Abstract

The dialogic nature of human beings has widely been argued in the scientific literature. Language, as a cultural and psychological tool, has the potential to construct social meanings, including those related to love, attraction and desire. In these emotional dimensions of the self, people use ‘the language of desire’, defined as the capacity of language to raise attraction and be desired, while the ‘language of ethics’ is used to describe what is ‘good’ and ‘ethical’. This article examines a dialogic intervention with 11–13-year-old children named Dialogic Literary Gatherings and explores its affordances to articulate both forms of language toward nonviolent models. 28 sessions from two elementary schools were analyzed, along with three focus groups with students. Main findings outline that dialogic features enable the emergence of the language of desire in combination to the language of ethics toward nonviolent relationships.

Language is the main tool through which human beings interact and exist in society. It allows us to learn, to go further and deeper in thought, learning and development (Bruner Citation1996; Vygotsky Citation1978). There is a wide spectrum of discourses and ways in which people communicate to construct realities and those can either perpetuate oppression or transform our relationships into more egalitarian and democratic ones (Freire Citation1997, Citation2018). Hence, the discourses in which people are socialized shape our thoughts, values and world views. Especially important are those discourses related to love, desire and attraction in early adolescence since they will play a critical role in their socialization toward egalitarian or violent relationships (Gómez Citation2015). In particular, research has shown the existence of what has been defined as a coercive dominant discourse. This discourse, which establishes a link between attraction and violence, might affect young people’s socialization leading toward engaging in power or violent relationships (Puigvert et al. Citation2019; Racionero-Plaza et al. Citation2018). Under the influence of such discourse, many of the messages youth receive and produce can be articulated under two categories defined as the language of desire (LoD) – referred to the capacity [of language] to raise attraction and be desired – and the language of ethics (LoE) – language form used to describe values (Gómez Citation2015; Flecha, Puigvert, and Rios Citation2016). These forms, used in everyday interactions, are not binary opposites nor universal concepts which are always separated. In the construction of sexual-affective relationships, these forms of language emerge and intertwine in a social context where our understanding of gender is changing and rapidly evolving from two traditionally accepted categories of femininities and masculinities. Moreover, LoD and LoE are not attached to a single gender conception or sexual orientation, nor do they only exist within traditionally accepted categories of femininities and masculinities.

Nonetheless, the above mentioned coercive dominant discourse promotes among many adolescents the use of LoD toward violent models and relationships portraying them as fun and exciting, whereas the LoE is often used in educational contexts by teachers or parents to describe those representing ethical values and relationships as good or convenient (Flecha, Puigvert, and Rios Citation2016; Puigvert et al. Citation2019). However, the latter are often perceived by youth as moralistic and lacking attractiveness. Consequently, this discourse socializes many adolescents and youth in associating violence with attraction (Flecha Citation2015).

Given the power interactions underlying the coercive discourse and its affection in many adolescents’ socialization, interventional work needs to be done from schools at an early age to provide students with spaces where they can develop alternative, transformative interactions to act as critical thinkers and transformative human beings (Freire and Macedo Citation1987). Indeed, dialogue serves as the means through which these alternative interactions and relationships can be created. In Freire’s (Citation2018) words, ‘[dialogue] is an act of creation; it must not serve as a crafty instrument for the domination of one person by another (…) it is conquest of the world for the liberation of humankind’ (p. 89). Hence, dialogue can elicit liberating forms of language through which students can critically reflect on what behaviors are portrayed as attractive in their discourses with their peers.

In this vein, this study addresses this challenge by analyzing in depth a dialogic space named Dialogic Literary Gatherings (DLG), a dialogue-based educational intervention conducted with 6th grade students from two schools located in two deprived, low socioeconomic status neighborhoods surrounding Barcelona (Spain). This interventional work, where students engage in a collective interpretation of a classic literary text previously read, is especially relevant in such contexts where students might have fewer rich interactions that equip them with the skills and tools to reflect critically on their preferences and relationships. Indeed, it is especially significant to analyze this intervention in early adolescence, since this developmental stage is particularly important for their identity formation (Løhre Citation2020) and they start to differentiate between acquaintance or friend and sexual, intimate or dating partner (Cascardi et al. Citation2018). Thus, this study sets forth a pathway toward the exploration of DLG as an educational intervention that tackles dialogue as an opportunity in early adolescence to potentially convey transformative discourses that can challenge a coercive dominant discourse by engaging in critical reflections in which LoD may emerge toward nonviolent models and relationships.

In the following sections, an overview on language as a tool to construct attraction and desire is offered. Next, the dialogic features and functioning of DLG are reviewed. The methodology and analysis conducted in the two case studies are presented, followed by a discussion on the results achieved. Finally, limitations and conclusions of this study are acknowledged.

