ABSTRACT

Background: Trachoma, a leading cause of blindness, is targeted for global elimination as a public health problem by 2020. In order to contribute to this goal, countries should demonstrate reduction of disease prevalence below specified thresholds, after implementation of the SAFE strategy in areas with defined endemicity. Zimbabwe had not yet generated data on trachoma endemicity and no specific interventions against trachoma have yet been implemented.

Methods: Two trachoma mapping phases were successively implemented in Zimbabwe, with eight districts included in each phase, in September 2014 and October 2015. The methodology of the Global Trachoma Mapping Project was used.

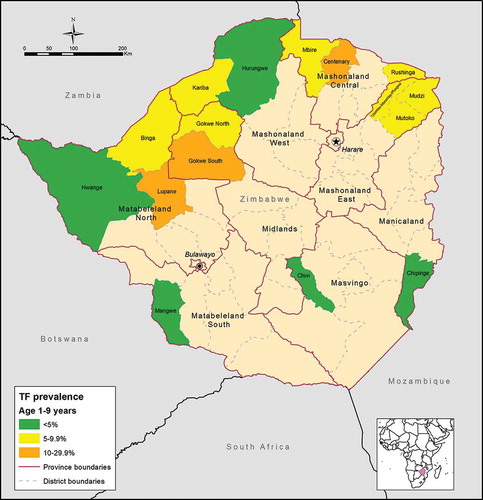

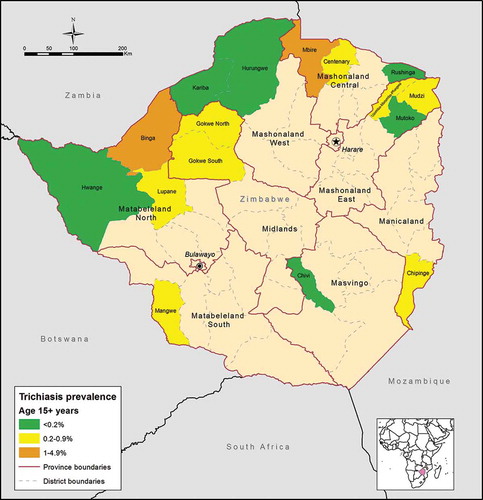

Results: Our teams examined 53,211 people for trachoma in 385 sampled clusters. Of 18,196 children aged 1–9 years examined, 1526 (8.4%) had trachomatous inflammation–follicular (TF). Trichiasis was observed in 299 (1.0%) of 29,519 people aged ≥15 years. Of the 16 districts surveyed, 11 (69%) had TF prevalences ≥10% in 1–9-year-olds, indicative of active trachoma being a significant public health problem, requiring implementation of the A, F and E components of the SAFE strategy for at least 3 years. The total estimated trichiasis backlog across the 16 districts was 5506 people. The highest estimated trichiasis burdens were in Binga district (1211 people) and Gokwe North (854 people).

Conclusion: Implementation of the SAFE strategy is needed in parts of Zimbabwe. In addition, Zimbabwe needs to conduct more baseline trachoma mapping in districts adjacent to those identified here as having a public health problem from the disease.

Introduction

Trachoma is an infectious eye disease caused by the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis. Classed by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a neglected tropical disease, trachoma is the world’s leading infectious cause of blindness. It is thought to be a public health problem in 42 countries, mostly in Africa and the Middle East.Citation1 Early signs are most commonly found in young children, with female adults (who generally spend more time with children) having the highest burden of advanced, blinding disease.Citation2 Globally, 200 million are thought to be at risk.Citation1

Table 1. Districts selected for the first two phases of trachoma mapping in Zimbabwe, 2014–2015.

Table 2. Sampling by district, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Zimbabwe, 2014–2015.

Table 3. Examination results, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Zimbabwe, 2014–2015.

Table 4. Estimated population-level prevalence of trachomatous inflammation–follicular (TF) in children aged 1–9 years by district, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Zimbabwe, 2014–2015.

Table 5. Recommendations for implementation of components of the SAFE strategy based on prevalence of trachomatous–inflammation follicular (TF) and trichiasis, Zimbabwe, 2014–2015.

Table 6. Estimated population-level prevalence of trichiasis and estimated trichiasis surgery backlogs by district, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Zimbabwe, 2014–2015.

