Abstract

This article explores the role of photography in memoirs published in the 1950s about teaching Native American children in the early 1900s. The photography underscores the paradox of Indian education for the authors, whose job it was to erase the cultures in the classroom that they were dedicated to preserving on the page.

Between 1951 and 1957, five American women published strikingly similar memoirs about their experiences teaching at Native American boarding and day schools between the turn of the century and World War I.Footnote1 These texts are Minnie Braithwaite Jenkins' Girl from Williamsburg (1951), Estelle Aubrey Brown’s Stubborn Fool: A Narrative (1952), Flora Gregg Iliff’s People of the Blue Water: My Adventures among the Walapai and Havasupai Indians (1954), Gertrude Golden’s Red Moon Called Me: Memoirs of a Schoolteacher in the Government Indian Service (1954), and Mary Ellicott Arnold and Mabel Reed’s In the Land of the Grasshopper Song: Two Women in the Klamath River Indian Country in 1908–09 (1957). While each of these memoirs speaks to the singular experience of its author(s) and contains certain unique elements, in many ways these authors are essentially telling the same story: feeling stifled, frustrated, or bored by their upbringing on the East Coast and seeing their opportunities limited by their gendered identities, they embarked on journeys west, seeking adventure and fulfillment teaching Native American children. In addition to some similarities in plot and narrative, each of the books also contains photographs that depict the landscapes of the West, posed portraits of Native Americans in both Western and native dress, still lives of artifacts, candid scenes of reservation life, and|or touristy shots of the teacher herself.

Whether framed as a kind of family album situated in a cluster in the middle of the book or interspersed throughout the pages, the photographs included in these texts, along with their placement and captions, visually encapsulate the tensions, paradoxes, and contradictions of both these writers’ individual experiences and the education of Native Americans in the early twentieth century. Their often unknown or assumed provenance complicates the writer–reader transaction and exposes the constructed nature of photography in autobiography, where, as many scholars have noted, things are often not what they seem.Footnote2 Rather than simply illustrating the narrative, the photographs add another layer to these autobiographies, at times supporting and at other times undermining the already complex political messages and ideologies about Indians circulating in the written text. Both the texts and the photographs evince a tension between the teachers’ impulses toward ethnographic salvage and their mandate—in the words of Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the first federally funded off-reservation boarding school and one of the progenitors of the boarding school movement—to “kill the Indian, save the man.” The photography included in these narratives visually underscores the paradox of Indian education for these white women, whose job it was to erase the cultures in the classroom that they were dedicated to preserving on the page.

These authors were on the front line of a new US policy toward Native Americans, which was adopted in the late 1800s and remained popular through the 1920s. According to noted historian David Wallace Adams, “the war against savagism [was] waged” in a new way, as “an ideological and psychological” assault against Indian children (27). By the end of the 1880s, the Bureau of Indian Affairs operated federal Indian schools on every reservation in the country (Hoxie 70). Justified by pseudoscientific evolutionary principles and informed by bureaucratic decision-making instead of Native American preferences for education, the system wrenched children away from their homes and families, and by and large relocated them to neglectful or abusive situations in poorly run schools. This policy contributed to the weakening of community bonds in indigenous communities and created a generation of children who often did not feel like they fit into white or Indian society. While some former students were grateful for the opportunities afforded by the Bureau of Indian Affairs' education, the system is generally considered to have been corrupt, racist, and oppressive. In short, teachers were agents of the government and meant to transform their charges into Americans; the goal of Indian education was to train children for citizenship and work, convert them to Christianity, instill the value of private property, and eradicate native languages in favor of English (D. Adams 21–24).

Since most of these authors joined the Bureau of Indian Affairs at least in part because of their fascination with native cultures, they were immediately faced with a contradiction between their job description and their desire to learn more about these cultures. Although none of these authors were trained anthropologists, they were teaching during the early twentieth century, when anthropology was being institutionalized in universities and colleges; during this period, “professional anthropologists attempted to popularize their young academic field by using the enormous appeal of Indian subjects in popular visual culture” (Griffiths 92). It comes as no surprise, then, that the memoirists would document their experiences with visual artifacts and lots of ethnographic description and information. The inclusion of anthropological details and images was likely one of the books' main selling points when they were published in the 1950s, a time when white Americans were obsessed with Indians. The mid-century American fascination with Native Americans was evinced by a return to “the Indian play,” which was popular at the turn of the century in organizations like the Boy Scouts and the Campfire Girls (Deloria 153). The American Indian Hobbyist periodical was founded in 1954, and white Americans made pilgrimages to powwows and reservations, costumed themselves in “Indian dress,” and held monthly meetings (Deloria 7, 137). Most importantly, the proliferation of television westerns in the mid- to late-1950s meant that Americans could conceivably watch a western every night of the week from the privacy of their own homes.

However, the photographs in these narratives are, of course, different from television and film images of Indians that Americans in the 1950s were used to seeing, since they are ostensibly true to life, given their placement within the autobiographies. These authors derive expertise from the authenticity of their direct experience, an authenticity that is supported by the inclusion of photographs. Likewise, the photographs mean more because they are placed within the genre of nonfiction. Even scholars whose studies center on the complexity of photographic and autobiographic representation acknowledge the power of photographic representation for average viewers and readers; Linda Haverty Rugg describes “a sense of photographic honesty [that] is grounded in the immediacy of photographic representation” (12), and Timothy Dow Adams refers to the “commonsense view” that photography serves as either illustration or verification, even though he invests it with a more complex role (xxi).

While the actuality of autobiography’s supposedly direct access has been explored, and in some senses exploded, by scholars since the beginning of autobiography theory, the fact remains that the transaction between readers and writers of autobiography is based on the reader’s trust that s|he is getting access to what the writer experienced.Footnote3 If the various recent hoaxes and controversies over memoir have illustrated anything, it is that contemporary audiences are quite invested in the promise of authentic or truthful representation inherent in Philippe Lejeune’s concept of the autobiographical pact, which describes autobiography as a contractual genre in which the author promises to tell the truth.Footnote4 No matter how many scholars or critics remind us of the subjective and inconsistent nature of memory or the constructed nature of both “fiction” and “nonfiction,” readers expect that memoirs recount what really happened.Footnote5 Of course, this investment in authenticity is not solely a contemporary trend; readers in the 1950s would have been just as likely to expect authenticity from autobiographers.Footnote6 Flora Gregg Iliff acknowledges as much by including a pre-textual “explanation,” in which she describes her writing process, beginning with her admittance that “it would be folly for me to pretend that I remember, for all these years, each date, name, and conversation recorded in this book,” and telling the reader that she used her vast archive of letters and more recent conversations with colleagues to flesh out her recollections. Thus, it is important to Iliff that readers recognize her story as authentic and true, even more so than it would be if just based on memory. Memoirs’ nonfictional characterization means that they can be invoked as political evidence and serve a testimonial function, which these memoirs certainly do. They stand as a testament to the authors’ views of the boarding school project, which was a central component of federal Indian policy.

