% of all children between ages 5 and 17 were homeschooled. The most recent data from the 2016 academic year indicate an increase to 3.3% nationally, or 1,689,726 children being homeschooled in total, according to NCES.

The growth in the percentage of homeschooled students in the U.S. over the past two decades has been accompanied by an increase in the scholarly research on this nontraditional form of K-12 education. Kunzman and Gaither (Citation2020) wrote a comprehensive summary of homeschooling research, distilling the body of research and grouping it in the following eight general topics: student demographics; motivation of parents to homeschool; homeschool curricula and practice; academic outcomes; socialization of children; psychological and physical health; legal aspects of homeschooling; relationships with U.S public schools; and international homeschooling. In this paper, we will take a detailed descriptive look at independent study charter schools in California, thus contributing to the scholarly research on homeschooling in the areas of (1) student demographics and enrollment trends; (2) legal aspects of homeschooling; (3) curricula and home-based pedagogies; and (4) relationships with public schools. We will also discuss the potential implications of the Covid-19 pandemic on the demographic enrollment trends of nonclassroom-based schools as well as homeschooling in general.

At the state level, demographic data for homeschooled students in the U.S. have been limited because individual states have inconsistent reporting requirements for parents electing to homeschool their children (Isenberg, Citation2007). As a result, researchers must rely on volunteer parent survey results to gain demographic insights into this historically elusive segment of K-12 education. Currently, the most comprehensive national student demographic data are collected every 3 to 4 years by the National Household Education Survey with voluntary parent surveys (Snyder et al., Citation2019). To compound this issue, it has been reported that parents of homeschooled children have demonstrated a reluctance to complete government-sponsored surveys about their children and household (Kaseman & Kaseman, Citation2002; Lines, Citation2000; McPhee et al., Citation2015). Public schools that offer nonclassroom-based, homeschool-like educational programs, such as California independent study charter schools, may help to provide a more complete demographic profile of a particular geographical region for homeschooled students, as that demographic information is required by the families at the time of enrollment and is publicly available.

State laws requiring vaccines for all classroom-based students may have unintended consequences in terms of increasing the percentage of homeschooled students. In June 2015, the California Senate signed into law the Senate Bill (SB-277), removing the personal belief exemption for required school vaccinations. Committee hearings on this bill indicated that California would be denying free public school education to the children of parents choosing not to vaccinate through such an exemption, according to the California Constitution, Article IX – Section 9, written in 1879, guaranteeing a free public education for all children. For this reason, SB-277 was amended to allow California independent study charter schools to enroll students with a personal exemption waiver for vaccines. Senate Bill 277 went into effect on July 1, 2016. Currently, new legislation in California is being proposed and debated that would require Covid-19 vaccines for all students attending a classroom-based public or private school. If the proposed legislation is signed into law, home-based education would be the only remaining educational option for California parents choosing not to vaccinate their children with the Covid-19 vaccine, or other required school vaccines.

According to Kunzman and Gaither (Citation2020), researchers have been challenged to summarize and describe the variety of homeschooling practices and curricula because of the wide variety of approaches used by families (Neuman & Guterman, Citation2017), as well as the difficulty researchers have experienced in gaining access to homeschooling families. It has been reported that some homeschooling families adhere to a well-structured, more formalized instructional day (Gann & Carpenter, Citation2019; Neuman & Guterman, Citation2017; Taylor-Hough, Citation2010), whereas other studies have discovered that homeschooling families lean toward an eclectic approach in regard to curricula and instructional strategies (Bachman & Dierking, Citation2011; Kraftl, Citation2013). Also, the home-based pedagogy of homeschooling families does not appear to remain static over time. According to a 10-year longitudinal study of 225 homeschooling families in Pennsylvania (Hanna, Citation2012), homeschooling families have evolved their homeschooling approaches as their children matriculate in their schooling. Of the research studies done to date, limited sample sizes of homeschooling families have made it difficult to gain a macroview of the generalized types of instructional approaches used by homeschooling families in the U.S. This is particularly challenging when attempting to describe a segment of K-12 education known for a nontraditional and nonconforming approach to learning.

In California, the relationship between homeschooling families and public schools is formalized through independent study charter schools, a type of nonclassroom-based school. To clarify terminology used in this paper to describe nonclassroom-based schools, the term independent study charter school is formally used in the California Education Code to describe public schools that offer nonclassroom-based learning. Such schools in California are also described as personalized learning schools. The term homeschooled is used in this paper to describe children who are educated through a Private School Affidavit (PSA) in California; these students are not enrolled in a public independent study charter school and are instead privately educated at home. As a further point of clarification, California independent study charter schools are largely not online schools. Many nonclassroom-based charter schools in California are structured to support home-based learning, which in many ways, resembles the pedagogy of privately homeschooled families.

The relationship between homeschooling families and California public schools has been in the making for the past three decades. In 1992, California Senator Gary Hart introduced SB1448, a bill that legally allowed the formation of charter schools in California and opened the door for the development of nonclassroom-based independent study public charter schools. Each state differs in the policies and options available for alternative, nonclassroom-based students, with and without public education fund involvement. Parents interested in educating their child outside a traditional classroom-based school have three options in California: (1) file a PSA with the California Department of Education (CDE); (2) enroll the child in an independent study charter school; or (3) enroll the child in a blended learning school, where part of the instructional time occurs in a classroom and the rest is done at home.

