Abstract

Nonfiction has long been left out of the discourse on literacy and little is known about the affective experiences that children seek when they choose to engage with facts via reading and otherwise. We have conducted an interview study in which children of diverse socioeconomic backgrounds in Czechia (N = 20, age 9–11) reflected on the world of facts as a springboard for affective engagement. Bespoke creative props were developed for the study. First, children made collages of their real-world interests and then reflected on the different activities (e.g. reading, viewing, talking, playing) through which they nurture these interests. Second, children engaged in the design of an imaginary nonfiction book on a topic of their choosing, a process that involved laying out a double page, leafing through sample books, and sorting picture cards representing different book design features. We present the interview toolkit and its holistic rationale and offer two contrasting case studies of children whose engagement was characterised respectively by a ‘learning’ and ‘wonder’ focus. Their differences showcase the interview toolkit’s flexibility for further research and practice and expose the underexplored complexity and diversity of children’s nonfiction experience.

Introduction

While the common idea of a strong reader is a lover of fiction (Mackey Citation2020; McGeown, Bonsall, Andries, Howarth, Wilkinson, and Sabeti Citation2020), children’s nonfiction publishing has skyrocketed over the past two decades (Merveldt Citation2018; Grilli Citation2020a). Yet there is little systematic insight into the affective experiences, or pleasures, that children seek in their engagements with facts. A pervasive understanding of nonfiction reading is that it gives access to an affectless ‘world of hard facts’ (Moss Citation1999, p. 508). This traditional separation of fact and affect is also reflected in literacy assessment tools such as the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS); as part of its Students Like Reading metric (Mullis et al. Citation2023), PIRLS distinguishes between reading ‘for fun’ vs. reading ‘to find out about things I want to learn’ (IEA Citation2020, p. 15) as if the two purposes stood in mutual opposition.

To further a more nuanced understanding of factual reading that can potentially support pedagogy across subjects, we have conducted in-depth interviews exploring children’s affective engagement with facts generally and nonfiction reading specifically. Following contemporary trends in research with children across disciplines, our interview design was child-centred (Montreuil et al. Citation2021) and employed creative tangible props (Kortesluoma et al. Citation2003; Punch Citation2007). A holistic perspective was adopted at the outset, exploring volitional reading as naturally intermingling with the child’s other activities (Woodfall and Zezulkova Citation2016; Parry and Taylor Citation2018). ‘Volitional’ thus applies in our study to both reading and non-reading engagements and denotes an activity that is ‘self-directed, (involving) anticipation of the satisfaction gained through the experience and/or afterwards’ (Kucirkova and Cremin Citation2018, p. 573). Whether the relevant engagements were necessarily ‘self-initiated’ (Kucirkova and Cremin Citation2018, p. 573) or not, or whether school-based learning fell outside the focus or not, was left to each participant’s interpretation.

The main objective of this article is two-fold. First, we explain the cultural and theoretical background of the research. Against this background we present the research design, offering it also as a toolkit with prop descriptions and sample questions (Appendix A) for further adaptation in research or practice, similarly to our earlier toolkit on children’s embodied responses to fiction (Kuzmičová, Supa, Segi Lukavská, et al. Citation2022). Second, we offer two purposefully selected narrative case studies of children whose factual engagements emerged as equally experientially rich but vastly different in nature, representing a ‘learning’ and ‘wonder’ focus, respectively. These differences were mirrored in how the children approached the various reflective steps of the interview. The case studies thus succinctly show the interview toolkit’s flexibility while also offering qualitative depth in relatively accessible narrative form.

Children’s nonfiction: current developments, status, local context

The past two decades have seen an unprecedented global momentum in children’s nonfiction generally and nonfiction picturebooks especially (Grilli Citation2020a). Richly illustrated books on the most varied topics are replacing the text-heavy reference volumes of the pre-internet era, inviting new, interactive reading experiences (Moss Citation2001; Merveldt Citation2018). Having stayed in the margins of scholarly interest throughout the previous century, nonfiction has also begun to attract the attention of literacy researchers (Kesler Citation2012, Citation2017; Alexander and Jarman Citation2018) and children’s literature scholars (Grilli Citation2020b; Goga et al. Citation2021). However, general notions of meaningful volitional reading continue to be strongly linked with fiction (Larkin-Lieffers Citation2015; Mackey Citation2020). Nonfiction still tends to be seen as the lower-status, perfunctory reading choice of stereotypically male and stereotypically reluctant or geeky readers (Mackey Citation2020). In Repaskey et al.’s (Citation2017) book selection study in Canada (ages 6–7, 9–10; N = 84) boys indeed preferred nonfiction over fiction while girls’ choices were balanced across both genres; yet when asked about books suitable for their peers, participants indicated nonfiction as a male choice and fiction as a female choice. In Scholes’ (Citation2018) Australian survey study of children’s reading behaviours (ages 8–10, N = 297), children who distinctively preferred nonfiction reported that they avoided sharing their reads, sensing a lack of social acceptance.

In some countries such as England and the U.S., educational policy and classroom data suggest that nonfiction in various formats has gained in prominence in literacy instruction since the turn of the millennium (Lewis Citation2009; Conradi Smith and Hiebert Citation2022). The ongoing expansion and transformation of children’s nonfiction also concurs with the current STE(A)M initiative for integrating STEM subjects with the arts (University of Cambridge Citation2021) and promises further proliferation of nonfiction books in schools. However, educational uses of the burgeoning nonfiction picturebook trend have been little explored in the research literature (for exceptions see Kesler Citation2017; Swartz Citation2020). As an object of volitional reading, nonfiction seems mostly relegated to homes and other non-school (Alexander and Jarman Citation2018) and non-public (Larkin-Lieffers Citation2013) spaces.

