Abstract

The study of one of Cameroon’s first permanent photo studios, Photo George in Douala, reveals a story of migration, social mobility, intellectual ambition, and a special ability to adapt to a challenging economic, political and social situation. Tracing the studio founder’s family history back to the mid-19th century and considering Freetown’s multicultural Krio society with its longstanding interactions with photographic practices, not only tell how George E. Goethe turned his father’s intellectual and academic ambitions into a pursuit of visual perfection but more generally allow a glimpse into how photography as a profession spread along the West African coast.

EARLY AFRICAN PHOTOGRAPHERS

The first “contact zones” for Africans with photography, to use Marie Louise Pratt’s term (Citation1994) somewhat differently, were private homes, official buildings and personal photo albums in which missionaries, travelers and traders displayed photographs they had brought from Europe or, if available, had commissioned locally. In this way, they saw what to do with photographs (Schneider Citation2023, 14–35). The internationally well-connected African elite in the coastal cities of West Africa readily adopted this practice, so that the first governor of Cameroon, Max Buchner (Citation1887, 54), could report in the late 1880s, that “in the state room of King Akwa hangs a large photograph of his father.” As for photo albums, the merchant John Whitford wrote (Citation1877, 299) about a visit to King Eyo in the Niger Delta, when the king showed him “with pride a photo album,” and Max Buchner (Citation1914, 40 ff.) told his readers of similar experiences. The other way to get in touch with photography was to see or experience a photographer taking pictures either outdoors or in a studio, standing behind a tripod with a dark cloth over his head. In this way many Africans saw how photographs were made, although posing and exposing were of course only the first step in a longer process that continued in the darkroom.

How the first African photographers encountered and learnt the new image technology must remain a matter of speculation (Geary Citation2010, 86–99), but at least we have a clearer idea of who they were and what their social or family backgrounds were. Scholars such as Vera Viditz-Ward (Citation1985, Citation1987), Christraud Geary (Citation2010), and Tobias Wendl (Citation1998) have pointed to the cosmopolitan background of those first photographers, to their mixed African-European origins, to the Creoles, descendants of African slaves in Freetown, Sierra Leone, and in other West African port cities. No wonder then that virtually all of the first African photographers bore such European names as Decker, Joaque, Lewis, Lutterodt or Sawyer.

ROOTS IN SIERRA LEONE

The story of Claude Adolphus George and his son, George E. Goethe, founder of the Photo George studio in Douala, fits well into this framework. Although this family is special in many ways, their story is much like many other family stories in West Africa—one of migration, adaptation and integration. George E. Goethe was born on 16 Aug. 1896 in Freetown, Sierra Leone. He was christened George because his father’s name was Claude Adolphus George, so the father’s surname became his first name. The “E” came from “Esu Biyi”, the name his father adopted in the early years of the 20th century, which George later added to his name (Spitzer Citation2010, 26). Furthermore George was given the surname Goethe because his father, it is still said in the family today, greatly admired the German poet, playwright, novelist and natural scientist. Others did too: for example, half a century later one of the founders of the Négritude movement and eventually the first President of independent Senegal, Léopold Sédar Senghor.Footnote1

One might wonder how close the grandson of a recaptive, a slave who was freed by the British anti-slavery squadron patroling off the African coast and was subsequently settled in Freetown, came to know of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and German culture in Sierra Leone during the second half of the 19th century. But we must not forget that there were German missionaries working on behalf of the British missions in Sierra Leone at that time. Furthermore, George Henry Lewes, common-law husband of the famous novelist George Eliot,Footnote2 published The Life of Goethe in Citation1855, probably the best known of his works today. That book was well-known in Germany itself at the time–a translation appeared in 1857–and was an indicator of British interest in German culture in the mid-1800s.

Assuming that Claude Adolphus George was 30 years old (i.e. born in 1866)Footnote3 when his son was born, he was too young to be a recaptive himself, as the last intercepted slave ship had entered Freetown harbor on Christmas Day 1863 (Anderson Citation2020, 220). That being the case, George E. must have been of the second or even third generation since his father or grandfather was liberated by the British and settled in Freetown. But the awareness of having his roots elsewhere, in Nigeria and in Yoruba culture, did not disappear over the generations, and in the context of a larger renaissance of African identity or a movement of “cultural nationalism” in the last decades of the 19th century, he changed his name to Esu Biyi. This was entirely in line with the “resurgence of Yoruba naming and dress” noticeable among former slaves in the British colonies of West Africa in the 1880s.Footnote4 It was a move to strengthen their own African identity and at the same time get rid of the stigma of oppression and slavery–the slave name–that runs like a thread through the entire history of Black Africans in Africa, but also in the United States. (Malcom X is probably the best-known example of such an erasure and restoration of Black African identity; Shakur Citation2001, 23, 184–86; Fujino Citation2005, 179.)