For the first option, the California parent must file a PSA online with the CDE before October 15th of each year to be considered a private school (i.e., legally homeschooling). No public funds support such private schools; there are no required state-mandated assessments, no reporting or required standards-based instruction, and there is no required credentialed teacher oversight. The parent provides the entire curriculum and all educational services for the education of their child and determines when the child has met the requirements for graduation.

For the second option, some independent study charter schools are purely online, but most offer a diverse curriculum, both textbook and digital, and support instruction through a local network of school-approved community partners that offer in-person tutoring and instruction. As public schools, such organizations assign a credentialed teacher to every student enrolled at a 25:1 student-to-teacher ratio, in accordance with California Education Code 51745.6(d). The credentialed teachers work closely with the parents and students to develop a personalized learning plan. Public charter school funds are used to purchase necessary standards-based curriculum and to pay for instructional activities. Furthermore, such schools may have classroom facilities for group classes, but the facilities must be located within the authorizing school district’s boundaries, and the instructional time must comprise less than 20% of total weekly instruction. Alternatively, students may also receive 100% of their weekly instruction outside the classroom.

Classroom-based California charter schools require a minimum of 20% weekly classroom instructional time, though most provide 100% of instruction in the classroom. Due to this flexibility, some classroom-based charter schools have developed an academic schedule that allows for some instruction at home. In this paper, the term blended learning school (also referred to as hybrid schools) is used to describe K-12 schools that offer a combination of traditional classroom-based learning and independent study charter school-style learning. A student enrolled in such a school might attend classes at a classroom-based school facility on Tuesdays and Thursdays, while learning at home on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, a schedule similar to that of an independent study charter school student. Flexibility is afforded in assigning class schedules if the classroom instructional time exceeds 20% of total instruction per week.

A study was conducted to explore and summarize the demographics, enrollment trends, and pedagogy of home-educated public charter school students enrolled in three California independent study charter schools. Those schools do not require students to use school-adopted curricula or follow a particular pedagogy, other than meeting California State Content Standards for the student’s grade level. Parents are allowed to select the curricula and home-based pedagogy. As such, the results presented in this paper, based on a large sample size (n = 5,511), may help to provide insights into the homeschooling practices of the more elusive PSA students in California and privately homeschooled students in the U.S. Enrollment trends and demographic information of nonclassroom-based K-12 education in California will be illustrated, and the enrollment implications of the Covid-19 pandemic on homeschooling will be discussed.

Methods

The California independent study charter schools participating in this study were South Sutter Charter School, Ocean Grove Charter School, and Sky Mountain Charter School, all of which were accredited through the Western Association of Schools and Colleges. Students in grades K-12 resided in 18 counties throughout northern and southern California, representing students from rural, urban, and suburban communities (). According to California Education Code 51747.3(b), an independent study charter school may enroll students in any county contiguous to the county of the authorizing school district. Hence, Ocean Grove Charter School is authorized in Santa Cruz County; Sky Mountain Charter School is authorized in San Bernardino County; and South Sutter Charter School is authorized in Sutter County.

Figure 1. Map illustrating the counties of enrolled students served by Ocean Grove Charter School, Sky Mountain Charter School, and South Sutter Charter School.

All participating schools were established and are managed by Innovative Education Management, a nonprofit charter school management organization. The approved charter language and identical school policies, teacher training, and instructional resources available to students are similar for each of the schools. For the 2015/2016 academic year, $2,200 of instructional funds was allocated for each student in grades TK-8, and $2,700 was allocated for each student enrolled in grades 9–12. The credentialed teacher assigned to students was responsible for using these instructional funds to purchase the necessary curriculum materials and educational services to support each student’s personalized learning plan, which also aligned with grade-level California Content Standards.

The participating independent study charter schools were structured to support strong parent involvement in the selection of curriculum and pedagogy they would utilize to educate their child at home. Since parents often enroll their children in one of these independent study charter schools with the goal of educating them at home in a particular way, teachers working at these schools were well-trained in a wide variety of curricula and home-based pedagogy used by homeschooling families. In fact, since 2005, participating independent study charter schools have created professional development training for teachers on a diverse range of homeschooling pedagogy and curricula that parents commonly use.

The term educational philosophy is commonly used at these three participating schools and by similar independent study charter schools in California, as well some PSA homeschooling parents. For the purpose of this paper, we use that term to describe the type of home-based pedagogy, curricula, and instructional delivery modality used in home-educated settings. In an effort to capture the distribution of educational philosophies used at the three independent study charter schools, school administrations required all teachers to complete a survey to identify the educational philosophy for each of their students so that the school administration could use that information to plan future professional development sessions for their teachers. The decision to survey teachers instead of parents was made because the credentialed teachers had been formally trained in distinctions between the different educational philosophies and instructional modalities; therefore, assigned teachers would be able to objectively identify the appropriate educational philosophy for each student, if known. The decision to identify the educational philosophies based on the student and not the parent was made because some families with multiple children may have different educational philosophies based on the unique learning styles, personality types, and individual learning plan of each child.