In Czechia where the current study took place, nonfiction is only implicitly incorporated in the primary literacy curriculum and policy, insofar as children are expected to recognise differences between literary and informational text and master reading strategies adequate for both (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic Citation2023). Results of the most recent PIRLS study show no significant score difference across the two text types (Mullis et al. Citation2023), even though reading instruction in the country heavily relies on anthologies in which narrative fiction is either a strongly dominant or the only prose genre (Segi Lukavská and Kuzmičová Citation2022). Nonfiction is also excluded from the ‘reading workshop’ (Šlapal Citation2007), the most widely promoted choice-led reading pedagogy in the country. Meanwhile, in line with international developments, annual numbers of new children’s nonfiction titles on the Czech market quadrupled from 200 to 823 between 2001 and 2021 according to the National Bibliography Database (our own data harvests). Representative surveys of children’s reading preferences across the country steadily place ‘nonfiction/encyclopaedias’ among the top five (of 11) standardised book categories and ‘books about nature or animals’ (fiction/nonfiction) as the second most frequent category (Friedlaenderová et al. Citation2018, Citation2022).

Theoretical background: holistic perspectives and reader’s ‘stance’ in the context of facts

The research presented here is child-centred; it explores children’s own views on their lived experience (Montreuil et al. Citation2021). We adopt a whole-child perspective on this experience, on two levels. First, our research design aligns with work in which children are shown to engage with texts ‘holistically’ (Woodfall and Zezulkova Citation2016; Parry and Taylor Citation2018), that is, to move seamlessly across varied formats and activities which vastly exceed reading (e.g. artmaking, viewing, play). In this sense, a holistic perspective entails that reading should be studied within a larger complex of everyday activity if children’s authentic experiences are to be understood. Previous literacy research in this vein includes Parry and Taylor’s (Citation2018) respective multi-method studies of school-based reading and writing for pleasure, Cannon et al.’s (Citation2018) creative research into children’s play and textual improvisation in analogue and digital formats, or Pahl and Rowsell’s (Citation2020) participatory work in which blended everyday literacy is purposefully defined with active verbs that work across textual modalities: ‘seeing,’ ‘knowing,’ ‘hoping,’ ‘disrupting,’ ‘harnessing,’ ‘creating,’ and ‘making. Nonfiction is not categorically excluded from this body of research, but the significant attention paid to stories means that engagement with facts, and especially their non-storied expository forms, has not yet been systematically charted in its holistic nature.

Second, our holistic or whole-child position entails a strong focus on the affective qualities of children’s varied literacy practices as they unfold in time. Existing in-depth inquiries into child readers’ felt experiences relate overwhelmingly to fiction (Smith Citation1991; Sipe Citation2000; Wilhelm Citation2016; Kuzmičová, Supa, and Nekola Citation2022; Kuzmičová, Supa, Segi Lukavská, et al. Citation2022). Wilhelm (Citation2016) explored such experiences, conceptualised as distinct ‘pleasures,’ in a longitudinal design. Interviews were conducted over three years and the following experience categories emerged: ‘immersive play’ (total engagement); ‘intellectual’ (figuring things out); ‘social’ (conduit to others); ‘practical work’ (usefulness for other tasks); ‘inner work’ (actualising one’s potential). In Kuzmičová, Supa, and Nekola (Citation2022), we employed Q methodology to study children’s felt absorption in fiction, arriving at four perspectives: ‘confirmation’ vs. ‘growth’ (staying within vs. expanding personal boundaries); ‘attachment’ (to characters), and ‘mental shift’ (working towards mastery). While variations of several of these phenomena may apply to nonfiction, those related to notions of the self (e.g. inner work/growth as listed above) may be particularly relevant for a holistic outlook, considering that young people’s real-world subject interests also link to who they imagine they might become (Eccles Citation2009; Stahl et al. Citation2023). Richardson and Eccles (Citation2007) introduce the term ‘possible selves,’ rooted in social psychology, for such imaginings in a study of teenagers’ choices of fiction.

Albeit understudied empirically, children’s engagement with factual genres has a history of theorisation in Rosenblatt’s (Citation1978) concept of ‘stance.’ As proposed by Rosenblatt, at any given point, readers either adopt an ‘aesthetic’ stance (i.e. an orientation towards lived experience as it unfolds while reading, tapping into one’s past inner life), or an ‘efferent’ stance (under which one reads not for the lived experience, but for information or guidance to be taken away for later). Efferent stance was linked by Rosenblatt to information genres under which she also subsumed all science (Rosenblatt Citation1978, p. 32). The two stances were however conceptualised as two ends of a continuum along which one may shift to-and-fro, within or across reading sessions. Rosenblatt’s theory is revisited in recent work on children’s nonfiction. Kesler (Citation2012, Citation2017) uses Rosenblatt’s concepts to model how children may approach a corpus of poetic nonfiction (N = 51) categorised into six types between the aesthetic and efferent poles. Alexander and Jarman (Citation2018) invoke the conceptual pair when summarising children’s evaluations of a U.K.-based science reading challenge (ages 8–14, N = 309). Notably, affectivity is also attributed to instances of the efferent stance, e.g. when ‘gaining new knowledge, learning a fascinating fact, picking up a factoid to recount to a friend’ is mentioned to exemplify children’s ‘efferent pleasures’ (Alexander and Jarman Citation2018; p. 84, our italics). The research presented in this article explores children’s in-depth accounts of efferent/aesthetic/mixed ‘pleasures’ as afforded by nonfiction text but also, holistically, by factual content that is not mediated by reading specifically.

Current study

Materials and methods

An interview toolkit (Appendix A), i.e. an ordered set of verbal and material stimuli, was developed to facilitate children’s (ages 9–11) reflection on their affective engagements with the world of facts. It aimed at directly exploring children’s experiences in their own terms and from their own perspectives. For this purpose, it relied on bespoke creative props (e.g. picture cards, page layout cutouts, children’s nonfiction books) inviting children of varied capabilities and personal traits to communicate their experiences through a combination of verbal and nonverbal actions (Kortesluoma et al. Citation2003; Punch Citation2007). Although developed for individual interviews in home settings, the toolkit can be used in other contexts and adapted to, for example, focus group research or classroom or library interventions. In Appendix A we include selected questions from the interview script; these were used as initial prompts for further, more open-ended conversation.