In 1902 Claude A. George changed his name to Esu Biyi and from then on published under that name. Esu is an important primordial deity in Yoruba belief (Falola Citation2013). By choosing Esu Biyi as his new name—which means “priest of Esu”—Claude George expressed not only his desire and determination to reconnect with his ancestors and origins, but also to serve and be a servant in the universe of Yoruba deities.Footnote5 At the same time, Claude A. George remained firmly connected to the world that had given him an education and a job. He was in government service (in the Colonial Secretary’s Office) in Sierra Leone in the years around the turn of the 19th to the 20th century, and during this time, and with access to official sources, he wrote his 468-page study The Rise of British West Africa. Comprising the Early History of the Colony of Sierra Leone, etc., which was published in 1904 in Britain. Six years earlier, “the substance of a lecture delivered by Mr. Claude George before the City Club, Sierra Leone” (Westminster Review Citation1898, 150: 108) had been published, again in Britain, under the title Unity in Religion: an Inquiry into the Teachings of the Great Religions of the World (George Citation1898).

Almost certainly he had received all his education in mission schools in Freetown. We know that he attended the famous Fourah Bay College there, which was then affiliated to the University of Durham in the north of England. He passed his final examinations in theology during 1907 and took his License in Theology at Fourah Bay in Sierra Leone on 26 Sept. 1908.Footnote6 By then his son George E. Goethe was almost 12 years old.

Although not a recaptive himself, he and his father fell in line with what Jean Herskovits Kopytoff wrote in her study of the role of Sierra Leonean migrants in the early history of modern Nigeria. “On the West African coast,” she argued, “the first generation of Africans with any Western education came from one of two principal sources–the captured slave ships, whose human cargoes were released to start a new life in the English colony of Sierra Leone; or the New World, from which they made their way back to their continent of origin.” And in keeping with George Goethe’s family background, “As the century wore on, liberated Africans, especially from Freetown, became prominent in aiding the spread of European influence—direct or indirect; political, religious, or economic—from the Gambia to the Cameroons” (Kopytoff Citation1965, v).

The Swiss Bernhard Gardi, who interviewed the last owner of the photo studio, namely George E. Goethe’s son, Cyrille Dualla Goethe, in 1995, learned that Cyrille’s grandfather had studied theology, history and geography at Oxford University and had taught in the Anglophone port cities along the West African coast. He had also published several books. This, as we have noted, was only partially true. In the same year that his second book was published (Citation1904), he became a member of the Royal African Society under the name of Esu Biyi, and published three ethnographic papers in the Society’s journal over the next two decades (Citation1913, Citation1929, Citation1930).

DOUALA, CAMEROON

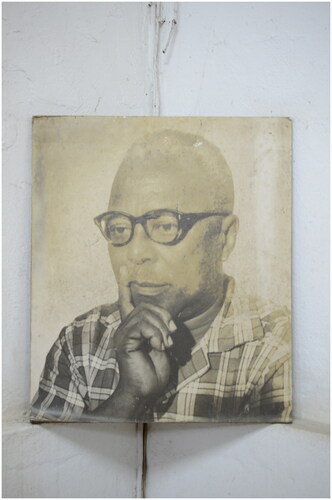

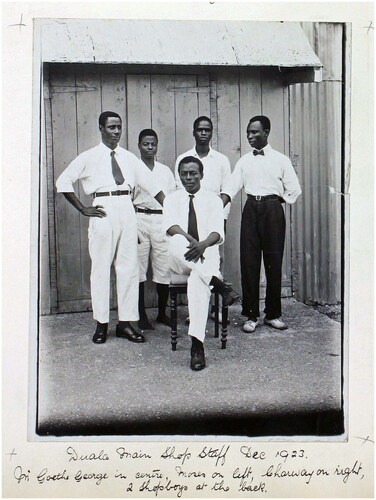

Scattered in various sources are fragments that tell us something about the life of his son George E. Goethe. Jonathan Derrick (Citation1979, 215) was lucky to meet and interview him before his death on 10 Jan. 1976, and wrote about the “best known immigrant to Douala” in the 1920s and 1930s: “He went to school in Sierra Leone and Liberia, but ran away, tried to stow away to England and was sent back. After ‘trying everything’, he went to work for John Holt in Gabon. From there he went in 1923 to Douala, where he also worked in the local office of John Holt, under Mr. Teale and Mr. Parsons” (). If this information is correct, then he must have been a pretty wild fellow.

Figure 1 Douala Main Shop Staff, Dec. 1923. George Goethe in the center, Moses on the left, Lharway on the right, two shop boys at the back. (Photographer unknown. Courtesy of Liverpool Central Library and Archive).

Bernhard Gardi was told that a first marriage in Gabon had failed and that George Goethe arrived in Douala in 1922. His son Cyrille confirmed Derrick’s information and the date of his father’s arrival from Gabon, precisely in March 1923, adding that he had come to Douala with the company’s promise to succeed the acting director after that man’s departure. This promise was not however kept: after the director had left he was succeeded by another White man, and after him, yet another White man followed. Frustrated and feeling cheated, George Goethe left John Holt and turned to photography (C. Goethe Citation2000, 5). That was in 1931.

