Abstract

Many of us consider ethnographic and biographical films as fixed categories, serving differentiated knowledge schemas. Yet, in the context of autobiographical filmmaking, the categories overlap, and new aesthetic and genre possibilities emerge. This article arises from this context; where post-Independence South Sudan’s film narratives merge visual ethnography’s attentiveness with realist narration, and biographical film’s reflexivity toward melodramatic self-narration. Using Akuol de Mabior’s No Simple Way Home (Citation2023) as a case of this genre overlap, this article proposes ethnobiopic as an appropriate coinage. It ends with a discussion of the perlocutionary possibilities for its characterization.

ETHNOGRAPHIC REALISM OR AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL MELODRAMA?

The year 2022 was the centenary celebration of one of the most canonical realist films, Robert J. Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (henceforth Nanook). Although his Moana (Citation1926) also documented everyday life in Pacific islands a few years later, Nanook is his most regarded and still discussed film. In her Library of Congress essay marking Nanook’s centenary, Stacie Seifrit-Griffin says: “It has been watched and discussed… as a complicated combination of art and ethnography, docudrama and reenactment, exploitation and cooperation” (2022).Footnote1 She describes the film as “a Rosetta stone for debates about documentary ethics, representation, ethnography, orientalism.” Her article continues: “Nanook evokes many documentary styles: reenactment, staging, observational mode, ethnography, exploration, poetic experimental film, participators’ mode, fiction, portrait, travelogue, landscape, adventure film, nature film, hybrid forms combining fiction and film.” Her description suggests that no visual medium is neutral in production, observance, or interpretation. Nanook primarly offers an exposé of the Inuit’s life in their Tundra world. It also offers a perspective of this place—the Ungava Peninsula of northeastern Canada, its Inuit people (the family life of Nanook–played by Allakariallak, a member of the Itivimuit tribe), and what the filmmaker thought as being representative of it—what was visually prioritized and encoded in the film. Thus Nanook circulates across different disciplines as an ethnographic film example par excellence, but also as a potentially subjective narrative which suffers the drawback of focalization. Mieke Bal describes focalization as “One’s position with respect to the perceived object, the angle of the light, the distance, previous knowledge, psychological attitude toward the object—all these things and more affect the picture one forms and passes on to others” (Bal Citation2017, 132). To echo Christian Metz, the film “possesses various 'dialects,' and that each one of these 'dialects’ can become the subject of a specific analysis” (Citation1974, 93). This scenario befell Nanook, a film that has attracted diverse interpretations as scholars grapple with the epistemology of its images.

Semioticians describe it as both a “biological and ethnographic” documentary and a work of art (ibid. 82). For anthropologists the film illustrates “the importance of living with ‘the people’ themselves over a considerable period” (Edwards Citation1997, 41).Footnote2 Visual ethnographers consider it an example of a viable methodology:

The humanism of the work, the acknowledged, collaborative relationship between director and subject, and Flaherty’s commitment to long-term immersion in native life as the precondition for its representation, are recognised as unique features which have endured over the years. (Grimshaw Citation2005, 17).

In this respect Nanook usefully exemplifies how ethnographic or realist cinema attracts complex interpretations. This is in part due to the limits of the semiotic method, whereby images may be read autonomously from their narrative context. In particular, close reading presumes such autonomy to be a priority. It however poses some theoretical challenges where treating film images as an autonomous data source: this restrains the interpretation of film images only to its singular elements and isolates them from other considerations which gives them significantly more situated meaning. The production and consumption of a realist film however presume an intentional story encumbered with personal biases and subjectivities. Its meaning is thus contextual, encompassing cultural orientations, social functions, and political and historical inclinations. These interrelate with the meaning of its images.

The debate about what constitutes a realist or a melodramatic image has been long and inconclusive. On one hand, ethnographic realism and cinéma vérité presume the primacy of the director’s virtuoso genius in the production of the image. The realism of the image is fixed and does not depend on whether the film is eventually completed or abandoned, whether it is accepted or not, and whether or not it is widely acknowledged. Further, the meaning of the film presumes an “aesthetic autonomy … that positions art as independent of any external conditions” (Brott Citation2020, 150). Whatever other meanings may materialize through a film’s connotations—such as political realism which cannot be separated from the denotations surrounding its production—continue to be hosted within the film immaterially. Thus its realism is ontologically immanent in any and every part of the image, and then as a whole—including its subjects and their political realist projections.

On the other hand, a healthy debate ensues concerning whether autobiographical film narration incurs interferences. Acknowledging Elizabeth Bruss’s claim that “There is no real cinematic equivalent for autobiography" (Citation1980, 296), Tony Dowmunt challenges the above perspective in two ways. (i) He disputes that filmmaking automatically comprises “a wide range of distinct authorial agents”:

it has never held for the more avant-garde practices, and has also been increasingly undermined, across all forms, by developments in video and digital technology (in particular camcorders, mobiles, webcams, and desk-top editing), which allow for individual authorship in hitherto impossible ways (2013, 264).

