ABSTRACT

Background

Eye health has widespread implications across many aspects of life, ranging from the individual to the societal level. Vision 2020: The Right to Sight is an initiative that was conceptualised in 1997 and launched in 1999. It was led by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness (IAPB) in response to the increasing prevalence of blindness. Approximately 80% of the causes of blindness were avoidable. Hence, the initiative set out to eliminate the major causes of avoidable blindness. These included cataract, uncorrected refractive error, trachoma, onchocerciasis, and childhood blindness.

Methods

An electronic literature search was performed using PubMed, MEDLINE and Embase databases to assess the impacts of the Vision 2020 initiative.

Results and Conclusion

The Vision 2020 initiative was ambitious and was essential in catapulting the issue of avoidable blindness in the spotlight and putting it on the global health agenda. The causes of avoidable blindness remain and have not been eliminated. However, there have been noticeable changes in the distribution of the causes of avoidable blindness since the conception of Vision 2020, and this is mainly due to demographic shifts globally. We highlight some of the remaining challenges to acheiving avoidable blindness including, population size, gender disparities in access to eyecare services, and the professional workforce.

Introduction

Visual impairment is a major public health concern and imparts significant adverse effects at the individual and societal level. The year 2020 was a pivotal year for global eye health. It marked the conclusion of the Vision 2020: The Right to Sight initiative which has guided action towards the prevention of blindness for the past two decadesCitation1This literature review aims to evaluate the objectives of the World Health Organization (WHO) Vision 2020: Right to Sight initiative and ascertain to what extent those objectives have been met and what the remaining challenges may be.

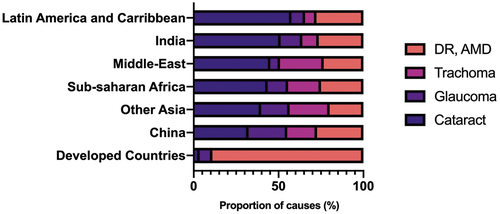

Impaired vision and eye health have impacts on general health and well-being that can have a subsequent impact on quality of life.Citation2 Impairment of vision can cause or exacerbate inequalities in society and poverty through reduced employment prospects, educational opportunities, and outcomes. In 1990, there was an estimated 38 million people affected with blindness globally and an additional 110 million people affected with low vision.Citation3,Citation4 In comparison to previous years, the estimates for the number of people living with blindness were 28 million in 1978 and 31 million in 1984.Citation5 These figures, however, are not directly comparable as they are derived using three different methodological approaches.Citation5 In 1990, approximately 80% of the cases of blindness were avoidable and approximately 90% were observed in developing countries (notably, 75% occurred in Asia and Africa).Citation3,Citation4 Seeing as there is a strong correlation between ageing and the incidence of blindness, these figures were projected to double to 76 million by 2020.Citation6 Global data on blindness in 1990 showed that cataract (41.8% of all causes) and trachoma (15.5% of all causes) accounted for more than two-thirds of all blindness. This was followed closely by glaucoma (13.5% of all causes).Citation4 Disparities were observed in the prevalence of the causes of blindness by region, with cataract presenting a greater burden in less developed countries and diabetic retinopathy and macular degeneration predominating in well-developed countries (). This disparity may have been explained, at least partly, by the reduced rate of cataract operations per million population per year in Africa compared with Europe, India, and USA.Citation3

Figure 1. Major causes of blindness (as % of total causes) in different geographical regions in 1990. Data used from Thylefors et al 1995.

Without intervention, the number of individuals with blindness was estimated to reach 76 million by 2020 primarily due to a rapidly growing ageing population in most countries (by 2020 the number of people aged older than 50 years was projected to double to 2 billion).Citation5 This sparked the foundation of the Vision 2020: The Right to Sight initiative. This was led by WHO and the IAPB on 18th February 1999.Citation1,Citation5

The primary aim of this initiative was to ‘to eliminate avoidable blindness by 2020’, chiefly ‘by focussing initially on certain diseases that are the main causes of blindness for which proven cost-effective interventions are available’.Citation1 Vision 2020 also targets those suffering with low vision, that is patients who require rehabilitative services to enhance residual vision. Strategies to achieve this goal focused primarily on disease control as well as human resource, infrastructural and technological developments.Citation3,Citation7 In each country, it is intended that a national blindness prevention committee oversees the Vision 2020 agenda.

