Abstract

In spite of a democratic governance model, due to cis-heteronormativity, the rights of incarcerated transgender women in Costa Rica are routinely undermined by pervasive direct, social and structural violence. In effect, their incarceration is often preceded by victimization in the public and private spheres. This paper will use in-depth interviews carried out with incarcerated transgender women to examine the social factors contributing to their vulnerability and the State’s responsiveness to their needs. This will be complemented by a socio-legal analysis of the current criminal justice framework. Finally, will examine if there is compliance with international human rights conventions

INTRODUCTION

“It is said that no one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails. A nation should not be judged by how it treats its highest citizens, but its lowest ones” (Mandela, Citation1994, p. 23).

In spite of the advances made in LGBTQI rights worldwide, transgender individuals remain among the most vulnerable groups in Central America. First, it should be noted that the term transgender is “an umbrella term used to describe people with a wide range of gender identities that are different from the sex assigned at birth” (Thomas et al., Citation2017). In general, transgender women face high levels of violence and mass incarceration (Hereth et al., 2020). In addition, due to pervasive transphobia, transgender individuals are subjected to multiple forms of violence within their families and by the rest of society (Connell, Citation2021). Moreover, the lack of a trans-inclusive perspective in Costa Rica implies that the State perpetuates their marginalization and eventually criminalizes them.

This investigation will use a case study analysis based on interviews carried out in four different prisons across Costa Rica with incarcerated transgender women. The objective is to examine the social factors contributing to their vulnerability and the State’s responsiveness to their needs. For this reason, the empirical research will be complemented by a socio-legal analysis of the current criminal justice framework. Finally, it will examine if there is compliance with international and regional human rights conventions during sentencing and the incarceration of transgender women.

It will investigate the case of Costa Rica, which is Latin America’s oldest democracy, to illustrate how despite a democratic governance model, the persistence of transphobia continues to undermine their human rights. Notwithstanding the commitment to international human rights and democracy, Costa Rica remains a cis-heteronormative state. It refers to “a set of norms and values that privilege the straight line between designated sex at birth and the corresponding gender, gender roles, and gender presentation” (Rodgers et al., Citation2017). Applied to the State, it implies that laws, institutions, and policies operate under the assumption that citizens are heterosexual and cisgender. Far from being protected by a democratic State, their needs and vulnerabilities are not taken into account. Within the larger social context, they are treated as threats to the public order (Galindo et al., Citation2017). As a result, transgender women have had to carve out spaces of resistance and survival.

CURRENT STUDY

Thus far, the situation of transgender women remains under-researched. Most of the research is from the Global North. The result is that the “regimes of knowledge in Trans* Politics” are dominated by the experiences of transgender individuals in the United States and Europe (Nay, Citation2019). Furthermore, the legal protections, political rights and medical and psychological regulations are mainly based on those adopted by public and private institutions in the Global North. Even the “reports and surveys” about transgender individuals are mainly from the Global North (Nay, Citation2019).

Notwithstanding the gaps in knowledge, it should be noted that the transgender movement is gaining ground in the Global North. For instance, in the United States, since the 1980s, the term “transgender” has become an “informal umbrella term, and a ‘collective political identity” (Taylor et al., Citation2018, p. 5). As a result of this political movement, there is growing awareness of transgender identities. There have also been notable advances regarding legal protections and policies (Taylor et al., Citation2018, p. 5). Likewise, in the European Union, LGBT rights have become an indicator by which “Europeanness” can be assessed. Given that the European Union is a supranational project, LGBT legislation and LGBT friendliness have become a means for creating a more regional identity (Slootmaeckers, Citation2020). To this end, the European Court of Human Rights and the Court of Justice of the European Union have established frameworks for transgender protection (Dunne, Citation2020).

In contrast, the research regarding the situation of transgender women in the Global South is limited. Gender is a social construct, which is often the result of specific social and political dynamics rather than biological truths (Freud, Citation1994). Hence, all the more reason to examine what this construct means in a specific social and cultural context. Transgender identities will be shaped by the social significance attached to gender. Because social context defines gender, this, in turn, affects how transgender women define themselves. In this regard, it is essential to “deconstruct the familiar perspective of gender as explained in binary opposition of Western understanding” (Ismoyo, Citation2020).

For this reason, it is vital to acknowledge local identity processes which inform social identities, the local institutional context which frames the pursuit of transgender rights, and the local socio-cultural context, which can either accept or reject a particular minority.

To begin with, the local identity processes in Costa Rica merit further research. It should be noted that regarding gender diversity, several terms refer to a person’s identity, such as transgender, third gender, polygender, pangender, and gender-fluid (Beek et al., Citation2016, p. 2). Given that social identities vary depending on the temporal and spatial context, the terms employed to refer to gender-diverse individuals reflect the local identity processes. For example, in this paper, the term ‘transgender’ will be used since it is the most frequently used by members of the community. In the Costa Rican context, some individuals identify using the term ‘trasvesti’. Even though this term is considered offensive in some cultural contexts (Nissim, Citation2018; see also, BBC, Citation2015), in Central America, it is sometimes “claimed by people assigned male at birth, who transit towards the female gender” (Human Rights Watch, Citation2020, p. 8). When used in this paper, it will appear italicized to indicate the current term selected by some individuals in Costa Rica.

In addition to exploring local identity processes, it is vital to examine the institutional context as well. The institutional context influences how transgender activism plays out. It will define the strategies used by transgender activists, and it will determine the degree of state responsiveness and State capacity when it comes to addressing those rights. For example, the rise in transgender activism in the United States is the result of grassroots organizations and alliances with gay rights groups, enabling the “incorporation into an existing social movement and its social movement organizations.” (Taylor et al., Citation2018, p. 37). Additionally, laws and policies governing transgender rights can vary depending on the State (Taylor et al., Citation2018, p. 253). For this reason, “the appellate courts have played a role in how federal agencies have interpreted the definition of sex in statutes and regulations” (Taylor et al., Citation2018, p. 235). Hence, it is a legal strategy based on the unique legal federalism that defines the United States and which builds on previous social movements’ victories. However, since Costa Rica has a different legal structure and social dynamics, this strategy is not applicable.

On a similar note, in Europe, the push for LGBT legislation reflects the supralegal structure which underpins the European Union. (Slootmaeckers, Citation2020). It is a legal strategy that relies on both appeals to a collective European identity and the influence of the European Union. It should be noted that Costa Rica is a member of the Organization of American States (OAS, Citation2021). Within the Interamerican system, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, are tasked with overseeing human rights. However, “its weakness lies in its lack of authority to enforce its recommendations” (Organization of American States, Citation2010). Subsequently, advancing human rights via regional integration is not as effective in Latin American.

Overall, in Costa Rica, much like the rest of Central America, the institutional context perpetuates discrimination against transgender individuals. However, it should be noted, an increasing number of countries have enacted laws recognizing transgender identities, such as Argentina, Colombia, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Uruguay, which have enacted laws recognizing transgender identity (REDLACTRANS, Citation2020). In contrast, in Central America, the protection offered to transgender rights is minimal (Campbell, Citation2019). To this end, Corrales (Citation2020) analyzed LGBT legislation from 1999 to 2016 in Latin America and the Caribbean. The study examined whether each Latin-American country had legislation recognizing gender identity, same-sex marriage, same-sex civil unions, and hate crimes. Given that Costa Rica does not recognize gender identity, adoptions by LGBTQI individuals, or have anti-hate crime legislation, it is among the countries with “modest improvements” (Corrales, Citation2020).

Then, in 2017, the Interamerican Court of Human Rights issued Advisory Opinion on Gender Identity, Equality, and Nondiscrimination of Same-Sex Couples (2017), OC-24/17. This prompted a backlash within Costa Rica. According to national polls, the support for the presidential candidate from a small evangelical political party rose from 2% to 24,79% shortly after the advisory opinion was released. As a result, he came in first place during the first electoral round. He ultimately lost in the run-off election (Nájar, Citation2018). Nevertheless, his rapid rise on the national stage demonstrates how LGBTQ rights are still contested at the social and political levels.

Overall, the socio-cultural context can either accept or undermine transgender rights and identities. The socio-cultural context influences cognitive processes, which, in turn, determine a collective worldview, including a shared sense of right and wrong. Ultimately, “morality is in part grounded in culture” (Taylor et al., Citation2018, p. 5). Thus, for example, the Costa Rican socio-cultural context is influenced by dominant Christian and Catholic beliefs. As a result, the social construction of gender is often informed by these religious beliefs. It should be noted that both Catholics and Christians adhere to a strict interpretation of the gender binary (Darwin, Citation2020).

