ABSTRACT

The premier's annual press conferences are an interpreter-mediated and institutionalised event, which enables the Chinese government to articulate its official discourse on a variety of topics in front of a domestic and international audience. Framing the conferences as part of an autopoietic system, following Luhmann, helps to shed light on the imperative for such systems to legitimate themselves for their autonomous and continued existence through discourse. This is achieved, in part, through self-reference. Drawing on a corpus-based study informed by Critical Discourse Analysis, we explore the government-affiliated interpreters' mediation of Beijing's discourse on different levels using self-referential terms. The interpreters are found to frequently add self-referential terms (e.g. we, our, government, China) in English overall. They are also observed employing the broader WE (e.g. we, our, us) proportionally at the expense of the premier's personal voice I and that of the GOVERNMENT and CHINA. The interpreters' institutional positioning and identity as part of the government is therefore confirmed through their explicit discursive interventions, which help convey what Searle terms ‘collective intentionality’ and contribute to the legitimacy of the government. The discursive effects of these are discussed using bilingual examples.

Introduction

The Premier-Meets-the-Press conferences are an interpreter-mediated televised event held annually in the Chinese capital Beijing. Facilitated by consecutive interpreting, this discursive event enables Beijing to articulate its version of the ‘Chinese story’ in front of the global audience in the international lingua franca, that is, English. The government interpreters are usually communist party members and are recruited into China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs as part of China’s ruling elite. The ideological nature of this interpreted institutional event highlights the potential mediation role of the interpreter in aligning with Beijing’s discourse, (re)constructing a certain image and contributing to the government’s legitimacy as an institution.

The ability for an autonomous and self-regulating institution to maintain and reproduce itself is crucial. According to Luhmann (Citation1990, p. 19), every (political) system is confronted with the need to form a unique identity and the ‘imperative to legitimate itself’. It is through self-referencing that an autonomous, or autopoietic, system recursively ‘produces and reproduces the elements’ central to itself (ibid., pp. 39–40). It can be argued that, to varying degrees, all systems, institutions, and organisations thrive on self-reference for their autonomous and continued existence (e.g. in the form of institutional rules and policies). That is, although the repeated (re)production of self-references might be ‘logically circular and therefore empty’ (Luhmann, Citation1990, p. 41), self-reference constitutes a vital ‘modus operandi of the system’ (Lambropoulou, Citation1995, p. 694) nonetheless. In a context of international relations and globalisation, system legitimation is shaped by myriad external influences that inevitably entail multilingual engagement. As Koskinen (Citation2014:, p. 480) observes, governments operating in multilingual contexts ‘unavoidably [need] to develop a relationship to translation’. Self-referentiality and the translation regime in which it operates are therefore worthy of particular scholarly attention.

As part of a series of studies exploring the government interpreters’ agency and discursive mediation from different perspectives (Gu, Citation2018, Citation2019a, Citation2019b, Citation2019c) at the premier’s press conferences, this corpus-based CDA study examines the interpreters’ mediation of the premier’s discourse through self-referential items. From an interpreting perspective, ‘self-referentiality’ is important on at least two major counts. Firstly, it is central to the investigation of the interpreters’ identity and institutional alignment enacted in their interpreting product. The first-person plural pronoun ‘we’ and its various related forms (our, ours, us, ourselves), for example, have long been considered as salient markers of group membership and institutional alignment in Critical Discourse Analysis and beyond. This includes ‘in-group’ identity (Van Dijk, Citation1984), ‘institutional identity’ (Sacks, Citation1992) and footing (Goffman, Citation1981). Apart from only indicating issues of institutional alignment and identity, as Beaton (Citation2007, p. 277) argues in her study investigating metaphor strings in the EU, self-referentiality can serve to strengthen the process of ‘ideological stabilisation’ within a particular institution. As such, the way in which self-referential items are rendered by the interpreters concerns, for instance, how a government’s institutional presence, ideology and voice might be sustained, weakened or strengthened and, as a result, how this might effect change to the institution’s hegemony in a different language.

Despite the fact that the interpreters’ use of institutional self-referential terms may be highly salient in illuminating their degree of agency and ideological mediation, it has seldom been explored in interpreting studies (IS). However, as part of a growing trend of product-oriented research, scholars in interpreting studies have increasingly explored interpreters’ active agency and (ideological) mediation in various political and institutional settings (e.g. Beaton-Thome, Citation2013; Diriker, Citation2004; Mason, Citation1999; Wadensjö, Citation1998; Wang & Feng, Citation2018), drawing, for example, on critical discourse analysis, conversation analysis, participation framework and SFL. This line of research has focused attention on such categories as modality (Li, Citation2018), ideologically salient lexical items and lexical labelling (Beaton-Thome, Citation2013), ‘critical points’ (Wang & Feng, Citation2018), present perfect constructions (Gu, Citation2018), the enactment of positive self versus negative other (Gu, Citation2019a; Citation2019b) and the mediation of people-related items (Gu, Citation2019c) in interpreting. While some studies have explored issues of footing in consecutive interpreting in the Chinese setting (e.g. Sun, Citation2012), issues of self-referentiality focusing on EU interpreters in the simultaneous mode (e.g. Beaton-Thome, Citation2010) and the interpreters’ alignment when positioned between different sides with different ideological beliefs at political press conferences (Gu, Citation2019b), these have largely involved qualitative analysis of a relatively small amount of data. No study has systematically investigated the interpreters’ self-referentiality and institutional identity on a large corpus and explored the discursive effect of the interpreters’ image (re)construction and potential role in contributing to the institution’s hegemony discursively and rhetorically in another language. This makes the topic of the interpreters’ mediation of self-referentiality a productive focus for research.