(ii) Dowmunt also challenges Bruss’s requisite, arguing thus:

the autobiographical speaking subject has an ‘unquestionable integrity’ (which is undermined by the range of authorial agents often involved in filmmaking), [that] now seems an undesirable goal, given that we are so aware of the inevitably fragmented and relational nature of the self. Indeed, this awareness means that film is a particularly useful medium for contemporary forms of autobiography. (2013, 264)

the radical potential of autobiographical documentary derives not only from ‘what we show ourselves to be’ but also from the relationship between ‘seer and seen’–how we show ourselves with our cameras: it’s this self-shooting reflexivity that helps create—and is a crucial element of—the ‘counter discourse.’ (2013, 275)

exist somewhere in the middle ground between these two groups, and so tend to subvert both the omniscient surveillance of the ‘other’ implicit in her phrase the ‘all perceived,’ and the sovereign subjectivity conveyed by the phrase ‘all perceiving.’ (2013, 264)

From the above it is evident that what these scholars, originating from different intellectual epochs, are struggling with is not the usage of film for autobiographical purposes–they all acknowledge it. They are trying to grasp how the realist or ethnographic expectations for the autobiographical story can be reconciled with the subjectivities of the medium of audiovisual production (authorial interference, technological limits, and the translational fabrication of the filmed story). In the intense global debate which the author outlines, it is arguable that Dowmunt’s (ibid.) effort may not have budged the case against the subjectivity and reflexivity of autobiographical film, which “resists a conclusive generic definition” and should be “understood as a personal record of whatever a filmmaker chooses from her life and experience–based on moving images and sound instead of words alone” (Christen Citation2019, 336). My entry into this conversation is guided by the question: Can a film be fully ethnographic without being at all melodramatic? To respond, I turn to one of South Sudan’s most recognized autobiographical films, No Simple Way Home.

No Simple Way Home

South Sudan’s political history unveils a reality of competing efforts for political leadership and power. The earliest struggles sought to delink southern Sudan from the Republic of Sudan [hereafter Sudan]. These struggles used political ideology, culture and religion as vortexes to mobilize resistance against Sudan, even after it gained independence from Anglo-Egyptian colonialism in 1956. Its southern region, under the leadership of various army generals and political figures, picked on what they called the Southern Problem as a mobilization idea to fight against the north, their collective enemy. At the helm of the southern leadership was Dr John Garang de Mabior (hereafter Dr Garang), the leader of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement and its military arm, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army. The south’s long years of civil wars against Khartoum ended in 2005 with the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement between the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement and the Government of Sudan.Footnote4 Yet even after South Sudan’s independence in 2011, there have been significant conflicts motivated by ethnic tensions, culminating in the 22 February 2020 formation of the Revitalized Transitional Government of National Unity [RTGoNU]. This quest for national leadership has created a space for political narratives as leaders from different ethnic groups contest for national and global visibility. Consequently, new forms of self-narration and self-authentication, aligned with the country’s political history, have emerged. These have become platforms for political figures to reposition themselves auspiciously within the national political narration, claiming both realistic evocations of this history and personal conspicuousness in this history. Akuol de Mabior’s No Simple Way Home (Citation2023)Footnote5 is exemplary of this emerging trend.

The present article arises from this context; where post-independence South Sudan’s film narratives merge political realism and an ethnographic or cinéma vérité style, along with biographical self-narration with its melodramatic interests. These narratives focus on this style-and-genre overlap between autobiographical documentary film’s need for ethnographic representation and the subjectivity of autobiographical self-representation. Treating No Simple Way Home as a case of this genre overlap, this paper proposes the term ethnobiopic film to designate its aesthetic. A post-Independence South Sudan film, No Simple Way Home portrays the political story of Rebecca Nyandeng de Mabior (hereafter Rebecca), the wife of the country’s late leader, Dr Garang, on one hand; and on the other, her private experiences in her pursuit of political visibility. The story starts with the protagonist’s return from exile in Nairobi, dwelling on her private and public activities after her family’s return to Juba, in South Sudan. The film is set in 2019, eight years since South Sudan had gained independence, and fourteen years after the death of Dr Garang. In the film Akuol is the author-director, while her mother Rebecca is the protagonist. It uses an ethno-documentary style that combines actual archival footage from the past with footage of the present, to render the family’s story alongside the country’s factual history. The film also uses family photographs to augment the verisimilitude of the protagonist’s allegiance to her culture, traditions, and incidental investment in national politics. It uses noticeable dramatic features such as flashbacks, with the backdrop of pre- and post-cessation struggles and civil wars, to authenticate the protagonist’s contiguity in the national narrative. The film’s plot is linear, allaying the protagonist’s character arc along the temporality of the nation’s political history.

The film is concerned with Rebecca’s visibility within national history, giving a clear perspective of her social, cultural and political prerogatives. We may appraise the film within the broad genre of historical films, those which include epics, docudrama, ethnofiction, and so on. It seems however to lean more toward biographical narration, where ethnographic efforts to document Rebecca’s personal and political everyday life combine with melodramatic intent for political visibility. In the former, the film combines Rebecca’s life as an exile, her return home, the cultural authenticity, communal belonging, and maternal identity, to present her struggles as authentic social experiences that cannot be separated from her countryman’s everyday lived experiences. In the latter, the director privileges her political profile, both as the widow of South Sudan’s founding father and later, as an iconic national figure involved with pro-citizen politics. Accordingly, the film offers a fusion of realist and melodramatic indulgences, leaning on national history and private memory. In this respect it invests its story in the protagonist’s capacity to narrate herself, using the film as a medium of documentation. No Simple Way Home can thus be viewed as the first biographical film told from the frontline. This is because its protagonist and director are historically at the helm of the country’s struggles, struggles which culminated in Dr Garang’s 2005 senior role as Sudan’s vice-president. On this account the film uniquely presents us with the subject of truthfulness, accuracy and objectivity in the visual representation of national and personal histories. This also confers upon it its aesthetic of political realism. It is for this reason that we might read No Simple Way Home’s narrative—which overlays a personal subjective story and realist film aesthetic—as offering a current example to explore the confluence of political realism and film genre.