Table 7. Multilevel univariable associations with trachomatous inflammation–follicular (TF) in children aged 1–9 years, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Zimbabwe, 2014–2015.

Table 8. Independent predictors of trachomatous inflammation–follicular (TF) in children aged 1–9 years, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Zimbabwe, 2014–2015.

Infection is thought to be transmitted from eye to eye by flies, fingers and fomites bearing ocular or nasal secretions of infected individuals.Citation3–Citation6 Repeated conjunctival infection causes chronic inflammation, eventually causing scarring and (in some people) in-turning of the eyelids so that the eyelashes touch the eye, a condition called trichiasis.Citation7,Citation8 Trachomatous conjunctival scarring also reduces tear secretion, predisposing the cornea to ulceration, which may lead to its opacification: the ultimate mechanism through which trachoma produces blindness.Citation8

Trachoma is normally found in isolated, resource-limited settings where water scarcity and low levels of sanitation and healthcare access are commonplace—conditions thought to facilitate C. trachomatis transmission.Citation3,Citation5,Citation9 In addition to direct blinding effects on individuals, trachoma profoundly affects the economies of endemic communities, where it is estimated that $2.9 to $8 billion in productivity is lost every year from the disease.Citation10,Citation11 It is against this background that trachoma has been targeted by WHO for elimination as a public health problem by the year 2020,Citation12 defined as an estimated prevalence of the clinical sign trachomatous inflammation–follicular (TF) of <5% in children aged 1–9 years, and an estimated prevalence of the clinical sign trachomatous trichiasis in those aged 15 years and greater of <0.2%.

Zimbabwe is a landlocked country in Southern Africa bordering Zambia, Mozambique, Botswana and South Africa. The estimated total population is 13,061,239, with 8,771,520 people (67.2%) living in rural areas. The country’s major ethnic groups are the Shona, Ndebele, Karanga, Ndau, Zezuru, and Manyika. Trachoma is known in Zimbabwe’s rural health clinics, but reporting on it has hitherto only been included under “general eye conditions” in national health information systems, with no formal estimates of prevalence or incidence of clinical presentation.Citation13 To date, therefore, few data exist to guide stakeholders to understand the burden of trachoma in the country, or to plan interventions where required.

There are a few specific reports on trachoma in Zimbabwe. Published in 1970, a survey in the area North-East of Harare found that 30% of the 0–5 years age group, and 23% of the 6–15 years age group, had a follicular conjunctivitis consistent with active trachoma.Citation14 A cataract surgery outreach to Gokwe South district in 2015 found so many cases of trichiasis that more surgeries were carried out for trichiasis than for cataract (unpublished data, Dr B. Macheka). It is also notable that Zimbabwe borders trachoma-endemic districts in Zambia to the North,Citation15 and Mozambique to the North-East.Citation16

As is common in many developing countries, in Zimbabwe’s rural districts, factors normally associated with trachoma are present—extreme poverty is commonplace, water access is limited, and sanitation provisions are minimal. However, the status of trachoma endemicity in large areas of the country is unclear. Definitive district-level prevalence data are needed in order to guide the Ministry of Health and their partners to plan for national trachoma elimination as a public health problem.

We conducted 16 district-level population-based trachoma prevalence surveys in two phases, in 2014 and 2015, with the aims of estimating the prevalence of TF in children aged 1–9 years, and the prevalence of trichiasis in those aged 15 years and greater, as well as obtaining data on the water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) variables most commonly associated with trachoma. We report the results of those surveys in this paper.

Methods

Study design and study sites

With few existing data, we were not confident of where formal surveys were justified, so a phased approach was used. In the first phase, in September 2014, eight population-based cross sectional prevalence surveys were carried out, with one district selected from each of the eight provinces of Zimbabwe (Manicaland, Mashonaland East, Mashonaland Central, Mashonaland West, Midlands, Masvingo, Matabeleland South, Matabeleland North). Districts were selected based on suspected trachoma endemicity from existing government reports. In the second phase, districts adjacent to phase 1 districts in which the TF prevalence in children aged 1–9 years was ≥5% were considered for further surveys; these were undertaken in October 2015.

The overall survey protocol was implemented according to the published methodology for the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP),Citation17 with Zimbabwe-specific adaptations related to selection of populations to survey, as outlined in the previous paragraph, and procedures for obtaining consent and assent (see below). Surveys were carried out with existing administrative districts used as evaluation units. identifies the districts selected for phases 1 and 2.