Because these texts can be generically categorized as autobiographies with a great deal of ethnographic and anthropological context, they highlight both the relationship between anthropology and autobiography, and the constructed nature of both types of project. Like autobiography theorists, postmodern anthropologists have acknowledged the way in which anthropological accounts, especially narratives of fieldwork, are filtered through the anthropologist’s lens and thus are not an exact science.Footnote7 Both autobiography and ethnography have a “commitment to the actual” (Fischer 198) and “appeal to experiential authority” (Clifford 35); readers of both genres grant the author expertise based on this experience and expect accurate information. Clifford Geertz, one of the most influential postmodern anthropologists, claims that “ethnographers need to convince us… that had we been there we should have seen what they saw, felt what they felt, concluded what they concluded” (Works 16; emphasis added), and so too do autobiographers. Photography facilitates that connection between readers and writers because it makes it feel like the reader is, indeed, seeing what the writer saw. However, as these texts illustrate, that feeling, like some of the photographs themselves, is often staged. Ostensibly, the photographs included in these memoirs are from the authors' personal collections and often taken by the author herself; Iliff (136) and Arnold and Reed (88) make mention of their cameras in the body of the texts. Iliff is the only memoirist to indicate copyright on some of the photographs in her book, but the history of those photographs raises some significant questions about the uses of photography in these texts more generally.Footnote8

To different extents, all of the authors are motivated to share their ethnographic knowledge, and to teach their readers about the cultures that they have experienced, in part through the insertion of photographs and corresponding captions. The editors of Trading Gazes, a study of Euro-American photographers from 1880–1940, identify two categories of photographs of Indians: documentary photography, which records vanishing “savage” Indians for anthropological study, and aesthetic sentimental photography, which identifies “civilized” Indians as ready for assimilation (Bernardin et al. 7). The juxtaposition of both these types of images in each memoir exemplifies the central paradox of these texts. The authors engage in “salvage ethnography” to record a vanishing race, while they simultaneously acknowledge that Indians continue to exist and are capable of assimilation (Griffiths 84; see also Carr 155). This paradox, which is central to the stories these women tell, is even more evident in the pictures they choose to include.

Since the very beginning of photography in the mid-nineteenth century, Native Americans have been “favored subjects” (Bernardin et al. 4). Native American representation by white tourists emerges in Susan Sontag’s foundational text On Photography as the primary example of the “predatory” potential of photography—what she calls “colonization through photography” (64). Other scholars—most notably Gerald Vizenor—have expanded on Sontag’s condemnation of tourist photography as an invasion of privacy and disrespectful theft of culture. He does so by including formal portraits of Native Americans commissioned by the government, photographs taken by ethnographers, and, most relevant to this study, “before” and “after” images of children in boarding schools, pictures that were used to both justify and fundraise for the assimilation project.Footnote9 Although Vizenor finds “an elusive native presence” in many of these photographs (155), he argues that “photographs are cultural commodities and class representations that reduce a sense of native presence to an aesthetic silence and dominance” (154).Footnote10 More recently, scholars and curators have explored these issues of representation in the context of repatriation controversies and the ethics of the display of photographs that may have been taken without permission (Alison; Bernardin et al.; Katakis). These critics often see the photographic record as both problematic and potentially productive in terms of advocacy for Native American subjects, informing the contemporary audience about the history of native-white relations and exploring the freedom that white women accrued through the availability of work with and access to native cultures (Bernardin et al. 15).Footnote11 For example, Bernardin et al. characterize the photographs they discuss as containing a “productive and fascinating ambivalence,” and urge contextualization of the images in the larger narrative of progress occurring in US politics and culture at the time (25).

The photographs included in the teachers’ memoirs engage many of the issues that have circulated in scholarship about photography and Native Americans, but situate them in the context of autobiography. In her study of photography and autobiography, Rugg asks: “who has final authority over images—the photographer or the photographed subject?” (3). This question has also been central to discussions of imagery of Native Americans in photography, and who has the right to display these images. When considering the use of imagery in these memoirs, though, the authors are sometimes neither the photographer nor the photographed subject, but rather a third party: the teller of the story who is using the photography by and of others to illustrate her life narrative. Autobiographers use others all the time to tell their stories; as G. Thomas Couser notes, “it is now a critical commonplace that all autobiography is necessarily heterobiography as well because one can rarely if ever represent one’s self without representing others” (Vulnerable Subjects x). However, Couser argues that some representations of others necessitate a more careful consideration, especially portrayals of “vulnerable subjects,” who he describes as “persons who are liable to exposure by someone with whom they are involved in an intimate or trust-based relationship but are unable to represent themselves in writing or to offer meaningful consent to their representation by someone else” (xii). Native Americans in these memoirs are certainly vulnerable subjects, and the authors’ inclusion of images of them, and their homes, their land, their work, and their families, raises significant ethical questions, especially because the politics of the memoirists do not always align with the politics of the subjects.Footnote12

Flora Gregg Iliff’s narrative, People of the Blue Water: My Adventures among the Walapai and Havasupai Indians, is a useful case study when looking at photography in these texts for a number of reasons. The text was the only one to have national exposure, because of its publishing house (Harper); the front flap bills it as “an intimate and human account of a vanishing America.…a unique story of personal adventure in a strange backwater of history.”Footnote13 It also exemplifies the ethnographic impulses of the books as a whole; as in the other texts, the photography is included mostly for its ethnographic content. Contemporary reviews acknowledged its ethnographic usefulness and underlined Iliff’s experiential authority. For example, one reviewer notes that “the ethnologist may obtain some valuable data from it” (E. T. Smith), another alludes to Iliff’s “solid background of factual accuracy” (Debo), and a third evokes a Havasupai puberty ritual as an example of Iliff’s “fascinating detail” (“Rev. of People”).Footnote14 In the same prefatory “explanation” that references her letters as source material, Iliff thanks anthropologists Leslie Spier and George Wharton James for making their materials available to her; she quotes from anthropologists' descriptions of the tribes with which she worked throughout the text (see, for example, 122–23, 193). James is also a character in the memoir, because Iliff accompanied him on an expedition to the bottom of Havasu Canyon in 1901, a trip that no white person had undertaken before (Iliff 134–37). Finally, Iliff’s choice of subject matter itself illustrates her investment in ethnography; although she worked with Native Americans for forty years, the narrative treats only the approximately four years (1900–04) when she worked at day and boarding schools with the “most primitive” (the Walapai and Havasupai of Arizona).

From the very beginning of the book, Iliff depicts the contradiction between her job to assimilate her native students and her passionate interest in native culture, especially that of the Havasupai tribe, acknowledging in the first chapter that she is “setting out to civilize Indians,” even as she knows that “the Indians’ side of the conflict was not told in history books” (6). Iliff, already teaching in the city schools of Oklahoma territory, is inspired to enter Indian service because she is captivated by a lecture at her teachers’ institute about the “land of mystery and enchantment” and the “intriguing, primitive culture” of the people who live there (3). Her explorations lead her to find what she expects to find, and she explicates many aspects of Havasupai and Walapai culture throughout her text, which recounts her experiences teaching at a day school for the Walapai, traveling into the canyon to serve as a temporary superintendent for the Havasupai, and then returning to teach at a new boarding school in Truxton, Arizona.