In February 2016, credentialed teachers from the three participating schools were surveyed regarding the educational approaches used by each student assigned to the teacher. A comprehensive list of educational philosophies was presented, and teachers were asked to indicate, from their perspective, one or more of the philosophies followed by the parents of each of their students. Teachers were then presented with the same list of educational philosophies in a subsequent question and were asked to choose a single option from that list to indicate the educational philosophy that best matched the student’s family. Educational philosophy options used in the survey were the same ones listed in . Surveys were conducted using the Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) online survey software (version 02.2016). A high survey completion rate of 100% was obtained because it was a required task for all teachers at the participating schools, and completion was verified by school administration. In this study, a total of 309 teachers, representing 5,511 students, completed the survey.

Table 1. Summary and description of educational philosophies followed by the parents of students enrolled in California independent study charter schools.

The dataset received from the California Department of Education in June 2018 comprised all private schools between the years 2010 and 2017, including student enrollment data for all classroom-based and homeschool-based private schools. To separate private homeschools from traditional classroom-based private schools, schools were removed from the dataset if their total enrollments exceeded 10 students and/or if enrollment at any given grade level at a school exceeded 3 students. All remaining private schools were assumed to be operating as private homeschooling families in California. The demographic information concerning homeschooled students is not collected in California and was therefore not available.

The CDE organizes all California charter schools by county in a charter school map, grouping them into three categories: independent study, site-based instruction, and combination. Blended learning schools fall into the last of these. It was not possible to determine the enrollment trends of students in blended learning charter schools because many such schools only enroll a portion of their students in a blended learning program, with most following a traditional classroom-based schedule. For this reason, we did not include blended learning schools in our analysis of enrollment trends or student demographics.

Student enrollment and demographic information for all identified nonclassroom-based charter schools was collected from the publicly available Ed-Data website, a partnership between the CDE, EdSource, and the Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team/California Schools Information Services designed to compile and organize comprehensive data about California public schools for the purpose of informing educators, policy makers, the legislature, parents, and the public. The master dataset was analyzed using SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 25.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM). Regression analysis was performed using the R statistical software (version 3.5.1).

Results and discussion

Educational philosophies

Like classroom-based public schools, nonclassroom-based independent study charter schools in California are responsible for ensuring that students meet the state standards for each grade level. Each student is assigned a credentialed teacher charged with monitoring, overseeing, and facilitating learning through periodic meetings with the parents and student. Since the establishment of California charter schools in 1992, independent study charter schools have been allowed a high level of flexibility in determining the curriculum and instructional opportunities for enrolled students, which these schools utilize to create personalized learning plans to meet their different academic needs. Those learning plans are created in a collaboration between the credentialed teacher, parent or guardian, and student. The three independent study charter schools used in this study are closely related to their PSA counterparts because of the high level of parent involvement in the selection of the curricula, learning activities, and daily home instruction with their child. The similarity these public schools have to private homeschools opens up the opportunity to explore a variety of future research questions on this segment of K-12 education through the lens of independent study charter schools.

In this paper, the term educational philosophy, a phrase that is commonly used among independent study teachers and homeschooling parents to provide a general description of their instructional approach to educating a child at home, offers an explanation of the general curriculum, pedagogy, and instructional delivery modality in nonclassroom-based K-12 learning. The educational philosophies followed by parents can be very influential in the development of a personalized learning plan for the child, either at independent study charter schools or in private homeschool settings. describes the distinguishing characteristics, instructional approaches, and commonly used curricula for each educational philosophy.

However, regardless of the educational philosophy of the parent, it is the responsibility of the independent study charter school to ensure that each child is learning at the appropriate grade level, following the state standards for public school students, and working toward meeting or exceeding the requirements of state assessments. Credentialed teachers at independent study charter schools are charged with identifying any missing content standards in non-traditional curricula used by students as well as for assigning supplemental curricula, as necessary, to fill any instructional gaps. As a result, this added layer of influence may have an effect on distribution of educational philosophies reported at these schools and should be considered when extrapolating these results to the pedagogy and curriculum selection of PSA homeschooling families.

If there is no school-adopted curriculum at an independent study charter school, as is the case with these three nonclassroom-based independent study charter schools, student assessment scores and parent educational philosophies can be the two most significant variables in determining the curriculum of a personalized learning plan. Student learning styles and personality types can also play an important role. The parents of the students enrolled in the three participating schools in this study took an active role in the selection of the curriculum and learning activities used to educate their children, typical of most such parents. Prior to selecting any curriculum, the credentialed teachers at these three schools used the i-Ready® diagnostic assessments for reading and math and the state-mandated California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress results to help identify the particular learning needs of each student. Afterward, the parents and credentialed teachers discussed curriculum options and instructional strategies.

