Abstract

Utilizing theories of silence and silencing that rely on art therapy as a means of overcoming trauma, this essay argues that the two written autobiographies of second-wave feminist visual artist Judy Chicago—Through the Flower: My Struggle as a Woman Artist and Beyond the Flower: The Autobiography of a Feminist Artist—can only be read successfully alongside her opus of visual life narratives. This argument rests on an analysis of the visual rhetoric of Womanhouse, the Great Ladies series, and the Female Rejection Drawings, read alongside Chicago's published narratives. This essay culminates with the argument that the communally produced installation piece The Dinner Party acts as a personal and communal narrative, as well as a political narrative of the second-wave feminist movement in the US.

Silence and failure

Silence and the failure of a verbal language to communicate her needs as both a woman and an artist permeate Judy Chicago's two written autobiographies, Through the Flower: My Struggle as a Woman Artist and Beyond the Flower: The Autobiography of a Feminist Artist. Hesitancy and even an inability to articulate her emotions verbally, both orally and in writing, have led Chicago to develop her own visual-verbal language, which expresses the intersection of symbols of femininity and power in her visual art. Over a period of approximately a decade, culminating with The Dinner Party, Chicago fought against what she perceived as her verbal limitations by developing a visual iconography. The rhetorical arguments that Chicago constructs visually in her artwork act as multimodal life narratives, extending her written autobiographies and continuing her narrative off the page and into a variety of visual media, thus counteracting what she perceived as confines within written narratives. Furthermore, when read in conjunction with the two autobiographies and Chicago's numerous artists' journals, The Dinner Party, as a visual and multimodal text, offers readers a more complete and complex life narrative than the autobiographies alone can.Footnote1

While the goal of this essay is primarily to argue that autobiography scholars must continue to explore unexpected places and spaces for life narratives through the example of Chicago's body of verbal and nonverbal texts—especially those that exist off the page—a secondary objective is to encourage a rereading of The Dinner Party that explores the ways in which it can be read as a personal, community, and political life narrative. The use of her personal symbols for a juncture between femininity and power in her installation project, The Dinner Party, extended access to Chicago's nonverbal language of iconography, symbolizing intersections of women and power to the hundreds who participated in the crafting of this room-sized piece; many of them likewise did not have access to a language that verbalized their relationship with burgeoning second-wave feminism. The community of women who actively participated in the construction of The Dinner Party was and is extended to include, to varying degrees, viewers who participate in this work of art through both their roles as witnesses to the multimodal discussion of female empowerment and as agents in the ways in which they interact with this artwork as a room-sized piece, through which they actually circulate to interact with the text.

While these layers of participation from both the community of workers and the viewers of the work lead to a reading of the work as a communal life narrative, The Dinner Party holds a unique position as both an artwork and a life narrative, in that it is inextricably linked to the second-wave feminist movement. The Dinner Party certainly extends Chicago's own personal life narrative into her political manifesto on women's rights, but this multimodal text exists as a voice of second-wave feminism both through its content and presentation and via the cyclical history of acceptance and rejection that the work has faced throughout its tumultuous history. Ultimately, Chicago developed her visual language to combat unwanted silences and silencing, and it therefore speaks to and for herself, her political ideals, the community of women who participated in the construction of The Dinner Party, viewers of The Dinner Party, and second-wave feminism as a socio-political movement.

Differently Strong

The February 2007 issue of Art News heralded 2007 as “the year of institutional consciousness-raising,” in honor of the enthusiastic promotion of feminist art at several major national museums, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles (Hoban 108). Phoebe Hoban explains this increase in the acceptance and sponsorship of feminist art by stating that these triumphs are reflective of “the rise of powerful female curators, art historians, and—notably—patrons” (108).

Hoban's assessment of the changing power dynamics within gatekeeping art institutions, however, has far greater implications than she acknowledges in this article. “We're Finally Infiltrating” directly acknowledges the admittance of feminist artwork into established institutions, but indirectly grants societal recognition of the feminist ideologies that these works of art represent. Art critic Pat Mainardi states that “feminist art is political propaganda art which, like all political art, should owe its first allegiance to the political movement whose ideology it shares” (296). Judith Stein clarifies this position: feminist art must also be aware of the “broad movement,” understanding of “the implications of sisterhood” (297). Art historian Lucy R. Lippard, like countless other feminist art critics, maintains that what makes feminist art unique is not a set style, but rather “a value system, a revolutionary strategy, a way of life” (363). In light of these definitions of feminist art as unable to exist without the feminist socio-political movement, Hoban's statement regarding the “official” acceptance of feminist art also denotes a willingness to explore feminist philosophies publicly.

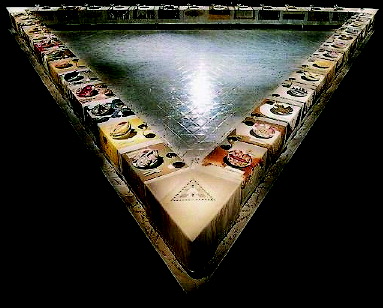

“We're Finally Infiltrating” further celebrates the establishment of the first major museum space in the US dedicated solely to feminist art: the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, inaugurated in March 2007. This center, among the other roles it fulfills, became the permanent home of Chicago's installation piece The Dinner Party (Hoban 109). This acceptance of The Dinner Party decades after its inception signals a ratification of the socio-political issues the text discusses, as well as an understanding and acceptance of the nonverbal language Chicago created to symbolize the praxis of femininity and power. The Dinner Party has become the most recognized—if not the most important—work of feminist art, one that is frequently noted for its evocative imagery, which blends ritualized domesticity with the Christian iconography of the Last Supper (). However, the roots of The Dinner Party and Chicago's innovation of a nonverbal language of female strength lie in the decade prior to the first exhibition of the piece—specifically in the Womanhouse installation, the Great Ladies series, and the Female Rejection Drawings.

FIGURE 1. Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, collection of the artist in cooperation with the Through the Flower Foundation. Image reprinted by permission of the Through the Flower Foundation.

In 1970, well before the commencement of work on The Dinner Party, Chicago developed the Feminist Art Program at Fresno State College as “an art community of women who would implement feminist theories and practices to create work based on their common experiences in society” (Wilding, “Feminist” 32). In 1971, the program moved to the California Institute of the Arts, where Chicago became co-director and artistic collaborator with Miriam Schapiro (39). The classroom experience of this program included classic consciousness-raising activities, such as sitting in a circle and allowing each person to voice her thoughts on a selected topic (Schapiro 247).