According to the journalist and photographer Samuel Nja Kwa (Citation2004, 141–45), George Goethe had already arrived in August 1922 and had started taking photographs in and around Douala, awaiting his order of assignment (ordre de mission). That order did not come but a pension was paid, enabling George Goethe to concentrate entirely on his passion. Equipped with an official permit and his camera he traveled the hinterland, photographing landscapes and people.Footnote7 He then decided to stay in Douala and continue his business as a photographer. He soon married Christine Etonde, a Cameroonian, with whom he had five children, one of whom was to become his successor, Cyrille Dualla Goethe.

We do not know why George Goethe started taking photographs nor where he had learnt to do so. Of course, he must have enjoyed it, and perhaps he had already familiarized himself with the technique in Sierra Leone or somewhere else where he had been before arriving in Douala; but above all there must have been a market for photos and he must have sensed a business opportunity for a young enterprising photographer.

Having lived in Sierra Leone until he was 16 or 17 he had grown up in a country where photography already had a long tradition. There were some photographers in the 1860s and 1870s active on the West African coast, but they “rarely ran their own studio from one single location but instead traveled along the coast, advertising their services in the largest coastal towns and cities.” However, “in the late 19th century the number of photographers increased significantly” (Schneider Citation2018, 33). For instance, according to the 1911 Census Report for the Gold Coast colony there were 31 photographers working there in that year.

The photographers known to us by name in Freetown in the 1870s and 1880s were T.S. Thorpe, Shadrack Albert St John, Nicholas May, Ebenezer Albert Lewis, Dionysius Leomy and J. Nutwoode Hamilton. Unfortunately there is still little information available about them, especially on how far their careers reached into the 20th century. Then there was W.S. Johnston, who was active from the 1880s and had a permanent studio from 1893 (Geary Citation2010, 89); as well as Alphonso Lisk-Carew, who opened a studio with his brother Arthur between 1903 and 1905. They already “belonged to the second generation of Sierra Leone photographers” (idem). Indeed, ‘Freetown, settled by Creoles, descendants of African slaves who had returned to the continent from North America, Great Britain, and the Caribbean’ as well as slaves liberated by the British anti-slavery squadron “was … one of the first places [in west and central Africa] where [local] photography thrived” (idem).

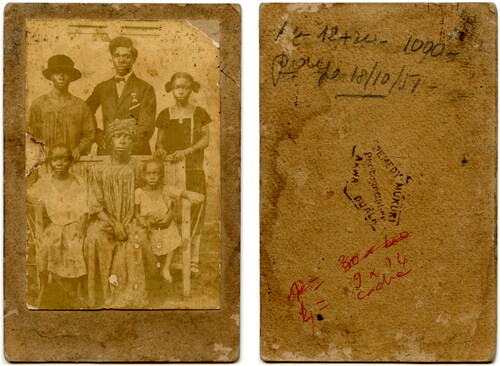

What do we know then about the situation in Cameroon or more precisely at Douala in the 1920s and 1930s, when George Goethe started taking photos and opened his studio? How many commercial photographers (i.e. people offering photographic services outside their immediate circle of family and friends, and doing so as a commercial service) were working there, and how many studios were there? From the 1870s onwards, itinerant photographers traveled through Douala and the Cameroonian coast—such as the Lutterodts or the above-mentioned W.S. Johnston. One early local photographer in Douala was William Mudisa Bell, who almost certainly belonged to the well-known Bell family, but there were several others around the turn of the century (Zeitlyn Citation2019, 312–14). For the period 1865–1916, David Zeitlyn (ibid., 312–16) cites the names of Gerard Lutterodt and relatives (1870s–1890s), William Mudisa Bell (active 1890–1910), King Njoya and entourage (who was not actually a commercial photographer), Anjo Dick (pre-1913), A.T. Monor Lawson (1910s –1930s), and Yemedi Mukuri, who I believe was active in at least the 1910s and 1920s ().

Figures 2 and 3 Studio portrait, front and backside. Photographer Yemedi Mukuri, Akwa, Douala. No date, probably 1920s. Courtesy of African Photography Initiatives (APhI)

There were also the Lebanese Moukarim brothers, who came to Cameroon around 1905. They produced postcards with their own photos around 1914, but did not take photos for third parties. Zeitlyn is convinced, however (ibid., 337 fn. 4), that further research will bring even more early photographers to light.

