ABSTRACT

For this paper we investigated refugee entrepreneurship in the Dadaab refugee camps, Kenya, a place where humanitarian aid practices and domestic legislation impede entrepreneurship, yet hundreds of new ventures have been established by refugees. The analysis finds that refugee camp entrepreneurs erode formal institutions, recombine conducive aspects of both formal and informal institutions, and exploit the advantages of institutional misalignment. We explain how entrepreneurs strategically maintain rather than overcome institutional misalignment for venture creation. Second, we show how self-determination, rather than mere subsistence or necessity, is an important yet often overlooked motivator for entrepreneurship in low and lower middle-income contexts.

Introduction

The purpose of a refugee camp is to provide refugees with temporary shelter and humanitarian aid until a safe return to their country of origin is possible (Perous de Montclos and Kagwanja Citation2000). Refugee camps are often portrayed as solemn safe-havens for the forcibly displaced and, in turn, refugees are depicted as destitute victims of conflict and violence, unable to survive without the shelter and assistance afforded by humanitarian aid practices (Eggers Citation2006; Rawlence Citation2016). While this portrayal may be true in some refugee camps, setting foot in the Dadaab refugee camp complex in remote East Kenya, it is immediately clear that this camp is anything but a place where passive refugees patiently and gratefully wait to return home – refugees have established shops and cafés that line the dusty streets, markets have been organized adjacent to aid distribution centres, and refugees hawk carts loaded with products to sell. These ventures offer everything from bridal gowns to smart phones and generate an estimated 25 USD million in annual turnover (Okoth 2012Footnote1). The economic vitality of refugee camps (Betts et al. Citation2016) is surprising as humanitarian aid is provided free to all camp residents, refugee camp design makes no provision for business premises or market places, and in Kenya, legislation restricts refugee access to employment and business permits. The puzzle we investigate is to explain how and why refugee camp entrepreneurs (RCEs) establish new ventures when humanitarian aid practices and domestic legislation impede refugee entrepreneurship.

The research adopts an institutional lens to investigate how context influences entrepreneurship when formal institutions impede entrepreneurship. An institutional context comprises both formal and informal institutions and prior research has investigated the interplay between both types of institutions (Helmke and Levitsky Citation2004; Weingast Citation1995; Williamson Citation2000). Institutional contexts in developing countries have been described as voids (Mair, Martí, and Ventresca Citation2012) and, when formal and informal institutions do not support each other, the context is described as institutionally asymmetrical (Williams and Shahid Citation2016) or misaligned (Weingast Citation1995). Incoherence between formal and informal institutions has been found to impede business activity (Estrin, Korosteleva, and Mickiewicz Citation2013; Mair, Martí, and Ventresca Citation2012; Sutter et al. Citation2013). Although a refugee camp may seem an unconventional place to conduct entrepreneurship research, the extreme context provides an opportunity to examine how misaligned formal and informal institutions influence new venture creation.

The analysis theorizes three mechanisms by which RCEs navigate institutional misalignment. First, RCEs erode formal institutions. RCEs appeal to blind spots in humanitarian aid practices, for example, by retailing a more varied selection of foods than provided by humanitarian aid. Appealing to blind spots in turn strengthens norms and values that endorse informal entrepreneurship. Second, RCEs recombine conducive aspects of formal and informal institutions. RCEs repurpose humanitarian aid practices and places by stripping them of their primary purposes and imbuing them with alternative meanings. For example, tent pitches on streets with high footfall become business premises, and ration cards are used as debt collateral. Third, RCEs exploit institutional misalignment and portray themselves on the one hand as entrepreneurs to reap the benefits of entrepreneurship, and on the other, as vulnerable victims eligible to receive humanitarian aid. RCEs thus maintain institutional misalignment to preserve the advantageous aspects of formal and informal institutions.

The paper makes two contributions to theory. First, we advance a new perspective on context and entrepreneurship (Kibler Citation2013; Goel and Karri Citation2020) by explaining how institutional misalignment can facilitate entrepreneurship. We therefore depart from the conclusions of extant scholarship (e.g. Mair, Martí, and Ventresca Citation2012; Sutter et al. Citation2013) which finds that misaligned institutions impede entrepreneurship. In our case study, opportunity recognition, resource acquisition and new venture creation are possible as a result of institutional misalignment between formal institutions that impede and informal institutions that facilitate entrepreneurship. Moreover, our research elucidates how RCEs seek to maintain rather than resolve institutional misalignment. The second contribution concerns entrepreneur motivation. Prior research in low and lower middle-income countriesFootnote2 has noted the prominence of subsistence, or necessity, entrepreneurship in which entrepreneur motivation is survival (Hall et al. Citation2012; Sutter, Bruton, and Chen Citation2019). As humanitarian aid is designed to meet refugees’ basic need for medical care, shelter, food and water, survival does not fully explain why RCEs establish new ventures. We find that RCEs are motivated by the desire to exercise choice and express autonomy and individuality. Reclaiming economic agency and self-determination thus constitute powerful yet overlooked motivation for entrepreneurship in low and lower middle-income countries.

The paper commences with a review of the literature of institutions as they relate to new venture creation, particularly in low and lower middle-income countries, and entrepreneurship. This is followed by the methods and the findings from the Dadaab camps. We then discuss our case analysis, contributions to theory, and conclude with implications for practice and suggestions for future research.

Theoretical background

Institutions

Formal institutions, namely laws, rules, and regulations, and informal institutions, i.e. practices, values, and routines, together form an institutional context (Helmke and Levitsky Citation2004). Collectively, formal and informal institutions comprise the taken-for-granted rules of the game that guide behaviour and set forth the only logical way to make sense of and act in a given situation (North Citation1990).

In high and upper middle-income countries formal institutions, such as political and economic rules and rights, are anchored in centuries of political, economic and social developments (North Citation1990; de Soto Citation2000). Formal institutions thus tend to be well defined, for example, in legislation, regulations and codes of practice, and enforced with sanctions. Although regulatory, normative and cognitive institutions may overlap, ultimately a consensus emerges and the formal institutional context is established (Fligstein Citation1996; North Citation1990). Clearly defined formal institutions lead to an efficient institutional architecture (Fuentelsaz, González, and Maicas Citation2019) and provide the framework of trust needed for new venture creation. If, however, formal market institutions such as economic freedoms and property rights are ill-defined, entrepreneurs lack protection and new venture creation is discouraged as entrepreneurs are sceptical about realizing the gains from their efforts and investments (Williamson and Mathers Citation2011).

Informal institutions, on the other hand, are not designed consciously and emerge from information that has been transmitted socially (North Citation1990). Informal institutions function outside the official economy (De Soto Citation2000), and are not explicitly encoded in laws, regulations and codes. Instead, for example, they reside in cultural norms and operate at a deeper level than formal institutions, for example, family and religious norms (DiMaggio Citation1988; North Citation1990). As informal institutions are self-regulating, they are difficult to control or change (ibid.) and implicitly shape how markets work in a given context. Research finds that, for example, cultural and religious norms can exclude women from economic transactions (Mair, Martí, and Ventresca Citation2012) and that, in some cultures, business values prioritize family and community above other norms (Khavul, Bruton, and Wood Citation2009).

When formal and informal institutions are aligned, the cost of enforcing formal institutions is relatively low because they are accepted and in use (Weingast Citation1995). But if formal institutions do not reflect the underlying informal institutions, enforcing formal institutions will be costly because they run counter to the underlying belief systems (Boettke and Coyne Citation2009). Entrepreneurship, opportunities and the capacity of entrepreneurs to exploit opportunities and create new ventures, are thus influenced by institutional context (Goel and Karri Citation2020), and institutional misalignment offers an intriguing context in which to explore entrepreneurship.

Institutions in low and lower middle-income countries

There are many ways to classify countries according to their basic economic conditions (World Bank Citation2019). Income classification distinguishes between high and upper middle-income countries (developed economies), and low and lower middle-income countries (developing economies and economies in transition) (Prydz and Wadhwa Citation2019). Specifically, the classification identifies three important institutional differences between the two groups.