Each of the memoirists falls somewhere on a spectrum between wanting to preserve native culture and advocate for her students and their families against the intrusion of the US government, and supporting the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ assimilationist agenda.Footnote15 For the most part, Iliff is quite engaged with her students’ culture and traditions, and usually tolerant of them. She uses her first-hand observations of individual students and their families as a way to inform her reader about Walapai and Havasupai customs more generally. This description of mourning rituals illustrates Iliff’s ethnographic intention, as she not only provides a visual observation and emotional response to young Bela’s death and the responses of the community, but also contextualizes the ritual in religious belief: “That night from our cottage porch we looked across the low hill to the west at the reflection in the sky of the deep-red flames that consumed the neat house Grace and Boots had built for their home, the house in which their son had died. With it were burned many of their household possessions. The burning of these familiar things would help free their son’s wandering soul from earth ties. The family must move to a place unfamiliar to Bela, or he would seek and find them and hover near” (78).Footnote16

Later she acknowledges the potential intrusions of ethnography, explaining that the Havasupai “despised the white man’s curiosity, his prying into their sacred ceremonies,” and she empathizes with this reaction, admitting that, “I knew they felt as I would feel if someone should enter my church and crane his neck and gawk, not with the hope of spiritual enrichment, but rather to observe the reactions of congregation and ministry” (151).Footnote17 In this sense, Iliff embraces a culturally pluralistic view, in which the two religions are able to coexist acceptably. However, just pages later, Iliff is appalled by the actions of a devastated widow, who believes she is haunted by her husband’s ghost. This “encounter with a fear so deeply grounded in myth and superstition” makes Iliff re-examine her attitudes about Havasupai religion, and vow to “counteract” it through educating the next generation (174). Thus, the tolerance that Iliff evinces for the customs and beliefs of her students and their families is contingent on the situation and the actual belief. Fundamentally, like most of the other memoirists, Iliff is invested in her own success as a teacher and remains convinced throughout the book that the model of education she imparted “promised a brighter future for these people” (269), even as she mostly respects, and sometimes even envies, their culture, traditions, and beliefs.

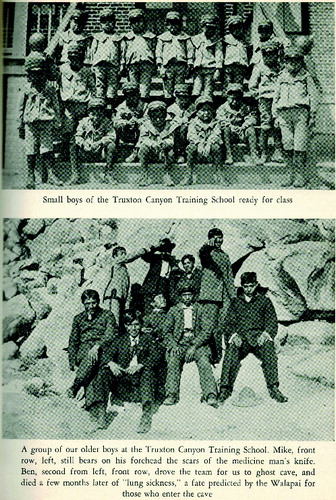

At times, Iliff makes the tension between her dual positions of teacher and amateur ethnographer explicit, as in a moment during her expedition to an undiscovered canyon when “my teacherish qualms as to sanitation prevailed over my explorer’s urge” (225). However, even more than her writing, her photographs and the accompanying captions exhibit her ambivalence about these, usually contradictory, roles. The section of twenty-two photographs, which are clustered together in the middle of the text, begins with a conventional school picture, indeed the representative image of the boarding school project: two lines of children, in militaristic uniform, arranged in front of a school building (, top image).

The bottom image in breaks from convention by showing schoolchildren in school dress but in a more naturalistic setting. The caption reads: “A group of our older boys at the Truxton Canyon Training School. Mike, front row, left, still bears on his forehead the scars of the medicine man’s knife. Ben, second from left, front row, drove the team for us to ghost cave, and died a few months later of ‘lung sickness,’ a fate predicted by the Walapai for those who enter the cave.” This caption is an anomaly because of its detail and specificity. In only three other instances does Iliff name the subjects of her photographs and provide direct links to the narrative by referencing events she has recounted in the text.

In the bottom caption, Iliff reiterates her discomfort with native medicine, which is a consistent theme in the book and an area in which her usually culturally pluralistic attitude breaks down. She admits in the text that her doubts about this strategy were undermined by its apparent success (Iliff 236)—a common observation in these narratives. Nevertheless, the caption continues by stressing the superstitions of the Walapai; since she herself had entered the ghost cave and emerged unscathed, her evocation of Walapai beliefs here is meant to undermine them. Iliff could have identified more, or different, students or not mentioned any of them by name. Instead, by highlighting Mike and Ben, two students with diametrically opposed experiences with Walapai medicine, Iliff begins the balancing act between cultural pluralism and assimilation that will characterize the rest of the photography section, and is evident in the photographs across the narratives.

In the following pages, Iliff constructs a museum in two dimensions, fully embracing the role of amateur ethnographer and evincing a desire to document the Walapai and Havasupai culture. One photograph—a landscape|still-life hybrid captioned “Mescal trimmed for the roasting pit. Stick is used to pry plant from the ground. Hatchet-like knife is used for trimming”—is credited to the American Museum of Natural History. In captions that guide the reader as they would in any museum exhibition, Iliff documents Havasupai cooking customs and vessels, various types of architecture, and even cave painting. These museum-like captions do not contain identifying information of the subjects; people are identified not by name, but rather by tribe—for example, “Havasupai children”—or relationship—for example, “mother.” Archival evidence suggests that, in at least one case, Iliff knew the names of the subjects of a photograph, but chose to provide a more general caption; the subjects of the photograph that she captions “Some Havasupai children have an uninhibited watermelon feast” are identified as “Chickpanagies' [sic] daughters enjoying a melon” on an identical, original print housed in the C. C. Pierce Collection of Photographs, c. 1840–1930 (photCL 2087).Footnote18 In the memoir, Iliff recounts visiting Chickapanyegi’s house, so it is likely she would have recognized these children as his daughters (111–13). Although this picture is included to illustrate her personal experiences with the tribe, her decision to generalize in the caption is in keeping with the ethnographic valence of the photography section. By unnaming them (or really, their father), Iliff renders these subjects visually present but textually absent, highlighting her role at the center of the autobiography, even as her experience and expertise are dependent on her relationship with them and many of the other unnamed members of the tribe pictured in the memoir. Evacuated both of their personal connection to Iliff and their specific relationship to time and place, the subjects of these photographs, like those in the other memoirs, are reduced to proxies for “typical” members of their tribe.Footnote19 This decision is representative of the damaging conglomeration of Native American tribes in the popular culture of both periods, and the perpetuation of stereotypical, decontextualized images of Native Americans circulating on postcards and in other venues throughout the early twentieth century (Preucel 21).Footnote20