During these two years at Fresno State College and the California Institute of the Arts, Chicago began to clarify her commitment to facilitating verbal and visual discussions that led to voicing women's unspoken issues and concerns; however, she was focused on attaining this expression through dominant, masculinist discourse styles, as opposed to mining the rich traditions of women's forms of communication. The main project to emerge from this short-lived program grew out of just such a consciousness-raising experience: an installation project entitled Womanhouse, which filled an abandoned mansion in downtown Los Angeles (Schapiro 248). In the catalog for Womanhouse, Chicago and Schapiro wrote that: “the aim of the Feminist Art Program is to help women restructure their personalities to be more consistent with their desires to be artists” (1). One of the ways in which the two organizers wanted to achieve this goal was by “teach[ing] women to use power equipment, tools and building techniques” (1). Chicago further argued that “women do not usually have sufficient drive and ambition to keep them at a job when it becomes frustrating” (Through 105).

Chicago and Schapiro also stated that: “Womanhouse became the repository of the daydreams women have as they wash, bake, cook, sew, clean and iron their lives away” (Womanhouse 2). Lippard recalls that: “the project included a dollhouse room, a menstruation bathroom, a bridal staircase, a nude womannequin emerging from a (linen) closet, a pink kitchen with fried egg-breast décor, and an elaborate bedroom in which a seated woman perpetually made herself up and brushed her hair” (57). For Lippard, “women make art to escape, overwhelm, or transform daily realities[,]… so it makes sense that those women artists who do focus on domestic imagery often seem to be taking off from, rather than getting off on, the implications of floors and brooms and dirty laundry. They work from such imagery because it's there, because it's what they know best, because they can't escape it” (56). Despite the overwhelming incorporation of masculinized methods and themes into the domestic as a means of discussing women's issues, Womanhouse was, according to Lippard, “an immense and immensely successful project [that] attempt[ed] to concretize the fantasies and oppressions of women's experience” (57).

Chicago's desire for her students to “restructure their personalities” to align more closely with the societal definition of “artist” is not, however, unique to the art programs that she built or to her and Schapiro's views on art-making at that time. In reaction to the millennia of devaluation of women's arts, second-wave feminists set off in droves to find, name, study, and write about historic foremothers who could act as role models for contemporary women. This reclamation of women artists included those who participated in the visual domestic crafts of weaving, quilting, and fancy embroidery, on the basis that such pieces were created skillfully and had high aesthetic value, and thus should be viewed as successful works of art, despite being traditionally produced for utilitarian purposes. As Gloria Steinem stated in her discussion of changes within language that occurred as a result of feminism: “art used to be definable as what men created. Crafts were made by women and natives. Only recently have we discovered they are the same” (150). Women artists traditionally struggled to have their artwork accepted as the same as that produced by men, rather than being recognized as differently skilled, accomplished, or strong.

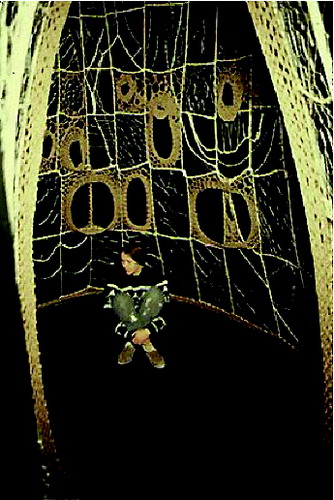

Most of the creators of Womanhouse appear to have taken to heart Chicago and Schapiro's statement admonishing the artists to restructure their thinking—the subtext being that thinking differently for them meant thinking in a more masculine manner. Thus, they went on to present the subject of domestic oppression in the most confrontational ways they could imagine. While this rejection of domestic craft was almost complete within the space of Womanhouse, there is a notable exception: Faith Wilding's Crocheted Environment. The ways in which this one room differed from the others had a great influence over Chicago and her later works. Wilding crocheted a large dome-shaped interior to one of the Womanhouse rooms, which viewers entered and could sit or stay in for as long as they liked (). She wrote that: “our female ancestors first built themselves and their families round-shaped shelters. These were protective environments, often woven out of grasses, branches or weeds. I think of my environment as linked in form and feeling with those primitive womb-shelters, but with the added freedom of not being functional” (Wilding, “Crocheted”).

FIGURE 2. Faith Wilding, Crocheted Environment from the Womanhouse instillation, collection of the artist. Image reprinted by permission of the artist.

When first viewed, Crocheted Environment seems to be made of homespun cobwebs, which drape down from the ceiling to form an airy hogan-like structure. Wilding's textile text speaks less about accusations relating to domestic entrapment and more toward creating safe spaces for women. In this work of art, Wilding opens a discussion on issues of safety and investigates from whence a woman's sense of safety grows. Harkening back to the hogan as a dwelling women wove for the safety of their families, Wilding reminds viewers of the need to create safe spaces, even in the midst of turmoil.

While the women around her explore the hostilities and dangers of domestic life, Wilding creates a sheltered space for safe dialogue. In 1970 and 1971, Chicago and Schapiro were advocating utilizing masculine strength and means of art-making as a way for women artists to make headway in the art community, but Wilding's work reminded the entire class of the Feminist Art Program and the many visitors to Womanhouse that women have a lineage of female symbols and a tradition of alternate discourse located in visual domestic crafts. I posit that Wilding's early intuitive use of visual domestic craft in feminist art had a profound influence on Chicago's development of the visual iconography that she utilizes in The Dinner Party and in subsequent projects.

After Womanhouse, Chicago and Schapiro pushed to refine their ideas on women and expression, focusing more on different ways of communicating rather than on trying to force women's works into the unsuitable definitions that dominant society had built for “success.” In 1973, they argued that, “[w]hen women began to speak about themselves, they were not understood. Men had established a code of regulations for the making and judging of art which derived from their sense of what was or was not significant. Women … could not occupy center stage unless they concerned themselves with the ideas men deemed appropriate. If they dealt with areas of experience in the female domain, men paid no attention… . [W]omen whose work was built on their own identity in terms of female iconography have been treated by men as if they were dealing with masculine experience. This is a false assumption since the cultural experience of women has differed greatly from that of men” (Chicago and Schapiro, “Female” 40).

Under the guidelines that Chicago and Schapiro outline above, any art—and therefore any rhetoric—that grows from the domestic sphere would necessarily be judged unworthy by the dominant masculinist faction of society. As Chicago and Shapiro state: “women have suffered when measured by male standards” (41). While their work with the Feminist Art Program attempted to influence women to work in the same ways as men, Chicago and Schapiro learned from their experiences and began to think of women's works as differently strong, or existing in ways that did not embrace established masculine assumptions and ideologies.

Chicago's own work from this time demonstrates her consideration of female symbols, but not her thinking about traditional methods of women's communication, such as visual domestic craft. Between 1972 and 1975, Chicago stated that she “attempted to reconcile [her] personal subject matter and style with a formalist visual language” (qtd. in Sackler 28). In 1972 and 1973, she worked on a series of paintings entitled Great Ladies. The muted-toned abstract images seem vaguely vulval, but that imagery is ambiguous and largely softened by an overwhelming association with flower petals or sunrays. While working on this series, Chicago admittedly felt that her desire to discuss art and feminism in her work might be too abstracted, and she began to reflect on how her work could act as a vehicle for her socio-political thoughts (Through 179).