Language in the construction of attraction and desire

Love, desire and attraction are among the socially constructed concepts acquired through interaction with others in a situated social and cultural context (Gómez Citation2015). Vygotsky’s theory of thought and language (Vygotsky Citation1978) presents language as a cultural and psychological tool, since its capacity to communicate cannot be separated from the social and cultural context in which communication takes place. Through the concept of inner speech, defined as the internal reconstruction of an external operation (Vygotsky Citation1978, p. 56), Vygotsky explains how language and thought interconnect, allowing the development of higher order mental functions. Because of the interactive nature of human beings, the internal representation of thought includes cultural manifestations constructed in interpersonal communicative exchanges. Accordingly, any concept integrated in an individual’s mind has been constructed in a social process through language.

Drawing on the analysis of how people link attraction with feelings of desire and goodness through language, Flecha and colleagues (2013, p. 100) define the concept of the language of desire (LoD) as the capacity [of language] to raise attraction and be desired. Adjectives such as ‘sexy’ or ‘exciting’ are often used in conversations to express desire. Following this idea, further research on the coercive dominant discourse has revealed that many female teenagers living in different countries and contexts use LoD to express attraction toward less egalitarian masculinities (Puigvert et al. Citation2019). In addition to LoD, the language of ethics (LoE) is used to describe what is ‘good’ and ‘ethical’. This language is primarily used in everyday life interactions within educational contexts by teachers or parents when discussing youth’s relationships (Flecha, Puigvert, and Rios Citation2016; Rios-González et al. Citation2018). Indeed, many parents and teachers, when trying to educate children and adolescents in nonsexist ways, talk about dominant and violent partners as ‘not good nor convenient’, and they talk about ‘good men’ with no desirability (Flecha, Puigvert, and Rios Citation2016).9The often separation of LoE and LoD shows that the detachment of the ethics and esthetic dimensions leads to language double standards: ‘good’ and ‘nice’ partners are portrayed as ‘convenient’, while dominant partners are seen as ‘thrilling’ and ‘desirable’ (Flecha, Puigvert, and Rios Citation2016). Instead, dialogic interactions (Soler and Flecha Citation2010), based on consensus and on lack of coercion, promote critical reflections on issues related to love and attraction, among others, that may foster the link between desire and attraction toward nonviolent models (Racionero-Plaza et al. Citation2018). It is only through dialogue, which entails ‘mutual respect between the dialogic subjects’ and a critical stance among them (Freire Citation1997, p. 99), that adolescents can question the desire and attraction linked to violent models. Dialogic interactions offer students the opportunity to express their feelings together with reason, uniting ethics and esthetic dimensions. Through dialogues that defy power interactions, affordances to transform their language and, eventually, their social realities, can emerge (Gómez Citation2015).

In light of this evidence, it is imperative to provide students with dialogic spaces and activities that foster the use of LoD and LoE to express both preference toward egalitarian and nonviolent behaviors and relationships and rejection toward dominant and violent behaviors and relationships. Among the diversity of dialogic interventions, the Dialogic Literary Gatherings (DLG) present an optimal opportunity for the development of desire attitudes and beliefs united with values and reasoning, as they are rooted in a transformative and emancipatory approach to co-create new realities (Flecha Citation2000, Freire Citation2018).

The interactive potential of DLG for the emergence of LoD linked with LoE

DLG are an educational intervention aimed at collectively interpreting literary classics. They are currently being implemented in over 6000 schools in Europe and South America, with students from kindergarten to adult education. Participants in DLG choose a classics book and agree on the pages to read. During the gathering, they share their thoughts on the reading in an egalitarian dialogue and collectively create meaning around the topics which have been elicited. In this context, all voices are heard based on validity claims rather than on power interactions, and new knowledge is constructed from an in-depth integration of all contributions (Flecha Citation2015). DLG draw from the understanding that social interaction in an egalitarian context allows for the collective creation of meaning, leading to the transformation and creation of new realities where attitudes of solidarity, respect and equity thrive (Flecha Citation2015). Indeed, DLG can be considered a ‘situated genre’ (Fairclough Citation2003), since during their development a specific context of interaction is created, based on the principles of egalitarian dialogue, collective creation of knowledge and solidarity (Llopis et al. Citation2016). Under this perspective, reading comprehension is regarded as well as an intersubjective process mediated by language, since participants share their thoughts on the readings and build understanding on each other’s contributions (Soler Citation2015). Besides, DLG offer a particularly interactive context, since the proportion of children talk during this activity dramatically increases in relation to that of the average class, with children utterances being longer in words and richer in content (Hargreaves and García-Carrión Citation2016). These authors also show that more children usually participate in DLG than in the regular classroom, building on each other’s contributions, rather than just intervening.