First, formal market institutions in low and lower middle-income countries are often ill-defined and ambiguous. Also referred to as institutional voids, low and lower middle-income countries are described as having ‘underdeveloped market-supporting institutions including weak laws and poor enforcement capacity of the formal legal institutions,’ (Bruton et al. Citation2013, 170). Empirical studies find that the main characteristic of institutional voids is the absence of market institutions, namely, ‘uncodified institutional environments’ (Ahlstrom and Bruton Citation2006, 300), ambiguous property rights (Puffer, McCarthy, and Boisot Citation2010), lack of regulatory systems and contract-enforcing mechanisms (Fligstein Citation1996; Khanna, Palepu, and Sinha Citation2005), and overall weak corporate governance and control (Chakrabarty Citation2009; Khanna and Palepu Citation1997; Uzo and Mair Citation2014).

Second, Mair, Martí, and Ventresca (Citation2012) note the important role of informal market institutions in low and lower middle-income countries (also see Williams and Gurtoo Citation2017). Based on the ‘need to maintain a healthy scepticism toward the idea that a specific type of institution is the only type that is compatible with a well-functioning market economy’ (Rodrik Citation2007: 162 f), they maintain that ‘the absence of (formal) institutions does not imply the existence of a sort of institutional vacuum,’ (Mair and Martí Citation2009, 422). This more sociologically informed view suggests that in the absence of well-defined formal institutions, informal institutions become more central and hence that institutional voids are therefore ‘rich in other institutional arrangements’ (Mair and Martí Citation2009, 422) such as family, culture, gender and religion (Mair, Martí, and Ventresca Citation2012) that enable, but may also impede, economic activity (Khanna and Palepu Citation1997; Mair and Martí Citation2009). Mair, Martí, and Ventresca (Citation2012) therefore speak of contexts in which formal and a multitude of informal institutions interface, creating a complex institutional context.

Finally, the literature employs the concept of ‘institutional asymmetry’ (Williams and Hodornic Citation2015; Williams and Shahid Citation2016) and ‘institutional incongruence’ (Williams, Horodnic, and Windebank Citation2015) to describe contexts where formal institutions do not reflect the everyday practices encoded in informal institutions. In an analysis of new venture creation in Pakistan, Williams and Shahid (Citation2016) find that entrepreneurs incorporate aspects of both formal institutions and informal expectations, thus leading to semi-formalized businesses. Kistruck et al. (Citation2015) similarly find that entrepreneurs in Guatemala struggle as neither compliance with formal institutions nor informal expectations served their needs.

Whether described as institutional voids, interfacing institutions, or institutional asymmetry, markets in low and lower middle-income countries are thus characterized by institutional architectures in which the competing demands of formal and informal institutions create ambiguity and uncertainty (Kistruck et al. Citation2015; Mair, Martí, and Ventresca Citation2012; Williams and Shahid Citation2016). A small group of studies shed light on the consequences of ambiguous formal and opposing informal institutions for entrepreneurship. Empirical research has almost exclusively used business registration to examine how entrepreneurs manage institutional misalignment. In institutionally misaligned contexts, a new venture can be considered illegal (formal institutions) and simultaneously legitimate (informal institutions) (De Soto Citation2000; Webb et al. Citation2009). Williams and Shahid (Citation2016) find that entrepreneurs in Pakistan aim to comply with aspects of formal business registration and informal expectations but avoid full compliance with both. Entrepreneurs may avoid informal institutional expectations altogether (Sutter et al. Citation2013), and when formal and informal institutional demands are too ambiguous, as in Nigeria’s movie industry, entrepreneurs defy them all (Uzo and Mair Citation2014). However, while institutions provide a framework to understand the formal and social fabric that enables, shapes, and constrains entrepreneurship (De Soto Citation2000), we know less about how and why institutional misalignment influences new venture creation beyond business registration. Yet, given that the majority of the world’s entrepreneurs operate in low and lower middle-income countries characterized by institutional misalignment, the relationship between institutions and entrepreneurs is key to understanding new venture creation in such contexts. This paper therefore sets out to theorize how entrepreneurs establish new ventures when institutions are misaligned.

Methods

The empirical context

Although every refugee camp is a unique composition of legal, normative and cognitive institutions, all refugee camps are established as emergency humanitarian interventions and designed to ensure the protection, survival and provision of humanitarian aid to forcibly displaced individuals (Perous de Montclos and Kagwanja Citation2000). The UNHCR, responsible for managing all refugee camps (UNHCR Citation2013), and implementing partners simply make no provision for needs other than survival and organizing access to medical care, shelter, food and water. Refugee camps are intended to be temporary and ‘transient safe-havens’ where refugees recover and wait to return to the country from which they fled (UNHCR Citation2013). Furthermore, in many countries, domestic laws prohibit refugees from obtaining employment or business permits and, in some countries, even from leaving the refugee camp without special permission. Refugee camps thus constitute a context in which formal institutions impede entrepreneurship.

In Kenya, the national government maintains that all refugees are temporary guests and imposes strict regulations to prevent their assimilation into Kenyan society (Rawlence Citation2016). These restrictions largely result from security considerations following large-scale attacks by Somali terrorist groups, as well as economic concerns regarding the hypothetical integration of hundreds of thousands of low-skilled refugees into the national economy. Refugees in Kenya are de facto unable to apply for employment or business permits and remain in the country at the discretion of the Kenyan governmentFootnote3 (Horst Citation2008). Although these legal regulations are intended for temporary refugees, the Dadaab refugee camp complex was established in 1992 and of the approximately 211 000 primarily Somali refugees housed there many were born in the camp, as were their children (UNHCR Citation2018). This length of refugee stay is not unusual – the average duration of refugee displacement globally is approximately 20 years (UNHCR Citation2017). Refugees in Kenya are thus caught in a state of permanent transience in which formal institutions prevent them from building a permanent life in exile, nor can they return to their war-torn country of origin. This paradox is further endorsed by the UNHCR humanitarian view that refugees are vulnerable victims who need to be provided with the means to survive (Hunter Citation2009). After decades in the Dadaab camps, UNHCR and implementing partners continue to provide refugees with monthly food rations and aid packages (tent, clothing, mats, blankets, and kitchen utensils). The UNHCR and implementing partners thus uphold the refugee camp as a temporary humanitarian emergency response and thereby implicitly endorse the Kenyan government policy that denies refugees permanent residence and property rights protection. An aid worker explains that:

We have created a dependency syndrome and after decades of being provided for, many refugees have forgotten how to even fend for themselves. (Interview, aid worker 1)

Humanitarian aid practices are manifest in the omnipresent signs and logos emblazoned on all physical aspects of the Dadaab camp complex: signs such as ‘Funded by … ’, ‘Donated by … ’, ‘Established through the support of … ’ are painted on all UNHCR tents, food wrapping, cars, and even the local Kenyan police station on the outskirts of the camp complex. The visibility of these signs endorses refugees’ status as victims dependent on humanitarian aid. Humanitarian aid distribution centres, NGO-run schools and medical centres inside the Dadaab camps further endorse this view. An aid worker critically reflects on UNHCR humanitarian aid practices:

There have been many critical voices, especially in the past few years. How sincere are humanitarian agencies in wanting to end the refugee crisis? I think that’s a very legitimate question to ask. The humanitarian aid world would lose a lot of money and a lot of jobs if they handed everything over to the development guys. (Interview, aid worker 3)

Moreover, the Dadaab camp complex is isolated and located 300 miles from Nairobi. Each camp in the complex of three camps is a twenty minute drive on a sand road (which disintegrates into insurmountable mud tracks during the rainy season) from Dadaab village. Dadaab village is an impoverished settlement of nomadic livestock herders and several hours’ drive from Garissa, the nearest town. In addition to the remote location, fences and roadblocks enclose the Dadaab camps. Although refugees frequently walk to and from Dadaab village, unauthorized travel beyond is virtually impossible. Kenyan government policy to prohibit refugee freedom of movement is strictly enforced and the roadblocks and armed guards ensure that refugees do not travel beyond Dadaab village. A camp manager explains the restrictions on refugee freedom of movement:

There is a fence around the camp but they can just walk to the village. And people from the village can come in. Dadaab is in the desert so there is not very much around. But they [refugees] cannot travel on the road to Garissa. There is one road out of the camp to Garissa. But we have police blocks there and the refugees need permits to leave the camp. They need a permit from UNHCR and a permit from the Kenyan government. If they do not have it, they cannot leave the camp. (Interview, camp manager 8)

Taken together, the formal institutions that regulate the Dadaab camps comprise UNHCR humanitarian aid practices that undermine self-determination, and Kenyan laws that control refugees’ freedom of movement, and deny access to employment and business permits. These formal institutions impede entrepreneurship. In his book about the Dadaab camps, Rawlence (Citation2016, 90) speaks of the moment when refugees enter the refugee camp as ‘the moment of the bargain. … When you surrendered your autonomy [for a ration card]’. A refugee informant summarizes the biggest problem for refugees in the Dadaab camp complex:

Psychological wellbeing. People have been in the camp for too long. They cannot leave, they are stuck in the camp. I have recognized that I will be here for quite some time. We are not allowed to leave, we are not allowed to get decent jobs. (Interview, refugee 7)

The formal institutions that restrict refugees freedoms contrast with the institutions regulating life for Kenyans. Kenyans face no legal restrictions on movement, employment, or business activity. In Garissa County, where the Dadaab camp complex is located, nearly all Kenyans of working age are involved in informal entrepreneurship and only 8% of the labour force is in salaried formal employment (Garissa County Government Citation2019). The pervasiveness of informal entrepreneurship is explained by the absence of formal employment opportunities and the strong cultural heritage of entrepreneurship among the Kenyan-Somalis living in the region (Horst Citation2008). While entrepreneurship is thus characteristic to the region in which the Dadaab camp complex is located, autonomy differs markedly between refugees and Kenyans.

However, despite the formal institutional impediments to entrepreneurship for refugees, across the Dadaab camp complex there are several large markets and hundreds of stalls that sell fresh vegetables and fruits, SIM cards, mobile phones, and there are thriving hairdressers, barbers, beauty parlours, cafés and restaurants. Our study set out to investigate such entrepreneurial activity in the context of institutional misalignment.

Research design

We selected the Dadaab camps as our research site for three reasons. First, the Dadaab camp complex is one of the largest refugee camps in the world (Wesangula Citation2016) and was described by an UNHCR informant as ‘the refugee camps par excellence’ (Field notes, day 3). The Daadab camp complex is thus an exemplary case study (Yin Citation2011). Second, secondary data confirmed that in Kenya, refugees are de facto ineligible to apply for employment and business permits and their freedom of movement is curtailed (Library of Congress Citation2016), whereas media reports provided evidence that refugee-led business ventures and markets flourish in the Dadaab camps (Hill, Citation2011). Third, the first author had worked with the UNHCR and they agreed to support the investigation.

Although refugee camps receive extensive media attention, they have not been the site of entrepreneurship research. A few studies have investigated refugee entrepreneurship in urban settings, for example, Syrian refugees in Lebanon (Bizri Citation2017), the internally displaced in Pakistan (Manzoor, Rashid, Cheung and Kwong Citation2019) and female refugees in Jordan (Al-Dajani, Akbar, Carter, and Shaw Citation2019). Institutional scholars have studied refugee asylum seekers in Europe and North America (Hardy Citation1994; Phillips and Hardy Citation1997; Hardy and Phillips Citation1999; Lawrence and Hardy Citation1999). Just two studies have gathered data from inside refugee camps – Mintzberg (Citation2001) gives an insightful account of refugee camp managers in Tanzania, and de la Chaux, Haugh, and Greenwood (Citation2018) examine the organizational dynamics between camp managers and refugees.

Given the dearth of empirical research, the increasing number of refugee camps and the length of time refugees reside in a camp, we adopted a qualitative case study research design (Yin Citation2011) to investigate how and why refugees establish new ventures in the Dadaab camps. A qualitative case study allows researchers to achieve a deep understanding of the processes and dynamics at play in a given context (Eisenhardt Citation1989) and is therefore particularly suited to investigating phenomena that have received limited scholarly attention, such as refugee camp entrepreneurs. Finally, and more broadly, qualitative case studies are especially useful in extreme contexts (Eisenhardt Citation1989; Welter Citation2011; Alvi, Prasad, and Segara Citation2019), such as refugee camps, where the qualitative methodology enables processes to become transparently observable (Pettigrew Citation1988) that may otherwise remain obscure.

Data collection

We began data collection by gathering secondary data about refugees and refugee camps. The data included media reports (98), UNHCR reports (27), NGO reports (46), UNHCR field updates (41), Kenyan government documents (9), research publications (13), and books (2) about the Dadaab camps. The data was analysed to better understand the specific context of the Dadaab camp complex and our decision to investigate refugee new venture creation was confirmed by the many media reports about refugee entrepreneurship:

The Dadaab camps bring about 14 USDm into the community each year, partly through sales of livestock, milk and other goods to the camps. (Okoth Citation2012: online)

The collection and analysis of secondary data was followed by a field visit (two months, first author) to Kenya. The first author began by interviewing refugee camp managers and aid workers at the UNHCR office, Nairobi. UNHCR staff stay for between four and six weeks in the Dadaab camp complex, followed by several days of rest and recuperation away from the camp. Many UNHCR staff rest and recuperate in Nairobi where they can stock up on supplies and enjoy the amenities of the capital city. In Nairobi, interviews were conducted with Dadaab camp managers (9), aid workers (9), and independent consultants and experts on the Dadaab camp (13). All interviews were recorded in English, lasted between 70 and 120 minutes, and later transcribed. Since the interviews took place in a relaxed environment away from work, informants were encouraged to reflect on and talk at length about their experiences of working in the Dadaab camp complex.

The first author then visited the Dadaab camps and observed the day-to-day tasks, interactions, and dynamics in the UNHCR compound. At the Dadaab camps, the first author stayed in a compound with the same UNHCR staff interviewed in Nairobi. The compound encompasses staff living quarters, offices as well as recreational areas such as a canteen, bar, and gym. Observations were recorded in a field diary (41 pages). The plan for this phase of data collection was to interview refugees in the Dadaab camps. However, this proved extremely difficult. The high level of camp security and restrictions on the movement of visitors into and out of the camp prevented the first author’s free movement in the camp. An aid worker explained the limited opportunities for the first author to interact directly with refugees:

You have the same restrictions as all the other staff there. The same restrictions that I have when I go: you can’t leave the [UNHCR] compound. So, you can’t just walk around in the camp and talk to refugees. We wouldn’t let you do that. If you have a big budget, you could hire a guard and a driver and an armoured vehicle and drive around in the camp. But we couldn’t let you get out of the car and just walk around. There might be one or two opportunities per month I’d say where if you’re lucky you could talk to some of the refugee leaders. (Interview, aid worker 3)

Although a small number of encounters with refugees in the Dadaab camps were engineered through group discussions organized by aid workers (4 encounters, 14 refugees), the brief conversations that ensued quickly revealed refugees’ discomfort with being interviewed in the presence of the armed camp guards. Noticing the pervasiveness of mobile phones, the first author suggested phone interviews with the refugees as a method to collect primary data. Mobile phone interviews were conducted with refugee informants at their convenience – each interview commenced with an explanation of the aims of the research and securing informants’ written consent to voluntarily participate in the research (Webster, Lewis, and Brown Citation2014). In addition to interviewing RCEs (5), i.e. refugees that had established business ventures in the camp, refugees (9) who were at the time not operating a business were also interviewed. The latter were integral to understanding the Dadaab camps formal rules and social norms in addition to providing consumers’ perspectives of RCEs.