The interview consisted of Parts I-III. Part I began with a quick icebreaking phase in which the world of fiction was brought up as an aid in defining the world of facts/real-world interests. Next, the child’s affective engagement with the latter was discussed in depth. This conversation revolved around the child’s individual interests, as selected from among a set of twenty-one miniature picture cards (e.g. animals, space, history, fashion; plus any number of personalised additions) and collaged by the child onto a paper circle labelled My real world. By establishing the child’s selection first, it was ensured that all following conversation primarily focused on engagements of genuine ‘subjective task value’ (Eccles Citation2009) for the child, as per the topics’ ‘intrinsic interest’ and significance to identity (Eccles Citation2009) and possible selves (Richardson and Eccles Citation2007). Then the child was presented with a set of cards verbally denoting different activities (e.g. viewing, reading, listening; plus any number of personalised additions). The child sorted these cards while discussing each activity’s relevance to their key interests and its overall place in their life, thus reflecting on their own factual engagements in a holistic and dialogic manner (Woodfall and Zezulkova Citation2016; Parry and Taylor Citation2018).

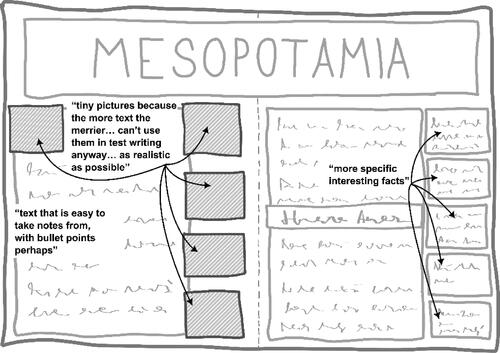

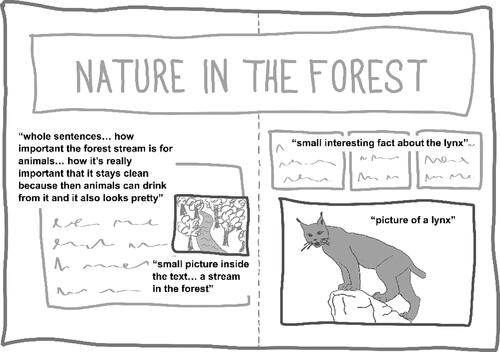

Part II was more structured and zoomed in on nonfiction books and reading. The child was invited to imagine having a bespoke nonfiction book made for them; they chose the topic of such a book and suggested a layout for it (see and ) using paper cutouts in various sizes labelled heading, picture, text. This was followed by a session of leafing through a set of diverse nonfiction books; the child was free to make ongoing comments or leaf in silence and then indicate what they liked or disliked about specific books; the child also selected which book most resembled their ideal. In the current study, all six sample books dealt with the human body – a topic that was considered likely to prompt some ‘remindings’ (Kuzmičová and Cremin Citation2022) or other personal connections (Kuzmičová, Supa, Segi Lukavská, et al. Citation2022) but at the same time relatively neutral in its interest status among 9- to 11-year-olds.

Having interacted with the sample books, the child finally reflected over a set of nonfiction building blocks (), i.e. picture cards with verbal labels denoting various formal and content features as also represented in the sample books (e.g. numbers, notable people, funny stuff, things I can do; plus any number of personalised additions); the child sorted the building blocks according to suitability for their imagined book. The building blocks were developed based on existing theoretical work (Moss Citation2001) and practitioner writing (Stewart Citation2018) on children’s nonfiction book design. This literature also informed the diversity criteria applied in selecting sample books. For each building block, a set of follow-up questions (not shown in Appendix A) was included in the interview script to be used as relevant.

In Part III, the participant was invited to show any artefacts related to their factual engagements as previously discussed, such as art/craft/toys related to a favourite animal, sports- or history-related collectibles, knowledge boardgames. Thus, focus returned at the end from the relative abstractions of the nonfiction building block activity to the child’s everyday experience, materialised in tangible objects. The researcher could suggest an artefact that had been explicitly mentioned but the child was free to choose what they wished to show, if anything at all.

Participants and procedures

The study took place in Czechia in spring 2023. Twenty children aged 9 to 11 years (10 girls and 10 boys balanced for age; mean age 10.2 years) took part in the study. At the age of nine, reading in a technical sense has typically been acquired by Czech L1 learners as Czech has a consistent orthography and is relatively easy to decode (Caravolas et al. Citation2013), and eleven is the age at which children complete the first stage of schooling. The children were diverse as to their socioeconomic background, living in two-parent/one-parent families of different income levels and in four cases (2 girls, 2 boys) in children’s homes, i.e. residential communities where children who cannot live with parents are looked after by staff on a shift basis. All children spoke Czech as the/a first language even though linguistic ability varied. Ethnic-linguistic identities were not actively inquired into as this might be seen as intrusive in the Czech sociocultural context; however, at least seven participants in some sense represented ethnic and/or linguistic minorities. This diversity cut across socioeconomic conditions and living arrangements. Among the noted additional first languages were Italian, Romani, and varieties of English.

The interviews lasted 1 h and 11 min on average and took place in participants’ bedrooms or other home spaces allowing the child to feel comfortable. The final choice of space was left to the participant and caregiver(s). At least one caregiver always remained available in a different part of the home and was free to check on the child at any point. The child was free to take a break and/or leave the room as they wished. Parts I-II were video- and audio-recorded. Photographs were taken in Part III and annotated with retrospective fieldnotes. Only one researcher was present at each interview; seventeen interviews (including the two case studies below) were conducted between the two authors of this article while the remaining three were conducted by two carefully trained mentee researchers. Narrative debriefs were logged and shared among the team immediately after each session. Children’s faces or larger sections of their private space were not captured as photographs and video recordings were mostly zoomed in on the child’s hands manipulating the research props. The data was safely stored and anonymised upon transcription. Two pilot interviews were conducted which resulted in adjustments in prop design (changed structure of interest area cards, activity cards, and sample books) and question and instruction wording.