DLG have already demonstrated to foster deep reflection and critical thinking linked to prosocial behavior (Villardón-Gallego et al. Citation2018). Children in DLG create meaning together when reading and discussing the most precious universal literary creations and do so not only using conceptual knowledge, but also dealing with emotions and values. Reading literary classics in DLG fosters the discussion of topics of utmost relevance, as well as higher degrees of development. Some studies on classic literature show the influence that reading ‘The Arabian Nights’ at a young age has had for different English writers of the 19th century, such as Charles Dickens, Charlotte and Emily Brontë, Robert Louis Stevenson, as well as for their works (Styles Citation2010). Another study by Keidel and colleagues (2013) showed that reading Shakespeare activated more brain areas than reading common literary pieces, fostering higher-order thinking. Thus, in the DLG about universal issues such as love, death and life, beyond the meaning of words themselves, participants create new realities through their interactions, which transform the way in which they see the world and act in it.

Drawing from the characteristics which define DLG, such as an egalitarian dialogue (Flecha Citation2015) that enhances prosocial behavior (Villardón-Gallego et al. Citation2018) and allows personal and collective transformation (Soler Citation2015), we hypothesize that this educational action could promote the use of LoD together with LoE toward nonviolent models and egalitarian relationships.

Materials and methods

Design

This study has been designed as a case study (Stake Citation1995), with the aim to gain insights on the educational actions that take place in schools which show outstanding improvements, School 1 (S1) and School 2 (S2). Two data sources have been used: participatory observations of DLG and focus groups with DLG participants.

The present study is framed within the Communicative Methodology of Research, which relies on the potential of dialogue to transform social realities (Gómez et al. Citation2019). Within this communicative paradigm, researchers, who bring scientific knowledge, and participants, who contribute their cultural intelligence, engage in an egalitarian dialogue in order to reach in-depth understandings of social problems and propose new solutions. The outcomes are, in turn, validated by the participants who have been involved in the entire research process. The added value of this methodological approach to achieve social and policy impact has been underlined in high-relevance European research projects (European and European Commission Citation2011).

Selection of case studies

Two schools implementing research-based educational actions, including DLG, were selected for this study. S1 is located in one of the most socioeconomically complex neighborhoods in Barcelona’s metropolitan area. 95% of students have meal grants and 92% come from 28 different nationalities. S1 started implementing DLG in 2009–2010 and reversed its low results in 2015–2016, scoring above the Catalan average in standardized testing.

S2 is located in one of the poorest neighborhoods at the suburbs of Terrassa, near Barcelona. It has a 98% student diversity, with many students from unstructured families and at risk of social exclusion. After implementing DLG, among other research-based educational interventions, the number of students achieving a higher level in reading comprehension in standardized testing went from 17% to 85%.

Participants

113 students from S1 and S2 participated in the study. They were divided in 5 groups as follows:

S1 participants belonged to two 6th grade groups (11–13 years old) in the school year 2016–2017 and two 6th grade groups (11–12 years old) in the school year 2017–2018. Participants from School 2 belonged to a 6th grade group (11–12 years old) in the school year 2016–2017. shows the characteristics of the sample.

Table 1. Participants.

Procedure

One of the researchers conducted participatory observations of 28 DLG sessions with all the groups (see ). Students in S1 read and discussed an adaptation of Shakespeare’s play ‘Romeo and Juliet’ translated to Catalan. Participants at S2 read and commented a Spanish adaptation of ‘The Iliad’, a Greek epic from the 8th century BC written by Homer. For DLG sessions, students previously read at home the pages they had agreed upon and then wrote down in a notebook extracts for the debate, together with a short reflection. In class, they discussed such extracts in an egalitarian dialogue with their peers. The role of the teacher during the activity was that of the moderator.

Table 2. Observations.

In addition, children’s voices were included through three focus groups conducted after the DLG sessions: 2 focus groups with students from S1 in 2016–2017 and 1 focus group with girls in S2. The aim was to deepen in some aspects that emerged during DLG. Both the observations and the focus groups took place at the corresponding schools and data was either audio recorded and transcribed or gathered through observations and notes taken by the researcher. A teacher was present during the focus group held at S2 and during the one with 6thB at S1, but not during the focus group held with some girls from 6thB at S1. Neither participants nor teachers had the focus group questions beforehand.

The researchers in this study had already met with the staff at both schools for previous studies. Once schools agreed to participate, teachers and families were informed of the nature and purpose of the study, of participation being anonymous and voluntary, and of data only being used for the purpose of the study. This information was included in the written consents. In S1, parental informed written consents were given to the principal’s office during the academic years 2016–2017 and 2017–2018. Afterwards, the principal and the DLG teachers gave their informed written consents for the study to be carried out in both 6th grade groups. At S2, parental informed written consents were obtained for all students in 6th grade to participate during the academic year 2016–2017. The principal and the DLG teacher gave their informed written consents for the study to be carried out in 6th grade.