Sample size estimation and sampling procedures

The sample size calculation used the single population proportion for precision formula. To have 95% confidence (α = 5%) of estimating a true TF prevalence in 1–9-year-olds of 10% with an absolute precision of 3%, assuming a cluster survey design effect of 2.65 and inflation by a factor of 1.2 to account for non-response, each survey needed to include sufficient households to expect 1222 children to be resident.Citation17 This sample size was also more than adequate to estimate a true TF prevalence in 1–9-year-olds of 4% with an absolute precision of 2%.Citation18 In rural Zimbabwe, the mean household size is 4.4 people and approximately 26% of the population is aged 1–9 years,Citation19 providing an average of 1.14 1–9 year-olds per household. Therefore, 1222/1.14 = 1073 households were required per district.

Two-stage cluster sampling was used for each survey, with enumeration areas, (the lowest administrative units used for generating census data in Zimbabwe) sampled in the first stage; a sample of 45 households from each enumeration area was selected in the second stage. Selection of 24 enumeration areas per district was performed using a probability proportional to size, systematic sampling methodology, using enumeration area population sizes obtained from the Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency.Citation19 Substitution of selected enumeration areas was only permitted with approval of the study coordinator, and only when field teams found that the village no longer existed, or was unreachable by vehicle, motorcycle, boat or foot. In those cases, teams visited the geographically next-nearest enumeration area. An additional cluster was selected in Mutoko district to ensure an adequate sample size was obtained.

Household selection was performed on the day of the survey, at village level. As household listings were not available, compact segment sampling was used. The survey team liaised with the village chief who provided a map in which segments, each comprising approximately 45 households, were demarcated. Teams then randomly selected one segment by drawing straws, and included all households in the selected segment.

At sampled households, graders examined consenting individuals for signs of trachoma using the WHO simplified grading system,Citation7 2.5× magnifying loupes, and sunlight illumination. All data were recorded electronically in a custom-made smartphone application (LINKS, Task Force for Global Health, US), as previously described.Citation17

Survey teams

Teams were composed of one grader, one recorder, one village chief/guide and a driver. Graders were Ophthalmic Nurses who had been trained and certified by the GTMP. Recorders were GTMP-certified Provincial Health Information Officers. Eight survey teams were trained, using version 3 of the standardized GTMP training system,Citation20 in Kwekwe, Zimbabwe.

At the central level, coordination and supervision were organized by the National NTD Task Force Committee through the Epidemiology and Disease Control Department, Ministry of Health and Child Care. Four field supervisors (members of the Zimbabwe Neglected Tropical Diseases steering committee) ensured quality data collection.

Ethics statement

The survey protocol was approved by the National Ethical Regulatory Board (Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe; reference MRCZ/A/1893) and the Ethics Committee of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (reference numbers 6319 and 8355). Participation in the survey was voluntary. Survey team members explained to village chiefs and members of the selected households the purpose of the survey and what their participation involved. Participants were assured of confidentiality and were made aware that decisions on whether or not to take part would in no way affect future service provision. No adverse effects were anticipated from participating. For all individuals with trichiasis or active trachoma, referral or antibiotic treatment, respectively, was provided. Written, informed consent was obtained from all adults aged ≥18 years, and from parents, caregivers, or heads of households for those under 18 years of age. Assent was obtained from individuals aged 15–17 years after parental informed consent had been granted.

WASH and climate data

WASH variable data were collected by data recorders using direct observation and standardized interview questions with the household head. Variables related to water access and source type for both drinking and washing, and sanitation types, used WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme definitions for improved and unimproved water and sanitation sources.Citation21,Citation22 We sought climatic data possibly related to C. trachomatis infection transmission,Citation23 based on knowledge of the epidemiology of trachoma in comparable environments. Data derived from local meteorological stations were obtained from WorldClim/BioClim (worldclim.org),Citation24 at a resolution of 2.5 arc-minutes (~5km): mean annual temperature, mean annual precipitation, and maximum temperature in the hottest month. Altitude was recorded by collecting Global Positioning System coordinates at each household at the time of survey.