Participants were recruited via teacher and recreational educator contacts initially, then via participating children’s families using the snowballing technique (Browne Citation2005), and additionally via children’s home managements. Age, gender, and socioeconomic variation (as detailed above) were the basic sampling criteria. An additional sampling objective was to balance children who, according to their caregivers, were strongly invested in a specific topic vs. children of more miscellaneous interests. Further thematic variation was sought among the specific topic children or ‘geeks’ as indicated by caregivers, e.g. some of these children were presented as passionate about a particular sport, others about history, animals, and so forth. However, all children living with parents had at least one parent who held a post-secondary degree, and all children’s homes had staff with such degrees, suggesting that information conveyed via written word may have been similarly (and relatively highly) valued by all caregivers; we were unable to overcome this limitation to diversity.

Written informed consent was obtained from parents/children’s home staff and oral consent was obtained from participants, in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation of the European Union. Ethical and legal standards of research with vulnerable groups and children were strictly followed. Additional steps to prevent harm were taken for participants in children’s homes, where staff was asked beforehand about any triggers linked to the child’s personal history (e.g. family-related discourse). Participants were approached as competent social actors who have a right to express their thoughts, feelings and views and to partake in the construction of their lives and the decision-making that affects them (Harcourt and Sargeant Citation2012; Tisdall Citation2015). One participant decided to terminate the interview session upon completing Part I. Others expressly described the research experience as enjoyable and at points valuable for their self-understanding, as also manifested by one of the case children who asked to photograph his outputs to be able to look at them later. The research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Arts, Charles University, decision number UKFF/46906/2023. No additional ethical or legal clearance is officially required in Czechia. After data collection was completed, each participant was gifted a book handpicked for them based on their preferences as expressed in the interview.

The two cases were selected for the relative qualitative depth of the children’s individual accounts as per both authors’ review of all post-interview debriefs. An additional selection criterion was that both case children’s chosen interest areas, book layout features, sample book preferences, and so forth, would overlap with any notable trends across participants, thus ensuring representativeness vis-à-vis the overall sample. All twenty participants’ quantifiable prop choices in Parts I-II of the interview were therefore converted into numeric tables and subjected to descriptive statistical analyses by the first author (relevant outcomes below). For qualitative richness and contrast, we purposefully selected one child who was strongly invested in specific topics vs. one child of more miscellaneous interests. The two case children further strongly diverged in how they engaged with facts via volitional reading and otherwise. This was also reflected in how they differently approached the various steps and props of the interview (e.g. spending different amounts of time, choosing different prop quantities), their dissimilarities thus exposing the toolkit’s scope and flexibility in a nuanced way. Finally, we purposefully selected participants of comparable socioeconomic backgrounds, wishing to avoid comparisons across socioeconomic conditions; the latter will be the subject of future work.

Both case interview transcripts were repeatedly read by each author and subjected to open inductive coding. Next, the codes were merged and reduced in iterative joint discussion, then relevant findings were organised into unified three-themed narratives by the first author with the second author’s assistance. The three themes structuring both narratives are ‘the self,’ ‘the aesthetic/efferent,’ and ‘word/image’ relationships as also linked to the main subjective import of nonfiction reading. On a general level, these themes inhered in the research design, together with several others. For example, links between factual topics of interest and the child’s present and possible selves were expressly addressed in several questions, while choosing between words and images was central in the book-related steps (see Appendix A, sections 2-3 and 5-6). However, the scope and complexity of these themes, as they emerged through the whole interviews, exceeded our initial conceptualisations. Their qualitatively distinct instantiations between the two case children, in turn, were extracted on a strictly data-driven, inductive basis. The individual case narratives reflect the structure of the interviews insofar as key findings from the two conversational Parts I-II are presented mostly in that order. The course of Part III was not analysed independently, but several of the artefacts shown are expressly mentioned as they helped us discern the children’s priorities and offered a material context for the practices discussed.

The case studies

Introduction to the case studies

Our two case studies are Emy, an 11-year-old girl, and Jan, a 10-year-old boy (pseudonyms). Their socioeconomic backgrounds and living arrangements converge insofar as they both live with both of their parents, in a middle-income household, and have siblings close to their age. Emy and Jan’s quantifiable prop choices are representative of the remaining sample insofar as both chose animals as one of their interests and discussed them at length; animals were the most frequent interest area overall, chosen by sixteen participants and indicated as a top area by ten, including Jan. Jan also included animals as a key topic in his imaginary book, together with the largest cohort of nine peers. Like most others, both Emy and Jan laid out a relatively broken-up double page for their imaginary book, combining text/picture features of varied sizes while avoiding large picture (the least frequent feature overall, used only by six participants), and spontaneously highlighted that ‘interesting facts’ (factoids) should be included. Finally, both belong in the majority of fourteen children whose choice of sample book included at least one book in picturebook format.

More idiosyncratically, Emy and Jan share a strong passion for woodlands and nature overall, despite living in vastly different locales (details below). They even phrase their feelings of connectedness and responsibility within the natural world in similar terms, e.g. ‘nature is incredibly important, because we wouldn’t be here without it’ (Jan, about the nature topic); ‘in my view plants are the most important thing on the planet, because without them there would be no life’ (Emy, about the gardening topic). Since many years, both entertain an empathic fascination with a woodland carnivore: Emy loves foxes (‘they’re misunderstood’), Jan loves lynxes (‘they’re shy and quiet and alert’). Both children own toys, clothes and other artefacts representing their favourite creature and they frequently engage in thoughts, artmaking, and other activities related to it, yet their mutual similarities do not go further beyond this specific practice.