This study was conducted under the frame of the FP7 IMPACT-EV project (Flecha, Citation2014-2017), which followed the ethical requirements for conducting research in the European FP of Research. An ad hoc Ethics Committee of the IMPACT-EV project was established, which included three academics with expertise in Ethical Review Panels for national and international research. This Committee revised and fully approved the proposal and related ethics documents for participants.

Data analysis

Data analysis was an ongoing process during the data collection phase, which involved continual reflection, discussion and interpretation among researchers (Creswell Citation2009). All recorded focus groups and DLG sessions were transcribed and ordered into student utterances and analyzed together with the notes of the observations. Once the transcripts were finished, they were read through several times together with the observations’ notes by each researcher. Data analysis both of the DLG sessions and of the focus groups was conducted at the utterance level, rather than as a social interactional practice. Subsequently the bodies of data divided into utterances were classified in different categories. Initial categories were defined by consensus between researchers, after identifying those coming up in the dialogues about relationships and taking into account the previous literature about DLG. Initially, three broader categories were established: values, attitudes, behaviors. For each of these, two dimensions were considered: nonviolent relationships and violent relationships ():

Table 3. Emerging categories.

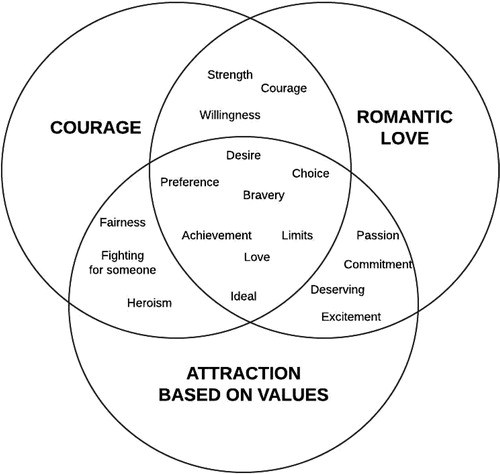

Once data were classified upon these categories, we focused on deepening in the analysis of those dialogues linked to nonviolent relationships, and identified those moments in which LoD emerged, looking at attributes—values, attitudes and behaviors—which reflect both dimensions, goodness and attractiveness. Three categories reemerged: romantic love, attractiveness based on values, and courage. We defined these specific categories as follows ():

Table 4. Categories of analysis.

Once the categories were defined, all the selected data were re-reviewed and sorted in the established categories by two of the researchers independently. Next, both categorizations were shared and discussed. The extracts that rose any disagreements between the researchers were discussed and final categorization was decided upon consensus.

Results

The analysis of the gathered data shows the presence of LoD and LoE toward nonviolent relationships during DLG discussing ‘Romeo and Juliet’ and ‘The Iliad’. 132 utterances were selected. This evidence was classified in three categories: romantic love (35%), attractiveness based on values (46%), and courage (19%) (see ).

Romantic love

Romantic love, which is based on equality and feelings, is a common topic in the literary classics. Romeo and Juliet’s unconditional love for each other is one of numerous literary cases of romance. Students’ dialogue about love is prompted by the text but freely and openly led by them. As such, they relate love with strength, willingness or courage. From the utterances selected for analysis, 46 utterances out of 132 (35%) were related to romantic love through the combination of LoE and LoD. Some examples of the dialogues are presented below:

P6: [after sharing a piece in which Juliet tells her dad that love will give her enough strength] Juliet’s statement makes me think of courage. I would not dare

P7: I don’t think it is only love, but also effort and willingness, or whatever else. I don’t understand why she talks about love; I don’t think love is for everyone, it could be anything else.

P8: I think that love refers to Romeo. Romeo gives her enough strength

P9: if you fight you will get what you want

P8: I believe that love and willingness go together. If you have love and willingness inside yourself, you can achieve anything. If you commit to something and you love it, that is love, and you are willing to do it

P10: that is passion, to like doing something

In this extract P6 uses the term courage to vindicate the power of romantic love. Love is what gives Juliet the strength to fulfill her destiny and therefore is presented, through LoD, as something worth considering. The conversation continues and P8 intervenes to share his understanding about Juliet saying ‘love’, but actually referring to ‘Romeo’, which could be understood as Romeo being her source of strength. This idea further evolves, and students discuss that love and willingness go together and that this is actually the key to achieving anything. Finally, P10 resolves with enthusiasm that loving something and being willing to do it is what passion is about. In their contributions, participants value romantic love by using LoD to describe it in terms of empowerment, will and passion, in addition to ethical descriptions. Talking about romantic love in such terms makes this type of relationships desirable and, eventually, it might contribute to addressing the dichotomy between passion and love.