Achievements of Vision 2020

Impact on the global prevalence of blindness and vision impairment

In 2020, it is estimated that there were 43.3 million people with blindness, of whom 23 · 9 million (55%) were estimated to be female.Citation8 Two hundred and ninety-five million people were estimated to have MSVI, of whom 163 million (55%) were female. Between 1990 and 2020, in adults aged 50 years or older, the age-standardised global prevalence of blindness decreased by 28 · 5%. This decrease was larger in males (33.2% reduction) than females (25% reduction). On the other hand, the age-standardised prevalence of MSVI increased by 2.5%. By 2050, it was estimated there will be 61 million people with blindness and a further 474 million people with MSVI. Regional difference in the prevalence of blindness were also observed. In 2020, the largest number of people with blindness resided in south Asia, followed by east Asia and southeast Asia. The crude prevalence of blindness ranged from 1 · 94 cases per 1000 in high-income North America to 8 · 75 cases per 1000 in southeast Asia.

Globally, the leading cause of blindness in 2020 was cataract, which affected 15.2 million people.Citation8 This was followed by glaucoma (which accounted for 3.6 million cases), uncorrected refractive error (which was responsible for 2.3 million cases), AMD (responsible for 1.8 million cases) and diabetic retinopathy (accounting for 0.86 million cases). Uncorrected refractive error (accounting for 86.1 million cases) and cataract (accounting for 78.8 million cases) were the leading causes of MSVI.Citation8

Global impact on the main causes of avoidable blindness

Cataract

Cataract was the leading cause of avoidable blindness at the time of Vision 2020, affecting approximately 19 million people.Citation4,Citation9 The burden of cataract as the cause of avoidable blindness was varied depending on geographical regions ().Citation4 The incidence of cataract was approximated at 1 million per year, which was due to the combination of a growing and ageing population.Citation9 The main reason behind the burden of cataract is the backlog of surgeries. Cataract operations totalled 10 million in 2000 but this would need to be tripled to target the backlog of patients.Citation9,Citation10 The burden of cataract is greater in the developing world due to late presentation and a lack of geographic distribution of surgeons. People tend to seek advice regarding cataract when advanced disease has occurred (which makes operating more difficult) or when the hard lens causes glaucoma and results in a painful vision loss.Citation11 Several reasons may explain the late presentation and include lack of awareness, socioeconomic inequalities, and gender inequalities.

There are several indicators available for cataract service delivery. The most reported of these is cataract surgical rate (CSR). The CSR is expressed as operations per year per million population.Citation10 Other indicators of cataract service delivery include the cataract surgical coverage (CSC) and the effective cataract surgical coverage (eCSC). The CSC measures the number of people who have had cataract surgery as a proportion of those who have had the surgery in addition to those who are eligible for surgery.Citation12 In fact, the global action plan proposes the use of CSC as a measure of cataract service delivery. Ramke et al. argue that CSC (and CSR) is a poor indicator of the progress of cataract service as it does not provide an indication of the quality of the service being provided.Citation12 Unfortunately, data on eCSC is not yet widely available. Using some of the data already collected in the population-based surveys, Ramke et al. calculated that on average 36.7% of people that received cataract surgery had obtained a good visual outcome.Citation12

At the time of Vision 2020 inception, CSR figures varied from 5, 500 in North America to less than 500 in Africa, China, and less-developed areas in the rest of Asia.Citation9 Foster proposes that the main reasons behind the low CSR observed in less economically developed countries was multifaceted and due to a combination of poor outcomes post-surgery (which causes low demand from patients), high cost of surgery (further lowering demand by patients) and a lack of ophthalmologists (who are able to carry out cataract surgery).Citation9

Data from 2020 shows that over 15 million people are affected with blindness due to cataract.Citation8 This is not to say that Vision 2020 has had no impact on the burden of cataract. Wang et al. analysed the CSR trends from 152 countries from 2005 to 2014 and found that most countries had an increase in the number of cataract surgeries with the greatest increase observed in Iran and Argentina.Citation13 This study also further emphasised the close relationship between CSR and resource availability which further emphasises the importance of low-cost services to allow healthcare delivery for all.Citation13 This was further corroborated in a study that showed countries with a lower socioeconomic status has higher age-standardised DALY due to cataract which would further widen inequalities.Citation14 The increase in population size and age have led to even further strains on cataract services worldwide and the supply must grow to meet the demand. In a cross-sectional study assessing success factors affecting CSR in sub-Saharan Africa, factors that were associated with a high CSR included having at least one fixed surgical facility in the area; having an availability of operating theatre; the number of surgeons per million population; and the presence of an eye department manager in the facility.Citation15 Biometry and the presence of an eye department manager in the facility were associated with better visual acuity outcomes following cataract surgery.Citation15

In 2020, the global median CSR was 1747.Citation16 Due to the considerable variation in data between individual countries, the median has been reported. Of the 176 countries for which CSR data was collected, 56 had a CSR of less than 1,000. The CSR ranged from 497 in Sub-Saharan Africa to 8307 in high-income countries.Citation16 Previous research has also demonstrated that CSR is associated with socioeconomic development (expressed as a country’s gross domestic product, gross national income or human development index).Citation13,Citation17,Citation18

