ABSTRACT

This paper investigates how the use of horse and bull iconography in Occitan and Provençal Catholic cemeteries facilitates the expression of a more-than-human regional identity and, thereby, challenges the boundaries that separate humans from the nonhuman world. The presence of nonhumans in the way humans process and understand death across faiths and cultures is often explained by the fact that humans, as they deal with death, need to make sense of it by reaffirming the singularity of human life, in opposition to that of other beings. Relegating the use of animals in death rituals as a pagan practice associated with idolatry and metempsychosis, Western Christianism has largely banished animals and animal iconography from human deathscapes. However, research in 22 Catholic village cemeteries around the Camargue region indicates that, in this part of France today, animals – especially bulls and horses – are included in the religious and social practice of death. At first glance, the use of this symbolism in the Camargue region and its vicinity seems to subvert the Christian condemnation of animal imagery. Upon closer examination, however, rather than challenging Christian norms, the use of animal imagery merges with Christian signs, indicating that local cemeteries are spaces where humans can express both religious affiliation and regional spiritualism simultaneously. Moreover, by evoking narratives of more-than-human osmosis promoted by the Félibrige literature, this imagery also effaces the boundaries that separate humans from animals and the environment. Therefore, the use of horse and bull iconography in those cemeteries not only blurs the conceptual boundaries between Catholic faith and fé biou (the “religion of the bull” to which the horse also participates) but also between humans and the nonhuman world.

The entanglements between humans and nonhumans in death have attracted tremendous attention in many academic fields, not least in anthropology, where death and the use of nonhuman animals (henceforth animals) in human death rituals and in sacrifices have been a subject of choice since the early stages of the discipline (Bataille, Citation1988; De Heusch & O’Brien, Citation1985; Evans-Pritchard, Citation1954; Gennep et al., Citation2019; Govindrajan, Citation2015; Hubert & Mauss, Citation1981; Lynch, Citation1988; Mauss et al., Citation2009; Turner, Citation1995). The omnipresence of animals in the way humans have processed and understood death across time and space is often explained by the fact that humans, as they deal with death, need to make sense of it by reaffirming the singularity of human life, in opposition to that of other beings. The urge to reinforce human uniqueness in both life and death, Serpell suggests (Citation2005), has its roots in the universal need to come to terms with an ancient psychological struggle that consists in reconciling the killing of animals for food and their incorporation within social and family circles. This, Serpell continues, is often done through the marshalling of religious narratives that promote conceptual and physical boundaries between human and nonhuman lives.

Ever since its early stages, Western Christianism, by banishing the presence of animals in human places of death and constructing the use of animals and animal images in religious rites as a scandalous practice associated with metempsychosis and idolatry, has largely served that purpose (Baratay, Citation2001, Citation2015). In France and elsewhere, this was further reinforced by the Augustinian, Scholastic (Thomist), and Cartesian traditions inherited from Aristotle, justifying a speciesist separation in death, on the basis of a belief in the dissimilarity between different (Aristotelean) categories of life (hexis, physis, psyche, and logos), leading to the construction of conceptual boundaries that separate life forms into objects, plants, animals, and humans (Couloubaritsis, Citation2000) and a fundamental difference between corporeal and spiritual souls (Baratay, Citation1995; Singer, Citation1995). These boundaries between life forms are still dominant today in many Euro-American and naturalist societies influenced by these Aristotelian categorizations (see also Descola, Citation2014). As some have noted, however (Baratay, Citation1995, Citation2011, Citation2015; Brisebarre, Citation1998, Citation2003; Gaillemin, Citation2009; Kete, Citation1995; Schmitt, Citation2004), throughout the history of Western Christianism and increasingly so from the sixteenth century onwards, there have been numerous attempts to renegotiate these boundaries and challenge the strict religious separation between humans and animals in human deathscapes. In France, these attempts have mainly taken the form of using human death rites on individual companion animals to reward the friendship and loyalty they demonstrated toward humans in their lifetime with a participation to the afterlife (Baratay, Citation2008; Kete, Citation1995). In any case, these practices have been largely marginalized by social taboos, religious doctrine, and legal restrictions, which reinforce both conceptual and physical boundaries between humans and animals in traditional human deathscapes in most parts of the French territory. Today, by law, animals in France are prohibited from being buried in human cemeteries (Agence technique départementale (ATD) des Bouches-dur-Rhônes, Citation2019), and visitors are reminded at the entrance of these cemeteries that bringing live animals (presumably, mainly dogs) is forbidden.

However, in Occitan and Provençal Catholic cemeteries, boundaries between humans and animals are not as strictly maintained as in cemeteries in other parts of France.Footnote1 Indeed, as one wanders around Occitan and Provençal cemeteries today, it is striking to see the ubiquity of both industrially made animal symbolismFootnote2 and original, personalized representations of animals displayed on human tombs, family vaults, and columbarium spaces. What is more, horses and bulls, traditionally associated with what was referred to as an “animal religion” and as evil forces, outnumber cats and dogs as the kinds of animals represented on these personalized artifacts, suggesting that bulls and horses play a particular role in the celebration of human life and death in religious deathscapes in this part of France.

In this paper, I investigate how the use of horse and bull iconography in these Catholic cemeteries facilitates the expression of a more-than-human regional identity and, thereby, challenges a series of boundaries that separate humans from the nonhuman world. What more-than-human narratives are mobilized in these deathscapes? What is the nature of the human–bull–horse relation in this part of the world, and why is it so significant to local populations that they choose it to represent to speak of their dead in traditional cemeteries? What is referred to as a bull religion (fé biou) in the region; how did it emerge, and how does it sit with the Christian faith in traditional cemeteries? What other boundaries may be blurred by the expression of this regional more-than-human spirituality in Catholic cemeteries? To investigate these questions, I first show how horses and bulls have (re)surfaced as spiritual symbols in the region, and, through an analysis of the more-than-human iconography observable in Catholic cemeteries in the area, I explore how local populations, today, speak of their connections to these specific animals beyond the grave, through imageries and narratives that blur conceptual and physical boundaries between humans and the nonhuman world. I then investigate how the stigmatization of the use of animals in human death rites emerged in early Western Christianity as a way to mark a clear separation between pagan and Christian religious forms. In particular, I look into the Church’s construction of the bull as the symbol of a threatening “animal religion.” It will then be argued that, in the Camargue, bull symbolism is not meant as a direct challenge to this traditional Christian stance and, instead, allows the expression of a simultaneous and unproblematic attachment to both the Christian faith and the “fé biou” (the bull religion). Finally, through a particular focus on the popular courses camarguaises, I will explore how some of the iconography observable at these cemeteries also speaks of a shared essence between bulls and humans in the region. The perspective of the bulls in the courses camarguaises will also be explored.

Methods

As will be shown in this paper, the iconographic expression of the communion between humans and (certain) nonhumans is not unusual in Occitanie and Provence deathscapes. To reveal the nature of the iconography in question and understand why it has flourished in traditional Christian deathscapes in this part of France in spite of religious taboos, I have recorded the display of original, personalized artifacts representing horses and bulls in 22 cemeteries all located in the Camargue region between Arles, Avignon, Nîmes and Salon-de-Provence. In particular, I have looked for how bulls, horses, and humans are represented in relation to one another; how much space they occupy compared with other artifacts, images, or messages on each grave; what symbols are associated with each animal (regional symbolism, cultural references); and how they are made to interact with more traditional Christian imagery.