In the following dialogue, LoD emerges related to love.

P11: I would not care about our families fighting between them, I would fight for him

P12: I don’t care about the family. If I love her, I would be with her

P13: I would leave him, it’s not worth it to suffer over a boy

P12: if you love him it’s not the same

P14: some say that they would forget about it, but I don’t believe it’s that easy to forget the guy you love

P11: I would start as a friend, and if I see that he is still interested I would give him an opportunity. If he doesn’t deserve me, then I wouldn’t

P14 & P12: first you need to be friends

In this episode children add value to the ethical dimension of romantic love by describing it with LoD as something worth fighting for. They comment that they would confront their families if necessary, in order to be with their love. Moreover, those who advocate for it try to tell the others how powerful and deep it is to fall in love with someone. However, P11, P12 and P14 also agree on the fact that before falling in love with someone this way, they would get to know that person and be friends before making a decision. Besides, P11 adds that she would not give an opportunity to someone that does not deserve her. These utterances show that in the discussions elicited by the reading of the literary classics, LoD is used to describe nonviolent relationships. During DLG children refer to these in terms that raise attraction, while they portray as unattractive anything that trespasses the established limits of what is acceptable in a relationship.

Finally, in the last dialogue, participants discuss with deep excitement about love and happiness, as two feelings that go together:

P15: it’s the most realistic book that I have seen

P16: the excitement!!!!

P17: there are all kinds of people. There are couples who are fine and are happy

P18: the book gives a different perspective

P19: It can work out well… if you love her and she loves you and you treat each other well it can work fine

P20: actually, that’s what love is for!!

In this last extract participants use LoD to express how romantic love is the key to a successful relationship. P19 explains that if people in a couple love each other and treat each other well, the relationship can be successful, and they can reach happiness. Talking about happiness or success in romantic relationships or referring to how exciting these relationships are increases the attractiveness of such relationships because it portrays them as highly desirable. In fact, P20 defines love as the vehicle to reach happiness and to enjoy being with your partner.

Attractiveness based on values

Who we consider attractive, or evaluating someone as attractive or not, is something present in everyday life, an element that emerges in teens’ conversations and which is continuously approached in teens magazines, TV and series or social networks, all of them powerful socializing agents (Gómez Citation2015; Rios-González et al. Citation2018). As expected, this is another issue that emerges during DLG, expressed in 61 out of 132 utterances (46%). The following extracts provide evidence of how during DLG LoD is used to make the character feel attractive:

P6: When you love someone who doesn’t love you back, why do you keep loving this person? Why don’t you let it go? Let it go, there are many other people! I don’t understand!

- […]

P21: What P6 is saying is happening to me. X is saying things to me all the time, and I don’t like it and I tell him to stop. He calls me ‘mamasita’ and I tell him ‘I am not your mamasita’

In this episode we see how LoD emerges in combination to LoE during discussion time and it is used both to render attractive nonviolent models and relationships, and to drive others away from bad relationships. Following this idea, one can observe that P6 starts by saying that people should let go of those who do not love them back. This statement empowers others to express and reflect on some relationships that do not make them feel comfortable. The LoD used in these interactions stresses out the idea that individuals have a choice. In addition, P21 clearly stands up to someone who is calling her names and she uses LoD to express her dissatisfaction and to stress that she does not belong to that person. Likewise, in the following dialogue a group of girls discusses the idea of the ‘perfect guy’ in relation to their past relationships:

P26: the first one I had did look alike because he listened to me. If I wasn’t well, he would make me laugh, so I felt better. It’s over because he loved someone else

P27: the first boy I fell in love with was a good guy. He was handsome, he paid attention to me, he treated me well. But the second one was handsome but didn’t listen to me, he mistreated me. I prefer the first one of course. Now I would choose the first one

P28: none of the guys I’ve been with looked like the ideal guy. They wouldn’t pay attention to me at all and whatever happened to me annoyed them. Now if they let me choose, I choose the ideal one

P30: I want someone like Romeo

DLG made girls reflect on their present and past relationships. In these utterances, they use LoD to express attraction toward positive relationships and partners and rejection toward violent models and relationships. P25 talks about good relationships (LoE) as being fun (LoD), and most participants recognize that now they would choose the ideal partner over someone that does not make them happy. As P30 reflects, these ideas come from Romeo’s way of being: he is seen as ideal because of his love for Juliet. Therefore, during the DLG girls reflect upon the idea that they can choose and that they actually want to choose the ‘ideal’ guy, which evidences the presence of LoD in combination with LoE toward nonviolent models and relationships.