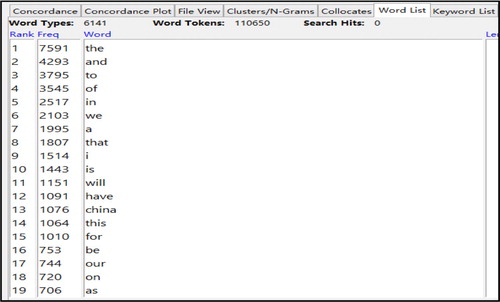

Preliminary analysis of the premier’s press conference data finds that ‘self-referentiality’ is a highly pronounced feature and relevant concept in both Chinese and English. Unsurprisingly, given the one-to-many nature of the discursive event, self-references are constantly used by the Chinese premier in answering the journalists’ questions and addressing the general public. This is evidenced by the fact that self-referential terms such as ‘we’, ‘China’, ‘our’ are amongst the most frequent lexical items in the corpus (see ). Over the past few decades, the Chinese government, led by the Communist party, has played a central role in China’s diplomacy, policies and decision-making. Considering the current one-party system in mainland China, the government, the Communist Party, and China as well as the first-person plural ‘we’Footnote1 can all be deemed synonymous and interchangeable in nature and central to the idea of self-referentiality.

This is why the interpreters’ mediation of the Chinese premiers’ discourse through the category of self-referentiality constitutes an interesting area of investigation. Specifically, we aim to address the following questions:

How and to what extent might the government interpreters (re)construct the Chinese premiers’ political discourse between Chinese and English through mediating self-referentiality at different levels?

Through mediating self-referential items, how might the interpreters serve to strengthen, stabilise or weaken the premiers’ discourse and what image might the interpreters help (re)construct from the perspective of discursive effect?

Self-referentiality, institutional legitimacy and interpreter-mediated press conferences

All social systems, for Luhmann (Citation1990, p. 19), are confronted with the need to form a unique identity and with the ‘imperative to legitimate’ themselves. It is through self-referencing that autonomous or ‘autopoietic’ systems (e.g. institutions and organisations) recursively produce and reproduce elements essential to themselves to continue their existence (e.g. in the form of organisational rules, regulations and policies) (ibid.: 39–40). The concept of autopoiesis or ‘self-making’ derives from Maturana and Varela’s (e.g.Citation1980) work in neuroscience on the regenerating biological cell; it has been increasingly incorporated and adapted by the social and political sciences in the study of social systems, with Luhmann being a prominent exponent. He argues that social systems are reproduced through ‘communications’. In critiquing this emphasis on communications, Eldridge (Citation2002, p. 302) argues that Luhmann’s theory ‘abstracts social processes to the point that individuals, groups and organizations are largely outside the theory’s purview’ and makes the case for humans to have the potential to create autopoietic patterns in their social relations, thereby promoting a behavioural as opposed to communications approach. This line of argument has resonance with the goals of our investigation. The interpreter-mediated press conferences can be viewed as an autopoietic and performative discourse system at an institutional level (see Kidwell, Citation2009). Operationally, the press conferences constitute a closed system (they have their own institutional rules and procedures) that maintain the broader (political) system as a unified entity; however, they can also be described as structurally open due to the presence of domestic and global media outlets and the Chinese premier’s dynamic interactions with the interpreters and journalists.

This interaction, however, is fundamentally based on the maintenance of the system and the consolidation of the government’s own institutional identity. That is, the international media (‘the environment’ in Luhmann’s terminology) can question but it does not necessarily lead the ‘system’ to respond, since the system is concerned only with its own survival. At the press conferences, the interpreters can exert control over the institutional repertoires, regulate the production of political messages to the international media, and discursively re-construct China’s political image in a manner that both echoes the national discursive performance by restating the government as a legitimate political actor (through reproduction of and alignment with the source discourse), and boosting its image by restating and, in some cases, strengthening its discursive and rhetorical acts. The process of interpreting, however, is intimately bound up with the ideological influences on the performative space, which are themselves derived from the political and institutional spheres. Identifying interpreter behaviour therefore requires a critical approach to the complex discursive performances. Given the political and ideological nature of the discursive event and in order to answer the research questions relating to how interpreters might mediate China’s political discourse through using self-referential terms, CDA has been selected as the principal framework in the analysis that follows.

Theoretical framework, corpus data and methodology

Viewing discourse as a form of social practice, CDA is concerned with exposing and making more explicit the otherwise hidden ideologies and latent power asymmetries enacted, legitimised and reproduced in discourse. For CDA practitioners, discourse is both socially shaped and socially constitutive, and has the ability to shape reality and effect change. While there are various schools and traditions, including Fairclough’s (Citation1989) Three-dimensional model, van Dijk’s (Citation2008) Sociocognitive approach, and Ruth Wodak’s (Citation2001) Discourse-Historical Approach, all CDA approaches are united by a shared critical attitude and aim to shed light on the often opaque power and ideology enacted in language use.

To date, CDA has mostly been applied to monolingual texts (e.g. newspapers and political manifestos). Given the mediated nature of the premier’s press conferences, interpreting is conceptualised as a (re)contextualisation process at a macro level, with the interpreter serving as the vital intertextual and interlingual connecting point between the source text (Chinese) and the target text (English). The fact that information is inevitably rendered into the sociopolitical, cultural and linguistic contexts of the TT highlights the micro-level decision-making, stance-taking and potentially ideological mediation that occur in the interpreting process. Such a macro-level conceptualisation permits a critical comparative analysis between the Chinese ST and English TT, focusing on ideologically salient shifts.