Emy

Topic-driven self

Emy lives in a remote village of twenty inhabitants with her parents and two younger siblings. Her parents work in the district’s local administration in positions that also reflect their educational backgrounds in forestry (father), fishery (mother) and water resource management (both parents). Upon recruitment, Emy was described by her parents as a child who is strongly invested in specific topics, especially history. She commutes to a publicly funded school in the nearest town and spends much of her time out of doors playing and tending to plants, but also fishing or gamekeeping with her family. She also goes to climbing practice and a hunting and gamekeeping club. Emy selects fifteen interest areas, thirteen from the original set and two personalised additions (fishing; hunting/gamekeeping). Her selection is among the largest in the study overall (range 6–17, mean 11). School is a key emergent theme in Emy’s narrative; she is fond of her teachers and prides herself in performing well in many subjects, but also identifies those which bore her and in which she lacks ambition (physics, ICT).

Emy expects from the outset that her full range of interests may not be captured within the original set. This is typical of Emy’s participation: she knows well what she is deeply curious about vs. not, sees her manifold interests as one with her self-concept, and ventures into what her learning within these areas means for her possible future selves, as either gamekeeper or archaeologist. About these two competing dream professions, she says, ‘I’ll just finish middle school and get cracking.’ Such me-centred, agentic statements are frequent throughout Emy’s interview; accordingly, she dwells on the different props and questions only so long as they make sense to her (‘making sense’ being one of Emy’s recurring expressions), given her preexisting interests.

Efferent to aesthetic engagement

Emy singles out four top interests: history; nature; fishing; hunting/gamekeeping. In her case, history provides most consistent ground for discussing engagement through other than purely practical activities. Emy’s interest in history began several years back when she was gifted a book from a popular history crime fiction series. This was also when she started more regularly reading books – the ever-growing series specifically (shown to researcher) – in her spare time. Since then, history (‘the whole world simply, different periods’), is an area within which she is systematically building up expertise. She does so through reading historical fiction, fact-checking and searching online, crafting, watching documentaries or period films (preferring the former), collecting history-themed souvenirs such as royal family tree posters (shown to researcher), and more.

Although she generally enjoys looking up facts and browsing through pictures in print nonfiction (nature encyclopaedias), Emy does not own or read nonfiction books on history specifically. What she likes in relation to history is being formally tested on her knowledge in writing. She then adorns her school tests with fun facts that she has picked up outside school, e.g. on a trip to a historical site: ‘so this test was on Archduke Franz Ferdinand (…) and I even wrote down for the teacher how old he was when he shot his first boar.’ Emy’s focus on self-improvement through learning means that her engagement with facts often tends towards the efferent. As she says, the historical fiction ‘teaches’ her about history, and ‘when things stop making sense (…) and I don’t get to know it from the teacher, or my parents, then I just go and search.’ As a next step, however, she puts factual input to aesthetic, more freely imaginative uses in moments of private pretend play; she goes outside then and talks to herself in a ‘crazy hodgepodge’ of historical narratives and fictional imaginings. She taps back into her memories of these experiences during history classes. When asked about the activity that best helps her immerse in her topic, Emy provides two: playing (in the above sense) and reading.

Word over image and reading for learning

Emy strongly values words over images. The layout () of her double page, in an imaginary volume on world history which should contain ‘as much information as possible,’ resembles a traditional textbook.

Emy does not suggest specific content for the form she lays out. We get to know that the double page, which might be titled ‘Egypt or Mesopotamia or Mesopotamian culture,’ is packed with text that should be ‘easy to take notes from, with bullet points perhaps,’ accompanied by only very small realistic images in the margins of the left page and entirely imageless on the right. Emy feels that ‘the more text the merrier’ and says, ‘I do take a peek but then I can’t use (the images) in test writing anyway (…) because I don’t know how to recreate them as it were.’ Nonfiction building blocks are likewise assessed by Emy in terms of their learning value, for class and beyond: New words are important for writing, questions for me are good test practice, and funny stuff ‘makes learning easier.’ The only two items that Emy expressly rejects are the visual comics and inside of things.

When leafing through the various sample books, Emy becomes puzzled by The Hand (Garguláková and Mecner Citation2021), a highly stylised picturebook on the role of hands in human life and culture. Later Emy explains why she chose to read its back cover information: ‘I couldn’t figure out, because there were mostly pictures, I didn’t get what it was about exactly.’ It does not occur to Emy that she may wish to glean meaning from images alone, perhaps while cursorily dipping in the verbal component, rather than from sustained perusal. Immediate visual appeal and fragmentary perspectives do not agree with her orientation; this also makes for a relatively short leafing session (7.5 min; overall range 4–22 min, mean 11 min) during which she offers almost no comments. The picturebook she quickly settles on as her preferred choice (alongside a DIY book of experiments simulating bodily processes) charts the different systems of the body. She appreciates that there is a character who acts as a guide, similarly to her favourite historical fiction series, and that the information is ‘clearly explained;’ thus the book would best support the learning that is her primary concern in relation to nonfiction and reading and life more generally.

Jan

Open self

Jan lives in a city of 1.5 million with his parents and older brother. His parents hold degrees in social science and work as civil servant and NGO worker, respectively. Upon recruitment, Jan was described by his parents as shifting rather than stable in his real-world interests. He goes to a publicly funded school near his home and among his main pastimes are scouting, running, and the violin. For Jan, determining key interests is not a matter of simply communicating what he already knows about himself. It becomes an ad hoc process of figuring out, during which Jan’s reflections aim at what most frequently brings him pleasure in life (‘to like,’ ‘pretty,’ ‘pleasant,’ ‘nice’ etc. being his common expressions). He manifests a relatively open sense of self and keeps spontaneously bringing up connections with other beings, e.g. friends’ interests, or knowledge boardgames (shown to researcher) frequently played with his brother. His musings over facts are, accordingly, often formulated using first person plural (‘it can be hard for us to understand how pianists can play so fast’) or second person singular (‘it’s a nice feeling to be playing together, then you’re not alone on the stage’).