Trachoma

In 1993 WHO adopted the ‘SAFE’ strategy for the prevention of trachoma. This consists of surgery, antibiotics (azithromycin), facial cleanliness and environmental improvements to facilitate sanitisation.Citation19 In 1996 WHO launched the Alliance for the Global Elimination of Trachoma by 2020.Citation19 Trachoma remained a focus in Vision 2020 and this has been critical in the advances in trachoma management including the development of the global trachoma mapping project in 2012 which would allow for better focus of treatments.Citation19 These efforts, combined with a generous donation of azithromycin from Pfizer, meant a global antibiotic coverage of 57% in 2019.Citation20 These efforts resulted in a reduction of over 90% in the burden of trachoma from 1.5 billion in 2002 to 142 million in 2019.Citation19 As of 07 March 2022, 14 countries had reported achieving elimination goals.Citation20 Trachoma remains to be hyperendemic in rural areas of Africa, Central, and South America, Asia, Australia, and the Middle East.Citation20 Trachoma is responsible for the blindness or visual impairment of approximately 1.9 million people and causes 1.4% of all blindness worldwide.Citation20 Overall, Africa remains the most affected continent, and the one with the most intensive control efforts. Although the aim of eradication by 2020 has not been achieved and certainly trachoma remains a public health problem in 44 countries, certain mathematical models suggest that this may indeed be possible within the next decade.Citation19,Citation21

Onchocerciasis

Onchocerciasis was the second leading infectious cause of avoidable blindness at the time of Vision 2020 inception.Citation4 In 2000 there was an estimated 17 million people infected with onchocerciasis and upto 600, 000 people blind from it.Citation7 It was endemic in 30 countries of Africa and in certain parts of Latin America and Yemen.Citation7 At the time of Vision 2020, onchocerciasis prevention programmes were already established. The Onchocerciasis Control Program (developed in 1974), the African Program for Onchocerciasis Control (developed in 1995) and the Onchocerciasis Elimination Program of the Americas (created in 1992) are the most well-known initiatives.Citation22 Alongside these programmes, a generous donation from Merck and Co has meant that more than 80 million people worldwide receive Ivermectin (Mectizan) every year.Citation22 This has led to a therapeutic coverage exceeding 80% and a geographic coverage of nearly 100% in many countries.Citation23 This success is reflected in eradication of the disease in four countries in south America and significant reductions in parts of Africa.Citation24 The Global Burden of Disease Study estimated a prevalence of 20.9 million people worldwide, with 1.1 million people having vision loss as a result of the disease.Citation24 To date, four countries (Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, and Guatemala) have been verified as free of onchocerciasis by WHO.Citation25

Certain factors have limited the success of eradicating onchocerciasis. Firstly, although Ivermectin slows the spread of onchocerciasis, it does not eradicate the disease.Citation26 WHO recommends treating onchocerciasis with ivermectin at least once yearly for 10–15 years.Citation25 The parasite can survive for up to 15-years, therefore there needs to be a long-term treatment that can be sustained by the communities themselves as.Citation26 One way in which this can be achieved is by using a milbemycin endectocide such as Moxidectin.Citation26 Research has shown lower parasite transmission after treatment with Moxidectin compared to Ivermectin.Citation27 This may be because Moxidectin can kill the adult worms responsible for the disease. Furthermore, there is incomplete mapping of all transmission zones and suboptimal program implementation.Citation28

Although eradication has not been achieved yet, this may happen soon since collaborative efforts have meant successful establishment of onchocerciasis control programmes in all endemic African countries. The new target to eliminate onchocerciasis has been set for 2025.Citation23

Childhood blindness

In 1990, there were an estimated 1.5 million children with blindness and approximately 87% of these cases were in Asia and Africa. The commonest causes were retinal diseases and corneal scarring.Citation7 There were significant associations with the socioeconomic status of the countries, with the highest rates observed in poorer countries.Citation29 The preventable causes of childhood blindness (accounting for 60% of cases) identified by Vision 2020 included vitamin A deficiency, measles, meningitis, ophthalmia neonatorum, rubella, cataract, glaucoma and retinopathy of prematurity (ROP).Citation7 The initiative set out to focus on corneal scarring, cataract, ROP, refractive error and low vision. An interim review by Gilbert and Muhit highlighted that 7 years after Vision 2020, the rates of childhood blindness had fallen by 100, 000 and an avoidable cause remains the main precipitant in 45% of cases.Citation30 The predominant cause of childhood blindness in developing countries was corneal scarring secondary to vitamin A deficiency and measles.Citation30 Vision 2020 led to recruitment of volunteers to act as key informants to increase awareness among health authorities to specifically target vitamin A supplementation and measles immunisation as these were considered the most important.Citation30