Data management

Descriptive data were produced using Excel 2010. Adjusted prevalence and confidence intervals were calculated using R 3.0.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2013). In order to estimate the population-level outcomes required for existing WHO guidelines, both TF and TT proportions were adjusted at cluster-level. This was done to partially account for the fact that conducting surveys during daylight hours results in a proportion of school-attending children and working adults (often males) remaining unexamined. The TF prevalence in children aged 1–9 years was adjusted for age in 1-year age-bands using the latest available census data.Citation19 Trichiasis prevalence estimates in those aged 15 or more years were adjusted for age and sex in 5-year age-bands. For each district, the overall outcome prevalence was estimated by taking the arithmetic mean of adjusted cluster-level proportion estimates from that district. Trichiasis prevalence for the whole population was estimated by halving the 15+ years trichiasis prevalence.Citation25 Confidence intervals were generated using a bootstrapping approach, randomly resampling with replacement from the set of all adjusted cluster-level outcome proportions for each district, and calculating the arithmetic mean of these proportions from the set of resampled clusters. A 95% confidence interval was estimated by taking the 2.5th and 97.5th centiles of these results, obtained over 10,000 replicates. Bootstrap estimates assumed normally distributed proportions, which held in all but the very lowest trichiasis prevalence estimates. The confidence intervals for zero counts were estimated by an exact binomial confidence interval.

Raster point values for climatic variables were extracted using ArcGIS 10.3 (Spatial Analyst). Risk factor analysis was performed using Stata 10.2 (Stata Corp, TX, USA). A multi-level hierarchical model was used to account for clustering at enumeration area and household level. Co-linearity of variables was not an absolute exclusion criterion, but was assessed using Mantel-Haenszel tests of association. A stepwise inclusion approach was used for the multivariable model, with variables considered for inclusion if the univariable association was significant at the p < 0.05 level (Wald’s test). Variables were retained in the model if statistical significance was found at the p < 0.05 level (Likelihood ratio test).

Estimation of design effect

The increase in variance of the estimated proportion of children with TF in each district, due to the clustered design of the survey, is given by the design effect (DE). The DE for each district was estimated by dividing the bootstrapped variance estimate of the cluster-level TF proportions by the equivalent simple random sampling (SRS) variance estimate for the same sample size.

Assuming SRS, if p is the proportion of children examined with TF in a given district, and n is the total number of children examined in the same district, then the SRS variance in this proportion is given by p(1−p)/n, the formula for the variance of a Normally distributed sample proportion.

Results

Trachoma survey phases 1 and 2 were conducted in September 2014 and October 2015 respectively. The districts targeted in phase 2 were based on their proximity to those phase 1 districts in which a TF prevalence of greater than 5% in children had been observed. shows data on numbers of people registered and examined for each district. A total of 17,299 households were visited, from which 55,992 people were registered. Of these, 53,211 (95%) were examined. Of those examined, 23,360 (43.9%) were males.

Results of examination by district are shown in . Of 18,196 children aged 1–9 years examined, 1526 (8.4%) had TF, whereas TF was observed in only 225 (4.1%) of 5496 children aged 10–14 years. No children aged 1–9 years, and only three children aged 10–14 years, had trichiasis. Of the 29,519 individuals aged 15 years and greater who were examined, 299 cases of trichiasis were identified (1.0%). Overall, 36 cases of trichiasis were in those aged 15–39 years, and 263 cases were in those aged 40 years or greater.

and show the adjusted prevalence of TF among 1–9-year-olds, by district. presents recommendations for implementation of SAFE, based on adjusted prevalence of TF and trichiasis in each surveyed district. Five districts had TF prevalence <5%, the elimination threshold for TF. In these districts, according to WHO guidelines, the A, F and E components of SAFE are not necessary for the purposes of trachoma’s elimination as a public health problem. A total of eight districts had a TF prevalence between 5 and 9.9%, and a further three (Centenary, Gokwe South and Lupane) had a TF prevalence of 10–29.9%; according to WHO guidelines, these 11 districts require implementation of the A, F and E components of SAFE before resurvey.

Figure 1. Estimated prevalence of trachomatous inflammation–follicular (TF) among children aged 1–9 years, by district, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Zimbabwe, 2014–2015.

and show the adjusted district-level prevalence of trichiasis in the population aged ≥15 years, and estimated surgery backlogs. Of 16 districts, 10 (62.5%) had adjusted trichiasis prevalence ≥0.2%. Overall the estimated trichiasis backlog was 5506 individuals. This figure was highest in Binga district, where an estimated 1297 people will need to be counselled for possible surgery.