Critiques of CDA (e.g. Widdowson, Citation1995) and its frequent recourse to qualitative manual analysis raise important questions of representativeness, objectiveness and validity of the findings. Methods of corpus linguistics (CL) have thus been increasingly incorporated (Baker, Citation2012; Mautner, Citation2009) as a ‘useful methodological synergy’ (Baker et al., Citation2008) in order to reduce researcher bias and lead to more systematic and objective research. This study employs a mixed-methods approach of corpus-based CDA, thus triangulating between the typically qualitative (CDA) and typically quantitative (CL). More detailed discussions on the corpus-based CDA approach can be found in Gu (Citation2018; Citation2019c).

This corpus-based CDA analysis draws on the CE-PolitDisCorp (Chinese-English Political Discourses Corpus) established by the first author for investigating the various aspects of China’s political interpreting and discourses in Chinese and English. It consists of 20 years of China’s Premier-Meets-the-Press conference data (1998–2017). The bilingual corpus contains 310,924 tokens in total (170,260 tokens in Chinese and 140,664 tokens in English). A more detailed breakdown of the corpus data is presented in . On average, one press conference lasts for approximately 2 hours. Since there is one press conference each year, there are, in total, 20 press conferences in the CE-PolitDisCorp, spanning over three latest administrations so far: Jiang-Zhu (1998–2002), Hu-Wen (2003–2012) and Xi-Li (2013–2017). The scope of the corpus data makes it possible to identify consistent and relatively stable patternings over time. Since the main body of the data involves (1) the Chinese premier’s utterances in Chinese (subcorpus A) and (2) their corresponding interpretations into English (subcorpus B), these two components form the focus of this study.

Table 1. Breakdown of the various subcorpora of the CE-PolitDisCorp.

The corpus data was transcribed verbatim from videos available on China’s official websites as well as on video-sharing sites such as YouTube and Youku. The fully prepared data (e.g. after segmentation for Chinese) is analysed using the AntConc software (3.4.4 windows). This specific software contains various functions including concordancing, wordlist generation (lexical frequency), keyword generation, Kwic sorting and tools for studying clusters/N-grams.

Data analysis operates at different levels. Regarding the more detailed procedures, first-person plural pronoun ‘we’ (and its related forms) and other frequently occurring self-referential terms (e.g. ‘China’ and ‘government’) are first identified in subcorpus A (Chinese discourse) and subcorpus B (interpreted English discourse) using AntConc’s Word List tool. The identified self-referential items might be placed into different sub-groups for ease of further analysis (e.g. such items as we, our*, us can be seen as representing a broader group of WE and China/Chinese can be seen as belonging to a broader category of CHINA).

Having established the self-referential items in both subcorpora, the absolute frequencies of identified items are counted individually and then added up in each subcorpus. This allows the overall occurrences of self-referentiality in both subcorpora to be compared on a global level. If the interpreters are found to over-articulate self-referential terms in the English TT, this may constitute an example of repetition (Fairclough, Citation1989) as a result of interpreting. It should be assumed that the more times the various self-referential items are mentioned by the interpreters the stronger the institutional ideology in English and the stronger the interpreters’ alignment with their institutional employer. From the perspective of image, this can (re)create a strong overall image of the government being present and in control. If the contrary is found, there would be a lack of interpreter alignment. That is, the ideological discourse in Chinese is diluted and the government is rendered less prominent as an actor in English. In addition to this macro-level comparison, the data is also explored from a relational and diachronic perspective. Wherever relevant, detailed examples of manual CDA analyses are also provided to illustrate the interpreters’ mediation.

Data analysis: interpreters’ institutional alignment and strengthening of government’s ideological discourse through self-referentiality

Overall level of self-referentiality between the ST and TT

To examine how self-referentiality is rendered by the interpreters, self-referential items were established in both subcorpus A (Chinese) and subcorpus B (English) using AntConc’s Wordlist function and then counted. Self-referential items here are understood to include direct mentions of both China, the ruling party, the Chinese government and key institutions established by the government. Notably, a short phrase might contain more than one self-referential item (e.g. 我们中央政府; literally ‘our central government’). In such relatively rare cases, even though they appear in one short phrase, they were counted separately for the simple reason that our, central and government are all constitutive elements contributing to the idea of self-referentiality. In other words, discursively and ideologically, saying ‘our central government’ (emphasising the presence of ‘we’ and the ‘central’ position of the government at the heart of China’s policies and decisions) is far from the same as just using the seemingly plain ‘the government’ or ‘we’.

Furthermore, the one-to-many nature of the press conferences means that, comparatively speaking, the use of we is stable and homogeneous, referring predominantly to the Chinese government/China represented by the Communist Party. Arguably, even in the few cases involving the anaphoric use of we (e.g. referring to the Chinese and Indian governments), the interpreters are still aligning (partially) with China and the Chinese government they work for. As such, it is unnecessary to further distinguish what we refers to in this particular setting.Footnote2

In limited cases where items (e.g. government) in the corpus might refer to a foreign government (e.g. the Japanese or Indian government), the item (e.g. government) was searched in the respective subcorpus to generate concordance lines. The concordance lines were then re-arranged using the Kwic Sort function (three words to the left or right of the item). The instances that are not self-references of China/the Chinese government can be easily identified and discounted.