Jan selects seven interest areas, six original ones and one personalised addition (pop songs). His selection is thus among the smallest overall (range 6–17, mean 11). The original areas are evenly divided between the natural and human, animals and music being Jan’s top areas. Given his violin play, music emerges as less a domain of facts than of practical activity. It is also the one area wherein he spontaneously offers but a shy and tentative imagining of his possible adult self, as a professional violinist. Jan assumes a highly participatory role in the research: he adds personalised illustrated props whenever he can, reflects on the most logical ways of organising them in space, and photographs his outputs as a keepsake of the interview.

Aesthetic to efferent engagement

Jan’s stance towards the world of facts is aesthetic and broadly curious rather than topic-driven. Any ‘interesting fact’ (an expression that he uses especially often) in any area can potentially make him stop and wonder. Among animals, this regards especially the lynx, which is his favourite since many years and which he often looks up online. However, the primary goal of these searches is to ‘sit and sort of observe’ the object of his curiosity, ‘mainly in pictures,’ rather than take in written information (or video). Even more rewarding for him are live observations of animals (at home, the zoo) and Jan imagines that he may meet a lynx in the wild one day: ‘recently I went cross-country skiing and I was wishing so hard I’d meet one, it was so quiet there (…) and there was this open plane so I would be able to see it.’ Jan mentions print nonfiction (encyclopaedias), having a few such books in his home; but for him reading as activity relates to his interest in animals or other factual contents ‘only a little bit,’ being instead closely associated with fiction, which he recently began reading more regularly (Harry Potter). Writing about animals does not appeal to him as he finds written composition difficult, but he likes drawing them (art shown to researcher).

Jan speaks about different animals as each ‘having’ their own ‘interesting fact that we don’t expect.’ Whenever he encounters such a fact in whatever modality (e.g. at a lecture in a marine life centre attended with class), he consciously works to store it away so that he can tell others. This is also his vision for his imaginary nonfiction book: ‘I would read it to myself and then tell others about those interesting facts that I liked.’ Talking is the activity that Jan singles out as most immersive relative to animals, even though viewing is his favourite activity overall. This additional focus on sharing constitutes the efferent, purposeful dimension in his factual engagement. What matters most in its pursuit, however, are not the specific facts as such (‘how long something is’ – ‘so you can imagine what it looks like’) but the joy that they have given him and that he wishes to pass on: ‘when I go tell mum, it’s more often the funny stuff’; ‘or how cute (polar bears) are.’

Image over word and reading for wonder

The imaginary double page that Jan lays out () is relatively minimalistic, as to the number of cutouts used and page area covered. At the same time, Jan is generous with ideas for the specific contents that his double page should convey.

The topic of Jan’s book is the forest and its animals. His double page is titled ‘Nature in the forest.’ On the left is a small picture of a forest stream with a short paragraph explaining in ‘whole sentences (…) how important the forest stream is for animals (…), how it’s really important that it stays clean because then animals can drink from it and it also looks pretty when it is clean and not polluted.’ On the right is a half-page picture of a lynx and a few lines of text containing some ‘small interesting fact’ about the lynx. Jan’s layout has only a small quantity of text; later he says that he does not like when there is a lot of text in a page or excessive detail provided on a topic, something he considers more suitable for older readers. When sorting the nonfiction building blocks, Jan also chooses to contribute a personalised item, things in detail, which he then places in the negative category.

Jan giggles frequently over the sample books, wondering at their multimodal makeup. He makes predictions as to a book’s message based on pictorial detail, comments on illustration style, and reads diagonally across captions and pages. His leafing session is the longest recorded (22 min; overall range 4–22 min, mean 11 min); yet he is still reluctant to put the books away. As his favourites he selects The Hand (Garguláková and Mecner Citation2021) and a picturebook that he notes is distinctly narrative in structure. Despite saying that the human body is not a topic he would normally choose, his ongoing commentary testifies to many complex affective processes triggered by the books – remindings of facts known from elsewhere (‘I’ve learned somewhere that your small intestine is five times the length of your body’) and of his own embodied experiences (‘I don’t like this, being itchy, but nowadays I try to wait it out’); defamiliarisation and wonder at the body’s ability, as shared with other humans (‘you don’t even have to think and each of your hands will do its part and together they will do it perfectly’); acknowledgment of the book authors’ insight into his experience (‘they know precisely what happens to you’) and, finally, the realisation that knowledge in nonfiction books, too, is shared with others (‘it makes me happy that other people will know it’).

Discussion and conclusion

One of two main objectives of this article was to provide impetus to studying children’s lived experiences of nonfiction and doing so holistically, within the context of other volitional factual engagements beyond books and reading. A child-centred interview toolkit, so far used with twenty participants aged 9 to 11 years, was put forward to that end. The toolkit utilises creative props and opens with an inquiry into the participant’s preexisting interests and various related activities, before reading and books come into more explicit focus. This makes it possible for the toolkit to accommodate children of diverse capabilities and reading backgrounds. Our second objective was to show, through two case studies, the breadth and nuance of experience that can be harnessed using the toolkit. The two case children’s orientations towards nonfiction differ widely. Emy’s main concern is purposeful learning, i.e. consolidating information around pre-determined topics. Within Rosenblatt’s (Citation1978) efferent – aesthetic continuum, her declared stance is efferent. Jan in turn pursues moments of wonder, musing over the world’s sensory qualities as per Rosenblatt’s aesthetic stance; any random fact can thus momentarily ignite his interest in a topic.