HYBRIDITY IN ETHNOGRAPHIC FILM: REFLECTIONS ON AN ETHNOBIOPIC GENRE

In No Simple Way Home Akuol functions as a visual ethnographer of South Sudan’s recent history. She interviews her mother, the protagonist, and guides her self-narration. Her filming, which allows her into the protagonist’s private life, affords her the privileged position of a visual ethnographer, leaning her film toward a realistic representation. The film is inclined toward a realistic, truthful representation of the chronology of South Sudan’s political history; and is an effort to narrate the protagonist’s life as lived through this particular history. This task is realized through a back-and-forth swirl of the narrative spine, anchored on one hand by the iconic struggle for Independence and its conflictual aftermath; and on the other, by the protagonist’s experiences and her indexicality of this history. It is through this narrative style, one that uses actual footage and photographs and the director’s long-term involvement in documenting various moments of this story, that the film acquires its ethnographic qualities. Concurrently the film’s keen interest in singular documentation of the protagonist’s prominent national profile confers on it autobiographical qualities. My discussion of No Simple Way Home as an ethnobiopic film originates from this conceptualization: that it enables different relationships which offer varied perlocutionary possibilities helpful in signposting its characteristics. Here I will discuss its collocation of multiple temporalities, the context of images, and authorial correspondence, as three approaches to characterizing the ethnobiopic film.

Temporal Juxtaposition

Ethnographic cinema deals with the present, the here-and-now. It is concerned with recording events as they are taking place, amassing details through repeated observation. Its realism arises from its adherence to this style, with the expectation that the mechanism of image production, including technical and creative devices, and the crew, will not be inclined to distort or interfere with the truthfulness of that which they are recoding. In contrast, autobiographical films deal with the past. They recount events that have already happened, arranging this information into a coherent, linear archive of their subject’s experiences. Thus for the autobiographical filmmaker the present and its observation offer little value; a clear memory or a record of the past is preferable. The concurrence of these conflicting treatments of temporality and validity of the filmed information creates a scenario peculiar to ethnobiopic cinema: that narrative time may overlap. And this is what Akuol’s film does: it props the protagonist’s past against her present, fuzing her past and present into a single temporal unit. In this sense the protagonist actuates an uninterrupted continuity of time.

The most noticeable stylistic feature of No Simple Way Home is the extensive use of Rebecca’s family photos alongside motion footage. Together these visual resources connect us to the film’s "realism" without claiming a singular version of exactitude, but instead offering a recipe for the film’s—and hence ethnobiopic’s—unpredictable textuality. It might be said that Akuol’s film “deals not with the stability, but rather with the transformation of an image” (Vidal Citation2014, 7); that is, its photographic elements do not render a stout political story, but use images to enunciate the transformations in this political story. Because the story changes within different political temporalities the meaning of the images changes too. Thus its textuality is not representational but constitutive of its reality (Neumann and Nünning Citation2012, 105). The film’s images and the story they tell are, for us, an aperture into a new dimension of political thought in South Sudan. I theorize this dimension as a "regime of truth" concerned with

not how photographic truth may be emancipated from every system of power, but how we may construct a new politics of truth by detaching its power from the specific forms of hegemony in the economic, social and cultural domains within which it operates at the present time. (Tagg Citation1988, 189)

Within Akuol’s film, truth or its claim is achieved through the conjunction of past and present in the photographic and film media, to evoke the persistence of the old "politics of truth" symbolized by Dr Garang’s iconicity as the Father of the Nation. The film thus retrieves this frame of truth to challenge the contemporary political hegemonies, where Dr Garang’s truth—now physically absent, yet mnemonically symbolized through his wife, Rebecca—may feature in contemporary national discourses. The photographs and the film footage enable a semiotic realization of this truth.