Parents formulate their approach to homeschooling their child based on internet research, including social media, and through conversations with other homeschooling friends and teachers. Many parents may not recognize that they are teaching their child according to a specific homeschooling pedagogy, thus making it challenging for researchers to acquire this information directly from parents. Surveying the teachers, who are trained to identify educational philosophies and learning styles, instead of surveying the parents, allowed for a more accurate and complete picture of the curricula and pedagogy used at the independent study charters schools. In an effort to gain insights on the distribution of instructional practices among students, 309 credentialed teachers from the participating schools were surveyed and asked to use their professional judgment to identify the educational philosophies that best describe the pedagogy for that student. Students remain with their assigned teacher as the student progresses through the grade levels, allowing the teacher to become very familiar with the educational approaches used by each of their students and families.

Traditional philosophy was the most commonly followed primary educational philosophy, representing 57.8% of the students. This philosophy typically features a standards-based curriculum that is also commonly used in classroom-based public schools. As independent study charter schools in California are also public schools and must follow the adopted state content standards, this is not surprising. We also expect this percentage to be higher than what is practiced with PSA families. Multiple studies have documented the fact that, when parents first homeschool their children, they lean toward a more traditional classroom curriculum to teach “school at home” with their children, until they progress to alternative approaches that may be less structured (Bell, Kaplan, & Thurman, Citation2016; Gann & Carpenter, Citation2019; Gray & Riley, Citation2013; Kraftl, Citation2013). For this reason, results should be interpreted as a snapshot in time for a particular population of students and families and suggest these educational philosophies may change for any given family, as the family and student evolve in their home education experiences.

Classical was the second most common primary educational philosophy, with 10.8% of the students using classic literature in a formalized curriculum in well-defined stages of grammar, logic, and rhetoric. The Classical approach to education is unique in that the study of Latin is woven throughout the stages of a child’s education, ranging from grammar charts in the initial learning levels and Latin composition at the high school level (Hahn, Citation2012). Further, as defined by Perrin (Citation2004), a classical approach is both authoritative and enduring, “begun by the Greeks and Romans, developed through history and now being renewed and recovered in the 21st century” (p. 6).

The project/unit-based educational philosophy was identified with 9% of the students and is described as thematic and interdisciplinary in its instructional approach. Projects often revolve around STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), with parents participating in open-ended, creative ways to promote a child’s interest (Bachman & Dierking, Citation2011). Only 4.8% of the students were primarily taught online for all of the core subjects, although instructional funds can be used to acquire technology for all students. Online learning is more of an instructional delivery modality than it is an educational philosophy but was included in the survey to capture the students/families who prefer the use of online resources to achieve academic core content standards. Reasons for choosing an online approach to education can vary from easy access to high quality virtual curriculum to an engaging and personalized curriculum (Pell, Citation2018). However, with such a small percentage of students primarily learning through online resources, California independent study charter schools such as those described in this research could not be appropriately described as cyberschools, eSchools, or virtual charter schools.

The fifth most common educational philosophy was Unschooling, utilized by a reported 4.7% of all students. Within this unregimented approach to education, there are variations in the degree of structure amongst families found in either the educational content or the learning process (Neuman & Guterman, Citation2017). A formal curriculum is not typically utilized under this educational philosophy. Unschooling can further be described as either “relaxed homeschooling” or as being completely child-led and created (Gray & Riley, Citation2013, p. 8).

The Charlotte Mason, Waldorf, Delayed Academic Approach, and Montessori educational philosophies represented less than 2% of the students. In total, all the educational philosophies discussed in this paper represent 92.5% of the students, with only 7.5% of the teachers selecting the Unknown/Other category.

The percent distribution of educational philosophies changed when the teachers were given the option to select more than one educational philosophy, indicating that 73.7% of all students used some type of Traditional standards-based classroom curriculum. This increase from 58.7% using Traditional as the primary philosophy may reflect the common practice of using standards-based curricula to fill any instructional gaps in non-traditional K-12 education. For example, a student following the Montessori curriculum may need to fill in certain missing California content standards. Furthermore, when teachers were given the option of selecting more than one philosophy, the Online-Based learning modality increased to 14.1%, from 4.8% as the primary. This may likely be attributed to students utilizing online content for some but not all of their instruction.

Even though, in many ways, the active parent involvement curriculum selection and home instruction by parents at California independent study charter schools described in this paper are similar to the private homeschooled students through a PSA, the idea that this distribution of educational philosophies is also reflective of the educational philosophies of parents who privately homeschool their children cannot be generalized. We speculate that the former may be less inclined to follow the Traditional educational philosophy because such students are not required to adhere to the California content standards and do not participate in any annual summative state assessments. However, the broad geographic distribution of the students in this study () and the large sample size of 5,511 students, comprising 4.8% of all California independent study charter school students in 2016, suggest that these results are representative of the independent study, nonclassroom-based charter schools throughout California.

Enrollment trends

As we transition from the pandemic to the endemic phase of Covid-19, the disruption to traditional norms of classroom-based K-12 education may result in a shift in the way parents perceive their educational options for their children, which may cause more families to choose nonclassroom-based educational options for their children. Several studies have investigated the reasons that parents choose to homeschool their children (Boschee & Boschee, Citation2011; Green & Hoover-Dempsey, Citation2007) but quantifying enrollment for these nonclassroom-based students has been more challenging, due in part to varying reporting requirements of each state (Isenberg, Citation2007). In California, the reporting requirements for PSA and independent study charter school students are well established. In this study, we sought to examine the historical, pre-pandemic enrollment trends for nonclassroom-based enrollment in California and make comparisons to national enrollment trends during the same period.