For the period when George Goethe () opened his studio in the early 1930s, there is hardly any more information about other photographers.Footnote8 Lawson was probably still active, but according to a government survey in Southern Cameroon, there were only three photographers working in 1928 (ibid., 318–19; Douala though was not included in this survey). In addition, the general retailers run by Europeans also offered photographic services, and some produced postcards with local scenes and motifs. Following the book Mit Pinsel und Palette durch Kamerun by the German painter Ernst Vollbehr (Citation1912, 9) the Basel Mission’s Shop in Douala already offered cameras as well as the additional equipment needed, such as glass plates and probably chemicals, in 1912.Footnote9

Another indicator is the number of business licenses issued in Douala in 1930, which amounted to 11 for photographers (Derrick Citation1979, 380). Here too Zeitlyn offers a caveat, because “it is absolutely certain that these figures are underestimated. Those who acquired the commercial licenses (patentes in French) were the success stories, those with permanent studios that could not escape the attention of the authorities” (Citation2019, 323). These considerations suggest that there was undoubtedly some supply of photographic services in the city at the beginning of Goethe’s career as a photographer, and we can assume as well that there was an appetite for studio portraits among a growing segment of the population who were integrating this new form of visual expression into their habits and social practices. Be that as it may, Goethe was successful with his business, and he earned enough money to be one of the first Africans in the city to own a car, a small Fiat (according to information Bernhard Gardi received from Cyrille Dualla Goethe in 1995; Cyrille could not however remember whether this was before or after the Second World War).

From the beginning George Goethe’s camera-work was not limited to the studio, as he photographed the interesting places of his city, traveling into the hinterland as far as Fumban and even further north. In the 1930s his pictures were printed in magazines such as Cameroun-Togo, Annales coloniales or Le Monde coloniale illustré.Footnote10 His mobility was an advantage over his competitors, and given the bulky equipment that still burdened the photographer we cannot help but admire his energy and entrepreneurial spirit. His outdoor photographs can be dated precisely to the 1930s, as they have survived as reproductions in various magazines and on postcards.

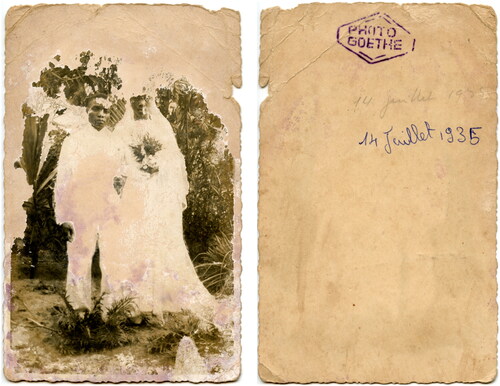

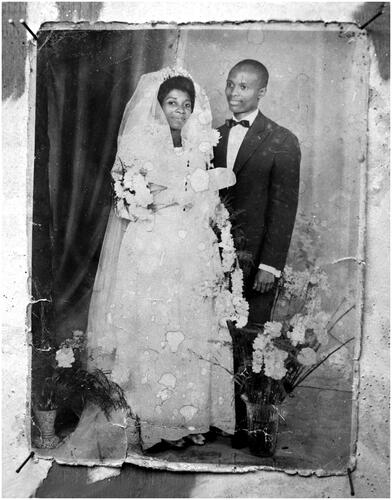

One surviving testimony to his early work as a portrait photographer (which is unfortunately in an extremely pitiful condition) dates from July 1935 () and shows a newly married couple photographed outdoors. In those early days he marked his photos with a simple stamp, “Photo Goethe.” Regrettably many of his early studio and portrait photographs have been lost (although some resurfaced if they were returned to the studio to be re-photographed), and a moving of the studio probably in the 1950s led to the disappearance of much of the archive. The first studio “Goethe E. George” was located at the Avenue Poincaré (today Boulevard de la Liberté), but later “Photo George” moved to the Rue Castelnau. Both streets are in the busy Akwa quarter close to the harbor ().

Figures 5 and 6 Portrait of a newly married couple, front and backside. Photographer George E. Goethe, no place, probably Douala, 14 July 1935. Courtesy of African Photography Initiatives (APhI)

Even today there are numerous postcards in circulation and available on the internet that were printed from George Goethe’s photos. In this regard a collaboration was arranged with a certain M. Sautot, the owner of a bookshop in Douala, who had the postcards printed in France. Other “Cliché Goethe George” postcards were published by the Société des missions étrangères de Paris and printed by Braun & Cie in Mulhouse-Dornach, in Alsace. In 1995 the postcards were still for sale in the photo studio, and Gardi bought 14 of them (for 3,500 CFA). They were “all damp, smelled bad and were often pitted,” he wrote. When I visited the studio in 2011 there was still a large cabinet with hundreds of postcards. Some props seen in the studio’s old portraits were still there too, as were photo lamps and on the wall the painted photo background, the studio’s trademark. On that occasion I was given a handful of postcards as a gift. Their condition had not improved over the years, but neither had it deteriorated.

FOOTBALL

George E. Goethe is not only remembered as one of the earliest Cameroonian studio photographers (Zeitlyn Citation2019, 316), but also as the one who introduced football in Cameroon. Whether this is true or not, he was undoubtedly an important and early promoter of the sport and one of the founders of the Union sportive indigène de Douala in 1926, together with Ebole Bile and Mpondo Dika. The Union was made “official” in the early 1930s with a committee of four Europeans (including Charles Lalanne as secretary) and four Africans. Lalanne was a French businessman and Secretary General of the Chamber of Commerce from 1928 to the early 1930s (Derrick Citation1979, 414).