Figure 2. Adjusted prevalence of trichiasis in adults aged 15 years or greater, by district, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Zimbabwe, 2014–2015.

Estimation of design effect

The median number of children examined per cluster was 45 (Interquartile range [IQR]: 37–56); TF cases per cluster was three (IQR: 1–5); proportion of children with TF per cluster was 0.058 (IQR: 0.025–0.120), and the median number of children examined per district was 1142 (IQR: 1011–1267.25). The median bootstrap variance of the primary sampling unit (cluster-level) TF proportions was 11.0 × 10−Citation5 (IQR: 4.1–34.5), and the median DE over all 16 districts with a median of 45 children examined per cluster was 2.20 (IQR: 1.27–3.47).

TF risk factors

Independent predictors of TF were identified on multivariable analysis. The full univariable results are shown in . In the multivariable model (), children aged 1–5 years had odds of having TF 1.7 times those of children aged 6–9 years (95%CI 1.49–1.99). In addition, children who lived in households with a total of four or more children had odds of TF 1.7 times those of children living in a household with fewer children (95%CI 1.27–2.15). Children living in households in which adults practised open defecation were more likely to have TF than those who did not (OR = 1.9, 95%CI 1.65–2.28).

Living in areas where annual rainfall was at least 600 mm was associated with an increased odds of TF (OR = 2.8, 95%CI 2.15–3.7). This effect was not altered by the inclusion of altitude in the model. Children living in households in which the maximum annual outside temperature exceeded 35°C had lower odds of trachoma than children who lived in cooler areas. (OR = 0.3, 95%CI 0.21–0.39). Annual mean temperature was not included in the final model due to co-linearity with the maximum annual temperature. Living in a household at an altitude of more than 750 m above sea level was associated with a decreased odds of TF (OR = 0.6, 95%CI 0.52–0.73) ().

Discussion

We have estimated the prevalence of TF and trichiasis in selected areas of Zimbabwe. Making data available on the epidemiology of trachoma at district level is the first critical step towards planning for the implementation of the SAFE strategy. Based on our results, 11 districts (69% of those districts surveyed) were confirmed to have active trachoma as a public health problem according to WHO guidelines, with prevalence of TF >5% in children aged 1–9 years (). Of 16 districts mapped, 3 (19%) had TF prevalence >10% and, according to WHO recommendations require implementation of the A, F and E components of SAFE for at least 3 years before re-survey. This is to say that these districts need to start MDA with azithromycin as soon as possible.

We found that TF was less likely to be found at higher altitudes, consistent with a recent systematic review of trachoma risk factors.Citation26 In addition, the decreasing risk of TF with increasing maximum annual temperatures has been reported before,Citation27 thought to be associated with decreased eye-seeking fly activity at higher temperatures.Citation28 However, decreasing fly activity at lower temperatures has also been used to explain the converse relationship.Citation26 The associations with TF found in this analysis may aid program managers to target perceived higher risk areas in Zimbabwe, although caution may be needed in that climate-related risk factors may associate with trachoma only in specific geographic locales.

These data show that there is a significant trichiasis surgery backlog that needs to be addressed, with the highest numbers of surgeries needed in Binga (1297), Gokwe North (854) and Gokwe South (662) districts (). These results confirm previous observations by ophthalmologists regarding the burden of trichiasis in Gokwe, in which a visiting cataract surgery outreach team was overwhelmed in 2015 by the number of individuals found to have trichiasis, and ended up performing more trichiasis than cataract surgeries. In districts with adjusted trichiasis prevalence ≥0.2% in adults, significant expansion of existing trichiasis surgical services is needed. In keeping with the known limitations of carrying out household surveys during the day, of those aged 15 years and greater, 62.0% of those examined were female. It has yet to be established whether those males who are missing from the surveys are representative of those who were included. This is a potential limitation, particularly when extrapolating survey results to population-level trichiasis estimates, and the significance of this may need to be established with further research. Further limitations of our work include the risk of multiple comparisons inflating the alpha error in the multivariable analysis, and the difficulty in ensuring consistent clinical grading over time, even with rigorous initial training. Although some believe that photography might have allowed more consistent grading across graders and time, as well as facilitating a process of auditing, there are inherent practical difficulties in reliably capturing large numbers of images from children who may not be enthusiastic about being examined,Citation29 in transmitting those images elsewhere using low bandwidth internet connections, and in having the pictures reviewed by suitably qualified graders.

shows recommended intervention strategies in districts surveyed according to the population-level prevalence estimates of TF and trichiasis. Based on this analysis, significant efforts will be needed in Zimbabwe to implement the SAFE strategy in order to achieve elimination of trachoma as a public health problem by the year 2020.

