Abstract

Heart failure is a chronic health condition characterized by complex symptom management and costly hospitalizations. Hospitalization for the treatment of heart failure symptoms is common; however, many hospitalizations are thought to be preventable with effective self-management. This study describes the small, pilot implementation of a new, interventional, self-management heart failure program, “Engagement in Heart Failure Care” (EHFC), developed to assist heart failure patients with the management of disease symptoms following discharge from an inpatient hospital stay. EHFC was designed to engage patients in managing their symptoms and coaching them in skills that enable them to access medical and supportive care services across community, clinic, and hospital settings to help address both their current and future needs. The results of this pilot study suggest that EHFC’s coaching model may have positive benefits on key health and well-being indicators of the patients enrolled.

The program Engagement in Heart Failure Care (EHFC) is based on the successful Care Transitions InterventionCitation1 but was enhanced specifically for the heart failure (HF) population and is 3 months long rather than 30 days. Patients in EHFC are assigned a health coach who helps monitor their HF symptoms to identify adverse symptoms early, provide structured support, identify any medication discrepancies, and regularly check in on goals and skill-building according to the patient’s needs. EHFC incorporates evidence-based and evidence-informed care for HF into a practical, structured approach within the context of team-based care.

HF is a chronic health condition characterized by complex symptom management and costly hospitalizations. Approximately 6.5 million Americans over the age of 20 are affected by HF and about 14% of Medicare beneficiaries have HF; 80% of elderly HF patients experience an HF-related hospitalization. Furthermore, HF has one of the highest 30-day readmission rates in the US.Citation2 Its prevalence is expected to increase by 46% from 2012 to 2030. Based on 2013 estimates, the total cost of HF is projected to increase by 120% from $32 billion to $70 billion by 2030.Citation3 Lack of patient engagement in self-care behaviors negatively impacts disease progression.Citation4–6 In addition, a lack of adherence to medication regimens and instructions from healthcare providers may lead to hospitalization. In the US, medication nonadherence is estimated to cost the healthcare system $100 to $289 billion annually.Citation7 If nonadherence to cardiovascular medication regimens can be addressed with improved continuity of care, the incidence of HF exacerbations may be reduced.Citation8

Hospitalization for the treatment of HF symptoms is common; however, many hospitalizations are thought to be preventable with effective self-management.Citation9 Supporting self-management of chronic disease has been identified as a national priority under the National Chronic Disease Strategy.Citation10 According to the World Health Organization, self-management, also known as “patient empowerment,” is defined as “a process through which people gain greater control over decisions and actions affecting their health.”Citation11 Patients with chronic diseases are seen as taking an active part in their disease management, and physicians and other healthcare providers are seen as consultants.Citation12 A systematic review of 11 randomized trials showed that self-management strategies involving a multidisciplinary team-based approach reduced hospitalizations and increased cost savings.Citation13

An important aspect of self-management is goal setting, a common therapeutic tool that has proven to be effective in symptom management across several disease conditions.Citation14–18 According to the social cognitive theory, goal setting and other self-regulation strategies are heavily influenced by self-efficacy, outcome expectations, modeling, skill building, and the social and physical environment.

Recent studies address the importance and need for innovative clinic- and community-based care programs in maximizing patient engagement in self-care of HF symptoms in bringing a positive impact upon patient/physician interactions.Citation19,Citation20 Better-informed patients (who receive information in a meaningful way) appear to be better performers in managing their care.Citation5

The use of technology in self-management is of broad and emerging interest. This study constituted a pilot examination of one such technology-assisted intervention to help patients and potentially healthcare staff monitor HF symptoms more closely. The current study describes the implementation of a self-management HF program and presents findings of key health and well-being indicators of the participants in these limited cohorts.