The history of football in Cameroon is confusing, and there is a lot of divergent, sometimes contradictory information, mostly without sources, about when and where each club was founded. The Union sportive indigène de Douala (mentioned above) came into being in 1934, the same year as the Union sportive indigène de la région de Yaoundé, according to Peter Alegi (Citation2010, 24). Cyrille Dualla Goethe dedicated a short text L’introduction du football au Cameroun to his father, “le pionnier du football camerounais […] le tout premier introducteur et initiateur” (C.D. Goethe Citation2000). His story begins in 1923, when his father played football every evening with his cousin Romaine in Rue Castelnau; and a year later the Union sportive indigène de Douala was founded.

Whether from the mid-1920s in Cameroon, as an article in the magazine Togo-Cameroun claimed, or as late as the 1930s, the sport of football spread and established itself in colonial Africa well before the Second World War, “as one of the sites of African conviviality and one of the centers for the spread of anti-colonial nationalism among the emerging indigenous bourgeoisie” (Bancel Citation2010, 94–97).Footnote11 Unfortunately we know nothing about George Goethe’s political leanings or his possible political involvement during the years he spent in Douala—a turbulent time when the country, dynamized by the catastrophe of the Second World War, broke away from the French mandate and became the independent République Féderal du Cameroun, and after 1972 the République du Cameroun. However, we know that his son Cyrille was very much interested and involved in the politics of his country.

THE SUCCESSOR

Cyrille was born on 1 Feb. 1935; his grandfather was then approaching 70 and his father was 39. Much later, in 2013, Cyrille proudly mentioned in a short, handwritten note that he was among the first to be born in Douala’s newly opened Laquintinie Hospital.Footnote12 Born around the time his father had started doing photography, Cyrille literally grew up with the studio. While he went through a classical middle-class school training and attended those schools that were possible for an African at that time, Photo George flourished and became the place where citizens of Douala and their families were photographed on special occasions. Even today there is hardly a long-established middle-class family in Douala that does not have several photos from this studio in their albums. At the exhibition “Portrait d’un studio. Photo George, Douala,” that was held in honor of George and Cyrille Goethe in Douala in early 2016, many visitors recalled the studio backdrop hanging in the exhibition hall and their past visits to the studio, alone or with their families.Footnote13 In its best days the studio had employed several photographers, laboratory and office staff, and over the years trained some of Cameroon’s future photographers, such as Nicolas Eyidi, Martine Victoire Manga, Nteppe Ebeny, Jacques Ella, Loko Petit, Juste Zannou, Roger Nganji, Jean-Claude Mba or one Eboumbou Dalle Martin who, according to his nephews, even gave one of his sons the name Goethe.

The following information comes from interviews conducted with Cyrille between 2012 and 2016, as well as from a text published by the Cameroonian journalist of Ici les gens du Cameroun, Miriam Fogoum, in 2011, also based on an interview.Footnote14 As is so often the case with two different sources of information originating from the same person, there are some inconsistencies, probably due to the fading memories of an almost eighty-year-old man.

Cyrille attended secondary school in Akwa from 1947 to 1953 (in one interview he said primary school, but that is hardly possible) and then the Lycée Leclerc in Yaoundé, Cameroon, from 1953 to 1954. To Fogoum he revealed (my translation), “I wanted to be a philosophy teacher because I loved literature. I could read and summarize a three-hundred-page treatise in one day.” However, his father insisted that he prepare to succeed him in the photo studio and so sent Cyrille to France for training, where he stayed from 1954 to 1962. As for his political views, he told us that at that time all Cameroonians in France were “Upécistes,” supporters of Ruben Um Nyobe’s radical, anti-colonial party Union des populations du Cameroun, which was banned by the French in mid-1955, and whose leader was assassinated in Sept. 1958. Cyrille could not however remember any prominent Cameroonian who was in Paris at the same time as he.

In 1954 he entered the École technique de photographie et cinématographie (ETPC) in Paris, which he attended for four years.Footnote15 An email exchange however with the Director of Communication and Development at the École nationale supérieure Louis-Lumière, the successor to the ETPC, could not confirm Cyrille’s participation: his name was not to be found among the graduates in the archives, but “he may have taken shorter courses such as ‘evening classes’ or he may have simply missed a grade and is therefore not included in the list of graduates.”Footnote16 The Brevet de technicien supérieur en communication, option photographie et reportage (BTS), which he told Fogoum he had received in 1959, cannot be found in the school’s archives either. Nor can a stay at the renowned Harcourt photo studio in the 16th arrondissement in Paris be confirmed, as the studio simply did not respond to my several emails.