The cemeteries I focused on were located in Aureille, Beaucaire (ancien cimetière), Beaucaire (nouveau cimetière), Châteaurenard, Eygalières, Eyguières, Eyragues, Fontvieille, Graveson, Maillane, Maussane-les-Alpilles, Mouriès (ancien cimetière), Mouriès (nouveau cimetière), Nîmes (cimetière catholique), Noves, Paradou, Saint-Etienne-du-Grès, Saint-Martin-de-Crau, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, Tarascon (ancien cimetière), Tarascon (nouveau cimetière), and Verquières. Each cemetery was home to between a few dozen to several hundreds, or several thousands of family vaults, individual tombs, and columbarium spaces. On each grave, especially on more recent ones, though not exclusively so, one could find up to 40 artifacts. Exact numbers are difficult to assert with certainty as no official census has been conducted and because each person I consulted, either at the local councils or directly at the cemeteries, gave me different figures; however, according to my own estimation across all 22 cemeteries, there were a total of between 7,000 and 8,000 graves (tombs, family vaults, and columbarium spaces). At each cemetery, I kept track of the number of graves that had at least one artifact (including personalized tombstones) that featured nonhuman animals, and the number of these artifacts that were “personalized,” here understood as objects that looked originally created (such as painted tiles, sculptures, engravings, etc.) or modified from their standardized production with, for instance, the addition of a photo, or with a photo montage mounted on a standardized plaque. I found 231 personalized artifacts featuring animals across 22 cemeteries, which amounts to more than 10 personalized artifacts at each site. This is a very high number compared with cemeteries I studied in other parts of France, where I could count, on average, 1.5 personalized artifacts representing a nonhuman animal at each cemetery. Moreover, the cemeteries I studied in other parts of France counted more than 500 graves on average, so only 0.3% of the total number of graves featured such a personalized artifact, making it a rare occurrence there. In contrast, the sample of cemeteries studied as part of this research in the Camargue region counted an average of about 340 graves, so more than 3% of all graves featured personalized artifacts representing nonhuman animals, which makes these artifacts 10 times more common in this area than they are in the other parts of France I visited. Out of these 231 artifacts, all dating from 1931 to 2022 (this compares with the other graves in the cemeteries, dating from as early as 1839 to the present day, which do not feature any animal iconography), it was horses and bulls that were most commonly represented (29% and 17%, respectively), followed by companion animals (12% representing cats, and 8% dogs), and animals involved in hunting or fishing (6% featuring hunting dogs, (dead/alive) partridges, quails, fish, boars, etc.). The remaining 28% comprised animals associated with other regional symbols (flamingos, cicadas, etc.), traditional religious symbols (birds flying to heaven, a flock of sheep alongside a shepherd [often resembling Jesus Christ], etc.), and other animal kinds whose significance for the deceased or the living was more difficult to infer and/or categorize (owls, bears, eagles, donkeys, hedgehogs, gorillas, wolves, dolphins, etc.).

The predominance of bulls and horses in these artifacts is hardly surprising considering how both species take center stage in a series of regional identity narratives, which have emerged in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. But it is significant when considered within the traditional Christian perspective of species separation in French deathscapes and also given the negative symbolism associated with the bull and with idolatry in general (see analysis section).

Results

In general terms, the occurrence of horse and bull representation in these cemeteries seemed to increase particularly in artifacts and graves dating back to the 1960s onwards. However, the vast majority (about 70%) of all personalized artifacts recorded could be dated back to the 1980s–1990s or later. Development and access to digital technologies could explain this increase in the number of personalized artifacts produced, as the same increase was also observable among similar artifacts dating back to the same period which did not feature animals. It could also be that people naturally tend to be less assiduous with visiting and populating the graves of loved ones as years go by, as those who have known the deceased pass away in their turn, and as tombs are replaced by new ones. That said, the changes in frequency of these personalized artifacts in time could also indicate, as Baratay (Citation2015) has suggested, that as France became increasingly secular, people have tended to let go of certain religious taboos, including the imperative of species separation in human deathscapes. In that perspective, the increase in the number of such artifacts from the 1980s–1990s onwards could also reflect a growing tendency to embrace human–animal continuity more overtly. However accurate this may be, this social change alone could not explain why the number of artifacts using animal iconography was ten times higher in this particular region than in other parts of France – let alone that, in the case explored here, the animals in question were mainly bulls and horses, two species who play a key role in more-than-human regional narratives.

That the number of artifacts steadily increases between the 1960s and the late 1980s can also be explained by the growing symbolization of regional practices at the time. As Pelosse indicates (Citation1990), it was indeed between the 1960s and the late 1980s that symbolic versions of traditional “tauromachic” (bullfighting) activities (see, for instance, the abrivado, later in this article) were integrated as part of local annual celebrations.Footnote3 Moreover, the turn of the 1980s also coincided with the creation by the Ministry of Culture of an Ethnological Heritage mission, which promoted the idea that the performative construction of cultural identities should also be understood as part of national and regional heritage. As a result, everywhere in France, intangible cultural elements such as regional know-how and symbolic versions of traditional activities were increasingly celebrated as ethnological, vernacular heritage. In the Camargue, this translated into an increasing infatuation for symbolic tauromachic activities during local fêtes (Fournier, Citation2003). The performative elements of these celebrations (for instance, that young men and women surprise and try to distract the bulls during the abrivado, see later in this article) also meant that not only aficionados, but all members of the local community were encouraged to take part in the celebration of regional heritage. The development of a wider attachment to these activities among local communities at the time could account for the significant increase during the 1980s–1990s in commemorative imagery at local cemeteries depicting the deceased engaging in such celebrations.

During this research, cemeteries that had high numbers of animal (and especially horse and bull) iconography were all located in the Camargue region and its vicinity. This is significant because of the Camargue’s distinctive meaning in regional narratives as a land without clear territorial boundaries, and a place where all living entities emerge from and merge with their environment. These narratives about more-than-human osmosis are to be understood in the context of the (re)invention of what the Marquis de Baroncelli-Javon (1869–1943) called the “pays taurin” (“bullscape”) in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, an imagined nation which he argued had somehow emanated from the Camargue land, overlapping on what is known today as both the PACA and Occitanie (especially the Languedoc territory) regions. The invention of the pays taurin and the more-than-human narrative about the Camargue by Baroncelli-Javon emerged in the context of a quarrel between Paris, the centralized power, and distinctive regions of France, especially those at the outskirts of the nation state, including not only Provence and Occitanie, but also the Pays Basque or Brittany. Galvanized by the need for social order and control as a result of industrial revolution and political instability (Zaretsky, Citation2004, p. 4), the birth of the Second Republic (1848) in France led Paris to invent and promote a unified “Frenchness across the territory” in the hopes to both modernize and centralize France. The pressures to centralize France intensified during the Third Republic and well into the Belle époque and constructed a certain kind of Frenchness which characterizes how we understand it to be up to this day. This “Frenchness” was secular, introduced compulsory schooling and military service, Republican holidays and traditions (Zaretsky, Citation2004), and followed the Jacobin ideal of an indivisible community.

At the same time, regional populations reacting against the imposition of a univocal (Republican) understanding of “Frenchness” emerged to (re)invent traditions as part of a local nationalist or regionalist discourse. As Hobsbawm and Ranger (Citation2012) highlighted, that moment in time was also particularly propitious to the development of identity narratives because, especially in the last decades of the nineteenth century, increased immigration from central Europe and from the Mediterranean ignited a desire for populations to “awake” to their distinctive past. It is in that context that the Baroncelli-Javon and other members of the Félibrige, a movement dedicated to the promotion of the Occitan and Provençal heritage, mobilized a series of narratives that grounded the Camargue in (allegedly) age-old traditions and practices that meshed humans, animals (especially bulls and horses), and the land, blurring boundaries between the human and the nonhuman world. Zaretsky’s work (Citation2004) indicates that, while there may be a culturally distinct region in the south of France as opposed to other regions, in the case of Occitanie and Provence, this distinctive past as a nation, never really existed. He argues that the alleged tradition rooted in “times immemorial” was, as we shall see later in this article, largely constructed by poets and other members of the Félibrige movement through the use of horse and bull symbolism, which is reflected at local cemeteries.

The Horse and the Gardian as Symbols of More-Than-Human Osmosis

At local cemeteries, the figure of the horse often featured on personalized plaques. In line with regional narratives, it often symbolized the blurring of boundaries between the Camargue people and their land. The Camargue horse (referred to in French as “Le Camargue”) generally refers to small, often white or gray saddle horses. As mentioned previously, thanks to Baroncelli-Javon blurring the lines between fiction and reality, the origins of the Camargue horse and the origin of its domestication remain relatively unknown, not to say mysterious, which gives currency to the representation of the Camargue as a “strange” land. Members of the Félibrige referred to the Camargue horse as one of the oldest horse breeds in the world, left roaming free since Roman Antiquity, occasionally used for agricultural purposes, but first and foremost as a regional symbol (Aubert, Citation1932). While others remained skeptical about any clear evidence of its presence before the sixteenth century (Allix, Citation1930; Musset, Citation1916), Camargue horses are traditionally referred to as semi-domesticated or “semi-free” horses, used in the shelling of wheat until the introduction of mechanical threshers (Musset, Citation1916). The story of preservation of the Camargue horse also participates in the success story of the regionalist preservation, constructing Baroncelli-Javon as a hero on the frontline. The story goes that the Camargue horse also served in the army but that, since the Great War, because the metropolitan cavalry had lost much to the benefit of motorized units, ranchers could no longer sell their horses to them; this is why their use for steering cattle as part of the manade, a herd of bulls and/or horses, became a more profitable way of using them (Musset, Citation1916). At the start of the twentieth century, development work in the Camargue region, such as the desalination of the salty land without vegetation, the irrigation with water from the Rhône, as well as the planting of vines required more powerful draft horses than the Camargue ones, which thus seemed doomed to disappear.