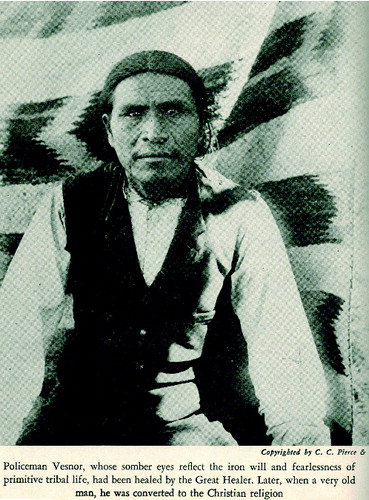

In addition to this type of generalization, contrasting the original captions with Iliff’s description of the images highlights her emphasis on the primitive. Seven of the photographs included in Iliff’s photography section (including the one in ) are credited to C. C. Pierce, a photographer and businessman who acquired a vast archive of images of Native Americans, the West and the Southwest over the first three decades of the twentieth century. He often bought photographs taken by regional photographers and eradicated the signature, stamping his own name on the back and copyrighting the images under his company (“Collection”). The majority of the photographs that Iliff attributes to Pierce appear to have been taken by George Wharton James, the ethnographer, photographer, and author whom Iliff quotes throughout the text and with whom Iliff traveled down Havasu Canyon. At least three of the photographs credited to Pierce were likely taken by James around 1898 or 1899; identical prints in the C. C. Pierce Collection at the Huntington Library are stamped with a copyright under James’s name and dated 1899.Footnote21 Iliff did not take these photographs, which the attribution to Pierce on the images makes clear. Perhaps more importantly, however, the pictures were taken at least a year or two before Iliff even arrived in Arizona, a fact that is not mentioned anywhere in the book. The substance of the photographs would have remained consistent—after all, it is just a year or two later—but the inclusion of these photographs, along with others credited to Pacific Stereopticon Co., undermines the direct access that autobiography is supposed to provide to the reader.Footnote22

Housed in the C. C. Pierce Collection, the original prints are labeled in a much more neutral valence than they are in Iliff’s text. For example, Pierce describes “Chickpanagies' [sic] daughters” as “enjoying” their food, while Iliff references “inhibition” and “feasting”—terms that have a much more stereotypical association with Native Americans. Likewise, the photograph that Iliff captions “Crude ladder by which Indians descended to the pool below Mooney Falls” (my emphasis) is described by Pierce simply as: “Havasupai Indian’s Ladder out of canyon on trail to Mooney Falls” (photCL 2127). Finally, Iliff captions the portrait of “Policeman Vesnor” (), which Pierce simply identifies as “Vesna [sic], a prominent man in the tribe” (photCL 2126), using the vocabulary of the primitive. She writes: “Policeman Vesnor, whose somber eyes reflect the iron will and fearlessness of primitive tribal life, had been healed by the Great Healer. Later, when a very old man, he was converted to the Christian religion.” Although both sets of captions—Iliff’s and Pierce’s—are obviously constructed by whites in order to categorize native subjects, Iliff’s exhibit a stronger ideological bias toward portraying the subjects as primitive.

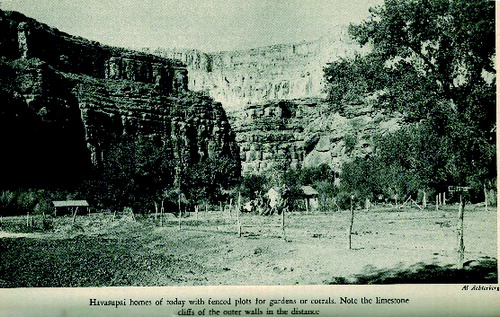

In addition to the Vesnor portrait, which clearly privileges Vesnor’s eventual conversion, one particular set of images suggests that Iliff is actually telling a very specific progress narrative, one that relegates her students' present culture to a long-gone past and glorifies the civilizational impulse at the heart of the boarding school process. In one photograph, Iliff depicts a “Mother carrying her baby in a burden basket. Her home is typical of the Havasupai house of a generation ago.” Although this is a picture of this woman’s house in the present tense of the narrative, Iliff skillfully relegates it to the far-off past in the caption. A page later, the last photograph in the book depicts “Havasupai homes of today with fenced plots for gardens or corrals” (). Not only do these homes look more like modern American houses, but the fencing is indicative of a central tenet of federal Indian policy that proved disastrous for many tribes: the breaking up of communally held lands into individual plots.

The photograph in is unusual because it is the only photograph that seems to have been taken closer to when the book was published (1954) than to when it was set (1900–04). The photographer credited on it, Al Achterberg, was a photojournalist in Nebraska who did not even start taking pictures until 1945 (Achterberg 48). Thus, although the entire book, with the exception of the last chapter, stands as what Lynn Bloom calls a “single-experience autobiography,” in that it retells only a short period of Iliff’s life, this final photograph reminds the reader that the story, along with the other memoirs that came out at around the same time, is situated in a much larger progress narrative that spans the first half of the twentieth century.

The 1950s marked a dramatic shift in federal policy toward Native Americans, a shift that was in many ways a return to the ideology of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—the setting of these memoirs. By the 1920s, the boarding school model of Indian education was in decline (Jacobs 169, 404). In 1934, Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act, which reversed earlier policies and embraced aspects of native cultures. Educationally, this meant the abandonment of the boarding school system in favor of community schools, an emphasis on vocational education, and the inclusion of indigenous cultures in school curricula (Burt 52; Fixico xiii). Guided by the tenets of progressive education and recent anthropological concepts of cultural pluralism and relativity, schools were to encourage “cultural revitalization” instead of enforced assimilation (Burt 52; Dippie 325).

While not always successful, the reforms instituted by the Indian Reorganization Act lasted until World War II. However, after the war, the federal government ushered in a new policy of “termination.”Footnote23 Under termination, certain tribes were deemed ready to be independent of their ward status, and thus their trust relationship with the government was dissolved. The policy was widely opposed by Native Americans (Burt 66; Dippie 340; Fixico 22; Szasz 113) and is now overwhelmingly considered to have been a failure (Burt; Nash et al.).Footnote24 The Havasupai were “drastically affected by the pressure to leave the reservations” ushered in by termination policies, especially given the location of their reservation in Grand Canyon National Park (Hirst loc. 3195). Along with termination, the government instituted a relocation program, which subsidized adults who wanted to move off a reservation to big cities, and provided education and job training (Fixico 139); the Havasupai were encouraged to relocate in 1956.Footnote25 While the extremity of the move toward termination was new, the “paternalistic supervision” was not (Fixico ix), and like the policies of the late nineteenth century, termination emphasized assimilation above all else.

Given this context, the attitudes that the memoirists exhibit about the enforced assimilation in which they took part in the early twentieth century are applicable to debates about termination and relocation that were occurring around the time of the texts' publication. In the final chapter, Iliff describes returning to Arizona in 1941, and reflects on the changes that had occurred. As the caption of the final photograph illustrates, Iliff is generally pleased with the evidence of civilization she observes, but she laments the closing of the boarding school at Truxton as “the tragedy of empty buildings that should be sheltering children and preparing them to live in an unaccustomed world” (269). The last photograph, like the last chapter, catapults the reader to “today,” to the present tense of the text’s composition and publication. In this way, Iliff reminds the reader of the necessity of her documentary project in the face of her assimilationist one; her description of returning to Arizona suggests that the vanishing she anticipated, and helped to bring about, has, at least in some sense, actually happened.