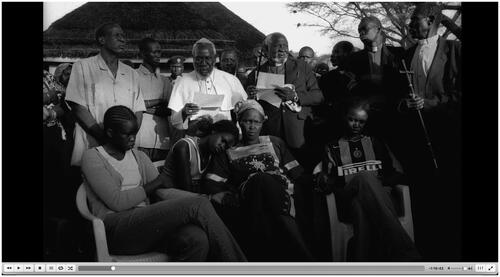

The most poignant image in the film is that of the protagonist and her family when mourning her late husband, surrounded by family and community (). This image encodes numerous aspects of realist images. It captures an actual historical moment: showing the protagonist with her children (seated in the front row), surrounded by clergy, family and community members. It also uses a familiar setting, a customary homestead—signified by a traditional thatched hut—as the background for the shot. The scene is not reenacted for the camera; it features real people at an actual event that happened during the protagonist’s life. The community members, and even a security officer visible in the middle ground, authenticate this moment both as a private experience and as important national history. The shot’s focus is Rebecca; her children accentuating the verisimilitude of her bereavement. It is graded in monochrome color and composed with a wide-angle framing syntagmatically signaling the film’s reluctance to scrutinize the moment of bereavement. It thus represents the reality of Dr Garang’s death; with its psychological, physical and spiritual aftermath (he had died in a questionable aircraft crash). The congregation of his family and mourners can be said to encode a biographical truth. Yet, because this photo and the video footage which comprise the montage present the director’s "take" on this story, cannot be said to offer an absolute social realist documentation of that moment. Furthermore, the voice-over narration which accompanies the shot—“My mother became a widow the year she turned fifty. I was sixteen”—adds a subjective element to the photo, so that we interact with it not as a moment purely of bereavement but as an emotive representation of the protagonist’s experiences of loss. In this sense uses the exiguous community to illustrate the sense of loss on a national scale occasioned by Dr Garang’s death. It also designates the family and their Dinka community as an appropriate symbol for articulating this imagery.

Figure 1 Rebecca and her family while mourning Dr Garang’s death. She is accompanied by clergy, family, and other community members. (Screen freeze-frame from No Simple Way Home). Accessed from Afri Docs’ (@AfriDocs)—https://youtu.be/90m7gpKKnqU

Image and Context

Narrating his classroom experiences when he screened Nanook, Keyan Tomaselli notes that not only did the South African students not identify with the documentary’s aesthetics or its semiology, but it was his grandson, then aged one year, who found meaning in the image of a husky and he started barking at the screen. Tomaselli concludes that “The researcher’s semiotic offers only an idealist baseline or benchmark against which to explain [different] polysemic interpretations” (Citation2018, 86). He explicates how the rapport between the documentary image and the audience may influence the perlocutionary meaning of the film. This example provides a usable analogy of how an image-and-audience relationship influences how we make meaning of film images, even when they claim realist accuracy. Here, because the film’s meaning depends on the viewer, we focus on the location of interpretation: the interpretant. The interpretant is “the understanding that we have of the sign/object relation” (Atkin Citation2023). Cecil Elliott says that

a monument does not really function as a means of explicit communication. It is predicated upon the assumption that the viewer already knows pertinent facts about it and its subject, and monuments are customarily overlaid with minutiae and subtleties of symbolism which are meaningless without the viewer’s previous knowledge. (Elliott Citation1964, 52)

Interaction with a monument involves the viewers’ translation of the monument. Because the interpretant allows translation and hence manipulation of the original meaning (Liszka Citation1996) in this aspect, the circulation of images imbued with commemorative qualities, such as is the case of Akuol’s film, stretches the translation of the protagonist beyond the usual bi-axis: the object (in this case, Rebecca as a specific signifier) and the signified (post-Independence struggles against political aggrandisement). There is another fork, the political realism of the filmed object (a new front of translating South Sudan’s past ideals against its contemporary chaos); and still another one, the director (who is equally meaningful in translating this history through their place in that history). Thus, any effort to read the film is preceded by the protagonist’s initial action: appearing in the film as Dr Garang’s wife was itself an act of translating an event into a historical discourse.

Combining a specific historical frame—the authenticity of the struggle for an independent South Sudan—with the contemporary crisis of the protagonist’s national belonging, No Simple Way Home uses complex temporality (at once contiguous and transverse) to rekindle in the present South Sudanese a sense of patriotism. The still and video images of Dr Garang, when combined with those of Rebecca in the past and present, index a past–present seamlessly overlapping in the national discourse, and hence enhance the ethnobiopic film’s realism. The persistence of the motif of resistance and struggle for a better political, social and economic life which this juxtaposition enables resonates with the contemporary South Sudanese whose memory of struggle continues to attract numerous discussions (Bentrovato and Skårås Citation2023; Belloni Citation2011; Deng Citation2005; Frahm Citation2012; Johnson Citation2016; Kuyok Citation2015; Rolandsen Citation2015). It is a strategy which occasions a debate about the reality of citizenship in present times, especially in the context of the reality of struggle which the film emphasizes.

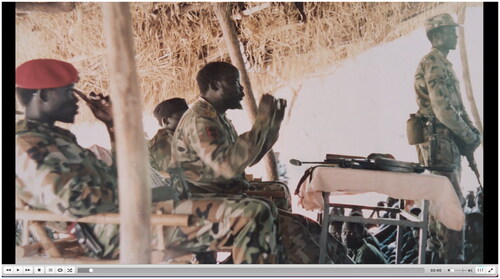

Contextually the ethnobiopic film image offers a confluence of “content, social context and materiality of images” (Pink Citation2003, 179). This is attributable to the subjectivity of both the filmmaker and the camera. On the former, the documentary image offers possibilities of “collaboration and self-representation, which involves reflecting on the potential of fiction, artifice, and montage to imagine and render material desires, aspirations, and ideas of the future” (Vailati and Villarreal Citation2021, 4). On the latter, the concern is whether we should imagine the camera within its unsophisticated role as an instrument of observation, or do recognize its cinematographic language (framing, composition, mise en scène, lighting, sound, etc.) as integral components of the image’s epistemology. Even ethnographic videos have been termed more than “simple recording media—‘consumables of research’” ; they are “objects and even merchandise, which, like people, have social lives” (Larcher Citation2021, 40–41). Terming the ethnographer as a merchant and the image as a product makes the camera a connotative device and no longer a source of "pure documentary" data. Akuol’s concern with the present in her film is staked on the narrative premise: that the meaning of South Sudan’s past struggle–euphemistically referred to as Freedom–was at risk of potential plundering and thus merited preservation. Because this past was materially inaccessible, she "represented" it mnemonically using Dr Garang’s historical images and footage. One of these images (), is a wide shot, showing Dr Garang wearing a military uniform.