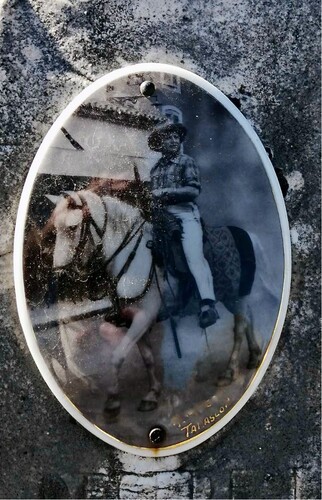

It is in this context that, in the Camargue region, Baroncelli-Javon is often portrayed (Musset, Citation1916; and many others) as a local savior who created the Nacioun gardiano in 1909 (or “Gardian Nation”), maintaining and promoting the traditional image of the Camargue horse led by the gardians (riders) as symbols of freedom, more-than-human osmosis and mastery over the elements, in the hopes of raising awareness among the local population to the role the Camargue horses played in their regional identity formation. The Camargue horse was portrayed as the loyal companion of the bull and the gardian, a dashing horse-rider, giving order to the horse-bull-human trio (see next sections). As Zaretsky notes (Citation2004, pp. 100–105), the Marquis attempted to recreate the purebred Camargue man, not through eugenics, but through actual folkloric haute couture: Baroncelli-Javon constructed the traditional gardian garment (apparently, on the basis of his own personal taste in clothes) and established a sartorial code for them, also influenced by the imageries of “Indians” and horse-riders he had seen in Buffalo Bill and other Wild West shows that were exported to the Camargue at the time. Judging by the use of personalized artifacts in local cemeteries, the infatuation for this figure of the gardian as a symbol of regional pride was widespread and can be traced back at least to the 1960s in the region, as testified by this 1965 photograph of a deceased portrayed as a gardian and referred to as a manadier (the owner of a manade) in Tarascon ().

Figure 1. A photograph mounted on a 1965 artifact representing the deceased as a gardian on his horse. An epitaph mentions the deceased’s profession as “manadier.” Photo copyright author.

Baroncelli-Javon’s enterprise to construct an aesthetic of the Camargue horse and the horse rider as symbols of regional identity received further impetus thanks to the success of the 1953 film Crin-Blanc, which featured images of young men on galloping horses in the Camargue as expressions of osmosis, escapism, elusiveness, and wildness. The promotion of the figure of the young gardian in Crin-blanc cemented the symbol of the horse and his rider merging with the elements and the landscape as a strong regional icon and sparked a huge touristic interest in the region, which has remained steady ever since. Today, Camargue horses are widely used for tourism and leisure activities, especially for equestrian rides through the Camargue land.

Both the imagery of the gardian on his horse, galloping across fields or riding in the sea (as is observable in ), as well as the language used to describe the deceased riding their horse as a symbol of eternal osmosis (see , where death is described as “an ultimate horse ride through time”) were common at local cemeteries. Put together, the images and epitaphs on personalized plaques that featured the gardian riding a horse often blurred boundaries between the human and nonhuman worlds. In Beaucaire, Tarascon, and Maussane-les-Alpilles, some plaques featured gardians riding horses galloping in the Camargue with an epitaph stating: “You are now the Camargue (la Camargue),” indicating the deceased had merged with the land; “Enjoy your eternal ride in the Camargue;” “Forever in the Camargue;” or even more explicitly: “You are now at one with the Camargue” (Tu ne fais plus qu’un avec la Camargue).

Figure 2. Individual grave of a young man represented riding a Camargue horse in two photos. The photo on the left is mounted on a plaque with an inscription which reads: “My gardian. Life is a journey. Death a new life. Your mother, who loves you. The sun has set before the end of the day. Your nieces, in admiration.” The plaque also features the Camargue cross, half-hidden by other artifacts. Photo copyright author.

Figure 3. Grave of a young man. The young man is portrayed next to a horse both on the main tombstone and on a separate plaque. Another five horse representations feature on the tomb. The epitaph reads: “Despite all our love, we have not managed to prevent you from going on an ultimate horse ride through time. We love you infinitely. Mom and Dad.” Photo copyright author.

The occurrence of the horse-riding iconography as a symbol of the Camargue people merging with the land, blurring the boundaries that separate humans from the nonhuman world, cannot be attributed to the success of the Crin-blanc movie alone. While the film’s popularity has certainly played a role in cementing that image, the symbolism presented in the film reflects one which is also ubiquitous in literary texts produced by members of the Félibrige. In his anthropological study of the Camargue people, Martel analyzed a dozen literary works about the Camargue, among which feature strong defenders of Provençal identity Mistral and Daudet, as well as carried out a series of interviews with people of the region (Citation1993). He highlighted that the vocabulary used by both authors and participants mirrored each other and revealed a number of very precise indicators, markers, and stereotypes in the expression/construction of the Camargue identity, where humans, animals, and the land were referred to in the same way (Martel, Citation1993, p. 63). In both the Félibrige literature and his interviews, the Camargue horse, people, and land were often said, for instance, to be eternal, mythical, strange, apart, wild, free, proud, strong, and untamed, united by a very strong “essential” yet spiritual bond, in a land where boundaries disappear, as humans and animals exist side by side “since times immemorial” (Martel, Citation1993, pp. 67–68). The use of an iconography at these cemeteries that evoke the idea that the boundaries separating people from the Camargue eventually vanish, as animals, humans, and horses, all merge in eternity, therefore mirrors the narratives propagated by Baroncelli-Javon and other members of the Félibrige movement, narratives which are still very much alive in local descriptions of the region (Saumade, Citation1994).

More often than not, this regional imagery representing the human–horse osmosis also featured the bull. In the region, the symbols of the gardian, the bull, and his Camargue horse are inevitably linked. Camargue horses are often reported as sharing bonds of love with and show loyalty to their humans, and to the bulls they help tend to (). Today, these horses are often rented for festivals across Languedoc and Provence, where they are mobilized to display those qualities of loyalty, as they are ridden by gardians, wandering the streets of villages during the “fêtes votives” (patronal festivals), touristic displays taking place during the summer. The horses are used by the gardians to keep the bulls safe during the courses camarguaises (see later in this article for an overview of what these courses entail).

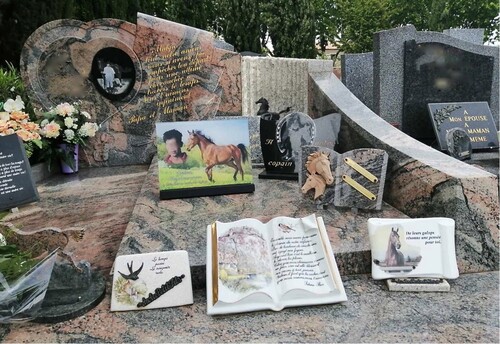

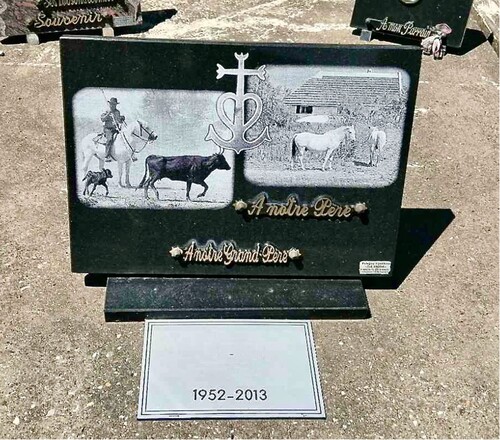

Figure 4. Personalized plaque representing the deceased in two photographs jointed by a Camargue cross: one represents the deceased on a Camargue horse tending to the bulls, the second, a couple of Camargue horses. The plaque reads “To our father. To our grandfather.” Photo copyright author.

Moreover, as Martel also shows in his study (Citation1993), bulls, real or not, are also referred to in both literary texts and lay conversation in divine terms. They are described as “gods” or as following “a divine intervention,” uniting humans, horses, and bulls in eternity (Martel, Citation1993, see also Pastoureau (Citation2020) and Saumade (Citation1994)). To the point, Martel adds, that it is not uncommon to hear people in the region strongly identify with legendary half-human/half-horse or half-human/half-bull creatures, such as centaurs or the famous la Bestio, and see them as ancestors. At first glance, these narratives of more-than-human divinity and filiality are a direct challenge to the Christian faith, especially in the case of the bull, who has been constructed by the Church as a symbol of a threatening animal religion since the early stages of Western Christianism. However, as I will show in the next sections of this article, both faiths successfully coexist at the Catholic cemeteries I studied.