The toolkit’s holistic makeup brings to light experience dimensions that might go unnoticed in interviews narrowly focused on books and reading. For example, Emy’s remarks on her imaginary book’s usefulness for test purposes, or her handling of the sample books, would easily create an impression of utilitarianism, if separated from initial conversations revealing her deep curiosity about the world and imagined possible selves within it. The imaginative play through which Emy puts factual contents to aesthetic use, contradicting stereotypical binaries (Moss Citation1999) between facts and imagination, would also be missed in a more reading-centred research design. In Jan’s case, pervasive mentions of other people in the opening phases of the interview enabled us to see how aesthetic wonder at the natural world can concur with an efferent focus on storing information to pass onto others. Jan’s interview differed from Emy’s not just in the content of the answers provided but also in their form. For example, while Emy comments on her double page purely in terms of formatting, Jan provides the very words to be inserted in his chosen layout. His proposed text is akin to contemporary nonfiction in which facts ever more creatively blend with emotion, questions of beauty, and social appeal (Merveldt Citation2018; Grilli Citation2020b).

The main limitation of our research, apart from ad hoc diversity issues regarding caregivers’ education levels (details above), is the private and time-intensive nature of the research design which yields rich data but raises issues regarding participants’ feelings of comfort and safety; this is alleviated by the creative props and participatory features, and by the highest standards of respect shown to participants throughout. All participants bar one who chose to quit mid-session evaluated the research as enjoyable and not too tiring, but again, the toolkit alone cannot guarantee this. Researchers in diverse fields beyond literacy, but also teachers or librarians, may benefit from our toolkit or its modified versions. For teachers, group adaptations of the opening steps could serve student-led reflection on preferred topics within content subjects (e.g. science, history), for example when revisiting a year’s work. Our book-related props, especially the layout and building blocks, could then be used to help students in creatively designing more full-fledged double pages (see also Kesler Citation2017). Students would then take home a physical token of their past learning but also increased awareness of what sort of volitional nonfiction reading interests them and why. In children’s libraries, props from the first and last steps of the toolkit (topic selection, building blocks) could be combined in designing efficient nonfiction recommendation procedures.

Summing up, the current research provided systematic insight into the varied areas of volitional reading and everyday experience that are missed when factual engagements remain conventionally separated from affect and when reading is studied in isolation from other activities. Contrary to these conventions, our interview toolkit garners children’s own views of their interests and experiences, in a holistic manner. It also reverses traditional research approaches insofar as nonfiction reading is not primarily conceptualised as an alternative (mostly marginalised; Larkin-Lieffers Citation2015; Mackey Citation2020) to the volitional reading of fiction or formal learning materials. Advocating child-centred research and practice, we rather position nonfiction reading within the fuller landscape of real-world interest development and explore children’s own motivations for including it, or not, in this landscape.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Filip Novák for creating the drawings used in the research and this article, Victoria Nainová and Karolína Šimková for their assistance in recruiting participants and collecting and processing data, and Klára Matiasovitsová for coordinating data transcription.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alexander J, Jarman R. 2018. The pleasures of reading non‐fiction. Literacy. 52(2):78–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12152

- Browne K. 2005. Snowball sampling: using social networks to research non‐heterosexual women. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 8(1):47–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000081663

- Cannon M, Potter J, Burn A. 2018. Dynamic, playful and productive literacies. Chang Engl. 25(2):180–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/1358684X.2018.1452146

- Caravolas M, Lervåg A, Defior S, Seidlová Málková G, Hulme C. 2013. Different patterns, but equivalent predictors, of growth in reading in consistent and inconsistent orthographies. Psychol Sci. 24(8):1398–1407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612473122

- Conradi Smith K, Hiebert EH. 2022. What does research say about the texts we use in elementary school? Phi Delta Kappan. 103(8):8–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/00317217221100001

- Eccles J. 2009. Who am I and what am I going to do with my life? Personal and collective identities as motivators of action. Educ Psychol. 44(2):78–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520902832368

- Friedlaenderová H, Landová H, Mazáčová P, Prázová I, Richter V. 2022. České děti a mládež jako čtenáři v době pandemie 2021 [How Czech Children and Youth Read in the Pandemic, 2021]. Brno: Host.

- Friedlaenderová H, Landová H, Prázová I, Richter V. 2018. České děti a mládež jako čtenáři 2017 [How Czech Children and Youth Read, 2017]. Brno: Host.

- Garguláková M, Mecner V. 2021. Ruka: kompletní průvodce [The hand: a complete guide]. Prague: Albatros.

- Goga N, Hoem Iversen S, Teigland A-S, editors. 2021. Verbal and visual strategies in nonfiction picturebooks. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Grilli G. 2020a. Introduction. In: Grilli G, editor. Non-fiction picturebooks: sharing knowledge as an aesthetic experience. Pisa: Edizioni ETS; p. 11–14.

- Grilli G, editors. 2020b. Non-fiction picturebooks: sharing knowledge as an aesthetic experience. Pisa: Edizioni ETS.

- Harcourt D, Sargeant J. 2012. Doing ethical research with children. Buckingham: Open University Press/McGraw-Hill.

- [IEA] International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement. 2020. Progress in international reading literacy study student questionnaire. [accessed 2023 Aug 20]. https://pirls2021.org/questionnaires/.