According to the Center for Research and Political Studies (CIEP) from the University of Costa Rica, only a third of the population supports same-sex marriage (Murillo, Citation2018). In effect, the legalization of same-sex marriage was not so much a reflection of popular sentiment as it reflects Costa Rica’s commitment to international human rights. Although Costa Rica now recognizes same-sex marriage, it does not recognize transgender identity for men, women, or non-binary individuals. As a result, transgender and gender-expansive individuals are often rendered ‘’invisible’’ (Caravaca-Morera & Padilha, Citation2018).

LITERATURE REVIEW

The term “transgender” is attributed to the psychiatrist John F. Oliven, who coined it in 1965. Similarly, the term was popularized by Virginia Prince (Currah et al., Citation2006). From an academic perspective, the field of transgender research flourishes in the nineties. Accordingly, in 1994, Susan Stryker described transgender individuals as “people who move away from the gender they were assigned at birth, people who cross over (trans-) the boundaries constructed by their culture to define and contain that gender” (Stryker, Citation2008). She then published the seminal text Transgender History, which examines the experience of transgender individuals within the United States from the 1850s to the 2000s (Stryker, Citation2008).

In the decades since, within the United States, transgender studies “gained the status of a recognized field”. There are academic publications and university courses focused on transgender identities, experiences, and theories (Keegan, Citation2020). Currently, transgender research tends to examine identities within a social context, experiences within an institutional context and quantitative analyses of identities and experiences. (Schilt & Lagos, Citation2017).

Nevertheless, even in the United States, “little formal research on transgender prisoners exists” (Peek, Citation2004, p. 1218). In general, scholarship regarding incarcerated transgender women has focused on the role of patriarchy and heteronormativity within prison walls (Rosenberg & Oswin, Citation2015). Other studies have highlighted how incarcerated transgender individuals are subjected to “a shockingly inhumane daily existence” (Rosenblum, Citation1999). Moreover, research has proven that due to the prevalence of transphobia, transgender women are more likely to be incarcerated. Once incarcerated, their vulnerabilities are aggravated by prison conditions (Peek, Citation2004, p. 1218).

Regarding transgender women in Latin America, several studies have explored their identities, access to healthcare, motives for drug consumption, and experiences with violence in public and private settings. However, according to Loza et al. (Citation2017), “they were generally not the target population, or, if so, the sample included a number of different Latina nationalities and cultures.” Studying transgender individuals as if they were monolithic can be counterproductive because it erases the particularities of each cultural experience.

Furthermore, concerning incarcerated transgender women in Latin America, Johnson et al. (Citation2020) carried out An Exploratory Study of Transgender Inmate Populations in Latin America. Their work is noteworthy because it investigates the experiences of five incarcerated women in Nicaragua and El Salvador. In other words, the neighboring Central American countries. The study concluded that incarcerated transgender women experience multiple inequities and violence because of their identities. Moreover, it affirmed the need for research to examine “how the state shapes the experiences and violence faced by transgender persons” (Johnson et al., Citation2020).

In Costa Rica, there is scant information regarding the situation of transgender women. For instance, there is no record of how many transgender women are in Costa Rica. This is because the national census adheres to a gender binary. Likewise, it is difficult to determine the nature and pervasiveness of violence that trans people have suffered. There are no statistics on the subject that are disaggregated by the gender identity of the victim. Victimization surveys in Costa Rica do not disaggregate data based on gender identity (INEC, Citation2020). Additionally, there is no category of hate crimes in the Costa Rican criminal code, making it impossible to assess its prevalence. Lastly, the police do not keep a record of complaints filed by transgender people.

With regards to incarcerated transgender women, there is even less information. There are previous investigations about incarcerated cisgender women carried out by NGOs (Fernández et al., Citation2015), universities (Palma Campos, Citation2011), and state institutions (ICD, Citation2014). However, the abovementioned investigations are limited to the ciswomen's prison system. As a result, the experience of transgender women is not included. Since there is no legal recognition of their gender identity, they are sent to men’s prisons.

All in all, this investigation can contribute to the literature since it uses an intersectional lens to examine an extremely vulnerable group in a country that is often overlooked from an academic perspective. In this regard, it seeks to contribute to a gap in the literature. The paper will rely on a socio-legal analysis to appraise the current institutional and legal framework whose purpose is to guarantee the human rights of incarcerated transgender women. It will also examine if there is compliance with the human rights conventions on the topic. The legal perspective will be complemented by structured interviews with incarcerated transgender women in Costa Rica. Based on these interviews, the situation, vulnerabilities and needs of incarcerated transgender women will be explored.

METHODS

This paper seeks to explore the factors which have contributed to the incarceration of transwomen. Underlying an individual's incarceration are complex and interdependent social, political, economic, and legal factors. For this reason, the research explores the challenges (e.g., access to education, access to justice, access to work) faced by incarcerated transgender women in Costa Rica through empirical research.

Additionally, it also aims to provide a basic sociodemographic profile of incarcerated transgender women. Therefore, it was essential to explore their perspective regarding state responsiveness (or lack of) to their needs. To this end, they were asked about their experiences within the criminal justice system, the public education system, the security system, and the larger social context.

The research relied on mixed methods using structured interviews. An interviewer administered each questionnaire. All interviews were carried out in Spanish. Moreover, due to prison regulations, the interviews were not recorded. When requesting permission to enter the prison, we were only allowed to enter with printed versions of the questionnaires and pens. Hence, the interviewer would read aloud each question and then write down the answer provided by the respondent. After each question, the interviewee proceeded to the next. No follow-up questions were asked. There was a total of two interviewers: the authors of this paper. Each interviewer interviewed 8 participants each, for a total of 16 participants. Each interview lasted around an hour. The questionnaire consisted of 110 closed questions about nine main topics. For example, with regards to their education:

What is your education level?

Then, in the section regarding their work experience, the interviewees were asked the following:

What is the biggest obstacle to finding a job?

……. Lack of education

……. Lack of training

……. Discrimination due to transgender/gender-expansive identity

……. Other

These topics were selected using an intersectional lens. The intersectional perspective seeks to analyze the “multidimensionality’ of marginalized subjects’ lived experiences” (Crenshaw, Citation1989, p. 39). This approach allows for the exploration of the various intersecting forms of inequity faced by transgender women. Apart from gender identity, social characteristics like ethnicity, class and sexual orientation can also lead to discrimination. Indeed, “one’s actions and opportunities are structured by one’s placement along each of these dimensions” (Burgess-Proctor, Citation2006). The questions in the interview explored the past and present personal experience of respondents regarding the nine dimensions listed below:

Social background. Focused on childhood and family

Education. Examined their experiences with the educational system

Work experience. Focused on the level of insertion into the labor market

Identity. Analyzed self-identification, recognition of transgender identity by third parties and gender-reaffirming procedures

Vulnerabilities. Examined the prevalence of psychological violence, physical violence, sexual abuse, sexual violence, sexual exploitation, and economic violence

Public security. Analyzed how transgender women feel in public spaces, in the workplace and with regards to the national security apparatus (e.g., police officers)

Health. Examined mental health, drug consumption, VIH

Crime. Analyzed criminal antecedents and risk factors and causes of crime

Access to Justice. Focused on their experiences with the criminal justice system

These dimensions were selected based on a literature review of research that highlighted the many obstacles faced by transgender individuals. Given the lack of information regarding transgender women in Costa Rica, the aim was an explorative study. To this end, a comprehensive list of questions was developed. Moreover, this study is informed by the exploratory investigation by Loza et al. (Citation2017) about transgender women living on the US-Mexican border. The study highlighted the need for researching the unique obstacles faced by transgender women in each national and cultural context. Since the type of vulnerabilities faced by transgender women can vary depending on the context, it is critical to understand the challenges resulting from a particular social, institutional and political framework. For this reason, we opted to give the study a national focus, Costa Rica.

Likewise, the research was also informed by the exploratory research carried out in Nicaragua and El Salvador (Johnson et al., Citation2020), highlighting the need for more research about how the State responds to the situation of incarcerated transgender women. For this reason, in addition to analyzing multiple dimensions of vulnerability, the study will also explore how State policy either addresses or neglects their needs.

SELECTION OF PARTICIPANTS

Currently, transgender women do not have their gender identity recognized legally in Costa Rica. As a result, they remain unrecognized and thus unprotected. Their presence is not noted according to their chosen gender identity in the official records when entering the prison system, but according to the gender they were assigned at birth. For this reason, the prison authorities are unaware of the exact number of incarcerated transgender women. According to an investigation carried out in 2017, 31 transgender women were in the Costa Rican prison system (Meléndez Segura, Citation2018).

For the purposes of this investigation, once permission was obtained to visit prisons, we had to rely on snowball methodology. Each day we arrived at the prison, we showed the necessary permits, explained the nature of the investigation, and passed through the security check. Since the prison authorities do not record the number, location, or names of incarcerated transgender women, we had to ask the prisoners and the correctional officers for information.