According to a recently published report from the U.S. Department of Education, in 2016, an estimated 3.3% of all school-aged children were homeschooled in the United States (Snyder et al., Citation2019). The department first began collecting these data in 1999, when it indicated that 1.7% of students were homeschooled (). A well-correlated, positive linear regression (R2 = 0.901) was found when the percent of homeschooled students was plotted against year (). Assuming this linear trend continues, a regression model was used to estimate the percent of homeschooled children in the United States in 2020, 2023, and 2025 (). It is projected that 4.1% of the national K-12 student population in the United States will be homeschooled in 2020, increasing to approximately 4.6% by 2025.

Figure 2. Linear regression correlation of the estimated percentage of school-aged children educated at home in the United States.

Table 2. Predicted estimates of the percentage of school-aged children who will be homeschooled in the US in 2020, 2023 and 2025, based on the US department of education parent survey results from 1999 through 2016.

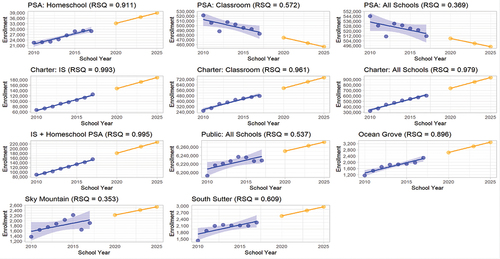

In light of these nationally reported trends, we have summarized the enrollment trends for nonclassroom-based schools in California, the most populous state. The CDE collects student enrollment data for all public and private schools, so, in California, it is possible to accurately determine the percentages of students being educated in nonclassroom-based schools for any given year, rather than relying on survey estimates, as is the case when examining broader, national trends. In this paper, nonclassroom-based enrollment trends were evaluated for California private homeschools (PSA) and California public independent study charter schools.

The enrollment data for years 2010 through 2017 are reported in . Linear regression models were used to project student enrollment through 2025 for the various categories of California public and private schools (). Total private school enrollment was variable each year, resulting in a weak model prediction of declining enrollment (R2 = 0.369). The private school enrollment data were sorted into two groups: PSA Homeschool and PSA Classroom. Separating the classroom-based private schools from the total private school dataset generated a slightly better linear correlation (R2 = 0.572), but the negative sloping regression line suggests declining enrollment in California’s classroom-based private schools. However, when the dataset was filtered to estimate the enrollment of PSA homeschooled students, a strong positive linear relationship was found (R2 = 0.911). According to the linear regression model estimates, the number of privately homeschooled students in California is predicted to increase from 28,928 in 2017 to 38,925 students by 2025.

Figure 3. Linear regression correlations for K-12 student enrollment in various types of public and private schools in California.

Table 3. Public and private K-12 student enrollment in California (2010–2017).

Total student enrollment in independent study charter schools increased from 66,877 students in 2010 to 125,724 students in 2017. When plotted against year, a well-correlated linear relationship was found (R2 = 0.993). In 2017, independent study charter school student enrollment represented 20.9% of the total charter school student enrollment in California, with a reported 125,724 K-12 public school students educated outside a traditional classroom-based school. If enrollment trends continue linearly, California will have an estimated 188,768 public school students enrolled in independent study charter schools by 2025.

Grouping the public independent study charter school enrollment and private homeschool enrollment together, a total of 154,652 students in California were educated outside a purely traditional classroom-based school learning environment in 2017 (). Using the linear regression model parameters, the total enrollment of such students in California is expected to increase to approximately 227,693 students by 2025 (R2 = 0.995). This increase echoes the findings of the U.S. Department of Education that indicate an increase in student enrollment in homeschooling at the national level. Given the growing prominence of this alternative form of public and private school education in the United States, there is a need for thorough academic research on the teaching pedagogy and best practices in nonclassroom-based forms of K-12 education.

Our analysis indicates that California had a reported 2.1% of total private and public school enrollment in 2016 that was classified as nonclassroom-based. According to our enrollment predictions, 3.4% of all K-12 students in California will be educated at home by 2025. It is unknown if these numbers are also representative of other states. However, this study demonstrates that a well-correlated, linear enrollment growth trend of nonclassroom-based education (public and private) in California does correspond with positive linear growth trends reported in the U.S. through national surveys conducted by the U.S. Department of Education (Snyder et al., Citation2019).

Independent study charter school enrollment represented 20.7% and 20.9% of total statewide charter school enrollment in 2010 and 2017, respectively. A two-sample chi-squared test for equality of proportions with continuity correction was used to determine if the student enrollment in California independent study charter schools was outpacing the total enrollment growth in classroom-based charter schools. The result was χ2 = 8.3837, with 1 degree of freedom, corresponding to p = .02033. The 0.2% enrollment increase of independent study charter schools from 2010 to 2017 was determined to be statistically significant, with a 95% confidence interval.