The self-referential items identified from the Chinese and English subcorpora are presented in (the items in Chinese and English presented in the same line are rough equivalents and a space is left where there are no direct equivalents). There are 3049 instances of the identified self-referential items in subcorpus A, whereas there are 5679 mentions of the identified items in subcorpus B. That is, the frequency of self-referential items in English is almost double of that in Chinese (a significant 86.3% increase due to interpreting). If a similar level of institutional self-referentiality indicates a general degree of interpreter alignment and maintenance of the government’s presence in the TT, then a marked 86.3% increase constitutes the interpreters’ strong alignment and strengthening of the government’s institutional hegemony. Discursively, the interpreters’ increased (re)production of self-referentiality conveys an image that the government is the chief agent actively involved in different aspects of China’s day-to-day operation.

Table 2. Identified self-referential items in both subcorpora.

More specifically, the top three self-referential items in the Chinese subcorpus are 我们 (literally we, 44.6%), 中国 (literally China, 26.8%) and 政府 (literally government, 12.1%), together accounting for 83.5% of all self-references identified. Similarly, the top three self-referential items in the English subcorpus are the first-person plural WE, that is, we and its related forms (52.6%), CHINA, that is, China and Chinese (24.8%) and GOVERNMENT, that is, government(s) (10.5%), constituting 87.9% of all identified self-referencesFootnote3 in subcorpus B. Apart from their mediation of self-referentiality overall, the interpreters’ increased alignment is also evidenced pronouncedly in their mediation of the top three self-referential items across languages (a marked increase of 119.8%, 72.5% and 61.5% respectively). Given the prominence of WE (we, our*, us), CHINA (China/Chinese) and GOVERNMENT, they will form the focus of discussions here.

The interpreters’ frequent use of these self-referential items is revealing discursively. The first-person plural pronouns (we, us, our*), for example, are indicative of the interpreters’ positioning and in-group identity (Van Dijk, Citation1984). Also, the interpreters’ proliferated use of Chin* and government(s) clearly delineates the geographic context of China and specifies that the Chinese government is the chief social actor behind China’s policies and actions. Example 1 illustrates the interpreter’s increased alignment at a micro level through the vigorous (re)production of various self-referential items in English (a scenario that is reflective of the overall picture in the CE-PolitDisCorp).

Example 1 (2016)

ST: 所以政府下决心要推进全国医保联网。今年要在基本解决省内就医异地能够直接结算这个基础上,争取能够用两年时间[…]使合情合理的异地结算问题能够不再成为群众的痛点。当然,这需要我们各有关部门下大力气。我们执政的目的为什么? 落脚点还是为了改善民生,就是要让群众对民生的呼声要求,来倒逼我们的发展,推动和检验我们的改革。

Gloss: So the government is determined to push ahead with the national portability of medical insurance. This year will, on the basis that direct settlement of expenses at a provincial level can basically be resolved, strive to use two years’ time to[…]make reasonable and legitimate out-of-town payment issue no longer a point of pain for the masses. Of course, this requires all of our relevant departments to make great efforts. The purpose of our administration is for what? The departure point still is to improve people’s livelihood, that is, to let the masses’ demand for well-being reversely drive our development, push and test our reform.

TT: So the Chinese government is fully determined to achieve national portability of medical insurance schemes at a faster pace. This year we will basically achieve the direct settlement of such expenses at the provincial level. And we also plan to use two years of time to[…]remove this high concern on the minds of our people. And this requires that all relevant government departments to make tremendous efforts. All the government's work is to improve the well-being of our people. So we need to use the concrete wishes for a better life by our people to drive our development, and reform and test the results of our reform.

In this example extracted from the 2016 conference, the overall message has been relatively accurately rendered. However, there are a number of salient signs indicative of the interpreter’s institutional alignment. In terms of self-referentiality, a considerably stronger presence of the Chinese government can be found in the TT vis-à-vis the ST. As marked in bold, while there are 5 instances of self-references in the ST (government, our, our, our and our), 12 instances were identified in the English TT (more than twice the number in ST). Notably, none of the additions was triggered by the ST or the grammatical differences between the two languages.

More specifically, self-referential items such as Chinese and government have been added to specify that it is the ‘Chinese’ government that is determined and all relevant ‘government’ departments are to make tremendous efforts. In addition, a very noticeable collocational pattern ‘our people’ can be detected in the TT. That is, 群众 (the masses), 民生 (people’s livelihood) and 群众 (the masses) have all been rendered into English as ‘our people’ with the addition our (three instances in this short extract alone). Discursively, the interpreter’s repeated use of ‘our people’ indicates a relationship of ‘belonging’, re-confirming the reality that the people are under the leadership of the Chinese government and the Communist party (of which the interpreter is a core member). Cumulatively, such active engagement (re)creates a positive image of the government being committed to serving the people over the 20 years’ data.

This trend is also visible in the following examples. The pervasive additions of self-referential items (e.g. we, our, government, central, China) in the English discourse have shown the interpreters’ institutional alignment, which have (re)constructed a more favourable image of the government being competent and actively involved in various aspects of China’s developments (e.g. economic growth and modernisation).

Example 2 (2011)

ST: 我们要把转变经济增长方式作为主线,真正使中国的经济转到主要依靠科技进步和提高劳动者素质上来,着重提高经济的增长的质量和效益。

Gloss: We’ll take the transformation of economic growth pattern as the main focus to really make China’s economy shift towards one that mostly relies on technological progress and improvement of labour force quality, emphasising on raising the quality and efficiency of economic growth.

TT: We’ll take the transformation of China’s economic development pattern as our priority task so that we will be able to refocus China’s economic development to scientific and technological advances and to higher educational level of the labour force. And we will be able to in that way raise the quality and efficiency of China’s economic development.

Example 3 (2012)

ST: 建国以来,在党和政府的领导下,我国的现代化建设事业取得了巨大的成就。

Gloss: Since the country’s founding, under the leadership of the party and government, our country’s cause of modernisation construction yielded tremendous achievements.