Recent estimates have not been officially published by WHO but are promising and show a gradual decline in the rates of childhood blindness with the latest figures from 2018 showing approximately 1 million children with blindness.Citation31 The proportion of children with blindness living in lower-middle-income countries is approximately 53%.Citation31 Closing of this gap has been owed to a combination of the efforts of Vision 2020 as well as socioeconomic development.Citation31 As we move closer to achieving this target, we need to ensure several changes. Firstly, there needs to be an improvement in epidemiological data collected on childhood blindness. Currently, this data seems to be collected from schools for the blind and therefore may underestimate the true burden of childhood blindness.Citation31 In the latest study by the VLEG, the data for children were globally low.Citation8 The sparsity of data on childhood blindness explains why their analysis was focused on adults aged 50 years and older. There are also needs to an increased focus on primary healthcare and prevention to ensure early recognition and treatment of childhood blindness. Sustaining current programmes for vitamin A deficiency and measles as well as increasing the uptake of screening programmes for ROP and congenital cataract will consolidate success.Citation32

Uncorrected refractive errors

Uncorrected refractive error is one of the most easily treatable causes of visual impairment. Vision 2020 planned to enhance the provision of refraction services and eye care through early screening and encouraging close monitoring of progress.Citation7 The burden of blindness due to uncorrected refractive error increased from 6.3 million in 1990 to 6.8 million in 2010.Citation33 The figures for low vision increased from 88 million in 1990 to 101 million in 2010.Citation33 Reassuringly, there seems to be a worldwide reduction in age-standardised prevalence of uncorrected refraction error causing low vision, with the greatest reductions observed in Latin America and certain parts of Asia.Citation33 The lowest reduction rates were observed in certain parts of Africa.Citation33 The reasons for the partial success observed include; public health promotion through primary care and school screening; training of refractionists; provision of bulk supplies of cheap spectacles for patients; and the integration of low vision care in national screening programmes.Citation7,Citation30

In 2020 approximately 160 million have moderate and severe vision impairment due to uncorrected distance vision impairment and 510 million due to uncorrected near vision impairment.Citation8 Uncorrected refractive error is a growing burden, with the number of people with vision loss expected to rise by 55% by 2050.Citation34 This can be explained by growth in the population size and average life expectancy which will increase the burden of presbyopia. Simultaneously, shifts in lifestyle trends mean that myopia and myopia-related complications will see an equally enhanced projection due to increased near work activity and decreased time spent outdoors.Citation35 This increase will be exacerbated in areas where there are deficits in the optician workforce and where non-compliance among the population impedes screening and treatment efforts.

Increasing global awareness and expanding focus

Increasing awareness of the burden of blindness was one of the most major and important achievements of Vision 2020. Indeed, this would have itself facilitated many of the primary aims of the project. Most notably, placing prevention of blindness on the healthcare agenda of the WHO and its member states meant that countries ensured budgetary allocations for eye care.Citation36 The inception of World Sight Day: The Right to Sight in 2000 further shed light on global blindness. This day, occurring every second Thursday of October annually, raises awareness of blindness and visual impairment as an international public health issue. It also serves to celebrate advances in eye care treatment and encourages further changes.Citation36

Vision 2020 catapulted the issue of preventable blindness and placed it on the worldwide agenda for public health. This initiative was further built on throughout the years and was integrated in the World Health Assembly (WHA) resolutions as part of their action plans. The most recent of these is the “Universal Eye Health: A global action plan 2014–2019”.

Supporting the development of eye care services

Vision 2020 sparked interest globally and as a result multiple governments worldwide sought to increase or initiate funds allocated to eye care to reduce the burden of preventable blindness.Citation36 This goal has been exceeded in the last two decades. The funding for the prevention of vision impairment has increased through both governmental and non-governmental sources. In the first 5 years following the inception of Vision 2020, 53 countries drafted national plans for Vision 2020 and 78 had formed national committees responsible for overseeing developments of Vision 2020 objectives.Citation36 More than 100 national plans concerning the elimination of avoidable blindness had been developed by 2012.Citation22 Forming these committees and plans is not only helpful in integrating policies and services to deliver eye care but is also essential in ensuring accurate data gathering. Examples of countries that have developed their national eye health plans and formed official committees for the prevention of blindness include India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Argentina, Brazil and Mexico.Citation36 Several governments from developed countries, including Australia, United Kingdom, United States, and Germany have also supported eye care programmes in developed countries.Citation36