In her autobiography Through the Flower, Chicago confesses that, in her haste to be treated in a manner equal to men, she had forced herself into another unrealistic stereotype and became an under-emotional “superwoman” (179–80). While she began freeing herself from this extremist position in the Great Ladies series by sharing her personal thoughts and feelings, making herself “transparent” to viewers, this series served as the first step on her path toward self-actualization through her work (). She writes of another painting from 1973, Let It All Hang Out, that she “cried for several hours” when she finished it, as “the painting was forceful and yet feminine. I had never seen those two attributes wedded together in an image. I felt ashamed—like there was something wrong with being feminine and powerful simultaneously. Yet I felt relieved to have finally expressed my power” (Through 181–82). As the aforementioned statements indicate, Chicago was beginning to feel differently strong in a distinctly female way.

FIGURE 3. Judy Chicago, Elizabeth, in Honor of Elizabeth from the Great Ladies series, collection of the artist in cooperation with the Through the Flower Foundation. Image reprinted by permission of the Through the Flower Foundation.

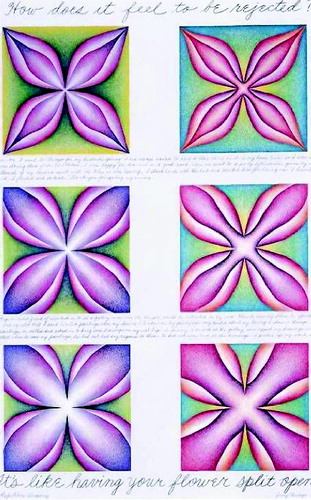

Her next series, the Female Rejection Drawings of 1974, clearly shows Chicago's progression from utilizing a highly abstracted flower image that could be read as vulval, to using a vulva that could be read as a flower or butterfly. This set of drawings punctuates the fact that she made dramatic leaps forward in terms of constructing female iconography centered on the vulva as an organic image that could be foundational to a women's lexicon (Chicago, Beyond 38–39). She explained that: “the vulval image could act as a visual symbol for the physically defining characteristic of woman in an almost metaphysical sense; that is, an entryway into an aesthetic exploration of what it has meant to be a woman—experientially, historically, and philosophically” (38–39). These Female Rejection Drawings chronicle Chicago's transformation from abstract, subdued symbolism to the creation and articulation of her ultimate female visual lexicon. Amelia Jones refers to these autobiographical images as materializing “her commitment to the notion of a centralized form as a means of reclaiming the female body from patriarchy in an empowering way” (95–96).

Chicago added written text to these pieces, addressing the simultaneous rejection of her artwork by gallery owners and the sexual harassment that she received from them. Female Rejection Drawing #1 (How Does It Feel to Be Rejected?) shows six pink and purple flowers with written text between each pair (). The first line of written text in this piece recalls a gallery opening for one of her husband Lloyd Hamrol's shows, at which the owner throws the loaded statement, “I haven't had you yet,” at Chicago. The gallery owner's sexual innuendo ruins her evening, as it shifted the focus from her as a person and an artist to her as a female body, and thus disempowered her (Sackler 38). The second line of writing in the piece refers to another male gallery owner, who declined to exhibit her work because it did not elicit an emotional response from him, with the implication that he felt it was too female (38).

FIGURE 4. Judy Chicago, Female Rejection Drawing #1 from the Female Rejection Drawings series, collection of the artist in cooperation with the Through the Flower Foundation. Image reprinted by permission of the Through the Flower Foundation.

In 1974, Chicago's husband also confessed to her that “he had engaged in a series of short affairs” throughout the entirety of their relationship (Chicago, Beyond 43). The majority of Hamrol's affairs were with female students at the various schools where he taught. Chicago wrote that she found it “painful and humiliating to discuss this, primarily because his words hurt so much, especially his revelation that a number of these liaisons had gone on at the very time that I had been teaching young women. While I had been listening to their bitter complaints about how their male art professors seemed to be more interested in seducing than educating them, my own husband had been involved in such behavior. This realization absolutely horrified me because in addition to feeling betrayed, it made me seem like a total hypocrite” (Chicago, Beyond 43).

Significantly, Chicago and her husband “did not seek marital counseling … or … try to talk things out” (43). She states that they just glossed over the problems and attempted to go on. The marriage took several years to dissolve, and this slow unraveling took place over the years of The Dinner Party's design and the first years of the piece's construction (Levin 197–295). As I argue below, there is a direct correlation between Chicago's unwillingness or inability to verbalize her feelings and her development of an alternate visual language that charted her narrative of the self.

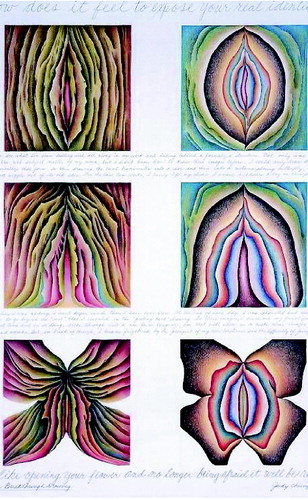

Female Rejection Drawing #5 (How Does It Feel to Expose Your Real Identity?) shows six vulvas unfolding like flower petals or butterfly wings (). These drawings rely much more on earth and flesh tones than the earlier ones, and are much more recognizable as vulvas. Written text also accompanies each set of these drawings. In the written part of this piece, Chicago admits that “these images are what I've been dealing with all along in my work and hiding behind a formalized structure” (qtd. in Sackler 41). Chicago is rejecting the “formalized” or masculinized structure of the dominant discourse and what is acceptable under those constraints, while at the same time coming to terms with her own nature and the external rejection of herself based on her sexual being.

FIGURE 5. Judy Chicago, Female Rejection Drawing #6 from the Female Rejection Drawings series, collection of the artist in cooperation with the Through the Flower Foundation. Image reprinted by permission of the Through the Flower Foundation.

Chicago discusses the Female Rejection Drawings, which were completed during the fallout from Hamrol's admission of frequent infidelity, as “the basis for a series of images, which … were intended to represent various goddesses or mythological figures and historical personages” (Beyond 45). Chicago's sexual self was used and rejected, in that she entered into what she thought was a monogamous relationship with Hamrol, but he had sex with many other women during their marriage—a clear statement that Chicago was not enough for him sexually and that sex was more important than their bonds of fidelity. Hamrol exercised his culturally supported right to sexual freedom in an act that disempowered Chicago on the basis of her differing genitalia because, as a woman, she was not acculturated to the same sexual freedom that her partner had. Chicago's passivity—a result of sexual restrictions supported by societal biases against women—led her eventually to name and explore these issues in and through visual discourse. As Chicago developed a “female visual idiom” in the Female Rejection Drawings, she questioned her husband's and the art world's simultaneous rejections. These vulval images represent her scrutiny of the female body in her search for a justification for her rejection. She examines the woman's body—her body—seeking an explanation for why difference means inferiority.