TT: Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, under the leadership of our party and the central government, remarkable achievements have been made in advancing our modernisation drive.

Chinese government/we as the chief actor (subject/theme position) in interpreted English discourse

Beyond the interpreters’ general alignment to reinforce Beijing’s institutional hegemony, it is useful to pinpoint the position where these items appear in sentences/clauses. The SFL concepts of theme/rheme are relevant here. Themes, as ‘discourse-initiating units’ (Halliday, Citation2004, p. 89), occupy the first position and form the point of departure for clauses, which are followed and commented on by rhemes. For Halliday (Citation2004), elements in the thematic position draw more readers/listeners’ attention than elements in the rhematic position. This is echoed by Baker (Citation2018), who believes that the overall choice and ordering of themes plays an important part in organising a text and providing a point of orientation for a given stretch of language. She argues further that the cumulative effect of thematic choice should not be underestimated in translation. The choice of theme therefore can be a way of linguistic engineering in interpreting, which is of interest from the perspective of ideology and discourse. Chinese and English follow a similar SVO (subject + verb + object) structure, thus making the two languages comparable overall regarding theme/rheme.

Notably, themes and subjects often have considerable overlap as themes typically are subjects in both languages (unmarked theme). Exceptions, however, do exist, where themes are not the subjects (marked theme). An example of this is ‘over the past four years, this government (subject) has achieved a lot’. Given the nature of the project, the identification and comparison of what appears in the subject position as the actual agent or initiator behind the various actions is more relevant and ideologically interesting than simply what comes first in a sentence or clause. Therefore, attention is focused on the instances of major self-referential items occupying the subject position here. As such, the top three self-referential terms in Chinese and English were searched in both subcorpora. The retrieved concordance lines were further sorted to facilitate the researcher’s observation. The self-referential items are found to largely assume preeminent positions as the subjects of sentences/clauses in both subcorpora.

Statistically, 我们 occupies the subject position in the Chinese clauses/sentences 1157 times, out of 1360 mentions of 我们 in the Chinese subcorpus. In comparison, we assumes the subject position in English 2013 times, out of 2989 instances of the broader WE (we, us, our*) identified. Similarly, 政府 occupies the subject position 223 times in Chinese, whereas government occupies the subject position 326 times in English. This same trend is also found in the comparison between 中国 and China. Therefore, self-referential items tend to be rendered significantly more explicit as subjects in English, thus further foregrounding the Chinese government discursively as the social actor and agent responsible for various actions in interpreting. This is aptly illustrated in Example 4, where the Chinese ‘government’ becomes the subject/theme in the English interpretation (rather than ‘the government’s work’).

Example 4 (2007)

ST: 政府工作走过了四个年头,它告诉我们必须懂得一个真理 …

Gloss: The government’s work has gone through four years. It told us that must understand one truth …

TT: This government has been serving the people for four years. The four years of government work has taught me three things …

This and the interpreter’s employment of the present perfect continuous structure highlight the vital role of the Chinese government as the chief actor in ‘serving the people’. This also serves to (re)construct an emphatic people-oriented image of Beijing in English in front of the international audience. The tendency for self-referential items to be rendered more prominent and assume the subject/theme position in English is also visible in the following examples (which also illustrate the general tendency for the interpreters to add self-referential items as discussed earlier). Notably, the Chinese ST is sometimes even further strengthened through other discursive means, such as an upgrade in modality value (example 5).

Example 5 (2016)

ST: 所以简政放权必须一以贯之。哪里遇到问题碰到阻力就要设法去解决。

Gloss: So the streamlining of administration and delegation of power must be consistent. Where problems are met and resistance is encountered, efforts need to be made to solve them.

TT: We must make persistent efforts to forge ahead with this government reform and wherever there is an obstacle to this reform, the government must get right on it.

Example 6 (2011)

ST: 而做到所有这一些,都必须推进经济体制改革和政治体制改革。

Gloss: To achieve all these, economic system reform and political system reform must be pushed forward.

TT: If we are to achieve all these above-mentioned goals, we must pursue economic restructuring and political restructuring.

In sum, a comparison of the self-referential terms between subcorpus A and B points to the interpreters’ significantly increased alignment with the Chinese government. This is salient discursively on many levels. Firstly, the interpreters’ repeated additions of self-referential items demonstrate their in-group identity (Van Dijk, Citation1984) institutionally as part of China’s ruling elite. Going beyond being merely indicative of interpreters’ institutional identity, the perceived tendency also strengthens the centripetal force and ‘unitary language’ (Beaton, Citation2007, p. 279) of the specific institution, leading to increased presence and hegemony of the government overall. It also helps (re)create an image of the government being an active and committed actor in charge of China’s day-to-day running in English. This seems salient in our increasingly mediat(is)ed world, where the English interpretation is often taken for granted and appears almost verbatim on various platforms (e.g. media and government websites). As illustrated in , the discourse featuring the interpreter’s additions of self-referential items (evidenced in Example 5) is presented on the website of China’s English-language newspaper China Daily as a transcript of the 2016 press conference. This highlights the discursive ramifications of interpreting beyond the immediate press conference setting.

Interpreters’ negotiation of self-referentiality from a relational perspective

Having examined the interpreters’ mediation of self-referential items directionally between the ST and TT, their alignment is now approached from a relational perspective. This makes it possible to see how China’s official institutional voice is negotiated by the interpreters, that is, the relative foregrounding and/or backgroundingFootnote4 of certain self-referential items over others through interpreting.

Given the prominence of the first-person plural pronouns (we, our*, us) in the CE-PolitDisCorp, attention was focused on the relationships between the collective WE and the premier’s personal voice I, WE and CHINA as well as WE and GOVERNMENT.