METHODS

The institutional review board at Baylor Scott & White Health reviewed all procedures associated with this program and approved the program via expedited review. Participants were consented for the study using an approved consent form. Participants were given an explanation of the study and what their participation would involve and then were asked to sign a written consent form. Participants volunteered to answer all program-related questions. Medical records were reviewed to confirm eligibility criteria for patients who were seen in the HF clinic. provides a visual of the methods. EHFC was implemented in a nonprofit hospital located in Temple, Texas. Patients were enrolled from April 2017 to January 2018.

Identification of patients

In collaboration with HF clinic practitioners, we identified common characteristics in HF patients associated with high risk for HF readmission. Patients who were recently discharged from an inpatient unit were identified to schedule their follow-up appointments. HF coordinators flagged charts of patients who met eligibility criteria. Weekly email communications were sent to the HF cardiology team, and clinical staff included a list of recently discharged patients eligible for the study. The social workers were authorized to call and schedule follow-up appointments for these patients and to present the study to them. Integration of EHFC into existing workflow within the Baylor Scott & White system was critical to the identification of eligible patients; it allowed hospital staff to screen all patients with HF who were discharged and were potentially eligible.

Eligibility criteria

The study population consisted of patients who (1) were recently discharged (within 7 days) from the hospital and for whom follow-up was planned in outpatient services at Baylor Scott & White; (2) were Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries or dual-eligible (Medicare plus Medicaid); (3) were at least 18 years of age; (4) resided in the community in six central Texas counties; (5) spoke English; and (6) fulfilled one or more criteria identifying a high risk for HF readmission. It is common for managed Medicare plan groups to have their programs offer targeted interventions to reduce readmission, so it was decided to exclude these patients in the study population to avoid any overlap and/or duplication of services.

High risk for readmission was determined by meeting at least one of the following criteria: New York Heart Association class II on a postdischarge visit; worsening hypotension while on cardiac medications; restrictive cardiomyopathy; left ventricular ejection fraction ≤35%; cardiogenic shock during recent admission; another comorbidity along with HF (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter, or ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation); taking >9 medications; using home oxygen, blood thinners, or insulin; or at least one emergency department visit or hospitalization in the last 6 months prior to recent admission. Participants were excluded if they were non-Medicare, were a permanent nursing home resident, had a diagnosis of dementia or cognitive impairment, were discharged to a skilled nursing facility or admitted to an inpatient psychiatry unit within the last 90 days, or were using intravenous infusions for medication and/or fluid intake.

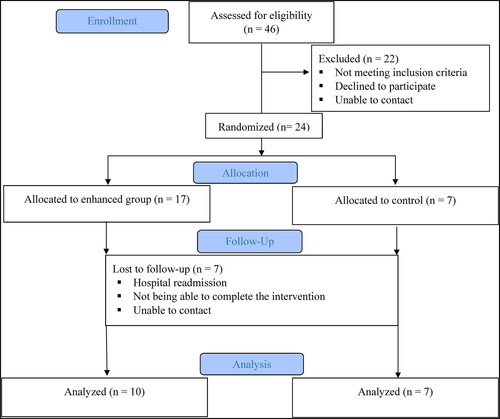

Of the 46 patients who were referred to EHFC, 24 were enrolled and randomized (). Reasons for nonenrollment included ineligibility, inability to contact, and declining to consent.

Study design

Patients were randomized into a control group or enhanced group using the RAND function in Excel. All patients received educational materials, two home visits to complete assessments, a medication card, and access to the patient portal for the healthcare system’s electronic health record system (). Patients in the EHFC group received a formal schedule of weekly therapeutic contacts across 3 months and two therapeutic home visits with their health coach. Additional contacts were provided if warranted. A key component of the EHFC group was that participants received a personal health record and access to a daily health tracker, which is described in the next section. Home visits allowed for the presentation of the care plan, any revisions, structured support, and skill-building sessions based on the participants’ needs. Phone calls provided an opportunity to check in on goals and symptoms that week and make any necessary adjustments. Patients in the control group received two follow-up phone calls. Participants in the study received $25 for completing the baseline assessment and $25 at the end of the intervention for completing the 3-month assessment.