The Dinner Party

If the Female Rejection Drawings are Chicago's autobiographical exploration of her own womanhood and her subsequent questioning of her worth as a woman, then The Dinner Party stands as her ultimate celebration of her body and of the woman's body in general. This celebration of the female body in The Dinner Party represents Chicago's celebration both for and of herself, the community of over four hundred volunteers who assisted in its construction, and the millions of people who have viewed and continue to view this work of socio-political feminist art.

The Dinner Party is deemed to be an installation piece rather than a sculpture because of the way in which the work occupies the room and the way in which viewers relate to the room itself as an important component of the piece. The triangular-shaped table measures forty-six-and-a-half feet long on each of its three sides, and each side consists of a place setting for thirteen historically important women, numbering twenty-nine in total. The names of an additional 999 historically important women are painted on the porcelain floor. Chicago and a team of volunteers chose the 1,028 women represented in the project for their influence on others in their communities and|or on future generations of women.

The place settings themselves comprise hand-painted two- and three-dimensional porcelain plates consisting primarily of abstracted vulvas combined with butterflies, the symbol that Chicago had been continually utilizing and refining to symbolize female liberation. Each of these twenty-nine plates is set on a handmade textile mat. Both the imagery and the techniques incorporated into each mat are intended to extend the story of the great woman discussed in the plate. Each of the fourteen-inch plates encapsulates Chicago's iconography as it relates to the historic woman she discusses. These plates are either two- or three-dimensional, based on Chicago's assessment as to whether the historic woman being discussed affected only those surrounding her or whether her influence extended to other generations. There are also six woven banners that welcome visitors to the installation.

The plate at the Susan B. Anthony place setting, for example, showcases a highly three-dimensional vulva-butterfly glazed in high-gloss shades of pink, which seems to be taking flight right off the table (). The runner at this place setting contains white satin “memory bands,” edged in black and embroidered with the names of prominent members of the suffragette movement, which are designed to recall the sashes worn by suffragettes (Chicago, Embroidering 228). The embroidered names of other leaders of the suffragette movement reinforce the idea that women's works are communal and that the identity of the individual is inextricably linked to that of the community. The slogan on the back of the runner reads “Independence Is Achieved by Unity” (Chicago, The Dinner Party: From 204), further reinforcing the idea of success only being attained through communal efforts.

FIGURE 6. Judy Chicago, close up of the “Susan B. Anthony Place Setting” from The Dinner Party instillation, collection of the artist in cooperation with the Through the Flower Foundation. Image reprinted by permission of the Through the Flower Foundation.

Anthony's runner also boasts a crazy quilt,Footnote2 stitched with designs taken from popular Victorian patterns, and a red fringed triangle where the “memory bands” meet, which was designed to resemble Anthony's famous red silk shawl, the only personal possession that this women's rights leader allowed herself (228). The incorporation of these tactile references to its subjects, such as Anthony's shawl (Chicago, Embroidering), solidifies the position of The Dinner Party as operating on one level as a collection of biographical texts, under Sidonie Smith and Julia Watson's call to examine self-referential visuals as sites of life narrative (Interfaces 5). This runner also has buttons pinned on it reading “Failure Is Impossible” (Chicago, Embroidering 230), referring simultaneously to the suffragette movement, second-wave feminism, Judy Chicago, and the fate of The Dinner Party and that of its many volunteer workers. The shawl becomes a demarcation of the self, but one that is situated amongst other signifiers of the group (i.e. the crazy quilt, the multiple pins, the unity slogan, the table itself with its many place settings, etc.), thus solidifying the message that, in feminist communities, the self is interwoven into the group and can only profit if unified with the other members of its community.

In addition to continuing the practice of a collaborative production of art that she began at the Feminist Art Program by working with over four hundred volunteers on The Dinner Party, Chicago built on her two previous series and Wilding's work in Crocheted Environment by exploring how space and place relate to identity, and what traditionally female materials and methods could be utilized in art-making to extend the female metaphor. She also more fully explored what she refers to as “a female visual idiom,” and it is important to restate that Chicago believes that “the vulval image could act as a visual symbol for the physically defining characteristic of woman in an almost metaphysical sense; that is, an entryway into an aesthetic exploration of what it has meant to be a woman—experientially, historically, and philosophically” (Beyond 38–39). In The Dinner Party, Chicago has also incorporated ideas on material and method from Wilding's work, utilizing ceramics and china painting, as well as textiles and a wide variety of needlework techniques. The use of traditionally female domestic craft in this piece advances women's issues through the notion that message and form can be welded productively to serve and advance the socio-political ideologies of feminisms. This incorporation of domestic craft into a feminist artwork also creates a safe space to discuss difficult issues by presenting the socio-political text within the context of the seemingly non-threatening domestic sphere.

Robin Patric Clair argues that women or other members of marginalized communities who have traditionally been silenced in public discourse may respond by voicing themselves through silence (165–86). For Clair, an act that is outside of or undermines the dominant discourse may be referred to as silent resistance, no matter how “loud” the actual act of resistance is. Clair further suggests that feminist forms of silent resistance are both representative of resistance and acts of resistance themselves (171). Applying this theory of silence and a rhetoric of resistance to The Dinner Party allows readers of the text to discern that Chicago both discusses the act of silencing in a representative form and, by developing her own visual idiom while disrupting the rules of acceptable themes, materials, and forms in art, constructs a site of resistance to dominant masculine discourse in The Dinner Party. In Johanna Demetrakas's documentary on The Dinner Party, one of the volunteers explains that the community members working on the project are not simply creating a text about feminism, but, more importantly, creating a feminist way of constructing texts (Right Out).

The Dinner Party is a complex piece, in which the artist constructs layers of meaning. On a most basic level, it can be read as one type of autobiography, in the form of the personal narrative of a woman faced with continual rejection from men because she is physically female. Since her artwork was rejected because she was a woman, her artwork becomes a symbol for this same woman. Likewise, given that her husband rejected her sexual self in favor of a string of mistresses, she explores the sexuality of women in this piece. Chicago uses her original visual language in The Dinner Party to express what she cannot verbalize. In reference to the time she spent developing it, she wrote, “what was to be a calm and quiet work period turned into emotional scenes and arguments as my marriage began to disintegrate. Distraught, I forced myself to work as I had so many times in the past, funneling my feelings into the forms that were developing with the strokes of my colored pencils” (Embroidering 8).