Moreover, there have been major efforts from non-governmental organisations that have been instrumental in helping to achieve the outcomes of Vision 2020. These included donations from Standard Chartered Bank, the Queen Elizabeth Diamond Jubilee Trust, Champalimaud Foundation, and donations from corporate companies such as Pfizer, Merck Inc and Alcon.Citation36 Vision 2020 also set up the Eye Fund in partnership with Deutsche Bank to facilitate low-interest loan to organisations and encourage eye care development.Citation36 Vision 2020 also prepared the “Developing and Action Plan” in multiple languages to serve as a guide for countries on developing, implementing, and evaluating blindness prevention plans.Citation36 This has led to an improvement in the quality of epidemiological eye health data available for advocacy and planning over the last 20 years. Additionally, further support was mobilised from the corporate sector and donations of medicines by big pharma companies such as Merck (providing ivermectin) and Pfizer (providing azithromycin) has been instrumental in aiding the elimination of onchocerciasis and trachoma, respectively.Citation36

The Vision 2020 LINKS programme was founded in 2004. This programme received funding from the Queen Elizabeth Diamond Jubilee Trust. It partners an overseas institution (particularly in Africa) with a suitable institution in the UK with the purpose of improving the quality and quantity of eye care training to members of the multidisciplinary team.Citation37 This programme has been hugely successful in forming partnerships and sharing of knowledge and expertise. More importantly, it may be the key to aiding lower-income countries tackling non-communicable diseases. In 2014, the Diabetic Retinopathy Network (which is part of the Vision 2020 LINKS programme) was developed to specifically combat the growing problem of diabetes.Citation38 This programme has had positive effects on the service provision of diabetic retinopathy in 12 countries and will likely affect many more as more partnerships are being formed.Citation38 Examples of progress in countries as a result of this programme include increased treatment and awareness in Jamaica, advancements of model programmes in south and central Africa and expansion to districts in East Africa for focus on training and tertiary centres.Citation38 The importance of these kind of programmes becomes increasingly more pertinent as the burden of non-communicable eye diseases increases in areas that have little experience in the management of these challenging conditions.

Remaining challenges to achieving avoidable blindness

Population size and demographics

The global population continues to grow and it is predicted to reach 9.7 billion in 2050.Citation39 The rate of population growth seems to be highest in the least developed countries. Since the 1980s, the region with the fasted growing population has been seen in sub-Saharan Africa.Citation39 Currently, the share of the global population aged 65 years and older is 10%. This figure is projected to increase to 16% by 2050.Citation39 By 2050, the number of people aged 65 years and older is estimated to be more than twice the number of under 5 year olds and roughly equivalent to the number of under 12 year olds.Citation39 The ageing population puts vision impairment at the forefront of the global health agenda. Cataract, glaucoma, AMD, diabetic retinopathy and presbyopia are some of the commonest causes of vision impairment.Citation40 All occur more frequently in the older population. This is made even more evident by the shift in the pattern of leading causes of preventable blindness we have observed over the last 30 years.Citation40 Whereas infectious causes such as trachoma and onchocerciasis held a larger share in the causes of preventable blindness, this has now been replaced by non-communicable eye diseases (NCED) such as glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and AMD.Citation3,Citation40 The explanation for this lies in the epidemiological transition, that is a change in lifestyle leading to a change in population health, among middle- and now low-income countries.Citation41

Secondary targets of Vision 2020 were to control other causes of blindness, such as glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy. The strategies proposed to control the burden of glaucoma included increasing awareness and education among the general population and healthcare professionals alongside providing treatment and adequate follow-up to patients.Citation7 Similar strategies were proposed for diabetic retinopathy, including education of patients and medical practitioners as well as improving diabetic retinopathy treatment services.Citation7 Increased urbanization and education, more sedentary and indoor lifestyles, less-nutritious foods, and resulting obesity explain the rising prevalence of certain diseases such as diabetes and associated cardiovascular diseases that are observed globally. Simultaneously, these shifts in lifestyle trends will mean that myopia and myopia-related complications will also increase as a result of increased near work activity and decreased time spent outdoors.Citation35

This demographic shift has been well established in high-income countries, but now encompasses all income countries.Citation42 These diseases represent a particular challenge to management as they are chronic and require on-going monitoring and input to prevent severe visual impairment that would adversely impact quality of life. These diseases remain to be incurable and tend to have a late presentation that further complicates their management. These challenges are exacerbated in lower-income countries where multi-disciplinary and patient centred approaches are not well established.Citation42 Zhang and colleagues demonstrated an increase in the global rate of disability-adjusted life years (DALY) from glaucoma between 1990 and 2017, but when adjusting for age and the size of the population the DALY rates decreased from 1995.Citation43 The findings suggest that current policies and actions have had some impact, but these will need to be significantly up scaled to cope with the demands that come with increases in population size and age. Moreover, several studies have shown associations between resources and education levels and the burden of NCED. The burden of glaucoma was associated with mean years of schooling and the gross national income per capita.Citation43 Higher AMD burden was associated with lower socioeconomic status and fewer education years.Citation44 Eye health services need considerable investment to prevent staggering rates of vision loss.