Figure 2 A still photograph of Dr Garang with SPLM fighters at an undisclosed location afield. It shows his political and military frontline role during pre-Independence struggles. (Screen freeze-frame from No Simple Way Home). Accessed from Afri Docs’ (@AfriDocs)—https://youtu.be/90m7gpKKnqU

In this image’s mise en scène three other soldiers are also prominent in the frame: one on each side of him and one in front. They are armed with guns. There is a table in front of Dr Garang’s seat, with a gun placed on top. A wooden pole is visible in the foreground left and another in the middle background, supporting a thatched roof partially visible above. A group of fighters is also visible sitting in the background, at a lower level. They peer toward the foreground from beneath the table. This photographic image is one among many used in the film that illustrate Dr Garang’s leadership of Southern Sudan’s struggle for Independence. It popularizes his frontline life as a political and military figure within the history of South Sudan. Even as we process , as a portion of truthful history mnemonically transferred from a factual past to contemporary times, we also acknowledge its specific retrieval and usage as an act of processing cultural knowledge. It thus arrives within this montage as a harbinger of the director’s intention within the ethnobiopic: to preserve her country’s true past. These become clearer as the film subsequently retrieves and appropriates media clips of actual moments in the country’s history, not merely to authenticate that history but to use its authenticity to amplify the protagonist’s participation and inclinations. This inserts the protagonist into the national commemorative discourse and preserves the meaning of South Sudan symbolically as an idea that originated from British colonialism.

Authorial Correspondence and Autonomy

Flaherty’s involvement in Nanook "established" what was filmed and how it was filmed. This needs to be absolved or accounted for in discussing the meaning of the Inuit story. Flaherty’s long-term acquaintance with the Inuits calls for consideration of the filmmaker’s position during production and analysis (his objectives, strategies and methods), and how this positionality bears on the information given by the image. In Akuol’s case, her acquaintance with the protagonist is familial. To tell the story of her mother involved her familiarity with her family’s story, so that we may begin to see her involvement as conferring upon the film a melodramatic quality. In a discussion of self-narration and representation, James Battersby specifies two perspectives on self-representation: (1) “Episodic approach to self-experience, in which the self, considered as self, is a 'now’ phenomenon disconnected from the past and the future, and … Diachronic approach to self-experience, in which the self, considered as a self, is understood to persist in time from the past into the future”; and (2) “a non-Narrative form of self-representation and an attack against the dominance of the Narrative form of self-representation” (Battersby Citation2006, 27). In No Simple Way Home there exists a conflict between the diachronic approach to self-narration and the aesthetics of the ethnobiopic narrative style. At the diachronic level, we infer the consciousness of the protagonist to the filming process; she thus performs certain actions to curate experiences appropriate to her past, present and future national aspirations. The images presented by her director-daughter are thus collaboratively co-produced, integrating the past into the contemporary to account for her political future. At the level of the ethnobiopic narration, it is arguable that despite the filmmaker using a "realist" camera, she motivates some performativity and hence influences the image’s "narrative." To assign autonomy to the meaning of the film’s images, we should account for these correspondences.

Autonomously, semiotic analysis of the image examines “the filmed object… and not its pretext in the scenario” (Metz Citation1974, 201).Footnote6 The neutrality of the filmmaker in the production of such media is presumed, and truthfulness is enabled through “an ‘unprivileged’ single camera that offers the viewpoint, in a very literal sense, of a normal human participant in the events portrayed” (Pink, Kürti and Afonso Citation2004, 105–06). Yet even such images, while “an epistemological necessity to get at the details of human presence” (Hockings et al. Citation2014, 449), remains only tangential to the process. We may accordingly read the protagonist in Akuol’s film as a “relatum, whose definition cannot be separated from that of the signified” (Barthes Citation1964). Akuol presents us with a tableau of participatory and embodied nationalist efforts, her persona readily mirroring her real-life political identity. The selection of different photos and footage of her past, as well as media of her present, offer us a valid version of the national and individual cultures of South Sudan. They authenticate the nation’s experience of struggle and enable the protagonist to convey this historical portraiture autonomously. At the center of this portraiture is the protagonist’s photographic memory of her family life and simultaneously that of Dr Garang, and the melodramatic quality afforded through this juxtaposition.