One message of The Dinner Party is that the female sex is glorious, but on women's own terms, not when it is misused or misunderstood through the lens of masculinity. The vulvas served up in this work are fourteen inches across and brightly colored. They are attractive and engaging, ready to take flight. Chicago intended her vulva-butterfly images to symbolize liberation, and the actual three-dimensional plates, as well as the three-dimensional quality of the flat plates, suggest just that: a celebration of the female. The plates themselves become a three-dimensional woman|women's life narrative, expressing Chicago's desires for liberation and the desires of other women for a similar freedom.

With this imagery and the two series that led up to The Dinner Party, Chicago shifted from trying to express women's ideas through a masculinist construction of what art and communication should be and moved to a radically new, deeper understanding and appreciation of certain conventionally female forms of communication, as well as to a recognition of the power these forms hold. No longer is her adulation of women's bodies hidden under layers of formalism or expressed through aggression; instead, they are visualized through traditional women's domestic crafts and with symbols unique to women's languages. In the journal that she kept during the construction of The Dinner Party, Chicago wrote that she wanted “to be myself now and get over being worried that it's not enough” (Chicago, The Dinner Party: A Symbol 22). These comments are a far cry from the overwhelming fear, which Chicago felt and explicitly expressed early in her career, that the men of the art world would see her as just a “dumb cunt” (Through 179). In retrospect, she stated that, “when I was young, I didn't want to be identified with other women. We learned early on that that is ‘identifying down.’ ‘Identifying up’ has been to identify with men” (qtd. in Gerstel). In Demetrakas's documentary, Chicago explains that there was a time when she would have been unable to appreciate visual domestic craft because of its connotation as women's work (Right Out). Her re-evaluation of domestic craft and its gradual incorporation into her artwork reflects her own growth as a person, an artist, and a feminist.

It is important to look at the streams that fed Chicago's understanding of her feminist language: the open expression of trauma based in gender as a way of understanding gender politics; the use of scriptotherapy to heal that trauma; and, most importantly, the rejection of the individual, masculinist autobiographical mode to create a collective, prophetic, didactic voice that can convey the value of women's art history, in particular, with authority. Art therapist Nancy Slater states that the creation of visual texts allows people to collect, name, express, and begin to understand and process the traumatic event or events they have survived (178). Practitioners of art therapy act in the belief that there are a number of patients who cannot be helped or who are not best helped through traditional means of therapy. In some instances, these same patients have repressed and|or denied traumatic memories or are unable to name and discuss their problems. The Dinner Party, understood through this theory, acts on a primary level as Chicago's attempt to understand the experiences she underwent when, in quick succession, she was rejected because of her gender by influential men in her life; it also represents her inability to verbalize her feelings about these events and these men. When denied voice through societally constructed power dynamics between husband and wife, gallery owner and artist, male and female, Chicago manages to empower herself successfully by speaking through a visual language that is highly in tune with her female self, demonstrating both her strength and the power of being differently strong as she cultivates a distinctly feminist aesthetic by melding fine art, domestic craft, and feminist theory and practice.

Suzette A. Henke's theories of scriptotherapy relate directly to written texts as an extension of Freud's talk therapies; Chicago's visual texts seem to fulfill the same purpose for her. This idea of scriptotherapy certainly applies to The Dinner Party. Chicago admits that she was unable to talk to Hamrol about his string of infidelities and that she was greatly upset by the sexually biased treatment she received from gallery owners, to which she felt that there was no recourse. In addition to these traumatic episodes of having individuals deny her sense of self and, subsequently, her sense of worth, through her work on the Feminist Art Program and Womanhouse she had come to realize that she was not participating in a female discours. Rather she was trying to force her way into the dominant discourse by acting masculine and therefore not having her own artistic vocabulary or access to a language of her own. Smith and Watson explain that, “speaking of writing about trauma becomes a process through which the narrator finds words to give voice to what was previously unspeakable … and that process can be, though it is not necessarily, cathartic” (22). The Dinner Party was certainly a cathartic text for Chicago.

The Dinner Party, however, does not solely function as Chicago's autobiographical narrative. Drawing on New England Puritan texts, G. Thomas Couser and Margo Culley have suggested that community life narratives are foundational texts in the US's autobiographical tradition. Couser argues that the US tradition of autobiography grew from a Puritan practice of conflating “personal and communal histories, conscious[ly] creat[ing] … exemplary patterns of behavior, and … didactic, even hortatory, impulses,” culminating in a “tendency to assume the role of prophet” (1). His “prophetic mode” of autobiography positions the autobiographer as speaking “for God to his community. But by virtue of this fact, he also functions as a representative of his community—as a reformer of its ethos, articulator of its highest ideals, interpreter of its history, an activist in the service of its best interests” (3).

Culley builds on this analysis of the “prophetic mode,” stating that the Puritan traditions of “reading the self” or sharing the belief of divine intervention in one's life were done “in the hope that one's life story [would] be useful to others and [would] strengthen the community” (10). This commitment to being “useful to others” is, according to Culley, what transforms an “individual autobiographical act [into] an act of community building” (10). On one level, then, The Dinner Party embodies this imperative to be “useful to others.” Chicago is a feminist pedagogue who wants “to teach women's history through art” (Beyond 45). In many respects, that desire to be the teacher embodies Couser's and Culley's model of speaking from the subject position of prophet.

The dramatic difference between the “prophetic mode” as defined by Couser and the autobiographical work presented in The Dinner Party may be located in Chicago's interest in communal art-making, an artistic practice that was developed and refined in her two years in the Feminist Art Program. More than four hundred volunteers worked on The Dinner Party and, in both of the books Chicago produced in conjunction with the installation—Embroidering Our Heritage: The Dinner Party Needlework and The Dinner Party: A Symbol of Our Heritage—she lauds the volunteers, without whose skills, efforts, and contributions the work would not have come into being. Hundreds of volunteers are named in these texts and several have their photographs included. Likewise, the volunteers and other craftspeople from whom Chicago learned essential domestic-craft techniques are an integral part of Demetrakas's documentary. They are interviewed as part of the narrative and are frequently shown participating in the project. Furthermore, Chicago often uses the term “we” when discussing aspects of the work in the documentary and even refers to the volunteers as her “partners” (Right Out).

Despite some criticism of the atelier-like studio, in many ways The Dinner Party was an authentically communal project, and a number of the people involved in its creation have continued to work with Chicago on additional projects.Footnote3 Edward Lucie-Smith points out that, “complaints about the way in which [the] studio was organized come from outside the organization [,] not from within it” (67). One volunteer, Ann Isolde, wrote that, “in the studio everyone had the opportunity to participate in the esthetic process and to take on more responsibility according to an increase in skill” (qtd. in Chicago, The Dinner Party: A Symbol 220).