Usually, the first point of contact was the front-door correctional officer. We asked them if they were aware of any transgender women currently incarcerated. Although prison guards seldom use the term “transgender”, they are aware of individuals who prefer to be referred to by a female name and have a feminine gender expression. Therefore, the guard would usually give us a name or two. Then, we would walk to the prison wing where this person was located. After interviewing them, we asked if they knew any other transgender women within the prison. In this regard, snowball sampling was used throughout. After the initial first point of contact via a prison guard, each informant was selected and interviewed through “contact information that is provided by other informants.” (Chaim, Citation2008).

Four prisons in four provinces, Alajuela, San José, Puntarenas, and Liberia, were selected. The objective was to gauge if there was a rural-urban divide. Thus, indicates each of the prisons visited, the province where it is located, and the number of transgender individuals interviewed.

Table 1. Prison visits.

During August 2019, structured interviews were carried out with sixteen incarcerated transgender women. The inclusion criteria were: (1) self-identified as a woman, a transgender woman, or any other gender-diverse term, (2) were assigned the ‘male’ sex at birth, (3) legal adults (i.e., 18 years or older), (4) currently incarcerated within the male prison system, (5) have been sentenced regardless of the crime. The exclusion criteria: (1) Individuals in pretrial detention were not included in the sample. Each participant was read out loud a consent form. This included information about the study's purposes, and it emphasized that their participation was confidential and voluntary. If they agreed to participate, they were asked to sign the consent form. It was then placed into a sealed manila envelope. It should be noted that all the participants were guaranteed confidentiality.

DATA ANALYSIS

Since this is an exploratory study based on 110 closed questions, data analysis involved evaluating a grid and then coding the answers. Once the sixteen interviews were completed, the results were first transferred from the paper questionnaires to a grid. To this end, an excel spreadsheet was used. Each dimension was given a separate spreadsheet. As a result, there were nine sheets overall. Then the answers to questions were inserted using a code. Since the questionnaire consisted of closed questions, the code was very simple (yes = 1, no = 0). To illustrate the analytical process, provides an example of the data analysis involving physical violence. The transgender women were asked if they had experienced physical violence from the age interval 0–9 years old, i.e., during their childhood. If the respondent said yes, the code was 1, and if the answer was no, the code was 0. Once all the answers had been inserted for the age interval (0–9), the codes were added. The result was 9 out of 16, or 56%.

Table 2. Data analysis example.

If the questions had multiple answers, the chart was divided into several categories. To this end, . provides an example of how the topic of public self-identification was analyzed. The question regarding public self-identification, the respondents answered transgender (n = 6), women (n = 6), gay (n = 1), travesti (n = 2) and transsexual (n = 1). In this case, based on their answers, five categories were established. Each one was analyzed individually. For instance, the first category, “transgender”, examined how many respondents publicly identified as transgender. The code was simple. If the respondents said yes, the code was yes = 1. If the respondents said no, the code was no = 0. The answers for that category were all added. Then, the same process was carried out for the next category, “women”, and so forth.

Table 3. Data analysis example.

RESULTS

The interviews provided a glimpse into the lives of incarcerated transwomen in Costa Rica. Their experiences and needs are at times rendered invisible. Although there is a growing awareness regarding the transgender experience in some countries, this is still lacking in Costa Rica.

In addition to the above, gender identity and sexual orientation do not have considerable weight when developing public policies and citizen security strategies. Indeed, “the sex binary has many negative effects on public policy” (Rosenblum, Citation2011). As it stands, the full impact of transphobic violence in Costa Rica is unknown. Subsequently, it is impossible to have a citizen security policy that is inclusive and nondiscriminatory. Since gender-based violence also affects transgender women, efforts to raise awareness and prevention measures should include them. At this time, the nature and extent of direct, structural, and cultural violence experienced by transgender people in Costa Rica are not fully known.

SOCIAL CONTEXT

The role of socialization agencies is crucial in the development of an individual. Based on social learning theory, individuals acquire certain attitudes, beliefs, and values from their peers and family. According to Akers (Citation2006), “neighbors, churches, schoolteachers, doctors, legal figures and authorities and other people and groups in the community (….) have varying degrees of influence.” In the case of Costa Rica, the abovementioned social actors adhere to a cis-heteronormative worldview. A clear example is the very vocal defense of “traditional” families by elected politicians, clergy, and activists in response to the increasing visibility of the LGBTQI community (Fattori & Quirós, Citation2019). In this context, “traditional family” implies a nuclear family composed of a cisgender and heterosexual man married to a cisgender and heterosexual woman and their children.

Regarding the social background of the incarcerated transgender women, it is worth noting that they were, on average, 31 years old. Only one of the people interviewed was a foreigner, and the remaining 15 respondents (94%), were born in Costa Rica. It is also worth mentioning that most of them were children of teen mothers, 11 respondents (68%). The average age of their mothers at the time of their first childbirth was 16 years old. In contrast, their father was 23 years old. On average, they had five siblings.

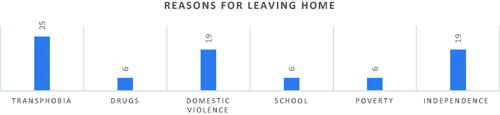

Many of the incarcerated transgender women have reported that their first experience of victimization happened within the family. On average, they left home at the age of 14. To examine this topic further, transgender women were asked the reasons for leaving home. illustrates their answers. When asked why they left their family home, 4 respondents, (25%), reported it was due to transphobic discrimination from their own family. For 3 respondents, (19%) it was due to domestic violence; for 3 respondents, (19%) it was because they wanted independence; for 1 respondent, (6%) it was due to drug consumption; for 1 respondent, (6%) it was due to poverty and for 1 respondent, (6%) it was to try to get a better education.

Access to Education

Education is frequently cited as one of the best pathways out of poverty (Awan et al., Citation2011). However, the education system is not a neutral actor in Costa Rica. Indeed, the public education system has become an ideological battlefield. Some activists have been campaigning to implement sexual education throughout the country, whilst others campaign to prevent it (Fattori & Quirós, Citation2019).

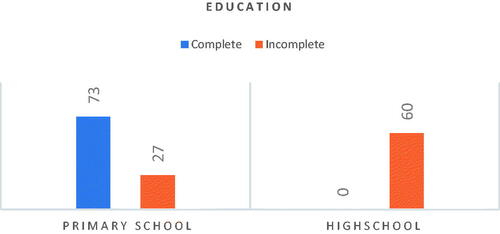

Given the importance of access to education, it was vital to explore the experiences of incarcerated transgender women. Accordingly, indicates access to education. In effect, 15 respondents (94%) of transgender women had access to formal education. However, only 11 respondents (73%) of the transgender women completed their primary school education. Although 9 respondents (60%) enrolled in high school, none completed it.

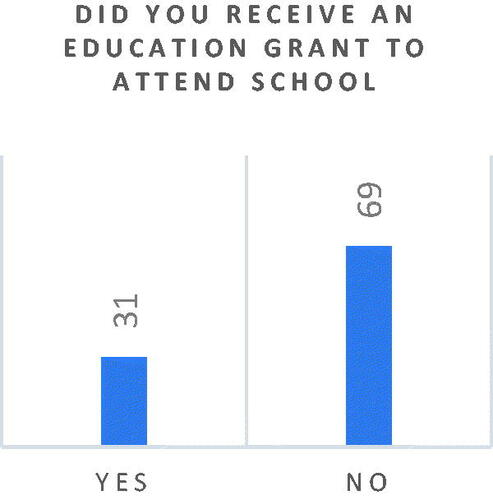

In the last fifteen years, Costa Rica has implemented education grants to assist students in completing their primary and secondary studies (Fondo Nacional de Becas, 2020). To this end, presents the data regarding education grants. Among the trans women interviewed, 5 respondents (31%) received an education grant to attend school. However, further research is required to explore why the grant is not reaching all the vulnerable groups.

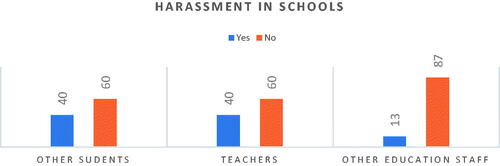

The transwomen were also asked about their day-to-day experiences with the school system. In the United States, LGBTQI students have reported higher levels of bullying and harassment than their heterosexual counterparts (Earnshaw et al., Citation2017). Regarding transgender students, (90%) of students reported been victimized at school, and more than (25%) reported physical assault (Domínguez-Martínez & Robles, Citation2019). According to a previous study about gay and transgender individuals in Peru, the majority reported homophobic and transphobic bullying in schools (Juárez-Chávez et al., Citation2021). The extent of harassment in schools is illustrated in . When asked about harassment during their time in school, 6 respondents (40%) of incarcerated transgender women reported being harassed by other students, 6 respondents (40%) reported being harassed by teaching staff, and 2 respondents (13%) reported harassment by other members of the school staff. It should be noted that both fellow students and teaching staff victimized the transgender students.