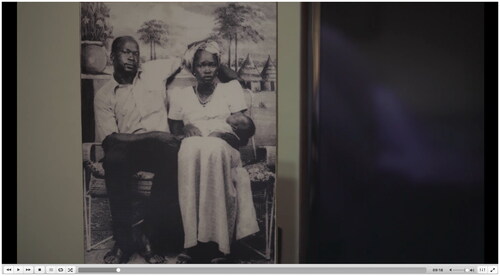

It becomes arguable that such a narrative approach represents a confluence of the film’s realist-melodramatic qualities in the sense contemplated by Louis Bayman, who notes a shared authenticity “with realism seeking to illuminate society’s motive forces, and melodrama focusing on innocence tormented by wicked dissimulators” (Citation2009, 47–48). This author continues: “melodrama, in cinema, is simply the pathos of the expressive elevation of fundamentally ordinary feelings, whereas realism is a recognizable attempt to bring representation closer to extra-filmic reality” (ibid., 48). In No Simple Way Home this tension between realist intentions and dramatic expression interacts with the tension within the film: a past of nationalist ideals in need of preservation, which is materially accessible for photographic conservancy; and a present where, at the risk of potentially plundering that intention, a materially inaccessible past is being "represented" mnemonically. The quest of the film thus is twofold: how to embalm this past so that it is not entirely lost, and how to secure it against pillage in contemporary times. Under photographic conservancy of a materially accessible past, the film uses images of the protagonist and her family, including her husband, Dr Garang, whose material presence in these pictures offers a tangibly representable visual element. Some of the photographs show his time with the family (), and others his political efforts (, discussed earlier). is an exterior photograph of Dr Garang and his wife, Rebecca, with their child. In this photo they are sitting in the foreground, with what appears as a painted poster forming their background. The painting shows a traditional homestead, with two thatched huts on one side. There are some tall trees in the background, and a flowerpot in the middle ground just beside Dr Garang. Both Dr Garang and his wife are well-dressed and wear open shoes. The two are seated close together, and Dr Garang is holding their child’s feet. The couple appear relaxed. This photo is placed against an otherwise mono-colored wall. The image expresses the social dimension of the film’s narrative. It retrieves the protagonist’s early family moment with her husband and their child, to mitigate the public image of the couple which privileges their political profile over their private family aura. It uses the aesthetic of ordinary family portraiture, a commissioned memory, which emphasizes family over politics. This image is pivotal in integrating the protagonist’s social profile with that of her present times, where the director captures her actively involved in numerous family moments; so that we see her first as a mother with a family history and not just a politician scrambling for power.

Figure 3 A photograph of Dr Garang and his wife, Rebecca, holding their child. It shows a private family moment during pre-Independence struggles. (Screen freeze-frame from No Simple Way Home). Accessed from Afri Docs’ (@AfriDocs)—https://youtu.be/90m7gpKKnqU

This family image is repeated in , which shows a framed photo of the protagonist holding her daughter. This photo uses the family’s interior space. In it Rebecca is sitting in the foreground holding her child. The house has modern furniture. Adjacent to the photo is a framed sculpture of a mother holding her baby—a semiotic double to the photo’s indexicality of motherliness. The two images are placed side-by-side on Rebecca’s office table. There are some documents on the table behind the photo and the sculpture. The background is blurred, its indistinguishable details aiding the prominence of the foreground elements. While the period of the photos is her past, the film shot in which they are included is of Rebecca’s present life, where she has become a senior government official. The picture thus retrieves the family motif to preserve her husband’s role as the head of the family, being coeval with his public figure as the Father of the Nation; incidentally conferring upon her the national role as "the mother of the nation."

Figure 4 A framed photograph of Rebecca holding her daughter. (Screen freeze-frame from No Simple Way Home). Accessed from Afri Docs’ (@AfriDocs)—https://youtu.be/90m7gpKKnqU

demonstrate how Akuol’s film connects the protagonist with distinct moments in South Sudan’s history, using material proximity to the country’s most iconic figure, Dr Garang. In , which presents the younger family, the proximity is material: Dr Garang and his wife are together. This physical proximity is repeated throughout the film by using family photos and archival footage. relies on Dr Garang’s material existence, despite the absence of the protagonist from this photo. Thus the semiotic meaning of both and extends beyond their montage within the film, and the temporality of the film story—which is in the present. They acquire an archival meaning of the family which, read alongside , places them at a specific position in South Sudan’s political history. This raises the question: Does this film memorialize supervenient infrastructures of history, or is it its continuant? If the photographic images immortalize remembrance of the nation’s liberation struggle at the family level, what do we call it when they immortalize a national forgetting of these sacrifices in preference for an individualistic preoccupation with power? Could it be that, in the effort to construct remembrance this film ends up officiating over a fractured memory? This is not to ask if historical documentation is subjective, but rather to ask what should we call objects of history such as historical photographs of Dr Garang’s family when these are remembered in a fractured manner?—remembered as a site of tension between remembering (what is remembered, what ought to be remembered) and forgetting (when it becomes a placeholder for the erasure of another; that is, occupies a space claimed by another). Because the images collocate the past and present, they also juxtapose–and hence occasion a semiotic montage–between the different psychological conditions designated by this past and the present. Besides accomplishing the memorial function, they offer a befitting allegory of how the protagonist’s meaning is given autonomy from the director’s authorial interferences, by privileging a record that precedes the director and connecting it with the present.

CONCLUSION

This article has reflected on the elusiveness of a genre category to theorize political narratives in South Sudan’s contemporary cinema. The convergence of competing interests in Akuol’s No Simple Way Home—political and historical realism on one hand, and the propensity for melodramatic self-narration on the other—create a peculiar mix of narrative interests and film genre aesthetics. Because such a film is neither purely ethnographic (fully realist) nor purely autobiographical (fully melodramatic), this article has proposed a new genre category, ethnobiopic, as a possible baseline for theorizing autobiographical films. This offering is a starting-point, inviting further debates on what this could mean in theorizing self-narration documentaries.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Addamms S. Mututa

Addamms Mututa is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Department of Communication and Media, University of Johannesburg. He holds a joint Ph.D. (Film Studies and African Literature) from the University of Tübingen, Germany, and the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. He researches African cinema and literature, post-apartheid cultures, critical theory, and postcolonialism.