This additional dimension of The Dinner Party not only illustrates how this text stands as multilayered, but also shows how Couser's delineation of the “prophetic mode” of US autobiography might fail to describe adequately the group of people who worked so diligently on the piece as part of the communal effort. As Smith and Watson explain:

the autobiographical is not a transparent practice. … “autobiography” is a term with a troubling history. … it has signified the many practices of self-representation but has come to be narrowly identified by many critics in the twentieth century with a particular mode of life storytelling, the retrospective narration of “great” public lives. This latter understanding of the term has often obscured the ways in which women, and other people not included in the category of “great men,” have inscribed themselves textually, visually, or performatively. (8)

Following Smith and Watson's stated concerns over women and other members of marginalized communities not defining their lives as of “great men” and therefore not deeming them worthy of being chronicled, Couser's idea of the “prophetic mode” in autobiography has difficulty stretching to explicate the lives of women in the US. This thought is best exemplified by his inclusion of the narrative of only one woman in his text—Gertrude Stein, who could be defined as living her life in accordance with a masculinized dominant discourse. A reinterpretation of this “prophetic mode” for application to second-wave feminist visual texts proves to be helpful here, for it productively disrupts the master and masculine narrative.

A more appropriate categorization for The Dinner Party, and texts produced in similarly collaborative ways, might be the “community narrative.” Such a term might better describe a text that speaks as an equal both internally to a group and externally on behalf of said group. Demonstrating of the second-wave feminist mantra that “the personal is political,” an internal community narrative would tell a personal story as a means of communicating a common theme to others who have shared comparable experiences. This sharing acts, first, as a personal therapeutic device (akin to scriptotherapy), and then as a means of comfort and support for others going through similar experiences, while finally opening a door to beneficial conversation and organization, such as socio-political women's movements.

The 1996 exhibition at the Armand Hammer Museum of Art and Cultural Center, Sexual Politics: Judy Chicago's Dinner Party in Feminist Art History, and the catalog of the same name support this understanding of how Chicago's visual language reverberated through the feminist art world and influenced (while being influenced by) feminist artists looking for voices of their own. The exhibition's curator and catalog editor, Amelia Jones, views The Dinner Party as a space to explore and reclaim women's sexuality (22), which has “informed the development of feminist art” (24). It further asserts that, when placed within the context of the body of feminist art produced in the US from the 1960s through the early 1980s, The Dinner Party is not essentialist, but rather one aspect of a conversation by and about women reclaiming the female form (24–25). This interpretation of The Dinner Party underpins a reading of the work as a community life narrative that speaks as a part of a group, both internally and externally. Jones further suggests that the work that Chicago and her contemporaries did with vulval imagery undermined taboos and therefore created opportunities for future generations of women artists to explore more honestly the ideas, issues, feelings, and topics most relevant to them (26–37), thus opening the door for more feminist visual life narratives.

In their definition of collaborative life writing, Smith and Watson include the “as-told-to narrative in which an informant tells an interviewer the story of his or her life;” “the ghostwritten narrative recorded, edited, and perhaps expanded by an interviewer;” and a “coproduced or collectively produced narrative in which individual speakers are not specified or in which one speaker is identified as representative of the group” (Reading 264–65). To some extent, there is certainly an overlap between this definition of collaborative life writing and what I refer to as community or communal autobiography, but I would suggest that there are some subtle differences between the two in terms of the clarification of power relations.

The participation by over four hundred volunteers in the crafting of The Dinner Party destabilizes the attestation that the community autobiographer stands outside the group, defining him- or herself as an individual in order to enlighten the group with his or her great achievements. The narrative of Chicago's exploration, betrayal, and acceptance elaborated herein both mirrors and speaks for or with the group who worked on the piece, and those who viewed it and found some reflection of the self within it. The Dinner Party, as an example of a second-wave feminist life narrative, illustrates one example of the autobiographer defining herself as a member of a community and creating the narrative in conjunction with other members of the group. For example, each person who participated in the craft of a textile runner embroidered his or her name on the piece (Chicago, Embroidering 17), demonstrating the communal, not individual, construction and story represented by the piece. Even the structure of the embroidery volunteers working together in the studio's loft to craft the runners mirrors a communal sensibility, in that they worked as women do at traditional quilting bees—an act akin to writing a communal diary. Chicago is certainly the focus of this work and does become a representative of the group, but her collaborators are not silenced or unnamed, thus suggesting that this work pushes the definition of “collaborative” more toward “communal.”

In her clarification of the term “autography,” Perreault explains that the “I” of a feminist text suggests the “we” of a feminist community (2). She looks “to writers whose feminism is embodied, historically precise, self-reflective, and communally shaped” (3), and states that “as women write themselves they write the movement” (8). Perreault's statements can be extended to visual life narratives as well. Therefore, the narrative of The Dinner Party also embodies shared experiences. While Chicago's personal narrative may be one of her dismissal by her husband and prominent gallery owners based on sex, to many participants in the community of people constructing The Dinner Party, this was a shared cultural experience. Another Dinner Party volunteer, Elaine Ireland, wrote,

the studio environment transformed for me all that women do while waiting. It transformed the stitchery, the sewing, the chit-chatting, the aloneness—the waiting for the end of that dreadful aloneness—into something more tangible, something that added meaning to it all. The studio magnified a thousandfold one individual woman's pain, her loneliness, her waiting, her guilt, her confusions, her invalidity, her invisibility. Coming to that studio opened my eyes to the rainbow array of women who have experienced similar impositions, similar slow dyings, women who are no longer satisfied, no longer willing to be so imposed upon. (qtd. in Chicago, The Dinner Party: 234)

The Dinner Party, therefore, may also be read as a three-dimensional history text that both tells the story of women throughout history in the biographical plates and runners and, through the collaborative narrative, tells the story of a group of second-wave feminists whose belief in the necessity of this project was so great that they volunteered their time and energies, as well as their own money for travel to the studio in Los Angeles and room and board while they were there. Washington Post reporter Rachel Beckman—who was born during the backlash of the Reagan years—asserted that The Dinner Party taught her about the 1970s and the birth of second-wave feminism. She wrote that when she first viewed The Dinner Party in 2007, she saw it as “a spread-eagle declaration of arrival.”

Perreault also suggests that feminist community life narratives are community-shaping as well as “communally shaped.” “[T]he feminist writer of self,” she adds, “engages in a (community of) discourse of which she is both product and producer. This interrelation of self and community is one of the most provocative issues in the writing of feminist subjectivity… . The feminist writing of self, then, is part of creating new communities” (7). The narrative of The Dinner Party thereby extends to the viewers of the piece. Because it is an installation piece, the way in which the viewer navigates the work is an important aspect of its argument. Viewers are not only being educated about women's history by this three-dimensional history book, but they are also reflecting on their role in the piece and as citizens with a voice in socio-political issues. Viewers circling this piece find place settings in honor of great women, but no one sitting at the table; the viewers then become the guests invited to the table, and their role is to find a seat, and thereby the woman's history, which is best suited to them.