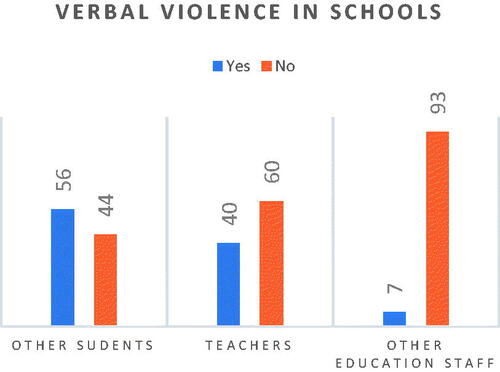

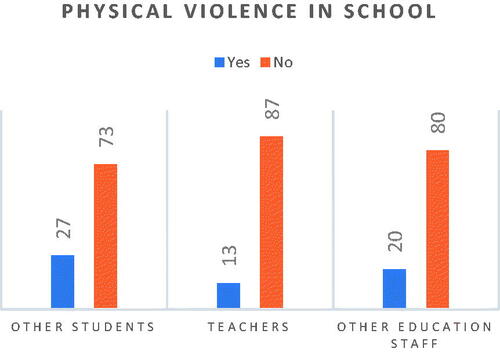

In order to explore this topic further, transwomen were asked about verbal and physical violence. illustrates verbal violence. When asked about verbal violence, 8 respondents (56%) reported being victimized by other students, 6 respondents (40%) by teachers and 1 respondent (7%) by other education staff. Then, shows physical violence. Again, the transwomen were mainly targeted by other students, with 4 respondents (27%). Then, 2 respondents (13%) reported being physically victimized by teachers and 3 respondents (20%) by other education staff.

Only one person interviewed felt comfortable going through official channels to report the harassment or violence. It reveals that schools have failed to guarantee the psychological or physical safety of transgender students in at least four different provinces. Further research is required to determine the types of victimizations, such as harassment and bullying, transgender students are subjected to in school. In addition, it is vital to examine how the nature of the victimization varies depending on the perpetrator. For instance, it is important to determine if there is a difference in the type of violence inflicted by other students compared to teachers and other staff.

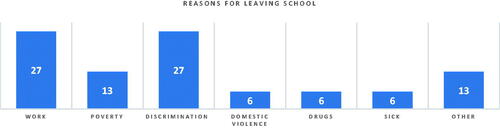

Given these circumstances, it is unsurprising that many transgender women are unable to complete their education. However, when asking them why they were unable to complete their education, the main reasons were transphobic discrimination at 3 respondents (27%) and the need to work at 3 respondents (27%). This was followed by poverty, 2 respondents (13%), domestic violence, 1 respondent (6%), drugs, 1 respondent (6%), sickness, 1 respondent (6%). To this end, exemplifies the reasons for leaving school.

Employment

Given that most transgender women interviewed leave home at a young age, they have to support themselves. Indeed, on average, they began working at the age of 15. Furthermore, transgender women face many difficulties obtaining work. According to a survey carried out in the United States, (44%) of transgender women were refused a job due to their identity. Moreover, even among those able to find employment, (50%) were harassed at work (DeSouza et al., Citation2017).

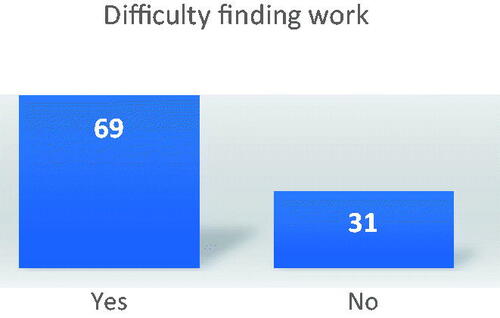

Article 33 of Costa Rica’s Political Constitution enshrines the principle of equality. It prohibits any form of discrimination because it undermines human dignity. At the same time, Costa Rica’s Labor Code, in its article 622, prohibits discrimination. Despite these legal protections, transgender women still face a great deal of difficulty finding work. For this reason, shows the percentage of transwomen who had difficulty obtaining work. It should be noted, 3 respondents (19%) reported they had never tried to find work in the formal sector. Then, 11 respondents (69%) reported they had had difficulty finding work.

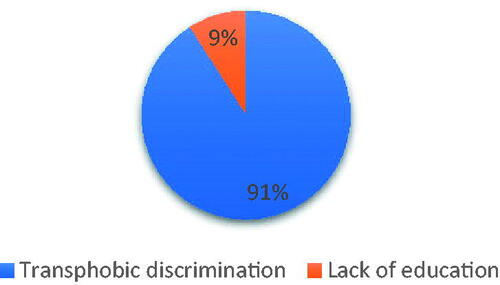

In addition, transwomen were asked why they considered they had had difficulty finding work. demonstrates the results. Of the women who reported difficulties finding work, 1 respondent (9%) stated it was due to a lack of education, and 11 respondents (91%), said it was because of transgender discrimination. Lastly, 14 respondents (88%) of the transgender women interviewed reported having had to engage in sex work. Given that transgender women have reported difficulty finding work and stated transphobic discrimination is the main obstacle, further research is necessary.

Identity

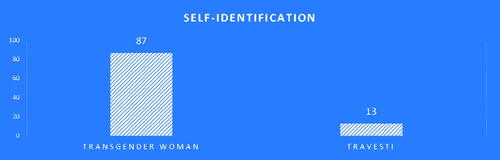

The question of self-identification is fundamental. indicates how the interviewed individuals self-identify. To this end, 14 respondents (87%) said they identify as transgender women. Then, 2 respondents (13%) reported they identified as ‘trasvesti’ because they “had not had any reaffirming procedures.” On average, they became aware of their gender identity at the age of nine.

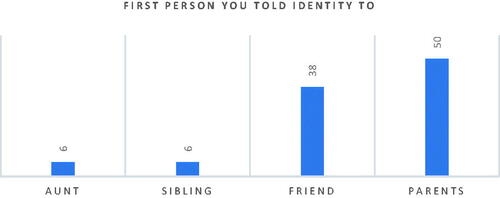

Nonetheless, not all the respondents shared their identity with their social circles. To this end, reveals the first person they told. Usually, it was a parent: 8 respondents, (50%) first told a parent, 6 respondents, (38%) first told a friend, 1 respondent, (6%) a sibling and 1 respondent, (6%) an aunt. When gauging the reactions of the first person with whom they shared their trans-identity, 8 respondents (50%) reported the reaction was positive, in 4 respondents, (25%), the reaction was confusion, 2 respondents, (13%), it was negative, and 2 respondents, (13%), it was neutral or indifferent. More in-depth research regarding the experiences they had when sharing their identities with others is necessary. In addition, it is vital to explore how having a positive reaction instead of an adverse reaction impacted their sense of self.

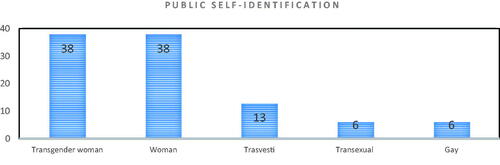

It should be noted that not all of them feel safe publicly identifying as transwomen. In general, transgender individuals have reported “repressing” their gender identity and feminine behaviors to avoid discrimination and violence (Juárez-Chávez et al., Citation2021). Indeed, shows their public identification. Accordingly, 1 respondent (6%) stated that even though they are a transwoman, they prefer to identify as a “gay man in the streets”. Similarly, 6 respondents (38%) identify as women without disclosing that they are transgender. So then, 6 respondents (38%) identify as transgender, 2 respondents (13%) as travesti and 1 respondent (6%) as transexual. On average, the individuals who publicly identify as transgender, transexual or travesti, have done so since they were 15 years old.

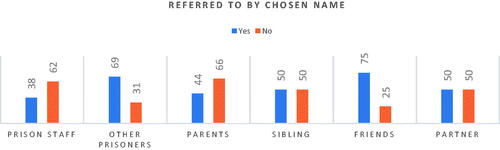

Given that a significant number of transgender women publicly identify as such, it was important to assess if others respect their identity. Hence, the women were asked if they were referred to by their chosen name instead of the legal name they were assigned at birth. indicates the number of individuals who are referred to by their chosen name. Accordingly, 6 respondents (38%) of the prison staff used their chosen name and 11 respondents (69%) of other prisoners, 7 respondents (44%) of their parents, 8 respondents (50%) of their siblings, 12 respondents (75%) of their friends, and 8 respondents (50%) of their partners.