Zimbabwe, by mapping trachoma in 16 districts to date, has made a much needed start towards generating the evidence base for planning a national trachoma program. We readily acknowledge, however, that our findings are only applicable to the districts studied here, and should not be interpreted as being representative of the country as a whole. An important corollary of this is that areas adjacent to the high-prevalence districts found in these surveys () should now be considered suspected endemic. Further efforts to more completely delineate the endemic foci, and to put in place interventions where they are required, should now follow.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the writing and content of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Secretary for Health of Zimbabwe for the support and encouragement, and to the sampled communities for their good-humoured participation.

Funding

This study was principally funded by the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) grant from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (ARIES: 203145) to Sightsavers, which led a consortium of non-governmental organizations and academic institutions to support ministries of health to complete baseline trachoma mapping worldwide. The GTMP was also funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the ENVISION project implemented by RTI International under cooperative agreement number AID-OAA-A-11-00048, and the END in Asia project implemented by FHI360 under cooperative agreement number OAA-A-10-00051. A committee established in March 2012 to examine issues surrounding completion of global trachoma mapping was initially funded by a grant from Pfizer to the International Trachoma Initiative. AWS was a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellow (098521) at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, and is now an employee of the World Health Organization (WHO); the views expressed in this article are the views of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views or policy of WHO. None of the funders had any role in project design, in project implementation or analysis or interpretation of data, in the decisions on where, how or when to publish in the peer-reviewed press, or in preparation of the manuscript.

References

- World Health Organization. Trachoma: Fact Sheet. Geneva: WHO, 2016.

- Cromwell EA, Courtright P, King JD, et al. The excess burden of trachomatous trichiasis in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2009;103:985–992.

- Burton MJ, Mabey DCW. The global burden of trachoma: a review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2009;3(10).

- West SK, Congdon N, Katala S, Mele L. Facial cleanliness and risk of trachoma in families. Arch Ophthalmol 1991;109:855–857.

- Emerson PM, Lindsay SW, Alexander N, et al. Role of flies and provision of latrines in trachoma control: cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;363(9415):1093–1098.

- Barenfanger J. Studies on the role of the famiy unit in the transmission of trachoma. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1975;24:509–515.

- Thylefors B, Dawson CR, Jones BR, et al. A simple system for the assessment of trachoma and its complications. Bull World Health Organ 1987;65:477–483.

- Solomon AW, Peeling RW, Foster A, Mabey DCW. Diagnosis and assessment of trachoma. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004;17:982–1011.

- Prüss A, Mariotti SP. Preventing trachoma through environmental sanitation: a review of the evidence base. Bull World Health Organ 2000;78:258–266.

- Frick KD, Hanson CL, Jacobson GA. Global burden of trachoma and economics of the disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2003;69(5 Suppl.):1–10.

- Frick KD, Basilion EV, Hanson CL, Colchero MA. Estimating the burden and economic impact of trachomatous visual loss. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2003;10:121–132.

- World Health Organization (WHO). World Health Assembly. Global Elimination of Blinding Trachoma. 51st World Health Assembly, Geneva, 16 May 1998, Resolution WHA51.11. Geneva: WHO, 1998.

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. Zimbabwe Annual National Health Profiles. Harare: Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Care, 2012.

- Jamieson SW. Eye survey – Mrewa Trust lands. Postgrad Med J 1970;46(539):557–561.

- Astle WF, Wiafe B, Ingram AD, et al. Trachoma control in Southern Zambia – an international team project employing the SAFE strategy. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2006;13:227–236.

- Abdala M, Singano CC, Willis R, et al. The epidemiology of trachoma in Mozambique: results of 96 population-based prevalence surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2018;25(Sup 1):201–210.

- Solomon AW, Pavluck A, Courtright P, et al. The Global Trachoma Mapping Project: methodology of a 34-country population-based study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2015;22:214–225.