The professional work force

The number of ophthalmologists and allied healthcare professionals may have explained the regional disparity in the global burden of blindness observed at the time of conception of Vision 2020. At the start of the initiative, it was estimated there was 1 ophthalmologist per 500, 000 people in Africa.Citation3 The goal was to increase the ratio to 1: 250, 000 in Africa by 2020.Citation3 Worldwide, there is an increase in the ophthalmology workforce and this seems to reflect the efforts of Vision 2020.Citation45

Resnikoff et al. analysed data on the number of ophthalmologists from 194 countries.Citation45 It is important to note that the data obtained from this study does not reflect what proportion of those ophthalmologists are surgically active. Their survey indicates an increase in the number of ophthalmologists by 14% globally. The workforce seems to be growing at a rate of 2.6% per year, which is higher than their estimate of 1.2% growth rate calculated in 2010.Citation46 Despite this growth rate, it is still lagging behind the ageing population growth rate of 2.9%.Citation45 Unfortunately, disparities remain. There is a significant shortfall of ophthalmologists in low- and middle- income countries relative to their populations. In approximately 12% of low-income countries there seems to be a decreasing number of ophthalmologists.Citation45 More worryingly, these regions have the lowest ophthalmologist density and the highest population growth rates. For example, Sub-Saharan Africa remains to have one of the lowest rates of ophthalmologists per capita, with 2.7 per million population. Other regions that had high rates of vision loss and fewer ophthalmologists included South Asia, and Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Oceania. Interestingly, there was a weak correlation between the ophthalmologist density and the prevalence of blindness. This is surprising as it was generally accepted that a higher density was critical to coverage. There was also a weak correlation between the number of ophthalmologists and cataract surgery rates. This is thought to be due to that fact that the number of ophthalmologists nationally does not reflect the distribution of ophthalmologists in the country i.e., most ophthalmologists are concentrated in urban areas and hence there are rural areas in the country where demands are not met. Hence, providing preventive cataract surgery on urban citizens with the means of affording intervention will not necessarily impact national prevalence of blindness. Therefore, number of ophthalmologists worldwide is a poor indicator of service provision and, in fact, masks the unequal distribution of ophthalmologists.

There is less literature on the number of optometrists and allied ophthalmic personnel. Data from the IAPB suggests that there remains very few optometrists relative to the population in Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, East Asia, Oceania, and South Asia.Citation16 Data on allied ophthalmic personnel is even more challenging as there is no internationally agreed definition on what constitutes this group. It can include orthoptists, ophthalmic assistants, and ophthalmic nurses. The IAPB states that there are critical human resource shortages for allied ophthalmic personnel, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Gender and vision impairment

Alongside the regional and socioeconomic disparities in vision health, there are gender disparities that remain persistent since the inception of Vision 2020.Citation47 Data from the VLEG on the global prevalence of blindness showed that overall, women bore a greater burden of vision impairment compared to men.Citation8 Statistics from the VLEG show that the prevalence of age-standardised blindness reduced by 25.4% in adult women compared to 32.9% in adult men in 2020. Age-standardized prevalence of blindness and vision impairment were greater for women due to cataract, under corrected refractive error, age-related macular degeneration, and diabetic retinopathy, greater only for men due to glaucoma.Citation8 Overall, women are 8% more likely to be blind, 15% more likely to suffer from MSVI and 12% more likely to have mild vision impairment.Citation8

The relationship between blindness and gender is complicated and remains unknown. Doyal and Das-Bhaumik proposed two potential causes.Citation48 The first is a biological theory that proposes that women have a greater susceptibility to eye conditions leading to blindness. This is separate to the theory that women have a longer average life expectancy than men (and we know that many of the common eye conditions are associated with ageing). The second cause relates to social perceptions that may vary across different regions and relate to factors such as roles of females in childcare and domestic tasks.Citation48 This disparity in gender is likely exacerbated in areas where resources and service provision are limited, and socioeconomic status is lower. In these situations, there may be preferential treatment of males to maintain household income.Citation48 Ye et al. evaluated 16 studies with 135, 972 subjects and found that females in South Asia have a significant barrier to access cataract surgery.Citation49 They calculated that vision impairment from unoperated cataract could be reduced by over 6% if gender disparities in access to surgery were eliminated. Similarly, Lewallen et al. had previously estimated that if men and women receive that same rate of cataract surgery then this would reduce severe vision impairment rates by around 11% in low- and middle- income countriesCitation50

Raising awareness of this issue, improving education, and enhancing transparency of data are key in ensuring we monitor and decrease these discrepancies in the future. Additional studies are needed to understand the reasons for these sex disparities, particularly in more complex and less easily treatable conditions like diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, and AMD.

