ABSTRACT

Purpose

To describe a case of cocaine-induced midline destructive lesions (CIMDL) associated with ocular autoimmune disease.Methods: Observational case report.

Results

A 45-year-old man with history of chronic osteolytic sinusitis due to cocaine abuse presented with sudden vision loss in right eye. Ophthalmic examination revealed fixed right mydriasis with extraocular movements limitation and optic disc swelling. Computed tomography showed an orbital infiltrating mass. The diagnosis of orbital-apex syndrome secondary to CIMDL was established. Steroids and antibiotics therapy were started without vision improvement. At 6-months follow-up, a corneal ulcer with characteristics of peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK) was evidenced, coinciding with an upper respiratory bacterial infection.

Conclusions

CIMDL and PUK share common pathogenic pathways, with implication of autoimmune factors and exposure to infective antigens. We hypothesized that chronic cocaine use, along with persistent bacterial infection, could have triggered an inflammatory reaction, which contributed to CIMDL development and the appearance of PUK.

Cocaine use disorder represents a major public health concern. Intranasal route is the most common form of administration and may produce diverse pharmacological effects.Citation1 Ophthalmic adverse effects are rare, but cases of ocular surface damage, retinal vasculopathy, nasolacrimal obstruction, and orbital inflammation have been described.Citation2–4 Cocaine-induced midline destructive lesions (CIMDL) is a rare syndrome characterized by osseocartilaginous destruction of nose, sinuses and palate structures, and has been related with autoimmune factors.Citation5 Herein we report a case of orbital apex syndrome, derived from CIMDL, associated with peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK).

Case report

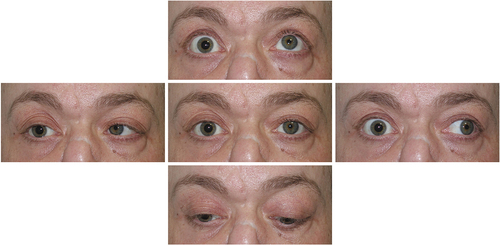

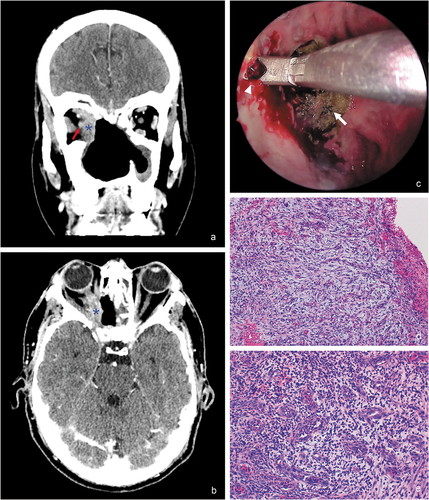

A 45-year-old man presented with sudden vision loss in the right eye (OD), periocular pain, and purulent rhinorrhea. The patient had past history of cocaine abuse with chronic sinusopathy and septum destruction, subjected to multiple maxillofacial surgical interventions. Visual acuity (VA) in OD was hand motion. Ophthalmic examination revealed fixed right mydriasis with limitation in right ocular-motility () and a swollen optic disc. Computed tomography scan showed a large midline bony defect and an infiltrating mass extending into the right inferomedial orbit and apex (). The patient was admitted to hospital and was treated empirically with intravenous methylprednisolone and broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics. Laboratory test, including complete blood count, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (cANCA), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) were within normal limits. Serological tests for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis virus, and syphilis were negative. Culture from nasopharyngeal exudate detected gram-positive cocci. Endoscopic transnasal approach with neuro-navigation system facilitated a biopsy of the right medial orbital wall (). The histopathologic study showed necrotizing changes, focal abscessification, and chronic inflammation (), but it did not exhibit necrotizing granulomas, typical of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and fungal infection or mitotic figures were not identified. Drug tests were conducted with negative result and confirmed drug abstinence. The diagnosis of orbital apex syndrome secondary to cocaine abuse associated with upper respiratory tract infection was established. After tapering oral prednisone regimen and systemic antibiotic therapy, both right periorbital pain and rhinorrhea improved, but extraocular movements limitation and visual impairment persisted.