Collective WE vis-à-vis personal I

To explore the relational nexus between the government’s collective voice WE and the Chinese premier’s personal voice I as a result of interpreting, personal pronouns 我们 and 我 were searched in subcorpus A. Similarly, personal pronouns related to WE (we, our*, us) and I (I, my, mine, me, myself) were searched in subcorpus B. Information regarding the frequencies of these personal pronouns and the WE/I ratios in both subcorpora is presented in . Statistically, the WE/I ratios for subcorpora A and B are 1.025 and 1.51. That is, for every 1000 mentions of the broader I, there are 1025 and 1510 mentions of the broader WE in Chinese and English. This points to a significant (relative) foregrounding of the ideological presence of a collective WE in English proportionately at the expense of the premier’s personal voice. This is achieved through the interpreters’ proportionally stronger alignment with the collective WE (presumably the voice of China and, by extension, the voice of the Chinese nation and civilisation led by the Communist party and government).

Table 3. Broader WE and broader I in both subcorpora

Collective WE vis-à-vis GOVERNMENT and CHINA

Similarly, the relational links between the collective WE (we, us, our*), GOVERNMENT and CHINA (China and Chinese) are discussed here. Firstly, the WE/GOVERNMENT ratios were calculated in both subcorpora. Statistically, the WE/GOVERNMENT ratios are 3.686 and 5.015 in subcorpus A and B. That is, for 1,000 mentions of GOVERNMENT, there are 3,686 and 5,015 mentions of the broader WE in Chinese and English respectively. While there is a (dramatically) increased presence of government in the TT in absolute terms (a 61.5% increase over the ST, which is in itself significant), the interpreters, comparatively, are more inclined to use we and its related forms in the TT, hence a relative backgrounding of the more specific notion ‘government’. Similarly, the WE/CHINA ratios were calculated in both subcorpora. Statistically, the WE/CHINA ratios are 1.663 and 2.118 (for 1,000 mentions of China/Chinese there are 1,663 and 2,118 mentions of the broader WE in the ST and TT). As such, while items subsumed under WE and CHINA were both statistically (over)produced in the TT in absolute terms, the broader CHINA has been comparatively backgrounded in interpreting.

While the various lexical items subsumed under the broader WE (we, us, our*) apparently refer to the government and China, WE is arguably an embodied and subtle concept in the unique Chinese context. According to the guiding ‘Three Represents’ Thought that was written into the Constitution, the Communist Party of China (CPC) must always represent the development trend of China’s advanced productive forces, the orientation of China’s advanced culture, and the fundamental interests of the overwhelming majority of the Chinese people. As such, the broader WE in the Chinese context represents not just the Communist party, the government, and China as a political entity but also the entire Chinese nation and civilisation by extension. Discursively, the first-person plural we and its related forms are more engaging and evocative in nature than the more specific item government (consider, for example, ‘yes, we can’, ‘we’ve got it covered’, ‘come fly with us’ in commercial and political language use).

Rather than dichotomising China, the government and, for instance, the people, the interpreters’ proliferated use and relative foregrounding of the collective WE (we, us, our*) foster a sense of ‘collective intentionality’, which represents ‘a sense of doing (wanting, believing, etc.) something together’ (Searle, Citation1995, p. 24–25). This strengthened sense of togetherness highlights the inseparable nature of the will/achievements of the government and the people. Put differently, the relative foregrounding of WE indicates that, although the Chinese government under the CPC is the predominant social actor, ‘we’ are together in China’s progress en route to the realisation of its various goals. As such, discursively and cognitively, the interpreters’ foregrounding of the collective WE has consolidated the leadership of the CPC, thereby strengthening the hegemonic discourse that WE led by the CPC represents the collective voice of the Chinese people as well as the Chinese nation and civilisation.

A diachronic analysis of the broader WE across administrations

For a deeper understanding of interpreters’ alignment, the broader WE was investigated further from a diachronic perspective. The 20 years’ press conference data can be divided into three administrations: Premier Zhu (1998–2002), Premier Wen (2003–2012) and Premier Li (2013–2017). In each period, 我们 and its English equivalent WE (we, our* and us) were searched in both subcorpora. Mentions of the items in each period were counted and adjusted based on average annual frequency for comparison diachronically ().

Table 4. Frequencies of the broader WE across administrations

While there is roughly a similar number of 我们 in the ST during each administration each year (65.4, 64.6 and 77.4 respectively), the interpreters have shown increased alignment with the premier’s articulation of the first-person plural 我们in each period (a 50.8%, 151.4% and 125.3% increase respectively). In particular, there is a dramatic surge in the interpreters’ first-person plural pronoun use in the TT, with premier Wen’s administration being a pronounced watershed. The sudden spike in interpreters’ alignment witnessed in this administration became relatively stabilised and continued into his successor, premier Li’s administration.

Interestingly, the analysis by Wu and Zhao (Citation2016) focusing on the aggressiveness of Chinese premiers’ answers in Chinese also identifies the administration starting from 2003 as an important ‘watershed’. Since 2003, the adversarialness of the premiers’ answers has decreased significantly, which for them might have to do with the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) crisis that broke out in China that year. The previous tendency to downplay negative news and release information inefficiently gave way to a more transparent and less aggressive approach in government-journalist ties (Liang & Xue, Citation2004). This suggests that the Hu-Wen administration adopted a comparatively more open style of governance featuring active engagement (at least evidenced in these press conferences). This perceived trend of engagement was further facilitated by the interpreters through their increased institutional alignment since 2003. As such, the decrease in adversarialness of the premiers’ answers has, to some extent, been compensated by the interpreters’ more pronounced and active positioning using WE (which leads to further government hegemony and a sense of togetherness).