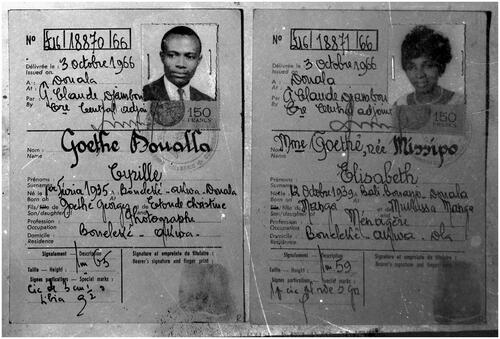

Cyrille returned to Douala in 1962, the same year that future President Paul Biya returned to Cameroon from France. In that year Cyrille married Elisabeth Missipo (), the daughter of a well-known Douala family, with whom he was to have four children: Théodore, Marlyse, Christine and Cyrille. All of them now live in France, and only Christine stayed behind and still lives on her family’s property in Rue Castelnau. Christine spent much of her childhood and adolescence with one of her mother’s aunts, Charlotte Missipo Manga, who had been married since 1940 to Théodore Lobè Bell, the chief of Bonanjo and head (between 1927 and 1951) of the Bell clan. When asked about his wife who had died a few years ago, Cyrille refused to talk about it because it was too sensitive and painful a subject.

Figure 8 Wedding photo of Cyrille and Elisabeth Dualla Goethe Missipo. (Very likely Studio Goethe, Douala, 1962; © Photo Studio George)

The marriage to Elisabeth Missipo () sealed the access and affiliation of the immigrant Goethe family to the inner circle of one of Douala’s most prominent families. The Bell clan’s willingness to open up to people other than the autochthonous Duala clans was confirmed when Jean-Paul Nyunaé, the son of a civil servant of the Bassa ethnic group who had worked his way up in the French colonial administration, and married a daughter of the Bell clan, Sissy Bell. Both had studied in Paris in the 1950s and 1960s and met there.

Figure 9 Identity document for Cyrille and his wife, issued on October 3, 1966. The document was reproduced photographically in the photo studio George and only the negative is still preserved. (© Photo Studio George)

Back to Douala from Paris, Cyrille confided to Miriam Fogoum that the government of Prime Minister Charles Assalé wanted him to work for them, but he had turned down the offer. Instead he joined his father’s business, becoming a newspaper correspondent for La Presse du Cameroun (now Cameroon Tribune) and also working for Agence France Presse (AFP) and Reuters. “I was a busy photojournalist,” he told her. “The others were either photographers or journalists, but I was both.” President Ahidjo was nevertheless still interested in his services and asked him, through Samuel Eboua, then head of the Cabinet, to accompany him on a mission to the Bakassi Peninsula. This territory was claimed simultaneously by Cameroon and Nigeria, and had been a sensitive political issue since the 1960s. It was only in the 1990s that the International Court of Justice ruled in Cameroon’s favor.

Cyrille Goethe was a journalist under President Ahidjo and then became MP for Wouri, a Department of the coastal province named after the great river Wouri; it covers the area around the major city of Douala, under Paul Biya from 1985 to 1990. After one term, he resigned from the Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement (CPDM), President Biya’s majority party, and joined the Mouvement Démocratique Populaire (MDP) of Samuel Eboua, who was head of the Cabinet under Ahidjo from 1975 to 1982. Eboua had left his post when Paul Biya, the Prime Minister under Ahidjo, took over as President after the latter resigned on 6 Nov. 1982 for health reasons. Cyrille, on the other hand, left the CPDM after Cameroon—like many other African countries—had returned to a multiparty system under increasing international and national pressure following the end of the Cold War.

While working in the studio archives between 2012 and 2016 to rescue and reorganize the precious material that had survived the years, not to mention bad weather and an unfavorable climate, I found many moments to talk to Cyrille (). It became quite obvious that his memories were not as much about his career as a photographer, as expected, and that he was quite careless with the photographic material in the archive. He appreciated the work done in the studio’s archives and felt honored by the exhibition that was organized in 2016 at the famous Doual’art exhibition hall and gallery, but he talked much more about his life as a politician. No one could have foreseen that Cyrille Doualla’s appearance at the launching of the exhibition in his and his father’s honor would be one of the last occasions he would be seen in public, for only a few months later he had died.

CONCLUSION

Listening to Cyrille answer a question about the studio archive or his work as a photographer only briefly, almost reluctantly, preferring to talk about his other interests and unfulfilled ambitions, confirmed that he would actually have much preferred to continue on the path his grandfather had taken. He had mentioned to Miriam Fogoum his interest in philosophy and literature, a field in which, as we have seen, his grandfather had been very active: he was an avid reader, but was forced by his father to become a photographer and continue running the studio. This is in fact a very common pattern: African sons who have to continue their fathers’ work, but who actually aspire to something else and are interested in other themes. But despite his reluctance, however strong or weak it was, he had little choice but to obey his father and continue running the studio. Obviously he has done this very well. Of course, we must not forget that the photos were not necessarily and not always taken by Cyrille himself, as several other photographers worked in the studio; but in any case he was responsible for the quality of the studio’s work, knew what a good photo looked like, and enforced these standards. Although he did not fully share our enthusiasm and passion for the photographs, nor our concern for the material survival of this studio’s work, which of course we had expected when we first met the prominent photographer and photo studio owner, he kept the doors of his home and his archives always open. Compared to experiences in other contexts, this was much more than might have been expected.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

I confirm that there are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jürg Schneider

Jürg Schneider is a historian and affiliated researcher at the Center for African Studies at the University of Basel, in Switzerland. His teaching, writing and curatorial activities are centered on the African continent’s rich photographic heritage and those who created it, especially in West and Central Africa. He is a co-founder of African Photography Initiatives, an organization working in and with photo archives in Africa. E-mail: [email protected]

Notes

1 http://www.uni-koeln.de/phil-fak/khi/senghor-projekt/download/Klingseis_Wagner_Leopold_Sedar_Senghor-die_Deutschen_und_die_Entdeckung_Goethes.pdf (accessed March 2024).