Table 1. Intervention components

Daily health tracker and coaching dashboard. EHFC utilized Baylor Scott & White eSurvey software, based on the Qualtrics platform, to facilitate communication between the coach and patient. The survey software was used to collect patient-reported data regarding HF symptoms (weight, blood pressure, swelling, shortness of breath, dizziness) and progress toward goals. The daily responses submitted fed into a dashboard accessible to the assigned health coach. The purpose of monitoring these symptoms daily was to identify adverse symptoms early, before they warranted a hospital admission.

Alerting system. The system had alerting capabilities that could use the patient-reported outcomes in real time to inform the coach of any issues, thus providing a continuous feedback loop from patient to provider within the patient’s daily activity. When alerts were triggered based on the patient’s response to questions about weight, swelling, shortness of breath, or dizziness, a message was displayed on the application that instructed the patient to contact their primary care provider/specialist immediately, and the coach would attempt to call the patient as well. Furthermore, the software had text messaging survey capabilities so reminders or questions about fluid intake, for example, could be sent to the patient through a mobile phone or their iPad, asking them to log information that was vital to the management of their disease. Patients who had a smartphone and/or computer had the patient’s daily health tracker application installed on their devices during the first home visit with the health coach. The health coach completed a coaching interaction form for all interactions with the patient, whether over the phone or in person.

Medication discrepancies. Medication discrepancies were noted within the dashboard. If the health coach and the patient discovered any medication discrepancies during the initial home visit, the health coach completed a medication discrepancy form. The health coach noted the type of medication and any patient- or system-level cause and contributing factor that applied. After the causes and contributing factors, the health coach recorded the resolution suggested to the patient. The coach encouraged the patient to resolve any medication discrepancies with their provider.

Goal tracking. In addition to tracking symptoms and identifying any medication discrepancies, an important component of the coaching dashboard was goal tracking. At the initial home visit, coaches made an overall program goal as well as a weekly goal of interest to the patient aimed at incrementally (over the course of the program) reaching the overall program goal. On each weekly call, coaches asked the patient about their progress toward meeting their weekly goal. The health coach and patient assessed the ongoing importance, difficulty, and attainment score for each weekly goal. The weekly goals were to be realistically achievable within a week and built up to the overall goal. If a patient accomplished their goal, a new incremental weekly goal was set. If the patient abandoned their goal, coaches talked with them about the possible barriers or challenges in achieving the goals and brainstormed ways to prevent and prepare for these challenges. The coach tracked goal progression, achievement, and abandonment within the dashboard.

Measures

All measures used at the baseline and 3 months were standardized assessments. Measures are described briefly below and were selected based on our desire to capture the impact of the program on patient self-efficacy, physical activity, general health, and patient activation regarding maintenance. All measures were self-reported.

Self-Care of HF index version R6.2 03-09. This questionnaire measures patient activation regarding maintenance according to an ordinal Likert scale (1 = never or rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = frequently, 4 = always or daily), management (1 = not likely, 2 = somewhat likely, 3 = likely, 4 = very likely) and confidence (1 = not confident, 2 = somewhat confident, 3 = very confident, 4 = extremely confident) in regards to HF self-care.Citation21

Rapid assessment of physical activity. This 9-item questionnaire assesses the level of physical activity for older adult patients (1 = yes, 2 = no).Citation22

Self-efficacy for managing chronic disease. This 6-item scale measures confidence in doing certain activities related to disease management (1 = not at all confident, 10 = totally confident).Citation23

Healthy days core module (CDC HRQOL-4). This one-item question measures the status of general health where 1=poor, 2=fair, 3=good, 4=very good, and 5=excellent.Citation24

The 3-month assessment included the same questions as the baseline with additional questions on program satisfaction (1 = not satisfied, 2 = somewhat satisfied, 3 = satisfied, 4 = very satisfied).