The interviews, conducted in English – refugees typically converse in English, Somaali and Swahili – and recorded, lasted between 40 and 90 minutes and pertained to refugees’ life in the camp, their hopes for the future, and their perspective on their current situation. The psychological well-being of participants was of primary concern as many refugees suffer from the trauma of their displacement. The first author, drawing on prior work experience with refugees and extensive desk research on the Somali refugee population, adopted a respectful approach that considered informants to be experts (Dykstra-DeVette and Canary Citation2018) of life in the camps, leaving it up to each informant to volunteer information on sensitive topics such as their life history, journey to the Dadaab camp complex, family and daily activities. In addition, two informants supplied video recordings of episodes of their daily life in Dadaab camp (7 videos). All observations, impressions, sketches and photographs were recorded in the first author’s field diary.

No personal or identifying information was recorded (Webster, Lewis, and Brown Citation2014), for example, codes were assigned to all participants and interview recordings and transcripts stored securely on a password protected laptop computer. Each informant was offered the transcribed version of their interview and images taken, and given the opportunity to withdraw their contribution to the research at any point. Interviews were transcribed by the first author to ensure accuracy and to avoid transmitting the data elsewhere. Finally, and to contextualize any exposure that refugees may have risked from participation in the research, it is important to note refugee camps are characterized by a distinctive organizational structure and management principles (de la Chaux et al. Citation2018). Refugees’ businesses are visible to anyone entering the camp and, although illicit, are a taken for granted part of camp life.

Data analysis

Data analysis began with constructing a narrative account (Langley Citation1999) of what the first author had seen, heard, and experienced during camp visits. The initial part of the analysis focused on structuring and establishing a shared understanding of the data by the first and second author.

Using the data analysis software NVivo (Bazely and Jackson Citation2007), and informed by the narrative account, we then identified all references to entrepreneurship. Without being prompted, most interviews with camp managers, aid workers, and refugees referred to the RCEs and markets. We identified a total of 726 excerpts, for example, descriptions of the types of businesses in the camp and informants’ sense of the hopelessness that preceded entrepreneurship.

Next, guided by grounded theory principles (Charmaz Citation2014) the excerpts were grouped into first-order codes. The process involved iterative cycling between the raw data, narrative account, and provisional coding. We especially focused on ensuring that the codes were mutually exclusive, i.e. that excerpts could not be grouped into two codes, but also collectively exhaustive. For example, instances of reselling food rations and aid items, and adapting and selling donated clothing were subsumed under the first-order category ‘reselling food rations and aid packages’. We concluded this phase of data analysis with 16 first-order codes. We then abstracted from the data by arranging the first-order codes into second-order categories, namely the ‘interpretations of interpretations’ (Van Maanen Citation2002, 104). As in the previous step, we focused on ensuring the mutual exclusiveness and collective exhaustiveness of the categories and culminated with 7 second-order categories. The first-order code ‘reselling food rations and aid packages’ was linked with ‘organizing financial transactions through ration cards’, and ‘redefining refugee camp personnel roles’, and together labelled the second-order category ‘repurposing refugee camp humanitarian practices’.

Finally, aggregate theoretical dimensions were abstracted from the data, first-order codes and second-order categories. The process involved repeated discussions between the authors, iteration between the raw data and the codes, codes and categories, and rereading of the institutional theory literature. This step of the analysis involved multiple ‘conceptual leaps’ that sought to ‘bridge the gap between empirical data and theory’ (Klag and Langley Citation2013, 150). Several ideas were developed and dismissed until we arrived at the three theoretical constructs that we agreed most adequately explain how and why refugees establish new ventures in the Dadaab camps. Our theoretical model to explain how RCEs navigate institutional misalignment thus brings ‘together many insights, many creative leaps, most small and perhaps a few big’ (Mintzberg Citation2005, 370). The data structure is presented in .

Findings

Three mechanisms are theorized to explain RCE new venture creation when formal institutions impede entrepreneurship. First, RCEs appeal to blind spots in formal institutions and enable refugees to reclaim economic agency and self-determination, increasing refugees’ desire for purpose and autonomy and thus strengthening informal institutions that support entrepreneurship. Second, RCEs reframe institutional practices and places by repurposing monthly food rations, aid items and places in the camps and in doing so recombine aspects of formal and informal institutions. Finally, RCEs maintain institutional misalignment between humanitarian aid practices and domestic regulations on the one hand, and informal entrepreneurship institutions on the other in order to exploit the advantages of their refugee status and economic agency. In addition to the empirical data presented in this section, supplementary data is presented in .

Table 1. Data to illustrate theoretical dimensions

Appealing to blind spots in formal institutions

After a few months in the Dadaab camps, refugees soon tire of the monotony of UNHCR monthly food rations, aid items and camp life. RCEs recognize opportunities in fellow refugees’ demand for goods and services not provided by the UNHCR aid packages. Moreover, RCEs showcase how establishing a new venture helps them to reclaim purpose and self-determination. By appealing to these blind spots in humanitarian aid practices, norms and values that support entrepreneurship are strengthened among the wider refugee population in the camps.

Reclaiming refugee economic agency

In response to the wide-spread refugee dissatisfaction with monthly food rations and aid items, RCEs established new ventures to sell goods and services to refugees. Being able to exercise choice reframes refugees as consumers with the economic power to buy more varied food, personal care products, services, and any essentials not provided in the food rations and aid packages. An aid worker reflects on when the first RCEs appeared in the camp:

Initially mostly cafes appeared. UNHCR programming didn’t really foresee social spaces. They provide for the essential needs but, social spaces weren’t really part of that. (Interview, camp manager 1)

Our informants commented on the low quality and culturally inappropriate monthly food rations. Refugees are suspicious that the rice is ‘cheap plastic rice’ as it takes several hours to cook, and explained that the food rations do not correspond to their traditional diet of vegetables and meat. Food is important in Somali culture and traditional meals require specific ingredients and many hours of preparation (Horst Citation2008). Family interactions occur around the preparation and consumption of traditional meals that bring the extended family together. RCEs responded to the demand for higher quality and more culturally appropriate food by establishing new ventures to sell fruit and vegetables, and cafés to serve traditional Somali meals:

The kind of food that are given to the refugee camp is not favorable. It’s not for human consumption, mostly. So mostly, it’s like the maize flour, when I look at it, it was transported for a long time. So mostly the refugees collect from the distribution. What they do is, they give it to the animals. The goats, the cows. But for them, mostly because for the Somali community they want pasta, rice, wheat flour … so they take from the distribution center, they give it to the animals to feed them. (Interview, refugee 7)

Second, RCEs respond to fellow refugee demand for a wider variety of goods and services than provided in the food rations and aid packages. A refugee informant describes how the food rations had barely changed for decades. In response, RCEs sell different vegetables and meats to supplement food rations with more choice:

I do not want the food they provide for us. It is the same, always the same. It is always sorghum, wheat, and cooking oil. Would you want to eat the same meal every day for 20 years? I mean, come on, what do you expect? It is not so surprising about the food rations. (Interview, refugee 6)

Most of the refugees that have stayed for a long time, like 24 years, have had businesses to grow because mostly they don’t rely on the food distribution that is given by the WFP. Because you don’t get the right services. And also, for example, the feeding program, people need to get something like meat or like vegetables. Most of the people pay for services, they want meat, they want vegetables. (Interview, RCE 1)

The RCEs have also recognized opportunities for new service ventures, for example, barbers, hairdressers and beauty parlours, to respond to the cultural importance of grooming in Somali culture, as one female Somali explained. Further, cafés and tea houses have become central social meeting places. None of these personal and social needs are addressed by aid and formal camp design.

Responding to refugee anguish

In addition to reclaiming refugee economic agency, RCEs also respond to refugee concerns about camp life that are not endorsed in formal institutions. Nearly 30 years after the first Dadaab camp opened, the Government of Kenya continues to refer to the camp complex as temporary in official statements, and the UNHCR and partners implicitly support this view through humanitarian aid practices. Many refugees however, have lived in the camps for decades and, from their experience, do not consider the camp to be temporary. Several reports describe how refugees have adopted negative coping mechanisms to manage boredom and hopelessness concerning their future (Perous de Montclos and Kagwanja Citation2000; Rawlence Citation2016).