Courage

Courage is a positive attribute highly linked with attraction and desire. Therefore, the use of such term to describe nonviolent models and relationships depicts that not only LoE is used, but also LoD, uniting goodness and attractiveness in the same person. Students’ discussions about the characters reflect their tastes and preferences. They reject violent models, such as Achilles, who mistreats women and has slaves. From the dialogues analyzed, 25 utterances out of 132 (19%) have been found linked to courage.

P1: if you tell me to choose between Achilles and Menelaus, I choose Menelaus (…) Yes, it’s better than being with Achilles

P2: ah, I would not choose either of them

P1: [I would not choose Achilles] because he is mean. He didn’t treat girls nicely, as if they were nothing

P3: that’s it, as if they were his slaves

As observed, P1 despises Achilles so much that she would rather choose Menelaus over him, and P2 would not choose either one of them. Therefore, in this case by saying that they would not choose him, LoD is being used to reject a violent model, which, in turn, brings closer the nonviolent one. However, it is relevant to observe in the following extract how the language used by the girls changes when they are asked about Hector:

Researcher: why do you like Hector?

P2: because he is brave […]?

because he fights well. And also, because he helps his family, he treats them well, he takes care of his children…

[…]

Researcher: who is the hero? Hector or Achilles

Girls: Hector

[…]

P2: because he is brave

P5: because he is brave and he has fought and faced up to everyone. He is brave. However, Achilles was immortal because he couldn’t be killed, only on the foot

[…]

Teacher: well I don’t know…, if you had to choose, who would you marry?

P1: Hector! […]

because he is good, brave and ever so handsome!

These girls describe Hector using LoD, emphasizing with enthusiasm positive characteristics about him and adding the esthetics to the ethical dimension of his character. P2 and P5 say that Hector is brave because he fights for those who he loves and treats them well, and P2 stresses out how he is someone who helps his family and cares for his children. As well on their side, P4 intervenes to say that she loves him. Moreover, the girls see Hector as an attractive guy, because they all agree on him being the hero. This way, terms such as brave, love or hero used when describing Hector reveal how the girls articulate LoD around a nonviolent partner in the context of the DLG.

Discussion

The emergence of LoD toward nonviolent partners and relationships during DLG

The analysis of students’ discourse shows that LoD toward nonviolent models and relationships emerged among preadolescents aged 11–13 when discussing ‘Romeo and Juliet’ and ‘The Iliad’ in the context of DLG. Particularly, our results show that this language was used in combination to LoE when discussing romantic love, attractiveness based on values and courage.

The dialogic interactions fostered by DLG led participants to collectively define what love means to them. They did not only draw their ideas from high quality literary pieces, which promote higher order thinking (Keidel et al. Citation2013), but also brought their own personal experience and built on each other’s thoughts. The egalitarian dialogues children exchange in DLG promote critical reflections about relationships which emerge in the context of classic literature. As seen before, the dialogic exchanges these children had around the book characters contributed to the creation of new realities and the transformation of existing ones (Flecha Citation2000; Freire Citation2018): LoD arouses in combination with LoE, leading to the collective construction of the attributes that render a character desirable. Indeed, as previously stated, the coercive dominant discourse influences their socialization into linking attractiveness to people with violent attitudes and behaviors, while nonviolent people and relationships are many times perceived as convenient but undesirable (Puigvert et al. Citation2019). Therefore, the fact that, during DLG, LoD toward nonviolent relationships emerges is of utmost relevance. These interactions contribute to the socialization of preadolescents in egalitarian relationships which show that love has nothing to do with pain, but with ‘will and passion’, as participants defined it. The fact that participants autonomously reach this conclusion is especially relevant because rather than coming from the outside as something imposed (for instance, by an adult), it comes from the inside as a collectively built meaning (Gómez Citation2015). The extent to which this can be a protective factor that might affect behavior remains, however, unexplored.

The second identified aspect refers to attractiveness based on values. Gómez (Citation2015) already pointed out that the traditional model of sexual-affective attraction-election, by separating the use of LoE from LoD, has detached passion from stability and tenderness, making it impossible to picture those who represent good values as attractive. In this scenario, attractiveness is frequently linked to non-egalitarian partners and relationships. However, our main findings point out that in the context of DLG, students focus on positive values, such as the willingness to defend the people they love when describing what makes them feel attracted to some characters like Hector. Thus, in the dialogic interactions that take place during DLG, participants collectively establish through the language they use that a desirable man must have values. The internalization of these socially constructed ideas (Vygotsky Citation1978) shapes the individual’s understanding of the world around them. In this line, DLG could be the tool through which participants can reflect on and collectively decide what is good and bad for them to then internalize an alternative nonviolent model and use it in their worldviews and daily lives (Yuste et al. Citation2014). Following this idea, Puigvert (Citation2016) has explored how through a variant of the DLG, the Dialogic Feminist Gatherings (DFG), female adolescents challenged the desire imposed by the coercive discourse. These interventions led them to redirect their feeling of attraction from violent to nonviolent partners. Similarly, in the discussions during DLG, participants shared their own memories and used LoD to reflect on them, opposing the coercive discourse by showing preference for nonviolent models. This idea is also related to the findings of Racionero-Plaza and colleagues (Citation2018), who show that the reconstruction of autobiographical memories by incorporating the knowledge created in DFG leads to more critical recalls of such memories, thus reducing the chances of repeating such behaviors in the future.