Health

In Costa Rica, the right to health is enshrined in article 50 of the Political Constitution. In addition, there is the public health system. The Caja Costarricense de Seguro Social (CCSS) was established in 1941 to provide healthcare to workers (Vargas & Muiser, Citation2013). Then 1994, the public healthcare system was reorganized. Clinics named Equipo Básico de Atención Integral de Salud (EBAIS, or basic integrated health care team) were added to provide primary healthcare. Within twelve years, health coverage increased to 93% (Pesec et al., Citation2017).

In spite of the advances in guaranteeing healthcare for the general population, transgender individuals are still excluded. In this regard, Costa Rica is not an exception. Throughout Latin America, transgender individuals are very vulnerable due to a lack of access to healthcare (PAHO, Citation2014). Healthcare is conceived from a cisnormative conceptualization. Consequently, the specific health needs of transgender people are unknown and unaddressed. There is even a lack of experts with regards to trans health. Due to the lack of trans-inclusive techniques and procedures, their right to health is undermined.

GENDER REAFFIRMING PROCEDURES

In 2007, an application for constitutional redress was interposed when the CCSS refused to provide a gender reaffirming surgery. The CCSS refused because the operation was not required for health reasons and based on the administrative principle of legality. Since the institution was not expressly authorized by law, they could not provide it (Constitutional Court of the Republic of Costa Rica, 2007). Moreover, the Acting Director-General of Mexico stated under oath that the purpose of the services provided by the public healthcare system was to “cure and prevent illness, for this reason, aesthetic and vanity are not within the institutional objectives” (Constitutional Court of the Republic of Costa Rica, 2007).

The transwomen were also asked with regards to gender reaffirming procedures. This can refer to “hormone therapy, genital reconstruction, breast reconstruction, facial plastic surgery, speech therapy, urologic and psychiatric services and primary care” (Johns Hopkins Medicine, Citation2020). In general, transgender individuals have reported “high levels of satisfaction” in response to the gender reaffirming procedures (Van de Grift et al., Citation2018).

Regarding gender reaffirming procedures, 11 respondents (69%) reported they had used hormone therapy. Of the 5 respondents, (31%) have not had hormone therapy. All of them want to. Then, 4 respondents (25%) have had a gender reaffirming surgery. Of the 12 respondents, (75%) have had no surgical procedures, all of them want to. In effect, all transgender women have either had or would like to have a gender reaffirming procedure.

However, transgender women face a myriad of “structural inequalities” when trying to obtain healthcare. These include a lack of access to housing, a lack of access to work, and a lack of access to health insurance (Clark et al., Citation2018). As a result of these numerous barriers, their transition is often dictated by their limited economic means rather than their actual needs. Even those who could obtain a gender reaffirming procedure still lacked access to proper medical care. Only 4 respondents (40%) of the cases obtained the treatment from a doctor. The remainder went to an unlicensed third party.

DRUG CONSUMPTION

Previous studies have suggested there is a link between minority stress and drug consumption. Minority stress theory suggests that there are “stressors specific to sexual minorities”, such as social rejection due to widespread discrimination and internalized feelings of self-devaluation (Gonzalez et al., Citation2017).

When the incarcerated transwomen were asked about drug consumption, many stated it was a coping mechanism given their lack of family and social support. Overall, 15 respondents (94%) have used illicit drugs at one point in their lives. Of these, 4 respondents (25%) have received treatment or gone to rehabilitation for their consumption. In some cases, the women sought treatment from a state institution, the Institute of Drug Abuse and Alcoholism (IAFA, Citation2020). Others from Hogares Crea, a nonprofit that offers a rehabilitation program for free. It should be noted, all of the transgender women who sought treatment reported a lack of gender sensitivity during treatment. Indeed, many transgender women cannot obtain proper treatment due to minority stress and prevalent transphobic attitudes among the staff (Lyons et al., Citation2015).

MENTAL HEALTH

The transgender women interviewed were also asked about their mental health. In general, transgender individuals report more mental health issues than their cisgender counterparts (Streed et al., Citation2018). According to an investigation carried among transgender women in Brazil, there was a “high prevalence of psychiatric diagnosis, including psychoactive drug use, suicide attempts, major depressive disorder, psychoses, social phobias, and obsessive-compulsive behavior” (Fontanari et al., Citation2018). In the United States, 57% of transgender individuals have reported experiencing depression, and 42.1% have reported anxiety. According to previous studies, “transphobia-based violence is related to increased depression and anxiety” (Klemmer et al., Citation2021).

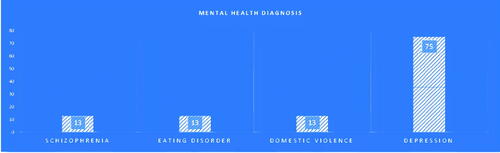

It should be noted that 8 respondents (50%) of transwomen have been referred to a psychologist. Then, 3 respondents (19%) have been referred to a psychiatrist. illustrates the mental health diagnosis transwomen have received. Of the transwomen referred to a medical practitioner, 12 respondents (75%) were diagnosed with depression. Costa Rica is not an outlier. As mentioned above, the prevalence of depression has been confirmed in other studies. Then, 2 respondents (13%) were diagnosed with an eating disorder and 2 respondents (13%) with schizophrenia. An additional 2 respondents (13%) were referred to a psychologist, not because they had a particular mental health issue, but to cope with domestic violence.

It was also essential to examine the prevalence of self-injury because this mental health issue is the least researched among transgender individuals (Jackman et al., Citation2018). The previous meta-analysis has been “consistent” in concluding that LGBTQI individuals are more likely to be at risk for self-injury than their cis-heteronormative counterparts. However, there is still a gap in the literature regarding the extent and nature of the phenomenon (Liu et al., Citation2019).

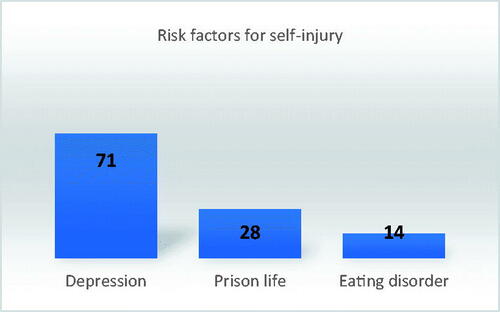

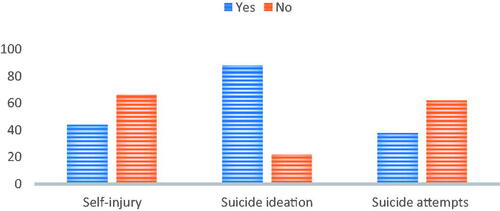

It should be mentioned that 7 respondents (44%) of the transgender women interviewed reported self-injury. This is reflected in . When asked why they hurt themselves, the transwomen identified three main reasons. Accordingly, as shown in respondents (71%) stated it was a coping mechanism for their depression, 2 respondents (28%) stated it was to cope with the hardship of prison life, and 1 respondent (14%) used it to cope with an eating disorder.

In addition, the transgender women were asked about suicide ideation and suicide attempts. Previous studies have indicated that transgender women are at higher risk of suicide attempts (PAHO, Citation2014). For instance, in a study carried in the Dominican Republic, “between one fifth and one-quarter of respondents had attempted suicide (22.5%)” (Budhwani et al., Citation2018). describes the prevalence of suicide ideation and suicide attempts. In effect, 14 respondents (88%) of respondents, experienced suicide ideation, and 6 respondents (38%) have attempted suicide at least once.

Given the vulnerability of transgender women, there is a need for more significant social and psychological support. At the group level, this means community-building. At the individual level, it implies tailored support to address the toll of enduring transphobia and any mental health issues so that transgender women develop a “positive self-concept” (Kuper et al., Citation2018).

Lastly, there is the topic of HIV. According to previous studies, transgender women are considered a high-risk group for HIV. Moreover, many of them are undiagnosed and lack access to treatment (Ragonnet-Cronin et al., Citation2019). Nevertheless, a hundred percent of the respondents stated they are routinely tested for HIV. Currently, 3 respondents (19%) are HIV positive, and they are receiving anti-viral treatment.

Vulnerabilities

Transgender women are among the most vulnerable social groups (Wilson et al., Citation2017). In Costa Rica, they are marginalized from a cultural, political, and institutional perspective. Some of them are born in a situation of social marginality. At times, they are the victims of abuse and intrafamilial violence. Then, without exception, they are the victims of multiple forms of violence due to transphobia.