Statistical analysis

Participants’ characteristics at the time of enrollment were tabulated by frequencies and percentages or described by mean. We compared demographic characteristics (e.g., race, gender, age), patient activation, physical activity, self-efficacy for managing disease, and general health between those who completed a follow-up assessment for both groups. Patient satisfaction with the program was also analyzed using descriptive statistics. SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for the statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Among the 24 patients enrolled, 7 were randomized into the control group and 17 into the enhanced group. The intended randomization ratio was 1:1. The study was terminated early due to lack of enrollment, leading to uneven group size. The control and enhanced groups were similar regarding their high-risk characteristics, having an average of 3.6 and 3.4 high-risk characteristics, respectively. The average number of home visits for the enhanced group was 1.4, and the control group did not have any home visits with the health coach, as that was not included in their intervention activities. The number of calls completed for the control group ranged from 1 to 2, with an average number of 1.6 calls. The number of calls completed for the enhanced group ranged from 0 to 12 calls, with an average number of 5.4. The demographic characteristics of participants at baseline are shown in .

Table 2. Demographic characteristics and program components

Patient outcomes

Patients in the enhanced group had a higher mean score compared to the control group at follow-up for general health with a statistically significant mean change (3.0 vs. 2.7) and self-efficacy score (7.2 vs. 7.0). In addition, the enhanced group had higher mean scores for self-care maintenance and Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity at follow-up and a higher mean change from baseline to follow-up that was statistically significant compared to the control group. Although the enhanced group and control group had the same self-management scores at follow-up, the enhanced group showed a greater mean change (9.7 vs. 5.0) ().

Table 3. Patient measures at baseline and 3 months

Patient satisfaction

Overall, the enhanced group as expected had higher satisfaction with their participation in the program, noting that the program helped them understand their heart condition and their medications, eat less salt, exercise more, set goals, monitor their symptoms and blood pressure, track their weight, and recognize when to call their doctor (). Descriptive feedback for the EHFC cohort included comments that the program helped patients with motivation, understanding of their diagnosis, stress management, and goal setting and improved their quality of life. They mentioned that the coaches were easy to talk to and friendly, even saying that the “coach was a lifeline.” Suggestions for improvement included a request for the program to review the DASH diet and expand on the importance of daily weights. A few patients wished there were more in-person visits with the coach. Patients in the control group wished that there was more follow-up with the coach.

Table 4. Satisfaction that the program helped…

DISCUSSION

Though hospitalization for the treatment of HF symptoms is common, many rehospitalizations are thought to be preventable. The results of our small pilot EHFC study suggest that patients in the enhanced coaching group had higher self-reported overall health, self-efficacy, self-care maintenance, and Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity scores at follow-up compared to the control group.

Limitations and future research

Due to the very small sample size, especially in the control group, the results of this single hospital study should be viewed as hypothesis generating and not attributable solely to the EHFC intervention. Generalization to the overall HF population is similarly precluded, due to both limited power and overt skew of the sex of participants enrolled. Future studies may be conducted with larger sample sizes and designs that include comparative effectiveness studies in which EHFC is compared to existing programs such as implanted pulmonary artery monitoring (e.g., CardioMEMS).

Coupling education programs with other interventions (e.g., using technology within electronic health records) may enhance effectiveness. This is especially important in HF programs focusing on daily monitoring of weight and diet, as demonstrated in this study. The use of readily available technology can enhance communication between the healthcare team and the HF patients as implemented with the coaching dashboard used in this study. Moreover, technology-enhanced communication can be used to prompt patient engagement in self-management activities and facilitate communication of health information via secure patient portals (e.g., MyChart).Citation6 These types of applications help improve commitment and adherence to self-managed chronic diseases such as HF. In addition, regular monitoring and daily tracking can provide healthcare providers with valuable data in tracking disease progression or deterioration.

The EHFC program paired traditional self-monitoring with electronically facilitated monitoring by a health coach. In this pilot study, EHFC’s coaching model appeared to have positive benefits on the health and well-being of the patients enrolled.