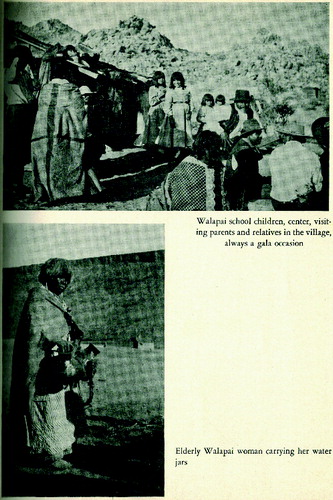

Even the photographs taken in the early 1900s, which make up the bulk of Iliff’s photography section, effect the vanishing of traditional Havasupai and Walapai culture. All of the children depicted in this section are in westernized school clothing; one photograph, captioned “Walapai school children, center, visiting parents and relatives in the village, always a gala occasion,” visually underscores this difference (). This image works like a candid version of the popular portraits of traditionally attired parents with their children dressed in school clothes that congeal documentary photography and aesthetic sentimental photography into a single image (Bernardin et al. 7).

As she does in the bottom image in , Iliff often labels the more traditionally appareled people as “old” or “elderly”—another indicator that the future of these people lies in assimilation. Iliff’s past|present distinction contributes to the idea of the “Vanishing American” that was popular at the time when she was teaching. According to historian Brian Dippie: “ethnography was the anthropological equivalent of wilderness preservation. It drew upon the belief in the Vanishing American and substantially reinforced it” (236). The authors' engagement with ethnography and their impulse to record a vanishing culture reinforces the notion that these tribes are already in the process of disappearing when they arrive. While Iliff sometimes regrets this loss, even when she views it as inevitable, she also uses the captions to emphasize the primitiveness of native cultures; she continuously makes clear “how many years of progress these people must in some miraculous way achieve before they could take their place in twentieth[-]century civilization” (154). As Helen Carr argues in her study of the “American Primitive,” which covers the period when Iliff taught: “the idea of the primitive made [it] possible for both liberals and reactionaries [to] remain innocent or claim to remain innocent, of the guilt of destroying it” (20). This notion of guilt is especially applicable to teachers like Iliff and the other memoirists, who had a direct and personal responsibility to destroy native culture. By emphasizing the primitive, as she does in her captions, Iliff justifies her assimilationist agenda and invokes what Renato Rosaldo has termed an “imperialist nostalgia,” wherein she mourns the loss of what she has helped to destroy (Bernardin et al. 14).

Given the prevalence of images of Native Americans in photography since its inception, and the renewed interest in Indians in the 1950s, it is not surprising that some of these images would have reinscribed popular stereotypes about Native Americans. In addition to reinforcing the notion of the Vanishing American and highlighting the primitiveness both of the people and their surroundings, photographs across the texts bolster the idea of the Noble Savage, the long-suffering Indian who contains the wisdom of the ages. Many critics have discussed the dangers of reducing “the Indian” to a symbol, a strategy that Iliff uses intermittently throughout the text, but succumbs to in her closing lines when she writes: “an Indian, standing with face uplifted to the morning light, communing with his gods, has become to me a symbol—a symbol of oneness with the spiritual world” (271).Footnote26 Here, Iliff references her first descent into the Havasupai’s canyon, when she “glanced up and saw a flash of crimson against a background of blue sky—an Indian standing on a white cliff, with face uplifted to the morning sun. His knee-length red blanket, tossed back, revealed strong brown shoulders and statuesque body. His long black hair, bound in a knot at the nape of his neck with strips of gay calico, and his moccasins and bright headband made a colorful picture against the clear blue” (96). This image of the Noble Savage is the guiding image of Iliff’s text. Like the Vanishing American, the Noble Savage perpetuates a stereotype that relegates Indians to the past or to the spiritual realm, and makes it easier to ignore their human needs and present reality.Footnote27 Other authors also include images of Native Americans in full headdresses and festal robes, and staged portraits that resemble the now well-known images of Edward Curtis.

Like Iliff, by the end of their books, most of these authors eventually embrace the civilizational ethos of the boarding school project. As such, the images ensconced in the narratives could simply be considered booster-images for assimilation and ethnographic evidence of a vanishing, primitive way of life. Iliff’s students emerge only in the few photographs included in this article: the two class pictures () and the shot of children returning to visit their parents ().

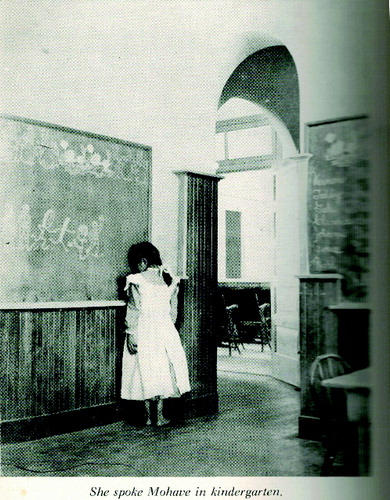

However, photographs of students in other memoirs often expose the underside of the campaign for assimilation through their depictions of punishment and silent resistance. Minnie Braithwaite Jenkins, author of Girl from Williamsburg, generally supports the assimilationist education she is expected to provide, although she disagrees with some of its more extreme measures. Like Iliff, Jenkins often embraces native customs and traditions, but she is unbending in her advocacy of English-only instruction, a basic tenet of Native American schooling which is now considered to have been highly traumatic. Jenkins frequently describes the use of corporal punishment to dissuade students from speaking their first language, and one of the nine photographs included in her memoir illustrates this practice (). The scene might seem relatively innocuous, but it is representative of more violent and restrictive practices to ensure student cooperation that are described throughout the texts.

While Jenkins is the most assimilationist of the memoirists, regardless of the teacher’s stated position on educational policy, each of these texts exposes resistance on the part of the Indian students. Contemporary studies of Native American children’s experiences in the boarding schools suggested that passive resistance such as stealing, truancy, and apathy was the only way that children could express their complaints about their disfranchisement (Erikson). Jenkins describes a rampant problem at Fort Mohave—namely, that young children, especially kindergartners, “become homesick for their mothers, [and] ha[ve] the habit of running home to camp” (280). Apparently, these children were collected and placed in a more secure facility, which Jenkins refers to as “jail,” even though parents were particularly upset over their children’s unhappiness. One day, the children staged a jailbreak: “At breakfast we heard it. The kindergartners not in jail had, with a big log for a battering ram, broken down the jail door, let out those inside, whereupon the entire class left to hide out in the river bottom!” (283); this type of student resistance, especially at such a young age, is telling.