It is not a phenomenon limited to Costa Rica. Previous research in Barbados, El Salvador, Trinidad and Tobago, and Haiti has demonstrated that transgender women face very high levels of violence (Evens et al., Citation2019). In addition to gender-based violence, transgender women have also experienced high levels of sexual abuse and intimate partner violence compared to their cis-heterosexual peers (Garthe et al., Citation2018).

VICTIMIZATION

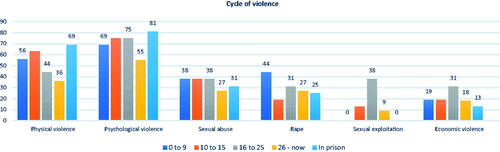

The participants were asked about their experiences with physical violence, psychological violence, sexual abuse, sexual exploitation, and economic violence to assess the different types of violence. The types of violence were defined using the legal terms in accordance with the Costa Rican Law of criminalization of violence against women, N° 8589. In addition, to evaluate the frequency of violence during their lifetime, the participants were asked if they had experienced it. Thus, represents the physical, psychological, sexual abuse, rape, sexual exploitation and economic violence experienced from the ages of 0–9, 10–15, 16–25, 26-now, and in prison.

PHYSICAL VIOLENCE

Physical violence is defined in article 22 of Law N° 8589. Physical violence refers to mistreating, hitting and any other physical harm. In a study among Latin American Transgender women in Washington DC, 92% were Central American migrants. Of the respondents, 76% reported experiencing physical violence during their lifetimes (Yamanis et al., Citation2018). As indicated in , from the age of 0–9, 9 respondents (56%) reported physical violence, from the age of 10–15, 10 respondents (63%), from the age of 16–25, 7 respondents (44%), from the age of 26-now, 5 respondents (36%) and in-prison, 11 respondents (69%). Although high levels of physical violence were experienced during childhood, the highest frequency has been during their prison term. It reveals that prison is a site of violence for most transgender women.

PSYCHOLOGICAL VIOLENCE

Psychological violence is defined in article 26 of Law N° 8589. It includes the “threats of violence, intimidation, blackmail, or harassment.” In a study among Latin American transgender women in Washington DC, 95% reported experiencing psychological violence during their lifetimes (Yamanis et al., Citation2018). As indicated in , from the age of 0–9, 11 respondents (69%) reported psychological violence, from the age of 10–15, 12 respondents (75%), from the age of 16–25, 12 respondents (75%), from the age of 26-now, 9 respondents (56%) and in-prison, 13 respondents (81%). The highest frequency has been during their prison term. Thus, it reaffirms that prison is a site of violence for most transwomen.

SEXUAL ABUSE

Sexual abuse is defined in article 30 of Law N° 8589. It implies forcing another person to endure “sexual acts that cause pain or humiliation”. According to the literature, LGBTQI individuals report experiencing high levels of sexual abuse (Grossman & D’Augelli, Citation2006). For example, in a study about incarcerated transgender women in California, 69.4% of respondents reported sexual victimization. For the study, it was defined as “including things they would “rather not do” (Jenness et al., Citation2019). As indicated in , from the age of 0–9, 6 respondents (38%) reported sexual abuse, from the age of 10–15, 6 respondents (38%), from the age of 16–25, 6 respondents, (38%), from the age of 26-now, 4 respondents, (27%) and in-prison, 5 respondents, (31%).

RAPE

Rape is defined in article 29 of Law N° 8589. It specifies that it refers to oral, anal, or vaginal penetration without the person’s consent. Given their social vulnerability, transgender women are at a higher risk of sexual assault (Seelman, Citation2015). According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics of the United States, one-third of incarcerated transgender women were sexually assaulted (Jenness et al., Citation2019). As indicated in , from the age of 0–9, 7 respondents (44%) reported rape, from the age of 10–15, 3 respondents, (19%), from the age of 16–25, (31%), from the age of 26-now, 6 respondents (27%) and in-prison, 4 respondents (25%). It should be noted that transgender women were most likely to experience rape as young children.

SEXUAL EXPLOITATION

According to article 31 of Law N° 8589, sexual exploitation is when a person is forced to have sexual relations for another person’s economic gain. More broadly, it can refer to “any actual or attempted abuse of a position of vulnerability, differential power, or trust for sexual purposes, including but not limited to profiting monetarily, socially, or politically from sexual exploitation” (Annan, Citation2003). Previous studies have demonstrated that transgender women report sexual abuse with more frequency than their cis-heterosexual peers (Rimes et al., Citation2019). As indicated in , from the age of 0–9, no respondents reported sexual exploitation; from the age of 10–15, 2 respondents (13%), from the age of 16–25, 6 respondents (38%), from 26-now, 1 respondent (9%).

ECONOMIC VIOLENCE

Economic violence is defined in articles 38–40 of Law N° 8589. It refers to “when a third party deducts earnings from an economic activity for their benefit.” It can also refer to when a person coerces a woman to give away her earnings or refuses to pay a person after providing a service or good. It can also imply “limited access to funds and credit” (Fawole, Citation2008). As indicated in , from the age of 0–9, 3 respondents (19%) reported economic violence, from the age of 10–15, 3 respondents (19%), from the age of 16–25, 5 respondents (31%), from the age of 26-now, 3 respondents (18%) and in-prison, 2 respondents (13%).

STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE

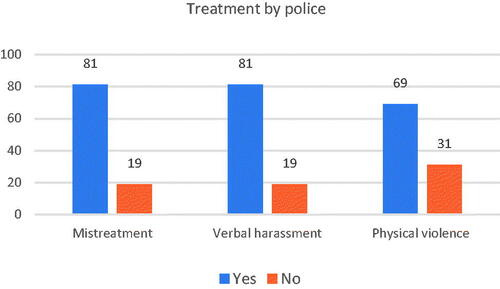

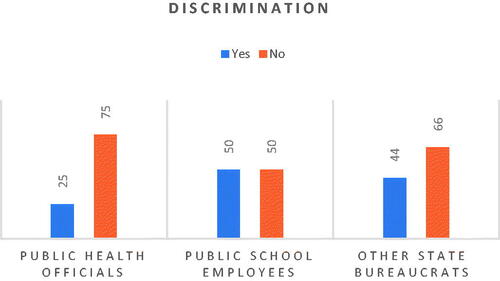

Structural violence is when “social structures or institutions that keep individuals from meeting basic needs—from a healthy existence” (Grauer & Buikstra, Citation2019). This can express itself as discriminatory laws, lack of access to education, lack of access to dignified work, and lack of access to housing (Ortiz & Jackey, Citation2019). For example, according to a study carried out in Peru, transgender women experience harassment and violence from police officers. Moreover, due to discriminatory laws and “social stigma,” they are unable to report the extent of the violence (Rodríguez-Madera et al., Citation2017).

Regarding police violence, demonstrates that 13 respondents (81%) of the transgender women reported mistreatment, 13 respondents (81%) reported harassment, and 11 respondents (69%) reported physical violence. Thus, among incarcerated transgender women, the police are not equated with safety. Quite the contrary, for many, the security forces are a source of insecurity. Then, regarding discrimination, indicates that 4 respondents (25%) reported experiencing it from public health officials, 8 respondents (50%) from public school employees and, 7 respondents (44%) from other state bureaucrats.

In general, transgender women are an at-risk social group. Once incarcerated, they face additional challenges to their safety (Wilson et al., Citation2017). The transgender women interviewed were asked the question, “do you feel safe?.” Only 8 respondents (50%) reported feeling safe around the police, 7 respondents (44%) reported feeling safe around other prisoners, and 8 respondents (50%) reported feeling safe around the prison staff.

Given how widespread violence is, further research is merited. For example, to explore the types of violence inflicted on incarcerated transgender women by prison staff in comparison to other prisoners. Once incarcerated, transgender women are under custody of the State. For this reason, there is a state obligation to guarantee their safety. Additional research could highlight the institutional shortcomings in ensuring their physical and psychological well-being.

Criminal Justice System

Crime, much like gender, is a political and social construct. Kappeler and Potter (Citation2017) argues that rather than respond to threats, criminal justice responds to dominant social myths (p. 444). In many cases, crime is “disproportionately attributed to the behaviors of those with marginalized racial, sexual, and gender identities” (Gaynor, Citation2018). As a result, in the public imaginary, crime is linked with anyone who is not cisgender, heterosexual (Gaynor, Citation2018) and middle-class (Francisco Simon, Citation2021, p. 245). The result is the criminalization of transgender women because of their gender identity (Lyons et al., Citation2017) and their poverty (Francisco Simon, Citation2021, p. 247).