The Bull as “Ancestor” – Blurring the Boundaries Between fé biou and Christian Faith

As the work of renowned French animal historian Michel Pastoureau suggests (Citation2020), in the early stages of Western Christianity, the bull was devalued as a result of the importance it had received in the (largely pagan) belief systems that Christianity tried to overtake. Indeed, in various civilizations from the late Paleolithic era to the late Antiquity in that part of the world and elsewhere, the bull was positioned as a manifestation of a godly, divine creature (Pastoureau, Citation2020). Most people from Anatolia and from the Mediterranean Near East, at one time or another, projected in the bull a godly symbol of power and fertility. Phoenicians even devoted the first letter of their alphabet, of which our Latin “A” is derived, to a bull: it is apparently a bull’s head turned upside down (Pastoureau, Citation2020, p. 66). In Europe, mythological stories originating from protohistorical tales and appropriated by Greek mythology staging heroic bulls were common. Numerous literary texts which were at the foundation of European culture, including Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, Virgil’s Eneida, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the Poetic Edda, or The Cattle Raid of Cooley, all feature stories of fantastic and awesome bulls, portrayed as powerful hybrid beings (half-animal, half-god, like the minotaur), some seemingly immortal (the Cretan Bull, one of Heracles’ 12 labors, for example). In Ancient Rome, too, bulls were seen as particularly important and potent creatures as many were sacrificed to different deities to attract fertility, power, and victory in warfare.Footnote4 These sacrifices were mainly made to Mars who, according to Pastoureau (Citation2020, p. 67), might have himself been, in its primitive form, a bull-god.

However, as Christianity took over, rituals and sacrifices using bulls as powerful symbols were quickly prohibited. On the one hand, because of the prominent role the bull played in these rituals and sacrifices, associating it with negative and evil representations became a particularly effective instrument of religious and moral detachment (Pastoureau, Citation2020, p. 73). Constructing the bull as a potential manifestation of the devil thus allowed Christianism to frame paganism as immoral (Baratay, Citation2001). On the other hand, animal rituals, animal idolatry, and the offering of the blood of any animal to a god were judged abominable. The belief that animals could be the image of god, as in the episode of the golden calf in the Hebraic Bible, where groups were punished for worshipping the golden effigy of a bull deity (Pastoureau, Citation2020), that they played a role in sending off the dead to the afterlife, and the belief in metempsychosis were, too, vehemently rejected as the undesirable traits of an “animal religion” (Baratay, Citation2015), a scandalous practice that had to disappear.Footnote5

While the bull was framed as the evil, pagan animal par excellence, from the sixth century onwards, because of the important role cattle played in everyday life, Christianism also produced more positive associations with bovids (Pastoureau, Citation2020). The ox, in particular, became the symbol of a docile, kind, and noble animal, as evidenced by its ubiquitous representation in many medieval paintings where, often appearing alongside a donkey, it was portrayed looking over the birth of Christ. However, throughout the Middle Ages, the bull, the ox’s “wild” (as Pastoureau underlines (Citation2020), this generally meant “uncastrated”) counterpart, remained largely demonized by the Church, as testified by its description and representation in English and French bestiaries of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries as a hypersexualized and diabolical beast (Pastoureau, Citation2020). From the Renaissance onwards, thanks to the revisiting of the classic literary texts from Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome featuring bulls in a heroic light, the bull was, in part, rehabilitated as a positive symbol of bravery, strength, fertility, and courage; yet negative associations prevailed nonetheless.Footnote6

As specialists of the region, Carretero (Citation1987) and Saumade (Citation1994), have highlighted, we know very little if anything about the exact role, use, and significance of bovines in the Camargue up until the sixteenth century (Saumade, Citation1994, p. 224). What we know, from the likes of Duret (in Pelosse, Citation1990), for instance, is that there is evidence of tauromachic practices in the region in the sixteenth century which has continued yet fluctuated throughout the various regimes that have led up to modern-day France. There is also some uncertainty as to what triggered a resurging interest in tauromachic activities in the middle of the nineteenth century. Up until that point, these activities had been largely discredited, especially by the elite, as a regional eccentricity. Pelosse (Citation1990) suggests that this resurging infatuation is to be understood through the cultural influence of the Spanish corrida coming at a time of growing regionalisms and nationalisms, leading the local French elites to redefine the Camargue tauromachic practice as part of regional high culture, distinct from its counterparts in other parts of the world, giving the Camargue bull an extra-agricultural raison d’être. In particular, Picon (Citation1988, p. 116) suggests that the elevation of the Camargue bull as a symbol of high culture could have also been influenced by Napoléon III’s wife, Eugénie de Montijo, who, from Hispanic origin yet attached to her French identity, wanted to develop a national tauromachic art in France. Whatever the exact origin, regional interest in tauromachic activities and the Camargue bull as a regional symbol gained traction in the middle of the nineteenth century. Pelosse (Citation1990) reports that the number of bulls reared in the region went from 550 bulls in 1830 to more than 3,000 thirty years later. Therefore, as Baroncelli-Javon and other members of the Félibrige, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, started producing narratives of more-than-human continuity wherein the bull played a central part as an alleged ancestor of the Camargue people, the Camargue people were already receptive to the bull as a symbol of the region and of their own identity (Saumade, Citation1994, p. 10). That the bull was at the center of continuous local practices at least from the sixteenth century onwards, then was elevated as a regional emblem in the middle of the nineteenth century, and reified as an ancestor by the Félibrige, facilitated its unproblematic integration into everyday life and discontinued its traditional demonization by the Christian Church. As Catholicism remained the dominant faith practiced in Camargue, the use of the bull as a symbol of individual identity, up to this day at the cemeteries, has therefore more to do with its regional significance than with its potential challenge of Christian values. At the cemeteries, as we shall see later in this article, this has translated into the use of a material and visual culture that blurs both Christian faith and fé biou unproblematically.

Yet, this compatibility of both the Christian faith and the fé biou did not go smoothly with the centralized powers. For the central government, this attachment to bull-related practices represented an obstacle to the modernization of France as a unified nation. For the French Catholic church, the issue lay less with the pagan symbolism associated with the bull, than with the cruel tormenting of the bulls taking place during tauromachic activities (see discussion), which was in stark contrast with the modern empathetic values that both Paris and the Church were keen to promote at the time (see Halttunen Citation1995; Hume et al., Citation1978; Kete, Citation1995; Skabelund, Citation2011, and others for how empathy toward human and nonhuman life forms became part of modernist ideologies from the seventeenth century onwards in England, France, Japan, and elsewhere). As a result, in 1863, “tauromachie” (bullfighting) in Provence and Occitanie was vehemently condemned by both the central government and the Church (e.g., by bishop of Nîmes, Mgr. Plantier in 1863) as a barbaric blood sport and was abolished in most parts of France (Baratay, Citation2008).

However, infatuation for the maintaining of one particular tauromachic form, the course camarguaise (see next section), as part of a Provençal and Occitan traditional heritage continued regardless, thanks to members of the local elite who, in the middle of the nineteenth century, elevated the course camarguaise as a regional tradition in reaction to the government’s effort to centralize and unify French society. This was followed, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, by the invention and promotion by the Félibrige movement of narratives wherein the Camargue bull appeared as the mythical ancestor of local populations. More precisely, in the early decades of the twentieth century, the bull became an even more prominent spiritual symbol in the Camargue, thanks to the effort of the Marquis de Baroncelli-Javon, who endeavored to (re)create the Camargue bull breed, as he did with the Camargue horse, and, thereby, restore the purity and nobility of the Camargue people, under threat of assimilation by the centralized powers of France, as explained earlier in this paper. To do this, Baroncelli-Javon mobilized unfounded scientific and historical evidence (Zaretsky, Citation2004, pp. 50–51, see also the work of Émile Ripert on Baroncelli-Javon), which nonetheless gained much traction because of how much currency questions of identity and race had in Europe at the time. In part thanks to his famous 1924 poem Lo Biòu (the bull), Baroncelli-Javon managed to construct the Camargue bull breed as one which had been there “since times immemorial,” a sort of “ancestor” of the people in the region, even though there is very little documentation on the use of the bull in the Camargue region beyond the sixteenth century (Saumade, Citation1994). In spite of tangible evidence confirming this, the promotion and preservation of the Camargue bull as a unique and “pure” breed became a matter of regional pride and identity affirmation. The breed was said to be born from a uniquely harsh environment in the region, one that kept outsiders away, conveniently serving the common narrative of nature-cultural uniqueness to reinforce nationalist sentiment. The faith in the bull as a symbol of the region, an ancestor that emerged from the land, became so popular among local populations that it even took on local Catholic commoners and aristocrats who, galvanized by pressures from the centralized powers, embraced both bull breeding and regional bullfighting (courses camarguaises) as important heritage to preserve (Zaretsky, Citation2004).