2 George Henry remained officially married elsewhere, as he could not divorce, but he lived in an open relationship with her until death separated them decades later, in 1878.

3 Claude Adolphus George died at a great age in Douala in 1949.

4 On cultural nationalism, see Anderson Citation2020, 263 fn. 11, about the Orișa cult pages 207-226 and about Yoruba naming patterns pages 263-264. An example of a person informing the public about his change of name, from W.J. Davis to Orishatukeh Faduma, appeared in the Sierra Leone Weekly News several times in Aug. and Sept. 1887.

5 For a brief ethnographic sketch of the Yoruba, see Barnes (Citation1995). For a general account of Cameroon, see Feldman-Savelsberg (Citation2001).

6 Email communication with Stephanie Osborn, Alumni Relations Assistant in the Development and Alumni Relations Office, Durham University, June 2020. Durham University Calendar with Almanack, 1912–13, 265. Claude A. George is listed in the left column. http://reed.dur.ac.uk/xtf/view?docId=bookreader/DU_Calendars/1912-3/ducal1912METS.xml#page/1/mode/2up (accessed March 2024).

7 A permit issued in January 1931, which allowed him to travel second class on the entire Cameroonian rail network, is reproduced in Goethe (Citation2000, 13).

8 In 1926 Douala had approximately 19,600 inhabitants, 28,000 in 1933, 42,500 in 1938, 62,600 one year later, 39,000 in 1945 and 100,000 in 1950. Figures taken from Zeitlyn (Citation2019, 330, Table 7) which he compiled from various sources. It should however be kept in mind that there is a high level of uncertainty about historic population figures.

9 The Basel Mission (Basler Missionsgesellschaft) was unique among 19th-century Christian missions in giving training in photography to its candidate mssionaries while still in Basel, before they went overseas; this from the 1860s onwards.

10 Cameroun: Magazine trimestriel/présenté par l‘Agence économique des colonies autonomes et du Cameroun, octobre 1937, 23. Les Annales coloniales/Organe de la ‘France coloniale moderne’, Oct. 1938, 6; Feb. 1939, 6. Le Monde colonial illustré/Revue mensuelle, commerciale, économique, financière et de défense des intérêts coloniaux, Jan. 1933, 68. Togo Cameroun: magazine mensuel/présenté par l‘Agence économique des territoires africains sous mandate, Autumn 1931, April and July 1932, Jan., April and July 1936. Concerning photographs in Togo-Cameroun see also Images & Mémoires – Lettre de Liaison, 16, by Philippe David http://www.imagesetmemoires.com/doc/Articles/L16_PhilippeDavid.pdf (accessed March 2024).

11 Togo-Cameroun magazine, “Le football chez les indigènes au Cameroun,” Oct. 1932, 295. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6216606c/f29.item (accessed March 2024). is cited in Frenkiel (Citation2019).

12 The hospital was inaugurated on 30 June 1934 and became operational on 1 Jan. 1935. Later his father told him that Doctor Julien was the hospital’s chief medical practitioner and his wife, Catherine, midwife. This Doctor Julien must have been Julien Vieroz and his wife Catherine Julien, née Prom. See Journal Officiel du Cameroun, 343, premier septembre 1934, 666 and 383, 15 April 1936, 357.

13 http://african-photography-initiatives.org/index.php/exhibitions/portrait-d-un-studio (accessed March 2024).

14 http://miriamfogoum.over-blog.com/article-images-hors-du-temps-86412358.html (accessed March 2024).

15 In 1937, l’École technique de photographie et de cinématographie (ETPC) was integrated into the Technical Education system and became the École des Métiers de la ville de Paris.

16 Email exchange with Méhdi ait Kacimi, Directeur communication et développement, École nationale supérieure Louis-Lumière, June 2021.

REFERENCES

- Alegi, Peter. 2010. African Soccerscapes: How a Continent Changed the World’s Game. London, UK: Hurst & Co.

- Anderson, Richard Peter. 2020. Abolition in Sierra Leone. Re-Building Lives and Identities in Nineteenth-Century West Africa. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Bancel, Nicolas. 2010. “Le succès du football dans l’afrique coloniale.” In Allez la France, Football et Immigration, edited by Claude Boli, Yvan Gastaut and Fabrice Grognet, 94–97. Paris, France: Gallimard – CNHI.

- Barnes, Sandra T. 1995. “Yoruba.” In Encyclopedia of World Cutures, edited by John Middleton and Amal Rassam, Vol. 9, 30–93. Boston, MA: G.K. Hall.