Essentially, transgender women face multiple and persistent forms of violence. In many ways, incarceration adds another layer of violence. Criminalization is the result of 1) widespread transphobia (Lyons et al., Citation2017), 2) a lack of economic opportunities (Lyons et al., Citation2017), 3) punitive policies implemented against the criminal acts more likely to be committed by more impoverished individuals (in juxtaposition to the ‘light’ approach taken against white-collar crime) (Francisco Simon, Citation2021, p. 240), and 4) the influence of the War on Drugs. In the context of the War on Drugs, repressive criminal justice policies have been used to address insecurity. This has translated into harsher sentencing for drug-related crimes, resulting in a crisis of mass incarceration throughout Latin America (Chaparro Hernández & Pérez Correa, Citation2017).

Case in point, a significant proportion of the transgender women interviewed were incarcerated for drug-related crimes, as portrayed by respondents, (44%). Given its geographic location between the countries where there is cocaine production and countries where there is cocaine consumption, Costa Rica has become a “bridge” for drug trafficking since the nineties. (Saborío, Citation2019). Moreover, as shown in , the second criminal offense for which transgender women were most incarcerated was theft, 4 respondents (25%), homicide, 2 respondents (13%), kidnapping, 1 respondent (6%) and sexual abuse, 1 respondent (6%).

Furthermore, it should be noted that the majority, 10 respondents (63%), were first-time-offenders. Since the ’80s, the rise of mass incarceration has resulted in the rise of the alternative sentencing movement. It has led to more significant support for alternative sentencing and other measures besides incarceration (Mauer, Citation2018, p. 118). Yet, alternative sentencing, even for first-time offenders, is seldomly applied in Costa Rica. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has advocated for greater use of alternative sentencing, particularly with a “gender perspective and a differentiated approach with respect to at-risk groups” (Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Citation2017, p. 16). Admittedly, transgender women should be candidates for alternative sentencing given their multiple vulnerabilities.

When asked about the reasons for the criminal offense, as indicated in , transgender women identified economic necessity as the primary cause, 7 respondents (44%). Then, 2 respondents (13%) stated it was due to threats, 1 respondent (6%) attributed it to drug consumption, 1 respondent (6%) stated vengeance, and 5 respondents (31%) reported other.

The high number of transwomen driven by economic necessity proves that the punitive policies target primarily poor individuals. As demonstrated in , it is also noteworthy that 2 respondents (13%) were incarcerated due to threats and 1 respondent (6%) due to drug consumption—two very vulnerable groups. In the first case, the individuals were under duress. In the second case, drug consumers need treatment. That requires collaboration between the penitentiary system and rehabilitation providers. These needs are often unmet (UNODC, Citation2003).

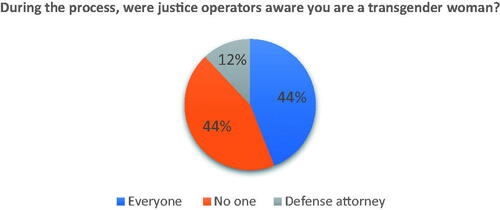

It was vital to examine if the criminal justice system is trans-inclusive. Gender is a deeply embedded social construct. It is reproduced through routine and discourse until it is deemed to be natural. As a result, many individuals adopt a rigid attitude toward gender identity and gender expression (Lorber, Citation2009, pp. 111–114). These attitudes permeate social, cultural, and legal norms (Buist & Stone, Citation2014). As a result, the criminal justice system, and by extension, the prison system, does not exist in a neutral space. Quite the contrary, “personal beliefs and cultural norms often play a part in legal decisions, particularly those regarding transgender criminal cases” (Buist & Stone, Citation2014).

As a means of assessing the degree of trans-inclusiveness during the criminal justice process, transgender women were asked if the other participants were aware of their identity. According to respondents (44%) stated everyone was aware, 7 respondents (44%) states no one was aware, and 2 respondents (12%) stated only their defense attorney was aware of their identity. It should be noted that only 2 respondents (13%) had private representation. The rest had to rely on a public attorney. This implies that their experience provides an insight regarding the current state policies and norms governing the criminal justice system.

Prisons have historically been strictly segregated based on biological sex. This has resulted in a “somewhat hidden war on transgender women housed in men’s facilities (as well as transgender men housed in women’s facilities)” (Stohr, Citation2015). In effect, anyone who does not fall within the gender binary faces de facto marginalization.

Since being incarcerated within a men’s prison often aggravates transgender women’s vulnerabilities, it was essential to ask the transwomen about their prison preference- if they had a choice. shows the results regarding their prison preference, 3 respondents (19%) selected a women’s prison, 4 respondents (25%) selected a special wing for transgender women in the women’s prison, 6 respondents (38%) selected a special wing for transgender women in the men’s prison, and 3 respondents (19%) selected staying in the men’s prison system.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

From a human rights perspective, the unique needs of vulnerable groups should be addressed when elaborating legal norms and public policies. For example, incarcerated transgender women are arguably among the most vulnerable social groups. To this effect, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime has declared that incarcerated women have a “particularly vulnerable status in prisons” (UNODC, Citation2009, p. 1). However, far from being directly addressed, their needs have thus far been brushed aside from a legal and an institutional standpoint.

In the case of Costa Rica, the country has expressed a profound commitment to human rights. Indeed, “its record of human rights promotion is enduring and multifaceted” (Brysk, Citation2005). To this end, there have been some noticeable advances with regards to ciswomen’s rights. However, the legal system and institutional layout respond to a restrictive notion of gender.

Narcotics Law Reform 77bis

One of the positive advances in Costa Rica was the reform known as “77 bis” to the “Law on Narcotics, Psychotropic Substances, Unauthorized Drugs, Related Activities, Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism, Law No. 8204”. However, this was a “modest” reform since its application was limited to the crime of smuggling drugs into the prison system (Mora Bolaños, Citation2019).

In 2013, this law was reformed to lessen the sanction for women incarcerated for “introducing drugs into the prison system” if they were first-time, nonviolent offenders and in a situation of extreme vulnerability. Based on pre-established criteria, judges are allowed to diminish the length of the prison sentence. Some of these requirements include that the woman must be living in poverty, be the sole head of the household, have dependents in her charge, or be elderly. Those who meet any of these requirements will have sentences of between three and eight years, which can be served through alternative measures to prison.

The legal reform was advocated because Costa Rica has not “fulfilled the commitments acquired due to ratifying international instruments for the protection of fundamental rights” (Orozco Álvarez, Citation2012). It should be noted that Costa Rica has ratified a significant number of international treaties, such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, which was ratified by Law No. 6968 on October 2, 1984. Then the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence against Women, was ratified by Law No. 7499 on 1995, May 2. Both treaties were invoked in the draft legislation. Thus, the gender perspective was added, in part, to comply with international commitments.

Besides upholding international norms, the draft legislation is also a critique of dominant cultural norms. It explicitly “condemns” discrimination against women “rooted in the cultural structures” (Orozco Álvarez, Citation2012). This part of the proposed bill is significant because it acknowledges that gender discrimination is embedded in state and cultural structures.

For its part, UNODC (Citation2009) has declared that the reform constitutes good practice in drug regulations, “not only because it incorporates the gender perspective but also because it does not establish a minimum penalty for these crimes.” However, 77bis applies to the particular case of women at risk of introducing drugs to prisons. In practice, this has only been applied to cisgender women.

Despite reform 77 bis, additional necessary measures have not been taken to deal with all groups at risk. The situation of transgender women is a case in point. The United Nations Committee Against Torture (Citation2008, p. 4) and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos, 2015, p. 72) have expressed concern about the human rights violations of transgender people in Costa Rica. According to a study carried out in Latin America by REDLACTRANS (Citation2020), 67% of the cases of abuse reported by transgender people “had as perpetrators State agents, mainly agents of the police forces” (p. 13).

Since 2014, the Costa Rican Public Defense Office has noticed a variation concerning the profile of the people sentenced for entering drugs into a penitentiary center under article 77. Of these, 30% of the offenders classified as “male” by the State are transgender women (Z. Molina, personal communication, December 14, Citation2016). They tend to have additional risk conditions, such as social exclusion, extreme poverty, HIV, and problematic drug consumption. By being incarcerated in the male penitentiary systems, they suffer abuse and mistreatment at the hands of both prison staff and fellow prisoners. Despite this, there are no clear administrative and legal policies to provide them with the proper technical attention. Nevertheless, the rights of transgender women are not on the political agenda.

Criminal Code Reform 71bis

Notwithstanding the neglect of transgender rights, since 2013, there have been even more advances regarding the protection of cisgender women. For example, on 2018, November 19, article 71 of the Criminal Code was reformed by Law N° 9628. The text was changed so that the judge could reduce the penalty for any crime based on several mitigating factors, including “the sentenced person is a woman in a vulnerable state, due to poverty, being the primary caregiver for dependent family members, disability or being the victim of gender violence.”