Finally, participants in DLG used LoD to describe attraction toward brave men. Indeed, courage is a trait that makes participants see Hector as attractive, even though other men in the discussion are defined as handsome too. This suggests that during the social interactions occurring in DLG, participants use and direct LoD toward partners and relationships that share better values (LoE), but without giving up attraction and passion. In line with Yuste et al. (Citation2014), using talk to collectively make meaning and construct knowledge about different masculine models can help participants reflect on what each model can offer and link attraction to those models that possess desirable traits.

Limitations and prospective

This small-scale study has explored the emergence of LoD together with LoE in two schools using two specific texts. This clearly raises several limitations that should be taken on in further studies. Regarding the design, it does not allow us to exactly determine whether and under which conditions the transformation of LoD occurs. While episodes analyzed contained dialogic features associated to the use of LoD toward positive relationships and values, there is not enough information to unveil the extent to which these dialogues have been prompted by the text or by the dialogic reading, or both. Another limitation is that data have been analyzed at the utterance level instead of at the interaction level. Analyzing the social interactional practices would have provided a richer and broader overview of the dialogic nature of DLG. Further research should account for capturing the dialogic interaction exchanges which characterize DLG.

Besides, the value of DLG as violence prevention tools should be further studied. DLG may potentially direct attraction toward romantic relationships and alternative models characterized by the union of egalitarianism, lack of violence and attractiveness (Flecha, Puigvert, and Rios Citation2016). This would allow the reconciliation of two key aspects for successful relationships. Moreover, they foster attraction through traits as bravery that have proven to be key in the overcoming of bullying and sexual harassment (Villarejo-Carballido et al. Citation2019). Last, further research should consider the limitations posed by the binary conception of gender used in this study in order to be more inclusive, by including, for instance, members of the LGBTIQ + community as research participants in order to contribute knowledge to LGBTIQ + research (Serrano Amaya and Ríos González Citation2019).

Conclusions

The present study has provided evidence of the emergence of LoD, in combination with LoE, toward nonviolent behaviors and relationships. This fact not only sheds new light on the particularities of language during this activity, but also contributes to the existing knowledge about DLG as an educational action leading to processes of personal and social transformation. More specifically, it opens up an unexplored field to further study the potential of DLG to prevent gender-based violence and other forms of harassment.

This study contributes to the transformative potential of language and to the impact of DLG by showing that when adolescents interact and exchange ideas through dialogic interactions on the topics that the literary classics elicit, the ethics and the esthetics dimensions of social reality are again reunited in a combined use of LoD and LoE. This provides adolescents with greater chances to reflect upon and understand the possibilities that language opens toward new worlds where relationships based on freedom and love are possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bruner, J.S. 1996. The Culture of Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Cascardi, M., C.M. King, D. Rector, and J. DelPozzo. 2018. “School-Based Bullying and Teen Dating Violence Prevention Laws: overlapping or Distinct?” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 33 (21): 3267–3297. doi:10.1177/0886260518798357.

- Creswell, J.W. 2009. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- European, Commission, European Commission 2011. Added value of Research, Innovation and Science portfolio. MEMO/11/520. - Press Corner. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_11_520

- Fairclough, N. 2003. Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research. London: Psychology Press.

- Flecha, R. 2000. Sharing Words: Theory and Practice of Dialogic Learning. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

- Flecha, R. 2014-2017. IMPACT-EV. Evaluating the Impact and Outcomes of European SSH Research. 7th Framework Programme of Research and Innovation. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission.

- Flecha, R. 2015. Successful Educational Actions for Inclusion and Social Cohesion in Europe. Berlin, Germany: Springer.

- Flecha, R., L. Puigvert, and O. Rios. 2016. “The New Alternative Masculinities and the Overcoming of Gender Violence.” International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences 5 (2): 113–183. doi:10.17583/rimcis.2016.2118.