It is important to note that, today, the merging of both faiths is not experienced as a direct challenge to Christian values by local representatives of the Church nor by cemetery guardians. Indeed, conversations with local priests and cemetery guardians further indicate that those artifacts are not perceived as a threat to Christian symbols and ideals. Both local priests and cemetery guardians I have spoken with see animal imagery as but one way among many to speak of the deceased’s personality and interests during their lifetime. A cemetery guardian told me to put the use of these symbols on the same level as the representation of other widespread activities in the region, including the belote (card game) or the pétanque (boules sport), activities that were indeed also represented at these cemeteries, though much less extensively. The few priests I interviewed spoke of “a compatibility between two separate devotions,” of a “regional faith which does not supplant the religious faith,” or “a way to speak of the complexity of life.”

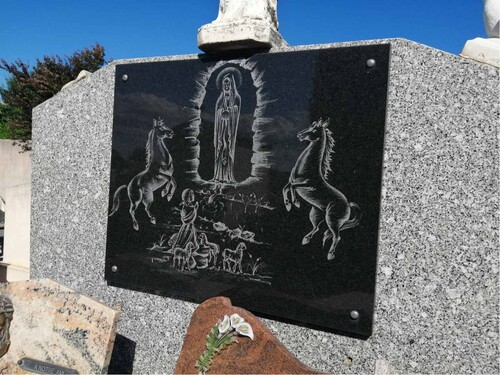

Today, bull symbolism is ubiquitous at Catholic cemeteries located in the Camargue and its vicinity. As explained earlier, the regional narratives that connect humans to bulls in the region, as well as the belief in the bull as an ancestor (fé biou), are intrinsically linked to the figure of the horse. This explains why the more-than-human regional symbolism used at the cemeteries often portrays both bulls and horses in eschatological terms, thereby integrating both animal symbols in a form of regional spirituality, compatible with the Catholic faith. For instance, in Tarascon, a scene showing a gardian leading his bulls on a horse, riding in front of flamingos flying into the sun in the background, was engraved on a tombstone with an epitaph that said “[i]n eternity.” Similarly, in Paradou, Beaucaire, and Fontvieille, numerous plaques could be found featuring either a bull or a horse with a note that said: “Beyond time,” “Immortal Camargue,” or “Eternal land.” More often than not, artifacts that featured bull and horse representations were accompanied by a note speaking directly to the deceased using a religious language that evoked the possibility of an afterlife (“Wait for me. We will be united forever,” “I will soon join you,” “See you in the afterlife”), thereby suggesting that traditional and regional eschatological symbols and more generally Catholic faith and regional spirituality are not incompatible. For instance, a grave in Saint-Martin-de-Crau showed a beautiful one-meter statue of a horse turning his back to the grave visitor in order to face a Catholic cross instead; in Beaucaire, one tombstone () features horses portrayed as being somehow struck by the apparition of the Virgin Mary, similarly to a young shepherdess, thereby suggesting that animals strongly associated with regional identity are able to appreciate Christian narratives of divine intervention, as opposed to others, like sheep, who in this design seem oblivious to the Virgin Mary.

Figure 5. Tombstone design showing two horses and a young shepherdess struck by the apparition of the Virgin Mary. Seemingly oblivious sheep also feature. Photo copyright author.

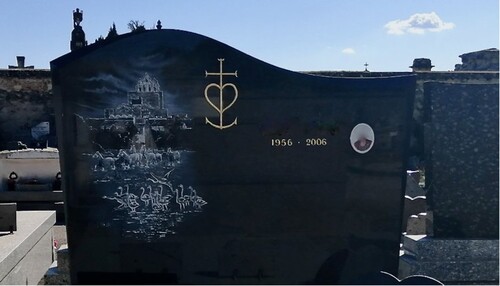

A similar blurring of both faiths was sometimes noticeable through the more straightforward imposition of a bull in front of a Catholic cross (see ) or by the replacement of the Catholic cross by a Camargue cross (also visible in , , , and ), as is the case in . This specific tombstone also featured other regional symbols (horses and flamingos) and what seemed to be the Catholic church at the Sainte-Maries-de-la-mer, a quintessential coastal town of the Camargue region, in the background. The Camargue cross is a symbol of Provençal spiritualism created in 1926 by the painter Hermann-Paul at the request of the Marquis Baroncelli-Javon to represent the “Camargue nation” (Zaretsky, Citation2004). The cross, in itself, merges both Christian and regionalist sentiments because it embodies three theological virtues (faith, hope, and charity), each associated with a different regional symbol. Respectively, these symbols are the trident of gardians, the anchor of the fishermen, and the heart of the Saintes Maries (Marie Madeleine, Marie Salomé, and Marie Jacobé), who, according to Christian tradition, came to settle in the Camargue region (Zaretsky, Citation2004).

Figure 6. Stone representing a bull’s head mounted on the family vault, next to a Christian cross. Photo copyright author.

Figure 7. Camargue cross in a Catholic cemetery (cimetière chrétien) on a tombstone where flamingos and horses are portrayed in what is likely to be the swamps near the Saintes-Maries-de-la-mer, a coastal town in the Camargue. The town’s emblematic church is portrayed in the background. Photo copyright author.

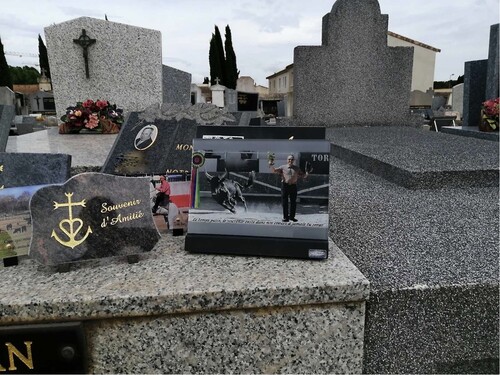

In , Christian and regional symbolism are similarly blurred. At the front of the grave, are two plaques: one dating from 1965, which features one of the family’s deceased as a gardian (photograph shown as in more detail above), the other dating from 2003, which features the photograph of a bull with the inscription “In memory of friendship, to our regretted Tarascon manadier, bull club,” suggesting that several members of the family had taken on the manadier profession over the course of nearly half a century. In this case, too, the traditional Christian cross is subverted and replaced with one which takes on a more organic/natural form. At the bottom of the cross is an inscription highlighting the deep connection that has marked the history of the family: “Family X, bull owners (propriétaries de taureaux).”

Figure 8. Family vault of “Bull owners (propriétaires de taureaux)” in Tarascon. Photo copyright author.

What is more, at these cemeteries, more-than-human iconography evoking the idea of a shared essence between humans and animals in the region was also easy to observe. As the next section will show, this was particularly conspicuous when people and bulls were portrayed displaying the same essential qualities while facing each other in the arena during the widely popular courses camarguaises.

Blurring the Boundaries Between Aficionados and the Bulls

During a course camarguaise, cocardier bulls (named after the “cocarde” which is a 5–7-centimeter red ribbon, tied with a string at the top of the bull’s forehead which the “raseteur,” the human facing the bull, is trying to retrieve) arrive in the morning by truck and are presented to the public in the streets of the city, supervised by gardians on their horses (an event called “abrivado”). The bulls are then accompanied into the arena (called the toril) by the same gardians. Then young men, the raseteurs and tourneurs (turners) enter in two lines to greet the public and the officials attending the event. They are divided into several teams of two, each composed of one raseteur and one tourneur. The latter’s purpose is to direct the bull toward a specific direction so that the raseteur can try to catch, with a hook, the attributs primés (“prime attributes” – objects attached to the bull’s forehead and horns – which, if caught, bring points and prize money to the young men). A first trumpet call indicates the arrival of the bull, whose name is announced by the local president of the courses association. The president also announces the manade from which the bull comes from, as well as which prizes and how many points are associated with whichever attribut primé. The bull carries the devise (motto) and colors of his manade. Then, a second trumpet call invites the raseteurs to start the game. The bull begins to run around the arena, while the tourneur (who is usually a former raseteur) tries to attract the attention of the bull with gestures and voice calls, in the hope to place the animal in a favorable spot for the raseteur to catch the attributs primés. At this stage, if the cocardier pursues the raseteur all the way to the barriers of the arena (known as a “coup de barrière,” see later in this article), he is greeted with music from Bizet’s opera, Carmen. The third trumpet call occurs 15 min after the second one and indicates when the bull is expected to return to the toril. The simbeu (an ox with a bell around his neck) is introduced into the arena to guide the bull out if he refuses to leave. After the bull is gone, the whole sequence is repeated with different raseteurs, tourneurs, and cocardiers. There are usually between 4 and 6 rounds at each event. Points are awarded for snatching attributs primés and contribute to the raseteur’s overall ranking in the regional championships. At the end of the day, cocardiers return to their pastures.