- Kesler T. 2012. Evoking the world of poetic nonfiction picture books. Child Lit Educ. 43(4):338–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-012-9173-4

- Kesler T. 2017. Celebrating poetic nonfiction picture books in classrooms. Read Teach. 70(5):619–628. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1553

- Kortesluoma RL, Hentinen M, Nikkonen M. 2003. Conducting a qualitative child interview: methodological considerations. J Adv Nurs. 42(5):434–441. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02643.x

- Kucirkova N, Cremin T. 2018. Personalised reading for pleasure with digital libraries: towards a pedagogy of practice and design. Cambridge J Educ. 48(5):571–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2017.1375458

- Kuzmičová A, Cremin T. 2022. Different fiction genres take children’s memories to different places. Cambridge J Educ. 52(1):37–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2021.1937523

- Kuzmičová A, Supa M, Nekola M. 2022. Children’s perspectives on being absorbed when reading fiction: a Q methodology study. Front Psychol. 13:966820. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.966820

- Kuzmičová A, Supa M, Segi Lukavská J, Novák F. 2022. Exploring children’s embodied story experiences: a toolkit for research and practice. Literacy. 56(4):288–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12284

- Larkin-Lieffers PA. 2013. Informational books, beginning readers, and the importance of display: the role of the public library. Can J Inf Libr Sci. 37(1):24–39. https://doi.org/10.1353/ils.2013.0004

- Larkin-Lieffers PA. 2015. Finding informational books for beginning readers: an ecological study of a median-household-income neighbourhood. Can J Inf Libr Sci. 39(1):1–35. https://doi.org/10.1353/ils.2015.0007

- Lewis M. 2009. Exploring non-fiction texts creatively. In: Cremin T, editor. Teaching English creatively. Abingdon: Routledge; p. 138–151.

- Mackey M. 2020. Who reads what, in which formats, and why?. In Birr Moje E, Afflerbach, PP, Enciso, P, Lesaux, NK, editors. Handbook of reading research. Vol. V. New York/London: Routledge; p. 99–115.

- McGeown S, Bonsall J, Andries V, Howarth D, Wilkinson K, Sabeti S. 2020. Growing up a reader: exploring children’s and adolescents’ perceptions of ‘a reader’. Educ Res. 62(2):216–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2020.1747361

- Merveldt N. v. 2018. Informational picturebooks. In: Kümmerling-Meibauer B, editor. The Routledge companion to picturebooks. New York/London: Routledge; p. 231–245.

- Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic. 2023. Rámcový vzdělávací program pro základní vzdělávání [The primary curriculum framework]. [accessed 2023 Aug 20]. https://www.edu.cz/rvp-ramcove-vzdelavaci-programy/ramcovy-vzdelavacici-program-pro-zakladni-vzdelavani-rvp-zv/.

- Montreuil M, Bogossian A, Laberge-Perrault E, Racine EA. 2021. Review of approaches, strategies and ethical considerations in participatory research with children. Int J Qual Methods. 20:160940692098796. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920987962

- Moss G. 1999. Texts in context: mapping out the gender differentiation of the reading curriculum. Pedagogy Cult Soc. 7(3):507–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681369900200070

- Moss G. 2001. To work or play? Junior age non‐fiction as objects of design. Reading. 35(3):106–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9345.00171

- Mullis IVS, von Davier M, Foy P, Fishbein B, Reynolds KA, Wry E. 2023. PIRLS 2021 international results in reading. Boston: Boston College, TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center. https://doi.org/10.6017/lse.tpisc.tr2103.kb5342

- Pahl K, Rowsell J. 2020. Living literacies: literacy for social change. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Parry B, Taylor L. 2018. Readers in the round: children’s holistic engagements with texts. Literacy. 52(2):103–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12143

- Punch S. 2007. ‘I felt they were ganging up on me’: interviewing siblings at home. Child Geogr. 5(3):219–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733280701445770

- Repaskey LL, Schumm J, Johnson J. 2017. First and fourth grade boys’ and girls’ preferences for and perceptions about narrative and expository text. Reading Psychology. 38(8):808–847. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2017.1344165

- Richardson PW, Eccles JS. 2007. Rewards of reading: toward the development of possible selves and identities. Int J Educ Res. 46(6):341–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2007.06.002

- Rosenblatt LM. 1978. The reader, the text, the poem: the transactional theory of the literary work. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Scholes L. 2018. Boys, masculinities and reading: gender identity and literacy as social practice. New York/London: Routledge.

- Segi Lukavská J, Kuzmičová A. 2022. Complex characters of many kinds? Gendered representation of inner states in reading anthologies for Czech primary schools. L1-ESLL. 22:1–24. https://doi.org/10.21248/l1esll.2022.22.1.406

- Sipe LR. 2000. The construction of literary understanding by first and second graders in oral response to picture storybook read-alouds. Read Res Q. 35(2):252–275. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.35.2.4

- Šlapal M. 2007. Dílna čtení v praxi [The reading workshop in practice]. Kritické Listy. Čtvrtletník Pro Kritické Myšlení ve Školách. 27:13–20.

- Smith MW. 1991. Constructing meaning from text: an analysis of ninth-grade reader responses. J Educ Res. 84(5):263–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1991.10886026

- Stahl G, Scholes L, McDonald S, Mills R, Comber B. 2023. Boys, science and literacy: place-based masculinities, reading practices and the ‘science literate boy’. Res Pap Educ. 38(3):328–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2021.1964097

- Stewart M. 2018. The five kinds of nonfiction: a look at the distinctions in informational books, with recommended titles. Sch Libr J. 64(5):12–13.

- Swartz L. 2020. Choosing and using non-fiction picturebooks in the classroom. In: Grilli G, editor. Non-fiction picturebooks: sharing knowledge as an aesthetic experience. Pisa: Edizioni ETS; p. 231–245.

- Tisdall K. 2015. Children and young people’s participation. In: Vandenhole W, Desmet E, Reynaert D, Lembrechts S, editors. Routledge international handbook of children’s rights studies. New York/London: Routledge; p. 185–200.

- University of Cambridge. 2021. Teaching pupils to ‘think like Da Vinci’ will help them to take on climate change. [accessed 2023 Aug 20]. https://tinyurl.com/2mb295p2.

- Wilhelm JD. 2016. Recognising the power of pleasure: what engaged adolescent readers get from their free-choice reading, and how teachers can leverage this for all. AJLL. 39(1):30–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03651904

- Woodfall A, Zezulkova M. 2016. What ‘children’ experience and ‘adults’ may overlook: Phenomenological approaches to media practice, education and research. J Child Media. 10(1):98–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2015.1121889