Conclusion

Blindness and vision impairment have profound human and socioeconomic consequences. Addressing avoidable vision impairment can close the economic, social, and health inequalities face by individuals and families experiencing vision loss. Vision 2020 was an important initiative in spurring a global effort in response to the global burden of avoidable blindness. Vision 2020 has been key to raising awareness of the priorities for eye health, supporting national eye care plans and prevention of blindness programmes as well as encouraging for research in the field. Undeniably, milestones in eye care have been achieved through Vision 2020.

The efforts of Vision 2020 have resulted in increased funding through governmental and non-governmental sources that are instrumental to the elimination of avoidable causes of blindness. It has been pivotal in gaining and unifying advocacy for eye health at an international and national level. The reduced rates of age-related blindness globally are encouraging of the efforts of Vision 2020. However, there is an overall increase in crude prevalence, and this points to the need for a significant upscaling of efforts. The growing population and demographic shifts will present huge challenges in efforts to minimise vision impairment. To achieve the aims of Vision 2020, there will need to be significant up-scaling of current programmes, increased education, and better reporting of outcomes to better target care. There needs to be continued focus on areas of the world where the magnitude of vision loss is the worst and the resources available are minimal. There will need to be an increased focus to tackle the burden of NCED that will increase owing to epidemiologic shifts that have already taken place in high-income countries but are also encroaching on low- and middle-income countries. The recent COVID-19 pandemic may have an impact on achieving elimination of avoidable blindness as a public health problem, but it is difficult to say what these may be currently. Undoubtedly, Vision 2020 has led to huge milestones in the way we perceive the importance of eye care and our approaches to providing eye care. However, as can be seen from the most recent data on vision we have a while to go.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- The International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness. VISION 2020. (2020).

- Assi L, Rosman L, Chamseddine F, et al. Eye health and quality of life: an umbrella review protocol. BMJ Open. 2020;10(8):e037648. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037648.

- Thylefors B. A global initiative for the elimination of avoidable blindness. Community Eye Heal. 1998;11:1–3.

- Thylefors B, Negrel AD, Pararajasegaram R, Dadzie KY. Global data on blindness. Bull World Health Organ. 1995;73:115–121.

- Pizzarello L, Abiose A, Ffytche T, et al. VISION 2020: the right to sight - A global initiative to eliminate avoidable blindness. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):615–620. doi:10.1001/archopht.122.4.615.

- Frick KD, Foster A. The magnitude and cost of global blindness: an increasing problem that can be alleviated. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135(4):471–476. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(02)02110-4.

- World Health Organization. Global Initiative for the Elimination of Avoidable Blindness. World Health Organization; 2000.

- Bourne R, Steinmetz JD, Flaxman S, et al. Trends in prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment over 30 years: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob Heal. 2021;9(2):e130–e143. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30425-3.

- Foster A. Vision 2020: the cataract challenge. J Community Eye Heal. 2000;13:17–19.

- Foster A. Cataract and ‘Vision 2020 - The right to sight’ initiative. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85(6):635–637. doi:10.1136/bjo.85.6.635.

- Allen D, Vasavada A. Cataract and surgery for cataract. Bmj. 2006;333(7559):128–132. doi:10.1136/bmj.333.7559.128.

- Ramke J, Gilbert CE, Lee AC, Ackland P, Limburg H, Foster A. Effective cataract surgical coverage: an indicator for measuring quality-of-care in the context of universal health coverage. PLoS One. 2017;12,(3):e0172342. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172342.

- Wang W, Yan W, Fotis K, et al. Cataract surgical rate and socioeconomics: a global study. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(14):5872–5881. doi:10.1167/iovs.16-19894.

- Lou L, Wang J, Xu P, Ye X, Ye J. Socioeconomic disparity in global burden of cataract: an analysis for 2013 with time trends since 1990. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;180:91–96. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2017.04.008.

- Lewallen S, Schmidt E, Jolley E, et al. Factors affecting cataract surgical coverage and outcomes: a retrospective cross-sectional study of eye health systems in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Ophthalmology. 2015;1:1–8.

- The International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness. National indicators. https://www.iapb.org/learn/vision-atlas/solutions/national-indicators/ (2022).

- Yan W, Wang W, van Wijngaarden P, Mueller A, He M. Longitudinal changes in global cataract surgery rate inequality and associations with socioeconomic indices. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2019;47(4):453–460. doi:10.1111/ceo.13430.

- Wang W, Yan W, Müller A, He M. A global view on output and outcomes of cataract surgery with national indices of socioeconomic development. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58(9):3669–3676. doi:10.1167/iovs.17-21489.

- West SK. Milestones in the fight to eliminate trachoma. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2020;40(2):66–74. doi:10.1111/opo.12666.

- World Health Organization. Trachoma. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/trachoma (2022).

- Lietman TM, Pinsent A, Liu F, Deiner M, Hollingsworth TD, Porco TC. Models of trachoma transmission and their policy implications: from control to elimination. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(suppl_4):S275–S280. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy004.