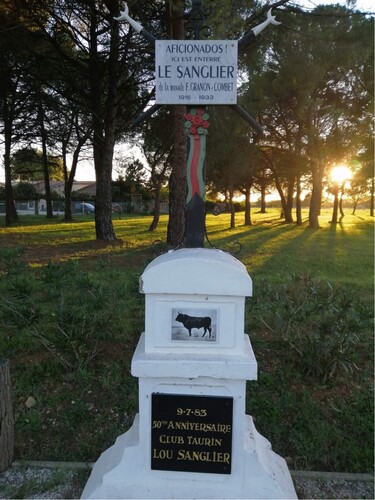

These courses camarguaises (also known as “courses à la cocarde” or simply “courses”) are widely practiced in the region on the border of Languedoc and Provence, where the Camargue and Alpilles regions lie. The terms “tauromachie” and “courses camarguaises” are often used interchangeably. A common trope one hears in the region is that, unlike the Spanish version of the activity, the courses camarguaises do not involve the killing of the bull in the arena and present the bull as the main protagonist of the game. In most cases, however, if they are not performing well, bulls end up being sent for slaughter and turned into meat, allegedly consumed with respect for the individual animal now turned into food. However, when he is combative (the two main qualities mentioned by Saumade’s participants are the bull’s meanness and his intelligence (Citation1991, Citation1995)), the bull at the center of the courses camarguaises is praised as a hero. His sacralization is therefore conditioned by his ability to perform for the human audience. Saumade also notes that the best performing cocardiers are elevated to the status of “persons” (1994, p. 139). If a cocardier has been personified in life, in death he can be the recipient of considerations that are unusual for a livestock animal. At the very least, the bull is said to go uneaten and is let to live and die “a beautiful death,” which entails being kept in the manade (as mentioned earlier, this is the farm where “manadiers” ensure the selection of what they see as “quality bulls”) or in a neighbor’s field until he dies of natural causes. Saumade also reports that some of these personified cocardiers are buried in the manadier’s home, where they were also born. In local cemeteries, these bulls are sometimes immortalized as large statues (in Lunel and Beaucaire, for instance), while others are photographed or painted and placed near their deceased humans inside traditional cemeteries, as is the case with the bull represented on the tile in . Some are even given individual graves, outside of human cemeteries. These individual graves have become public places of remembrance and appreciation for the activity, such as the grave of Le Sanglier (Boar, in French), a very famous cocardier at the crossroad of the route du Cailar and route du Delta de Camargue (see ). The connection between the cocardier and his manadier is often spoken of during their respective lifetime. It is usually the case that the manadier rents his bulls for the course and if the manadier drives a hard bargain, he is said to be “like his bulls,” Saumade tells us, echoing the virtues of meanness and intelligence used to describe a well-performing bull.Footnote7

Figure 9. Painted tile representing a cocardier, with the manade’s “devise,” the cocarde (ribbon used for the course) taking the colors of the manade, here visible at the bottom of the tile. The tile was placed next to the family columbarium. Photo copyright author.

Figure 10. Tomb of Le Sanglier. The epitaph reads: “Aficionados! Here is buried Le Sanglier of the F. Granon-Combet manade. 1916–1933.” Below is a plaque added by the Club taurin on 9-7-83 for the 50th anniversary of the death of Lou Sanglier (Provençal for Le Sanglier). The two spikes represented at the top of the tomb are gardian tridents, used to steer the bulls while riding a horse. Photo copyright author.

In cemeteries, the connection between the heroism and bravery of both the bull and the gardian is also often immortalized through the display of personalized artifacts ( and ). This could also be seen to evoke the human–bull dual participation to a cultural representation of bravery, a sort of recklessness that characterizes both humans (usually men) and bulls in the region and which can be attributed, allegedly, to the common ancestry promoted by Félibrige authors. Indeed, Zaretsky shows how the Félibrige literature was instrumental in promoting the idea of a blurred boundary between man and bull (Citation2004). For instance, Joseph Arbaud’s book, La bête du Vaccarès, recounts the imaginary tale of a gardian from the fifteenth century who meets a beastly human–bovid hybrid as he walks around the Camargue. The beast looks both frightening and fascinating, a duality which emerges from the common ancestry of “beast” and man. The land in which the beast lives is one where the boundaries between nature and culture collapse. The tale is also instrumentally presenting the land as mysterious, with blurry and unclear boundaries. For instance, as Zaretsky notes (Citation2004), it is represented as a water desert (désert d’eau), an oxymoron characteristic of the Camargue itself, where all boundaries disappear and opposites merge into each other, a land that inspires both fear and awe, terror and love, emotion and rationality, abstract and concrete, solitude and unity, illusion and reality, light and darkness, but most importantly, human and nonhuman. In this story, the bull, the Camargue land, and the gardian on his horse are all one and the same. This provides very useful clues to analyze the presence of horses and bulls in human places of death in the region, as anything that characterizes the bull, the land, and the horse also defines the regional man and woman. The alleged characteristics of the bull speak of the bravery of the people in the region, especially as they resist and defy a centralized identity, as mentioned before. With this as a backdrop, it becomes clear why, in some cases, the symbolism found in human deathscapes evokes both human and animal bravery at the same time. In the courses, the intelligence of the bull is said to be high if he manages to prevent raseteurs from catching his “prime attributes” (attributs primés, i.e., ribbons and cords placed on the horns and the body of the bull by manadiers (breeders) prior to the event), whereas the raseteurs’ prowess is conversely praised when they succeed in catching these attributes. In fact, civil society and even elected members of the local municipalities who recognize the importance of showing their support of this activity in the region place bets on the performance of both bulls and humans. While inside the arena, as mentioned above, heroism is mentioned as a quality of the bull who defies humans but also when humans flee: that is, when they manage to escape from the bull by exiting the arena at the last minute (an action known as “barrier strike” (coup de barrière)).

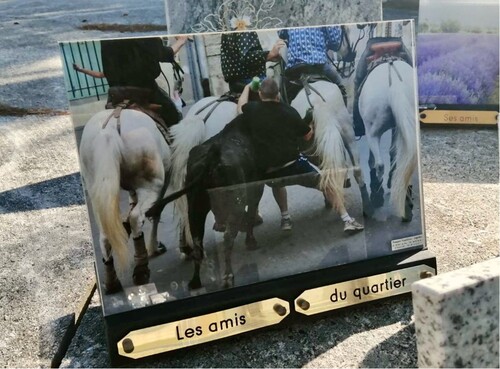

Figure 11. The deceased represented as an “atrapaïre” during an “abrivado.” The abrivado activity used to designate the driving of bulls from the pastures to the arenas under the supervision of the gardians. Nowadays, it refers to the traditional simulation of that activity which involves the release of the bulls in the closed streets of a town or village for a few hours. Before the bulls are released, young men and occasionally women, between 15 and 20 years old known as “atrapaïres” (attraper is “to catch” in French), try to make the bull escape. As they do, the atrapaïres are believed to display bravery, recklessness, and skill. The plaque reads: “Friends from the neighborhood.” Photo copyright author.

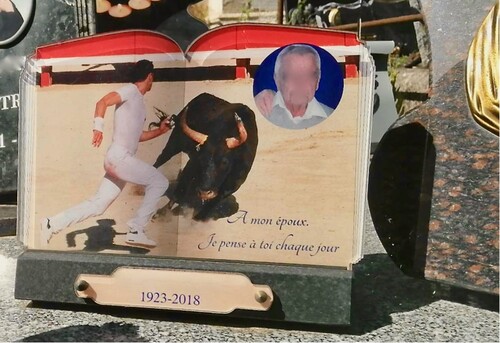

Figure 12. The deceased represented near the photo of a raseteur escaping from a charging bull in an arena as part of a “course à la cocarde.” The plaque reads: “To my husband. I think about you every day.” Photo copyright author.

In and , the raseteur seems to be successfully thwarting the bull’s aggression and intelligence, which suggests that what is immortalized inside Occitan and Provençal cemeteries (and especially in the Camargue region) is the heroism of both the cocardier and the raseteur at the same time, sometimes with photo montages showing the manadier amidst the arena as the bull is rushing toward an invisible target, as is the case in . These representations blur the human–animal boundary. The deceased is portrayed in the same terms as the bull. The meaner and more intelligent the bull, the more courageous and reckless the raseteur. Both are portrayed showing great strength and bravery, and it is this continuity between the bull and the young man which is celebrated. What is more, merging human and animal in this fashion reinforces the expression of a regional belief in a shared essence between local bull and human populations. Arguably, what is represented here is not human exceptionalism but the continuity between human and animal.