In addition to recounting how children ran away (Iliff 214), how difficult it was to get students to come to school (Brown 235), and how some students refused to accept their diplomas (Golden 154), the memoirists detail even more extreme acts of resistance. Estelle Aubrey Brown, for example, recounts the tale of Tattyin, a Navajo who gouged out his daughter’s eye rather than send her to school (235). In Red Moon Called Me: Memoirs of a Schoolteacher in the Government Indian Service, Gertrude Golden describes how “some of the little Indian girls contrived a means of escaping from her [the matron] by being sent home. One night this desperate little group piled a lot of clothing in the middle of the floor of one of the dormitory rooms and set fire to it” (92). Like the little kindergartners that Jenkins describes, Golden’s wards evince a desperation that speaks to a deep and abiding unhappiness. Although she blames the tyrannical rule of the matron, this type of resistance was widespread in Indian schools, and together these incidents illustrate that children were trying to escape not just individuals, but the very concept of the Indian boarding school itself.Footnote28

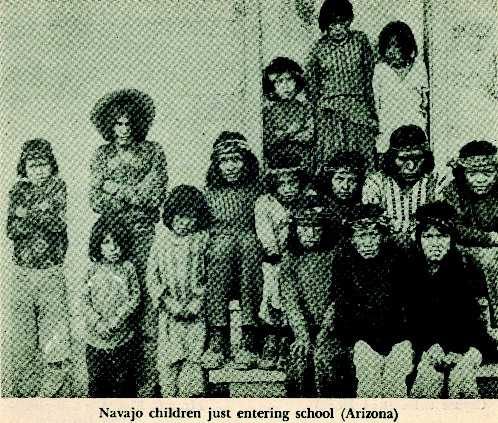

The many group portraits of students in both Western and native dress that Golden includes in her text, which are meant to serve as booster-images for Native American education, belie unhappiness and resistance. If Vizenor characterizes the Native American subjects of booster-images as “poster Indians,” then the children whose images pepper the memoirs become “poster (Indian) children” (152). Whether the “before” or “after” shot of assimilation, these photographs can be read as testaments to the silent resistance of the subjects, while at the same time the history of their usage serves as a reminder of the frequent futility of that resistance. depicts Navajo children with their arms often crossed and shoulders tensed. Even more than the photographs discussed above, images like this viscerally illuminate the violation of photography that Sontag and other scholars have identified. Such recognizable images, when placed in memoirs that both glamorize and expose the boarding school project, take on an added valence for a contemporary reader. As Vizenor notes of photographs taken by homesteaders, for the authors, photographs like these are a source of nostalgia but, for Native Americans, “they are a wound” (157). gives a contemporary reader pause about the intentions of the memoirists who included these types of images as evidence of the need for civilization, and reminds us of the ways in which our seeing and understanding are always temporally and culturally constructed.

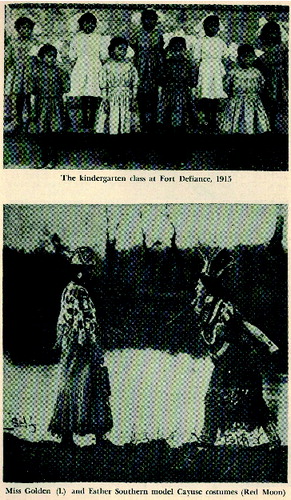

Like the memoirs themselves, Golden’s photography section is rife with strange juxtapositions. On the page shown in , Golden pairs a prim school picture of her kindergarteners (top) with a staged portrait of herself and a colleague in “Cayuse costumes” (bottom). The top image serves as a counterpoint to the image in ; although they are not the same children, the photographs were taken in the same area and illustrate the “before” and “after” images that were used as visual evidence of the success of the schools. These kindergartners do not look much happier than the students just entering school; for a contemporary reader, it is hard to imagine this as a celebratory image.

However, beyond the more obvious relationship between the two very similar “class pictures,” the juxtaposition of the two images on this single page () highlights the difference between the child-subjects and the memoirist-as-subject. Unlike many autobiographies, in which most of the pictures depict the autobiographer herself, most of the memoirs contain just one or two images of the author among the many other photographs. Golden includes more than most: a formal portrait; a group portrait of the teachers; a snapshot in which she appears on horseback; and this one, an image of her and her colleague, Southern, “model[ing] Cayuse costumes.” In this case, Golden and Southern are “playing Indian,” but contemporary analyses of portraits of Native Americans in similar outfits suggest that they, too, were often performing in costume.Footnote29 The image is a reminder of the staged nature of many of the photographs of Native Americans taken around this time, as it was a common practice by professional and amateur photographers alike to portray their native subjects as more “primitive” than they really were through the inclusion of artifacts or the exclusion of modern accouterments. This staged shot indicates the constructed nature of many of the photographs included in these memoirs; the reader knows that Golden is not what she seems in this image, which calls the authenticity of the other images into question. In fact, because of the placement of Golden’s face (in shadow) and the poor quality of the image, it is likely that, without a caption, the viewer would not be able to identify Golden or her race. Switching between the two images on this page is a reminder that the booster-images of successfully assimilated children, like the one at the top of the page, were staged in their own way as proof positive that the system was working.

At the same time, although the pairing reminds the contemporary reader of the performative nature of photography and autobiography, it also underscores the relative freedom, privilege, and power afforded to these memoirists. These authors could experiment with native customs and costumes, and document them for their white audience, while simultaneously eradicating them in the native populations in which they worked. Golden’s enactment of dressing up like an Indian is fun and games, but her students’ performance of their new identities is deadly serious. Likewise, these authors’ control over the narrative of their own lives as writers of their autobiographies and their decision to include the photographs where, when, and how they did stands in stark contrast to the anonymity of their silent subjects.

Notes

1. I have tried, in the following treatment, to heed Robert Berkhofer’s reminder that “the ‘Indian’ is a white construction,” given that this term encompassed at least 2,000 distinct cultures and societies (at the time of first contact) (4). When possible, I use specific tribal names and affiliations, but I use the generalized terms “Indians” or “Native Americans” when speaking about general US policy or white attitudes, when discussing trends across the texts, or when the memoirists themselves use more generalized language.

2. See Adams; Rugg; and Smith and Watson 76.

3. Smith and Watson summarize these concerns in the first chapter of Reading Autobiography (1–14). For a recent discussion of the political work memoir can do because of its claim to authentic representation, see Couser, Memoir 169–84.

4. For academic engagements with autobiographical hoaxes, see Aubrey; Eakin, Ethics 1–16, Living 17–21; Egan; Gilmore; Miller; and Nunes.

5. Pascal engaged with the nature and inconsistency of memory at the very beginning of the development of autobiography theory; since then, many scholars have invested this issue in the context of the genre (see, especially, works by Olney; Adams; and Eakin ). Smith and Watson lay out the key issues around memory and life writing (16–24), and make instability a central theme of their guide for interpreting life narratives.

6. Ben Yagoda’s Memoir: A History illustrates as much. He details many historical cases of hoaxes and audience disappointment.

7. Both Lionnet and Stone have commented on the similarities between anthropology and autobiography (Lionnet 103; Stone 7). See also Hornung; and Okely and Callaway.

8. The one exception is Brown: she includes “photo taken by Jack Riddle” on many of her images. It appears Jack Riddle was an amateur photographer, given the lack of a copyright invocation, and possibly a colleague.

9. Carlisle Indian School provided these types of “before” and “after” shots to funders (Preucel 20), and the Peabody Museum displayed similar photographs of students at the Hampton Institute at the Chicago Columbian Exposition in 1893 (Bernardin et al. 13).

10. See also Alison; and Capture.

11. Carter and Watson both make a similar claim about the choice to teach Native American children; they read these memoirs as protofeminist texts that suggested potential ways for white women to exist outside of traditional gender and sexuality norms.

12. Ruth Behar explores this issue of vulnerability in the context of anthropology.

13. Iliff’s text was reprinted by the University of Arizona Press in 1985. The four other memoirs were either self-published or published by regional presses, although In the Land of the Grasshopper Song was reprinted by the University of Nebraska Press|Bison Books in 1980.