Figure 1. Motility examination reveals orthotropia in primary gaze, marked limitation in adduction, abduction, supraduction, and less in infraduction, as well as a non-reactive mydriasis of the right eye.

Figure 2. (a,b) Computed tomography scan ((a) coronal plane, (b) axial plane) shows a large midline bony defect and an infiltrating mass (blue asterisk) extending into the right inferomedial orbit and apex. It is possible to appreciate the proximity of the soft-tissue mass to the right optic nerve (red arrow). (c) Endoscopic transnasal approach for biopsy using image-guided neuro-navigation system that exhibits friable granulation tissue at the right medial orbital wall (white arrowhead), and patchy areas of necrotic tissue (white arrow). (d) Partially necrotized tissue, composed primarily of granulation tissue (hematoxylin-eosin, 100x). (e) Small vessels and fibroblastic proliferation with prominent lymphocytic and neutrophilic inflammation (hematoxylin-eosin, 200x).

Two months later, the patient reported once again right periocular pain and purulent rhinorrhea. The VA in OD worsened to light perception. The magnetic resonance imaging ruled out a cavernous sinus thrombosis, but demonstrated an enlargement of the orbital mass. Multiple biopsies from the right medial wall and periorbita were obtained once again, showing chronic inflammation, and confirmed one more time no evidence of GPA, malignancy, or fungal infection.

The patient remained stable for 6 months with close follow-up by both ophthalmology and otorhinolaryngology departments. However, in a periodic review, the patient presented with painless right red eye. Slit-lamp examination revealed a non-painful crescent-shaped corneal infiltrate with epithelial defect located at the inferior corneal pole (). Corneal sensitivity test with the tip of a cotton swab demonstrated right corneal hypoesthesia. The Schirmer’s test revealed 5 mm of Whatmann’s strip wetting in the OD and 15 mm in the left eye. Initially, a neurotrophic component was suspected and treatment with lubricant eye drops was started. Coinciding with corneal involvement, the patient was admitted for a Pseudomonas aeruginosa respiratory tract infection. Over the following days, corneal ulcer showed rapid enlargement with increasing corneal melting. Due to the concomitant corneal involvement with the systemic infectious process, corneal scraping was performed in order to rule out viral or bacterial etiologies. Microbial growth was not observed, but presence of leucocytes was detected. We considered the diagnosis of PUK, and a tapering regimen of oral steroids was initiated with highly significant improvement (), even if decreased corneal sensation persisted.

Discussion

CIMDL is a rare complication of cocaine nasal inhalation and its prognosis is usually poor. Some conditions such as infections, lymphoid or hematological tumors, and immunological diseases like GPA may mimic CIMDL. These entities are potentially life-threatening, and could be misdiagnosed in patients with history of long-term intranasal cocaine use.Citation6

Inhaled cocaine may provoke necrosis of cartilage and mucosa, as well as impairment of the physiological defense mechanisms inside the nasal cavity, leading to chronic bacterial carriage and contributing to CIMDL development. Bacterial superinfection has been documented in patients with CIMDL, and could produce an enhancement of the inflammatory process, in spite of drug abstinence, as occurred in our patient.Citation7–9

Infrequently, CIMDL expansion may result in orbital invasion leading to an orbital apex syndrome.Citation10 It is a complex clinical disorder featuring visual loss from optic neuropathy and ophthalmoplegia, affecting multiple cranial nerves. There are few reports of orbital apex syndrome associated with intranasal cocaine abuse,Citation11,Citation12 and we therefore considered the inclusion of CIMDL as part of the differential diagnosis. The distinction with cavernous sinus syndrome might be challenging, and the main differentiator can be the presence of neuropathy in orbital apex syndrome.Citation13 Indeed, the exact mechanisms of optic nerve damage remain unclear, but a combination of compressive, infiltrative and ischemic pathways have been proposed.Citation9,Citation10,Citation12

On the other hand, we hypothesized that corneal hypoesthesia would also be a complication of orbital apex syndrome. Impairment of trigeminal corneal innervation at any point of its course may lead to decrease of corneal sensation and subsequent neurotrophic keratitis (NK).Citation14,Citation15 In our patient, we initially considered the diagnosis of NK due to the result of corneal sensitivity test. The relevant right shortening of Schirmer test would also suggest a reduced corneal sensation, as the lacrimal gland function is influenced by sensory nerves. Nonetheless, the morphologic features of the corneal ulcer with presence of leucocytes, and the appropriate response to corticosteroids therapy, led us to the diagnosis of PUK.