Notes

1 This essay is a verbatim copy of an earlier essay titled “Nanook of the North”, written by Patricia R. Zimmermann and Sean Zimmermann Auyash. It is available here at: https://www.loc.gov/static/programs/national-film-preservation-board/documents/nanook2.pdf.

2 Here the film is discussed alongside Bronislaw Malinowski’s book, Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1925 [1992]).

3 One woman (Atangana), three men (Qisuk, Nuktaq, and Uisaakassak), and two children (Minik and Aviaq).

4 For descriptions of undivided Sudan in its final days see Stanford (2001) and Jok (Citation2002).

5 The film’s version hosted by DW Documentary is also invariably titled "South Sudan’s Rocky Road to Lasting Peace" (2023).

6 Metz here mentioned specific films: Nosferatu, M Le Maudit, and Nanook of the North.

REFERENCES

- Atkin, Albert. 2023. "Peirce’s Theory of Signs." edited by E. N. Zalta and U. Nodelman. Accessed from The Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy (Spring edn.); https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2023/entries/peirce-semiotics/.

- Aufderheide, Patricia. 2007. Documentary Film: A Very Short Introduction. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Bal, Mieke. 2017. Narratology: Introduction to the Theory of Narrative. 4th ed. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

- Banks, Marcus, and Howard Morphy (eds.). 1997. Rethinking Visual Anthropology. New Haven, CT, and London, UK: Yale University Press.

- Barsam, Richard, and Dave Monahan. 2010. Looking at Movies: An Introduction to Film. New York, NY, and London, UK: W.W. Norton.

- Barthes, R. 1964. Elements of Semiology. A. Travers and C. Smith, trans. New York, NY: Hill and Wang.

- Battersby, James L. 2006. “Narrativity, Self, and Self-Representation.” Narrative 14 (1): 27–44; https://doi.org/10.1353/nar.2005.0024.

- Bayman, L. 2009. “Melodrama as Realism in Italian Neorealism.” In Realism and the Audiovisual Media, edited by L. Nagib and C. Mello, 47–62. Basingstoke, UK, and New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Belloni, Roberto. 2011. “The Birth of South Sudan and the Challenges of State Building.” Ethnopolitics 10 (3–4): 411–429; https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2011.593364.

- Bentrovato, Denise, and Merethe Skårås. 2023. “Ruptured Imaginings amid Emerging Nationhood: The Unsettled Narrative of 'Unity in Resistance’ in South Sudanese History Textbooks.” Nations and Nationalism 29 (3): 1041–1056; https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12951.

- Brott, Simone. 2020. Digital Monuments: The Dreams and Abuses of Iconic Architecture. London, UK, and New York, NY: Routledge.

- Bruss, Elizabeth. 1980. “Eye for I: Making and Unmaking Autobiography in Film.” In Autobiography: Essays Theoretical and Critical, edited by James Olney, 296–320. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Carroll, Nöel. 1996. Theorizing the Moving Image. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Christen, Matthias. 2019. “Autobiographical/Autofictional Film.” In Handbook of Autobiography/Autofiction: Volume I: Theory and Concepts, edited by Martina Wagner-Egelhaaf, 446–455. Berlin, Germany, and Boston, MA: Walter de Gruyter.

- Dancyger, Ken. 2007. The Technique of Film and Video Editing: History, Theory, and Practice. 4th ed. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier.

- Deng, Francis M. 2005. “Sudan’s Turbulent Road to Nationhood.” In Borders, Nationalism, and the African State, edited by Ricardo R. Laremont, 33–86. Boulder, CO, and London, UK: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Dowmunt, Tony. 2013. “Autobiographical Documentary – The ‘Seer’ and the Seen.” Studies in Documentary Film 7 (3): 263–277.

- Edwards, Elizabeth. 1997. “Beyond the Boundary: A Consideration of the Expressive in Photography and Anthropology.” In Rethinking Visual Anthropology, edited by Marcus Banks and Howard Morphy, 53–80. New Haven, CT, and London, UK: Yale University Press.

- Egan, Susanna. 1994. “Encounters in Camera: Autobiography as Interaction.” MFS Modern Fiction Studies 40 (3): 593–618; https://doi.org/10.1353/mfs.1994.0002.

- Elliott, Cecil D. 1964. “Monuments and Monumentality.” Journal of Architectural Education 18 (4): 51–53; https://doi.org/10.1080/00472239.1964.11102200.

- Frahm, Ole. 2012. “Defining the Nation: National Identity in South Sudanese Media Discourse.” Africa Spectrum 47 (1): 21–49; https://doi.org/10.1177/000203971204700102.

- Grimshaw, Anna. 2005. “Eyeing the Field: New Horizons for Visual Anthropology.” In Visualizing Anthropology, edited by Anna Grimshaw and Amanda Ravetz, 17–30. Bristol, UK, and Portland, OR: Intellect Books.

- Grimshaw, Anna, and Amanda Ravetz (eds.). 2005. Visualizing Anthropology. Bristol, UK, and Portland, OR: Intellect Books.