14. Even the one reviewer who notes that Iliff “was no trained ethnologist” adds that her “unflagging interest in [Indian] legends and customs led her to ask questions, make friends, and, always try to understand” (Jackson, “Girl”). In his other review, he points out that, when Iliff was teaching, neither ethnology nor anthropology was “anywhere as advanced as it is today” (Jackson, “Havasupai”).

15. Carter explores each author’s position on this spectrum, although she generally views them as much more resistant to the system of Indian education than I do.

16. Although the specific ritual varies across the tribes, almost every memoirist includes some comment on mourning practices.

17. Jenkins echoes this attitude in her description of a Mohave burning ceremony when she writes: “some of the employees criticized the destruction of goods and belongings as foolish and wasteful; yet it probably cost no more than the flowers at many funerals of white people, and I have heard it stated by authorities that the burning of the Mohave dead together with their personal effects has stopped many an epidemic” (311).

18. According to Jenny Watts, Curator of Photographs at the Huntington Library, these original captions were written by C. C. Pierce or his associates at the time that the photographs were either taken or purchased.

19. Gertrude Golden, in particular, includes a vast array of images of people from various tribes. Although she traveled extensively and worked in many different locations, at least two of the photographs reference tribal affiliations from areas far from where she worked, which suggests that she did not take the photographs herself.

20. For an engagement with Native American images on postcards, see Albers and James.

21. These include the Vesnor portrait (photCL 2126), the aforementioned picture of “Chickpanagies' [sic] daughters” (photCL 2087), and a picture of a Havasupai woman making bread (photCL 2147). While the other pictures attributed to James are not date-stamped (photCL 2101; photCL2127; photCL2133; photCL2140), they would have likely been taken and sold in the same period. In addition, given that James published Indian Basketry and How to Make Indian and Other Baskets in 1903, and the book had more than 600 illustrations, it is likely that the very professionally staged still-life of baskets included in Iliff’s text could also be his (Guidi 226).

22. Based in Los Angeles, Pacific Stereopticon Co. produced slides from photographs that could be projected and viewed in people’s home with a dual projector. Iliff’s photograph of Manakadja, late chief of the Havasupai, is credited to this company, but the same photograph is housed in the Pierce Collection at the Huntington Library, with a handwritten notation that says: “copyrighted by G. Wharton James” (photCL 2101).

23. According to Fixico, 109 cases of termination were initiated, affecting a minimum of 1,362,155 acres and 11,466 individuals (181).

24. Some younger Indians supported termination (Fixico 123). Philp reminds us that “termination meant different things to different groups of Indians” (xi).

25. Approximately 61,500 Native Americans received vocational training under the relocation program (Fixico 190).

26. See Berkhofer; S. L. Smith 215; and Vickers. In “Thick Description,” Geertz addresses what he considers a “justifiable critique of anthropology”—namely, the difficulty of moving “from local truths to general visions” (21), which is a difficulty that Iliff encounters.

27. For histories and analyses of the Noble Savage idea, see Dippie 18–21 and Berkhofer 72–79, 88. Bird pairs the “noble” and “ignoble” savage as simultaneous images in her discussion of images of Native Americans throughout US history (3), and argues that the longest-lasting stereotype about Native Americans has been that the only “real” Indians are historical ones (8). Griffiths notes that: “for Americans disenchanted with the physical and social transformation of the modern American landscape, the myth of the Noble Savage became a mnemonic for cultural loss” (82); this is certainly true for Iliff.

28. For examples of Native American student resistance to imposed education, see Adams 209–39; Child and Lomawaima; Churchill 57–59; and Reyhner and Eder 185–89.

29. For a history of staging in both film and photography of the period, see Griffiths.

Works Cited

- Achterberg, Robert Alan. “Photographs as Primary Sources for Historical Research and Teaching in Education: The Albert W. Achterberg Photographic Collection.” Diss. U of Texas at Austin, 2007. Dissertation Full Text. Web. 12 Mar. 2013.

- Adams, David Wallace. Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875–1928. Lawrence: UP of Kansas, 1995. Print.

- Adams, Timothy Dow. Light Writing and Life Writing: Photography in Autobiography. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 2000. Print.

- Albers, Patricia C., and William R. James. “Illusion and Illumination: Visual Images of American Indian Women in the West.” The Women’s West. Ed. Susan Armitage and Elizabeth Jameson. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 1987. 35–50. Print.

- Alison, Jane, ed. Introduction. Native Nations: Journeys in American Photography. London: Barbican, 1998. 11–21. Print.

- Arnold, Mary Ellicott, and Mabel Reed. In the Land of the Grasshopper Song: Two Women in the Klamath River Indian Country in 1908–09. 1957. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P|Bison, 1980. Print.

- Aubrey, Timothy. “The Pain of Reading A Million Little Pieces: The James Frey Controversy and the Dismal Truth.” a|b: Auto|Biography Studies 22.2 (2007): 155–80. Project MUSE. Web. 23 Apr. 2012.

- Behar, Ruth. The Vulnerable Observer: Anthropology That Breaks Your Heart. Boston: Beacon, 1996. Print.

- Berkhofer, Robert F., Jr. The White Man’s Indian: Images of the American Indian from Columbus to the Present. New York: Knopf, 1978. Print.

- Bernardin, Susan, et al., eds. Introduction. Trading Gazes: Euro-American Women Photographers and Native North Americanism 1880–1940. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 2003. 1–31. Print.

- Bloom, Lynn Z. “Single-Experience Autobiographies.” a|b: Auto|Biography Studies 3.3 (1987): 36–45. Print.

- Brown, Estelle Aubrey. Stubborn Fool: A Narrative. Caldwell, ID: Caxton, 1952. Print.

- Burt, Larry W. Tribalism in Crisis: Federal Indian Policy, 1953–1961. Albuquerque: U of New Mexico P, 1982. Print.

- Capture, George Horse. “They're Taking Our Children.” Native Nations: Journeys in American Photography. Ed. Jane Alison. London: Barbican, 1998. 25–39. Print.

- Carr, Helen. Inventing the American Primitive: Politics, Gender and the Representation of Native American Literary Traditions, 1789–1936. New York: New York UP, 1996. Print.

- Carter, Patricia A. “‘Completely Discouraged’: Women Teachers' Resistance in the Bureau of Indian Affairs Schools, 1900–1910.” Frontiers 15.3 (1995): 53–86. JSTOR. Web. 23 Apr. 2012.

- Child, Brenda J., and K. Tsiannina Lomawaima. “Life at School.” Away from Home: American Indian Boarding School Experiences. Ed. Margaret L. Archuleta, Brenda J. Child, and K. Tsiannina Lomawaima. Phoenix: Heard Museum, 2000. 13–53. Print.

- Churchill, Ward. Kill the Indian, Save the Man: The Genocidal Impact of American Indian Residential Schools. San Francisco: City Lights, 2004. Print.

- Clifford, James. The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1988. Print.

- “Collection Guide: C. C. Pierce Collection of Photographs.” Biographical Note. Online Archive of California (The Huntington Library Photo Archive). Web. 12 Mar. 2013.