- Biyi, Esu. 1913. “The Temne People and How They Make Their Kings.” African Affairs 12 (46): 190–199; https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a099284.

- Biyi, Esu. 1929. “The Kru and Related Peoples, West Africa. Part I.” Journal of the Royal African Society 29 (113): 71–77.

- Biyi, Esu. 1930. “The Kru and Related Peoples, West Africa. Part II.” Journal of the Royal African Society 29 (114): 181–188.

- Buchner, Max. 1887. Kamerun. Skizzen und Betrachtungen. Leipzig, Germany: Duncker und Humblot.

- Buchner, Max. 1914. Aurora colonialis. Bruchstücke eines Tagebuchs aus dem ersten Beginn unserer Kolonialpolitik 1884/85. München, Germany: Verlagsanstalt Piloty und Loehle.

- Derrick, Jonathan. 1979. Douala under the French Mandate, 1916 to 1936. London, UK: PhD diss., School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

- Falola, Toyin. 2013. Èṣù, Yoruba God, Power, and the Imaginative Frontiers. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

- Feldman-Savelsberg, Pamela. 2001. “Cameroon.” In Countries and Their Cultures, edited by Melvin Ember and Carol R. Ember, Vol. 1, 384–396. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA.

- Frenkiel, Stanislas. 2019. "Les footballeurs professionnels Camerounais en France." Postdoc. research, Université de Lyon I, 14. Accessed March 2024; https://uefaacademy.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/06/20110506_UEFA-RGP_Stanislas-Frenkiel.pdf

- Fujino, Diane C. 2005. Heartbeat of Struggle. The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochyama. Minneapolis, MN, and London, UK: University of Minnesota Press.

- Geary, Christraud M. 2010. “Through the Lenses of African Photographers: Depicting Foreigners and New Ways of Life, 1870–1950.” In Through African Eyes: The European in African Art, 1500 to Present, edited by Nii O. Quarcoopome, 86–99. Detroit, MI: Detroit Institute of Arts.

- George, Claude. 1898. Unity in Religion: An Inquiry into the Teachings of the Great Religions of the World. London, UK: Swan Sonnenschein & Co.

- George, Claude. 1904. The Rise of British West Africa. Comprising the Early History of the Colony of Sierra Leone, Etc. London, UK: Houlston & Sons; Plymouth, UK: William Brendon & Son.

- Goethe, Cyrille Doualla. 2000. L'introduction du Football au Cameroun. Douala, Cameroon: Cyrille Doualla Goethe.

- Kopytoff, Jean Herskovits. 1965. A Preface to Modern Nigeria. The Sierra Leoneans in Yoruba, 1830-1890. Madison and Milwaukee, WI, and London, UK: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Lewes, George Henry. 1855. The Life of Goethe. London, UK: David Nutt.

- Nja, Kwa Samy 2004. “La Photographie Victime de Son Image.” Africultures 3 (60): 141–145

- Pratt, Mary Louise. 1994. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. London, UK, and New York, NY: Routledge.

- Schneider, Jürg. 2018. “African Photography in the Atlantic Visualscape. Moving Photographers – Circulating Images.” In Global Photographies. Memory – History – Archives, edited by Sissy Helff and Stefanie Michels, 19–38. Bielefeld, Germany: transcript Verlag.

- Schneider, Jürg. 2023. “Photographic Encounters. How Africans Saw Photography.” PhotoResearcher 40: 14–35;

- Shakur, Assata. 2001. An Autobiography. Chicago, IL: Lawrence Hill Books.

- Spitzer, Leo. 2010. “A Name Given, a Name Taken: Camouflaging, Resistance, and Diasporic Social Identity.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 30 (1): 21–31; https://doi.org/10.1215/1089201x-2009-047.

- Viditz-Ward, Vera. 1985. “Alphonso Lisk-Carew: Creole Photographer.” African Arts 19 (1): 46–51; https://doi.org/10.2307/3336382.

- Viditz-Ward, Vera. 1987. “Photography in Sierra Leone, 1850–1918.” Africa 57 (4): 510–518; https://doi.org/10.2307/1159896.

- Vollbehr, Ernst. 1912. Mit Pinsel und Palette durch Kamerun. Leipzig, Germany: List und von Bressendorf. [Facebook communication with Uwe Jung, Nov. 2015.]

- Wendl, Tobias. 1998. “Portraits et Décors.” In Anthologie de la photographie africaine et de l’océan Indien, edited by Jean-Loup Pivin and Pascal Martin Saint Léon, 104–117. Paris, France: Revue Noir.

- Whitford, John. 1877. Trading Life in Western and Central Africa. Liverpool, UK: The ‘Porcupine’ Office.

- Zeitlyn, David. 2019. “Photo History by Numbers: Charting the Rise and Fall of Commercial Photography in Cameroon.” Visual Anthropology 32 (3-4): 309–342; https://doi.org/10.1080/08949468.2019.1637683.