Disclosure statement

This work was supported by the Collaborative Faculty Research Investment Program at Baylor Scott & White Health. The authors report no competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

- Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min S-j The Care Transitions Intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–1828. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822.

- Hall MJ, DeFrances CJ, Williams SN, Golosinskiy A, Schwartzman A. National Hospital Discharge Survey: 2007 summary. Natl Health Stat Report. 2010;24(29):1–20.

- Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129(3):e28–e292. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80.

- Peikes D, Jenevro G, Scholle S, Torda P. The Patient-Centered Medical Home: Strategies to Put Patients at the Center of Primary Care. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/ncepcr/tools/PCMH/strategies-to-put-patients-at-center-of-primary-care-brief.pdf. 2011.

- Sherman RO. The patient engagement imperative. American Nurse Today. 2014;9(2):1–4. https://www.myamericannurse.com/the-patient-engagement-imperative/#:∼:text=Nurses%20must%20embrace%20and%20support,own%20health%20and%20health%20care.

- Institute for Health Technology Transformation. A Roadmap for Provider-Based Automation in a New Era of Healthcare. 2012. https://www.exerciseismedicine.org/assets/page_documents/PHM%20Roadmap%20HL.pdf.

- Viswanathan M, Golin CE, Jones CD, et al. Closing the quality gap: revisiting the state of the science (vol. 4: medication adherence interventions: comparative effectiveness). Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2012;(208.4):1–685.

- Murray MD, Young J, Hoke S, et al. Pharmacist intervention to improve medication adherence in heart failure: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(10):714–725. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-146-10-200705150-00005.

- Jovicic A, Holroyd-Leduc JM, Straus SE. Effects of self-management intervention on health outcomes of patients with heart failure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2006;6(1):43. doi:10.1186/1471-2261-6-43.

- National Health Priority Action Council. National Chronic Disease Strategy and the Frameworks. Canberra, Australia: Department of Health and Aging; 2006.

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care. 2009. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241597906.

- Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288(19):2469–2475. doi:10.1001/jama.288.19.2469.

- McAlister FA, Stewart S, Ferrua S, McMurray JJ. Multidisciplinary strategies for the management of heart failure patients at high risk for admission: a systematic review of randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(4):810–819. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.055.

- Brown VA, Bartholomew LK, Naik AD. Management of chronic hypertension in older men: an exploration of patient goal-setting. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;69(1-3):93–99. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2007.07.006.

- Heisler M, Vijan S, Anderson RM, Ubel PA, Bernstein SJ, Hofer TP. When do patients and their physicians agree on diabetes treatment goals and strategies, and what difference does it make? J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(11):893–902. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21132.x.

- Pearson ES. Goal setting as a health behavior change strategy in overweight and obese adults: a systematic literature review examining intervention components. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87(1):32–42. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.018.

- Reuben DB, Tinetti ME. Goal-oriented patient care—an alternative health outcomes paradigm. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):777–779. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1113631.

- Strecher VJ, Seijts GH, Kok GJ, et al. Goal setting as a strategy for health behavior change. Health Educ Q. 1995;22(2):190–200. doi:10.1177/109019819502200207.

- Albert NM. Parallel paths to improve heart failure outcomes: evidence matters. Am J Crit Care. 2013;22(4):289–296. doi:10.4037/ajcc2013212.

- Schwarz KA, Elman CS. Identification of factors predictive of hospital readmissions for patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2003;32(2):88–99. doi:10.1067/mhl.2003.15.

- Riegel B, Lee CS, Dickson VV, Carlson B. An update on the self-care of heart failure index. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009;24(6):485–497. doi:10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181b4baa0.

- University of Washington Health Promotion Research Center. Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity (RAPA). Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 2006.

- Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL, Laurent D, Hobbs M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4(6):256–262.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Questionnaire—Healthy Days Core Module (CDC HRQOL– 4). Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2004.