- Couser, G. Thomas. Memoir: An Introduction. New York: Oxford UP, 2012. Print.

- —. Vulnerable Subjects: Ethics and Life Writing. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2004. Print.

- Debo, Angie. “At the Floor of the Canyon.” Rev. of People of the Blue Water, by Flora Gregg Iliff. New York Times 31 Oct. 1954: BR26. Historical Newspapers. Web. 23 Apr. 2012.

- Dippie, Brian W. The Vanishing American: White Attitudes and U.S. Indian Policy. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan UP, 1982. Print.

- Eakin, Paul John, ed. The Ethics of Life Writing. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2004. Print.

- —. Living Autobiographically: How We Create Identity in Narrative. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2008. Print.

- Egan, Susanna. Burdens of Proof: Faith, Doubt, and Identity in Autobiography. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2011. Print.

- Erikson, Erik H. Childhood and Society. 1950. New York: Norton, 1963. Print.

- Fischer, Michael M. J. “Ethnicity and the Post-Modern Arts of Memory.” Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Ed. James Clifford and George E. Marcus. Berkeley: U of California P, 1986. 194–233. Print.

- Fixico, Donald L. Termination and Relocation: Federal Indian Policy, 1945–1960. Albuquerque: U of New Mexico P, 1986. Print.

- Geertz, Clifford. “Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture.” The Interpretation of Culture: Selected Essays. Ed. Clifford Geertz. New York: Basic, 1973. 3–30. Print.

- —. Works and Lives: The Anthropologist as Author. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 1988. Print.

- Gilmore, Leigh. “American Neoconfessional: Memoir, Self-Help, and Redemption on Oprah’s Couch.” Biography 33.4 (2010): 657–79. Project MUSE. Web. 23 Apr. 2012.

- Golden, Gertrude. Red Moon Called Me: Memoirs of a Schoolteacher in the Government Indian Service. San Antonio, TX: Naylor, 1954. Print.

- Griffiths, Alison. “Science and Spectacle: Native American Representation in Early Cinema.” Dressing in Feathers: The Construction of the Indian in American Popular Culture. Ed. S. Elizabeth Bird. Boulder, CO: Westview, 1996. 79–95. Print.

- Guidi, Benedetta Cestelli. “The Pen and the Gaze: Narratives of the Southwest at the Turn of the Century.” Native Nations: Journeys in American Photography. Ed. Jane Alison. London: Barbican, 1998. 223–27. Print.

- Hirst, Stephen. I Am the Grand Canyon: The Story of the Havasupai People. Grand Canyon: Grand Canyon Assn., 2007. Kindle ed.

- Hornung, Alfred. “Anthropology and Life Writing.” Encyclopedia of Life Writing: Autobiographical and Biographical Forms. Ed. Margaretta Jolly. London: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2001. 38–41. Print.

- Hoxie, Frederick E. A Final Promise: The Campaign to Assimilate the Indians, 1880–1920. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1984. Print.

- Iliff, Flora Gregg. People of the Blue Water: My Adventures among the Walapai and Havasupai Indians. New York: Harper, 1954. Print.

- Jackson, Joseph Henry. “Girl in Love with Indian Heaven of the West.” Rev. of People of the Blue Water, by Flora Gregg Iliff. Chicago Sunday Tribune 12 Sept. 1954: 4. Print.

- —. “With the Havasupai Half a Century Ago.” Rev. of People of the Blue Water, by Flora Gregg Iliff. San Francisco Chronicle 3 Sept. 1954: 19. Print.

- Jacobs, Margaret D. White Mother to a Dark Race: Settler Colonialism, Maternalism, and the Removal of Indigenous Children in the American West and Australia, 1880–1940. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 2009. Print.

- Jenkins, Minnie Braithwaite. Girl from Williamsburg. Virginia: Dietz, 1951. Print.

- Katakis, Michael, ed. Excavating Voices: Listening to Photographs of Native Americans. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania Museum, 1998. Print.

- Lejeune, Philippe. On Autobiography. 1975–86. Trans. Katherine Leary. Ed. Paul John Eakin. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1989. Print.

- Lionnet, Françoise. Autobiographical Voices: Race, Gender, Self-Portraiture. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1989. Print.

- Miller, Nancy K. “The Entangled Self: Genre Bondage in the Age of Memoir.” PMLA 122.2 (2007): 537–48. Print.

- Nash, Philleo, et al. “Federal Indian Policy, 1945–1960.” Indian Self-Rule: First-Hand Accounts of Indian-White Relations from Roosevelt to Reagan. Ed. Kenneth R. Philp. Salt Lake City: Howe, 1986. 129–41. Print.

- Nunes, Mark. “A Million Little Blogs: Community, Narrative, and the James Frey Controversy.” Journal of Popular Culture 44.2 (2011): 347–66. Humanities Full Text. Web. 23 Apr. 2012.

- Okely, Judith, and Helen Callaway, eds. Anthropology and Autobiography. London: Routledge, 1992. Print.

- Philp, Kenneth R. Termination Revisited: American Indians on the Trail to Self-Determination, 1933–1953. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1999. Print.

- Preucel, Robert W. “Learning from the Elders.” Excavating Voices: Listening to Photographs of Native Americans. Ed. Michael Katakis. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania Museum, 1998. 17–26. Print.

- Rev. of People of the Blue Water, by Flora Gregg Iliff. Time 13 Sept. 1954: 122. Academic Search Complete. Web. 23 Apr. 2012.

- Reyhner, Jon, and Jeanne Eder. American Indian Education: A History. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 2004. Print.

- Rosaldo, Renato. “Imperialist Nostalgia.” Representations 26 (1989): 107–22. JSTOR. Web. 12 Mar. 2013.

- Rugg, Linda Haverty. Picturing Ourselves: Photography and Autobiography. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1997. Digital ed.

- Smith, Elenore Taney. Rev. of People of the Blue Water, by Flora Gregg Iliff. Library Journal 1 Sept. 1954: 1498. Print.

- Smith, Sherry Lynn. Reimagining Indians: Native Americans through Anglo Eyes, 1880–1940. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2000. Print.

- Smith, Sidonie, and Julia Watson. Reading Autobiography: A Guide to Interpreting Life Narratives. 1st ed. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2001. Print.

- Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Farrar, 1973. Kindle ed.

- Stone, Albert E. Autobiographical Occasions and Original Acts: Versions of American Identity from Henry Adams to Nate Shaw. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 1982. Print.

- Szasz, Margaret. Education and the American Indian: The Road to Self-Determination since 1928. 3rd ed. Albuquerque: U of New Mexico P, 1999. Print.

- Vickers, Scott B. Native American Identities: From Stereotype to Archetype in Art and Literature. Albuquerque: U of New Mexico P, 1998. Print.

- Vizenor, Gerald. Fugitive Poses: Native American Indian Scenes of Absence and Presence. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1989. Print.

- Watson, Julia. ‘“As Gay and Indian as They Chose’: Collaboration and Counter-Ethnography in The Land of the Grasshopper Song.” Biography 31.3 (2008): 397–428. Project MUSE. Web. 12 Mar. 2013.

- Yagoda, Ben. Memoir: A History. New York: Riverhead, 2009. Print.