Furthermore, this table acts as Chicago's invitation to the greater population to participate in a consciousness-raising event, mirroring the pedagogical ideology she developed in the Feminist Art Program. Chicago states that one integral aspect of The Dinner Party is encouraging viewers to rethink the roles of consumer and consumed (Right Out). The table becomes the circle (or triangle) in which to reflect on and share personal insights. As viewers are confronted with fourteen-inch vulva-butterflies, they are forced to contemplate woman-ness and reflect on their own feelings toward gender constructions, liberation of the self, and the languages that shape women's experiences, as well as feminism and the societal constructs that relegate women.

Dinner at Home

The Dinner Party first opened in 1979 at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Over five thousand people stood in line, waiting as long as five hours to view the piece (Chicago, The Dinner Party: From 27). Despite the clear interest of the viewing public, art critics called the piece simultaneously banal and pornographic. The other museums that were scheduled to exhibit it pulled out from the tour, and The Dinner Party went directly into storage. These decisions could have been the end for this work of art, but women who had seen the piece in San Francisco started a grass-roots organization to bring it out of storage and arranged an international tour at smaller venues. Chicago wrote in 1980 that she felt “that unless The Dinner Party is permanently housed I will not have achieved my goal of introducing women's heritage into the culture so that it can never be erased again” (Embroidering 21).

In 1990, the University of the District of Columbia was prepared to receive the work as a donation. Chicago stated that she envisioned The Dinner Party “as something for U. D. C. [University of the District of Columbia] to build on with other art that is marginalized or excluded from other institutions” (qtd. in Gamarekian). According to the then-chair of the university's board of directors, Nira Hardon Long, this gift was meant to “serve as the beginning of the university as a multi-cultural center for the expression of creative ideas dealing with human dignity, freedom and equality” (qtd. in Gamarekian). “When asked if the board had any hesitations about accepting ‘The Dinner Table’ [sic] because of its sexual content, Ms. Long said the matter never came up for discussion” (qtd. in Gamarekian). In a fight that ultimately ended up in the US House of Representatives, this plan for “the expression of creative ideas” was canceled, largely due to the “unsuitable” nature of the piece, and The Dinner Party went back into storage (Chicago, Beyond 228). According to the Washington Post: “California Republican Dana Rohrabacher called it ‘a spectacle of weird art, weird sexual art at that’” (qtd. in Beckman).

In 1996, Jones and the Armand Hammer Museum of Art and Cultural Center on the campus of the University of California at Los Angeles mounted their exhibition Sexual Politics: Judy Chicago's Dinner Party in Feminist Art History. Although over fifty-five thousand viewers visited the exhibition (high numbers for a university museum), critics labeled The Dinner Party a “failed” work and dismissed the exhibition as a whole based on that criticism, rather than the obvious public interest in viewing the piece (Chicago, The Dinner Party: From 284). Again, The Dinner Party went back into storage.Footnote4 Finally, in 2002, noted art collector Elizabeth Sackler purchased the work for a purported $2.2 million, and The Dinner Party permanently came out of storage. In partnership with the Brooklyn Museum of Art, she donated the funds to renovate a storage facility into the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. In 2007, the center opened with The Dinner Party on display, inciting the Art News comment about 2007 being “the year of institutional consciousness-raising” (Hoban 108). Chicago's ultimate wish is “that The Dinner Party will act as a model because of its story” (qtd. in O'Neill-Butler 41)—a story that is an appropriate multimodal narrative for the second-wave feminist movement in the US. The installation piece's cyclical rejection and acceptance mirrors the rise of and backlash against second-wave feminism. While it remains troubling that no existing facility would house The Dinner Party and a separate facility needed to be created for it, the fact that it is permanently housed and that a woman had the resources to create the space for it speaks to the progress that US women have made, at the very least in that they have the disposable, discretionary income to purchase such a work of art and the power to have it housed.

This ultimately fulfilling conclusion for The Dinner Party is, however, a milestone for the second-wave feminist movement, as it demonstrates that the female imagery and themes of feminist reclamation that were perceived as too graphic in 1979 have begun to win acceptance—and even praise—from established institutions. Marsha Meskimmon notes that, prior to 1968, many women artists were not consciously discussing feminism in their work, but, after the radicalism of 1968, “many women artists … frequently engaged with feminist theory and politics in a highly self-conscious way” (12). Smith echoes this assertion by stating that all “texts by women participate in self-consciously political acts” (189). In light of these theories about the self-conscious socio-political acts of women making texts, The Dinner Party must then be read as asking viewers to reflect on second-wave feminism. Jones argues that “the charged reception of The Dinner Party has much to teach us about the complexities of feminist and contemporary art history” (86).

The Dinner Party stands ultimately at the unique crossroads of a record of the second-wave feminist movement, a three-dimensional women's history text, a physical space of consciousness-raising for the community of volunteers and visitors to the work, and as narratives of Judy Chicago's personal life, her community of feminist socio-political thinking, and the political activism that is unable to be separated from such thinking. Chicago, despite an initial desire to be viewed as just one of the guys in the male-dominated art world, grew through her experiences at the Feminist Art Program to build a woman's visual language, one ripe with symbols and dependent on women's traditional domestic crafts as a rich, symbolic language. Her multimodal personal narrative of growth as a feminist and human being becomes both an internal and external community life narrative that simultaneously reflects the rise of, backlash against, and contemporary conditional acceptance of the feminist socio-political movement in the US.

Acknowledgments

I presented portions of this essay at the 2008 International Auto|Biography Association conference on Life Writing and Translations at the University of Hawaii at Manoa under the title “Women with Needles: Second-Wave Feminism and the Fiber Arts of Sociopolitical Autobiographies.” I am appreciative of the feedback that I received in that forum. I am indebted to Rebecca and Joseph Hogan for initially accepting this essay for a|b: Auto|Biography Studies in 2009, and to Paul Arthur for suggesting that it might be a useful addition to this special issue. Cynthia Huff and Eric D. Lamore also took significant time to engage with my drafts and provide notes, for which I am also grateful. I am especially thankful to Judy Chicago, Susannah Rodee, and the Through the Flower Foundation for their support and permission to reprint the images used in this essay.

Notes

1. It is important to note that Judy Chicago disagrees with readings of The Dinner Party that reduce this complicated text into simply an autobiographical narrative. She wrote that, while “there is nothing wrong with doing autobiographies on plates, it is a mistake to claim that such a project has anything to do with The Dinner Party, which is about women's achievements in history” (“Introduction”)—a sentiment echoed from the introduction to the film Right Out of History: The Making of Judy Chicago's “Dinner Party.” Despite Chicago's declaration to the contrary, reading The Dinner Party as a personal life narrative in conjunction with the community- and political-narratives found in the text productively complicates this work of art and furthers its role as a three-dimensional site for learning about the history of women. This reading mirrors other statements that Chicago has made regarding both feminist mantras of the personal as political and her quest for pertinent and personal content in her works of art. For a more complete description of the high school art curriculum that caused Chicago to comment on “autobiographies on plates,” see Chrzanowski (1).