Through new venture creation, RCEs provide an alternative perspective on camp life as a semi-permanent place of opportunity, thus instilling a sense of purpose among fellow refugees and addressing both the material and psychological needs of refugees in the camps. First, RCEs gain a sense of purpose by establishing new ventures with many informants explaining that their business was the ‘only reason to get up in the morning’. This also helps the aspirations of refugee youth. Inspired by heroic RCE success stories that diffuse across the camp, young refugees become motivated to start their own new ventures and regain hope about their future life in the camp. A refugee owner of a successful internet café in the camp recalled how he ‘used to push the donkey cart all around to sell firestones. That is how I started. I had seen what others had done. I knew it was possible to work my way up and become a business owner’ (Interview, RCE 7). Successful RCEs also employ young refugees in their business ventures, thus providing unemployed youth with something to do and a career path:

When you are a young child you can start helping out your parents with their business. And that is how you learn. Then, when you graduate, maybe you can get a small job. Maybe you sell vegetables in the street. Then, you can take more and more responsibility and maybe one day you can make your own business. (Interview, refugee 2)

Second, although the Kenyan Government and UNHCR emphasize that the Dadaab camp complex is temporary, to establish even the smallest, informal new venture requires forward planning. As one refugee informant summarized: ‘When you are a business owner you need faith. You need faith in the future’ (Interview, refugee 4). Through their new ventures, RCEs promote the belief that the camp is not temporary, for example, by acquiring new venture artefacts and buying stock: Restaurants and bars procure tables and chairs; beauty parlours buy hairdressing and manicure equipment; and shops stock goods to sell. RCE 3, seated in front of his shop with several hundred pairs of shoes in all shapes and sizes during our first encounter explains:

[Refugee]: I sell shoes. Many, many, in all sizes and for women, and girls, and men, and children. (…)

[Interviewer]: But what if the camp is shut down next week? Then you have all of these shoes in stock and nobody to buy them.

[Refugee]: No, but this will not be the case. We will be here for long. And the people, they will always need shoes.

RCEs investment in new ventures, and consequently into a future in the camp, contrasts with the official narrative that the Dadaab camp complex is temporary and simultaneously responds to refugees hopes for a better future. As one refugee in his mid-twenties explains:

“I was born in the camp, I have never been anywhere else. But they [UNHCR] keep saying we need to return [to Somalia]. Return to where? I ask them. This [Dadaab camp] is my home.” (Interview, refugee 6).

By investing in new ventures, and thus into a future at the Dadaab camps, RCEs promote the belief that, after nearly 30 years of existence, the camp complex is a permanent place, a view that is neither addressed by formal communication about the Dadaab camp complex nor the UNHCR, yet confirms the sentiments of many refugees.

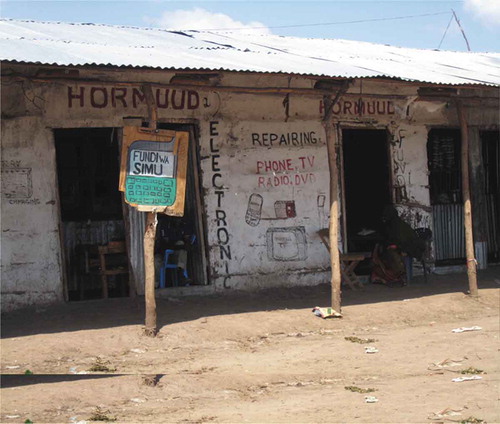

Finally, entrepreneurship enables refugees to reclaim some individuality. The refugee-led new ventures mean that refugees can choose what they want to eat based on their personal preferences. A female refugee informant recounted her weekly shop to explain how she can cook typical Somali pasta and rice dishes, rather than use the sorghum in the monthly food ration: ‘I get a half of sugar for Ksh2 300. And also, one box of pasta, Ksh1 500. And I also got a half of rice, Ksh1 800. And also, the vegetables, they cost Ksh4 000ʹ (Interview, refugee 2). The RCEs also enable refugees to express their individuality, for example, by purchasing clothing to their personal taste rather than wearing standardized clothing distributed by a UN agency. In addition, RCEs display their individuality through their business ventures – the shops carry the owners’ signs and vibrantly decorated. (see ).

Reframing institutional practices and spaces

As informal norms and values that support entrepreneurship are strengthened among the refugee population, RCEs also repurpose aid into resources, places in the camp become markets, and formal camp boundaries evaded. These actions further strengthen informal institutions that support entrepreneurship in the camps.

Repurposing refugee camp humanitarian aid practices

RCEs repurpose monthly food rations and aid packages into resources for new venture creation. To illustrate, each refugee family unit is entitled to a monthly food ration that they collect from a designated food distribution centre inside the camps. Groups of refugees gather at the exits of the distribution centres, ready to barter for unwanted items, and to sell porter services to carry the food rations and aid items from the centres. Standardized aid items are also bartered, adapted and sold. These activities generate RCE income:

For the rainy season, UNICEF were distributing rain coats for children. They distributed one size of raincoats for all children, no matter if they were 5 or 12 years old. Then immediately a few women started tailoring the raincoats to the children’s different sizes and made a business of it. (Interview, aid worker 2)

Second, RCEs have repurposed the UNHCR ration cards that certify the eligibility of each refugee family for the monthly food rations and aid packages. Every refugee family, upon arrival at the camp, is given a ration card. RCEs use the ration cards as currency and debt security. At Dadaab camps, refugees sell excess ration cards that they have appropriated, for example, from deceased family members whose death was not registered with UNHCR, or relatives who have secretly left – usually to attempt migration to Europe. In the Dadaab camp complex, a ration card, depending on family size, is worth between Ksh5 000 and Ksh10 000 (USD50 to 100); enough finance to set up a business venture in the camp:

People will for example take a loan at a store. They’ll get food but have no money and they’ll leave their ration card to the store owner as security until they can pay back. So, then it’s understood that the store owner can go and collect the person’s food ration until that person is able to pay back his or her loan. (Interview, aid worker 5)

In addition to reselling UNHCR food rations, aid items and ration cards, RCEs also persuade camp guards to bring goods into the camp. The official role of camp guards is to secure the camp boundary in order to provide the safe-haven that the refugee camp is intended to be from a humanitarian perspective. RCEs make facilitation payments to camp guards to illicitly bring goods into and out of the camp from further away towns that refugees cannot travel to. Most camp guards earn very little from their formal employment and facilitation payments supplement their income. An aid worker explains how easily this broader camp guard role is accomplished:

Of course, they [camp guards] know if someone is bringing in crates of tomatoes every day for their business but nobody asks how it all works. It’s highly opaque. Like, I could take my civilian car into the camp even though civilian cars aren’t allowed in the camp. I know one of the guards at the gate and I would tell him that I’m coming in tomorrow because one of my friends is getting married and they want to be driven around the camp. He’d tell me ‘Yeah just be there between 9 and 11 and it’s okay. That’s how it works.’ (Interview, aid worker 4)

A clandestine supplier network operates in which RCEs pay camp guards to either bring in, or ‘look the other way’ while goods are illicitly transported into and out of the Dadaab camp complex. In addition, the UNHCR logistics associated with the monthly distribution of food rations and aid items are also brought into RCEs supply networks:

We have trucks that drive into the camp with food aid. They come from Nairobi. When they leave, they are again full of items. It is often the same food that they brought into the camp. We have sold it and it is driven back to Nairobi, where it came from, and then it is resold in the markets there. (Interview, RCE 1)

Reshaping formal refugee camp places

The intention of the formal UNHCR design of the Dadaab camps is to ensure space-efficient refugee housing. The individual land plots allocated to refugees are nearly all identical in size and shape. Over time, RCEs have recognized that a land plot located near a mosque, school, or food distribution centre is an advantageous business location because of high refugee footfall. As a result, markets have developed near places frequently visited by refugees. Refugees describe how they ‘go to the market’ (Interview, refugee 3) and ‘find everything at the market’ (Interview, refugee 8). Although the markets are illicit they make the Dadaab camps look more like a settlement than the temporary protective exile they are intended and designed to be. A camp manager described in a public lecture:

People were showing us that they had a different concept of the space. A different concept of how the settlement should look like. We were building a camp they were building a city. We were building a storage facility for people. They were actually developing … an organic living space. (Interview, camp manager in media report 1)

Furthermore, an informal property rights protection system has evolved to manage land transfer. On arrival at the Dadaab camp complex, refugees are gifted a tent by UNHCR and granted temporary residence on a land plot that formally belongs to the Kenyan State. There is no formal refugee property rights protection. However, over time, refugees deem the tent and land plot to be ‘their property’ and develop informal property rights. As specific land plot sites have become more desirable for economic activity than others, informal property rights regulate tent and land plot use and transfer. For example, refugees may rent their tent and land plot to an RCE and then move in with relatives living in the Dadaab camps, an arrangement that mirrors traditional Somali housing arrangements where extended family live in one compound together:

Pretty quickly, people developed a property market. They rent their tents on the black market. Which is crazy! They’re renting tents and property that do not belong to them in the first place. (Interview, aid worker 2)

If you come first and you get allocated a spot and that later becomes the main road you can rent that space for a lot of money. (Interview, refugee 1)

Although the refugee-led new ventures are not formally recognized, the tent and land plot rental payments incentivize other refugees, particularly the ‘landlords’, to respect land use. The co-location of the new ventures also creates an informal safety net for RCEs at risk from violence and extortion.

Evading refugee camp boundaries

While formal regulations prohibit refugee movement into and out of the Dadaab camp, RCEs need to source goods and services from outside communities to sell to refugees in the camp. In addition to paying camp guards to bring goods into and out of the camp, RCEs also enlist members of the host community to bring goods into the camp. The Dadaab camps refugees and host community are both ethnically Somali and thus share the same language, customs and culture. Their shared ethnicity creates an immediate relationship of trust between the two groups (Horst Citation2008), which facilitates business transactions at the camp boundaries. Specifically, members of the host community are employed by RCEs to travel to Garissa town, approximately 90 km from the camp, to acquire resources and bring them back to the camp complex. RCEs would require a pass to make such a journey and they are rarely given to refugees. An RCE explains his situation:

If you want to do business, or buy something in Garissa, I cannot go. I can only call people there and ask them to get me something. I can even ask the price but, they can trick me. I can call and ask, ‘what is the price of this item?’ If it is Ksh1000 they can say it is Ksh1500. They are also doing business on top of me. So it is very challenging. (Interview, RCE 4)

The flows of goods and services across camp boundaries is however, both ways. The monthly food rations contain products, for example, sugar which although distributed freely inside the camp, is coveted by host communities. Dadaab villagers thus also come into the camp to buy goods from RCEs:

Often the markets inside the camp are cheaper than the markets outside. For some items they are, at least. They call it the ‘duty free’. Especially for sugar, it’s a lot cheaper. (Interview, aid worker 4)

In addition to evading the physical camp boundaries, refugees use mobile telephony to make secure financial transactions inside and outside of the camp. A former long-time aid worker recalls how initially, refugees would smuggle suitcases of cash into and out of the camp to pay suppliers and camp guards. Today, she explains ‘they do all of that with their mobile phones,’ (Interview, consultant 1). Nearly all refugees have a mobile phone and use the MPESA money transfer service. MPESA also enables refugees to receive remittances from relatives and friends in Europe and thus fund purchases in the camp. Although the official currency is the Kenyan shilling, refugees make purchases through MPESA (report 17). Since the service is password protected, storing savings on MPESA is also safer than keeping cash in the camp:

There is an MPESA shop in the market. So, you can transfer money from another place, you can send money. Our brothers and sisters, anyone, can send me money through the MPESA. (Interview, refugee 3)

Many refugees have gone to Europe so now they are giving money back to their family members in the camp to survive. That money will come back into the market so now this is the kind of circulation in the market. (Interview, consultant 2)

Taken together, the reframing institutional practices and places recombines aspects formal humanitarian aid practices and informal institutions that support entrepreneurship in the Dadaab camp complex. For RCEs, the combination of repurposed formal and informal institutions creates a conducive institutional context for opportunity recognition, resource acquisition and venture creation.

Maintaining institutional misalignment

As RCEs benefit from aspects of both formal and informal institutions, they exploit the institutional misalignment between them. For example, RCEs co-opt local government officials and UNHCR aid workers and downplay their economic agency to outsiders in order to maintain the privileges and benefits of humanitarian aid practices.

Co-opting institutional agents in the camp

Although the RCEs’ new ventures are unauthorized, local authority employees visiting the camp do not enforce sanctions and closure. Instead, RCEs pay facilitation payments to police that mirror the taxes that would be due if their illicit businesses were formally registered. In recognition of the substantial wealth RCEs bring to the surrounding host community, local authority employees implicitly condone RCEs in exchange for such facilitation payments. The facilitation payments do not confer formal venture recognition or protection and are an expression of the vulnerability of RCEs vis-à-vis local authorities as the threat of arbitrary arrest and imprisonment is ever-present for all refugees. Whereas nearly all Kenyan businesses in the host community are informal, only 20% of Kenyan informal businesses report paying bribes (World Bank Citation2016) yet all RCEs we interviewed report having to pay such payments regularly. Nonetheless, through regular interaction between RCEs and local authority employees, the RCEs are an increasingly taken-for-granted part of camp life, so much that RCEs refer to the bribes as ‘taxes’:

The Government of Kenya comes sometimes to collect taxes. They come yearly and collect taxes. They do not close the businesses because they collect the tax. (Interview, RCE 4)

They will just come to the market and they will say, for the land, you pay Ksh1 000. They estimate how much taxes you have to pay. They estimate Ksh 3 000 for a normal business. For some of the businesses, they have big sums, they have to pay more than Ksh 10 000. That’s 100. USD Because the refugees have no rights, there is nobody who is protecting them. They will communicate with UNHCR but UNHCR will just say: You are refugee, you don’t have that right, you don’t have this right. (Interview, RCE 1)

The RCEs also sell goods and services to UNHCR employees and aid workers. For example, local aid workers are contracted by UNHCR to oversee the distribution of monthly food rations and aid items. Unable to afford meals in the UNHCR canteen, the local aid workers buy food from the RCEs. As one informant emphasizes, ‘you can find the best meals in North Eastern Province in the camp here’ (Interview, aid worker 1). The aid workers thus implicitly support RCEs by shopping and dining at the camp markets and restaurants. Although careful to avoid explicitly endorsing the RCEs, local authority employees, UNHCR camp managers and local aid workers condone RCEs new venture creation.

Endorsing humanitarian aid practices

When interacting with representatives from the Kenyan government and non-UNHCR agencies however, the RCEs dissemble. First, RCEs downplay their economic agency. For example, in conversations with representatives from non-UNHCR agencies, RCEs explained that: ‘life in Dadaab is very hard’ (Interview, RCE 3) and that, ‘is it very difficult for us here’ (Interview, RCE 7). During a meeting between visiting representatives of a European donor government and refugees, refugees altered their posture and tone of voice:

They [RCEs] become so much more submissive. In the meeting with [donor government] they’ve somehow made themselves smaller and their faces are all solemn and serious. They speak in a much more pleading tone and everything they say feels fake. It’s like they are playing the victim role that everyone is expecting of them. Even their vocabulary changes. None of them would use words like ‘acute malnutrition’ in their everyday lives. (Field notes, day 19)

Moreover, a survey conducted by donor government representatives confirmed that RCEs neglect to mention their income from business activity when asked about the disposable cash available to them every month (NGO field report 1). A consultant recounts his experience of trying to conduct a market analysis in the camp:

It has been extremely challenging to come up with realistic estimates on the scope of business activity. As soon as we get to the market with our iPads, the shops shut down immediately. Nobody will talk. When you ask them, they pretend they don’t have a business and that they don’t know what you are talking about. (Interview, independent consultant 2)

During refugee camp visits from Kenyan government agencies and international donors, RCEs stressed how essential UNHCR and international NGO help had been for their survival and how much their lives depended on the goodwill of the Kenyan government and international donors. For example, RCEs talked to such visitors about the size of their families, especially the number of dependent children and elderly members (field notes day 19 and day 5). In a personal account of the camp, Rawlence (Citation2016, 91) reflected: ‘docile, disempowered refugees do as they are told. They hesitate before authority and plead for their rights in the language of mercy’.