It should be noted that the onset of a global Covid-19 pandemic has caused this linear homeschooling projection to reach an inflection point, with outcomes yet to be determined with enrollment data. As families experienced remote learning with little notice or preparation because of the pandemic, it became apparent that the leading role of a parent in the learning of a child in a homeschooling environment was critical to maintaining the education of the child (Green-Hennessy & Mariotti, Citation2021; Sssenkusu, Ssempala, & Mitana, Citation2022). Parents’ concerns regarding safety from Covid-19 for their children within a school setting, along with issues surrounding the educational effects of a year-long, swift change to remote instruction, led to an increase in the number of families viewing homeschooling as a viable option (Duvall, Citation2021).

Response to the Covid-19 pandemic also resulted in an increased awareness of the need to regularly survey families at the national level, through the Household Pulse Survey, to measure how the virus affected American households, including the number of households being used for educational purposes. The Household Pulse Survey data indicate that the number of homeschool parents increased to five million in fall 2020 (Duvall, Citation2021). Further, and specific to California, the pending legal policies surrounding childhood vaccinations makes the need to examine this enrollment trend more urgent.

In June 2015, California signed into law SB277, a Senate bill removing the personal belief exemption for required school vaccinations. Committee hearings indicated that California would in this way be denying free public school education to the children of parents wishing to avoid vaccination through such an exemption. For this reason, SB277 was amended to allow California independent study charter schools to enroll students with a personal exemption waiver for vaccines. Based on the enactment of this law, it is plausible that the enrollment rate of students at California independent study charter schools may increase at a greater rate than estimated in this paper. Similarly, if Covid-19 vaccines become required for enrollment in classroom-based schools, some parents who choose not to vaccinate their children will need to select a nonclassroom-based learning option for their children.

In 2020 and 2021, the Covid-19 pandemic effectively forced all K-12 students and parents in the United States to participate in some form of nonclassroom-based learning. At this time, we do not have any data that would indicate how the enrollment of nonclassroom-based schools would change in the post Covid-19 era, although, as mentioned, we surmise that this could be an inflection point for the well-correlated linear growth rates of nonclassroom-based enrollment described in this paper. The practice of educating a child at home has become more normalized within society during the pandemic, forcing students and families to participate in this alternative form of education, a school choice option that they may not have fully recognized, understood, or chosen prior to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Demographic summary of students

Demographics of students enrolled in California independent study charter schools were compiled and summarized in this paper to draw comparisons with the national averages of homeschooled students and to students enrolled in traditional classroom-based schools in California. Demographic information of privately homeschooled students in California was not available because the California Department of Education does not collect student demographics through their PSA application. The 2016 academic year was selected for California student demographic data so that it could be compared to the most recent national demographic data for homeschooled students conducted by the U.S. Department of Education (Snyder et al., Citation2019). California’s independent study charter schools are included as part of the 6,226,737 total public school students reported for 2016. Likewise, Ocean Grove, Sky Mountain, and South Sutter Charter Schools represent a subset of the 113,272 total students enrolled in independent study charter schools for 2016.

Of the 113,272 independent study charter school students in 2016, 55% were reported as low socioeconomic status (SES), a much higher rate than the 21% reported nationally for homeschooled students. However, it was much closer to the statewide average of 60.5% for all California K-12 public school students (). The three participating schools in this study reported substantially lower percentages of low SES students, with 18.3%, 25.8%, and 37.4% in Ocean Grove, Sky Mountain, and South Sutter, respectively. This may be partially attributed to the higher income counties served by the participating independent study charter schools, such as Silicon Valley for Ocean Grove and Orange County for Sky Mountain (). The enrollment of students in the participating schools was never capped or restricted by any means, such as a lottery system.

Table 4. Student demographics of California K-12 students and homeschooled students in the United States.

In California, 22.1% of all public school students were identified as English language learners in 2016 (). Statewide, a much lower percentage of independent study charter school students (6.7%) were identified as English language learners. Ocean Grove, Sky Mountain, and South Sutter reported 2.8%, 1.6%, and 2.7%, respectively, of English language learner student enrollment in 2016. We speculate that the substantially lower percentage of English language learners enrolled in California independent study charter schools may reflect the inherent challenges associated with acquiring English language proficiency in a household learning environment where English is likely not the primary language spoken. English language learner students enrolled in the participating schools received in-person, weekly English language tutoring, with a standards-based curriculum and formative assessments in reading occurring periodically throughout the year. The national homeschool estimate of 16% English language learners reported by the U.S. Department of Education should be interpreted with caution because the data were collected through surveys voluntarily completed by parents of K-12 children rather than through any formal English language assessment, such as the English Language Assessments for California (ELPAC).

Generally speaking, California independent study charter schools are less ethnically diverse than the population of K-12 public school students statewide, with an average of 42% of students reported as White, Non-Hispanic, compared to 24.1% for all California public school students in 2016 (). The ethnic diversity of California may contribute to the findings of fewer White, non-Hispanic homeschooled students than the national average (59%). California independent study charter schools do show a slightly higher percentage of Black, non-Hispanic (7.1%) students compared to the statewide public school average of 5.8%. The demographic makeup of nonclassroom-based students in California does not reflect the statewide student demographic averages, indicating that homeschooling may be gaining ground as a more acceptable form of education within certain ethnicities and communities.