- Freire, P. 1997. Pedagogy of the Heart. New York: The Continuum Publishing Company

- Freire, P. 2018. Pedagogy of the Oppressed (50th-Anniversary ed.). London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Freire, P., and D. Macedo. 1987. Literacy: reading the Word and the World. Connecticut: Bergin & Garvey.

- Gómez, J. 2015. Radical Love: A Revolution for the 21st Century. Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang.

- Gómez, Aitor, María Padrós, Oriol Ríos, Liviu-Catalin Mara, and Tepora Pukepuke. 2019. “Reaching Social Impact through the Communicative Methodology. Researching with Rather than on Vulnerable Populations: The Roma Case.” Frontiers in Education 4: 9. doi:10.3389/feduc.2019.00009.

- Hargreaves, L., and R. García-Carrión. 2016. “Toppling Teacher Domination of Primary Classroom Talk through Dialogic Literary Gatherings in England.” FORUM 58 (1): 15–25. doi:10.15730/forum.2016.58.1.15.

- Keidel, J.L., P.M. Davis, V. Gonzalez-Diaz, C.D. Martin, and G. Thierry. 2013. “How Shakespeare Tempests the Brain: neuroimaging Insights.” Cortex; a Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior 49 (4): 913–919. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2012.03.011.

- Llopis, A., B. Villarejo, M. Soler, and P. Alvarez. 2016. “(Im)Politeness and Interactions in Dialogic Literary Gatherings.” Journal of Pragmatics 94: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2016.01.004.

- Løhre, A. 2020. “Identity Formation in Adolescents with Concentration Problems, High Levels of Activity or Impulsiveness: A Pragmatic Qualitative Study.” International Journal of Educational Psychology 9 (1): 1–23. doi:10.17583/ijep.2020.4315.

- Puigvert, L. 2016. “Female University Students Respond to Gender Violence through Dialogic Feminist Gatherings.” RIMCIS. International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences 5 (2): 183–203. doi:10.17583/rimcis.2016.2118.

- Puigvert, L., L. Gelsthorpe, M. Soler-Gallart, and R. Flecha. 2019. “Girls’ Perceptions of Boys with Violent Attitudes and Behaviours, and of Sexual Attraction.” Palgrave Communications 5 (1): 56. doi:10.1057/s41599-019-0262-5.

- Racionero-Plaza, S., L. Ugalde-Lujambio, L. Puigvert, and E. Aiello. 2018. “Reconstruction of Autobiographical Memories of Violent Sexual-Affective Relationships through Scientific Reading on Love: A Psycho-Educational Intervention to Prevent Gender Violence.” Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1996. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01996.

- Rios-González, O., J.C. Peña Axt, E. Duque Sánchez, and L. De Botton Fernández. 2018. “The Language of Ethics and Double Standards in the Affective and Sexual Socialization of Youth. Communicative Acts in the Family Environment as Protective or Risk Factors of Intimate Partner Violence.” Frontiers in Sociology 3: 19. doi:10.3389/fsoc.2018.00019.

- Serrano Amaya, J.F., and O. Ríos González. 2019. “Introduction to the Special Issue: Challenges of LGBT Research in the 21st Century.” International Sociology 34 (4): 371–381. doi:10.1177/0268580919856490.

- Soler, M. 2015. “Biographies of “Invisible” People Who Transform Their Lives and Enhance Social Transformations through Dialogic Gatherings.” Qualitative Inquiry 21 (10): 839–842. doi:10.1177/1077800415614032.

- Soler, M., and R. Flecha. 2010. “Desde Los Actos de Habla de Austin a Los Actos Comunicativos: Perspectivas Desde Searle, Habermas y CREA.” Revista signos 43(Suppl. 2), 363–375. doi:10.4067/S0718-09342010000400007.

- Stake, R.E. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Styles, M. 2010. “Learning through Literature: The Case of the Arabian Nights.” Oxford Review of Education 36 (2): 157–169. doi:10.1080/03054981003696663.

- Villardón-Gallego, L., R. García-Carrión, L. Yáñez-Marquina, and A. Estévez. 2018. “Impact of the Interactive Learning Environments in Children’s Prosocial Behavior.” Sustainability 10 (7): 2138. doi:10.3390/su10072138.

- Villarejo-Carballido, B., C.M. Pulido, L. de Botton, and O. Serradell. 2019. “Dialogic Model of Prevention and Resolution of Conflicts: Evidence of the Success of Cyberbullying Prevention in a Primary School in Catalonia.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (6): 918. doi:10.3390/ijerph16060918.

- Vygotsky, L.S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Mental Process. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Yuste, M., M.A. Serrano, S. Girbés, and M. Arandia. 2014. “Romantic Love and Gender Violence: Clarifying Misunderstandings through Communicative Organization of the Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 20 (7): 850–855. doi:10.1177/1077800414537206.