By co-opting institutional agents to condone entrepreneurship in the camps and also downplaying the extent of economic activity and emphasizing their vulnerability and dependency to outside visitors, RCEs exploit the advantageous aspects of humanitarian aid practices and informal institutions that support entrepreneurship.

Discussion and contributions

Research in low and lower middle-income countries to date has focused on how ill-defined and ambiguous formal institutions, and contradictions between formal and informal institutions, impede entrepreneurship (Estrin, Korosteleva, and Mickiewicz Citation2013; Mair, Martí, and Ventresca Citation2012; Sutter et al. Citation2013). In our case study, humanitarian aid practices impede entrepreneurial opportunities by meeting refugees’ basic needs and domestic legislation impedes refugee access to business and work permits. This creates an institutional context in which formal institutions impede entrepreneurship, yet opportunity recognition, resource acquisition and new venture creation thrive in the Dadaab camps. From the analysis of empirical data gathered from informants connected with and living in the Dadaab camp complex, we theorized that RCEs employ mechanisms to erode formal institutions, recombine aspects of formal and informal institutions, and exploit institutional misalignment, thus fostering a complex institutional context. Institutional misalignment (Webb et al. Citation2009) created a context in which entrepreneurs appropriated aspects of formal and informal institutions (Williams and Shahid Citation2016) and entrepreneurship flourished.

Furthermore, we find that RCEs sought to maintain institutional misalignment. In the camps, RCEs proactively identified opportunities, acquired resources and established new ventures. Towards representatives from donor governments and journalists, in contrast, RCEs acted as vulnerable victims, thereby endorsing the need for humanitarian aid. These divergent behaviours were adopted because the interests of RCEs are paradoxical: rather than rejecting formal humanitarian aid practices in their entirety, RCEs seek to maintain specific aspects that afford them with privileges, such as their legally protected refugee status and access to monthly food rations and aid items. Simultaneously, RCEs erode formal institutions by establishing new ventures, making facilitation payments to intermediaries, and trading with UNHCR and NGO employees. The findings introduce a new perspective on the relationship between entrepreneurship and institutional context by elucidating how entrepreneurship can flourish as entrepreneurs strategically manoeuvre between misaligned formal and informal institutions.

Exploiting and maintaining institutional misalignment

Our research makes two contributions to theory. Prior research findings from research conducted in low and lower middle-income countries has noted how formal institutions impede entrepreneurship (Alvi, Prasad, and Segara Citation2019) and that entrepreneurs are prevented from venture creation as a result of complex informal institutional expectations (Mair, Martí, and Ventresca Citation2012; Sutter et al. Citation2013). Our analysis in contrast, finds that entrepreneurs can thrive in complex and ambiguous institutional contexts by strategically eroding, combining, and managing misaligned institutions.

Although institutional environments in low and lower middle-income economies have been described as ill-defined and ambiguous (Chakrabarty Citation2009; Mair, Martí, and Ventresca Citation2012; Puffer, McCarthy, and Boisot Citation2010), less attention has been paid to how entrepreneurs cope with such distinctive institutional contexts. The small number of prior studies suggest that entrepreneurs primarily react to ambiguous and conflicting institutional demands by complying with competing institutional demands (Williams and Shahid Citation2016), avoiding them (Sutter et al. Citation2013) or defying demands that are too ambiguous (Uzo and Mair Citation2014). Much of this research focuses relatively exclusively on business registration as a proxy for venture creation and has arrived at two conclusions. First, that a clear institutional context is preferable to institutional ambiguity and complexity (e.g. Mair, Martí, and Ventresca Citation2012; Sutter et al. Citation2013) because such conditions reduce institution enforcement costs (Boettke and Coyne Citation2009; Weingast Citation1995). Second, a context in which formal and informal institutions support each other is preferable because institutional misalignment impedes entrepreneurship. For example, while formal laws have allowed women to run businesses, female entrepreneurship has been impeded by informal cultural and religious norms (Mair, Martí, and Ventresca Citation2012) and local traditions (Welter and Smallbone Citation2008). Our research offers a different conclusion by explaining how entrepreneurs exploit and maintain institutional misalignment when it serves their interests. In our case, RCEs eroded dominant institutions when they did not serve their interests and endorsed informal institutions that did. RCEs instrumentally drew on aspects of both formal and informal institutions, even when they conflicted, and thus exploited and maintained institutional misalignment.

Institutional theory posits that when actors’ interests are served by formal institutions, actors endorse and thus maintain them whereas, when this is not the case, efforts are undertaken to change institutions (Dacin, Goodstein, and Scott Citation2002; Dacin, Munir, and Tracey Citation2010; Lawrence, Suddaby, and Leca Citation2009; Zilber Citation2009). From our empirical case, however, emerges a different outcome, wherein actors simultaneously endorse aspects of formal institutions, while eroding others by promoting conflicting informal institutions. The underlying explanation is that actors’ interests are complex. In our case, RCEs on the one hand strive for autonomy and self-determination, not afforded by humanitarian aid practices, yet seek to preserve their legal refugee status conferred by humanitarian aid practices. The outcome is an institutional context in which a key group of actors, in our case RCEs, seek to maintain institutional misalignment.

Entrepreneurship in low and lower middle-income countries

The second contribution is to elucidate entrepreneur motivation in low and lower middle-income countries. Prior research notes that entrepreneurs in low and lower middle-income countries are motivated by survival. Individuals trapped in cycles of poverty focus on day-to-day survival (Bruton, Ahlstrom, and Si Citation2015) and are constrained by resource scarcity, such as, lack of capital to invest in new ventures with growth potential (Bruton, Ahlstrom, and Si Citation2015; Carsrud and Brännback Citation2011). These conditions prevent entrepreneurs in low and lower middle-income countries transitioning from subsistence to growth entrepreneurship (Hall et al. Citation2012; Sutter, Bruton, and Chen Citation2019).

In our analysis we find that RCEs are not motivated by survival because humanitarian aid freely provides access to goods and services that meet basic needs. Instead, the motivation for entrepreneurship is to reclaim economic agency and self-determination. RCEs reclaim economic agency by acquiring resources and creating new ventures and express their individuality through the design of their new venture. Informal norms and values that support entrepreneurship are further strengthened as refugees purchase goods, such as food and clothing, and services, such as beauty treatments, from the RCEs. Also, RCEs do not need to sell survival goods as these are provided by humanitarian aid. Instead, RCEs establish new ventures that retail discretionary products and services. Our research therefore extends the literature by elucidating how new venture creation in low and lower middle-income countries is not limited to subsistence entrepreneurship (Carsrud and Brännback Citation2011) and the provision of survival goods and services. We propose that our understanding of entrepreneur motivation in low and lower middle-income countries be expanded to include autonomy, individuality and self-determination. Echoing Mead’s (Citation1934) proposition that individuals have a fundamental need for self-definition, we posit that even in contexts of extreme poverty, the desire for identity and self-expression constitute important motivators for entrepreneurship.

Implications for practice

Our research serves as a powerful reminder that in even the most difficult contexts, people find ways to improve the conditions in which they, and others, live. The close engagement of the first author with the empirical context leads to four suggestions for practice. First, while the formal institutional impediments to entrepreneurship may have deterred some aspiring RCEs, they did not suppress entrepreneurship. Motivated to reclaim economic agency and self-determination, the RCEs established new ventures to sell a wide range of products and services. In many countries, humanitarian emergency aid provides access to medical care, shelter, food and water. In recognition of the desire for economic agency and self-determination, policy-makers could invest in developing policies to support and partner with RCEs to provide access to basic and discretionary good and services.