- Hockings, Paul, Keyan G. Tomaselli, Jay Ruby, David MacDougall, Drid Williams, Albert Piette, Maureen T. Schwarz, and Silvio Carta. 2014. “Where is the Theory in Visual Anthropology?” Visual Anthropology 27 (5): 436–456; https://doi.org/10.1080/08949468.2014.950155.

- Huhndorf, Shari M. 2000. “Nanook and His Contemporaries: Imagining Eskimos in American Culture, 1897–1922.” Critical Inquiry 27 (1): 122–148; https://doi.org/10.1086/449001.

- Huhndorf, Shari M. 2001. Going Native: Indians in the American Cultural Imagination. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Johnson, Douglas H. 2016. South Sudan: A New History for a New Nation. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

- Jok, Jok Madut. 2002. “Dinka.” In Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Supplement, edited by Melvin Ember, Carol R. Ember and Ian Skoggard, 100–104. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA.

- Kuyok, Kuyok Abol. 2015. South Sudan: The Notable Firsts. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse.

- Larcher, J. 2021. “The Ethnographer as Merchant: Making Commissioned Home Movies in Postsocialist Romania.” In Filming Real People: Ethnographies of “On Demand” Films, edited by Alex Vailati and Gabriella Z. Villarreal, 29–46. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Liszka, James J. 1996. A General Introduction to the Semeiotic of Charles Sanders Peirce. Bloomington, IN, and Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1922 [1992]. Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea. London, UK, and New York, NY: George Routledge.

- Metz, Christian. 1974. Film Language: A Semiotics of the Cinema. M. Taylor, trans. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Neumann, Birgit, and Ansgar Nünning. 2012. “Travelling Concepts as a Model for the Study of Culture.” In Material Culture and Materiality, edited by Birgit Neumann and Ansgar Nünning, 1–22. Berlin, Germany, and Boston, MA: Walter de Gruyter.

- O’Mahony, Mike. 2008. Sergei Eisenstein. London, UK: Reaktion Books.

- Pink, Sarah. 2003. “Interdisciplinary Agendas in Visual Research: Re-Situating Visual Anthropology.” Visual Studies 18 (2): 179–192; https://doi.org/10.1080/14725860310001632029.

- Pink, Sarah. 2006. The Future of Visual Anthropology: Engaging the Senses. London, UK, and New York, NY: Routledge.

- Pink, Sarah, Laszlo Kürti and A.I. Afonso (eds.). 2004. Working Images: Visual Research and Representation in Ethnography. London, UK, and New York, NY: Routledge.

- Rabiger, Michael. 2004. Directing the Documentary. 4th ed. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Focal Press.

- Ray, Sandeep. 2021. Celluloid Colony: Locating History and Ethnography in Early Dutch Colonial Films of Indonesia. Singapore: National University of Singapore.

- Rolandsen, Øystein H. 2015. “Another Civil War in South Sudan: The Failure of Guerrilla Government?” Journal of Eastern African Studies 9 (1): 163–174; https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2014.993210.

- Ross, Corey. 2008. Media and the Making of Modern Germany: Mass Communications, Society, and Politics from the Empire to the Third Reich. Oxford, UK, and New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Ruby, Jay. 2005. “The Last 20 Years of Visual Anthropology – A Critical Review.” Visual Studies 20 (2): 159–170; https://doi.org/10.1080/14725860500244027.

- Russell, Catherine. 1999. Experimental Ethnography: The Work of Film in the Age of Video. Durham, NC, and London, UK: Duke University Press.

- Seifrit-Griffin, Stacie. 2022. From the National Film Registry: "Nanook of the North" Released 100 Years Ago. Accessed from Library of Congress blogs; https://blogs.loc.gov/now-see-hear/2022/06/from-the-national-film-registry-nanook-of-the-north-released-100-years-ago/

- Stanford, Eleanor. 2001. “Sudan.” In Countries and Their Cultures, edited by Melvin Ember and Carol R. Ember, 4: 2100–11. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA.

- Tagg, John. 1988. The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories. Basingstoke, UK, and New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tomaselli, Keyan G. (ed.). 2018. Making Sense of Research. 1st ed. Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik.

- Vailati, Alex, and Gabriella Z. Villarreal. 2021. “Introduction.” In Filming Real People: Ethnographies of ‘on Demand’ Films, edited by Alex Vailati and Gabriella Z. Villarreal, 1–25. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vidal, Belén. 2014. “Introduction: The Biopic and Its Critical Contexts.” In The Biopic in Contemporary Film Culture, edited by T. Brown and Belén Vidal, 1–32. New York, NY, and Oxford, UK: Routledge.

- Woolley, Anna E. 2022. “Nanook of the North: One Hundred Years on.” Film Review. Routes 3 (1): 139–148.

FILMOGRAPHY

- de Mabior, Akuol, dir. 2023. No Simple Way Home. Kenya and South Africa: LBx Africa and STEPS.

- Flaherty, Robert Joseph, dir. 1922. Nanook of the North. United States: Pathé Exchange.

- Flaherty, Robert Joseph, dir. 1926. Moana. USA: Paramount Pictures.

- Lang, Fritz, dir. 1931. M Le Maudit. Germany: Vereinigte Star-Film GmbH.

- Murnau, F.W., dir. 1922. Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror. Germany: Film Arts Guild.