According to the National Institute for Women (INAMU), the reform intends to guarantee “greater rationality and humanity” when sentencing first-time female offenders. The INAMU was part of an inter-institutional network whose aim was to reform the criminal justice system to address the myriad of structural injustices faced by women (INAMU, Citation2018). In this regard, this legal reform is a form of “affirmative action” favoring cisgender women (Mora Bolaños, Citation2019).

DISCUSSION

Although the Costa Rican legal framework enshrines universal human rights and multiple treaties which extend the realm of human rights, transgender women continue to be excluded from legal protections. Currently, the state practice is to restrict women’s rights to cisgender women’s rights. This restrictive legal interpretation stems from a transphobic perspective. Moreover, it is a symptom of more significant social phenomena. Transphobia begins at home and pervades the streets, the schools, the Courts, and the prison system.

Even the public institutions, national laws and international treaties that protect transgender women neglect them and contribute to their marginalization. In general, despite the substantial progress regarding women’s rights in the last three decades in Costa Rica, these same protections are not applied to transgender women. From a legal perspective, there is growing consensus that the term “sex” should be interpreted in the broadest sense, thereby including “all kinds of sexes, including transgender, intersex and other differently-sexed and gendered people” (Holtmaat & Post, Citation2015).

It should be noted that neither CEDAW nor the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence against Women explicitly defines the term “woman.” Indeed, the “ordinary understanding” of the term “woman” often refers to sex and gender. For this reason, some authors have argued that the principles therein enshrined could be expanded to “protect lesbian, bisexual, and transgender (“LBT”) women” (Gallagher, Citation2020). Moreover, given that these treaties aim to eliminate all forms of discrimination and violence against women, a “trans-inclusive interpretation” would align with the treaties core purpose. (Gallagher, Citation2020).

This viewpoint is supported by the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. In effect, the Committee seems to be “cautiously” supporting a trans-inclusive interpretation of international law (Holtmaat & Post, Citation2015). Thus, for example, the General Recommendation No. 28 on the Core Obligations of States Parties (2010, October 19) stated the following:

“Intersectionality is a basic concept for understanding the scope of the general obligations of States parties contained in article 2. The discrimination of women based on sex and gender is inextricably linked with other factors that affect women, such as race, ethnicity, religion or belief, health, status, age, class, caste, and sexual orientation and gender identity.”

The CEDAW Committee’s attention to LBTQI issues remains scarce in all categories of documents except for the Concluding Observations. Our analysis of the Committee’s Concluding Observations since 2010 shows that sexual orientation and some forms of gender identity (most notably transgender) are mentioned in over one-third of the documents concerning countries from all continents. (Holtmaat & Post, Citation2015)

On a similar note, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights has affirmed that the principle pro homine should guide conventional international law. Via its jurisprudence, the Court has established that a norm should be interpreted in the broadest sense and in a way that guarantees human dignity (Arrubia, Citation2018).

A trans-inclusive interpretation within international is more evident in soft law, such as in the “Principles on the application of international human rights legislation in relation to the sexual orientation and gender identity”, commonly referred to as the Yogyakarta Principles (Arrubia, Citation2018). Although not legally binding, these principles signal the growing acceptance of transgender identity and rights.

From the perspective of Costa Rican national law and based on the constitutional principle of nondiscrimination, articles 77bis from Law No. 8204 and 71bis from the Criminal Code should be applied to transwomen. As it stands, the mitigating factors are not being applied due to a restrictive interpretation of gender.

There have been some positive advances with regards to protecting transgender rights. For instance, the Executive Decree No. 37071-S: Day Against Homophobia and Lesbophobia and Transphobia (2012), Regulation of photographs for the identity card (Decree No. 08-2010) from the Supreme Electoral Tribunal. The regulations allow transgender women to photograph according to their gender identity (Article 2), regardless of their legally assigned identity.

Despite these progressive regulations, the prevalence of violence is an indicator of the failure of current policies in ensuring trans-inclusive security. Additionally, cultural factors also guarantee impunity for perpetrators of crimes against transgender people. According to Fattah (Citation2014), there is a cultural and structural propensity to victimization. A lack of power, economic deprivation and cultural stigmatization also makes certain social groups be deemed “easy prey’ or as culturally legitimate victims” (p. 13).

There is a need for trans-inclusive interpretations of the laws and policies which underpin public institutions. For example, the Public Defender’s Office has included sociodemographic measurement instruments to identify populations in vulnerable conditions and train public officials within its Strategic Plan (Z. Molina, personal communication, December 14, Citation2016). However, there are no trans-inclusive protocols to coordinate their treatment within the prison system. Likewise, it is essential to establish public policies to address the needs of transgender women throughout the criminal process. Yet, trans-inclusiveness needs to precede the prison system.

As this investigation demonstrated, transgender women are incarcerated in the aftermath of lives in which they have been subjected to multiple forms of violence. In this regard, their incarceration is often the result of extreme direct, social, and structural violence. In many cases, the victimization of incarcerated transgender women begins during their childhood. It continues when they enter the school system. Rather than being a place of learning, schools are, at times, a place of violence.

Moreover, the gender discrimination many transgender women experience when trying to obtain work demonstrates that they face many structural and social obstacles. In effect, transgender women are victimized by private and public actors. For instance, the public healthcare system also victimizes transgender women. There is scant information regarding the health needs of transgender individuals. By extension, there is also a gap in the treatment models being used for transgender individuals. Due to the lack of gender reaffirming procedures, the lack of trans-inclusive drug rehabilitation and the lack of mental health support, healthcare is a source of violence and not healing.

From a legal perspective, transgender identity remains unrecognized. Accordingly, transgender women are denied equal treatment under the law as cisgender women. With respect to the criminal justice system, they should be afforded the mitigating factors enshrined in articles 71bis and 77bis if they meet the same criteria as cisgender women. Similarly, following the guidelines established by the IAHRC and UNODC, there needs to be greater use of alternative sentencing.

Above all, further research is required. This research demonstrates that transgender women are often incarcerated due to economic, social, and structural marginalization. As it stands, they remain amongst the most marginalized citizens. Therefore, it is essential to fully understand the situation of incarcerated transgender women, taking into account their diverse identities, needs, and aspirations.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

REFERENCES

- Akers, R. (2006). Aplicaciones de los principios del aprendizaje social. Algunos programas de tratamiento y prevención de la delincuencia. In Arús F.J. L.Dalbora & A.Maíllo (Eds.), Derecho penal y criminología como fundamento de la política criminal: estudios en homenaje al profesor Alfonso Serrano Gómez (pp. 1117–1138). Editorial Dykinson.

- Annan, K. (2003). Special measures for protection from sexual exploitation and sexual abuse. United Nations Population Fund. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/ref/https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2014.991055?scroll=top

- Arrubia, E. J. (2018). El derecho al nombre en relación con la identidad de género dentro del Sistema Interamericano de Derechos Humanos: el caso del Estado de Costa Rica. Revista Direito GV, 14(1), 148–168. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/2317-6172201808

- Awan, M. S., Malik, N., Sarwar, H., & Waqas, M. (2011). Impact of education on poverty reduction. International Journal of Academic Research, Vol. 3, No. 1 (2011): pp. 659–664. Available at: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/31826/1/MPRA_paper_31826.pdfpp.659-664.

- BBC. (2015). A guide to transgender terms. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-32979297

- Beek, T., Cohen-Kettenis, P., & Kreukels, B. (2016). Gender incongruence/gender dysphoria and its classification history. International Review of Psychiatry, 28(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2015.1091293

- Brysk, A. (2005). Global good Samaritans? Human Rights Foreign Policy in Costa Rica. Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, 11(4), 445–466. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-01104004

- Budhwani, H., Hearld, K. R., Milner, A. N., Charow, R., McGlaughlin, E. M., Rodriguez-Lauzurique, M., Rosario, S., & Paulino-Ramirez, R. (2018). Transgender women’s experiences with stigma, trauma, and attempted suicide in the Dominican Republic. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 48(6), 788–796. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12400

- Buist, C. L., & Stone, C. (2014). Transgender victims and offenders: Failures of the United States criminal justice system and the necessity of queer criminology. Critical Criminology, 22(1), 35–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-013-9224-1

- Burgess-Proctor, A. (2006). Intersections of race, class, gender, and crime: Future directions for feminist criminology. Feminist Criminology, 1(1), 27–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1557085105282899

- Campbell, B. (2019). Transgender-specific policy in Latin America. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics.

- Caravaca-Morera, J. A., & Padilha, M. I. (2018). Trans necropolitics: Dialogues on devices of power, death and invisibility in the contemporary world. Texto & Contexto – Enfermagem, 27(2), 2-10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-07072018003770017

- Chaim, N. (2008). Sampling knowledge: The hermeneutics of snowball sampling in qualitative research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11(4), 327–344. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570701401305