- Ackland P. The accomplishments of the global initiative VISION 2020: the right to sight and the focus for the next 8 years of the campaign. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2012;60(5):380–386. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.100531.

- World Health Organization. 2015. African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control. World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. Onchocerciasis. 2019. World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. Onchocerciasis. 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/onchocerciasis Accessed 27 08 2022

- Etya’alé D. Eliminating onchocerciasis as a public health problem: the beginning of the end. British J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(8):844–846. doi:10.1136/bjo.86.8.844.

- Opoku NO, Bakajika DK, Kanza EM, et al. Single dose moxidectin versus ivermectin for Onchocerca volvulus infection in Ghana, Liberia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo: a randomised, controlled, double-blind phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10154):1207–1216. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32844-1.

- Gebrezgabiher G, Mekonnen Z, Yewhalaw D, Hailu A. Reaching the last mile: main challenges relating to and recommendations to accelerate onchocerciasis elimination in Africa. Infect Dis Poverty. 2019;8(1):1–20. doi:10.1186/s40249-019-0567-z.

- Gilbert CE, Anderton L, Dandona L, Foster A. Prevalence of visual impairment in children: a review of available data. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1999;6(1):73–82. doi:10.1076/opep.6.1.73.1571.

- Gillbert C, Muhit M. Twenty years of childhood blindness: what have we learnt? Community Eye Heal J. 2008;21:46–47.

- Gilbert C, Lepvrier-Chomette N. Chapter 50 Worldwide causes of childhood blindness. Pediatric Retina 3rd. In: Hartnett, Mary E. Wolters Kluwer. 2020;1088.

- Gilbert C, Awan H. Blindness in children. Br Med J. 2003;327(7418):760–761. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7418.760.

- Bourne RRA, Stevens GA, White RA, et al. Causes of vision loss worldwide, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Heal. 2013;1(6):e339–e349. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70113-X.

- Bourne R, Adelson J, Flaxman S, et al. Trends in prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment over 30 years and contribution to the global burden of disease in 2020. SSRN Electron J. 2020;9:e130–143.

- Holden BA, Fricke TR, Wilson DA, et al. Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(5):1036–1042. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.006.

- Rao G. The achievements and lasting effects of VISION 2020. Eye News. (2020).

- Zondervan M, Walker C, Astbury N, Foster A. VISION 2020 LINKS Programme: The contribution of health partnerships to reduction in blindness worldwide. Eye News.2014;20(6):32–6.

- Astbury N, Burgess P, Foster A, Mabey D, Zondervan M.Tackling Diabetic Retinopathy Globally through the VISION 2020 LINKS Diabetic Retinopathy Network. Eye News.2017;23(5):30–4.

- United Nations. World Population Prospects 2022. (2022).

- Bourne RRA, Steinmetz JD, Saylan M, et al. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: the right to sight: an analysis for the global burden of disease study. Lancet Glob Heal. 2021;9(2):e144–e160. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30489-7.

- McCracken K, Phillips DR. Demographic and epidemiological transition. Int Encycl Geogr People, Earth, Environ Technol People, Earth, Environ Technol. 2016;12:1–8.

- Resnikoff S, Kocur I. Non-communicable eye diseases: facing the future. Community Eye Health Journal. 2014;27:41–43.

- Zhang Y, Jin G, Fan M, et al. Time trends and heterogeneity in the disease burden of glaucoma, 1990-2017: a global analysis. J Glob Health. 2019;9,(2). doi:10.7189/jogh.09.020436.

- Xu X, Wu J, Yu X, Tang Y, Tang X, Shentu X. Regional differences in the global burden of age-related macular degeneration. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):410. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-8445-y.

- Resnikoff S, Lansingh VC, Washburn L, et al. Estimated number of ophthalmologists worldwide (International Council of Ophthalmology update): will we meet the needs? Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104(4):588–592. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2019-314336.

- Resnikoff S, Felch W, Gauthier TM, Spivey B. The number of ophthalmologists in practice and training worldwide: a growing gap despite more than 200 000 practitioners. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(6):783–787. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-301378.

- Abou-Gareeb I, Lewallen S, Bassett K, Courtright P. Gender and blindness: a meta-analysis of population-based prevalence surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2001;8(1):39–56. doi:10.1076/opep.8.1.39.1540.

- Doyal L, Das-Bhaumik RG. Sex, gender and blindness: a new framework for equity. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2018;3(1):e000135. doi:10.1136/bmjophth-2017-000135.

- Ye Q, Chen Y, Yan W, et al. Female gender remains a significant barrier to access cataract surgery in South Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Ophthalmol. 2020;(2020). doi:10.1155/2020/2091462.

- Lewallen S, Mousa A, Bassett K, Courtright P. Cataract surgical coverage remains lower in women. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(3):295–298. doi:10.1136/bjo.2008.140301.