- World Health Organization. Report of the 3rd Global Scientific Meeting on Trachoma, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MA, 19–20 July 2010. Geneva: WHO, 2010.

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. Zimbabwe Population Census. Harare, 2012.

- Courtright P, Gass K, Lewallen S, et al. Global Trachoma Mapping Project Training for Mapping of Trachoma. London: International Coalition for Trachoma Control, 2015.

- World Health Organization (WHO)/UNICEF. Improved and unimproved water sources and sanitation facilities. WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) for Water Supply and Sanitation. Accessed October 26, 2015 from: http://www.wssinfo.org/definitions-methods/watsan-categories/

- Exley JLR, Liseka B, Cumming O, Ensink JHJ. The sanitation ladder, what constitutes an improved form of sanitation? Environ Sci Technol 2015;49:1086–1094.

- Smith JL, Sivasubramaniam S, Rabiu MM, et al. Multilevel analysis of trachomatous trichiasis and corneal opacity in Nigeria: the role of environmental and climatic risk factors on the distribution of disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015;9(7):e0003826.

- Hijmans RJ, Cameron SE, Parra JL, et al. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol 2005;25:1965–1978.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Report of the 2nd Global Scientific Meeting Trachoma, Geneva, 25–27 August, 2003. Geneva: WHO, 2003.

- Ramesh A, Kovats S, Haslam D, et al. The impact of climatic risk factors on the prevalence, distribution, and severity of acute and chronic trachoma. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013;7(11):e2513.

- Koukounari A, Touré S, Donnelly CA, et al. Integrated monitoring and evaluation and environmental risk factors for urogenital schistosomiasis and active trachoma in Burkina Faso before preventative chemotherapy using sentinel sites. BMC Infect Dis 2011;11:191.

- Toyama G, Ikeda JK. Predation as a factor in seasonal abundance of Musca sorbens Wiedemann (Diptera: Muscidae). Proceedings, Hawaiian Entomol Soc. 1981; XXIII(3).

- Solomon AW, Bowman RJC, Yorston D, et al. Operational evaluation of the use of photographs for grading active trachoma. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2006;74:505–508.

Appendix

The Global Trachoma Mapping Project Investigators are: Agatha Aboe (1,11), Liknaw Adamu (4), Wondu Alemayehu (4,5), Menbere Alemu (4), Neal D. E. Alexander (9), Ana Bakhtiari (2,9), Berhanu Bero (4), Simon J. Brooker (1,6), Simon Bush (7,8), Brian K. Chu (2,9), Paul Courtright (1,3,4,7,11), Michael Dejene (3), Paul M. Emerson (1,6,7), Rebecca M. Flueckiger (2), Allen Foster (1,7), Solomon Gadisa (4), Katherine Gass (6,9), Teshome Gebre (4), Zelalem Habtamu (4), Danny Haddad (1,6,7,8), Erik Harvey (1,6,10), Dominic Haslam (8), Khumbo Kalua (5), Amir B. Kello (4,5), Jonathan D. King (6,10,11), Richard Le Mesurier (4,7), Susan Lewallen (4,11), Thomas M. Lietman (10), Chad MacArthur (6,11), Colin Macleod (3,9), Silvio P. Mariotti (7,11), Anna Massey (8), Els Mathieu (6,11), Siobhain McCullagh (8), Addis Mekasha (4), Tom Millar (4,8), Caleb Mpyet (3,5), Beatriz Muñoz (6,9), Jeremiah Ngondi (1,3,6,11), Stephanie Ogden (6), Alex Pavluck (2,4,10), Joseph Pearce (10), Serge Resnikoff (1), Virginia Sarah (4), Boubacar Sarr (5), Alemayehu Sisay (4), Jennifer L. Smith (11), Anthony W. Solomon (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11), Jo Thomson (4), Sheila K. West (1,10,11), Rebecca Willis (2,9).

Key: (1) Advisory Committee, (2) Information Technology, Geographical Information Systems, and Data Processing, (3) Epidemiological Support, (4) Ethiopia Pilot Team, (5) Master Grader Trainers, (6) Methodologies Working Group, (7) Prioritisation Working Group, (8) Proposal Development, Finances and Logistics, (9) Statistics and Data Analysis, (10) Tools Working Group, (11) Training Working Group.