2. Crazy quilting was a style of quilt-making popular in the Victorian era that utilized scraps of luxury fabrics, such as silks or velvets, joined together and decorated with fancy stitches. Since the maker typically did not follow a formalized quilt pattern per se, the end result was referred to as “crazy” for its informal and often exuberant design.

3. Additionally, the endpapers of Chicago's extensive 2007 book, The Dinner Party: From Creation to Preservation, lists the names of several of the volunteers who worked on the project and many of the people who worked so hard to keep the piece in circulation and eventually find it a permanent home. Also, the website of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art lists the names of 424 volunteers who worked on The Dinner Party and shows an image of the “Acknowledgement Panels” that are kept in storage at the center (“Elizabeth”).

4. It is important to note that while The Dinner Party itself spent a good deal of time languishing in storage between 1979 and 2007, there was still continual interest in the piece: the primary photograph of the work () was shown as a slide in art history classes and made appearances in art history and feminist publications. It is also significant, however, that the most widely distributed image of The Dinner Party was not often printed in color and was taken from quite a distance away from the work in order to get all thirty-nine place settings into the picture. This coverage decision diminishes the quality and impact of the work, as most reproductions tend to fail to convey the grandeur of a work of art to viewers, and also minimizes the detail of the place settings themselves, to the extent that they have no real impact on viewers.

Works Cited

- Beckman, Rachel. “Her Table is Ready.” Washington Post 22 Apr. 2007: N06. Print.

- Chicago, Judy. Beyond the Flower: The Autobiography of a Feminist Artist. New York: Viking, 1996. Print.

- —. The Dinner Party: A Symbol of Our Heritage. New York: Anchor, 1979. Print.

- —. The Dinner Party: From Creation to Preservation. London: Merrell, 2007. Print.

- —. Embroidering Our Heritage: The Dinner Party Needlework. New York: Anchor, 1980. Print.

- —. “Introduction by Judy Chicago to The Dinner Party Curriculum Project.” Through the Flower. Through the Flower, n.d. Web. 5 Aug. 2009.

- —. Through the Flower: My Struggle as a Woman Artist. New York: Penguin, 1975. Print.

- Chicago, Judy, and Miriam Schapiro. “Female Imagery.” The Feminism and Visual Culture Reader. Ed. Amelia Jones. London: Routledge, 2003. 40–43. Print.

- —. Womanhouse Exhibition Catalog. Valencia: California Inst. of the Arts, 1971. Print.

- Chrzanowski, Rose-Ann C. “A Dinner Party of Their Own: Tribute to Judy Chicago.” Arts and Activities Magazine. Arts and Activities Magazine, Feb. 2006. Web. 5 Aug. 2009.

- Clair, Robin Patric. Organizing Silence: A World of Possibilities. Albany: State U of New York P, 1998. Print.

- Couser, G. Thomas. American Autobiography: The Prophetic Mode. Amherst: U of Massachusetts P, 1979. Print.

- Culley, Margo, ed. American Women's Autobiography: Fea(s)ts of Memory. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1992. Print.

- “Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art: The Dinner Party: Acknowledgement Panels.” Brooklyn Museum. Brooklyn Museum, n.d. Web. 4 Aug. 2011.

- Gamarekian, Barbara. “A Feminist Artwork for University Library.” New York Times 21 July 1990: 14. Print.

- Gerstel, Judy. “Feminist Artist Reflects on Controversial Piece.” Toronto Star 7 Sept. 2007: L02. Print.

- Henke, Suzette A. Shattered Subjects: Trauma and Testimony in Women's Life-Writing. New York: St. Martin's, 1998. Print.

- Hoban, Phoebe. “We’re Finally Infiltrating.” Art News Feb. 2007: 108–13. Print.

- Jones, Amelia. Sexual Politics: Judy Chicago's Dinner Party in Feminist Art History. Berkeley: U of California P, 1996. Print.

- Levin, Gail. Becoming Judy Chicago: A Biography of the Artist. New York: Harmony, 2007. Print.

- Lippard, Lucy R. From the Center: Feminist Essays on Women's Art. New York: Dutton, 1976. Print.

- Lucie-Smith, Edward. Judy Chicago: An American Vision. New York: Watson-Guptill, 2000. Print.

- Mainardi, Pat. “A Feminist Sensibility?” Robinson 295–96.

- Meskimmon, Marsha. The Art of Reflection: Women Artists’ Self-Portraiture in the Twentieth Century. New York: Columbia UP, 1996. Print.

- O’Neill-Butler, Lauren. “Party Line: 30 Years Later, Judy Chicago's Dinner Party Has Enough to Go Around.” Bitch 35 (2007): 36–41. Print.

- Perreault, Jeanne. Writing Selves: Contemporary Feminist Autography. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1995. Print.

- Right Out of History: The Making of Judy Chicago's “Dinner Party.” Dir. Johanna Demetrakas. Phoenix Learning Group, 1980. Film.

- Robinson, Hillary, ed. Feminism-Art-Theory: An Anthology, 1968–2000. Oxford: Blackwell, 2001. Print.

- Sackler, Elizabeth A., ed. Judy Chicago. New York: Watson-Guptill, 2002. Print.

- Schapiro, Miriam. “The Education of Women as Artists: Project Womanhouse.” Feminist Collage: Educating Women in the Visual Arts. Ed. Judy Loeb. New York: Teachers College, 1979. 247–53. Print.

- Slater, Nancy. “Re-Visions on Group Art Therapy with Women Who Have Experienced Domestic and Sexual Violence.” Gender Issues in Art Therapy. Ed. Susan Hogan. London: Kingsley, 2003. 173–84. Print.

- Smith, Sidonie. “Autobiographical Manifesto: Identities, Temporalities, Politics.” Prose Studies 14.2 (1991): 186–212. Print.

- Smith, Sidonie, and Julia Watson, eds. Interfaces: Women|Autobiography|Image|Performance. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2002. Print.

- —. Reading Autobiography: A Guide for Interpreting Life Narratives. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2001. Print.

- Stein, Judith. “For a Truly Feminist Art.” Robinson 297.

- Steinem, Gloria. Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions. New York: Holt, 1983. Print.

- Wilding, Faith. “Crocheted Environment.” Chicago and Schapiro, Womanhouse 11.

- —. “The Feminist Art Programs at Fresno and Calarts, 1970–75.” The Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s, History and Impact. Ed. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard. New York: Abrams, 1996. 32–47. Print.