Discussion and conclusion

Benefitting from CDA analysis based on a large corpus, this article has investigated the interpreters’ mediation of self-referentiality from various angles in order to identify the mechanisms of system reproduction as framed by Luhmann. Although the elements central to system reproduction are commonly understood to take the form of institutional rules and policies, this study shows the significance of considering the conferences as a performative space and the need for a critical approach to the complex discursive performances to help index interpreter behaviour and its impact on system reproduction.

In absolute terms, there is markedly increased (re)production of self-referentiality in English (86.3%). Such active interpreter alignment significantly strengthens the government’s ideological presence and institutional hegemony, (re)creating an overall image of Beijing being responsible and in control cumulatively over the 20 years. Given that in the Chinese context the Chinese government is the dominant actor and agent responsible for different aspects of China’s reforms, development and day-to-day running, this leads to further government legitimacy and (re)constructs a stronger degree of its raison d'être in front of the global audience.

In addition, an examination of the specific position of the top-three self-referential items in both subcorpora shows that these items tend to more frequently occupy the subject position in clauses and sentences in English. As such, the Chinese government is rendered more prominent as the chief social actor responsible for a range of actions.

Relationally, the broader WE (we, our*, us) proves to be a salient choice adopted by the government-affiliated interpreters. Proportionately, its frequent use is employed at the expense of the premier’s personal voice I, and seems to have backgrounded the presence of GOVERNMENT and CHINA relatively speaking. The frequent use of the first-person plural we and its related forms indicates the interpreters’ positioning as part of the government and helps (re)construct ‘collective intentionality’ (Searle, Citation1995, pp. 24–25). Further diachronic investigation of the broader WE demonstrates that the interpreters tend to actively (re)produce the we-related items in each administration. This, however, is most pronounced during premier Wen’s administration (2003–2012), a period featuring a softer approach. To some extent, the sharp drop in the adversarialness and ideological force of the premier’s answers in this period seems to have been offset by a strengthening in the government’s institutional hegemony due to the interpreters’ increased alignment.

Admittedly, given the consecutive interpreting mode and the pressure these interpreters are under, the additions of we and its related forms might be a coping strategy and a relatively safe option. Further research triangulating performance data with retrospective interpreter interviews would support investigation of this aspect and others, such as the extent to which such strategies constitute conscious explicitation for the target audience. From a product-oriented perspective, however, the proliferated use and relative foregrounding of WE (vis-à-vis GOVERNMENT and CHINA) is significant discursively. This not only indicates the interpreters’ institutional identity but also enhances the government’s hegemony in English in a less noticeable yet cumulative manner, thereby reflecting Fairclough’s observation that ideology is often most effective when its workings are least visible (1989).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Dr Chonglong Gu is lecturer in Chinese Translation Studies and programme director of MA in Chinese-English Translation and Interpreting at the University of Liverpool. He holds an MA in Conference Interpreting and Translation Studies (Leeds University) and a PhD in Interpreting Studies (Manchester University). His research has been published in Target, The Translator, Perspectives, Discourse, Context and Media, Critical Discourse Studies, Translation and Interpreting Studies and book chapters.

Rebecca Tipton PhD is a Lecturer in Interpreting and Translation Studies based in the Centre for Translation and Intercultural Studies (CTIS) at the University of Manchester. She has published on interpreting in asylum settings, conflict zones, police interviews, and in social work. More recent work has investigated the provision of multilingual victim support services in statutory and third sector organisations in the contemporary period and she is currently developing a history of public service interpreting in Britain. Her publications include Dialogue Interpreting: A guide to interpreting in public services and the community (2016) co-edited with O. Furmanek, and The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Pragmatics (2019) co-edited with L. Desilla.

ORCID

Chonglong Gu http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5286-5263

Rebecca Tipton http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6974-8226

Notes

1 Even in cases of anaphoric or inclusive use of ‘we’ (referring, for instance, to China/Chinese government and a foreign country/government mentioned earlier) the interpreters arguably are still (partially) aligning themselves with Beijing as representatives of the Department of Foreign Affairs and China’s ruling elite.

2 This scenario is different from, for instance, the UK parliamentary debate or debate in the EU setting as in Beaton-Thome’s (Citation2010) study, in which she identifies that ‘we’ can be used exclusively or inclusively by MEPs to refer to the countries they represent or the EU institution as a whole.

3 Further analysis illustrates the often interconnected nature of the various self-referential items, where the first-person plural we and its various forms, government, Communist Party, China/Chinese are sometimes juxtaposed with each other. This is evidenced in the following appositions (e.g. ‘we as government’ [three times in 2004], ‘we as a nation’ [2005] and ‘we the Chinese nation’ [2007]) and the juxtaposition of various self-referential terms (e.g. [our] party and [our] country, [our/the] party and [the] [central] government, whole party and all the Chinese people, our government, Chinese government). The interwoven and mutually enhancing nature of these items is unsurprising, given the current one-party rule in mainland China, where the CPC represents both the ruling party, the government and China.

4 Discussions on foregrounding and backgrounding can be found in Fairclough (Citation1995). In this corpus-based study, however, foregrounding and backgrounding refer to the frequency shift of a certain item as a result of interpreting. In other words, if certain items are featured more (or less) prominently in the TT, they are relatively foregrounded (or backgrounded). This is of interest from the perspective of the interpreters’ ideological mediation.

References

- Baker, M. (2018). In other words: A coursebook on translation (3rd ed). Abingdon & New York: Routledge.