Second, humanitarian emergency aid is intended to provide a temporary solution, yet in protracted crises, the initially temporary structures and practices become permanent and taken-for-granted. Whereas economic agency and self-determination might not appear important when survival is threatened, it is not long before autonomy and self-expression become central to refugee concerns. After more than 25 years, humanitarian emergency structures remain in place and the refugees of the Dadaab camps continue to be excluded from planning and decision-making on how the refugee camp, their home, is organized. The suggestion for policy makers is to design structures to engage the victims of humanitarian emergency, crisis or disaster in designing responses and solutions. For example, in consultation with refugees, the need for business premises, social spaces, agricultural plots to grow subsistence crops, and access to technology could be built into the layout of refugee camps.

The RCE narratives demonstrate that new venture creation requires ingenuity to overcome the impediments to entrepreneurship – a fruit vendor might simultaneously have to be a mentor and skilled navigator of institutional misalignment. Our third suggestion for practice is to develop strategies to share knowledge about how entrepreneurs overcome impediments to entrepreneurship and the design adaptations of sustainable new products, services and innovations in low and lower middle-income countries.

Finally, our research elucidates how the forcibly displaced contribute to their host countries through new venture creation. RCEs in the Dadaab camps generate an annual turnover of several million US Dollars (Okoth Citation2012). Rather than stifling RCEs through restrictive policies, host governments might consider how to move towards a policy environment that ensures that the value created by RCEs for the camps and surrounding host communities contribute more broadly to the host country. Examples of policies that could help translate refugee businesses into added value for the host community include providing special business permits for RCEs, access to business development services and finance for registered refugee businesses and, in return, taxation of refugee businesses. Such policies acknowledge the potential of refugee camps to be sites for regional development.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

The qualitative case study of how and why RCEs establish new ventures in the Dadaab camp complex offers an insight into entrepreneurship in an extreme context. As with any method, the qualitative case study research design has limitations, three of which are of particular relevance to our research.

First, one of the aims of case study research is to gain a rich understanding of the processes at play in a given context (Eisenhardt Citation1989). The subsequent challenge, and even more so for research in extreme contexts, is to generalize the findings and connect them to other contexts. We address this limitation by employing the principles of grounded theory (Charmaz Citation2014) to abstract aggregate theoretical constructs of eroding formal institutions, recombining formal and informal institutions and exploiting institutional misalignment. In this way the empirical data anchors theoretical constructs that have the potential to be generalizable to other contexts in which institutions are misaligned, for example, transition, disaster and occupied regions. A second limitation of qualitative research is the subjectivity inherent to the approach, particularly in the data collected and how the researcher(s) make sense of the data (Morris et al. Citation1999). The generalizations, so the concern, can thus easily be distorted. We addressed this concern in our research design. Whereas the first author collected the data and gained in-depth familiarity with the empirical context, the distance from the field of the second author provided an outsider perspective throughout the research. We were thus able to challenge and question the other’s assumptions based on our relative distances from the field. A third limitation concerns the extent to which theorizing from RCEs is relevant to other theories. The findings however, develop theory relating to institutional misalignment between formal and informal institutions, and concerning entrepreneur motivation. Institutional misalignment and entrepreneur motivation are relevant to other theories, for example, international entrepreneurship, indigenous entrepreneurship, and family firms.

We conclude with three suggestions for future research. First, The UNHCR reports that there are more than 70 million forcibly displaced persons (UNHCR Citation2019) of which the Dadaab camps accommodate approximately 211 000 people. While humanitarian aid practices are universal, country level formal institutions differ. Research in a different camp where formal institutions protect economic freedoms and property rights would deepen knowledge about opportunity recognition and resource acquisition in low and lower middle-income contexts. Comparative research between several refugee camps could identify an optimum refugee camp institutional framework. Second, RCEs made use of available resources to design new products and services. Prior research has explored how entrepreneurs use bricolage (Baker and Nelson Citation2005) and effectuation (Sarasvathy Citation2009) to fashion products and services from resources to hand. Further research to investigate innovation processes in resource constrained environments would be both theoretically and practically useful. Finally, we theorized that motivations to reclaim economic agency and self-determination were key to RCEs. This raises the question to what extent reclaiming economic agency and self-determination explain other forms of entrepreneurship, for example, social, indigenous, and women’s entrepreneurship.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. Okoth provides the only quantitative estimate of the size of the Dadaab refugee camps markets to date. Although not a recent estimate field visits confirm that, years later, a high level of economic activity is sustained and attest to the continued relevance of Okoth’s estimates.

2. Although the World Bank offers different methods, the classification of countries according to income-levels (as of 2018, low income: GNI per capita of $1,025 or less; lower middle-income economies: $1,026 – $3,995; upper middle-income: $3,996 – $12,375; high-income economies: $12,376 and above) has become the most frequently used approach and is regularly adopted by academia, government, and industry. Classifications are based on the Atlas calculation method and adjusted annually.

3. Although forcibly displaced are de jure able to apply for a business permit, the application requires a personal visit to the registration office which is located outside the perimeters of the camp. As permission to leave the camp is rarely given to refugees on grounds other than medical or educational reasons, de facto refugees are rarely able to obtain a business permit.

References

- Ahlstrom, D., and G. D. Bruton. 2006. “Venture Capital in Emerging Economies: Networks and Institutional Change.” Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 30 (2): 299–320. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00122.x.

- Al-Dajani, H., H. Akbar, S. Carter, and E. Shaw. 2019. “Defying Contextual Embeddedness: Evidence from Displaced Female Entrepreneurs in Jordan.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 31 (3–4): 198–212. doi:10.1080/08985626.2018.1551788.

- Alvi, F. H., A. Prasad, and P. Segara. 2019. “The Political Embeddedness of Entrepreneurship in Extreme Contexts: The Case of the West Bank.” Journal of Business Ethics 157 (1): 279–292. doi:10.1007/s10551-017-3637-9.

- Baker, T., and R. E. Nelson. 2005. “Making Something From Nothing: Resource Construction Through Entrepreneurial Bricolage.” Administrative Science Quarterly 50 (3): 329–366. doi:10.2189/asqu.2005.50.3.329.

- Bazely, P., and K. Jackson. 2007. Qualitative Data Analysis with Nvivo. London: Sage.

- Betts, A., L. Bloom, J. Kaplan, and N. Omata. 2016. Refugee Economies: Forced Displacement and Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bizri, R. M. 2017. “Refugee Entrepreneurship: A Social Capital Perspective.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 29 (9–10): 847–868. doi:10.1080/08985626.2017.1364787.

- Boettke, P. J., and C. J. Coyne. 2009. “Context Matters: Institutions and Entrepreneurship.” Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship 5 (3): 135–209. doi:10.1561/0300000018.

- Bruton, G. D., D. Ahlstrom, and S. Si. 2015. “Entrepreneurship, Poverty, and Asia: Moving beyond Subsistence Entrepreneurship.” Asia Pacific Journal of Management 32 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1007/s10490-014-9404-x.

- Bruton, G. D., I. Filatotchev, S. Si, and M. Wright. 2013. “Entrepreneurship and Strategy in Emerging Economies.” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 7 (3): 169–180. doi:10.1002/sej.1159.

- Carsrud, A., and M. Brännback. 2011. “Entrepreneurial Motivations: What Do We Still Need to Know?” Journal of Small Business Management 49 (1): 9–26. doi:10.1111/j.1540-627X.2010.00312.x.

- Chakrabarty, S. 2009. “The Influence of National Culture and Institutional Voids on Family Ownership of Large Firms: A Country Level Empirical Study.” Journal of International Management 15 (1): 32–45. doi:10.1016/j.intman.2008.06.002.

- Charmaz, K. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. London: Sage.