Conclusion

The Covid-19 pandemic has forced most K-12 aged children into a nonclassroom-based learning environment, bringing universal awareness to this alternative form of K-12 education. California independent study charter schools that are structured to involve parents in the selection of curriculum and pedagogy for educating their child at home may help provide researchers a window into educational practices of the less accessible privately homeschooling families. Our research has shown that a traditional approach to learning and the use of common resources found in classrooms accounted for 57.8% of the primary curriculum used by students in these three participating schools, indicating that only 4.8% of parents opt for online curriculum as their main curriculum type. Classical education (11%) and project-based/unit learning (9%) followed in popularity. Emphasis on California Content Standards at the independent study charter schools may skew curricula results more toward traditional standards-based classroom curricula when compared to the homeschooling practices of PSA families who are not required to follow state content standards.

If the U.S. Department of Education estimates are accurate and this sector of education continues to grow in the ways demonstrated in this paper, it is projected that 1 in 22 students, or 4.6% of all school-aged children, will be homeschooled by 2025. In California, children learning outside of a traditional classroom environment have become increasingly more common, representing a reported 2.1% of all public and private school students in 2016. Similar to national enrollment growth trends, California enrollment data showed a well-correlated, positive linear trend for students being educated outside a traditional classroom, with student enrollment in independent study charter schools representing 20.9% of all California charter school students in 2017. We speculate that the growth in homeschooling enrollment over time demonstrated in this paper may currently be at an inflection point as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic that has had the effect of making parents more aware of and familiar with nonclassroom-based learning options for their children.

Independent study charter school student demographic information was collected from public records at the California Department of Education and summarized to indicate a less ethnically diverse population, with the exception of a slight increase in the percentage of Black/Non-Hispanic students (7%) compared to all California public schools (5%). The percentage of low socioeconomic students enrolled in California independent study charter schools (55%) was similar to total student enrollment in California public schools (61%), but substantially higher than the national estimate of 21% for homeschooled students. The inherent challenges associated with home educating an English learner student in a home where English may not be the primary language spoken could contribute to the relatively low percentage of English learner students enrolled in California independent study charter schools (7%) compared to the statewide average of 22%. Demographic information of privately homeschooled K-12 students in California was not available from the California Department of Education.

This analysis indicates that private homeschooling and independent study charter school enrollment will become an increasingly common educational option for families in the future. The enrollment trends described in this paper reveal a societal shift in terms of the growing number of parents seeking nontraditional, nonclassroom-based K-12 learning opportunities for their children. We speculate that the post-Covid-19 era of K-12 education will move to a more nonclassroom-based learning environment, as parents more fully understand alternatives to a traditional classroom learning experience for their child.

The student demographics, enrollment data, and home-based pedagogies described by educational philosophies in this study provide a foundation for those interested in researching this most elusive and least understood sector of education in the United States.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Angelis, K. L. (2008). Home schooling: Are partnerships possible? [ Doctoral dissertation]. University of Maryland. Retrieved September 3, 2018, College Park. http://drum.lib.umd.edu/bitstream/1903/8061/1/umi-umd-5221.pdf

- Bachman, J., & Dierking, L. (2011). Co-creating playful environments that support children’s science and mathematics learning as cultural activity: Insights from home-educating families. Children, Youth and Environments, 21(2), 294–311. doi:10.7721/chilyoutenvi.21.2.0294

- Bell, D. A., Kaplan, A., & Thurman, S. K. (2016). Types of homeschool environments and need support for children’s achievement motivation. Journal of School Choice, 10(3), 330–354. doi:10.1080/15582159.2016.1202072

- Boschee, B. F., & Boschee, F. (2011). Profile of homeschooling in South Dakota. Journal of School Choice, 5(3), 281–299. doi:10.1080/15582159.2011.604982

- Cooper, H. (2012). Looking backwards to move forwards: Charlotte Mason on history. The Curriculum Journal, 23(1), 7–18. doi:10.1080/09585176.2012.650467

- Corry, S. K. (2006). A comparison of Montessori students to general education students as they move from middle school into a traditional high school program [ Doctoral dissertation]. University of Nebraska Omaha.

- Duvall, S. (2021). A research note: Number of adults who homeschool children growing rapidly. Journal of School Choice, 15(2), 215–224. doi:10.1080/15582159.2021.1912563

- Edwards, C. P. (2002). Three approaches from Europe: Waldorf, Montessori, and Reggio Emilia. Early Childhood Research and Practice, 4(1), 2–14. Retrieved September 3, 2018. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED464766.pdf

- Gann, C., & Carpenter, D. (2019). STEM educational activities and the role of the parent in the home education of high school students. Educational Review, 71(2), 166–181. doi:10.1080/00131911.2017.1359149

- Gray, P., & Riley, G. (2013). The challenges and benefits of unschooling, according to 232 families who have chosen that route. Journal of Unschooling & Alternative Learning, 7(14). Retrieved September 3, 2018. https://jual.nipissingu.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/25/2014/06/v72141.pdf