Figure 13. Statue (150-cm-high) representing the “coup de barrière” placed on a family vault. Photo copyright author.

Figure 14. Individual tomb of a young man. On the inside wall of the grave, he is represented at a course camarguaise, wherein the raseteur and the tourneur are trying to distract the bull’s attention to catch award-winning attributes attached to the animal’s forehead and horns. The Camargue cross also features. In this case, a bull and a horse are positioned right next to the cross, making the connection between these various symbols even more explicit. Photo copyright author.

Figure 15. Photo montage of the deceased holding flowers and a trophy in the middle of the arena, while a bull is running toward a target outside the image. To the left of the photo montage is a photo of the deceased mounting a Camargue. Further to the left is another plaque featuring the Camargue cross. Photo copyright author.

Discussion

The Perspective of the Bulls

It must be noted, however, that the narrative about a human–bull osmosis and the blurring of boundaries between human and animal appear as somewhat romanticized when the perspective of the bulls is taken into consideration. Whether they are glorified as “heroes” or humiliated as “failures” soon to be turned into food, bulls are positioned as entertainment commodities and their fate depends on their ability to perform for the human gaze. In their early years, the bulls that show a lack of aggressiveness or too much docility are deemed unsuitable for the courses and sent for slaughter, as bulls need to be mean (“méchant”) to be able to respond to the provocations of the raseteurs (Saumade, Citation1994). The bulls selected for the courses camarguaises are then castrated by “bistournage,” which consists of crushing each spermatic cord through the scrotum by means of forceps, an act which is characterized as “unequivocally painful” by the French National Veterinary Council (Ordre national des vétérinaires, Citation2021). Then, out of these, only the bulls who perform particularly well during the encierro (also known as the “laché de taureaux,” the release of the bulls) and, more importantly, at the courses are sacralized as “heroes.” Those who do not are commonly insulted by the audience, who calls for them to be sent to the abattoirs (“melon” is the term used to refer to a “failed” bull, which would be better off dead), and indeed they often are. Sometimes, those that are discarded at any stage of the selection process are consumed by human members of their own manade, although the latter practice can represent a taboo when gardians have invested significant time and care into the discarded bull as a potential champion (Saumade, Citation1994, pp. 148–150).

Moreover, during the courses and other tauromachic events in the region, bulls are excited and provoked by the (aspiring) raseteurs inside the arena or in the streets. This tormenting can be seen as the continuity of a cruel practice that has been imposed on bovids for hundreds of years in the area, a practice which preceded the Félibrige movement and which helped the promotion of the Camargue as the “pays taurin” (bullscape) when Baroncelli-Javon (re)invented the Occitan tradition. Until the middle of the nineteenth century, the wild cattle which grazed on the meadows of the Rhône Delta were largely used as draft animals. However, many of the male individuals were deemed difficult to domesticate owing to their alleged aggressive nature and were, instead, tormented as objects of popular games where local young men tested their courage by provoking a bull isolated in a pen. Progressively, all bulls who had low agricultural currency ended up being violently slaughtered by local butchers, who enjoyed riding and tormenting the bulls before putting them to death (Saumade, Citation1991, p. 152). One activity, which can be traced back to the sixteenth century in the region, called “bourgino,” was developed as a result of this. Bourgino, also known as “taureau à la corde,” occurred during Carnival or at the end of a harvest and involved municipalities buying an old bull unfit for plowing from a local farm and leading him with a rope attached to his horns through the village streets in order to be abused and humiliated by the entire population, until he died of exhaustion. After being butchered, the bull’s meat was shared among members of the village (Saumade, Citation1991, p. 153). After the French Revolution in the eighteenth century, following pressures from the Jacobin power, the tormenting of the bulls as part of the bourgino was progressively replaced by a more ritualized form of the game, which itself paved the way, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, to the courses camarguaises, the spectacles imbued with regional meaning and value by members of the Félibrige which we know today (Saumade, Citation1994). While the bourgino was still practiced regularly until the middle of the twentieth century, as testified by the dramatic story of Piles-Pilote, a bull who was a victim of this practice in the first half of the twentieth century (Saumade, Citation1991), the more violent aspects of the practice progressively disappeared. In the 1950s, the bourgino was officially banned by the Gard prefecture. Yet, this did not prevent some aficionados from trying to revive the practice in other departments. In Eyragues, for instance, which is located in the Bouches-du-Rhône, at the heart of this research’s field site, a group of aficionados attempted to organize a bourgino in 2015. However, the Cour d’appel of Aix-en-Provence prohibited the event following a complaint filed by the Société Protectrice des Animaux (SPA), France’s largest animal protection group (Bodarwé, Citation2015). Today, the releasing and exciting of the bulls in the streets has become more of a cultural performance (the “encierro” or “lâché de taureau” (release of the bulls)), rather than local entertainment about abuse and humiliation. This ersatz of the bourgino sees bulls being released around the village’s barricaded streets for aspiring raseteurs to test their skills or for local manadiers to assess the qualities of their bulls ahead of the courses.

Despite the controversial aspects of the activity, a deep process of identification takes place between people and bulls in the region, so much in fact that the bull and, by extension the horse and the gardian, have become central icons of a regionalist positioning in many aspects of the area’s social life, including in cemeteries. Today, for many, the symbol of the bull, thanks to the courses and other tauromachic activities, is sublimized as the essence of the Occitanie and Provence regions, and every attempt to prohibit any aspect of the local tauromachie (by animal protection groups, veterinarians, or other groups) are seen as a threat to regional identity. Moreover, as shown above, thanks to Baroncelli-Javon and other members of the Félibrige movement, in regional identity narratives one can hardly dissociate tauromachie from other more-than-human symbolism connected to the tripartite figure of the bull-horse-gardian and to the Camargue land more generally. As has been explored throughout this paper, the sublimation of these various more-than-human symbolic entanglements in regional identity narratives is such that it is taking center stage not only as people express this identity in life but also in death. Local cemeteries become invested as spaces where conceptions of more-than-human osmosis and eternity are overtly expressed.

Conclusion

The use of more-than-human iconography and symbolism in these cemeteries blurs several conceptual, and even some physical, boundaries. First, especially through the figure of the horse, it effaces the boundary between the human and the nonhuman world. The Camargue horse ridden by the gardian is the emblematic symbol of a mythical and eternal osmosis between people and the Camargue land. At the cemeteries, this specific symbol is accompanied by a language suggesting that, in the Camargue, all kinds merge into one. The same way the physical boundaries of the Camargue are said to often disappear in the Félibrige literature and in local conversations, this iconography suggests that, in death, the boundaries that separate humans from animals and the environment also vanish. Second, this more-than-human iconography blurs the boundaries between different spiritualities: the Christian faith and the fé biou. This is particularly striking with imagery representing the bull, traditionally associated with a symbol of paganism in Western Christianism, which nonetheless unproblematically cohabits with Christian signs and symbols at local Catholic cemeteries. Third, as aficionados are celebrated in death for the qualities associated with bulls in life, the idea of a shared essence between the raseteurs and the cocardiers further blurs the human–animal boundary and leads both kinds to be praised, and even glorified, in similar terms.

In the end, as one wanders around these cemeteries, it is the role played by boundaries in human societies which is put into question. Perhaps boundaries are never as powerful as when they are blurred. Indeed, while boundaries are dangerous tools that can lead to much violence and discrimination, the cases explored here indicate that, precisely because they can be blurred, boundaries are also direct windows into the rich worlds which they conceal, worlds where life and spirituality can be explored more organically.

Acknowledgements

I express my sincere gratitude to the anonymous reviewers and the journal editor for their comments which have elevated the paper.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 This contrasts with cemeteries observed in other regions of France. Since 2020, I have also visited cemeteries in the Auvergne, Bourgogne, Champagne, and Île-de-France regions looking for personalized artifacts representing animals but have only found a very small number of them (usually between 0 and 3 in each cemetery I visited). When animals were represented, it was usually cats or dogs.

2 Here, industrially made plaques refer to the objects that can be bought directly as standardized pieces, without any modification, on various websites or directly at the funeral home (pompes funèbres).

3 It must be noted that older graves with symbolism might have existed, but as is customary in this part of France, because tombs that are going out of use are often demolished to make room for new ones, these graves might not have been preserved.