PUK is a form of ocular inflammation that involves the outer portions of the cornea and it is frequently associated with systemic conditions, like ANCA-associated vasculitides.Citation16,Citation17 It is known that the peripheral cornea holds anatomic and physiologic characteristics that predispose it to inflammatory reactions with immune complexes deposition.Citation18,Citation19 In this way, ANCA formation with stimulation of cytokines and collagenases release can contribute to keratolysis.Citation20,Citation21 Furthermore, hypersensitivity reaction against exogenous triggers, like bacterial antigens, could also have an influence on corneal stromal inflammation,Citation16,Citation22,Citation23 which would be consistent with the concomitant bacterial infection presented by our patient.

Interestingly, it is increasingly recognized that cocaine and levamisole, a common adulterant of cocaine, have been implicated as triggering factors of ANCA development with multiorgan involvement.Citation24–26 The perinuclear staining pattern of ANCA (pANCA) predominates in CIMDL, whereas the cytoplasmic pattern (cANCA) is more frequent in GPA. The prevailing pANCA type is directed against human neutrophil elastase (HNE), and it is not frequently detected in other autoimmune diseases, so it can be used to distinguish CIMDL between other entities.Citation27–29 Unfortunately, our center did not have access to the HNE assay, which is not broadly available.

At this point, it is interesting to highlight the study conducted by Trimarchi et al., which suggested that CIMDL seems to be the result of an inflammatory tissue response triggered by cocaine use, with the participation of infective agents, in patients predisposed to autoimmunity.Citation30 These findings could explain the low prevalence of CIMDL among cocaine users, and its previously reported association with other immune diseases.Citation31,Citation32

For all these reasons, we hypothesized that chronic cocaine use, along with persistent bacterial infection, could have triggered an inflammatory reaction, which contributed to CIMDL development and the appearance of PUK.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of orbital apex syndrome with optic neuropathy and corneal hypoesthesia in the presence of CIMDL, complicated with an ocular autoimmune condition.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

References

- White SM, Lambe CJT. The pathophysiology of cocaine abuse. J Clin Forensic Med. 2003;10:27–39. doi:10.1016/S1353-1131(03)00003-8.

- Mantelli F, Sacchetti M, Lambiase A, Bonini S. Neurotrophic keratitis induced by cocaine snorting. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(13):1458.

- Kannan B, Balaji V, Kummararaj S, Govindarajan K. Cilioretinal artery occlusion following intranasal cocaine insufflations. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011;59:388. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.83619.

- Alexandrakis G, Tse DT, Rosa RH, Johnson TE. Nasolacrimal duct obstruction and orbital cellulitis associated with chronic intranasal cocaine abuse. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:1617. doi:10.1001/archopht.117.12.1617.

- Trimarchi M, Bertazzoni G, Bussi M. Cocaine induced midline destructive lesions. Rhinology. 2014;52:104–111. doi:10.4193/Rhino13.112.

- Trimarchi M, Gregorini G, Facchetti F. et al. Cocaine-induced midline destructive lesions: clinical, radiographic, histopathologic, and serologic features and their differentiation from Wegener granulomatosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001;80:391–404. doi:10.1097/00005792-200111000-00005.

- Smith JC, Kacker A, Anand VK. Midline nasal and hard palate destruction in cocaine abusers and cocaine’s role in rhinologic practice. Ear, Nose Throat J. 2002;81:172–177. doi:10.1177/014556130208100313.

- Armengot M, García-Lliberós A, Gómez MJ, Navarro A, Martorell A. Sinonasal involvement in systemic vasculitides and cocaine-induced midline destructive lesions: diagnostic controversies. Allergy Rhinol. 2013;4:ar.2013.4.0051. doi:10.2500/ar.2013.4.0051.

- Goldberg RA, Weisman JS, McFarland JE, Krauss HR, Hepler RS, Shorr N. Orbital inflammation and optic neuropathies associated with chronic sinusitis of intranasal cocaine abuse. Possible role of contiguous inflammation. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107:831. doi:10.1001/archopht.1989.01070010853028.