- Green-Hennessy, S., & Mariotti, E. C. (2021). The decision to homeschool: Potential factors influencing reactive homeschooling practice. Educational Review, 1–20. doi:10.1080/00131911.2021.1947196

- Green, C. L., & Hoover-Dempsey, K. V. (2007). Why do parents homeschool? A systematic examination of parental involvement. Education and Urban Society, 39(2), 264–285. doi:10.1177/0013124506294862

- Hahn, C. (2012). Latin in the homeschooling community. Teaching Classical Languages, 4(1), 26–51. Retrieved September 3, 2018. https://tcl.camws.org/sites/default/files/Hahn_0.pdf

- Hainstock, E. G. (1997). The essential Montessori: An introduction to the woman, the writings, the method, and the movement. New York, NY: Plume.

- Hanna, L. G. (2012). Homeschooling education: Longitudinal study of methods, materials, and curricula. Education and Urban Society, 44(5), 609–631. doi:10.1177/0013124511404886

- Isenberg, E. J. (2007). What have we learned about homeschooling? Peabody Journal of Education, 82(2–3), 387–409. doi:10.1080/01619560701312996

- Kaseman, L., & Kaseman, S. (2002). Let’s stop aiding and abetting academicians’ folly. Home Education Magazine, 24–27.

- Kraftl, P. (2013). Towards geographies of ‘alternative’education: A case study of UK home schooling families. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 38(3), 436–450. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2012.00536.x

- Kunzman, R., & Gaither, M. (2020). Homeschooling: An updated comprehensive survey of the research. Other Education-the Journal of Educational Alternatives, 9(1), 253–336. Retrieved January 21, 2022. https://www.othereducation.org/index.php/OE/article/view/259

- Lines, P. M. (1999). Homeschoolers: Estimating numbers and growth. Washington DC: National Institute on Student Achievement, Curriculum, and Assessment Office of Educational Research and Improvement, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved September 3, 2018. http://library.stmarytx.edu/acadlib/edocs/homeschoolers.pdf

- Lines, P. M. (2000). When home schoolers go to school: A partnership between families and schools. Peabody Journal of Education, 75(1–2), 159–186. doi:10.1080/0161956X.2000.9681940

- McPhee, C., Bielick, S., Masterton, M., Flores, L., Parmer, R., Amchin, S., and McGowan, H., National Center for Education Statistics (ED), US Census Bureau, & American Institutes for Research. 2015. National household education surveys program of 2012: Data file user’s manual. parent and family involvement in education survey. early childhood program participation survey. NCES 2015-030. National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved September 3, 2018, https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2017/2017102.pdf.

- McQuiggan, M., & Megra, M. (2017). Parent and family involvement in education: Results from the national household education surveys program of 2016. First look. NCES 2017-102. National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved September 3, 2018. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED575972

- Morrison, K. A. (2007). Unschooling: Homeschools can provide the freedom to learn. Encounter: Education for Meaning and Social Justice, 20(2), 42–49.

- Neuman, A., & Guterman, O. (2017). Structured and unstructured homeschooling: A proposal for broadening the taxonomy. Cambridge Journal of Education, 47(3), 355–371. doi:10.1080/0305764X.2016.1174190

- Nordland, C. (2013). Waldorf education: Breathing creativity. Art Education, 66(2), 13–19. doi:10.1080/00043125.2013.11519211

- Pell, B. G. (2018). At home with technology: Home educators’ perspectives on teaching with technology [ Doctoral dissertation, University of Kansas]. Retrieved January 28, 2022. https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/bitstream/handle/1808/28026/Pell_ku_0099D_16266_DATA_1.pdf?sequence=1

- Perrin, C. A. (2004). An introduction to classical education: A guide for parents. Camp Hill, PA: Classical Academic Press.

- Shafer, S. (2007). Education is an atmosphere, a discipline, a life: Charlotte Mason’s three-pronged approach to education. Stone Mountain, GA: Simply Charlotte Mason, LLC. Retrieved September 3, 2018. https://simplycharlottemason.com/blog/education-is-an-atmosphere/

- Snyder, T. D., de Brey, C., & Dillow, S. A. (2019). Digest of education statistics 2018 (NCES 2020-009). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved January 21, 2022, Washington, DC. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED601992.pdf

- Sssenkusu, P. M., Ssempala, C., & Mitana, J. M. V. (2022). Shifting boundaries for parents in school engagement at the wake of Covid-19. American Journal of Educational Research, 10(1), 65–72. doi:10.12691/education-10-1-7

- Stevens, M. (2001). Kingdom of children: Culture and controversy in the homeschooling movement. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Taylor-Hough, D. (2010). Are all homeschooling methods created equal? Online Submission. Retrieved September 3, 2018. https://charlottemasoneducation.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/research-brochure3.pdf

- Van Galen, J. (1991). Ideologues and pedagogues: Parents who teach their children at home. In J. van Galen & M. A. Pitman (Eds.), Home schooling: Political, historical, and pedagogical perspectives (pp. 63–76). Ablex.