4 The use of the bull as sacrificial object/subject is often associated with Mithraism. However, as Pastoureau highlights, in Mithraic rites, the bull sacrificed is not conceived of as a god or demi-god, and claims about an alleged ancestry of Mithraic rites for contemporary bullfighting in Europe (made, among others, by members of the Félibrige) appear historically unfounded (Pastoureau, Citation2020, pp. 136–151).

5 Baratay argues that this instrumental disavowal of an animal religion paved the way to the de-sacralizing/secularizing of animals as we know it today in many Christian societies (Citation2001). While it is fair to assume that not all animals were killed through rites before Christianity took over, the changing of slaughter into a largely profane activity trivialized their killing and, thereby, further distanced human responsibility from moral considerations related to nonhuman death. This was destined to establish Christianity as a more “civilized” religion than paganism (and other religions), where humankind received a “naturally” elevated status in opposition to other creatures (Baratay, Citation2001). In that perspective, the inclusion of animals in matters related to human death was further proscribed and constructed as an immoral practice.

6 Pastoureau (Citation2020) also notes that in the work of eighteenth-century naturalists (e.g., Buffon, Daubenton), the bull was associated with a series of newly negative qualities like stubbornness and stupidity. Pastoureau argues that this is perhaps owing to the difficulty to classify the bull as either fully wild or domestic and that, as observed by the French historian, naturalists are always less kind when animals hardly fit into their categories and, indeed, blur conceptual boundaries.

7 This bond is said to be quite different from the one between the bulls used for the Spanish corrida and their breeders, where the bull is said to be strong or soft depending on whether he is seen as “too domesticated.” Indeed, while all bulls are bred in captivity, specifically for the corrida, those who perform well in the Spanish arenas are said to be wild (see Saumade’s work for a more detailed account of these categories (Citation1994, Citation1995)).

References

- Agence technique départementale (ATD) des Bouches-du-Rhône. (2019). L’interdiction d’inhumer les cendres d’un animal dans un cimetière communal. https://www.atd13.fr/linterdiction-dinhumer-les-cendres-dun-animal-dans-un-cimetiere-communal/

- Allix, A. (1930). La faune terrestre du Bas-Rhône. Géocarrefour, 6(1), 92–94. https://doi.org/10.3406/geoca.1930.6300

- Aubert, F. J. (1932). Race chevaline camargue. Presses Larguier.

- Baratay, É. (1995). La mort de l’animal dans l’imaginaire catholique (France, XVIIe-XXe siècle). Revue de L'histoire des Religions, 212(4), 453–476. https://doi.org/10.3406/rhr.1995.1251

- Baratay, É. (2001). De l’équarrissage à la sépulture. La dépouille animale en milieu catholique. In L. Bodson (Ed.), La sépulture des animaux (pp. 15–35). Presses de l'Université de Liège.

- Baratay, É. (2008). Bêtes de somme: Des animaux au service des hommes. Éditions de la Martinière.

- Baratay, É. (2011). Chacun jette son chien. De la fin d’une vie au XIXe siècle. Romantisme, 153(3), 147–162. https://doi.org/10.3917/rom.153.0147

- Baratay, É. (2015). L’Église et l’animal: (France, XVIIe-XXIe siècle). Les Éditions du Cerf.

- Bataille, G. (1988). The accursed share: An essay on general economy. Zone Books.

- Bodarwé, C. (2015). Bouches-du-Rhône: Le taureau à la corde interdit à Eyragues. Midi Libre. https://www.midilibre.fr/2015/06/25/le-taureau-a-la-corde-interdit-a-eyragues,1181236.php

- Brisebarre, A.-M. (1998). Préserver la vie des bestiaux pour programmer leur mort. Études rurales, 147(1), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.3406/rural.1998.3623

- Brisebarre, A.-M. (2003). La messe des animaux. Communications, 74(1), 139–158. https://doi.org/10.3406/comm.2003.2133

- Carretero, L. (1987). Traditions taurines entre mer et Vidourle. Aigues-Mortes et Saint-Laurent-d'Aigouze. 1580–1860. Presses de Nîmes.

- Couloubaritsis, L. (2000). Aux origines de la philosophie européenne: De la pensée archaïque au néoplatonisme (3e éd.). De Boeck Université.

- De Heusch, L., & O’Brien, L. (1985). Sacrifice in Africa: A structuralist approach. Manchester University Press.

- Descola, P. (2014). Beyond nature and culture. The University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226145006.001.0001

- Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (1954). The meaning of sacrifice among the Nuer. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 84(1/2), 21. https://doi.org/10.2307/2843998

- Fournier, L. S. (2003). Les fêtes locales en Provence: Des enjeux patrimoniaux. Culture & Musées, 1(1), 41–63. https://doi.org/10.3406/pumus.2003.1166

- Gaillemin, B. (2009). Vivre et construire la mort des animaux: Le cimetière d’Asnières. Ethnologie française, 39(3), 495–507. https://doi.org/10.3917/ethn.093.0495

- Gennep, A. van, Vizedom, M. B., & Caffee, G. L. (2019). The rites of passage (2nd ed.). The University of Chicago Press.

- Govindrajan, R. (2015). “The goat that died for family”: Animal sacrifice and interspecies kinship in India's Central Himalayas. American Ethnologist, 42(3), 504–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12144

- Halttunen, K. (1995). Humanitarianism and the pornography of pain in Anglo-American Culture. The American Historical Review, 100(2), 303–334. https://doi.org/10.2307/2169001

- Hobsbawm, E. J., & Ranger, T. O. (Eds.) (2012). The invention of tradition. Cambridge University Press.

- Hubert, H., & Mauss, M. (1981). Sacrifice: Its nature and function. University of Chicago Press.

- Hume, D., Selby-Bigge, L. A., & Nidditch, P. H. (1978). A treatise of human nature. (2nd ed.). Clarendon Press.

- Kete, K. (1995). The beast in the boudoir: Petkeeping in nineteenth-century Paris. University of California Press.

- Lynch, M. E. (1988). Sacrifice and the transformation of the animal body into a scientific object: Laboratory culture and ritual practice in the neurosciences. Social Studies of Science, 18(2), 265–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631288018002004

- Martel, C. (1993). Des mots pour un pays. Marqueurs lexicaux de l’écrit et de l’oral en Camargue. Le Monde alpin et rhodanien. Revue régionale d’ethnologie, 21, 63–84. https://doi.org/10.3406/mar.1993.1504

- Mauss, M., Riley, A., Daynes, S., Isnart, C., Hubert, H., & Hertz, R. (2009). Saints, heroes, myths, and rites: Classical Durkheimian studies of religion and society. Paradigm Publishers. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781315632292

- Musset, R. (1916). L’élevage du cheval en Camargue. Recueil des travaux de l’institut de géographie alpine, 4(3), 297–310. https://doi.org/10.3406/rga.1916.4862

- Ordre national des vétérinaires. (2021). Le bistournage des bovins. https://www.veterinaire.fr/la-profession-veterinaire/nos-grands-dossiers/la-protection-animale/le-bistournage-des-bovins

- Pastoureau, M. (2020). Le taureau: Une histoire culturelle. Éditions du Seuil.

- Pelosse, V. (1990). Jeu avec l'animal et pratique identitaire. Autour du taureau Camargue. Études rurales, 118–119, 303–310. https://doi.org/10.3406/rural.1990.4693

- Picon, B. (1988). L'espace et le temps en Camargue. Actes Sud.

- Saumade, F. (1991). Mythe et histoire dans une société du spectacle tauromachique. Ethnologie Française, 21(2), 148–159.

- Saumade, F. (1994). Des sauvages en Occident: Les cultures tauromachiques en Camargue et en Andalousie. Editions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme.

- Saumade, F. (1995). L’élevage Du Taureau De Combat: Du Héros Au Mythe Essai D’anthropologie Comparée. L’Homme, 35(136), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.3406/hom.1995.369998

- Schmitt, J.-C. (2004). Le saint lévrier: Guinefort, guérisseur d’enfants depuis le XIIIe siècle. Nouvelle édition augmentée.

- Serpell, J. A. (2005). Animals and religion: Towards a unifying theory. In F. de Jong & R. van den Bos (Eds.), The human–animal relationship (pp. 9–22). Royal Van Gorcum.

- Singer, P. (1995). Animal liberation (2nd ed.). Pimlico.

- Skabelund, A. H. (2011). Empire of dogs: Canines, Japan, and the making of the modern imperial world. Cornell University Press.

- Turner, V. W. (1995). The ritual process: Structure and anti-structure. Aldine de Gruyter.

- Zaretsky, R. (2004). Cock and bull stories: Folco de Baroncelli and the invention of the Camargue. University of Nebraska Press.