- Shen CC, Silver AL, O’Donnell TJ, Fleming JC, Karcioglu ZA. Optic neuropathy caused by naso-orbital mass in chronic intranasal cocaine abuse. J Neuro-Ophthalmol. 2009;29:50–53. doi:10.1097/WNO.0b013e3181989adb.

- Siemerink MJ, Freling NJM, Saeed P. Chronic orbital inflammatory disease and optic neuropathy associated with long-term intranasal cocaine abuse: 2 cases and literature review. Orbit (London). 2017;36:350–355. doi:10.1080/01676830.2017.1337178.

- Leibovitch I, Khoramian D, Goldberg RA. Severe destructive sinusitis and orbital apex syndrome as a complication of intranasal cocaine abuse. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:499–501. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2005.11.019.

- Badakere A, Patil-Chhablani P. Orbital apex syndrome: a review. Eye Brain. 2019;11:63–72. doi:10.2147/EB.S180190.

- Dua HS, Said DG, Messmer EM, et al. Neurotrophic keratopathy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2018. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2018.04.003.

- Rose GE, Wright JE. Trigeminal sensory loss in orbital disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78:427–429. doi:10.1136/bjo.78.6.427.

- Yagci A. Update on peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;747. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S24947.

- Artifoni M, Rothschild PR, Brézin A, Guillevin L, Puéchal X. Ocular inflammatory diseases associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10:108–116. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2013.185.

- Mondino BJ. Inflammatory diseases of the peripheral cornea. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:463–472. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(88)33164-7.

- Sahu C, Sahu C. Peripheral ulcerative keratitis. In: Comprehensive Notes in Ophthalmology; 2011. doi:10.5005/jp/books/11266_17.

- Cao Y, Zhang W, Wu J, Zhang H, Zhou H. Peripheral ulcerative keratitis associated with autoimmune disease: pathogenesis and treatment. J Ophthalmol. 2017;2017:1–12. doi:10.1155/2017/7298026.

- Galor A, Thorne JE. Scleritis and peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2007;33:835–854. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2007.08.002.

- Cohen Tervaert JW, Popa ER, Bos NA. The role of superantigens in vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1999;11:24–33. doi:10.1097/00002281-199901000-00005.

- Vignesh AP, Srinivasan R, Vijitha S. Ocular syphilis masquerading as bilateral peripheral ulcerative keratitis. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2016;6:204–205. doi:10.1016/j.tjo.2016.06.002.

- Lood C, Hughes GC. Neutrophil extracellular traps as a potential source of autoantigen in cocaine-associated auto immunity. Rheumatol (United Kingdom). 2017. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kew256.

- Friedman DR, Wolfsthal SD. Cocaine-induced pseudovasculitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:671–673. doi:10.4065/80.5.671.

- Espinoza LR, Alamino RP. Cocaine-induced vasculitis: clinical and immunological spectrum. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2012;14:532–538. doi:10.1007/s11926-012-0283-1.

- Peikert T, Finkielman JD, Hummel AM. et al. Functional characterization of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in patients with cocaine-induced midline destructive lesions. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1546–1551. doi:10.1002/art.23469.

- Subesinghe S, Van Leuven S, Yalakki L, Sangle S, Cocaine DD. ANCA associated vasculitis-like syndromes – a case series. Autoimmun Rev. 2018;17:73–77. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2017.11.011.

- Mrg P, Ortiz-González VL, Betancourt M, Mercado R. Cocaine-induced vasculitis: is this a new trend? Open Access Rheumatol Res Rev. 2013. doi:10.2147/OARRR.S51524.

- Trimarchi M, Bussi M, Sinico RA, Meroni P, Specks U. Cocaine-induced midline destructive lesions - an autoimmune disease? Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:496–500. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2012.08.009.

- Veronese FV, Dode RSO, Friderichs M, et al. Cocaine/levamisole-induced systemic vasculitis with retiform purpura and pauci-immune glomerulonephritis. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2016;49(5). doi:10.1590/1414-431X20165244.

- Jiménez-Gallo D, Albarrán-Planelles C, Linares-Barrios M. et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum and Wegener granulomatosis-like syndrome induced by cocaine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:878–882. doi:10.1111/ced.12207.