- Baker, P. (2012). Acceptable bias? Using corpus linguistics methods with critical discourse analysis. Critical Discourse Studies, 9(3), 247–256. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2012.688297

- Baker, P., Gabrielatos, C., KhosraviNik, M., Krzyzanowski, M., McEnery, T., & Wodak, R. (2008). A useful methodological synergy? Combining critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics to examine discourses of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press. Discourse & Society, 19(3), 273–306. doi: 10.1177/0957926508088962

- Beaton, M. (2007). Interpreted ideologies in institutional discourse: The case of the European Parliament. The Translator, 13(2), 271–296. doi: 10.1080/13556509.2007.10799241

- Beaton-Thome, M. (2010). Negotiating Identities in the European Parliament: The role of simultaneous interpreting. In M. Baker, M. Olohan, & M. C. Perez (Eds.), Text and context: Essays on translation and interpreting in Honour of Ian Mason (pp. 117–138). Manchester: St. Jerome.

- Beaton-Thome, M. (2013). What’s in a word? your enemy combatant is my refugee: The role of simultaneous interpreters in negotiating the lexis of Guantánamo in the European Parliament. Journal of Language and Politics, 12(3), 378–399. doi: 10.1075/jlp.12.3.04bea

- Diriker, E. (2004). De-/re-contextualizing conference interpreting: Interpreters in the ivory tower? Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing.

- Eldridge, D. (2002). The construction of a courtroom. The judicial system and autopoiesis. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 38(3), 298–316. doi: 10.1177/0021886302038003003

- Fairclough, N. (1989). Language and power. London & New York: Longman.

- Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language. London: Longman.

- Goffman, E. (1981). Forms of Talk. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Gu, C. (2018). Forging a Glorious past via the ‘present perfect’: A corpus-based CDA analysis of China’s past Accomplishments discourse mediat(is)ed at China’s interpreted political press conferences. Discourse, Context and Media, 24, 137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.dcm.2018.03.007

- Gu, C. (2019a). Mediating ‘face’ in Triadic political Communication: A CDA analysis of press conference interpreters’ discursive (Re)construction of Chinese government’s image (1998–2017). Critical Discourse Studies, 16(2), 201–221. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2018.1538890

- Gu, C. (2019b). Interpreters caught up in an ideological Tug-of-war?: A CDA and Bakhtinian analysis of interpreters’ ideological positioning and alignment at government press conferences. Translation and Interpreting Studies, 14(1), 1–20. doi: 10.1075/tis.00027.gu

- Gu, C. (2019c). (Re)manufacturing consent in English: A corpus-based critical discourse analysis of government interpreters’ mediation of China’s discourse on PEOPLE at televised political press conferences. Target, 31(3), 465–499. doi: 10.1075/target.18023.gu

- Halliday, M. A. K. (2004). An introduction to functional grammar (3rd ed.). London: Arnold.

- Kidwell, K. S. (2009). Politics, performativity, autopoiesis: Toward a discourse systems theory of political culture. Cultural Studies – Critical Methodologies, 9(4), 533–558. doi: 10.1177/1532708608321403

- Koskinen, K. (2014). Institutional translation: The art of government by translation. Perspectives, 22(4), 479–492. doi: 10.1080/0907676X.2014.948887

- Lambropoulou, E. (1995). The autopoietic view of prison organization and of correctional reforms. In K. Ellis, A. Gregory, B. R. Mears-Young, & G. Ragsdell (Eds.), Critical issues in systems theory and practice (pp. 693–696). New York: Springer.

- Li, X. (2018). Reconstruction of modality in Chinese-English government press conference interpreting: A corpus-based study. Singapore: Springer.

- Liang, H., & Xue, Y. (2004). Investigating public health emergency response information system Initiatives in China. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 73(9), 675–685. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2004.05.010

- Luhmann, N. (1990). Political theory and the welfare state. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Mason, I. (1999). ‘Introduction’, in Ian Mason (ed.) Dialogue Interpreting, Special Issue of The Translator 5(2): 147–160.

- Maturana, H., & Varela, F. (1980). Autopoiesis and cognition: The realization of the living. Dordrecht, Boston, London: Reidel.

- Mautner, G. (2009). Corpora and critical discourse analysis. In P. Baker (Ed.), Contemporary corpus linguistics (pp. 32–46). London: Continuum.

- Sacks, H. (1992). Lectures on conversation. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Searle, J. (1995). The construction of social reality. New York: Free Press.

- Sun, T. (2012). Interpreters’ mediation of government press conferences in China: Participation framework, footing and face work. Unpublished PhD thesis. Manchester: University of Manchester.

- Van Dijk, T. A. (1984). Prejudice in discourse. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Van Dijk, T. A. (2008). Discourse and context: A sociocognitive approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wadensjö, C. (1998). Interpreting as interaction. London & New York: Longman.

- Wang, B., & Feng, D. (2018). A corpus-based study of stance-taking as seen from critical points in interpreted political discourse. Perspectives, 26(2), 246–260. doi: 10.1080/0907676X.2017.1395468

- Widdowson, H. G. (1995). Discourse analysis: A critical view. Language and Literature, 4(3), 157–172. doi: 10.1177/096394709500400301

- Wodak, R. (2001). The discourse-historical approach. In R. Wodak & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of critical discourse analysis (pp. 63–95). London: Sage.

- Wu, F., & Zhao, H. (2016). How to respond to journalists’ questions? A new perspective on Chinese premiers’ aggressiveness at press conferences (1993–2015). Asian Journal of Communication, 26(5), 446–465. doi: 10.1080/01292986.2016.1192210